Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

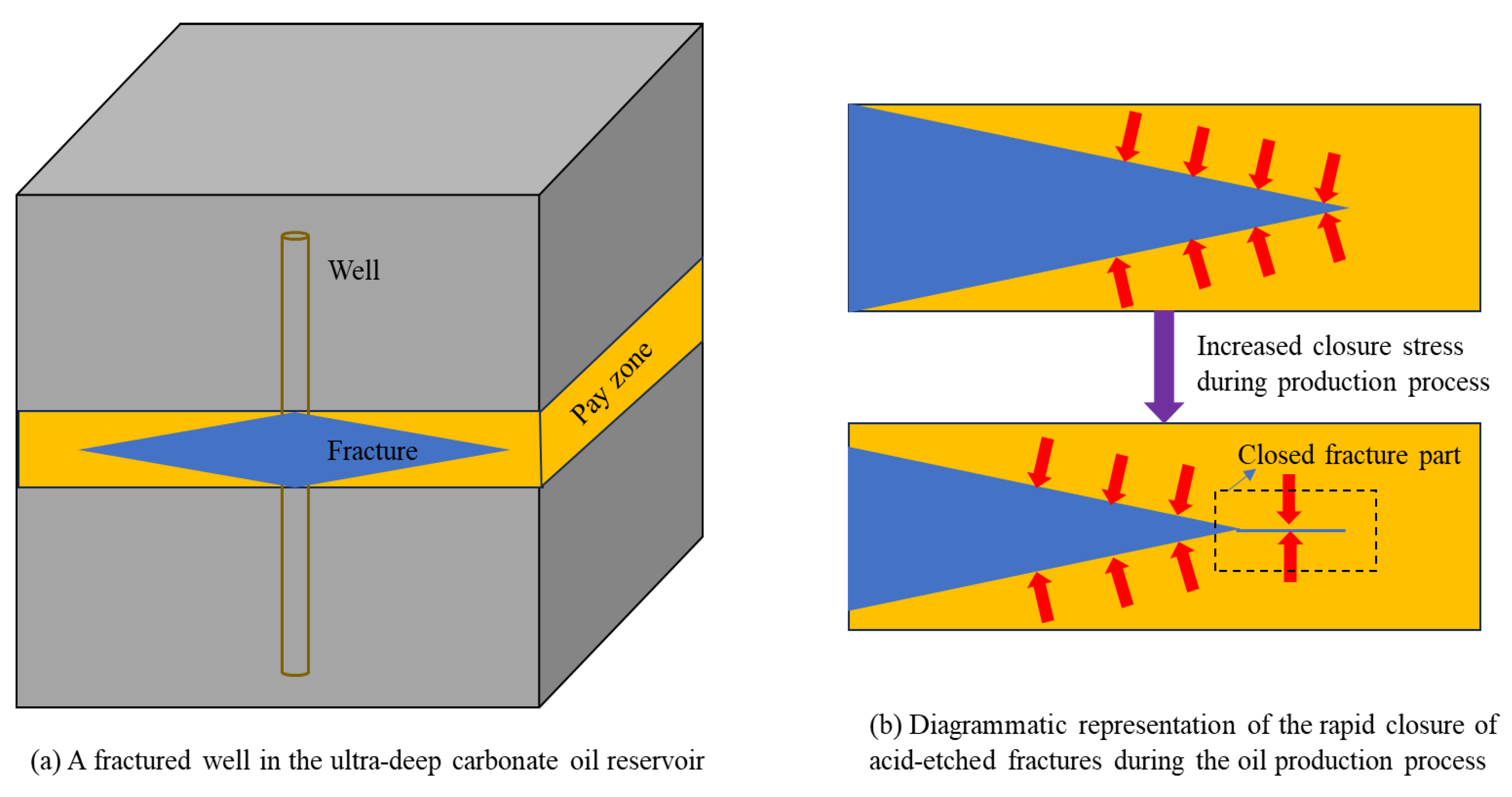

1. Introduction

2. The Model of Matrix-Fracture Coupling Seepage

2.1. Basic Assumptions

- The ultra-deep carbonate reservoir is an isothermal seepage system, and the temperature remains constant during the oil well production process;

- The seepage of the reservoir is a single-phase micro-compressible fluid, and the seepage in the reservoir follows Darcy’s law;

- The reservoir is a cracked carbonate rock, and the creep and stress sensitivity of the matrix and natural fractures are not considered;

- Both the matrix and the fracture are continuous medium and are isotropic;

- Two-dimensional seepage model, no gravity influence is considered.

