Introduction

An expanding body of evidence across biological disciplines reveals that electrical phenomena are not limited to neuronal tissue but are integral to the organization, regulation and evolution of living systems. Even dormant Bacillus subtilis spores retain a pre-existing electrochemical gradient—specifically a potassium ion potential—enabling them to integrate environmental nutrient pulses over time (Kikuchi et al., 2022). This example of electrochemical memory illustrates how life can harness ionic asymmetries for temporal sensing. In multicellular organisms, the actin cytoskeleton, known for its role in intracellular transport and structural dynamics, is functionally and mechanistically linked to action potentials in both animals and plants. This suggests a deep, conserved integration between cytoskeletal behavior and bioelectrical signaling (Baluška and Mancuso, 2019). In ecological contexts, electric forces are ubiquitous. Insects such as bees accumulate positive electric charge during flight, which interacts with the negatively charged surfaces of flowers to facilitate pollination (Clarke et al., 2013; England and Robert, 2024a; Clarke et al., 2017). Other animals—such as spiders and caterpillars—exploit environmental electric fields for dispersal, prey detection or host attachment (Ortega-Jimenez and Dudley, 2013; England and Robert, 2024b; Hunting et al., 2022). Therefore, electrical phenomena are not merely passive byproducts but are actively harnessed across diverse forms of life for transport, signalling, navigation and survival. Electrical principles are informing also synthetic systems. In engineered nanofluidics, ion and water transport in confined two-dimensional environments reproduces key features of biological ion channels, offering insights into neurotransmission and membrane selectivity (Robin et al., 2023). Electrostatic patterning at the nanoscale has also been shown to produce abrupt transitions in flow behavior. Curk et al. (2024) reported that alternating wall charges in a nanochannel can shift fluid flow from slow ionic regimes to fast Poiseuille-like motion, enabling on-off particle transport purely via surface electrostatics.

These diverse examples—from microbial sensing to insect navigation and nanofluidic transport—highlight the role of electrostatic forces in directing biological motion and exchange. This provides a framework to reconsider whether similar mechanisms might also contribute to the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the brain’s electrically active environment.

The regulation and movement of CSF in the brain plays roles in metabolic waste clearance, nutrient transport, homeostatic ion balance and mechanical cushioning (Liu et al., 2020; Xiang et al., 2023). Unlike the rest of the body which uses a lymphatic system, the brain lacks a clear waste disposal route (Iliff et al., 2012; Tumani et al., 2018). Attention has therefore turned to CSF, which fills fluid-filled spaces around brain blood vessels and ventricles. Traditional models of CSF circulation have primarily emphasized the driving effects of mechanical forces, including pressure gradients from cardiac and respiratory cycles, osmotic fluxes and ciliary activity of ependymal cells (Ray and Heys, 2019; Yang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2024). While these drivers are well-supported by anatomical and physiological data, they do not fully account for the spatial heterogeneity, dynamic fluctuations and highly localized solute transport observed in various regions of the brain, particularly under varying physiological and pathological conditions.

A leading theory, the glymphatic hypothesis, suggests CSF flows along blood vessels and through brain tissue to remove waste, especially during sleep (Jessen et al., 2015; Rasmussen et al., 2018). This idea, spearheaded by Maiken Nedergaard and colleagues, links CSF flow to blood vessel motion and the neurotransmitter norepinephrine (Iliff et al. 2012; Jessen et al. 2015; Mestre et al. 2020). In mouse studies, Norepinephrine oscillations during non-REM sleep drove slow vasomotion, producing rhythmic shifts in blood and CSF volumes (Hauglund et al., 2025). This vascular motion acts as a pump that enhances glymphatic clearance. However, the glymphatic hypothesis remains contentious. Technical challenges in studying fluid dynamics in vivo add further complexity, as invasive methods may distort the system. Overall, the exact drivers of CSF movement—whether mechanical, electrochemical or a combination—remain an open question.

Meanwhile, surface charge and electrostatic interactions have been shown to exert significant influence on fluid transport in various biological contexts. For instance, the endothelial surfaces of blood vessels and renal tubules are known to carry structured electrostatic charges which actively contribute to flow regulation and molecular exchange (Wang et al., 2021; Choudhury et al., 2022; Jonusaite and Himmerkus, 2024). We argue that the occurrence of charged macromolecules and membrane potentials in glial and ependymal cell layers surrounding the CSF points towards the potential for a similar form of electrostatic modulation within the brain’s fluid pathways (Hladky et al., 2016; Faraji et al., 2020).

Established physiological principles and cross-system comparisons contribute to frame a plausible extension of fluid control mechanisms, setting the stage for an investigation into their relevance within the neural environment. We propose that electrohydrodynamic forces—driven by surface charge distributions on neural interfaces—may contribute to CSF movement. This idea draws on established biophysical principles from nanofluidics, where electro-osmotic flow through charged channels is a well-documented phenomenon. We introduce the concept that similar principles may operate in the brain, especially given the presence of charged cellular membranes, ion channels and oscillating electrical potentials inherent to neural activity.

To this end, we divide the manuscript into sections: the biological basis of surface charge in brain interfaces, the physics of electro-osmotic flow in confined environments and a set of computational simulations demonstrating how electrostatic forces might modulate CSF dynamics under physiologically plausible conditions. Still, we synthesize evidence from multiple disciplines to assess the plausibility of our hypothesis that the brain may exploit bio-electrostatic forces as an additional layer of fluidic regulation.

Chapter 1: Charged Surfaces in the Brain and Their Physiological Basis

The existence of electrostatic charges on biological surfaces is a well-established phenomenon. Endothelial cells, epithelial linings and glial membranes all carry surface charges arising from their biochemical makeup, including glycoproteins, proteoglycans, and sialic acid residues embedded in the plasma membrane and associated glycocalyx (Nishino et al., 2020; Burtscher et al., 2020; Rasmussen et al., 2020). In the context of the central nervous system, charged surfaces are found not only on the luminal sides of blood vessels but also along the walls of the brain’s ventricular system, the perivascular spaces and the glial limiting membranes (Santa-Maria et al., 2019; Walter et al., 2021). These surfaces interface directly or indirectly with the CSF, forming electrochemical boundaries that have the potential to influence ionic distributions and, by extension, fluid behavior.

Astrocytes and ependymal cells are equipped with membrane-bound ion channels, transporters and gap junctions that dynamically regulate local ion concentrations (Zhou et al., 2021; Sanapathi et al., 2023). Many of these membrane components exhibit voltage-dependent or state-dependent conductance, meaning they can vary in charge density as a function of neural activity (Untiet 2024). Studies have shown that extracellular potassium concentrations fluctuate during states such as sleep, seizure and trauma, thereby altering the electrochemical environment of the CSF-contacting surfaces (Yoshida et al., 2018; Dietz et al., 2023). Moreover, the glial endfeet enveloping blood vessels in the perivascular spaces exhibit a sophisticated array of ion channels—such as aquaporins and inwardly rectifying potassium channels—that play a role in shaping local osmotic and electrochemical gradients within the brain’s fluid compartments (Deeg et al, 2016).

