Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivations

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Contribution

- -

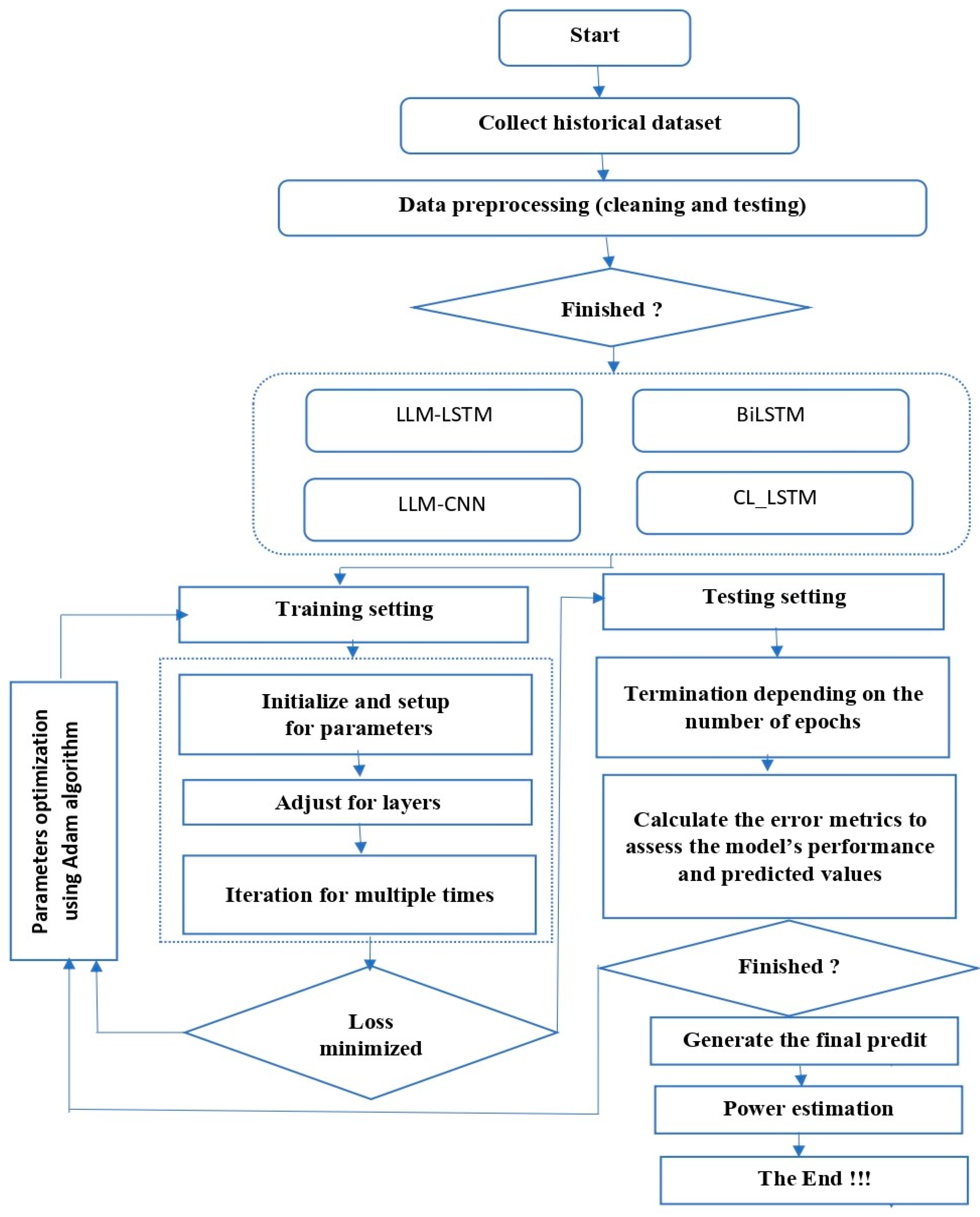

- Development of two hybrid deep learning models (LLM-LSTM and LLM-CNN) that integrate the LLM and LSTM methods, and CNN using the Adam optimization algorithm;

- -

- Comparison of proposed LLM-LSTM and LLM-CNN models with the hybrid methods already in the literature review, namely BiLSTM and CL-LSTM;

- -

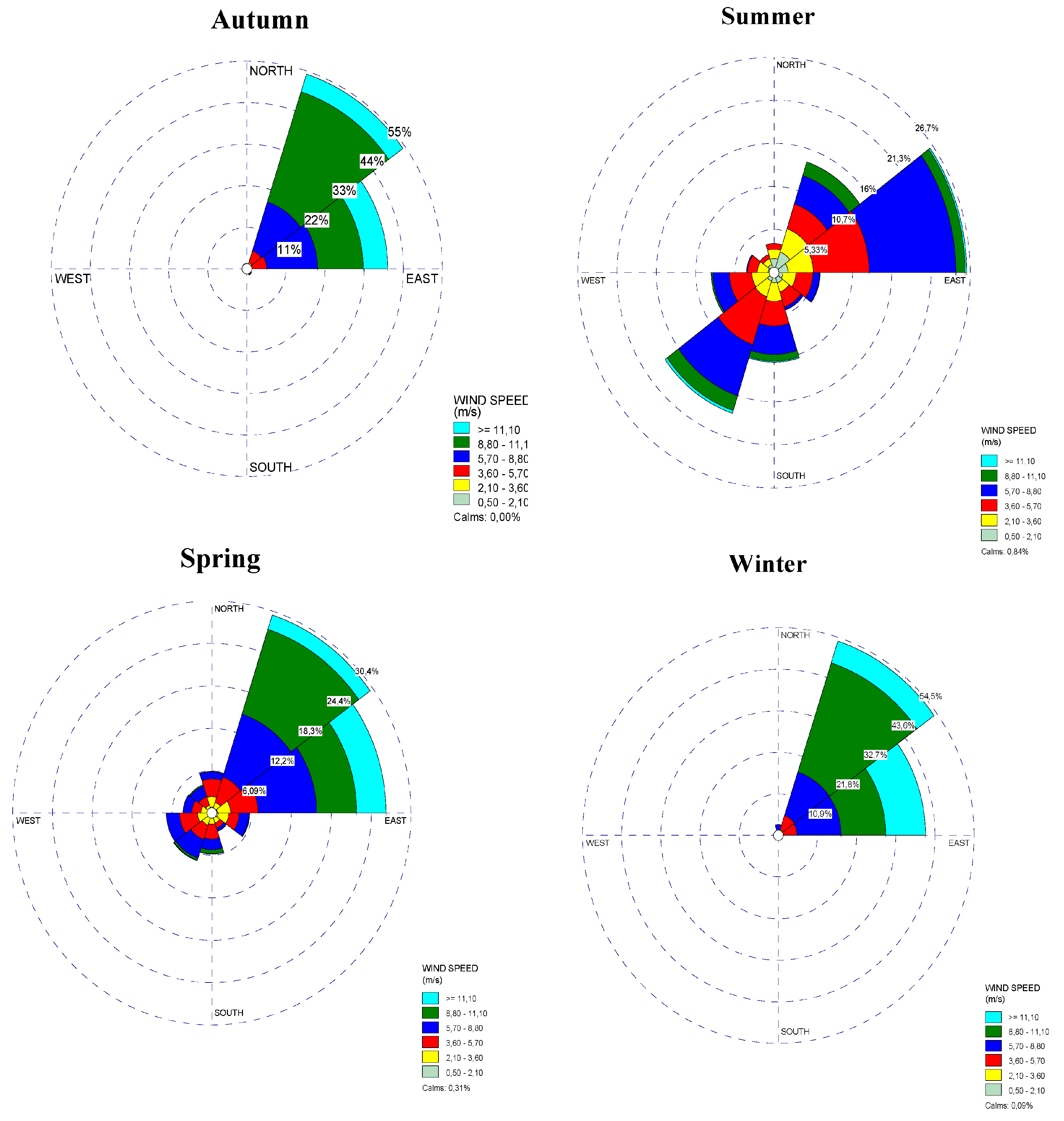

- Determination of wind direction during different seasons of the year;

