Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

12 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Regulatory Framework, Chemical Classes & Regulations

2.1. General Food Law

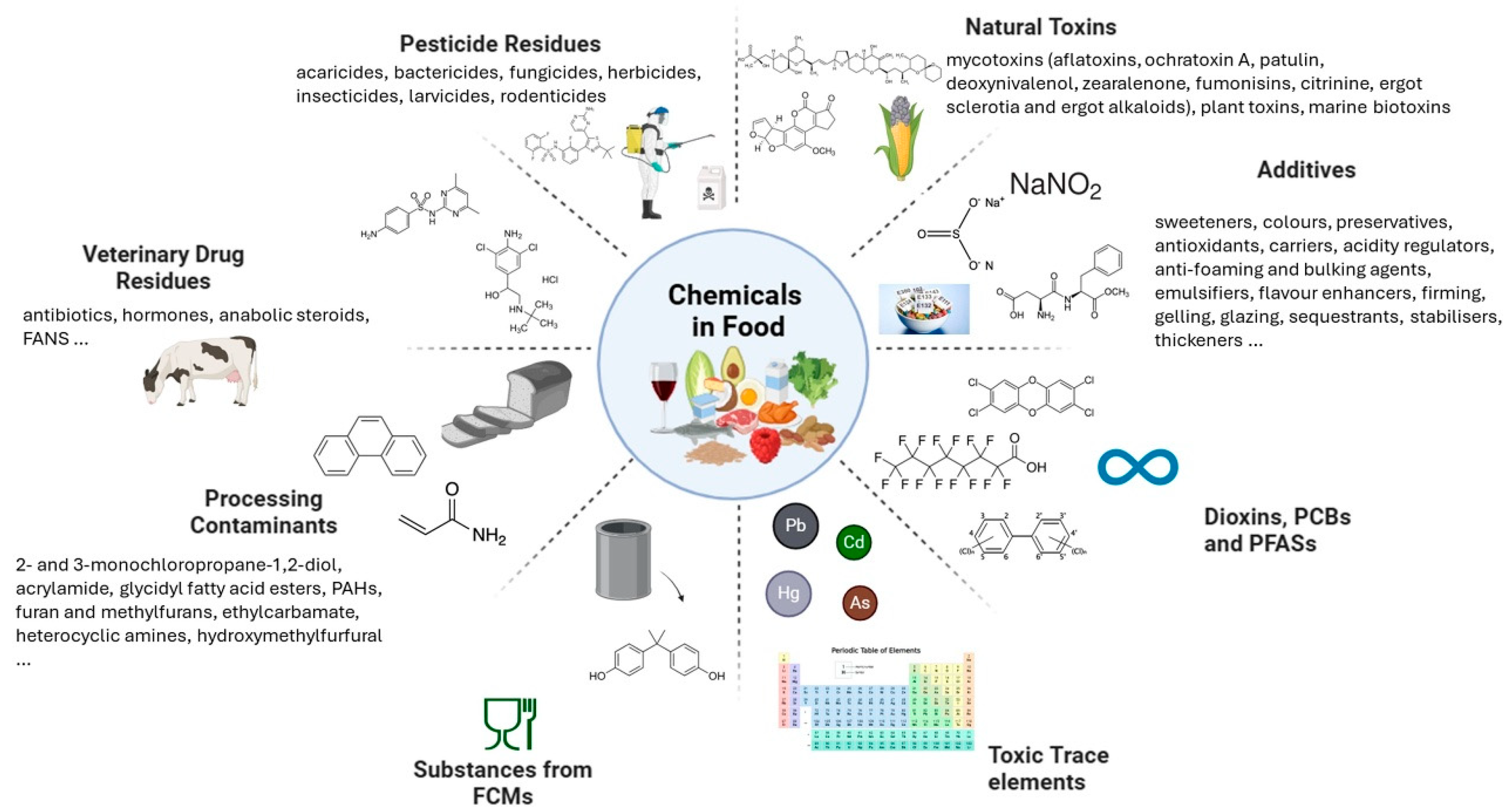

2.2. Chemicals in Food

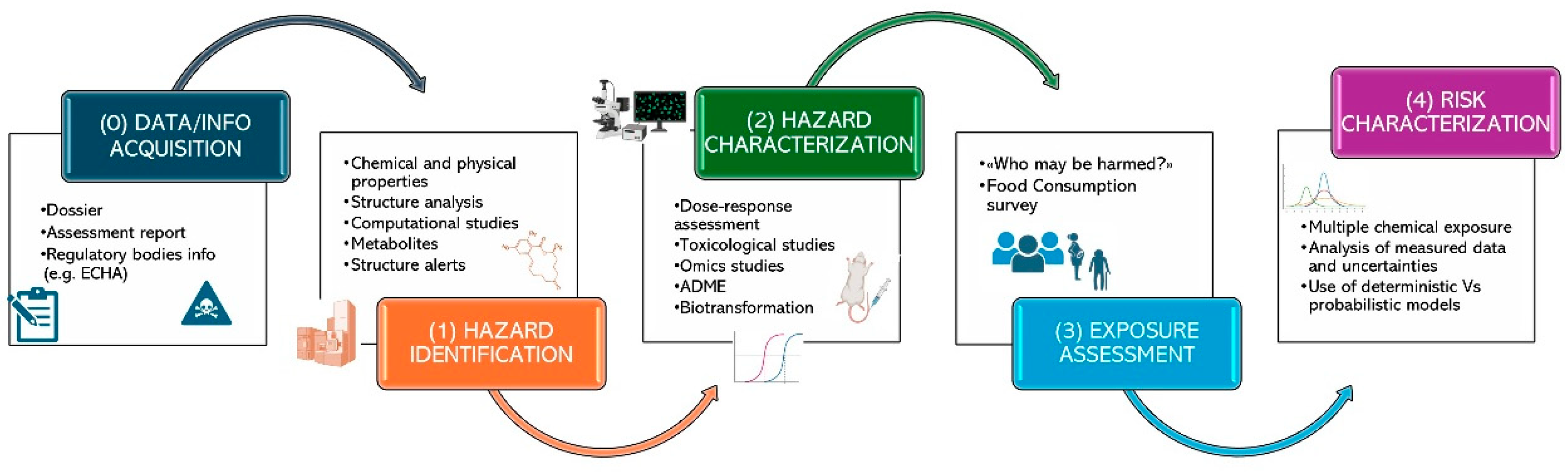

3. Risk Assessment of Chemicals in Food

- -

- Reducing or replacing animal testing by using in vitro, in silico, and in chemico models.

- -

- Identifying, evaluating, and minimizing uncertainties in exposure assessments.

- -

- Filling knowledge gaps, particularly in mechanistic toxicology and exposure modeling.

- -

- Assessing the effects of exposure to chemical mixtures, including multiple chemicals and other stressors.

3.1. Cumulative Risk Assessment of Chemicals in Food

4. Actors of Chemical Food Safety and Role of Analytical Controls and Monitoring Studies

4.1. Analytical Controls and Monitoring Studies in Chemical Food Safety

- -

- Regulation (EU) No. 333/2007: Establishes criteria for the detection of heavy metals in foodstuffs [105].

- -

- Regulation (EU) No. 2017/625: Provides a framework for food safety controls [34].

- -

- Regulation (EU) No. 2019/627: Defines procedures for official laboratory testing [81].

- -

- Decision 2002/657/EC: Specifies criteria for the validation of analytical methods for veterinary drug residue detection [13].

- -

- Regulation (EU) No. 2021/808: Updates method performance criteria for residue analysis.