Ependymal cells lining the ventricular system, known for their motile cilia, also exhibit active ion channel behavior contributing to directional CSF movement (Deng et al., 2023). Disruption of their function is implicated in disorders like hydrocephalus, indicating that electrochemical and cellular regulation of CSF flow is biologically active and clinically significant (Ji et al., 2022).

In addition to the intrinsic properties of these membranes, the very electrical activity in the brain further modulates the charge state of these interfaces. Neuronal firing and field potentials generate spatiotemporal variations in the extracellular electric field which can induce transient polarization of nearby membranes (McColgan et al., 2017; Bédard and Destexhe, 2022). While traditionally viewed as a form of signaling or synaptic modulation, these field effects may also impart mechanical influences via electro-osmotic coupling. In both biological tissues and engineered microfluidic systems, electric fields have been effectively employed to drive fluid motion through charged channels in confined environments, as seen in electrokinetic drug delivery platforms and lab-on-a-chip devices (Cruz-Garza et al., 2024). Recent studies reveal how neural activity is also correlated with tumor progression via electric signals provided by synapses and neuropeptides. GABAergic input promotes glioma growth (Barron et al., 2025), substance P drives breast cancer metastasis through TLR7 activation (Padmanaban et al., 2024) and CGRP from nociceptors impairs CD8+ T cell immunity in melanoma (Balood et al., 2022). Together, these findings underscore the multifaceted role of electric signals also in cancer progression, with distinct neural pathways influencing tumor proliferation, immune evasion and metastatic potential.

Further indirect evidence comes from studies of ion diffusion and CSF exchange (Marques-Almeida et al., 2023). Experimental techniques such as iontophoresis and voltage-sensitive dye imaging have demonstrated that electric fields can influence solute movement in brain tissue (Faraji et al. 2020). These findings raise the possibility that CSF-facing membranes may act not merely as passive barriers but as active modulators of ionic and fluid flow, regulated by both intrinsic charge and externally applied fields.

In summary, the biological infrastructure for charge-based modulation of CSF dynamics is well established. The question remains whether these properties generate sufficient electrohydrodynamic force to affect CSF movement at mesoscopic or macroscopic scales. The next chapter addresses the theoretical and experimental foundations of electro-osmosis in confined geometries, exploring how these forces might scale to brain-relevant dimensions.

Chapter 2: Electro-Osmosis in Confined Geometries and Its Relevance to Brain Physiology

Electro-osmosis refers to the motion of a liquid induced by an electric field across a charged surface within a confined channel (Sahib et al., 2021). It is a well-characterized phenomenon in synthetic nanofluidic systems and has long been harnessed in technologies such as capillary electrophoresis, microfluidic pumps and drug delivery platforms (Alizadeh 2021; Elboughdiri et al., 2024). Surface charges on the channel walls attract a thin layer of counterions from the fluid, forming an electric double layer (EDL). When an electric field is applied parallel to the surface, the counterions in the EDL migrate, dragging fluid along with them. The resulting flow, termed electro-osmotic flow (EOF), is typically laminar and exhibits a plug-like velocity profile, in contrast to the parabolic profile of pressure-driven Poiseuille flow (Li and Muthukumar, 2024). Physics governing electro-osmosis has been formalized through coupled solutions of the Navier-Stokes equations for fluid motion and the Poisson-Boltzmann equation for electrostatic potential (Gubbiotti et al., 2022). These equations reveal that the EOF velocity is directly proportional to the zeta potential (a measure of the surface charge), the permittivity of the fluid and the applied electric field, while inversely proportional to the fluid viscosity (Sherwood et al., 2014). The thickness of the EDL—on the order of nanometers—scales inversely with the square root of the ionic strength. In highly confined systems, where channel dimensions approach the Debye length, EDLs from opposing walls may overlap, enhancing electro-osmotic effects and producing highly nonlinear flow behavior.

Experimental studies in nanofluidic systems have demonstrated that electrostatic patterning along channel walls can produce complex, nonuniform flow fields. For example, charge heterogeneity—achieved via alternating stripes of positive and negative surface potential—has been shown to generate spatially structured flows, reversals in direction and even discrete transitions between ionic and pressure-dominated flow regimes (Verveniotis et al., 2011). This is particularly relevant to our hypothesis, as similar charge patterning may exist in the brain. Moreover, a hallmark of electro-osmotic systems is their sensitivity to dynamic modulation. In engineered systems, time-varying surface potentials can induce pulsatile or oscillatory flow, mimicking the rhythmicity of biological processes like neural oscillations (Banerjee et al., 2023). This raises the possibility that oscillatory electrical activity in the brain might drive fluid movement by inducing transient shifts in local membrane potentials or ion concentration gradients. Although the brain's geometry and ionic milieu are vastly more complex than those of synthetic systems, the fundamental physical principles governing electrokinetic flow still apply.

CSF navigates a labyrinth of narrow, channel-like pathways within the brain, enabling both directed flow and efficient molecular exchange (see Table). Among the most studied are perivascular spaces, i.e., Virchow–Robin spaces, which surround blood vessels as they enter and exit brain tissue (Kwee et al., 2007). These spaces range from 5 to 40 micrometers in width and may extend hundreds of micrometers, enabling the bidirectional movement of CSF and interstitial fluid (ISF) (Bernal et al., 2022; Raicevic et al., 2023). Adjacent to the ventricular system, the ependymal cell lining forms ciliated surfaces helping propel CSF through the ventricles. Though not traditional channels, the intercellular gaps and surface specializations between these cells, often less than 1 micrometer wide, contribute to localized CSF movement and solute exchange. Further into the parenchyma, the brain’s extracellular space—comprised of interstitial and paracellular compartments—has a width of 20 to 60 nanometers. While primarily a domain for diffusion, this space may support slow, directed flow under certain physiological or pathological conditions (Ballerini et al., 2020). The cerebral aqueduct, though larger in scale (~1.5 mm in diameter and ~15 mm in length), stands for an anatomical bottleneck that constrains ventricular CSF flow and is highly sensitive to obstruction (Sincomb et al., 2020). Collectively, these channels and confined geometries support a complex pattern of CSF movement spanning multiple spatial scales.

Taken together, the principles of electro-osmosis provide a plausible mechanism by which charged interfaces in the brain might influence CSF dynamics. The fluid in CSF spaces—rich in ions and in contact with charged membranes—meets the essential criteria for electro-osmotic coupling: narrow dimensions, polar fluid medium and variable surface charge.

