1. Introduction

Soil is home to an incredibly diverse and adaptable community of microorganisms. These microbes are constantly exposed to tough and changing conditions—fluctuating temperatures, varying moisture levels, changes in salinity and pH, and even heavy metal pollution. To survive and thrive in such environments, microbes rely on a range of genetic and epigenetic tools, including transcriptional regulation, horizontal gene transfer, signaling pathways, and DNA methylation [

1,

2,

3]. While these systems are effective at helping microbes respond to their surroundings, recent genomic research is shedding light on another layer of adaptation that’s simpler, faster, and possibly just as important.

At the center of this emerging research are tandem repeat sequences, particularly a subset known as ultra-short DNA satellites. These consist of very short stretches of DNA—just 2 to 15 base pairs—repeated over and over in a row [

4]. What makes these short tandem repeats (STRs) so interesting is their tendency to change quickly. They can expand or contract during DNA replication or repair, especially when the organism is under stress [

5,

6,

7].

In eukaryotes, STRs are well-known for their roles in gene regulation, genome organization, and disease, especially in disorders like Huntington’s disease where certain triplet repeats go rogue [

8]. They can influence gene expression by altering promoter structure, affecting where transcription factors bind, or interfering with how efficiently genes are translated [

9,

10]. But in bacteria and archaea—the key players in soil ecosystems—STRs have only recently come into focus. Thanks to advancements in long-read sequencing technologies like Oxford Nanopore and PacBio, researchers are now able to detect these repetitive regions with far greater accuracy [

11,

12].

In microbial communities found in soil, STRs are showing up all over the place—between genes, in promoter regions, and even within coding sequences. Their locations suggest they could play important roles in shaping how microbes behave, especially since changes in repeat length can tweak protein functions or turn genes on and off [

13]. Their ability to mutate quickly and reversibly, and their tendency to appear near regulatory regions, make STRs exciting candidates as real-time sensors of environmental change [

14,

15,

16].

In this review, we take a closer look at what we currently know about these ultra-short DNA satellites in soil microbes. We explore how they’re structured, where they’re found, and how they behave under stress. We also highlight the computational tools that help us find them in messy metagenomic datasets, review laboratory evidence that they respond to environmental changes, and discuss how they might be used in the future—for example, as biosensors or tools in synthetic biology to help monitor or improve soil health.

2. Structural and Functional Characteristics of Ultra-Short Tandem Repeats

2.1. Definition and Classification

Short tandem repeats (STRs), also known as microsatellites, are tiny stretches of DNA made up of repeating units that range from 2 to 15 base pairs in length [

17]. While they may seem simple, these sequences are quite distinct from other types of repetitive DNA. For example, minisatellites have longer repeat units (more than 15 bp), and satellite DNA—typically found in centromeres or telomeres—is even larger and more structurally complex, especially in eukaryotic genomes [

18].

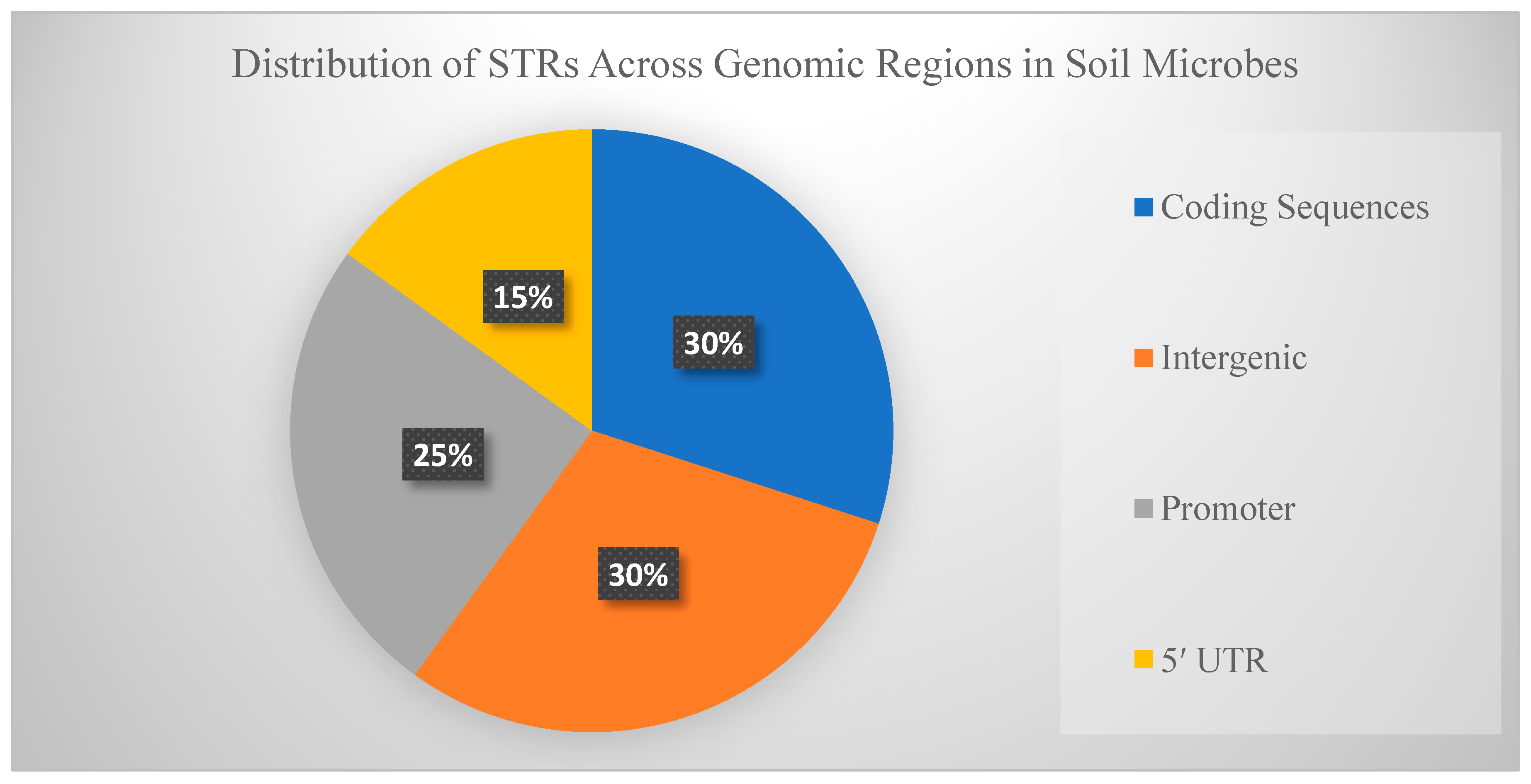

In bacteria and other prokaryotes, STRs aren’t randomly scattered. Instead, they tend to show up in some key genomic regions where they can have real functional impact:

In intergenic regions, they may influence how tightly DNA is wound or how far apart genes are spaced.

