1. Introduction

Earth as a construction material offers significant advantages, including its widespread availability, cost-effectiveness, versatility, low environmental footprint, minimal heat transfer and high heat storage capacity [

1,

2,

3]. Due to these properties, earth has been one of the most widely used building materials throughout human history.

Among the known earth construction techniques, the most widely used method worldwide is Rammed Earth (RE) [

4,

5]. This technique involves the systematic compaction, using a manual or pneumatic rammer, of a soil-water mixture into layers [

6,

7,

8,

9]. The traditional form of RE, known as unstabilized RE, relies solely on soil and water as construction materials, with clay acting as the natural binder. The fact that clay is the only binding material makes the Particle Size Distribution (PSD), as well as the type and amount of clay present in the soil, crucial factors in assessing the suitability of a soil for RE building [

9]. Despite this, there are no standardized regulations defining the specific types of soil that can be used for RE building. Instead, researchers often rely on recommendations such as those proposed by Houben et al. [

9]. Houben et al. suggested PSD zones that are frequently referenced in RE literature; however, these zones should not be considered as strict rules, as practical experience has shown that soils outside these recommended zones have still performed well in practice, while some that met the criteria have not [

10,

11,

12]. In some cases, the reason for not achieving the desired properties is related to the clay content or type. In this situation it is common practice to stabilize the mix adding a material that can act as a supplementary binder to enhance its performance, resulting in what is known as Stabilized Rammed Earth (SRE). Various researchers have also observed that modifying the soil’s PSD by adding other granulometric materials can enhance the properties of the soil in SRE building [

13,

14,

15]. This is particularly relevant as it allows for the use of mining by-products to adjust the soil’s PSD, as has been done in other construction methods [

16,

17,

18]. In this way, large quantities of mining by-products or waste, which currently end up in landfills, could be valorized. In fact, the mining industry is one of the largest contributors to global waste production [

19], generating approximately 100 billion tons per year worldwide [

20]. In the European Union, waste from this industry accounts for around 22.7% of the total waste generated [

21]. Therefore, finding a practical application for these by-products is of significant interest, in order to develop sustainable solutions that preserve a healthy environment [

22].

Thus, in this research, different mining by-products were used to modify the PSD of a soil to evaluate their potential in SRE building. A laboratory experimental campaign was conducted, in which three different mixes were manufactured (a mix composed entirely of a clayey soil, a mix consisted of mining by-products and clayey soil and a mix entirely based on mining by-products), along with specimens of both unstabilized and stabilized mixes using two cement dosages (2.5% and 5%). The testing methodology was carry out following the new methodology to characterize SRE materials explained in [

23].The Standard Proctor (SP) test was employed to determine the Optimal Moisture Content (OMC) of each combination. The Unconfined Compressive Strength (UCS) test was conducted at 7, 28, and 90 days to study the evolution of the mechanical properties of the mixes. To assess the durability of the combinations, two different durability tests were performed: a UCS test at 28 days under soaked conditions to analyze the sensitivity of the mixes to liquid water, and a wetting and drying test at 28 days to determine the non-erosion capability of the combinations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

In the present study, three different soil mixtures were used. The first (M1) was composed entirely of a clayey soil found in Pamplona (Spain). The second mixture (M2) consisted of a blend of this clayey soil combined with three different gravel and sand size by-products to enhance the dry density achieved by the mixture. The by-products employed were the following: a gravel (<12 mm) and a sandy gravel (<4 mm) calcium carbonate that came from the mining of magnesium carbonate rock for refractory material manufacturing and a sand (<1 mm) that was a foundry-recycled sand. Based on a previous study [

24], the mixture was composed 17.9% gravel, 26.4% sandy gravel, 31.8% sand and 23.9% clayey soil. The third mixture (M3) was composed entirely of by-products, maintaining the same proportion of by-products as in mixture 2, but with the clayey soil replaced by another by-product, which had the role of fines. These fines by-products were composed by sludges from the cleaning process of the magnesium carbonate extracted in the magnesite mine.

