Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

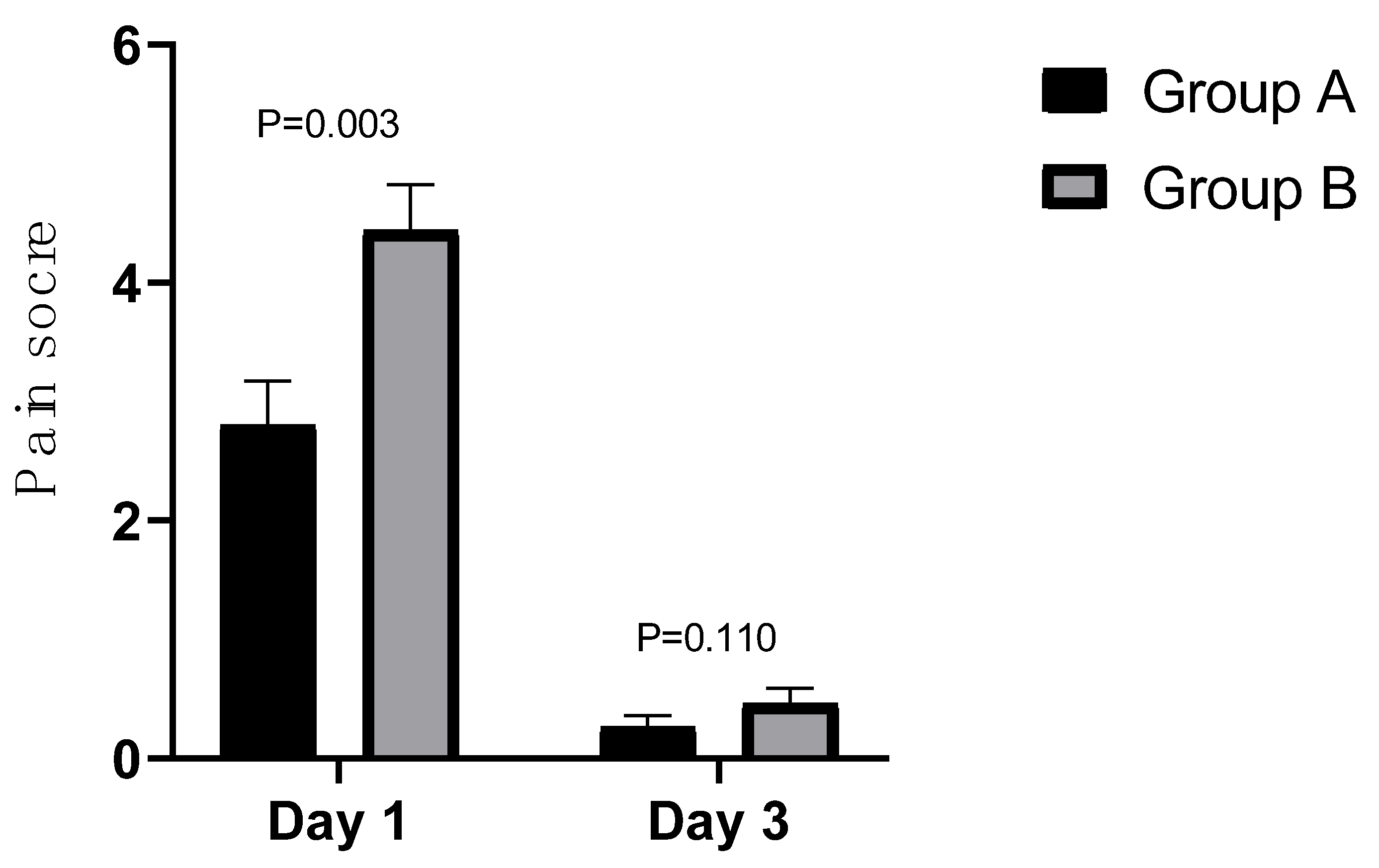

Ocular Pain Intensity

Subjective Ocular Irritation

Corneal Epithelial Healing

Slit-Lamp Evaluation

Visual Acuity

Protein Precipitation Measured on BCL

Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Munnerlyn, C.R.; Koons, S. J.; Marshall, J. Photorefractive keratectomy: a technique for laser refractive surgery. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery.1988,14(1),46–52. [CrossRef]

- Ambrósio, R.Jr.; Wilson,S. LASIK vs LASEK vs PRK: advantages and indications. Seminars in ophthalmology.2003,18(1), 2–10.

