1. Introduction

In Brazilian vegetable production, there is a growing demand for pesticide application to control pests, diseases, and weeds. Compared to other agricultural segments, the sector of pesticide application technology is limited in terms of equipment and technical information [

1].

In vegetable crops grown in protected environments, such as Sweet Pepper (

Capsicum annuum), the difficulties are even more significant due to the greenhouse structures that impede the displacement and movement of mechanized sprayer systems [

2,

3,

4]. Thus, pesticide spray applications using backpacks and semi-stationary sprayers are widespread [

5,

6]. Studies conducted in several countries have shown that application equipment based on vertical boom movement and a lower spray rate result in a low level of deposition on the target and minimal application losses [

6,

7,

8].

The Irregular distribution of the pesticide on the target is also frequent, with the abaxial leaf surface and internal parts of the canopy being the plant structures that are more difficult to reach with spray droplets [

1,

9]. Another question is the establishment of the spray rate (volume of spray solution applied per area) without consideration of crop canopy characteristics at the time of spraying [

7]. Without this adjustment, the spray rate applied may exceed what is necessary to ensure the quality of the application, wasting resources and/or contaminating the environment [

10,

11].

Given these challenges, alternative pesticide application techniques need to be explored for sustainable protected cultivation. The inclusion of air assistance in application equipment increases the penetration of spray droplets into the crop canopy [

12], especially in crops with high leaf density [

1]. Benalia et al. [

13] compared an automated fixed system, designed specifically for pesticide applications in protected crops positioned at the top inside the greenhouse, with a conventional sprayer equipped with air assistance (model Special Serre 2000) positioned outside the greenhouse. The authors reported variations in the sprayed environment both in the vertical plane (using an automated fixed system) and in the horizontal plane (conventional sprayer with air assistance) over the deposit and spray coverage on the pepper leaves. These findings suggest that, depending on the application technique, air assistance can enhance spray penetration into the crop canopy; however, it may also increase spray deposition variability.

Electrostatic spraying transfers electrical charge to the spray droplets, resulting in the droplets being attracted to the target, which can increase deposition, especially in hard-to-reach targets, such as the abaxial leaf surface [

14,

15]. Advances in spraying systems with reduced spray rate and sensors, such as robot-spray systems, have been developed for crops in protected environments. However, many challenges must be overcome [

8].

Considering the issues mentioned above, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of reducing the spray rate and using pneumatic spraying with and without electrostatic charges on deposition levels, spray coverage, and pesticide losses to the soil in sweet pepper cultivation grown in a greenhouse.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of the Experimental Area

Two experiments were conducted during the 2019 and 2020 crop seasons in an area of commercial sweet pepper cultivation (22°47'03” S, 49°30'14” W) in the municipality of Santa Cruz do Rio Pardo - SP, Brazil. The crops were cultivated in a Londrina model greenhouse, measuring 600 m² (30 × 20 m), with ceiling heights of 3.8 m (on the higher side) and 3.0 m (on the lower side), covered with a 100 µm polyethylene film.

The cultivated sweet pepper hybrid was Pampa®/HM Clause. The seedlings were transplanted with a spacing of 0.35 m between plants and 1.52 m between rows. The sweet pepper plants were vertically staked and supported by horizontal polyethylene threads, which were fixed to the bamboo stalks.

2.2. Experimental Design and Treatments

The experiment was a completely randomized design with four treatments and five repetitions. An 8 m crop row represented each experimental unit, and only the central 6 m were considered a useful plot. The experimental units were distributed alternately in the greenhouse, leaving a plant line on both sides as a border.

The treatments used in the trial consisted of the follow spray techniques: Standard Farmer Hydraulics Sprayer (SFH) - a hand spray lance containing two empty conic jet hydraulic spray nozzles (JA-2 at 700 kPa), producing fine droplets and a variable spray rate according to the crop height (

Figure 1a); Reduced Volume Hydraulics (RVH) - a hand spray lance containing two empty conic jet hydraulic spray nozzles (JA-2 at 700 kPa), producing fine droplets and spraying 50% of the SFH spray rate; Pneumatic with Air and Electrostatic Assistance (PAEA) - a pneumatic sprayer with a hand held spray gun containing a nozzle with air assistance plus an electrostatic charge, producing extremely fine droplets (

Figure 1b) and spraying 25% of the SFH spray rate; and Pneumatic with Air Assistance (PAA) - a pneumatic sprayer with a hand held spray gun containing nozzle with air assistance, no electrostatic charge, producing extremely fine droplets andspraying 25% of the SFH spray rate.

The SFH treatment utilized the spray rate employed by the farmer at the time of the three plant heights during which the experiments were performed (

Table 1). Thus, the SFH treatment applied the standard spray rate used by farmers in the commercial area. In contrast, the RVH, PAEA, and PAA treatments evaluated the effect of using lower spray rates compared to SFH.

As manual application makes it difficult to obtain a precise displacement speed, the application speed of each treatment was measured individually to determine the actual spray rate (

Table 1), considering the operating conditions. For the application of the SFH and RVH treatments, a semi-stationary Yamaho

© sprayer equipped with a manual lance with two hydraulic spray nozzles was used. The boom was connected to a three-piston pump with a maximum flow of 18 L min

-1, driven by a 3-stroke, 4-stroke Otto cycle engine, via a 40 m hose producing 73 kW of power. The system featured a pressure controller with a manometer at the outlet of the spraying pump, and the solution was returned to a 50 L reservoir

. To monitor the working pressure with greater precision, a pressure gauge was installed next to the spray lance.

