2.2.1. Maximum Shannon entropy portfolio model

Shannon entropy, originally developed within the field of information theory to address communication system challenges, has since evolved into a powerful and versatile tool across multiple disciplines, including finance and portfolio management. As a fundamental measure of uncertainty, Shannon entropy offers a rigorous mathematical framework for quantifying disorder and randomness in complex systems. In financial contexts, it is increasingly recognized as a robust alternative to traditional risk measures such as variance and standard deviation. Among the early proponents of this perspective, Simonelli [

22] emphasized the enhanced ability of entropy-based models to capture the multifaceted nature of portfolio uncertainty and diversification, outperforming conventional deviation-based metrics. This view was further supported by Philippatos and Wilson [

17,

18], who formally established the theoretical link between Shannon entropy and financial risk. By incorporating entropy as a diversification metric, investors gain the ability to systematically evaluate the uncertainty embedded in different asset allocations, contributing to more resilient and structurally balanced portfolios [

22].

The integration of Shannon entropy into portfolio theory has led to the development of advanced optimization frameworks that transcend the inherent limitations of mean-variance models. Unlike classical approaches that rely on distributional assumptions and linear measures of dispersion, entropy-based methods are non-parametric and distribution-free. This flexibility is particularly advantageous in volatile and nonlinear market environments, where asset returns frequently deviate from normality. As a result, entropy-driven strategies have garnered increasing attention from both researchers and practitioners seeking robust, adaptive, and theoretically sound tools for financial decision-making. In this context, portfolio optimization is reframed as the problem of maximizing Shannon entropy—striking an optimal balance between diversification and risk mitigation. By constructing portfolios that maximize entropy, investors can reduce concentration risk and promote allocation uniformity, thereby enhancing structural stability. This probabilistic approach to uncertainty enables the design of investment strategies that are inherently more resilient to turbulent and unpredictable market conditions.

The following section presents the formal mathematical formulation of this entropy-based portfolio optimization model.

Shannon defined entropy as the amount of information available to a system of states with the probability vector ,. Explicitly, Shannon entropy has the form is defined by , where is the weight of asset in the portfolio.

Shannon entropy is used to optimize a portfolio by replacing variance with entropy in the known optimization model (mean-variance). Thus, we obtain the model:

where is the expected average return of the portfolio and the level is assumed by the investor.

Using the Lagrange multipliers method, we obtain:

The first-order conditions become:

Because we have that , we obtain , we rewrite in (#) and obtain

, i = where the two multipliers

verify the relationships, given the constraints of the optimization problem, where we replaced

with the value obtained above

2.2.2. Maximum second order entropy portfolio model

In this section, we develop a portfolio optimization model that incorporates return, second-order entropy, and variance as core components. The model seeks to maximize a weighted combination of expected return and entropy, subject to a risk constraint expressed via variance. This approach enhancesdiversification and liquidity, while ensuring that the overall risk remains within an acceptable level, as defined by the investor.

Tsallis Entropy : where

(For in Tsallis entropy we obtain the informational entropy introduced by O.0nicescu, given by )

Second order entropoy (Tsallis with ):Remarks:

1. For a given portfolio, this kind of entropy measures the correlation degree of the assets from the portfolio ()

2. A lower entropy implies greater concentration (lower diversification), whereas a higher entropy reflects greater diversification, which may contribute positively to portfolio liquidity

Optimization Problem Formulation

where

is the expected average return of the portfolio and the level,

is assumed by the investor

Solving the portfolio optimization problem

Using the Lagrange multipliers method, we obtain:

The first-order conditions become:

Because we have that

, we

Replacement relationship (*) we get

+ )+ where the two multipliers verify the relationships, given the constraints of the optimization problem, where we replaced with the value obtained above

2.2.3. The Maximum Weighted Shannon Entropy Portfolio Model

We begin by introducing the concept of weighted entropy, as originally proposed by Guiasu, which extends the classical Shannon entropy by incorporating a vector of strictly positive weights. The weighted entropy is defined as follows:

Guiasu defined entropy as the amount of information available to a system of states with the probability vector ,. Explicitly, Guiasu entropy has the form , where > 0 represent the weights associated with each probability component nd. This formulation allows for a more flexible representation of uncertainty by accounting for the relative importance or influence of each asset in the portfolio.

