Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Classical Electron Radius

1.2. Reduced Compton Radius

1.3. Nuclear Electron Radius

1.4. Electron Radius from Einstein’s Dual Theory

1.5. Lorentz-like Gas and Collision Times

1.5.1. Lorentz-like Gas

1.5.2. Collision Times

2. Times in an Electron Plasma (Lorentz-like Gas)

2.1. Characteristic Times

- The duration time of an electron collision is the time in which the interaction between two electrons lasts;

- The collision time or the free path time is the time that passes between each collision ( for the TOKAMAK);

- The relaxation time is the time in which the particles slow down due to Stokes’ law.

2.2. Hierarchy of the Different Times

2.3. Duration Time

2.3.1. Stochastic Force, Stokes’ Model

2.4. Collision Time or Free Path Time

2.4.1. Example

2.4.1.1. H2 at its Critical Point

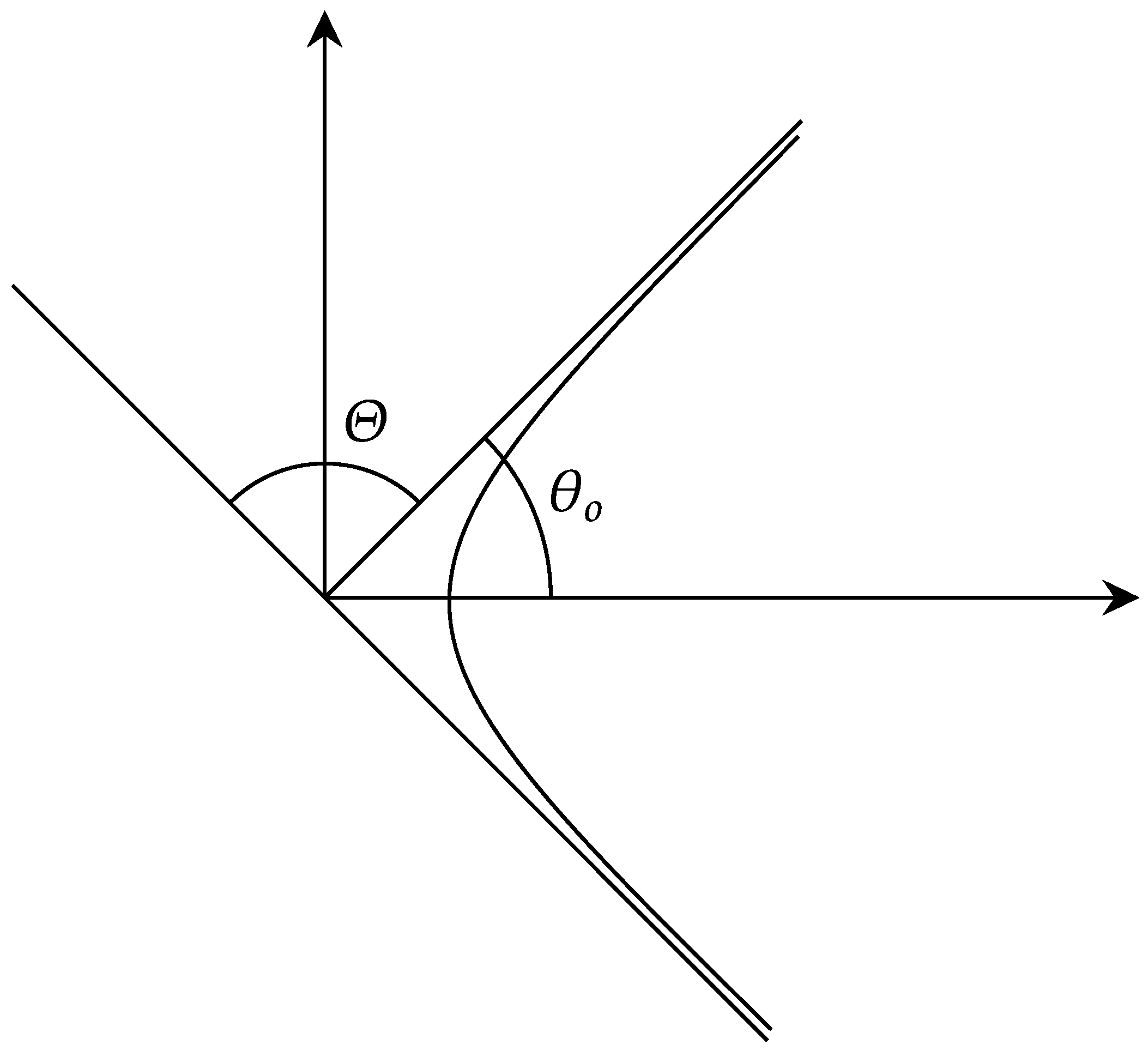

2.5. Rutherford Scattering

2.5.1. The Binary-like Collision Time.