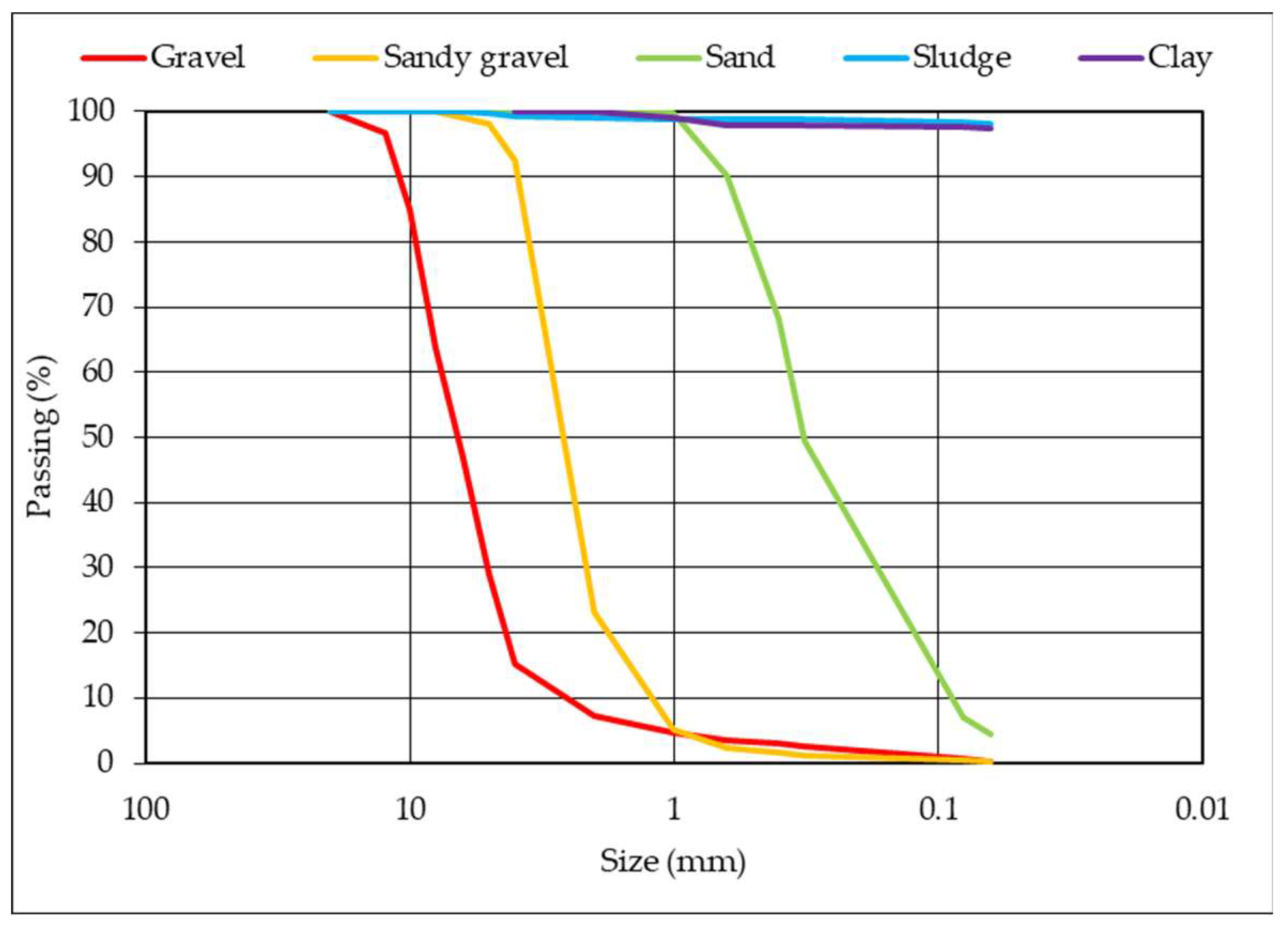

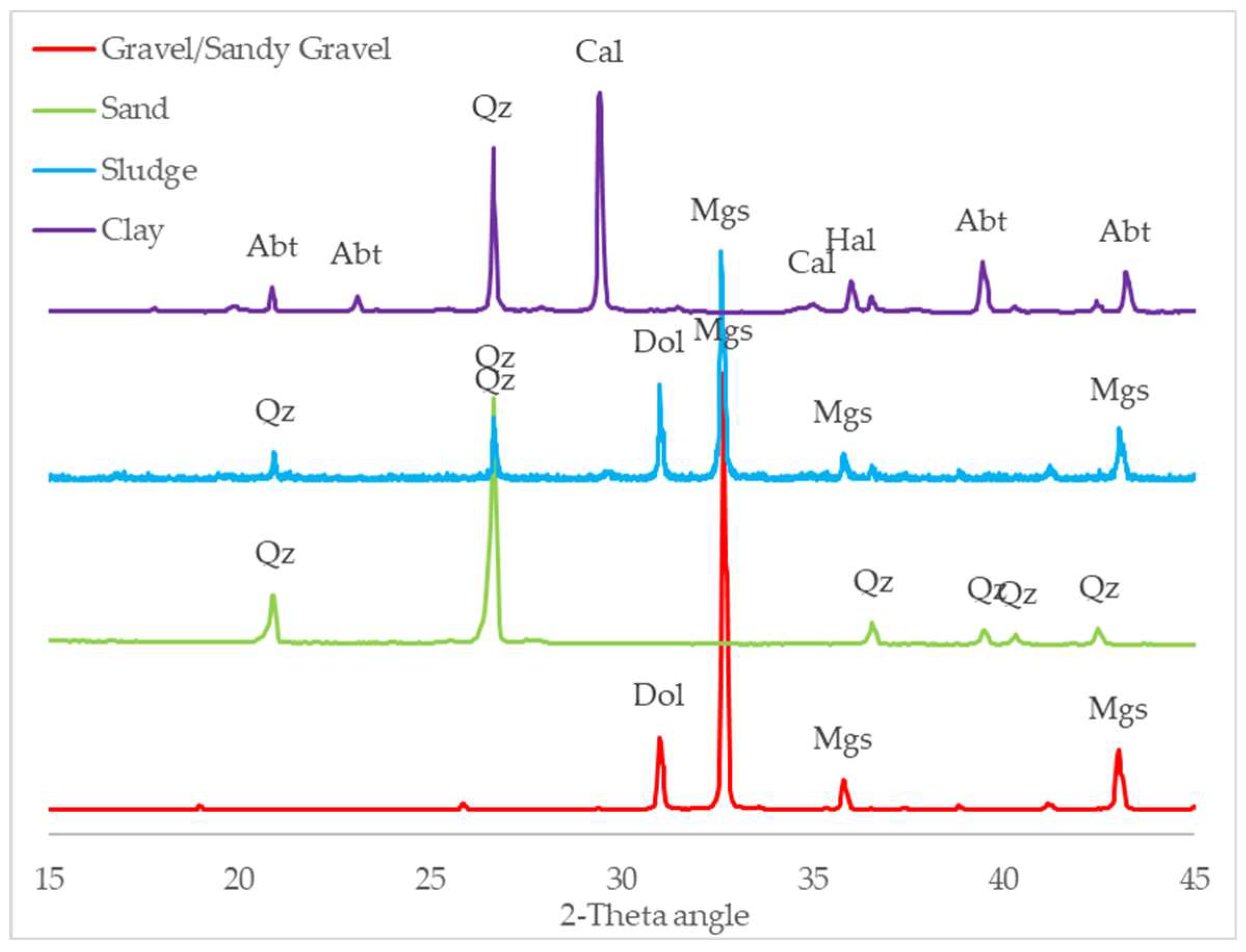

Figure 1 shows the PSD of the materials and

Figure 2 shows the mineralogy obtained by XRD for the considered materials.