5. New Challenges in Chemical Food Safety

5.1. Emerging Contaminants

5.1.1. PFAS

5.1.2. Microplastics and Nanoplastics

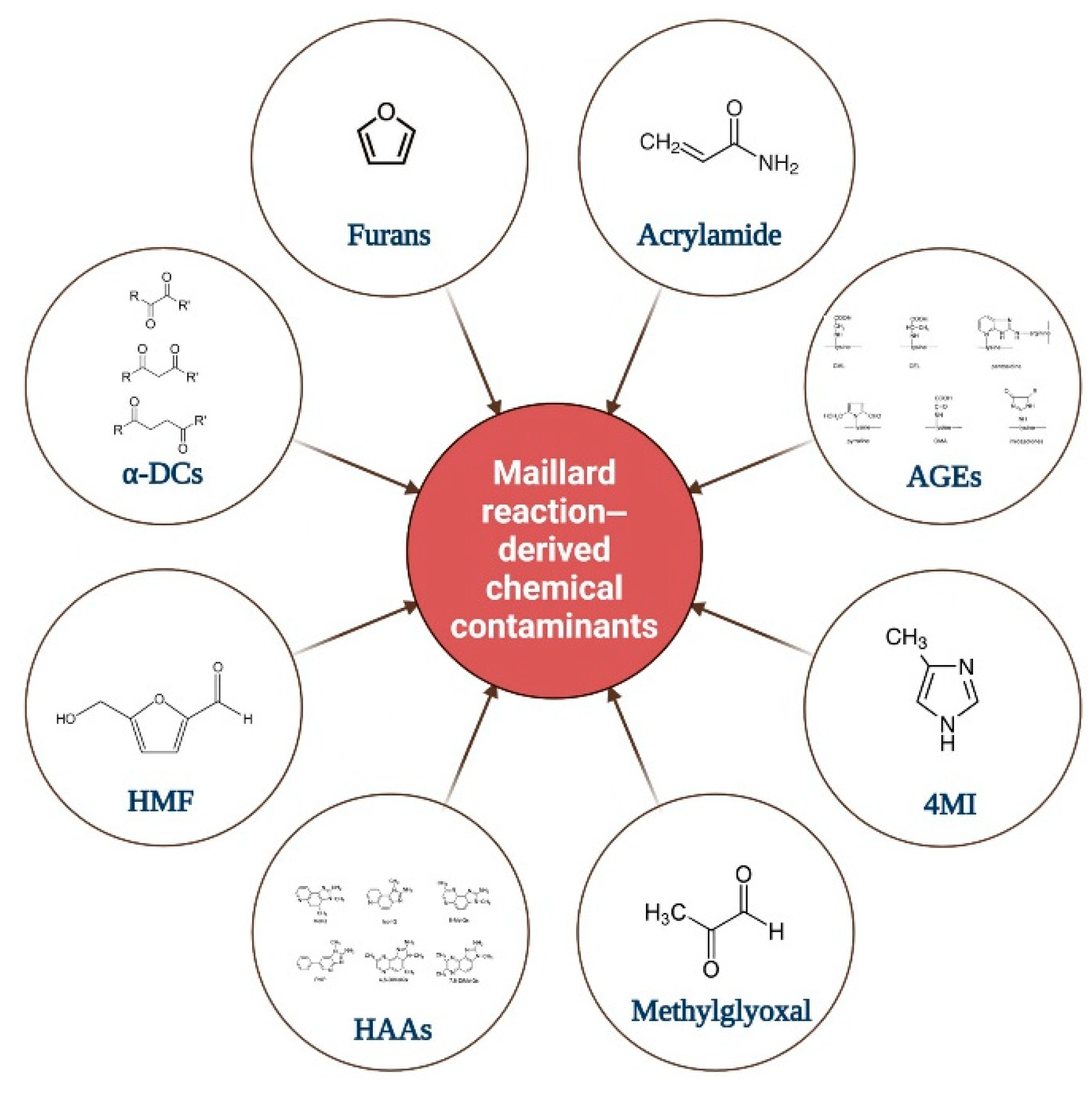

5.1.3. Novel Maillard Reaction‒Derived Chemical Contaminants

5.2. Artificial Intelligence

5.3. Multi-Source Data Fusion

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fung, F.; Wang, H.-S.; Menon, S. Food Safety in the 21st Century. Biomedical Journal 2018, 41, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2018.03.003.

- Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Rietjens, I.M.; Zheng, L. Current and Emerging Issues in Chemical Food Safety. Current Opinion in Food Science 2025, 62, 101284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2025.101284.

- Food Safety - EUR-Lex Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=legissum:food_safety (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- European Commission Farm to Fork Strategy - For a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System 2020.

- Food: From Farm to Fork Statistics Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-pocketbooks/-/ks-30-08-339 (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Smaoui, S.; Agriopoulou, S.; D’Amore, T.; Tavares, L.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. The Control of Fusarium Growth and Decontamination of Produced Mycotoxins by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2023, 63, 11125–11152. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2087594.

- European Commission Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 Laying down the General Principles and Requirements of Food Law, Establishing the European Food Safety Authority and Laying down Procedures in Matters of Food Safety; 2002; Vol. 031;

- D’Amore, T.; Taranto, A.D.; Berardi, G.; Vita, V.; Iammarino, M. Nitrate as Food Additives: Reactivity, Occurrence, and Regulation. In Nitrate Handbook; CRC Press, 2022 ISBN 978-0-429-32680-6.

- Types of Legislation | European Union Available online: https://european-union.europa.eu/institutions-law-budget/law/types-legislation_en (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- European Commission January 28 2002,.

- European Commission Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on Food Additives; 2008; Vol. 354;.

- European Commission Directive 2009/128/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 Establishing a Framework for Community Action to Achieve the Sustainable Use of Pesticides; 2009;

- European Commission Commission Decision of 14 August 2002 Implementing Council Directive 96/23/EC Concerning the Performance of Analytical Methods and the Interpretation of Results (Notified under Document Number C(2002) 3044) (Text with EEA Relevance) (2002/657/EC)Text with EEA Relevance; 2002;

- European Commission Commission Recommendation (EU) 2017/84 of 16 January 2017 on the Monitoring of Mineral Oil Hydrocarbons in Food and in Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food; 2017;

- European Commission Commission Recommendation (EU) 2018/464 of 19 March 2018 on the Monitoring of Metals and Iodine in Seaweed, Halophytes and Products Based on Seaweed; 2018;

- European Economic and Social Committee Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on ‘Towards a Fair Food Supply Chain’ (Exploratory Opinion); 2021;

- European Commission REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL on Food and Food Ingredients Treated with Ionising Radiation for the Years 2020-2021; 2023;

- Gokani, N. Healthier Food Choices: From Consumer Information to Consumer Empowerment in EU Law. J Consum Policy 2024, 47, 271–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-024-09563-0.

- Gensch, L.; Jantke, K.; Rasche, L.; Schneider, U.A. Pesticide Risk Assessment in European Agriculture: Distribution Patterns, Ban-Substitution Effects and Regulatory Implications. Environmental Pollution 2024, 348, 123836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.123836.

- Boobis, A.R.; Ossendorp, B.C.; Banasiak, U.; Hamey, P.Y.; Sebestyen, I.; Moretto, A. Cumulative Risk Assessment of Pesticide Residues in Food. Toxicol Lett 2008, 180, 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.06.004.

- Carvalho, F.P. Pesticides, Environment, and Food Safety. Food and Energy Security 2017, 6, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.108.

- Geueke, B.; Groh, K.; Muncke, J. Food Packaging in the Circular Economy: Overview of Chemical Safety Aspects for Commonly Used Materials. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 193, 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.005.

- Lebelo, K.; Malebo, N.; Mochane, M.J.; Masinde, M. Chemical Contamination Pathways and the Food Safety Implications along the Various Stages of Food Production: A Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 5795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115795.

- Jin, J.; Besten, H.M.W. den; Rietjens, I.M.C.M.; Widjaja, F. Chemical and Microbiological Hazards Arising from New Plant-Based Foods, Including Precision Fermentation–Produced Food Ingredients. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-food-111523-122059.

