1. Introduction

Nutrition and diet are key to individual health and socioeconomic stability. Despite advances in agriculture and food distribution, global food security remains a challenge. While many people have access to a rich diet, about one in nine people worldwide suffer from hunger or malnutrition. This problem affects not only developing countries but also affluent countries, underscoring the need for action to improve food availability and quality [

1]. Potatoes are one of the most widely cultivated and consumed crops in the world, being a staple food and a key ingredient in various processed products [

1,

2,

3]. However, post-harvest deterioration of tuber quality, in particular darkening of the flesh of raw and cooked tubers and changes in the texture of cooked tubers, remains a major concern for producers and consumers [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Darkening of the flesh of raw tubers, often caused by enzymatic browning and oxidative processes, can significantly affect the visual attractiveness and market value of potatoes [

7,

9]. The darkening of potato tuber flesh after cooking is the result of chemical reactions between phenolic compounds, such as chlorogenic acid, and metal ions, mainly iron. While cooking, chlorogenic acid can react with iron, leading to the formation of dark color complexes, which manifests itself as an undesirable coloration of the flesh [

4,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The intensity of this phenomenon can be intensified by the high content of nitrates in the tubers, which is often the result of excessive nitrogen fertilization. Additionally, improper storage conditions of potatoes, such as too low a temperature, can promote darkening of the flesh after cooking [

5,

8]. Darkening of the flesh of potatoes, both raw and cooked, is a significant problem affecting their visual attractiveness and market value. This process results from enzymatic and chemical reactions occurring in tubers, and its intensity depends on many factors, such as potato variety, cultivation conditions, storage method, and chemical composition of tubers [

2,

7,

9].

Enzymatic darkening in raw tubers is caused by the action of tyrosinase, an enzyme that oxidizes tyrosine to melanin, which leads to the formation of dark spots. The intensity of this process depends on the content of reaction substrates and enzyme activity, which are modified by environmental conditions. High temperatures and large amounts of rainfall during the growing season can increase the tendency to darken. Excessive nitrogen fertilization and potassium deficiency also favor this phenomenon [

4,

7,

8,

9,

15].

Non-enzymatic darkening in cooked tubers results from chemical reactions between iron ions and chlorogenic acid, leading to the formation of dark complexes. The presence of compounds such as citric, ascorbic, or malic acid may limit this phenomenon by binding to iron ions and inhibiting the darkening reaction. The ratio of chlorogenic acid to citric acid in tubers plays a key role in the intensity of darkening after cooking [

5,

8,

9,

16]. Similarly, the degradation of tuber flesh texture, which is influenced by starch composition and cell wall integrity, plays a key role in determining the suitability of potatoes for the processing industry [

1,

2]. In recent years, the use of effective microorganisms (EM) has become a promising approach to improving soil health, improving plant growth, and mitigating post-harvest quality problems. EM, which consist of beneficial bacteria, fungi, and yeasts, have been shown to affect nutrient uptake, enzymatic activity, and crop stress resistance. By modulating soil microbial communities and optimizing plant physiology, EM applications can help reduce enzymatic browning and maintain desirable textural properties of harvested potato tubers [

9].

Darkening of the flesh of raw potato tubers is an important quality parameter that affects visual appeal and consumer acceptance. This process, also known as enzymatic oxidation, is associated with the activity of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) and the oxidation of phenolic compounds to melanin’s [

4,

7,

10,

11,

15,

17,

18]. It occurs mainly before cooking (e.g. during peeling, cutting) [

16]. The reaction is the result of the PPO enzyme, which oxidizes polyphenols to quinones → these polymerize to melanin (dark pigments). Cooking usually deactivates PPO, so this type of darkening does not dominate after cooking, but it can happen with insufficient cooking time or steaming [

9]. After cooking darkening is a complex biochemical process that occurs after heat treatment and during cooling of the tubers. This phenomenon is undesirable, especially in the food industry (e.g. in the production of salads, frozen foods), because it deteriorates the appearance of the product. The main cause of darkening after cooking, called non-enzymatic darkening (dominant after cooking), are chemical reactions related to the oxidation of iron and chlorogenic acid (present in potatoes). The mechanism of this darkening is that during cooking, chlorogenic acid forms complexes with iron (Fe²⁺ or Fe³⁺), especially at higher pH. After cooking and cooling, in the presence of oxygen, these complexes oxidize to dark compounds (dark, blue-gray, or brown spots) [

16]. The reactions occur without enzymes, therefore they are typical after cooking, when enzymes are already inactivated. The darkening of cooked potato flesh is mostly influenced by the content of potassium, magnesium, and boron in the tubers [

4,

7,

9,

11,

15]. This study evaluates the role of EM in potato cultivation and its effect on darkening of raw and cooked tuber flesh and on the texture of cooked tuber flesh. By analyzing the biochemical and physiological responses of potatoes to EM, we aim to understand how microbiological technology can improve postharvest tuber quality. Understanding these mechanisms will allow for the development of sustainable and natural methods for improving potato quality, which is crucial for producers and consumers. Hence, the aim of the study was to determine the effect of Effective Microorganisms (EM) on the quality of raw and cooked potato tubers and to conduct a rheological analysis of selected varieties in terms of their suitability for consumption and processing. Justification of the aim of the work: EM are increasingly used in agriculture as biostimulants affecting plant growth, soil health and crop quality. However, their effect on the physical and technological properties of potatoes is not yet well understood. In particular, the darkening of the flesh of cooked tubers and their rheological parameters are of key importance for both consumers and the processing industry, affecting the appearance, texture, storage durability and the possibility of using tubers for the production of French fries, crisps or mashed potatoes. Conducting research on a set of different potato varieties allows for the identification of potential relationships between EM and potato quality traits. Rheological analysis of tuber flesh texture provides valuable information on tuber behavior during cooking and processing, which can be of practical importance to food producers and growers. The results of this study can help optimize EM application technologies and select varieties that respond best to EM, supporting sustainable production of high-quality food.

Therefore, a research hypothesis was put forward against the null hypothesis.

Alternative research hypothesis (H₁): The use of Effective Microorganisms (EM) in potato cultivation reduces flesh darkening and improves tuber texture by influencing enzymatic metabolism and structural properties of the tissue.

Null hypothesis (H₀): The use of Effective Microorganisms (EM) in potato cultivation has no significant effect on flesh darkening and tuber texture after harvest.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted as a field experiment between 2017 and 2019 in Parczew, central-eastern Poland (51°38'24" N, 22°54'02" E). The experiment was carried out using the randomized block method, in a dependent design, split plot, in three replications. The first-order factor was the pre-planting treatments consisting in soaking the seed potatoes in an aqueous solution of the EM Farming preparation: a) exposure 10 minutes, exposure b) 20 minutes; c) control treatment with soaking the seed potatoes in distilled water. The second-order factor was 14 potato varieties, all earliness groups: Krasa (very early); Bellarosa, Ewelina, Korona, Nora, Vineta (early); Roxana, Nicola, Red Fantasy, Zuzanna (medium early), Czapla, Jelly, Oktan (medium late) and Hinga (late).

2.1. Characteristics of Potato Varieties

Bellarossa (Europlant, Germany) – Early, edible, general use. Very large, round-oval tubers, red skin, yellow flesh. Yielding, high share of marketable fraction. Very susceptible to potato blight, resistant to leafroll virus (PLRV) and potato cyst nematode [

19].

Czapla (PMHZ Strzekęcin, Poland) – Medium late, edible, type C. Large, shapely tubers, yellow skin, light yellow flesh. Very fertile. Medium resistance to blight and PLRV, resistant to PVY and potato cyst nematode [

19].

Ewelina (Europlant, Germany) – Early, edible, slightly floury. Large, shaped like tubers, yellow flesh. Very fertile. Susceptible to potato blight and PVY, resistant to leafroll virus and potato cyst nematode [

20].

Hinga (PMHZ Strzekęcin, Poland) – Late, high starch. Medium tubers, round-oval, yellow skin, light yellow flesh. Resistant to PVY virus, medium resistance to leaf blight and leafroll virus (PLRV), susceptible to potato cyst nematode [

19].

Jelly (Europlant, Germany) – Medium late, edible. Very large tubers, oval-oblong, yellow flesh. Yielding. Resistant to potato cyst nematode, medium resistance to PVY and PLRV viruses, susceptible to blight [

21].

Korona (HZ Zamarte, Poland) – Early, edible, salad and general use (AB). Very large, round-oval tubers, light yellow flesh. Yielding, resistant to potato cyst nematode and PVY virus, medium resistance to PLRV virus, susceptible to blight [

19].Krasa (Europlant, Czech variety) – Early, edible, salad and general use (AB). Very large tubers, yellow flesh. Yielding. Resistant to potato cyst nematode, medium resistance to PLRV virus, susceptible to blight [

21].Nicola (Europlant, Germany) – Medium early, edible, salad (A). Large, elongated-oval tubers, yellow flesh. Yielding. Resistant to potato cyst nematode, medium resistance to Y virus, susceptible to PLRV, resistant to potato cancer [

21].