In promoter regions, changes in STR length can adjust how efficiently a gene gets turned on.

In the 5′ untranslated regions (5′ UTRs), they can affect how stable an mRNA molecule is, or how easily it’s translated into protein.

Inside coding regions, changes in the number of repeats can cause frameshifts, potentially leading to new protein variants or even nonfunctional truncated proteins [

19,

20], see

Table 1 and

Figure 1.

Thanks to the improved resolution of long-read sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore and PacBio, researchers have begun to uncover just how widespread and important STRs are in microbial genomes—far more than previously thought [

21].

2.2. Mechanisms of STR Instability

One of the most fascinating (and frustrating) aspects of STRs is how unstable they are. These short sequences are prone to rapid changes, which makes them both a challenge to study and a powerful tool for genetic flexibility. Three main biological processes are behind this instability:

Replication slippage: During DNA replication, the enzyme DNA polymerase can temporarily lose its place on the template strand. When it reattaches, it might misalign by a repeat or two—causing the newly copied DNA to have more or fewer repeats than the original [

22].

Recombination events: STRs with symmetrical or repetitive sequences can misalign during recombination, especially during genetic exchange between similar DNA strands. This can lead to increased variation in repeat length [

23].

DNA repair errors: When DNA mismatches or damage are repaired—especially in microbes with low-fidelity repair systems—STRs are often hotspots for errors. These imperfect repairs can amplify instability, especially in fast-growing microbes [

24].

The rate at which STRs mutate doesn’t just depend on the mechanisms above. It’s also influenced by the length of the repeat unit, its nucleotide composition, and the secondary structures it forms—such as loops or hairpins, particularly in GC-rich repeats [

25].

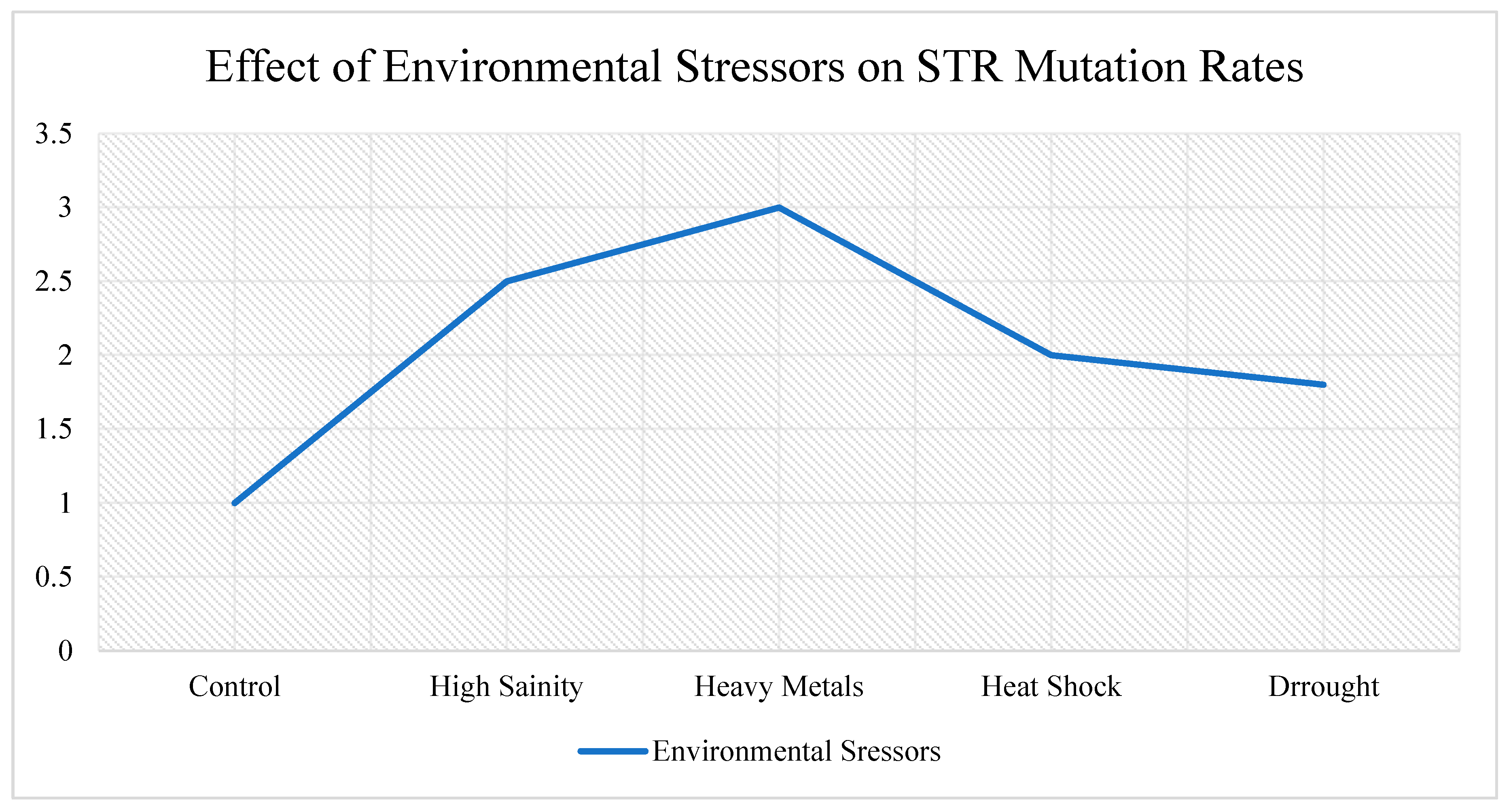

Importantly, environmental stress plays a big role. Factors like oxidative stress, heat shock, or salt imbalance can accelerate STR mutations, acting almost like a built-in mechanism for adaptive plasticity—a quick way for microbes to explore new traits without large-scale genomic changes [

26,

27].

Interestingly, studies have also shown that STR slippage during DNA replication isn’t always symmetrical. The leading and lagging strands might show different biases for expansion or contraction, depending on the DNA polymerase involved and the specific repeat sequence [

28].

2.3. STRs in Prokaryotic Gene Regulation

While STRs are often recognized for their high mutation rates, they may do more than just introduce variability—they could also play direct roles in regulating gene expression in bacteria and archaea. In fact, several mechanisms have been proposed, and some have already been observed in action, particularly in well-studied pathogens.