In the applications of the PAEA and PAA treatments, an electrostatic sprayer (MBP 4.0 model, Electrostatic Spraying Systems, Watkinsville, GA, USA) equipped with air assistance and an electrostatic induction system was used. The transfer of an electric charge to the drops was conducted by indirect induction. The system voltage was 1 kV, and the rechargeable battery contained in the spray lance was 9 V. The formation and fractionation of the droplets were determined by the pneumatic principle, utilizing air generated by a compressor driven by a four-stroke Otto cycle engine, which produced 4.85 kW of power. The air generated by the compressor was conducted to the handheld spray gun via a 30 m-long hose with a ½ in internal diameter. The volumetric median diameter (VMD) of the droplet spectrum generated was 40 µm, according to the manufacturer, resulting in a charge/mass ratio of 5.3 µC/g. The equipment featured a 15 L spray tank and adjustable shoulder straps for a personalized fit.

2.3. Evaluation of the Leaf Area Index (LAI)

The leaf area index (LAI) was quantified on the eve of each application to evaluate the deposit and soil losses (

Table 1). Six plants were randomly selected, and all their leaves were removed. The leaf area was measured with an LI-3100C area meter. Subsequently, the LAI was calculated using Equation 1.

where

is the leaf area index

is the sum of the leaf area of the sampled plants (m

2),

is the spacing between plants (m),

is the plant line spacing (m), and

is the number of plants sampled.

