1. Introduction

In the last decade, several stakeholders have been convinced that replacing fossil fuel with green hydrogen and its derivative products will need a strong and resilient business model that ensures that long-term financing and offtake agreements are in place alongside reliable technology and favorable policies [

1]. This will accelerate an energy transition to a green economy that is characterized by zero or reduced Green House Gas (GHG) emissions.

This study evaluates the different financing mechanisms for renewable energy and clean technologies like green hydrogen to enhance a green economy in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), by leveraging clean energy sources like renewable resources (wind and solar), water, and abundant land [

2]. The significance of this study is that green financing mechanisms can promote green hydrogen development. Green hydrogen energy shows the potential to provide fuel for all economic sectors that are currently fossil fuel-based by utilizing their renewable resources and transforming grids to achieve 100% zero-carbon energy [

3] . Further, this can contribute to decarbonizing the economies and achieving energy transition by 2030 in SSA. Given that climate change is caused by excessive GHG emissions, energy transformation opens new investment opportunities and the need to finance green economies [

4].

According to the African Development Bank (AfDB), the uptake of the proposed green hydrogen project should be founded on well-articulated financial agreements between the financial institutions, the industry, and the policymakers. Further, the use of incentives like subsidies is encouraged [

1].

Green energy finance is essential to hydrogen energy development because it can contribute positively to closing the existing gap between the current Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), particularly, communicating the post-2020 climate efforts as NDCs help limit global temperature rises well below 2°C, and the different initiatives needed to achieve the Paris temperature targets [

5]. Globally green hydrogen has gained a lot of interest among the different stakeholders.

Project finance is a way to attract capital flow that would help build a project. This can be achieved through debt acquisition or having an equity investment plan, which involves debt and or financial resources from another stakeholder [

6]. Before financing any project, most financial institutions assess the credentials or technical abilities of the project developer to build or install high-quality infrastructure that will guarantee adequate equity returns or the project’s capability to repay the loan.

Although renewable energy resources are variable renewable energy systems (VRES) in nature, they can leverage on utilizing electrolyzers that can operate at lower temperatures (20-100°C) like the Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) [

7]. However, this does not imply that other electrolyzers with higher temperature ranges cannot be used. Further, most financial institutions negotiate project financing, considering the projects’ future gains or capital flow as offtake agreements. Other factors that boost the project’s viability, feasibility, and desirability include the location, the market conditions, and the risk associated with the proposed project [

8].

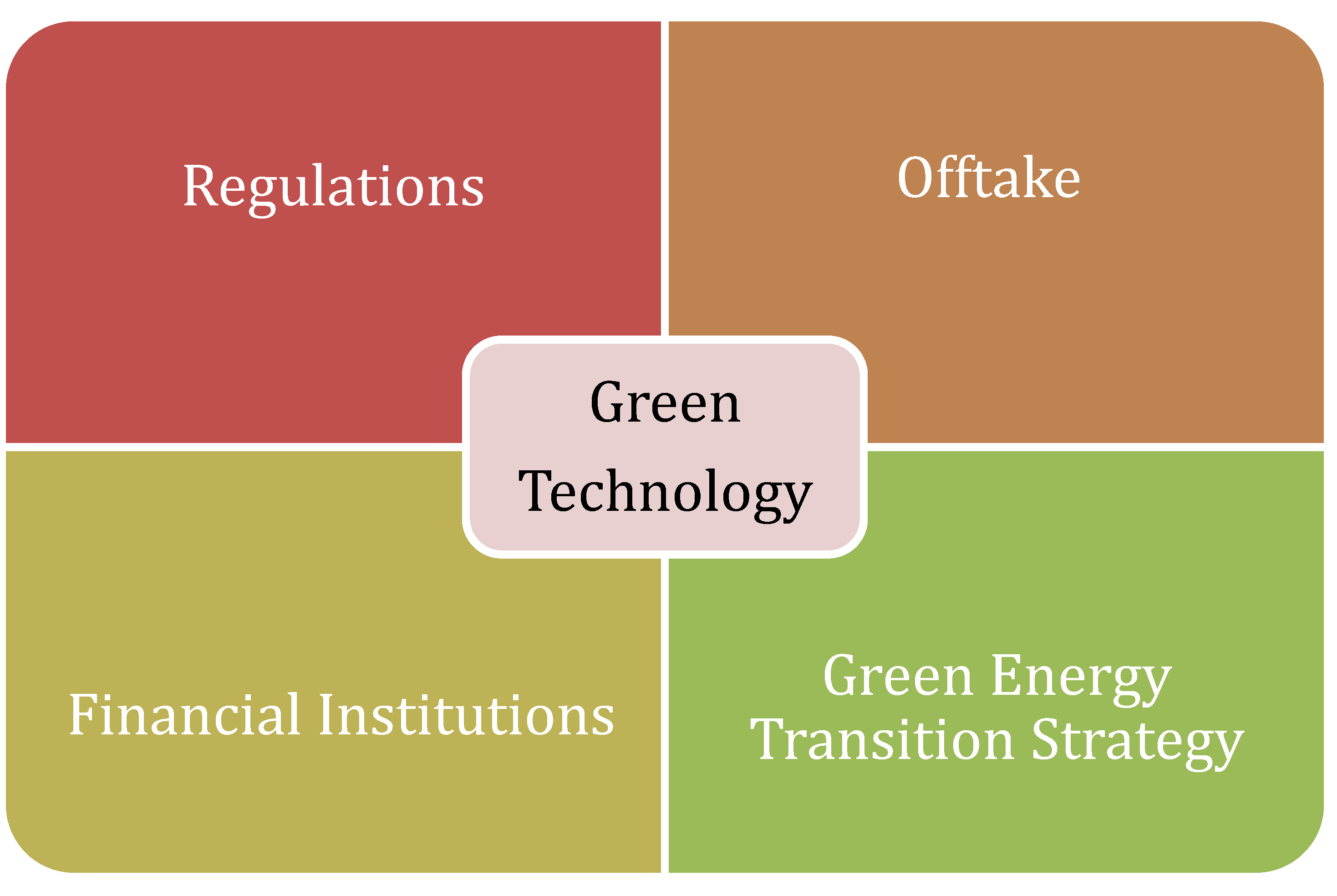

Figure 1 shows how these different stakeholders interact with each other.

Figure 1 shows that green hydrogen project finance is anchored on five interlocked key thematic areas for hydrogen energy development. These include having favorable green hydrogen regulations, promising offtake, tested and reliable technology, green energy transition strategies, and financial institutions to achieve a resilient business model. Further to make a resilient business case that can attract investors, all the interlinking factors must be taken into consideration while noting that the technology (electrolysis membrane) is the core of the green hydrogen energy financing model because it is the most dominant process for energy production, and its utilization, and application. Technology has a greater impact on the cost of hydrogen development [

9].

However, Green hydrogen financing will not come without any challenges and risks. Some of these risks may include; poor energy project developers, poor funding/ loan availability, poor electrical grid infrastructure, road network, natural calamities and pandemics, political instability, and other security risks like war, to mention only a few.

While the main purpose of this review is to analyze the potential financing mechanisms for green hydrogen development in sub-Saharan Africa, the key issues like policies, strategies, financing institutions, and the risks associated with the financing mechanisms are addressed. The main objectives that address this purpose include:

Examine Policy and Regulatory Frameworks: Investigate the role of policy and regulatory frameworks in facilitating green hydrogen projects and attracting investments.

Evaluate Financing Mechanisms: Assess the available and the most promising financing mechanisms for mobilizing funds to support renewable energy and green hydrogen development in SSA.

Propose Strategies for Scale-Up: Develop strategies for scaling up green hydrogen production and infrastructure in SSA, considering technical, financial, and market challenges.

Identify Opportunities and Risks: Analyze the opportunities and risks associated with transitioning to a net-zero emission economy driven by hydrogen energy in SSA.

The overarching reason for conducting this study was to complement and provide supporting data for the H2Atlas Africa project [

10].

