1. Introduction

Megaprojects, which include large-scale construction, manufacturing facilities, and infrastructure systems, are essential to contemporary economic development but present considerable management challenges (Flyvbjerg, 2014; Mahmood et al., 2024). These initiatives are marked by significant financial investments, extended timelines, technical complexity, and multifaceted stakeholder interactions (Ma et al., 2020). As a result, they frequently experience cost overruns and schedule delays, often failing to deliver their expected long-term benefits (Shafaay et al., 2025; Flyvbjerg, 2014). Thus, effective risk management and robust decision-making processes are crucial for success (Alamdari et al., 2023; Yoshiura et al., 2023).

The Front-End Planning and Design (FEED) phase is particularly influential in shaping a megaproject's lifecycle outcomes (Project Management Institute, 2021; Shafaay et al., 2025). Decisions regarding project scope, technology, and design made during this stage profoundly impact subsequent costs, performance, and overall value realization. Errors or inadequate analyses during FEED can lead to significant difficulties and expenses in later phases (Flyvbjerg, 2014; Peiman et al., 2023).

The understanding of “value” in this context has shifted from conventional metrics focused solely on time, cost, and scope (Project Management Institute, 2021). Modern perspectives advocate for a multi-dimensional approach, requiring a balance between initial capital expenditures (CAPEX), long-term operational costs (OPEX), technical performance, and increasingly, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors (Mitoula & Papavasileiou, 2023; Cortés et al., 2023). Growing societal expectations and the rise of sustainable finance have made environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and effective governance critical components influencing project evaluations and stakeholder acceptance (Chen et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2022).

Despite this expanded definition of value, notable gaps persist in practical implementation during the FEED phase. There is often an absence of systematic methods to quantify the various factors (value drivers) that shape lifecycle performance and satisfy diverse stakeholder priorities (Alamdari et al., 2023). Additionally, early-stage decisions typically lack the rigorous, data-driven analysis necessary to assess complex trade-offs, such as balancing upfront costs with long-term sustainability benefits (Rosłon, 2022). The digital landscape remains fragmented, with tools like Building Information Modeling (BIM) and specialized simulation software available, yet integrated platforms for comprehensive, automated evaluation and design optimization are scarce (Cassandro et al., 2024; Wijayasekera et al., 2022). This fragmentation leads to reliance on manual and subjective assessment methods, limiting the ability to efficiently explore a broad range of design options (Yoshiura et al., 2023). Moreover, the potential of advanced technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and sophisticated data analytics to enhance decision-making processes in FEED remains largely underutilized in the industry (Datta et al., 2024; Taboada et al., 2023; Adamantiadou & Tsironis, 2025).

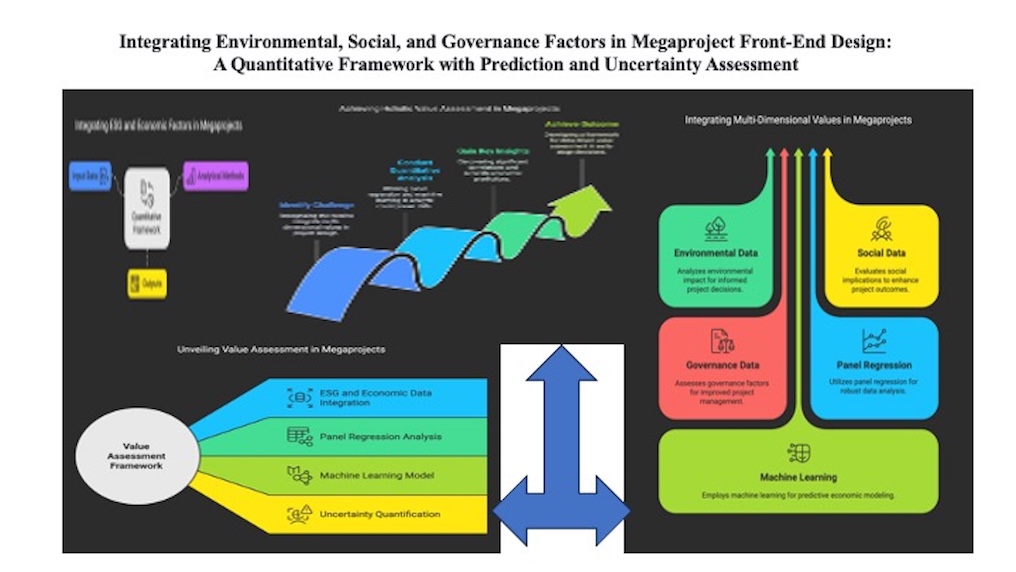

This research addresses the central problem arising from these gaps: the need for an integrated, computationally enabled framework to facilitate multi-objective value assessment and optimization during the critical front-end planning of megaprojects.

The purpose of this study is to develop foundational knowledge and propose a methodological framework for future automated digital tools aimed at improving value-driven decision-making in megaproject FEED. The goal is to clarify how various factors, particularly economic performance indicators and relevant ESG metrics, interact and can be quantitatively assessed, taking into account contextual influences such as regulations and institutional norms. Insights will be drawn from Institutional Theory, the Porter Hypothesis, and Regulatory Capture Theory.

This study aims to answer the following research questions:

-

1.

What quantifiable economic, social, and environmental factors (available as country-level indicators) significantly correlate with variations in national house price indices over time, while controlling for country-specific fixed effects?

-

2.

How effectively can machine learning models (serving as Automated Valuation Models - AVMs) predict national house price indices using lagged indicators, and how reliably can the associated prediction uncertainty be quantified using methods like Conformal Prediction?

-

3.

What are the key data, modeling (e.g., panel regression, ML), and computational considerations (e.g., managing multicollinearity, implementing uncertainty quantification) necessary for developing an integrated evaluation approach?

This research employs a quantitative methodology, analyzing a constructed panel dataset that merges country-level ESG indicators and OECD house price indices (c. 2009-2023). Key analytical steps include data preprocessing (imputation checks, lagging), multicollinearity assessment (VIF analysis and feature reduction for regression models), panel data regression (focusing on Fixed Effects with clustered standard errors), and AVM development using Random Forest with Conformal Prediction for uncertainty quantification. The study emphasizes the decision context of the FEED stage for large-scale construction, manufacturing, and infrastructure projects. While aiming for broader applicability, the empirical analysis utilizes cross-country data, recognizing potential limitations in generalizing findings without considering specific project-level or regional data. This work focuses on establishing the conceptual and methodological foundation of the framework rather than on developing a final software tool.

This study contributes to the academic field by integrating diverse literature streams (project management, value assessment, digital technology, ESG, and relevant theories) and applying advanced panel data and machine learning techniques (including uncertainty quantification) to the megaproject FEED context. It provides empirical insights into the complex relationships between country-level ESG factors and economic performance proxies. Practically, the research lays the groundwork for developing advanced digital decision support tools, which could enhance stakeholder alignment, risk management, and overall value delivery in complex projects. Additionally, it offers insights relevant to policymakers regarding the interplay of regulation, sustainability, and project outcomes.

2. Materials & Methods

This study employed a quantitative methodology using secondary panel data. The design involved merging country-level time-series data on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) indicators with national house price indices. Subsequent analyses included data preprocessing, multicollinearity assessment, panel data regression modeling (Pooled OLS, Fixed Effects, Random Effects), and machine learning-based predictive modeling (Automated Valuation Model - AVM) with uncertainty quantification.

2.1. Data Sources and Sample Collection

Two primary datasets were sourced from the World Bank and the OECD databases, ESG and Macroeconomic Country-level indicators for the period c. 2008-2023 were obtained from the World Bank Databank's “Environment, Social and Governance” collection (World Bank, n.d.-b). While House Price Index “Real house price indices (2015=100)” for OECD member and partner countries covering the period c. 2009-2024 were extracted from the OECD Data Explorer platform (“Analytical house prices indicators” dataset) (OECD, n.d.).

2.1.1. Multicollinearity Assessment

Multicollinearity among the contemporaneous independent variables intended for OLS-based panel models was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), calculated via “statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence.variance_inflation_factor” (Seabold & Perktold, 2010) after adding a constant (sm.add_constant). An iterative procedure was applied, the predictor with the highest VIF above a threshold of 10.0 was removed, and VIFs were recalculated until all remaining predictors were below this threshold. This resulted in a reduced set of predictors (X_panel_processed) used for subsequent panel regressions.