Table 1 summarizes of the PSD (in accordance with UNE-EN 933-1:2012 [

25]), bulk density (in accordance with UNE-EN 1097-3:1999 [

26]), and mineralogy obtained by XRD for the materials considered. More detailed information regarding these materials can be found in the articles [

24,

27].

Table 2 shows the Liquid Limit (LL), Plastic Limit (PL), and Plasticity Index (PI) of the sludge and the clayey soil, as well as their Unified Soil Classification System (USCS) classification.

The cement (CEM) used in this study was produced in compliance with the standard UNE-EN 197-1:2011 [

28] and marketed under the trade name CEM-II-BL-32.5-R.

Table 3 provides the bulk density (in accordance with UNE-EN 459-2 [

29]) and a summary of the chemical properties of CEM.

2.2. Methods

Samples of the mixtures were manufactured both unstabilized and stabilized with CEM at two different dosages: 2.5% and 5% by mass, as they are the two most commonly used dosages in SRE [

23]. The combinations were identified as follows: first, the type of mixture used (M1, M2 or M3) was indicated, followed by the amount of CEM added in each case. “C0” was used when no CEM was added, “C2.5” when stabilized with 2.5% CEM, and “C5” when 5% CEM was used.

Table 4 shows the identification of the combinations, the mixture composition and the stabilizer dosage.

The manufacturing, curing, and testing conditions were carried out following the new methodology to characterize SRE materials explained in [

23].

The samples were prepared as follows. First, impurities in the sand were removed by passing it through a 1 mm sieve, discarding any material retained. All materials were then oven-dried at 60°C until they reached a constant weight (i.e., less than 0.1% of mass variation). Next, the mixing process was carried out. This step was not necessary for mix M1, but for mixes M2 and M3, the required amounts of each material were weighed in their dry state and mixed for one minute until homogenized. Afterward, water was added according to the OMC of each combination. The OMC was determined by performing the SP test on each mixture following the UNE 103500:1994 Standard [

30], test, and the results are presented in

Section 3.1. Once water was added, the mix was blended for five minutes to ensure complete homogenization. The homogeneous mixture was then compacted in three layers using a 2.5 kg manual rammer with a 102 mm diameter in a 122 mm high mold (the same mold and rammer used in the SP test). After demolding, the specimens were wrapped in plastic to prevent dehydration and ensure proper cement hydration. Before each test, the specimens were dried in an oven at 60°C until they reached a constant weight (i.e., less than 0.1% of mass variation) to homogenize their moisture content.

The UCS test was performed to three samples of all combinations at 7, 28, and 90 days, following UNE-EN 13286-41:2022 standard [

31]. Durability against environmental exposure was assessed by conducting the soaked UCS test at 28 days to three samples of each combination. This test involved curing the specimens, drying them in an oven at 60°C, immersing them in water for 24 hours, and then testing them for UCS under the same standard used for dry conditions. Durability against erosion was evaluated using the wetting and drying test according to standard ASTM D559M [

32], which was conducted on two specimens for each combination at 28 days. This standard consists of 12 cycles, in which the specimens undergo 5 hours of water immersion, 41 hours of oven drying, and 26 brush strokes per cycle.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimal Moisture Content

Table 5 shows the OMC and the Maximum Dry Density (MDD) achieved by all the combinations during the SP test.

In

Table 5, an indirect relationship between MDD and CEM dosage was observed, along with a direct relationship between OMC and CEM dosage. This was related to the fact that an increase in the cement content in the mix led to an increase in the fines of the sample, resulting in a higher content of material with a lower bulk density than the aggregates and leading to a lower MDD. The increase in the OMC was due to the fact that a higher content of cementitious material increased the amount of fine materials, requiring a greater amount of water to hydrate these fines and reach the OMC. Additionally, the inclusion of mining by-products increased the MDD of the mixtures, as M2C0 achieved a significantly higher MDD compared to M1C0. This was due to the higher bulk density of the added mining by-products compared to the clayey soil, which directly increased the overall density.