This review article is limited to highlighting the financing mechanisms of the green hydrogen economy for hydrogen production and the associated enablers in a market perspective. The hydrogen opportunities are also indirectly presented by only highlighting the risks, supporting policies, strategies, funding institutions and available modes without analyzing the success and failure rate of these mechanisms. One key limitation to this work is that although hydrogen energy technology is a core element for the green hydrogen financing model that we developed (

Figure 1), not enough information or deployment evidence of electrolysis technology and other clean energy technologies in SSA have been provided in this study.

The significance of green financing is presented through value-added services that are derived from the three business opportunity streams, manufacturing, hydrogen production, and hydrogen infrastructure for end-uses in the entire value chain network. Three key significant factors derived from the study are:

Green Economy Transition: The study emphasizes the importance of green financing mechanisms in promoting green hydrogen development, which can help transition economies to zero-carbon energy.

Investment Opportunities: Green hydrogen projects present new investment opportunities, contributing to decarbonizing economies and achieving energy transition by 2030 in SSA.

Policy and Regulatory Support: The research underscores the need for sound policies and regulatory environments to attract private investments and ensure sustainable development.

These factors give investors, policymakers, and international organizations some insight on the ease or complexity of doing business in SSA. This article adopts an outline; and introduction followed by the methodology which highlights the approach, financing a green economy, financing mechanisms, scaling up strategies (including policies), risk factors, and opportunity factors.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, a mixed-method approach was adopted to review the potential financing mechanisms for green hydrogen development in SSA. While the primary purpose or main objective was evaluating the financing mechanisms in SSA, four (4) key specific themes identified include (1) green financing (2) policy and regulatory frameworks (2) financing mechanisms/ modes (3) scaling up strategies (4) opportunities and risks associated with green financing in SSA.

The review study focused on obtaining primary data from the utility firms through focused group discussions from the H2Atlas Africa project findings alongside credible secondary data from the energy utility firms. Other secondary data was also obtained from international organizations like the World Bank, IPCC, IMF, IEA etc. Peer-reviewed journals were also targeted.

Our search criteria relied on key search words that align with the four thematic areas identified in the first paragraph of this methodology. Further, we also searched using the following article key phrases; hydrogen finance in SSA, hydrogen investment in SSA; hydrogen public-private in SSA; green hydrogen in SSA, and renewable energy investment risks in SSA. When data discrepancies existed, cross-checking the reference with the actual source data was done. Some key databases used include EBSCO, Google Scholar, Web of Science, SAGE, Scopus, etc. Due to the nature of data resource scarcity, no data was excluded but the very latest ones in the area of hydrogen and renewable energy were selected.

The analysis of the data was done alongside the thematic areas and the green financing model (

Figure 1) discussion and descriptions. The purpose of this review is to analyze the potential financing mechanisms for green hydrogen development in sub-Saharan Africa. The key issues like policies, strategies, and financing institutions were addressed, and the risks associated with the financing mechanisms are addressed.

A risk matrix was developed to analyze the opportunities and risks associated with green financing and green hydrogen production potential, with a focus on (1) project oversights during the implementation and commissioning phase (e.g., capital cost exceeded) (2) funding/ loan availability (3) electrical grid connection issues (4) high pressure and large quantity hydrogen storage (5) hydrogen transport using pipelines or trucks (6) pandemics or natural calamities & climate change (7) political instability/change of governments and (8) other security risks like war. These focus areas were given weights on a scale of 0-16 after a careful scientific and backed-up allocation method as follows:

0 – 3 score is a low risk that requires remedial action at the project/program manager’s discretion.

4 – 6 score is a medium risk that requires remedial action be taken at the appropriate time

7 – 8 score is high risk and requires remedial action to be given high priority

10 – 16 score is a very high risk that may not make operations go on smoothly and therefore would need immediate action to operate.

The conclusions of the review article are drawn from the entire analysis but with a bias towards financing mechanisms/ modes. All other analysis, including the risk matrix, was designed to address the financing mechanisms which is essentially the purpose of the study.

3. Financing the Green Economy Transition

Financing to achieve a green economy is referred to as green financing. The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) defines green financing as an increase of the level of financial flows (from the banks, micro-credit, insurance, and investment) from the public, private, and not-for-profit sectors to sustainable development priorities [

11]. It may incorporate grants, loans, investments, or debt mechanisms that decarbonize economies or limit the effect of climate change. To achieve green economies in SSA, and to attain self-sustainability, linking green finance with policy reforms is critical. Such innovative approaches would support governments in formulating sound green policies for a green economy and conjointly developing strategies that build responsive financial investment systems that are sustainable [

12,

13].

The five key sectors that can unlock financial investment, economic growth, and sustainability opportunities for financing a green economy transformation are shown in

Figure 2.

A green hydrogen economy is reflected in three main economic sectors: industries, transportation, and energy production [

14], including the entire supply chain network. This compounds into three business streams [

15]:

manufacturing of upstream and downstream equipment,

hydrogen production and

infrastructures for hydrogen end-uses alongside the entire value chain network.

This development presents different challenges and risk profiles for each of these business streams. Before approving a green hydrogen loan, financing institutions focus on assessing (i) the investment risk for green hydrogen’s offtake and (ii) developing cost-effective financing mechanisms along the supply chain network. The purpose of this two-factor evaluation approach of green finance is to develop or unravel the private sector finance and public sector financing mechanisms for green hydrogen development in SSA.

4. Green Financing Mechanisms

In Africa, green finance is considered vital for economic development. It offers access to diverse funding pools, providing a source of low-cost and much-needed capital to finance infrastructure and set up green funding programs [

16]. Every African country has huge green resources, but financing difficulties have prevented most countries from having the ability to exploit their potential [

17]. However, there are various sources and forms of green finance that are open to most African countries [

18]. Many African states have indicated their intention through the Paris Agreement to facilitate and undertake green issuance into their national plan. Green financing mechanisms are a perfect fit for African nations that must balance the need for infrastructure projects with raising capital to meet their Sustainable Development Goals [

16]. There is an urgent need for governments, the private sector, and donors to invest in green projects by working together and leveraging their unique opportunities to drive a green economy and improve people’s living conditions. Over Africa, there are at least five sources of green funding. These include i) Country government sources, ii) Multilateral and bilateral development sources, iii) Carbon financing, iv) Private sector sources, and v) New and upcoming innovative financing [

19].

Government resources alone are inadequate to attract international investment requirements for scaling up green services. On one part these resources are limited and worse still several other sectors of the economy compete for the same resources with the private sector, and this makes most of the private investors in Sub-Saharan African countries find it risky to invest in clean energy including renewable energy[

20] (Okonkwo, 2021

; N’Guessan, 2012)

. This is largely connected to the different countries’ prevailing investment and business climate. Therefore, to attract private investors to the green program, the government must improve the policy and regulatory environment and create market-based mechanisms to incentivize businesses. Mobilizing multilateral and bilateral financing institutions is vital for ensuring the sustainable development of the green market in Africa. For instance, in 2020, the Multilateral Development Banks (MDB) invested about US

$66 billion in low-carbon projects of which 58% was committed in low- and middle-income countries. These included the Climate Investment Funds (CIF), Green Climate Fund (GCF), and climate-related funds under the Global Environment Facility (GEF), EU blending facilities, and others [

23]. The AfDB has doubled its climate finance to US

$ 25 billion for the period 2020-25, giving priority to adaptation finance and promotion of green growth [

24]. The Bank supports its member countries in three ways. Firstly, by encouraging them to mainstream clean energy options into national development plans and energy planning. Secondly, by promoting investment in clean energy and energy efficiency ventures. Finally, by supporting the sustainable exploitation of the huge clean energy potential of the continent. Other financing mechanisms include the Sustainable Energy Fund for Africa (400 million USD). The AfDB projects to reach at least 70% by 2030 of its committed operations supporting green finance (about US

$ 80 billion).

