1. Literature Review of Life Cycle Assessment of Alternative Aviation Fuels

The climate impact of aircraft comprises CO

2 and non-CO

2 effects (soot, aerosol, sulphate, water vapour, oxides of nitrogen [NO

x], and contrails and cirrus clouds) [

1,

2,

3]. Presently, aviation contributes 3.5% to the overall anthropogenic radiative forcing [

1,

2], of which approximately two-thirds is attributable to non-CO

2 effects [

3]. The industry foresees a doubling in air travel demand over the next two decades (2024 - 2043) even considering the effects of the pandemic [

4], which is expected to substantially increase its climate impact. It is projected that advancements in aircraft technology and the adoption of low-carbon fuels could collectively address 80% of the measures necessary for achieving carbon-neutral growth [

5,

6].

The total life cycle emissions associated with aircraft fuel performance encompass emissions from both the operational phase of the aircraft and the manufacturing stage of the fuel (from raw material extraction to fuel storage). According to research by Chester and Horvath [

7], the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions during the operational phase of aircraft account for approximately 70% of the total GHG emissions from the Jet-A aircraft. Presently, technological advancements and regulatory efforts in aviation are primarily focused on the use phase or direct operation of aircraft. The Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Technologies (GREET) model, developed by Argonne National Lab, USA, is one of the many tools for comprehensive life cycle assessment.

Not all alternative fuel pathways are equally energy efficient when considering their embodied emissions. For instance, from a conventional standpoint focusing on direct emissions, liquid hydrogen (LH

2) appears promising for aviation due to its higher energy density and zero-carbon emissions during aircraft operation, compared to conventional Jet-A fuel. However, using the GREET model [

8], it is observed that LH

2 derived from coal emits three times more CO

2 emissions over its life cycle compared to Jet-A. According to the aviation industry [

9], evaluating the ‘sustainability’ of aviation fuels should include life cycle assessment , taking into account net emissions throughout the entire life cycle of the fuel.

Decarbonizing long-haul aviation poses significant challenges [

6,

10]. Based on the authors’ previous work [

6,

11,

12,

13], it was observed that decarbonising the long-range aviation sector is challenging, and of the several alternative energy carriers and propulsion technologies examined (including batteries and fuel cells) for aircraft operational performance, LH

2 and 100% synthetic paraffin kerosene (SPK) or sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) are the only two alternatives to Jet-A for a large twin aisle (LTA) aircraft, whether tube-wing or blended wing body (BWB) airframes. Presently, 100% SPK is not permitted for use in the existing aircraft fleet. Approved drop-in fuels for civil aviation use include up to a 50% blend of alcohol-to-jet (ATJ), Fischer-Tropsch (FT), and hydro-processed renewable or hydro-processed esters and fatty acids (HRJ or HEFA) SPK pathways, as well as a 10% blend of sugar-to-jet (STJ) SPK pathway [

6,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Studies by Proesmans et al. [

18,

19] examine the climate impacts of aircraft powered by SPK and LH

2, including the impacts of contrails, but the analysis is restricted to the operational phase of the aircraft. The embodied energy/emissions associated with alternative fuel production also need to be considered for estimating greener production pathways. Therefore, a holistic approach needs to be used for evaluating the performance of future aircraft technology and energy vector combinations. This is also supported by review studies [

20,

21,

22] which establish the need for an integrated methodological framework that should consider life-cycle impacts of aircraft performance towards the goal of sustainable aviation. Therefore, in the present study, a life cycle approach is used for identifying fuel feedstock and/or manufacturing pathway combination(s) that could enable a climate-neutral long-range flight of an LTA aircraft powered by LH

2 and 100% SPK (separately). The scope of this work is limited to fuel life cycle assessment of combustion-based long-range LTA aircraft fuelled by LH

2 and 100% SPK (separately), and the following literature review will focus on it.

Different studies conduct life cycle or well-to-wake (WTWa) emissions analysis for SPK and LH

2 fuel for specific aircraft range applications – fossil fuel based SPK fuel [

23], bio-jet fuel [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

42,

43,

44,

45], power-to-liquid (PtL) or electro-fuel [

29,

31,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55], and LH

2 [

30,

31,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. None of these studies [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62], [

27,

28,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63], examine different types of feedstocks and manufacturing pathway combination(s) that could enable a climate-neutral long-range flight of an LTA aircraft powered by LH

2 and 100% SPK (bio-jet and PtL fuel), and not all of these consider non-CO

2 emissions in their WTWa analysis. The important findings and/or limitations of these studies are concisely reviewed below, and a detailed review of some of these studies is included in Supplementary Information (SI) File SI §1. For details in terms of different manufacturing pathways and processes, properties, operability issues, and other miscellaneous aspects of these alternative fuels, the reader is advised to explore studies by Su-ungkavatin et al. [

64], Cabrera et al. [

65], Ansell [

34], and Braun et al. [

33].

Lau et al. [

32] review HEFA and ATJ bio-jet fuel and find that the WTWa GHG emissions reduction potential of HEFA (from jatropha and palm oil) and ATJ (from wheat grain and wheat straw) could be 19% – 42% and 20% – 65%, respectively. According to Braun et al. [

33], FT SPK fuel from miscanthus (silver grass), forestry and agricultural residues, and municipal solid waste, has the highest potential to decrease WTWa GHG emissions (90% – 100%). In some regions, GHG emissions reduction could be as high as 125%. The median reduction potentials of ATJ pathways are about 60%, while those of HEFA are below 60%. A review study by Ansell [

34] examines different studies on bio-jet fuel and hydrogen produced from steam methane reforming (SMR) and electrolysis (using renewable electricity) which do not consider climate impacts of non-CO

2 emissions in their life cycle assessment . Ansell finds that bio-jet fuel and renewable hydrogen has the potential to decrease the WTWa CO

2 emissions by 68% and ~80%, respectively, with a fully renewable grid. The above studies [

32,

33,

34] do not consider the non-CO

2 emissions in their analysis. Afonso et al. [

35] and Song et al. [

36] observe that bio-jet fuel can reduce WTWa GHG emissions by up-to 80% (with non-CO

2 emissions) and 41–89% (without non-CO

2 emissions), compared to Jet-A. The reduction in WTWa GHG emissions depends on the feedstock and manufacturing pathways. The above studies consider limited/selective feedstocks for producing alternative fuels.

A study by Kolosz et al. [

23] is limited to blended/drop-in SPK fuel, where a comparison of WTWa performance metrics is conducted for: fossil fuel based SPK fuel (from coal, oil sands, oil shale, natural gas, etc.), and bio-jet fuel (first, second, and third generation). Studies by Wei et al. [

24], Pavlenko et al. [

25] (also reviewed in [

37]), and De Jong et al. [

26] conduct WTWa emission of bio-jet fuel only for few selected biomass feedstocks. Similarly, studies [

27], [

28] are focussed only on bio-jet fuel and they explore only the feedstocks considered in CORSIA database (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation). A study by Van Der Sman et al. [

29] reviews WTWa emission of SPK fuel (both bio-jet fuel and PtL) but this analysis is restricted to EU region. Similarly, Saad et al. [

38] observe that PtL and bio-jet fuel could reduce ~50% WTWa emission, but the study is limited to Switzerland. All of the above studies [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

38] do not consider the climate impact of non-CO

2 emissions (from the aircraft’s operational phase) in their WTWa analysis.