- Balkan, T.; Yılmaz, Ö. Method Validation, Residue and Risk Assessment of 260 Pesticides in Some Leafy Vegetables Using Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Food Chemistry 2022, 384, 132516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132516.

- MacLachlan, D.J.; Hamilton, D. Estimation Methods for Maximum Residue Limits for Pesticides. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2010, 58, 208–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.05.012.

- Hyder, K.; Travis ,Kim Z.; Welsh ,Zoe K.; and Pate, I. Maximum Residue Levels: Fact or Fiction? Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal 2003, 9, 721–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/713609964.

- Maxim, L.; Mazzocchi, M.; Van den Broucke, S.; Zollo, F.; Robinson, T.; Rogers, C.; Vrbos, D.; Zamariola, G.; Smith, A. Technical Assistance in the Field of Risk Communication. EFSA J 2021, 19, e06574. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6574.

- Coja, T.; Steinwider, J. The New European Transparency Regulation: A Panacea for EU Risk Assessment? J Consum Prot Food Saf 2022, 17, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00003-022-01364-2.

- Attrey, D.P. Chapter 5 - Role of Risk Analysis and Risk Communication in Food Safety Management. In Food Safety in the 21st Century; Gupta, R.K., Dudeja, Singh Minhas, Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2017; pp. 53–68 ISBN 978-0-12-801773-9.

- European Commission Regulation (EU) 2019/1381 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on the Transparency and Sustainability of the EU Risk Assessment in the Food Chain and Amending Regulations (EC) No 178/2002, (EC) No 1829/2003, (EC) No 1831/2003, (EC) No 2065/2003, (EC) No 1935/2004, (EC) No 1331/2008, (EC) No 1107/2009, (EU) 2015/2283 and Directive 2001/18/EC; 2019;

- Morvillo, M. Glyphosate Effect: Has the Glyphosate Controversy Affected the EU’s Regulatory Epistemology? European Journal of Risk Regulation 2020, 11, 422–435. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.11.

- Eissa, F.; Sebaei, A.S.; El Badry Mohamed, M. Food Additives and Flavourings: Analysis of EU RASFF Notifications from 2000 to 2022. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2024, 130, 106137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2024.106137.

- European Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on Official Controls and Other Official Activities Performed to Ensure the Application of Food and Feed Law, Rules on Animal Health and Welfare, Plant Health and Plant Protection Products, Amending Regulations (EC) No 999/2001, (EC) No 396/2005, (EC) No 1069/2009, (EC) No 1107/2009, (EU) No 1151/2012, (EU) No 652/2014, (EU) 2016/429 and (EU) 2016/2031 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Council Regulations (EC) No 1/2005 and (EC) No 1099/2009 and Council Directives 98/58/EC, 1999/74/EC, 2007/43/EC, 2008/119/EC and 2008/120/EC, and Repealing Regulations (EC) No 854/2004 and (EC) No 882/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Council Directives 89/608/EEC, 89/662/EEC, 90/425/EEC, 91/496/EEC, 96/23/EC, 96/93/EC and 97/78/EC and Council Decision 92/438/EEC (Official Controls Regulation); 2017;

- WHO, FAO Principles and Methods for the Risk Assessment of Chemicals in Food - International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS); Marla Sheffer: Ottawa, Canada; Vol. Environmental health criteria; 240; ISBN 978 92 4 157240 8.

- Gürtler, R. Risk Assessment of Food Additives. In Regulatory Toxicology; Reichl, F.-X., Schwenk, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 1323–1337 ISBN 978-3-030-57499-4.

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS); Mortensen, A.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Di Domenico, A.; Dusemund, B.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; et al. Re-Evaluation of Glutamic Acid (E 620), Sodium Glutamate (E 621), Potassium Glutamate (E 622), Calcium Glutamate (E 623), Ammonium Glutamate (E 624) and Magnesium Glutamate (E 625) as Food Additives. EFSA Journal 2017, 15, e04910. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4910.

- D’Amore, T.; Di Taranto, A.; Berardi, G.; Vita, V.; Marchesani, G.; Chiaravalle, A.E.; Iammarino, M. Sulfites in Meat: Occurrence, Activity, Toxicity, Regulation, and Detection. A Comprehensive Review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2020, 19, 2701–2720. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12607.

- D’Amore, T.; Di Taranto, A.; Berardi, G.; Vita, V.; Iammarino, M. Going Green in Food Analysis: A Rapid and Accurate Method for the Determination of Sorbic Acid and Benzoic Acid in Foods by Capillary Ion Chromatography with Conductivity Detection. LWT 2021, 141, 110841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110841.

- European Commission Regulation (EC) No 1334/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on Flavourings and Certain Food Ingredients with Flavouring Properties for Use in and on Foods and Amending Council Regulation (EEC) No 1601/91, Regulations (EC) No 2232/96 and (EC) No 110/2008 and Directive 2000/13/EC (Text with EEA Relevance); 2008; Vol. 354;.

- European Commission Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 February 2005 on Maximum Residue Levels of Pesticides in or on Food and Feed of Plant and Animal Origin and Amending Council Directive 91/414/EEC; 2005;

- EFSA; Carrasco Cabrera, L.; Di Piazza, G.; Dujardin, B.; Marchese, E.; Medina Pastor, P. The 2022 European Union Report on Pesticide Residues in Food. EFSA Journal 2024, 22, e8753. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2024.8753.

- European Commission Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2024/989 of 2 April 2024 Concerning a Coordinated Multiannual Control Programme of the Union for 2025, 2026 and 2027 to Ensure Compliance with Maximum Residue Levels of Pesticides and to Assess the Consumer Exposure to Pesticide Residues in and on Food of Plant and Animal Origin and Repealing Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/731; 2024;

- EU Multi-Annual Control Programmes - European Commission Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/maximum-residue-levels/enforcement/eu-multi-annual-control-programmes_en (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- European Commission Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market and Repealing Council Directives 79/117/EEC and 91/414/EEC; 2009;

- Carisio, L.; Simon Delso, N.; Tosi, S. Beyond the Urgency: Pesticide Emergency Authorisations’ Exposure, Toxicity, and Risk for Humans, Bees, and the Environment. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 947, 174217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174217.

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) No 37/2010 of 22 December 2009 on Pharmacologically Active Substances and Their Classification Regarding Maximum Residue Limits in Foodstuffs of Animal Origin (Text with EEA Relevance)Text with EEA Relevance; 2010;

- European Commission Regulation (EC) No 470/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 May 2009 Laying down Community Procedures for the Establishment of Residue Limits of Pharmacologically Active Substances in Foodstuffs of Animal Origin, Repealing Council Regulation (EEC) No 2377/90 and Amending Directive 2001/82/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council; 2009;

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) No 10/2011 of 14 January 2011 on Plastic Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food (Text with EEA Relevance); 2011;

- European Commission Regulation (EC) No 1935/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 October 2004 on Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food and Repealing Directives 80/590/EEC and 89/109/EEC; 2004;

- Neri, I.; Russo, G.; Grumetto, L. Bisphenol A and Its Analogues: From Their Occurrence in Foodstuffs Marketed in Europe to Improved Monitoring Strategies—a Review of Published Literature from 2018 to 2023. Arch Toxicol 2024, 98, 2441–2461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-024-03793-4.

- EFSA Panel on food contact materials, enzymes, flavourings and processing aids (CEF) Scientific Opinion on Bisphenol A: Evaluation of a Study Investigating Its Neurodevelopmental Toxicity, Review of Recent Scientific Literature on Its Toxicity and Advice on the Danish Risk Assessment of Bisphenol A. EFSA Journal 2010, 8, 1829. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1829.

