Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

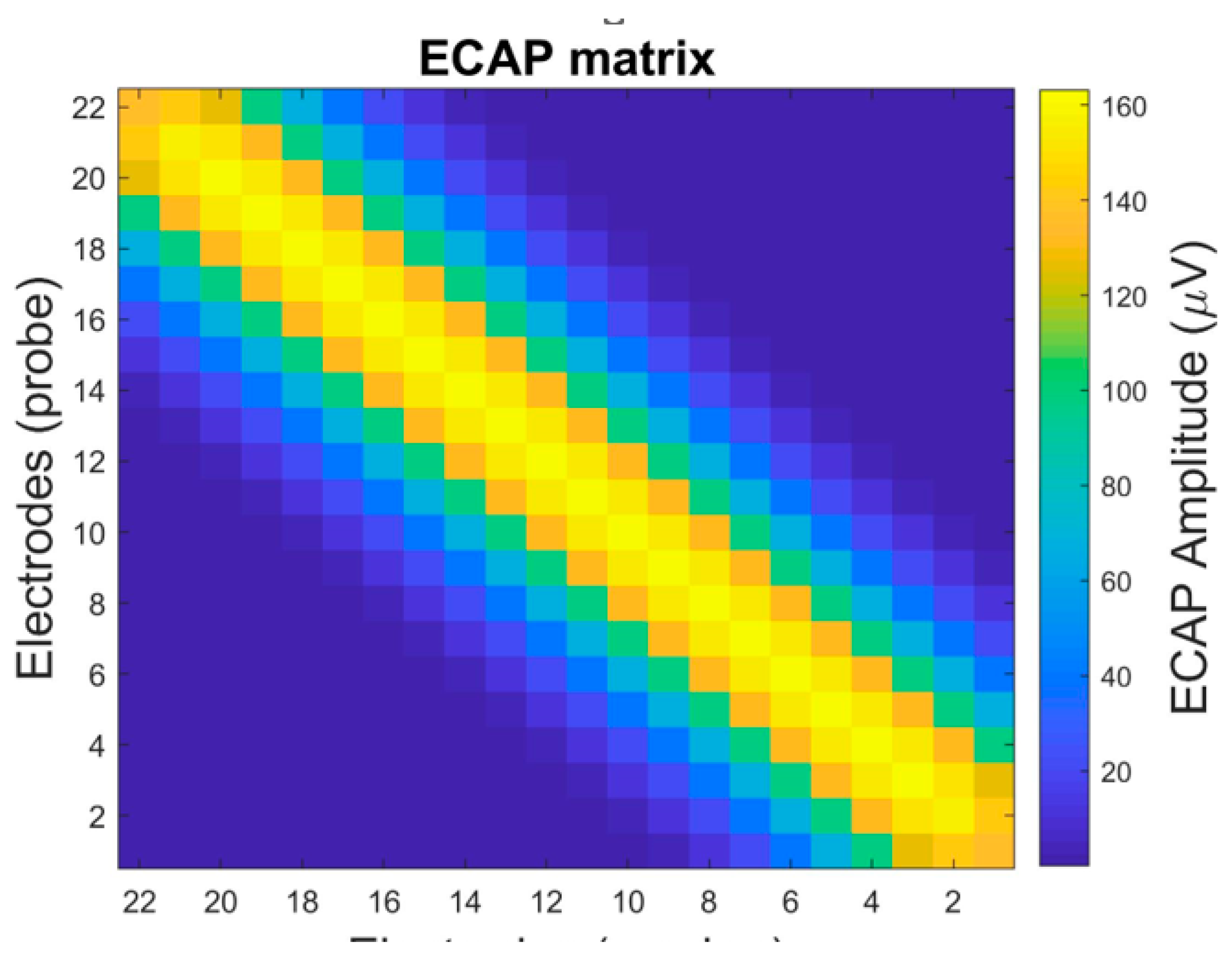

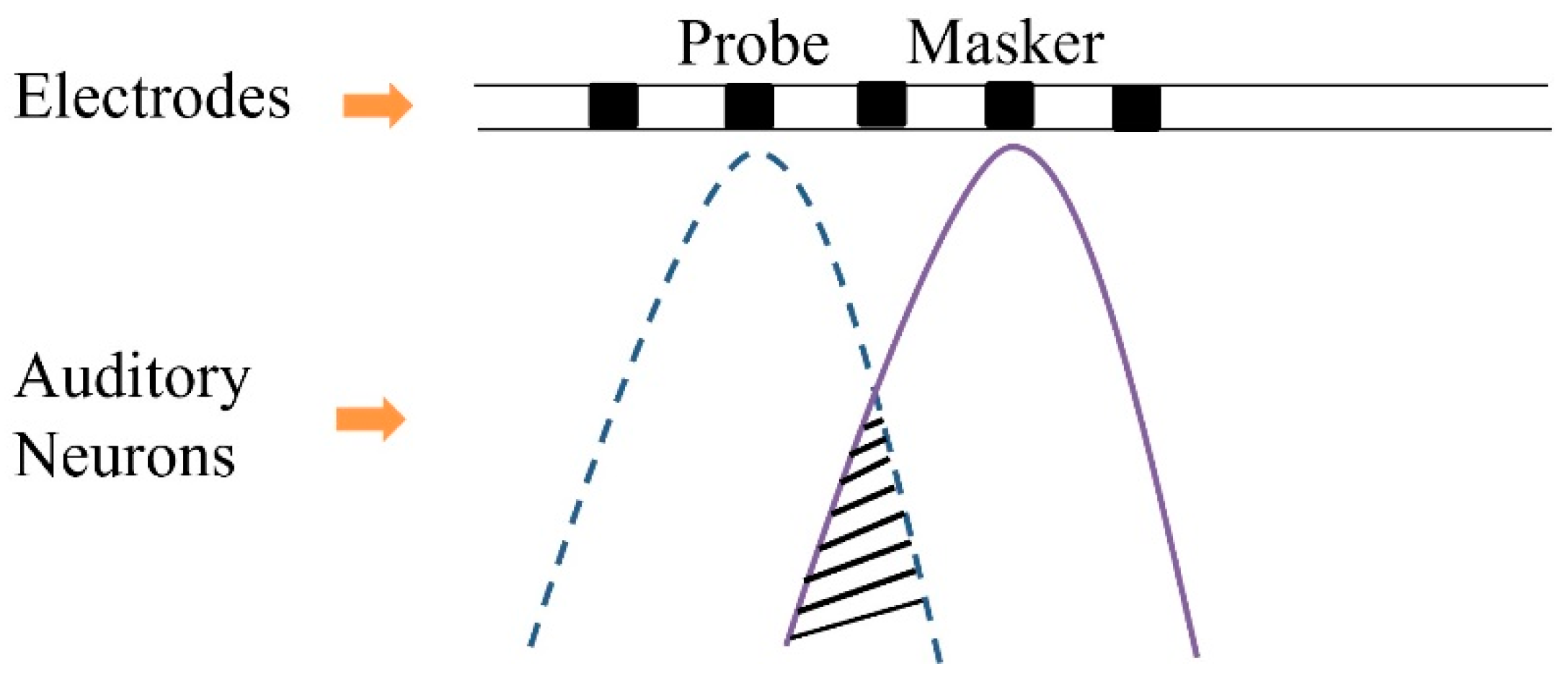

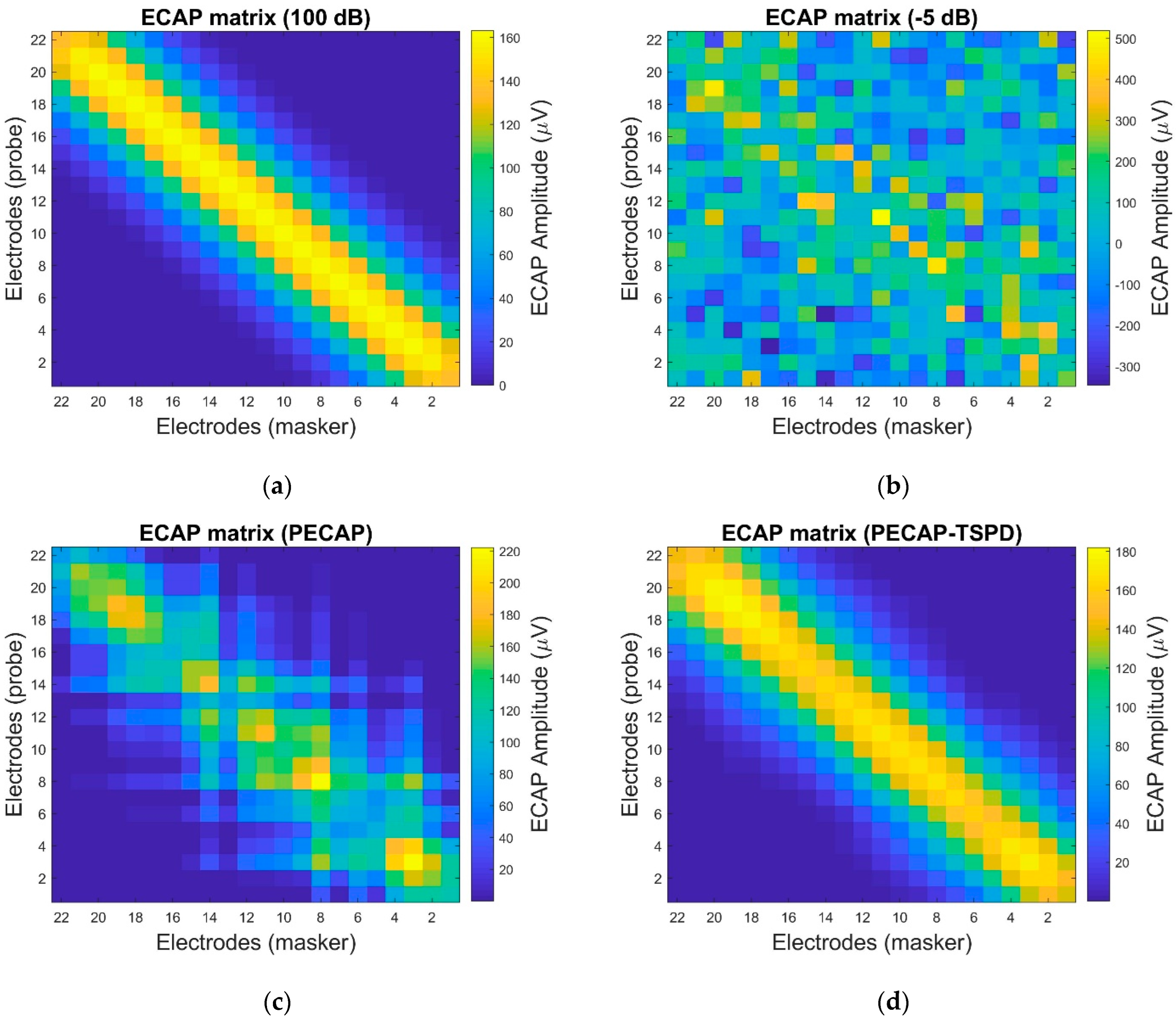