Frameshifting in coding regions: One of the most striking ways STRs can affect genes is by causing a shift in the reading frame. When repeat numbers change inside a coding sequence, they can add or delete nucleotides in a way that disrupts the original reading frame. This can lead to truncated proteins or completely altered protein domains. Some bacteria, like

Neisseria and

Haemophilus, actually use this mechanism on purpose in a strategy known as phase variation. It allows them to switch gene expression on and off, helping them evade the host immune system by altering their surface proteins [

29].

Promoter modulation: STRs located in or near promoter regions can affect how transcription is initiated. By changing the number of repeats, the spacing between important regulatory elements—such as transcription factor binding sites or the transcription start site (TSS)—can shift. This can either enhance or weaken the expression of nearby genes, depending on the context [

30].

Transcription factor binding: STR variation can also tweak how easily transcription factors bind to DNA. If the repeat sequence overlaps or is close to a regulatory binding site, even a small change in repeat length might improve or reduce the factor’s ability to recognize the site. This provides microbes with a simple but effective mechanism for adjusting gene activity in response to environmental changes [

31].

One especially fascinating idea is that STRs may help microbes use a "bet-hedging" strategy. In this model, even genetically identical cells in the same population can express different traits because of random variation in STR length. This diversity increases the chances that at least some cells will survive if conditions suddenly change [

32]. Because STR changes are often reversible, microbes don’t have to commit to a permanent mutation—they can try out a trait temporarily and then revert if it’s no longer beneficial.

In this way, STRs act as tunable switches, offering bacteria a flexible and low-cost way to generate diversity, control gene expression, and adapt to their environments—especially in complex ecosystems like soil.

3. Distribution and Prevalence in Soil Microbiomes

3.1. Metagenomic Evidence

In recent years, the use of long-read sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore and PacBio SMRT, has revolutionized how we explore microbial genomes—especially when it comes to identifying repetitive DNA elements like ultra-short tandem repeats (STRs) [

33,

34]. Unlike traditional short-read methods, which often struggle to correctly assemble repetitive regions, long-read platforms can span entire STR regions, giving researchers a much clearer picture of how frequent and diverse these sequences really are [

35].

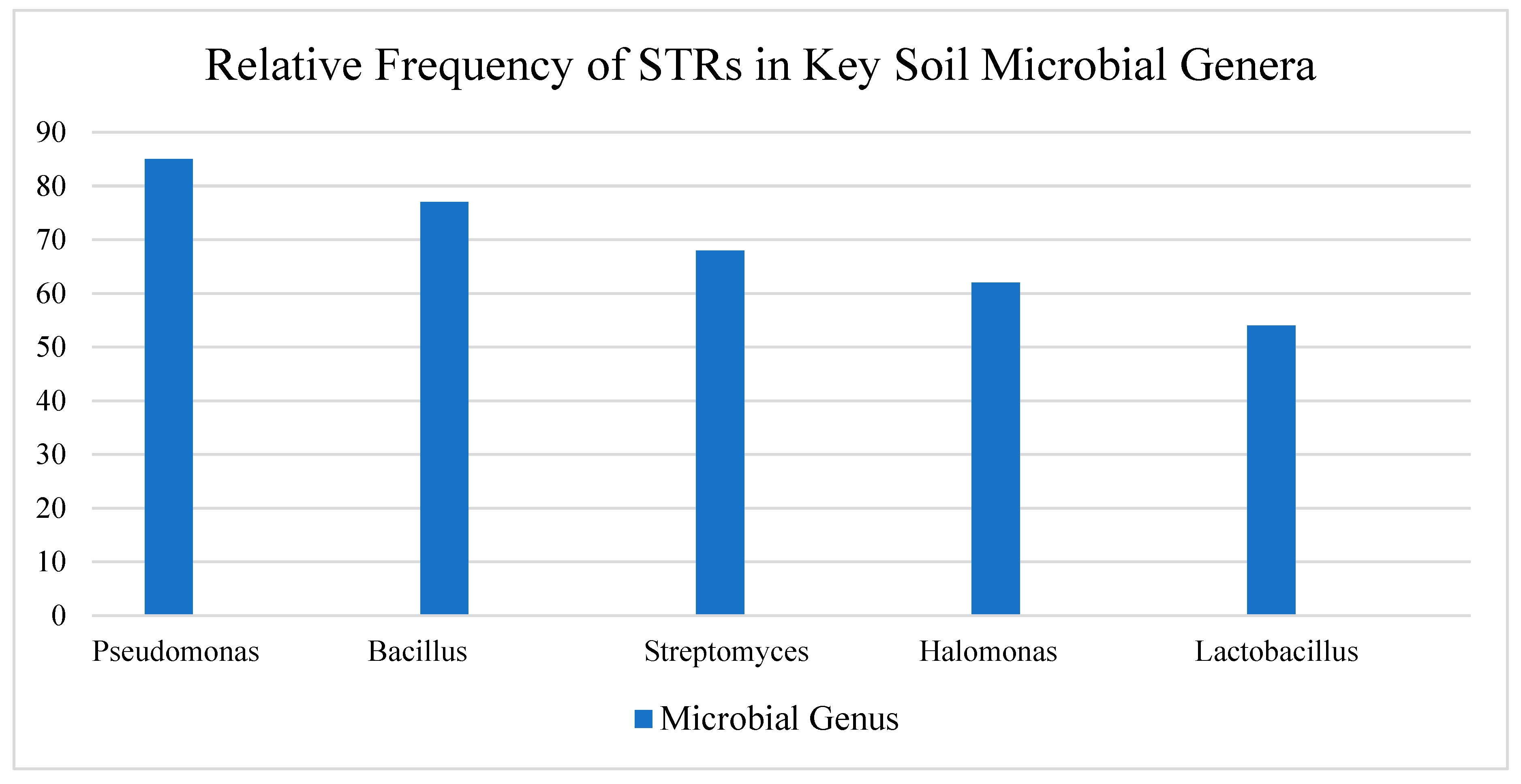

Thanks to these tools, scientists analyzing soil microbiomes from around the world have discovered thousands of STR loci in the genomes of both bacteria and archaea. Many of these repeats had gone unnoticed in earlier studies. Interestingly, certain microbial groups—such as Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Streptomyces, and even some extremophilic archaea found in salty or desert-like environments—tend to have particularly high densities of STRs [

36,

37]. These microbes are already known for their toughness and metabolic versatility, hinting that STRs might be helping them adapt to their challenging habitats, see

Table 2.

Digging deeper into their genomes, researchers have found that many STRs are clustered in regions with high biological activity, including:

Mobile genetic elements, like plasmids and transposons,

Stress-response genes, such as those involved in heat shock responses, efflux systems, or protein folding (e.g., chaperonins),

And key metabolic regulators, including genes related to nitrogen fixation, phosphate metabolism, and secondary metabolite production [

38,

39], see

Figure 2.