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) 2024/3190 of 19 December 2024 on the Use of Bisphenol A (BPA) and Other Bisphenols and Bisphenol Derivatives with Harmonised Classification for Specific Hazardous Properties in Certain Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food, Amending Regulation (EU) No 10/2011 and Repealing Regulation (EU) 2018/213; 2024;

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Food and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 (Text with EEA Relevance); 2023;

- Crebelli, R. Towards a Harmonized Approach for Risk Assessment of Genotoxic Carcinogens in the European Union. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2006, 42, 127–131.

- EFSA Opinion of the Scientific Committee on a Request from EFSA Related to A Harmonised Approach for Risk Assessment of Substances Which Are Both Genotoxic and Carcinogenic. EFSA Journal 2005, 3, 282. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2005.282.

- Smaoui, S.; D’Amore, T.; Agriopoulou, S.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Mycotoxins in Seafood: Occurrence, Recent Development of Analytical Techniques and Future Challenges. Separations 2023, 10, 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10030217.

- Smaoui, S.; D’Amore, T.; Tarapoulouzi, M.; Agriopoulou, S.; Varzakas, T. Aflatoxins Contamination in Feed Commodities: From Occurrence and Toxicity to Recent Advances in Analytical Methods and Detoxification. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2614. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11102614.

- Cendoya, E.; Chiotta, M.L.; Zachetti, V.; Chulze, S.N.; Ramirez, M.L. Fumonisins and Fumonisin-Producing Fusarium Occurrence in Wheat and Wheat by Products: A Review. Journal of Cereal Science 2018, 80, 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2018.02.010.

- Goessens, T.; Mouchtaris-Michailidis, T.; Tesfamariam, K.; Truong, N.N.; Vertriest, F.; Bader, Y.; De Saeger, S.; Lachat, C.; De Boevre, M. Dietary Mycotoxin Exposure and Human Health Risks: A Protocol for a Systematic Review. Environment International 2024, 184, 108456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108456.

- Chandravarnan, P.; Agyei, D.; Ali, A. The Prevalence and Concentration of Mycotoxins in Rice Sourced from Markets: A Global Description. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2024, 146, 104394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104394.

- Authority, E.F.S.; Arcella, D.; Gómez Ruiz, J.Á.; Innocenti, M.L.; Roldán, R. Human and Animal Dietary Exposure to Ergot Alkaloids. EFSA Journal 2017, 15, e04902. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4902.

- EFSA; Arcella, D.; Altieri, A.; Horváth, Z. Human Acute Exposure Assessment to Tropane Alkaloids. EFSA Journal 2018, 16, e05160. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5160.

- EFSA; Binaglia, M. Assessment of the Conclusions of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Meeting on Tropane Alkaloids. EFSA Journal 2022, 20, e07229. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2022.7229.

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM); Knutsen, H.K.; Alexander, J.; Barregård, L.; Bignami, M.; Brüschweiler, B.; Ceccatelli, S.; Cottrill, B.; Dinovi, M.; Edler, L.; et al. Risks for Human Health Related to the Presence of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids in Honey, Tea, Herbal Infusions and Food Supplements. EFSA Journal 2017, 15, e04908. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4908.

- Pompa, C.; D’Amore, T.; Miedico, O.; Preite, C.; Chiaravalle, A.E. Evaluation and Dietary Exposure Assessment of Selected Toxic Trace Elements in Durum Wheat (Triticum Durum) Imported into the Italian Market: Six Years of Official Controls. Foods 2021, 10, 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040775.

- Rehman, K.; Fatima, F.; Waheed, I.; Akash, M.S.H. Prevalence of Exposure of Heavy Metals and Their Impact on Health Consequences. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 2018, 119, 157–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.26234.

- D’Amore, T.; Miedico, O.; Pompa, C.; Preite, C.; Iammarino, M.; Nardelli, V. Characterization and Quantification of Arsenic Species in Foodstuffs of Plant Origin by HPLC/ICP-MS. Life 2023, 13, 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13020511.

- Arcella, D.; Cascio, C.; Ruiz, J.Á.G. Chronic Dietary Exposure to Inorganic Arsenic. EFSA Journal 2021, 19, e06380. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6380.

- Coelho, J.P. Arsenic Speciation in Algae: Case Studies in Europe. In Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry; Duarte, A.C., Reis, V., Eds.; Arsenic Speciation in Algae; Elsevier, 2019; Vol. 85, pp. 179–198.

- Cubadda, F.; Jackson, B.P.; Cottingham, K.L.; Van Horne, Y.O.; Kurzius-Spencer, M. Human Exposure to Dietary Inorganic Arsenic and Other Arsenic Species: State of Knowledge, Gaps and Uncertainties. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 579, 1228–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.108.

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain Scientific Opinion on Acrylamide in Food. EFSA Journal 2015, 13, 4104. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4104.

- EFSA Results on Acrylamide Levels in Food from Monitoring Years 2007–2009 and Exposure Assessment. EFSA Journal 2011, 9, 2133. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2133.

- European Commission Commission Recommendation (EU) 2019/1888 of 7 November 2019 on the Monitoring of the Presence of Acrylamide in Certain Foods; 2019;

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM) Scientific Opinion on the Risks for Animal and Public Health Related to the Presence of Alternaria Toxins in Feed and Food. EFSA Journal 2011, 9, 2407. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2407.

- EFSA Dietary Exposure Assessment to Alternaria Toxins in the European Population. EFSA Journal 2016, 14, e04654. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4654.

- European Commission Commission Recommendation (EU) 2022/553 of 5 April 2022 on Monitoring the Presence of Alternaria Toxins in Food; 2022;

- Pacini, T.; D’Amore, T.; Sdogati, S.; Verdini, E.; Bibi, R.; Caporali, A.; Cristofani, E.; Maresca, C.; Orsini, S.; Pelliccia, A.; et al. Assessment of Alternaria Toxins and Pesticides in Organic and Conventional Tomato Products: Insights into Contamination Patterns and Food Safety Implications. Toxins 2025, 17, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17010012.

- European Commission Directive 2002/32/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 May 2002 on Undesirable Substances in Animal Feed; 2002;

- Verstraete, F. Risk Management of Undesirable Substances in Feed Following Updated Risk Assessments. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2013, 270, 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2010.09.015.

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation No (EU) 2019/627 - of 15 March 2019 - Laying down Uniform Practical Arrangements for the Performance of Official Controls on Products of Animal Origin Intended for Human Consumption in Accordance with Regulation No (EU) 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Amending Commission Regulation No (EC) No 2074/2005 as Regards Official Controls; p. 50;.

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/2158 of 20 November 2017 Establishing Mitigation Measures and Benchmark Levels for the Reduction of the Presence of Acrylamide in Food; 2017;

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012 of 9 March 2012 Laying down Specifications for Food Additives Listed in Annexes II and III to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Text with EEA Relevance); 2012;

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) 2019/1871 of 7 November 2019 on Reference Points for Action for Non-Allowed Pharmacologically Active Substances Present in Food of Animal Origin and Repealing Decision 2005/34/EC (Text with EEA Relevance); 2019;

- European Commission Regulation (EU) 2019/6 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on Veterinary Medicinal Products and Repealing Directive 2001/82/EC (Text with EEA Relevance)Text with EEA Relevance; 2019;

- Ingenbleek, L.; Lautz, L.S.; Dervilly, G.; Darney, K.; Astuto, M.C.; Tarazona, J.; Liem, A.K.D.; Kass, G.E.N.; Leblanc, J.C.; Verger, P.; et al. Risk Assessment of Chemicals in Food and Feed: Principles, Applications and Future Perspectives. 2020, 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1039/9781839160431-00001.

- Tarazona, J.V. Use of New Scientific Developments in Regulatory Risk Assessments: Challenges and Opportunities. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 2013, 9, e85–e91. https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.1445.

- Terron, A.; Marx-Stoelting, P.; Braeuning, A. The Use of NAMs and Omics Data in Risk Assessment. EFSA Journal 2022, 20, e200908. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2022.e200908.