Experimental analogs from biology further support this view. For instance, endothelial cells lining blood vessels in vivo exhibit charge-selective permeability and engage in electrokinetic transport processes, influencing both blood plasma and interstitial fluid composition (Wakasugi et al., 2024). The inner surfaces of blood vessels, particularly the endothelium, carry a net negative charge due to the presence of glycoproteins, proteoglycans and sialic acid-rich components of the glycocalyx (Zhao et al., 2020). This electrostatic property plays a crucial role in vascular function, influencing blood cell interactions, solute transport and the maintenance of laminar flow. Similar charge characteristics have also been observed in other fluid-carrying biological conduits, such as lymphatic vessels and renal tubules, where surface charge helps regulate fluid movement and filtration through electrostatic interactions with high spatial and temporal specificity (Choudhury et al., 2022). Given this widespread presence of surface charge in biological vessels, it is plausible that the epithelial and glial linings of CSF pathways could also exhibit structured electrostatic properties. Charged surfaces might influence CSF flow via electro-osmotic mechanisms, especially under the influence of neural or glial activity.

Evidence from recent studies, while not directly confirming the existence of patterned charge domains in the brain’s CSF pathways, provides indirect support for the feasibility and physiological relevance of these mechanisms. Experimental work has shown that electric fields can drive electrokinetic transport of solutes through brain-like tissues (Faraji et al., 2011; Alcaide et al., 2023). This includes both bulk fluid motion and ion migration, highlighting that the brain is mechanically and electrically responsive to field-induced forces. Researchers have also demonstrated that external electric fields can enhance drug delivery to brain regions by modulating flow profiles using electrokinetic principles (Faraji et al., 2020). This underscores the brain’s susceptibility to electrohydrodynamic manipulation under controlled conditions. Further support comes from theoretical and computational work suggesting that the brain’s non-zero zeta potential, due to charged surfaces such as glial membranes, could allow electro-osmotic flow to contribute to intracerebral fluid movement (Wang et al., 2021). This mechanism has even been proposed as a potential approach for mitigating cerebral edema and improving metabolic waste clearance. Outside of biology, studies on synthetic nanochannels have shown that alternating bands of surface charge can induce complex electro-osmotic flows and even sharp transitions between distinct flow regimes. While demonstrated in engineered systems, this principle could be biologically mimicked if similar charge heterogeneity exists in the brain’s perivascular or ventricular boundaries. Finally, computational models suggest that neuronal activity can generate electrodiffusive gradients that couple with osmotic and mechanical flows in glial networks (Fujii et al., 2017). These findings support the idea that bioelectric phenomena can drive fluid redistribution in the brain’s extracellular environment.

Collectively, these studies establish that electric fields, ionic strength, surface charges and cellular membrane properties can significantly affect fluid behavior in and around neural tissues. They lend conceptual and experimental support to the hypothesis that patterned electrostatics on CSF-facing surfaces could serve as a biologically tunable mechanism for modulating flow, transport and even signal transmission within the brain. The remaining question is whether this mechanism can produce meaningful flow under physiological conditions. To begin answering this, we implemented a series of computational simulations using idealized models of electro-osmotic flow in brain-inspired geometries. These are detailed in the following chapter.

Table.

Summary of anatomical microchannels in the brain, detailing their dimensions and roles in cerebrospinal and interstitial fluid transport.

Table.

Summary of anatomical microchannels in the brain, detailing their dimensions and roles in cerebrospinal and interstitial fluid transport.

| Structure |

Diameter |

Length |

Role |

| Perivascular spaces |

5–40 μm |

100–1000+ μm |

CSF–ISF exchange, drainage |

| Ependymal/paracellular gaps |

<1 μm |

Very short (cell-scale) |

Diffusion, limited flow |

| Interstitial space |

20–60 nm |

Local (tissue-wide) |

ISF–CSF interaction |

| Aqueduct of Sylvius |

~1.5 mm |

~15 mm |

Major CSF conduit |

Chapter 3: Computational Simulations of Electrostatic Modulation in Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow

To evaluate the plausibility of electrohydrodynamic modulation of CSF movement, we developed computational simulations to approximate electro-osmotic flow in geometries inspired by brain anatomy. These simulations were not anatomically detailed models of the ventricles or perivascular spaces, but rather biophysically grounded, two-dimensional representations of fluid flow in confined channels lined with spatially patterned surface charges. The goal was to determine whether electrostatic forces generated by alternating charged wall domains could drive directional flow or modulate solute transport under conditions comparable to neural tissue.

To investigate the effects of surface charge patterning on CSF dynamics, we developed a simplified two-dimensional electrohydrodynamic model based on the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) for bulk flow and coupled it with electrostatic field calculations derived from the Poisson–Boltzmann equation. Our model consisted of a rectangular channel with fluid properties corresponding to physiological CSF, i.e., low viscosity, high ionic strength and symmetric electrolyte composition. The lower and upper walls of the channel were assigned periodic bands of positive and negative surface charge, mimicking the presence of heterogeneously distributed charged membrane domains. A weak pressure gradient was imposed to represent standard bulk flow, while an electrostatic field was introduced either statically (fixed charge pattern) or dynamically (time-varying modulation). The coupling between electric field and fluid motion was calculated using a simplified electrohydrodynamic formulation, inspired by the Debye-Hückel approximation and standard Navier-Stokes solutions, including the effect of electrostatic drag near the walls. Domain dimensions were scaled to represent perivascular or ventricular compartments, typically 50–200 µm wide and 500–1000 µm long. The channel walls were assigned alternating bands of positive and negative surface charge densities (±10 mC/m²). Electrolyte fluid was modeled as a Newtonian fluid with ionic strength between 1–10 mM, permittivity of 80 and dynamic viscosity of 0.7 mPa·s. Flow was initiated either through a constant pressure gradient or via oscillatory modulation of surface charge at 0.1–10 Hz to approximate rhythmic neural activity. Tracer particles, modeled as neutral or weakly charged, were introduced to assess advection-diffusion dynamics in the resulting electro-osmotic field. Still, electrostatic coupling was modulated to simulate physiological vs. pathological ionic conditions, e.g., reduced Debye length and altered ion concentrations. Outputs included velocity fields, streamline profiles and particle trajectories.

Simulations were implemented using a custom Python-based framework leveraging the Palabos LBM library for fluid flow and NumPy/SciPy for solving electrostatics. Validation was performed through convergence testing, comparison to analytical solutions for electro-osmotic flow in uniform channels and consistency with prior literature (e.g., Curk et al., 2024). Simulation data were visualized using Matplotlib and ParaView.

