1. Introduction

The prostate gland, a key male accessory reproductive organ, produces prostatic fluid essential for sperm motility and fertilization [

1]. Its function and structural integrity are regulated by autonomic innervation from the major pelvic ganglion, which integrates sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers from the hypogastric and pelvic nerves, originating from the T13–L2 and L6–S1 spinal segments, respectively [

2]. Disruption of this neural input significantly alters prostate physiology, leading to structural and functional changes [

3,

4].

Histologically, the prostate consists of secretory alveoli lined by pseudostratified epithelium supported by connective tissue and smooth muscle. In male rats, the prostate includes ventral, dorsal, and lateral lobes with distinct features: the ventral lobe has small alveoli with abundant invaginations lined by columnar epithelial cells (~10–12 μm height), whereas the dorsolateral lobes contain cuboidal epithelial cells with centrally or basally located nuclei [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Denervation of the hypogastric and pelvic nerves can induce epithelial atrophy, loss of nuclear polarity, and tissue disorganization, underscoring the essential role of autonomic innervation in prostate architecture maintenance [

4].

Hormonal regulation is equally crucial for prostate development and function. testosterone and prolactin are key regulators, promoting epithelial proliferation, prostatic fluid synthesis, and cellular growth [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Neural disruption can alter hormonal levels; denervation has been shown to suppress testosterone release and reduce androgen receptor expression, although prolactin receptor expression remains unchanged in the prostate and major pelvic ganglion [

13,

14]. Such disruptions mimic age-related hormonal changes, including reduced testosterone and elevated prolactin levels, which are associated with conditions like benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer [

15,

16,

17].

The immune response also plays a critical role in prostate health and disease progression. Neural denervation can trigger inflammation, leading to increased infiltration of leukocytes, T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and macrophages into prostatic tissue [

18,

19,

20]. This inflammatory response is associated with elevated pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, and IL-10 [

17,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Chronic inflammation disrupts the balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis, driving tissue remodeling and contributing to the development of BPH and prostate cancer [

17,

21,

26]. Thus, a complex interplay exists between neural regulation, hormonal control, and immune responses within the prostate. We hypothesize that autonomic denervation of the major pelvic ganglion, or absence of autonomic input, alters prostate histology, hormonal secretion, and immune dynamics, fostering inflammation and pathological changes. This study aims to investigate the effects of major pelvic ganglion denervation on prostate histology, serum prolactin and testosterone levels, and immune responses, including cytokine profiles and immune cell infiltration. Understanding these mechanisms will provide insights into the neuroimmune and neuroendocrine regulation of prostate pathologies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Twenty-six male Wistar rats (300–350 g) were housed in pathogen-free plexiglass cages (50 × 30 × 20 cm) at 22–25 °C with a reverse 12:12 h light-dark cycle (lights off at 8:00 am). Animals had ad libitum access to purified water and standard rodent chow. Experimental procedures were approved by the Internal Committee for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals (CICUAL) of the Brain Research Institute at Universidad Veracruzana (registration no. 2021-016-a), following the Mexican Official Standard NOM-062-ZOO-1999.

2.2. Experimental Groups and Surgical Procedures

Rats were randomly assigned to one of four groups: Sham-operated (n = 6): Pelvic (Pv) and Hypogastric (Hg), the nerves were exposed but not transected; Pv lesion (n = 7), the bilateral transection of the pelvic nerves; Hg lesion (n = 7), the bilateral transection of the hypogastric nerves. Pv+Hg lesion (n = 6), the bilateral transection of both pelvic and hypogastric nerves.

Under deep anesthesia (sodium pentobarbital, 50 mg/kg, i.p.), the major pelvic ganglion was exposed near the prostate, and the Pv and/or Hg nerves were carefully tracked and transected as per group assignments. In the sham group, nerves were exposed but not cut. Given Pv lesions impair micturition, the bladder was manually expressed twice daily post-surgery to maintain animal health. Muscle and skin were sutured using Catgut 3-0, and animals received a single intramuscular dose of antibiotic (0.1 ml Pengesod, 1,000,000 U, Lakeside Mexico). At the study’s conclusion, nerve regeneration was ruled out upon re-examination.

2.3. Tissue Collection

Rats were euthanized with an intraperitoneal overdose of sodium pentobarbital (120 mg/kg, i.p.). Blood was collected via cardiac puncture for serum analysis. Prostate lobes (ventral and dorsolateral) were excised: right lobes for immune cell analysis and left lobes fixed in 10% formaldehyde for histological examination.

For immune analysis, tissues were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4; Sigma-Aldrich P3813) and twice with Hanks’ solution (without calcium chloride, magnesium sulfate, or sodium bicarbonate; Sigma-Aldrich H2387) to remove debris. Tissues were then placed in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco 12100-038) with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich F2442) for dissociation.

2.4. Dissociation of Prostate Tissue

Prostate tissues were minced in a Petri dish into 2–3 mm³ pieces, then were immersed in conical tubes and incubated in 5 ml of DMEM with 20% FBS. Then collagenase type IV (1 mg/ml per 100 mg tissue; Sigma-Aldrich C5138; >125 CDU/mg) was added at 37 °C for 2 hours with gentle agitation each 10 minutes.

Following incubation DNase I (0.12 mg/ml; Roche 11284932001) was added to enhance dissociation, and samples were pipetted gently for one minute. The cell suspension was filtered through a 100 μm cell strainer, centrifuged (1,500 rpm, 5 min), and erythrocytes lysed using 3 ml of 0.85% ammonium chloride for 3 minutes at room temperature. After stopping the reaction with 5 ml of cold Hanks’ solution, cells were centrifuged again, and the pellet resuspended in 1 ml of DMEM with 20% FBS. The viability was assessed using the trypan blue exclusion method, stained with a 1:1 ratio, and counted a Neubauer chamber at a 40x microscope magnification.

2.5. Quantification of Serum Interleukins, Prolactin, and Testosterone

Blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture, allowed to clot, centrifuged (3,500 rpm, 10 min) at room temperature, and serum separated and stored at −20 °C. Testosterone, prolactin, and interleukin levels (IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-10) were quantified using ELISA per the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.6. Characterization of Immune Cells

Prostate-derived single-cell suspensions (1 × 10⁵ cells/ml) were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA): Anti-CD45 BV421, Anti-CD3 BV605, Anti-CD4 PE, Anti-CD8a APC, Anti-CD19 APC Cy7, and Anti-CD11b PerCP Cy5.5. After 15-minute dark incubation at room temperature, cells were washed with PBS, centrifuged (1,500 rpm for 5 minutes), fixed in FixFacs solution (1% paraformaldehyde in PBS), protected from light and stored at 4 °C. Flow cytometry was performed using a BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and data analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

2.7. Histological Analysis

Formaldehyde (10%) fixed prostate tissues were dehydrated in graded alcohols, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm thickness in a microtome (Leica). Sections were mounted in gelatinized slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) following standard protocols: Deparaffinization: Twice in xylene (5 min each). Rehydration: Graded alcohols (100%, 96%) and water. Staining: Hematoxylin (6 min), rinse in water (30 seconds), acid alcohol differentiation (quick immersion), rinse in water (10 seconds), lithium carbonate bluing (30 seconds), rinse in water (10 seconds), eosin (4 min). Dehydration and Clearing: Ethanol (96%, 100%; 3 minutes each), ethanol/xylene (1:1; 5 minutes), and xylene (5 minutes). Then, slides were coverslipped with Permount, air-dried, and examined under a light microscope (Optisum Mic 990, Desego, México). Images were captured at 10×, 40×, and 100× magnifications, and analyzed with the TopView software.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Group comparisons of immune cell populations and serum hormone levels were analyzed using One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Interleukin levels were analyzed using unpaired t-tests. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (v10.3.1).

3. Results

Previous work from our laboratory demonstrated that axotomy of the Pv and Hg nerves induces significant alterations in prostate cytoarchitecture, accompanied by increased immune cell infiltration (27). Building on these findings, the current study provides a detailed analysis of histological, immune, and hormonal changes associated with major pelvic ganglion denervation.

3.1. Ventral Prostate

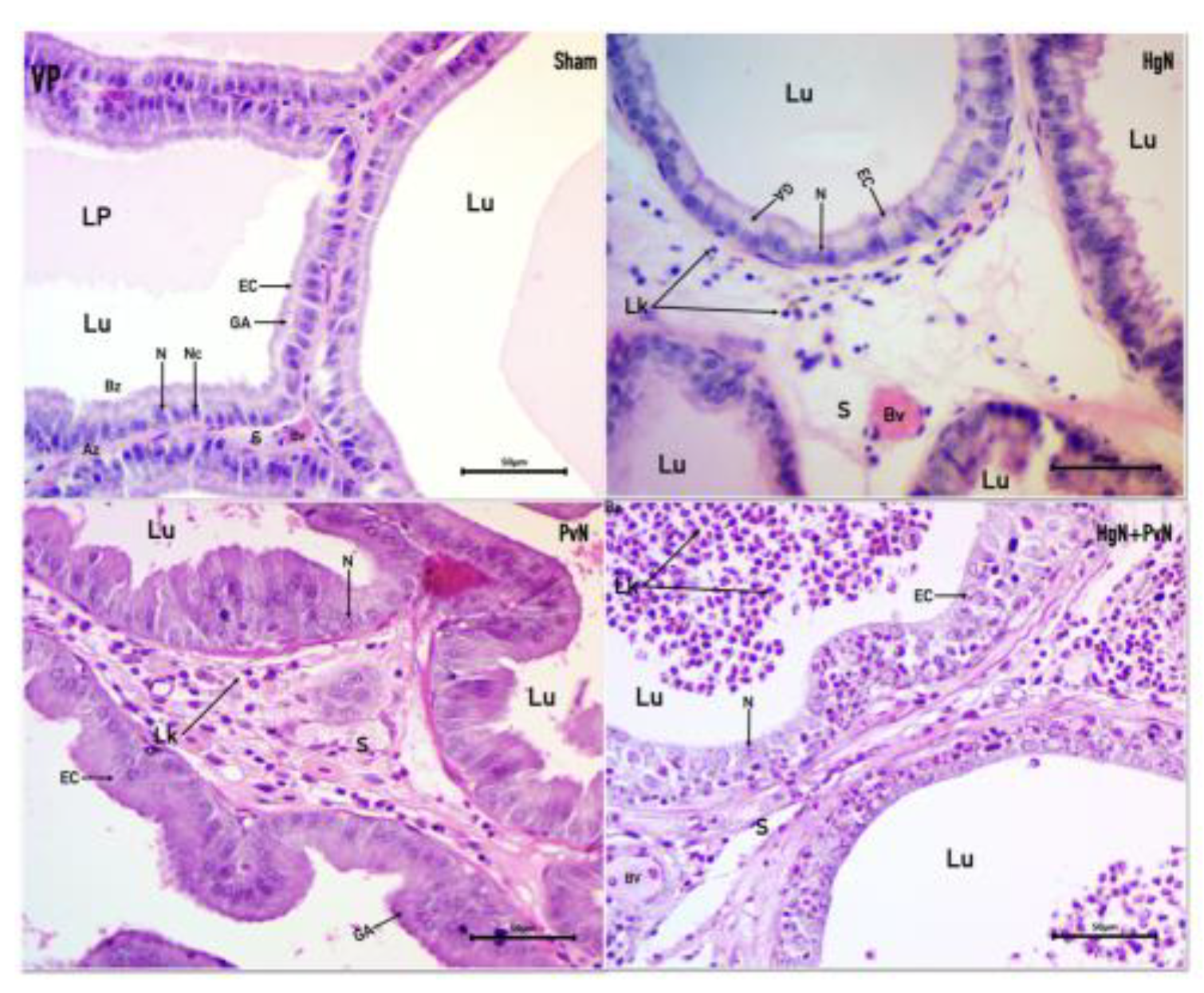

In the sham-operated group, the epithelial cells displayed characteristic features of a healthy prostate. Nuclei were positioned basally with centrally located nucleoli, and the cells were columnar, forming a pseudostratified epithelium. The Golgi apparatus was prominent and situated apically. The nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio was maintained at 1:3, the luminal space contained prostatic fluid, and the stroma exhibited a fusiform appearance indicative of normal architecture. Following

Hg axotomy, epithelial cells exhibited cuboidal morphology with nuclei that appeared round and contained evident nucleoli. The normal nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio was disrupted, and while the Golgi apparatus remained visible, the overall epithelial structure indicated atrophy. The stroma was notably abundant, containing scattered immune cells, suggesting a response to epithelial atrophy and stromal inflammation. In contrast,

Pv axotomy resulted in more pronounced alterations. Nuclei displayed anisokaryosis, with varied shapes and sizes, and nucleoli remained visible. The epithelial cells appeared disorganized, exhibiting anisocytosis with varied cell heights indicative of atypical hypertrophy. The stroma was rich in microvacuoles and immune cells, while the epithelial layer resembled squamous epithelium, consistent with an inflammatory response. Both types of axotomy induced shared pathological features, including hypochromatic nuclei, anisokaryosis, disorganized epithelial cells, fusiform stromal architecture, and significant immune cell infiltration within the stroma. Notably, the lumen lacked prostatic fluid in both cases and was infiltrated by immune cells, further highlighting the inflammatory environment (

Figure 1).