- Moné, M.J.; Pallocca, G.; Escher, S.E.; Exner, T.; Herzler, M.; Bennekou, S.H.; Kamp, H.; Kroese, E.D.; Leist, M.; Steger-Hartmann, T.; et al. Setting the Stage for Next-Generation Risk Assessment with Non-Animal Approaches: The EU-ToxRisk Project Experience. Arch Toxicol 2020, 94, 3581–3592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-020-02866-4.

- EFSA - European Food Safety Authority Guidance on Harmonised Methodologies for Human Health, Animal Health and Ecological Risk Assessment of Combined Exposure to Multiple Chemicals. EFSA Journal 2019, 17, e05634. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5634.

- EFSA Guidance on Uncertainty Analysis in Scientific Assessments. EFSA Journal 2018, 16, e05123. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5123.

- EFSA Scientific Committee; Hardy, A.; Benford, D.; Halldorsson, T.; Jeger, M.J.; Knutsen, K.H.; More, S.; Mortensen, A.; Naegeli, H.; Noteborn, H.; et al. Update: Use of the Benchmark Dose Approach in Risk Assessment. EFSA Journal 2017, 15, e04658. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4658.

- Doménech, E.; Martorell, S. Review of the Terminology, Approaches, and Formulations Used in the Guidelines on Quantitative Risk Assessment of Chemical Hazards in Food. Foods 2024, 13, 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13050714.

- Dent, M.P.; Vaillancourt, E.; Thomas, R.S.; Carmichael, P.L.; Ouedraogo, G.; Kojima, H.; Barroso, J.; Ansell, J.; Barton-Maclaren, T.S.; Bennekou, S.H.; et al. Paving the Way for Application of next Generation Risk Assessment to Safety Decision-Making for Cosmetic Ingredients. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2021, 125, 105026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2021.105026.

- EFSA - European Food Safety Authority Existing Approaches Incorporating Replacement, Reduction and Refinement of Animal Testing: Applicability in Food and Feed Risk Assessment. EFSA Journal 2009, 7, 1052. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2009.1052.

- EFSA - European Food Safety Authority Development of a Roadmap for Action on New Approach Methodologies in Risk Assessment. EFS3 2022, 19. https://doi.org/10.2903/sp.efsa.2022.EN-7341.

- EFSA - European Food Safety Authority Guidance Document on Scientific Criteria for Grouping Chemicals into Assessment Groups for Human Risk Assessment of Combined Exposure to Multiple Chemicals. EFS2 2021, 19. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2021.7033.

- Grosssteiner, I.; Mienne, A.; Lucas, L.; L-Yvonnet, P.; Trenteseaux, C.; Fontaine, K.; Sarda, X. Cumulative Risk Assessment with Pesticides in the Framework of MRL Setting. EFSA Journal 2023, 21, e211009. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2023.e211009.

- Alaoui, A.; Christ, F.; Silva, V.; Vested, A.; Schlünssen, V.; González, N.; Gai, L.; Abrantes, N.; Baldi, I.; Bureau, M.; et al. Identifying Pesticides of High Concern for Ecosystem, Plant, Animal, and Human Health: A Comprehensive Field Study across Europe and Argentina. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 948, 174671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174671.

- EFSA Cumulative Dietary Risk Characterisation of Pesticides That Have Chronic Effects on the Thyroid. EFSA Journal 2020, 18, e06088. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6088.

- EFSA Cumulative Dietary Risk Characterisation of Pesticides That Have Acute Effects on the Nervous System. EFSA Journal 2020, 18, e06087. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6087.

- EFSA; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Anastassiadou, M.; Castoldi, A.F.; Cavelier, A.; Coja, T.; Crivellente, F.; Dujardin, B.; Hart, A.; Hooghe, W.; et al. Retrospective Cumulative Dietary Risk Assessment of Craniofacial Alterations by Residues of Pesticides. EFSA Journal 2022, 20, e07550. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2022.7550.

- Rossi, A.; Rossi, G.; Rosamilia, A.; Micheli, M.R. Official Controls on Food Safety: Competent Authority Measures. Italian Journal of Food Safety 2020, 9. https://doi.org/10.4081/ijfs.2020.8607.

- D’Amore, T.; Lo Magro, S.; Vita, V.; Di Taranto, A. Optimization and Validation of a High Throughput UHPLC-MS/MS Method for Determination of the EU Regulated Lipophilic Marine Toxins and Occurrence in Fresh and Processed Shellfish. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20030173.

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EC) No 333/2007 of 28 March 2007 Laying down the Methods of Sampling and Analysis for the Official Control of the Levels of Lead, Cadmium, Mercury, Inorganic Tin, 3-MCPD and Benzo(a)Pyrene in Foodstuffs (Text with EEA Relevance ); 2007; Vol. 088;

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/808 of 22 March 2021 on the Performance of Analytical Methods for Residues of Pharmacologically Active Substances Used in Food-Producing Animals and on the Interpretation of Results as Well as on the Methods to Be Used for Sampling and Repealing Decisions 2002/657/EC and 98/179/EC; 2021;

- International Organization for Standardization - ISO. ISO/IEC 17025:2017 General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories; 2017;

- H. Cantwell Eurachem Guide: The Fitness for Purpose of Analytical Methods – A Laboratory Guide to Method Validation and Related Topics 2025.

- Bianchi, F.; Giannetto, M.; Careri, M. Analytical Systems and Metrological Traceability of Measurement Data in Food Control Assessment. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2018, 107, 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2018.07.024.

- 1131; 110. DG-SANTE ANALYTICAL QUALITY CONTROL AND METHOD VALIDATION PROCEDURES FOR PESTICIDE RESIDUES ANALYSIS IN FOOD AND FEED SANTE 11312/2021;

- Hooda, A.; Vikranta, U.; Duary, R.K. Principles of Food Dairy Safety: Challenges and Opportunities. In Engineering Solutions for Sustainable Food and Dairy Production: Innovations and Techniques in Food Processing and Dairy Engineering; Chandra Deka, S., Nickhil, C., Haghi, A.K., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; pp. 35–65 ISBN 978-3-031-75834-8.

- Das, R.; Raj, D. Sources, Distribution, and Impacts of Emerging Contaminants – a Critical Review on Contamination of Landfill Leachate. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2025, 17, 100602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazadv.2025.100602.

- Li, X.; Shen, X.; Jiang, W.; Xi, Y.; Li, S. Comprehensive Review of Emerging Contaminants: Detection Technologies, Environmental Impact, and Management Strategies. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 278, 116420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116420.

- Khan, N.A.; López-Maldonado, E.A.; Majumder, A.; Singh, S.; Varshney, R.; López, J.R.; Méndez, P.F.; Ramamurthy, P.C.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, A.H.; et al. A State-of-Art-Review on Emerging Contaminants: Environmental Chemistry, Health Effect, and Modern Treatment Methods. Chemosphere 2023, 344, 140264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140264.

- Kirkeli, C.; Valdersnes, S.; Ali, A.M. Target and Non-Target Screening of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Fish Liver Samples from the River Nile in Sudan: A Baseline Assessment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2025, 211, 117388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.117388.

- Schymanski, E.L.; Zhang, J.; Thiessen, P.A.; Chirsir, P.; Kondic, T.; Bolton, E.E. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in PubChem: 7 Million and Growing. Environ Sci Technol 2023, 57, 16918–16928. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c04855.

- Cousins, I.T.; Johansson, J.H.; Salter, M.E.; Sha, B.; Scheringer, M. Outside the Safe Operating Space of a New Planetary Boundary for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 11172–11179. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c02765.

- Ali, A.M.; Higgins, C.P.; Alarif, W.M.; Al-Lihaibi, S.S.; Ghandourah, M.; Kallenborn, R. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Contaminated Coastal Marine Waters of the Saudi Arabian Red Sea: A Baseline Study. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021, 28, 2791–2803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09897-5.

