Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

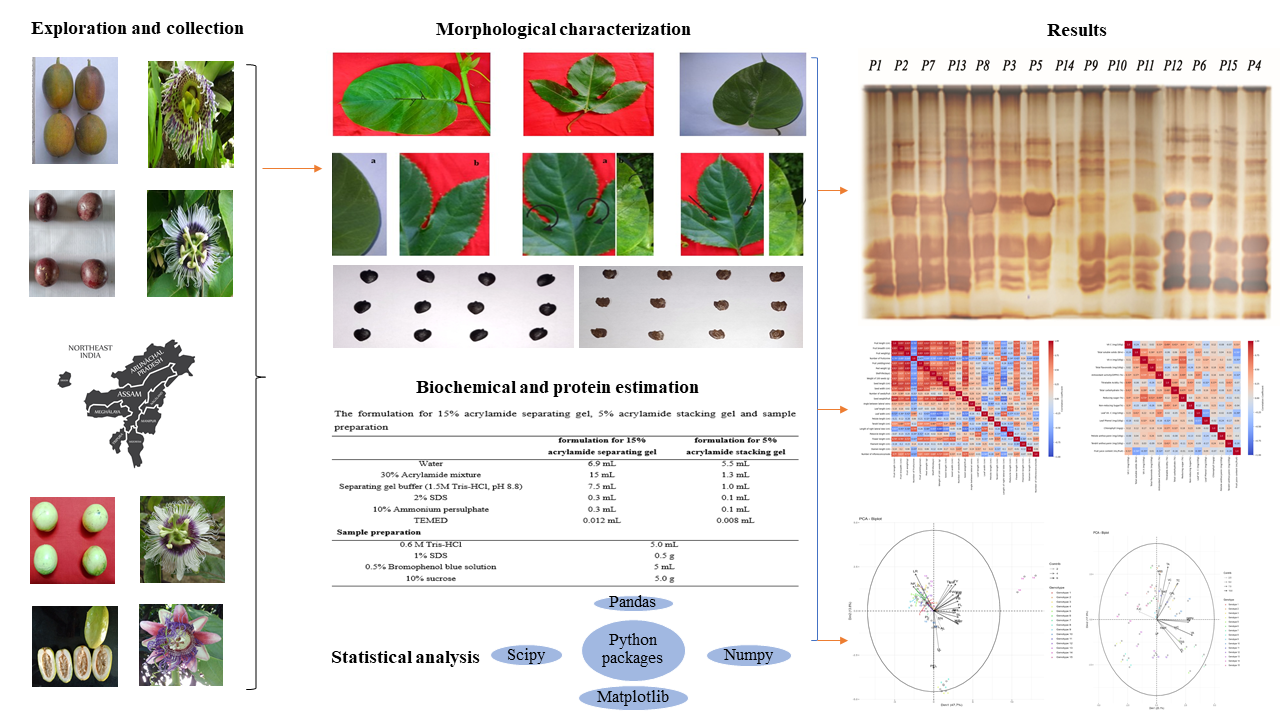

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Details of Genotypes

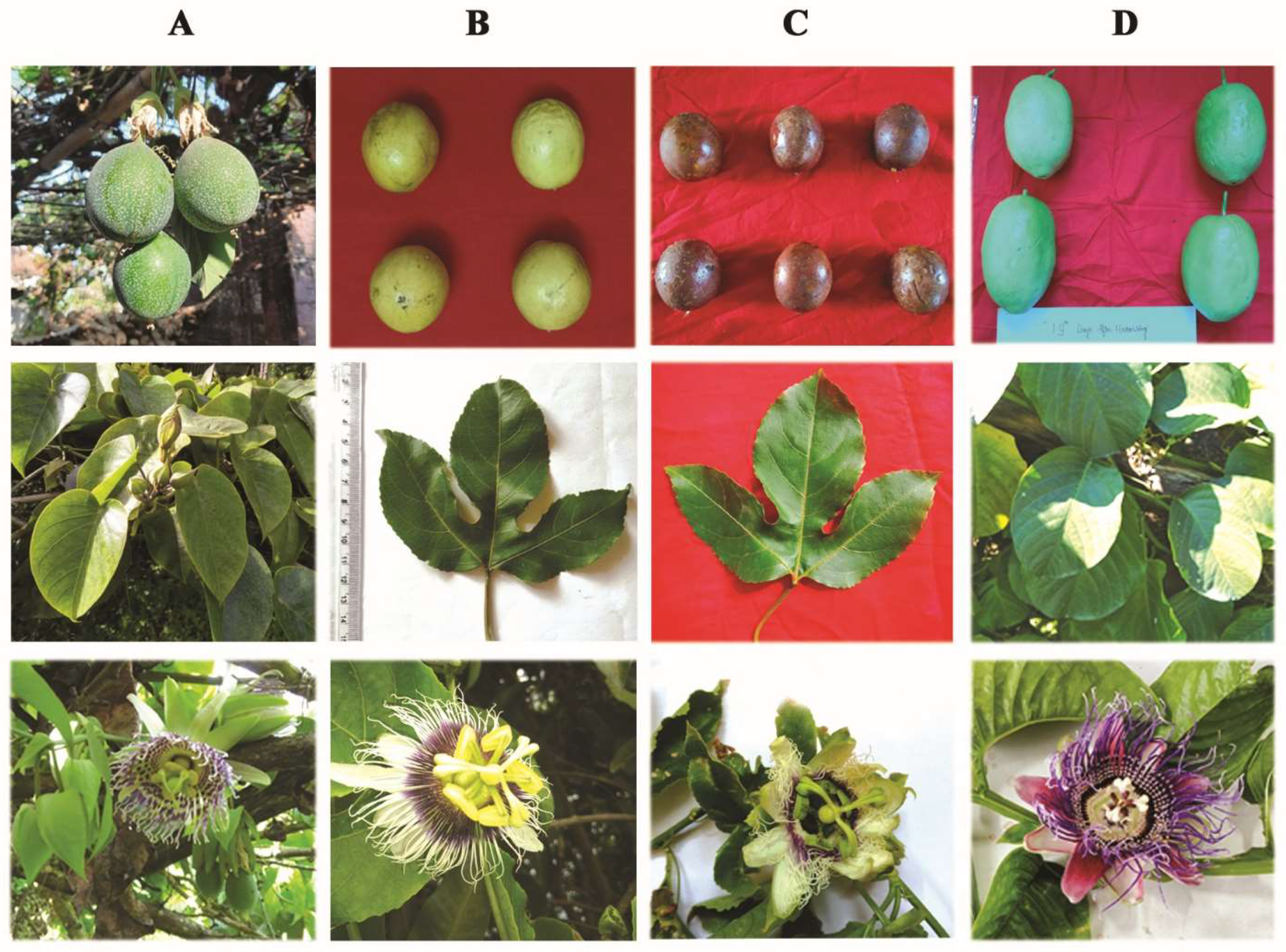

2.2. Morphological Characterisation

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. Biochemical Characterisation