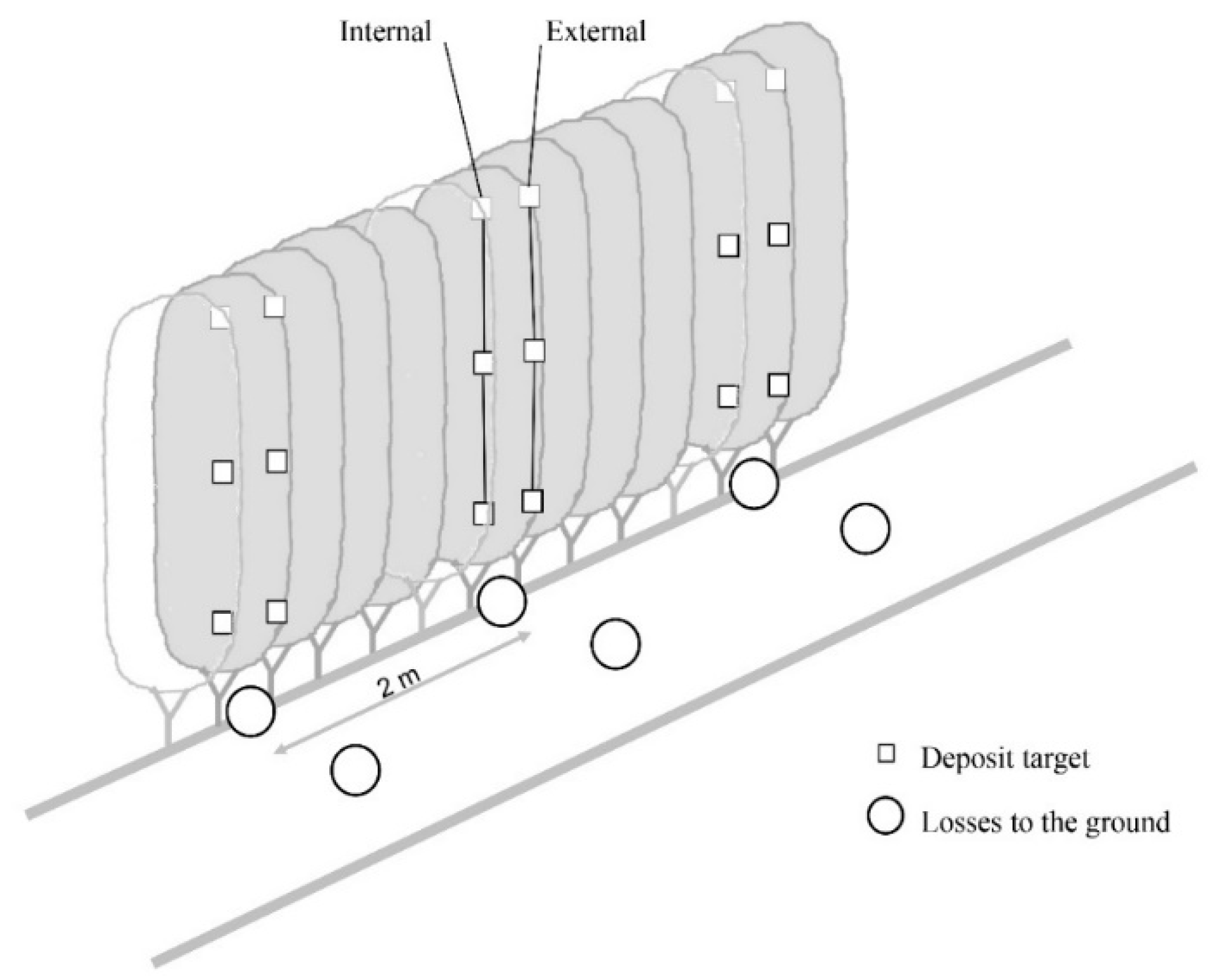

2.4. Evaluation of the Deposition and Losses to the Ground

The evaluations of spraying deposition and ground losses were performed in three stages of plant growth, corresponding to heights of 0.7, 1.4, and 2.1 m. The spray deposition was measured at two depths in the canopy in the vertical direction (inside and outside the plants) and on both leaf surfaces (abaxial and adaxial). As the canopy had a certain symmetry, only the right side was used as the external part; however, applications were performed on both sides of the crop row, following a practice commonly adopted in commercial crops.

For the experiment performed at a height of 0.7 m, each experimental unit was divided into 6 sampling points on the inside and an equal number on the outside of the canopy. For the experiments at plant heights of 1.4 and 2.1 m, each experimental unit was divided into 9 sampling points on the inside and an equal number on the outside of the canopy (

Figure 2). At each sampling point, a leaf was randomly chosen, to which filter paper (3 × 3 cm) was attached to both the adaxial and abaxial surfaces of the same leaf.

As a marker, the fungicide Status SC (350 g L

−1 copper oxychloride) was added to the spray solution at concentrations of 2.0 mL L

−1 for the SFH treatment, 4.0 mL L

−1 for the RVH treatment, and 8.0 mL L

−1 for the PAEA and PAA treatments. The difference in marker concentration between the treatments was a function of the variation in spray rate, resulting in values close to those of the marker mass per crop area. During the application process, the temperature and relative humidity inside the greenhouse were monitored (

Table 2).

After spraying, the filter papers were removed from the leaves and placed individually into 100 mL plastic bottles. Subsequently, 20 mL of 1.0 M L

−1 nitric acid solution was added to each flask, which was then shaken on an orbital shaker for 15 minutes at 220 rpm to remove the marker. The resulting stirring liquid was analyzed using a Shimadzu

® atomic absorption spectrophotometer, model AA-6300, to quantify the concentration of copper (Cu) ions, following the methodologies described by Braekman et al. [

16] and Christovam et al. [

17].

Once the concentration values were obtained, the mass of metallic copper captured per artificial target area (µg cm

−2) was determined by Equation 2.

where

D is the metallic copper deposit (µg cm

−2), [ ] is the concentration in the sample (mg L

-1),

is the volume of the solution used in the removal (mL), and

is the surface area of the artificial target (cm

2).

Multiplying the actual spray rate (L ha

−1) (

Table 1) by the concentration of the tracer added to the spray solution (mL L

−1), the actual marker mass per area (mg ha

-1) was obtained. Then, correction factors were established to normalize the marker mass per area (mg ha

−1) across treatments and to correct for differences resulting from minor errors in operator displacement speed. For this, the value of the treatment that applied the highest marker mass per area (mg ha

−1) was divided by the mass applied in the respective treatment. Subsequently, the deposition data (µg cm

−2) of each treatment were multiplied by their respective correction factors.

Soil losses were evaluated concomitantly with the spray deposition evaluations. Immediately before the application of the treatments, circular filter paper targets (8.5 cm diameter) were placed in Petri dishes, which were positioned on the ground, below the plants (in the crop row) and between crop rows of the greenhouse (

Figure 2). In each experimental unit, three Petri dishes were placed below the plants and three between crop rows, always spaced 2 m apart.

In the laboratory, the filter paper was removed from the Petri dish, divided into six equal parts to facilitate the removal of the cupric marker, and placed in 100 mL flasks. Subsequently, 35 mL of 1.0 Mol L−1 nitric acid extractant solution was added to remove the marker. The quantification of the marker was performed using the same methodology described above for depositing the marker into the canopy.