- Ahrens, L.; Bundschuh, M. Fate and Effects of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in the Aquatic Environment: A Review. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2014, 33, 1921–1929. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2663.

- Arinaitwe, K.; Koch, A.; Taabu-Munyaho, A.; Marien, K.; Reemtsma, T.; Berger, U. Spatial Profiles of Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Mercury in Fish from Northern Lake Victoria, East Africa. Chemosphere 2020, 260, 127536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127536.

- Giesy, J.P.; Mabury, S.A.; Martin, J.W.; Kannan, K.; Jones, P.D.; Newsted, J.L.; Coady, K. Perfluorinated Compounds in the Great Lakes. In Persistent Organic Pollutants in the Great Lakes; Hites, R.A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006; pp. 391–438 ISBN 978-3-540-32990-9.

- Fenton, S.E.; Ducatman, A.; Boobis, A.; DeWitt, J.C.; Lau, C.; Ng, C.; Smith, J.S.; Roberts, S.M. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Toxicity and Human Health Review: Current State of Knowledge and Strategies for Informing Future Research. Environ Toxicol Chem 2021, 40, 606–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.4890.

- Rüdel, H.; Radermacher, G.; Fliedner, A.; Lohmann, N.; Koschorreck, J.; Duffek, A. Tissue Concentrations of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in German Freshwater Fish: Derivation of Fillet-to-Whole Fish Conversion Factors and Assessment of Potential Risks. Chemosphere 2022, 292, 133483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.133483.

- Hauser-Davis, R.A.; Bordon, I.C.; Kannan, K.; Moreira, I.; Quinete, N. Perfluoroalkyl Substances Associations with Morphometric Health Indices in Three Fish Species from Differentially Contaminated Water Bodies in Southeastern Brazil. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2021, 21, 101198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2020.101198.

- Omoike, O.E.; Pack, R.P.; Mamudu, H.M.; Liu, Y.; Strasser, S.; Zheng, S.; Okoro, J.; Wang, L. Association between per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Markers of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Environ Res 2021, 196, 110361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110361.

- Lemos, L.; Gantiva, L.; Kaylor, C.; Sanchez, A.; Quinete, N. American Oysters as Bioindicators of Emerging Organic Contaminants in Florida, United States. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 835, 155316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155316.

- Ogunbiyi, O.D.; Lemos, L.; Brinn, R.P.; Quinete, N.S. Bioaccumulation Potentials of Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Recreational Fisheries: Occurrence, Health Risk Assessment and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Coastal Biscayne Bay. Environmental Research 2024, 263, 120128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.120128.

- Panel), E.P. on C. in the F.C. (EFSA C.; Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; del Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L. (Ron); Leblanc, J.-C.; et al. Risk to Human Health Related to the Presence of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Food. EFSA Journal 2020, 18, e06223. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6223.

- Kasmuri, N.; Tarmizi, N.A.A.; Mojiri, A. Occurrence, Impact, Toxicity, and Degradation Methods of Microplastics in Environment-a Review. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2022, 29, 30820–30836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-18268-7.

- Campanale, C.; Massarelli, C.; Savino, I.; Locaputo, V.; Uricchio, V.F. A Detailed Review Study on Potential Effects of Microplastics and Additives of Concern on Human Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041212.

- Bocker, R.; Silva, E.K. Microplastics in Our Diet: A Growing Concern for Human Health. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 968, 178882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.178882.

- Gupta, P.; Mahapatra, A.; Manna, B.; Suman, A.; Ray, S.S.; Singhal, N.; Singh, R.K. Sorption of PFOS onto Polystyrene Microplastics Potentiates Synergistic Toxic Effects during Zebrafish Embryogenesis and Neurodevelopment. Chemosphere 2024, 366, 143462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.143462.

- Chen, Y.; Jin, H.; Ali, W.; Zhuang, T.; Sun, J.; Wang, T.; Song, J.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Bian, J.; et al. Co-Exposure of Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics with Cadmium Promotes Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Female Ducks through Oxidative Stress and Glycolipid Accumulation. Poultry Science 2024, 103, 104152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2024.104152.

- Ragusa, A.; Notarstefano, V.; Svelato, A.; Belloni, A.; Gioacchini, G.; Blondeel, C.; Zucchelli, E.; De Luca, C.; D’Avino, S.; Gulotta, A.; et al. Raman Microspectroscopy Detection and Characterisation of Microplastics in Human Breastmilk. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14, 2700. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14132700.

- Wu, D.; Feng, Y.; Wang, R.; Jiang, J.; Guan, Q.; Yang, X.; Wei, H.; Xia, Y.; Luo, Y. Pigment Microparticles and Microplastics Found in Human Thrombi Based on Raman Spectral Evidence. Journal of Advanced Research 2023, 49, 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2022.09.004.

- Horvatits, T.; Tamminga, M.; Liu, B.; Sebode, M.; Carambia, A.; Fischer, L.; Püschel, K.; Huber, S.; Fischer, E.K. Microplastics Detected in Cirrhotic Liver Tissue. EBioMedicine 2022, 82, 104147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104147.

- Leslie, H.A.; van Velzen, M.J.M.; Brandsma, S.H.; Vethaak, A.D.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Lamoree, M.H. Discovery and Quantification of Plastic Particle Pollution in Human Blood. Environ Int 2022, 163, 107199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107199.

- Ibrahim, Y.S.; Tuan Anuar, S.; Azmi, A.A.; Wan Mohd Khalik, W.M.A.; Lehata, S.; Hamzah, S.R.; Ismail, D.; Ma, Z.F.; Dzulkarnaen, A.; Zakaria, Z.; et al. Detection of Microplastics in Human Colectomy Specimens. JGH Open 2021, 5, 116–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgh3.12457.

- Marfella, R.; Prattichizzo, F.; Sardu, C.; Fulgenzi, G.; Graciotti, L.; Spadoni, T.; D’Onofrio, N.; Scisciola, L.; Grotta, R.L.; Frigé, C.; et al. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Atheromas and Cardiovascular Events. New England Journal of Medicine 2024. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2309822.

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Shi, L.; Jia, Y.; Sheng, H. Detection and Quantification of Microplastics in Various Types of Human Tumor Tissues. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 283, 116818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116818.

- Kuai, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xie, K.; Chen, J.; He, J.; Gao, J.; Yu, C. Long-Term Exposure to Polystyrene Microplastics Reduces Macrophages and Affects the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis in Mice. Toxicology 2024, 509, 153951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2024.153951.

- Liang, B.; Deng, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Huang, X.; Yang, X.; Du, J.; Ye, R.; et al. Gastrointestinal Incomplete Degradation Exacerbates Neurotoxic Effects of PLA Microplastics via Oligomer Nanoplastics Formation. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, 11, e2401009. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202401009.

- MacLeod, M.; Arp, H.P.H.; Tekman, M.B.; Jahnke, A. The Global Threat from Plastic Pollution. Science 2021, 373, 61–65. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abg5433.

- Chain (CONTAM), E.P. on C. in the F. Presence of Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Food, with Particular Focus on Seafood. EFSA Journal 2016, 14, e04501. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4501.

- EFSA EFSA Scientific Colloquium 25 – A Coordinated Approach to Assess the Human Health Risks of Micro- and Nanoplastics in Food. EFSA Supporting Publications 2021, 18, 6815E. https://doi.org/10.2903/sp.efsa.2021.EN-6815.

- Zhang, F.; Yu, X.; Tian, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhuang, P.; Jia, W.; Zhang, Y. Joint Control of Multiple Food Processing Contaminants in Maillard Reaction: A Comprehensive Review of Health Risks and Prevention. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2025, 24, e70138. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.70138.