2.6. Collision Time for Multiple Collisions

2.7. Relaxation Time

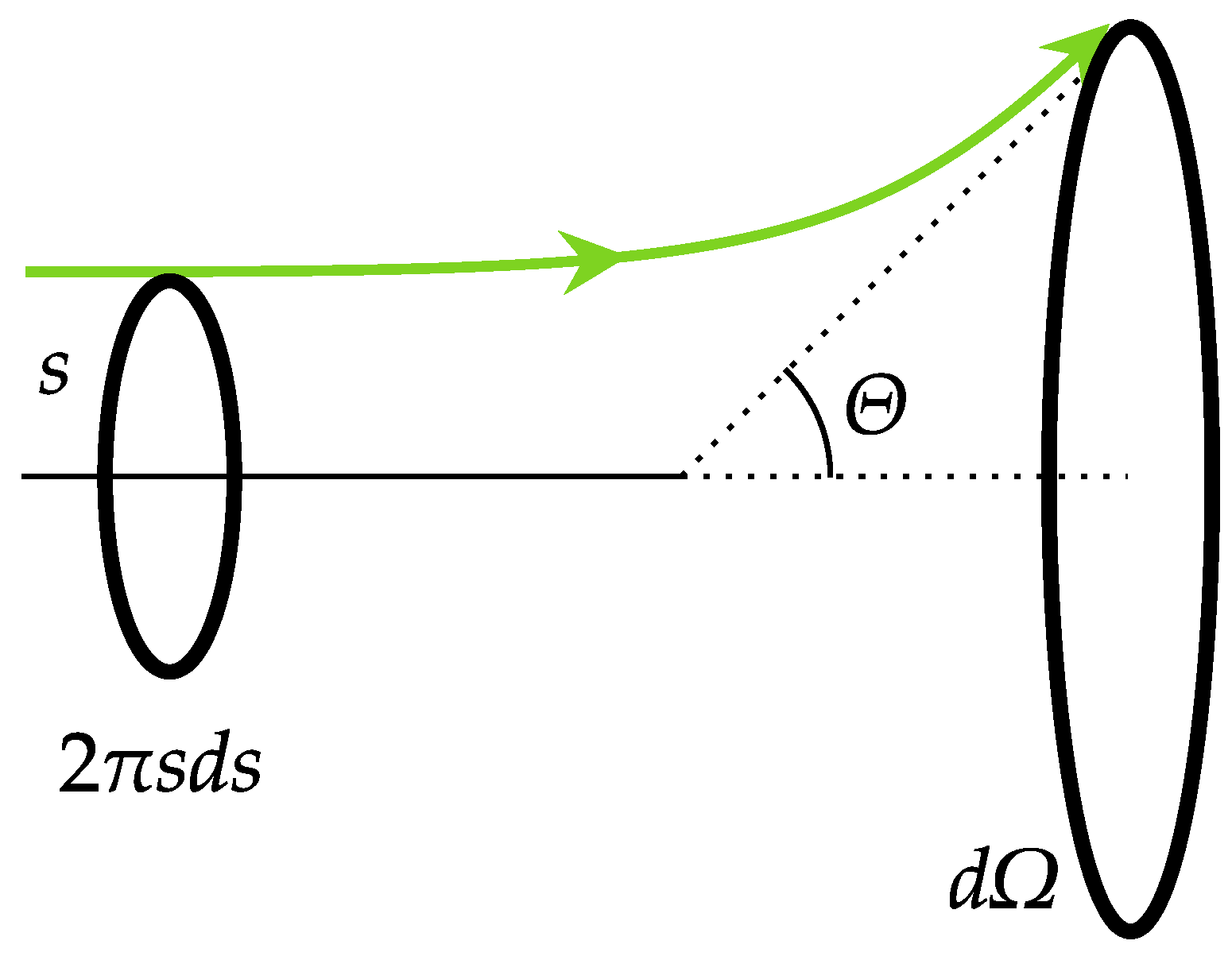

2.7.1. Cross Section for Momentum Transfer

3. Effective Radius of the Electron in a Plasma

4. Dynamic Viscosity

5. Discussion

- We managed to define a Lorentz-like gas as a gas of electrons that do not interact with other particles such as ions, and the interaction with electrons is modeled through collisions of hard-sphere electrons. This was made possible by analyzing the different timescales;

- We were able to compare the different times between electrons, namely: the duration time of a Coulombic collision, the Coulombic collision time due to multiple collisions and the relaxation time. We give the relationships between them described by Eqs. (19, 36, 33, 64, 66, 69) and (70). In particular, we highlight that for a Lorentz-like gas we obtain which allows a noise force with the correlation described by Eq. (32) called white noise, and ;