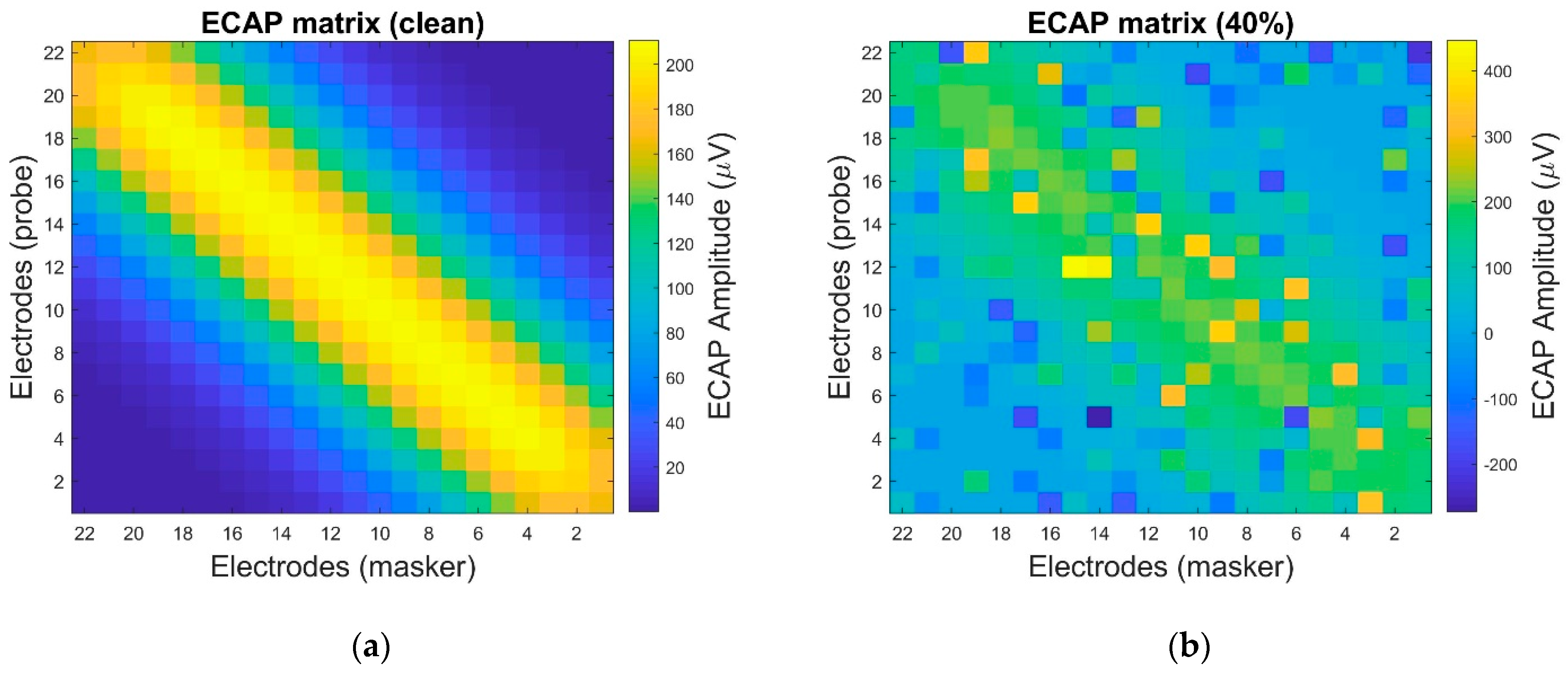

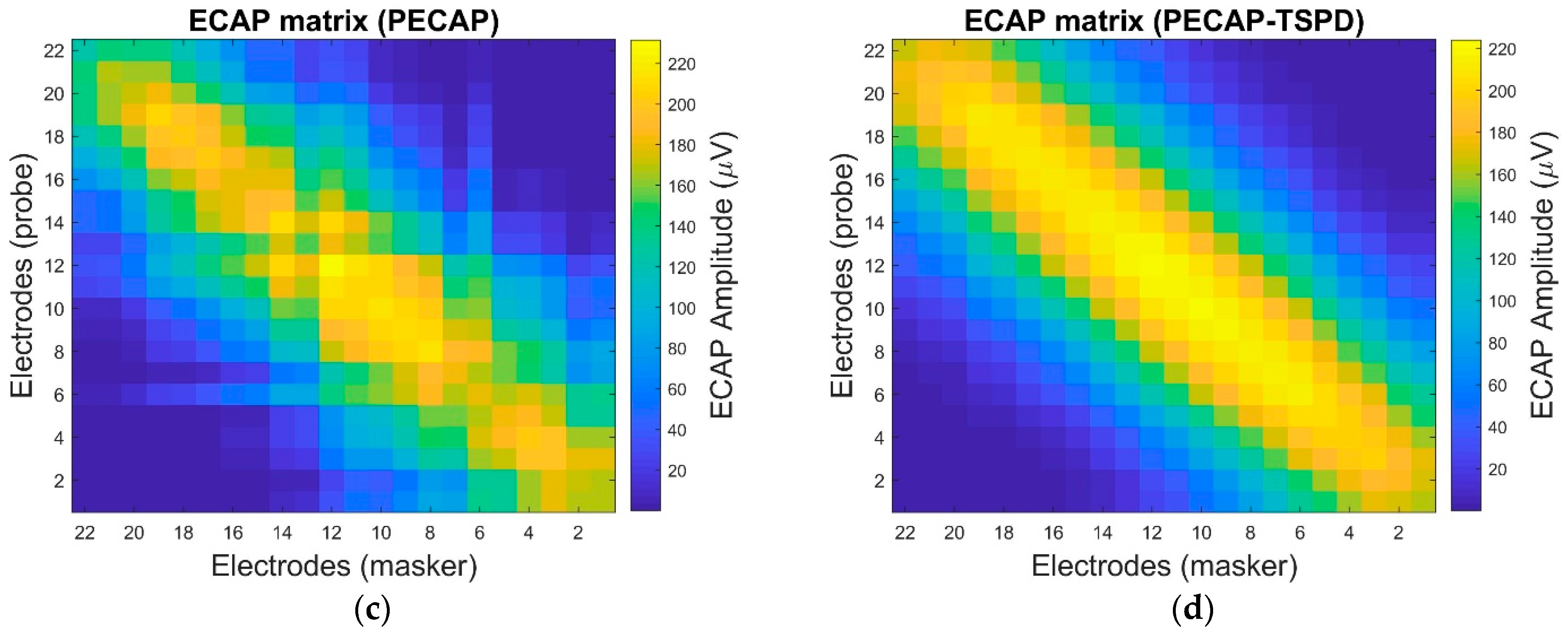

2. Panoramic ECAP Method

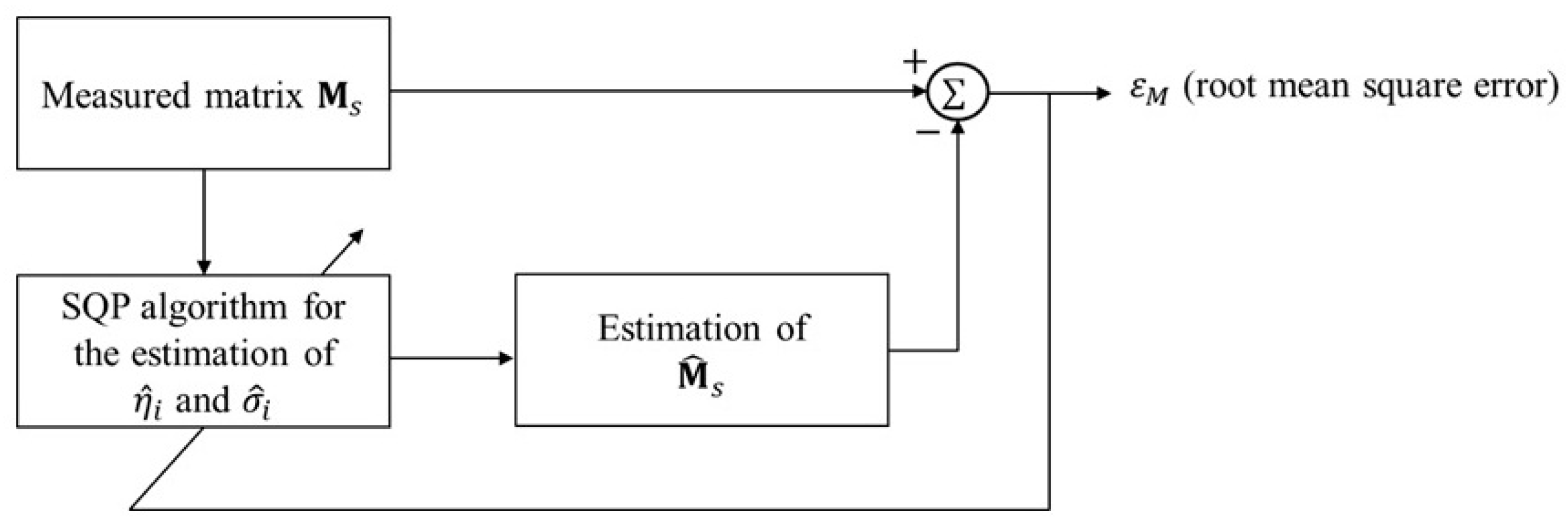

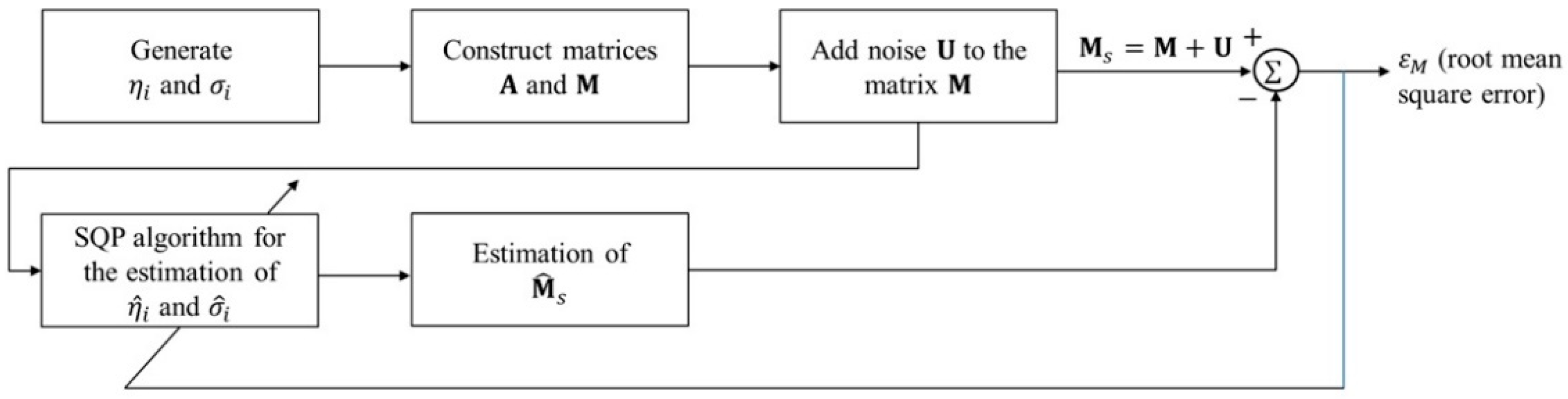

3. Proposed Method

3.1. First Stage Noise Reduction Processing

- 1.

- Calculate the absolute value of index minus indexwhere is an index matrix that records the absolute value of position difference between and

- 2.

- record for each element in and concatenate each row into a long vector.where

- 3.

- Conduct a descending order of and record the descending order index.where represents the descending order operation. is vector based on the descending order results of . is the index vector corresponding to .

- 4.