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Materials

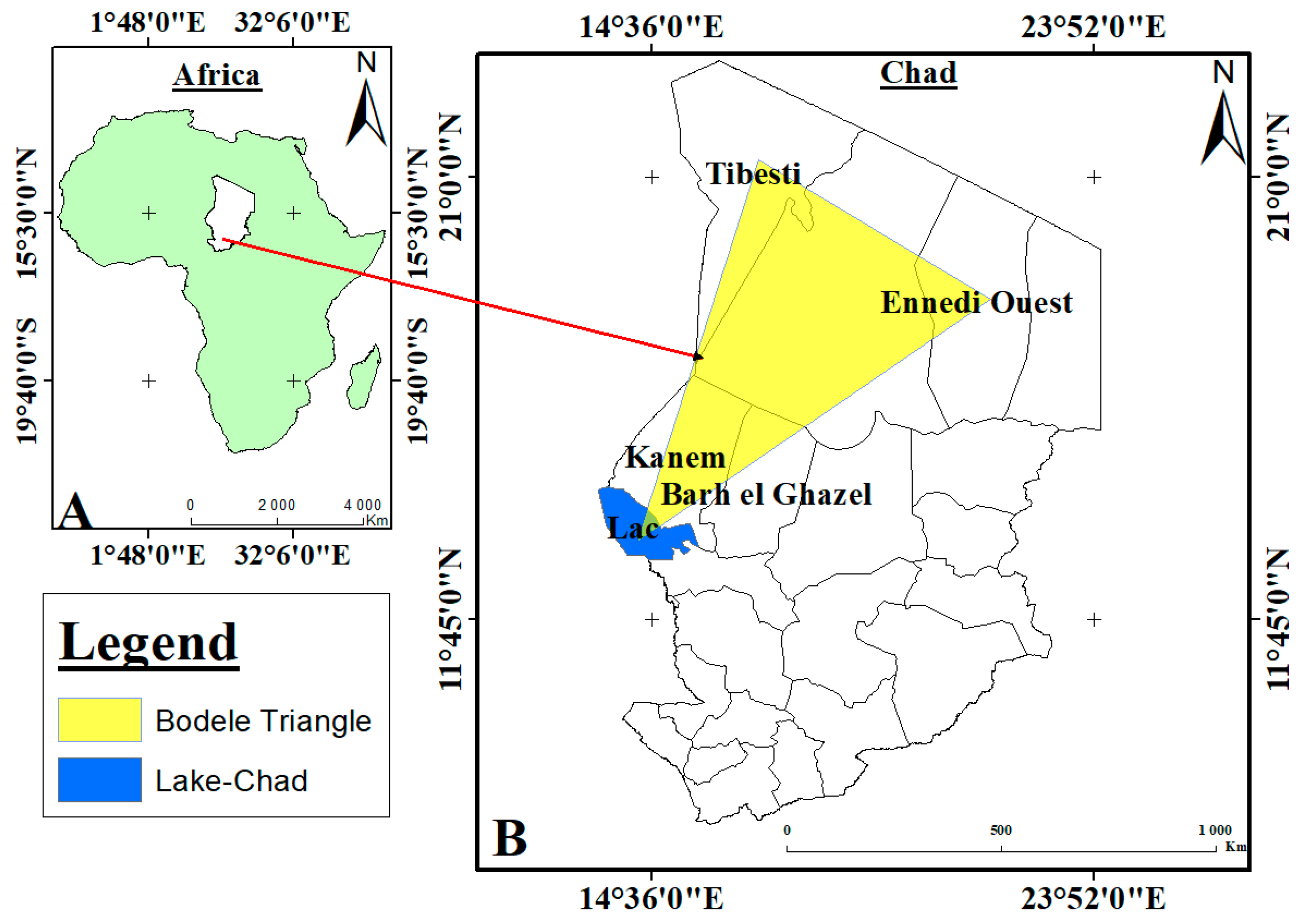

2.1.1. Presentation of Study Sites

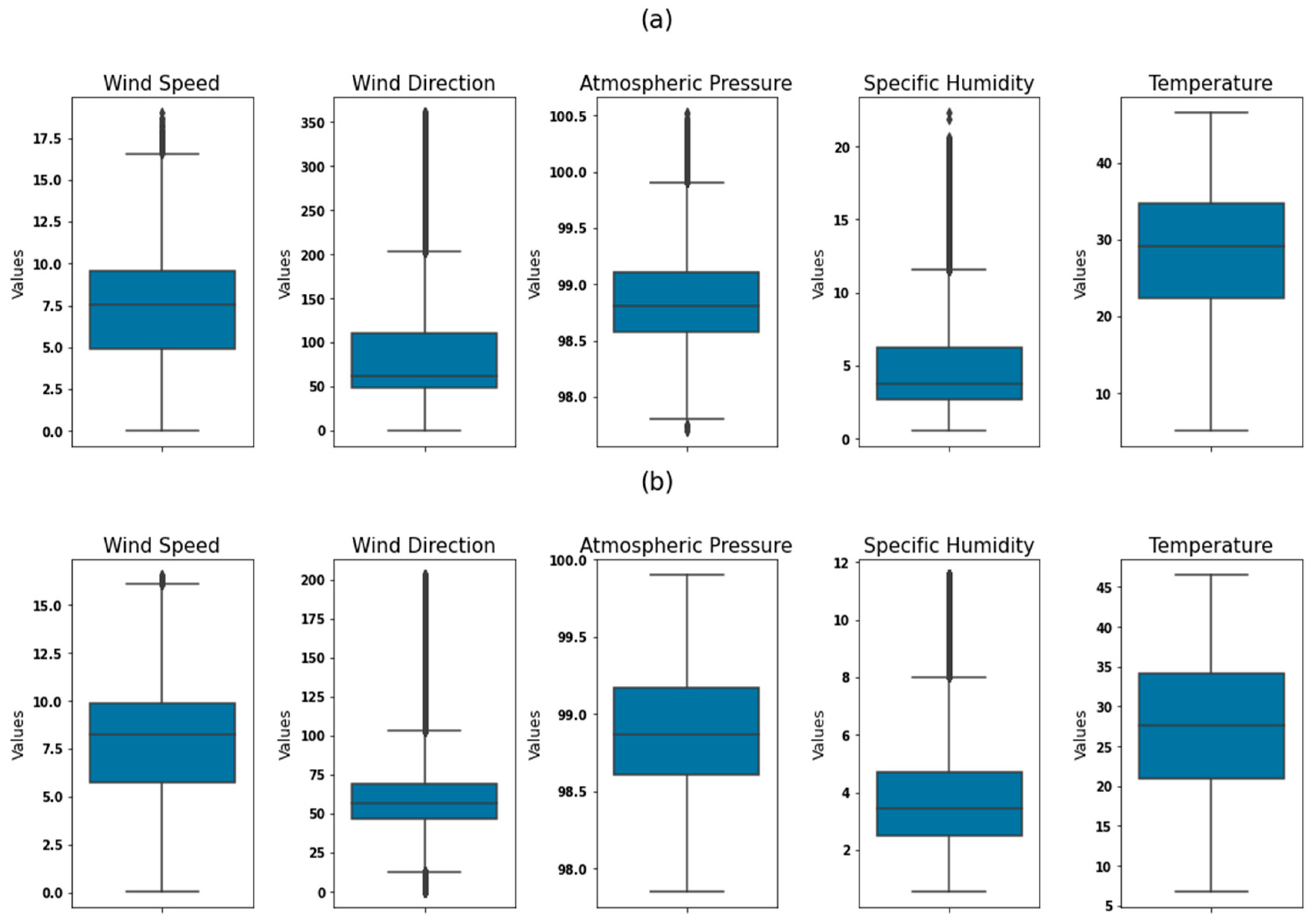

2.1.2. Processing of Variables Used

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Determination of Input Variables and Normalizations