- Qin, P.; Liu, D.; Wu, X.; Zeng, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Han, M.; Qie, R.; et al. Fried-Food Consumption and Risk of Overweight/Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and Hypertension in Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 6809–6820. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2021.1906626.

- Wang, Y.; Luo, W.; Han, J.; Khan, Z.A.; Fang, Q.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Qian, J.; et al. MD2 Activation by Direct AGE Interaction Drives Inflammatory Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 2148. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15978-3.

- Huang, M.; Zhuang, P.; Jiao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Association of Acrylamide Hemoglobin Biomarkers with Obesity, Abdominal Obesity and Overweight in General US Population: NHANES 2003-2006. Sci Total Environ 2018, 631–632, 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.338.

- Chiang, V.S.-C.; and Quek, S.-Y. The Relationship of Red Meat with Cancer: Effects of Thermal Processing and Related Physiological Mechanisms. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2017, 57, 1153–1173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2014.967833.

- IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 100C: Arsenic, Metals, Fibres, and Dusts; IARC - International Agency for Research on Cancer., Ed.; World Health Organization WHO-Press: Lyon, France, 2012; Vol. 100 C; ISBN 978-92-832-0135-9.

- IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 100 C, Arsenic, Metals, Fibres, and Dusts: This Publication Represents the Views and Expert Opinions of an IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Which Met in Lyon, 17 - 24 March 2009; International Agency for Research on Cancer, Weltgesundheitsorganisation, Eds. ; IARC: Lyon, 2012; 152. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 100 C, Arsenic, Metals, Fibres, and Dusts: This Publication Represents the Views and Expert Opinions of an IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Which Met in Lyon, 17 - 24 March 2009; International Agency for Research on Cancer, Weltgesundheitsorganisation, Eds.; IARC: Lyon, 2012; ISBN 978-92-832-1320-8.

- IARC Coffee, Tea, Mate, Methylxanthines and Methylglyoxal; ISBN 978-92-832-1251-5.

- IARC Some Naturally Occurring Substances: Food Items and Constituents, Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines and Mycotoxins; ISBN 978-92-832-1256-0.

- IARC Some Chemicals Present in Industrial and Consumer Products, Food and Drinking-Water; ISBN 978-92-832-1324-6.

- IARC Some Naturally Occurring and Synthetic Food Components, Furocoumarins and Ultraviolet Radiation; ISBN 978-92-832-1240-9.

- Food, Nutrition and Agriculture - 31/2002 Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/Y4267M/y4267m10.htm (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Flavourings (FAF); Younes, M.; Aquilina, G.; Castle, L.; Engel, K.-H.; Fowler, P.; Frutos Fernandez, M.J.; Fürst, P.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Gürtler, R.; et al. Scientific Opinion on Flavouring Group Evaluation 13 Revision 3 (FGE.13Rev3): Furfuryl and Furan Derivatives with and without Additional Side-Chain Substituents and Heteroatoms from Chemical Group 14. EFSA Journal 2021, 19, e06386. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6386.

- Ortu, E.; and Caboni, P. Levels of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural, Furfural, 2-Furoic Acid in Sapa Syrup, Marsala Wine and Bakery Products. International Journal of Food Properties 2017, 20, S2543–S2551. https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2017.1373668.

- Vella, C.; Attard, E. Consumption of Minerals, Toxic Metals and Hydroxymethylfurfural: Analysis of Infant Foods and Formulae. Toxics 2019, 7, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics7020033.

- Chongwatpol, J. A Technological, Data-Driven Design Journey for Artificial Intelligence (AI) Initiatives. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 29, 15933–15963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12459-8.

- Navigating Ethical Challenges in an AI-Enabled Food Industry. Food Science and Technology 2024, 38, 40–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsat.3803_10.x.

- Kim, D.; Kim, S.-Y.; Yoo, R.; Choo, J.; Yang, H. Innovative AI Methods for Monitoring Front-of-Package Information: A Case Study on Infant Foods. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0303083. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303083.

- Nfor, K.A.; Theodore Armand, T.P.; Ismaylovna, K.P.; Joo, M.-I.; Kim, H.-C. An Explainable CNN and Vision Transformer-Based Approach for Real-Time Food Recognition. Nutrients 2025, 17, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020362.

- Chhetri, K.B. Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Food Quality Control and Safety Assessment. Food Eng Rev 2024, 16, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12393-023-09363-1.

- Kudashkina, K.; Corradini, M.G.; Thirunathan, P.; Yada, R.Y.; Fraser, E.D.G. Artificial Intelligence Technology in Food Safety: A Behavioral Approach. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 123, 376–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2022.03.021.

- Qian, C.; Murphy, S.I.; Orsi, R.H.; Wiedmann, M. How Can AI Help Improve Food Safety? Annual Review of Food Science and Technology 2023, 14, 517–538. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-food-060721-013815.

- Mohammadpour, A.; Samaei, M.R.; Baghapour, M.A.; Alipour, H.; Isazadeh, S.; Azhdarpoor, A.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Nitrate Concentrations and Health Risks in Cow Milk from Iran: Insights from Deterministic, Probabilistic, and AI Modeling. Environmental Pollution 2024, 341, 122901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.122901.

- Rivas, D.; Vilas, C.; Alonso, A.A.; Varas, F. Derivation of Postharvest Fruit Behavior Reduced Order Models for Online Monitoring and Control of Quality Parameters During Refrigeration. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2013, 36, 480–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpe.12010.

- Kannapinn, M.; Schäfer, M.; Weeger, O. TwinLab: A Framework for Data-Efficient Training of Non-Intrusive Reduced-Order Models for Digital Twins. EC 2024. https://doi.org/10.1108/EC-11-2023-0855.

- Tao, F.; Qi, Q. Make More Digital Twins. Nature 2019, 573, 490–491. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-02849-1.

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems: New Findings and Approaches; Kahlen, F.-J., Flumerfelt, S., Alves, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 85–113 ISBN 978-3-319-38756-7.

- Adade, S.Y.-S.S.; Lin, H.; Johnson, N.A.N.; Nunekpeku, X.; Aheto, J.H.; Ekumah, J.-N.; Kwadzokpui, B.A.; Teye, E.; Ahmad, W.; Chen, Q. Advanced Food Contaminant Detection through Multi-Source Data Fusion: Strategies, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2025, 156, 104851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104851.

- Jin, Y.; Li, C.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, L. Simultaneous Quantitative Determination of Low-Concentration Preservatives and Heavy Metals in Tricholoma Matsutakes Based on SERS and FLU Spectral Data Fusion. Foods 2023, 12, 4267. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234267.

- Gu, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Rapid Determination of Potential Aflatoxigenic Fungi Contamination on Peanut Kernels during Storage by Data Fusion of HS-GC-IMS and Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2021, 171, 111361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2020.111361.

- Ríos-Reina, R.; Azcarate, S.M.; Camiña, J.M.; Goicoechea, H.C. Multi-Level Data Fusion Strategies for Modeling Three-Way Electrophoresis Capillary and Fluorescence Arrays Enhancing Geographical and Grape Variety Classification of Wines. Anal Chim Acta 2020, 1126, 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2020.06.014.

- Deng, J.; Ni, L.; Bai, X.; Jiang, H.; Xu, L. Simultaneous Analysis of Mildew Degree and Aflatoxin B1 of Wheat by a Multi-Task Deep Learning Strategy Based on Microwave Detection Technology. LWT 2023, 184, 115047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115047.

- Borràs, E.; Ferré, J.; Boqué, R.; Mestres, M.; Aceña, L.; Busto, O. Data Fusion Methodologies for Food and Beverage Authentication and Quality Assessment – A Review. Analytica Chimica Acta 2015, 891, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2015.04.042.

