Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient and Skin Samples

2.2. Treatments

2.3. Histological Analysis

2.4. Molecular Biology Analysis

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

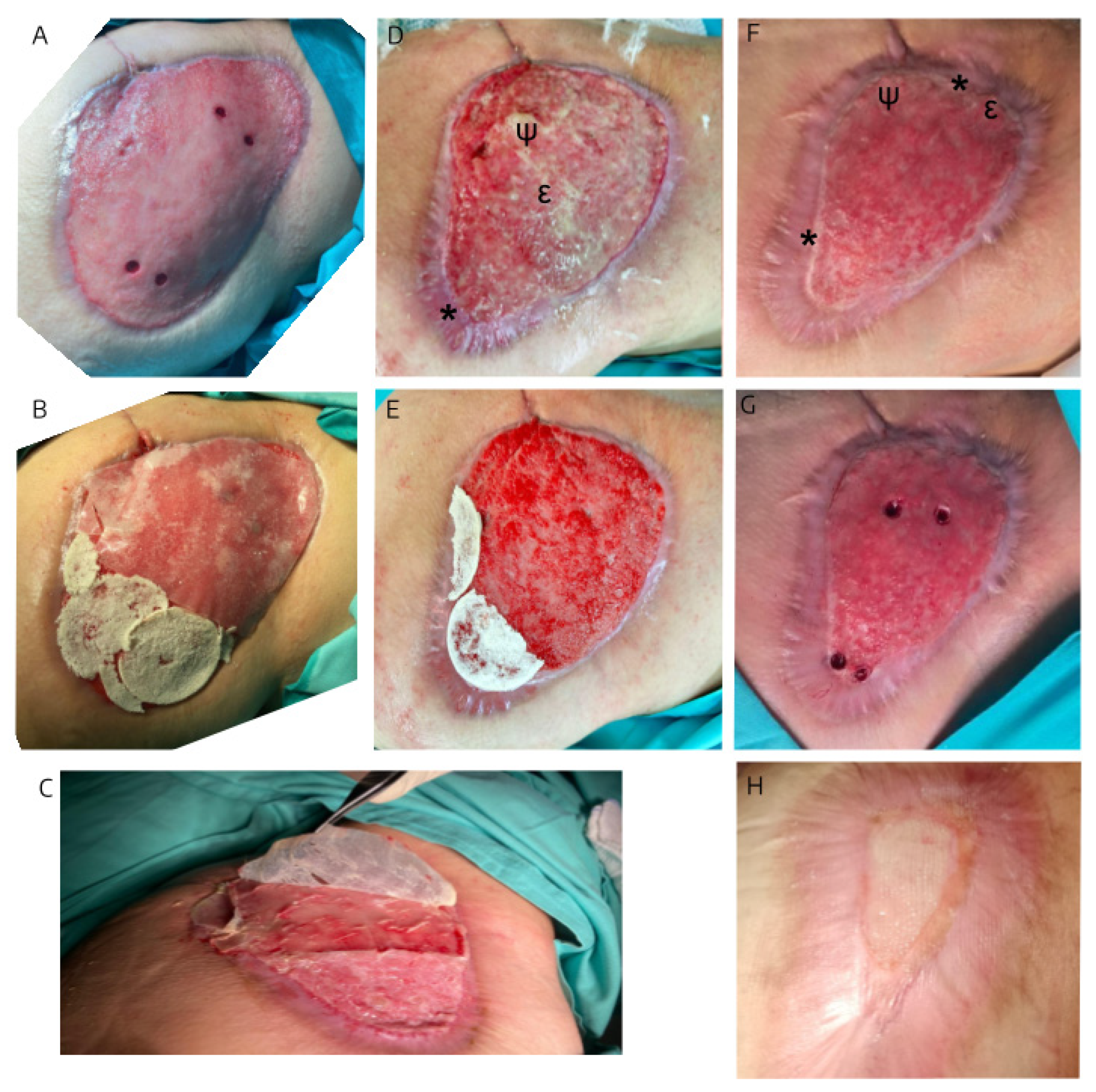

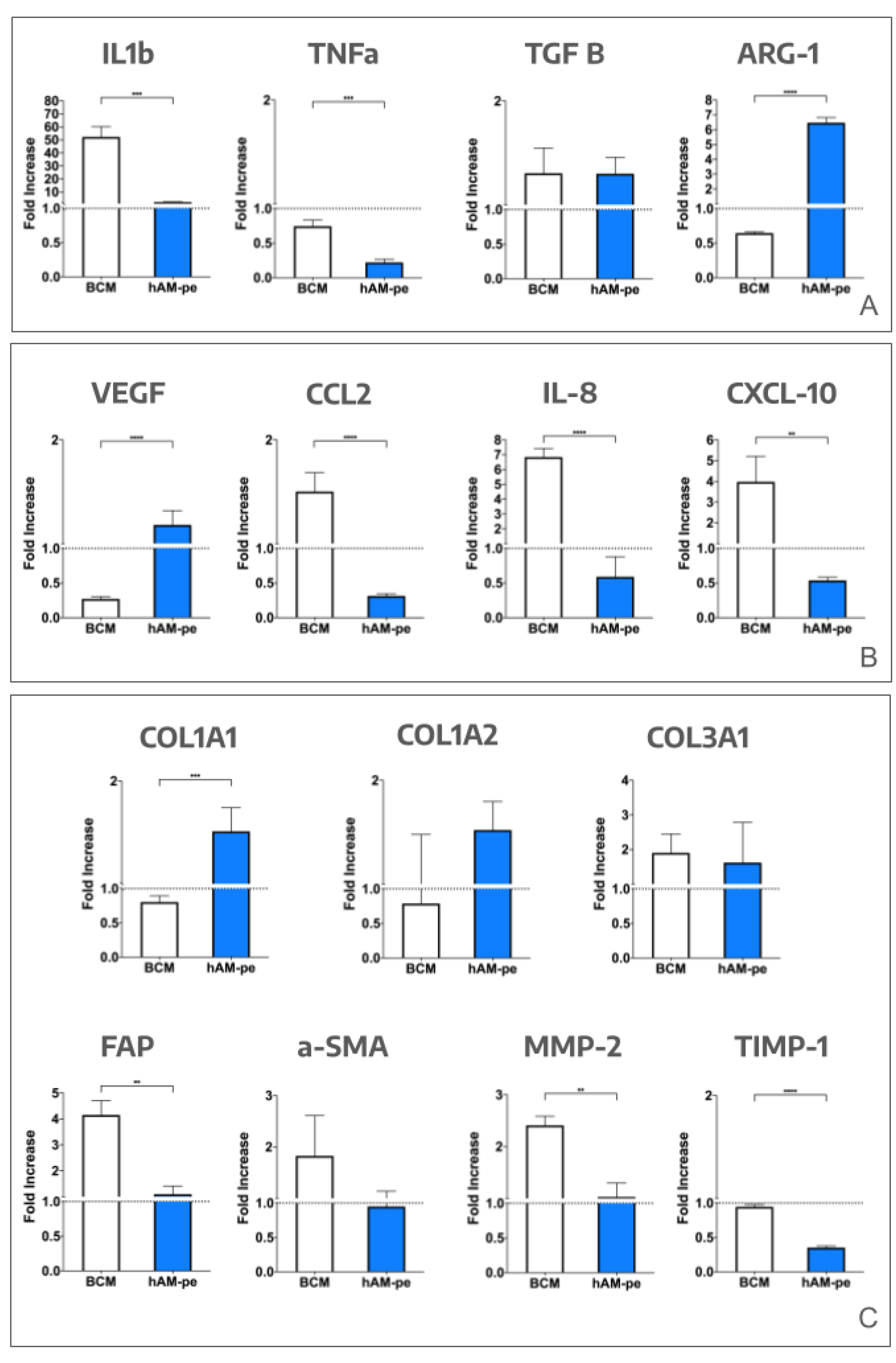

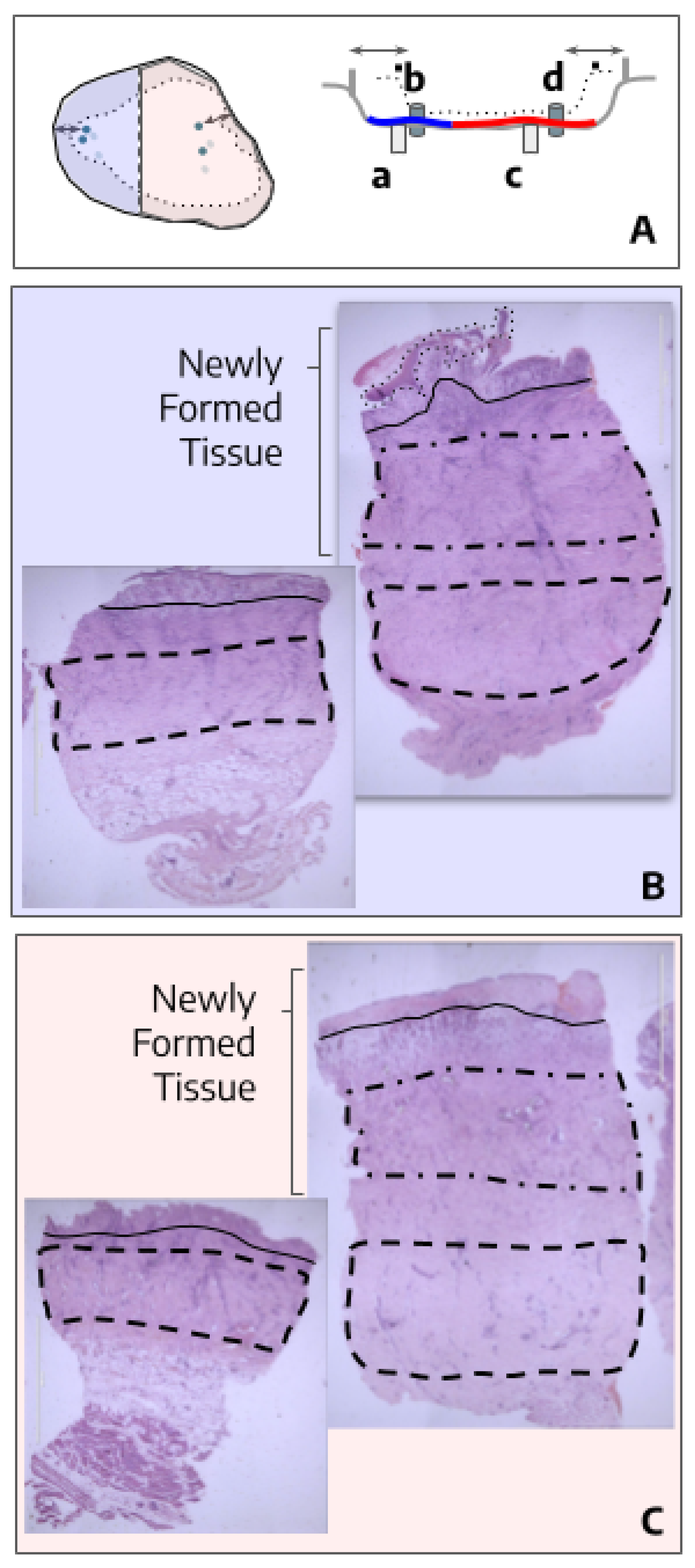

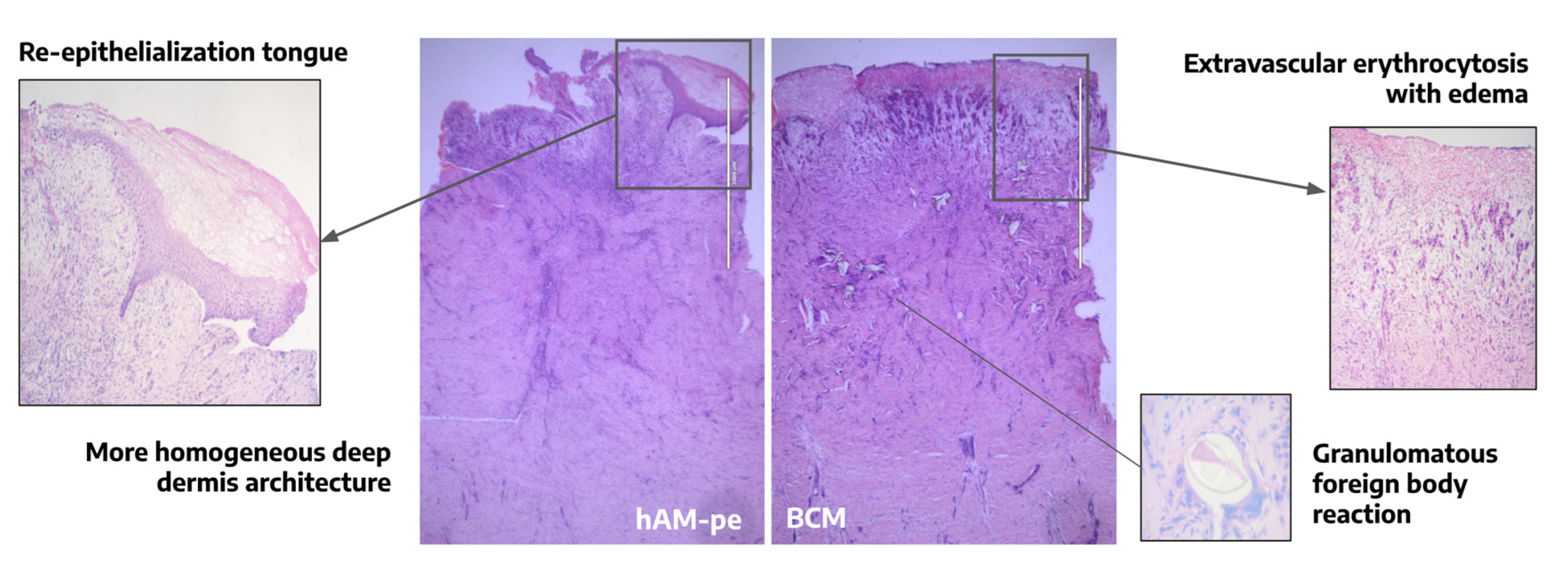

3.1. The evolution of the wound treated with hAM-pe is associated with a faster progression of the re-epithelialization front and a reduced local inflammatory activity

