1. Introduction

Commercial aircraft manufacturing represents a technology-intensive, capital-intensive, and labor-intensive industry[

1]. Modular partitioning stands as a critical technology in aircraft design and manufacturing, enabling efficient system design, production, assembly, and maintenance through decomposition of complex systems into functionally independent modules. The rationality of module division directly impacts aircraft functionality, performance, and overall cost. Current research predominantly focuses on theoretical concepts of modular partitioning for complex products like commercial aircraft, with limited development of mature modular division models in practical applications[

2,

3].

Tsai et al. approached complex product module division from a functional perspective[

4]. They developed a module division methodology by analyzing interfaces and functional relationships during complex product design, while considering the complexity of design, manufacturing, and assembly . Wei et al. established a multi-criteria module division mathematical model, solved it using multi-objective evolutionary algorithms, and employed fuzzy set evaluation methods to identify optimal solutions for platform-based design of complex products[

5] . Chen Y.H. et al. proposed a maximum-minimum division method: initial grouping based on maximum division criteria, followed by cluster analysis using minimum division units within the subsets formed by maximum division[

6]. The final module division scheme was determined based on aggregation degrees between modules . However, these existing module division methods for complex products fail to meet the requirements of commercial aircraft module partitioning due to their inherent limitations.

The modularization of commercial aircraft can result in different modularization schemes based on functional characteristics, functional hierarchy, structural components, assembly processes, data management, and interface standards. These aspects focus on different priorities, and there is currently no unified evaluation model to assess the rationality and scientific nature of these modularization schemes. In this paper, based on the research of modularization methods for complex systems, a fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method is established to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the modularization schemes for commercial aircraft. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation (FCE), as a multi-factor evaluation method based on fuzzy mathematics, has gradually become an important tool for solving complex decision-making problems due to its unique advantages in dealing with uncertainties and fuzziness among evaluation indicators. FCE, grounded in the theory of fuzzy mathematics, can effectively address issues that are difficult to judge precisely due to the fuzziness and uncertainty of evaluation indicators[

7,

8]. For example, hierarchical fuzzy comprehensive evaluation optimizes the evaluation process through a hierarchical structure, effectively solving the problem of excessive fuzziness caused by a large set of indicators. The fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method combined with the AHP further enhances the scientific and rational setting of weights. The grey fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method, by introducing grey system theory, enhances the model's adaptability in dealing with incomplete information and uncertainties. Although these improved methods have optimized the performance of FCE to some extent, they have certain limitations in terms of model complexity and computational load. The AHP-Grey Fuzzy Evaluation model established in this paper, by integrating AHP, grey system theory, and FCE, can effectively handle multi-factor, multi-criteria decision-making problems in complex systems and guide the scientific conduct of modularization work for domestic commercial aircraft. The model has the following advantages:

It has significant advantages in terms of scientific nature and adaptability, integrating the strengths of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), grey system theory, and Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation (FCE). It can simultaneously handle indicator weights, uncertainties, and fuzziness. It also has the benefits of high computational complexity and reducing subjective biases in expert scoring, thereby enhancing the scientific nature and accuracy of the evaluation object.

It can effectively deal with multi-factor, multi-criteria decision-making problems in complex systems, ensuring that complex system products with multiple objectives and requirements obtain the optimal solution.