2.1.2. Statistical Analysis and Modeling

All analyses were performed using Python, primarily with the statsmodels (Seabold & Perktold, 2010), linearmodels (Sheppard, 2024), and scikit-learn (Pedregosa et al., 2011) libraries.

To analyze the contemporaneous association between ESG/macro factors and house price indices while controlling for country differences, standard panel data models were estimated using the linearmodels library. The dependent variable was house_price_index, and the independent variables were the VIF-reduced set of contemporaneous indicators (X_panel_processed).

The “Pooled OLS” was estimated using PooledOLS. This served as a baseline but ignores the panel structure. Meanwhile, the “Fixed Effects (Entity)” was estimated using PanelOLS with entity_effects = True. This model controls for time-invariant, unobserved heterogeneity across countries by including country-specific intercepts. Subsequently, the “Random Effects” was estimated using “Random-Effects”. This model assumes country-specific effects are random and uncorrelated with the regressors. Standard ErrorsfFor all panel models were calculated using the cluster-robust standard errors (cov_type='clustered', cluster_entity=True) were calculated to account for potential heteroskedasticity and serial correlation within countries. Ultimately, for the “Model Selection (FE vs. RE)”, an F-test for poolability (comparing FE against Pooled OLS) was examined from the FE output. A Hausman-like test was conducted using “linearmodels.panel.compare” between the (unclustered) FE and RE models to assess the consistency of the RE estimator. Based on these tests, the Fixed Effects model was identified as the preferred specification for interpreting within-country effects.

2.1.3. Automated Valuation Model (AVM) and Uncertainty Quantification (UQ)

A machine learning approach was used for prediction and UQ, employing the scikit-learn (Pedregosa et al., 2011) and mapie (Taquet et al., 2023) libraries.

A RandomForestRegressor served as the base predictive model. The full set of lagged independent variables and the lagged dependent variable were used as predictors. Subsequently, the data was partitioned into training (60%), calibration (20%), and test (20%) sets using train_test_split. For the “UQ Method”, conformal prediction was implemented using (mapie.regression.MapieRegressor with method =“plus” and cv = “split”). The model was fit on the training data, providing the calibration data (X_calib, y_calib) during the “.fit()” step. Ultimately, point predictions were evaluated using Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and R-squared (R²). Prediction intervals generated at α=0.1 were evaluated based on empirical coverage rate and average interval width on the test set. Feature importances were derived from the base “RandomForestRegressor”.

All data processing and analysis were performed using Python version 3.11 and relevant libraries including pandas, numpy, statsmodels, scikit-learn, linearmodels, and mapie.

3. Results

This study employed a comprehensive panel data regression analysis, Automated Valuation Models (AVM), and an extensive literature review to investigate the global impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors on the housing price index.

3.1. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review: Value Decisions in Megaprojects

Understanding value delivery in megaprojects, particularly during the influential front-end planning (FEED) stages where complex trade-offs involving economic, social, environmental, and technical factors are made, necessitates multiple theoretical perspectives. Decisions at this stage are rarely purely technical or economic; inherently, they are embedded within complex institutional and regulatory environments and shaped by organizational capabilities and strategic responses (Ma et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2022). This study fundamentally employs three complementary theoretical lenses—Institutional Theory, the Porter Hypothesis, and the Theory of Regulatory Capture—to structure the analysis. Essentially, these frameworks collectively help explain why certain value drivers gain prominence, how external pressures like regulations might shape project choices and potentially spur innovation, and what political-economic dynamics could influence the de facto impact of these pressures.

3.1.1. Institutional Influences on Megaproject Value and Practices

Institutional theory provides a robust lens for analyzing how organizations, including those involved in megaprojects, adapt to their environments to secure legitimacy and resources (Scott, 2014). It posits that both formal institutions (e.g., laws, and specific regulations like energy performance standards) and informal institutions (e.g., societal norms, professional ethics, and market expectations) exert powerful influences (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Formal regulations, such as environmental impact assessment mandates or safety protocols, directly shape project requirements and influence the weighting of value drivers in decision-making (Erdede & Bektaş, 2024; Kou & Liu, 2025; Ma et al., 2020). Furthermore, the perceived quality and consistent enforcement of these rules ('rule of law') can demonstrably impact project risks and performance (Peiman et al., 2023).

Meanwhile, informal institutions like growing societal awareness of climate change and resource depletion create normative pressures favoring sustainable practices, such as green building, often exceeding minimum legal compliance (Xie et al., 2022). Investor demands for credible Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reporting and performance represent a potent mimetic and normative force (Cortés et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Organizations ostensibly integrate ESG factors to maintain legitimacy, access sustainable finance markets (Lin et al., 2022), and secure the 'social license to operate' from stakeholders including local communities (Mitoula & Papavasileiou, 2023). Consequently, understanding these institutional pressures is key to explaining the increasing adoption of Green Construction Practices (GCPs) and sustainable materials (Ngayakamo & Onwualu, 2022), which may be driven by coercive, mimetic, or normative mechanisms, often varying across different institutional contexts (Ahmed et al., 2024; Hall et al., 2023).

3.1.2. Regulation, Innovation, and Competitiveness: The Porter Hypothesis

Contrasting with traditional views of regulation as purely burdensome, the Porter Hypothesis suggests that well-designed, stringent environmental regulations can act as catalysts for innovation (Porter & Van-der-Linde, 1995; Sun et al., 2022). Theoretically, this "innovation offset" might not only reduce negative environmental impacts but also enhance resource efficiency, foster new technologies, and potentially improve a firm's or project's overall competitiveness and economic performance. The 'weak' version postulates regulation stimulates specific innovations, while the 'strong' version posits this leads to enhanced productivity or competitiveness (Guan et al., 2023; Wu, 2023).

In the megaproject domain, stringent environmental rules could conceivably push firms towards innovative, sustainable materials (Ngayakamo & Onwualu, 2022), energy-efficient technologies (Sharma & Gupta, 2024; Iqbal et al., 2025), and construction methods (Ahmed et al., 2024). Such innovations might lead to lifecycle cost savings that offset initial compliance investments. Empirically, recent studies provide nuanced support, indicating environmental regulation can spur innovation and sometimes positively influence productivity or financial performance, though these effects are often heterogeneous depending on the type of regulation, industry context, and innovation measured (Chen et al., 2022; Guan et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2022; Peng, 2023; Sun et al., 2022; Stylianou et al., 2025; Wu, 2023). This resonates with sustainable finance principles, where projects exceeding regulatory minimums might attract investment due to perceived lower transition risk and potential long-term value creation (Lin et al., 2022; Stylianou et al., 2025).

3.1.3. The Countervailing Force: Regulatory Capture

Conversely, the theory of regulatory capture offers a critical perspective, suggesting that regulatory bodies may become heavily influenced or effectively 'captured' by the industries they oversee (Stigler, 1971; Laffont & Tirole, 1991). This capture can arise from information asymmetries, lobbying efforts, or revolving-door personnel exchanges, potentially leading to regulations that favour industry interests over broader public welfare. In the megaproject arena, this could manifest as weakened environmental or safety standards (Ali & Bucher, 2021), ineffective enforcement regimes, or biased permitting processes (Peiman et al., 2025), thereby undermining both genuine sustainability efforts and the innovation-driving potential suggested by the Porter Hypothesis (Hall et al., 2023; Cao & Nie, 2024). Consequently, assessing the real-world impact of regulations on project value necessitates considering the potential for capture.

3.1.4. Synthesizing Theory and Framing the Literature

Integrating these three theories provides a multi-layered understanding: Institutional theory sets the broad context of norms and rules defining value; the Porter Hypothesis highlights a potential positive dynamic linking regulation, innovation, and value; while Regulatory Capture introduces a critical lens on how political-economic factors can mediate or undermine these processes. This integrated perspective allows an analysis that moves beyond purely technical assessments to consider how value is socially constructed, institutionally shaped, and potentially politically influenced, guiding the examination of relevant literature.

3.1.5. Megaproject Characteristics and FEED Challenges

The literature consistently highlights the unique challenges of megaprojects stemming from their scale, complexity, duration, and stakeholder diversity (Flyvbjerg, 2014; Mahmood et al., 2024; Ma et al., 2020). These factors inherently contribute to heightened risk exposure across technical, financial, social, and environmental dimensions (Huangfu et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2022). Performance issues, particularly cost and schedule overruns, are persistent problems often rooted in the FEED phase (Flyvbjerg, 2014; Shafaay et al., 2025). Effective FEED, involving robust feasibility studies, clear scope definition, stakeholder alignment, and early risk assessment, is indisputably critical for mitigating these issues and maximizing lifecycle value (Project Management Institute, 2021; Peiman et al., 2025), though practical implementation often falls short due to various pressures and biases (Flyvbjerg, 2014).