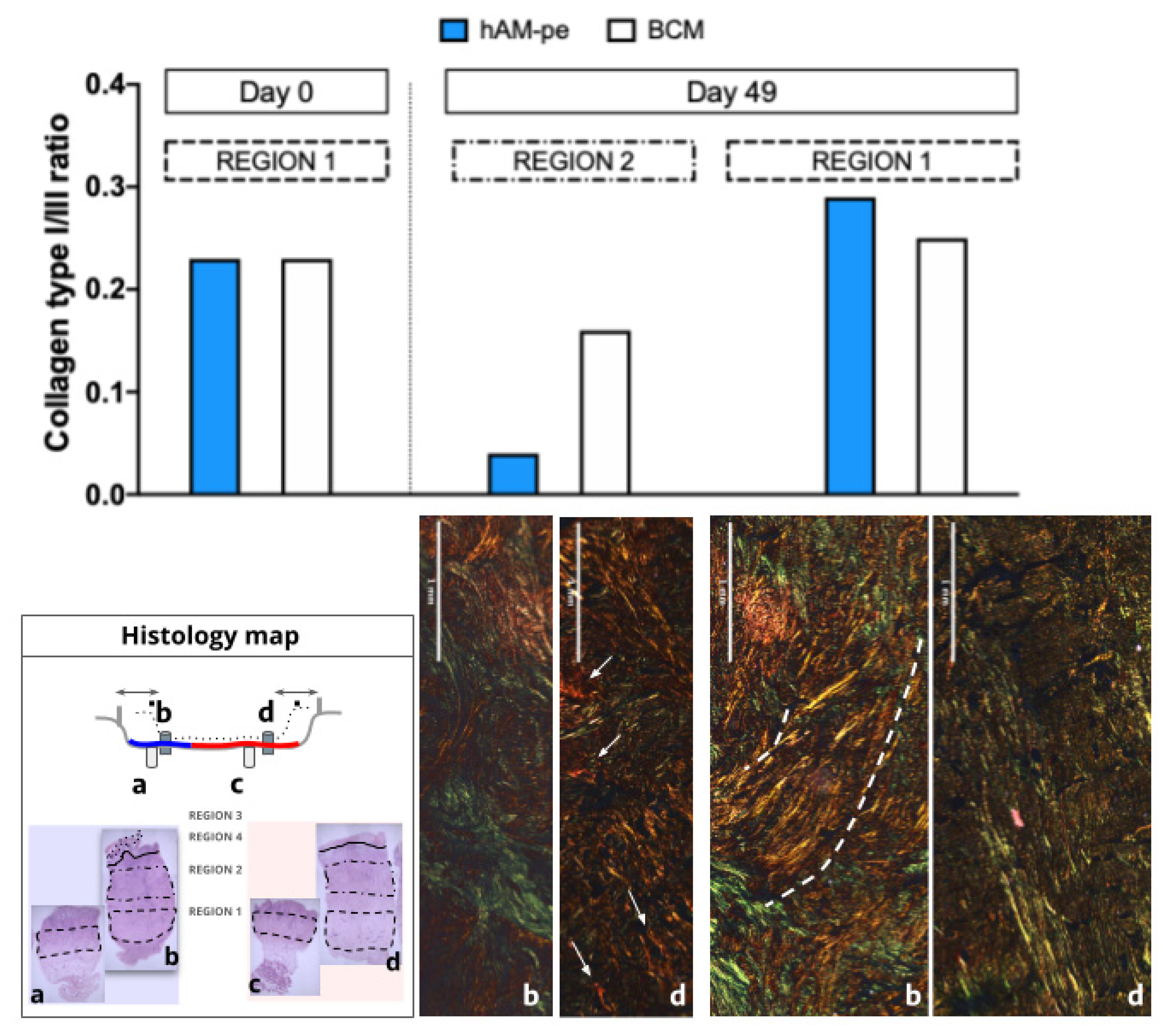

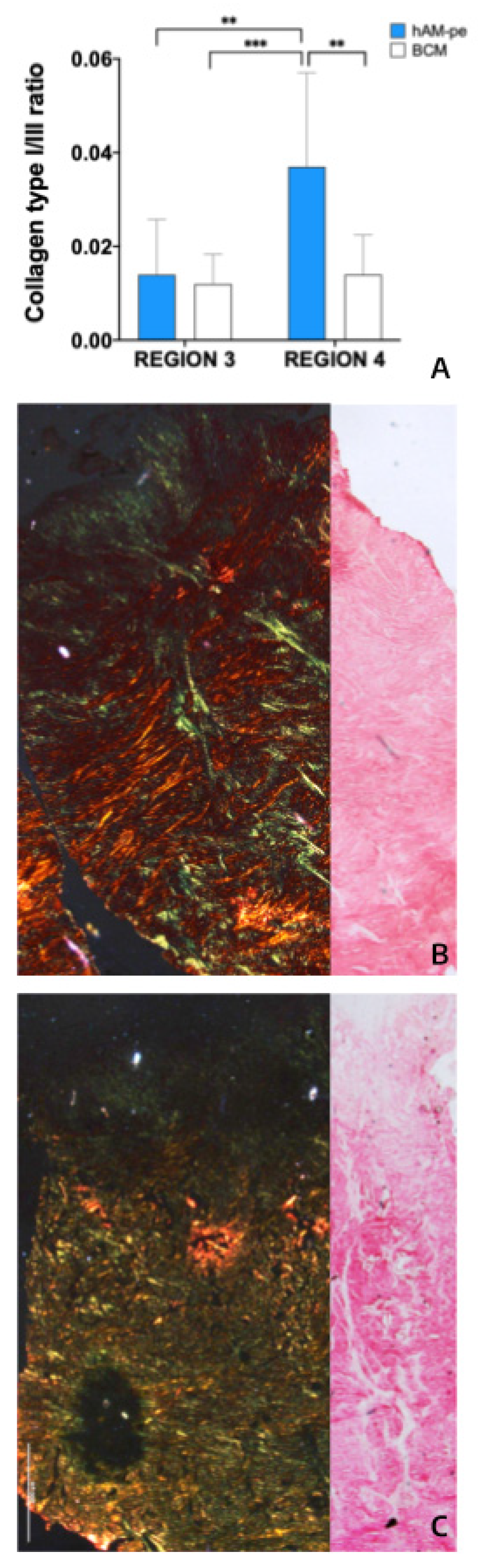

3.2. The treatment with hAM-pe improves the deposition and organization of the extracellular matrix

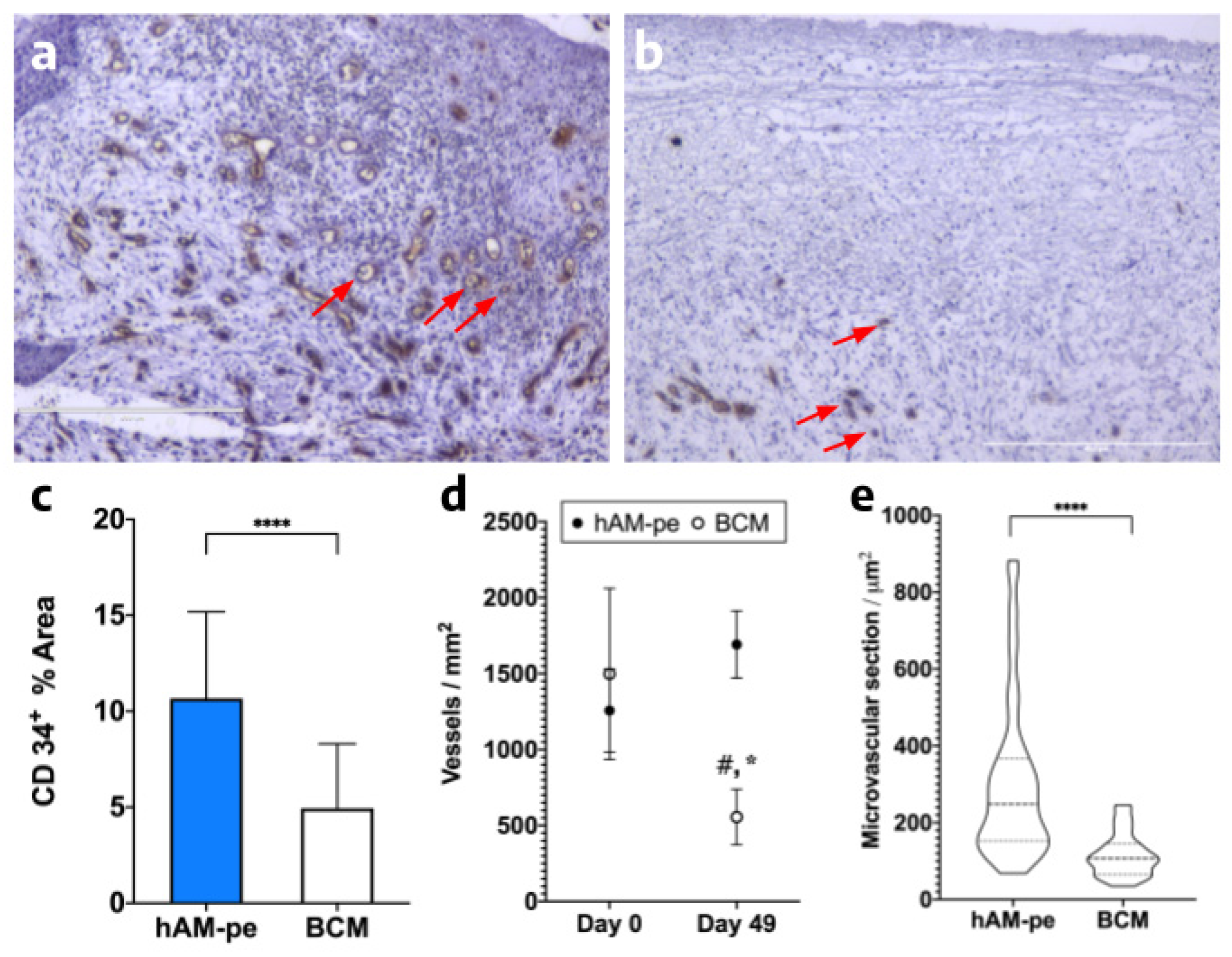

3.3. The hAM-pe treatment promotes angiogenesis and vascularization in the repair tissue

3.4. Tissues repaired under the action of hAM-pe are likely in a more advanced stage of wound healing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| α-SMA | Alpha-Smooth Muscle Actin |

| ANMAT | National Administration of Drugs, Food, and Medical Technology (Argentina) |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| APCs | Antigen-Presenting Cells |

| Arg-1 | Arginase-1 |

| BCM | Bovine Collagen Matrix |

| CCL2 | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 (Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1, MCP-1) |

| CD34 | Cluster of Differentiation 34 (marker of hematopoietic and endothelial progenitor cells) |

| col1a1 | Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain |

| col1a2 | Collagen Type I Alpha 2 Chain |

| col3a1 | Collagen Type III Alpha 1 Chain |

| Ct | Threshold Cycles |

| CXCL-10 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 10 (Interferon gamma-induced protein 10) |

| DAMPs | Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| DFU | Diabetic Foot Ulcer |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| FAP | Fibroblast Activation Protein |

| hAM | Human Amniotic Membrane |

| hAM-pe | Lyophilized homogenized human amniotic membrane dressings sterilized by gamma radiation |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1 beta |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 |