2. The Analytic Hierarchy Process - Grey Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Model

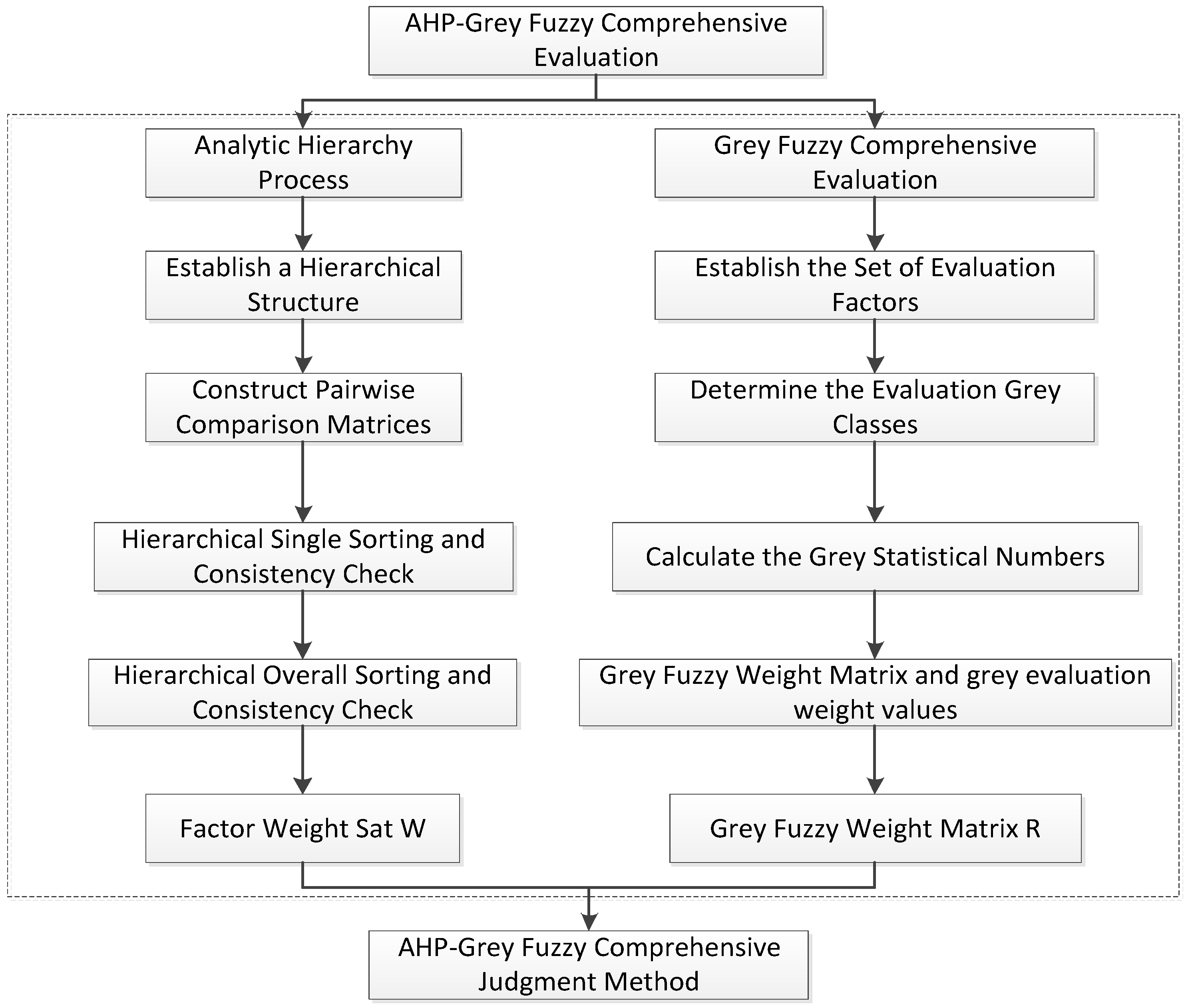

The Analytic Hierarchy Process - Grey Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Model [

9] mainly consists of two parts: the AHP and the Grey Fuzzy Evaluation System. The AHP is used to determine the weights of each evaluation criterion. By constructing a judgment matrix and quantifying the relative importance of each criterion through expert scoring, the weights are calculated. Grey system theory is primarily used to deal with the uncertainty of data and the incompleteness of information. Through grey relational analysis, the degree of correlation between each scheme and the ideal scheme is calculated. The Grey Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation is carried out on the basis of the AHP. The two complement each other and together enhance the scientific nature, reliability, and effectiveness of the evaluation. The overall evaluation approach is shown in

Figure 1.