3.1.6. Evolving Concepts of Value and Lifecycle Assessment

Value Management (VM) provides systematic methodologies for function-cost analysis to enhance project value (SAVE International, 2007). However, the definition of 'value' itself has progressively expanded beyond direct economic returns to encompass lifecycle performance, functionality, maintainability, safety (Kou & Liu, 2025), stakeholder satisfaction (Onubi et al., 2021), and ESG criteria (Jing et al., 2023; Zeng et al., 2022). Identifying and quantifying these multi-dimensional value drivers remains a significant challenge, requiring diverse metrics and methods, from financial calculations to simulations and qualitative stakeholder input (Marnewick et al., 2024). While Lifecycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) and Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) are established tools (Reffat et al., 2004), achieving truly integrated, quantitative lifecycle value assessment that balances all dimensions remains an area for development.

3.1.7. Decision Support, Digital Technologies, and Automation Potential

Decision Support Systems (DSS), particularly those employing Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) methods like AHP, ANP, ELECTRE, EDAS, and BWM, offer structured approaches to navigate complex trade-offs inherent in FEED (Turban et al., 2011; Yoshiura et al., 2023; Hatefi et al., 2025; Sharma & Gupta, 2024; Wang et al., 2024). Furthermore, digital technologies are rapidly evolving in the Architecture, Engineering, Construction, and Operations (AECO) sector. Building Information Modeling (BIM) serves as a central data repository and enabler for various analyses (Cassandro et al., 2024; Eastman et al., 2011; Saleh et al., 2024a). Advanced simulation tools support performance-based design (Rosłon, 2022), while the application of Data Analytics, AI, and ML is growing for prediction, optimization, risk assessment, and text mining (Datta et al., 2024; Taboada et al., 2023; Adamantiadou & Tsironis, 2025; Wijayasekera et al., 2022; Yan et al., 2022).

The emergence of PropTech brings many of these innovations (BIM, IoT, AI/ML) under one umbrella relevant to the project lifecycle (Saleh et al., 2024b; Sharma & Gupta, 2024). Simultaneously, intersections with FinTech (e.g., LendTech for finance, InsurTech for risk) and RegTech (compliance automation) are becoming increasingly important (Wijayasekera et al., 2022). Technologies like Blockchain/DLT are also being explored for enhanced transparency and contract automation (Cheng et al., 2023). Nonetheless, a key challenge identified in the literature is the fragmentation of these tools and the lack of integrated platforms capable of holistic, automated value assessment and optimization, especially during FEED (Wijayasekera et al., 2022).

3.1.8. ESG Integration and Financial Implications

The push for sustainability is evident through the adoption of Green Construction Practices (GCPs), the use of sustainable materials, and green building certifications (Ahmed et al., 2024; Ngayakamo & Onwualu, 2022; Erdede & Bektaş, 2024). Beyond project-specific practices, broader ESG frameworks are increasingly applied to real asset investments, emphasizing comprehensive reporting across environmental, social, and governance dimensions (Cortés et al., 2023). Moreover, a significant body of research explores the financial materiality of ESG performance. Strong ESG credentials, sometimes linked to regulatory pressure (as suggested by the Porter Hypothesis), are increasingly associated with potential benefits like enhanced financial performance, innovation, reduced risk perception, and improved access to sustainable finance (Ahmed et al., 2024; Stylianou et al., 2025; Wu, 2023).

3.1.9. Synthesis and Research Niche

Synthesizing the literature reveals considerable progress in understanding megaproject complexities, evolving value concepts, specific digital tools, and ESG integration. However, a critical research niche exists at the intersection of these areas. There is a persistent lack of integrated frameworks and methodologies capable of holistically and quantitatively evaluating multi-dimensional value drivers during FEED, explicitly considering trade-offs and contextual factors. Crucially, the potential for automating this complex evaluation and design optimization process using AI/ML within an integrated digital environment (linking project data with PropTech/FinTech functionalities) remains largely unexplored territory for megaproject FEED. This research directly targets this niche by seeking to develop the necessary knowledge base and methodological framework to bridge these gaps, informed by empirical analysis and grounded in relevant theoretical perspectives.

3.2. Analysis of Panel Data Regression: Pooled OLS

This section presents the empirical findings from the quantitative analyses. Results for the multicollinearity diagnostics, panel data regression models, and model specification testing are presented sequentially, followed by the Automated Valuation Model (AVM) outcomes.

Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) were calculated for the 34 contemporaneous independent variables to assess multicollinearity before panel regression. An iterative removal process excluded predictors with VIF > 10.00. life_expectancy_at_birth_total_years (initial VIF: 32.55) and rule_law_estimate (subsequent VIF: 30.99) were removed. The maximum VIF among the remaining 32 predictors was 8.57. This VIF-reduced set of predictors was used for the panel regression models described below.

Pooled OLS, Fixed Effects (FE), and Random Effects (RE) models were estimated using the VIF-reduced set of 32 contemporaneous predictors and 650 country-year observations. Cluster-robust standard errors (by country) were applied.

3.2.1. Pooled OLS Model

The Pooled OLS estimation yielded an overall R-squared of 0.50 (

Table 1). The model's predictors were collectively significant (Robust F (32, 617) = 49.50, p < 0.001).

Table 2 presents the parameter estimates. Variables with statistically significant negative coefficients (p < 0.05) included economic_and_social_rights_performance_score (β = -2.49), energy_use_kg_oil_equivalent_per_capita (β = -0.00), gini_index (β = -0.26), individuals_using_the_internet_population (β = -0.12), and renewable_electricity_output_total_electricity_output (β = -0.14). Significant positive coefficients (p < 0.05) were found for income_share_held_by_lowest_20 (β = 0.90) and ratio_female_to_male_labor_force_participation_rate_modeled_ilo_estimate (β = 0.45).

3.2.2. Fixed Effects (FE) Model

The Fixed Effects (Entity) model, controlling for time-invariant country characteristics, achieved a within-country R-squared of 0.588 (

Table 3). This indicates the model explained approximately 58.8% of the temporal variation in house price indices within countries. Diagnostic testing (F-test for Poolability p < 0.001) supported the inclusion of fixed effects over the Pooled OLS specification. The overall model significance was confirmed (Robust F (32, 571) = 20.720, p < 0.001).

Parameter estimates (

Table 4) revealed several statistically significant (p < 0.05) within-country associations. Positive coefficients were found for coastal_protection (β = 0.05) and literacy_rate_adult_total_people_ages_15_and_above (β = 0.04). Negative coefficients were found for economic_and_social_rights_performance_score (β = -2.67), energy_imports_net_energy_use (β = -0.03), energy_use_kg_oil_equivalent_per_capita (β = -0.00), individuals_using_the_internet_population (β = -0.15), and population_ages_65_and_above_total_population (β = -0.70). gdp_growth_annual (p = 0.079) and level_water_stress... (p = 0.056) were marginally significant (p < 0.10).

3.2.3. Random Effects (RE) Model

The Random Effects model was also estimated (

Table 5). It exhibited a high overall R-squared (0.980), largely driven by between-country variation (R-squared Between = 0.990). Parameter estimates are shown in

Table 6.

3.2.4. Model Specification Testing

A Hausman-type comparison between the Fixed Effects and Random Effects models was conducted (

Table 7). The observed differences in coefficient estimates and significance levels between the two models, alongside the significant F-test for poolability (

Table 3), indicated that the assumptions underlying the Random Effects model were likely violated, favoring the Fixed Effects specification for consistent estimation of within-country effects.

3.3. Automated Valuation Model (AVM) and Uncertainty Quantification (UQ)

A Random Forest model was developed as an AVM using the full set of 35 lagged predictors.

3.3.1. AVM Performance and Feature Importance

The AVM achieved an R-squared of 0.87 and an RMSE of 6.88 on the test set. The lagged house price index was the most dominant predictor (61.57% importance). Several lagged ESG and economic indicators also contributed to predictive performance.

Table 8 details the performance metrics and top 15 feature importance.

3.3.2. Uncertainty Quantification Using Conformal Prediction

Using MAPIE for conformal prediction (α=0.10), the generated 90% prediction intervals exhibited an empirical coverage of 90.80% on the test data, close to the nominal target. The mean width of these intervals was 23.998 index points.

