Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Neural Network Planner for Fixed-Wing UAVs: We develop a neural-network-based path planner capable of generating feasible flight trajectories in real time. The neural network is trained offline and rapidly predicts trajectories, thus eliminating the need for iterative online optimization.

- Incorporation of Terminal Roll-Angle Constraints: Our approach explicitly incorporates terminal roll-angle constraints into the path-planning process. Unlike previous approaches that may overlook terminal attitude constraints, our method ensures UAVs reliably attain the desired roll angle upon arrival at the target location.

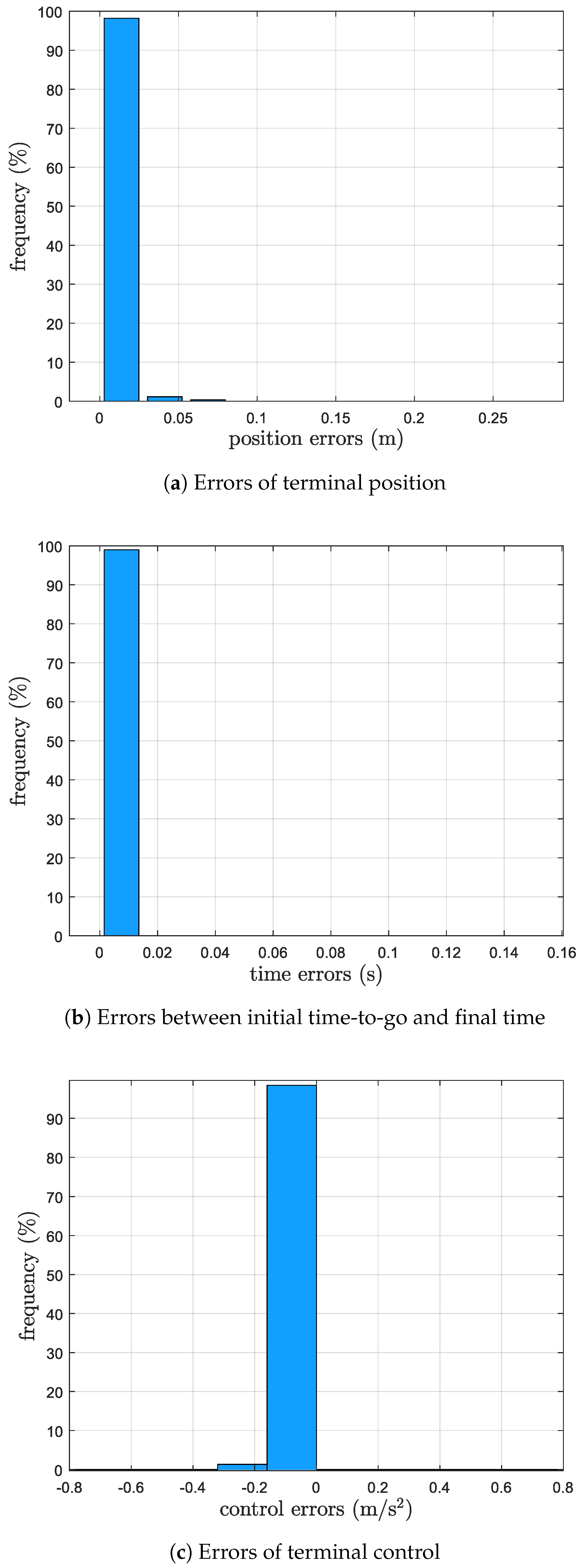

- Robust Performance Validation: The proposed method has been validated through extensive Monte Carlo simulations involving thousands of randomized initial conditions. Simulation results demonstrate that the neural network-based planner consistently produces feasible and accurate trajectories, satisfying terminal roll constraints in all tested scenarios. The results demonstrate the robustness and reliability of the proposed framework for real-time fixed-wing UAV path planning.