Grim et al. [

48] observe that PtL could decrease WTWa GHG emissions by 66% – 94% (without non-CO

2 emissions). According to Sacchi et al. [

49], PtL fuel from direct air capture and carbon storage could reduce WTWa GHG emissions by 65% – 100% (including non-CO

2 emissions). A study by Micheli et al. [

51] examines PtL fuel produced from wind power and finds that the WTWa GHG emissions could be reduced by 27.6% – 46.2% (with non-CO

2 effects) and 52.6% – 88.9% (without non-CO

2 effects), but this study is limited to Germany’s energy landscape. Similar observations are made by Papantoni et al. [

50], where the authors find that inclusive of the non-CO

2 emissions, PtL from solar and wind energy could reduce WTWa GHG emissions by 32% and 42%, respectively. According to Klenner et al. [

52], using wind power, the WTWa GHG emission reduction potential (including non-CO

2 emissions) of PtL fuel is 48% and of LH

2 fuel is 44% for short flights (<200 km), and for longer flights, the average WTWa GHG emission reduction potential increases to 52% (for PtL) and 54% (for LH

2). These findings are limited to Norway’s energy mix. Studies by VanLandingham [

53] and VanLandingham et al. [

54], examine the performance of PtL and LH

2 (both fuels are produced from renewable power) in a single aisle aircraft (Boeing 737) and find that the WTWa GHG emissions (including non-CO

2 emissions) could be reduced by 43% and 61%, respectively. Similarly, a study by Prashanth et al. [

55] finds that the WTWa GHG emission reduction potential (including non-CO

2 emissions) of LH

2 could be 91% (from solar energy) to 98% (from wind energy) and PtL 84% (from solar energy) to 93% (from wind energy). Studies [

46,

47] are limited to WTWa emission of PtL or electro-fuel in Germany’s energy landscape having ~100% WTWa GHG reduction potential in the future energy mix. The analysis in the above studies [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55] are limited to a specific energy landscape and/or limited feedstocks are explored to produce the fuel under consideration. The life cycle GHG performance of PtL is dependent on the sourcing of CO

2 (direct air capture or point sourcing), and of PtL and LH

2 is dependent on the type of electricity mix.

Delbecq et al. [

40] evaluate the WTWa performance of bio-jet fuel, PtL, and hydrogen with different scenarios at aviation system level for a small aircraft. The individual potential of each of the fuels in terms of WTWa GHG reduction is not known. Additionally, the sourcing of feedstock for bio-jet fuel is not known, and PtL and hydrogen are sourced only from renewable energy. Fantuzzi et al. [

41] examine different alternative aviation fuels but consider limited feedstock/pathways for bio-jet fuel (HEFA and ATJ), PtL, and hydrogen (SMR and electrolysis using renewable electricity) and these offer up-to 70% savings in WTWa GHG (without non-CO

2 emissions). Additionally, the study is limited to the UK energy landscape. Another study by Dray et al. [

42] evaluates different alternative aviation fuels and their WTWa effects including non-CO

2 emissions. The authors examine bio-jet fuel (ATJ, HEFA, and FT), PtL (using direct air capture), and hydrogen (electrolysis using renewable power). They observe that considering the ongoing efficiency improvements and efforts to avoid contrails, but excluding offsets, the energy transition could cut WTWa GHG emissions by 89–94% compared to 2019 levels. This reduction would be achieved while considering 2 – 3 times increase in demand by 2050. Despite being a detailed analysis with 2050 forecast, the study examines limited/selective feedstocks for each of the fuel examined. Quante et al. [

43] examine alternative aviation fuels and observe that FT SPK, PtL, HEFA SPK, ATJ SPK, STJ SPK, and hydrogen could reduce WTWa GHG emissions (without non-CO

2 emissions) by 85%, 100%, 54%, 62%, 61%, and 80%, respectively. However, the specific feedstocks used for producing bio-jet fuels are unknown. Another study by Penke et al. [

39] observe that PtL, bio-jet fuel (HEFA) from soy oil, and renewable hydrogen could reduce WTWa GHG emission (without non-CO

2 emissions) by 77%, 30%, and 95%, respectively. Similarly, Kossarev et al. [

44] (continuing their previous work [

45]) restrict their study to renewable hydrogen, algae-based HEFA bio-jet fuel, and hydrogenated vegetable oil, which have WTWa GHG emission reduction potential (including non-CO

2 emissions) of 59.5%, 35.8%, and 112%, respectively. The above studies [

39,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45] focus on a particular energy landscape and/or explore limited feedstocks for producing the fuel in consideration.

Studies [

34,

37,

41,

43,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

66,

67] on hydrogen as an aviation fuel do not consider non-CO

2 emissions in their WTWa analysis which are important, and studies [

56,

61,

62,

66,

67,

68,

69] limit their selection of feedstock/pathway for fuel production only to renewable power. The aircraft use-phase energy consumption and/or emissions have a significant impact on the WTWa performance. Studies [

34,

37,

39,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62] are focussed on the life cycle effects of hydrogen use in aircraft, it is either not clear from the information supplied or these do not consider the poor volumetric energy density characteristic of LH

2 which penalises aircraft energy performance, which are their limitations. A study by Koroneos et al. [

56] that examines an A320 (or single aisle) type of aircraft though considers realistic effects of LH

2 on aircraft design, is less recent (from early 2000s) and considers fewer ways of LH

2 production. Another study by Mukhopadhaya et al. [

61] examines PtL, and LH

2 from electrolysis (renewable energy) and observes that ~100% reduction in WTWa GHG emission could be achieved (without non-CO

2 emissions). Tveitan [

66] examines green hydrogen which has a 58% WTWa GHG emission (excluding non-CO

2 emissions) reduction potential. Chan et al. [

67] evaluate green hydrogen and bio-jet fuel (feedstock sourcing unknown), and find that bio-jet fuel and hydrogen have the best potential and can achieve up to 88% WTWa GHG emissions reduction. It is also unclear, or the above studies do not consider the non-CO

2 emissions in their WTWa analysis.

Studies by Miller [

30] and Miller et al. [

63] include more number of feedstocks and pathways than the above studies, as consideration is given to tens of feedstocks and/or pathways for LH

2 and bio-jet fuel along with the effect of contrails cirrus in WTWa analysis. However, PtL or electro-fuels and STJ pathway are omitted, and the WTWa results are limited only to a smaller aircraft with shorter range compared to LTA aircraft which is the focus of this work. Lastly, the FlyZero report [

31] accounts the performance penalty due to cryogenic tank installation and non-CO

2 emissions in their WTWa analysis of LH

2, PtL and bio-jet fuel SPK for small to mid-size aircraft. However, their analysis is limited to a few feedstocks and/or pathways of manufacturing LH

2, PtL and bio-jet fuel SPK.