Dorsolateral Prostate

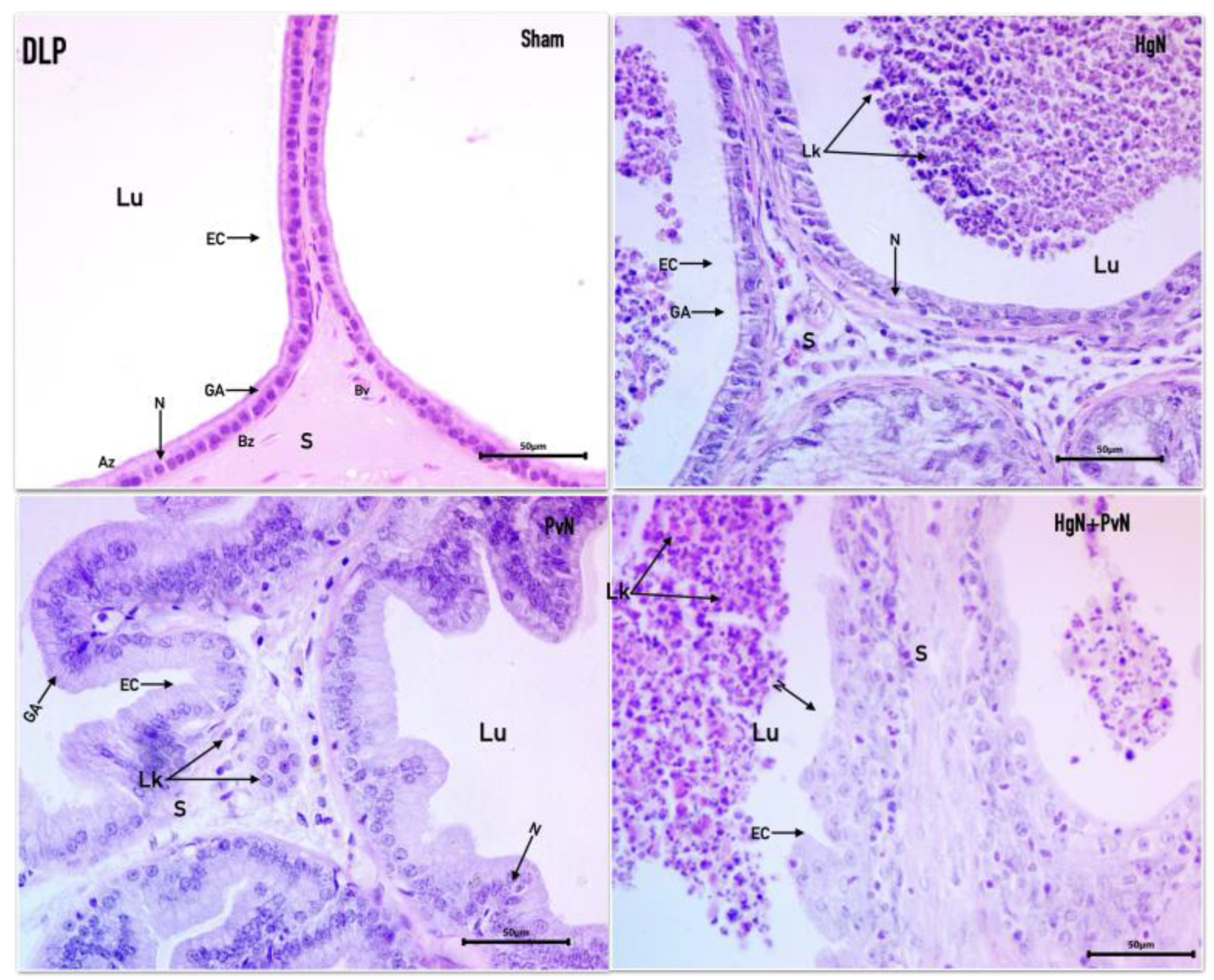

In the sham-operated group, the dorsolateral prostate exhibited a healthy epithelium composed of eosinophilic cuboidal cells and sparse stroma. Nuclei were round, basally positioned, and contained visible nucleoli, while the Golgi apparatus was prominently located apically. The overall architecture reflected normal prostate structure. Following

Hg axotomy, the epithelium retained its cuboidal morphology, and nuclei remained intact with visible nucleoli. However, the Golgi apparatus appeared reduced. Cellular debris and polymorphonuclear cells were observed in the acinar lumen, suggesting the onset of an inflammatory response despite relatively preserved epithelial integrity. In the

Pv axotomy group, the epithelium displayed marked changes, appearing basophilic with signs of hyperproliferation. Nuclei were round, basophilic, and exhibited prominent nucleoli. The epithelial layer showed a pseudostratified and hypertrophic arrangement, accompanied by abundant stroma and significant immune cell infiltration, indicative of atypical inflammatory hypertrophy. In the case of

double axotomy (Hg and Pv), the epithelial cytoarchitecture was severely disrupted. Cells were arranged in papillary and cribriform patterns, with a complete loss of normal epithelial organization. Pronounced anisokaryosis (variation in nuclear size and shape) and anisocytosis (variation in cell size) were evident, along with prominent nucleoli. The lumen contained a substantial inflammatory infiltrate, further underscoring the severe inflammatory and structural changes induced by dual denervation (

Figure 2).

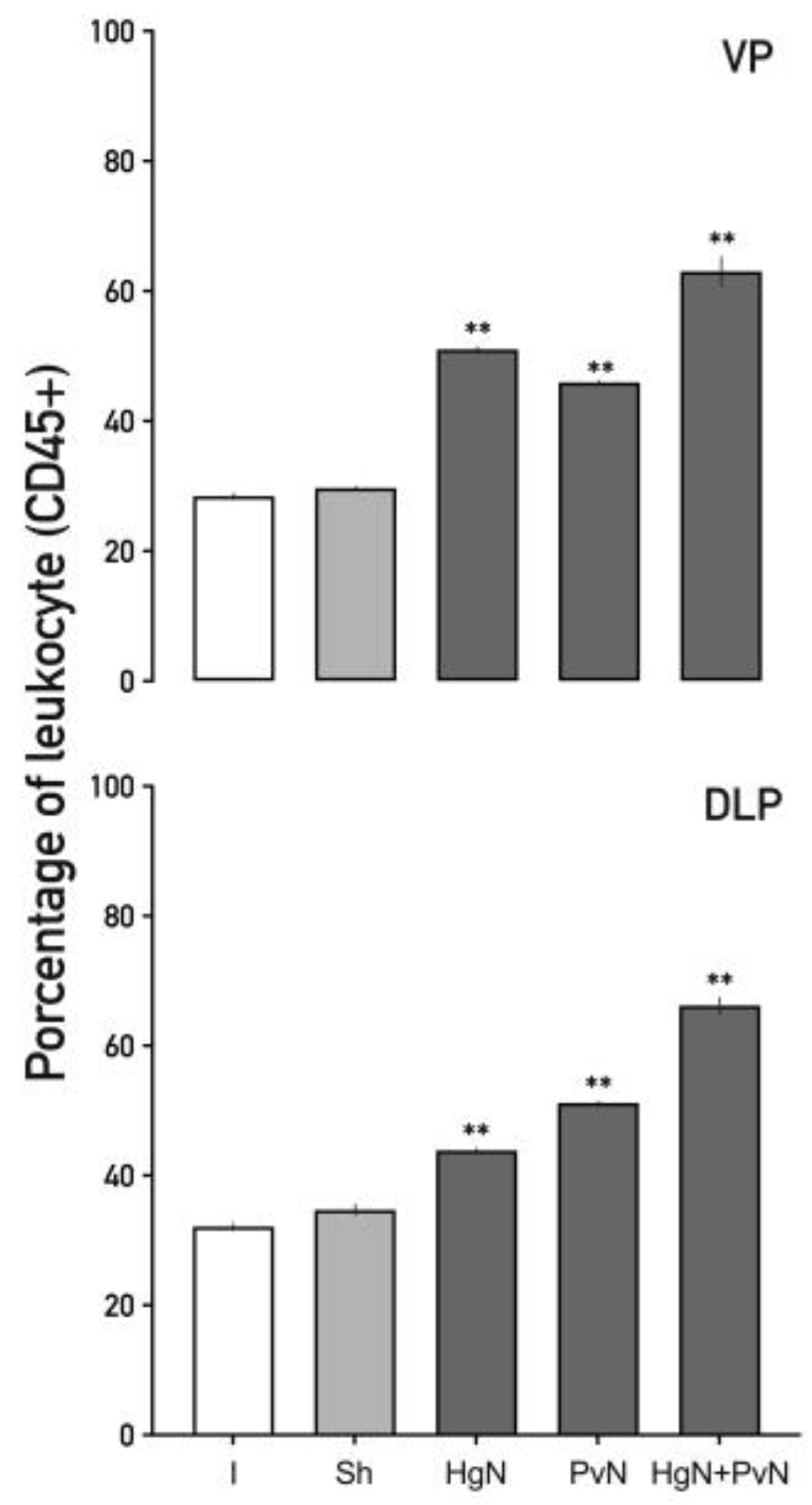

3.2. Immune Cell Infiltration in the Ventral and Dorsolateral Prostate

Preganglionic axotomy significantly increased immune cell infiltration in the prostate. To characterize specific immune populations responding to axotomy, we quantified total leukocytes (CD45⁺), T lymphocytes (CD3⁺), cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8⁺), helper T lymphocytes (CD4⁺), B lymphocytes (CD19⁺), and macrophages (CD11b⁺).

In the ventral prostate (

Figure 3), axotomy led to a substantial increase in CD45⁺ cells. Leukocytes increased by ~50% following Hg or Pv axotomy and by over 60% with double axotomy. Similarly, in the dorsolateral prostate, leukocyte infiltration increased by ~45% with Hg axotomy, ~50% with Pv axotomy, and ~70% with double axotomy. These findings highlight the exacerbated immune response induced by dual nerve denervation.