Nora (Europlant, Germany) – Early, edible, universal, slightly floury. Very large, elongated-oval tubers, yellow flesh. Yielding. Resistant to potato cyst nematode, medium resistance to PVY and PLRV viruses, susceptible to blight [

19].

Oktan (Europlant, Germany) – Medium late, starchy, BC/C. Round-oval tubers, light yellow flesh. Resistant to potato cancer and potato cyst nematode. Requires better soil [

21].

Red Fantasy (Europlant, Germany) – Medium early, edible (B). Large, elongated-oval tubers, red skin, dark yellow flesh. Yielding. Resistant to potato cyst nematode, high resistance to PVY and PLRV viruses, resistant to blight [

21].

Roxana (Europlant, Germany) – Medium early, edible. Very large, oval tubers, yellow flesh. Yielding. Resistant to potato cyst nematode, medium resistance to leafroll virus, susceptible to blight [

21].

Vineta (Europlant, Germany) – Early, edible (B-AB). Large, oval tubers, yellow flesh. Resistant to potato cyst nematode, high resistance to PVY and PLRV viruses, very susceptible to blight [

19].

Zuzanna (Europlant, Germany) – Medium early, starchy (19% starch). Medium to large tubers, round-oval, light yellow flesh. Yielding. Resistant to potato cyst nematode and PVY virus, medium resistance to PLRV, low resistance to late blight [

21].

2.2. Characteristics of Effective Microorganisms

EmFarma Plus: Microbial Biopreparation for Sustainable Agriculture. EmFarma Plus is an advanced biopreparation based on natural fermentation, which is a key tool in sustainable agriculture. Its unique formula is based on a synergistic composition of live, beneficial microorganisms, including

Lactobacillus plantarum, organic acids, vitamins and minerals, which support biodiversity and activity of the soil microbiome [

22]. Studies indicate that EM can serve as a sustainable alternative to synthetic fungicides in potato cultivation, increasing disease suppression and promoting plants go through microbiome modulation [

23,

24].

Key properties and mechanisms of action: Composition and characteristics: The product contains diverse strains of microorganisms, such as

Lactobacillus casei, Rhodobacter spheroids, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Streptomyces griseus and

Trichoderma harzianum (manufacturer's information) [

23,

24].

A formula based on natural raw materials: water, sugar cane molasses, Kłodawa rock salt and mineral powder pH 3.0–3.5, yellow-brown liquid with a characteristic sweet-sour smell (manufacturer's information) [

25].

Effect on soil: Intensification of microbiological processes in the soil, leading to improvement of its structure and fertility. Acceleration of humification and decomposition of crop residues, increasing the content of humus and water retention. Optimization of nutrient cycling by mineralizing organic matter and releasing hard-to-reach compounds. Improvement of soil condition, increasing its porosity and permeability. Support for composting and fermentation processes, reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Soil bioremediation by accelerating the decomposition of pesticide residues [

26,

27].

Application and benefits: Soil application throughout the growing season, to improve soil health and plant yield. Recommended for use on crop residues, accelerating their decomposition and enriching the soil with organic matter. Support for sustainable agriculture by reducing the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, improving soil health and biodiversity, and minimizing the negative impact on the environment. Dilution of the preparation with distilled water to the concentration recommended by the manufacturer provides optimal conditions for the activity of microorganisms [

27].

Certification and safety: The product is approved for use in organic farming (no. SE/68/2022). Safe for people and the environment, confirmed by the PZH/HT-3112/2016 certificate (manufacturer

information) [

25].

2.3. Field Tests

Field tests were conducted in a field after the cultivation of winter triticale. After the harvest of the pre-crop, crop residues were cultivated, and in the autumn 30 tons of cattle manure per hectare were applied. The manure was mixed with the soil by deep ploughing. In spring, the field was leveled, and mineral fertilization was applied based on soil analysis, adjusting the doses to current agrotechnical recommendations. NPK fertilization was applied in a ratio of 1:1:1.5, which corresponded to 90 kg N, 90 kg P and 135 kg K per hectare. Fertilizers were applied once before planting potatoes and thoroughly mixed with the soil using a cultivator. Certified class A potato planting material was used for planting, planted manually at the end of April at a spacing of 67.5 cm × 37 cm. The area of the collective plots was 15 m². The cultivation was maintained in accordance with the principles of Good Agricultural Practice [

26,

27,

28], considering the minimization of chemical treatments and optimization of plant protection.

The integrated plant protection strategy (IPM) was used to control weeds, limiting the use of herbicides to the necessary minimum. Plateen 41.5 WG (2.0 kg ha

−1) was used before potato emergence. In the 3–5 leaf phase of monocotyledonous weeds, Leopard Extra 05 EC (2.0 dm ha

−1) was used in combination with the Olbras 88 EC adjuvant (1.5 dm ha

−1). Protection against potato beetle was based on pest monitoring and the use of selective insecticides, including Bulldock 025 EC (0.3 dm ha

−1), Karate Zeon 050 CS (0.2 dm ha

−1) and Mospilan 20 SP (0.08 kg ha

−1), considering the rotation of active substances to prevent resistance. Protection against potato blight was based on the threat forecasting system and the use of fungicides with a varied mechanism of action, including Infinito 687.5 SC (1.6 dm ha

−1), Penncozeb 80WP (2.0 kg ha−1), Curzate Top 72.5 WG (2.0 kg ha

−1) and Ekonom 72 WP (2.0 kg ha

−1) [

29], considering the principles of integrated plant protection. Potatoes were harvested in earliness groups, depending on the ripening date, in the technological maturity phase. During harvest, the tuber yield was determined, and tuber samples were taken from each plot to determine the darkening of the flesh of raw and cooked tubers. For this purpose, 30 medium-sized tubers were selected, without symptoms of greening or damage [

29].

2.4. Examination of the Darkening of the Tuber Flesh

The evaluation of the darkening of the raw tubers' flesh was performed on a longitudinal section after 10 minutes and 1 hour from cutting. The degree of darkening was determined using a 9-point European scale, which visually classifies the intensity of darkening [

29].

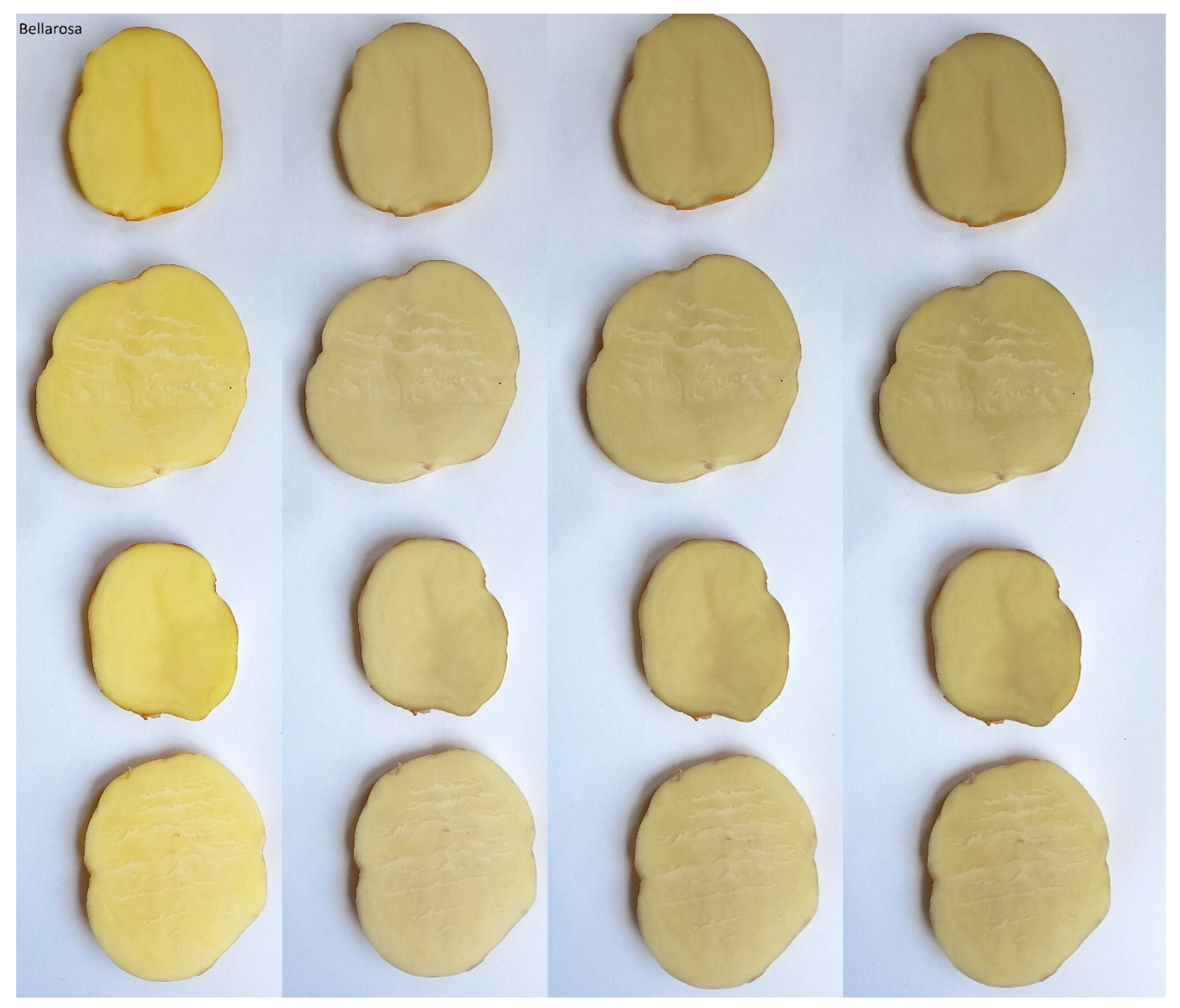

Figure 1.