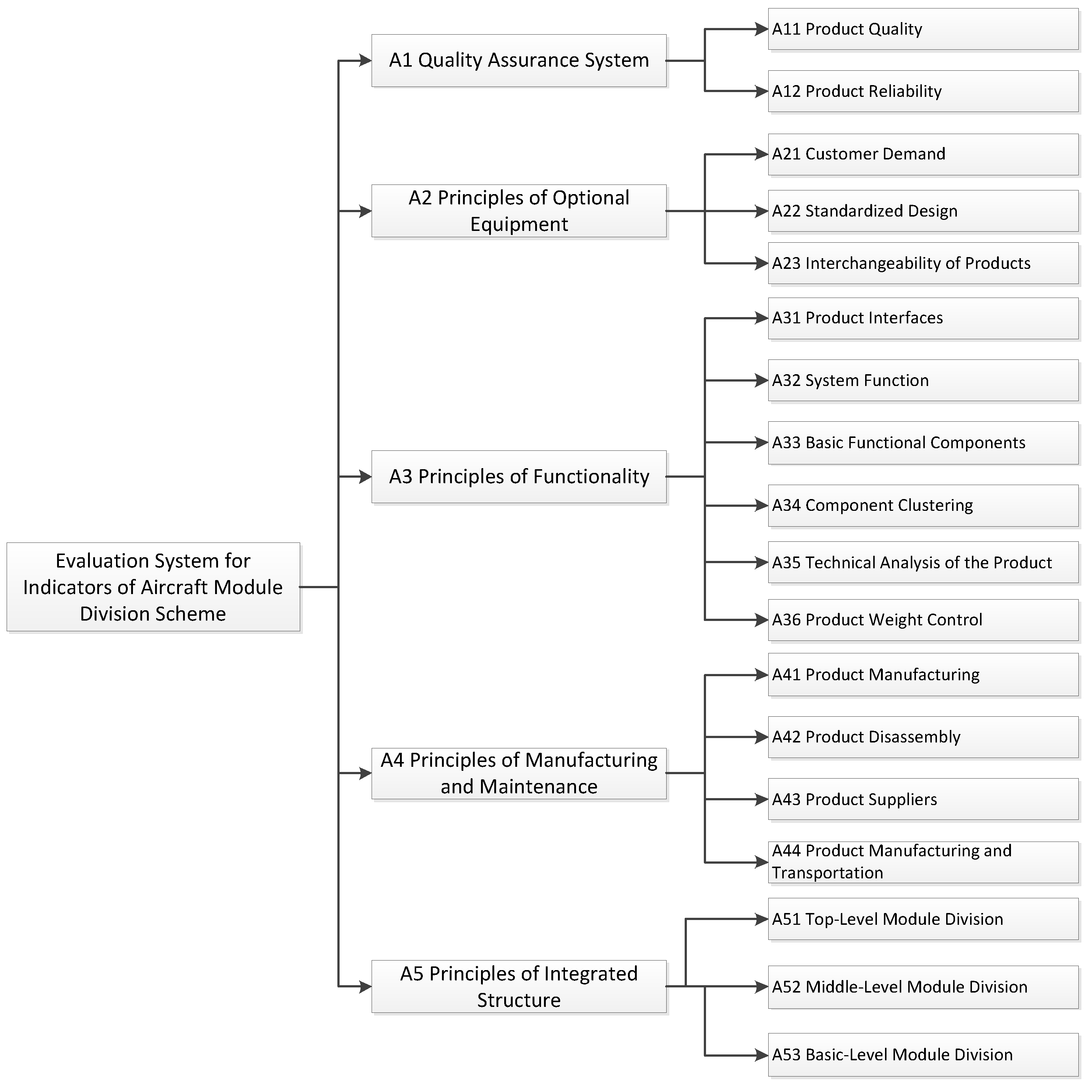

Before determining the weights of the evaluation indicators for the modularization scheme of commercial aircraft, it is necessary to establish a corresponding evaluation indicator system. Through research on domestic and foreign related materials, the modularization of commercial aircraft mainly focuses on five key indicators: product quality reliability, product accessory selection, product functionality, manufacturing and maintenance, and overall product structure composition[

10]. These five key indicators can further be divided into eighteen sub-indicators. The evaluation indicator system for the modularization scheme of commercial aircraft is established based on this, as shown in

Figure 2.

2.1. Hierarchical Single Sorting and Consistency Check

Based on the fundamental calculation principles of the AHP, the consistency index of each level's judgment matrix is calculated. To verify the consistency of the judgment matrix, the Consistency Ratio (CR) is introduced. The larger the CR, the worse the consistency of the matrix. The Consistency Index (CI) is defined as:,where λmax is the maximum eigenvalue of the judgment matrix, and n is the order of the matrix.The Random Consistency Index (RI) is a value that depends on the order of the matrix. The CR is calculated as: ,If CR < 0.1, the consistency of the judgment matrix is considered satisfactory. If the judgment matrix has significant deviations and the evaluation results are unreasonable, the judgment matrix should be adjusted accordingly. The specific calculation results are as follows.