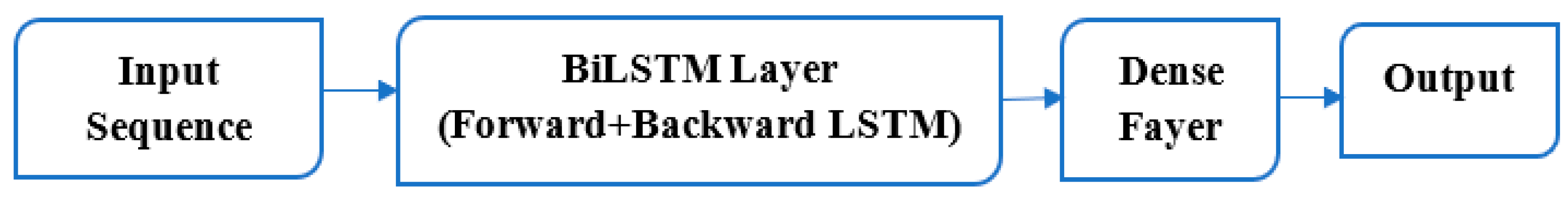

2.2.2. The Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) Model

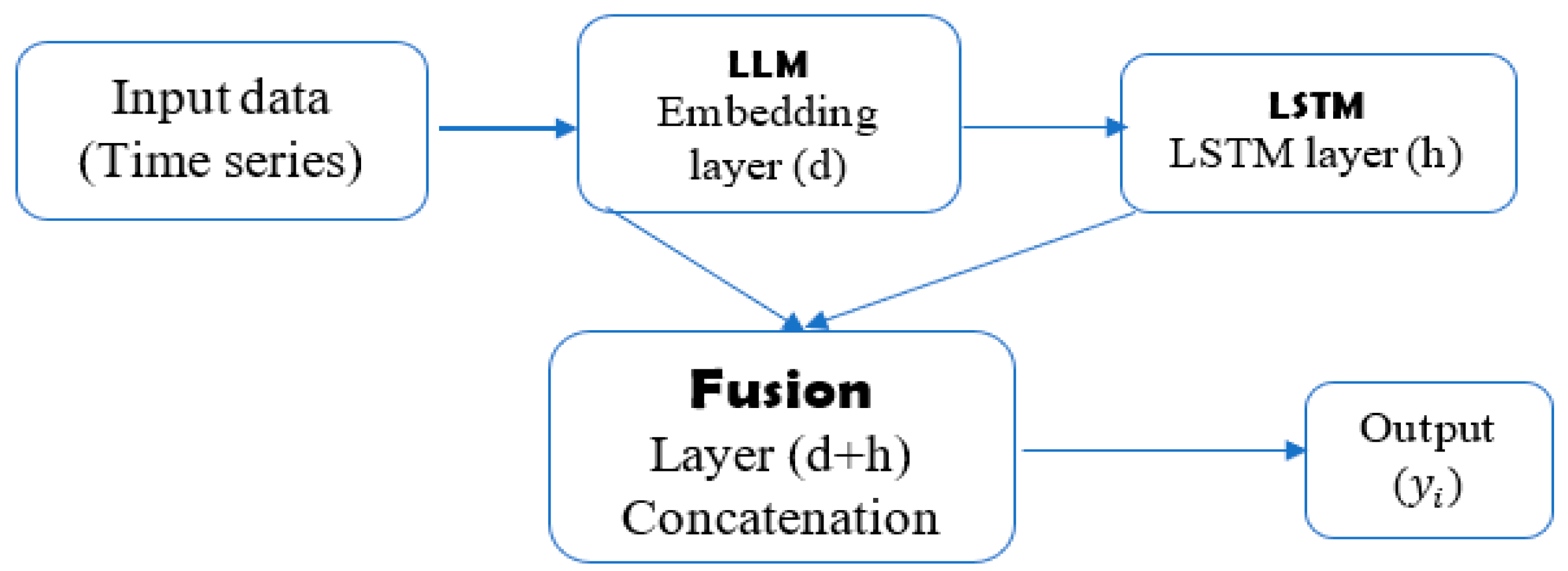

2.2.3. Large Language Memory LSTM Model (LLM-LSTM)

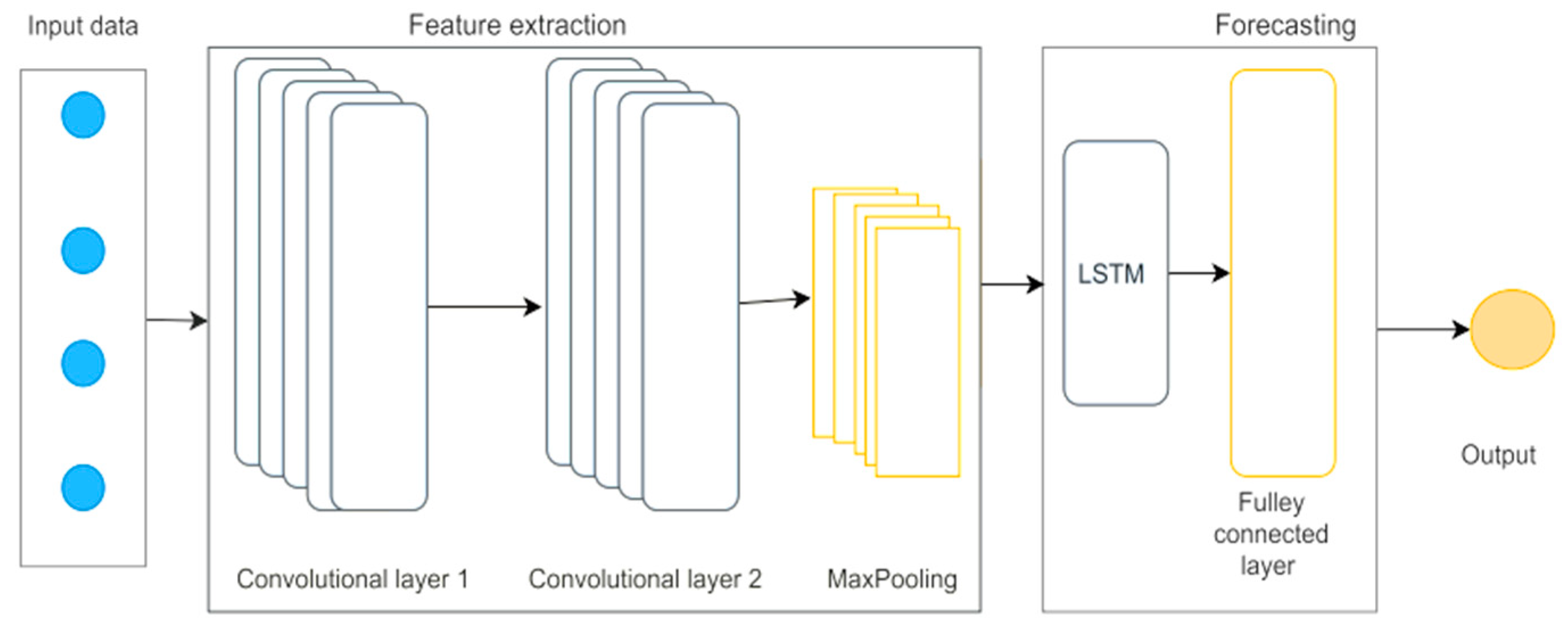

2.2.4. The Convolutional Neural Networks and Long Short-Term Memory (CL-LSTM) Model

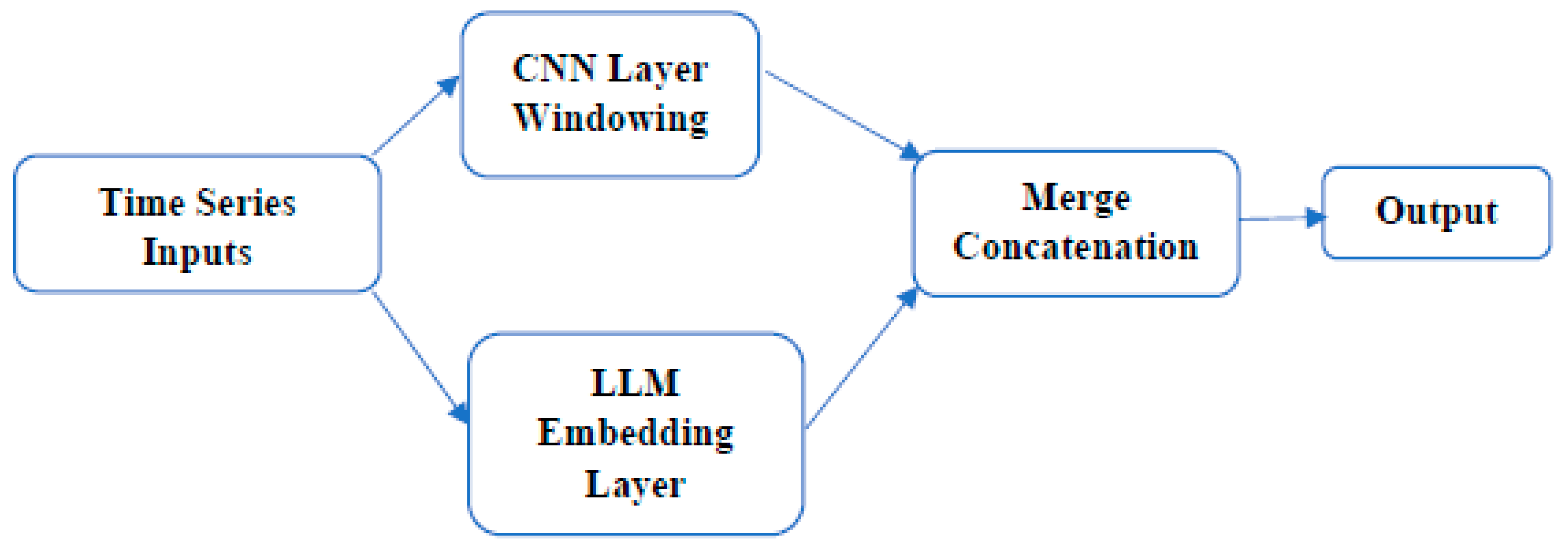

2.2.5. The Large Language Memory Convolutional Network (LLM-CNN) Model

2.2.6. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Different Models

2.2.7. Model Performance Evaluation

2.2.8. Wind Speed Modeling

2.2.8.1. Weibull Parameters

2.2.8.2. Extrapolation of Wind Speed as a Function of Height

2.2.8.3. Extrapolation of Weibull Parameters as a Function of Height

2.2.8.4. Power Density of a Wind Turbine

2.2.8.5. Wind Turbine Power Calculation

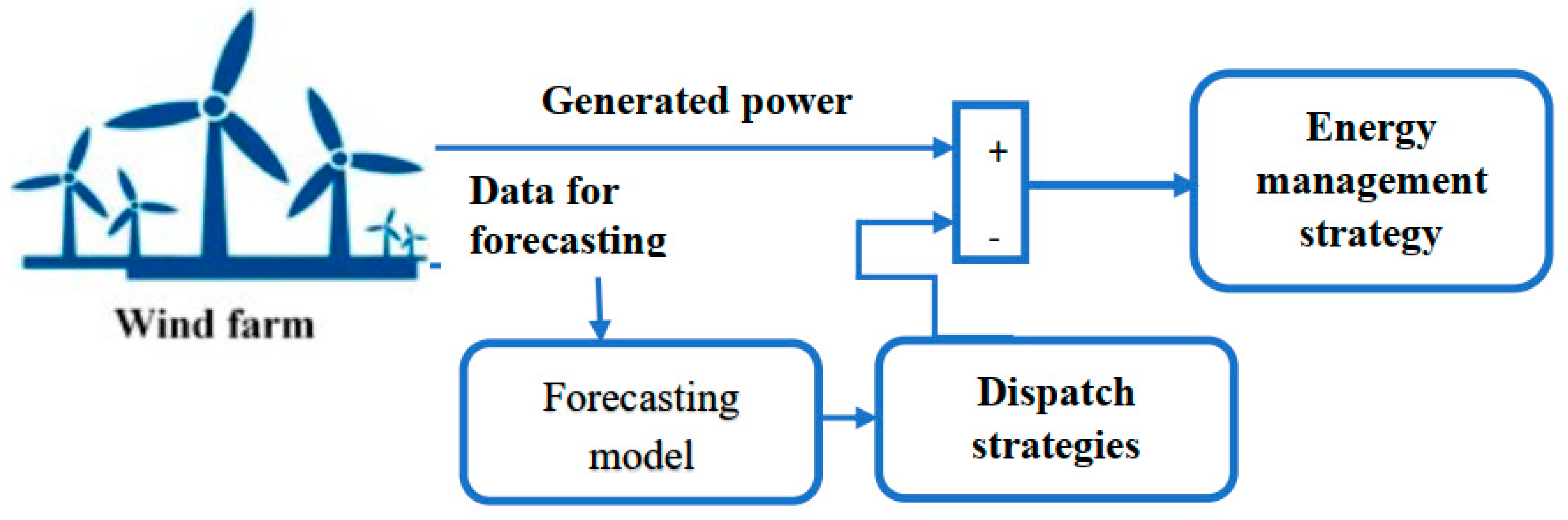