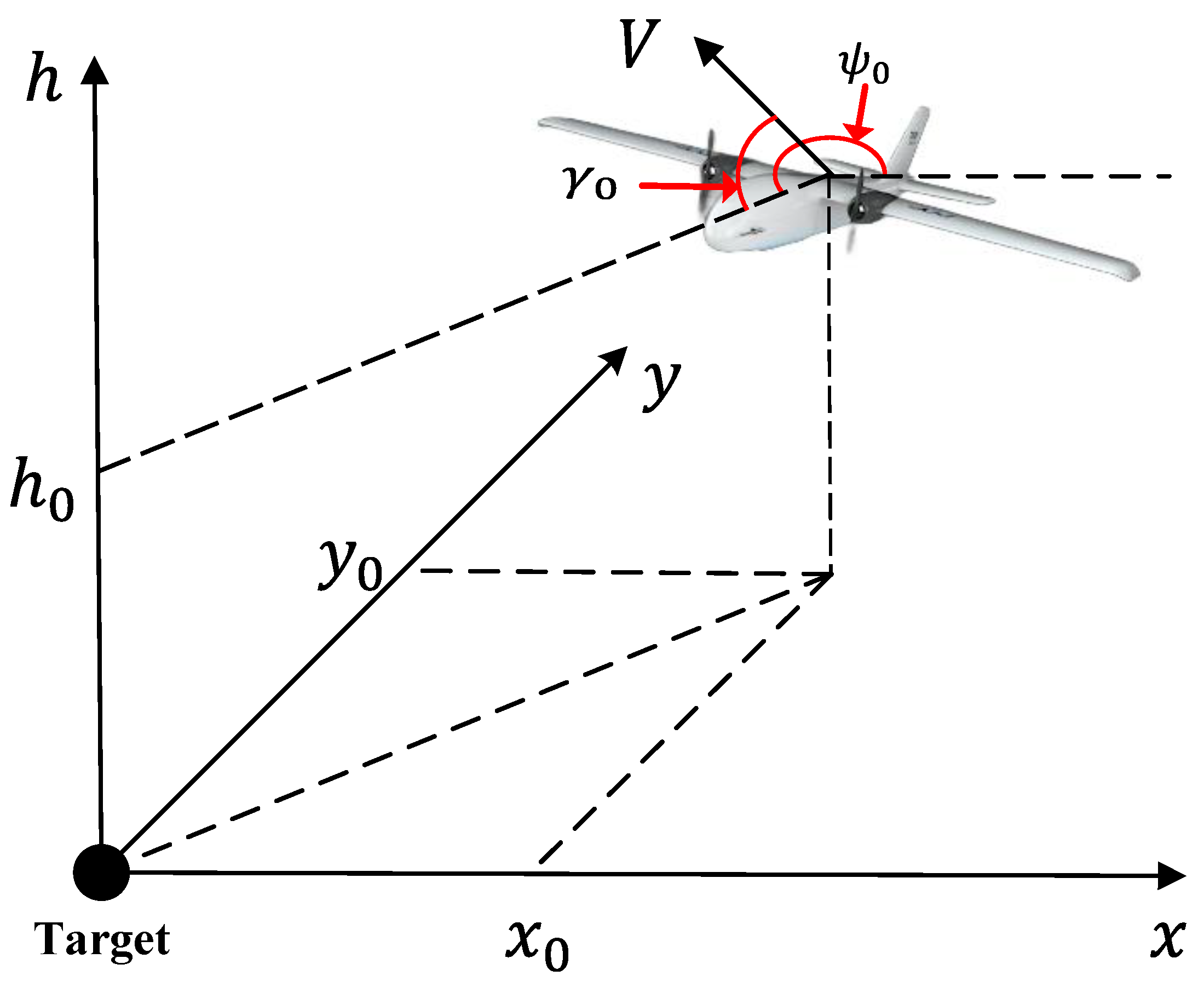

2. Problem Formulation

2.1. Kinematics

2.2. Optimal Control Problem

3. Characterization of Optimal Solutions

3.1. Necessary Conditions for Optimality

3.2. Parameterization of Extremal Trajecories