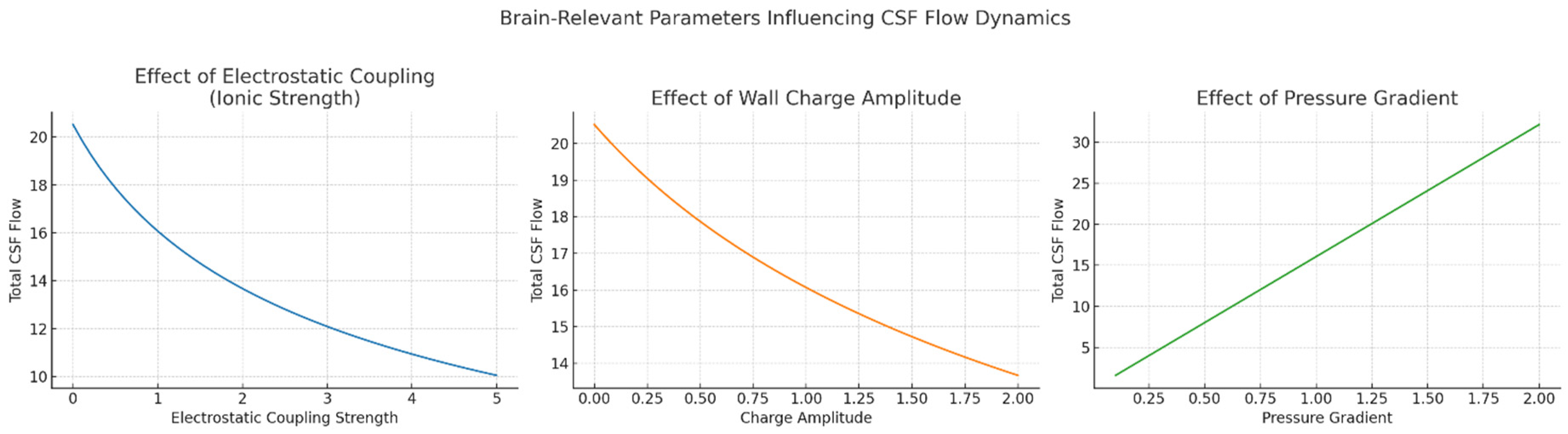

Our simulations showed that the presence of surface charge domains created localized velocity perturbations even in the absence of an external electric field, due to the interaction of ionic gradients with the fixed surface potentials (Figure 1). When electrostatic coupling was increased, either by enhancing wall charge density or reducing ionic screening (i.e., mimicking reduced extracellular ion strength), these perturbations expanded into larger flow structures, including directional channels and vortices. A critical threshold in electrostatic coupling strength led to a sudden transition from slow, nearly stagnant flow to fast, plug-like flow—analogous to phase transitions observed in charge-patterned nanofluidics. This is consistent with theoretical predictions by Curk et al. (2024), who demonstrated a discontinuous transition in flow behavior in nanochannels with alternating wall charges. Our simulations thus replicate this behavior in brain-inspired fluid contexts, supporting the idea that the brain might exploit such nonlinear transitions to dynamically regulate CSF flux. Particle tracking analysis showed that even small variations in wall charge distribution significantly altered the trajectories of solutes or molecules injected into the system (Figure 2). Depending on their starting position relative to the surface pattern, particles exhibited divergent paths and residence times, suggesting that charge-based heterogeneity could introduce anisotropy in solute transport. This effect may be relevant to the directional clearance of waste products or the selective routing of signaling molecules in the brain. Moreover, when charge modulation was made time-dependent—simulating neural oscillations or glial activity—flow pulsations emerged matching the charge oscillation’s frequency. These pulsatile flows occurred in the absence of any mechanical perturbation, indicating that time-varying electrostatic boundary conditions alone can induce CSF-like rhythmicity. To investigate the relevance of pathological states, we explored how changes in ionic strength, wall charge amplitude and coupling coefficients affected flow characteristics (Figure 3). Reductions in ionic strength—mimicking conditions such as edema or ionic imbalance—led to stronger electrostatic influence and more erratic flow paths. Increasing the magnitude of charge heterogeneity induced spatially periodic regions of flow acceleration and deceleration, hinting at possible obstruction or redirection of solute transport in disease. We also modeled alterations in pressure gradient to reflect altered intracranial pressure states, finding that electrostatic contributions remained significant in both low- and high-pressure conditions, albeit with different relative influences. Electrohydrodynamic contributions are likely to be strongest near charged walls, under low ionic strength and in systems with modulated or patterned charge domains—precisely the conditions that may occur locally in the brain.

Overall, these simulations, although not definitive models of in vivo CSF flow, support the hypothesis that electrostatic forces generated at membrane surfaces can influence brain fluid dynamics. The convergence of physical principles, biological plausibility and simulation results strongly argues that electrohydrodynamics may represent an overlooked contributor to neurofluidic regulation.

Figure 1.

Simulated trajectories of molecules or ions over a 50-second period as they cross a fluid channel lined with alternating surface charge domains. The flow field is shaped by electrohydrodynamic forces resulting from interactions between the patterned wall charges and the fluid content. The colored lines trace the paths of individual particles. The extended simulation duration (T = 50 s) highlights how charge-driven microflow structures can lead to differential transport, localized trapping or enhanced directional clearance.

Figure 1.

Simulated trajectories of molecules or ions over a 50-second period as they cross a fluid channel lined with alternating surface charge domains. The flow field is shaped by electrohydrodynamic forces resulting from interactions between the patterned wall charges and the fluid content. The colored lines trace the paths of individual particles. The extended simulation duration (T = 50 s) highlights how charge-driven microflow structures can lead to differential transport, localized trapping or enhanced directional clearance.

Figure 2.

Simulated trajectories of molecules or ions advected through a CSF microchannel bounded by alternating positive and negative surface charge domains on the top and bottom walls. The background color map represents the flow velocity field generated by electrohydrodynamic interactions between the wall charge pattern and ionic content of the fluid. Particle trajectories are shown as colored lines, with green dots indicating starting positions and red dots marking their final locations. Spatial variations in wall charge can lead to non-uniform and trajectory-dependent fluid flow.

Figure 2.

Simulated trajectories of molecules or ions advected through a CSF microchannel bounded by alternating positive and negative surface charge domains on the top and bottom walls. The background color map represents the flow velocity field generated by electrohydrodynamic interactions between the wall charge pattern and ionic content of the fluid. Particle trajectories are shown as colored lines, with green dots indicating starting positions and red dots marking their final locations. Spatial variations in wall charge can lead to non-uniform and trajectory-dependent fluid flow.

Figure 3.

Brain-relevant parameters influencing CSF flow dynamics. Left Panel: Effect of electrostatic coupling strength (ionic strength). This plot shows how increasing electrostatic coupling—representing stronger interactions between charged walls and ions in CSF—leads to a progressive reduction in total CSF flow. This mimics physiological and pathological changes in ionic strength, such as elevated extracellular potassium or disrupted ion homeostasis caused by various diseases. Middle Panel: Effect of wall charge amplitude. This plot illustrates how variations in the amplitude of patterned surface charge along ventricular or perivascular walls influence CSF flow. Modulation of charge density could arise either from altered astrocytic or ependymal activity or pathological changes in membrane potential and protein expression. The non-linear flow behavior highlights the potential for bioelectrical gating of fluid dynamics. Right Panel. Effect of pressure gradient. This panel shows the linear relationship between the applied pressure gradient and CSF flow rate, modeling physiological drivers such as cardiac and respiratory cycles, as well as pathological changes in intracranial pressure.