Another financing mechanism for renewable energy is carbon finance. Carbon finance is an innovative funding mechanism that associates the economic value of carbon emissions offset as carbon credits earned for a sustainable project that they have implemented [

25]. According to the World Bank Group, a 5-year Climate Change Action Plan will support transformative investments in key sectors that contribute the most to global greenhouse gas emissions [

26]. Low-carbon transitions in energy, transport, cities, manufacturing, and food are expected to generate trillions of dollars of investment and millions of new jobs over the next decade [

29]. A further analysis of the financing climate in SSA, benchmarking with the global trends that take into consideration interest rates, inflation, exchange rate stability, infrastructure, and agreements (bilateral & multilateral) is explained in section 3.1.

4.1. General Financing Climate

According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), climate finance is "finance that aims at reducing emissions and enhancing sinks of greenhouse gases and aims at reducing the vulnerability of, and maintaining and increasing the resilience of, human and ecological systems to negative climate change impacts.” In sub-Saharan Africa, due to the threats posed by current climate impacts and the challenges of future climate vulnerability, the gap between resource needs and flows needed to build the continent's resilience to an increasingly hostile climate is alarming. Support for Sub-Saharan Africa is critical in addressing the fight against climate change; many people are already leaving the continent due to extreme conditions, caused by rising temperatures. Without financial support, climate change is expected to push tens of millions more Africans into extreme poverty by 2030 [

36]. Therefore, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 2010 set up the largest databases on multilateral climate finance initiatives and the Green Climate Fund for developing regions such as SSA [

31]. Current levels of funding for adaptation on the continent are estimated to be about US

$3 billion a year. According to the IMF, it is estimated that SSA needs at least US

$30 billion to US

$50 billion to cope with the impacts of climate change [

20]. According to the Climate Funds Update (CFU) report, between 2003 and 2020, a total of USD 5.9 billion has been approved for 827 projects and programs for SSA, of which Just over a third or 37% of the approved funding from these multilateral climate funds has been provided for adaptation measures as shown in

Table 1. (see Table1) The level of financing currently reaching SSA countries are nowhere near enough to meet demonstrated needs, especially for immediate adaptation measures [

34]. In SSA, climate finance is unevenly distributed. From 2003 to 2020, 43 SSA countries received some climate finance, and about half (48%) of approved finance from the region went to the top ten recipient countries (South Africa, Ethiopia, DRC, Zambia, Burkina Faso, Tanzania, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, and Mali). For instance, between the years 2016 and 2019, the African continent has received only 26% of the available climate finance. The country with the most climate financing on the continent is South Africa. South Africa received the most multilateral climate financing on the continent and is placed sixth highest internationally. According to Savvidou and Trisos, this uneven distribution can be explained by no extensive mapping of climate finance to SSA [

36]. Further, Ngwenya and Simatele also explain this uneven climate finance distribution to the difficulties of many sub-Saharan SSA countries in the design and coordination of projects due to a lack of effective institutions and expertise; which also creates uneven planning and coordination of projects, [

38] Savvidou and Trisos identified five ways in which finance for adaptation to climate change in Africa falls short. These are quantity; variation among countries; neglect of some sectors; difficulty spending funds and debt [

35]. Therefore, policymakers in SSA need to revise their climate change ambitions (mitigation commitments) upwards and revise their commitments to use more renewable energy sources to maintain the low emissions economic profile by inhabitants of Africa, even with the advent of population growth and increased energy demand.

Table 1 presents the multilateral climate funds monitored by Climate Fund in the region. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) has been the main source of climate finance for SSA since its first project approvals in late 2015, with US

$1.622 billion approved to date for forty-six projects plus US

$77 million for 110 readiness programs.

Table 1 shows that between 2003 and 2020, the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), which implements urgent adaptation activities prioritized by LDCs under National Adaptation Programs of Action (NAPAs), narrowly overtook the Clean Technology Fund (CTF) as the largest contributor. It has now approved US

$679 million in grants for 177 projects. Meanwhile, the Clean Technology Fund has approved US

$661 million for fourteen renewable energy and energy efficiency projects in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda, demonstrating a clear difference in fund allocations and investment strategies.

4.2. Funding Mechanisms in SSA

Green finance in the SSA has become vital in addressing climate change and sustainable development objectives. This has led to a huge mobilization and broadening of the scope and mandate of climate investment funds, which are vital financing mechanisms for the implementation of regional environmental finance action plans and green programs in the region[

42]. For instance, in the SADC region, the Department of Financial Institutions (DFIs), governments, and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) are playing a crucial role in financing clean energy technologies within the SADC region. They are helping increase the uptake of clean energy technologies in the region by lowering tariffs, increasing funding tenors, and cutting funding costs [

43]. Multilateral Development Banks provide concessional debt and help in capacity building of the national development banks and regional financial institutions. The Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) is one of the largest financiers of renewable energy projects in Southern Africa. Other banks include China Exim Bank (CHEXIM), which offers loans to Zambia, DRC, and Zimbabwe. The other is the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), International Finance Cooperation (IFC), etc.[

43]. In West Africa, the Green Fund gives access to funding through accredited national and sub-national implementing entities (including NGOs, government ministries, national development banks, and other domestic or regional organizations) that can meet the Fund's standards. Countries can also access funding through accredited international and regional entities (such as multilateral and regional development banks and UN agencies) under international access [

44]. Private sector entities can also be accredited as implementing entities. Over the regions, allocation of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) is distributed through accredited institutions with Enhanced Direct Access (EDA), which allows countries to make their own decisions on how to use their resources. Nevertheless, the funds are only accessible through discrete projects and programs approved by the Climate Fund board. AfDB in partnership with GCF is actively engaged to ensure that West African countries have access to Climate Fund resources for financing climate actions [

45]. In addition, in sub-Saharan Africa, local governments typically finance their capital investments through 1) borrowing (bonds, loans, and grants); 2) PPPs; and 3) venture capital, 4) Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Within these funding mechanisms, several innovations such as green bonds have evolved through which local governments in sub-Saharan Africa can benefit from additional investment and capital, especially from the private sector. Some of these mechanisms are described in section 4.2.1.

4.2.1. Loans, Grants, Bonds, and Subsidies

Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to be hardest hit by the adverse effects of climate change if significant investments in mitigation and adaptation, as well as other relevant measures, remain insufficient [

46]. Therefore, climate finance offers hope in the form of green bonds. In recent years the use of green bond issuance as a tool to unlock significant capital for sustainability-related investments has gained traction in many sub-Saharan African countries [

47]. However, the nascent green bond market on the continent is still underdeveloped. In the continent, the issuance of green bonds is considered as one of the financial instruments that could help to mobilize capital for significant climate action and sustainable development. According to the World Bank, a green bond is defined as “a debt security that is issued to raise capital specifically to support climate-related environmental projects” [

48]. Green bonds, and green loans, are basic financial instruments considered as sources of green project financing. Green bonds attract a wider range of investors, including a growing list of funds mandated to invest in green projects [

49]. As part of the Nationally Determined Contributions, many SSA countries have established various climate finance systems for climate adaptation and mitigation projects. These include climate finances from development agencies like the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation, and the African Development Bank.

4.2.2. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

The literature holds that Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) can be defined as “the process that allows investors of a source country to acquire substantial ownership of capital and controlling interest in an enterprise in a host country” [

50]. It plays a vital role in the expansion dynamics of host countries by filling “development gaps”, the “foreign exchange gap”, and the “tax revenue gap” [

51]. The FDI contributes to a country's economic growth by generating domestic investment, facilitating the transfer of skills and technological knowledge, creating job opportunities, increasing local competition and global market access for locally produced export commodities, etc. [

52]. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) identified ten relevant sectors first for the SDGs and estimated an annual investment gap in developing countries amounting to US

$2.5 trillion. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, political and trade tensions, and an overall uncertain macroeconomic outlook, the expected level of global FDI flows in 2021 represents a 60% decline, from US

$ 2 trillion to less than US

$900 billion, and Africa is expected to see a decline between 25% and 40% [

53]. Consequently, the investment in Greenfield announcements for Africa fell from US

$77 billion in 2019 to US

$29 billion in 2020, and international project finance for large infrastructure projects fell by 74% to US

$32 billion. FDI can support key sectors of the SSA economies and create opportunities for the continent's growth in renewable energy capacity in Africa (to reach 310 GW by 2030), to allow the continent to build climate-resilient and low-carbon attractive investment opportunities that are anchored on renewable energy [

54].