Not all of the above studies [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

70,

71,

72] consider non-CO

2 emissions in their WTWa analysis and none of these examine different types of feedstocks and manufacturing pathway combination(s) that could enable a climate-neutral long-range flight of an LTA aircraft powered by LH

2 and 100% SPK (bio-jet and PtL fuel). According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA) [

73], reaching net-zero CO

2 emissions by 2050 could involve the following contributions: SAF at 65%, new aircraft technology, including electric and hydrogen aircraft, at 13%, infrastructure and operational efficiencies at 3%, and offsets and carbon capture at 19%. Carbon removal is identified as an important strategy to reduce GHG emission. None of the above studies consider fuel production routes that employ carbon capture and storage (CCS), except a study by Fantuzzi et al. [

41] which shows that by employing carbon capture and storage for SMR LH

2 production route can reduce the WTWa GHG emissions by 60% (median value). Also, according to the study by Pavlenko et al. [

74], hydrogen is a crucial component in the SPK fuel manufacturing process and thus has a significant impact on the life cycle GHG emissions of SPKs (bio-jet and PtL fuel) and using green hydrogen in SPK production could help reducing the WTWa GHG emissions. None of the studies reviewed above considers the sensitivity of hydrogen production to the WTWa GHG emissions of SPKs. Furthermore, above studies do not provide any estimation of the energy demand in 2050 for the long-haul aviation sector, and whether or not that energy demand can be met with 100% SPK (or SAF) and/or LH

2.