- Steinert,R.F.;Bafna, S. Surgical correction of moderate myopia: which method should you choose? II. PRK and LASIK are the treatments of choice. Survey of ophthalmology.1998,43(2), 157–179.

- McCarty, C. A.; Garrett, S. K.; Aldred, G. F.; Taylor, H. R. Assessment of subjective pain following photorefractive keratectomy. Melbourne Excimer Laser Group. Journal of refractive surgery.1996,12(3), 365–369.

- Gimbel, H. V.;DeBroff, B. M.;Beldavs, R. A.; van Westenbrugge, J. A.; Ferensowicz, M. Comparison of laser and manual removal of corneal epithelium for photorefractive keratectomy. Journal of refractive surgery.1995, 11(1), 36–41. [CrossRef]

- Luger, M. H.; Ewering, T.; Arba-Mosquera, S. Consecutive myopia correction with transepithelial versus alcohol-assisted photorefractive keratectomy in contralateral eyes: one-year results. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery.2012,38(8), 1414–1423. [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, A.;Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Stojanovic, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.; Utheim, T. P. One-step transepithelial topography-guided ablation in the treatment of myopic astigmatism. 2013,PloS one, 8(6), e66618. [CrossRef]

- Xi, L.; Zhang, C.; He, Y. Clinical outcomes of Transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy to treat low to moderate myopic astigmatism. BMC ophthalmology.2018,18(1), 115. [CrossRef]

- Fadlallah, A.; Fahed, D.; Khalil, K.; Dunia, I.; Menassa, J.; El Rami, H.; Chlela, E.; Fahed, S. Transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy: clinical results. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery.2011,37(10), 1852–1857. [CrossRef]

- Celik, U.; Bozkurt, E.; Celik, B.; Demirok, A.; Yilmaz, O. F. Pain, wound healing and refractive comparison of mechanical and transepithelial debridement in photorefractive keratectomy for myopia: results of 1 year follow-up. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association.2014, 37(6), 420–426. [CrossRef]

- Naderi,M.;Jadidi,K.;Mosavi,S.A.;Daneshi,S.A. Transepithelial Photorefractive Keratectomy for Low to Moderate Myopia in Comparison with Conventional Photorefractive Keratectomy. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research.2016,11(4), 358–362. [CrossRef]

- Vinciguerra, P.; Camesasca, F. I.; Vinciguerra, R.; Arba-Mosquera, S.; Torres, I.; Morenghi, E.; Randleman, J. B. Advanced Surface Ablation With a New Software for the Reduction of Ablation Irregularities. Journal of refractive surgery .2017, 33(2), 89–95. [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh, A. M.; Elwan, S. A. M.; Chaudhry, A. A.; El-Atris, T. M.; Al-Howish, T. M. Comparison between Transepithelial Photorefractive Keratectomy versus Alcohol-Assisted Photorefractive Keratectomy in Correction of Myopia and Myopic Astigmatism. Journal of ophthalmology.2018, 5376235. [CrossRef]

- Luger, M. H.; Ewering, T.; Arba-Mosquera, S. Myopia correction with transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy versus femtosecond-assisted laser in situ keratomileusis: One-year case-matched analysis. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery.2016,42(11),1579–1587. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.J.; Sinton, J.E.; Frazer, D.G.; Morrison, E. Therapeutic contact lenses and their use in themanagement of anterior segment pathology. Journal of the British Contact Lens Association.1996,19(1),11-19. [CrossRef]