3.2. Unconfined Compressive Strength

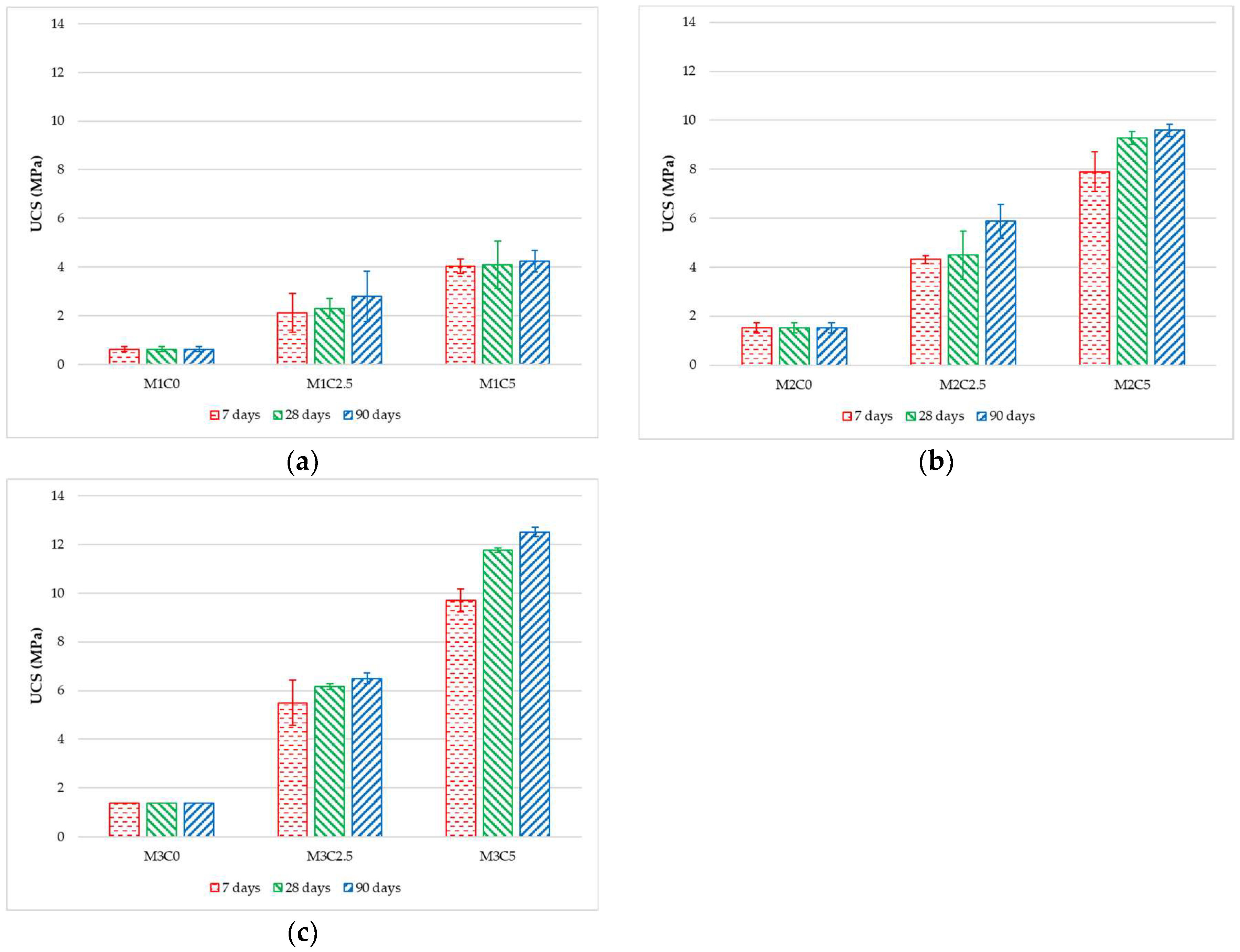

Figure 3 shows the UCS values obtained by the tested combinations at 7, 28 and 90 days on three replicates (standard deviation are provided on the curves).

The unstabilized samples achieved the same UCS values at all ages as no chemical reactions occurred in the unstabilized combinations. M1C0, M2C0 and M3C0 achieved 0.6 MPa, 1.5 MPa and 1.4 MPa, respectively. The results obtained by M1C0 were similar to those reported by Vikas et al. [

10] for clayey soil. However, Ngo et al. [

11] achieved higher values (1.6 MPa) with clayey soil. The values obtained by Ngo et al. [

11] were reached by M2C0, which demonstrated that adding by-products to the clayey soil improved the UCS values. In fact, M2C0 showed an improvement of 250% compared to the mixture without by-products (M1C0). Additionally, the clayey soil contributed to greater cohesion in the mix, as combination M2C0 achieved a higher UCS value than combination M3C0.

In the CEM-stabilized specimens, a direct relationship was observed between UCS values and CEM dosage. This was related to the fact that a higher cement dosage allows for the generation of a greater amount of cementitious gels, and therefore, stronger specimens are obtained [

33]. Additionally, a direct relationship was found between UCS values and curing time, with a generally faster increase in UCS between days 7 and 28 compared to the period between days 28 and 90. This was related to the rapid hydration of the cement to generate hydration products. in accordance with the literature [

11,

34]. M1C2.5 achieved 2.1 MPa, 2.3 MPa and 2.8 MPa at 7, 28 and 90 days, improving the UCS value of the unstabilized M1 mix (M1C0) by 383% at 28 days and were in accordance with the literature [

12,

34]. The improvement in combination M3C5 was greater, achieving UCS values of 4 MPa, 4.1 MPa and 4.2 MPa at 7, 28 and 90 days respectively, which represented a 700% increase compared to the values of M1C0 at 28 days. These values were consistent with the literature, where similar UCS values are reported for cement-stabilized SRE samples [

12,

34,

35]. The UCS values obtained for combinations M1C2.5 and M1C5 exceeded the typical requirements found in the literature, which are between 1.3 MPa and 2 MPa [

9,

36].

Combination M2C2.5 achieved 4.3 MPa, 4.5 MPa and 5.9 MPa at 7, 28 and 90 days respectively, improving the UCS values of M2C0 by 300% at 28 days. Similarly, M3C5 reached 7.9 MPa, 9.3 MPa and 9.6 MPa at 7, 28 and 90 days respectively, representing a 620% improvement over M2C0 at 28 days. Additionally, both combinations M2C2.5 and M2C5 outperformed combinations M1C2.5 and M1C5 at 28 days by 196% and 227% respectively. This demonstrated that the addition of by-products with gravel and sand sized PSD to a clayey soil enhanced the UCS of the SRE mixtures. As cement generated Calcium Silicate Hydrate gels, these gels were capable of binding the by-product aggregates, resulting in a stronger specimen than if only clay were used [

23,

24]. Both combinations M2C2.5 and M2C5 achieved higher values than those reported in previous studies [

12,

34,

35]. This was attributed to the fact that the soil had not been improved in those studies, whereas in the case of Mixture 2, the clayey soil was modified by adding by-products that modified and enhanced the mix’s properties.

Combination M3C2.5 achieved 5.5 MPa, 6.2 MPa and 6.5 MPa at 7, 28 and 90 days respectively, improving by 443% over combination M3C0 at 28 days. The combination M3C5 reached 9.7 MPa, 11.8 MPa and 12.5 MPa at 7, 28 and 90 days, respectively, representing an 842% increase over M3C0 at 28 days. These two combinations achieved the highest UCS values for the same cement dosage and curing age of the present study. The combination M3C2.5 outperformed combination M1C2.5 by 269% at 28 days and combination M2C2.5 by 137% at 28 days. Similarly, combination M3C5 exceeded the UCS values of combinations M1C5 and M2C5 by 288% and 126% at 28 days respectively. These results demonstrated that, although M2 mixture initially showed higher UCS values than M1 (since in the unstabilized samples the clayey soil provided more cohesion than the sludge), once stabilized with cement, the sludge exhibited superior compressive performance. This highlights the potential of the by-products in SRE building, as a mixture completely based on by-products obtained the highest UCS results in this study.