Table 9 provides sample predictions with intervals and summarizes the UQ performance.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to develop foundational knowledge and a methodological framework for improving value-driven decision-making during the Front-End Planning and Design (FEED) phase of megaprojects, focusing on the integration of economic, social, and environmental factors through quantitative analysis and advanced digital techniques. The discussion interprets the empirical findings from the panel data regression and Automated Valuation Model (AVM) analyses in light of the research questions, theoretical underpinnings, and existing literature, while also considering practical implications and limitations.

4.1. Synthesis of Key Findings with RQs

The research questions posed guided the empirical investigation, yielding several key findings.

Addressing RQ1: What quantifiable factors significantly correlate with variations in national house price indices (controlling for fixed effects)? The Fixed Effects (FE) panel regression model (

Table 4), preferred based on diagnostic tests (

Table 3 and

Table 7), revealed significant within-country associations. Notably, improved coastal_protection (β = 0.05) and higher literacy_rate_adult_total_people_ages_15_and_above (β = 0.04) were positively associated with house price index changes. Conversely, factors like a higher economic_and_social_rights_performance_score (β = -2.67), greater reliance on energy_imports_net_energy_use (β = -0.03), higher energy_use_kg_oil_equivalent_per_capita (β = -0.00), increased individuals_using_the_internet_population (β = -0.15), and a larger share of population_ages_65_and_above_total_population (β = -0.70) showed significant negative associations. Marginally significant negative associations were found for gdp_growth_annual (p=0.08) and a positive association for level_water_stress. (p=0.06). These findings highlight a complex interplay between environmental adaptation (coastal protection), social development (literacy, demographics), economic factors (energy use/imports, GDP growth), governance proxies (economic/social rights score), and the macroeconomic indicator (house prices).

Addressing RQ2: How effectively can machine learning models (AVMs) predict national house price indices using lagged indicators, and how reliably can uncertainty be quantified? The Random Forest-based AVM demonstrated strong predictive performance on the test set, achieving an R-squared of 0.87 and an RMSE of 6.88 (

Table 8). While the lagged house_price_index_lag1 was the dominant predictor (61.57% importance), several lagged ESG and economic indicators, such as renewable_electricity_output..._lag1 (10%), economic_and_social_rights_performance_score_lag1 (6%), and fossil_fuel_energy_consumption_total_lag1 (4%), contributed meaningfully to the prediction. Furthermore, using Conformal Prediction via MAPIE (Taquet et al., 2023), the study successfully generated 90% prediction intervals with an empirical coverage of 90.80% on the test set, closely matching the target and demonstrating the feasibility of reliable uncertainty quantification (UQ) for such predictive models (

Table 9).

Addressing RQ3: What are the key data, modeling, and computational considerations for an integrated evaluation approach? The study underscored the necessity of several key steps: sourcing and merging diverse datasets (e.g., World Bank, OECD); rigorous data preprocessing including handling missing data (imputation checks) and appropriate lagging of predictors for forecasting; systematic multicollinearity assessment using VIF and iterative feature reduction for robust regression modeling; employing appropriate panel data models (Pooled OLS, FE, RE) and selecting the best fit based on statistical tests (e.g., Hausman test favouring FE,

Table 7); leveraging machine learning (e.g., Random Forest) for predictive modeling (AVM); and adopting UQ methods (e.g., Conformal Prediction) to evaluate prediction reliability. These issues are critical in creating a complete and trustworthy evaluation framework.

4.1.1. Implications for Value Delivery in Megaproject FEED

The findings have significant implications for improving value delivery during the critical FEED phase. The complex web of factors identified in the FE model (RQ1) empirically supports the expanded definition of 'value' discussed in the literature (Mitoula & Papavasileiou, 2023; Cortés et al., 2023), moving beyond traditional time-cost-scope metrics (Project Management Institute, 2021). It highlights the need for FEED processes to systematically consider and quantify the trade-offs between economic performance, social impacts (literacy, demographics), environmental factors (energy, water stress, coastal protection), and governance quality.

The success of the AVM (RQ2) suggests that data-driven forecasting, incorporating ESG and economic indicators, can provide valuable foresight during FEED, potentially anticipating future performance implications of early design choices. The ability to quantify uncertainty (UQ) is particularly critical in the high-stakes environment of megaprojects, allowing decision-makers to understand the confidence level associated with predictions and make more risk-informed choices (Alamdari et al., 2023). This addresses the identified gap regarding the lack of rigorous analysis for complex trade-offs in the early stages (Rosłon, 2022).

4.2. Contribution to Theoretical Understanding (Institutional Theory, Porter Hypothesis, Regulatory Capture in Megaprojects)

The results offer empirical context to the theoretical frameworks discussed. For Institutional Theory, the significance of the economic_and_social_rights_performance_score in the FE model (

Table 4) aligns with Institutional Theory’s emphasis on how formal and informal rules and their enforcement (‘rule of law’ proxy significance in AVM,

Table 8) shape outcomes (Scott, 2014). The preference for the FE model, which accounts for country-specific unobserved heterogeneity, further underscores the importance of varying institutional contexts (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Ahmed et al., 2024).

Whereas for the Porter Hypothesis, the findings provide nuanced insights rather than straightforward confirmation. The FE model (

Table 4) shows mixed signals; while coastal_protection (potentially reflecting climate adaptation investment) is positive, other environmental indicators like renewable_electricity_output were not significant drivers of within-country house price changes in this specification, and energy use metrics were negatively associated. This suggests that the relationship between environmental regulations/performance and economic outcomes (proxied by house prices) is complex, context-dependent, and may not always align with the ‘strong’ version of the hypothesis (Porter & Van-der-Linde, 1995; Chen et al., 2022; Wu, 2023). The predictive importance of lagged renewable_electricity_output in the AVM (

Table 8) hints at potential delayed or indirect effects requiring further investigation.

Regulatory Capture: While not directly measured, the results implicitly touch upon this. The importance of governance-related variables (economic_and_social_rights., rule_law_estimate_lag1) suggests that the quality and effectiveness of the institutional and regulatory environment – which can be undermined by capture (Stigler, 1971; Hall et al., 2023; Cao & Nie, 2024) – influence the broader economic context within which megaprojects operate and are valued. Ineffective enforcement or biased regulations could distort the relationships observed.

4.3. The Role of Digitalization, PropTech, and FinTech Integration

This research directly addresses the identified gap regarding the underutilization of integrated digital technologies in FEED (Datta et al., 2024). The successful application of panel regression, ML (AVM), and UQ (RQ2, RQ3) provides a proof-of-concept for a computationally enabled framework. It demonstrates how diverse data streams (economic, ESG) can be integrated and analyzed using sophisticated techniques available through libraries like statsmodels, linearmodels, scikit-learn, and mapie (Seabold & Perktold, 2010; Sheppard, 2024; Pedregosa et al., 2011; Taquet et al., 2023).

The findings lay the methodological groundwork for future automated digital tools, potentially integrating BIM (Cassandro et al., 2024; Eastman et al., 2011) as a data hub with advanced analytics. Such platforms could connect project data with broader contextual data (as analyzed) and leverage PropTech/FinTech functionalities for holistic, automated value assessment and optimization during FEED, moving beyond current fragmented solutions (Saleh et al., 2024b; Sharma & Gupta, 2024). The UQ component is vital for building trust in such automated systems.

4.4. Practical Implications for Project Managers, Investors, and Policymakers

For project managers and teams, the study highlights the need to incorporate a broader set of quantifiable ESG and socio-economic indicators into FEED assessments. Relying solely on traditional metrics is insufficient. Adopting data analytics and potentially ML-based predictive tools (with UQ) can enhance decision-making quality and stakeholder alignment (Marnewick et al., 2024).

Whereas for investors and financial institutions, the empirical link (albeit complex) between ESG factors and economic performance proxies, and their predictive power in the AVM, reinforces the financial materiality of ESG considerations in megaprojects (Ahmed et al., 2024; Stylianou et al., 2025). Integrating such quantitative analyses and UQ can improve risk assessment and alignment with sustainable finance goals (Lin et al., 2022).

Ultimately, for policymakers, the results underscore the influence of the broader institutional and regulatory environment on economic outcomes relevant to large investments. Policies strengthening governance (e.g., rule of law, social rights protection) and promoting targeted environmental actions (e.g., climate adaptation like coastal protection) may foster more favorable conditions. The nuanced findings on environmental factors suggest careful design of regulations is needed to achieve desired economic co-benefits (Guan et al., 2023). Promoting data availability and standardization for ESG metrics would also facilitate better analysis.