4.2.3. Venture Capital

Venture capital is defined as independent and professionally managed, dedicated pools of capital that focus on equity or equity-linked investments in privately held, high-growth companies [

55]. Financial venture capital can be offered by venture capital firms, investment banks and other financial institutions, and high-network individuals. Venture capital firms create capital funds from a pool of money collected from other investors, companies, or funds. These firms also invest with their funds to show commitment to their clients. In Africa, venture capital is experiencing rapid and consistent growth from local and international investors. However, there is a scarce risk capital to venture capital funds. To understand this growth, African startups raised US

$2 billion in 2019 to an Africa-focused fund [

56]. Compared to other forms of funds, venture capital funds are considered unique investor protection mechanisms to secure investment. According to a study by Lin, venture capital funds are urgently needed in the context of sustainable investment by providing technical knowledge, industry relationships, or management skills, thus bringing equity financing in addition to monetary contribution [

57,

58]. Despite the financial crisis, the IFC has decided to support early-stage ventures in developing countries by investing in best-in-class entrepreneurs with venture capital funds to support the creation of emerging markets that foster private sector growth [

59].

4.2.4. Public-Private Partnership (PPP)

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) are significant financial instruments for accessing finance and reducing capital expenditure for energy infrastructure projects. According to Alloison and Carraro (2015), PPPs become more relevant where the political, policy, and financial risks associated with infrastructure investment are higher. SSA represents 5% of the total cumulative volume of PPP investment from 1990 to 2020 and expects to grow in the future [

60]. Building back better and greener in Africa requires strong partnerships between public and private investors. For instance, AfDB has partnered with the government of Morocco to finance the world’s largest concentrated solar power station extending over 3,000 hectares of desert in Morocco [

61]. The Bank through the Sustainable Energy Fund for Africa (SEFA) invested US

$965,000 to support its transition into the first Super Energy Service Company (ESCO) initiative in Africa. Governments and the private sector must adopt a ‘whole systems approach' to urgently deliver the climate-resilient and clean infrastructure that Africa needs. Scaled-up infrastructure, partnerships, integrating gender, de-risking, and mobilizing private sector finance are all essential to long-term progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals [

62].

According to the Climate Funds (2009), update, Scaling up Renewable Energy Programs in low-income African countries (SREP) under the Clean Investments Fund (CTF) aims to promote new pathways and opportunities in the energy sector using renewable energy. It provides grants, loans, guarantees and equity [

45].

Donor funding and subsidies are financing mechanisms and initiatives that target small-scale and pilot projects. IRENA (International Renewable Energy Agency) set a goal to support Southern African countries to promote sustainable electricity generation projects from renewable sources [

63].

According to IRENA, the Renewable Energy Finance and Subsidy Office (REFSO) in South Africa has supported six projects with 23.9MW capacity. It provides advice to developers and stakeholders on Renewable Energy Finance and subsidies. Eskom (the South African Electrical Utility firm) established the demand-side management subsidy solar water heater program to offer incentives to compensate for solar water heaters.

5. Hydrogen Energy Scale-Up Strategies

Transitioning to green hydrogen energy provides new development opportunities for regions with high renewable energy potential. Green hydrogen production and export can be a big stimulus for Africa because of its abundant renewable resources. By 2050, scaling up hydrogen could account for about one-fifth of the total final energy consumed, and this may account for a discount in annual CO2 emissions by around 6 gigatons (GT) and reduce global warming [

64]. The Hydrogen Council further outlines that there is a possibility for hydrogen to power 10 to 15 million cars and 500,000 trucks by 2030. In the mining and industrial sectors, hydrogen technology has the potential to create opportunities for a sustainable economic process. Takeshi Uchiyamada emphasizes in his study that the planet must transition to occasional carbon energy usage and hydrogen energy can attain this transition, especially in the power generation, industry, and transport sectors. This implies that governments and investors need to assume a prominent role in their energy plans and find strategies to proportion hydrogen projects [

64,

65].

Scaling up the production of green Hydrogen would require substantial investments. Hydrogen stands as a central pillar within the energy transition, and it is evident that there is a requirement to support and promote its large-scale deployment. Scaling up the production of green Hydrogen faces challenges [

66]. Green hydrogen production involves several processes, i.e., green electricity production, for example, solar or wind power, then electrolysis, storage, and transport. In addition, hydrogen gas is very light due to its very low density and would require specialized facilities for transportation [

7].

The electrolysis of water to produce hydrogen and oxygen is a catalyzed reaction, and for large-scale production, the kinetics need to be improved. Degradation of the catalyst is another challenge that needs to be addressed by research and development. There is also a limited number of producers of electrolyzers worldwide. These are some of the technical challenges that need to be addressed before transitioning to large-scale deployment.

A reduction in the cost of production would enable large-scale production. This includes the cost of solar power and electrolyzers. Improved funding will increase investment and promote infrastructure development. Advanced and affordable green hydrogen infrastructure combined with demand will drive the growth of the green hydrogen economy [

67]. Enactment of policies such as green public procurement and the facilitation of public-private partnerships will also contribute to the aforementioned growth.

5.1. Green Public Procurement

Green Public Procurement (GPP) refers to buying goods and services with low environmental impact across life cycles [

68]. It accounts for human health and the environment to seek prime quality products and services at competitive prices. There is a high need for countries to encourage departments to include environmental considerations when procuring goods and services. Electrolyzers should be purchased at reduced costs for affordability and to ensure reduced production costs. The government should adopt green procurement practices and set it as a compulsory requirement in tender specifications on products at the market. That helps trigger actions in response to individual incentives, for example, resource savings and market-based stimuli. Green procurement is effective in stimulating the assembly of hydrogen products [

69]. Implementing these high public purchasing powers can potentially orient production and consumption trends and encourage the demand for environmentally friendly products and services. It may also stimulate the innovation capabilities of firms in hydrogen production. Indeed, the high impact of Green Public Procurement on production activities positively influences the probability that industries invest in innovative solutions [

70]. This can present an opportunity to allow the market to search for the most cost-effective, feasible energy savings and conservation potential and compare the measures of various life cycle performance costs. Green public procurement processes consider socio-environmental factors and are increasingly referred to as sustainable public procurement (SPP).

Stoffel et al. study multidimensionality of sustainable public procurement in SSA found that SPPs have recently focused on environmental aspects, policy documents, and regulations of many countries, emphasizing social and economic aspects of public procurement for pilot projects. Further, SSA rarely implements the environmental criteria in SSA. However, some governments, like South Africa and Kenya, have concentrated on having a more effective implementation of public tenders that is country-specific while conjointly fostering socio-economic development, through preferential treatment of certain societal groups to redress past discriminations [

71].

5.2. Financial Investments of Small and Large-scale projects

Sub-Saharan Africa needs reliable and adequate financing necessary to achieve SDG 7, which emphasizes clean energy for all. To achieve this goal, small and large-scale investment projects will be needed to expand renewable energy capacity and create strong economic structures to support an African energy transition and secure the desired energy transition pathway. According to the Hydrogen Council, there is a need for more investment to scale up green hydrogen generation and thus improve its cost competitiveness. Large-scale hydrogen projects need additional financial policy support from the government or potential investors to attract private financing and investment. Establishing carbon financing and green loans financial incentives, for example, investment tax credits can help reduce the cost of investment in hydrogen projects. Lowering feed-in tariffs can help in lowering the costs of the electrolyzer. The governments need to support small and large projects through grants and incentives to increase hydrogen energy scaling up and uptake globally. There is a great need for a deliberate continental drive to leverage financial resources from existing and emerging global funds related to climate change. That will hinge on improved infrastructure and greater involvement by the private sector and banking institutions [

64].