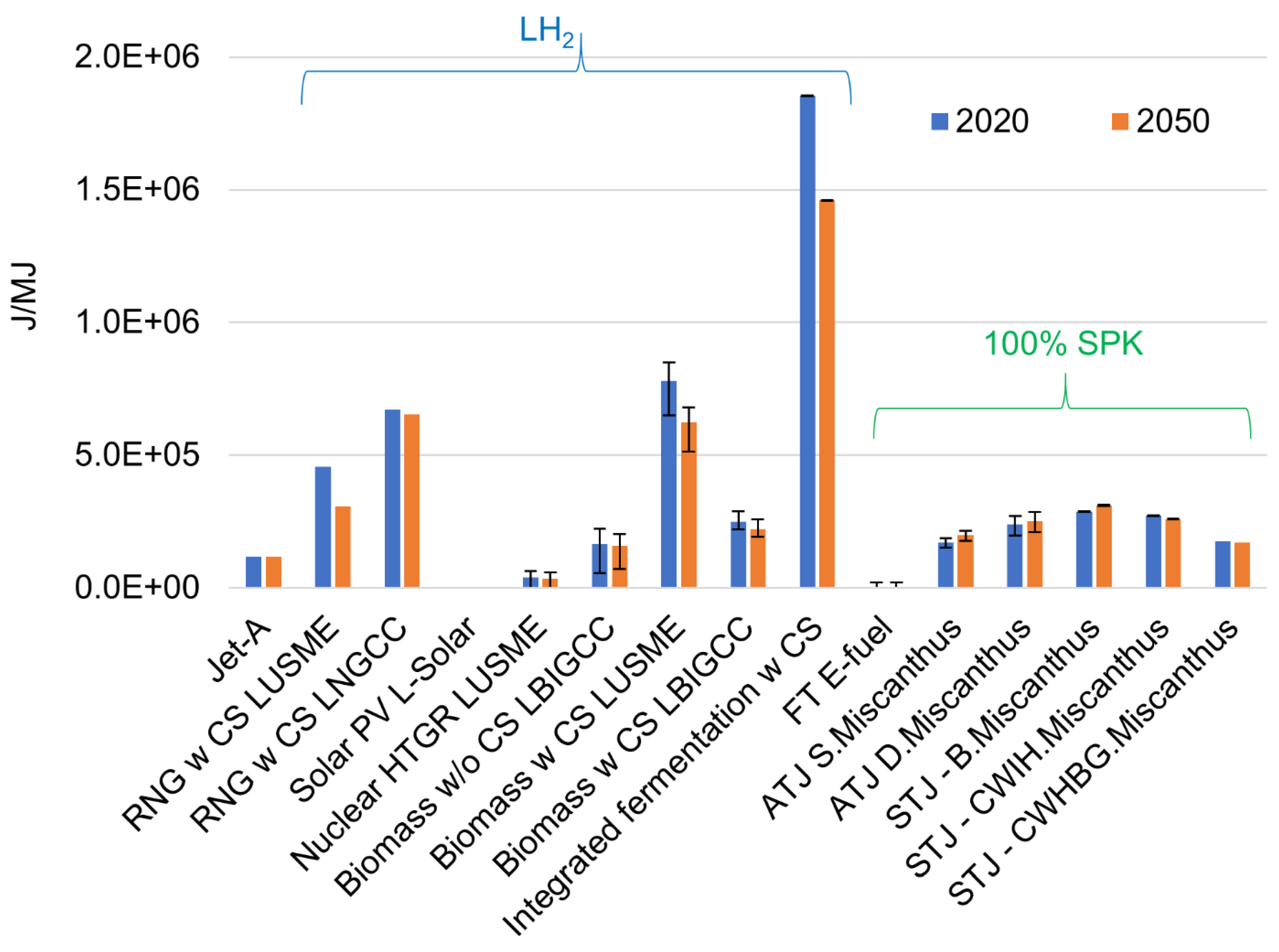

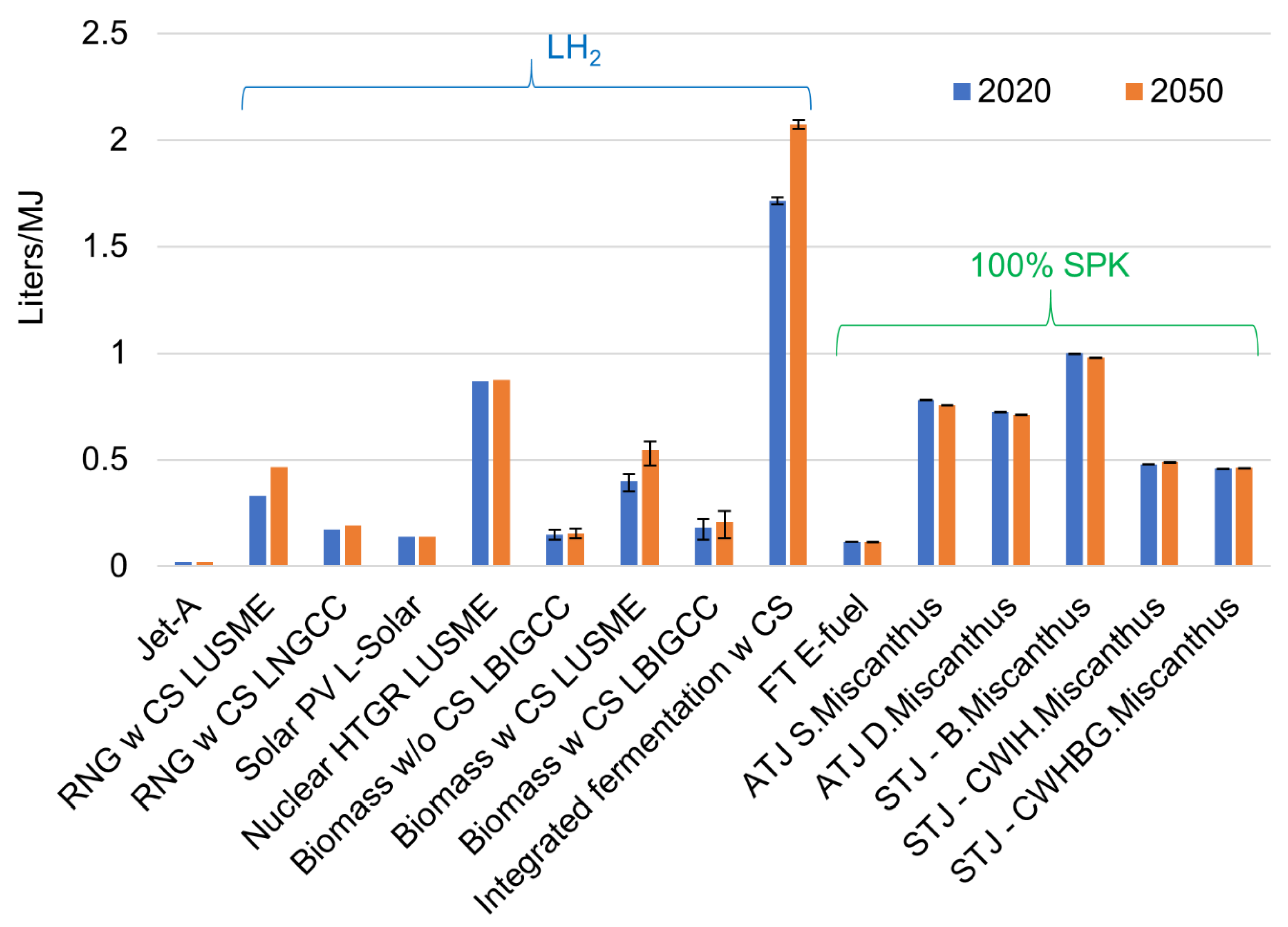

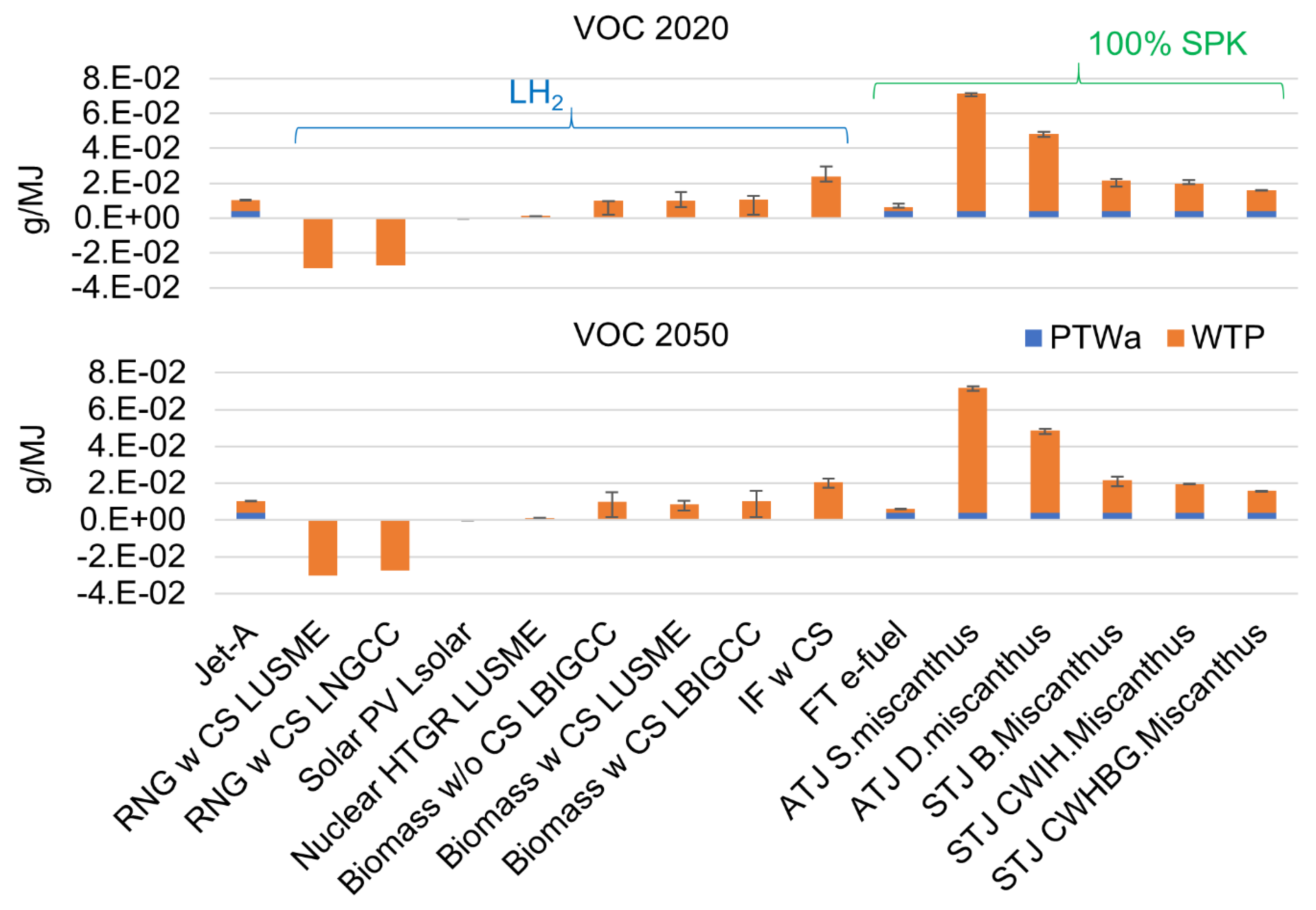

The above limitations in literature motivate this current work. In this work, the primary research effort is to estimate the life cycle or WTWa GHG performance while addressing non-CO2 emissions, for a long-range LTA aircraft (separately) powered by LH2 and 100% SPK (bio-jet and PtL fuel) manufactured from over 100 different feedstocks and/or pathways, where in some cases carbon capture and storage is also employed. Additionally, the sensitivity of hydrogen sourcing to SPK production, and of biomass sourcing for some hydrogen production pathways, are investigated in this work. Similarly, this work explores the sensitivity of energy mix (2020 vs 2050) to alternative fuel production. Furthermore, the energy demand and supply (of 100% SPK [or SAF] and LH2) in future (2050) for long-haul aviation is considered. These are novel contributions of the present work.

In authors’ previous studies [

12,

13], the engine (ultrahigh bypass ratio geared turbofan) and aircraft operational energy performance modelling of a 2030+ (N+2 timeframe) BWB LTA aircraft powered by LH

2 and 100% SPK (separately) are conducted considering penalty due to cryogenic tank installation for LH

2 aircraft modelling. This enables the estimation of GHG emissions in the aircraft use-phase. Knowing the fuel manufacturing emissions, the WTWa or life cycle emissions can be calculated. In this work, over 100 different ways in total (including fuel manufacturing unit that employs carbon capture and storage) for producing LH

2, PtL, and bio-jet fuel SPK are examined (for use in the N+2 BWB aircraft).