2.5. Protein Extraction and Estimation

2.6. Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

2.7. Staining Solution

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Parameters

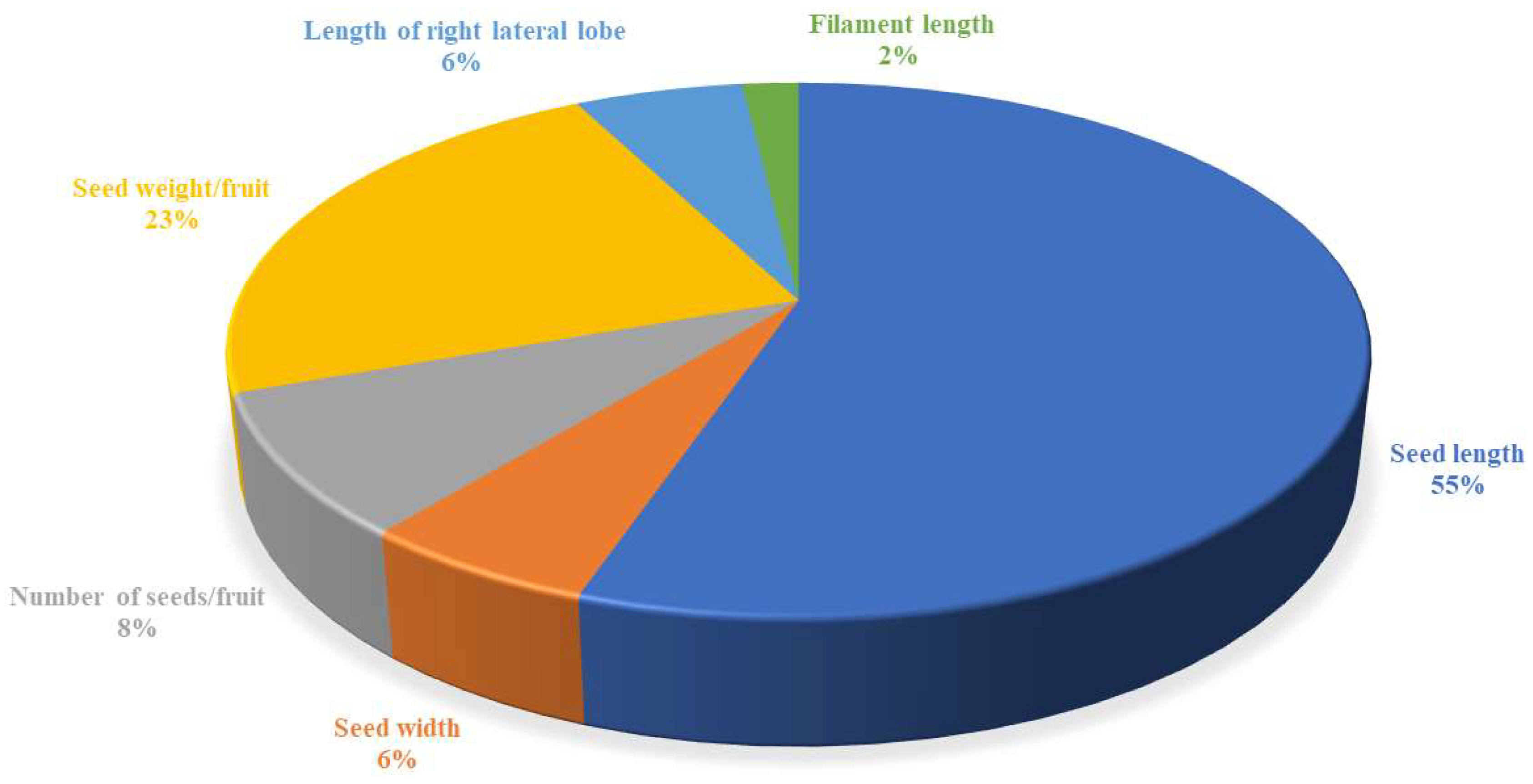

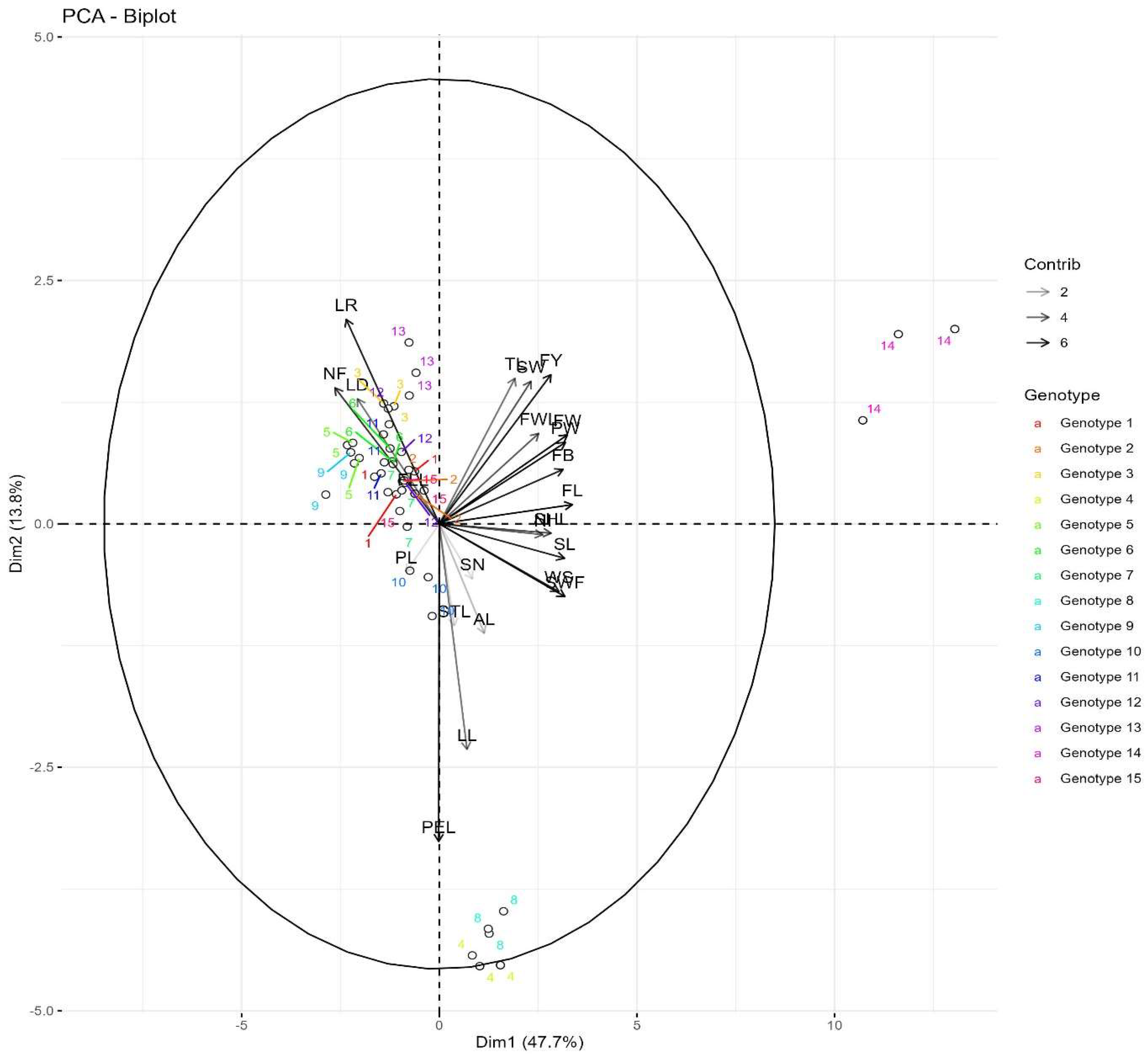

3.2. Contributions of Morphological Characters Towards Diversity in Passiflora Species

3.3. Biochemical Characteristics of Fruit Juice, Leaves, Petioles and Tendrils

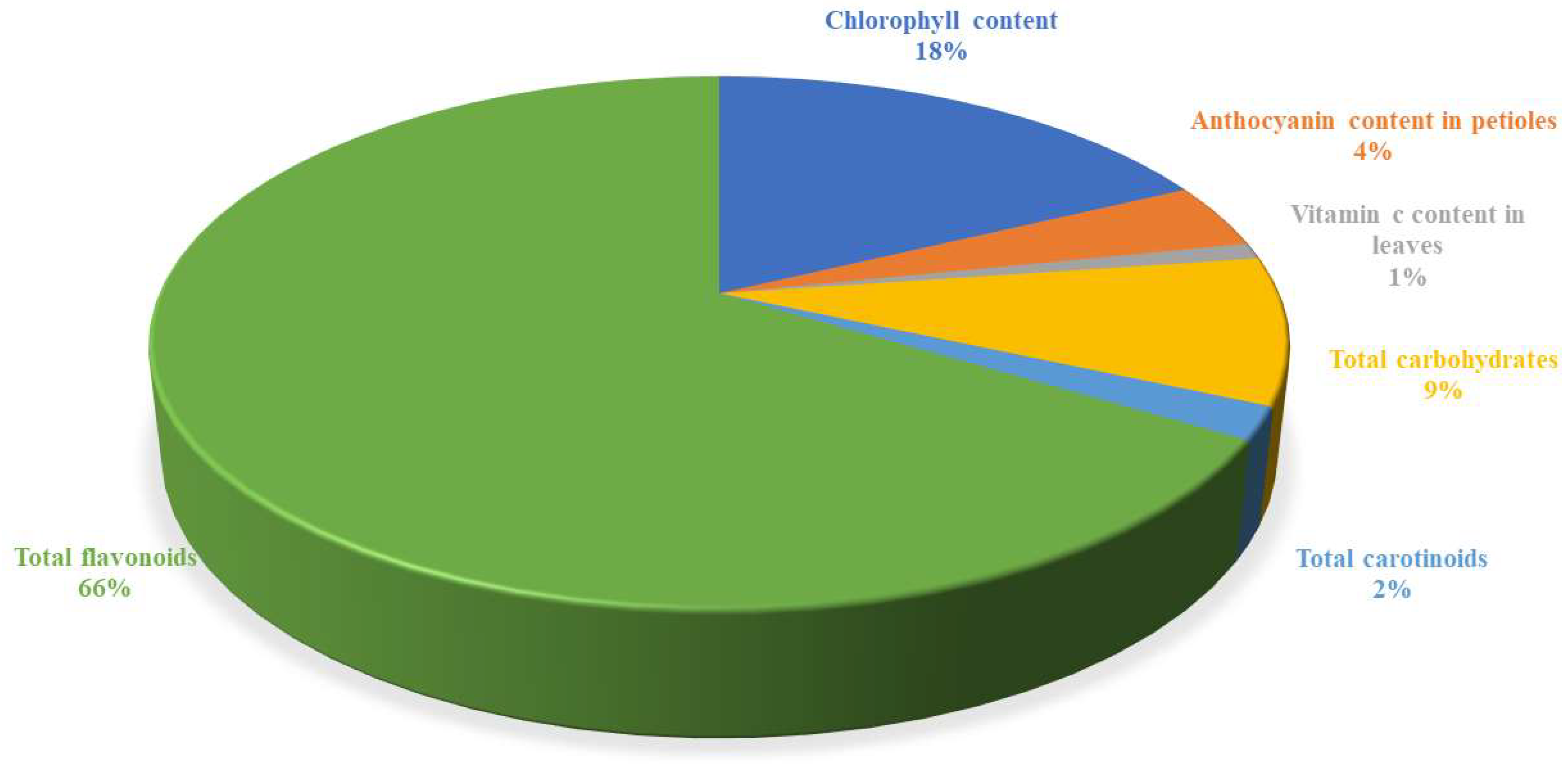

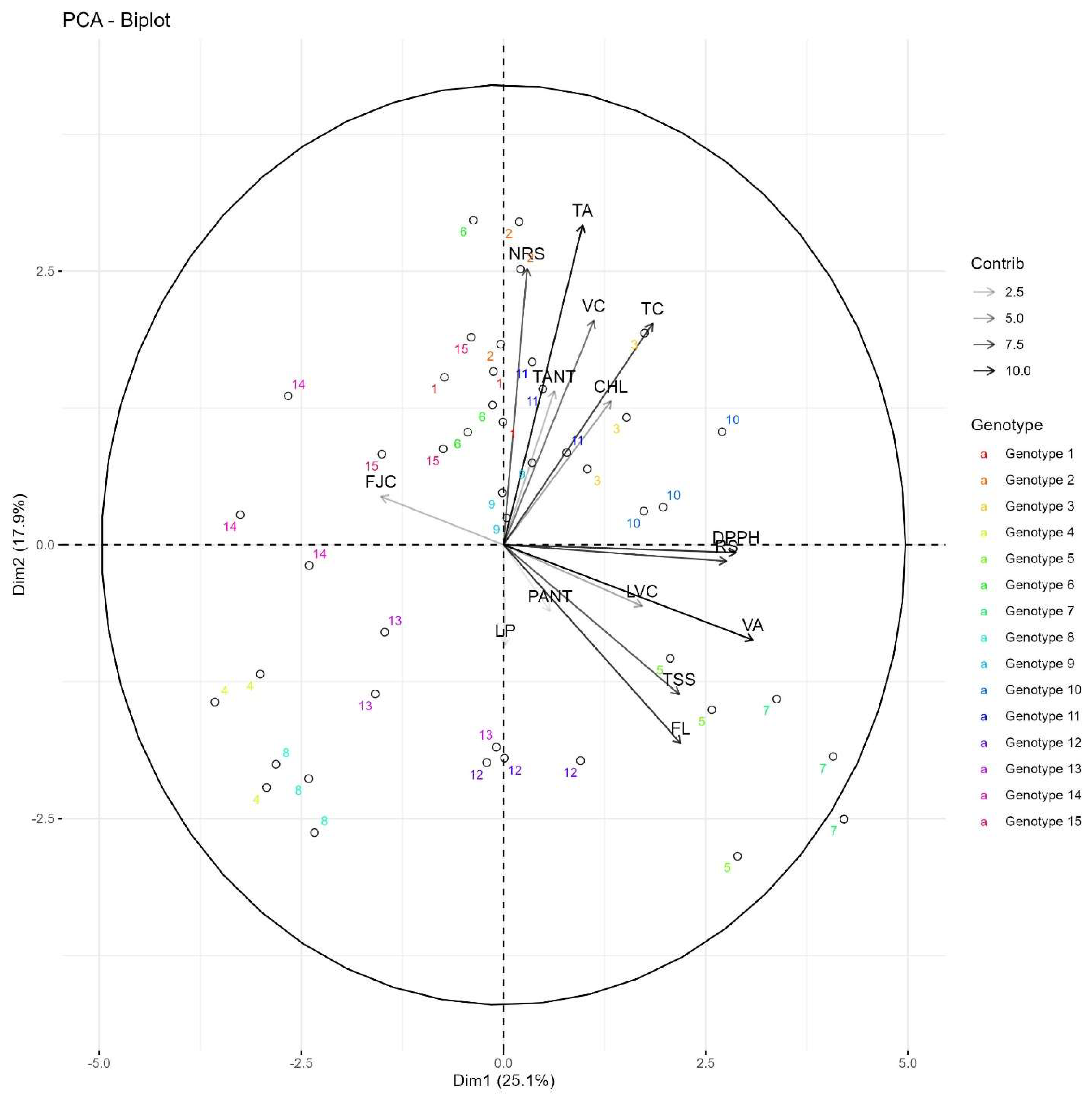

3.4. Maximum Percentage Contributions of Biochemical Characters Towards Diversity in Passion Fruit Species

3.5. Characterisation of Passiflora Species Through Seed Protein Profiles (SDS-PAGE)

3.6. Correlation Analysis