2.2. Mathematical Model

2.2.1. Acid-Etched Fracture Conductivity Model

2.2.2. Matrix Seepage Equation

2.2.3. Natural Fracture Seepage Equation

2.2.4. Acid-Etched Fractures Seepage Equation

2.3. Model Solution

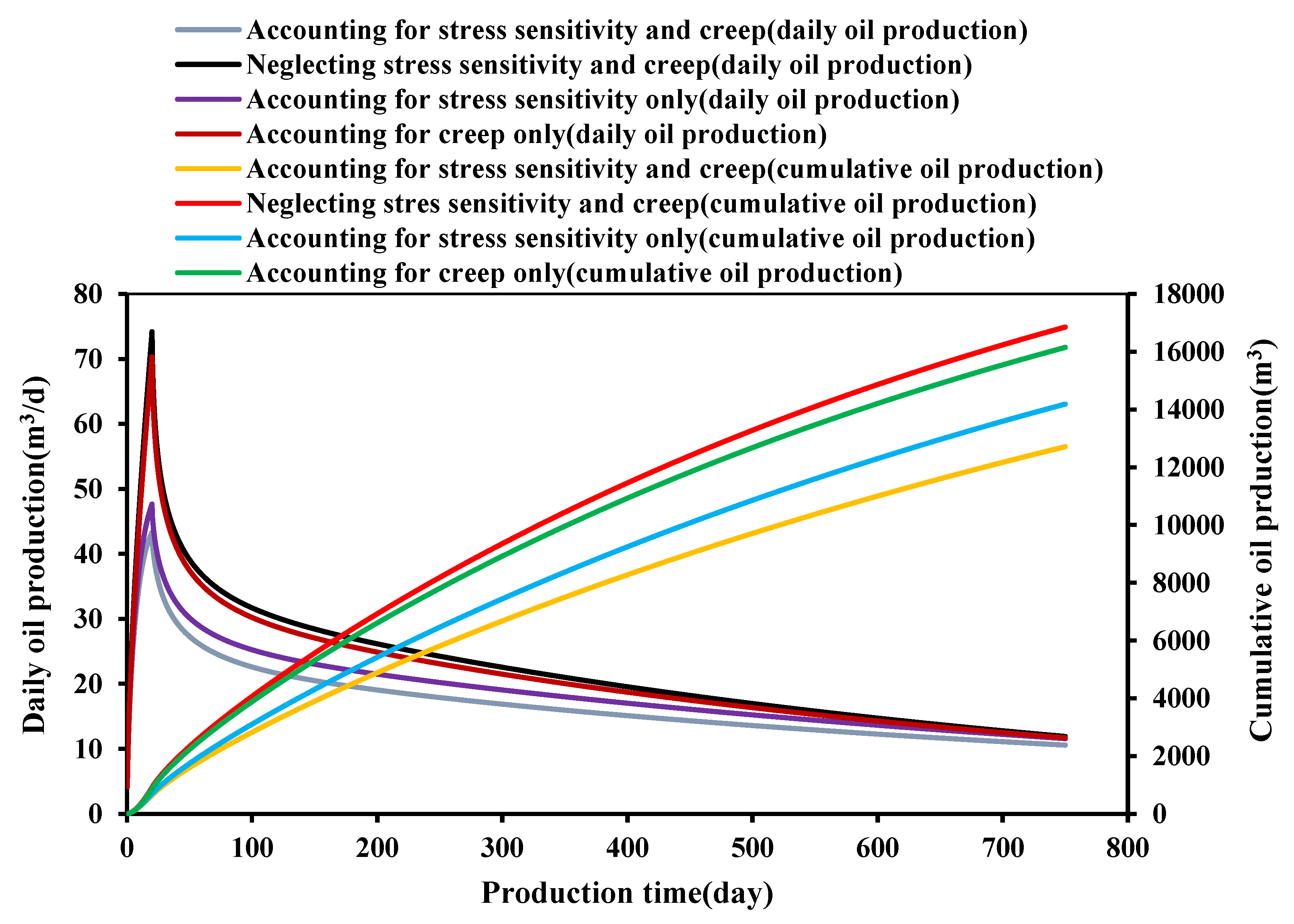

3. Sensitivity Analysis of Influence Factors

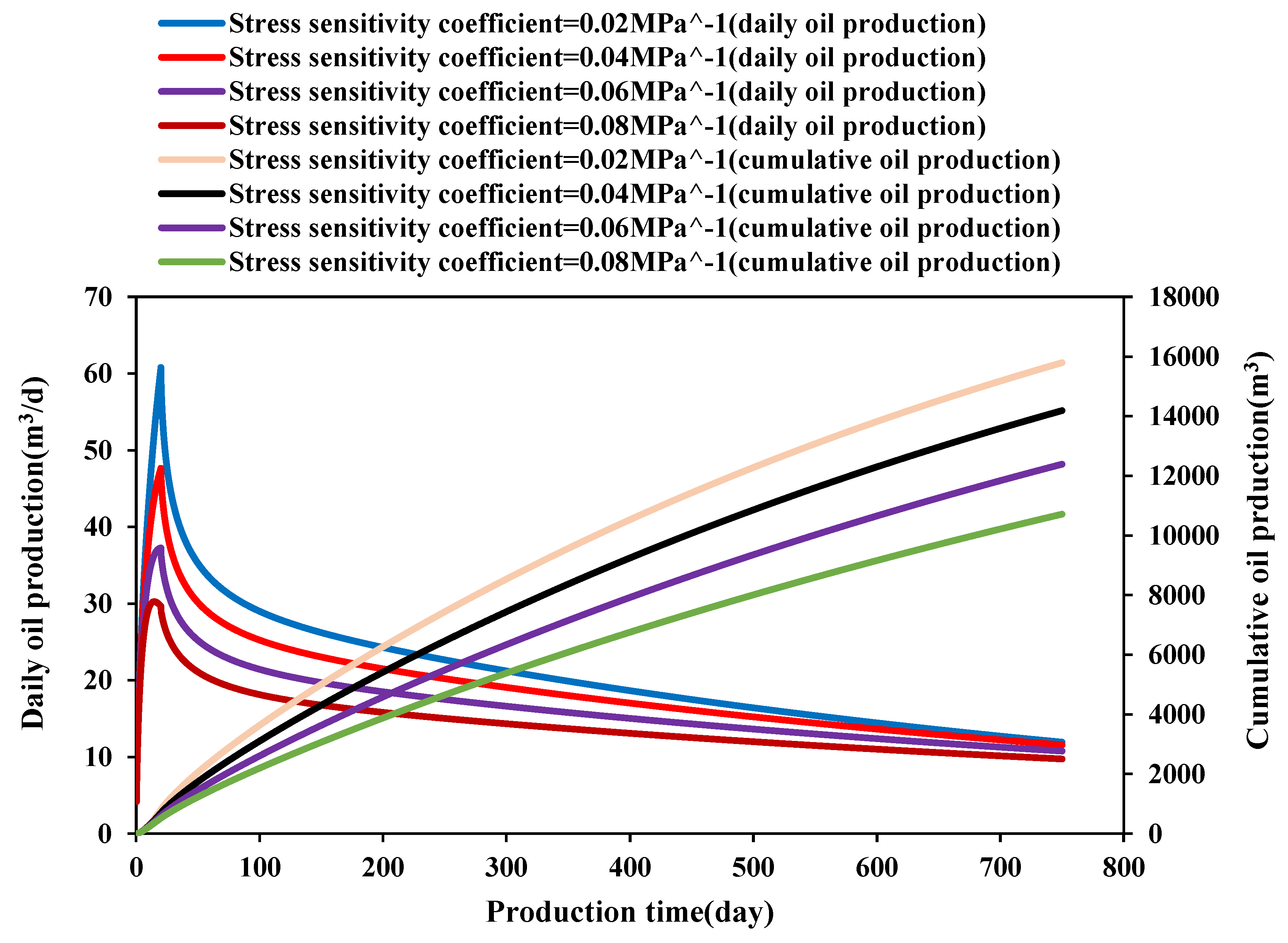

3.1. Effect of Stress Sensitivity on Well Productivity

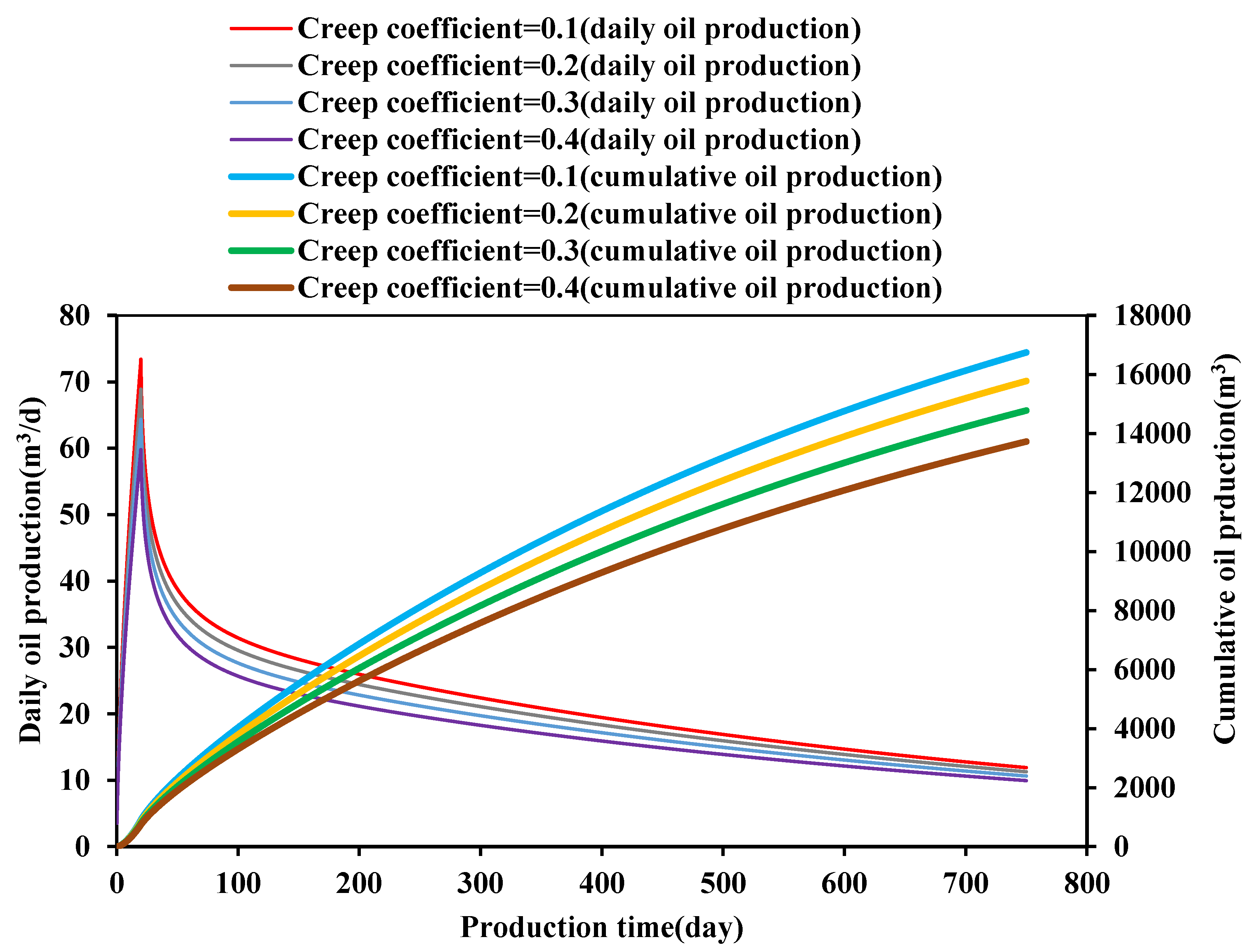

3.2. Effect of Creep on Well Productivity

3.3. Effect of Other Factors on Well Productivity

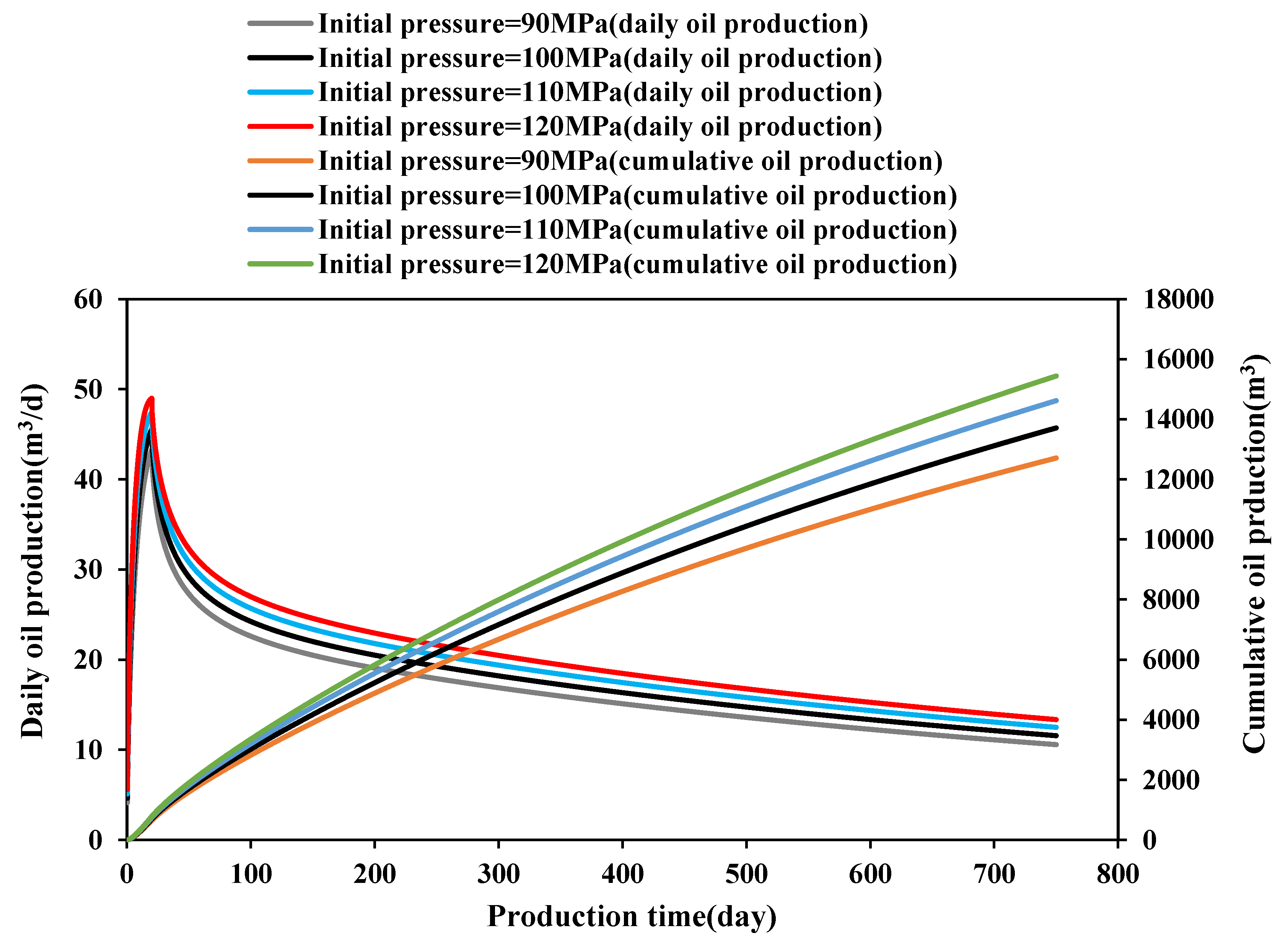

3.3.1. Effect of Initial Pressure