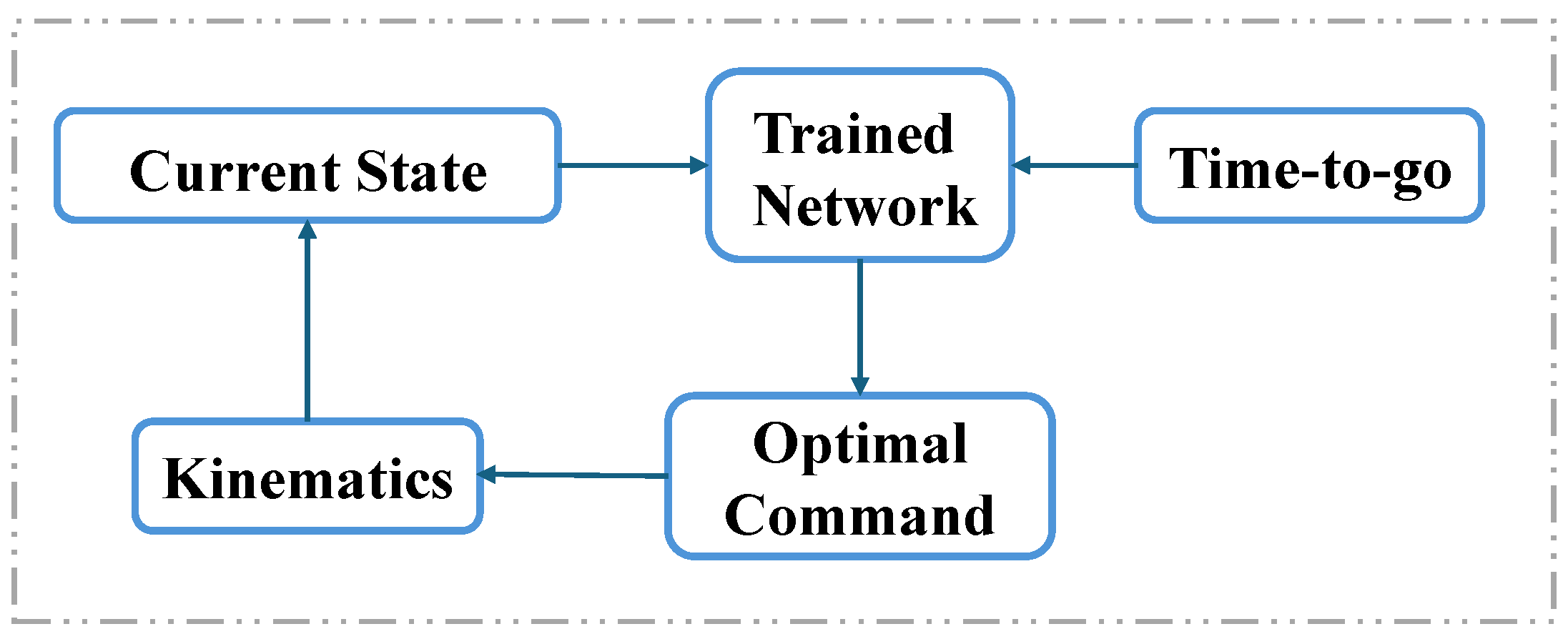

4. Real-Time Solutions via Neural Networks

4.1. Scheme for Real-Time Solution via Neural Network

4.2. Dataset Generation for Training Neural Network

| Algorithm 1 (Dataset Generation Procedure). Input: Positive values , T, and step size |