3.7. Principal Components Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shankar, K.; Singh, S.R.; Hazarika, B.N.; Wangchu, L.; Singh, B. (2021). Cultivated Passiflora sp. in North East region of India. Indian Hortic., 66(5), 50–52.

- Bailey, M.; Sarkhosh, A.; Rezazadeh, A.; Anderson, J.; Chambers, A.; Crane, J.H. (2021). The passion fruit in Florida: HS1406, 1/2021. Edis, 2021(1). [CrossRef]

- Thokchom, R.; Mandal, G. (2017). Production preference and importance of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis): A review. J. Agric. Eng. Food Technol., 4(1), 27–30.

- Feuillet, C. (2004). Passifloraceae (Passion flower family). In: Mori, N.; Henderson, S.A.; Stevenson, D.W.; Heald, S.D. (Eds.) Flowering plants of the neotropics; Oxford: USA, pp. 286–287.

- Ulmer, T.; MacDougal, J.M. (2004). Passiflora: Passion flowers of the world; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, p. 430.

- Fajardo, D.; Angel, F.; Grum, M.; Tohme, J.; Lobo, M.; Roca, W.M.; Sanchez, I. Genetic variation analysis of the genus Passiflora L. using RAPD markers. Euphytica 1998, 101, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, A.J.C.; Souza, M.M.; Araújo, I.S.; Corrêa, R.X.; Ahnert, D. Genetic diversity in Passiflora species determined by morphological and molecular characteristics. Biol. Plant. 2010, 54, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, A.P.; Pereira, T.S.; Pereira, M.G.; de Souza, M.M.; Maldonado, J.M.; Do Amaral Junior, A.T. (2003). Genetic diversity among yellow passion fruit commercial genotypes and among Passiflora species using RAPD. Rev. Bras. Frutic., 25, 489–493.