- Bergenske, P.; Caroline, P.; Smithe, J. Contact lenses as an adjunct in refractive surgery practice. Contact Lens Spectrum. 2002, 17, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Demers, P.; Thompson, P.; Bernier, R.G.; Lemire, J.; Laflamme, P. Effect of occlusive pressure patching on the rate of epithelial wound healing after photorefractive keratectomy. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery.1996, 22(1), 59–62. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W. J.; Zeng, J.; Cui, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Z. M.; Liao, W. X.; Yang, X. H. Comparation of effectiveness of silicone hydrogel contact lens and hydrogel contact lens in patients after LASEK. International journal of ophthalmology.2015,8(6), 1131–1135. [CrossRef]

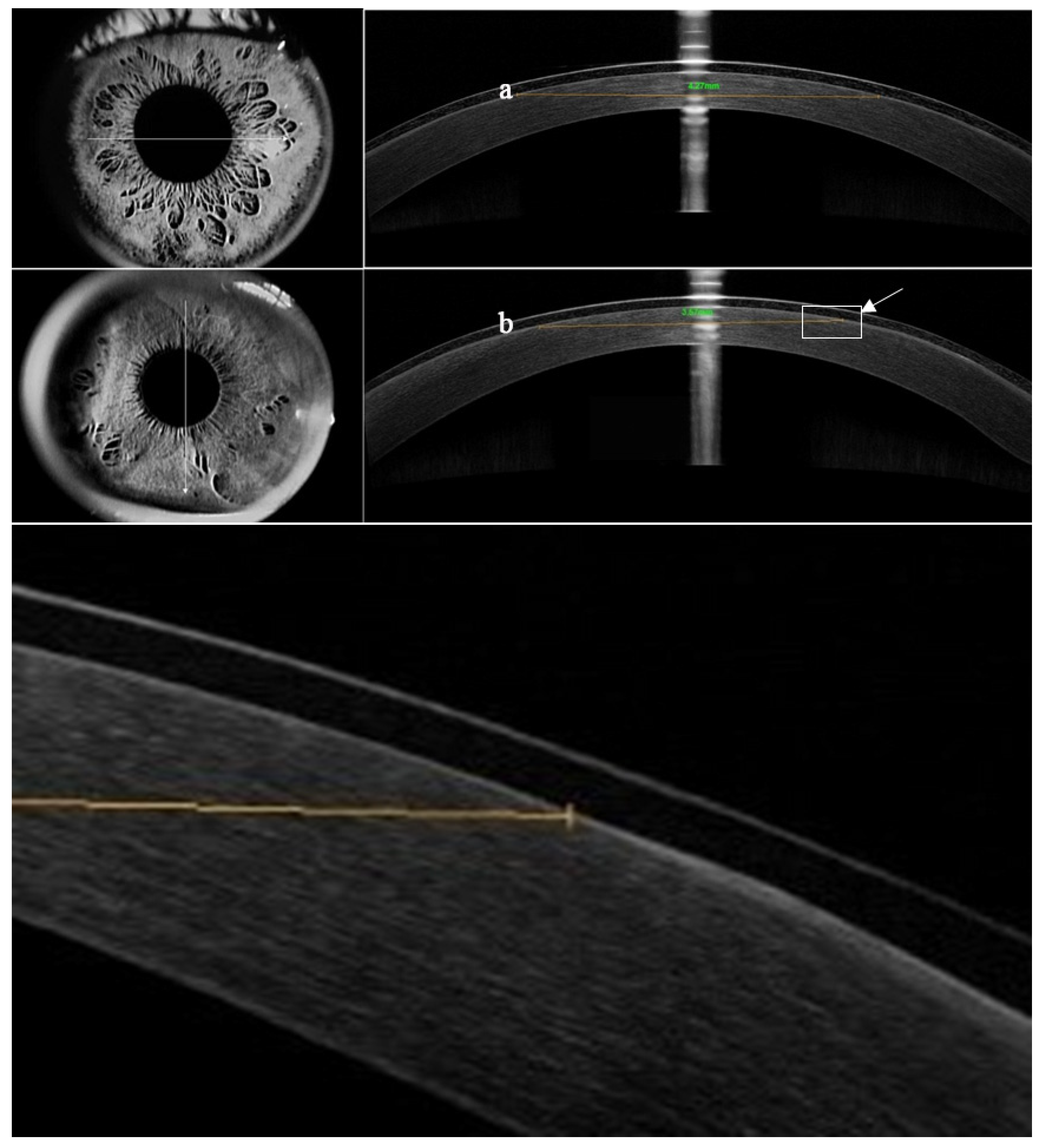

- Eliaçık, M.; Erdur, S. K.; Gülkılık, G.; Özsütçü, M.; Karabela, Y. Compare the effects of two silicone-hydrogel bandage contact lenses on epithelial healing after photorefractive keratectomy with anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association.2015,38(3), 215–219. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. R., Molchan, R. P., Townley, J. R., Caldwell, M. C., Panday, V. A. The effect of silicone hydrogel bandage soft contact lens base curvature on comfort and outcomes after photorefractive keratectomy. Eye & contact lens.2015, 41(2), 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.; Lim, E. W. L. Therapeutic Contact Lenses in the Treatment of Corneal and Ocular Surface Diseases-A Review. Asia-Pacific journal of ophthalmology.2020 , 9(6), 524–532. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xi, S.; Wang, B.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, K.; Zhou, X. Clinical Observation of Silicon Hydrogel Contact Lens Fitted Immediately after Small Incision Lenticule Extraction (SMILE). Journal of ophthalmology.2020, 2604917. [CrossRef]