These “hotspots” suggest that STRs may act as genomic tuning knobs—allowing microbes to quickly adjust their gene expression and phenotypes in response to environmental changes. In a diverse and ever-changing ecosystem like soil, this kind of flexibility could make a big difference in survival and ecological success.

3.2. Environmental Correlations

Several recent studies have also begun to reveal how specific types of STRs respond to environmental stressors, showing patterns that link repeat expansion or contraction to real-world ecological pressures:

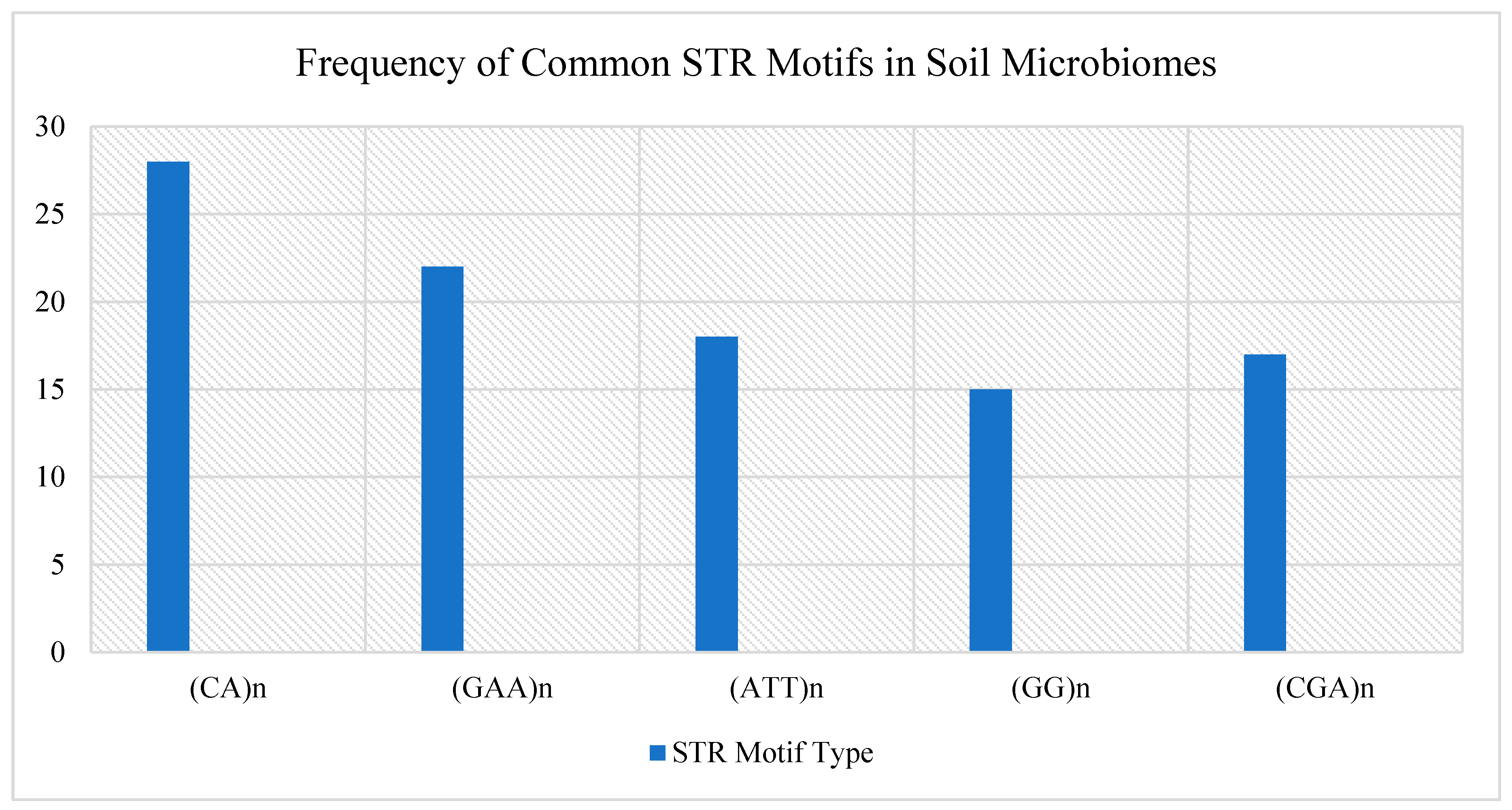

Soil salinity: In saline soils, researchers have observed expansions of (CA)n repeats in salt-tolerant bacteria. These repeats are often located near regulatory regions, suggesting they may help turn on genes needed for osmotic stress resistance [

40,

41].

Heavy metal contamination: In soils polluted with cadmium, lead, or other heavy metals, STRs like (AAT)n and (GAA)n tend to expand near genes responsible for metal detoxification—including metallothioneins and ATP-binding transporters [

42]. These changes could help microbes better cope with toxic environments, either by enhancing gene expression or creating phenotypic diversity in the population.

Moisture and drought stress: In dry or arid regions, microbes that can tolerate desiccation often show a contraction of STR regions. This might act as a genomic stabilizer, reducing the risk of harmful replication errors when cells are under stress. Some microbes also display seasonal shifts in STR patterns, which suggests they’re using STR dynamics to adjust gene expression across different moisture conditions [

43,

44], see

Table 3.

Altogether, these findings point to a bigger picture: STR variation is not random—it may serve as a genomic signature of environmental pressure. The presence or pattern of STRs in microbial genomes could potentially act as a biomarker for soil health, helping us understand how communities respond to pollution, drought, salinity, or even climate change. They may also reflect ongoing evolutionary adaptation in real time, giving us a window into how microbes evolve in response to their environment.

4. Environmental Sensing Potential of Strs

4.1. STRs as Genomic Switches

One of the most fascinating features of short tandem repeats (STRs), especially ultra-short DNA satellites, is their potential to function as natural gene switches in microbial genomes. These sequences can act almost like tiny dials, fine-tuning gene activity depending on how many repeat units are present. In fact, STRs are capable of turning genes on or off (a binary response) or adjusting expression levels gradually (an analog response), simply based on changes in their length [

45].

These changes don’t require complicated regulatory pathways. Instead, STRs can:

Introduce or remove start codons or promoter elements, directly controlling whether a gene is transcribed.

Change the spacing between regulatory elements—like transcription factor binding sites—altering how strongly a gene is activated.

Influence mRNA translation by modifying structures in the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR), which can affect transcript stability and how easily ribosomes bind.