- Ramaiya, S.D.; Bujang, J.S.; Zakaria, M.H. Genetic Diversity inPassifloraSpecies Assessed by Morphological and ITS Sequence Analysis. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joy, P.P. (2010). Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims): Passifloraceae. Tech. Bull., Pineapple Research Sta-tion, Kerala, India.

- Aizza, L.C.B.; Sawaya, A.C.H.F.; Dornelas, M.C. (2019). Identification of anthocyanins in the corona of two species of Passiflora and their hybrid by UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Biochem. Syst. Ecol., 85, 60–67. [CrossRef]

- Reis, L.C.R.D.; Facco, E.M.P.; Salvador, M.; Flores, S.H.; De Oliveira Rios, A. (2018). Antioxidant poten-tial and physicochemical characterization of yellow, purple and orange passion fruit. J. Food Sci. Technol., 55, 2679–2691.

- Souza, L.M.D.; Ferreira, K.S.; Chaves, J.B.P.; Teixeira, S.L. (2008). L-ascorbic acid, β-carotene and lyco-pene content in papaya fruits (Carica papaya) with or without physiological skin freckles. Sci. Agric., 65, 246–250.

- Shinohara, T.; Usui, M.; Higa, Y.; Igarashi, D.; Inoue, T. (2013). Effect of accumulated minimum tem-perature on sugar and organic acid content in passion fruit. J. ISSAAS, 19(2), 1–7.

- Ramaiya, S.D.; Bujang, J.S.; Zakaria, M.H.; Kinga, W.S.; Sahrira, M.A.S. (2012). Sugars, ascorbic acid, total phenolic content and total antioxidant activity in passion fruit (Passiflora) cultivars. J. Sci. Food Agric., 93, 1198–1205. [CrossRef]

- Tjoelker, M.G.; Oleksyn, J.; Reich, P.B.; Zytkowiak, R. (2008). Coupling of respiration, nitrogen, and sugars underlies convergent temperature acclimation in Pinus banksiana across wide-ranging sites and populations. Glob. Change Biol., 14(4), 782–797. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, D.; Melgarejo, L.; Hernández, M.; Melo, S.; Fernández-Trujillo, J. Physiological and biochemical characterization of sweet granadilla (Passiflora ligularis JUSS) at different locations. Acta Hortic. 2018, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.K.; Singh, A.; Prakash, J.; Nath, A.; Deka, B.C. (2014). Physico-biochemical changes during fruit growth, development and maturity in passion fruit genotypes. Indian J. Hort., 71, 486–493.

- Joseph, A.V.; Sobhana, A.; Joseph, J.; Bhaskar, J.; Vikram, H.C.; Sankar, S.J. (2021). Performance evalu-ation of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims.) genotypes. J. Trop. Agric., 59(2).

- Loizzo, M.R.; Lucci, P.; Núñez, O.; Tundis, R.; Balzano, M.; Frega, N.G.; Conte, L.; Moret, S.; Filatova, D.; Moyano, E.; et al. Native Colombian Fruits and Their by-Products: Phenolic Profile, Antioxidant Activity and Hypoglycaemic Potential. Foods 2019, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beena, V.L.; Beevy, S.S. (2015). Genetic diversity in two species of Passiflora L. (Passifloraceae) by kary-otype and protein profiling. Nucl., 58(2), 101–106.

- Agricultural Statistics at a Glance. (2022). Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, Government of India, p. 92.

- Da Silva, M.A.P.; Placido, G.R.; Caliari, M.; Carvalho, B.S.; Da Silva, R.M.; Cagnin, C.; De Lima, M.S.; do Carmo, R.M.; Da Silva, R.C.F. (2015). Physical and chemical characteristics and instrumental colour pa-rameters of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims). Afr. J. Agric. Res., 10, 1119–1126.

- Jamir, T.; Sharma, H.; Dolui, A. Folklore medicinal plants of Nagaland, India. Fitoterapia 1999, 70, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowrey, D. (1993). Herbal tonic therapies; Keats Publishing Inc.: New Canaan, CT, USA, p. 400.

- Swaminathan, M.S. (1999). Enlarging the basis of food security. Proc. Int. Workshop on the Role of Un-derutilized Species, 17–19 February, M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai, India.

- Shankar, K.; Singh, S.R.; Annu, T. (2021a). Existence of Passiflora ligularis Juss in North Eastern Hima-layan Region of India. Res. J. Agric. Sci., 12(6), 2276–2280.

- De Jesus, O.N.; de Oliveira, E.J.; Faleiro, F.G.; TL, S.; Girardi, E.A. (2017). Illustrated morpho-agronomic descriptors for Passiflora spp.; Embrapa Mandioca e Fruticultura: Brazil.

- Collins, T.J. (2007). ImageJ for Biotechniques microscopy. Biotechniques, 43(S1), S25–S30. [CrossRef]

- Bayfield, R.; Cole, E. (1980). Colorimetric estimation of vitamin A with trichloroacetic acid. Methods Enzymol., 67, 180–195. [CrossRef]

- Ranganna, S. (1986). Handbook of analysis and quality control for fruit and vegetable products, 2nd ed.; Tata McGraw-Hill: New Delhi, India, pp. 89–90.

- Medlicott, A.P.; Reynoso, W.; Thompson, A.K. (1988). Modeling of mango ripening for prediction of optimal harvest time and maturity. Acta Hortic., 269, 215–223.

- AOAC. (2000). Official methods of analysis of AOAC International, 17th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Gaithersburg, MD, USA.

- Capocasa, F.; Scalzo, J.; Mezzetti, B. (2008). Combining quality and antioxidant content in fruit breeding. Acta Hortic., 814, 61–66.