Assessment of darkening of the flesh of raw tubers. Source: own.

Figure 1.

Assessment of darkening of the flesh of raw tubers. Source: own.

2.4.1. Darkening of Cooked Potato Flesh

The darkening of cooked potato flesh was assessed in the stolon and top parts after 10 minutes and 2 hours of cooking. The degree of darkening was determined using the 9-point Danish color scale [

29].

2.5. Potato Tuber Texture Analysis

Potato tuber texture, a key parameter of consumer quality, was assessed using a bidirectional texture analyzer texture CT3 (BROOKFIELD) (

Figure 2).

The analysis was carried out at the Plant Products Commodity Science Laboratory, in accordance with the Instrumental Texture Analysis (ITA) methodology, which allows for an objective assessment of the rheological properties of food products [

30]. ITA is widely used in scientific research and the food industry to assess the texture of fruits and vegetables, including potatoes [

31,

32].

The analysis parameters were set to reflect the conditions of tuber deformation during consumption and processing. A normal test was used, with the trigger force set to 0 N, which ensured precise measurement of the pressure force from the moment of contact between the probe and the sample. The deformation of the sample was 15 mm, which allowed for the assessment of the elasticity and hardness of the flesh. The speed of the probe was set to 0.5 mm/s, which minimized the effect of the deformation rate on the measurement results. The method consisted of placing cooked potato tubers of uniform thickness on the analyzer platform. After pressing the START button, the analyzer automatically recorded the following parameters: a) Peak load (maximum pressure force): Represents the maximum force required to deform the sample, which is a measure of hardness; b) Deformation (deformation): Determines the degree of sample deformation at maximum pressure force, which is a measure of elasticity; c) Work (work): Represents the energy required to deform the sample, which is a measure of cohesion; d) Final load (final pressure force): Determines the pressure force after sample deformation, which is a measure of residual elasticity. Each measurement was repeated three times, which ensured the reliability and repeatability of the results. Modern food texture research often uses Texture Profile Analysis (TPA), which provides detailed information on the rheological properties of food products [

30].Texture analysis combined with sensory analysis allows for a better understanding of consumer preferences and optimization of product quality Texture analysis combined with sensory analysis allows for a better understanding of consumer preferences and optimization of product quality [

30,

31,

32].

2.6. Soil Conditions

Field experiments conducted in 2017-2019 provided information on the content of available forms of phosphorus (P₂O₅), potassium (K₂O) and magnesium (Mg) in the soil, as well as its pH (pH measured in 1M KCl) (

Table 1).

The content of Available Nutrients was as follow:Content of available phosphorus in the soil varied between years. The highest value was recorded in 2017 (21.4 mg·100g⁻¹), and the lowest in 2019 (16.0 mg·100g⁻¹). The average phosphorus content for the entire study period was 19.2 mg·100 g⁻¹ [

33]

The content of available potassium showed an upward trend in subsequent years, from 11.8 mg·100g⁻¹ in 2017 to 13.4 mg·100 g⁻¹ in 2019. The average potassium content was 12.6 mg·100g⁻¹.

The content of available magnesium also increased during the period studied, from 4.4 mg·100g⁻¹ in 2017 to 8.2 mg·100g⁻¹ in 2018, and then slightly decreased to 7.3 mg·100g⁻¹ in 2019. The average magnesium content was 6.6 mg·100g⁻¹ [

33].

Soil acidity (pH in 1M KCl) during the period studied ranged from slightly acidic to neutral. In 2017 it was 5.8, in 2018 it increased to 6.2, and in 2019 it decreased to 6.1. The average soil pH for the entire study period was 6.0 [

33].

Summary: The results of soil analyses indicate variability in the content of available nutrients in the soil in the individual years of the study. The content of potassium and magnesium showed an upward trend, while the content of phosphorus was the most diverse. The soil pH remained at a slightly acidic to neutral level [

34].

2.7. Meteorological Conditions

The assessment of meteorological conditions during the potato growing season in Uhnin in 2017-2019 showed significant variability of weather conditions in individual years (

Table 2).

Total rainfall during the growing season was 455.5 mm. The highest rainfall was recorded in August (141.0 mm), and the lowest in April (17.2 mm). Average monthly air temperatures ranged from 9.1°C in April to 22.0°C in July. Hydrothermal conditions were varied. April was very dry (k=0.6), May and August were humid (k=2.1 and 2.2 respectively), and June, July and September were rather dry (k=1.1, 0.9 respectively). 2018: Total rainfall was 424.9 mm. The highest rainfall was recorded in July (169.6 mm), and the lowest in September (9.0 mm). Mean monthly air temperatures ranged from 9.5°C in April to 18.6°C in July. Hydrothermal conditions were variable. April and May were rather dry (k=1.3 and 1.1, respectively), June and July were wet (k=2.2 and 2.9, respectively), August was dry (k=0.9), and September was extremely dry (k=0.2). Year 2019: Total precipitation was 326.0 mm, the lowest in the studied period. The highest precipitation was recorded in June (100.7 mm), and the lowest in May (38.0 mm). Mean monthly air temperatures ranged from 9.3°C in April to 21.9°C in July. Hydrothermal conditions were varied. April was rather dry (k=1.1), May, July and September - dry (k=0.9, 0.7 and 0.9 respectively), June rather wet (k=1.9) and August rather dry (k=1.1). In summary, in 2017 and 2018 higher precipitation totals were recorded compared to 2019. Air temperatures were relatively high in July each year. The Sielianinov coefficient indicated a high variability of hydrothermal conditions, with dry and wet periods in individual months and years. The year 2018 was distinguished by an extremely dry September, while 2019 had the lowest precipitation total in the studied period. These data emphasize the importance of monitoring meteorological conditions in order to optimize potato cultivation and minimize the impact of unfavorable weather conditions.

2.8. Statistical Calculations

All data were subjected to three-way analysis of variance (technologies, genotype and years) (ANOVA) using SAS 9.2 2008 software [

36]. The significance of sources of variation was tested using the Fisher-Snedecor “F” test. To determine the share of individual sources of variation and their interactions in total variation, an assessment of variance components was performed using the following designations:

The empirical values of mean squares obtained from the analysis of variance were compared with their expected values. By solving the systems of equations, the variance components corresponding to the individual sources of variability were estimated in this way. The mutual relations between the established estimates of variance components and their percentage structure were the basis for assessing the impact of technology, varieties and years on the variability of qualitative characteristics [

37]. Normalization transformations were applied to characteristics expressed in percentages [

38]. Descriptive statistics were performed in SPSS statistical software [

38]. Pearson correlation coefficients, which measure the strength and direction of relationships between variables for normally distributed data, were calculated in SPSS Statistics [

38].

3. Results

3.1. Darkening of Raw of Tubers

The results of the assessment of potato tuber flesh darkening after 10 minutes and after 1 hour indicate significant differences between both the technologies used and the varieties (

Table 3,

Figure 3).

The technology with effective EM II organisms showed the highest stability in terms of reducing flesh darkening after 1 hour, which turned out to be significantly better, compared to the traditional technology without the use of EM. These differences after 10 minutes from cutting the tubers turned out to be statistically insignificant (

Table 3).

The worst resistance to enzymatic darkening after 10 minutes was demonstrated by Nora and Roxana. The remaining varieties were in the same homogeneous group in terms of this feature. The tests carried out after 1 hour showed that the Zuzanna and Hinga varieties obtained the best scores for flesh darkening, while the Oktan variety obtained the weakest results, which was statistically confirmed. The remaining varieties were in a homogeneous group (

Table 3).

Data analysis in 2017–2019 indicates stability of results, with a slightly higher value of tuber flesh darkening after 10 minutes observed in 2018 compared to 2017. In summary, the use of EM technology with longer exposure and the selection of varieties resistant to enzymatic darkening, such as Zuzanna and Hinga, may contribute to reducing the darkening of raw potato flesh after storage (

Table 3).

3.2. Darkening of the Tuber Flesh After Cooking

Evaluation of flesh darkening in apical part 10 minutes after cooking: All tested technologies (Traditional, EM I, EM II) and varieties and their interaction with the years of research were characterized by very similar darkening results (average values oscillating around 8.7–9.0 on a 9-point scale), which is confirmed by the letter designations "a". This means that after a short time after cooking, the differences between technologies and between individual varieties were statistically insignificant (LSD p>0.05) (

Table 4).