5.3. Power Purchase Agreement Strategies

Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) is a contract between the public and private sector parties to facilitate the sale and purchase of electricity [

72]. Introducing public-private Market Facilitating Organizations in SSA at national and provincial levels will support the growth of the hydrogen market. These organizations improve networking, financing, policy advocacy, user education, technical assistance, and information dissemination that will help the green hydrogen market grow. They facilitate awareness among potential investors and business communities concerning business opportunities available on the market. Business models, for example, pay as you go, and Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can help sell hydrogen products in small installments and offer loans at interest rates. Power purchase agreements (PPA) and PPPs offer Independent Power producers (IPPs) and private businesses the privilege to work on large projects providing them with knowledge, skills, and financial support. All this can lead to upscaling hydrogen projects [

73]. To promote PPAs in SSA, for the development of the green Hydrogen Economy, there is a need to draw a new commercial structure, strengthen the regulatory environment, and set up a competitive procurement framework, alongside comprehensive planning. This will help to tackle financial risks related to political instability, legal uncertainty, and currency fluctuations that threaten the attractiveness of the PPAs [

74,

75].

5.4. Engagement of Private and Public Partners – Businesses, Policy Makers

To upscale hydrogen technology on the African continent, it is vital to support the capacities and skills of market enablers and gamers. It is required of policymakers to create more effective and evidence-based regulations that favor a market environment for scaling up hydrogen technology. On the other hand, project developers, financiers, and equipment producers may need training to build capacity. Therefore, there is a preference for the potential to enhance skills at the country and regional levels for each renewable strength market enabler and gamer. Policymakers need to call upon global financing establishments to offer financing mechanisms to facilitate non-public sectors globally in hydrogen projects [

76].

5.5. Enhance Hydrogen Policies that support Green/ Environmental

To scale up hydrogen energy production, it’s essential to establish policies and standards that encourage its adoption. To date, national and international policies have been put in place to support renewable energy technologies by many countries globally

There is a need to have policies that encourage IPPs in place in SSA [

77]. For instance, in SADC, institutions like the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP) and the Regional Electricity Regulators Association of Southern Africa (RERA) must be given powers to come up with such policies [

78]. Policy successes can be combined and adapted to the local, national, and regional situation. At a national level, hydrogen energy development policies should include regulation measures, such as equipment standards, subsidies, and financial incentives, like feed-in tariffs that are explicit to hydrogen production, with clear roll-out strategies and agreements between governments and the private sectors. Policies must be evaluated by considering how they impact the environment and enhance cost-effectiveness, distributional aspects, institutional feasibility, and suitability. Policy measures that need to be implemented at regional and sub-regional levels include focused use of emission targets and trading systems, technology cooperation, and financial systems like the FDI [

79].

5.6. Institutionalization and Knowledge Dissemination

Skills development through training initiatives and workshops help share knowledge, and technical skills to bring up experts, entrepreneurs, and SMEs. These training programs help with hydrogen energy integration and resource capacity assessment. There is a need for developing countries to learn skills and techniques from developed countries to avoid making mistakes and failing. Exceptional levels of technical labor in business development, manufacturing, and overall management are required. The public sector needs enough skilled manpower to drive and sustain the technology within the region [

80]. The inclusion of hydrogen technologies in the school curriculum from early levels to tertiary levels helps in spreading awareness and market transformation, thereby achieving hydrogen energy institutionalization. Furthermore, providing a form of certification for organizations involved in hydrogen technologies can increase the uptake and offer incentives to certified companies [

81,

82].

Establishing sub-regional hydrogen hubs would provide remote communities with access to reliable hydrogen energy. Help centers would be an important feature to train people and communities on hydrogen energy and its importance through capacity building [

81,

83]. Digital platforms such as website images and video content, blog posts, eBook reviews, and customer testimonials can be channels for knowledge dissemination and public sensitization. These platforms help provide a central place to share ideas, knowledge, and research projects, to mention a few, on hydrogen energy. Through these platforms, partnerships with other countries that are successful and experienced in hydrogen energy can be built [

84].

5.7. Standard Operating Procedure (SOPs)

Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) is a well-laid down procedure, usually in the form of a document, video, etc. which is specific to any firm’s operations and describes in detail the critical activities needed to complete the tasks without neglecting the country-specific set industry regulations [

85]. Using the best procedures for hydrogen projects helps in scaling up the technologies. Setting up standard operating procedures and keeping to best practices can help in upscaling and hydrogen development acceptance in SSA. These standards help to describe how to perform tasks and activities. One can easily follow these rules and know what needs to be done correctly. That leaves room for no errors producing the best outcomes, thereby increasing project implementation efficiency. Procedures also enhance safety, which can reduce incidents, leading to investor and consumer confidence [

86].

While hydrogen production processes require a lot of energy, there is a need to keep the carbon dioxide levels as low as possible or even capture or store it for carbon sequestration if fossil fuels are used alongside renewable electricity in the supply chain and to compensate for it fossil fuels are used alongside non-carbon electricity. This will comprise the entire hydrogen supply chain network, including production methods, transport methods, and downstream hydrogen distribution and applications. These parts of the supply chain network can be certified individually or entirely to help owners gain independent and international recognition concerning hydrogen energy’s climate neutrality [

87]. Further, Imasiku et al. explain that the existing gap in today’s climate governance system suggests that a more aggressive business approach of adopting the renewable energy/ green energy certifications (REC certification) system should be adopted as a global criterion for awarding business opportunities [

88]. Despite all these standard procedures and other essential scaling-up strategies, the hydrogen economy opportunities come with risks.

6. Hydrogen Economy: Risks and Opportunities

Hydrogen energy development needs reliable offtake agreements in strategic sectors like ammonia production, the refinery sector, energy production, and transport sectors. To finance low-carbon technologies like green hydrogen projects requires an inventory analysis of the different risks associated with that location of investment. This is one of the key indicators for desirability to finance such a project by financing institutions [

89,

90].

Since a readily available market already exists for ammonia, there is a need to propose many initiatives around ammonia. Ammonia has many desirable characteristics that indicate that it can be used as a medium to store hydrogen as liquid anhydrous ammonia (NH3) which can be easily transported in fuel tank vehicles [

91]. The transport or mobility sector also offers enormous potential, especially in providing fuel for specialty vehicles. Besides identifying the potential offtake products, there is a need to establish offtake structures to ensure that the market is secure and guarantees future revenue. Most financiers would be comfortable having these offtake agreements or structures negotiated well in advance between the producer and the buyers so that firstly, shareholder value is established among all stakeholders and second to realize the value of the investment [

92,

93]. Financers will be evaluating the entire value chain network before building or concluding an investment plan [

9].

6.1. Emerging offtake structures

In sub-Saharan Africa, where hydrogen energy is not currently used at any scale, establishing offtake structures can be challenging to finance initially, but possible to pilot and then upscale at a later stage. For instance, it is easier for countries in developed nations to know how much hydrogen is needed at specific locations for refueling trains and buses in the transport sector [

7,

94].

Even if project financing is feasible, it will only become viable once infrastructure plans are supported by the government to ensure that appropriate fuel-cell trucks and hydrogen refueling infrastructure are put in place. Although these structures are highly applicable in the power sector, areas with high renewable resources make the hydrogen projects more appealing because conventional electricity is already in short supply [

93].

Although few projects are being implemented in sub-Saharan Africa, several projects have been proposed to use hydrogen in existing coal-fired power plants in South Africa and use green hydrogen as feedstock in projects like H2Atlas Africa [

10], Green-LFG, and green hydrogen, H2.SA project [

95], [

96,

97]. Further, key industries like steel and concrete making are good examples of such reliable offtake arrangements.

6.2. Financing Risks

The appropriate standard for project financing is a long-term, fixed-cost offtake contract with a public buyer. While the power sector and the transportation sector may increase the chances of having early hydrogen energy development opportunities signed up, many offtake structures will rely on corporate off-takers, with higher credit risks. Although hydrogen production is favored by factors like having the electrolyzer near the client to be serviced, green hydrogen investment is still considered to be a risky investment by financiers given a limited track record of electrolyzer deployment [

98,

99].

The financing agents will likewise be focused on the risk of the technology [

100]. Even though electrolysis technology has existed for quite a while, given the limited deployment evidence, financing agents will cautiously look at the manufacturing sector and engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) guarantees [

93,

101].