2.2.8.6. Balancing Production with Demand

2.2.8.7. Management of High and Low Production Periods

2.2.8.8. Wind Turbine Reliability Analysis

| Manufacturer | Gamesa |

|---|---|

| Rated power | 5 MW |

| Starting speed | 4 m/s |

| Nominal wind speed | 14.0 m/s |

| Disconnection speed | 27. 0 m/s |

| Hub height | 81 à 120 m |

| Rotor diameter | 128.0 m |

| Area swept by blades | 7 854 m² |

3. Validation of Results with Similar Hybrid Models

4. Results and Discussion

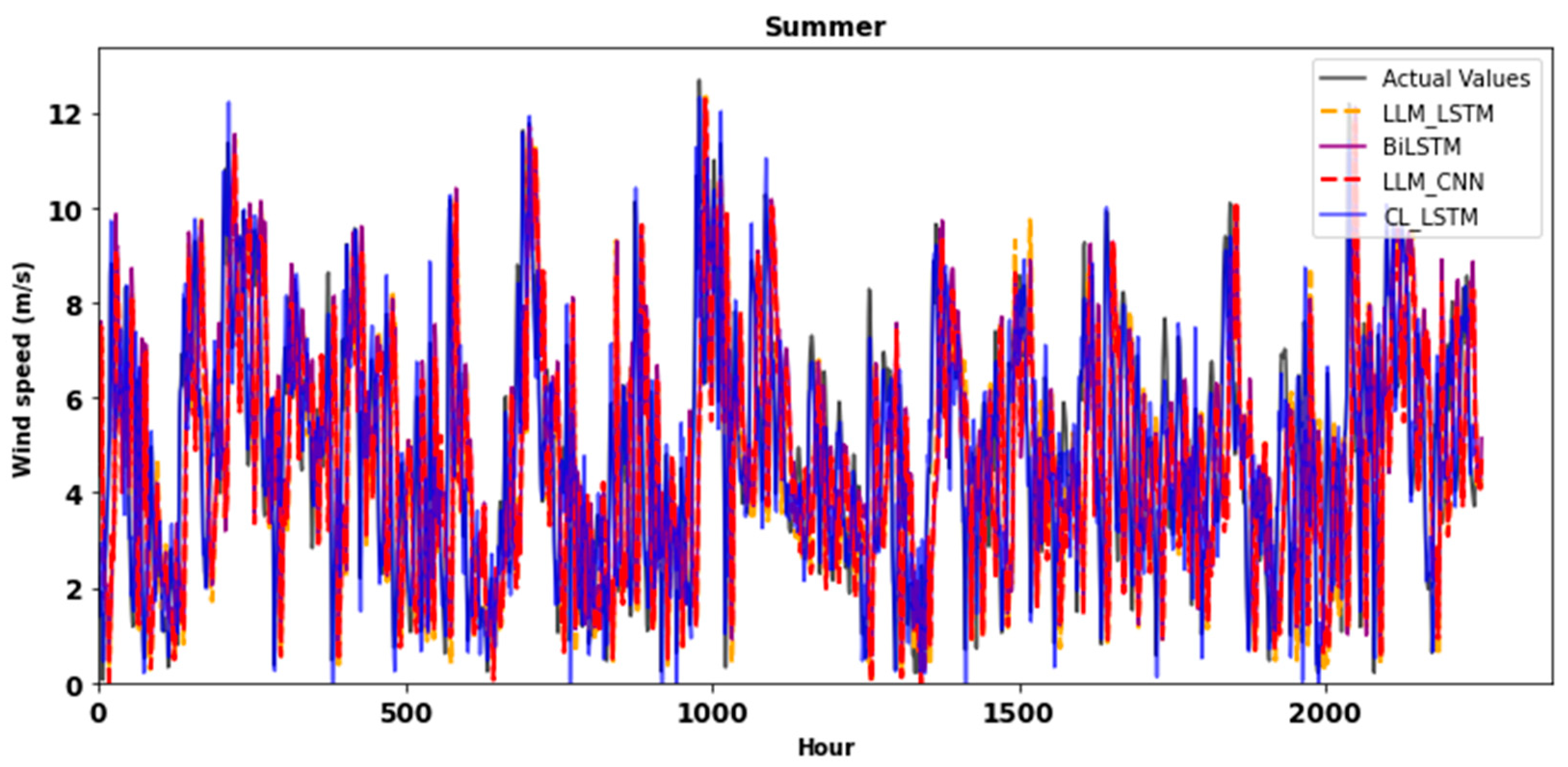

4.1. Presentation of Forecast Curves for Different Seasons

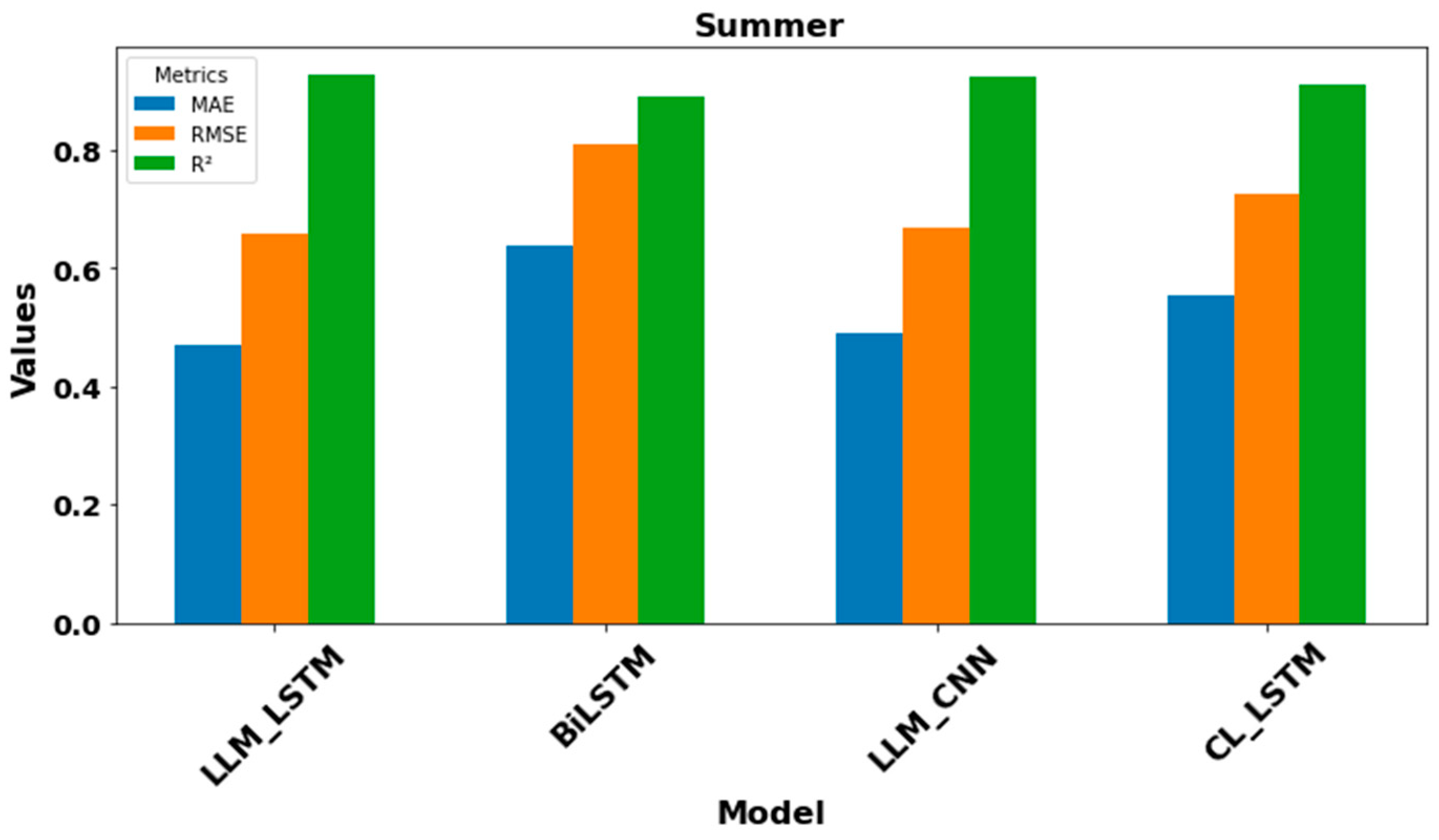

4.2. Presentation of Performance Statistics Values

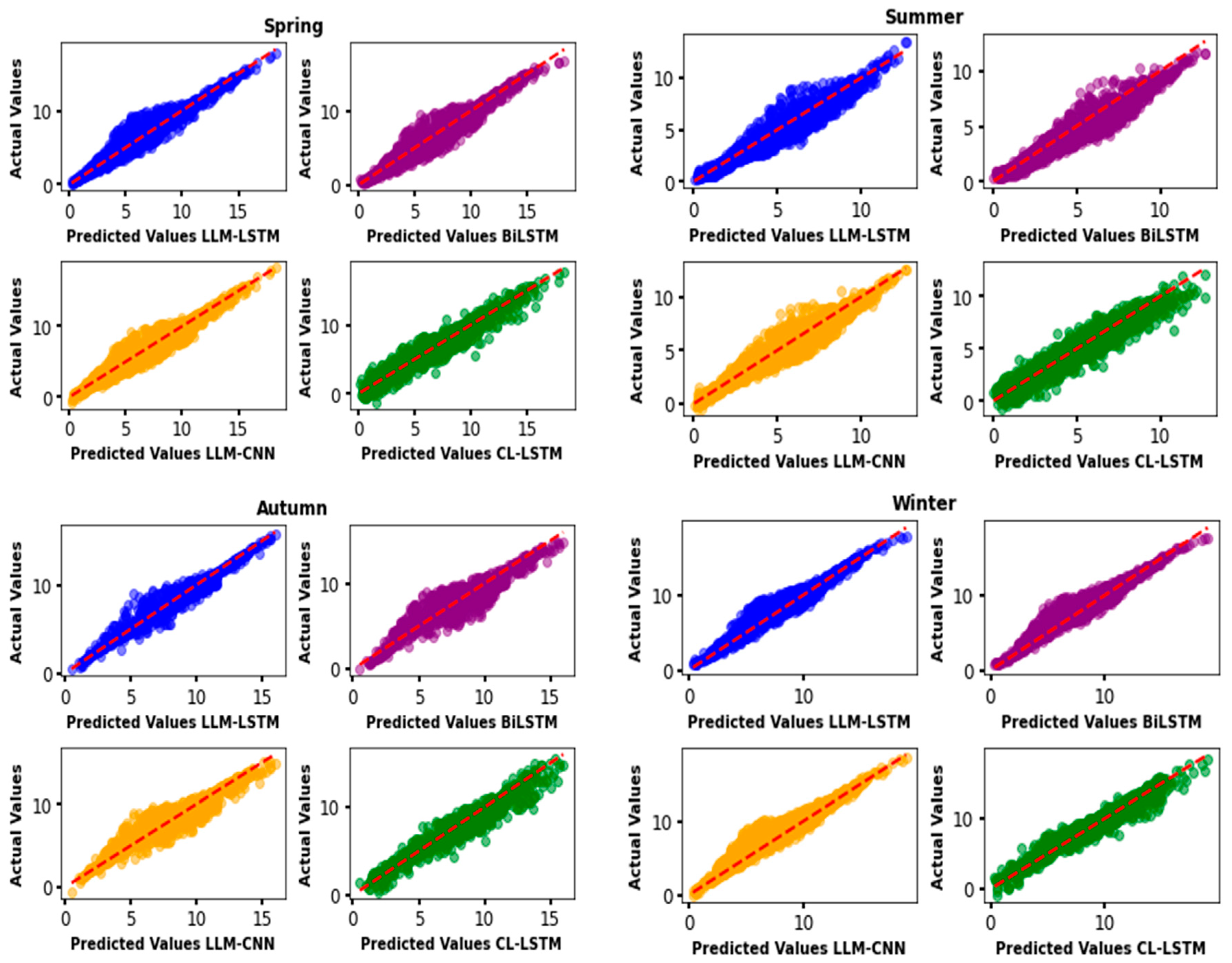

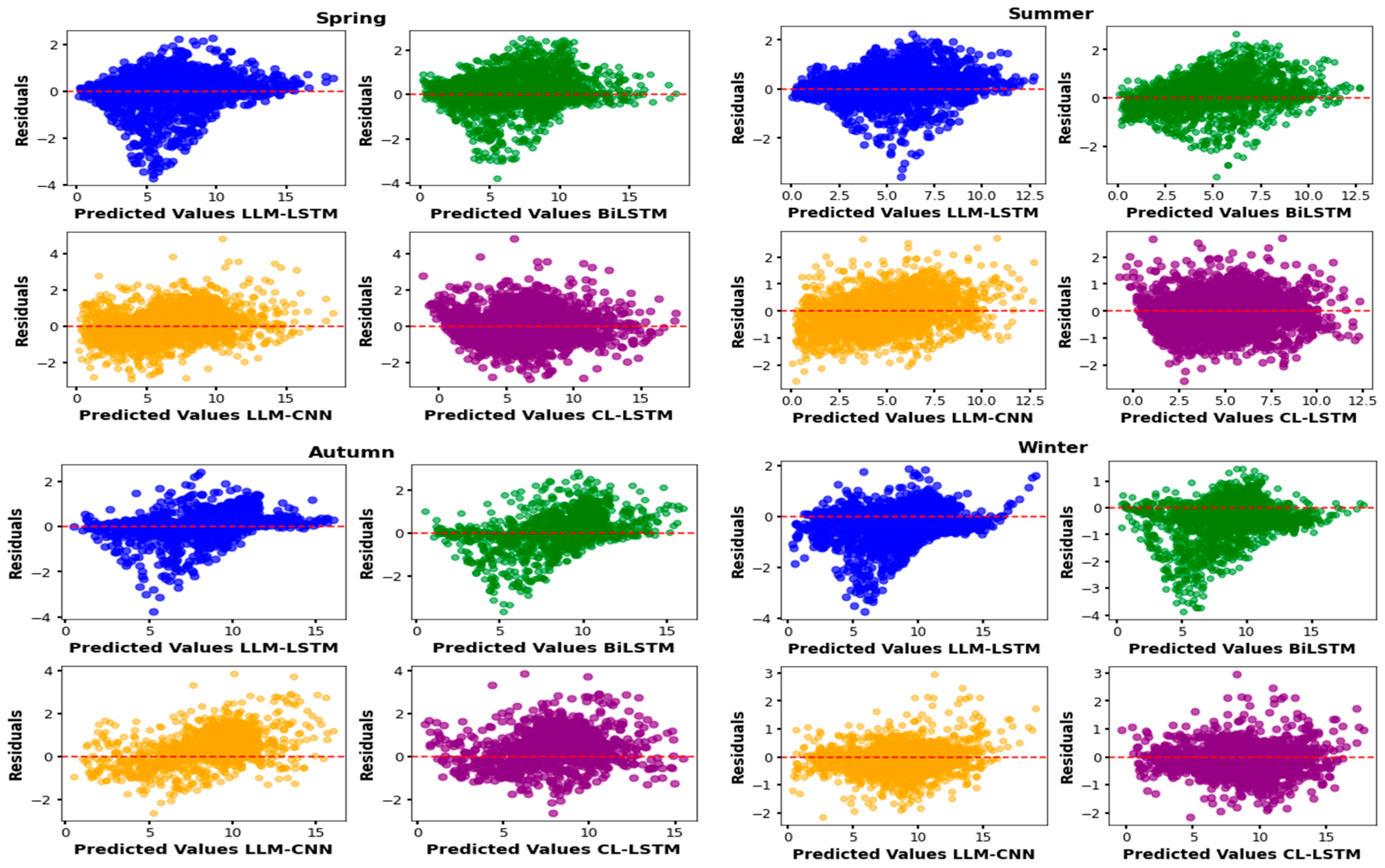

4.3. Linear Regression and Residuals Graph

4.4. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Wind Speed Values