4.5. Limitations of the Research

Several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the dependent variable, the national house price index, serves as an indirect macro-level proxy for the economic dimension of megaproject value or the context they operate in; findings may not directly map to specific project outcomes. Secondly, the use of country-level aggregate data limits direct applicability to individual project FEED decisions and carries the risk of ecological fallacy. Generalization requires caution. Thirdly, the analysis relies on the availability and quality of data from World Bank and OECD databases, which may have inherent limitations or gaps. Fourthly, the statistical methods identify correlations (panel regression) and predictive associations (AVM), not definitive causal relationships. Fifthly, the findings are specific to the chosen models (VIF-reduced FE, Random Forest); alternative specifications or algorithms might yield different insights. Finally, this study focuses on establishing a methodological foundation rather than developing and validating a ready-to-use software tool.

4.6. Recommendations for Future Research

Building on this work, future research should focus on collecting and analyzing project-level data that includes specific FEED phase decisions, costs, schedules, and multi-dimensional lifecycle value outcomes (economic, social, environmental). Furthermore, future projects should concentrate on developing and validating more comprehensive and direct metrics for megaproject lifecycle value that capture the multi-faceted nature of performance beyond simple proxies. Researchers should explore more sophisticated modeling techniques, including dynamic panel models, causal inference methods (e.g., difference-in-differences if relevant policy changes occur), graph neural networks for stakeholder interactions, and NLP for analyzing textual data from FEED documentation.

Furthermore, future research work should explore designing, building, and validating integrated digital platforms that operationalize the proposed framework, linking BIM, simulation tools, ML/AI analytics, and UQ capabilities for practical FEED decision support. To gain qualitative insights, researchers can conduct in-depth case studies of megaprojects to qualitatively explore the decision-making dynamics, institutional pressures, and practical challenges of implementing value-driven FEED, complementing the quantitative findings. Ultimately, researchers should explore tracking megaprojects over their full lifecycle to assess the long-term validity of predictions made using AVMs and the actual impact of FEED decisions informed by holistic value frameworks.

5. Conclusion

This research tackled the significant challenge of embedding multi-dimensional value considerations into the Front-End Engineering Design (FEED) phase of megaprojects, a stage often hampered by reliance on traditional metrics and a lack of systematic, data-driven evaluation. The study sought to establish a foundation for advanced decision support by quantitatively exploring the links between national-level Economic, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors and economic performance (proxied by house price indices), and by assessing the feasibility of predictive modeling with uncertainty quantification (UQ).

The most critical conclusion drawn from the empirical analysis (

Table 4, Fixed Effects Model) is that a diverse set of quantifiable environmental, social, governance, and economic factors exhibit statistically significant correlations with national house price index variations, even after controlling for fixed country characteristics. This provides strong empirical validation that factors beyond traditional cost-schedule-scope, such as coastal_protection, literacy_rate, economic_and_social_rights_performance, energy_imports/use, and population_ages_65_and_above, are intertwined with macro-economic outcomes relevant to the environments where megaprojects unfold. This finding directly challenges the adequacy of narrow, traditional project evaluation methods and underscores the necessity of adopting a broader, multi-dimensional value perspective early in the project lifecycle.

Furthermore, the successful development of the Automated Valuation Model (AVM) using a Random Forest algorithm demonstrates that machine learning techniques can effectively predict future economic indicator levels (R²=0.87 on test data,

Table 8) using lagged ESG and economic data. Crucially, the reliable quantification of uncertainty associated with these predictions (achieving 90.8% empirical coverage with 90% target intervals via Conformal Prediction,

Table 9) represents a significant advancement. This implies that it is feasible to move beyond purely deterministic forecasts in FEED, providing decision-makers with a more realistic understanding of potential outcomes and associated risks, thereby supporting more robust and defensible choices.

Methodologically, the study concludes that developing a rigorous, integrated framework for value assessment requires a systematic process. This encompasses careful data sourcing and preparation, diligent management of multicollinearity (VIF reduction,

Section 3.2), appropriate statistical and machine learning model selection (justified by diagnostic testing like the Hausman test favouring FE over RE,

Table 7), and the vital implementation of UQ techniques.

These findings extend previous research by providing quantitative, macro-level evidence supporting the integration of ESG factors into economic assessments and by demonstrating a practical application of ML with UQ in this context. They offer nuanced empirical perspectives on theories like the Porter Hypothesis (showing complex, not always positive, links between environmental factors and the economic proxy) and Institutional Theory (highlighting the significance of governance-related variables). The implications are substantial: project managers gain a basis for incorporating broader metrics, investors receive further evidence of ESG materiality, and policymakers see the potential influence of regulatory and social environments on economic performance indicators relevant to large investments (as elaborated in

Section 4.4).

While establishing a valuable methodological proof-of-concept, the conclusions are framed acknowledging the study's limitations, primarily the use of a macro-level proxy (national house price index) rather than direct project value, the aggregate nature of country-level data, and the correlational (not causal) nature of the findings (detailed in

Section 4.5). These limitations highlight the need for future research, as recommended in

Section 4.6, to focus on: applying similar methodologies to granular, project-specific data; developing more direct and comprehensive lifecycle value metrics for megaprojects; and building and validating integrated digital platforms that translate these methods into practical decision-support tools for FEED.

In summary, this research concludes that adopting more holistic, quantitative, and computationally advanced approaches, specifically integrating machine learning and uncertainty quantification, is not only feasible but necessary for advancing value-driven decision-making in the critical FEED phase of megaprojects. It provides essential groundwork for developing next-generation automated systems capable of enhancing stakeholder alignment, improving risk management, and ultimately increasing the likelihood of realizing intended lifecycle value from complex and costly initiatives.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo conceived the study, performed the literature review, conducted the bibliometric analysis, developed the framework, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the faculty of Economics and Business staff for their support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

To promote transparency and enhance reproducibility, the Python script used for the panel regression analysis and an anonymized version of the dataset including the extracted panel data regression results and Automated Valuation Model (AVM) outcomes will be made available as supplementary material on the publisher's website upon publication. This initiative aligns with the journal’s commitment to open science, ensuring ongoing access and supporting future research in this area.

Abbreviations

| AECO |

Architecture, Engineering, Construction, and Operations |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AVM |

Automated Valuation Model |

| BIM |

Building Information Modeling |

| CAPEX |

Capital Expenditures |

| DLT |

Distributed Ledger Technology |

| DSS |

Decision Support Systems |

| ESG |

Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| FE |

Fixed Effects |

| FEED |

Front-End Engineering Design |

| GCPs |

Green Construction Practices |

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

| GPI |

Gender Parity Index |

| HPI |

House Price Index |

| ILO |

International Labour Organization |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| LCA |

Lifecycle Assessment |

| LCCA |

Lifecycle Cost Analysis |

| MCDA |

Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| OECD |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OLS |

Ordinary Least Squares |

| OPEX |

Operational Expenditures |

| PPP |

Purchasing Power Parity |

| RE |

Random Effects |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Squared Error |

| SE |

Standard Error |

| UQ |

Uncertainty Quantification |

| VIF |

Variance Inflation Factor |

| VM |

Value Management |

References

- Adamantiadou, D. S., & Tsironis, L. (2025). Leveraging Artificial Intelligence in project management: A systematic review of applications, challenges, and future directions. Computers, 14(2), 66. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M., Khan, N., & Ayub, M. (2024). Green construction practices and economic performance: The mediating role of social performance and environmental performance. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 20(5), 1396-1406. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S., Dlask, P., Selim, O., & Elhendawi, A. (2018). BIM Performance Improvement Framework for Syrian AEC Companies. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science, 1(1), 21–41. [CrossRef]

- Akcamete, A., & Akinci, B. (2010). Potential Utilization of Building Information Models for Planning Maintenance Activity. Carnegie Mellon University. https://hdl.handle.net/11511/84666.

- Alamdari, A. M., Jabarzadeh, Y., Adams, B., Samson, D., & Khanmohammadi, S. (2023). An analytic network process model to prioritize supply chain risks in green residential megaprojects. Operations Management Research, 16(1), 141–163. [CrossRef]

- Ali, H. E., & Bucher, S. F. (2021). Ecological Impacts of Megaprojects: Species Succession and Functional Composition. Plants, 10(11), 2411. [CrossRef]

- Banawi, A., Aljobaly, O., & Ahiable, C. (2019). A comparative review of building information modeling frameworks. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science, 2(2), 23–48.