While there is an enormous increase in the number of firms signing partnership agreements, to leverage other firms’ good monetary records, lending institutions often also demand major maintenance reserves. Such security will be costly for first-mover projects.

6.3. Hydrogen Marketing, Regulatory & Technology Risks

Government backing will be fundamental to getting the green hydrogen market going. Backing for electrolyzer development will be vital but may be deficient if it is the only focus for hydrogen marketing [

102].

Like the policy deficit on hydrogen energy, the hydrogen energy market is still unclear compared to the previous evolutions for renewables - wind and solar. Hydrogen has not yet penetrated the industry for large-scale use like other energy forms [

101]. The provision of economic incentives by Governments in sub-Saharan Africa in the transport sector would help provide appropriate hydrogen transportation standards using pipelines, ships, and trucks [

95,

100].

In summary, it is preferred that financial institutions adopt a multi-disciplinary approach while leveraging on the firms’ technical capacity to finance the oil and gas, power, infrastructure, transport, and mining projects (1) to analyze hydrogen project risks and (2) to structure the financing mode. These institutions have increased the liquidity rate for sustainable projects, by reallocating finances meant for fossil fuels to sustainable energy projects [

1]. This posits several financing risks.

6.4. Hydrogen Financing Risks in sub-Saharan Africa

The project risks associated with hydrogen energy finance can be identified, mitigated, and addressed to accommodate lenders and key project stakeholders. This points to the fact that projects that use technologies that have been tested and proven to decrease both the project and operational costs, thereby making project financing more attractive to potential equity investors and financiers. The key issue in the offtake structure is that most lenders get attracted to projects whose projected revenue can offset the debt service and the operating expenses of the loans [

101,

103,

104].

The following

Table 2 shows this study’s risk assessment for green hydrogen deployment in sub-Saharan Africa.

Keynote: Risk Description

| Risk Score |

Rating |

Description |

| 0 - 3 |

Low |

Remedial action discretionary |

| 4 - 6 |

Medium |

Remedial action is to be taken at the appropriate time |

| 7 - 9 |

High |

Remedial action to be given high priority |

| 10 - 16 |

Very High |

Operation is not permissible. Immediate action necessary |

Where the total maximum obtainable score or worst-case scenario is a score of 128. Therefore, a score of 44 gives an average percentage of 34.37% (rounding up = 35%)

Table 2 shows the project risk, threats, and opportunity matrix for any potential green hydrogen project in SSA. It shows that the risk factor for hydrogen economy development in SSA is less than 50% of the worst-case scenario.

Table 2 shows a calculated risk factor of about 35% (5.6 scores on the risk description). The following are the risk matrix implications on green hydrogen in SAA:

The implications of project oversights during the implementation and commissioning phase (e.g., capital cost exceeded) with a risk score of 6 is that potential budget overruns and delays in project completion exist and this could affect the overall timeline and financial stability of the project.

The implications of the funding/ loan availability having a low-risk score of 3 is that there are some funding issues that suggest that financial backing is stable and reliable.

A high electrical grid connection issues risk Score of 8 implies that significant risk of problems of connecting to the electrical grid exist, which could lead to operational delays and increased costs.

The risk score of 5 for high pressure and large quantity hydrogen storage implies that a moderate risk associated with storing hydrogen exists but requires careful management to prevent accidents and ensure safety.

Hydrogen transportation using pipelines or trucks has a high-risk score of 7 implies that high risk in transporting hydrogen, which could involve logistical challenges and safety concerns.

Like any location globally, pandemics or natural calamities & Climate Change are mostly inevitable. The average risk score of 5 implies that moderate risk from external factors like pandemics or natural disasters, which could disrupt operations and supply chains are expected.

Political instability/ change of governments with a risk score of 7 implies that high risks prevail due to potential political changes, and this could affect regulations, policies, and overall project stability.

Other risks like security due to war have a low score of 3 and this implies that there is a low risk of security threats like war and that a relatively stable geopolitical environment exists.

In summary, with a 5.6 risk score, the investment rating is medium, less risky, and implies that remedial action will only be taken at an appropriate time. The risk description shows that any score up to nine (9) is still tolerable while keeping all hydrogen energy developers and investors informed about the associated risks. The score points to either high priority or informs that the investment is not feasible or allowable. With none of the risk factors categorized as a very high factor in

Table 2, shows that the opportunities for hydrogen energy investment outweigh the threats in SSA is viable. The total risk score of 44 indicates a moderate to high overall risk level for hydrogen energy project development in SSA. The highest risks are associated with electrical grid connection issues, hydrogen transport, and political instability. To address the issues raised, the mitigation strategies should focus on these high-risk areas to ensure project success and stability.

7. Conclusions

Green hydrogen is produced using renewable energy sources like solar and wind. Because of its abundant existence and zero emissions when burnt, it has often been described as the fuel of the future globally.

Therefore, financing green hydrogen projects in SSA will need strong partnerships between the financial institutions, the industry, and policymakers. Furthermore, financial resource availability is essential to hydrogen energy development and a possible game-changer concerning energy transition from fossil-fuel-based economies to green economies. Our review article shows that some key considerations for green hydrogen energy development in SSA, include having good green energy transition finance, green energy financing mechanisms, and hydrogen energy scaling-up strategies without neglecting the risks associated with the exploitation of the opportunities that come with its uptake.

In sub-Saharan Africa, many new innovative opportunities will arise when financing the green economy transition. Green economic transition will develop new technologies to minimize or avoid the emission of greenhouse gases that cause climate change. This would help address climate action through sustainable energy development. Further, green economy transition and financing are feasible if sound policies exist. This would allow governments to develop strategies that build responsive financial investment systems that are sustainable and in line with the UN Sustainable Development Agenda on energy transition and help close the gap between the current Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and the Paris Agreement temperature target requirements.

Some important financing mechanisms that can enhance green hydrogen finance in SSA include Loans, Grants, Bonds, subsidies, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), venture capital, and Public Private Partnership (PPP). However, those that have been widely used in West Africa and Southern Africa are the Department of Financial Institutions (DFIs), governments, Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) which finance green projects through local commercial banks and the public sector (governments), and reputable private institutions and NGOs. Typical African financing development banks include the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) and African Development Banks (AfDB). Other African initiatives for green finance include the European Union and UN Agencies, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the African Union, SADC, and ECOWAS.

Financing mechanisms such as Loans, Grants, and subsidies help create resilience against climate change because they help SSA address or build mitigation and adaptation projects in the region. Due to the high risk of climate change impacts in most SSA countries, some green financers now provide green bonds as a critical financial instrument. However, the success of green bonds will depend on improved debt management.

Green finance can also further be enhanced through strong partnerships between public and private investors. Such partnerships can help deliver climate-resilient and scale-up infrastructure, partnerships, integrating gender, de-risking, and mobilizing private sector finance for long-term progress towards green sustainability.

Some scaling-up strategies that would enhance hydrogen energy production include Green Public Procurement and sustainable public procurement (SPP), financial investments of small and large-scale projects, Power Purchase Agreements, engagement of private and public partners, enhanced hydrogen policies that support green finance, the institutionalization of hydrogen energy, knowledge dissemination, establishment of regional-hub, and engaging in Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs).

These strategies would help improve the tender processes, and introduce green financing, green loans, and financial incentives. Further, government engagement using PPPs can help project developers, financiers, and equipment producers build their capacity. The enhancement of hydrogen policies that support green finance is also necessary for scaling up hydrogen energy development especially concerning regulation measures for equipment standards, subsidies, and financial incentives such as feed-in tariffs, public-private agreements, etc. Apart from policy, there is also a need to institutionalize hydrogen energy skills development through training initiatives and workshops to share knowledge and technical skills to bring up experts, entrepreneurs, SMEs, and overall youth empowerment. Since hydrogen energy is still not so widely known, knowledge dissemination through digital platforms including social media profiles, website images and video content, blog posts, eBooks, Facebook, WhatsApp, LinkedIn, etc. would help enhance stakeholder awareness. The dissemination exercise can also be enhanced by setting up an information hub to help train people or communities on hydrogen. Lastly, establishing standard operating procedures is also necessary for ensuring that all small and large projects adhere to internationally acceptable operating standards.