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. (1984). Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol., 105, 121–126. [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen Peroxide is Scavenged by Ascorbate-specific Peroxidase in Spinach Chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Stein, W.H. PHOTOMETRIC NINHYDRIN METHOD FOR USE IN THE CHROMATOGRAPHY OF AMINO ACIDS. J. Biol. Chem. 1948, 176, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Dougherty, L.; Xu, K. Towards an improved apple reference transcriptome using RNA-seq. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2014, 289, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol., 15, 550. [CrossRef]

- Young, M.D.; Wakefield, M.J.; Smyth, G.K.; Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, D457–D462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Fang, L.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Li, R.; Bolund, L.; et al. WEGO: A web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W293–W297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P.; Binns, D.; Chang, H.-Y.; Fraser, M.; Li, W.; McAnulla, C.; McWilliam, H.; Maslen, J.; Mitchell, A.; Nuka, G.; et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, O.P.; More, T.A. (2009). Evaluation of different passion fruit genotypes under semi-arid region of western India. Indian J. Agric. Sci., 79, 419–421.

- Baghel, M.S.; Meena, S.R.; Meena, R.K.; Rai, D.R.; Verma, P.K.; Kumar, R. (2017). Evaluation of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims) genotypes for growth, yield and fruit quality under Delhi conditions. Indian J. Agric. Sci., 87(10), 1383–1388.

- Joseph, A.V.; Sobhana, A.; Sankar, S.J. (2015). Evaluation of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims) genotypes for yield and quality. J. Trop. Agric., 53(2), 165–168.

- Shankar, K.; Singh, S.R.; Wangchu, L.; Singh, B. (2022). Passion fruit in India: Cultivation, utilization, and future prospects. Indian Hortic., 67(2), 6–9.

- Lobo, M.; Tohme, J.; Angel, F.; Roca, W. (1996). Application of molecular markers for characterization of Passiflora germplasm. Proc. Int. Symp. Trop. Fruits, 1, 34–45.

- Muthuswamy, M.; Madanagopal, R.; Durairaj, S.; Elayabalan, S. (2021). Evaluation of superior genotypes of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims) under lower Pulney hills of Tamil Nadu. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem., 10(5), 2535–2539.

- Silva, R.F.D.; Santos, V.S.; Santos, J.M.D.; Brito, N.V.; Pessoa, R.C.D.; Oliveira, G.M.D.; Soares, A.B.; Viana, A.P. (2018). Diversity and structure of the Passiflora edulis gene pool accessed by SSR markers. Acta Sci. Agron., 40, e39373.

- Viana, A.P.; Freitas, J.C.O.; Santos, C.E.M.; Moreira, S.O.; Paiva, C.L.; Santos, E.A.; Amaral Júnior, A.T. (2021). Breeding of passion fruit: A historical overview and future perspectives. Front. Plant Sci., 12, 712228.

- Souza, M.M.; Pereira, M.G. (2006). Molecular characterization of genotypes of the genus Passiflora L. using inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers. Sci. Hortic., 111(2), 164–169.

| Species | Code | Sources | Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) | Altitude |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P1 | Andro, Manipur | 24⁰73' | 94⁰04' | 815 m |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P2 | West Imphal, Manipur | 24⁰47' | 93⁰58' | 906 m |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P3 | Sutamura, west Tripura, Tripura | 23⁰62' | 91⁰26' | 20 m |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P4 | College of Agriculture, Biswanath Cherali, Assam |

26⁰43' | 93⁰08' | 82 m |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P5 | Notun Basti, Dimapur, Nagaland | 25⁰55' | 93⁰43' | 154 m |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P6 | CHF, Pasighat, Arunachal Pradesh | 28⁰04' | 95⁰19' | 162 m |

| P. edulis Sim | P7 | Kangpokpi, Manipur | 24⁰42' | 93⁰46' | 1510 m |

| P. edulis Sim | P8 | ICAR-NOFRI, East Sikkim | 27⁰17' | 88⁰36' | 882 m |

| P. edulis Sim | P9 | Aizawl, Mizoram | 23⁰43' | 92⁰44' | 786 m |

| P. edulis Sim | P10 | CHF, Campus, Pasighat, Arunachal Pradesh | 28⁰04' | 95⁰19' | 168 m |

| P. edulis Sim | P11 | Ziro, Lower Subansiri, Arunachal Pradesh | 27⁰32' | 93⁰48' | 1566 m |

| P. edulis Sim | P12 | Pasighat, Arunachal Pradesh | 28⁰03' | 95⁰20' | 154 m |

| P. ligularis Juss | P13 | Lunghar Village, Ukhrul, Manipur | 25⁰16' | 94⁰42' | 1633 m |

| P. ligularis Juss | P14 | Sakhabama, Kohima, Nagaland |

25⁰39' | 94⁰11' | 1077 m |

| P. quadrangularis L. | P15 | Pasighat, Arunachal Pradesh | 28⁰03' | 95⁰20' | 156 m |

| Plant Part | Characters | References |

| Leaf | I.Anthocyanin content (mg/100 g) | [37] |

| II.Vitamin C content (mg/100 g) | [37] | |

| III.Phenol content (mg/100 g) | [31] | |

| IV.Chlorophyll content (mg/g) | [38] | |

| Petiole | V.Anthocyanin content (mg/100 g) | [37] |

| Tendril | VI.Anthocyanin content (mg/100 g) | |

| Fruit | VII.Vitamin C (mg/100 g) | [37] |

| VIII.Total Soluble Solids (°Brix) | Hand refractometer | |

| IX.Total carotenoid (mg/100 g) | [30] | |

| X.Total flavonoids (mg/100 g) | [31] | |

| XI.Antioxidant activity (DPPH) (%) | [32] | |

| XII.Titratable acidity (%) | [33] | |

| XIII.Total carbohydrates (%) | [34] | |

| XIV.Reducing sugar (%) | [35] | |

| XV.Non-reducing sugar (%) | [36] |

| formulation for 15% acrylamide separating gel | formulation for 5% acrylamide stacking gel | |

| Water | 6.9 mL | 5.5 mL |

| 30% Acrylamide mixture | 15 mL | 1.3 mL |

| Separating gel buffer (1.5M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8) | 7.5 mL | 1.0 mL |