Not all bio-jet fuels (i.e. fuel from different production pathways) can be directly used in the present aircraft (called ‘drop-in’ fuels), because some of fuel properties and chemical contents are not same as that of the conventional jet fuel [

75]. Some systems within the aircraft are designed considering the properties of conventional jet fuel. For example: The aromatic content of conventional jet fuel causes rubber seals used in the high-pressure fuel system to swell, thereby preventing fuel leakage during aircraft operation at different altitudes; and synthetic paraffin kerosene (SPK) jet fuel cannot be used in neat form (100%) without modifications to aircraft or without addition of synthetic aromatics/additives [

75]. The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) has approved four bio-jet fuel pathways which can be used in aircraft as ‘drop-in’ fuels [

76]. These are:

Fischer Tropsch (FT) SPK (FT-SPK) with maximum 50% blend and syngas FT with aromatic alkylation (FT-SPK/A) with maximum 50% blend

Hydro-processed renewable jet fuel (HRJ) or hydro-processed ester and fatty acids (HEFA) (HRJ/HEFA-SPK) with maximum 50% blend

Bio-chem sugars or hydro-processed fermented sugars to synthetic iso-paraffins with maximum 10% blend (also referred to as sugar-to-jet fuel or STJ), and

Alcohol-to-jet (ATJ-SPK) fuel with maximum 50% blend (recently revised from 30% blending)

where the blending is done with the conventional jet fuel. 100% SPK (biomass-based and electro-fuel) is not strictly a drop-in fuel as it has not yet been approved.

A study by Wei et al. [

24] reviews different bio-jet fuel types produced from different feedstocks. The authors carry out a comparison of holistic life cycle (well-to-wake [WTWa]) greenhouse gas (GHG) emission for the fuel type and feedstock combinations, which is summarised in

Table 1 (also includes use-phase GHG emissions [without the effect of contrails]). The GHG life cycle assessment is carried out at an industrial level and the GHG emission comprise of following process components:

Feedstock cultivation, harvesting, and transportation

Land use effect

Production and transportation of ancillary chemicals

Refining

Transport, distribution, storage, and the combustion of the fuel

Additionally, the authors carry out a cost comparison of some of the fuel type and feedstock combinations (from

Table 1) and this is summarised in

Table 2. It can be observed from

Table 1 and

Table 2 i.e., considering both holistic life cycle GHG emission [carbon dioxide (CO

2) equivalent] and fuel cost, that HEFA-camelina oil and HEFA-waste oils and animal fat are the preferred candidates of fuel type and feedstock combinations followed by ATJ-sugarcane (biochemistry) and ATJ-switchgrass (lignocellulose-biochemistry).

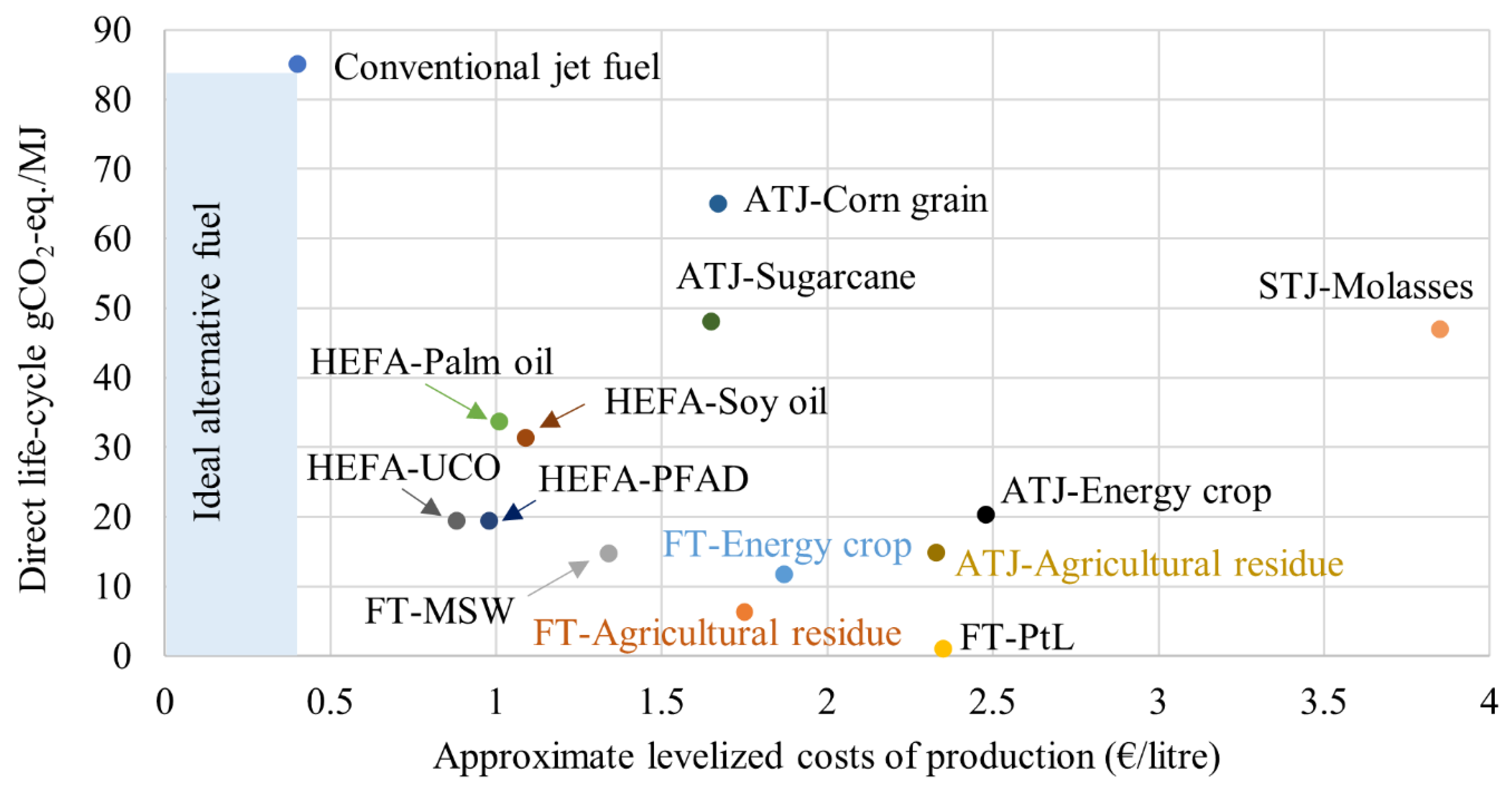

Another study by Pavlenko et al. [

25] examines different alternative jet fuel types produced from different feedstocks. The authors use three different parameters that measure embodied carbon for a given fuel. The first measure is called direct life cycle emissions (i.e., WTWa). This is attributable to upstream phase of fuel manufacturing (feedstock production and fuel conversion), transport, and the use-phase of the fuel. The second measure is indirect land-use change (ILUC) that comprises of indirect GHG emissions considering land-use effects. The ILUC emissions are associated with crop-based feedstocks. The ILUC emissions may also be attributable to by-products, waste, and residues if these are deflected from the present utilisation. Such impacts may be significant, especially if the economic relationships of the feedstocks are closely related with vegetable oils.