After 2 hours from the sectioning of the tuber flesh, the effects were mixed: the traditional technology was characterized by higher darkening values (average around 7.2–7.6), while the EM technologies (EM I and EM II) showed lower or more variable results (e.g. some measurements were 7.2 or 7.7), suggesting that the EM technology can effectively delay the darkening process with longer exposure (

Figure 4).

Additionally, the evaluation of individual varieties showed that the differences between them become more visible only after 2 hours from cooking, as confirmed by the LSD values, although after 10 minutes these differences were not significant.

3.3. Rheological Studies

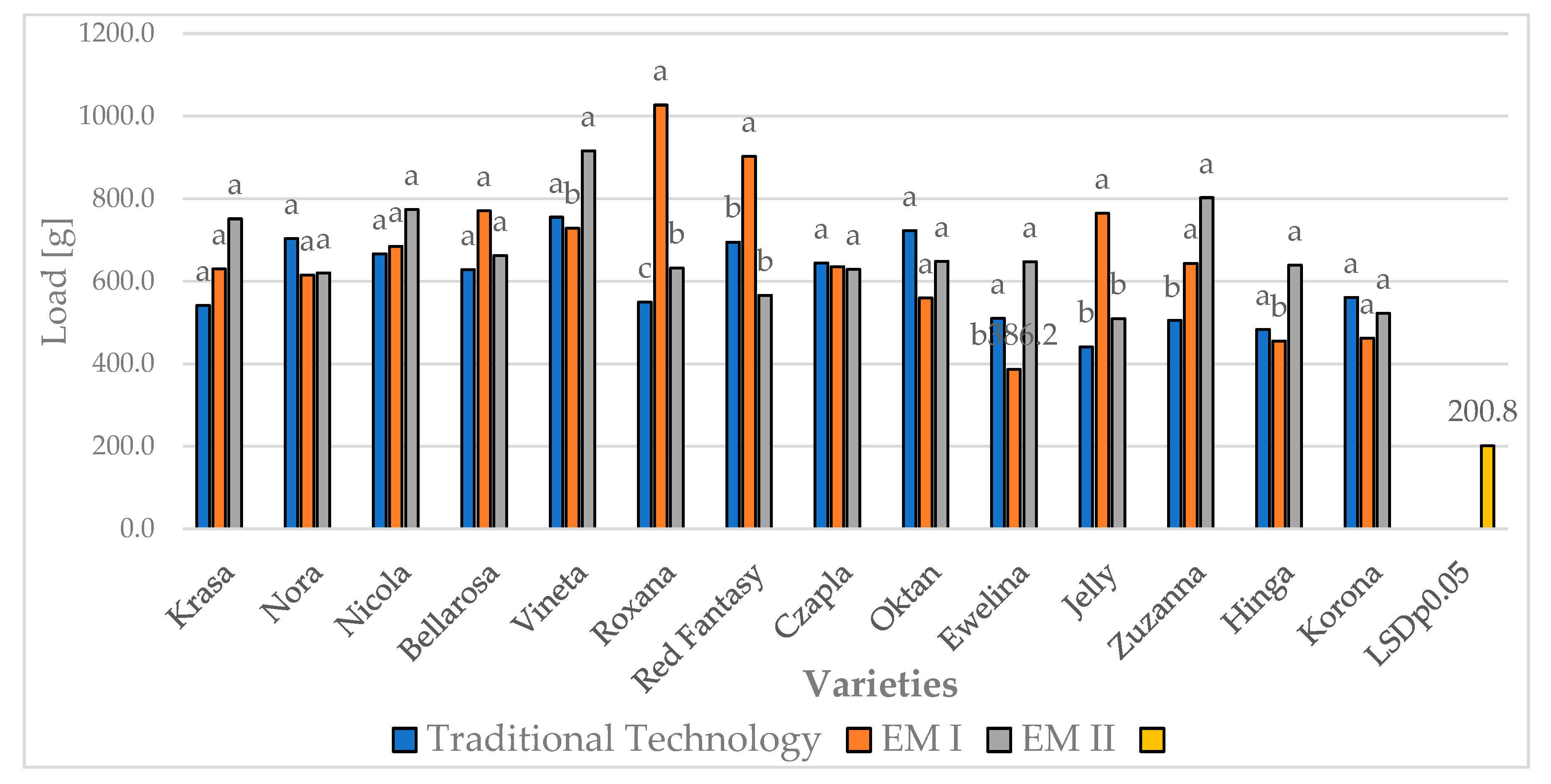

Rheological tests of the structure of cooked tuber flesh showed different results depending on the technology used and the variety (

Table 6). The aim of the study was to determine the influence of preparation technology and genetic characteristics of the varieties on selected rheological parameters, such as: work value, load, final load and load height.

Processing technologies: Three processing technologies were used in the study: Traditional technology – without the use of effective microorganisms (EM) (table 6). EM I technology – with the use of microorganisms (exposure time 10 minutes). EM II technology – with the use of microorganisms (exposure time 20 minutes).

Traditional technology showed the highest work value (19.0 MJ); however, EM I and EM II technologies significantly reduced the work value to 15.1 MJ and 15.8 MJ, respectively. The reduction in the work value in the case of EM technology may indicate a softer structure of the flesh, which in turn translates into lower energy input required for grinding (

Table 6).

Influence of variety on rheological properties: The study also included various potato varieties, including Roxana, Nicola, Vineta, Bellarosa, Krasa, Nora, Red Fantasy, Czapla, Oktan, Ewelina, Jelly, Zuzanna, Hinga and Korona. The highest work value was recorded for the Roxana variety (22.0 MJ), while the lowest for the Hinga variety (12.5 MJ). The final load value also showed great variation, with the highest value obtained for the Vineta variety (799.6 g) and the lowest for the Hinga variety (525.6 g).

Summary: The analysis of the results indicates that the technologies using EM (EM I and EM II), compared to the traditional technology, contributed to a reduction in the work value and final load, which may indicate a beneficial effect of microorganisms on improving the structure of the potato tuber flesh. The highest stability of rheological parameters in different years of the study was demonstrated by the Roxana and Nicola varieties, while the Hinga and Oktan variet9ies were characterized by lower work values, which may suggest their softer consistency after cooking (

Table 6).

The use of EM technology may be a promising method for improving the rheological properties of potato tuber flesh, especially in the context of reducing the energy needed for processing and improving the texture of the finished product. The choice of the appropriate variety and processing technology should be adapted to the planned culinary or industrial use (

Table 6).

The results obtained suggest that the reaction of potato flesh to the applied technology varies depending on the year of cultivation, which indicates a significant interaction between the technology and the environmental conditions of a given year. Examples: Work (MJ): In 2019, a significant decrease in the value of work required for deformation was observed for all technologies, particularly pronounced in the case of traditional technology (13.1 MJ), which may indicate the impact of weather conditions that year on the structure of the tubers (

Table 6).

Final load (g): The EM I and EM II technologies showed significantly higher values of the final load in 2019, compared to the traditional technology. This may suggest better maintenance of the structure under the influence of mechanical loads in EM technology (

Table 6).

Load height (mm): The traditional technology was characterized by lower values of this feature each year, but the greatest decrease was in 2019, which indicates lower elasticity or greater damage to the structure of the flesh (

Table 6).

Significance of interaction: Variety × Years. Different potato varieties reacted differently depending on the year, which may be the result of their genetic predisposition to respond to environmental conditions. For example: Work (MJ): Varieties such as: Roxana, Vineta, Nicola obtained higher work values in 2017, but significantly lower in 2019. The decreases were in the range of 50–70%, which indicates high variability over time. In turn, varieties such as: Ewelina, Jelly or Korona show smaller fluctuations over the years, which may suggest greater structural stability (

Table 6).

Final load (g): Zuzanna and Hinga varieties showed significant decreases in the value of this trait in 2019, which may indicate greater susceptibility of these varieties to stress conditions, compared to more stable varieties such as Nicola (

Table 6).

Load height (mm): Nicola and Oktan varieties were distinguished by the highest load height in each year, which may indicate their suitability for processing requiring good structure after cooking.

Figure 5 shows the influence of cultivation technology and genetic characteristics of varieties on the load of cooked tuber pulp.

The bar chart presents the results for different potato varieties using three cultivation technologies: traditional (blue bars), technology with effective microorganisms and exposure to this treatment for 10 minutes (EM I (orange bars) and technology with effective microorganisms and exposure to this treatment for 20 minutes (EM II) (gray bars). Additionally, the least significant difference (LSDp0.05) is marked on the figure in the form of a yellow bar. The letters above the bars (e.g. "a", "b", "c") indicate homogeneous groups according to the statistical analysis, which indicates the significance of the differences between the cultivation technologies in relation to a given variety.