| 2% SDS | 0.3 mL | 0.1 mL |

| 10% Ammonium persulphate | 0.3 mL | 0.1 mL |

| TEMED | 0.012 mL | 0.008 mL |

| Sample preparation | ||

| 0.6 M Tris-HCl | 5.0 mL | |

| 1% SDS | 0.5 g | |

| 0.5% Bromophenol blue solution | 5 mL | |

| 10% sucrose | 5.0 g | |

| Species | Code | Angle between lateral veins (°) | Leaf length (cm) | Leaf width (cm) | Petiole length (cm) | Tendril length (cm) | Length of right lateral lobe (cm) | Peduncle length (cm) | Flower length (cm) | Filament length (cm) | Stamen length (cm) | Number of flowers per node |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P1 | 63.38ab | 12.56bc | 16.07a | 2.21bc | 13.39g | 7.17a | 3.27de | 6.93d | 0.83d | 1.80abc | 1.00b |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P2 | 63.02ab | 12.21bcd | 15.56ab | 1.94cd | 12.70g | 7.03ab | 3.20de | 6.87d | 0.80d | 1.77abcd | 1.00b |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P3 | 59.70abc | 11.23cdef | 14.10bcd | 1.78de | 16.13e | 6.90b | 3.27de | 5.60i | 0.83d | 1.63abcde | 1.00b |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P4 | 63.38ab | 12.70b | 15.67ab | 2.22bc | 20.23c | 5.90de | 3.10de | 5.60i | 1.37a | 2.02a | 1.00b |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P5 | 57.21bc | 10.20f | 12.68de | 1.76de | 14.57f | 6.60c | 3.07de | 6.73d | 0.83d | 1.50bcdef | 1.00b |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P6 | 42.24d | 11.27cdef | 14.80abc | 3.02a | 22.40b | 5.80e | 3.23de | 7.40c | 0.90cd | 1.67abcde | 1.00b |

| P. edulis Sim | P7 | 58.32abc | 10.68ef | 13.24cde | 1.73de | 20.54c | 5.43g | 2.93de | 6.30e | 1.13b | 0.70h | 1.00b |

| P. edulis Sim | P8 | 57.12bc | 10.86def | 13.92bcd | 1.79de | 19.13d | 5.27h | 3.30d | 5.93fgh | 1.13b | 0.80gh | 1.00b |

| P. edulis Sim | P9 | 57.10bc | 10.66def | 13.80bcd | 1.75de | 19.11d | 5.19h | 3.27d | 5.81fgh | 1.11b | 0.78gh | 1.00b |

| P. edulis Sim | P10 | 57.97abc | 15.13a | 12.07ef | 2.49b | 22.13b | 6.00d | 5.07c | 7.73b | 0.80d | 1.12fgh | 1.00b |

| P. edulis Sim | P11 | 54.07c | 10.41f | 12.64de | 1.96cd | 20.00c | 5.40gh | 2.93de | 5.77hig | 0.67e | 1.28def | 1.00b |

| P. edulis Sim | P12 | 58.79abc | 10.42f | 13.28cde | 1.89cde | 19.20d | 5.30gh | 2.87e | 5.87fgh | 1.13b | 1.39cdef | 1.00b |

| P. ligularis Juss | P13 | 62.17ab | 14.45a | 10.51fg | 2.42b | 14.27f | 0.00i | 7.23a | 6.00f | 0.97c | 1.57abcdef | 1.67c |

| P. ligularis Juss | P14 | 63.55ab | 14.38a | 11.58ef | 1.88cde | 16.13e | 0.00i | 6.43b | 5.97fg | 0.83d | 1.97ab | 1.67c |

| P. quadrangularis L. | P15 | 64.52a | 11.95bcde | 9.44g | 1.56e | 28.13a | 0.00i | 2.40f | 9.20a | 0.83d | 1.42cdef | 2.67a |

| Species | Code | Fruit length (cm) | Fruit breadth (cm) | Fruit weight (g) | Number of fruits per vine | Fruit yield (kg per vine) | Peel weight (g) | Shelf-life (days) | Weight of 100 seeds (g) | Seed length (cm) | Seed width (cm) | Number of seeds per fruit | Seed weight per fruit |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P1 | 6.16cd | 5.33cd | 78.75b | 126.34ef | 9.94bc | 42.85b | 9.33cde | 1.17f | 0.54cd | 0.35b | 146.33bcd | 1.92ef |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P2 | 6.63bc | 6.16b | 65.1b | 138.33de | 9.01bcde | 42.32b | 8.33de | 0.90g | 0.56bc | 0.38b | 231.33a | 2.08def |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P3 | 6.16cd | 5.33cd | 69.98b | 144.00cde | 10.07bc | 43.34b | 6.33e | 1.32f | 0.54cd | 0.35b | 193.00ab | 2.54cdef |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P4 | 6.51bcd | 5.64bc | 77.69b | 118.00f | 9.15bcd | 43.29b | 7.00e | 2.00de | 0.52de | 0.37b | 166.33bcd | 3.03cd |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P5 | 5.95cd | 5.02cd | 45.18b | 128.00ef | 5.78cde | 20.59b | 11.67bcd | 1.95de | 0.52de | 0.18c | 171.00bcd | 3.27c |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P6 | 6.51bcd | 5.64bc | 77.69b | 134.92ef | 10.473b | 47.96b | 6.00e | 2.00de | 0.52de | 0.37b | 152.00bcd | 3.04cd |

| P. edulis Sim | P7 | 5.95cd | 5.02cd | 45.18b | 166.67ab | 7.56bcde | 24.59b | 10.33bcde | 2.31c | 0.51de | 0.20c | 140.00bcd | 3.23c |

| P. edulis Sim | P8 | 4.79e | 4.27ef | 32.7b | 159.67abc | 5.22de | 16.30b | 10.00bcde | 1.88e | 0.52de | 0.21c | 123.33de | 2.31cdef |

| P. edulis Sim | P9 | 4.68e | 4.21f | 31.78b | 152.67bcd | 4.85de | 15.90b | 12.00bcd | 1.85e | 0.49e | 0.19c | 87.67e | 1.61f |

| P. edulis Sim | P10 | 6.16cd | 5.33cd | 33.08b | 161.33abc | 5.35de | 16.17b | 9.33cde | 2.17cd | 0.54cd | 0.35b | 146.33bcd | 3.15cd |

| P. edulis Sim | P11 | 5.69d | 4.86de | 43.89b | 157.67abc | 6.95bcde | 22.86b | 9.83bcde | 2.16cd | 0.52de | 0.22c | 136.33cde | 2.97cde |