3.3. Soaked Unconfined Compressive Strength

During the soaked UCS test, all unstabilized samples lost their integrity during the immersion in water, which was consistent with observations reported in the literature [

10,

14,

37]. This loss of integrity was attributed to the limited ability of both the clayey soil and the sludge to maintain the cohesion of the sample.

Figure 4 shows M3C0 sample losing its cohesion during water immersion.

M1C2.5 and M2C5 also lost their integrity when submerged in water, whereas M2C2.5, M2C5, M3C2.5 and M3C5 maintained their structural integrity. This difference was due to the fact that in mixtures containing M1, which consisted solely of clayey soil, the CEM was unable to establish strong bonds between the soil particles, leading to a loss of integrity when exposed to water. In contrast, the inclusion of gravel and sand-sized by-products in M2 and M3 enabled the CEM to bind these coarser particles together, creating a more durable matrix that could withstand water exposure and maintain its integrity.

Table 6 shows the results obtained for M2C2.5, M2C5, M3C2.5 and M3C5 combinations in the soaked UCS test. The results for combinations M1C0, M1C2.5, M1C5, M2C0 and M3C0 are not presented, as these combinations lost their integrity and no data could be recorded.

M2C2.5 and M2C5 achieved 0.9 MPa and 1.8 MPa at the soaked UCS values at 28 days. The soaked UCS/dry UCS ratio obtained for these two combinations was 0.21 and 0.20, demonstrating a significant reduction in the UCS after water immersion. However, the values obtained were better than those reported by Vikas et al. [

10], who observed a complete loss of integrity in their specimens stabilized with 2% of CEM. They also noted an improvement in the ratio when increasing the CEM content to 4% and 6%, achieving ratios of 0.24 and 0.47 respectively. Nevertheless, the ratio obtained by M2C2.5 and M2C5 remained below the 0.33 threshold suggested by Heathcote [

38], meaning these combinations would not meet the desired requirements. However, an improvement in M2 compared to M1 was observed, attributed to the use of by-products that allowed CEM to develop cementitious gels that bound these aggregates, forming stronger specimens.

Combinations M3C2.5 and M3C5 achieved ratios of 0.26 and 0.40, respectively. While the combination M3C2.5 did not meet Heathcote’s requirements, combination M3C5 did. Moreover, both combinations achieved higher ratios than M2 with the same CEM dosages. This demonstrated that a mix composed entirely of by-products performs better against water exposure than a clayey soil and a clayey soil mix improved with by-products.

3.4. Wetting and Drying

In this test, the samples also had to be submerged in water, so all combinations that lost their integrity in the soaked UCS test also failed to maintain their integrity in this test.