2.4. Evaluation of Spray Coverage

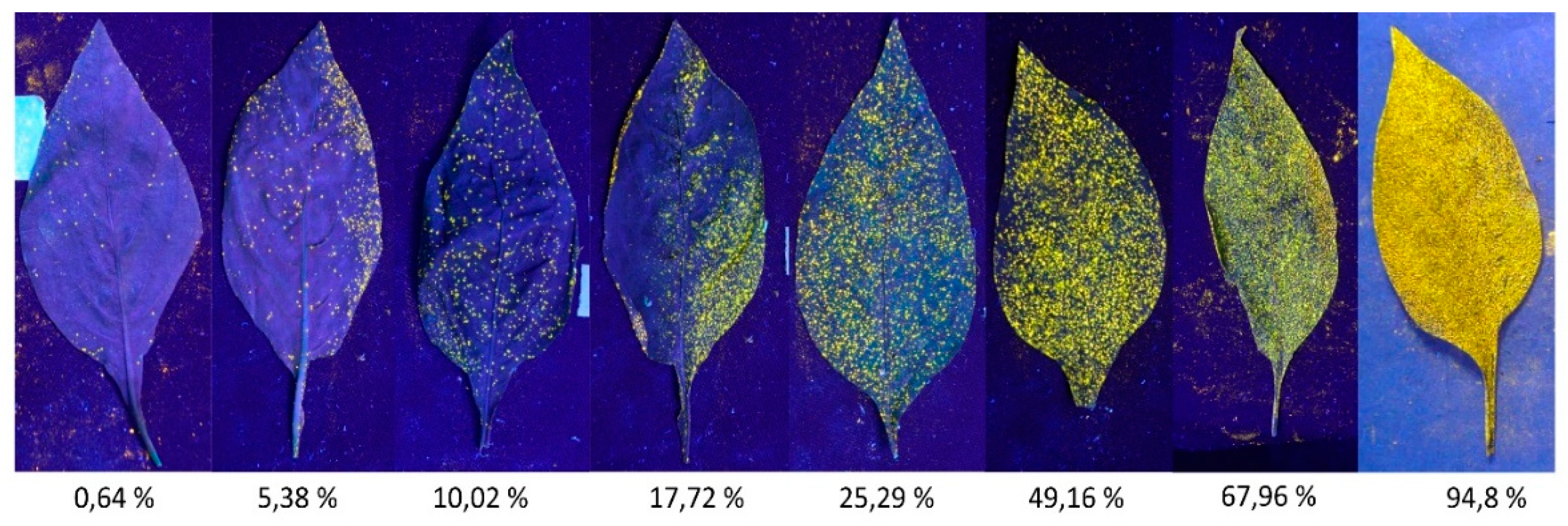

Spray coverage was evaluated only at the highest plant growth stage (2.1 m) in both seasons, concomitantly with the deposition evaluations. The sampling points were arranged in the same manner for evaluating the deposition.

To evaluate the coverage, the marker fluorescent yellow FD&C Yellow n.5 was added to the spray solution at a concentration of 7.0 g L−1. The evaluation was performed by the percentage of leaf coverage with the marker. The concentration was established in previous tests, aiming to obtain adequate visualization of the marker in the sprays using the electrostatic equipment, which produces extremely fine droplets that are difficult to visualize.

Immediately after applying the treatments, at each evaluation point, a leaf was randomly collected and stored in a paper bag (10 × 25 cm). To visualize the fluorescent marker on the leaves, an environment devoid of natural light was used, with a projection of ultraviolet light (BL 15 BLB). The percentage of the surface covered by the marker was visually determined by two people (double-blind) by comparing the sprayed leaves with a previously established scale of absolute coverage levels (

Figure 3).

To establish this scale, eight sprayed leaves were selected under the same conditions as in the experiment, ensuring they presented different levels of coverage. The selected leaves were photographed in the same visual evaluation environment as the coverage, using a Nikon D5100 digital camera with an 18-55 mm lens, at a distance of 0.30 m, without flash and a zoom level defined according to the focus setting, obtaining images in JPEG format at a resolution of 350 dpi. Subsequently, the images were subjected to the software Assess® version 2.0 (Lamari, Department of Plant Science, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) to quantify the percentage of the leaf covered by the marker.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

For spray deposition and spray coverage, data were analyzed separately for each canopy depth (internal and external) and leaf surface (abaxial and adaxial). Regarding soil loss, the data for each position (below the plants and corridor) were analyzed separately.

The normality of all data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test (p > 0.05), and the homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene’s test.

The deposition and soil loss data did not exhibit a normal distribution; therefore, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test (p < 0.05) was applied to verify the differences between the treatments. When significant, the medians were differentiated by a Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test (p < 0.05).

The coverage data were normal with homogeneous variances. Therefore, a combined analysis of variance (p < 0.05) was applied for the 2019 and 2020 crop seasons, following the criteria proposed by Pimentel Gomes [

18]. The combined means of the treatments were compared using the least significant difference (LSD) test at a significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Spray Deposition in the 2019 Crop Season

The effects of the application treatments on spray deposition levels varied among plant heights, canopy depths, and leaf surfaces. Therefore, the results are presented and discussed separately, aiming to elucidate the characteristics of the application treatments at the different plant positions.

On the leaf adaxial surface in the external part of the canopy, the PAA treatment resulted in lower deposition values than the other treatments, except at a plant height of 0.7 m, where it did not differ from those of the PAEA and RVH treatments. However, it was still lower than the SFH treatment (

Table 3).

Regarding the adaxial surface, in the internal part of the canopy, treatments with hydraulic sprayers (SFH and RVH) were superior to pneumatic sprayers (PAEA and PAA), resulting in higher spray deposition. This finding was consistent across all plant heights and may have occurred because the pneumatic treatments produced smaller droplet sizes. When spraying sweet pepper plants, the droplet is launched horizontally; therefore, it must overcome air resistance to reach the innermost part of the canopy. Smaller droplets have more difficulty overcoming gravitational resistance due to their lower mass, which may hinder their penetration into the canopy, even with the additional energy provided by air assistance in the pneumatic sprayer (

Table 3).

According to Holterman [

19], when a droplet is projected horizontally, it decelerates, and the total distance traveled horizontally is referred to as the stopping distance. Additionally, the literature reports that smaller droplets have a greater potential for evaporation loss and/or deviation from their trajectory [

19,

20,

21].