- The desired vector then can be obtained using the following equation:

3.2. Second Stage Noise Reduction Processing

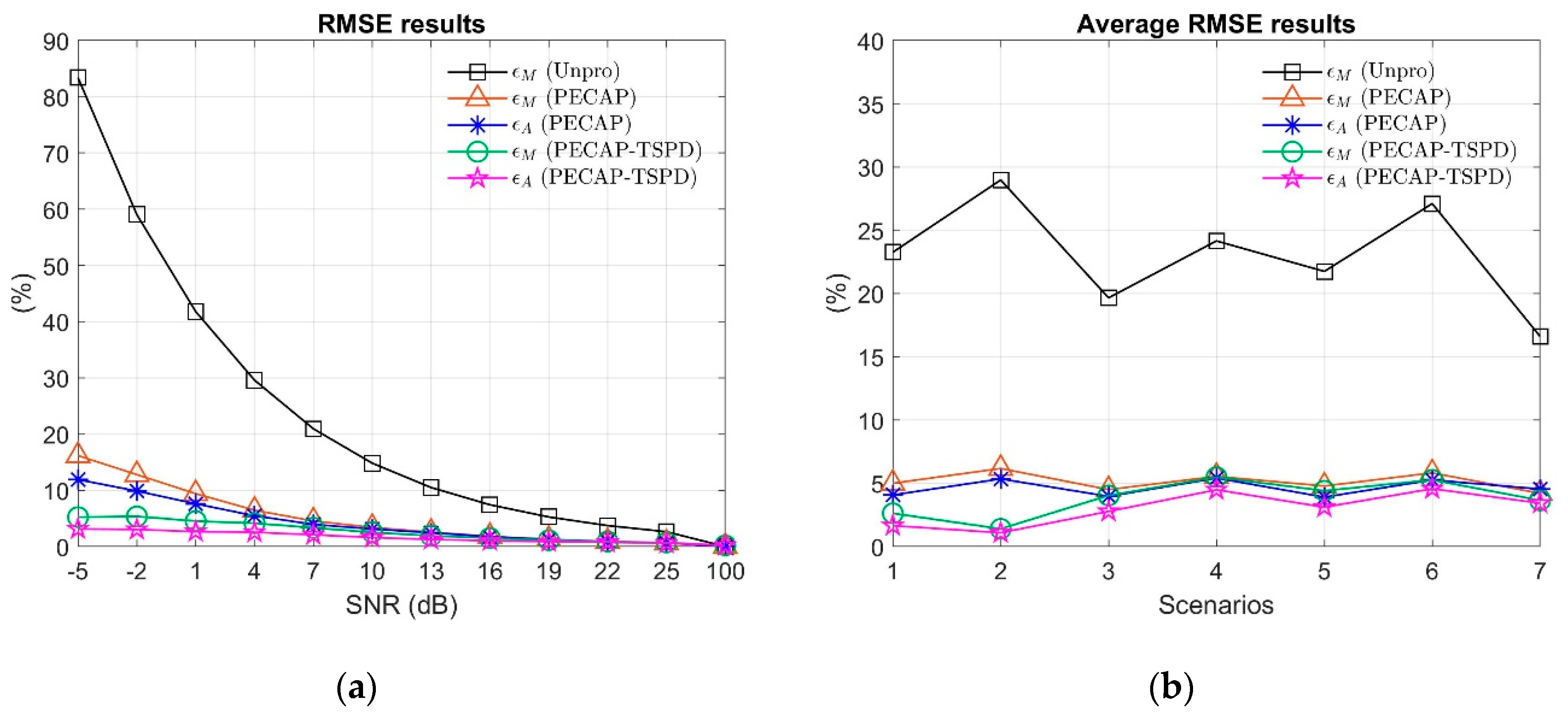

4. Settings and Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECAP | Electrically evoked compound action potential |

| PECAP | Panoramic ECAP |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| TSPD | Two-stage preprocessing denoising algorithm |

| LSA | Log-spectral amplitude |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| Unpro | Unprocessed data |

References

- Liebscher, T.; Hornung, J.; Hoppe, U. Electrically evoked compound action potentials in cochlear implant users with preoperative residual hearing. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1125747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Teagle, H.F.B.; Buchman, C.A. The Electrically Evoked Compound Action Potential: From Laboratory to Clinic. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 339–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M. L. Fundamentals of Clinical ECAP Measures in Cochlear Implants: Part 1: Use of the ECAP in Speech Processor Programming (2nd Ed.) (accessed on 13 February, 2025).