The proposed optimization framework builds upon the principle of maximum entropy, incorporating both mean and variance constraints to ensure consistency with classical portfolio theory. The portfolio optimization problem can thus be reformulated as the maximization of the weighted Shannon entropy subject to constraints on the expected return and variance. Formally, we define the problem as follows:

where

is the weight of asset i in portfolio,

E is the desired expected return of the portfolio,

the desired portfolio variance,

reflects the importance of asset i

This approach represents an alternative to the classical Markowitz framework, offering a richer modeling of uncertainty and potential for enhanced portfolio diversification through entropy maximization.

Using the Lagrange multipliers method, we obtain:

The first-order conditions become:

+ + (#)

Because , we obtain , we rewrite in (#) and obtain

, i

=, where the two multipliers

verify the relationships, given the constraints of the optimization problem, where we replaced

with the value obtained above

2.3 Case studies

In this section, we apply the maximum second-order entropy model to a portfolio composed of major cryptocurrencies. The data used in the analysis reflects market activity from January to March 2025, with weekly returns collected from publicly available cryptocurrency trading platforms. Our goal is to test the practical applicability of the entropy-based optimization model and to demonstrate its ability to generate well-diversified portfolios under real market conditions.

The results presented below are derived using the second-order entropy function and reflect optimal weight allocations and associated entropy values under different portfolio compositions.