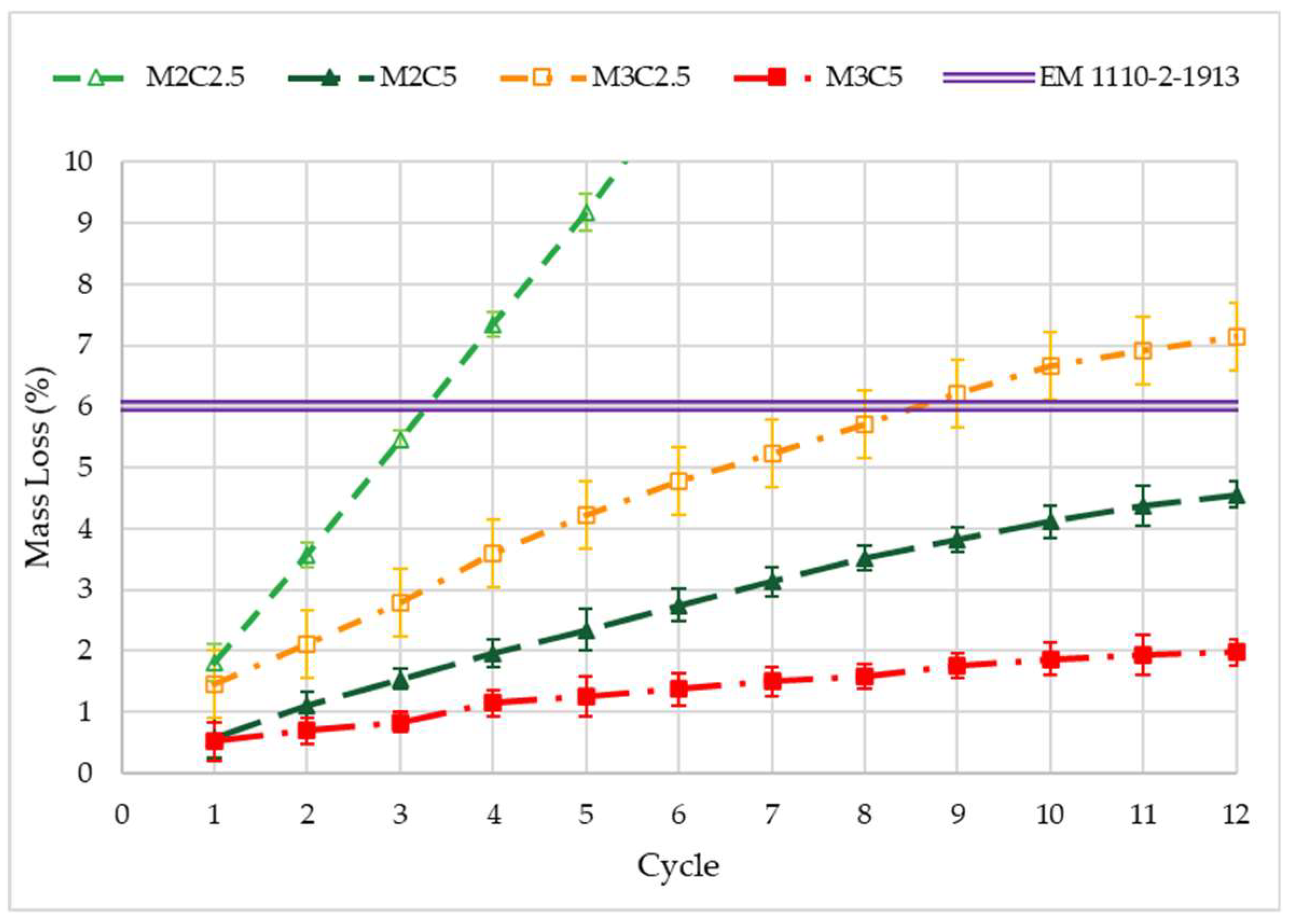

Figure 5 illustrates the mass loss experienced by combinations M2C2.5, M2C5, M3C2.5 and M3C5 over the 12 cycles of wetting and drying at 28 days.

As shown in

Figure 5, M2C2.5 and M2C5 experienced significant mass loss during the initial cycles. In fact, by cycle 6, the mass loss of M2C2.5 had already reached more than 10%, leading to the decision to stop further cycles, as the degradation was excessive. Combinations M2C5, M3C2.5 and M3C5 experienced mass losses of 4.6%, 7.1% and 2%, respectively. For this test, EM 1110-2-1913 [

39] suggests a maximum allowable mass loss of 6%. Therefore, the combination M3C2.5 did not meet this requirement, whereas combinations M2C5 and M3C5 did. These results align with the findings of Mustafa et al. [

37], who observed that at low cement contents, the maximum mass loss requirements were not met, but with higher cement dosages, compliance was achieved. Similar conclusions were drawn by Zami et al. [

12], who observed a reduction in weight loss as the cement content increased.

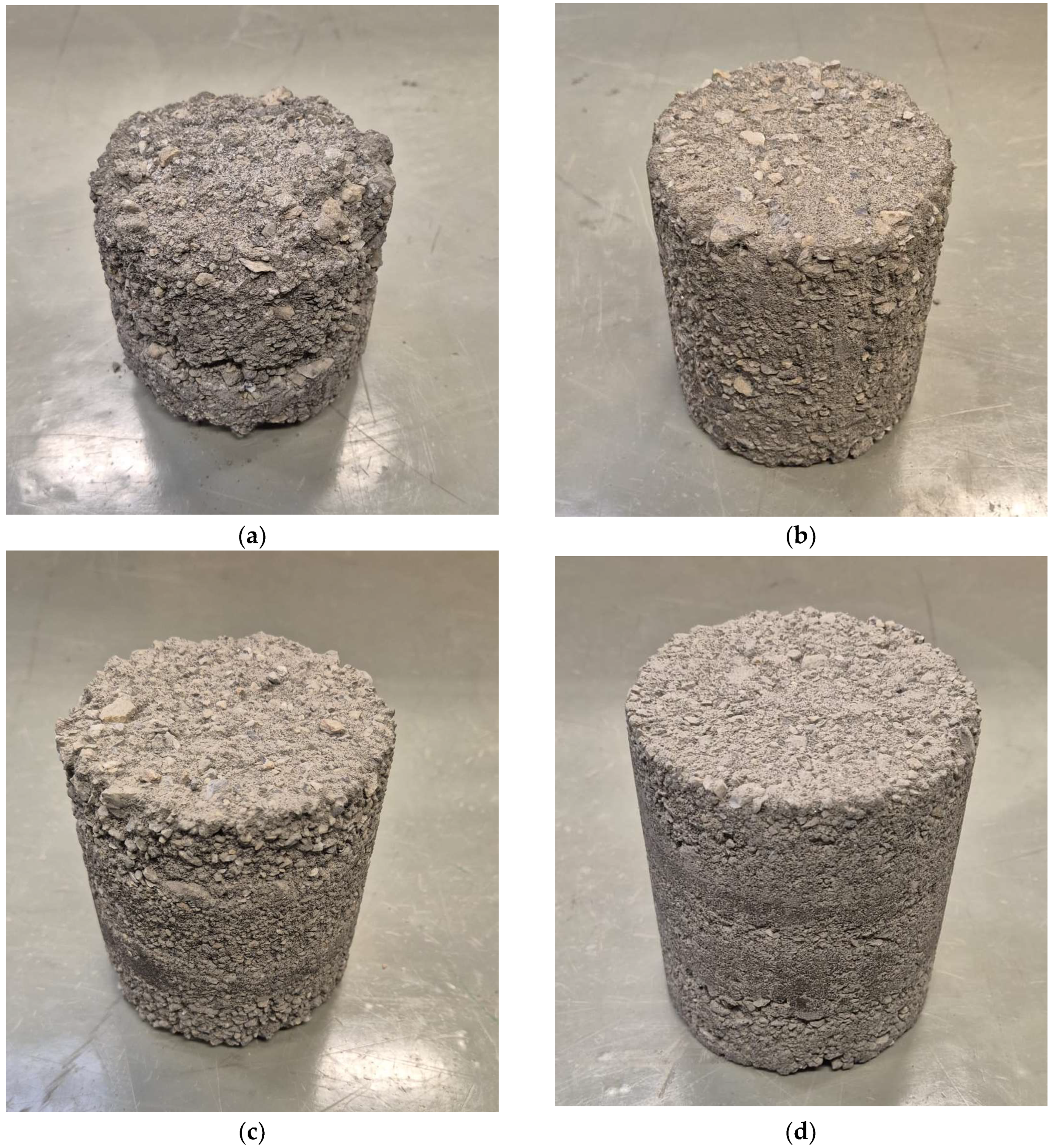

Figure 6 presents the condition of specimens from combinations M2C2.5, M2C5, M3C2.5 and M3C5 after 6 cycles for M2C2.5, and 12 cycles for M2C5, M3C2.5 and M3C5.