What makes this system particularly impressive is its simplicity and energy efficiency. Unlike classic gene regulation, which depends on the production of proteins like transcription factors or signaling molecules, STR-based control needs no additional resources. It's essentially built into the replication process: as DNA is copied, STRs naturally expand or contract through replication slippage or repair errors. This makes STR-mediated regulation especially useful in resource-limited or stressful environments—like arid deserts, salty soils, or polluted sites—where conserving energy is crucial for survival [

46,

47].

This fast, reversible system resembles a strategy known as bet-hedging, where members of a microbial population diversify their gene expression profiles. That way, some individuals are always prepared for unexpected changes in their environment, increasing the odds that at least a portion of the population will survive [

48]. In this light, STRs aren’t just repetitive sequences—they’re dynamic tools that help microbes adapt on the fly.

4.2. Evidence from In Vitro Stress Studies

While the theory behind STR-based gene regulation is compelling, lab-based studies have also shown clear evidence that STRs respond to environmental stress in real time. Several experiments have demonstrated that when bacteria are exposed to stressful conditions, changes in STR length can be observed—often near genes involved in stress responses.

Heat shock conditions: In thermotolerant bacteria, STRs located near chaperonin genes such as groES and dnaK have been seen to expand or contract when the cells are exposed to high temperatures. These changes often correlate with increased expression of heat-protective genes, suggesting that STR variation is part of the heat response system [

49].

Osmotic and acid stress: In bacteria like Halomonas (which tolerates salt) and Lactobacillus (which tolerates acid), STR profiles shift when the microbes are cultured in high-salt or low-pH environments. These changes are frequently found near genes involved in osmoadaptation, supporting the idea that STRs play a role in environmentally driven gene regulation [

50].

Pollutant exposure: STRs located near genes that handle toxic compounds—such as efflux pumps, redox enzymes, and hydrocarbon-degrading proteins—have shown variation in length when bacteria are grown in the presence of pollutants like toluene, benzene, cadmium, and arsenic. In some cases, the expanded repeats were linked to greater survival and improved detoxification, strengthening the argument that STRs help microbes adapt to contaminated environments [

51,

52], see

Table 4.

Together, these studies support the idea that STRs act as genomic memory elements. That is, once a cell experiences stress, STR changes may leave a heritable but flexible “mark” that adjusts how the cell or its descendants respond in the future. It’s a powerful example of how simple DNA motifs can encode complex environmental experiences.

4.3. Synthetic Biology Applications

Thanks to their programmable nature, high mutation potential, and ability to respond dynamically to the environment, short tandem repeats (STRs) are beginning to attract attention in synthetic biology. Although this potential is still largely untapped, STRs could be engineered to perform a variety of useful functions in both environmental and agricultural contexts. Here are a few promising directions where STRs could make a big impact:

Field diagnostics: Imagine being able to “ask” microbes how stressed their environment is. By inserting synthetic STR circuits into soil-dwelling bacteria and linking these to reporter genes—like GFP (green fluorescent protein) or luciferase—researchers could create microbes that glow or signal in response to stressors like heavy metals, salinity, or low pH [

53]. These engineered biosensors could provide real-time, low-cost monitoring tools for environmental assessments in agriculture, mining, or conservation.

Bioremediation and biofertilizers: Another exciting application is in designing smart microbial helpers for soil health. Beneficial microbes like Rhizobium or Bacillus subtilis could be engineered with STR-controlled switches to turn on useful pathways—such as nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, or the breakdown of toxic chemicals—only when needed. This would make these microbes more efficient and reduce the strain of unnecessary gene expression, especially in environments where energy is limited [

54].

Microbial memory circuits: STRs could also serve as the foundation for biological memory devices. In these systems, the length of a specific STR would act as a “recording mechanism,” encoding information about past exposures—like temperature spikes, toxin levels, or drought events. This concept opens up possibilities for programmable biosystems that not only sense their environment but also remember and respond accordingly, which is particularly useful in soil microbiome engineering and environmental archiving [

55], see

Table 5.

Despite these exciting possibilities, there are still challenges ahead. Current tools for precisely controlling STR length and maintaining stability under changing environmental conditions need to be improved. Microbial population dynamics—especially in complex systems like soil—can also complicate outcomes. Still, with the rapid advancement of synthetic biology, genome editing, and computational modeling, STR-based technologies could soon become central tools for monitoring and managing the environments where microbes live and work.

5. Bioinformatic Tools for STR Detection in Environmental Genomes

Spotting short tandem repeats (STRs) in microbial and environmental genomes isn’t always easy. These sequences are small, repetitive, and highly mutable—which makes them both fascinating to study and difficult to analyze. Traditional genome assembly tools often collapse repetitive regions or miss them altogether, especially in fragmented or complex metagenomic samples [

56]. As a result, STRs are often underrepresented in standard microbial genome datasets, see

Table 6.

To overcome these challenges, researchers have developed a range of bioinformatic tools that are specifically designed to detect STRs with varying levels of precision, flexibility, and speed. Here’s a look at some of the most commonly used tools in STR detection, particularly for microbial and environmental samples:

While these tools have advanced STR research significantly, they each have drawbacks when applied to environmental microbiomes—which are often messy, fragmented, and poorly annotated. In many cases, the lack of reference genomes and the high diversity of soil microbes further complicate STR detection.

Need for Next-Generation Pipelines

To truly understand how STRs function and evolve in natural ecosystems, we need more powerful and integrated computational solutions. Future STR analysis pipelines should bring together:

Long-read sequencing data (e.g., Oxford Nanopore, PacBio), which can span entire STR regions and maintain repeat architecture.

Machine learning models capable of telling apart real biological STR variation from sequencing errors or noise.

Environmental metadata, such as soil pH, salinity, or heavy metal concentrations, to link STR variation to ecological context.

Custom assembly and annotation strategies tailored for STR-rich and diverse metagenomes.

Several emerging platforms are moving in this direction. For instance, STRique and NanoSTR are being developed to leverage real-time signal processing and long-read accuracy for detecting STRs in complex samples [

61,

62]. These tools promise to improve not only STR detection, but also our ability to explore how these elements shape microbial adaptation across different environments.

Ultimately, the integration of genomics, computational biology, and environmental science will be essential for turning STRs into powerful ecological indicators and functional regulators in microbial ecosystems.

6. Challenges and Knowledge Gaps

Although ultra-short tandem repeats (STRs) are increasingly viewed as potential key players in microbial adaptation, our current understanding of their function—especially in environmental microbiomes—remains limited. Several important technical and conceptual hurdles continue to restrict how effectively we can study and apply STRs in microbial ecology and synthetic biology, see

Table 7, and

Figure 3.