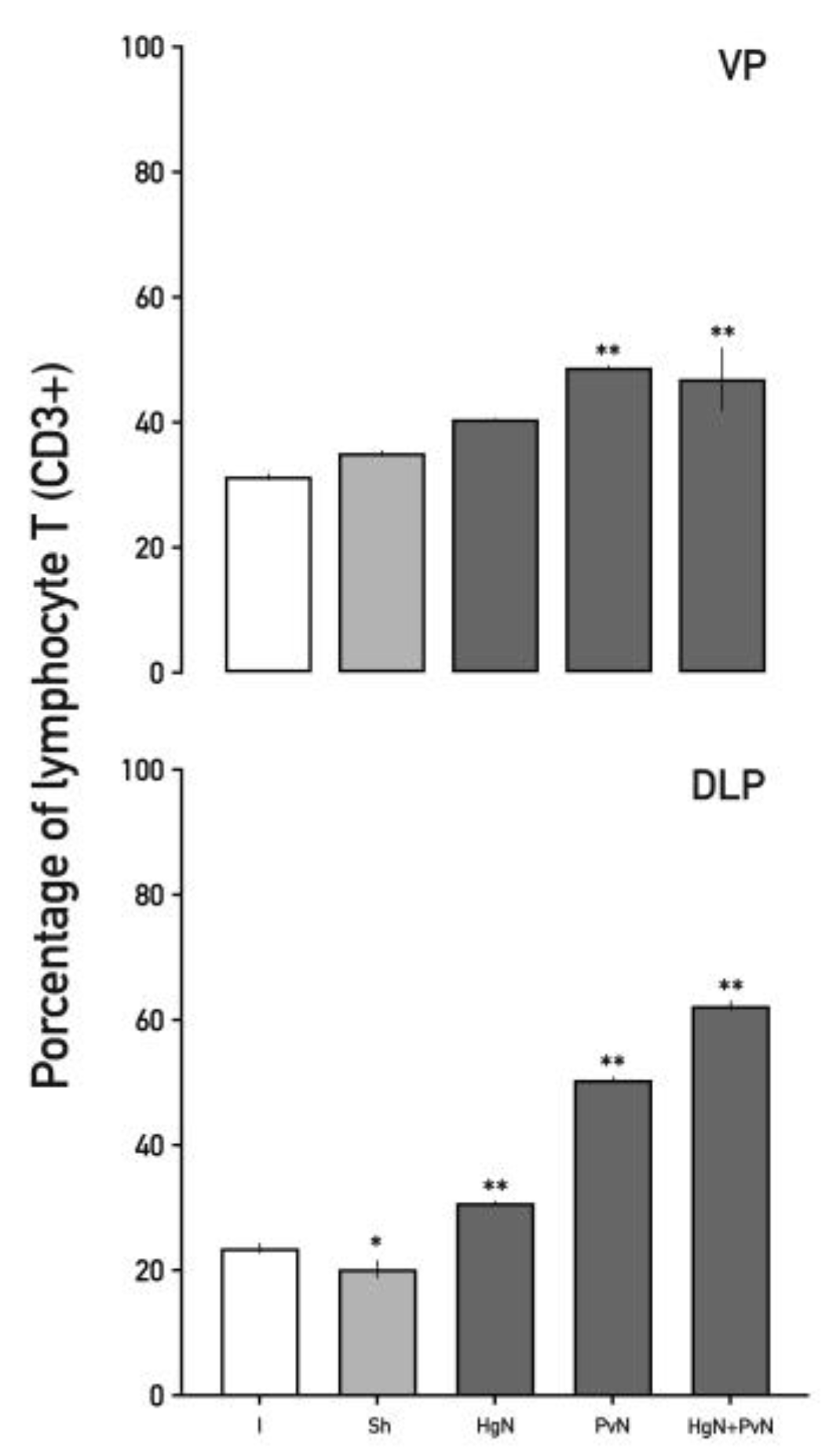

Total T lymphocyte (CD3⁺) levels (

Figure 4) increased in both prostate lobes following axotomy. In the ventral lobe, CD3⁺ cells rose by ~50% after Pv axotomy and double axotomy. In the dorsolateral lobe, increases were ~35% with Hg axotomy, ~45% with Pv axotomy, and ~60% with double axotomy. Interestingly, a slight decrease in T lymphocytes was observed in the sham group, indicating a baseline regulatory state in the absence of nerve injury.

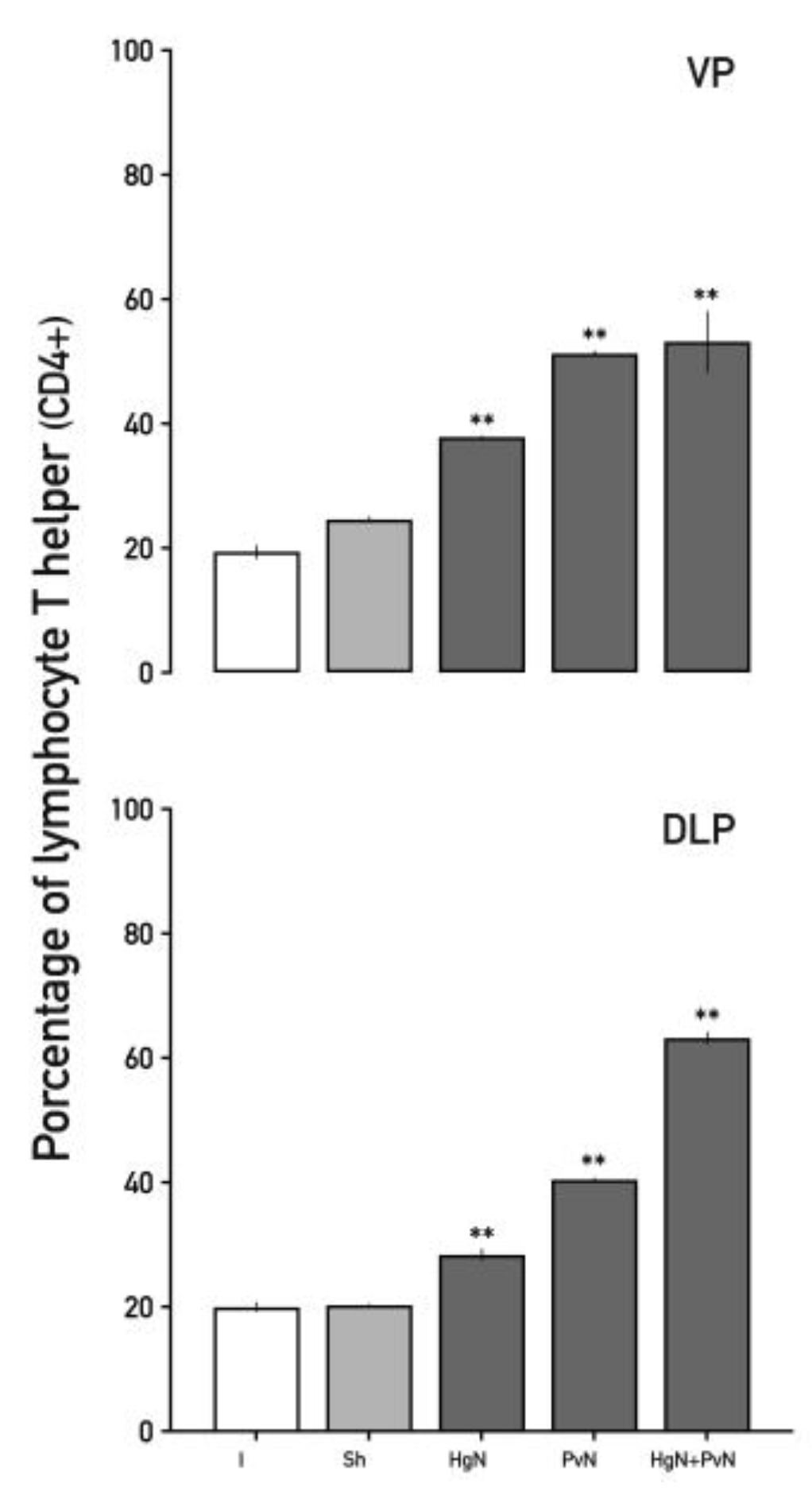

Helper T lymphocytes (CD4⁺) showed substantial increases in response to axotomy (

Figure 5). In the ventral prostate, CD4⁺ cells increased by ~38% with Hg axotomy and by ~55% with Pv and double axotomy. In the dorsolateral lobe, increases were ~35% and ~40% with Hg and Pv axotomy, respectively, and ~63% with double axotomy, underscoring the amplified inflammatory response in dual nerve denervation.

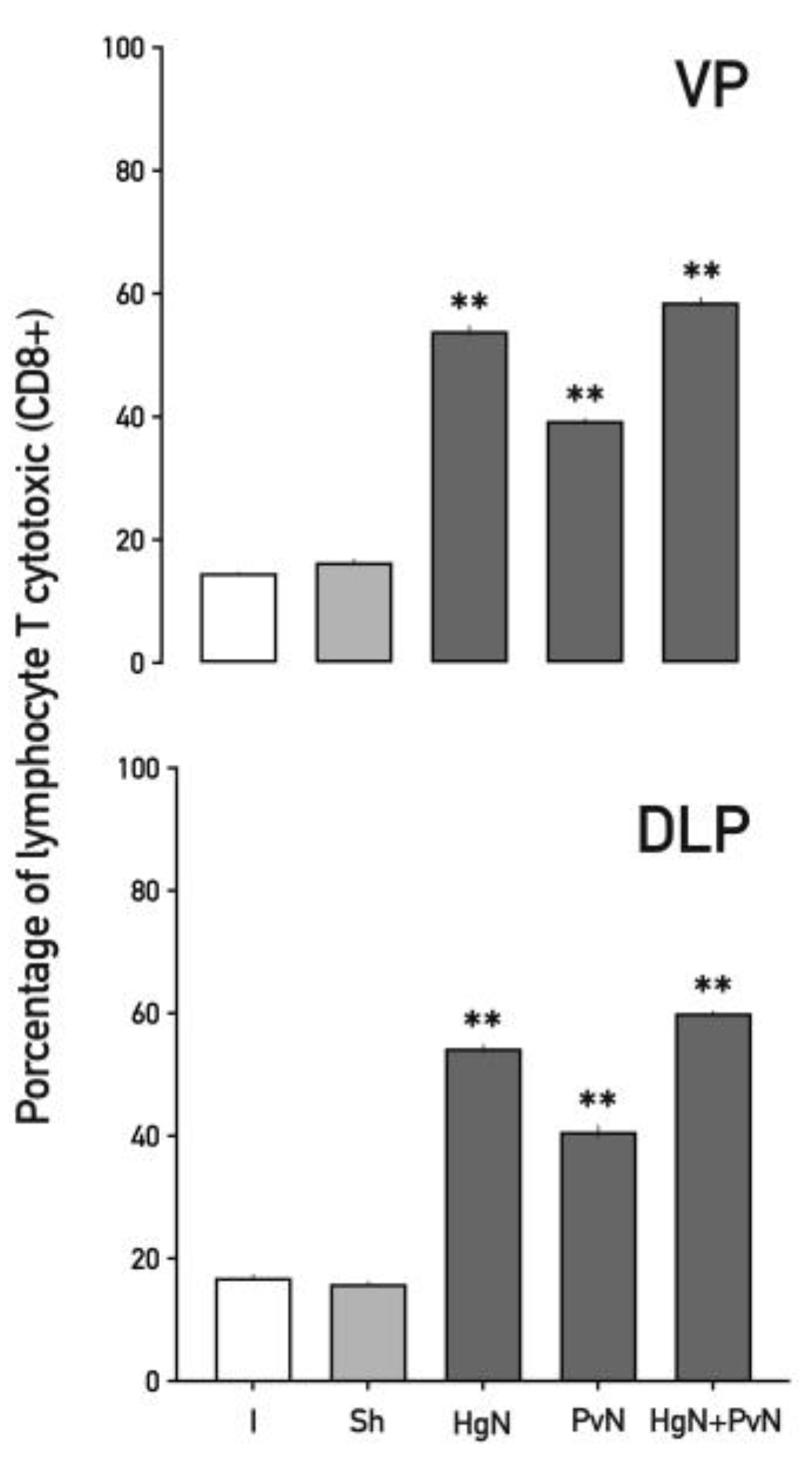

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8⁺) (

Figure 6) were also elevated across both lobes. In the ventral prostate, increases of ~56% with Hg axotomy, ~42% with Pv axotomy, and ~68% with double axotomy were observed. Similar trends were noted in the dorsolateral lobe, indicating a consistent cytotoxic T cell response to nerve injury.