As observed in

Figure 6, M2C2.5 suffered a huge loss of mass after the 6th cycle, which is further evidenced by the mass loss shown in

Figure 5. However, specimens M2C5, M3C2.5 and M3C5 maintained their structural integrity. The final condition of the samples also revealed that sample M3C2.5 experienced greater mass loss than M2C5 and M3C5, as a higher presence of coarser particles was observed on the surface of M3C2.5 compared to M2C5 and M3C5. This suggests that M3C2.5 experienced a substantial loss of fines due to the wetting and drying cycles, which exposed the coarser particles. In contrast, the cementitious gels formed in M2C5 and M3C5 successfully preserved the integrity of the fines within the sample, enhancing its resistance to mass loss during the cycles and offering better protection to the coarser particles from the test’s effects.

4. Conclusions

In this study, different granulometric mining by-products were used to modify the PSD of a clayey soil and to evaluate their potential in SRE building. Along with this research the following conclusions were obtained:

Both curing time and CEM dosage had a direct correlation with the improvement of UCS. Mining by-products demonstrated significant potential in SRE building, as their addition to the clayey soil resulted in higher UCS values compared to the UCS obtained from clayey soil alone. Moreover, the mix composed entirely of mining by-products achieved the highest UCS values.

Unstabilized samples lost their integrity during exposure to water. CEM stabilization proved to be an effective solution for enhancing the water resistance of the mixes. The inclusion of mining by-products also showed its potential, as although the mixes did not fully meet the requirements of the soaked UCS and the wetting and drying tests, the mix containing both mining by-products and clayey soil retained its integrity in water, unlike the samples composed solely of clayey soil. M3C5 successfully met the requirements of the soaked UCS and the wetting and drying tests, further highlighting the great potential of mining by-products in SRE building.

This study highlights the potential of mining by-products for use in SRE building. These by-products exhibited excellent performance, as a mix entirely composed of mining by-products, combined with 5% CEM, met all the established requirements. Additionally, they proved beneficial in enhancing the properties of a local soil. Further research would be valuable to explore the use of different stabilizers in combination with these by-products. It would also be very interesting to carry out a cost-benefit or carbon footprint calculation of this material in order to assess its advantages in the building sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.M.-A., C.P. and A.S.; methodology, P.V., R.A. and A.S; validation, C.P. and A.S.; formal analysis, M.A.M.-A. and R.A.; investigation, M.A.M.-A.; data curation, M.A.M.-A. and P.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.M.-A., P.V. and R.A.; writing—review and editing, C.P. and A.S.; visualization, M.A.M.-A., C.P. and A.S.; supervision, C.P. and A.S.; project administration, P.V.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Universidad Pública de Navarra via a doctoral grant to Miguel A. Martin-Antunes (1204/2022) in collaboration with Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CEM |

Cement |

| LL |

Liquid Limit |

| MDD |

Maximum Dry Density |

| OMC |

Optimal Moisture Content |

| PI |

Plastic Index |

| PL |

Plastic Limit |

| PSD |

Particle Size Distribution |

| RE |

Rammed Earth |

| SP |

Standard Proctor |

| SRE |

Stabilized Rammed Earth |

| UCS |

Unconfined Compressive Strength |

| USCS |

Unified Soil Classification System |

References

- Soudani, L.; Fabbri, A.; Morel, J.-C.; Woloszyn, M.; Chabriac, P.-A.; Wong, H.; Grillet, A.-C. Assessment of the Validity of Some Common Assumptions in Hygrothermal Modeling of Earth Based Materials. Energy and Buildings 2016, 116, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Fuller, R.J.; Luther, M.B. Energy Use and Thermal Comfort in a Rammed Earth Office Building. Energy and Buildings 2008, 40, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, J.C.; Mesbah, A.; Oggero, M.; Walker, P. Building Houses with Local Materials: Means to Drastically Reduce the Environmental Impact of Construction. Building and Environment 2001, 36, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arto, I.; Gallego, R.; Cifuentes, H.; Puertas, E.; Gutiérrez-Carrillo, M.L. Fracture Behavior of Rammed Earth in Historic Buildings. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 289, 123167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, S. Recommendations for the Selection, Stabilization, and Compaction of Soil for Rammed Earth Wall Construction. Journal of Green Building 2010, 5, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, D. Recognition of a Heritage in Danger: Rammed-Earth Architecture in Lyon City, France. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 143, 012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nabouch, R.; Bui, Q.-B.; Plé, O.; Perrotin, P. Assessing the In-Plane Seismic Performance of Rammed Earth Walls by Using Horizontal Loading Tests. Engineering Structures 2017, 145, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowamooz, H.; Chazallon, C. Finite Element Modelling of a Rammed Earth Wall. Construction and Building Materials 2011, 25, 2112–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

H. Houben, H. Guillaud, CRAterre, Intermediate Technology Publications, Earth Construction: A Comprehensive Guide, Intermediate Technology Publications, London, UK, 1994. .

- Vikas, K.; Ramana Murthy, V.; Ramana, G.V. Stabilized Soil as a Sustainable Construction Material Using the Rammed Earth Technique; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2023; Vol. 298, p. 281; ISBN 23662557 (ISSN); 9789811967733 (ISBN).