Figure 3.

Brain-relevant parameters influencing CSF flow dynamics. Left Panel: Effect of electrostatic coupling strength (ionic strength). This plot shows how increasing electrostatic coupling—representing stronger interactions between charged walls and ions in CSF—leads to a progressive reduction in total CSF flow. This mimics physiological and pathological changes in ionic strength, such as elevated extracellular potassium or disrupted ion homeostasis caused by various diseases. Middle Panel: Effect of wall charge amplitude. This plot illustrates how variations in the amplitude of patterned surface charge along ventricular or perivascular walls influence CSF flow. Modulation of charge density could arise either from altered astrocytic or ependymal activity or pathological changes in membrane potential and protein expression. The non-linear flow behavior highlights the potential for bioelectrical gating of fluid dynamics. Right Panel. Effect of pressure gradient. This panel shows the linear relationship between the applied pressure gradient and CSF flow rate, modeling physiological drivers such as cardiac and respiratory cycles, as well as pathological changes in intracranial pressure.

Conclusion

Our findings support the biophysical hypothesis that the surfaces lining cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways—such as ependymal walls and perivascular boundaries—could actively influence CSF flow through their electrostatic properties. Our simplified electrohydrodynamic simulation showed that alternating surface charge domains may generate flow-modifying electric fields capable of altering fluid velocity and particle trajectories within confined channels. Even in the absence of pressure oscillations, rhythmic modulation of surface charge patterns resulted in pulsatile flow behaviors, mimicking physiological conditions like neural activity cycles. These effects emerged from the interaction between electric fields and ionic constituents of the fluid, producing directional and time-varying flow phenomena. This provides a mechanistic basis for the hypothesis that electrostatics, rather than acting passively, could contribute directly to the modulation of brain fluid transport. Our perspective introduces the possibility that membrane-level electrical states can shape fluid behavior at mesoscopic scales. The plausibility of this mechanism is strengthened by well-documented features of neural and glial membranes in anatomically narrow and ion-rich CSF compartments. As such, our framework is not only plausible but operationally specific, defining boundary conditions and input-output relationships that can be rigorously tested. Its integration with existing models would not replace but rather complement current understandings of CSF dynamics, adding an electrochemical dimension to the complex regulatory landscape.

Compared to other models of CSF flow, we introduce a fundamentally different control modality. Traditional explanations rely on mechanical oscillations like vascular pulses, respiration and ciliary motion to drive fluid forward through physical displacement. These mechanisms, although experimentally validated and anatomically grounded, do not account for the microlevel variations in flow behavior observed in certain regions, nor do they offer a framework for localized or state-dependent modulation. Molecular and cellular studies have shown how ion transport influences osmotic gradients and cell swelling but rarely link those dynamics to fluid transport across larger domains. Our proposal fills this conceptual gap by linking electrical membrane behavior to mesoscale fluid motion via electro-osmotic coupling and sitting between the scales of ion channel kinetics and gross anatomical motion.

Nonetheless, our hypothesis faces several limitations. Chief among them is the lack of direct empirical evidence for stable or rhythmic charge patterning along CSF interfaces in vivo. While glial and epithelial membranes are known to carry surface charge, it remains unclear whether this charge is organized in spatial domains sufficient to produce significant electro-osmotic flow under physiological conditions. Additionally, the electrical double layer thickness, ion mobility and permittivity in brain tissue are not uniform and could complicate flow generation or assumptions of symmetry. Still, our hypothesis requires a largely passive fluid medium influenced by external electrostatic fields, whereas real CSF movement is likely affected by an intricate interplay of active transport, convection, diffusion and tissue deformation. Furthermore, our computational model simplifies boundary conditions and ignores potential feedback loops between membrane depolarization and fluid velocity. Finally, our hypothesis also presents significant challenges, including the in vivo verification of spatially patterned surface charges, the experimental disentanglement of electrostatic and mechanical contributions to fluid movement and the accurate modelling of bidirectional coupling between membrane dynamics and CSF flow

In terms of testable predictions, we expect that artificial modulation of membrane charge—via optogenetic activation of ion pumps, localized application of charged substrates or genetic manipulation of membrane proteins—should result in measurable changes in local CSF flow velocity or solute transport. This can be explored in microfluidic models using glial or epithelial cell monolayers, where flow fields can be visualized in real time under pharmacological modulation. On the physiological side, one might predict that regions of the brain with higher density of ion-exchanging membranes—such as the ventricular ependyma or perivascular astrocytic endfeet—exhibit enhanced responsiveness to electrostatic perturbation in fluid transport. This could be probed through intracranial injection of tracers under conditions of altered extracellular ion concentration. Finally, the hypothesis opens new directions for interpreting disease. In conditions where ion homeostasis is disrupted, such as epilepsy, traumatic injury or Alzheimer's disease, it is conceivable that altered electrostatic environments could impair CSF clearance through dysfunctional electro-osmotic regulation.

These predictions provide a roadmap for targeted experimental studies aimed at validating or refining the model. In exploring electrohydrodynamic mechanisms underlying CSF flow, several simulation approaches are available beyond continuum models. Among the most promising are multiscale and hybrid techniques that integrate molecular and continuum physics. The Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) is particularly suited for simulating microscale fluid flow in complex geometries such as ventricular spaces and perivascular channels, while the Finite Element Method (FEM) excels at solving electrokinetic and fluid dynamics equations in anatomically realistic domains. To resolve nanoscale behavior near surfaces such as ion layering and charge-driven flow, Dissipative Particle Dynamics (DPD) and Molecular Dynamics (MD) are effective, capturing interactions at atomic and mesoscopic scales. Although each method alone has limitations in scale and scope, a hybrid modeling strategy can address this (Figure 4). By combining DPD or MD to simulate the electrostatic behavior near charged surfaces (e.g., glial or ependymal membranes) with LBM or FEM for bulk CSF flow, the full electrohydrodynamic behavior across scales could be captured. These models may communicate via a coupling interface where information on boundary velocities, electric potentials or shear stress is exchanged (Hoogerbrugge and Koelman 1992).

In closing, we have introduced the novel hypothesis that patterns of positive and negative surface charge may exist along the inner linings of the brain’s CSF channels. If present, these structured electrostatic domains could interact with the ionic nature of CSF to generate localized electric fields capable of driving or modulating flow through electro-osmotic mechanisms. Unlike pressure-driven flow, passive electro-osmosis may offer the potential for directionally controlled, rhythmically responsive and spatially fine-tuned fluid movement. These features align with the need for dynamic regulation in neurophysiological contexts, including sleep-wake cycling and metabolic waste clearance. While our approach remains exploratory, it introduces a coherent theoretical model grounded in experimentally supported biophysics. From this model, we expect to observe conditions under which electrostatic patterning produces detectable effects on CSF flow structure, directionality and transport efficiency.