The third measure is called carbon intensity, which is a sum of the first and the second measure i.e. sum of direct life cycle (WTWa) emissions and ILUC emissions [

25]. Additionally, the authors carry out a cost comparison of some of the fuel type and feedstock combinations, where they compare the levelized cost of the production process. The levelized cost comprises of capital, feedstock, and operating cost. The comparison of complete life cycle GHG emissions (three measures) and levelized production cost for the fuel type and feedstock combinations is summarised in

Table 3.

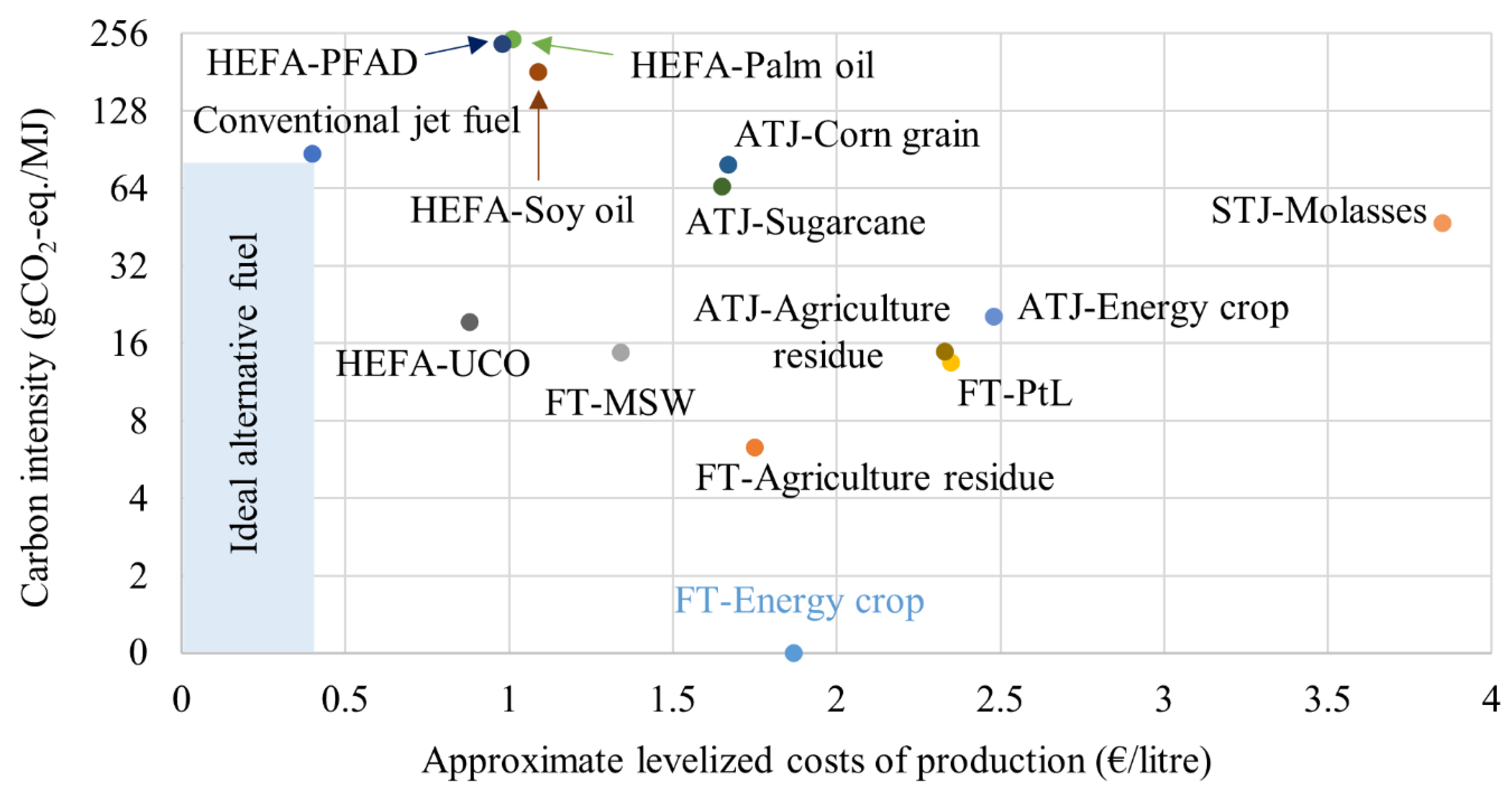

The information in

Table 3 is important, particularly considering the first and third measure. This information is helpful for analysing the ‘sustainability’ aspect of bio-jet fuels with the limited feedstocks evaluated in the study by Pavlenko et al. [

25]. The levelized production cost and the first measure i.e., direct life cycle emissions for feedstock and fuel type is analysed through

Figure 1. Similarly, the levelized production cost and the third measure i.e., carbon intensity for feedstock and fuel type is analysed through

Figure 2.

Figure 2 absorbs the unintended impacts of crop-based feedstocks i.e., ILUC emissions. Typically, ILUC emissions are not calculated in all life cycle studies.

It can be observed from

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 that none of the feedstock and fuel type combination fall in the ‘ideal alternative fuel zone’ (or sustainable alternative fuel zone) i.e., the combination that has lower GHG emission and cost compared to the conventional jet fuel. Referring to

Figure 1, HEFA-UCO and HEFA-PFAD (food crop) are the preferred candidates of fuel type and feedstock combinations followed by HEFA-palm oil (food crop) and HEFA-soy oil (food crop). After considering the land-use impacts of the crop-based feedstocks i.e.,

Figure 2, particularly for food-crops, HEFA-PFAD (food crop), HEFA-palm oil (food crop) and HEFA-soy oil (food crop) are no longer preferred candidates. Referring to

Figure 2, HEFA-UCO and FT-MSW are the top two preferred candidates.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, especially the latter convey the importance of a holistic evaluation. Though ‘direct life cycle emission’ or WTWa is a holistic measure, it does not capture the unintended impacts of certain feedstocks for fuel production, especially feedstocks that compete with food-crops.

A study by Schmidt et al. [

46] demonstrates the development of a relatively novel fuel called ‘power-to-liquid’ (PtL) jet fuel. Electricity produced from renewable sources like solar and wind energy is used in the electrolysis of water for hydrogen production. After carbon (CO

2) capture, hydrogen and CO

2 undergo chemical process to form hydrocarbon fuel (PtL). This study provides information on different pathways of producing PtL fuel, and it estimates the life cycle GHG from the production pathways. PtL has significantly lower/near-zero life cycle GHG emission and about 55% lower water consumption compared to conventional jet fuel. It is not currently approved for civil aviation. The life cycle GHGs of PtL from two paths [

46,

47]; are as follows:

- i.

PtL (wind/photovoltaics [PV] in Germany, renewable world embedding) = ~1 g/MJ

- ii.