| INCUCAI | National Central Unique Institute for Ablation and Implant Coordination (Argentina) |

| MMP-1 | Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 |

| MMP-2 | Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| TIMP-1 | Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases-1 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| VAC | Vacuum-Assisted Closure |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

References

- Robson, M.C.; Steed, D.L.; Franz, M.G. Wound healing: Biologic features and approaches to maximize healing trajectories. Curr. Probl. Surg. 2001, 38, A1–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.; Shih, S.; Khachemoune, A. Skin substitutes for acute and chronic wound healing: an updated review. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2020, 31, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velnar, T.; Bailey, T.; Smrkolj, V. The Wound Healing Process: An Overview of the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. J. Int. Med. Res. 2009, 37, 1528–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, I.C.; Takejima, A.L.; Simeoni, R.B.; Gamba, L.K.; Ribeiro, V.S.T.; Foltz, K.M.; de Noronha, L.; de Almeida, M.B.; Neto, J.R.F.; de Carvalho, K.A.T.; et al. Acellular Biomaterials Associated with Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Mononuclear Stem Cells Improve Wound Healing through Paracrine Effects. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, M.; Sahin, K.B.; West, Z.E.; Murray, R.Z. Macrophage Phenotypes Regulate Scar Formation and Chronic Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Yu, Z.; Liu, B.; Song, B.; Su, Y. The clinical dynamic changes of macrophage phenotype and function in different stages of human wound healing and hypertrophic scar formation. Int. Wound J. 2018, 16, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauglitz, G.G.; Korting, H.C.; Pavicic, T.; Ruzicka, T.; Jeschke, M.G. Hypertrophic Scarring and Keloids: Pathomechanisms and Current and Emerging Treatment Strategies. Mol. Med. 2010, 17, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoedler, S.; Broichhausen, S.; Guo, R.; Dai, R.; Knoedler, L.; Kauke-Navarro, M.; Diatta, F.; Pomahac, B.; Machens, H.-G.; Jiang, D.; et al. Fibroblasts – the cellular choreographers of wound healing. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1233800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Marin, S. , Kern, T., Hofmann, N., Pogozhykh, O., Framme, C., Börgel, M.,... & Gryshkov, O. (2021). Human Amniotic Membrane: A review on tissue engineering, application, and storage. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials, 109(8), 1198-1215.

- Khosravimelal, S. , Momeni, M., Gholipur, M., Kundu, S. C., & Gholipourmalekabadi, M. (2020). Protocols for decellularization of human amniotic membrane. In Methods in Cell Biology (Vol. 157, pp. 37-47). Academic Press.

- De Angelis, B. , Orlandi, F., Morais D’Autilio, M. F. L., Di Segni, C., Scioli, M. G., Orlandi, A.,... & Gentile, P. (2019). Vasculogenic chronic ulcer: tissue regeneration with an innovative dermal substitute. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(4), 525.