Figure 4.

Conceptual workflow of a hybrid computational model combining near-wall and bulk flow simulations to investigate electrohydrodynamic CSF dynamics. The upper section represents the near-wall simulation zone, where Dissipative Particle Dynamics (DPD) or Molecular Dynamics (MD) are used to capture fine-scale electrostatic interactions, ion layering and local electro-osmotic effects near charged glial or ependymal surfaces. The lower section depicts the bulk flow simulation domain, modeled using Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) or Finite Element Method (FEM), which handles pressure-driven flow and global CSF transport in anatomically relevant structures. The central coupling interface enables dynamic data exchange between the two regions. Velocity and ionic flux data from the particle-based simulation may inform boundary conditions, macroscopic pressure and shear feedbacks.

Figure 4.

Conceptual workflow of a hybrid computational model combining near-wall and bulk flow simulations to investigate electrohydrodynamic CSF dynamics. The upper section represents the near-wall simulation zone, where Dissipative Particle Dynamics (DPD) or Molecular Dynamics (MD) are used to capture fine-scale electrostatic interactions, ion layering and local electro-osmotic effects near charged glial or ependymal surfaces. The lower section depicts the bulk flow simulation domain, modeled using Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) or Finite Element Method (FEM), which handles pressure-driven flow and global CSF transport in anatomically relevant structures. The central coupling interface enables dynamic data exchange between the two regions. Velocity and ionic flux data from the particle-based simulation may inform boundary conditions, macroscopic pressure and shear feedbacks.

Author Contributions

The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Alcaide, Daniel, Jean Cacheux, Aurélien Bancaud, Rieko Muramatsu, and Yukiko T. Matsunaga. "Solute Transport in the Brain Tissue: What Are the Key Biophysical Parameters Tying In Vivo and In Vitro Studies Together?" Biomaterials Science 11, no. 11 (2023): 3450–3460. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, Amer, Wei-Lun Hsu, Moran Wang, and Hirofumi Daiguji. "Electroosmotic Flow: From Microfluidics to Nanofluidics." Electrophoresis 42, no. 3–4 (2021): 513–548. [CrossRef]

- Ballerini, Lucia, Sarah McGrory, Maria del C. Valdés Hernández, Ruggiero Lovreglio, Enrico Pellegrini, Tom MacGillivray, Susana Muñoz Maniega, et al. "Quantitative Measurements of Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in the Brain Are Associated with Retinal Microvascular Parameters in Older Community-Dwelling Subjects." Cerebral Circulation - Cognition and Behavior 1 (2020): 100002. [CrossRef]

- Balood, Mohammad, et al. “Nociceptor Neurons Affect Cancer Immunosurveillance.” Nature 611, no. 7935 (2022): 405–412. [CrossRef]

- Baluška, František and Stefano Mancuso. “Actin Cytoskeleton and Action Potentials: Forgotten Connections.” In The Cytoskeleton, edited by Volker Sahi and František Baluška, 24:109–121. Plant Cell Monographs. Cham: Springer, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D., S. Pati, and P. Biswas. "Analytical Study of Pulsatile Mixed Electroosmotic and Shear-Driven Flow in a Microchannel with a Slip-Dependent Zeta Potential." Applied Mathematics and Mechanics (English Edition) 44 (2023): 1007–1022. [CrossRef]

- Barron, Tara, et al. “GABAergic Neuron-to-Glioma Synapses in Diffuse Midline Gliomas.” Nature 639 (2025): 1060–1068. [CrossRef]

- Bédard, Claude, and Alain Destexhe. "Local Field Potentials: Interaction with the Extracellular Medium." In Encyclopedia of Computational Neuroscience, edited by Dieter Jaeger and Ranu Jung. New York, NY: Springer, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bernal, Jose, Maria D.C. Valdés-Hernández, Javier Escudero, Roberto Duarte, Lucia Ballerini, Mark E. Bastin, Ian J. Deary, Michael J. Thrippleton, Rhian M. Touyz, and Joanna M. Wardlaw. "Assessment of Perivascular Space Filtering Methods Using a Three-Dimensional Computational Model." Magnetic Resonance Imaging 93 (November 2022): 33–51. [CrossRef]

- Brown, Timothy D., Alan Zhang, Frederick U. Nitta, Elliot D. Grant, Jenny L. Chong, Jacklyn Zhu, Sritharini Radhakrishnan, et al. “Axon-like Active Signal Transmission.” Nature 633 (2024): 804–810. [CrossRef]

- Burtscher, Verena, Matej Hotka, Michael Freissmuth and Walter Sandtner. “An Electrophysiological Approach to Measure Changes in the Membrane Surface Potential in Real Time.” Biophysical Journal 118, no. 4 (February 25, 2020): 813–825. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M. I., Y. Li, P. Mistriotis, et al. "Kidney Epithelial Cells Are Active Mechano-Biological Fluid Pumps." Nature Communications 13, no. 1 (2022): 2317. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Dominic, Heather Whitney, Gregory Sutton and Daniel Robert. “Detection and Learning of Floral Electric Fields by Bumblebees.” Science 340, no. 6128 (February 21, 2013): 66–69. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Dominic, Erica Morley and Daniel Robert. “The Bee, the Flower and the Electric Field: Electric Ecology and Aerial Electroreception.” Journal of Comparative Physiology A 203 (2017): 737–748. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Garza, Jesus G., Lokeshwar S. Bhenderu, Khaled M. Taghlabi, Kendall P. Frazee, Jaime R. Guerrero, Matthew K. Hogan, Frances Humes, Robert C. Rostomily, Philip J. Horner, and Amir H. Faraji. "Electrokinetic Convection-Enhanced Delivery for Infusion into the Brain from a Hydrogel Reservoir." Communications Biology 7 (2024): Article 869. [CrossRef]

- Curk, Tine, Sergi G. Leyva and Ignacio Pagonabarraga. “Discontinuous Transition in Electrolyte Flow through Charge-Patterned Nanochannels.” Physical Review Letters 133, no. 7 (August 14, 2024): 078201. [CrossRef]

- Deeg, Cornelia A., Barbara Amann, Konstantin Lutz, Sieglinde Hirmer, Karina Lutterberg, Elisabeth Kremmer and Stefanie M. Hauck. “Aquaporin 11, a Regulator of Water Efflux at Retinal Müller Glial Cell Surface, Decreases Concomitant with Immune-Mediated Gliosis.” Journal of Neuroinflammation 13, no. 89 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Deng, Shiyu, Lin Gan, Chang Liu, Tongtong Xu, Shiyi Zhou, Yiyan Guo, Zhijun Zhang, Guo-Yuan Yang, Hengli Tian, and Yaohui Tang. “Roles of Ependymal Cells in the Physiology and Pathology of the Central Nervous System.” Aging and Disease 14, no. 2 (April 1, 2023): 468–483. [CrossRef]