- DeVries, L.; Scheperle, R.; Bierer, J.A. Assessing the Electrode-Neuron Interface with the Electrically Evoked Compound Action Potential, Electrode Position, and Behavioral Thresholds. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2016, 17, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.T.M.; Wu, D.L. Electrically Evoked Compound Action Potential Studies Based on Finite Element and Neuron Models. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2022, 58, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Goehring, T.; Cosentino, S.; Turner, R.E.; Deeks, J.M.; Brochier, T.; Rughooputh, T.; Bance, M.; Carlyon, R.P. The Panoramic ECAP Method: Estimating Patient-Specific Patterns of Current Spread and Neural Health in Cochlear Implant Users. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2021, 22, 567–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Briaire, J.J.; Stronks, H.C.; Frijns, J.H.M. Speech Perception Performance in Cochlear Implant Recipients Correlates to the Number and Synchrony of Excited Auditory Nerve Fibers Derived From Electrically Evoked Compound Action Potentials. Ear Hear. 2022, 44, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanen, M.; Strahl, S.; Schwarz, K. Insights Into Electrophysiological Metrics of Cochlear Health in Cochlear Implant Users Using a Computational Model. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2024, 25, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanen, M.; Seeber, B.U. A Phenomenological Model Reproducing Temporal Response Characteristics of an Electrically Stimulated Auditory Nerve Fiber. Trends Hear. 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Deeks, J.M.; Goehring, T.; Borsetto, D.; Bance, M.; Carlyon, R.P. SpeedCAP: An Efficient Method for Estimating Neural Activation Patterns Using Electrically Evoked Compound Action-Potentials in Cochlear Implant Users. Ear Hear. 2022, 44, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, S.; Gaudrain, E.; Deeks, J.M.; Carlyon, R.P. Multistage nonlinear optimization to recover neural activation patterns from evoked compound action potentials of cochlear implant users. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 63, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Goehring, T.; Cosentino, S.; Turner, R.E.; Deeks, J.M.; Brochier, T.; Rughooputh, T.; Bance, M.; Carlyon, R.P. The Panoramic ECAP Method: Estimating Patient-Specific Patterns of Current Spread and Neural Health in Cochlear Implant Users. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2021, 22, 567–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isnanto, R.R.; Windarto, Y.E.; Mangkuratmaja, M.V. Assessment on Image Quality Changes as a Result of Implementing Median Filtering, Wiener Filtering, Histogram Equalization, and Hybrid Methods on Noisy Images. 2020 7th International Conference on Information Technology, Computer, and Electrical Engineering (ICITACEE). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndonesiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 185–190.

- Gupta, G. Algorithm for image processing using improved median filter and comparison of mean, median and improved median filter. International Journal of Soft Computing and Engineering 2011, 1, 304–311 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M. Comparison of processing results of median filter and mean filter on Gaussian noise. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2023, 5, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Lu, G.; Ye, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Cao, D. The State-of-the-Art Review on Applications of Intrusive Sensing, Image Processing Techniques, and Machine Learning Methods in Pavement Monitoring and Analysis. Engineering 2021, 7, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, C. An Improved Median Filtering Algorithm for Image Noise Reduction. Phys. Procedia 2012, 25, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D. A study on adaptive filtering for noise and echo cancellation. Master’s thesis, University of Windsor, 2005.

- Yazdanpanah, H.; Diniz, P. S. R. Recursive least-squares algorithms for sparse system modeling. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef], 5-9 March.

- Creighton, J.; Doraiswami, R. Real time implementation of an adaptive filter for speech enhancement. In Proceedings of the Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering, Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 2004. [CrossRef], 2-5 May.

- Wang, P.; Kam, P.-Y. An automatic step-size adjustment algorithm for LMS adaptive filters, and an application to channel estimation. Phys. Commun. 2012, 5, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizou, P. C. Speech Enhancement: Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; CRC Press: New York, USA, 2007; pp. 143–208. [Google Scholar]

- Benesty, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y. Microphone Array Signal Processing, Springer: Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 8–15.

- Ephraim, Y.; Malah, D. Speech enhancement using a minimum mean-square error log-spectral amplitude estimator. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech, Signal Process. 1985, 33, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgstrom, B.J.; Alwan, A. Log-spectral amplitude estimation with Generalized Gamma distributions for speech enhancement. ICASSP 2011 - 2011 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, Czech RepublicDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 4756–4759.

- Hirszhorn, A.; Dov, D.; Talmon, R.; Cohen, I. Transient interference suppression in speech signals based on the OM-LSA algorithm. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Acoustic Echo and Noise Control, Aachen, Germany, 2012. [CrossRef], 4-6 September 4-6.