- Agriopoulou, S.; D’Amore, T.; Tarapoulouzi, M.; Varzakas, T.; Smaoui, S. Chemometrics in Mycotoxin Detection by Mass Spectrometry. In Mass Spectrometry in Food Analysis; WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2024; pp. 277–303 ISBN 9789811296239.

- Miedico, O.; Nardelli, V.; D’Amore, T.; Casale, M.; Oliveri, P.; Malegori, C.; Paglia, G.; Iammarino, M. Identification of Mechanically Separated Meat Using Multivariate Analysis of 43 Trace Elements Detected by Inductively Coupled Mass Spectrometry: A Validated Approach. Food Chemistry 2022, 397, 133842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133842.

- Berthiller, F.; Crews, C.; Dall’Asta, C.; Saeger, S.D.; Haesaert, G.; Karlovsky, P.; Oswald, I.P.; Seefelder, W.; Speijers, G.; Stroka, J. Masked Mycotoxins: A Review. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2013, 57, 165–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201100764.

| Legal Instrument | Description | Binding Nature | Examples | Ref |

| Regulation | Legislative acts that apply directly in all Member States without national implementation. | Legally binding in all Member States | Regulation (EC) No. 178/2002 (General Food Law) Regulation (EC) No. 1333/2008 (Food Additives) |

[10,11] |

| Directive | Set objectives that Member States must achieve, but each MS chooses how to implement them. | Legally binding, but requires transposition into national law | Directive 2009/128/EC (Pesticide Sustainable Use) | [12] |

| Decision | Legally binding acts applicable to specific MSs, businesses, or individuals. Often used in crisis management. | Legally binding for the addressed parties | Decision 2002/657/EC (Performance of analytical methods and the interpretation of results) | [13] |

| Recommendation | Non-binding guidance to encourage best practices and policy direction. | Not legally binding | Commission Recommendation (EU) 2017/84 (Mineral Oil Hydrocarbons in Food) Commission Recommendation (EU) No 2018/464 (Monitoring of metals and iodine in seaweed, halophytes and products based on seaweed) |

[14,15] |

| Opinion | A formal non-binding instrument used by EU institutions to express views or provide guidance without imposing obligations. | Not legally binding | Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on ‘Towards a Fair Food Supply Chain’ (Exploratory opinion) EESC 2021/02472 |

[16] |

| Report | Scientific assessments or policy evaluations that inform decision-making. | Not legally binding | Report From the EC to the EP and the Council on food and food ingredients treated with ionizing radiation for the years 2020-2021 COM/2023/676 |

[17] |

| Others | Minutes, Communication, Staff working document, Proposal for a regulation, Question. | Not legally binding | Several types of acts |

| Chemical Class | Subclasses | Key Regulations | Notes | Ref |

| Chemical Contaminants | Mycotoxins (aflatoxins, ochratoxin A, patulin, deoxynivalenol, zearalenone, fumonisins, citrinine, ergot sclerotia and ergot alkaloids) Plant toxins (erucic acid, tropane alkaloids, hydrocyanic acid, pyrrolizidine alkaloids, opium alkaloids, Δ9-THC) Metals and other elements (lead, cadmium, mercury, arsenic, inorganic tin) PCBs and Dioxins Perfluoroalkyl substances Processing contaminants (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH): benzo(a)pyrene, sum of 4 PAHs; 3-monochloropropane-1,2-diol (3-MCPD), glycidyl fatty acid esters) Others (nitrates, melamine, perchlorate) |

Regulation (EU) No. 2023/915 | Establishes maximum levels for contaminants in food | [54] |

| Marine Biotoxins | paralytic shellfish poison (PSP), amnesic shellfish poison (ASP), okadaic acid and dinophysistoxins, yessotoxins, azaspiracids | Regulation (EC) No. 627/2019 | Establish maximum levels and control plans | [81] |

| Acrylamide | Regulation (EU) No. 2017/2158 | Implementation of acrylamide reduction measures | [82] | |

| Recommendation (EU) No. 2019/1888 | Monitoring the presence of acrylamide in certain foods | [74] | ||

| AlternariaToxins | alternariol, alternariol monomethyl ether and tenuazonic acid | Recommendation (EU) No. 2022/553 | Monitoring the presence of Alternaria toxins in food | [77] |

| Food Additives | 26 functional classes (sweeteners, colours, preservatives, antioxidants, carriers, acids, acidity regulators, anti-caking, anti-foaming and bulking agents, emulsifiers, emulsifying salts, flavour enhancers, firming, gelling, glazing, raising and foaming agents, humectants, modified starches, packaging gases, propellants, sequestrants, stabilisers, thickeners, flour treatment agents) | Regulation (EC) No. 1333/2008; | Defines approved food additives, their conditions of use |

[11] |

| Regulation (EU) No. 231/2012 | purity criteria of food additives | [83] | ||

| Flavourings | flavouring substances, flavouring preparations, thermal process flavourings, smoke flavourings, flavour precursors or other flavourings or mixtures | Regulation (EC) No. 1334/2008 | [40] | |

| Pesticide Residues | acaricides, bactericides, fungicides, herbicides, insecticides, larvicides, rodenticides | Regulation (EC) No. 396/2005; | Sets MRLs for pesticides | [41] |

| Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009 | placing of plant protection products on the market | [45] | ||

| Directive No. 2009/128/EC | promotes sustainable pesticide use | [12] | ||

| Veterinary Drug Residues | antibiotics, hormones, anabolic steroids, FANS (…) | Regulation (EU) No. 37/2010 | Establishes MRLs for veterinary medicinal products in food-producing animals. | [47] |

| Regulation (EC) No. 470/2009 | Outlines the process for determining MRLs for veterinary medicinal products in food. | [48] | ||

| Regulation (EU) No. 2019/1871 | Establishes reference limits for unauthorized pharmacologically active substances detected in food of animal origin | [84] | ||

| Regulation (EU) No. 2019/6 | Specifies the rules governing the approval and use of veterinary medicinal products | [85] | ||

| Food Contact Materials | monomers, other starting substances, macromolecules obtained from microbial fermentation, additives and polymer production aids contaminants |

Regulation (EC) No. 1935/2004 | Establishes safety requirements and migration limits for materials in contact with food. | [50] |

| Regulation (EU) No. 10/2011 | Criteria and authorization of plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with food | [49] |

| Parameter | Description | Main Acceptance Criteria |

| Selectivity/ Specificity |

the ability of the method to distinguish analyte from the possible interferences | no interferences near the analyte signal (e.g., ± 5% retention time in a chromatographic methods) |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | the minimum reliably detectable amount of an analyte | method-specific LOD/LOQ thresholds |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | the lowest concentration that can be reliably quantified | method-specific LOD/LOQ thresholds |

| Linearity | the ability to obtain test results, which are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the sample | R² > 0.98 - 0.99 |

| Accuracy | closeness of an analytical measurement to the true or accepted reference value; it is described in the ISO 5725-1 as sum of precision and trueness | it is described in the ISO 5725-1 as sum of precision and trueness |

| Precision | the closeness of agreement between the measured values obtained by the replicate measurements on the same or similar objects under specified conditions; generally estimated as (relative) standard deviation (RSD) or coefficient of variation (CV) | Intermediate precision (n≥ 6) CV(%) < 5-25 RSD< 15% |

| Trueness | the agreement between a reasonably large number of measurements and true value (reference value); generally estimated as recovery (R) | R(%) = 70-120 |

| Robustness | stability of method performance under varying conditions |

minor changes (e.g., pH, mobile phases) major changes (matrix) |

| Matrix effect | an influence of one or more co-extracted compounds from the sample on the measurement of the analyte concentration or mass. It may be observed as an increased or decreased detector response compared with that produced by solvent solutions of the analyte (ME) | ME(%) ≤ 20 |

| Uncertainty | a range around the reported result within which the true value is expected to fall with a specified level of confidence, typically 95% | U ≤ 50% of MRL for contaminants |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).