When considering the deposition of spray on the adaxial surface at both canopy depths (internal and external), it was observed that the use of electrostatic charges increased deposition compared to pneumatic treatments without electrostatic charges on the external part of the canopy. This fact indicated that the pneumatic equipment provided deposition values equivalent to the hydraulic equipment at all stages of plant development, using only 25% of the SFH spray rate. In contrast, in the internal part of the canopy, there was no advantage to using electrostatic charges (

Table 3). Electrostatic spraying is more efficient at the ends of plants positioned closer to the spray nozzle [

22,

23]. Cerqueira et al. [

23] reported that electrostatic spraying treatment was more effective in increasing spray deposition in the upper stratum of chrysanthemum plants. In contrast, in the middle and lower stratum, which are located internally in the canopy, there was no advantage when electrostatic spraying was used.

The increased spray deposition on the canopy outside from electrostatic spraying occurred because an object with an electrical charge tends to discharge into the nearest grounded body [

24]. Thus, in sweet peppers, the droplets were released horizontally, as the external part of the canopy, closest to the spray nozzle, allowed for greater deposition with the use of PAEA compared to PAA (

Table 3).

Compared to adaxial surface deposition, abaxial surface deposition showed a more significant distinction between the different heights of the canopy. At a height of 0.7 m, there was no difference between treatments in the external part of the canopy. At 1.4 m, the pneumatic application treatments (PAEA and PAA) were superior to the hydraulic treatments (SFH and RVH). At a height of 2.1 m, the RVH treatment provided the lowest deposition amount, and the deposition amounts of the other treatments did not differ significantly from one another (

Table 3).

Within the internal part of the canopy, there were no differences between treatments for plants at 0.7 m. At 1.4 m, the PAEA treatments resulted in the greatest deposition amount, while the deposition amounts of the other treatments did not differ significantly from each other. At a height of 2.1 m, the SFH treatment performed better than the RVH and PAA treatments but was no different from the PAEA treatment (

Table 3).

In summary, for the abaxial leaf surface, the RVH treatment resulted in the smallest deposition amount, except at the lowest plant height, where no differences in deposition amounts were observed. Thus, a 50% reduction in the SFH spray rate compromised deposition on this leaf surface, contrasting with the results on the adaxial surface, where the lower spray hate had no detrimental effect on deposition.

In contrast, the PAEA treatment resulted in the greatest deposition amounts on the abaxial surface, indicating that the use of electrostatic charges can enhance deposition on this leaf surface. These results are in agreement with those of studies conducted on various crops in the open field, where electrostatic charges increased deposition on the abaxial surface of leaves [

15]. Studies conducted on pepper and tomato crops in greenhouses have shown that low deposition amounts occur on the abaxial surfaces compared to those on the adaxial surfaces [

1,

6,

7,

9]. In this sense, it was expected that the spraying technique that provides higher deposition on this surface could optimize the pesticide performance, especially considering that most pests and diseases, which are difficult to control in sweet peppers, occur on the abaxial surface of leaves such as nymphs of the whitefly

Bemisia tabaci biotype B [

25], and the powdery mildew

Oidiopsis taurica [

26].

3.2. Spray Deposition in the 2020 Crop Season

In 2020, the results showed some differences compared to those obtained in the 2019 crop season. On the adaxial surface of the leaves, when comparing only the application treatments with the hydraulic sprayer (SFH and RVH), both in the external and internal parts of the canopy, there was no difference in deposition amounts, regardless of plant height, corroborating the results found in the 2019 crop season. (

Table 4).

When comparing only the pneumatic treatments on the adaxial leaf surface, the use of electrostatic charges increased the deposition only at the lowest plant height (0.7 m), on the external position of the canopy, and at the highest (2.1 m), in the internal position of the canopy. In the other situations, the deposition amounts observed in PAEA and PAA were equal (

Table 4). These results differ from those obtained in the 2019 crop season, where electrostatic charges increased the deposition amount in the external position of the canopy compared to pneumatic treatments without electrostatic charges, regardless of plant height (

Table 3).

Studies have shown that the effect of electrostatic charges on spraying is quite variable under different conditions due to several factors [

27,

28]. For example, the inclination of leaves towards the horizontal plane can increase deposition on the adaxial surface [

29]. Another study demonstrated a positive correlation between the water content of leaves and the deposition of electrically charged droplets [

28].

Many variables are involved in the deposition of electrically charged droplets, which may explain the differences between evaluated stages and crop seasons in the present study. Additionally, there was an inconsistency in the results of studies evaluating the effect of electrostatic spraying on the qualitative and quantitative parameters of spraying and the biological efficacy of pesticides. The variables that caused the differences in deposition levels mentioned above are not typically discussed in most studies of application technology.

Regarding the abaxial leaf surface, consistent with the results for the 2019 crop season, the 2020 crop season's results showed a greater distinction between plant heights. At a height of 0.7 m, compared to the hydraulic treatments, the pneumatic treatments resulted in significantly greater deposition amounts at both canopy heights. Thus, although pneumatic spraying reduced the deposition amount on the adaxial surface, there was an increase in the amount on the abaxial surface (

Table 4). As previously discussed, increasing the deposition on the abaxial leaf surface is necessary when applying pesticides since spray droplets have more difficulty reaching this surface on sweet peppers [

6].