- Shimazaki, J., Shigeyasu, C., Saijo-Ban, Y., Dogru, M., Den, S. Effectiveness of bandage contact lens application in corneal epithelialization and pain alleviation following corneal transplantation; prospective, randomized clinical trial. BMC ophthalmology.2016, 16(1), 174. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; He, J.; Liu, Y . Effect of rigid corneal contact lens and corneal limbal stem cell transplantation for senile patients with pterygium Int Eye Sci. 2017, 17(6), 1188-1190.

- Sánchez-González, J. M.; López-Izquierdo, I.; Gargallo-Martínez, B.; De-Hita-Cantalejo, C.; Bautista-Llamas, M. J. Bandage contact lens use after photorefractive keratectomy. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2019, 45(8), 1183–1190. [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, E.; Ozulken, K.; Uzel, M. M.; Taslipinar Uzel, A. G.; Aydoğan, S. Comparison of Samfilcon A and Lotrafilcon B silicone hydrogel bandage contact lenses in reducing postoperative pain and accelerating re-epithelialization after photorefractive keratectomy. International ophthalmology.2019, 39(11), 2569–2574. [CrossRef]

- Szaflik, J. P.; Ambroziak, A. M.; Szaflik, J. Therapeutic use of a lotrafilcon A silicone hydrogel soft contact lens as a bandage after LASEK surgery. Eye & contact lens.2004, 30(1), 59–62.

- Taylor, K. R.; Caldwell, M. C.; Payne, A. M.; Apsey, D. A.; Townley, J. R.; Reilly, C. D.; Panday, V. A. Comparison of 3 silicone hydrogel bandage soft contact lenses for pain control after photorefractive keratectomy. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery.2014,40(11), 1798–1804. [CrossRef]

- Guillon, M. Are silicone hydrogel contact lenses more comfortable than hydrogel contact lenses?. Eye & contact lens.2013, 39(1), 86–92. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Ioannides, A.; Aslanides, I. Comparative evaluation of Comfilcon A and Senofilcon A bandage contact lenses after transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy. Journal of optometry.2015, 8(1), 27–32. [CrossRef]

- Arora, R.; Jain, S.; Monga, S.; Narayanan, R.; Raina, U. K.; Mehta, D. K. Efficacy of continuous wear PureVision contact lenses for therapeutic use. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association. 2004, 27(1), 39–43.