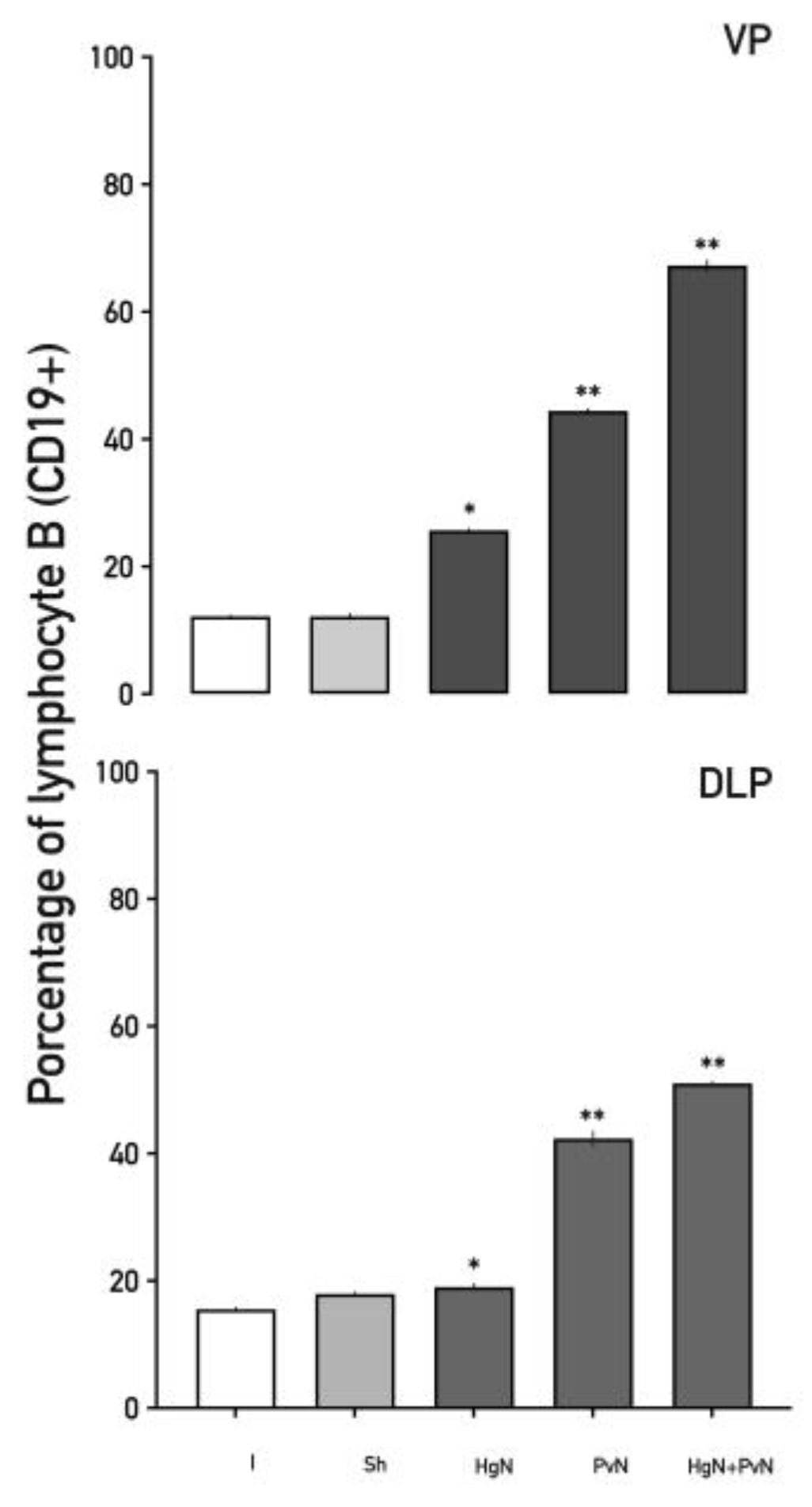

B lymphocyte (CD19⁺) infiltration increased significantly in both lobes (

Figure 7). Following Hg axotomy, CD19⁺ cells increased by 15–25%, while Pv axotomy resulted in ~40% increases. Double axotomy triggered the highest increases, ranging from ~50% to ~60%, suggesting a strong humoral immune response induced by nerve denervation.

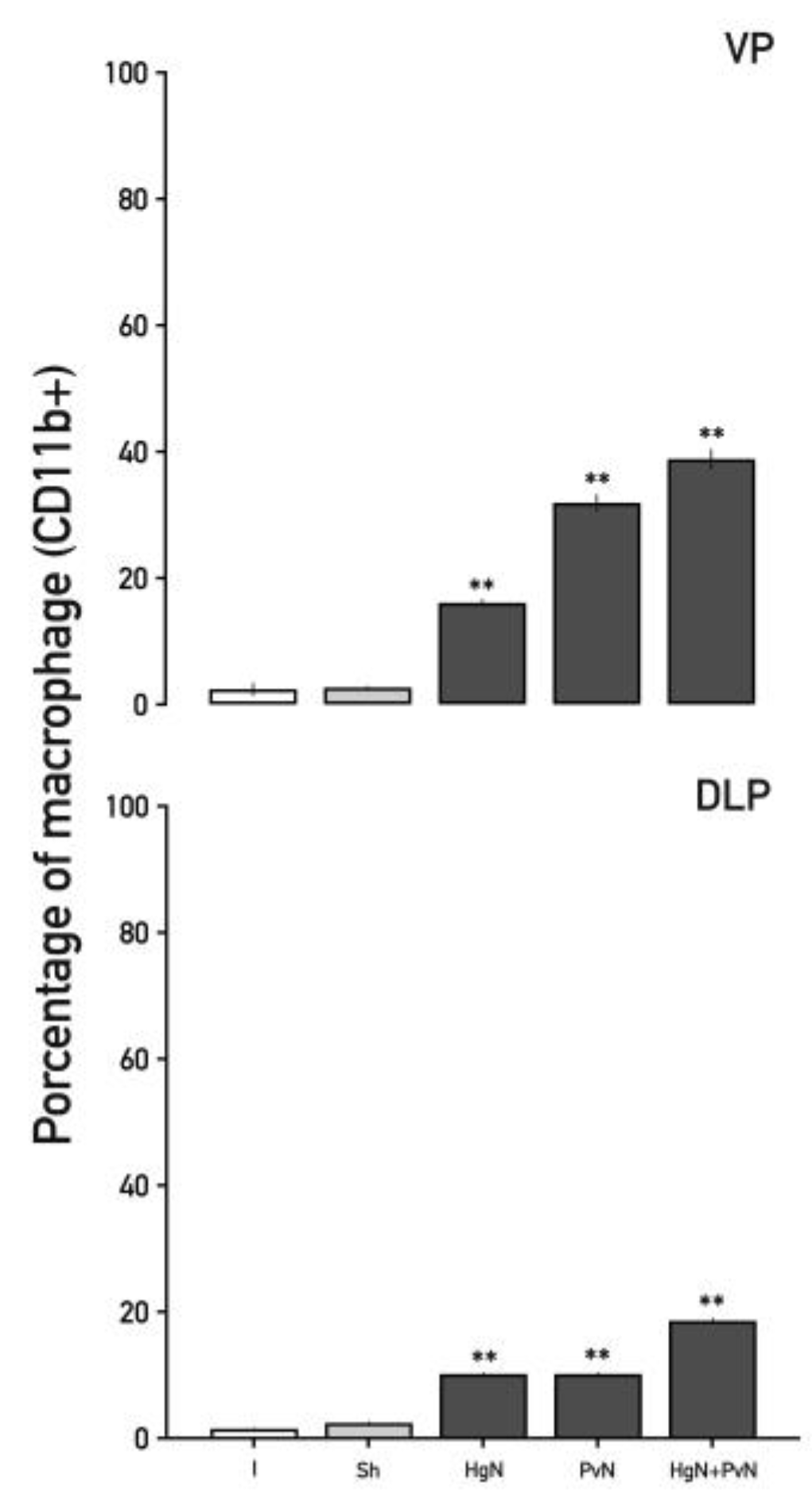

Macrophages (CD11b⁺), key mediators of phagocytosis and immune modulation, displayed progressive increases in the ventral prostate (

Figure 8). Following Hg axotomy, macrophages increased by ~18%, Pv axotomy resulted in a ~35% increase, and double axotomy led to a ~38% rise. In the dorsolateral lobe, macrophage increases were ~10% with Hg and Pv axotomy, escalating to ~20% with double axotomy.

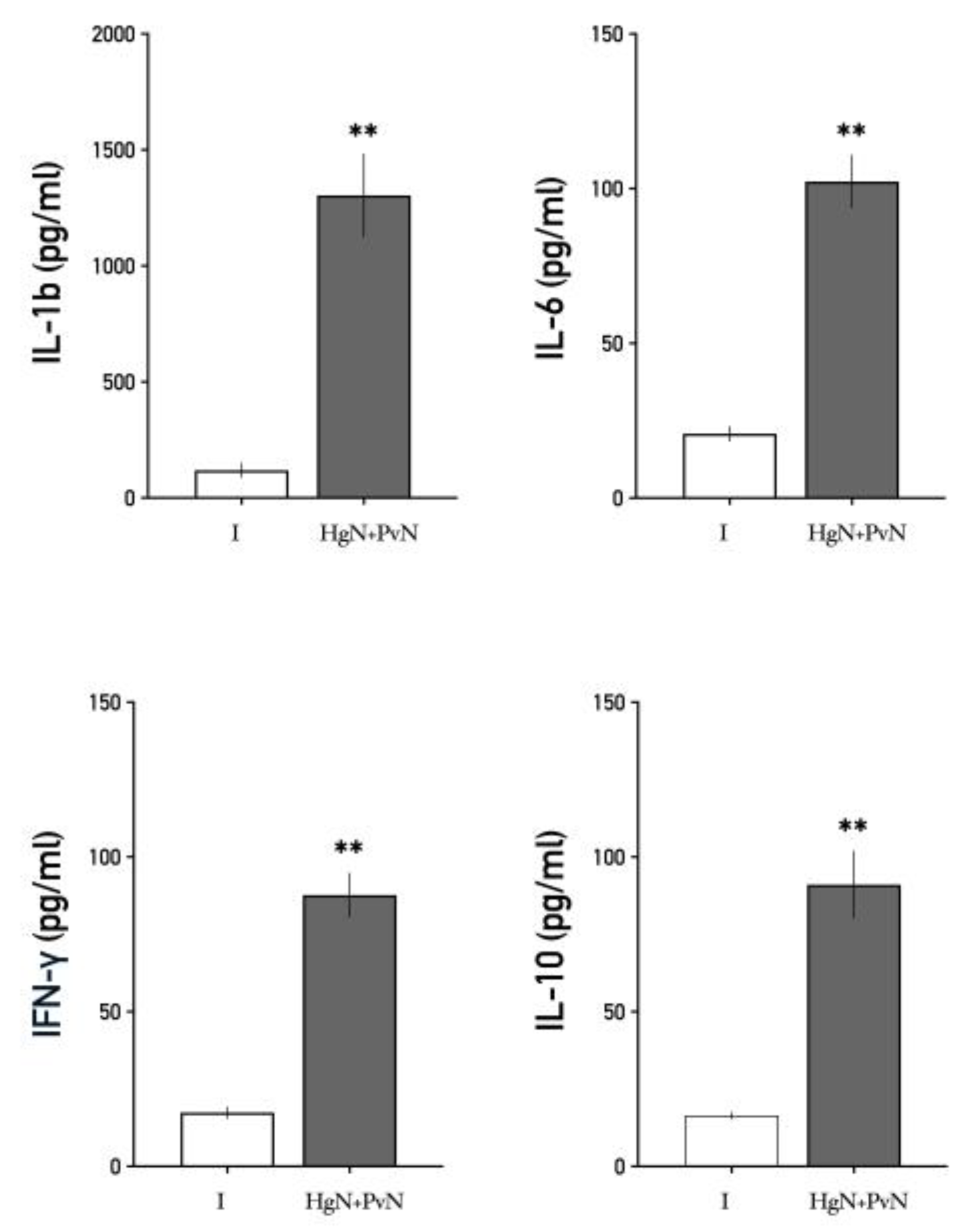

3.3. Systemic Levels of Interleukins

Circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-γ, as well as the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, were significantly elevated in animals subjected to double denervation compared to the sham-operated group (

Figure 9).