| Models | Autumn | Spring | Winter | Summer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V(10m/s) | V(100m/s) | V(10m/s) | V(100m/s) | V(10m/s) | V(100m/s) | V(10m/s) | V(100m/s) | ||

| LLM_LSTM | Max | 15.70 | 24.88 | 18.08 | 28.65 | 17.36 | 27.51 | 12.33 | 19.54 |

| Q3 | 12.11 | 19.19 | 12.48 | 19.78 | 13.23 | 20.97 | 8.48 | 13.44 | |

| Q2 | 8.53 | 13.01 | 8.52 | 13.50 | 9.10 | 14.42 | 4.64 | 7.35 | |

| Q1 | 4.46 | 7.07 | 3.74 | 5.93 | 4.75 | 7.53 | 2.36 | 3.74 | |

| Min | 0.40 | 063 | 0.59 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 1.38 | 0.09 | 0.14 | |

| BiLSTM | Max | 15.94 | 25.26 | 17.49 | 27.72 | 17.46 | 27.67 | 12.22 | 19.37 |

| Q3 | 12.16 | 19.27 | 11.99 | 19.00 | 13.13 | 20.81 | 8.54 | 13.53 | |

| Q2 | 8.33 | 13.20 | 8.15 | 12.92 | 8.80 | 13.95 | 4.87 | 7.72 | |

| Q1 | 4.53 | 7.18 | 3.48 | 5.52 | 7.75 | 7.53 | 2.70 | 4.28 | |