- Bashtannyk, V.; et al. (2024). Linear Models for Panel Data. [Software documentation or related paper, check linearmodels docs for appropriate citation].

- Cao, D., & Nie, C. (2024). Effect of government’s environmental attention on corporate philanthropy based on the institutional theory: Evidence from China’s heavily polluting companies. PLoS ONE 19(10), e0309595. [CrossRef]

- Cassandro, J., Mirarchi, C., Gholamzadehmir, M., & Pavan, A. (2024). Advancements and prospects in building information modeling (BIM) for construction: A review. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, (ahead-of-print). [CrossRef]

- Chang, T., Du, Y., Deng, X., & Wang, X. (2024). Impact of cognitive biases on environmental compliance risk perceptions in international construction projects. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1397306. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. P. V., Zhuo, Z., Huang, Z., & Li, W. (2022). Environmental regulation and ESG of SMEs in China: Porter hypothesis re-tested. The Science of the Total Environment, 850, 157967. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M., Chong, H.-Y., & Xu, Y. (2023). Blockchain-smart contracts for sustainable project performance: Bibliometric and content analyses. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26(4), 8159-8182. [CrossRef]

- Cortés, D., Traxler, A. A., & Greiling, D. (2023). Sustainability reporting in the construction industry – Status quo and directions of future research. Heliyon, 9(11), e21682. [CrossRef]

- Datta, S. D., Islam, M., Sobuz, H. R., Ahmed, S., & Kar, M. (2024). Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications in the project lifecycle of the construction industry: A comprehensive review. Heliyon, 10(5), e26888. [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [CrossRef]

- Eastman, C., Teicholz, P., Sacks, R., & Liston, K. (2011). BIM handbook: A guide to building information modeling for owners, managers, designers, engineers and contractors (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [CrossRef]

- Elhendawi, A. I. N. (2018). Methodology for BIM Implementation in KSA in AEC Industry. [CrossRef]

- Elhendawi, A., Omar, H., Elbeltagi, E., & Smith, A. (2019a). A practical approach for paving the way to motivate BIM non-users to adopt BIM. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science, 2(2), 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Elhendawi, A., Smith, A., & Elbeltagi, E. (2019b). Methodology for BIM implementation in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science, 2(1), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Erdede, S. B., & Bektaş, S. (2024). Land management criteria for green building certification systems in Turkey. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 31(24), 35442-35454. [CrossRef]

- Evans, M., Farrell, P., Elbeltagi, E., Mashali, A., & Elhendawi, A. (2020). Influence of partnering agreements associated with BIM adoption on stakeholder's behaviour in construction mega-projects. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science, 3(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2014). What You Should Know About Megaprojects and Why: An Overview. Project Management Journal, 45(2), 6–19. [CrossRef]

- Guan, H., Zhang, Y., & Zhao, A. (2023). Environmental taxes, enterprise innovation, and environmental total factor productivity—Effect test based on Porter’s hypothesis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(44), 99885–99899. [CrossRef]

- Haider, S. A., Tehseen, S., Koay, K. Y., Poulova, P., & Afsar, B. (2024). Impact of project managers emotional intelligence on megaprojects success through the mediating role of human-related agile challenges: Project management as a moderator. Acta Psychologica, 247, 104305. [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. L., Willging, C. E., Aarons, G. A., & Reeder, K. (2023). Site-Level Evidence-Based Practice Accreditation: A Qualitative Exploration Using Institutional Theory. Human Services Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 47(3), 157–175. [CrossRef]

- Hatefi, S. M., Ahmadi, H., & Tamošaitienė, J. (2025). Risk Assessment in Mass Housing Projects Using the Integrated Method of Fuzzy Shannon Entropy and Fuzzy EDAS. Sustainability, 17(2), 528. [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, Y., Xu, J., Zhang, Y., Huang, D., & Chang, J. (2023). Research on the risk transmission mechanism of international construction projects based on complex networks. PLoS ONE, 18(8), e0285497. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M., Ma, J., Mushtaq, Z., Ahmad, N., Yousaf, M. Z., Tarawneh, B., Khan, W., Pushkarna, M., & Zaitsev, I. (2025). Energy efficiency evaluation of construction projects using data envelopment analysis and Tobit regression. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 11444. [CrossRef]

- Jing, P., Sheng, J., Hu, T., Mahmoud, A., Huang, Y., Li, X., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., & Shu, Z. (2023). Emergy-based sustainability evaluation model of hydropower megaproject incorporating the social-economic-ecological losses. Journal of Environmental Management, 344, 118402. [CrossRef]

- Kineber, A. F., Elshaboury, N., Oke, A. E., Aliu, J., Abunada, Z., & Alhusban, M. (2024). Revolutionizing construction: A cutting-edge decision-making model for artificial intelligence implementation in sustainable building projects. Heliyon, 10(17), e37078. [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y., & Liu, K. (2025). Optimization path for construction safety resilience in megaprojects from the perspective of configuration. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, (ahead-of-print), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Laffont, J.-J., & Tirole, J. (1991). The Politics of Government Decision-Making: A Theory of Regulatory Capture. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 1089–1127. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y., Chau, K. Y., Tran, T. K., Sadiq, M., Van, L., & Phan, T. T. H. (2022). Development of renewable energy resources by green finance, volatility and risk: Empirical evidence from China. Renewable Energy, 201, 821–831. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T., Ding, J., Wang, Z., & Skibniewski, M. J. (2020). Governing Government-Project Owner Relationships in Water Megaprojects: A Concession Game Analysis on Allocation of Control Rights. Water Resources Management, 34(13), 4003–4018. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S., Zhang, L., Aslam, S., & Khan, N. (2024). Maximizing the impact of megaprojects: Urgent implications of financial inclusion drive for effective anti-poverty measures. Heliyon, 10(21), e39658. [CrossRef]

- Marnewick, C., Romero-Torres, A., & Delisle, J. (2024). Rich pictures as a research method in project management – A way to engage practitioners. Project Leadership and Society, 5, 100127. [CrossRef]

- Mashali, A., & El-Tantawi, A. (2022). BIM-based stakeholder information exchange (IE) during the planning phase in smart construction megaprojects (SCMPs). International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science, 5(1), 8–19.

- McKinney, W. (2010). Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, 56-61. [CrossRef]

- Mitoula, R., & Papavasileiou, A. (2023). Mega infrastructure projects and their contribution to sustainable development: The case of the Athens Metro. Economic Change and Restructuring, 56(3), 1943–1969. [CrossRef]

- Ngayakamo, B., & Onwualu, A. P. (2022). Recent advances in green processing technologies for valorisation of eggshell waste for sustainable construction materials. Heliyon, 8(6), e09649. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (n.d.). Analytical house price indicators. OECD Data Explorer. Retrieved April 8, 2025, from https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?lc=en&tm=DF_HOUSE_PRICES&pg=0&snb=1&vw=tb&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_AN_HOUSE_PRICES%40DF_HOUSE_PRICES&df[ag]=OECD.ECO.MPD&df[vs]=1.0&pd=2009%2C2024&dq=.A.RHP.IX&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false.

- Onubi, H. O., Yusof, N. A., & Hassan, A. S. (2022). Green construction practices: Ensuring client satisfaction through health and safety performance. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(4), 5431–5444. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F., Varoquaux, G., Gramfort, A., Michel, V., Thirion, B., Grisel, O., & Duchesnay, É. (2011). Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12(Oct), 2825-2830. http://jmlr.org/papers/v12/pedregosa11a.html.

- Peiman, F., Khalilzadeh, M., Shahsavari-Pour, N., & Ravanshadnia, M. (2025). Estimation of building project completion duration using a natural gradient boosting ensemble model and legal and institutional variables. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 32(4), 2069-2104. [CrossRef]

- Peng, X. (2023). Environmental regulation and agricultural green productivity growth in China: A retest based on ‘Porter Hypothesis’. Environmental Technology, 45(16), 3174–3188. [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E., & Van-der-Linde, C. (1995). Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(4), 97–118. [CrossRef]

- Project Management Institute. (2021). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK® guide) (7th ed.). Project Management Institute.

- Reffat, R., Gero, J., & Peng, W. (2004). Using Data Mining on Building Maintenance During the Building Life Cycle. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA 2004) (pp. 91-97).