- Dietz andrea Grostøl, Pia Weikop, Natalie Hauglund, et al. “Local Extracellular K⁺ in Cortex Regulates Norepinephrine Levels, Network State and Behavioral Output.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120, no. 40 (September 29, 2023): e2305071120. [CrossRef]

- Elboughdiri, Noureddine, Khurram Javid, Muhammad Qasim Shehzad, and Yacine Benguerba. "Influence of Chemical Reaction on Electro-Osmotic Flow of Nanofluid Through Convergent Multi-Sinusoidal Passages." Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 54 (February 2024): 103955. [CrossRef]

- England, Sam J. and Daniel Robert. “Electrostatic Pollination by Butterflies and Moths.” Journal of the Royal Society Interface 21, no. 216 (July 24, 2024a): 20240156. [CrossRef]

- England, Sam J. and Daniel Robert. “Prey Can Detect Predators via Electroreception in Air.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 121, no. 23 (May 20, 2024b): e2322674121. [CrossRef]

- Faraji, Amir H., Jonathan J. Cui, Yifat Guy, Ling Li, Colleen A. Gavigan, Timothy G. Strein, and Stephen G. Weber. "Synthesis and Characterization of a Hydrogel with Controllable Electroosmosis: A Potential Brain Tissue Surrogate for Electrokinetic Transport." Langmuir 27, no. 22 (2011).

- Faraji, Amir H. andrea S. Jaquins-Gerstl, Alec C. Valenta, Yanguang Ou and Stephen G. Weber. “Electrokinetic Convection-Enhanced Delivery of Solutes to the Brain.” ACS Chemical Neuroscience 11, no. 14 (July 6, 2020): 2085–2093. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Yuki, Shigetoshi Maekawa and Mitsunori Morita. “Astrocyte Calcium Waves Propagate Proximally by Gap Junction and Distally by Extracellular Diffusion of ATP Released from Volume-Regulated Anion Channels.” Scientific Reports 7 (2017): 13115. [CrossRef]

- Gubbiotti, Alberto, Matteo Baldelli, Giovanni Di Muccio, Paolo Malgaretti, Sophie Marbach, and Mauro Chinappi. "Electroosmosis in Nanopores: Computational Methods and Technological Applications." Advances in Physics: X 7, no. 1 (2022): 2036638. [CrossRef]

- Hauglund, Natalie L., Mie Andersen, Klaudia Tokarska, Tessa Radovanovic, Celia Kjaerby, Frederikke L. Sørensen, Zuzanna Bojarowska, Verena Untiet, Sheyla B. Ballestero, Mie G. Kolmos, Pia Weikop, Hajime Hirase and Maiken Nedergaard. “Norepinephrine-Mediated Slow Vasomotion Drives Glymphatic Clearance during Sleep.” Cell 188, no. 3 (February 6, 2025): 606–622.e17. [CrossRef]

- Hladky, Stephen B. and Margery A. Barrand. “Fluid and Ion Transfer across the Blood–Brain and Blood–Cerebrospinal Fluid Barriers: A Comparative Account of Mechanisms and Roles.” Fluids and Barriers of the CNS 13 (October 31, 2016): 19. [CrossRef]

- Hoogerbrugge, P. J. and J. M. V. A. Koelman. “Simulating Microscopic Hydrodynamic Phenomena with Dissipative Particle Dynamics.” Europhysics Letters 19, no. 3 (1992): 155–160. [CrossRef]

- Hunting, Ellard R., Liam J. O’Reilly, R. Giles Harrison, Sam J. England, Beth H. Harris and Daniel Robert. “Observed Electric Charge of Insect Swarms and Their Contribution to Atmospheric Electricity.” iScience 25, no. 11 (November 18, 2022): 105241. [CrossRef]

- Iliff, Jeffrey J., Minghuan Wang, Yonghong Liao, Benjamin A. Plogg, Weiguo Peng, Georg A. Gundersen, Helene Benveniste, G. Edward Vates, Rashid Deane and Maiken Nedergaard. “A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β.” Science Translational Medicine 4, no. 147 (2012): 147ra111. [CrossRef]

- Jessen, Nanna A. anders S. Munk, Ida Lundgaard and Maiken Nedergaard. “The Glymphatic System: A Beginner’s Guide.” Neurochemical Research 40, no. 12 (December 2015): 2583–2599. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Weiye, Zhi Tang, Yibing Chen, Chuansen Wang, Changwu Tan, Junbo Liao, Lei Tong, and Gelei Xiao. “Ependymal Cilia: Physiology and Role in Hydrocephalus.” Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 15 (July 12, 2022). [CrossRef]

- Jonusaite, Sima and Nina Himmerkus. “Paracellular Barriers: Advances in Assessing Their Contribution to Renal Epithelial Function.” Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 298 (December 2024): 111741. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, Kaito, Leticia Galera-Laporta, Colleen Weatherwax, Jamie Y. Lam, Eun Chae Moon, Emmanuel A. Theodorakis, Jordi Garcia-Ojalvo and Gürol M. Süel. “Electrochemical Potential Enables Dormant Spores to Integrate Environmental Signals.” Science 378, no. 6615 (October 6, 2022): 43–49. [CrossRef]

- Kwee, Robert M., and Thomas C. Kwee. "Virchow-Robin Spaces at MR Imaging." RadioGraphics 27, no. 4 (July 1, 2007): 1071–1086. [CrossRef]

- Li, Minglun, and Murugappan Muthukumar. "Electro-Osmotic Flow in Nanoconfinement: Solid-State and Protein Nanopores." Journal of Chemical Physics 160, no. 8 (February 28, 2024): 084905. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Jiachen, Yunzhi Guo, Chengyue Zhang, Yang Zeng, Yongqi Luo and Gaiqing Wang. “Clearance Systems in the Brain, From Structure to Function.” Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 15 (, 2022): 729706. [CrossRef]

- Marques-Almeida, Teresa, Clarisse Ribeiro, Igor Irastorza, Patrícia Miranda-Azpiazu, Ignacio Torres-Alemán, Unai Silvan and Senentxu Lanceros-Méndez. “Electroactive Materials Surface Charge Impacts Neuron Viability and Maturation in 2D Cultures.” ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 15, no. 26 (June 22, 2023): 31206–31213. [CrossRef]

- McColgan, Thomas, Ji Liu, Paula Tuulia Kuokkanen, Catherine Emily Carr, Hermann Wagner, and Richard Kempter. "Dipolar Extracellular Potentials Generated by Axonal Projections." eLife, September 5, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Mestre, Helena, Yuichiro Mori and Maiken Nedergaard. “The Brain’s Glymphatic System: Current Controversies.” Trends in Neurosciences 43, no. 7 (July 2020): 458–466. [CrossRef]