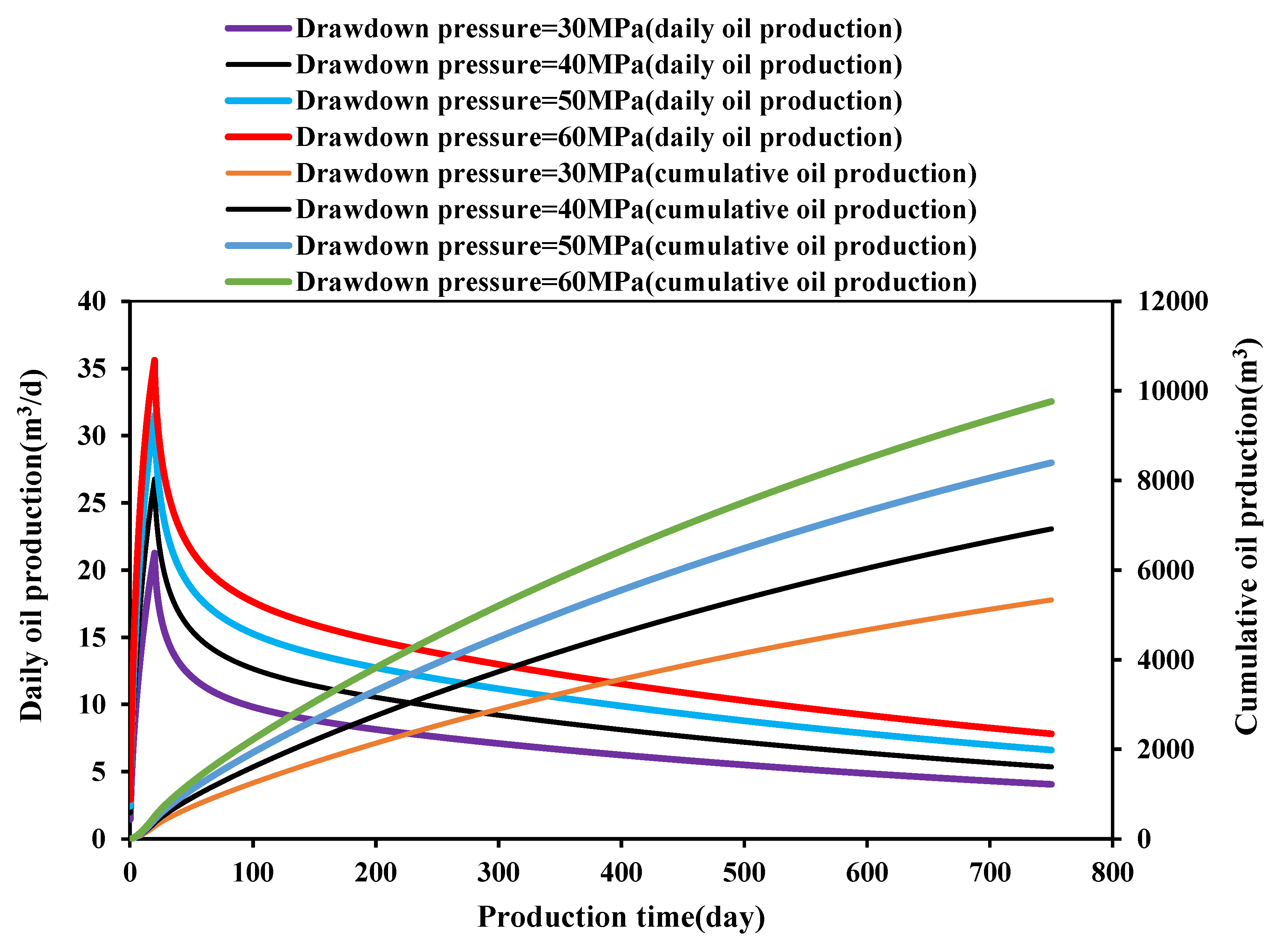

3.3.2. Effect of Drawdown Pressure

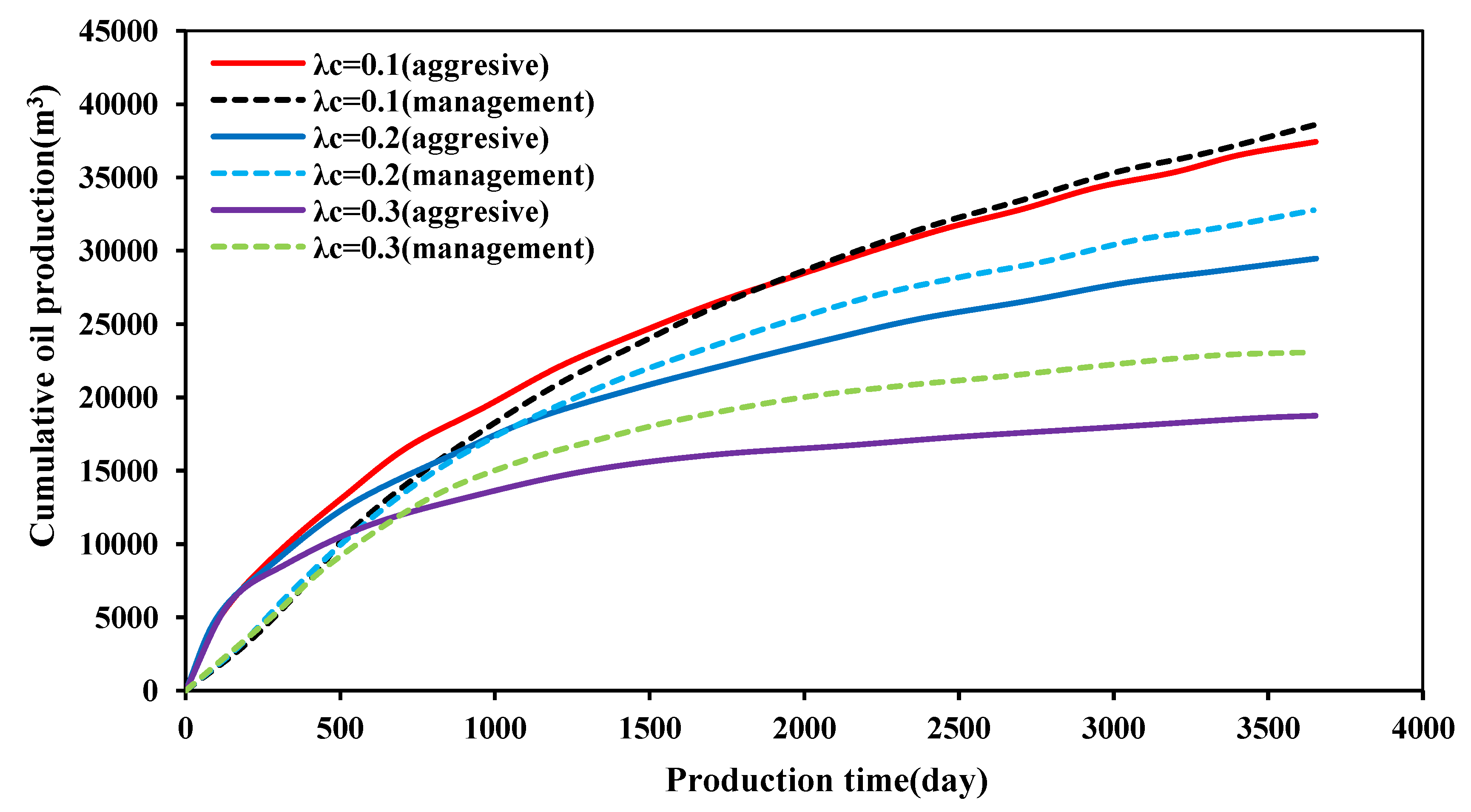

3.3.3. Effect of Production System

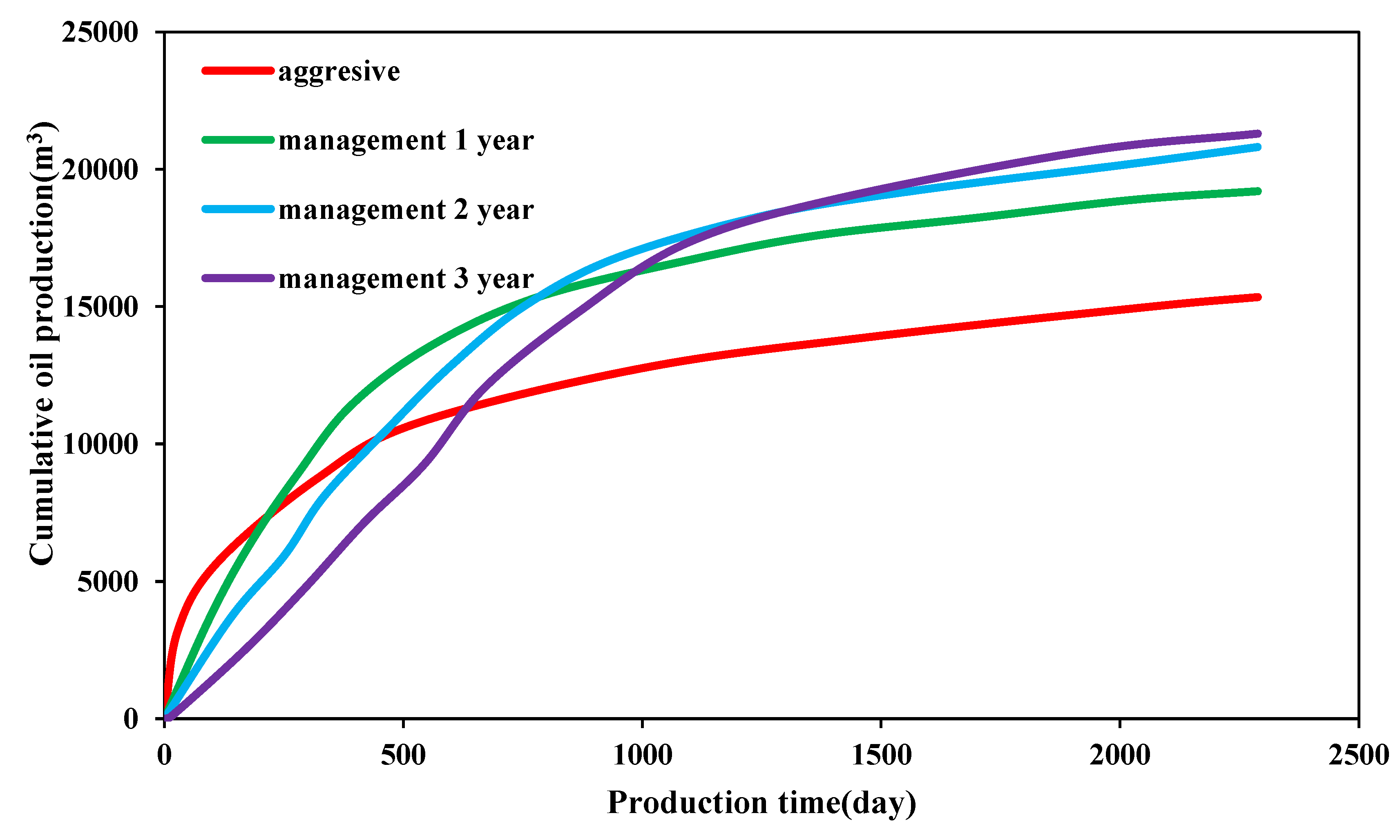

3.3.4. Effect of Management Time

4. Conclusion

- The creep and stress sensitivity characteristics of rocks have a significant impact on the production capacity of ultra-deep carbonate oil wells. The greater the creep coefficient and stress-sensitive coefficient, the lower the oil well productivity. The greater the initial reservoir pressure and drawdown pressure, the higher the daily