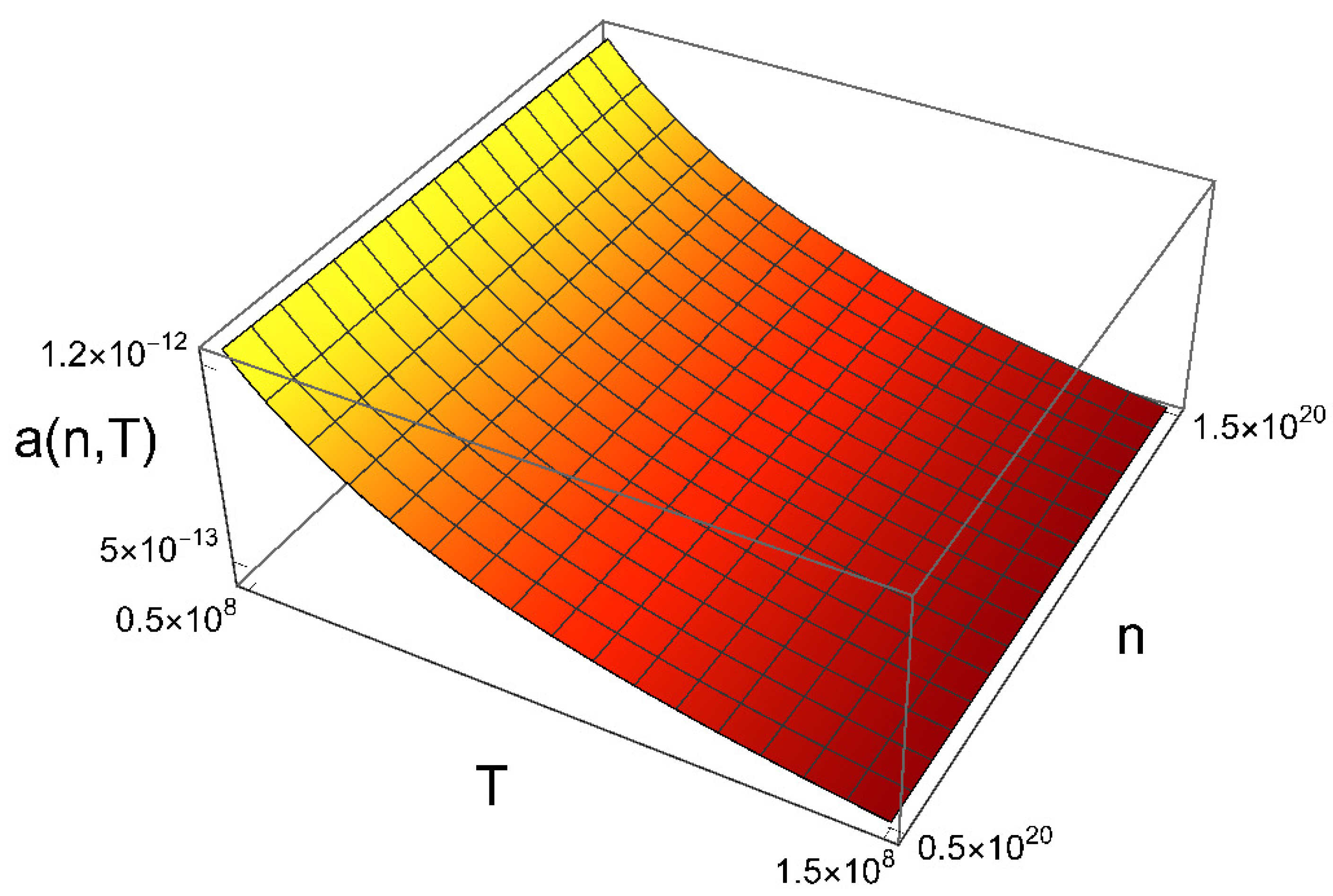

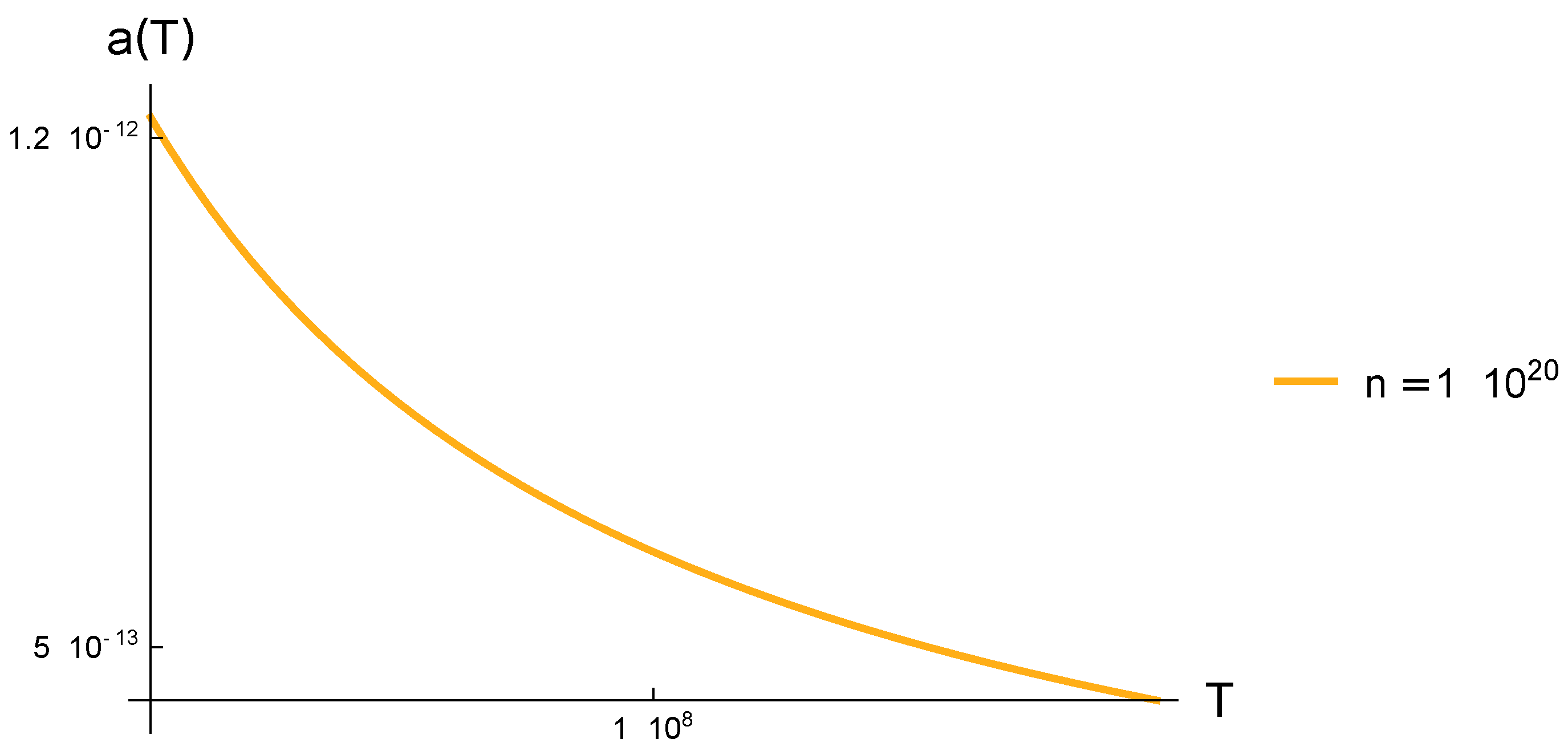

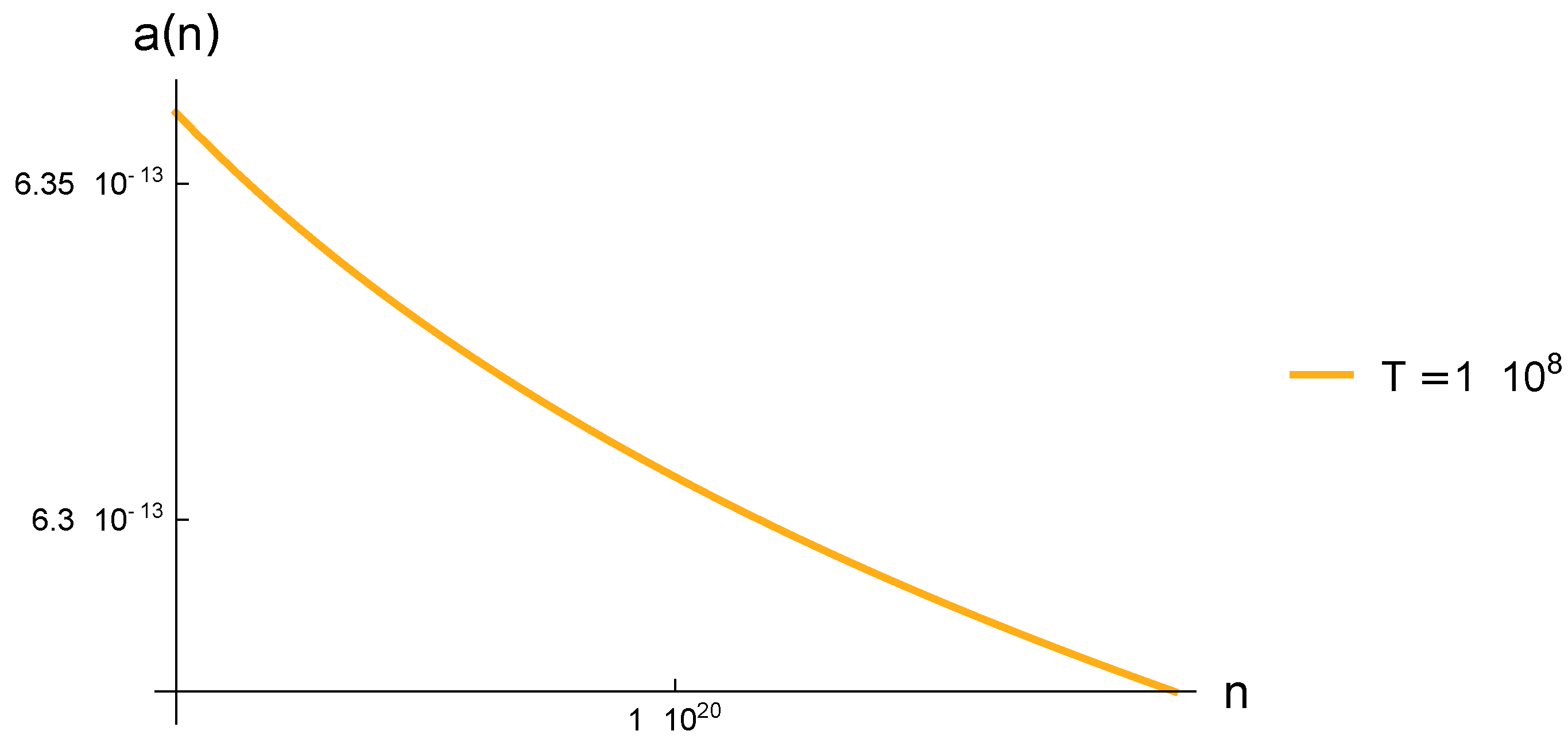

- We have been able to calculate the equivalent or efficient radius of the electron in what we call the Lorentz-like gas. Interestingly, unlike other proposals for obtaining the electron radius, whose data are obtained from fixed parameters such as the electron charge, Planck’s constant, fine-structure constant, and mass, the effective or equivalent electron radius is obtained as a function of not only the above parameters but also of temperature and density. This radius is consistent with the density, since it is much smaller than the occupation length for each charge, Eq. (13). It is much larger than the classical radius of the electron