PtL (wind/PV in Germany, today’s energy landscape in material sourcing and construction) = 11 to 28 g/MJ

One of the processes involved in fuel refining is the FT process. It is to be noted that 50% blended FT jet fuel is approved by ASTM, and 50% blend of PtL from FT process can be used directly. It has higher fuel productivity per hectare land compared to all bio-jet fuels. Its thermo-physical and fuel handling properties are like conventional jet fuel, which means that PtL can be potentially used as a ‘drop-in’ fuel. This enables status-quo in aircraft powerplants. Presently, it costs 7.3 – 10 times more than conventional jet fuel. Similar information is revealed in the report by the German Environmental agency [

47], where details of PtL fuel production, life cycle GHG, and its current and 2050 production costs are provided. In 2050, the cost of PtL is predicted to be 1.4 – 4.5 times the cost of conventional jet fuel [

46,

47].

Table 3 and

Figure 2 provide the ILUC emissions of PtL. The ILUC emissions are attributable to the infrastructure required for new renewable electricity generation. The direct life cycle GHG emissions for PtL in future renewable energy landscape is 1 g/MJ and after considering the ILUC emission of 12.5 g/MJ results in a carbon intensity of 13.5 g/MJ for PtL. Referring to

Table 3, the levelized cost of production of FT-PtL (using future energy landscape) is 5.9 times the present cost of the conventional jet fuel.

A study by De Jong et al. [

26] carries out WTWa CO

2 equivalent emission performance of several renewable jet fuel pathways and analyses the effect of different co-product allocation process. The WTWa CO

2 equivalent values for different renewable jet pathways are summarised in

Table 4. The authors find that FT pathway enables the highest reduction of GHG emission (86 – 104%) compared to conventional jet fuel. The authors highlight that renewable jet fuel could significantly reduce aviation related GHG emissions if correct pathways and/or feedstock are used. Additionally, the authors note that the GHG emission performance of renewable jet fuel could be further improved by employing carbon capture and storage, and using sustainable hydrogen sources, in the fuel production.

In 2021, the international civil aviation organization (ICAO) published/updated the default life cycle emissions values for carbon offsetting and reduction scheme for international aviation (CORSIA) eligible fuels [

28], based on study [

27]. For these CORSIA values, three different parameters are used that measure embodied carbon for a given fuel. The first measure is called direct or core life cycle emissions which is attributable to upstream phase of fuel manufacturing (feedstock production and fuel conversion), transport, and the use-phase of the fuel. The second measure is ILUC that comprises of indirect GHG emissions considering land-use effects. The ILUC emissions are associated with crop-based feedstocks which maybe attributable to by-products, waste, and residues if these are deflected from the present utilisation. Such effects may be important, especially if the economic relationships of the feedstocks are closely related with vegetable oils. The third measure is called carbon intensity or net emissions, which is a sum of the first and the second measure i.e., sum of direct life cycle emissions and ILUC emissions. These default values are calculated based on the core life cycle emissions and ILUC emissions, for selected feedstocks and pathways in different country, region and/or globally, and are summarised in

Table 5. The lowest net emissions (WTWa) are observed for FT fuel (-22.5 g/MJ CO

2 equivalent) produced from miscanthus in the USA.

A review study by Kolosz et al. [

23] compares the WTWa performance metrics of different studies on ‘drop in’ fuels which include biofuels (first, second, and third generation) and different fossil fuel based jet fuel (from coal, oil sands, oil shale, natural gas, etc.). The review study highlights the uncertainty during fuel production and combustion at high altitudes. The study points out next generation fuels such as oleaginous yeasts, alcohols, and low-carbon fuels – liquid hydrogen (LH

2), liquid natural gas (LNG), and liquid ammonia (LNH

3), and the need to examine these fuels on WTWa basis, in future studies.

A report by Van Der Sman et al. [

29] reviews cost of sustainable aviation fuels (biofuels and PtL) and their carbon reduction potential in EU, in addition to reviewing literature on other industry strategies for decarbonising aviation. The authors report that PtL has higher embodied carbon reduction potential as compared to biofuels but has significantly higher cost. For example, jet fuel produced from used cooking oil (HEFA) and hydrothermal liquefaction (separately) will cost 1.9 – 2.7 times higher and PtL will cost 2.2 – 6.4 times higher, compared to Jet-A.

The study by Koroneos et al. [

56] (based on the Cryoplane project) conducted a comparative WTWa performance examination of a small aircraft from the A320 family (3,360 km range, 124 passengers) powered by LH

2 and Jet-A (separately) considering effects such as greenhouse, acidification, eutrophication, and winter smog. This analysis is conducted using GEMIS (global emission model for integrated systems) database. The authors examine a smaller aircraft, though it is relevant to this work (large twin aisle aircraft) in terms of high-level objectives, is less recent (early 2000s) and considers fewer ways of producing LH

2. Also, the authors do not consider the effect of contrails cirrus in their WTWa analysis. The authors consider energy source like solar photovoltaics, solar thermal, wind, biomass, hydropower, and natural gas, for hydrogen production. The authors emphasise the significance of producing LH

2 from renewable energy sources such as wind energy and hydropower, especially considering their negligible environmental impacts. However, the authors also point the need to produce LH

2 from these sources cost-effectively while ensuring the fuel demands are met.

A study by Pereira et al. [

57] compares LH

2, LNG, and Jet-A on a WTWa basis, where LH

2 is produced from four separate pathways – steam methane reformation, solar PV, wind energy, and hydropower. This comparison is carried out for both small (A320 type) and large aircraft (A340 type). The authors use a combination of existing models (GREET and GEMIS) for the well-to-pump (WTP) phase or fuel manufacturing phase emissions modelling and existing EMEP/EEA dataset for the pump-to-wake (PTWa) phase or use-phase. The methodology does not consider the poor volumetric energy density characteristics of LH

2 which penalises aircraft energy performance. The aircraft use-phase energy consumption and/or emissions have a significant impact on the WTWa performance. Also, the authors do not consider the effect of contrails cirrus in their WTWa analysis. The authors observe that renewable hydrogen is the less polluting option, particularly from hydropower or wind energy. Additionally, manufacturing LH

2 from renewable energy sources has benefits both in terms of WTWa energy consumption, and environmental and social impacts. The authors point out the need to examine renewable LH

2 production cost, since the market penetration of this fuel depends on its cost effectiveness.

Bicer et al. [

58] conducts a WTWa evaluation of a small twin aisle aircraft of conventional tube-wing architecture (such as the Boeing 767) with a flight range of 5,600 km, where the aircraft is operated by Jet-A, LH

2, LNG, LNH

3, ethanol, and methanol (separately). It is to be noted that the authors use SimaPro software (with Ecoinvent database), which is a life cycle assessment software, for their analysis. The methodology does not consider the poor volumetric energy density characteristics of LH

2 which penalises aircraft energy performance that has a significant impact on the WTWa performance. Also, the authors do not consider the effect of contrails cirrus in their WTWa analysis. The fuels are examined considering aspects such as land use, global warming potential (GWP), ozone layer depletion, abiotic depletion, and human toxicity. For both LH

2 and LNH

3, the authors evaluate renewable energy sources for fuel manufacturing that include hydropower, geothermal, solar, and wind energy, and for LH

2 the production pathway of underground coal gasification with carbon capture storage is also examined. The authors find that LH

2 when manufactured from geothermal energy could be preferred route than LNH

3 (from geothermal), other alternatives, and Jet-A on WTWa basis in terms of GWP.