Table 1.

Computatuion of index entry judgement matrix, weight and CR.

Table 1.

Computatuion of index entry judgement matrix, weight and CR.

| Index |

A1 |

A2 |

A3 |

A4 |

A5 |

Weight |

| A1 |

1 |

7 |

3 |

3 |

5 |

0.46 |

| A2 |

1/7 |

1 |

1/3 |

1/3 |

5 |

0.08 |

| A3 |

1/3 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

0.26 |

| A4 |

1/3 |

3 |

1/3 |

1 |

3 |

0.15 |

| A5 |

1/5 |

1/3 |

1/5 |

1/3 |

1 |

0.05 |

|

|

Similarly, the calculations for indicators A2, A3, A4, and A5 show that their Consistency Ratios (CR) are all less than or equal to 0.10. Therefore, the judgment matrices meet the requirement for consistency.

Table 2.

Computatuion of A1 index entry judgement matrix,weight and CR.

Table 2.

Computatuion of A1 index entry judgement matrix,weight and CR.

| Index |

A11 |

A12 |

Weight |

| A11 |

1 |

7 |

0.46 |

| A12 |

1/7 |

1 |

0.08 |

|

|

Table 3.

Computatuion of A2 index entry judgement matrix,weight and CR.

Table 3.

Computatuion of A2 index entry judgement matrix,weight and CR.

| Index |

A21 |

A22 |

A23 |

Weight |

| A21 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

0.66 |

| A22 |

1/3 |

1 |

1 |

0.18 |

| A23 |

1/5 |

1 |

1 |

0.16 |

|

|

Table 4.

Computatuion of A3 index entry judgement matrix,weight and CR.

Table 4.

Computatuion of A3 index entry judgement matrix,weight and CR.

| Index |

A31 |

A32 |

A33 |

A34 |

A35 |

A36 |

Weight |

| A31 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

6 |

5 |

7 |

0.44 |

| A32 |

1/3 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

4 |

6 |

0.25 |

| A33 |

1/4 |

1/2 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0.14 |

| A34 |

1/6 |

1/5 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0.07 |

| A35 |

1/5 |

1/4 |

1/3 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0.07 |

| A36 |

1/7 |

1/6 |

1/4 |

1/3 |

1/3 |

1 |

0.03 |

| |

|

Table 5.

Computatuion of A4 index entry judgement matrix,weight and CR.

Table 5.

Computatuion of A4 index entry judgement matrix,weight and CR.

| Index |

A41 |

A42 |

A43 |

A44 |

Weight |

| A41 |

1 |

1 |

1/3 |

2 |

0.20 |

| A42 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

0.19 |

| A43 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

0.46 |

| A44 |

1/2 |

1 |

1/3 |

1 |

0.15 |

|

|

Table 6.

Computatuion of A5 index entry judgement matrix,weight and CR.

Table 6.

Computatuion of A5 index entry judgement matrix,weight and CR.

| Index |

A51 |

A52 |

A53 |

Weight |

| A51 |

1 |

1/2 |

1/3 |

0.17 |

| A52 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0.39 |

| A53 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0.44 |

|

|

2.2. Determining Indicator Weights

Hierarchical total sorting refers to the calculation of the relative importance of each factor in a certain level with respect to all factors in the upper level. Since hierarchical total sorting is conducted from the highest level to the lowest level, it also represents the calculation of the relative importance of each factor in a certain level with respect to the highest level. The hierarchical total sorting can then be obtained based on the results of hierarchical single sorting. The results are shown in the

Table 7.

2.3. Determining Evaluation Grades

Evaluation grades are used to classify and compare the comprehensive performance of the evaluated objects by dividing them into several levels. Typically, these levels are divided into four categories: "Good," "Fairly Good," "Average," and "Poor." The scores for each level are determined using the expert scoring method, with a 10-point scale. The scores for each grade are as follows: C = {10, 7, 5, 2}.