| P. edulis Sim | P12 | 5.72d | 4.89de | 43.99b | 174.67a | 7.68bcde | 22.23b | 13.00bc | 2.18cd | 0.51de | 0.20c | 141.67bcd | 2.92cde |

| P. ligularis Juss | P13 | 7.17b | 5.38cd | 53.41b | 86.67g | 4.62e | 32.31b | 14.00b | 3.20b | 0.60b | 0.17c | 164.33bcd | 5.27b |

| P. ligularis Juss | P14 | 7.16b | 5.36cd | 53.23b | 87.33g | 4.67e | 31.94b | 12.00bcd | 3.20b | 0.60b | 0.17c | 180.33bc | 5.25b |

| P. quadrangularis L. | P15 | 14.48a | 9.30a | 496.67a | 52.33h | 26.23a | 360.00a | 27.33a | 5.45a | 0.79a | 0.62a | 172.33bcd | 9.37a |

| Species | Genotypes | Vit C (mg g-1) | Total soluble solids (⁰Brix) | Total carotenoid (mg g-1) | Total flavonoids (mg g-1) | Antioxidant activity (DPPH) (%) | Titratable Acidity (%) | Total carbohydrate (%) | Reducing sugar (%) | Non-reducing Sugar (%) | Fruit juice content (mL/fruit) |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P1 | 0.238bcd | 16.17d | 0.100hi | 0.114def | 10.85cde | 3.56ab | 10.14de | 4.92cdef | 5.20abcd | 34.17b |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P2 | 0.26.1abc | 15.97d | 0.090ij | 0.113def | 11.70bcd | 3.91a | 11.14abcd | 4.63defg | 6.54a | 20.70bcd |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P3 | 0.262abc | 15.13e | 0.116h | 0.09ef | 12.93bcd | 3.41abc | 12.12ab | 4.93cdef | 5.79abc | 24.09bcd |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P4 | 0.262abc | 16.03d | 0.08.7ij | 0.11def | 11.48bcd | 3.32bc | 10.31cde | 4.10fg | 6.52a | 31.35bc |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P5 | 0.265abc | 18.13a | 0.300c | 0.35a | 22.15a | 1.15gh | 10.84bcd | 6.88a | 4.72abcd | 21.31bcd |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P6 | 0.214cd | 17.53c | 0.077j | 0.16cde | 12.50bcd | 2.43e | 7.81f | 4.35efg | 3.05d | 34.20b |

| P. edulis Sim | P7 | 0.292ab | 18.07a | 0.265f | 0.11def | 11.96bcd | 2.78de | 12.36ab | 6.36ab | 6.28ab | 17.35d |

| P. edulis Sim | P8 | 0.226cd | 18.28a | 0.397a | 0.24bc | 12.60bcd | 2.59e | 10.59bcd | 6.92a | 3.42cd | 14.09d |

| P. edulis Sim | P9 | 0.207cd | 17.94ab | 0.196g | 0.07g | 9.80def | 2.52e | 12.06abc | 5.54bcd | 5.99abc | 10.94d |

| P. edulis Sim | P10 | 0.214cd | 17.27c | 0.240b | 0.26b | 14.76b | 3.19bcd | 12.88a | 5.98abc | 6.40ab | 13.75d |

| P. edulis Sim | P11 | 0.320a | 14.70ef | 0.285e | 0.10ef | 13.70bc | 2.91cde | 12.18ab | 6.41ab | 5.96abc | 18.14cd |

| P. edulis Sim | P12 | 0.177de | 17.53bc | 0.145d | 0.20bcd | 10.33cdef | 1.20g | 10.14de | 5.35bcde | 3.86bcd | 18.78cd |

| P. ligularis Juss | P13 | 0.134e | 14.43f | 0.0001k | 0.11ef | 7.52efg | 0.64h | 8.41f | 3.51g | 4.25abcd | 16.77d |

| P. ligularis Juss | P14 | 0.127e | 14.64bc | 0.0001k | 0.11def | 7.17fg | 0.63h | 8.80ef | 4.03fg | 4.50abcd | 16.77d |

| P. quadrangularis L. | P15 | 0.308a | 13.54g | 0.0172k | 0.17cde | 6.28g | 1.81f | 10.32cde | 5.52bcde | 4.92abcd | 117.92a |

| Species | Genotypes | Leaf Vit. C (mg g-1) | Leaf Phenol (mg g-1) | Leaf chlorophyll (mg g-1) | Petiole anthocyanin (µg g-1) | Tendril anthocyanin (µg g-1) |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P1 | 1.151cd | 1.538h | 2.84ab | 20.30bcde | 28.90ab |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P2 | 1.1807c | 1.527h | 2.90a | 18.60cde | 33.90a |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P3 | 0.981de | 1.432h | 1.56de | 30.50ab | 26.90abc |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P4 | 1.218c | 1.795g | 1.50de | 15.70def | 19.80abcd |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P5 | 1.748a | 1.942g | 1.87cde | 28.10abc | 21.40abcd |

| P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg | P6 | 1.256c | 1.798g | 1.16e | 9.30ef | 24.50abcd |

| P. edulis Sim | P7 | 1.172cd | 2.709e | 2.16bcd | 19.0cde | 31.40ab |

| P. edulis Sim | P8 | 1.101cd | 2.813de | 1.57de | 35.40a | 21.10abcd |

| P. edulis Sim | P9 | 1.183c | 2.242f | 1.64cde | 05.90f | 20.40abcd |

| P. edulis Sim | P10 | 489g | 4.985a | 2.60ab | 10.10def | 31.10ab |

| P. edulis Sim | P11 | 1.258c | 2.968cd | 1.32e | 4.30f | 14.10bcd |

| P. edulis Sim | P12 | 1.500b | 3.059c | 2.38abc | 5.90f | 06.70d |

| P. ligularis Juss | P13 | 0.882ef | 3.108c | 1.23e | 21.50bcd | 26.40abc |

| P. ligularis Juss | P14 | 0.752f | 3.113c | 1.10e | 20.40bcde | 16.0abcd |

| P. quadrangularis L. | P15 | 0.493g | 3.489b | 1.65cde | 17.80cde | 09.30cd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).