| Min | 0.67 | 1.06 | 0.46 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 1.11 | 0.53 | 0.84 | |

| LLM_CNN | Max | 15.29 | 24.23 | 17.91 | 28.39 | 18.87 | 29.91 | 12.27 | 19.45 |

| Q3 | 11.96 | 18.96 | 12.21 | 19.35 | 14.07 | 22.30 | 8.54 | 13.53 | |

| Q2 | 8.08 | 12.81 | 8.19 | 12.98 | 9.27 | 14.69 | 4.63 | 7.34 | |

| Q1 | 4.48 | 7.10 | 3.33 | 5.28 | 4.63 | 7.34 | 2.43 | 3.85 | |

| Min | 0.33 | 0.52 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.98 | 1.55 | 0.23 | 0.36 | |

| CL_LSTM | Max | 15.52 | 24.60 | 17.58 | 27.86 | 17.76 | 28.15 | 12.31 | 19.51 |

| Q3 | 11.88 | 18.83 | 11.97 | 18.97 | 13.36 | 21.17 | 8.56 | 13.57 | |

| Q2 | 8.09 | 12.82 | 8.50 | 13.47 | 8.95 | 14.18 | 5.96 | 9.45 | |

| Q1 | 4.38 | 6.94 | 3.96 | 6.28 | 4.65 | 7.37 | 2.79 | 4.42 | |

| Min | 0.52 | 0.82 | 1.55 | 2.46 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.77 | 1.22 | |