that avoids radiation and timescale problems, in Eq. (4), and although it decays according to Eq. (76) and Figures (Figure 3), (Figure 4) and (Figure 5), it should be noted that these results have limits represented by the relativistic effects Eq. (20), and the plasma parameter, Eqs. (11) and (12);

- By assigning a value to the electron radius, we can describe the Lorentz-like gas as a gas composed of rigid spheres that satisfies the Braginskii equations [18,25]. All properties of a plasma composed of rigid particles can be calculated using the Chapman-Enskog method [37]. The dynamic viscosity was calculated in this way, but more properties could be calculated.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dirac, P.A.M.; Classical theory of radiating electrons. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 1938 167, 148. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. D; Classical Electrodynamics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, third Ed. 1999 Chaps. 14 and 16.

- Shpolsky, E.; Atomic physics, Atomnaia fizika; Gostekhizdat: Moscow, 2nd Ed. 1951.

- Gabrielse, G; Electron Substructure Physics; Boston, Harvard University Archived from the original on 2019/04/10 Retrieved 2016/06/21.

- Dehmelt, H; A Single Atomic Particle Forever Floating at Rest in Free Space: New Value for Electron Radius, Physica Scripta 1988T22102--110. [CrossRef]

- Urdaneta Santos, I; The zitterbewegung electron puzzle. PHYSICS ESSAYS 2023, 36-6, 299--335. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, A. and Sipilä, H.; The theory and experimental validation of nuclear electrons’ Heisenberg uncertainty, J.Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2025 2987, 012010. [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, G. and Kovacs, A.; The Proton and Occam’s Razor. Journal of Physics: Conferences Series 2023, 2482, 012020-012045. [CrossRef]

- Gill, T. L., Ares de Parga, G., Morris, T. and Wade, M.; Dual Relativistic Quantum Mechanics I. Foundations of Physics 202252:90. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.; Prinzipien der Dynamik des Elektrons. Annalen der Physik 1903 10, 105-179. [CrossRef]

- Lorentz, H.A.; Theory of Electrons and Its Applications to the Phenomenon of Light and Radiation Heat Dover: New York,second edition 1952.