Figure 6 shows a clear differentiation in the pulp mass between the varieties and between the cultivation technologies used. The 'EM I' technology often generates a greater load of cooked pulp compared to the traditional technology and the 'EM II' technology, which may indicate a positive effect of this technology on the quality yield. Varieties such as Roxana, Red Fantasy and Jelly showed particularly high results with the 'EM I' technology, while other varieties such as Krasa, Nora, Nicola, Bellarosa, Czapla, Oktan, Korona did not show significant differences between technologies. Varieties: Vineta, Ewelina, Hinga and Zuzanna, responded positively to technologies with effective microorganisms where seed potatoes were soaked for 20 minutes in a solution with microorganisms (EM II). In conclusion, the use of the 'EM I' technology seems to have a positive effect on cooked pulp yield in many potato varieties, which may be important from the perspective of agricultural practice and yield optimization.

Impact of cultivation technology: In most cases, EM I technology generates a higher mass of cooked pulp compared to traditional and EM II technologies. EM II technology showed an advantage in some varieties (e.g. Vineta and Nora), but this was not always statistically significant (

Figure 6).

Traditional cultivation technology usually generates lower values compared to EM technologies, which may suggest a positive effect of the use of effective microorganisms on the quality of the crop.

Impact of potato variety: There were significant differences between varieties in terms of the final load of cooked potato pulp. Varieties such as Jelly, Vineta, Ewelina and Zuzanna show particularly high final load values using EM I technology. Varieties Krasa and Roxana have clearly lower values in traditional technology compared to EM technologies (

Figure 6).

Statistical differences: Letters above bars (e.g. a, b, c) indicate homogeneous groups selected based on analysis of variance (ANOVA), which indicates statistically significant differences between technologies within a given variety.

Differences between technologies are often significant when using EM I technology compared to traditional technology.

3.4. Statistical Description and Relationships Between Flesh Darkening and Biotic and Abiotic Factors

Table 7 with Pearson correlations shows the relationships (strength and direction of dependence) between various features assessed in the study of potato chips quality and sugar content in the potato raw material. The purpose of the table is to determine which factors affect the quality of chips - including their color, appearance, taste, fat and sugar content, as well as the occurrence of defects. The table allows us to understand which features are strongly related to each other and which do not have a significant effect on each other.

The mean values of darkening of the raw flesh after 10 minutes (y1) and one hour (x1) were 8.85 and 7.65 on a 9-point scale, respectively, indicating a moderate level of darkening. In the case of cooked tubers, the darkening values varied depending on the tuber part and the time after heat treatment - lower values were recorded after 2 hours in the stolon part (x5 = 7.49) (

Table 7).

High values of the coefficient of variation were observed for rheological parameters, especially for work (x6; V = 66.40%) and load and final load (x7 and x8), which indicates high variability of the tested varieties in terms of the resistance of the pulp tissue to crushing. For darkening parameters, the coefficients of variation were much lower (e.g. for y1 V = 1.97%), which indicates a more uniform behavior of the material in this range (

Table 7).

It is also worth noting the distinct features of statistical distributions - e.g. high positive kurtosis for x2 (8.44) and strong left-sided skewness of the distributions of y1 and x2 features (-2.01 and -2.71, respectively), which suggests the presence of extremely high values in the sample. Additionally, for some features (e.g. x2) there is a high positive kurtosis (8.44), indicating a sharp, clustered distribution with the presence of outliers (

Table 7).

Skewness (distribution asymmetry) allows us to assess in which direction the feature values predominate. In the case of features related to darkening (y1, x1, x2, x3), the skewness values are negative (e.g. x2 = -2.71; y1 = -2.01), which indicates a left-sided asymmetry - i.e. the majority of observations are concentrated around higher values, while a minority are characterized by a lower degree of darkening. The opposite tendency occurs for rheological features (e.g. x6, x9), where positive skewness means that most cases are characterized by lower values, while individual samples show significantly higher ones (

Table 7).

3.5. Pearson Correlation Coefficients Between Darkening Characteristics of Raw and Cooked Potato Tuber Flesh and Rheological Properties of Cooked Flesh

Table 8 presents simple Pearson correlation coefficients between parameters describing darkening of raw and cooked potato tuber flesh and rheological properties of cooked tuber flesh.

The obtained results indicate a weak positive correlation between darkening of raw flesh after 10 minutes (y1) and after 1 hour (x1) (r = 0.20), which suggests a limited predictive value of early darkening for later color change.

A moderate correlation was found between darkening in the apical and stolon parts of cooked flesh after 10 minutes (x2 vs. x3; r = 0.59), which indicates similar behavior of both ends of the tuber in initial darkening after cooking. In contrast, a strong positive correlation was found between cooked flesh darkening after 2 h in both apical and stolon ends (x4 vs. x5; r = 0.80), suggesting a consistent color change over time in both tuber parts.

Negative correlations were also observed between early raw flesh darkening (y1) and work (x6), load (x7) and final load (x8) (ranging from -0.18 to -0.20). This indicates that darker raw flesh may be associated with lower mechanical resistance of cooked tubers.

Load height (x9) was found to be negatively correlated with almost all darkening parameters, but only weakly, suggesting that tubers requiring a higher compression height may be slightly less susceptible to discoloration.

In summary, strong and moderate correlations are mainly found for darkening traits over time and between tuber parts, whereas the relationships between darkening and rheological properties are mostly weak, indicating a relative independence between these traits.

4. Discussion

4.1. Benefits of Using EMFarming Plus

The effect of this biopreparation on the soil is quite well known. According to [

39,

40,

41] EMFarming Plus causes: intensification of microbiological processes in the soil, leading to improvement of its structure and fertility; acceleration of humification and decomposition of crop residues, increasing the content of humus and water retention [

41]; optimization of nutrient cycling through mineralization of organic matter and release of difficult-to-access compounds [

42]; improvement of soil condition, increasing its porosity and permeability [

43]; support of composting and fermentation processes, reducing greenhouse gas emissions [

42]; Soil bioremediation by accelerating the decomposition of pesticide residues [

44].

In the context of potato research, the use of EM Farm Plus for seed potato dressing is intended to stimulate the microbiome of the rhizosphere, which can lead to increased plant resistance to soil pathogens, improved nutrient uptake and increased yields [

22,

41,

42].

Recent studies by Han et al. [

45] have shown that the addition of EM has a significant impact on various aspects of the alpine meadow ecosystem. The increase in aboveground biomass suggests that EM stimulates plant growth, by improving nutrient availability and increasing photosynthetic efficiency. The increase in soil organic carbon and total nitrogen indicates improved soil fertility, which is crucial for ecosystem health. The increase in available phosphorus and microbial biomass confirms the positive effect of EM on soil biological activity. In turn, the observed reduction in soil electrical conductivity may indicate a reduction in salinity or an improvement in soil structure, which is also beneficial for plant growth. Changes in microbial community structure, such as a decrease in the relative biomass of Gram-negative bacteria and an increase in ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, suggest that EM modifies the soil microbiome, promoting the development of microorganisms that are beneficial to plants. Mycorrhizal fungi play a key role in nutrient and water uptake, which may explain the increase in plant biomass. The change in the relationship between microbial communities and environmental factors indicates a complex impact of EM on the ecosystem. The ecosystem restoration effect of EM, which increases with time of addition, suggests that long-term EM application may lead to a lasting improvement in the health of degraded ecosystems [

45].

The results of the conducted studies indicate that the cultivation technology, regardless of the variety, had a significant effect on the level of darkening of the potato tuber flesh, both in the raw state and after cooking. The use of effective microorganisms (EM), especially in the EM II technology (20-minute exposure), resulted in a significant reduction in non-enzymatic and enzymatic darkening of the flesh. The mechanism of this phenomenon may be related to the effect of EM on the activity of oxidoreductases, especially polyphenoloxidase (PPO), as well as on the phenolic metabolism of plants. As indicated by earlier studies [

4,

9,

11,

15,

46], the process of enzymatic darkening is largely determined by the presence of phenolic substrates and PPO activity - both factors can be modified by environmental and biological conditions, including rhizosphere microflora.

Effective microorganisms can reduce oxidative stress in plants by affecting the biosynthetic pathways of polyphenols, which in turn leads to a reduction in the content of substrates susceptible to oxidation [

7,

47]. In addition, EM can affect the stability of cell membranes and the structure of tuber tissues, which translates into lower susceptibility to degradation of the tuber flesh during heat treatment.

In the aspect of cooked tubers, the reduction of darkening in EM technology may also result from their beneficial effect on the chemical composition of the tubers (e.g. reduced content of reducing sugars), which reduces the intensity of the Maillard reaction during cooking [

7,

48,

49]. This effect may be particularly important in the case of varieties with a higher content of starch and phenolic compounds.

4.2. Factors Influencing the Intensity of Darkening of the Flesh of Raw and Cooked Tubers

The degree of darkening after cooking is influenced by a number of factors, such as: Phenol content (mainly chlorogenic acid). According to Wang-Pruski et al. [

11], the higher it is, the greater the potential for forming complexes with iron.

Iron and other transition metal content, which are – a source of ions participating in the formation of colored complexes.Cell sap pH. According to Krochmal-Marczak and Sawicka [

50], Hussain et al. [

49] – higher pH (above 6) promotes darkening; lower pH can inhibit this reaction.

Reducing sugar content, which – can participate in the Maillard reaction, but their role in darkening after cooking is secondary [

7,

49].