- Carro, G.V.; Guerbi, X.; Berra, M.; Rodriguez, M.G.; Noli, M.L.; Fuentes, M.; Ticona, M.A.; Michelini, F.; Berra, A. Homogenized and Lyophilized Amniotic Membrane Dressings for the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers in Ambulatory Patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2024, 45, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringa, P.; Romanin, D.; Lausada, N.; Gobbi, R.P.; Zanuzzi, C.; Martín, P.; Abate, J.C.; Cabanne, A.; Arnal, N.; Vecchio, L.; et al. Gut Permeability and Glucose Absorption Are Affected at Early Stages of Graft Rejection in a Small Bowel Transplant Rat Model. Transplant. Direct 2017, 3, e220–e220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, A.; Pilacinski, S.; Zozulinska-Ziolkiewicz, D.; Gandecka, A.; Grzelka, A.; Konwerska, A.; Malinska, A.; Nowicki, M.; Araszkiewicz, A. An increased skin microvessel density is associated with neurovascular complications in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2019, 16, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumbo, M.; Sierro, F.; Debard, N.; Kraehenbuhl, J.-P.; Finke, D. Lymphotoxin β receptor signaling induces the chemokine CCL20 in intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardeazabal, L.; Izeta, A. Elastin and collagen fibres in cutaneous wound healing. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e15052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campelo, M.B.D.; Santos, J.d.A.F.; Filho, A.L.M.M.; Ferreira, D.C.L.; Sant’anna, L.B.; de Oliveira, R.A.; Maia, L.F.; Arisawa, E.Â.L. Effects of the application of the amniotic membrane in the healing process of skin wounds in rats. Acta Cir. Bras. 2018, 33, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, L.C.U.; Bignolas, G.; Brentani, R.R. Picrosirius staining plus polarization microscopy, a specific method for collagen detection in tissue sections. Histochem. J. 1979, 11, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Padilla, C.M.L.; Coenen, M.J.; Tovar, A.; De la Vega, R.E.; Evans, C.H.; Müller, S.A. Picrosirius Red Staining: Revisiting Its Application to the Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment of Collagen Type I and Type III in Tendon. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2021, 69, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew-Steiner, S. S., Roy, S., & Sen, C. K. (2021). Collagen in wound healing. Bioengineering, 8(5), 63.

- Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Mao, J.; Su, Y.; Huang, X.; Xia, W.; Leng, X.; Zan, T. Immunomodulation of wound healing leading to efferocytosis. Smart Med. 2024, 3, e20230036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.B.; Sporn, M.B.; Assoian, R.K.; Smith, J.M.; Roche, N.S.; Wakefield, L.M.; I Heine, U.; A Liotta, L.; Falanga, V.; Kehrl, J.H. Transforming growth factor type beta: rapid induction of fibrosis and angiogenesis in vivo and stimulation of collagen formation in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1986, 83, 4167–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, J. T. , Ramalingam, T. R., Mentink-Kane, M. M., Wilson, M. S., El Kasmi, K. C., Smith, A. M.,... & Wynn, T. A. (2009). Arginase-1–expressing macrophages suppress Th2 cytokine–driven inflammation and fibrosis. PLoS pathogens, 5(4), e1000371.

- Murray, P.J.; Wynn, T.A. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S. A., & DiPietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of dental research, 89(3), 219-229.

- Jain, R.K. Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veith, A.P.; Henderson, K.; Spencer, A.; Sligar, A.D.; Baker, A.B. Therapeutic strategies for enhancing angiogenesis in wound healing. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 146, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shams, F.; Moravvej, H.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Mostafavi, E.; Bayat, H.; Kazemi, B.; Bandehpour, M.; Rostami, E.; Rahimpour, A.; Moosavian, H. Overexpression of VEGF in dermal fibroblast cells accelerates the angiogenesis and wound healing function: in vitro and in vivo studies. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, P.; Kodra, A.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Golinko, M.S.; Ehrlich, H.P.; Brem, H. The Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Wound Healing. J. Surg. Res. 2009, 153, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauchenwald, T.; Handle, F.; Connolly, C.E.; Degen, A.; Seifarth, C.; Hermann, M.; Tripp, C.H.; Wilflingseder, D.; Lobenwein, S.; Savic, D.; et al. Preadipocytes in human granulation tissue: role in wound healing and response to macrophage polarization. Inflamm. Regen. 2023, 43, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Biswas, S.K.; Galdiero, M.R.; Sica, A.; Locati, M. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue repair and remodelling. J. Pathol. 2012, 229, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, A. J. , & Kolter, J. (2023). Isolation and Flow Cytometry Analysis of Macrophages from the Dermis. In Tissue-Resident Macrophages: Methods and Protocols (pp. 159-169). New York, NY: Springer US.