- Rohrlich, F; Classical Charged particles Addison-Wesley: Read, Mass., 1965.

- Gamba, A; Physical Quantities in Different Reference Systems According to Relativity, Am. J. Phys. 1967 35, 83-89. [CrossRef]

- Lorentz, H. A.; The motion of electrons in metallic bodies. KNAW, proceedings: Amsterdam 1905, 7, 438-453.

- Rousseau, E. and Felbacq, D.; Ray chaos in a photonic crystal. Europhysics Letters 2017, 117, 14002-14008.

- Kraemer, A. S. and Sanders D. P.; Embedding Quasicrystals in a Periodic Cell: Dynamics in Quasiperiodic Structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 2013, 111, 125501-125506. [CrossRef]

- Balescu, R; Transport Processes in Plasmas, 1. Classical transport theory. North-Holland: Oxford, 1988 pp137 Eq. (2:4) to Eq. (2:8).

- Fitzpatrick, R. ; Plasma Physics: An Introduction. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton 2015.

- Hinton, F. L. and Hazeltine, R. D.; Theory of plasma transport in toroidal confinement systems. Reviews of Modern Physics 1976 Vol. 48, 239. [CrossRef]

- Krall, N. A. and Trivelpiece, A. W.; Principles of Plasma Physics, McGraw-Hill: New York, 1973 Section 2.3 pp 61 and Section 11.

- R. Balescu, Irreversible Processes in Ionized Gases. Phys. Fluids, 1960 3, 52. [CrossRef]

- A. Lenard, On Bogoliubov’s kinetic equation for a spatially homogeneous plasma. Ann. Phys. (NY) 1960 3, 390. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Statistical Mechanics, John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1963 Chap 5 Eq. (5.6).

- Schiff, L. I.; Quantum Mechanics McGraw-Hill: Auckland, 1968 pp 124-126, Chap 5 Eq. (19.24).

- Braginskii, S. I.; Transport Processes in a Plasma. Review of Plasma Physics Volume 1 pp 205-311.

- Spitzer, L. Jr.; Diffuse Matter in Space. Wiley: New York, 1968 pp 92.

- Ichamuru, S. ; Basic Principles of Plasma Physics: A Statistical Approach W. A. Benjamin, INC: Reading, Mass. 1973.

- Cairns, R. A. ; Plasma Physics. Blackie & Son Limited: Glasgow 1985.

- Jakoby, B.; The relation between relaxation time, mean free path, collision time and drift velocity-pitfalls and a proposal for an approach illustrating the essentials. European Journal of Physics 2009 Volume 30, 1. [CrossRef]

- Zwanzig, R.; Noneequilibrium Statistical Mechanics Oxford University Press: New York 2001 pp 95.

- García-Colín, L. S. and Dagdug, L.; The Kinetic Theory of Inert Dilute Plasmas. Springer Series on Atomic, Optical and Plasma Physics: Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2009.

- chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://arunkumard.yolasite.com/resources/LP2-Postulates.

- Elber, R., Makarov, D. E. and Orland, H.; Molecular Kinetics in Condensed Phases: Theory, Simulation, and Analysis John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Hoboken 2020 pp 3 Eq. (1.12).

- Risken, H.; The Fokker -Planck Equation Methods of Solution and Applications. Springer-Verlag: Berlin 1984 pp 3.

- See table at https://en.wikipedia.

- Goldstein, H.; Classical Mechanics Addison.Wesley: Reading, Mass. 2nd Ed. 1980.

- Chapman, S. and Cowling, T. G.; The Mathematical Theory of Non-Uniform Gases. Cambridge: New York 1953.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).