Similarly, a study by Ratner et al. [

59] provides the WTWa performance of a small aircraft (1,667 km range, 190 passengers) powered by battery and fuel cell (separately), where the electricity and LH

2 are produced from different sources. The authors use Ecoinvent life cycle assessment (LCA) dataset for their analysis, and it is unclear (not explicit) whether the (negative) volumetric effects of LH

2 are considered in the aircraft energy modelling. The methodology is either not clear from the information supplied or do not consider the poor volumetric energy density characteristic of LH

2 which penalises aircraft energy performance. The aircraft use-phase energy consumption and/or emissions have a significant impact on the WTWa performance. Also, the authors do not consider the effect of contrails cirrus in their WTWa analysis. The authors provide comparison of 13 different alternative cases with metrics such as oxidation and eutrophication potential, climate impact, ecotoxicity, and land use, along with their cost. The authors find that electric aircraft powered by electricity produced from wind energy could reduce the aircraft’s climate impact, compared to Jet-A, while being the most cost-effective solution of all alternatives and of similar magnitude as that of Jet-A. The analysis is simplistic in nature and is limited to fewer pathways/sources of producing electricity and LH

2, for a small aircraft with short range.

A study by Siddiqui et al. [

60] conducts comparative WTWa performance examination of a passenger aircraft (range and passengers not known) powered by LH

2, LNH

3, ethanol, methanol, dimethyl ether, biodiesel, and Jet-A (separately). The fuels are examined considering aspects such as greenhouse effect, ionising radiation potential, terrestrial acidification, freshwater eutrophication, photochemical ozone formation, particulate matter, freshwater ecotoxicity, human carcinogenic toxicity, and land use occupation. For LH

2 and LNH

3, the authors examine renewable energy sources for fuel production such as hydropower, geothermal, solar, and wind energy. This analysis is conducted using SimaPro software using Ecoinvent database. The methodology is either not clear from the information supplied or do not consider the poor volumetric energy density characteristic of LH

2 which penalises aircraft energy performance. The aircraft use-phase energy consumption and/or emissions have a significant impact on the WTWa performance. Also, the authors do not consider the effect of contrails cirrus in their WTWa analysis. The authors find that LH

2 when produced from geothermal energy, performs better than LNH

3 (from geothermal), other alternatives, and Jet-A, on WTWa basis in terms of greenhouse effect. The authors point out the need of manufacturing LH

2 from renewable energy sources cost-effectively while simultaneously ensuring that the required fuel demand is met.

In a study by Miller [

30], a slightly more detailed WTWa analysis of alternative aviation fuels (LH

2 and biofuels) is conducted, compared to above studies. The metrics used for this comparative WTWa analysis are climate impacts and air quality, water consumption in fuel manufacturing stage, and in non-use phase it estimates acidification, eutrophication, respiratory effects, and smog. This study encompasses aircraft and airport emissions (construction and use-phase) and considers a simplistic estimation of effect of contrails toward climate impacts. The methodology of the said study for the WTWa emissions analysis is eclectic as the authors use published models for different segments of the life cycle. For example, the author uses GREET model for the fuel manufacturing phase emissions. The author uses all available LH

2 production pathways in GREET, and for biofuel only FT, HEFA, and ATJ are used. The study by Miller, though is slightly more detailed compared to the above studies as it consider tens of several feedstocks and/or pathways for LH

2 and biofuels along with the effect of contrails cirrus in WTWa analysis, it misses out on PtL or electro-fuels and STJ fuel, and the WTWa results are limited only to short or medium range aircraft. The author provides analysis in the use-phase for different aircraft size at 930 km range (500 nmi) and further examines a Boeing 787-800 type for a 6,500 km range (3,500 nmi), for its WTWa performance. The author observes that the WTWa performance of combustion based LH

2 aircraft is strongly dependent on the fuel production pathway. LH

2 produced from renewable energy sources (wind, hydroelectric, and geothermal) are strong contenders but scalability is a concern. Additionally, the author points out the need for further evaluation of contrail cirrus effect of LH

2 aircraft to refine the WTWa estimates and help decision making towards LH

2 powered aviation investments.

A study by Mukhopadhaya et al. [

61] evaluates the performance of regional and small range LH

2 aircraft along with cost analysis and embodied carbon. The authors model the LH

2 aircraft while considering its poor volumetric energy density characteristic along with the effect of cryogenic tank gravimetric index, which penalises the energy performance. The authors compare the embodied carbon and cost per revenue passenger km of LH

2 (blue and green) and e-kerosene (PtL) with Jet-A for 2035 and 2050 timeframe in EU and USA. However, the authors consider fewer ways of LH

2 production and do not consider the effect of contrails cirrus in their WTWa analysis for the fuels considered. The authors find that the cost of powering aircraft with green hydrogen is expected to be more than Jet-A but lesser than e-kerosene or blue hydrogen. Also, if carbon pricing is included then green LH

2 could be cost competitive with Jet-A or cost lesser. Additionally, to maximise the climate impact reduction potential for LH

2 aircraft and enable successful penetration of green hydrogen (low embodied carbon) in aviation, there is a need to account the life cycle effects appropriately along with policies. Moreover, for LH

2 aircraft to be successful, the above efforts need to be complemented with supportive government policies such as low-carbon fuel standards, alternative fuel mandates to bridge the cost gap with Jet-A, carbon pricing, and/or bolstering fuel efficiency policies, to enable required investments for fostering R&D, design, testing, and establishing infrastructure for LH

2 production, distribution, and storage.

The FlyZero report [

31] studies different fuels and propulsion type (with technology improvement in 2040 timeframe) and compares them on WTWa basis, for regional short-range to midsize medium range aircraft. In terms of fuels and propulsion type, the study examines LH

2 (fuel cell and combustion based, considering performance penalty due to installation of cryogenic tank), PtL, and biofuel. The study reports the climate impact due to contrail cirrus along with the climate impacts due to oxides of nitrogen (NO

x), H

2O, and CO

2 in the use-phase, and emissions in the fuel manufacturing phase. The study uses a combination of models for the life cycle assessment which includes use of SimaPro software (hydrogen) and CORSIA values (for biofuels). The FlyZero report accounts the performance penalty due to cryogenic tank installation and the impact of contrail cirrus in their WTWa analysis of LH

2, PtL, and biofuel for small to mid-size aircraft. However, their analysis is limited to a few selected feedstocks and/or pathways of manufacturing LH

2, PtL, and biofuel. LH

2 is assumed to be produced only from renewable electricity and biofuels manufactured using a mix of feedstocks from CORSIA eligible fuels (limited feedstocks only). Overall, the study finds that both combustion-based and fuel-cell powered LH

2 aircraft are preferred candidates as their WTWa CO

2 equivalent emissions are lesser than other alternatives and Jet-A fuel, except for very-short range where electric aircraft would be preferred vehicles.