6.1. Functional Validation Remains Speculative

There’s growing evidence that STRs can influence gene activity, but so far, most of the support is correlational rather than causal. Many STRs found in microbial genomes are still unannotated, or simply classified as part of non-coding DNA. Only a few model organisms—like

Neisseria and

Haemophilus—have provided clear experimental proof that STR changes directly control gene expression, such as in phase variation mechanisms that help pathogens evade immune responses [

63,

64].

In soil microbes, which tend to be less studied and more genetically diverse, these links are much harder to establish. Even when STRs sit close to regulatory regions, we don’t yet know if their variation is functionally adaptive or just a side effect of genome instability. To clarify this, tools like CRISPR-based genome editing are needed to test the precise impact of STR changes in diverse microbial backgrounds [

65].

6.2. STR–Gene Interaction Networks Are Poorly Mapped

Compared to well-studied regulatory systems—like transcription factor networks or operons—STR-based gene regulation remains a mystery. We currently lack any large-scale database or ontology that links STRs to their regulatory targets. This makes it difficult to predict what effect STR variation will have on gene expression, metabolism, or microbial behavior [

66].

Another key limitation is that STRs may not act alone. In bacteria with operon-based gene organization, a single STR could potentially influence multiple genes downstream. Yet these network-level effects haven’t been systematically explored, particularly in high-throughput experiments like transposon mutagenesis or RNA-seq studies of STR mutants [

67].

6.3. Tracking STR Changes in the Environment Is Technically Difficult

Studying STR behavior in situ—that is, directly in natural soil settings—is no small feat. Several technical barriers complicate the process:

DNA degradation and contamination in soil samples can distort results.

Low-abundance microbial species may carry unique STR variants that are difficult to detect.

Short-read sequencing technologies, still widely used, often introduce artifacts or fail to resolve STR length accurately.

Long-read sequencing has helped improve STR resolution, but even this has limits—particularly in homopolymeric or complex repeat regions, which are prone to sequencing errors [

68]. Tools like STRique are being developed to monitor STRs in real-time, but these approaches are still experimental and not yet ready for large-scale, diverse microbiome applications [

69].

6.4. Environmental Selection on STRs Remains Poorly Understood

Even though we’ve seen patterns between STR variation and environmental stressors (like salinity or metal contamination), the mechanisms driving these patterns are not well explained. For example, repeat expansions like (CA)ₙ in saline soils are clearly associated, with osmotic stress, but we don’t yet understand how or why these repeats evolve that way [

70], see

Table 8, and

Figure 4.

In addition, the evolutionary implications of STR-mediated adaptation are still largely unknown. Key questions remain unanswered:

Are there fitness trade-offs to STR variability?

How do STRs spread or persist across microbial populations over time?

Do they undergo horizontal gene transfer?

Answering these questions will require long-term field studies, as well as tools from population genomics and evolutionary modeling, to place STR dynamics in a broader ecological and evolutionary context [

71].

7. Future Directions

As interest in ultra-short tandem repeats (STRs) continues to grow, especially within the field of environmental microbiology, several exciting research opportunities are beginning to take shape. These efforts will not only deepen our understanding of STR function in microbial communities but may also open up new applications in biosensing, biotechnology, and ecosystem monitoring. Below are some of the most promising directions for future exploration:

7.1. Functional Genomics with CRISPR-Based Editing

One of the most pressing challenges is proving that STRs directly affect gene function, rather than just coincidentally appearing near important genes. Thanks to recent advances in CRISPR-Cas genome editing, scientists can now precisely modify STR regions—expanding, shrinking, or deleting them entirely—to test their effects [

72].

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and activation (CRISPRa) systems can be used to dial gene expression up or down near STR sites. When combined with tools like RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and proteomics, these approaches can help researchers determine whether STRs act as on/off switches, tunable expression knobs, or threshold-based triggers in microbial gene regulation [

73].

This kind of targeted editing could reveal entirely new layers of regulatory logic in soil microbes and offer synthetic biologists precise tools to reprogram them.

7.2. Field-Deployable STR Biosensors

Because certain STR patterns are tied to specific environmental stressors, they hold great promise as natural biosensors. Imagine a soil test kit that uses STR-based qPCR to detect early signs of salinity stress, metal pollution, or drought. Specific repeats, like (CA)ₙ or (AAT)ₙ, could be linked to known environmental pressures, making them useful biomarkers for soil health [

74].

To make these diagnostics more accessible, researchers are exploring isothermal amplification methods like LAMP, which don’t require advanced lab equipment. Such biosensors could be used on farms, in conservation areas, or at contaminated sites—providing fast, affordable, and actionable environmental insights [

75].

7.3. Global Comparative STR Ecology

We still know surprisingly little about how STRs vary across ecosystems. By conducting large-scale, comparative studies of STRs in soil microbiomes from deserts, rainforests, tundra, aquatic environments, and urban or agricultural zones, scientists can begin to uncover biogeographic patterns in STR diversity [

76].

Standardized pipelines for detecting and analyzing STRs—paired with detailed environmental metadata like soil pH, temperature, altitude, and land use—will be key to identifying which STRs are universal stress indicators and which are specific to certain ecosystems. These insights could help refine ecological monitoring systems and even guide microbiome-based restoration efforts.

7.4. Linking STRs with Epigenomics and Genome Architecture

STRs don’t act alone—they likely work in tandem with other layers of epigenetic regulation, including DNA methylation, binding of nucleoid-associated proteins, and DNA supercoiling [

77]. To fully understand how STRs influence microbial function, we need to explore these relationships at the systems level.

Emerging tools like nanopore-based methylation sequencing, Hi-C (for studying 3D genome architecture), and ChIP-seq adapted for bacterial chromatin could reveal whether STRs are embedded within epigenetically active or structured regions, and how STR length affects gene accessibility and expression [

78].

Furthermore, it's possible that environmental stress triggers changes not only in STR length but also in epigenetic marks—suggesting that microbes may use STRs as part of a broader genomic “memory” system to remember and respond to past conditions, see

Table 9.

8. Conclusion

Ultra-short tandem repeats (STRs) have long been overlooked as genomic "noise" or evolutionary remnants; however, emerging evidence suggests they may play critical roles in microbial adaptability, gene regulation, and environmental sensing. In the context of soil microbiomes, where microbes are constantly subjected to fluctuating conditions—including changes in pH, salinity, moisture, temperature, and pollutant exposure—STRs offer a rapid, reversible, and energetically efficient mechanism for fine-tuning genetic responses.