- Ngo, T.; Phan, V.; Schwede, D.; Nguyen, D.; Bui, Q. Assessing Influences of Different Factors on the Compressive Strength of Geopolymer-Stabilised Compacted Earth. JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALIAN CERAMIC SOCIETY 2022, 58, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zami, M.; Ewebajo, A.; Al-Amoudi, O.; Al-Osta, M.; Mustafa, Y. Compressive Strength and Wetting-Drying Cycles of Al-Hofuf “Hamrah” Soil Stabilized with Cement and Lime. ARABIAN JOURNAL FOR SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING 2022, 47, 13249–13264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosicki, L.; Narloch, P. Studies on the Ageing of Cement Stabilized Rammed Earth Material in Different Exposure Conditions. MATERIALS 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, A.N.; Kumar, P.P.; Reddy, M.H. Experimental Study on Long-Term Strength and Performance of Rammed Earth Stabilized with Mineral Admixtures. El-Cezeri J. Sci. and Eng. 2022, 9, 1136–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raavi, S.; Dulal, D. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity and Statistical Analysis for Predicting and Evaluating the Properties of Rammed Earth with Natural and Brick Aggregates. CONSTRUCTION AND BUILDING MATERIALS 2021, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segui, P.; Safhi, A.E.M.; Amrani, M.; Benzaazoua, M. Mining Wastes as Road Construction Material: A Review. Minerals 2023, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, T.; Dong, Z.; Tian, Z. Utilization of Iron Tailings as Aggregates in Paving Asphalt Mixture: A Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Solution for Mining Waste. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 375, 134126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstoy, A.; Lesovik, V.; Fediuk, R.; Amran, M.; Gunasekaran, M.; Vatin, N.; Vasilev, Y. Production of Greener High-Strength Concrete Using Russian Quartz Sandstone Mine Waste Aggregates. Materials 2020, 13, 5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; García-Gómez, J.J.; Velasco-Muñoz, J.F.; Carretero-Gómez, A. Mining Waste and Its Sustainable Management: Advances in Worldwide Research. Minerals 2018, 8, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebi-Khorami, M.; Edraki, M.; Corder, G.; Golev, A. Re-Thinking Mining Waste through an Integrative Approach Led by Circular Economy Aspirations. Minerals 2019, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostats, Waste Statistics, Total Waste Gener. (2021). Https://Ec.Europa.Eu/Eurost at/Statistics-Explained/Index.Php?title=Waste_statistics#Total_waste_generation.

- Jiang, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Li, N.; Wang, W. Flexural Behavior Evaluation and Energy Dissipation Mechanisms of Modified Iron Tailings Powder Incorporating Cement and Fibers Subjected to Freeze-Thaw Cycles. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 351, 131527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Antunes, M.A.; Perlot, C.; Espuelas, S.; Marcelino, S.; Seco, A. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN STABILIZED RAMMED EARTH: TESTING PROTOCOLS AND THE RECOMMENDATIONS FOR STANDARDIZATION. Journal of Building Engineering 2025, 112436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Antunes, M.A.; Prieto, E.; Garcia, B.; Perlot, C.; Seco, A. A Methodology to Optimize Natural By-Product Mixes for Rammed Earth Construction Based on the Taguchi Method. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR) UNE-EN 933-1:2012; Ensayos Para Determinar Las Propiedades Geométricas de Los Áridos. Parte 1: Determinación de La Granulometría de Las Partículas. Método Del Tamizado.; Madrid, España, 2012.

- Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR) UNE-EN 1097-3:1999; Ensayos Para Determinar Las Propiedades Mecánicas y Físicas de Los Áridos. Parte 3: Determinación de La Densidad Aparente y La Porosidad; Madrid, España, 1999.

- Seco, A.; Del Castillo, J.M.; Espuelas, S.; Marcelino-Sadaba, S.; Garcia, B. Stabilization of a Clay Soil Using Cementing Material from Spent Refractories and Ground-Granulated Blast Furnace Slag. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR) UNE-EN 197-1:2011; Cemento. Parte 1: Composición, Especificaciones y Criterios de Conformidad de Los Cementos Comunes; Madrid, España, 2011.

- Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR) UNE-EN 459-2:2022; Cales Para La Construcción. Parte 2: Métodos de Ensayo; Madrid, España, 2022.

- Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR) UNE 103500:1994. Geotecnia. Ensayo de Compactación. Proctor Normal.; Madrid, España, 1994.

- Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR) UNE-EN 13286-41:2022. Mezclas de Áridos Sin Ligante y Con Conglomerante Hidráulico. Parte 41: Método de Ensayo Para La Determinación de La Resistencia a Compresión de Las Mezclas de Áridos Con Conglomerante Hidráulico.; Madrid, España, 2022.

- ASTM International ASTM D559/D559M-15. Standard Test Methods for Wetting and Drying Compacted Soil-Cement Mixtures.

- Amede, E.A.; Aklilu, G.G.; Kidane, H.W.; Dalbiso, A.D. Examining the Viability and Benefits of Cement-Stabilized Rammed Earth as an Affordable and Durable Walling Material in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Cogent Engineering 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhang, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Tan, W. Evaluation of Compressive Strength of Cement-Stabilized Rammed Earth Wall by Ultrasonic-Rebound Combined Method. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Khadka, B.; Sun, X.; Li, M.; Jiang, J. Compressive Strength of Rammed Earth Filled Steel Tubular Stub Columns. CASE STUDIES IN CONSTRUCTION MATERIALS 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Standard, NZS 4298:1998. Materials and Workmanship for Earth Buildings, 1998, URL Https://Www.Standards.Govt.Nz/Sponsored-Standards/ Building- Standards/Nzs4298/.

- Mustafa, Y.; Al-Amoudi, O.; Zami, M.; Al-Osta, M. Strength and Durability Assessment of Stabilized Najd Soil for Usage as Earth Construction Materials. BULLETIN OF ENGINEERING GEOLOGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT 2023, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathcote, K.A. Durability of Earthwall Buildings. Construction and Building Materials 1995, 9, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EM_1110-2-1913.Pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).