- Ozkurt, Y.; Rodop, O.; Oral, Y.; Cömez, A.; Kandemir, B.; & Doğan, O. K. Therapeutic applications of lotrafilcon a silicone hydrogel soft contact lenses. Eye & contact lens.2005, 31(6), 268–269. [CrossRef]

- Hartrick, C. T.; Kovan, J. P.; Shapiro, S. The numeric rating scale for clinical pain measurement: a ratio measure?. Pain practice : the official journal of World Institute of Pain. 2003, 3(4), 310–316. [CrossRef]

- Engle, A. T.; Laurent, J. M.; Schallhorn, S. C.; Toman, S. D.; Newacheck, J. S.; Tanzer, D. J.; Tidwell, J. L. Masked comparison of silicone hydrogel lotrafilcon A and etafilcon A extended-wear bandage contact lenses after photorefractive keratectomy. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2005, 31(4), 681–686. [CrossRef]

- Efron, N.; Morgan, P. B.; Katsara, S. S. Validation of grading scales for contact lens complications. Ophthalmic & physiological optics : the journal of the British College of Ophthalmic Opticians (Optometrists). 2001, 21(1), 17–29.

- Gil-Cazorla, R.; Teus, M. A.; Arranz-Márquez, E. Comparison of silicone and non-silicone hydrogel soft contact lenses used as a bandage after LASEK. Journal of refractive surgery. 2008, 24(2), 199–203. [CrossRef]

- Razmjoo, H.; Abdi, E.; Atashkadi, S.; Reza, A. M.; Reza, P. A.; Akbari, M. Comparative Study of Two Silicone Hydrogel Contact Lenses used as Bandage Contact Lenses after Photorefractive Keratectomy. International journal of preventive medicine. 2012, 3(10), 718–722.

- Qu, X. M.; Dai, J. H.; Jiang, Z. Y.; Qian, Y. F. Clinic study on silicone hydrogel contact lenses used as bandage contact lenses after LASEK surgery. International journal of ophthalmology. 2011, 4(3), 314–318. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shao, T.; Zhang, J. F.; Leng, L.; Liu, S.; Long, K. L. Comparison of efficacy of two different silicone hydrogel bandage contact lenses after T-PRK. International journal of ophthalmology. 2022, 15(2), 299–305. [CrossRef]

- Lotfy, N. M.; Alasbali, T.; Alsharif, A. M.; Al-Gehedan, S. M.; Jastaneiah, S.; Al-Hazaimeh, A.; Ali, H.; Khandekar, R. Comparison of the efficacy of lotrafilcon B and comfilcon A silicone hydrogel bandage contact lenses after transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy. Medical hypothesis, discovery & innovation ophthalmology journal. 2021, 10(2), 43–49. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. D.; Bower, K. S.; Sediq, D. A.; Burka, J. M.; Stutzman, R. D.; Vanroekel, C. R.; Kuzmowych, C. P.; Eaddy, J. B. Effects of lotrafilcon A and omafilcon A bandage contact lenses on visual outcomes after photorefractive keratectomy. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2008, 34(8), 1288–1294. [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, S. J. The use of contact lenses in the treatment of persistent epithelial defects. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association. 2010, 33(5), 239–244.

- Grentzelos, M. A.; Plainis, S.; Astyrakakis, N. I.; Diakonis, V. F.; Kymionis, G. D.; Kallinikos, P.; Pallikaris, I. G. Efficacy of 2 types of silicone hydrogel bandage contact lenses after photorefractive keratectomy. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2009, 35(12), 2103–2108. [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.; Tan, D. T.; Chan, W. K. Therapeutic use of Bausch & Lomb PureVision contact lenses. The CLAO journal : official publication of the Contact Lens Association of Ophthalmologists. 2001, Inc, 27(4), 179–185.

- Fonn, D.; Dumbleton, K.; Jones, L. Silicone hydrogel material and surface properties. Contact Lens Spectrum. 2002, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.; Senchyna, M.; Glasier, M. A.; Schickler, J.; Forbes, I.; Louie, D.; May, C. Lysozyme and lipid deposition on silicone hydrogel contact lens materials. Eye & contact lens. 2003, 29(1 Suppl), S75–S194. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Cazorla, R.; Teus, M. A.; Hernández-Verdejo, J. L.; De Benito-Llopis, L.; García-González, M. Comparative study of two silicone hydrogel contact lenses used as bandage contact lenses after LASEK. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 2008, 85(9), 884–888. [CrossRef]

- Sack, R. A.; Jones, B.; Antignani, A.; Libow, R.; Harvey, H. Specificity and biological activity of the protein deposited on the hydrogel surface. Relationship of polymer structure to biofilm formation. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1987, 28(5), 842–849.