This review has synthesized current knowledge on the structure, distribution, and potential functionality of ultra-short DNA satellites in prokaryotes, highlighting how recent advances in long-read metagenomics and bioinformatics have unveiled their widespread presence in key environmental bacterial taxa such as Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Streptomyces. STRs are frequently associated with mobile genetic elements and stress-response loci, suggesting a strategic placement in genomic regions linked to survival and resilience.

Despite this progress, major knowledge gaps persist. Most STRs lack direct functional validation, and their roles in transcriptional or post-transcriptional regulation remain speculative in many non-model microbes. Moreover, the challenge of detecting STR dynamics in situ, especially in diverse and low-biomass soil environments, continues to limit ecological insight. Tools such as TRF, Phobos, RepeatExplorer, and HipSTR offer useful starting points for STR discovery, but future analytical frameworks must integrate machine learning, long-read accuracy, and environmental metadata to be fully effective.

Looking ahead, the field is poised for transformative advances through the application of CRISPR-based STR editing, development of field-deployable STR biosensors, and comparative metagenomics across global biomes. Furthermore, integrating STR studies with epigenetic profiling and 3D genome mapping could uncover complex, multiscale regulatory networks underpinning microbial life in soils.

In sum, ultra-short DNA satellites represent a frontier of microbial genome science—not only as markers of genomic plasticity but as dynamic, evolvable elements that encode adaptive potential. Unlocking their regulatory logic and ecological significance may yield new insights into microbial evolution, soil health monitoring, and the development of smart microbial tools for agriculture, remediation, and climate resilience.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declare no conflicts of interest related to this study. No competing financial interests or personal relationships could have influenced the content of this research review.

Acknowledgments

The author extends sincere gratitude to Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, particularly the Department of Biology, College of Science, for their continuous academic support and research guidance. This work also benefited from scholarly discussions and insights provided by colleagues in the field of microbial genomics and environmental molecular biology.

AI Declaration

No artificial intelligence (AI) tools or automated writing assistants were used in the research, drafting, or editing of this manuscript. The content, including the literature review, analysis, and writing, was entirely produced by the authors. All conclusions and interpretations are based on human expertise, critical evaluation of the literature, and independent scholarly work.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical Approval Statement

As this is a review article, no new human or animal data were collected, and thus, ethical approval was not required.

Data Availability Statement

No new datasets were generated or analyzed during this study. All data supporting this review are derived from previously published sources, which have been appropriately cited.

References

- Storz, G.; Hengge, R. (2011). Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press.

- Casadesús, J.; Low, D. Epigenetic gene regulation in the bacterial world. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2006, 70, 830–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Bardgett, R.D.; Van Straalen, N.M. The unseen majority: Soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity. Ecology Letters 2008, 11, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.M. The contribution of slippage-like processes to genome evolution. Journal of Molecular Evolution 1995, 41, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemayel, R.; Vinces, M.D.; Legendre, M.; Verstrepen, K.J. Variable tandem repeats accelerate evolution of coding and regulatory sequences. Annual Review of Genetics 2010, 44, 445–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, D.; Wills, C. Long, polymorphic microsatellite loci in simple organisms. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 1996, 263, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxon, R.; Bayliss, C.; Hood, D. Bacterial contingency loci: The role of simple sequence DNA repeats in bacterial adaptation. Annual Review of Genetics 2006, 40, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkin, S.M. Expandable DNA repeats and human disease. Nature 2007, 447, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinces, M.D.; Legendre, M.; Caldara, M.; Hagihara, M.; Verstrepen, K.J. Unstable tandem repeats in promoters confer transcriptional evolvability. Science 2009, 324, 1213–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemayel, R.; Cho, J.; Boeynaems, S.; Verstrepen, K.J. Beyond junk-variable tandem repeats as facilitators of rapid evolution of regulatory and coding sequences. Genes 2012, 3, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; et al. Improved data analysis for the MinION nanopore sequencer. Nature Methods 2016, 12, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, A.; Au, K.F. PacBio sequencing and its applications. Genomics Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2015, 13, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slechta, E.S.; et al. Effect of microsatellite repeats on gene expression. Molecular Microbiology 2002, 43, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, G.F.; et al. Comparative genomics of tandem repeats in Eukaryotes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2008, 25, 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schlötterer, C. Evolutionary dynamics of microsatellite DNA. Chromosoma 2000, 109, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farabaugh, P.J. Translational frameshifting: Implications for the mechanism of translational frame maintenance. Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology 2000, 64, 131–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegren, H. Microsatellites: Simple sequences with complex evolution. Nature Reviews Genetics 2004, 5, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, B.; Sniegowski, P.; Stephan, W. The evolutionary dynamics of repetitive DNA in eukaryotes. Nature 1994, 371, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odah, M.A.A. Unlocking the genetic code: Exploring the potential of DNA barcoding for biodiversity assessment. AIMS Mol. Sci. 2023, 10, 263–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, S.; Rivals, E.; Jarne, P. DNA slippage occurs at microsatellite loci through the persistence of secondary structures. BMC Genomics 2007, 8, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Treangen, T.J.; Salzberg, S.L. Repetitive DNA and next-generation sequencing: Computational challenges and solutions. Nature Reviews Genetics 2012, 13, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisson, M.J.; et al. Resolving the complexity of the human genome using single-molecule sequencing. Nature 2015, 517, 608–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinson, G.; Gutman, G.A. Slipped-strand mispairing: A major mechanism for DNA sequence evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution 1987, 4, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovett, S.T. Encoded errors: Mutations and rearrangements mediated by misalignment at repetitive DNA sequences. Molecular Microbiology 2004, 52, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, M.; et al. Regulation of the replication slippage mutator phenotype by the mismatch repair system. Journal of Bacteriology 2000, 182, 6590–6595. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.C.; et al. Microsatellites within genes: Structure, function, and evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2002, 19, 1451–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, E.; de Lorenzo, V. Engineering multiple genomic deletions in Gram-negative bacteria: Analysis of the multi-resistant antibiotic profile of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environmental Microbiology 2011, 13, 2702–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saradadevi, G.P.; Das, D.; Mangrauthia, S.K.; Mohapatra, S.; Chikkaputtaiah, C.; Roorkiwal, M.; Solanki, M.; Sundaram, R.M.; Chirravuri, N.N.; Sakhare, A.S.; Kota, S.; Varshney, R.K.; Mohannath, G. Genetic, Epigenetic, Genomic and Microbial Approaches to Enhance Salt Tolerance of Plants: A Comprehensive Review. Biology 2021, 10, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bacolla, A.; et al. DNA secondary structure formation and its potential role in genomic instability. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2004, 61, 218–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss, C.D.; Field, D.; Moxon, E.R. The simple sequence contingency loci of Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitidis. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2001, 107, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxon, E.R.; et al. Adaptive evolution of highly mutable loci in pathogenic bacteria. Current Biology 2006, 16, R671–R677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Woude, M.W.; Bäumler, A.J. Phase and antigenic variation in bacteria. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2004, 17, 581–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veening, J.W.; Smits, W.K.; Kuipers, O.P. Bistability, epigenetics, and bet-hedging in bacteria. Annual Review of Microbiology 2008, 62, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odah, M.A.A. Beyond the double helix: Unraveling the intricacies of DNA and RNA networks. Arch. Biol. Life Sci. 2024, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, A.D.; et al. Evaluation of Oxford Nanopore’s MinION sequencing device for microbial whole genome sequencing applications. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 10931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loman, N.J.; Quick, J.; Simpson, J.T. A complete bacterial genome assembled de novo using only nanopore sequencing data. Nature Methods 2015, 12, 733–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; et al. Completing bacterial genome assemblies with multiplex MinION sequencing. Microbial Genomics 2017, 3, e000132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatusova, T.; et al. Prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, 6614–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elcheninov, A.G.; Ugolkov, Y.A.; Elizarov, I.M.; Klyukina, A.A.; Kublanov, I.V.; Sorokin, D.Y. Cellulose metabolism in halo(natrono)archaea: A comparative genomics study. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1112247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, X.; et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals functional diversity of microbial communities in saline-alkaline soils. Environmental Microbiology Reports 2020, 12, 452–460. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; et al. Distribution of stress-response genes and tandem repeats in Pseudomonas fluorescens adapted to desert soil. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 2017, 113, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; et al. Expansion of CA repeats in halotolerant bacteria from hypersaline soils. Microbial Ecology 2015, 69, 729–737. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, S.; et al. Environmental modulation of microsatellite profiles in extremophilic bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2018, 84, e02466–17. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; et al. Bacterial adaptation to heavy metals through short tandem repeat expansion. Ecotoxicology 2019, 28, 1056–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; et al. STR contraction patterns in drought-adapted microbes from arid ecosystems. Journal of Arid Environments 2022, 192, 104602. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Jia, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, W.; Wang, D.; Bai, J. Seasonality and assembly of soil microbial communities in coastal salt marshes invaded by a perennial grass. J Environ Manage. 2023, 331, 117247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, H.A.; et al. Influence of the spacing between the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and the initiation codon on the efficiency of translation of mRNA in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Research 1983, 11, 737–750. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, J.; et al. STR-mediated regulation in low-energy soil microenvironments. Microbial Systems Biology 2020, 5, e00089–19. [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos-López, M.A.; Arroyo-Becerra, A.; Quintero-Jiménez, A.; Iturriaga, G. Biotechnological Advances to Improve Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crops. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Acar, M.; Mettetal, J.T.; van Oudenaarden, A. Stochastic switching as a survival strategy in fluctuating environments. Nature Genetics 2008, 40, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, Y.; et al. Heat-shock-induced STR expansion and gene expression modulation. Molecular Cell 2010, 39, 885–892. [Google Scholar]