- Nishino, Masaru, Ibu Matsuzaki, Fidele Y. Musangile, Yuichi Takahashi, Yoshifumi Iwahashi, Kenji Warigaya, Yuichi Kinoshita, Fumiyoshi Kojima and Shin-ichi Murata. “Measurement and Visualization of Cell Membrane Surface Charge in Fixed Cultured Cells Related with Cell Morphology.” PLoS One 15, no. 7 (July 23, 2020): e0236373. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Jianming, Ya Hua, Guohua Xi and Richard F. Keep. “Mechanisms of Cerebrospinal Fluid and Brain Interstitial Fluid Production.” Neurobiology of Disease 183 (July 2023): 106159. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Jimenez, Victor and Robert Dudley. “Spiderweb Deformation Induced by Electrostatically Charged Insects.” Scientific Reports 3 (2013): 2108. [CrossRef]

- Padmanaban, Veena, et al. “Neuronal Substance P Drives Metastasis through an Extracellular RNA–TLR7 Axis.” Nature 633 (2024): 207–215. [CrossRef]

- Raicevic, Nikola, Jarod M. Forer, Antonio Ladrón-de-Guevara, Ting Du, Maiken Nedergaard, Douglas H. Kelley, and Kimberly Boster. "Sizes and Shapes of Perivascular Spaces Surrounding Murine Pial Arteries." Fluids and Barriers of the CNS 20, no. 56 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Mikkel K., Helena Mestre and Maiken Nedergaard. “The Glymphatic Pathway in Neurological Disorders.” The Lancet Neurology 17, no. 11 (November 2018): 1016–1024. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Rune, John O’Donnell, Fengfei Ding and Maiken Nedergaard. “Interstitial Ions: A Key Regulator of State-Dependent Neural Activity?” Progress in Neurobiology 193 (October 2020): 101802. [CrossRef]

- Ray, Lori A. and Jeffrey J. Heys. “Fluid Flow and Mass Transport in Brain Tissue.” Fluids 4, no. 4 (2019): 196. [CrossRef]

- Robin, P., T. Emmerich, A. Ismail, A. Niguès, Y. You, G.-H. Nam, A. Keerthi, A. Siria, A. K. Geim and L. Bocquet. “Long-Term Memory and Synapse-Like Dynamics in Two-Dimensional Nanofluidic Channels.” Science 379, no. 6628 (January 12, 2023): 161–167. [CrossRef]

- Sahib, A. A., I. Bushra, and G. Rejimon. "Electro-osmosis: A Review from the Past." In Problematic Soils and Geoenvironmental Concerns, edited by M. Latha Gali and P. Raghuveer Rao, 673–687. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, vol. 88. Singapore: Springer, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sanapathi, Jayita, Pravinkumar Vipparthi, Sushmita Mishra, Alejandro Sosnik and Murali Kumarasamy. “Microfluidics for Brain Endothelial Cell-Astrocyte Interactions.” Organs-on-a-Chip 5 (December 2023): 100033. [CrossRef]

- Santa-Maria, Ana R., Fruzsina R. Walter, Sándor Valkai, Ana Rita Brás, Mária Mészáros andrás Kincses, Adrián Klepe, Diana Gaspar, Miguel A. R. B. Castanho, László Zimányi andrás Dér and Mária A. Deli. “Lidocaine Turns the Surface Charge of Biological Membranes More Positive and Changes the Permeability of Blood-Brain Barrier Culture Models.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1861, no. 9 (September 1, 2019): 1579–1591. [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, J. D., M. Mao, and S. Ghosal. "Electroosmosis in a Finite Cylindrical Pore: Simple Models of End Effects." Langmuir 30, no. 31 (2014): 9261–9271. [CrossRef]

- Sincomb, S., W. Coenen, A. L. Sánchez, and J. C. Lasheras. "A Model for the Oscillatory Flow in the Cerebral Aqueduct." Journal of Fluid Mechanics, published online July 20, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tumani, Hayrettin andré Huss and Franziska Bachhuber. “The Cerebrospinal Fluid and Barriers – Anatomic and Physiologic Considerations.” In Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 146, edited by M. J. Aminoff, F. Boller and D. F. Swaab, 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Untiet, Verena. “Astrocytic Chloride Regulates Brain Function in Health and Disease.” Cell Calcium 118 (March 2024): 102855. [CrossRef]

- Verveniotis, E., A. Kromka, M. Ledinský, P. Hubík, D. Potocký, L. Frank, and J. Rezek. "Guided Assembly of Nanoparticles on Electrostatically Charged Nanocrystalline Diamond Thin Films." Nanoscale Research Letters 6, no. 1 (2011): 144. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Ho-Ching (Shawn), Ben Inglis, Thomas M. Talavage, Vidhya Vijayakrishnan Nair, Jinxia (Fiona) Yao, Bradley Fitzgerald, Amy J. Schwichtenberg and Yunjie Tong. “Coupling between Cerebrovascular Oscillations and CSF Flow Fluctuations during Wakefulness: An fMRI Study.” Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 42, no. 6 (January 16, 2022): 1091–1103. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Kensuke, Shoi Shi, Maki Ukai-Tadenuma, Hiroshi Fujishima, Rei-ichiro Ohno and Hiroki R. Ueda. “Leak Potassium Channels Regulate Sleep Duration.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, no. 40 (September 17, 2018): E9459–E9468. [CrossRef]

- Wakasugi, Rio, Kenji Suzuki, and Takako Kaneko-Kawano. "Molecular Mechanisms Regulating Vascular Endothelial Permeability." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 12 (2024): 6415. [CrossRef]

- Walter, Fruzsina R., Ana R. Santa-Maria, Mária Mészáros, Szilvia Veszelka andrás Dér and Mária A. Deli. “Surface Charge, Glycocalyx and Blood-Brain Barrier Function.” Tissue Barriers 9, no. 3 (May 18, 2021): 1904773. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Teng, Svein Kleiven and Xiaogai Li. “Electroosmosis Based Novel Treatment Approach for Cerebral Edema.” IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 68, no. 9 (September 2021): 2645–2653. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Mingyan, Wei Zhang and Zhi Qi. "Platelet Deposition Onto Vascular Wall Regulated by Electrical Signal." Frontiers in Physiology 12 (December 23, 2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Mingzhao, Xiangjun Hu and Lifeng Wang. “A Review of Cerebrospinal Fluid Circulation and the Pathogenesis of Congenital Hydrocephalus.” Neurochemical Research 49, no. 5 (February 10, 2024): 1123–1136. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Fangfang, Liyuan Zhong, and Yumin Luo. "Endothelial Glycocalyx as an Important Factor in Composition of Blood–Brain Barrier." CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics 26, no. 12 (2020): 1205–1214. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Min, Yixing Du, Sydney Aten and David Terman. “On the Electrical Passivity of Astrocyte Potassium Conductance.” Journal of Neurophysiology 126, no. 4 (September 15, 2021): 1403–1419. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).