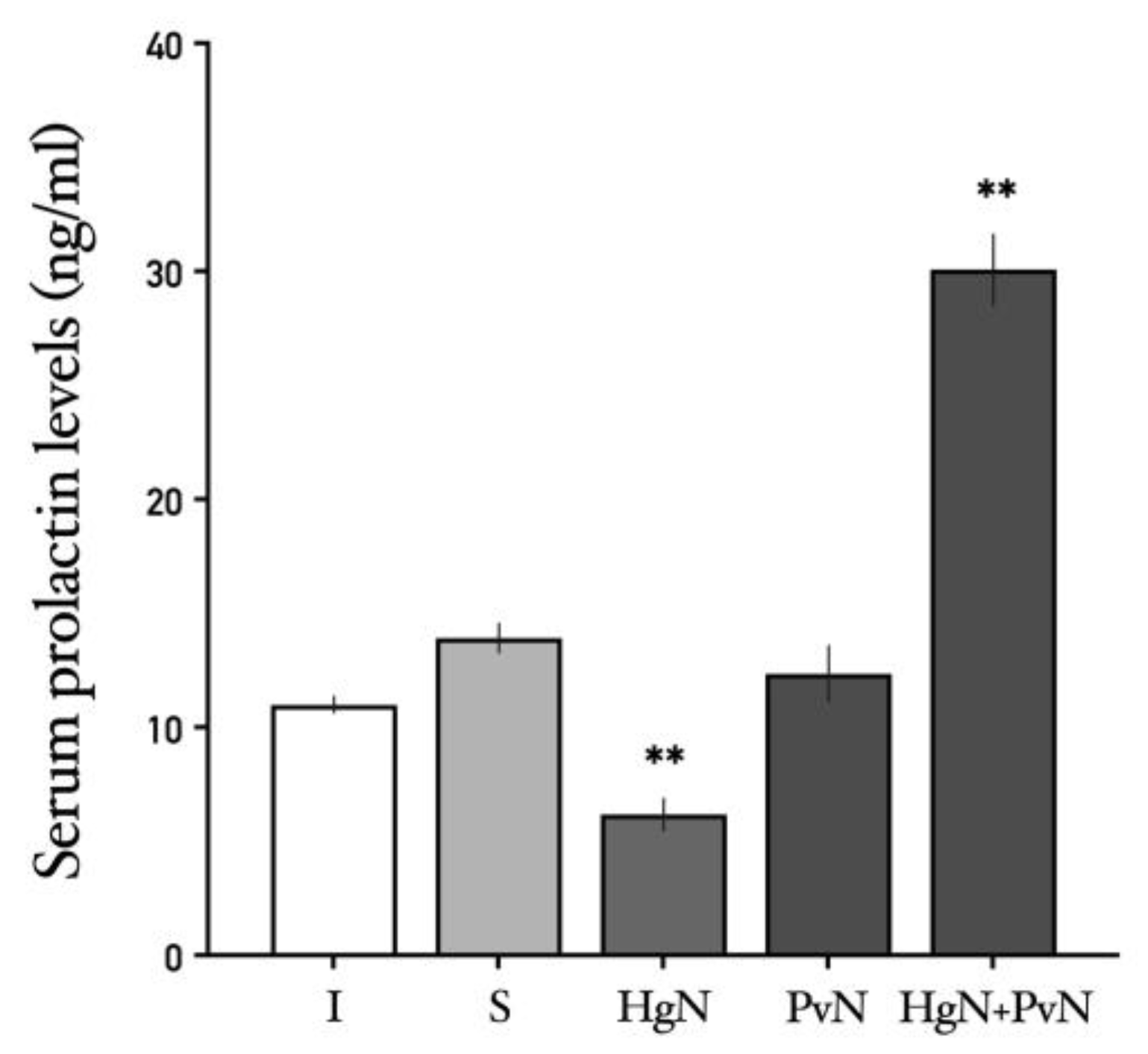

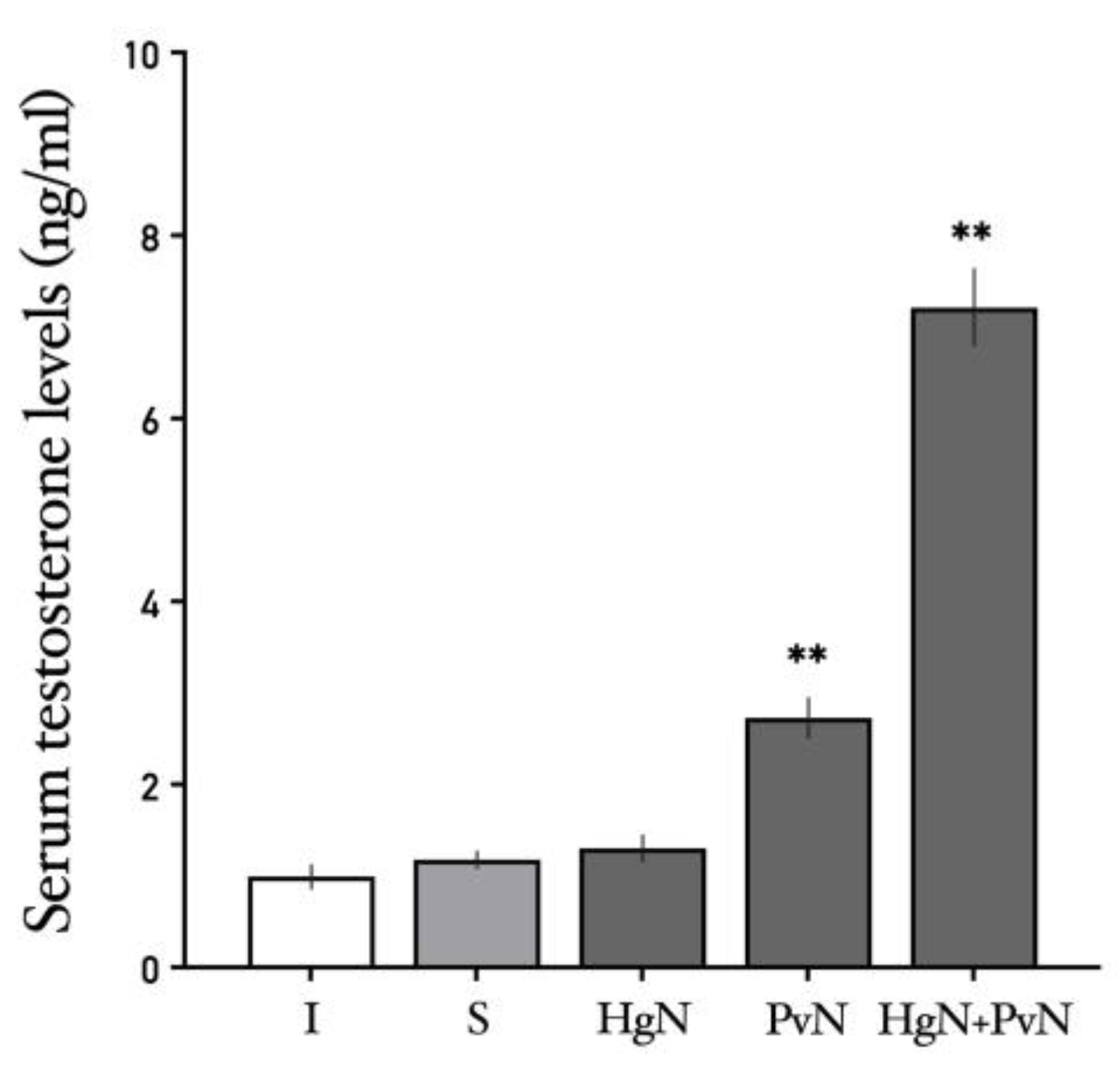

3.4. Systemic Levels of Prolactin and Testosterone

The effects of axotomy on serum prolactin and testosterone levels varied depending on the specific nerves targeted. Prolactin: Axotomy of the Hg nerve led to a decrease in serum prolactin levels, while axotomy of the Pv nerve had no significant effect. Notably, double axotomy (Hg + Pv) induced a significant increase in systemic prolactin levels compared to all other groups (

Figure 10). Testosterone: Serum testosterone levels were unaffected by Hg axotomy compared to the sham-operated group. However, Pv axotomy resulted in a significant increase in testosterone levels, an effect that was further amplified following double axotomy (Hg + Pv) (

Figure 11).

4. Discussion

This study examined the effects of major pelvic ganglion denervation on prostate histology, immune cell infiltration, and systemic levels of interleukins, prolactin, and testosterone in rats. The findings demonstrate that the loss of autonomic innervation profoundly disrupts prostate homeostasis, resulting in structural, immune, and hormonal changes. These results underscore the critical role of autonomic input in maintaining prostate integrity and reveal the intricate interplay between neural regulation, hormonal control, and immune responses.

4.1. Impact of Denervation on Prostate Histology

The prostate gland relies on autonomic innervation for maintaining its structural integrity and normal function. In this study, denervation of the pelvic and hypogastric nerves induced significant histological changes in both the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate. These changes included epithelial atrophy, loss of nuclear polarity, cellular disorganization, and atypical hypertrophy resembling squamous metaplasia. These findings highlight the essential role of neural inputs in preserving the cytoarchitecture of the prostate epithelium, aligning with previous studies that have demonstrated the impact of autonomic control on glandular structure and function [

3,

28,

29,

30,

31].

The observed epithelial atrophy and disorganization are likely attributed to the loss of trophic support provided by neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and norepinephrine, which are secreted by parasympathetic and sympathetic fibers, respectively. These neurotransmitters are known to regulate epithelial cell proliferation, differentiation, and secretory activity [

32,

33]. Despite the established importance of autonomic signaling, the precise molecular mechanisms driving these histological changes remain incompletely understood. One plausible explanation involves alterations to the cytoskeleton, a network of proteins critical for cellular stability and organization [

34].

Denervation may disrupt adrenergic and cholinergic signaling, triggering adaptive changes in the cytoskeleton that destabilize cellular shape and cohesion within the prostate alveoli. Notably, increased expression of nerve growth factor (NGF) and its receptor TrkA has been implicated in promoting cellular atrophy and destabilizing actin filaments, which may contribute to the histological changes observed in this study [

31,

35]

. This suggests that the loss of neural input may upregulate NGF-TrkA signaling, a hypothesis that warrants further investigation.

Another potential factor is vimentin, an intermediate filament protein involved in cellular integrity and adaptability to microenvironmental changes [

36]. Vimentin interacts with actin and tubulin, supporting cytoskeletal stability under physiological conditions. Hormones such as prolactin, testosterone, and adrenaline have been shown to regulate vimentin expression in stromal cells and prostate fibroblasts [

37,

38,

39]. However, overexpression of vimentin under pathological conditions has been associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process linked to structural remodeling and disease progression [

40]. The histological changes observed in the denervated prostate, including cellular disorganization and atypical hypertrophy, may result from vimentin overexpression driving EMT [

39,

41,

42]. Future studies should assess vimentin expression to determine whether these changes are directly attributable to disrupted neurotransmission or are secondary to elevated prolactin or testosterone levels observed in this study.