4.5. Energy Prediction from Selected Model

4.6. Determining Wind Direction

5. Conclusion and Outlook

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations and Acronyms

| WED | Wind Energy Density |

| V | Wind speed, m/s |

| Probability of observing wind seed | |

| Wind power, kwh | |

| VC | Cut-in wind speed, m/s |

| CF | Capacity Factor, % |

| N | The number of data pairs |

| X | The values of the first variable |

| Y | The values of the second variable |

| The sum of the values of the first variable | |

| The sum of the values of the first variable | |

| The sum of the values of the second variable | |

| The sum of the squares of the values of the first variable | |

| ∑Y2∑Y2 | The sum of the squares of the values of the second variable |

| Shape factor | |

| Scale factor (m/s) | |

| ,, | Heights |

| Reference speed | |

| Total number of trees in the ensemble | |

| Activation function | |

| Weight associated with each connection | |

| Specific regression model | |

| ƛ | Bias or intercept of the model |

| Predicted value | |

| Pegularization parameter | |

| Associated coefficient | |

| J(β) | Cost function to minimize |

| previous hidden state | |

| input at time t | |

| Sigmoid function. | |

| Element by element product (Hadamard product). | |

| Cell status at time t. | |

| ,,,,,,, | are the weights and biases learned by the network |

| Hidden state of front LSTM encoder. | |

| Hidden state of rear LSTM encoder | |

| is the word at time t ; | |

| is the embedding of the word x(t) | |

| is the hidden state of the LSTM layer at time | |

| is the output of the convolution layer | |

| is the output of the pooling layer at time t | |

| is the sigmoid activation function | |

| is the hyperbolic tangent activation function | |

| ,,,, | are the weight matrices |

| ,,,,, | are the bias vectors |

| ,,, | are the weight matrices for recurrent connections |

References

- Mehazzem, F., André, M., & Calif, R. (2022). Efficient output photovoltaic power prediction based on MPPT fuzzy logic technique and solar spatio-temporal forecasting approach in a tropical insular region. Energies, 15(22), 8671. [CrossRef]

- Afshar, K., Ghiasvand, F. S., & Bigdeli, N. (2018). Optimal bidding strategy of wind power producers in pay-as-bid power markets. Renewable Energy, 127, 575-586. [CrossRef]

- Shields, M., Stefek, J., Oteri, F., Kreider, M., Gill, E., Maniak, S., ... & Hines, E. (2023). A Supply Chain Road Map for Offshore Wind Energy in the United States (No. NREL/TP-5000-84710). National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), Golden, CO (United States). [CrossRef]

- Naik, J., Bisoi, R., & Dash, P. K. (2018). Prediction interval forecasting of wind speed and wind power using modes decomposition based low rank multi-kernel ridge regression. Renewable energy, 129, 357-383. [CrossRef]

- uang, Y., Liu, S., & Yang, L. (2018). Wind speed forecasting method using EEMD and the combination forecasting method based on GPR and LSTM. Sustainability, 10(10), 3693. [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyay, A., Seshadri, A. K., Sparks, N. J., & Toumi, R. (2022). The role of wind-solar hybrid plants in mitigating renewable energy-droughts. Renewable Energy, 194, 926-937. [CrossRef]

- Lahouar, A., & Slama, J. B. H. (2017). Hour-ahead wind power forecast based on random forests. Renewable energy, 109, 529-541. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. A., Doubrawa, P., Xue, L., Newman, A. J., Draxl, C., & Scott, G. (2019). Wind resource assessment for Alaska’s offshore regions: validation of a 14-year high-resolution WRF data set. Energies, 12(14), 2780. [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, C. D., Alvarez, M. A., & Giraldo, E. (2015). Short-term wind speed prediction based on robust Kalman filtering: An experimental comparison. Applied Energy, 156, 321-330. [CrossRef]

- Torres, J. L., Garcia, A., De Blas, M., & De Francisco, A. (2005). Forecast of hourly average wind speed with ARMA models in Navarre (Spain). Solar energy, 79(1), 65-77. [CrossRef]

- He, Q., Wang, J., & Lu, H. (2018). A hybrid system for short-term wind speed forecasting. Applied energy, 226, 756-771. [CrossRef]

- Cadenas, E., Jaramillo, O. A., & Rivera, W. (2010). Analysis and forecasting of wind velocity in chetumal, quintana roo, using the single exponential smoothing method. Renewable Energy, 35(5), 925-930. [CrossRef]

- Samet, H., & Marzbani, F. (2014). Quantizing the deterministic nonlinearity in wind speed time series. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 39, 1143-1154. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, T., Zha, X., & Qin, L. (2017). A combined multivariate model for wind power prediction. Energy Conversion and Management, 144, 361-373. [CrossRef]

- Lahouar, A., & Slama, J. B. H. (2017). Hour-ahead wind power forecast based on random forests. Renewable energy, 109, 529-541. [CrossRef]

- Zhen, H., Niu, D., Yu, M., Wang, K., Liang, Y., & Xu, X. (2020). A hybrid deep learning model and comparison for wind power forecasting considering temporal-spatial feature extraction. Sustainability, 12(22), 9490. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Cao, Z., Zhang, J., Wang, L., Huang, C., & Luo, X. (2020). Short-term wind speed forecasting based on the Jaya-SVM model. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 121, 106056. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Z., Wang, Y., & Jiang, P. (2015). The study and application of a novel hybrid forecasting model–A case study of wind speed forecasting in China. Applied Energy, 143, 472-488. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. U., Khan, N., Ullah, F. U. M., Kim, M. J., Lee, M. Y., & Baik, S. W. (2023). Towards intelligent building energy management: AI-based framework for power consumption and generation forecasting. Energy and buildings, 279, 112705. [CrossRef]

- « Licht, A., Folch, A., Sylvestre, F., Yacoub, A. N., Cogné, N., Abderamane, M., ... & Deschamps, P. (2024). Provenance of aeolian sands from the southeastern Sahara from a detrital zircon perspective. Quaternary Science Reviews, 328, 108539. [CrossRef]

- Remini, B. (2018). Tibesti-Ennedi-Chad Lake: the triangle of dust impact on the fertilization of the Amazonian forest. LARHYSS Journal P-ISSN 1112-3680/E-ISSN 2521-9782, (34), 147-182.

- Washington, R., Todd, M. C., Engelstaedter, S., M’Bainayel, S., & Mitchell, F. (2006). Dust and the low level circulation ov er the Bodele Depression, Northern Chad. Journal of Geophysical Research, 111. [CrossRef]

- Remini, B. (2018). Tibesti-Ennedi-Chad Lake: the triangle of dust impact on the fertilization of the Amazonian forest. LARHYSS Journal P-ISSN 1112-3680/E-ISSN 2521-9782, (34), 147-182.

- Tatari, O., & Kucukvar, M. (2011). Cost premium prediction of certified green buildings: A neural network approach. Building and Environment, 46(5), 1081-1086. [CrossRef]

- Fogno Fotso, H. R., Aloyem Kazé, C. V., & Djuidje Kenmoé, G. (2021). A novel hybrid model based on weather variables relationships improving applied for wind speed forecasting. International Journal of Energy and Environmental Engineering, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Wan, A., Peng, S., Khalil, A. B., Ji, Y., Ma, S., Yao, F., & Ao, L. (2024). A novel hybrid BWO-BiLSTM-ATT framework for accurate offshore wind power prediction. Ocean Engineering, 312, 119227. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C., Bu, S., Chen, W., Wang, H., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Deep Reinforcement Learning-Assisted Federated Learning for Robust Short-Term Load Forecasting in Electricity Wholesale Markets. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Gollagi, S. G., & Balasubramaniam, S. (2023). Hybrid model with optimization tactics for software defect prediction. International Journal of Modeling, Simulation, and Scientific Computing, 14(02), 2350031. [CrossRef]

- Tefera, E., Martínez-Ballesteros, M., Troncoso, A., & Martínez-Álvarez, F. (2023, August). A new hybrid cnn-LSTM for wind power forecasting in ethiopia. In International Conference on Hybrid Artificial Intelligence Systems (pp. 207-218). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Niu, X., & Wang, J. (2019). A combined model based on data preprocessing strategy and multi-objective optimization algorithm for short-term wind speed forecasting. Applied Energy, 241, 519-539. [CrossRef]