- Myers, R. I.; Larsen, D. W.; Tsao, M.; Castellano, C.; Becherer, L. D.; Fontana, F.; Ghormley, N. R.; Meier, G. Quantity of protein deposited on hydrogel contact lenses and its relation to visible protein deposits. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 1991, 68(10), 776–782. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, M.; Heidari, Z.; Hashemi, H.; Asgari, S. Comparison of the Lotrafilcon B and Comfilcon A Silicone Hydrogel Bandage Contact Lens on Postoperative Ocular Discomfort After Photorefractive Keratectomy. Eye & contact lens. 2018, 44 Suppl 2, S273–S276. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | BCL A (Air Optix Night & Day) | BCL B (PureVision) |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Lotrafilcon A | Balafilcon A |

| Water content | 24% | 36% |

| Dk | 140 | 91 |

| Dk/t | 175 | 101 |

| Surface treatment | Plasma Coating | Plasma Oxidation |

| Elastic modulus | 1.4 MPa | 1.1 MPa |

| Central thickness | 0.08 mm | 0.09 mm |

| BOZR | 8.6 mm | 8.6 mm |

| TD | 13.8 mm | 14 mm |

| Continuous overnight wear | 28 days | 21 days |

| Dk: Oxygen permeability (×); Dk/t: Oxygen transmissibility (×;, BOZR: Back optic zone radius; TD: Total diameter; BCL: Bandage contact lens | ||

| Grade | Lens movement |

|---|---|

| 0 | Extremely inadequate; lens does not move on blinking |

| 1 | Slightly inadequate; lens moves < 0.2 mm on blinking |

| 2 | Optimum; lens moves between 0.2 and 0.4 mm on blinking |

| 3 | Slightly excessive; lens moves between 0.4 and 1.0 mm on blinking |

| 4 | Extremely excessive; lens moves > 1.0 mm on blinking |

| Grade | Lens deposits |

|---|---|

| 0 | None |

| 1 | Five or fewer small (<0.1 mm) deposits or very slight film covering up to 25% of the lens surface |

| 2 | More than five small individual deposits, one individual deposit 0.1 to 0.5 mm in diameter, or film covering between 25%-50% of the lens surface area |

| 3 | Multiple deposits between 0.1 and 0.5 mm in diameter, one deposit larger than 0.5 mm in diameter, or moderate film covering between 50%-75% of the lens surface area |

| 4 | Multiple deposits of 0.5 mm in diameter or larger or film covering more than 75% of the lens surface area |

| Group A | Group B | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n) | Male/female=18/23 | ||

| Age (y) | 25.46 ± 4.36 (range: 17–35) | ||

| SER (D) | −5.53 ± 1.94 | −5.51 ± 2.00 | 0.747 |

| Mean UDVA (logMAR) | 1.08 ± 0.30 | 1.10 ± 0.34 | 0.315 |

| Mean CDVA (logMAR) | -0.00 ± 0.01 | -0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.157 |

| Diameter of the operative Optical zone (mm) | 6.39 ± 0.52 | 6.38 ± 0.53 | 0.486 |

| Diameter of the surgical Treatment zone (mm) | 7.95 ± 0.37 | 7.94 ± 0.35 | 0.729 |

| Surgical ablation depth (μm) | 138.66 ± 18.10 | 138.27 ± 19.60 | 0.698 |

| SER: Spherical equivalent refraction; UDVA: Uncorrected Distance Visual Acuity; CDVA: Corrected Distance Visual Acuity. | |||