In summary, denervation-induced disruption of signaling molecules may destabilize the cytoskeleton, impairing cellular cohesion and structure. Alternatively, vimentin overexpression may promote EMT, further contributing to the observed histological changes in the prostate [

43,

44]

. Investigating these mechanisms will provide valuable insights into how autonomic inputs regulate prostate integrity and how their loss contributes to disease pathogenesis.

4.2. Enhanced Immune Cell Infiltration and Inflammatory Response

One of the most striking observations in this study was the increased presence of leukocytes in prostate tissue following denervation. While leukocyte infiltration in the prostate of rats has been previously reported, with a notable presence of CD4⁺, CD8⁺, and NK lymphocytes playing key roles in maintaining tissue homeostasis denervation significantly amplified immune cell infiltration [

16,

20,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. This included total leukocytes (CD45⁺), T lymphocytes (CD3⁺, CD4⁺, CD8⁺), B lymphocytes (CD19⁺), and macrophages (CD11b⁺). The elevated presence of these immune cells in both the stroma and lumen indicates an active inflammatory response triggered by the loss of neural regulation.

This observation aligns with the concept that the nervous system plays a critical role in modulating immune function, and disruption of this regulation can lead to inflammation [

50]. Autonomic nerves influence immune responses through the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines and modulation of endothelial adhesion molecule expression, which governs leukocyte extravasation [

51]. The absence of autonomic input may disrupt these mechanisms, allowing increased immune cell recruitment into the prostate.

One potential mechanism underlying this infiltration involves the upregulation of chemokines, such as IL-8, by epithelial cells following denervation [

52]. IL-8 is a potent chemoattractant for immune cells, primarily neutrophils, but it also plays a role in recruiting other immune populations, including T cells and macrophages [

53,

54]. This chemokine-driven recruitment may be further amplified by the interaction between immune cells and prostate epithelial cells via CD40-CD40L signaling. Prostate epithelial cells in both rats and humans express the CD40 receptor [

55], while the CD40L ligand is expressed on B cells, macrophages, and activated T lymphocytes [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60].

Denervation may increase CD40 expression in damaged epithelial cells, perpetuating inflammation and promoting the development of prostate pathologies [

61] such as chronic prostatitis and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). The persistence of this inflammatory state suggests a shift in the local immune environment, potentially contributing to long-term tissue remodeling and dysfunction. Future studies should investigate whether blocking IL-8 signaling or inhibiting CD40-CD40L interactions can mitigate inflammation and preserve prostate homeostasis. Understanding the molecular pathways driving immune cell infiltration could offer new therapeutic targets for managing prostate diseases associated with chronic inflammation.

4.3. Elevated Systemic Cytokine Levels

This study identified significant increases in systemic levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-γ, along with the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, in animals subjected to denervation. These cytokines play pivotal roles in both the initiation and maintenance of inflammatory responses. IL-1β and IL-6 are critical for the activation and differentiation of immune cells, while IFN-γ is essential for macrophage activation and antigen presentation [

62]. The elevation of IL-10 likely represents a compensatory mechanism aimed at limiting excessive inflammation. IL-10 is well-known for its ability to inhibit the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mitigate immune-mediated tissue damage [

63].

The simultaneous elevation of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines reflects a complex regulatory response to denervation-induced tissue injury. This type of immune modulation has been observed in diseases such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma [

64], colorectal cancer [

65], and even prostate cancer [

66] where local tissue damage triggers systemic cytokine production. The origin of this systemic response warrants further investigation. Evidence suggests that the spleen may play a role in secreting these interleukins into the general circulation in response to tissue damage, stress, or metabolic disturbances such as obesity [

67,

68]. This release aims to regulate the function of immune cells recruited to the affected tissue [

54].

In the context of this study, the increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-γ could indicate the presence of chronic inflammation driven by tissue injury. It is plausible to hypothesize that the spleen responds to IL-8 secretion by prostate epithelial cells, as the spleen expresses receptors for this chemokine [

54]. This interaction may mediate the observed systemic cytokine elevations. Testing this hypothesis in future studies could clarify the role of spleen and other immune organs in denervation-induced inflammation.

4.4. Alterations in Serum Prolactin and Testosterone Levels

Denervation resulted in significant increases in serum levels of prolactin and testosterone, particularly pronounced when both the pelvic and hypogastric nerves were transected. Prolactin, beyond its role as a hormone, also functions as a cytokine, influencing immune responses and promoting inflammation [

69]. Elevated prolactin levels may enhance the recruitment and activation of immune cells within the prostate, contributing to the inflammatory environment observed in denervated tissue. The increase in testosterone levels following denervation is particularly intriguing, given its established role in prostate growth and function. Testosterone is generally considered to have anti-inflammatory effects within the prostate, and its elevation may reflect a compensatory mechanism aimed at mitigating inflammation [

70].

Disrupted neural input likely affects the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, leading to altered hormonal secretion. Both prolactin and testosterone are regulated by the hypothalamus: dopamine, produced in the arcuate nucleus, inhibits prolactin release, while gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulates luteinizing hormone (LH) release, promoting testosterone synthesis in the testes. Denervation-induced changes in neural signaling may reduce dopamine-mediated inhibition of prolactin and increase GnRH secretion, thereby elevating both hormones. Additionally, evidence suggests a connection between the prostate, the hypothalamus, the preoptic area, and the arcuate nucleus [

71,

72,

73]. The loss of autonomic control from the prostate may disrupt this communication, triggering hormonal changes. Reduced dopamine levels in the portal circulation and elevated thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) levels have been observed under similar conditions, which could contribute to the increased prolactin and testosterone levels seen in this study [

74].

4.5. Interplay Between Neural Regulation, Hormones, and Immune Responses

This study highlights the intricate relationship between neural inputs, hormonal regulation, and immune responses in maintaining prostate homeostasis. Autonomic nerves not only regulate the physiological functions of the prostate, such as secretion and structural integrity, but also play a critical role in modulating local immune surveillance and systemic hormone levels. Denervation disrupts this finely tuned balance, resulting in structural changes, increased inflammation, and hormonal dysregulation. The significant rise in immune cell infiltration and cytokine levels observed in this study underscores the protective role of neural inputs in maintaining immune homeostasis within the prostate. By modulating the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines and controlling leukocyte recruitment, autonomic nerves appear to prevent excessive immune activation and inflammation.

The loss of autonomic control may leave prostate tissue vulnerable to heightened immune activity, creating a pro-inflammatory environment that facilitates tissue remodeling and dysfunction. This inflammatory milieu, combined with hormonal imbalances, could contribute to the development of pathological conditions such as prostatitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), or even prostate cancer [

15,

16,

75].

4.6. Implications for Prostate Diseases and Future Directions

Chronic inflammation is a well-established contributor to the pathogenesis of prostate diseases, including prostatitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and prostate cancer. The denervation-induced inflammatory response observed in this study provides a potential mechanistic link between neural dysfunction and prostate pathology. Understanding how autonomic nerves regulate immune cell behavior and cytokine production could reveal novel therapeutic targets for managing prostate conditions driven by inflammation.

Additionally, the hormonal alterations following denervation underscore the importance of considering neuroendocrine factors in prostate disease development. The interplay between elevated prolactin and testosterone levels and their effects on prostate tissue and immune responses warrants further investigation. While this study offers valuable insights into the neuroimmune and neuroendocrine mechanisms underlying prostate pathologies, several limitations should be acknowledged. The exact molecular pathways through which denervation leads to increased cytokine production and immune cell infiltration remain to be fully elucidated. Future studies should focus on identifying these mechanisms, including the roles of neurotrophic factors, neurotransmitter receptors on immune cells, and the hypothalamic-pituitary axis in mediating these effects.

Moreover, investigating the long-term consequences of denervation on prostate health and determining whether these changes are reversible will have important clinical implications. Exploring pharmacological interventions targeting autonomic inputs, cytokine signaling, or hormonal regulation may provide effective strategies to mitigate inflammation, restore homeostasis, and prevent disease progression. By addressing these knowledge gaps, future research could pave the way for innovative approaches to the prevention and treatment of prostate diseases associated with autonomic dysfunction.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that major pelvic ganglion denervation disrupts prostate homeostasis through significant alterations in tissue structure, immune responses, and hormonal regulation. The observed histological changes, including epithelial atrophy, cellular disorganization, and hypertrophy, highlight the essential role of autonomic innervation in maintaining prostate cytoarchitecture.

Concurrently, increased immune cell infiltration and elevated systemic levels of both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines underscore the profound inflammatory response triggered by the loss of neural control. Hormonal imbalances, such as elevated prolactin and testosterone levels, further illustrate the systemic consequences of denervation, pointing to disrupted neuroendocrine regulation via the hypothalamic-pituitary axis.

Together, these findings suggest that neural dysfunction may contribute to prostate disease pathogenesis by creating a microenvironment characterized by chronic inflammation and hormonal dysregulation, conditions known to drive diseases such as prostatitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and prostate cancer. By elucidating the interplay between neural inputs, immune activity, and hormonal control, this study offers a foundation for future research aimed at developing therapeutic strategies targeting neuroimmune and neuroendocrine pathways. Such approaches could help mitigate inflammation, restore hormonal balance, and preserve prostate function in the face of autonomic dysfunction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ma. Elena Hernández-Aguilar and Cynthia Fernández-Pomares; methodology, JC Rodríguez-Alba; formal analysis, Jorge Manzo and Genaro A. Coria-Ávila; investigation, Pabeli Becerra-Romero; resources, Ma. Elena Hernández-Aguilar and JC Rodríguez-Alba; data curation Ma. Elena Hernández-Aguilar and Pabeli Becerra Romero; writing—original draft preparation, Pabeli Becerra-Romero and Ma. Elena Hernández-Aguilar; writing—review and editing, Gonzalo E. Aranda-Abreu and Fausto Rojas-Durán.; visualization, Deissy Herrera-Covarrubias.; supervision, JC Rodríguez-Alba and Ma. Rebeca Toledo-Cárdenas.; project administration, Cynthia Fernández-Pomares.; funding acquisition, Ma. Elena Hernández-Aguilar.

Funding

This research was supported by a scholarship from CONACyT (grant no. PSBR/960407) awarded and the Academic Corps of Neurochemistry (UV-CA304) and UV-SIREI project (10480202266), of Universidad Veracruzana.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board the Internal Committee for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals (CICUAL) of the Brain Research Institute at Universidad Veracruzana (registration no. 2021-016-a), following the Mexican Official Standard NOM-062-ZOO-1999.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are in this manuscript, there is no additional data.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to Miriam Barradas Moctezuma, Eloy Gasca-Pérez and Marilú Domínguez-Pantoja for her technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| BPH |

Bening prostatic hyperplasia |

| CD |

Cluster of differentiation |

| CICUAL |

Comité Interno para el Uso y Cuidado de Animales de Laboratorio |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay |

| FBS |

Fetal Bovine Serum |

| Hg |

Hypogastric nerve |

| MPG |

Mayor Pelvic Ganglion |

| Pv |

Pelvic Nerve |

| INF-γ |

Interferon gamma |

| IL |

Interleukin |

References

- Lotti, F; Maggi, M. Sexual dysfunction and male infertility. Nat Rev Urol 2018, 15, 287-307. [CrossRef]

- Landa-García, JN; Palacios-Arellano, M de la P; Morales, MA; Aranda-Abreu, GE; Rojas-Durán F; Herrera-Covarrubias, D; et al. The Anatomy, Histology, and Function of the Major Pelvic Ganglion. Animals. 2024, 14(17), 2570. [CrossRef]

- Hérnandez-Aguilar, ME; Aranda-Abreu, G; Rojas-Durán F. Neuroendocrine and molecular aspects of the physiology and pathology of the prostate. In: Behavioral Neuroendocrinology. 1st ed. Editor Barry Komisaruk, Gabriela González-Mariscal. Publisher: Taylor & Francis, Boca Ratón, 2017, p. 263-277. ISSBN: 9781498731911.