- Nematchoua, M. K., Orosa, J. A., & Afaifia, M. (2022). Prediction of daily global solar radiation and air temperature using six machine learning algorithms; a case of 27 European countries. Ecological Informatics, 69, 101643. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J., Wang, X., Wu, L., Zhang, F., Bai, H., Lu, X., & Xiang, Y. (2018). New combined models for estimating daily global solar radiation based on sunshine duration in humid regions: a case study in South China. Energy conversion and management, 156, 618-625. [CrossRef]

- Satwika, N. A., Hantoro, R., Septyaningrum, E., & Mahmashani, A. W. (2019). Analysis of wind energy potential and wind energy development to evaluate performance of wind turbine installation in Bali, Indonesia. Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Sciences, 13(1), 4461-4476. [CrossRef]

- Cetinay, H., Kuipers, F. A., & Guven, A. N. (2017). Optimal siting and sizing of wind farms. Renewable Energy, 101, 51-58. [CrossRef]

- Boro, D., Donnou, H. E. V., Kossi, I., Bado, N., Kieno, F. P., & Bathiebo, J. (2019). Vertical profile of wind speed in the atmospheric boundary layer and assessment of wind resource on the Bobo Dioulasso site in Burkina Faso. [CrossRef]

- Soulouknga, M. H., Oyedepo, S. O., Doka, S. Y., & Kofane, T. C. (2020). Evaluation of the cost of producing wind-generated electricity in Chad. International Journal of Energy and Environmental Engineering, 11, 275-287. [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, R., Hassan, M. Y., Raheem, A., & Rasheed, N. (2016). Wind farm layout optimization using area dimensions and definite point selection techniques. Renewable energy, 88, 154-163. [CrossRef]

- Lazić, L., Pejanović, G., & Živković, M. (2010). Wind forecasts for wind power generation using the Eta model. Renewable Energy, 35(6), 1236-1243. [CrossRef]

- Nediguina, M. K., Abdraman, M. A., Barka, M., & Tahir, A. M. (2022). Electric Water Pumping Powered by a Wind Turbine in North East Chad. World Journal of Applied Physics, 7(2), 21-31. [CrossRef]

- El Khadimi, A., Bchir, L., & Zeroual, A. (2004). Dimensionnement et Optimisation Technico-économique d’un système d’Energie Hybride photovoltaïque-Eolien avec Système de stockage. Journal of Renewable Energies, 7(2), 73-83. [CrossRef]

- Pavarini, C., Battery storage is (almost) ready to play the flexibility game, IEA: International Energy Agency. France. Retrieved from https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/8sw59s.

- Amrouche, B., & Le Pivert, X. (2014). Artificial neural network based daily local forecasting for global solar radiation. Applied energy, 130, 333-341. [CrossRef]

- Foley, A. M., Leahy, P. G., Marvuglia, A., & McKeogh, E. J. (2012). Current methods and advances in forecasting of wind power generation. Renewable energy, 37(1), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Bekele, G., & Tadesse, G. (2012). Feasibility study of small Hydro/PV/Wind hybrid system for off-grid rural electrification in Ethiopia. Applied Energy, 97, 5-15. [CrossRef]

- Lawal, A., Rehman, S., Alhems, L. M., & Alam, M. M. (2021). Wind speed prediction using hybrid 1D CNN and BLSTM network. IEEE Access, 9, 156672-156679. [CrossRef]

- Li, P., Yang, H., Wu, H., Wang, Y., Su, H., Zheng, T., ... & Han, Y. (2024). Deep learning model for solar and wind energy forecasting considering Northwest China as an example. Results in Engineering, 24, 102939. [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, L. M., Pereira, B., David, M., Díaz, F., & Lauret, P. (2015). Use of satellite data to improve solar radiation forecasting with Bayesian Artificial Neural Networks. Solar Energy, 122, 1309-1324. [CrossRef]

- Foley, A. M., Leahy, P. G., Marvuglia, A., & McKeogh, E. J. (2012). Current methods and advances in forecasting of wind power generation. Renewable energy, 37(1), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Kidmo, D. K., Bogno, B., Deli, K., & Goron, D. (2020). Seasonal wind characteristics and prospects of wind energy conversion systems for water production in the far North Region of Cameroon. Smart Grid and Renewable Energy, 11(9), 127-164. [CrossRef]

- Li, P., Yang, H., Wu, H., Wang, Y., Su, H., Zheng, T., ... & Han, Y. (2024). Deep learning model for solar and wind energy forecasting considering Northwest China as an example. Results in Engineering, 24, 102939. [CrossRef]

- Lawal, A., Rehman, S., Alhems, L. M., & Alam, M. M. (2021). Wind speed prediction using hybrid 1D CNN and BLSTM network. IEEE Access, 9, 156672-156679. [CrossRef]

| Model | MAE (m/s) | RMSE (m/s) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BiLSTM-CNN [16] | 1.7344 | 2.5492 | 0.9929 |

| CL-LSTM [17] | 1.8983 | 2.7343 | 0.9918 |

| CNN-LSTM [18] | 1.8296 | 2.6307 | 0.9924 |

| BiLSTM [19] | 1.6500 | 2.3000 | 0.9960 |

| CNN-BiLSTM [20] | 0.1042 | 0,1309 | 0.9413 |

| Bi-GRU [21] | 0.0122 | 0.0187 | 0.9887 |

| LSTM-DBN [22] | 0.872 | 1.1055 | 0.8170 |

| CNN-LSTM [23] | 0.512 | 0.703 | 0.7030 |

| Variables | Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Temperature | 0.73 |

| Wind direction | -0.64 |

| Relative humidity | -0.55 |

| Atmospheric pressure | 0.78 |

| Model | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| CNN-LSTM | Combines the feature extraction benefits of CNNs and LSTMs for temporal modeling. | Complex to implement and difficult to optimize. |

| BiLSTM | Captures dependencies in both forward and reverse directions; less sensitive to variations and noise in the data. | Computationally more complex and time-consuming than simple LSTMs. |

| Cl-LSTM | Incorporates convolutional layers to extract local features before temporal modeling. Effective for data with both spatial and temporal structures. |

More complex to train and tune than simple LSTM models. Computationally time-consuming; may require significant computational resources. |

| LLM-LSTM | Ability to handle large data sequences; good for long-term forecasting. | Very demanding in terms of data resources; complex to implement. |

| Metrics | Equation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| MAE | (23) | The mean absolute error is a quantity often used to measure the deviation between observed and predicted values. Its mathematical formula is given by equation (23) [35]. |

| RMSE | (24) | RMSE is a measure of the variation of predicted values around measured values. The smaller its value, the better the model. The square root of the mean square error is defined according to formula (24) [35]. |

| R2 | (25) | The coefficient of determination R² is a statistical measure of how closely a model’s predictions match the actual values [36,37]. It is defined by formula (25). |

| Models | Metrics | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLM-LSTM | MAE | 0.556 | 0.442 | 0.435 | 0.469 |

| RMSE | 0.820 | 0.629 | 0.647 | 0.689 | |

| R2 | 0.932 | 0.933 | 0.939 | 0.940 | |

| BiLSTM | MAE | 0.502 | 0.494 | 0.586 | 0.535 |

| RMSE | 0.745 | 0.686 | 0.812 | 0.740 | |

| R2 | 0.944 | 0.920 | 0.904 | 0.931 | |

| LLM-CNN | MAE | 0.503 | 0.500 | 0.523 | 0.566 |

| RMSE | 0.752 | 0.689 | 0.766 | 0.830 | |

| R2 | 0.943 | 0.919 | 0.914 | 0.914 | |

| CL-LSTM | MAE | 0.636 | 0.531 | 0.628 | 0.020 |

| RMSE | 0.848 | 0.679 | 0.811 | 0.027 | |

| R2 | 0.927 | 0.922 | 0.902 | 0.966 |

| Seasons | V0 | K0 | C0 (m/s) | FC | E (MWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | 8.34 | 3.03 | 9.34 | 0.68 | 4.25 |

| Summer | 5.025 | 2.38 | 6.76 | 0.55 | 0.89 |

| Autumn | 8.42 | 3.05 | 9.42 | 0.68 | 4.10 |

| Winter | 8.95 | 3.14 | 10.00 | 0.69 | 4.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).