- McMurrough, T.A.; et al. Genome-wide profiling of STRs in stress-tolerant bacterial strains. Environmental Microbiology 2014, 16, 1212–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Dynamic variation of STRs under pollutant exposure in soil bacteria. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 651, 2317–2325. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, M.; Leung, P.M.; Shelley, G.; Jirapanjawat, T.; Nauer, P.A.; Van Goethem, M.W.; Bay, S.K.; Islam, Z.F.; Jordaan, K.; Vikram, S.; Chown, S.L.; Hogg, I.D.; Makhalanyane, T.P.; Grinter, R.; Cowan, D.A.; Greening, C. Multiple energy sources and metabolic strategies sustain microbial diversity in Antarctic desert soils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2021, 118, e2025322118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stanton, B.C.; et al. Genomic STR switches for whole-cell biosensing. Nature Chemical Biology 2014, 10, 555–561. [Google Scholar]

- Odah, M.A.A. Exploring the role of circulating cell-free DNA in disease diagnosis and therapy. Afr. Res. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cheng, L.; Nian, H.; Jin, J.; Lian, T. Linking plant functional genes to rhizosphere microbes: A review. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023, 21, 902–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Choudhary, V.; et al. Genetic memory systems using STRs for environmental data logging. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 4782. [Google Scholar]

- Treangen, T.J.; et al. Repetitive DNA and next-generation sequencing. Nature Reviews Genetics 2011, 13, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odah, M.A.A. Exploring the dynamic 3D DNA structures in genomics. Afr. Res. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 1, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: A program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 1999, 27, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.; et al. Phobos: A tool for repeat detection in eukaryotic and prokaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1250–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Novák, P.; et al. RepeatExplorer: A Galaxy-based web server for genome-wide characterization of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Bioinformatics 2010, 29, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, T.; et al. Genome-wide profiling of STR variation using HipSTR. Nature Methods 2017, 14, 590–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odah, M.A.A. Unveiling the potential of quantum dots in revolutionizing stem cell tracking for regenerative medicine. Afr. Res. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 1, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahlo, M.; et al. STRique: Real-time analysis of nanopore sequencing for STR variation. Genome Biology 2018, 19, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel, R.E.; et al. NanoSTR: Nanopore-based STR analysis pipeline. Nature Biotechnology 2021, 39, 773–780. [Google Scholar]

- De Bolle, X.; et al. The complexity of simple sequence repeats in bacterial adaptation. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2000, 107, 657–662. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, D.W.; et al. DNA repeats and phase-variable expression in Neisseria. Microbiology 1999, 145, 927–935. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Doudna, J.A. CRISPR–Cas9 structures and mechanisms. Annual Review of Biophysics 2017, 46, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; et al. STR–gene interaction databases: Current gaps and future perspectives. Trends in Genetics 2021, 37, 981–994. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, L.A.; et al. Comprehensive transposon mutant library analysis reveals gene networks in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Bacteriology 2011, 193, 4207–4215. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, A.N.; et al. Nanopore sequencing enables high-resolution detection of low-abundance STRs. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 2674. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; et al. Real-time environmental monitoring using STRique in soil microbiomes. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 887422. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; et al. Ecological correlates of STR expansions in saline habitats. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2021, 97, fiab014. [Google Scholar]

- Good, B.H.; et al. The dynamics of molecular evolution over 60,000 generations. Nature 2017, 551, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.W.; et al. CRISPR-based STR editing for regulatory region analysis. Nature Biotechnology 2014, 32, 530–536. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, L.A.; et al. CRISPR-mediated modular control of gene expression. Cell 2013, 154, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tringe, S.G.; et al. Comparative metagenomics of microbial communities. Science 2005, 308, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notomi, T.; et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Research 2000, 28, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).