| Output: Dataset |

| Initialize: (empty dataset) |

| for to step do |

| for to step do |

| for to step do |

| Set |

| Integrate the system using Eq. (13) with the parameter |

| Extract the trajectory and control for |

| if for then |

| Add to dataset |

| end if |

| end for |

| end for |

| end for |

| Return |

5. Numerical Simulations

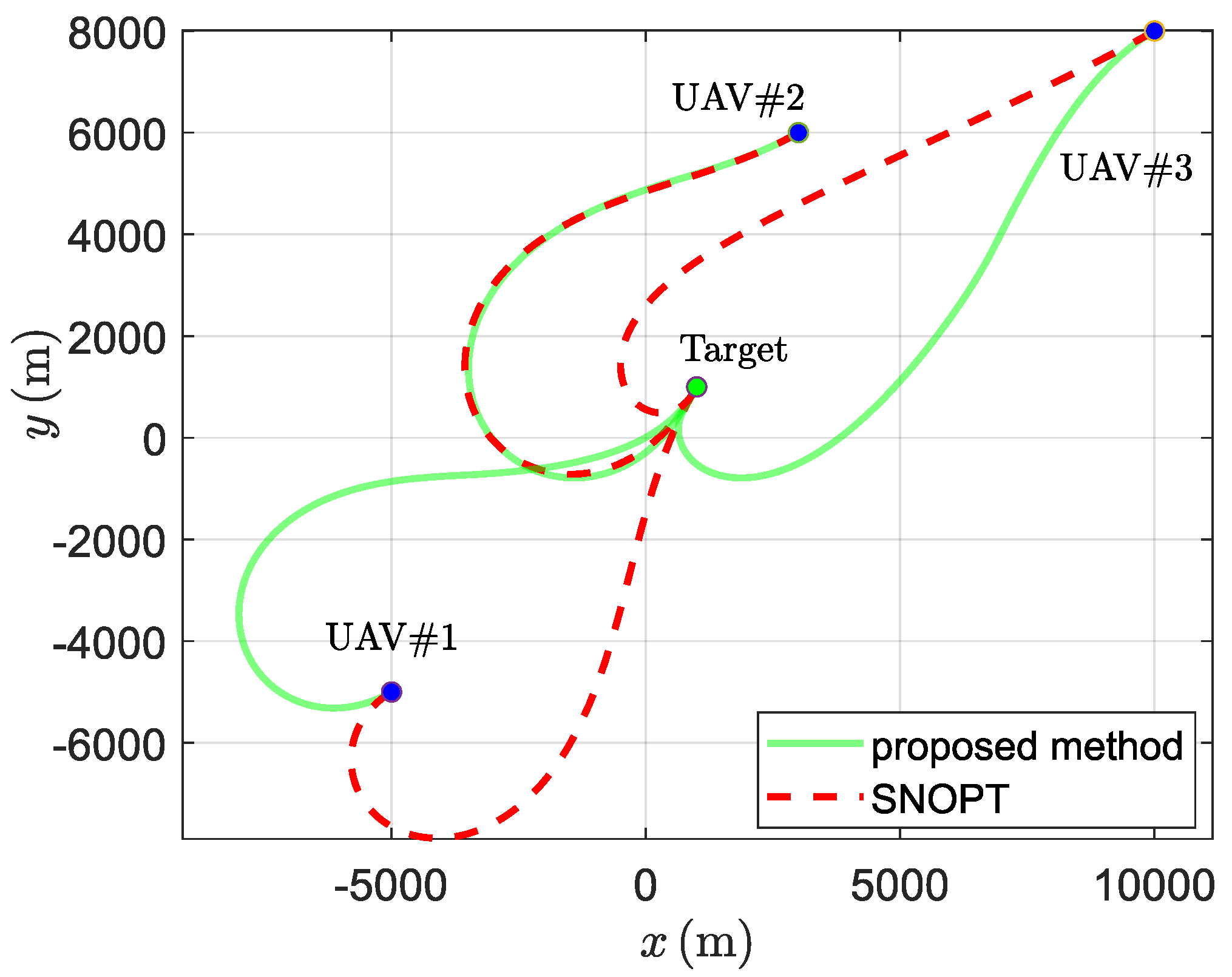

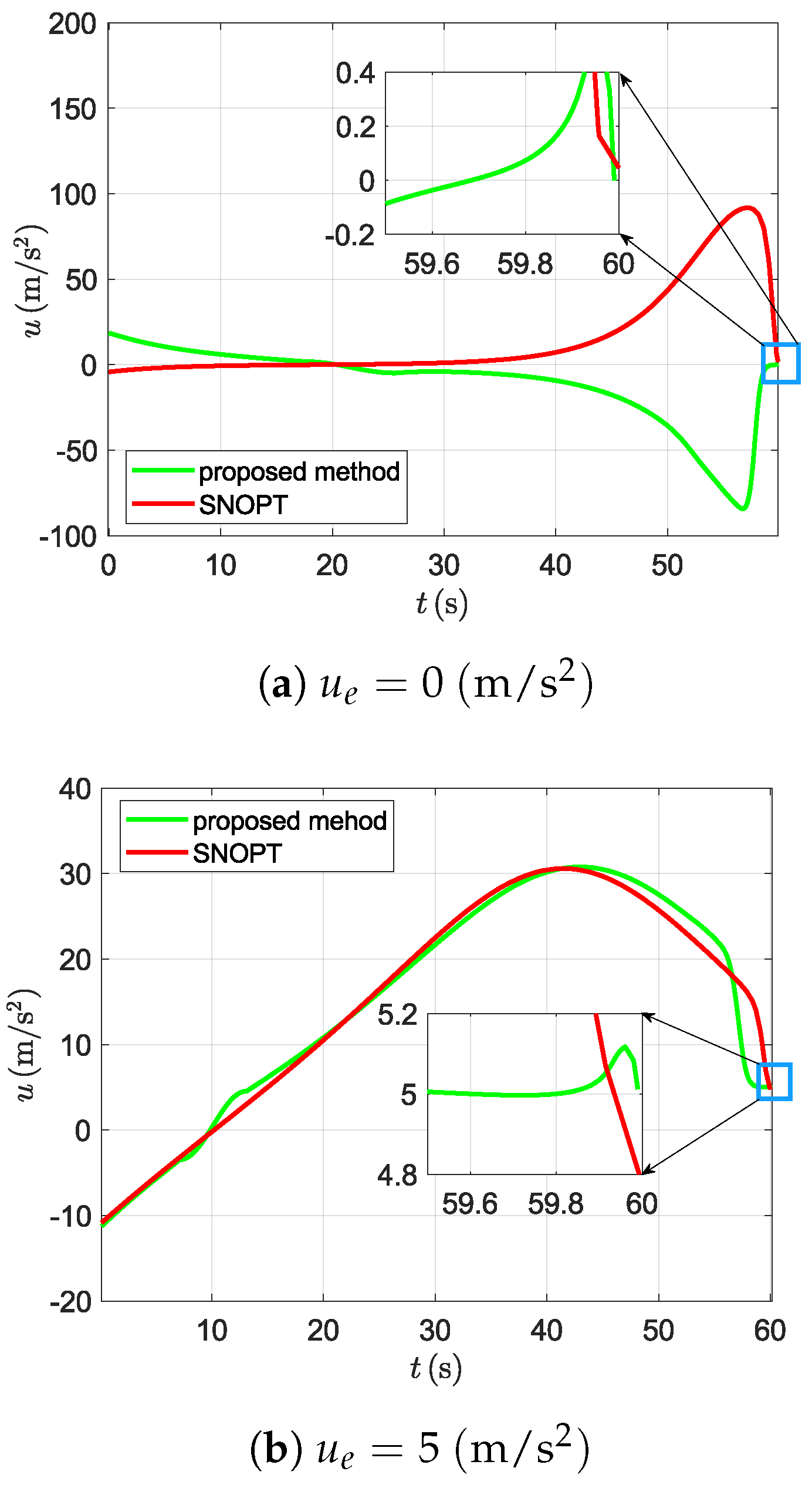

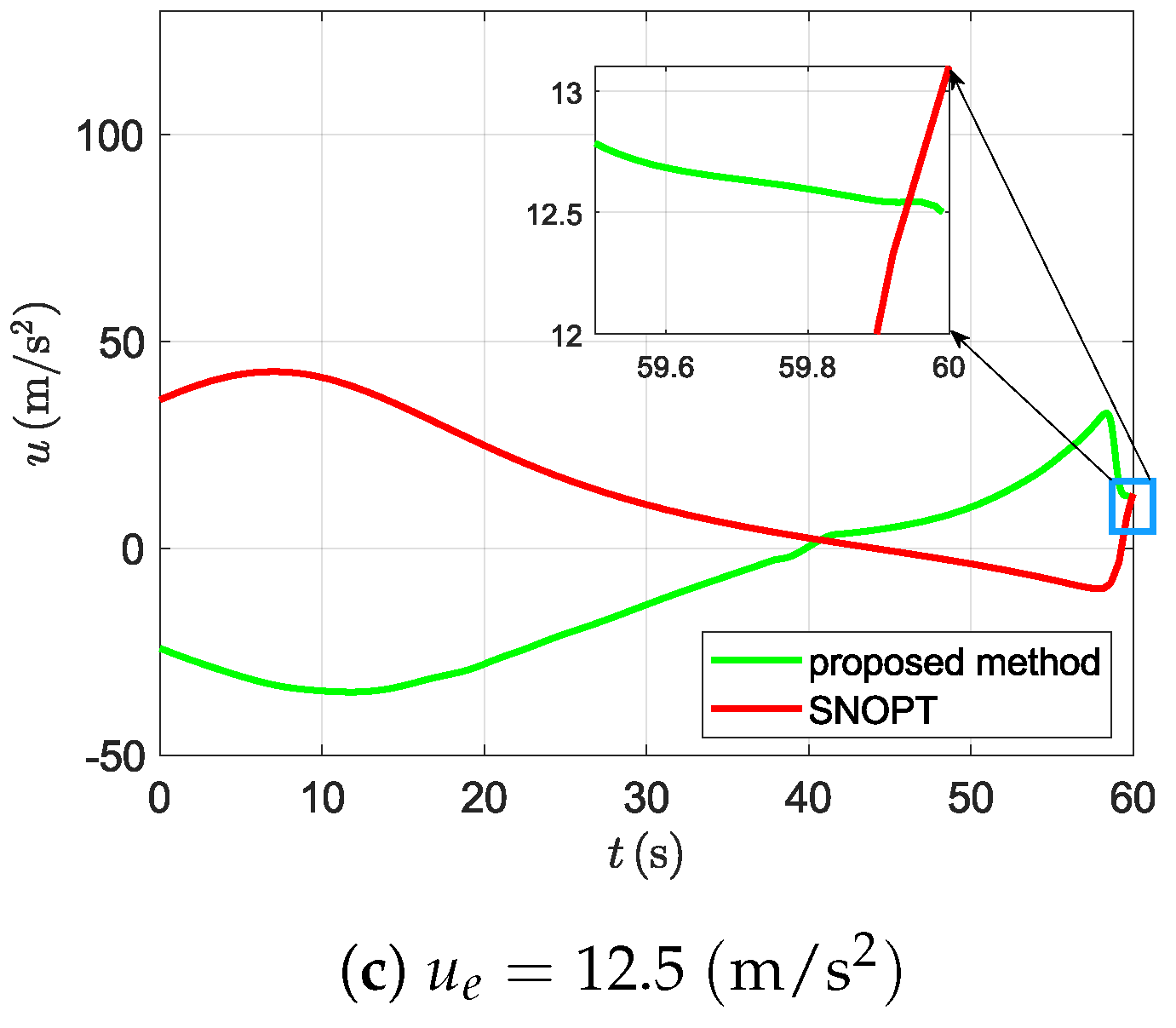

5.1. Comparisions with Optimization Methods

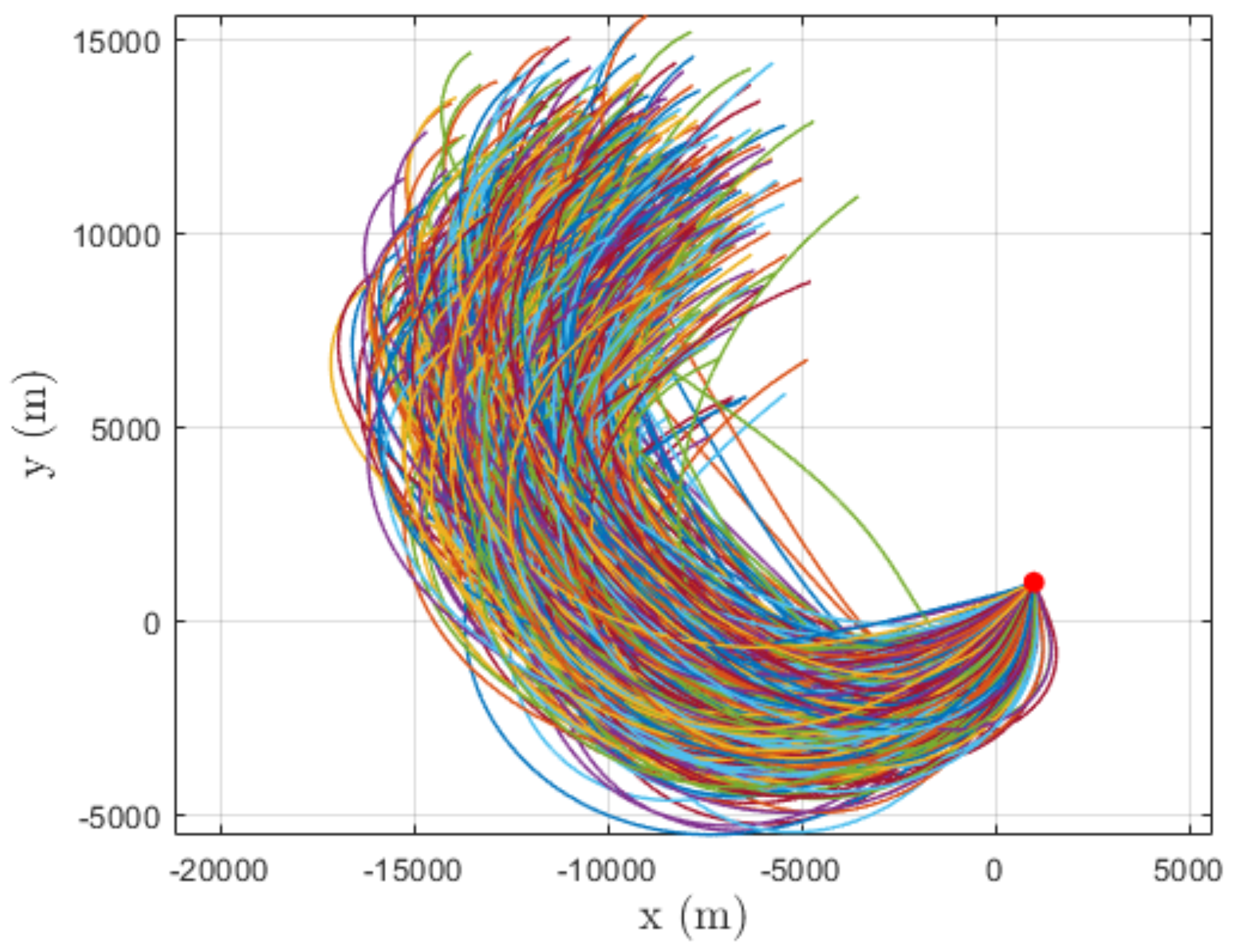

5.2. Monte Carlo Simulations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Malamiri, H.R.G.; Aliabad, F.A.; Shojaei, S.; Morad, M.; Band, S.S. A study on the use of UAV images to improve the separation accuracy of agricultural land areas. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2021, 184, 106079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbari, V.; Gupta, S.; Verma, O.P. Dynamic motion planning for aerial surveillance on a fixed-wing UAV. In Proceedings of the 2017 international conference on unmanned aircraft systems (ICUAS). IEEE, 2017, pp. 488–497.

- Anand, T.P.; Abishek, K.; Kailash, R.K.; Nithiyanantham, K. Development and automation of fixed wing UAV for reconnaissance mission with FPV capability. INCAS Bulletin 2022, 14, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujit, P.; Saripalli, S.; Sousa, J.B. Unmanned aerial vehicle path following: A survey and analysis of algorithms for fixed-wing unmanned aerial vehicless. IEEE Control Systems Magazine 2014, 34, 42–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ghambari, S.; Golabi, M.; Jourdan, L.; Lepagnot, J.; Idoumghar, L. UAV path planning techniques: a survey. RAIRO-Operations Research 2024, 58, 2951–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Chang, Z.; Yan, Q. Path-following control of small fixed-wing UAVs under wind disturbance. Drones 2023, 7, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Wang, Y. Nonlinear adaptive line-of-sight path following control of unmanned aerial vehicles considering sideslip amendment and system constraints. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2020, 2020, 4535698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Tong, M.; Wang, Q.; Song, W.; Ying, H. Curved-line path-following control of fixed-wing unmanned aerial vehicles using a robust disturbance-estimator-based predictive control approach. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 11577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R.; Barber, D.B.; McLain, T.W.; Beard, R.W. Vector field path following for miniature air vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2007, 23, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, J.P.; Clem, G. Vector field UAV guidance for path following and obstacle avoidance with minimal deviation. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics 2019, 42, 1848–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, F.L.L.; Da Silva, J.D.S. A Dijkstra algorithm for fixed-wing UAV motion planning based on terrain elevation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Artificial Intelligence–SBIA 2010: 20th Brazilian Symposium on Artificial Intelligence, São Bernardo do Campo, Brazil, October 23-28, 2010. Proceedings 20. Springer, 2010, pp. 213–222.

- Babel, L. Curvature-constrained traveling salesman tours for aerial surveillance in scenarios with obstacles. European Journal of Operational Research 2017, 262, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Sukkarieh, S. Real-time continuous curvature path planning of UAVs in cluttered environments. In Proceedings of the 2008 5th international symposium on mechatronics and its applications. IEEE, 2008, pp. 1–6.