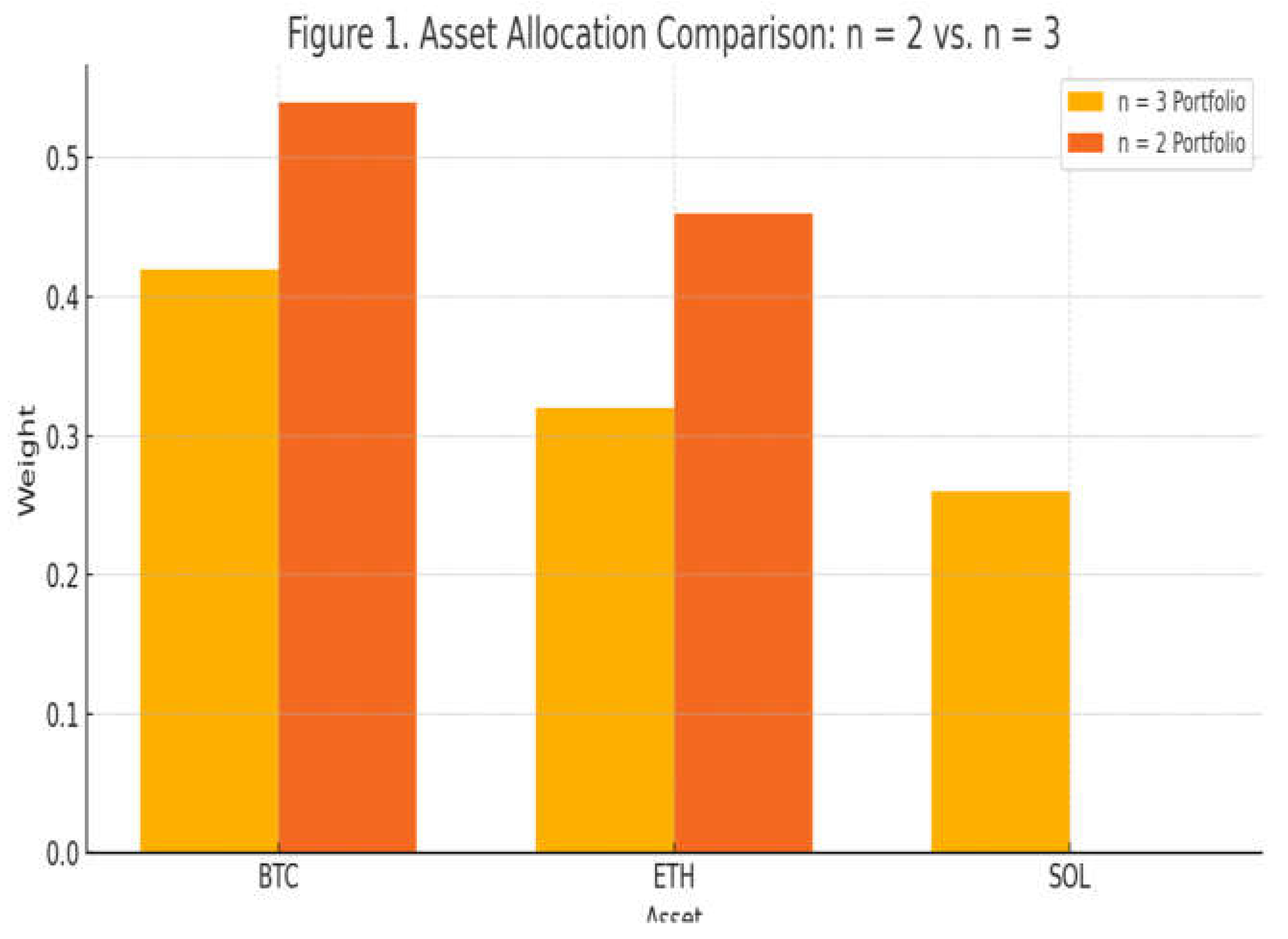

Case n=2:Portfolio Optimization with Two Cryptocurrencies

We first consider a simplified portfolio comprising two major cryptocurrencies: Bitcoin (BTC) andEthereum (ETH). Using the second-order entropy model and the data collected from Q1 2025, we computed the optimal allocation that maximizes the entropy function under standard return and variance constraints.

Using historical price data, we calculate statistics:

E₁ = 0.0565, σ₁² = 0.46; E₂ = 0.0133, σ₂² = 1; σ₁₂ = 0.203. Based on these inputs, we have model:

Using the formulas presented in the section 2.2 obtain

) + x₁ =γ₁/2(0.0565-0.0349) + γ₂/2(0.033-0.8)/2) + 0.5 = 0.01γ₁ - 0.18γ₂ + 0.5

x₂ = γ₁/2(0.0133-0.0349)+γ₂/2)(0.775-0.8)/2)) + 0.5 = -0.01γ₁+0.18γ₂+0.5

where the two multipliers γ₁and γ₂ verify relations :

x₁⋅ 0.0565 + x₂⋅ 0.0133 = 0.05

x₁⋅ 0.033 + x₂⋅ 0.0775 = 0.1,

or

(0.01γ₁ - 0.18γ₂+ 0.5)⋅0.0565 + (-0.01γ₁+ 0.18γ₂ + 0.5)⋅0.0133 = 0.05

(0.01γ₁ - 0.18γ₂+ 0.5)⋅0.033 + (-0.01γ₁+ 0.18γ₂ + 0.5)⋅0.775 = 0.1,

┊ or

0.0055γ₁ - 0.0077γ₂ + 0.03 = 0.05

- 0.0074γ₁ + 0.1335γ₂ + 0.4 = 0.1

We will solve the sistem and we have γ₁ = 0.53155 and γ₂ = -2. 2177

We obtain x₁ = 0.905 and x₂ = 0.095

This result indicates that, under the given preferences and market conditions, the optimal portfolio heavily favors Bitcoin (BTC), allocating approximately 90.5% of the capital to BTC and only 9.5% to ETH.

Case n=3Portfolio Optimization with Three Cryptocurrencies

In this section, we consider a portfolio composed of three major cryptocurrencies: Bitcoin (BTC), Ethereum (ETH), and Solana (SOL), observed over the period 18 January 2025 – 21 March 2025. The optimization system was solved numerically using MATLAB, We have our inputs and we are going to use maximum second order entropy portfolio model. We obtain :

max (- x₁² - x₂² - x₃²)

x₁⋅0.0565 + x₂⋅0.0133 + x₃⋅0.0755 = 0.05

x₁⋅0.033 + x₂⋅0.775 + x₃⋅0.105 = 0.1,

x₁ + x₂ + x₃ = 1

Using the formulas presented in the section 2 obtain

x₁ = γ₁/2 (0.0565 - 0.048) +γ₂/2(0.033 - 0.3) + 0.33 = 0.004γ₁ - 0.134γ₂ + 0.33

x₂ = γ₁/2(0.0133-0.048) + γ₂/2(0.775-0.3) + 0.33 = -0.017γ₁ + 0.232γ₂ + 0.33

x₃ = γ₁/2(0.0755-0.048) + γ₂/2(0.105-0.3) + 0.33 = 0.013γ₁ - 0.098γ₂ + 0.33

where the two multipliers γ₁ and γ₂ verify relations :