At a height of 1.4 m in the external position of the abaxial canopy, the RVH treatment showed the lowest deposition amount. In contrast, the other treatments did not differ significantly from each other. Within the internal position of the canopy, the SFH and PAEA treatments did not differ significantly from each other and yielded superior results compared to the RVH and PAA treatments. At 2.1 m, in the external position of the abaxial leaf surface, the treatment SFH showed the higher deposition amounts differing significantly from RVH. No significant differences were found on the abaxial surface of the internal canopy position (

Table 4).

The differences in the effect of the application treatments at the different plant heights and in different crop seasons likely occurred because the canopy characteristics were distinct. The LAI was lower in 2020 than in the 2019 crop season for all plant heights (

Table 1). In addition to the LAI, other canopy characteristics, such as leaf density and leaf arrangement, may change from one season to another or even between crop development stages, which may directly influence spray deposition [

30].

Although the experiment was conducted in a protected environment, the greenhouse's structure did not effectively control meteorological variables, including temperature and air relative humidity. These factors can cause physiological changes in crops, affecting canopy characteristics [

31,

32,

33]. The differences mentioned above emphasize the importance of replicating application treatment experiments at various crop stages of development and across different seasons to prevent inconsistent conclusions.

Although differences were detected based on plant heights and crop seasons, some results were consistent. The RVH treatment, despite maintaining a deposition amount equivalent to SFH on the adaxial leaf surface, did not perform well on the abaxial surface. The PAEA treatment provided the most significant spray deposition on the abaxial leaf surface. The spray deposition amount of PAA was never superior to PAEA treatment, considering the two seasons and canopy positions evaluated, indicating that electrostatic charge is essential for enabling the use of a pneumatic sprayer in sweet pepper cultivation under a greenhouse environment.

3.3. Spray Coverage in the 2019 and 2020 Crop Seasons

According to the combined analysis of variance, there was no difference in coverage between crop seasons, and no interaction was found between seasons and treatments. However, there were differences between the application treatments, except on the abaxial leaf surface in the internal canopy position. On the adaxial leaf surface of the external and internal canopy position, the SFH treatment resulted in a greater level of coverage compared to the other treatments, which did not differ significantly from each other (

Table 5).

These results contradict those obtained in the depositions from both crop seasons (2019 and 2020), where no significant difference was found between the treatments using hydraulic sprayers (SFH and RVH). Thus, although the reduction in the spray rate did not affect the amount of deposition on the adaxial leaf surface, the distribution (coverage) was impaired.

Several studies have demonstrated that higher spray rates lead to improved coverage [

1,

9,35]. Nevertheless, studies show that spraying coverage is related not only to the spray rate but also to other factors, such as spray nozzle, droplet size, work pressure, and the interaction between droplets and the target surface [

1,

9,

10,35]. Furthermore, techniques such as air assistance and electrostatic charges resulted in changes in coverage levels [

1,

23,35].

Consistent with the previous information, when comparing only the RVH treatment with the pneumatic treatments (PAEA and PAA) on the adaxial leaf surface, it was observed that although the RVH treatment delivered twice spray rate, did not show difference in spray coverage between them, which may have occurred because the smaller droplet size of these treatments and the air assistance of the pneumatic treatments (

Table 5).

Regarding the abaxial leaf surface in the external position of the canopy, the PAEA treatment resulted in the highest coverage (42%), followed by the SFH and PAA treatments, which provided moderate coverage amounts. The RVH treatment provided the lowest coverage amount, at 24% (

Table 5). Thus, in agreement with the deposition data, the use of the pneumatic treatment using electrostatic charges may be an alternative for improving application quality on the abaxial leaf surface, especially in the external canopy position.

Achieving adequate coverage on the abaxial leaf surface is one of the main challenges of the pesticide application program [

9]. Thus, it is suggested that the pneumatic treatment using electrostatic charges be used as an alternative to improve the quality of application on the abaxial leaf surface. This approach may significantly contribute to the biological efficacy of pesticides in controlling pests and diseases that are preferentially located on the abaxial surfaces of pepper leaves.

3.4. Spray Losses to the Ground

The effects of the application treatments on ground losses varied among sampling sites, plant heights, and crop seasons. Mainly, in the position below the plants, the median values of the losses were high, being numerically similar to the deposition amounts in the canopy (

Table 6). High losses to the ground have been observed in several studies conducted on crops in protected environments [

6,

7,

8]. These results are concerning because pesticides deposited on the ground can lead to environmental contamination and fail to control pests or diseases.

In sweet peppers, the leaves of the lower plant stratum are close to the ground; therefore, it is necessary to direct the spray jet at them to ensure coverage of the entire plant length. This fact contributes to the intensification of the ground deposition, especially for collectors positioned below plants.

For the application performed at 0.7 m, compared to pneumatic treatment (PAEA and PAA), the SFH treatment results in the greatest losses, regardless of the soil collection site. Regarding the RVH treatment, the losses were equivalent to those in the SFH treatment at the position below the plants but lower between crop rows (

Table 6).

At a height of 1.4 m, the greatest loss occurred in the RVH treatment, regardless of the collection position on the ground, except for those between crop rows in the 2020 crop season, where no differences were observed between the application treatments. Thus, for the 2020 crop season, compared to the conventional treatment, the hydraulic sprayer with the lowest spray rate resulted in increased soil losses (

Table 6).