| Day 1 | Day 3 | |||||

| Grade | Group A | Group B | p | Group A | Group B | p |

| Foreign body sensation | 0.001 | 0.000 | ||||

| 0 | 12(29.3%) | 4(9.8%) | 16(39.0%) | 6(14.6%) | ||

| 1 | 9(22.0%) | 3(7.3%) | 19(46.3%) | 18(43.9%) | ||

| 2 | 8(19.5%) | 6(14.6%) | 2(4.9%) | 6(14.6%) | ||

| 3 | 6(14.6%) | 8(19.5%) | 4(9.8%) | 9(22.0%) | ||

| 4 | 6(14.6%) | 20(48.8%) | 0(0%) | 2(4.9%) | ||

| Pain | 0.001 | 0.705 | ||||

| 0 | 4(9.8%) | 0(0%) | 24(58.8%) | 23(56.1%) | ||

| 1 | 12(29.3%) | 9(22.0%) | 14(34.1%) | 14(34.1%) | ||

| 2 | 6(14.6%) | 4(9.8%) | 1(2.4%) | 3(7.3%) | ||

| 3 | 9(22.0%) | 9(22.0%) | 2(4.9%) | 1(2.4%) | ||

| 4 | 10(24.4%) | 19(46.3%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | ||

| Photophobia | 0.190 | 1.000 | ||||

| 0 | 4(9.8%) | 4(9.8%) | 4(9.8%) | 4(9.8%) | ||

| 1 | 3(7.3%) | 1(2.4%) | 22(53.7%) | 23(56.1%) | ||

| 2 | 7(17.1%) | 7(17.1%) | 9(22.0%) | 7(17.1%) | ||

| 3 | 12(29.3%) | 13(21.7%) | 5(12.2%) | 6(14.6%) | ||

| 4 | 15(36.6%) | 16(39.0%) | 1(2.4%) | 1(2.4%) | ||

| Dry eye | 0.066 | 0.157 | ||||

| 0 | 21(51.2%) | 20(48.8%) | 16(39.0%) | 15(36.6%) | ||

| 1 | 12(29.3%) | 10(24.4%) | 18(43.9%) | 18(43.9%) | ||

| 2 | 4(9.8%) | 5(12.2%) | 1(2.4%) | 2(4.9%) | ||

| 3 | 2(4.9%) | 3(7.3%) | 5(12.2%) | 5(12.2%) | ||

| 4 | 2(4.9%) | 3(7.3%) | 1(2.4%) | 1(2.4%) | ||

| Day 1 | Day 3 | |||||

| Grade | Group A | Group B | P | Group A | Group B | P |

| Limbal hyperemia | 0.157 | 0.257 | ||||

| 0 | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 2(4.9%) | 1(2.4%) | ||

| 1 | 11(26.8%) | 8(19.5%) | 31(75.6%) | 30(73.2%) | ||

| 2 | 24(58.5%) | 26(63.4%) | 8(19.5%) | 10(24.4%) | ||

| 3 | 6(14.6%) | 7(17.1%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | ||

| 4 | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | ||

| Conjunctival hyperemia | 0.414 | 0.705 | ||||

| 0 | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 4(9.8%) | 4(9.8%) | ||

| 1 | 9(22.0%) | 7(17.1%) | 29(70.7%) | 28(68.3%) | ||

| 2 | 25(61.0%) | 27(65.9%) | 8(19.5%) | 9(22.0%) | ||

| 3 | 7(17.1%) | 7(17.1%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | ||

| 4 | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | ||

| Lens movement | 0.527 | 0.132 | ||||

| 0 | 30(73.2%) | 31(75.6%) | 11(26.8%) | 16(39.0%) | ||

| 1 | 7(17.1%) | 6(14.6%) | 21(51.2%) | 16(39.0%) | ||

| 2 | 3(7.3%) | 4(9.8%) | 9(22.0%) | 9(22.0%) | ||

| 3 | 1(2.4%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | ||

| 4 | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | ||

| Lens deposits | 0.796 | 0.071 | ||||

| 0 | 8(19.5%) | 4(9.8%) | 8(19.5%) | 3(7.3%) | ||

| 1 | 15(36.6%) | 21(51.2%) | 25(61.0%) | 28(68.3%) | ||

| 2 | 17(41.5%) | 16(39%) | 8(19.5%) | 10(24.4%) | ||

| 3 | 1(2.4%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | ||

| 4 | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).