- Rosłon, J. (2022). Materials and Technology Selection for Construction Projects Supported with the Use of Artificial Intelligence. Materials, 15(4), 1282. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M., Mahmoudi, A., & Deng, X. (2022). Adopting distributed ledger technology for the sustainable construction industry: Evaluating the barriers using Ordinal Priority Approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(7), 10495–10520. [CrossRef]

- Safour, R., Ahmed, S., & Zaarour, B. (2021). BIM Adoption around the World. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science, 4(2), 49–63. [CrossRef]

- Salamah, T., Shibani, A., & Alothman, K. (2022). Improving AEC Project Performance in Syria Through the Integration of Earned Value Management System and Building Information Modelling: A Case Study. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science, 5(1), 74-95. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, F. H., Elhendawi, A., Darwish, A. S., & Farrell, P. (2024a). An ICT-based Framework for Innovative Integration between BIM and Lean Practices Obtaining Smart Sustainable Cities. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science, 7(2) [Check Vol/Issue], 68–75. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, F., Elhendawi, A., Darwish, A. S., & Farrell, P. (2024b). A Framework for Leveraging the Incorporation of AI, BIM, and IoT to Achieve Smart Sustainable Cities. Journal of Intelligent Systems and Internet of Things, 11(2), 75–84. [CrossRef]

- SAVE International. (2007). Value Methodology Standard. https://www.value-eng.org/.

- Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Seabold, S., & Perktold, J. (2010). Statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with Python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, 92-96. [CrossRef]

- Shaban, M. H., & Elhendawi, A. (2018). Building Information Modeling in Syria: Obstacles and Requirements for Implementation. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science, 1(1).

- Shafaay, M., Alqahtani, F. K., Alsharef, A., & Chen, G. (2025). Modeling construction cost overrun risks at the FEED stage for mining projects using PLS-SEM. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, (ahead-of-print), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R., & Gupta, H. (2024). Harmonizing sustainability in industry 5.0 era: Transformative strategies for cleaner production and sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Cleaner Production, 445, 141118. [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, K. (2017-2024). linearmodels: Linear Models for Panel Data. https://bashtage.github.io/linearmodels/.

- Stigler, G. J. (1971). The Theory of Economic Regulation. The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1), 3–21. [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, I., Christofi, M., Karasamani, I., & Magidou, M. (2025). Assessing the transition risks of environmental regulation in the United States: Revisiting the Porter hypothesis. Risk Analysis, (ahead-of-print). [CrossRef]

- Su, W., & Hahn, J. (2023). Psychological Capital and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors of Construction Workers: The Mediating Effect of Prosocial Motivation and the Moderating Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility. Behavioral Sciences, 13(12), 981. [CrossRef]

- Subra, M. Jrad, F. AL, S. (2024). Developing a Model to Improve the Efficiency of Maintenance Management for Service Buildings Using BIM and Power BI: A Case Study. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science, 8(1), 18–30. [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. [CrossRef]

- Sun, R., Liu, Y., & Zhao, J. (2022). Innovation Network Reconfiguration Makes Infrastructure Megaprojects More Resilient. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022, 1727030. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Zhang, R., Yu, Z., Zhu, S., Qie, X., Wu, J., & Li, P. (2024). Revisiting the porter hypothesis within the economy-environment-health framework: Empirical analysis from a multidimensional perspective. Journal of Environmental Management, 349, 119557. [CrossRef]

- Taboada, I., Daneshpajouh, A., Toledo, N., & de Vass, T. (2023). Artificial Intelligence Enabled Project Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Applied Sciences, 13(8), 5014. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., Wang, M., Wang, Q., Zhang, J., Li, H., & Tang, J. (2022). Exploring Technical Decision-Making Risks in Construction Megaprojects Using Grounded Theory and System Dynamics. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022, 9598781. [CrossRef]

- Taquet, T., Angelopoulos, A. N., Bates, S., & Romano, Y. (2023). MAPIE: An open-source library for distribution-free uncertainty quantification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.10570. https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.10570.

- Turban, E., Sharda, R., & Delen, D. (2011). Decision support and business intelligence systems (9th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Van Rossum, G., & Drake Jr, F. L. (1995). Python reference manual. Centrum voor Wiskunde en Informatica Amsterdam.

- Wang, G., Du, Q., Li, X., Deng, X., & Niu, Y. (2023). From ambiguity to transparency: Influence of environmental information disclosure on financial performance in the context of internationalization. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(4), 10226–10244. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zheng, R., & Li, M. (2024). Risk assessment of fire safety in large-scale commercial and high-rise buildings based on intuitionistic fuzzy and social graph. Journal of Building Engineering, 89, 109165. [CrossRef]

- Wijayasekera, S. C., Hussain, S. A., Paudel, A., Paudel, B., Steen, J., Sadiq, R., & Hewage, K. (2022). Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence in the Complex Environment of Megaprojects: Implications for Practitioners and Project Organizing Theory. Project Management Journal, 53(5), 485–500. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (n.d.-b). Environment, Social and Governance Data. World Bank Databank. Retrieved April 8, 2025, from https://databank.worldbank.org/source/environment-social-and-governance?preview=on#.

- Wu, T. (2023). Carbon emissions trading schemes and economic growth: New evidence on the Porter Hypothesis from 285 China's prefecture-level cities. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(43), 96948–96964. [CrossRef]

- Xie, L., Huang, M., Xia, B., & Skitmore, M. (2022). Megaproject Environmentally Responsible Behavior in China: A Test of the Theory of Planned Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6581. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H., Ma, M., Wu, Y., Fan, H., & Dong, C. (2022). Overview and analysis of the text mining applications in the construction industry. Heliyon, 8(12), e12088. [CrossRef]

- Yoshiura, L. J. M., Martins, C. L., Costa, A. P. C. S., & dos Santos-Neto, J. B. S. (2023). A MULTICRITERIA DECISION MODEL FOR RISK MANAGEMENT MATURITY EVALUATION. Pesquisa Operacional, 43, e270186. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S., Chen, H., Ma, H., & Shi, J. J. (2022). Governance of social responsibility in international infrastructure megaprojects. Frontiers of Engineering Management, 9(2), 343–348. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C., Hamzah, H. Z., Yin, J., Wu, D., Cao, J., Mao, X., & Li, H. (2023). Impact of environmental regulations on the industrial eco-efficiency in China—Based on the strong porter hypothesis and the weak porter hypothesis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(15), 44490–44504. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Pooled OLS Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Model Summary.

Table 1.

Pooled OLS Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Model Summary.

| Statistic |

Value |

Statistic |

Value |

| Dep. Variable |

house_price_index |

R-squared |

0.50 |

| Estimator |

PooledOLS |

R-squared (Between) |

0.41 |

| No. Observations |

650 |

R-squared (Within) |

0.53 |

| Cov. Estimator |

Clustered |

R-squared (Overall) |

0.50 |

| Entities |

47 |

Log-likelihood |

-2613.40 |

| Time periods |

14 |

F-statistic (robust) |

49.50 |

| |

|

P-value (F-stat robust) |

0.00 |

Table 2.

Pooled OLS Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Parameter Estimates.

Table 2.

Pooled OLS Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Parameter Estimates.

| Variable |

Parameter |

Std. Err. |

T-stat |

P-value |

Sig. (0.05) |

| Const |

90.47 |

17.49 |

5.17 |

0.00 |

*** |

| coastal_protection |

-0.01 |

0.02 |

-0.44 |

0.66 |

|

| control_corruption_estimate |

-0.82 |

3.48 |

-0.24 |

0.81 |

|

| economic_and_social_rights_performance_score |

-2.49 |

0.80 |

-3.13 |

0.00 |

** |

| electricity_production_from_coal_sources_total |

-0.06 |

0.05 |

-1.09 |

0.27 |

|

| energy_imports_net_energy_use |

-0.01 |

0.01 |

-1.36 |

0.18 |

|

| energy_intensity_level_primary_energy_mj_2017_ppp_gdp |

0.65 |

0.57 |

1.13 |

0.26 |

|

| energy_use_kg_oil_equivalent_per_capita |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

-2.42 |

0.02 |

* |

| fertility_rate_total_births_per_woman |

-3.81 |

2.33 |

-1.63 |

0.10 |

|

| food_production_index_2014_2016_100 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