- Lee, D.; Shim, D.H. RRT-based path planning for fixed-wing UAVs with arrival time and approach direction constraints. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS). IEEE, 2014, pp. 317–328.

- Xu, J.; Shi, M.; Tang, F.; Sun, X.; Yue, J.; Lin, B.; Qin, K. Dubins-A*: a new global path planning scheme for fixed-wing UAV with irregular obstacles avoidance. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Electronics Technology (ICET). IEEE, 2024, pp. 636–641.

- Airlangga, G.; et al. Advancing UAV path planning system: a software pattern language for dynamic environments. Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro 2023, 5, 475–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifianto, O.; Farhood, M. Optimal control of fixed-wing uavs along real-time trajectories. In Proceedings of the Dynamic Systems and Control Conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2012, Vol. 45295, pp. 205–214.

- Din, A.F.U.; Mir, I.; Gul, F.; Mir, S.; Alhady, S.S.N.; Al Nasar, M.R.; Alkhazaleh, H.A.; Abualigah, L. Robust flight control system design of a fixed wing UAV using optimal dynamic programming. Soft Computing 2023, 27, 3053–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marinis, A.; Iavernaro, F.; Mazzia, F. A minimum-time obstacle-avoidance path planning algorithm for unmanned aerial vehicles. Numerical Algorithms 2022, 89, 1639–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkan, M.; Rizvi, M.M.; Chowdhury, M.A.M. Optimal path planning of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) for targets touring: Geometric and arc parameterization approaches. Plos one 2022, 17, e0276105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Yao, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, K. Optimal energy consumption path planning for unmanned aerial vehicles based on improved particle swarm optimization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.K.; Moncton, M.; Choi, H.L.; Frew, E. Path planning in 3D with motion primitives for wind energy-harvesting fixed-wing aircraft. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.10915 2023.

- Techy, L.; Woolsey, C.A. Minimum-time path planning for unmanned aerial vehicles in steady uniform winds. Journal of guidance, control, and dynamics 2009, 32, 1736–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, J.T. Survey of numerical methods for trajectory optimization. Journal of guidance, control, and dynamics 1998, 21, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.F.; Schmidt, E.M.; Geiger, B.R.; DeAngelo, M.P. Neural network-based trajectory optimization for unmanned aerial vehicles. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics 2012, 35, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P.E.; Murray, W.; Saunders, M.A. SNOPT: An SQP algorithm for large-scale constrained optimization. SIAM review 2005, 47, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, T.; Stölzle, M.; Turricelli, E.; Achermann, F.; Lawrance, N.; Siegwart, R.; Chung, J.J. Learn to path: using neural networks to predict Dubins path characteristics for aerial vehicles in wind. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1073–1079.

- Airlangga, G.; Bata, J.; Nugroho, O.I.A.; Sugianto, L.F. Neural network architectures for UAV path planning: a comparative study with A* algorithm as benchmark. International Journal of Robotics and Control Systems 2025, 5, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Pan, X.; Wang, T.; Chen, G. UAV path planning based on deep reinforcement learning. In Artificial Intelligence for Robotics and Autonomous Systems Applications; Springer, 2023; pp. 27–65.

- Li, J.; Liu, Y. Deep reinforcement learning based adaptive real-time path planning for UAV. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Dependable Systems and Their Applications (DSA). IEEE, 2021, pp. 522–530.

- Babel, L. Online flight path planning with flight time constraints for fixed-wing UAVs in dynamic environments. International journal of intelligent unmanned systems 2022, 10, 416–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, T. Energy minimization for fixed-wing UAV assisted full-duplex relaying with bank angle constraint. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2023, 12, 1199–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitz, L.A. Derivation of a point-mass aircraft model used for fast-time simulation. MITRE Corporation 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Chen, Z.; Shao, X.; Wang, K. Nonlinear optimal guidance with constraints on impact time and impact angle. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.04707 2024.

- Pontryagin, L.S. Mathematical theory of optimal processes; Routledge, 2018.

- Chen, Z.; Caillau, J.B.; Chitour, Y. L1-minimization for mechanical systems. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization 2016, 54, 1245–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Shao, X. Nonlinear optimal guidance for intercepting stationary targets with impact-time constraints. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics 2022, 45, 1614–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial Conditions | V | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).