However, Green hydrogen financing does not come without any challenges and risks. Some of these risks include poor project delivery by developers, less availability of funding/loans, poor electrical grid infrastructure, road network and transmission conduits like pipelines, natural calamities and pandemics, political instability, and other security risks like war, to mention only a few.

To reduce green finance and investment risks from the current 35%, greater effort is needed to unlock green energy finance by governments and establish specific financing mechanisms at national and international levels alongside de-risking project implementation. The project risks associated with hydrogen energy finance are supposed to be identified, mitigated, and addressed in collaboration with financiers and other stakeholders. This would create some form of investor confidence. Further, involving strategic partners who have tested the green hydrogen technology would also assist build the confidence of the financiers in the perspective of project viability. Governments in SSA need to establish offtake structures or agreements between the producer and the buyers to ensure that the market is secure and guarantees future revenue.

Since green hydrogen production from renewable resources like solar, wind, and water is considered to have a long-term sustainable supply, green hydrogen should be part of greenhouse gas mitigation options and energy transition solutions in SSA. However, this transition cannot occur unless governments in SSA improve the policy and regulatory environment and create market-based mechanisms to incentivize businesses by mobilizing multilateral and bilateral financing for green projects. These incentives would help reduce the cost of green hydrogen production and make it easier to up-scale. This can be achieved if governments adopt green procurement practices and set them as a compulsory requirement in tender specifications.

Investing more into research and innovation for the development of electrolyzers like Hydrogen South Africa (HYSA) in South Africa is key to the structuring and financing of the projects in SSA.

The significance of financing green hydrogen is that it can serve as an enabler for climate resilience and transitioning for SSA from a fossil fuel-based economy to a green economy. With abundant renewable resources alongside unlocking sustainable green financing mechanisms and suitable policies, SSA can gain a leading position concerning hydrogen energy supply globally. Apart from green hydrogen, other hydrogen-based fuels like methane and ammonia can also play a significant role in providing clean energy. This study helps unlock sustainable green financing mechanisms for SSA.

Future research work is recommended around investigating the development and improvement of electrolyzers and other clean technologies that are suitable for the renewable energy resources in SSA, focusing on reducing costs and enhancing efficiency, particularly in the context of Sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, green hydrogen infrastructure creation and optimization for green hydrogen production, storage, and transportation can also be done to address the technical and logistical challenges that have been identified in this study.

Overall, the business climate for green hydrogen development shows a medium investment rating which is less risky, and manageable since remedial action can be taken at an appropriate time. To address the issues raised, the mitigation strategies should focus on these high-risk areas to ensure project success and stability. The highest risks are associated with electrical grid connection issues, hydrogen transport, and political instability. An overall score of 44 indicates a moderate to high overall risk level for hydrogen energy project development in SSA.

Acknowledgments

This research article writing was supported by the Southern African Science Service Centre for Climate Change and Adaptive Land Management (SASSCAL) and West African Science Service Centre for Climate Change and Adaptive Land Management (WASCAL), both African partners to the Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH in Germany, on the Atlas of Green Hydrogen Generation Potential (H2Atlas - Africa) which is part of the Go-Green-Go African Initiative of the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the framework of which the research has been funded.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- AfDB, “Potential for Green Banks & National Climate Change Funds in Africa - Scoping Report,” 2021.

- M. Noussan, P. P. M. Noussan, P. P. Raimondi, R. Scita, and M. Hafner, “The Role of Green and Blue Hydrogen in the Energy Transition - A Technological and Geopolitical Perspective,” Sustainability, vol. 19, no. 298, 2021. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum, “Reducing costs: The key to leveraging green hydrogen on the road to net zero.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/01/green-hydrogen-the-last-mile-in-the-net-zero-journey/.

- IPCC, “Emissions Trends and Drivers,” in Climate Change 2022 - Mitigation of Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, 2023, pp. 215–294. [CrossRef]

- M. Raman, “Climate Change Battles in Paris: An Analysis of the Paris COP21 and the Paris Agreement.” Accessed: Oct. 22, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.southcentre.int/question/climate-change-battlesin-paris-an-analysis-of-the-paris-cop21-and-the-paris-agreement/.

- World Bank, “Sources of Financing and Intercreditor Agreement.” Accessed: Oct. 22, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/financing/sources.

- IRENA, Hydrogen from Renewable Power: Technology outlook for the energy transition, no. September. 2018.

- OECD, “Infrastructure Financing Instruments and Incentives,” OECD - Secretary-General, pp. 1–74, 2015.

- Ivan Pavlovic, “Green and Sustainable Financing green hydrogen’s development: clearing the hurdles,” 2021.

- H2Atlas Africa, “H2Atlas Africa Tool.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.h2atlas.de/en/hydrogen-tool.

- UNEP, “Green Financing.” Accessed: Feb. 24, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.unep.org/regions/asia-and-pacific/regional-initiatives/supporting-resource-efficiency/greenfinancing.

- S. Anstis et al., “Green Economy for Sustainable Development: Compendium of Legal Best Practices,” 2012.

- K. Imasiku, V. K. Imasiku, V. Thomas, and E. Ntagwirumugara, “Unpacking Ecological Stress from Economic Activities for Sustainability and Resource Optimization in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability,” Susstainability, vol. 12, no. 9, pp. 1–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- New Climate Economy, “Better Growth Better Climate,” 2014.

- N. Stern, “Financing an inclusive green economy transition,” 2018.

- M. Hauman and T. Hassain, “Green finance in Africa,” White & Case. Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=9ce1ac73-58ee-46ca-a6e9-bd61694a03a7.

- D. Chirambo, “Addressing the renewable energy financing gap in Africa to promote universal energy access: Integrated renewable energy financing in Malawi,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 62, pp. 793–803, 2016. [CrossRef]

- UNEP, “Green Finance for Developing Countries,” United Nations Environment Programme, no. May 2016.

- H. Gujba, S. H. Gujba, S. Thorne, Y. Mulugetta, K. Rai, and Y. Sokona, “Financing low carbon energy access in Africa,” Energy Policy, vol. 47, no. SUPPL.1, pp. 71–78, 2012. [CrossRef]

- IRENA, “Policies and Finance Deployment in Renewable Energy in SSA,” 2024. Accessed: Sep. 06, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2024/Jul/IRENA_SS_Africa_policies_finance_RE_2024.

- S. Okonkwo, “Investors are failing African entrepreneurs — it’s time for a change,” GreenBiz, p. https://www.greenbiz.com/article/investors-are-fai, 2021.

- M. N’Guessan, “A Review of Funding Sources Available for Promoting Renewable Energy in Africa,” no. September 2012.

- GMDB, “Joint report on multilateral development banks’ climate finance 2019,” p. 56 pp, 2020.

- AFDB, “The African Development Bank pledges US$ 25 billion to climate finance for 2020-2025, doubling its commitments.” Accessed: Nov. 21, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/the-african-development-bank-pledges-us-25-billion-to-climate-finance-for-2020-2025-doubling-its-commitments-19090.

- UNHCR, “WHAT IS CARBON FINANCING?” Accessed: Jul. 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.unhcr.org/55005b069.pdf.

- World Bank, “Climate Change Action Plan (2021-2025) Infographic.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2021/06/22/climate-change-action-plan-2021-2025.

- IPCC, “Global Warming of 1.5°C: Headline Statements from the Summary for Policymakers,” 2018.

- UNWTO, “Transforming Tourism for Climate Action,” Climate Action.

- K. Imasiku, “Organizational Insights, Challenges and Impact of Sustainable Development in Developing and Developed Nations,” in Sustainable Organizations - Models, Applications, and New Perspectives, J. C. Sánchez-García and B. Hernandez-Sanchez, Eds., Intechopen, 2021, ch. 1. [CrossRef]

- G. Savvidou and C. Trisos, “This is how much investment is needed to mitigate climate change across Africa,” World Economic Forum, 2021.