1.04 |

0.30 |

|

| fossil_fuel_energy_consumption_total |

0.00 |

0.05 |

0.11 |

0.92 |

|

| gdp_growth_annual |

-0.33 |

0.29 |

-1.13 |

0.26 |

|

| gini_index |

-0.26 |

0.10 |

-2.55 |

0.01 |

* |

| government_expenditure_on_education_total_government_expenditure |

-0.22 |

0.22 |

-1.03 |

0.31 |

|

| hospital_beds_per_1_000_people |

-0.51 |

0.39 |

-1.30 |

0.19 |

|

| income_share_held_by_lowest_20 |

0.90 |

0.43 |

2.11 |

0.04 |

* |

| individuals_using_the_internet_population |

-0.12 |

0.06 |

-2.15 |

0.03 |

* |

| land_surface_temperature |

0.10 |

0.13 |

0.75 |

0.45 |

|

| level_water_stress_freshwater_withdrawal_as_a_proportion... |

-0.01 |

0.02 |

-0.93 |

0.35 |

|

| literacy_rate_adult_total_people_ages_15_and_above |

0.02 |

0.02 |

1.30 |

0.19 |

|

| people_using_safely_managed_sanitation_services_population |

-0.02 |

0.08 |

-0.28 |

0.78 |

|

| political_stability_and_absence_violence_terrorism_estimate |

4.76 |

3.25 |

1.47 |

0.14 |

|

| population_ages_65_and_above_total_population |

-0.25 |

0.16 |

-1.51 |

0.13 |

|

| population_density_people_per_sq_km_land_area |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.80 |

0.42 |

|

| proportion_bodies_water_with_good_ambient_water_quality |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.41 |

0.68 |

|

| ratio_female_to_male_labor_force_participation_rate_modeled_ilo... |

0.45 |

0.20 |

2.22 |

0.03 |

* |

| renewable_electricity_output_total_electricity_output |

-0.14 |

0.06 |

-2.42 |

0.02 |

* |

| renewable_energy_consumption_total_final_energy_consumption |

-0.04 |

0.09 |

-0.51 |

0.61 |

|

| research_and_development_expenditure_gdp |

-0.57 |

0.97 |

-0.59 |

0.55 |

|

| school_enrollment_primary_and_secondary_gross_gender_parity_index_gpi |

0.77 |

2.61 |

0.29 |

0.77 |

|

| voice_and_accountability_estimate |

-5.02 |

4.03 |

-1.25 |

0.21 |

|

| Significance Codes: (p<0.1), * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01), *** (p<0.001) |

Table 3.

Fixed Effects (Country) Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Model Summary.

Table 3.

Fixed Effects (Country) Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Model Summary.

| Statistic |

Value |

Statistic |

Value |

| Dep. Variable |

house_price_index |

R-squared |

0.588 |

| Estimator |

PanelOLS |

R-squared (Between) |

-0.348 |

| No. Observations |

650 |

R-squared (Within) |

0.588 |

| Cov. Estimator |

Clustered |

R-squared (Overall) |

-0.327 |

| Entities |

47 |

Log-likelihood |

-2479.400 |

| Time periods |

14 |

F-statistic (robust) |

20.720 |

| |

|

P-value (F-stat robust) |

0.000 |

| |

|

F-test Poolability |

6.334 |

| |

|

P-value Poolability |

0.000 |

Table 4.

Fixed Effects (Country) Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Parameter Estimates.

Table 4.

Fixed Effects (Country) Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Parameter Estimates.

| Variable |

Parameter |

Std. Err. |

T-stat |

P-value |

Sig. (0.05) |

| coastal_protection |

0.05 |

0.03 |

2.09 |

0.04 |

* |

| control_corruption_estimate |

-3.52 |

4.02 |

-0.88 |

0.38 |

|

| economic_and_social_rights_performance_score |

-2.67 |

1.32 |

-2.01 |

0.04 |

* |

| electricity_production_from_coal_sources_total |

-0.02 |

0.08 |

-0.26 |

0.79 |

|

| energy_imports_net_energy_use |

-0.03 |

0.01 |

-2.92 |

0.00 |

** |

| energy_intensity_level_primary_energy_mj_2017_ppp_gdp |

-0.86 |

0.65 |

-1.31 |

0.19 |

|

| energy_use_kg_oil_equivalent_per_capita |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

-2.11 |

0.03 |

* |

| fertility_rate_total_births_per_woman |

-5.80 |

3.84 |

-1.51 |

0.13 |

|

| food_production_index_2014_2016_100 |

0.10 |

0.07 |

1.32 |

0.19 |

|

| fossil_fuel_energy_consumption_total |

-0.02 |

0.06 |

-0.42 |

0.67 |

|

| gdp_growth_annual |

-0.53 |

0.30 |

-1.76 |

0.08 |

. |

| gini_index |

-0.04 |

0.12 |

-0.30 |

0.77 |

|

| government_expenditure_on_education_total_government_expenditure |

-0.27 |

0.21 |

-1.29 |

0.20 |

|

| hospital_beds_per_1_000_people |

-0.11 |

0.63 |

-0.17 |

0.87 |

|

| income_share_held_by_lowest_20 |

0.02 |

0.63 |

0.03 |

0.98 |

|

| individuals_using_the_internet_population |

-0.15 |

0.06 |

-2.67 |

0.01 |

** |

| land_surface_temperature |

0.15 |

0.18 |

0.84 |

0.40 |

|

| level_water_stress_freshwater_withdrawal_as_a_proportion... |

0.03 |

0.02 |

1.92 |

0.06 |

. |

| literacy_rate_adult_total_people_ages_15_and_above |

0.04 |

0.02 |

2.00 |

0.05 |

* |

| political_stability_and_absence_violence_terrorism_estimate |

5.17 |

5.32 |

0.97 |

0.33 |

|

| population_ages_65_and_above_total_population |

-0.70 |

0.31 |

-2.28 |

0.02 |

* |

| population_density_people_per_sq_km_land_area |

0.02 |

0.02 |

1.18 |

0.24 |

|

| proportion_bodies_water_with_good_ambient_water_quality |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.66 |

0.51 |

|

| ratio_female_to_male_labor_force_participation_rate_modeled_ilo... |

-0.00 |

0.86 |

-0.01 |

1.00 |

|

| renewable_electricity_output_total_electricity_output |

-0.13 |

0.08 |

-1.56 |

0.12 |

|

| renewable_energy_consumption_total_final_energy_consumption |

0.14 |

0.12 |

1.19 |

0.23 |

|

| research_and_development_expenditure_gdp |

1.01 |

1.48 |

0.69 |

0.49 |

|

| school_enrollment_primary_and_secondary_gross_gender_parity_index_gpi |

1.43 |

2.73 |

0.53 |

0.60 |

|

| voice_and_accountability_estimate |

3.12 |

5.64 |

0.55 |

0.58 |

|

| Significance Codes: (p<0.1), * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01), *** (p<0.001) |

Table 5.

Random Effects Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Model Summary.

Table 5.

Random Effects Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Model Summary.

| Statistic |

Value |

Statistic |

Value |

| Dep. Variable |

house_price_index |

R-squared |

0.959 |

| Estimator |

RandomEffects |

R-squared (Between) |

0.990 |

| No. Observations |

650 |

R-squared (Within) |

0.541 |

| Cov. Estimator |

Clustered |

R-squared (Overall) |

0.980 |

| Entities |

47 |

Log-likelihood |

-2594.600 |

| Time periods |

14 |

F-statistic (robust) |

1501.900 |

| |

|

P-value (F-stat robust) |

0.000 |

Table 6.

Random Effects Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Parameter Estimates.

Table 6.

Random Effects Results (VIF-Reduced, Clustered SE) - Parameter Estimates.

| Variable |

Parameter |

Std. Err. |

T-stat |

P-value |

Sig. (0.05) |

| Const |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

| coastal_protection |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.64 |

0.52 |

|

| control_corruption_estimate |

-6.26 |

3.36 |

-1.86 |

0.06 |

. |

| economic_and_social_rights_performance_score |

-2.26 |

1.23 |

-1.84 |

0.07 |

. |

| electricity_production_from_coal_sources_total |

-0.09 |

0.06 |

-1.38 |

0.17 |

|

| energy_imports_net_energy_use |

-0.01 |

0.01 |

-1.57 |

0.12 |

|

| energy_intensity_level_primary_energy_mj_2017_ppp_gdp |

-0.16 |

0.51 |

-0.32 |

0.75 |

|

| energy_use_kg_oil_equivalent_per_capita |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

-2.43 |

0.02 |

* |

| fertility_rate_total_births_per_woman |

-3.17 |

2.62 |

-1.21 |

0.23 |

|

| food_production_index_2014_2016_100 |

0.21 |

0.08 |

2.76 |

0.01 |

** |