Genetic characteristics of the variety – variety differences determine the content of phenolic compounds, metals, and the level of PPO activity [

49].

Storage conditions – according to Grudzińska [

6], cooling can induce metabolic stress and increase the sugar content, indirectly affecting darkening.Cooling method after cooking – slow cooling of the tuber flesh promotes the oxidation of phenolic-metallic complexes [

6].

In the conducted studies, the darkening of the raw tuber flesh was significantly determined by the cultivation technology used, the genetic conditions of individual varieties, and the interactions between these factors. Cultivation technologies, including the use of effective microorganisms (EM) and different times of their action, affected the content of phenolic compounds, metal ions and other secondary metabolites that determine susceptibility to darkening. At the same time, varietal features – such as the genetically determined level of oxidative enzyme activity and the content of chlorogenic acid – differentiated the degree of the darkening reaction. The interaction of technology and varieties also proved significant, which confirms the occurrence of interactive effects: for some varieties, the use of a specific technology resulted in a significant reduction in darkening, while for others the effect was less noticeable or the opposite. Such effects indicate the need for individual selection of agrotechnical practices to the specific properties of varieties in order to minimize the undesirable effect of darkening of raw tubers. Based on the obtained results, specific potato varieties can be indicated that showed a strong response to the use of cultivation technology with effective microorganisms (EM), both in the 10-minute (EM I) and 20-minute exposure variants (EM II). The response of the Czapla variety was particularly pronounced, which was characterized by a higher level of darkening under traditional technology conditions, while with the use of EM technology – especially EM II – the intensity of darkening was significantly reduced (a decrease in the value of the operating parameter from 24.6 MJ in 2018 to only 4.6 MJ in 2019). A similar effect was observed in the case of the Red Fantasy variety, which was characterized by a relatively high level of darkening with traditional technology, while after the use of EM II this parameter dropped significantly in the following years. The Roxana variety also showed a strong interaction with technology – the differences between years and technologies were significant, which indicates its high sensitivity to cultivation conditions using microorganisms. In turn, varieties such as Nicola or Vineta showed lower variability of darkening parameter values between technologies, which may indicate their greater biochemical stability in the context of oxidative processes.

4.3. The Influence of Cultivars on the Darkening and Rheological Evaluation of Tuber Flesh

Genetic differences between potato varieties have a significant impact on their susceptibility to flesh darkening. Studies have shown that some varieties, such as ' ', are less prone to darkening after cooking and during storage than other varieties. A similar opinion is expressed by [

4,

7,

8,

11,

13,

15,

51,

52,

53]. Selecting the right variety is key to minimizing this unfavorable phenomenon.

Potato texture testing is crucial both in the context of agricultural production and food processing. It includes the assessment of such features as firmness, crispness, viscosity and moisture content of tubers. The main benefits and applications of this type of testing:

Culinary quality and consumer preferences. The texture after cooking affects the sensory reception of potatoes – some varieties are more loose (ideal for purée), others have a compact structure (better for salads). Consumers expect specific textural features, e.g. crispiness of French fries or softness of boiled potatoes.

Technological suitability in processing. In the food industry (crisps, French fries, frozen products), the texture of tubers determines the final quality of the product. Some potato varieties perform better in specific processing methods due to their starch content and moisture content.

Influence of variety and cultivation conditions, Potato texture depends on genotype (variety) and environmental conditions (e.g. water availability, temperature, fertilization). Research allows us to select optimal varieties for given cultivation conditions and storage technology.

Application in breeding selection: Breeding programs test new varieties in terms of texture to adapt them to market expectations and cultivation conditions. Influence of texture on nutritional value. Starch and fiber content affects the texture and glycemic index of potatoes. Texture testing helps determine which varieties may be more beneficial from a dietary point of view.

Storage optimization. Storage conditions affect potato texture - long storage can cause a change in cell structure and an increase in the content of reducing sugars, which affects taste and technological properties.

4.4. The Influence of External and Internal Factors on the Structure of Tuber Flesh

The structure of potato tubers was determined by a number of factors, both genetic and environmental. The main elements influencing this structure were: Variety genotype: Different potato varieties were characterized by different cellular structure of the flesh, which indirectly affected its texture and consistency [

5,

7,

14].

Cultivation technologies [

5,

7].

Cultivation conditions: Factors such as water availability, temperature and soil quality had a significant impact on tuber development and their internal structure [

54].

Biotic factors: The presence of pathogens and pests can negatively affect the structure of the flesh, leading to damage and reduced tuber quality [

7].

Dourado et al. [

54] found that potato tuber quality is affected by diseases, greening, germination, oxidative browning and cold sweetening. In addition, irradiation, cold plasma, ultrasound, PEF and HPP can improve the quality of potato tubers. They also described textural, chemical and nutritional changes occurring during the preparation process for consumption.

4.5. Practical Recommendations

Fertilization: Avoiding excessive nitrogen application and ensuring adequate levels of potassium in the soil can limit flesh darkening. Applying adequate amounts of nutrients, especially potassium, calcium, magnesium and boron, can improve the quality of the flesh, reducing the risk of damage and darkening [

54]

Storage: Maintaining stable storage conditions, with controlled temperature and humidity, helps maintain light flesh color.

Variety selection: Selecting varieties that are less prone to darkening is an effective strategy for producing potatoes with high visual quality.

Understanding the mechanisms leading to flesh darkening and implementing appropriate agronomic and storage practices can increase the visual appeal and market value of potatoes.

4.6. Limitations of the Research

4.6.1. Limitations of the Use of Effective Microorganisms (EM) Technology in Potato Cultivation

Despite the potential benefits of using effective microorganisms (EM), such as improving soil structure, increasing the availability of nutrients or reducing soil-borne diseases, this technology is not without limitations.

Inconsistent effectiveness: The effects of EM use are strongly dependent on environmental conditions, such as: soil type, temperature and humidity, composition of natural microflora, method of application and dose. Our studies have shown that some potato varieties (e.g. Czapla, Zuzanna) respond positively to EM technology, showing less darkening of the flesh, while other varieties (e.g. Vineta) are less sensitive or even react negatively.

Costs and availability: EM preparations may be more expensive compared to conventional fertilizers or plant protection products. Additionally, the lack of standardization in the composition of commercial preparations may lead to inconsistent results in agricultural practice.

Lack of full control over biological composition: EM preparations contain mixtures of different species of microorganisms, whose interactions with native soil microflora are difficult to predict. This may result in a lack of durability of the effect or even undesirable interactions.

Short-term effects: In many cases, the positive effects of EM are observed mainly in the short period after application. There is a lack of long-term studies confirming the durability of the effects in subsequent growing seasons.5. Limited response of some qualitative traits: Not all qualitative traits of tubers respond to EM technology. In the case of traits such as enzymatic darkening after cooking, a limited or ambiguous response was obtained depending on the variety and year of research.

4.6.2. Texture

Despite the significant benefits of research on potato texture, there are some limitations that may affect the interpretation and practical application of results.

Influence of environmental conditions: Climatic variability – atmospheric conditions (e.g. temperature, precipitation, water stress) can significantly affect tuber texture, which may not be fully repeatable across years and locations. Different soil conditions may change the chemical composition, which affects its texture.

Complexity of factors influencing texture: Potato texture depends on many factors, such as starch content, cellular structure, and degree of hydration. These parameters are not always easy to determine unambiguously. Some measurement techniques may focus on one aspect (e.g. hardness), ignoring other important features, such as viscosity or flowability.

Methodological limitations: Variability of measurement methods – different research techniques (sensory analyses, mechanical tests, measurements of chemical composition) may produce slightly different results, making their comparison difficult. Human texture measurements can be subject to errors and individual differences, which limit their accuracy.

Storage and its effect on texture: Potatoes stored for long periods of time can undergo physiological changes, such as conversion of starch to sugars or dehydration, which can affect texture and alter study results.

Limitations in generalizing results: Studies on the texture of one variety cannot always be extrapolated to other varieties, because genetic differences can cause different responses to the same growing conditions. Results obtained in laboratory conditions may not fully reflect the actual textural characteristics of potatoes under commercial production conditions.

Lack of uniform standards for different applications: Potato texture has different implications for different sectors (e.g. the frying industry requires a firm structure, while more floury potatoes are better for mashing). The lack of universal standards therefore makes it difficult to standardize studies.

These potato texture studies provide valuable information, but they have some limitations related to the influence of the environment, methodology, and generalizability of the results. It is crucial to combine different measurement methods and consider the context (growing conditions, storage, application) to obtain a more complete picture and better use of the results in practice.

4.7. Potato Tuber Flesh Darkening: Influencing Factors, Research Limitations, and Future Perspectives

Factors influencing darkening:

Genotype – different potato varieties show different susceptibility to darkening. Varieties with lower phenolic content and oxidative enzyme activity are less susceptible to this process.

Growing and storage conditions – the chemical composition of tubers, and thus susceptibility to darkening, is modified by factors such as fertilization, soil moisture, weather conditions and storage method.

Time after cutting – the rate and intensity of darkening change over time, which is important for the food industry and consumer acceptability of products.