- Sánchez-Zavaleta, V; Mateos-Moreno, A; Cruz-Rivas, VH; Aranda-Abreu, G; Herrera-Covarrubias, D; Manzo-Denes, J; et al. Contribución del sistema nervioso autónomo y la conducta sexual en la fisiopatología de la próstata. eNeurobiologia. 2021, 12(29), 180221. [CrossRef]

- Whitney, KM; Male Accessory Sex Glands. In: Boorman’s Pathology of the Rat: Reference and Atlas. Editor Andrew W. Suttie, Gary A. Boorman, Joel R. Leininger, Scot L. Eustis, Michael R. Elwell, William F. MacKenzie; et al. Publisher: Academic Press. Virginia, 2018. p,579–87. [CrossRef]

- Brandes, D; The fine structure and histochemistry of prostatic glands in relation to sex hormones. Int Rev Cytol. 1966; 20, 207-276. [CrossRef]

- Darras, FS; Lee C, Huprikar, S; Rademaker, AW; Grayhack, JT. Evidence for a non-androgenic role of testis and epididymis in androgen-supported growth of the rat ventral prostate. J Urol. 1992, 148, 432-440. [CrossRef]

- Ford, WC; Hamilton, DW. The effect of experimentally induced diabetes on the metabolism of glucose by seminiferous tubules and epididymal spermatozoa from the rat. Endocrinology. 1984, 115(2), 716-722. [CrossRef]

- Andriole, G; Bruchovsky, N; Chung, LWK; Matsumoto, AM; Rittmaster, R; Roehrborn, C; et al. Dihydrotestosterone and the prostate: The scientific rationale for 5alpha-reductase inhibitors in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2004; 172. 1399–403. [CrossRef]

- Chung, LW; Cunha, GR. Stromal-epithelial interactions: II. Regulation of prostatic growth by embryonic urogenital sinus mesenchyme. Prostate. 1983, 4(5), 503-511. [CrossRef]

- Kindblom, J; Dillner, K; Ling, C; Törnell, J; Wennbo, H. Progressive prostate hyperplasia in adult prolactin transgenic mice is not dependent on elevated serum androgen levels. Prostate. 2002; 53(1), 24-33. [CrossRef]

- Nevalainen, MT; Valve, EM; Ingleton, PM; Nurmi, M; Martikainen, PM; Harkonen, PL. Prolactin and prolactin receptors are expressed and functioning in human prostate. J Clin Invest. 1997; 99(4), 618-627. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Aguilar, ME; Serrano, MK; Pérez F; et al. Quantification of neural and hormonal receptors at the prostate of long-term sexual behaving male rats after lesion of pelvic and hypogastric nerves. Physiol Behav. 2020; 222, 112915. [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Moreno, Alejandro; Sánchez-Zavaleta, Viridiana; Aranda-Abreu, Gonzalo; Herrera-Covarrubias, Deissy; Rojas-Durán, Fausto; et al. Effect of preganglionar denervation on the expression of adrenergic, muscarinic, androgen, and prolactin receptors at the major pelvic ganglion of long-term sexual behaving male rats. eNeurobiologia. 2021, 12(29), 050321. [CrossRef]

- Kyprianou, N; Tu, H; Jacobs, SC. Apoptotic versus proliferative activities in human benign prostatic hyperplasia. Hum Pathol. 1996, 27(7), 668–675. [CrossRef]

- De Marzo, AM; Nakai, Y; Nelson, WG. Inflammation, atrophy, and prostate carcinogenesis. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2007, 25(5), 398-400. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A; Allavena, P; Sica, A; Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008; 454, 436-444. [CrossRef]

- Sfanos, KS; Isaacs, WB; Marzo, AM; Infections and inflammation in prostate cancer. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2013, 1(1), 3-11. PMC4219279.

- Sfanos, KS; Yegnasubramanian, S; Nelson, WG; De Marzo, AM. The inflammatory microenvironment and microbiome in prostate cancer development. Nature Reviews Urology. 2017, 15(1), 11–24. [CrossRef]

- Chow, MT; Möller, A; Smyth, MJ. Inflammation and immune surveillance in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012; 2012, 608406. [CrossRef]

- Fibbi, B; Penna, G; Morelli A; Adorini L; Maggi M. Chronic inflammation in the pathogenesis of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int J Androl. 2010, 33(3), 475–488. [CrossRef]

- Haverkamp, J; Charbonneau, B; Ratliff, TL. Prostate inflammation and its potential impact on prostate cancer: A current review. J Cell Biochem. 2008, 03(5), 1344–1353. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X; Goldstein, AS. Inflammation promotes prostate differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014, 111(5), 1666–1667. [CrossRef]

- Penna, G; Fibbi, B; Amuchastegui, S; Cossetti, C; Aquilano, F; Laverny, G; et al. Human Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Stromal Cells As Inducers and Targets of Chronic Immuno-Mediated Inflammation. The Journal of Immunology. 2009, 182(7), 4056–4064. [CrossRef]

- Sfanos, KS; De Marzo, AM. Prostate cancer and inflammation: The evidence. Histopathology. 2012; 60(1), 199-215. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y; Yu, W; Liu, Z; et al. The inflammation patterns of different inflammatory cells in histological structures of hyperplasic prostatic tissues. Transl Androl Urol. 2020, 13, 842008. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Zavaleta V. Efecto de la conducta sexual y la denervación preganglionar sobre las características histológicas de la próstata y el ganglio pélvico mayor en la rata. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad Veracruzana, Instituto de Investigaciones Cerebrales, México. 2021, http://cdigital.uv.mx/handle/1944/50550.

- Wang, JM; McKenna, KE; McVary, KT; Lee, C. Requirement of Innervation for Maintenance of Structural and Functional Integrity in the Rat Prostate. Biol Reprod. 1991, 44(6), 1171–6. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Piñeiro, L; Dahiya, R; Nunes, LL; Tanagho, EA; Schmidt, RA. Pelvic Plexus Denervation in Rats Causes Morphologic and Functional Changes of the Prostate. J Urol. 1993, 150(1), 215–218. [CrossRef]

- McVary KT; McKenna, KE; Lee, C. Prostate innervation. Prostate. 1998, 36, 2–13.

- Huang, YH; Zhang, YQ; Huang, JT. Neuroendocrine cells of prostate cancer: Biologic functions and molecular mechanisms. Asian J Androl. 2019, 21(3), 291-295. [CrossRef]

- Luján, M; Páez, A; Llanes, L; Angulo, J; Berenguer, A. Role of autonomic innervation in rat prostatic structure maintenance: A morphometric analysis. J Urol. 1998, 160(5), 1919–23.

- Golomb, E; Kruglikova, A; Dvir, D; Parnes, N; Abramovici, A. Induction of atypical prostatic hyperplasia in rats by sympathomimetic stimulation. Prostate. 1998, 34(3), 214-221. [CrossRef]

- Ingber, DE. Tensegrity II. How structural networks influence cellular information processing networks. J Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 1397–1408. [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulou, V; Pediaditakis, I; Alkahtani, S; Alarifi, SA; Schmidt, EM; et al. Differential effects of dehydroepiandrosterone and testosterone in prostate and colon cancer cell apoptosis: The role of nerve growth factor (NGF) receptors. Endocrinology. 2013, 154(7), 2446-2249. [CrossRef]

- Coulombe, PA; Wong, P. Cytoplasmic intermediate filaments revealed as dynamic and multipurpose scaffolds. Nature Cell Biology. 2004, 6(8), 699-706. [CrossRef]

- Hetzl, A. C.; Montico, F; Kido, L. A.; Cagnon, V. H. Prolactin, EGFR, vimentin and α-actin profiles in elderly rat prostate subjected to steroid hormonal imbalance. Tissue & cell. 2016, 48(3), 189–196. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S; Thraves, P; Kuettel, M; Dritschilo, A. Cytoskeletal and adhesion protein changes during neoplastic progression of human prostate epithelial cells. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1998, 1, 69-79. [CrossRef]

- Lang, SH; Frame, FM; Collins, AT. Prostate cancer stem cells. J of Path. 2009; 217(2), 299-306. PMID: 19040209.

- Morgan EL; Scarth JA; Patterson MR; Wasson CW; Hemingway GC; et al. E6-mediated activation of JNK drives EGFR signalling to promote proliferation and viral oncoprotein expression in cervical cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28(5), 1669-1687. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S; Sadacharan, S; Su, S; Belldegrun, A; Persad, S; Singh, G. Overexpression of vimentin: Role in the invasive phenotype in an androgen-independent model of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 2306–2311.

- Zhang, M; Luo, C; Cui, K; Xiong, T; Chen, Z. Chronic inflammation promotes proliferation in the prostatic stroma in rats with experimental autoimmune prostatitis: Study for a novel method of inducing benign prostatic hyperplasia in a rat model. World J Urol. 2020, 11, 2933-2943. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B; Kwon, OJ; Henry, G; Malewska, A; Wei, X, Zhang, L; et al. Non-Cell-Autonomous Regulation of Prostate Epithelial Homeostasis by Androgen Receptor. Mol Cell. 2016, 63(6), 976-989. [CrossRef]

- Van Leenders, GJ; Gage, WR; Hicks, JL; et al. Intermediate cells in human prostate epithelium are enriched in proliferative inflammatory atrophy. Am J Pathol. 2003, 162(5), 1529-1537. [CrossRef]

- Anim, JT; Udo, C; John, B. Characterisation of inflammatory cells in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Acta Histochem. 1998, 100(4), 439-449. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, G; Mitteregger, D; Marberger, M. Is Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) an Immune Inflammatory Disease? Eur Urol. 2007, 51(5), 1202-1216. [CrossRef]

- Lindborg, JA; Niemi, JP; Howarth, MA; Liu, KW; Moore, CZ; et al. Molecular and cellular identification of the immune response in peripheral ganglia following nerve injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2018, 15(1), 192. [CrossRef]

- Vykhovanets, E V.; Resnick, MI; Marengo, SR. The healthy rat prostate contains high levels of natural killer-like cells and unique subsets of cd4+ helper-inducer t cells: Implications for prostatitis. J Urol. 2005, 173(3). 1004-1010. [CrossRef]

- Mastrogeorgiou, M; Chatzikalil, E; Theocharis, S; Papoudou-Bai, A; Péoc’h, M; et al. The immune microenvironment of cancer of the uterine cervix. Histology and Histopathology. 2024, 39(10), 1245-1271. [CrossRef]

- Bellinger, DL; Lorton, D. Autonomic regulation of cellular immune function. Autonomic Neuroscience. 2014, 182, 15-41. [CrossRef]

- Nourshargh S, Alon R. Leukocyte Migration into Inflamed Tissues. Immunity. Cell Press. 2014, 41(5), 694-707. [CrossRef]

- Kundu, JK; Surh, YJ. Inflammation: Gearing the journey to cancer. Mutation Research. 2008, 659(1-2), 15-30. [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, SL; Standiford, T; Kasahara, K; Strieter, RM. Interleukin-8 (IL-8): The major neutrophil chemotactic factor in the lung. Exp Lung Res. 1991, 17(1), 17-23. [CrossRef]

- Neveu, B; Moreel, X; Deschênes-Rompré, M. P.; Bergeron, A; LaRue, H; et al. IL-8 secretion in primary cultures of prostate cells is associated with prostate cancer aggressiveness. Research and reports in urology. 2014, 6, 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Van Kooten, G; Banchereau, J. CD40-CD40 ligand. Vol. 67, Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2000, 67(1), 2-17. [CrossRef]

- Beadling, C; Slifka, MK. Regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses by the related cytokines IL-12, IL-23, and IL-27. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2006. 54(1), 15-24. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y; Yang, L; Wei, Q; Ding, Y; Tang, Z; et al. Toll-like receptor 10 (TLR10) exhibits suppressive effects on inflammation of prostate epithelial cells. Asian J Androl. 2019, 21(4), 393-399. [CrossRef]

- Gambara, G; De Cesaris, P; De Nunzio, C; Ziparo, E; Tubaro, A; et al. Toll-like receptors in prostate infection and cancer between bench and bedside. J Cell Mol Med. 2013, 17(6), 713-722. [CrossRef]

- Quintar, AA; Roth, FD; Paul AL, De; Aoki, A; Maldonado, CA. Toll-Like Receptor 4 in Rat Prostate: Modulation by Testosterone and Acute Bacterial Infection in Epithelial and Stromal Cells. Biol Reprod. 2006, 75(5), 664-672. [CrossRef]

- Yang MG, Xu ZQ. Impact of immune inflammation on the proliferation and apoptosis of benign prostatic hyperplasia cells. Nat J of Andro. 2021, 27, 867–75.