production and cumulative production of the oil wells. However, at the same time, the greater initial reservoir pressure and drawdown pressure will enhance stress sensitivity and creep, resulting in a decrease in permeability, thereby reducing the cumulative production growth.

- The cumulative production in the early stage of pressure release production is significantly higher than that in pressure controlled production. However, as the pressure control time increases, production reversal occurs. When the pressure control duration reaches three years, the cumulative production increases by 5952 m³ (38.8%). As the creep coefficient increases, the increase in cumulative production for pressure-controlled production compared to pressure-release production becomes more significant. This indicates that the larger the creep coefficient, the better the effect of pressure control production. In other words, the larger the creep coefficient, the more beneficial pressure control production becomes.

- During the development of ultra-deep carbonate oil reservoirs, the effects of creep and stress sensitivity should be fully considered. The production system should be optimized, and the production pressure should be reasonably controlled to enhance the EUR of ultra-deep carbonate oil wells and improve the overall development efficiency of the reservoir.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yi Haiyong, Zhang Benjian, Gu Mingfeng, et al. Discovery of isolated shoals in the Permian Maokou Formation of eastern Sichuan Basin and their natural gas exploration potential. Natural Gas Industry 2024, 44, 1–11.

- Qu Zhanqing, Lin Qiang, Guo Tiankui, et al. Experimental study on acid fracture conductivity of carbonate rock in Shunbei Oilfield. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2019, 26, 533–536.

- Qi Ning, Ma Tengfei, Zhang Zehui, et al. Creep closure mechanism of acid-etched fractures in limestone. Natural Gas Industry 2024, 44, 73–82.

- Han Xu. Study on mechanical characteristics and conductivity of acid etch soften layer in limestone[D]. Chengdu. Chengdu University of Technology, 2018.

- Xiao Yong, Wang Hehua, Mi Zhongrong, et al. Laboratory measurements of acid-etched fracture conductivity for medium-high porosity and low permeability limestone reservoirs in EE oil field[C]//54thU. S. RockMechanics/GeomechanicsSymposium. Virtual. ARMA, 2020:ARMA-2020-1394.