- Hsu, Y.; Bai, M.R. Learning-based robust speaker counting and separation with the aid of spatial coherence. EURASIP J. Audio, Speech, Music. Process. 2023, 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.; Lee, Y.; Bai, M.R. Array configuration-agnostic personalized speech enhancement using long-short-term spatial coherence. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 154, 2499–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, G.; Smaragdis, P.; Gannot, S.; Naylor, P.A.; Makino, S.; Kellermann, W.; Sugiyama, A. Audio Signal Processing in the 21st Century: The important outcomes of the past 25 years. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2023, 40, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannot, S.; Tan, Z.-H.; Haardt, M.; Chen, N.F.; Wai, H.-T.; Tashev, I.; Kellermann, W.; Dauwels, J. Data Science Education: The Signal Processing Perspective [SP Education]. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2023, 40, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Wang, D. A Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network for Real-Time Speech Enhancement. Interspeech 2018. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Bianco, M.J.; Gerstoft, P.; Traer, J.; Ozanich, E.; Roch, M.A.; Gannot, S.; Deledalle, C.-A. Machine learning in acoustics: Theory and applications. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2019, 146, 3590–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Step 1. Initialization of for each frequency bin For each and : Step 2. Estimation of If , then , else Step 3. Estimation of using Equation (16) If , then Equation (16) can be rewritten as Step 4. check the VAD criterion If , then using Equation (20) for updating Step 5. Calculation of using Equation (15) Step 6. Calculation of using Equation (21) End for |

|

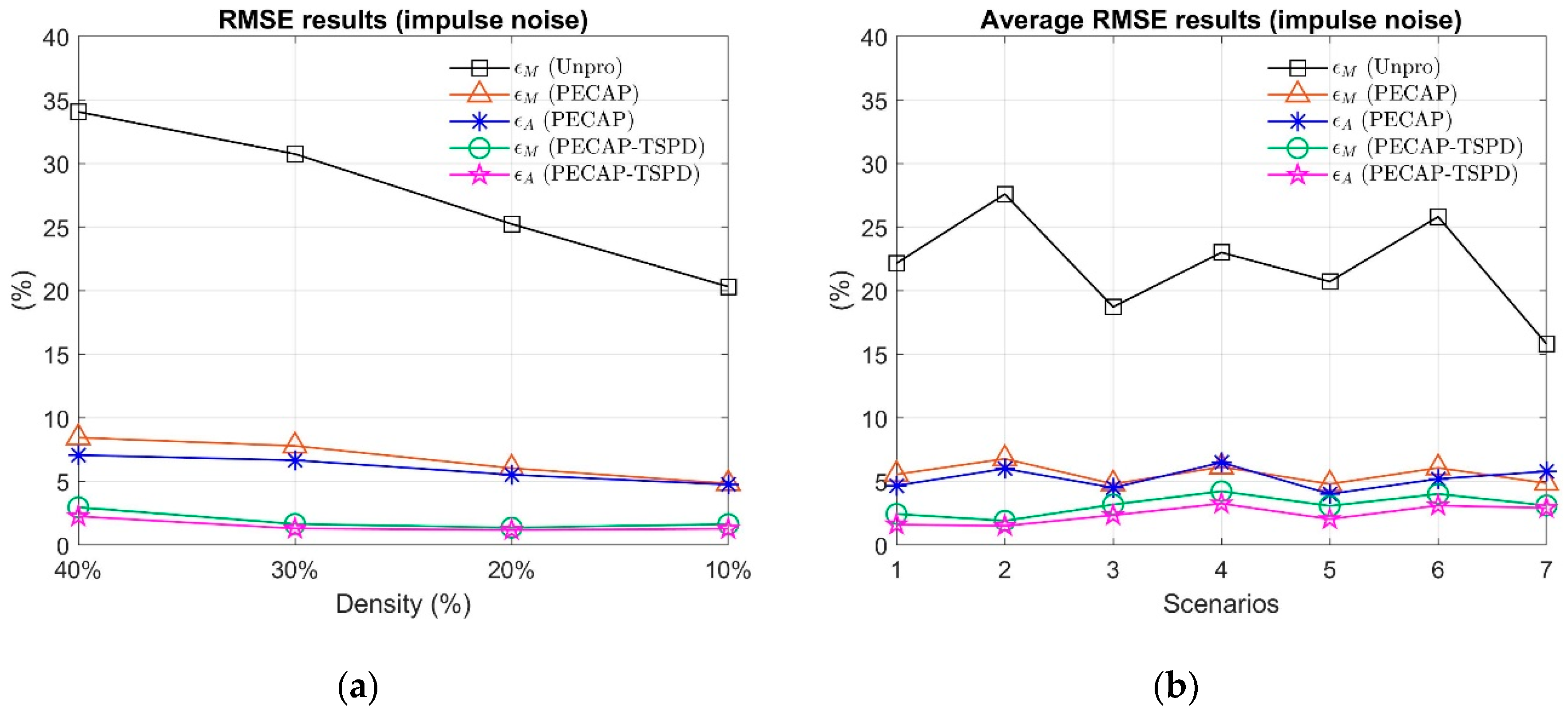

Scenario 1: , , , where in this study. Scenario 2: , , . Scenario 3: , . , , , . , . Scenario 4: , . , , , . , . Scenario 5: , . , , , . , . Scenario 6: , . , , , . , . Scenario 7: , . , , , , , , |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).