(0.004γ₁-0.134γ₂+0.33)⋅0.0565+(-0.017γ₁+0.232γ₂+0.33)⋅0.0133+(0.013γ₁-.098γ₂+0.33)⋅0.0755 = 0.05

(0.004γ₁-0.134γ₂+0.33)⋅0.033+(-0.017γ₁+0.232γ₂+0.33)⋅0.775+(0.013γ₁-0.098γ₂+0.33)⋅0.105

= 0.1,or

0.003γ₁ - 0.012γ₂ + 0.048 = 0.05

-0.036γ₁ + 0.072γ₂ + 0.3 = 0.1,

we have γ₁ = 10. 444,γ₂ = 2. 444 and we obtain x₁ = 0.05 , x₂ = 0.72, x₃ = 0.23

Compared to the two-asset case, the three-asset configuration produced a more balanced and diversified portfolio. The entropy value increased significantly, indicating an improvement in diversification. The numerical solution favors Ethereum (72%) over Bitcoin (5%) and Solana (23%), suggesting that, under the given statistical assumptions, ETH offers the most efficient return-risk combination. This shift highlights the sensitivity of entropy-based optimization to the underlying input data and the ability of the model to capture subtle structural differences across assets. Moreover, the enhanced entropy level suggests greater portfolio resilience under dynamic market conditions