At a height of 2.1 m, there was a difference in losses only for the crop row in the 2020 crop season, where the SFH and RVH treatments showed higher deposition (losses) than the PAEA and PAA treatments. In general, it was observed that the most significant losses varied between the SFH and/or RVH treatments in all evaluated situations. These results indicate that the pneumatic treatments (PAEA and PAA) resulted in the fewest losses.

The smaller droplet size produced by the pneumatic treatments was likely the primary factor contributing to lower deposition amounts on the soil. Sánchez-Hermosilla, et al. [

13] also observed decreased losses to the soil by reducing the droplet size. The authors attributed this fact to the greater evaporation potential of the fine droplets before reaching the soil surface.

When comparing only the pneumatic treatments with each other, the use of electrostatic charges did not change the amount of losses compared to the treatments without electrostatic charges (PAA), regardless of plant height and position in the soil. For crops grown in a protected environment, there are still few studies that evaluated the effect of electrostatic charges on ground losses, making it impossible to compare the present results with those in the literature.

4. Conclusions

The effects of application treatment on spray deposition vary as a function of plant height, canopy depth, and leaf surface. Hydraulic spraying with a variable spray rate, adjusted according to crop height (SFH), resulted in the most significant deposition on the adaxial leaf surface. At the same time, the pneumatic treatment with electrostatic charges (PAEA) resulted in the greatest amounts of spray deposition on the abaxial leaf surface in sweet pepper.

The use of PAEA spraying improved spray coverage on the abaxial leaf surface of the external canopy but did not enhance coverage on the inside of the canopy in the sweet pepper crop grown in a protected environment. The 50% reduction in the spray rate of the hydraulic sprayer compared to the SFH resulted in reduced spray deposition amount and coverage. The pneumatic sprayers, with or without an electrostatic charge (PPA and PAAE), decreased the volume of spray solution lost to the ground.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D. and C.G.R.; methodology, G.D.; C.G.R.; L.D.B.J.; software, G.D. and M.M.N.; preparation and production of the spray coverage scale, F.N.S. and F.A.S.O.; formal analysis, M.M.P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D. and J.F.V.S.; writing—review and editing, C.G.R. and E.P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available by request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

To the Higher Education Personnel Improvement Coordination - Brazil (CAPES) - Financing Code 001.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SFH |

Standard Farmer Hydraulic |

| RVH |

Reduced Volume Hydraulic |

| PAEA |

Pneumatic with Air and electrostatic Assistance |

| PAA |

Pneumatic with Air Assistance |

References

- Llop, J.; Gil, E.; Gallart, M.; Contador, F.; Ercilla, M. Spray distribution evaluation of different settings of a hand-held-trolley sprayer used in greenhouse tomato crops. Pest Management Science 2015, 72, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuyttens, D.; Windey, S.; Sonck, B. A. R. T. Comparison of operator exposure for five different greenhouse spraying applications. Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health 2004, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, R.; Rodríguez, F.; Sánchez-Hermosilla, J.; Donaire, J. G. Navigation techniques for mobile robots in greenhouses. Applied Engineering in Agriculture 2009, 25, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; et al. Comparison of a new knapsack mist sprayer and three traditional sprayers for pesticide application in plastic tunnel greenhouse. Phytoparasitica 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Lv, X.; Zheng, W. Operator dermal exposure to pesticides in tomato and strawberry greenhouses from hand-held sprayers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, V. J.; Sánchez-Hermosilla, J.; Páez, F.; Pérez-Alonso, J.; Callejón, Á. J. Assessment of the influence of working pressure and application rate on pesticide spray application with a hand-held spray gun on greenhouse pepper crops. Crop Protection 2017, 96, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hermosilla, J.; Páez, F.; Rincón, V. J.; Callejón, Á. J. Evaluation of a fog cooling system for applying plant-protection products in a greenhouse tomato crop. Crop Protection 2013, 48, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, V. J.; Grella, M.; Marucco, P.; Alcatrão, L. E.; Sanchez-Hermosilla, J.; Balsari, P. Spray performance assessment of a remote-controlled vehicle prototype for pesticide application in greenhouse tomato crops. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 726, 138509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dario, G.; Precipito, L. M. B.; Oliveira, J. V. D.; Lucilhia, L. V. D. S.; de Oliveira, R. B. Application techniques of pesticides in greenhouse tomato crops. Horticultura Brasileira, 2020, 38, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J. C.; Chechetto, R. G.; Hewitt, A. J.; Chauhan, B. S.; Adkins, S. W.; Kruger, G. R.; O'Donnell, C. C. Assessing the deposition and canopy penetration of nozzles with different spray qualities in an oat (Avena sativa L.) canopy. Crop Protection, 2016, 81, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Neto, A. M.; Cunha, G.; Olescowicz, D.; Goede, M.; Harthmann, O. E. L.; Guerra, N. Eficiência e deposição de herbicidas na cebola em função do adjuvante e da taxa de aplicação. Revista Brasileira de Herbicidas, 2018, 17, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badules, J.; Vidal, M.; Boné, A.; Llop, J.; Salcedo, R.; Gil, E.; García-Ramos, F. J. Comparative study of CFD models of the air flow produced by an air-assisted sprayer adapted to the crop geometry. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2018, 149, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benalia, S.; Mantella, A.; Sbaglia, M.; Abenavoli, L. M.; Bernardi, B. Automated fixed system specifically designed for agrochemical applications in protected crops. Agriculture, 2025, 15, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanliang, Z.; Qi, L.; Wei, Z. Design and test of a six-rotor unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) electrostatic spraying system for crop protection. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, 2017, 10, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appah, S.; Wang, P.; Ou, M.; Gong, C.; Jia, W. Review of electrostatic system parameters, charged droplets characteristics and substrate impact behavior from pesticides spraying. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, 2019, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braekman, P.; Foque, D.; Messens, W.; Van Labeke, M. C.; Pieters, J. G.; Nuyttens, D. Effect of spray application technique on spray deposition in greenhouse strawberries and tomatoes. Pest Management Science, 2010, 66, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christovam, R. D. S.; Raetano, C. G.; de Amaral Dal Pogetto, M. H. F.; Prado, E. P.; Aguiar Júnior, H. O.; Gimenes, M. J.; Serra, M. E. Effect of nozzle angle and air-jet parameters in air assisted sprayer on biological effect of soybean asian rust chemical protection. Journal of Plant Protection Research, 2010, 50, 347–353. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, F. P. Curso de Estatística Experimental, 2nd ed.; Nobel: Piracicaba-SP, Brazil, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Holterman, H. J. Kinetics and evaporation of water drops in air. Wageninger: IMAG, 2003.