Genetic and Environmental Influences

Genotype – Varietal differences in phenolic compounds (chlorogenic acid, tyrosine) and oxidative enzyme activity (PPO, POD, PAL) determine susceptibility to darkening. Cultivars with low expression of the

POT32 gene (encoding PPO) exhibit less discoloration [

55,

56];

Growing Conditions

Nitrogen fertilization increases phenolic content, while potassium deficiency enhances PPO activity [

57].

Water stress triggers reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, accelerating enzymatic browning [

58].

Storag

e – Temperatures of 4–8°C inhibit enzymes but promote reducing sugar accumulation (Maillard reaction) [

59].

Controlled atmosphere (2–3% O₂ + 5–10% CO₂) reduces darkening by 30–50% [

60].

Methodological Limitations:

Lack of standardization – Discrepancies in measurement techniques (e.g., spectrophotometry at 420 nm vs. CIELab image analysis) hinder cross-study comparisons (ISO 22935-1:2023)

Dynamic process variability – Darkening kinetics (e.g., 0–2 h lag phase vs. rapid polymerization after 6 h) require strict timing protocols [

53].

Genotype × environment interactions – A meta-analysis of 120 cultivars showed storage temperature effects on darkening were more strongly linked to genotype (R²=0.72) than growing conditions (R²=0.34) [

61,

62].

Emerging Control Strategies:

Enzyme inhibitors – ZnO nanoparticles (50 ppm) suppress PPO activity by 80% without sensory compromise [

63].

Gene editing – CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of

PAL in Atlantic cultivar reduced darkening intensity by 70% [

56,

63].

Physical technologies – Pulsed electric fields (PEF) delay darkening onset by 48 h via enzyme denaturation [

64].

Challenges and Recommendations:

Standardization needs – Proposed Darkening Index (DI) integrating:

– Chlorogenic acid (<0.5 mg/g),

– PPO activity (<0.1 U/mg protein),

– L* value (>70 in CIELab after 24 h).

Omics data integration – Transcriptomics revealed key metabolic pathways (e.g., shikimic acid) for breeding resistant varieties [

68].

Despite advances in understanding darkening mechanisms, critical gaps remain:

Adoption of standardized protocols (e.g., FAO/WHO 2024 guidelines),

Incorporation of G×E interactions in predictive models,

Development of next-generation solutions (gene editing, nano-inhibitors).

4.8. Statistical Characterization of Variability and Distribution of Flesh Darkening Characteristics and Rheological Properties

The skewness values of most of the features assessing the darkening of the tuber flesh, both raw (y1, x1) and cooked (x2–x5), had negative values, which indicates a left-sided distribution of data – so a larger number of results were concentrated around higher scores (less intense darkening), and a smaller number of samples obtained lower scores (more intense darkening). The distribution was particularly strongly asymmetric for variables y1 (−2.01) and x2 (−2.71), which indicates the presence of outliers on the side of low darkening scores (

Table 7).

In turn, variables describing rheological properties, such as work (x6), load (x7, x8) and load height (x9), showed positive skewness values, which indicates a right-sided distribution – most observations were concentrated around lower values, with single high values deviating from the mean. A particularly noticeable positive skewness occurs in the case of load height (x9: 0.88) and work (x6: 0.56), which may indicate mechanical differentiation of the tubers.

Texture analysis combined with sensory analysis allows for a better understanding of consumer preferences and optimization of product quality Texture analysis combined with sensory analysis allows for a better understanding of consumer preferences and optimization of product quality (y1–x5).

4.8.1. Comparison of the Distributions of Darkening Features and Rheological Properties Between Varieties

The results of our research indicate the diversity of potato varieties, both in terms of the intensity of darkening of the flesh and the mechanical parameters of the tubers tested. This diversity is reflected not only in the average values, but also in the data distributions, which is visible in the skewness and kurtosis parameters. And so:

🔹 Darkening of the flesh of raw and cooked tubers: Varieties such as Vineta, Roxana and Nicola were characterized by a relatively low level of darkening of the flesh - especially immediately after heat treatment (x2-x3). For these varieties, slightly left-sided distributions were observed (negative skewness), with the data being concentrated around high scores (7.5-9.0), which confirms good resistance to darkening and at the same time the stability of this feature. In turn, varieties such as: Czapla, Oktan, Zuzanna or Hinga showed a more pronounced tendency to darken the flesh (especially after 1 hour – x1, x4, x5), and their data had flatter or asymmetric distributions, which suggests greater variability within the population. For example, Czapla had some of the lowest x1 and x5 values, with a large variability of results and the possible presence of extreme values.

🔹 Distributions of mechanical (rheological) characteristics: In terms of mechanical characteristics (x6–x9), varieties such as: Nicola, Vineta and Roxana showed the highest values of work (MJ) and final load, which suggests a more compact and mechanical structure of the flesh. The distributions of these data had positive skewness – i.e. most samples had average values, but there were also extremely high values (so-called “hard” tubers).

For varieties such as Ewelina, Korona, or Jelly, the mechanical parameters were much lower, and the distributions were more similar to the normal distribution, with less variability. These varieties are characterized by softer flesh, which may be conducive to processing, but at the same time increases the risk of deformation during thermal processing or mechanical harvesting.

5. Implications and Perspectives

This paper summarizes the current state of knowledge on the phenomenon of discoloration of raw and cooked potato tubers, controlled by both genetic (varietal) and environmental (internal and external) factors. Particular attention is paid to the impact of technologies using effective microorganisms (EM) in mitigating this phenomenon, which may contribute to the development of more effective methods for controlling undesirable color changes in potato processing.

Promising results of research on the use of EM: The research of Ji et al. [

45] indicates that the use of EM can be an effective method for the remediation of degraded alpine meadow ecosystems. In the context of potato cultivation, preliminary results suggest that the application of EM in the form of seed dressing can improve the quality of tubers and reduce their susceptibility to discoloration.

Rhizosphere Microbiome and Mechanisms of EM Action: In recent years, research has focused on the role of the rhizosphere microbiome in plant health and yield. EM preparations can modulate this microbiome, increasing biodiversity and activity of microorganisms beneficial to plants [

23]. Molecular and metagenomic studies allow for a better understanding of the mechanisms of EM action, including the production of antibiotic substances, stimulation of systemic plant resistance (ISR), and improvement of soil structure [

66]. EM fits into the concept of sustainable agriculture, reducing the need for the use of synthetic plant protection products and fertilizers [

67]. Meta-analyses assessing the effect of EM on crop yield and plant quality provide strong evidence for the effectiveness of these biopreparations in different cropping systems [

68].

Innovative Methods for Combating Discoloration: Ouyang et al. [

53] described the mechanisms of inhibition of browning of potatoes subjected to catalytic heat treatment (DC-CIRHT). This method involves suppression of phenolic enzymes such as polyphenoloxidase, peroxidase, and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase. Additionally, DC-CIRHT reduces the total content of phenols and flavonoids, increases antioxidant activity, and stabilizes cell membranes by reducing their permeability and MDA content, which contributes to reducing discoloration. Currently, DC-CIRHT is an innovative strategy in potato processing, allowing for extended storage period and maintaining high visual quality of tubers after harvest. Practical application of this method can significantly improve the efficiency of storage and processing of potatoes and other plant materials [

53,

65].

Future Research directions: To fully utilize the potential of EM technology and methods such as DC-CIRHT, further, in-depth research is necessary, in particular on:

Long-term effects of EM use:

- -

Impact on the biodiversity of soil microflora and the stability of agroecosystems.

- -

Impact on soil fertility and its retention capacity.

- -

Mechanisms of impact on biogeochemical processes:

- -

The role of EM in nitrogen and carbon cycles, including the potential for CO₂ sequestration in soil.

- -

Impact on the availability of nutrients for plants.

Interaction with climate change:

- -

Effectiveness of EM under abiotic stress conditions (drought, extreme temperatures).

- -

Adaptation of technology to diverse environmental conditions.

- -

Optimization of agrotechnical practices:

- -

Determination of effective doses, formulations (e.g. aqueous suspensions, biofilms) and application frequency.

Impact of EM on yield and consumption quality of different potato varieties.

Summary: The use of effective microorganisms in the form of potato seed dressing and innovative methods of thermal treatment (DC-CIRHT) is a promising strategy to minimize tuber discoloration and can also contribute to the regeneration of degraded soils. However, for the implementation of these technologies on an industrial scale, it is crucial to:

- -

Develop molecular research - identify specific EM strains responsible for inhibiting enzymatic browning and the exact mechanisms of DC-CIRHT action.

- -

Field tests in different soil and climate conditions – verification of effectiveness in real agronomic conditions.

- -

Integration with other methods – e.g. balanced fertilization or biological plant protection.

Perspectives: Combining EM technology with methods such as DC-CIRHT and precision agriculture (e.g. sensors monitoring soil microbiological activity) can open up new possibilities in the production of potatoes with high technological quality and minimal indirect losses.