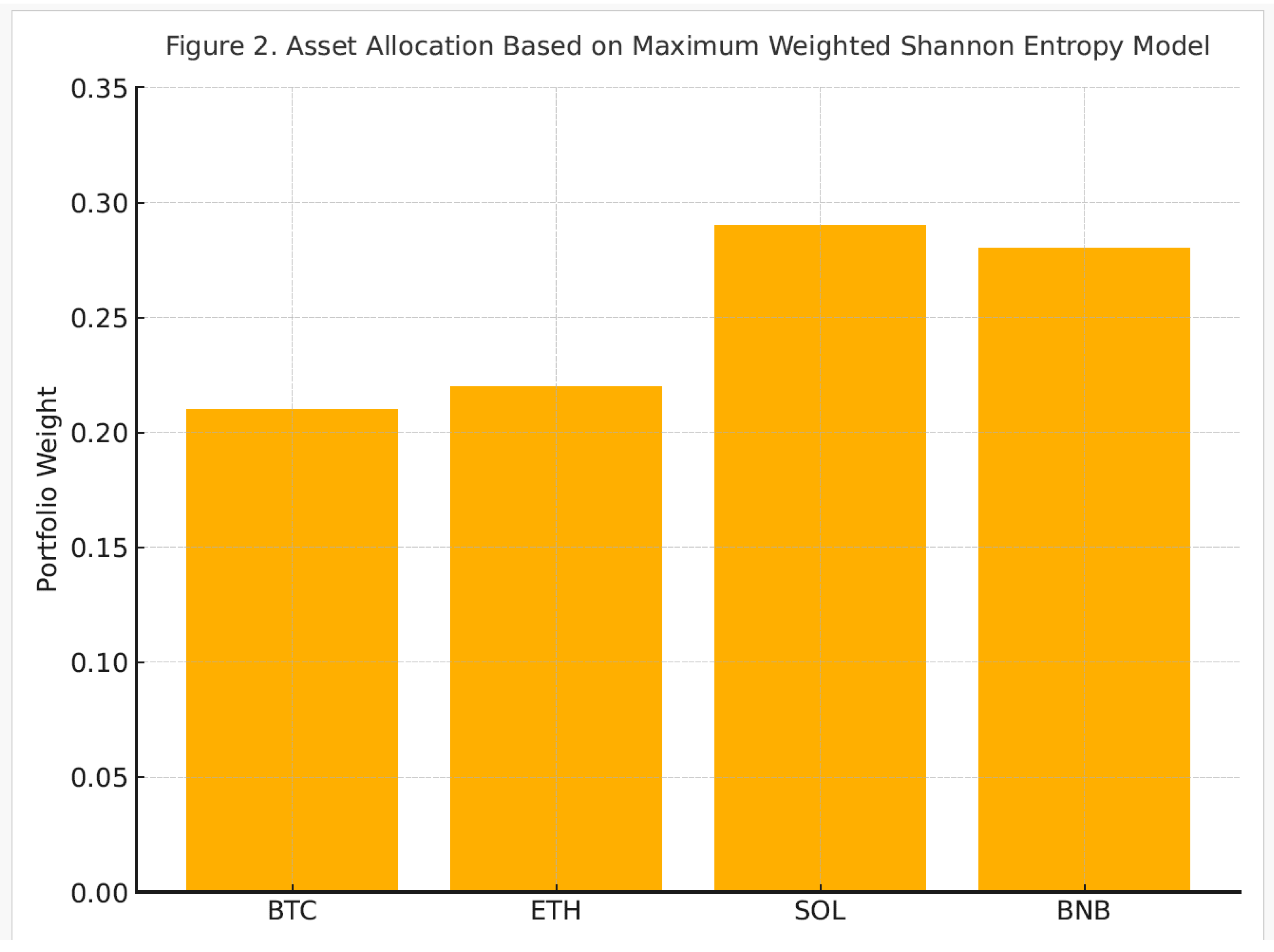

Case n = 4Portfolio Optimization with For Cryptocurrencies

In this section, we consider a portfolio composed of four major cryptocurrencies—Bitcoin (BTC), Ethereum (ETH), Solana (SOL), and Binance Coin (BNB)—traded actively during the period January–March 2025. These digital assets represent a wide range of use cases and exhibit significant market capitalization, liquidity, and volatility, making them relevant for a realistic portfolio optimization scenario in the current crypto landscape.

We apply the maximum weighted Shannon entropy portfolio model for portfolio selection. This approach emphasizes diversification by minimizing portfolio concentration, i.e., maximizing entropy, while simultaneously imposing constraints related to expected return and overall risk exposure.

The model we use is defined as follows:

where

is the weight of asset i in portfolio,

E is the desired expected return of the portfolio.We choose E = 0,4

the desired portfolio variance. We choose = 170

reflects the importance of asset i. We choose = = 1

These constraints simulate a scenario where the expected return of the portfolio must reach a minimum target (e.g., 0.4), while a weighted measure of asset riskinterpreted here as a proxy for volatility, market exposure, or price confidence—is bounded by 170 units.

This structure is consistent with historical performance patterns observed during Q1 2025 across the selected crypto assets. The optimization system was solved numerically using MATLAB, which all owed for accurate handling of symbolic constraints and nonlinear systems.

We obtained the optimal asset allocation within the entropy-based

framework. The resolution process involved simultaneously satisfying the conditions of expected return, variance threshold, and total portfolio allocation. The solution yields the following asset weights:

x1 = 0.21(BTC),

x2 = 0.22(ETH),

x3 = 0.29(SOL),

x4 = 0.28(BNB)

These results reflect a relatively balanced distribution of capital across the

four assets, with a slightly higher allocation toward Solana and Binance Coin. This may indicate a superior return-to-volatility ratio for these tokens during Q1 2025, or a better informational weight under the entropy framework. Notably, the allocation is not dominated by a single asset, which confirms that the entropy model naturally leads to diversification, even under strong constraints.

Furthermore, this outcome underlines the core strength of the entropy-

based approach: its ability to integrate multiple dimensions of portfolio quality—namely, return, risk, and diversification—into a unified and mathematically consistent optimization scheme. While traditional models may struggle under high volatility and non-normal return distributions (characteristic of crypto markets), the entropy model adapts well due to its distribution-independent structure and flexible treatment of uncertainty.

In summary, the entropy-based allocation obtained herein demonstrates

not only mathematical feasibility but also practical relevance for crypto investors seeking resilient portfolio structures in volatile market contexts. The result confirms that entropy can serve as both a theoretical and operational pillar in modern portfolio construction, particularly in digital asset environments.