- Becce, L.; Mazzi, G.; Ali, A.; Bortolini, M.; Gregoris, E.; Feltracco, M. . & Gambaro, A. Wind tunnel evaluation of plant protection products drift using an integrated chemical–physical approach. Atmosphere, 2024, 15, 656. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, R.; Moraes, H.; Freitas, M.; Lima, A.; Furtado Júnior, M. Effect of nozzle type and pressure on spray droplet characteristics. Idesia, 2021, 39, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, T.; Costa, I. F.; Lenz, G.; Zemolin, C.; Marques, L. N.; Stefanelo, M. S. Equipamentos de pulverização aérea e taxas de aplicação de fungicida na cultura do arroz irrigado. Revista Brasileira Engenharia Agrícola Ambiental, 2011, 15, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, D. T. R. D.; Raetano, C. G.; Pogetto, M. H. F. D. A. D.; Carvalho, M. M.; Prado, E. P.; Costa, S. Í. D. A.; Moreira, C. A. F. Optimization of spray deposition and Tetranychus urticae control with air assisted and electrostatic sprayer. Scientia Agricola, 2017, 74, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, R. S.; Teixeira, M. M.; Fernandes, H. C.; Monteiro, P. M. D. B. Deposição e uniformidade de distribuição da calda de aplicação em plantas de café utilizando a pulverização eletrostática. Ciência Rural, 2013, 43, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanela, T. L. M.; Baldin, E. L. L.; Pannuti, L. E.; Cruz, P. L.; Crotti, A. E. M.; Takeara, R.; Kato, M. J. Lethal and inhibitory activities of plant-derived essential oils against Bemisia tabaci Gennadius (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) biotype B in tomato. Neotropical Entomology, 2016, 45, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guigón López, C.; Muñoz Castellanos, L. N.; Flores Ortiz, N. A.; González González, J. A. Control of powdery mildew (Leveillula taurica) using Trichoderma asperellum and Metarhizium anisopliae in different pepper types. BioControl, 2019, 64, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appah, S.; Wang, P.; Ou, M.; Gong, C.; Jia, W. Review of electrostatic system parameters, charged droplets characteristics and substrate impact behavior from pesticides spraying. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, 2019, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, K.; Chen, C.; Ahmad, F.; Qiu, B. Influence of plant leaf moisture content on retention of electrostatic-induced droplets. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 11685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maski, D.; Durairaj, D. Effects of charging voltage, application speed, target height, and orientation upon charged spray deposition on leaf abaxial and adaxial surfaces. Crop Protection, 2010, 29, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcerá, C.; Fonte, A.; Salcedo, R.; Soler, A.; Chueca, P. Dose expression for pesticide application in citrus: influence of canopy size and sprayer. Agronomy, 2020, 10, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, L. S.; de Azevedo, C. A.; Albuquerque, A. W.; S Junior, J. F. Leaf area index and productivity of tomatoes under greenhouse conditions. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, 2013, 17, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.; Zamban, D. T.; Prochnow, D.; Caron, B. O.; Souza, V. Q.; Paula, G. M.; Cocco, C. Caracterização fenológica, filocrono e requerimento térmico de tomateiro italiano em dois ciclos de cultivo. Horticultura Brasileira, 2017, 35, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedó, T.; Medeiros, L. B.; Rolim, J. M.; Peter, M.; dos Santos Pereira, L. H.; Martinazzo, E. G. ; .. & Mauch, C. R. Correlação entre caracteres fisiológicos e agronômicos para tomateiro. Revista de la Facultad de Agronomía, 2021, 120, 68–68. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, R. P.; Cunha, J. P. D.; Guimarães, E. C.; Santana, D. G. D.; Assunção, H. H. D. Multivariate analysis applied to spray deposition in ground application of phytosanitary products in coffee plants. Engenharia Agrícola, 2021, 41, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).