- Stark, T; Livas, L; Kyprianou, N. Inflammation in prostate cancer progression and therapeutic targeting. Transl Andrology and Urology. 2015, 4(4), 455-463. [CrossRef]

- Voronov, E; Shouval, DS; Krelin, Y; Cagnano, E; Benharroch, D; et al. IL-1 is required for tumor invasiveness and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003. 100(5), 2645-2650. [CrossRef]

- Mosser, DM; Zhang, X. Interleukin-10: New perspectives on an old cytokine. Immunol Rev. 2008, 226, 205-218. [CrossRef]

- Kurzrock, R. Cytokine deregulation in cancer. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2001, 55, 543-547. [CrossRef]

- Kamiñska, J; Kowalska, MM; Nowacki, MP; Chwaliñski, MG; Rysiñska, A. et al. CRP, TNFα, IL-1ra, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-30 in blood serum of colorectal cancer patients. Pathology and Oncology Research. 2000, 6, 38-41. [CrossRef]

- Eiró, N; Bermudez-Fernandez, S; Fernandez-Garcia, B; Atienza, S; Beridze, N. et al. Analysis of the expression of interleukins, interferon β, and nuclear factor-κ B in prostate cancer and their relationship with biochemical recurrence. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2014, 37(7), 366-373. [CrossRef]

- Merlot, E; Moze, E; Dantzer, R; Neveu, PJ. Cytokine Production by Spleen Cells after Social Defeat in Mice: Activation of T Cells and Reduced Inhibition by Glucocorticoids. Stress. 2004, 7(1), 55-61. [CrossRef]

- Spoto, B; Zoccali, C. Spleen IL-10, a key player in obesity-driven renal risk. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2013, 28(5), 1061-1064. [CrossRef]

- Borba, VV; Zandman-Goddard, G; Shoenfeld, Y. Prolactin and autoimmunity: The hormone as an inflammatory cytokine. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019, 33(6), 101324. [CrossRef]

- Maggio, M; Basaria, S; Ceda, GP; Ble, A; Ling, SM; et al. The relationship between testosterone and molecular markers of inflammation in older men. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005, 28(11,116–119. PMID: 16760639.

- Zermann, DH; Ishigooka, M; Doggweiler, R; Schubert, J; Schmidt, RA. Central nervous system neurons labeled following the injection of pseudorabies virus into the rat prostate gland. Prostate. 2000, 44(3), 240-247. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C; Giuliano, F; Yaici, ED; Conrath, M; Trassard, O; et al. Identification of lumbar spinal neurons controlling simultaneously the prostate and the bulbospongiosus muscles in the rat. Neuroscience. 2006, 138(2), 561-573. [CrossRef]

- Yaici, E; Rampin, R; Tang, Y; Calas, A; Jestin, A; et al. Catecholaminergic projections onto spinal neurons destined to the pelvis including the penis in rat. Int J Impot Res. 2002, 14(3), 151-166. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, ME; Clapp, C; de la Escalera, GM; Torner, LM. Dopamine escape potentiation of prolactin release may involve the activation of calcium channels by protein kinases A y C. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;2(1), 779–86.

- De Marzo, AM; Platz, EA; Sutcliffe, S; Xu, J; Grönberg, H; et al. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2007, 7(4), 256-269. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Microphotograph of the ventral prostate (VP) from a rat, stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin. The tubuloalveolar glands in different experimental groups are observed: Sham: A normal pseudostratified epithelium is seen, composed of columnar epithelial cells (EC) with clearly defined nuclei (N), nucleolus (Nc), Golgi apparatus (GA), lumen (Lu), stroma (S), apical zone (Az), basal zone (Bz) and a blood vessel (Bv). HgN (Hypogastric nerve section): The epithelium shows characteristics like the Sham group, but with an enlarged blood vessel and stroma with leukocyte (Lk) infiltration. PvN (Pelvic nerve section): The epithelial cells are more elongated, the Golgi apparatus is not clearly visible, and the stroma is enlarged, also containing leukocytes. HgN+PvN (Both nerves section): A disorganized epithelium is observed, with cylindrical cells, a fusiform stroma, and leukocytes present in both the stroma and lumen.

Figure 1.

Microphotograph of the ventral prostate (VP) from a rat, stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin. The tubuloalveolar glands in different experimental groups are observed: Sham: A normal pseudostratified epithelium is seen, composed of columnar epithelial cells (EC) with clearly defined nuclei (N), nucleolus (Nc), Golgi apparatus (GA), lumen (Lu), stroma (S), apical zone (Az), basal zone (Bz) and a blood vessel (Bv). HgN (Hypogastric nerve section): The epithelium shows characteristics like the Sham group, but with an enlarged blood vessel and stroma with leukocyte (Lk) infiltration. PvN (Pelvic nerve section): The epithelial cells are more elongated, the Golgi apparatus is not clearly visible, and the stroma is enlarged, also containing leukocytes. HgN+PvN (Both nerves section): A disorganized epithelium is observed, with cylindrical cells, a fusiform stroma, and leukocytes present in both the stroma and lumen.

Figure 2.

Microphotograph of the dorsolateral prostate (DPL) from a rat, stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin. The tubuloalveolar glands in different experimental groups are observed: - Sham: A normal pseudostratified epithelium is seen, composed of cuboidal epithelial cells (EC), with well-defined nuclei (N) and Golgi apparatus (GA), lumen (Lu), stroma (S), and a blood vessel (BV). HgN (Hypogastric nerve section): The epithelium appears flattened, with an enlarged stroma and the presence of leukocytes (Lk) in both the stroma and lumen. PvN (Pelvic nerve section): The alveoli display elongated epithelial cells, with the Golgi apparatus still visible, and an enlarged stroma containing leukocytes. HgN+PvN (Both nerves section): A disorganized epithelium with cylindrical cells is observed, a fusiform stroma and an abundant presence of leukocytes in the lumen.

Figure 2.

Microphotograph of the dorsolateral prostate (DPL) from a rat, stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin. The tubuloalveolar glands in different experimental groups are observed: - Sham: A normal pseudostratified epithelium is seen, composed of cuboidal epithelial cells (EC), with well-defined nuclei (N) and Golgi apparatus (GA), lumen (Lu), stroma (S), and a blood vessel (BV). HgN (Hypogastric nerve section): The epithelium appears flattened, with an enlarged stroma and the presence of leukocytes (Lk) in both the stroma and lumen. PvN (Pelvic nerve section): The alveoli display elongated epithelial cells, with the Golgi apparatus still visible, and an enlarged stroma containing leukocytes. HgN+PvN (Both nerves section): A disorganized epithelium with cylindrical cells is observed, a fusiform stroma and an abundant presence of leukocytes in the lumen.

Figure 3.

Percentage of total leukocytes (CD45+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. Preganglionic axotomy of the pelvic and/or hypogastric nerves significantly increases the number of leukocytes (CD45+) in both prostate lobes, with the effect being more pronounced in the combined denervation of both nerves. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Percentage of total leukocytes (CD45+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. Preganglionic axotomy of the pelvic and/or hypogastric nerves significantly increases the number of leukocytes (CD45+) in both prostate lobes, with the effect being more pronounced in the combined denervation of both nerves. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Percentage of total lymphocytes T (CD3+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. In the ventral prostate, preganglionic axotomy of the pelvic nerve and denervation of both nerves significantly increased the percentage of lymphocytes T (CD3+). In the dorsolateral prostate, all preganglionic denervations significantly increased the percentage of total lymphocytes T (CD3+), while the sham surgery induced a decrease in this percentage. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Percentage of total lymphocytes T (CD3+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. In the ventral prostate, preganglionic axotomy of the pelvic nerve and denervation of both nerves significantly increased the percentage of lymphocytes T (CD3+). In the dorsolateral prostate, all preganglionic denervations significantly increased the percentage of total lymphocytes T (CD3+), while the sham surgery induced a decrease in this percentage. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Percentage of total T cytotoxic lymphocytes (CD8+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. Preganglionic injury to the pelvic and/or hypogastric nerves significantly increases the number of T cytotoxic lymphocytes (CD8+) in both prostate lobes, with the effect being less pronounced with the pelvic nerve. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 5.

Percentage of total T cytotoxic lymphocytes (CD8+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. Preganglionic injury to the pelvic and/or hypogastric nerves significantly increases the number of T cytotoxic lymphocytes (CD8+) in both prostate lobes, with the effect being less pronounced with the pelvic nerve. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 6.

Percentage of T helper lymphocytes (CD4+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. Preganglionic injury to the pelvic and/or hypogastric nerves significantly increases the percentage of T helper lymphocytes (CD4+) in both prostate lobes, with a cumulative effect observed in the dorsolateral prostate when both nerves are denervated. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 6.

Percentage of T helper lymphocytes (CD4+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. Preganglionic injury to the pelvic and/or hypogastric nerves significantly increases the percentage of T helper lymphocytes (CD4+) in both prostate lobes, with a cumulative effect observed in the dorsolateral prostate when both nerves are denervated. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 7.

Percentage of lymphocytes B (CD19+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. Preganglionic injury to the pelvic and/or hypogastric nerves significantly increases the percentage of lymphocytes B (CD19+) in both prostate lobes, with a cumulative effect observed in the ventral prostate when both nerves are denervated. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 7.

Percentage of lymphocytes B (CD19+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. Preganglionic injury to the pelvic and/or hypogastric nerves significantly increases the percentage of lymphocytes B (CD19+) in both prostate lobes, with a cumulative effect observed in the ventral prostate when both nerves are denervated. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 8.

Percentage of macrophages (CD11b+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. Preganglionic injury to the pelvic and/or hypogastric nerves significantly increases the percentage of macrophages (C11b+) in both prostate lobes when both nerves are denervated. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 8.

Percentage of macrophages (CD11b+) in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate from intact and denervated rats. Preganglionic injury to the pelvic and/or hypogastric nerves significantly increases the percentage of macrophages (C11b+) in both prostate lobes when both nerves are denervated. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the intact group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 9.

Serum levels of interleukins in intact and denervated rats. The figure shows that preganglionic double denervation significantly increases the blood levels of all analyzed interleukins. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the control group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 9.

Serum levels of interleukins in intact and denervated rats. The figure shows that preganglionic double denervation significantly increases the blood levels of all analyzed interleukins. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the control group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 10.

Serum levels of prolactin in intact and denervated rats. The figure shows that preganglionic denervation of hypogastric nerve induces a significative decrease in serum prolactin while increase its levels when both nerves are denervated. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the control group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 10.

Serum levels of prolactin in intact and denervated rats. The figure shows that preganglionic denervation of hypogastric nerve induces a significative decrease in serum prolactin while increase its levels when both nerves are denervated. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the control group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 11.

Serum levels of testosterone in intact and denervated rats. The figure shows that preganglionic denervation of pelvic nerve induces a significative increase in serum testosterone levels and the effect is potentiated when both nerves are denervated. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the control group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

Figure 11.

Serum levels of testosterone in intact and denervated rats. The figure shows that preganglionic denervation of pelvic nerve induces a significative increase in serum testosterone levels and the effect is potentiated when both nerves are denervated. Significant differences are shown in comparison to the control group (**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001**).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).