- Yao S, Wang X, Yuan Q, et al. Transient-Rate Analysis of Stress-Sensitive Hydraulic Fractures: Considering the Geomechanical Effect in Anisotropic Shale. SPE Reservoir Evaluation Engineering 2018, 863-888. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Luo W, Chen Z. An integrated approach to optimize bottomhole-pressure-drawdown management for a hydraulically fractured well using a transient inflow performance relationship. SPE Reservoir Evaluation Engineering, 2020, 23, 95–111. [CrossRef]

- Cheng An, John Killough, Xiaoyang Xia. Investigating the effects of stress creep and effective stress coefficient on stress-dependent permeability measurements of shale rock. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2020, 108155. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Jiajia. Study on the conductivity of acid etching fractures in low Young’s modulus carbonate rocks[D]. Langfang:Institute of Porous Flow&Fluid Mechanics, China National Petroleum Corporation&Chinese Academy of Science, 2021.

- Li Dongmei, Li Huihui, Zhu Suyang. Study of permeability stress sensitivity of large-scale discrete fracture: a case study of Shunbei Oil Field. Fault Block Oil Gas Field 2024, 31, 147–153.

- Zhou Bocheng. Study on stress sensitivity of long-term acid fracture conductivity in carbonate reservoirs[D]. Beijing:China University of Petroleum(Beijing), 2019.

- Bailu Teng, Huazhou Li, Haisheng Yu. A Novel Analytical Fracture-Permeability Model Dependent on Both Fracture Width and Proppant-Pack Properties. SPE Journal 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bailu Teng, Wanjing Luo, Zhuo Chen, Botao Kang, Ling Chen, Tianyi Wang. A comprehensive study of the effect of Brinkman flow on the performance of hydraulically fractured wells. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yu Pang, M. Y. Soliman, Hucheng Deng, Hossein Emadi. Analysis of Effective Porosity and Effective Permeability in Shale-Gas Reservoirs With Consideration of Gas Adsorption and Stress Effects. SPE Journal, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ankit Mirani, Matteo Marongiu-Porcu, HanYi Wang, Philippe Enkababian. Production-Pressure-Drawdown Management for Fractured Horizontal Wells in Shale-Gas Formations. SPE Reservoir Evaluation Engineering, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tao Zhang, Jianchun Guo, Jie Zeng, Hui Zhang, Zhihong Zhao, Fanhui Zeng, Wenhou Wang. A transient source-function-based embedded discrete fracture model for simulation of multiscale-fractured reservoir:Application in coalbed methane extraction. Gas Science and Engineering, 2025(133). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, L.; Rong, T.; Zhang, L.; Ren, W.; Su, T. Creep-based permeability evolution in deep coal under unloading confining pressure. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 65, 185–196. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.W., Zhang, L., Wang, X. Y., Rong, T. L., Wang, L. J., 2020. Effects of matrix fracture interaction and creep deformation on permeability evolution of deep coal. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 127, 104236. [CrossRef]

- Cui Yudong, Lu Cheng, Guan Ziyue, Luo Wanjing, Teng Bailu, Meng Fanpu, Peng Yue. Effects of creep on depressurization-induced gas well productivity in South China Sea natural gas hydrate reservoirs. Petroleum Reservoir Evaluation and Development 2023, 13, 809–818.

- Chen Hao. Study on creep mechanical behavior and creep model of fractured rock under stress-seepage coupling conditions[D]. Chengdu:Xihua University, 2023.

- Du Xulin, Cheng Linsong, Niu Langyu, Chen Yuming, Cao Renyi, Xie Yonghong. NumericalSimulationof 3D Discrete Fracture Networks Considering Dynamic Closure of Hydraulic Fracturesand Natural Fractures. Chinese Journal of Computational Physics 2022, 39, 453–464.

- Tang Jianxin, Teng Junyang, Zhang Chuang, Liu Shu. Experimental study of creep characteristics of layered water bearing shale. Rock and Soil Mechanics 2018, 39 (Supp. 1), 33–41.

- Feng Jianwei, Sun Zhixue, Wang Yandong, She Jiaofeng. Study on Stress Sensitivity of or dovician Fractures in Hetianhe Gas Field, Tarim Basin. Geological Journal of China Universities 2019, 25, 276–286.

- Zhao Jingya. Study on pore-elastic viscoplasticity mechanical properties of shale and its influence on conductivity of artificial fracture[D]. Beijing:China University of Petroleum(Beijing), 2023.

- Liu Weiyan. Stress and time effects offracturedsandstone permeability[D]. Shijia Zhuang:Shijia zhuang Tiedao University, 2022.

- Rang Tengda. Research on Fracture Deformation Mechanism and Numerical Simulation Methods of Shale Oil Reservoir[D]. Beijing:China University of Petroleum(Beijing), 2023.

| Parameter | Value | Unit | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial pressure | 90 | MPa | Oil saturation | 60 | % |

| Reservoir temperature | 200 | ℃ | Well radius | 0.1 | m |

| Matrix porosity | 2.1 | % | Oil viscosity | 10 | mPa·s |

| Natural fracture porosity | 1.2 | % | Fracture length | 80 | m |

| Matrix permeability | 0.5 | mD | Fracture height | 30 | m |

| Natural fracture permeability | 10 | mD | Initial fracture conductivity | 2 | D·cm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).