- M. Bowman and S. Minas, “Resilience through interlinkage: the green climate fund and climate finance governance,” Climate Policy, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 342–353, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Goering and T. R. Foundation, “IMF: Why we must increase support for developing countries in the fight against climate change,” World Economic Forum, 2021.

- C. Watson, O. C. Watson, O. And, and H. Liane Schalatek, “Climate Finance Regional Briefing: Sub-Saharan Africa,” Climate Funds Update, 2021.

- S. Nakhooda, A. S. Nakhooda, A. Caravani, and N. Bird, “Climate Finance Policy Brief: Climate Finance in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Overseas Development Institute, no. November, pp. 1–8, 2011.

- G. Savvidou and C. Trisos, “This is how much investment is needed to mitigate climate change across Africa,” World Economic Forum, 2021.

- G. Savvidou, A. G. Savvidou, A. Atteridge, K. Omari-Motsumi, and C. H. Trisos, “Quantifying international public finance for climate change adaptation in Africa,” Climate Policy, vol. 21, no. 8, pp. 1020–1036, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Ngwenya and M. D. Simatele, “The emergence of green bonds as an integral component of climate finance in South Africa,” S Afr J Sci, vol. 116, no. 1–2, pp. 10–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Ngwenya and M. D. Simatele, “Unbundling of the green bond market in the economic hubs of Africa: Case study of Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa,” Dev South Afr, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 888–903, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Ngwenya and M. D. Simatele, “The emergence of green bonds as an integral component of climate finance in South Africa,” S Afr J Sci, vol. 116, no. 1–2, pp. 10–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. M. Fonta, E. T. W. M. Fonta, E. T. Ayuk, and T. van Huysen, “Africa and the Green Climate Fund: current challenges and future opportunities,” Climate Policy, vol. 18, no. 9, pp. 1210–1225, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Watson, O. C. Watson, O. And, and H. Liane Schalatek, “Climate Finance Regional Briefing: Sub-Saharan Africa,” Climate Funds Update, 2021.

- P. Shipalana, “Green Finance Mechanisms in Developing Countries: Emerging Practice Palesa Shipalana Recommendations,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://about.jstor.org/terms.

- Cabré, Muñoz; et al. , “Expanding Renewable Energy for Access and Development Global Development Policy Center,” 2020. Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2020/11/GDP_SADC_Report_EN_Nov_16.pdf.

- Green Climate Fund, “Report of the Green Climate Fund to the Conference of the Parties and guidance to the Green Climate Fund (for 2020 and 2021),” vol. 15748, no. November 2021.

- M. Muñoz Cabré et al., “Expanding Renewable Energy for Access and Development,” Boston, 2020.

- Serdeczny et al., “Climate change impacts in Sub-Saharan Africa: from physical changes to their social repercussions,” Reg Environ Change, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 1585–1600, 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Marbuah, “Scoping the sustainable finance landscape in Africa: The case of green bonds,” no. July, pp. 1–40, 2020.

- World Bank, “What are Green Bonds?” 2015.

- B. Boulle, “How Greeen Bonds Can Support South Africa’s Energy Transition,” Climate Bonds Initiative, pp. 1–19, 2021.

- R. M. Quazi, “Investment Climate and Foreign Direct Investment: A Study of Selected Countries in Latin America,” GLOBAL JOURNAL OF BUSINESS RESEARCH, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 1–14, 2006.

- S. Smith, “‘Restrictive Policy toward Multinationals: Argentina and Korea,’ Case Studies in Economic Development,” 2nd Edition, pp. 178–189, 1997.

- R. M. Quazi, “Investment Climate and Foreign Direct Investment: A Study of Selected Countries In Latin America,” GLOBAL JOURNAL OF BUSINESS RESEARCH, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 1–14, 2006.

- UNCTAD, “World Investment Report 2020,” 2020.

- Sovereign, “Foreign Direct Investment toAfrica Faces Strong Headwinds.

- C. Mason, “Venture Capital,” International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (Second Edition), Elsevier, no. 2, pp. 155–160, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Abor, E. K. J. Y. Abor, E. K. Agbloyor, and H. Issahaku, “The Role of Financial Markets and Institutions in Private Sector Development in Africa,” Extending Financial Inclusion in Africa, pp. 61–85, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Randjelovic, A. R. O’Rourke, and R. J. Orsato, “The emergence of green venture capital,” Bus Strategy Environ, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 240–253, 2003. [CrossRef]

- L. Lin, “Venture Capital in the Rise of Sustainable Investment,” OBLB.

- IFC, “Disruptive Technologies and Venture Capital.

- Alloisio, “The role of PPPs in the energy transition infrastructure financing in Sub-Saharan Africa,” no. June, pp. 123–125, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Haddad, C. Günay, S. Gharib, and N. Komendantova, “Imagined inclusions into a ‘green modernization’: local politics and global visions of Morocco’ s renewable energy transition,” Third World Q, vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–21, 2022. [CrossRef]

- AfDB, “Climate Finance Newsletter,” African Development Bank, no. N 47 April, pp. 1–5, 2021.

- D. Hadebe, A. Hansa, C. Ndlhovu, and M. Kibido, “Scaling Up Renewables Through Regional Planning and Coordination of Power Systems in Africa—Regional Power System Planning to Harness Renewable Resources and Diversify Generation Portfolios in Southern Africa,” Current Sustainable/Renewable Energy Reports, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 224–229, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Hydrogen Council, “Hydrogen scaling up: A sustainable pathway for the global energy transition,” Hydrogen scaling up: A sustainable pathway for the global energy transition, no. November, p. 80, 2017.

- B. P. Blewer, T. Khanberg, H. Huglen, and M. Gonzalez, “Multi-coloured Hydrogen in the Global Energy Transition,” 2021.

- MIT Technology Review, “Scaling green hydrogen technology for the future.” Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/06/18/1092956/scaling-green-hydrogen-technology-for-the-future/.

- S. Wang, A. Lu, and C. J. Zhong, “Hydrogen production from water electrolysis: role of catalysts,” Nano Converg, vol. 8, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hasanbeigi, R. Becqué, and C. Springer, “Curbing carbon from consumption: the Role of Green Public Procurement,” 2019.

- S. Lundberg and P. O. Marklund, “Green public procurement and multiple environmental objectives,” Economia e Politica Industriale, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 37–53, 2018. [CrossRef]

- ESCWA, “Policy Options for Promoting Green Technologies in the Arab Region,” Beirut, Lebanon, 2019.

- T. Stoffel, C. Cravero, A. La Chimia, and G. Quinot, “Multidimensionality of sustainable public procurement (SPP)-exploring concepts and effects in Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 11, no. 22, pp. 1–24, 2019. [CrossRef]

- World Bank, “Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) and Energy Purchase Agreements (EPAs).” Accessed: Mar. 25, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-privatepartnership/sector/energy/energy-power-agreements/power-purchase-agreements.

- UNF, “Increasing Global Renewable energy Market Share- Recent Trends and Perspectives,” Beijing, 2005.

- IEA, “Scaling-up Energy Investments in Africa for Inclusive and Sustainable Growth Report of the Africa-Europe High-Level Platform for Sustainable Energy Investments in Africa,” 2019.

- Eberhard, K. Gratwick, E. Morella, and P. Antmann, “Independent Power Projects in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from Five Key Countries,” 2016. [CrossRef]

- IPAP, “Economic Sectors, Employment and Infrastracture Development Cluster,” Pretoria, 2018.

- K. Imasiku, F. Farirai, J. Olwoch, and S. N. Agbo, “A policy review of green hydrogen economy in Southern Africa,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 23, pp. 1–17, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Montmasson-Clair and B. Deonarain, “Regional Integration in Southern Africa: A Platform for Electricity Sustainability,” Pretoria, 2017.

- IRENA, Green hydrogen: A Guide to Policy making, vol. 2. Abu Dhabi: IRENA, 2016.

- S. Hart, “Leveraging Training and Skills Development in SMEs Leveraging Training and,” 2012.

- New Era, “Unam leads Green Hydrogen Research Institute,” UNAM, 2021.