- Jenkins, S.J.; Ruckerl, D.; Cook, P.C.; Jones, L.H.; Finkelman, F.D.; van Rooijen, N.; MacDonald, A.S.; Allen, J.E. Local Macrophage Proliferation, Rather than Recruitment from the Blood, Is a Signature of T H 2 Inflammation. Science 2011, 332, 1284–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschalidi, S.; Mehrotra, P.; Keçeli, B.N.; De Cleene, H.K.L.; Lecomte, K.; Van der Cruyssen, R.; Janssen, P.; Pinney, J.; van Loo, G.; Elewaut, D.; et al. Targeting SLC7A11 improves efferocytosis by dendritic cells and wound healing in diabetes. Nature 2022, 606, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.-C. Mechanobiology of tendon. J. Biomech. 2006, 39, 1563–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somaiah C, Kumar A, Mawrie D, Sharma A, Patil SD, Bhattacharyya J, Swaminathan R, Jaganathan BG. Collagen promotes higher adhesion, survival and proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2015; 10(12):e0145068.

- Merkel JR, DiPaolo BR, Hallock GG, Rice DC. Type I and type III collagen content of healing wounds in fetal and adult rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 4: 1988;187(4), 1988.

- Volk, S.W.; Wang, Y.; Mauldin, E.A.; Liechty, K.W.; Adams, S.L. Diminished Type III Collagen Promotes Myofibroblast Differentiation and Increases Scar Deposition in Cutaneous Wound Healing. Cells Tissues Organs 2011, 194, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraman, M.; Bambrough, P.J.; Arnold, J.N.; Roberts, E.W.; Magiera, L.; Jones, J.O.; Gopinathan, A.; Tuveson, D.A.; Fearon, D.T. Suppression of Antitumor Immunity by Stromal Cells Expressing Fibroblast Activation Protein–α. Science 2010, 330, 827–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, A.A.; Weiner, L.M. The role of fibroblast activation protein in health and malignancy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 783–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, J. Fibroblasts—Warriors at the Intersection of Wound Healing and Disrepair. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.G.S.; Díaz, N.F.; López, G.G.; Maya, I.Á.; Jimenez, C.H.; Maldonado, Y.R.; Aguayo, D.J.M.; Martínez, N.E.D. Evaluation methods for decellularized tissues: A focus on human amniotic membrane. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2024, 139, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogami, H.; Kishore, A.H.; Akgul, Y.; Word, R.A. Healing of Preterm Ruptured Fetal Membranes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13139–13139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paz Lugo, P. (2006). Estimulación de la síntesis de colágeno en cultivos celulares. Posible tratamiento de enfermedades degenerativas mediante la dieta [tesis]. Granada: Universidad de Granada.

| Amplicon | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

| β-actin | CCT GGC ACC CAG CAC AAT | GCC GAT CCA CAC GGA GTA CT |

| IL-1β | TAC GAA TCT CCG ACC ACC ACT ACA G | TGG AGG TGG AGA GCT TTC AGT TCA TAT G |

| TNF-ɑ | AAC CTC CTC TCT GCC ATC AA | CCA AAG TAG ACC TGC CCA GA |

| TGF-β | ACC CAC AAC GAA ATC TAT GAC | GCT CCA CTT TTA ACT TGA GCC |

| Arginase 1 | GTT TCT CAA GCA GAC CAG CC | GCT CAA GTG CAG CAA AGA GA |

| VEGF | CAC TGC CTG GAA GAT TCA | TGG TTT CAA TGG TGT GAG GA |

| CCL-2 | CGC CTC CAG CAT GAA AGT CT | ATG AAG GTG GCT GCT ATG AGC |

| IL-8 | CAC CGG AAG GAA CCA TCT CA | GGA AGG CTG CCA AGA GAG C |

| CXCL-10 | TCC ACG TGT TCA GAT CAT TGC | TGA TGG CCT TCG ATT CTG G |

| COL1A1 | CGA AGA CAT CCC ACC AAT CAC | TCA TCG CAC AAC ACC TTG C |

| COL1A2 | ACC TCA GGG TGT TCA AGG TG | CTT CTC CAG CGG TAC CAG AG |

| COL3A1 | CTG GTC CTG TTG GTC CAT CT | ACC TTT GTC ACC TCG TGG AC |

| FAP | ATG AGC TTC CTC GTC CAA TTC A | AGA CCA CCA GAG AGC ATA TTT TG |

| ɑ-SMA | AGG GAG TAA TGG TTG GAA TGG | TGA TGA TGC CGT GTT CTA TCG |

| MMP-1 | TCG CTG GGA GCA AAC ACA | TTG GCA AAT CTG GCG TGA A |

| MMP-2 | CCT CTC CAC TGC CTT CGA TA | GCC TGG GAG GAG TAC AGT CA |

| TIMP-1 | CGC TGA CAT CCG GTT CGT | GTG GAA GTA TCC GCA GAC ACT CT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).