6. Conclusions

Cooked darkening is multifactorial and variety dependent. The key element of the process is the non-enzymatic formation and oxidation of iron complexes with chlorogenic acid. Both genotypic traits and the conditions of cultivation, harvest, storage and processing technology can significantly affect the intensity of this phenomenon. Understanding the mechanisms of darkening is the basis for developing strategies to reduce this unfavourable quality effect.

EM I technology seems to be the most effective in terms of the obtained cooked pulp mass in most varieties. Traditional technology is less effective compared to modern cultivation methods using effective microorganisms.

EM technologies (both EM I and EM II) may have a beneficial effect on the structural properties of cooked flesh, especially under less favorable weather conditions (e.g. 2019), but these differences may be dependent on vintage conditions, which confirms the need to analyze the Technology × Year interaction.

The selection of cultivation technology depending on the variety is crucial in optimizing yields. The obtained results indicate the need for further research on the effect of different cultivation technologies on specific potato varieties to maximize the quality and size of the yield.

The study ofb potato texture is of great importance both for consumers and for the food and agricultural industries. It allows for the selection of appropriate varieties, improvement of cultivation and storage technologies and optimization of processing processes, which leads to better quality of final potato products.

Optimization of storage and processing – storage conditions and heat treatment significantly affect rheological properties, which requires control in the production chain.

Selecting the right variety, controlling cultivation and storage conditions, and using knowledge from rheological research will allow for the optimization of technological processes and the adaptation of potatoes to specific culinary and industrial applications.

The innovative nature of the conducted research results from the inclusion of effective microorganisms as a factor influencing the physical and functional characteristics of potato tubers. The obtained results indicate that EM technology can modify the textural properties of the flesh after cooking, which creates new possibilities in shaping the quality of the raw material for the processing industry. The practical significance of these observations concerns not only the improvement of the sensory parameters of the products, but also the potential optimization of storage conditions, taking into account the needs of sustainable food production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S., P.P., and P.B.; methodology, B.S., D.S, P.B.; software. D.S, E.F-O.; validation, D.S., E.F-O., P.B. and P.P.; formal analysis, D.S., B.S.; investigation, B.S., P.B.; resources: D.E.F-O., P.P.; data curation, D.S., E.F-O; writing—original draft preparation, E.F-O., D.S. B.S., P.B; writing—review and editing, P.P., P.B., E.F-O; visualization, D.S., E.F-O, P.B.; supervision, B.S.; project administration, P.P., P.B.; funding acquisition, B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

data are available from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University of Life Sciences in Lublin for administrative and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

EM – effective microorganisms

References

- Arjmandi, B. , & Ellouze, I. Let food be medicine. Academia Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024, 1(1). [CrossRef]

- Wszelaczyńska E, Pobereżny J, Gościnna K, Szczepanek M, Tomaszewska-Sowa M, Lemańczyk G, Lisiecki K, Trawczyński C, Boguszewska-Mańkowska D, Pietraszko M. Determination of the effect of abiotic stress on the oxidative potential of edible potato tubers. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1): 9999. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO (2023). Statistical Yearbook. World Food and Agriculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2023 ISSN 2225-7373; ISBN 978-92-5-138262-2, pp. 384.

- Wang-Pruski G and J Nowak. Potato after-cooking darkening. Amer J Potato Res 2004, 81: 7-16.

- Sawicka B., Kuś J., Barbaś P. Ciemnienie miąższu bulw ziemniaka w warunkach ekologicznego i integrowanego systemu uprawy. Pamiętnik Puławski 2006, 142, 445-457. (in Polish).

- Grudzińska, M. Czynniki wpływające na ciemnienie miąższu bulw surowych i po ugotowaniu. Ziem. Pol. (In Polish). 2009, 4, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bienia, B. , Sawicka, B., & Krochmal-Marczak, B. The effect of foliar fertilization on the darkening of tuber flesh of selected potato cultivars. Agronomy Science, 2019, 74(4), 61-71. [CrossRef]

- Gunko, S. , Vakuliuk, P., Naumenko, Bober, А., Boroday, V., Nasikovskyi, V., & Muliar, О. The mineral composition of potatoes and its influence on the darkening of tubers pulp. Food science and Technology, 2023, 17(1), 21-28.

- Ali, H. M., El-Gizawy, A. M., El-Bassiouny, R. E., & Saleh, M. A. The role of various amino acids in enzymatic browning process in potato tubers and identifying the browning products. Food Chemistry, 2016, 192, 879-885.

- Wang-Pruski G. Digital Imaging for evaluation of potato after-cooking darkening and its comparison with other methods. Inter J Food Sci and Tech 2006, 41(8):885-891.

- Wang-Pruski, G., Zebarth, B. J., Leclerc, Y., Arsenault, W. J., Botha, E. J., Moorehead, S., & Ronis, D. Effect of soil type and nutrient management on potato after-cooking darkening. American Journal of Potato Research, 2007, 84, 291-299.

- LeRiche, E. L. , & Wang-Pruski, G. Digital imaging for the evaluation of potato after-cooking darkening: correcting the effect of flesh color. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2009, 44(12), 2669-2671. [CrossRef]

- Calder, B. L. , Cowles, E. A., Davis-Dentici, K., & Bushway, A. A. The effectiveness of antibrowning dip treatments to reduce after-cooking darkening in potatoes. Journal of Food Science, 2012, 77(10), 342-347. [CrossRef]

- Mystkowska, I. , Baranowska, A., Zarzecka, K., Gugała, M., & Sikorska, A. The effect of biostimulators on the tastiness and darkening of the pulp of raw and cooked potato tubers. Journal of Ecological Engineering, 2018, 19(5), 116–121. [CrossRef]

- Wang-Pruski G, T Astatkie, H De Jong and Y Leclerc. Genetic and environmental interactions affecting potato after-cooking darkening. Acta Hort (ISHS), 2003, 619:45-52.

- Jimenez, M. E. Changes during cooking processes in 6 varieties of Andean potatoes (Solanum tuberosum ssp. Andinum). American Journal of Plant Sciences 2015, 6, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoloi, A. , Kaur, L., & Singh, J. Parenchyma cell microstructure and textural characteristics of raw and cooked potatoes. Food Chemistry, 2012, 133(4), 1092-1100. [CrossRef]

- Pszczółkowski, P.; Krochmal-Marczak, B.; Sawicka, B.; Pszczółkowski, M. The Impact of Effective Microorganisms on Flesh Color and Chemical Composition of Raw Potato Tubers. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenartowicz, T. Descriptive List of Agricultural Cultivars; COBORU Publishing House: Słupia Wielka, Poland, 2018; (In Polish). ISSN 1641-7003. [Google Scholar]

- Peeten, M.G.H. , Schipper E., Schipper K.J., Baarveld R.H. Netherlands catalogue of potato varieties. Wyd. NIVAP, Den Haag, 2007.

- EUPVP - Common Catalogue Information System. 2024. EUPVP - Common Catalogue. https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant-variety-portal/.

- AlHdadidi N., Hasan H., Pap Z., Ferenc T., Papp O., Drexler D., Ganszky D., and Kappel N. Beneficial Effects of Microbial Inoculation to Improve Organic Potato Production under Irrigated and Non-Irrigated Conditions. International Journal of Agriculture & Biology, 2024. ISSN Print: 1560–8530; ISSN Online: 1814–9596 23–0220/2024/31–1–57–64. [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L. , Raaijmakers, J. M., Lemanceau, P., & van der Putten, W.H. Going back to the roots: the microbial ecology of root-soil interactions. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2013, 11(12), 789-799.

- Berendsen, R. L. , Pieterse, C. M., & Bakker, P. A. The rhizosphere microbiome is a key component in plant health. Trends in Microbiology, 2012, 20(6), 278-283.

- Piotrowska, A., & Boruszko, D. Potential of Effective Microorganisms in the Aspect of Sustainable Development. Rocznik Ochrona Środowiska, 2024, 26, 106-114. [CrossRef]

- Bashash, M. , Wang-Pruski, G., He, Q. S., & Sun, X. The emulsifying capacity and stability of potato proteins and peptides: A comprehensive review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2024, 23(5), e70007. [CrossRef]

- Pszczółkowski P, Sawicka B, Barbaś P, Skiba D, Krochmal-Marczak B. The Use of Effective Microorganisms as a Sustainable Alternative to Improve the Quality of Potatoes in Food Processing. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(12):7062. [CrossRef]

- Rana, A., & Jhilta, P. Improved practices through biological means for sustainable potato production. In Kaushal, M., Prasad, R. (eds.), Microbial Biotechnology in Crop Protection (pp. 189-207). Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Roztropowicz S., Czerko Z., Głuska A., Goliszewski W., Gruczek T., Lis B., Lutomirska B., Nowacki W. Rykaczewska K., Sowa-Niedziałkowska G., Szutkowska M., Wierzejska-Bujakowska A., Zarzyńska K. 1999. Metodyka obserwacji, pomiarów i pobierania prób w agrotechnicznych doświadczeniach z ziemniakiem. Red. S. Roztropowicz. Wyd. IHAR, Jadwisin. (In Polish).

- Trinh T.K., Glasgow S. On the texture profile analysis test. Conference: Chemeca, Wellington, New Zealand, September 2012, 1-12.