2.4. Determination of the Evaluation Grey Degree

To determine the evaluation grey classes, it is necessary to establish the number of grey classes, the grey numbers, and their whitening weight functions. These elements are crucial for defining the evaluation grey classes. The determination of evaluation grey classes is based on the evaluation grades and relies on qualitative analysis. Let the evaluation value of the k-th member of the evaluation group denoted by for the j-th indicator (j=1,2,…,n) be denoted as . The matrix composed of h is called the sample matrix of the indicator set U.The whitening weight functions selected in this paper are as follows:

a. The gray number of grade Good is expressed as

,Its whitening weight function is:

b. The gray number of grade Fairly Good is expressed ass

,Its whitening weight function is:

c. The gray number of grade Average is expressed ass

,Its whitening weight function is:

d. The gray number of grade Poor is expressed ass

,Its whitening weight function is:

2.5. Determining the Grey Statistical Numbers

After establishing the evaluation grey classes for the four grades, the grey statistical method can be used to calculate the weight

of the j-th evaluation criterion. Additionally, the grey statistics

and total grey statistics

of the evaluation matrix can be obtained by using

The specific calculations are as follows:

2.6. Calculating the Grey Fuzzy Weight Matrix and Grey Evaluation Weight Values

Taking into account the evaluation opinions of r experts on the i-th factor, the grey evaluation weight for the j-th evaluation criterion is obtained as follows:

The single-factor grey fuzzy weight matrix composed of

is shown as follows:

2.6. Calculate the grey fuzzy evaluation matrix

The grey fuzzy evaluation matrix is obtained by compounding the fuzzy weighted matrix and the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation matrix.

Among ,After normalization.

2.6. Calculate the final evaluation result

Calculate the final comprehensive evaluation results:

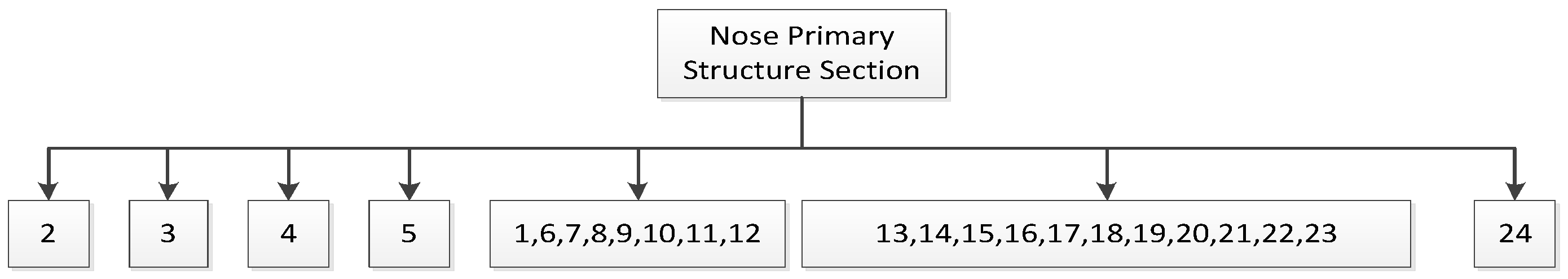

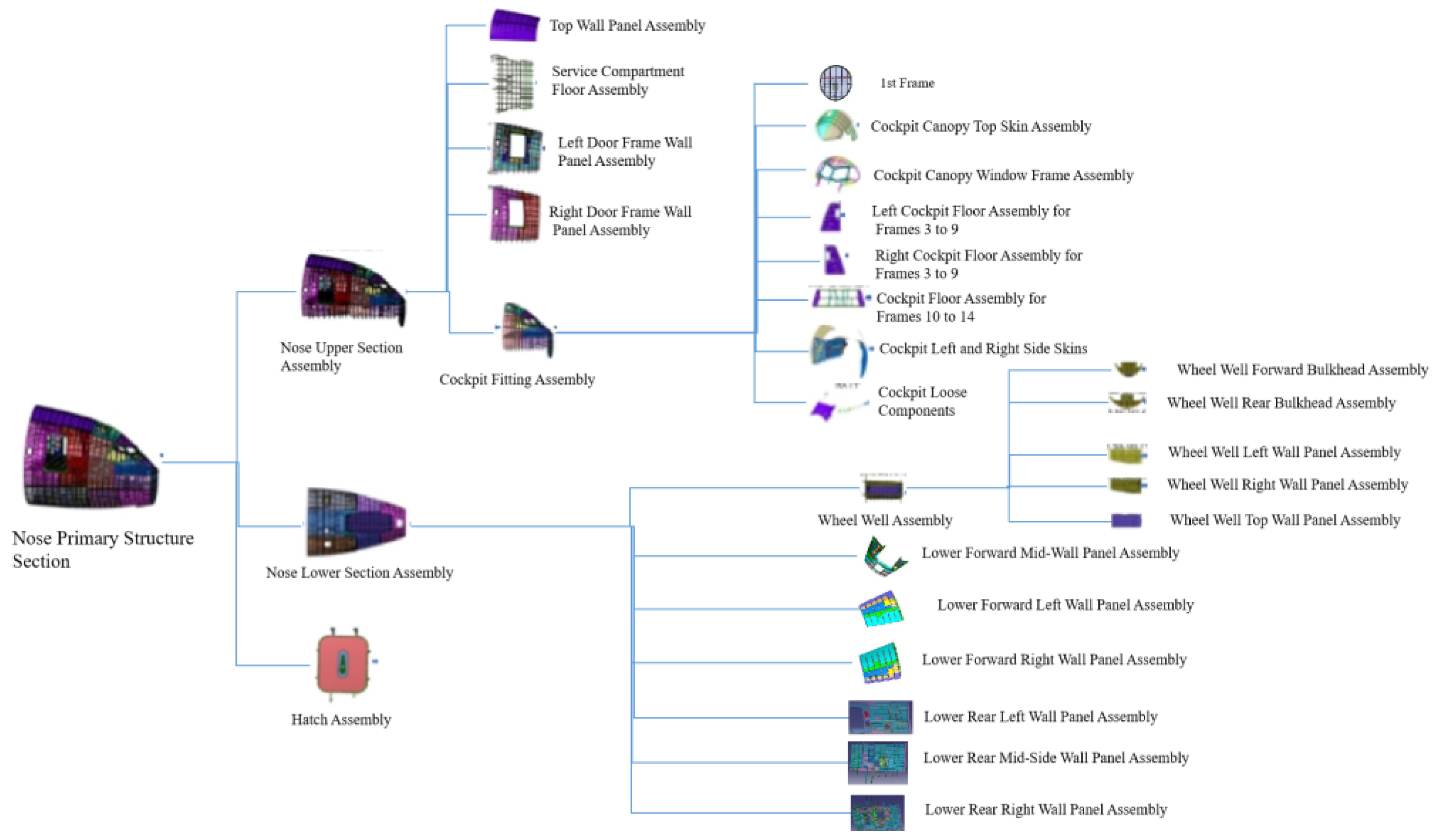

3. Case Study on the Evaluation of Modularization Schemes for the Nose Section Structure of commercial aircraft

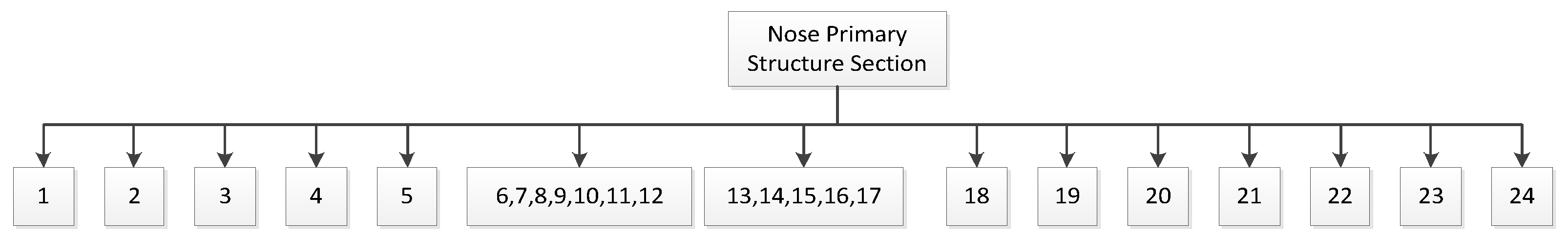

The design and manufacturing of the nose section structure have a profound impact on the overall performance, safety, and economy of an aircraft. A rational nose section structure design can not only enhance the aircraft's aerodynamic performance and structural strength but also facilitate equipment installation and maintenance. Additionally, it meets ergonomic requirements and reduces production and operational costs[

11,

12]. This paper evaluates the modularization schemes for the nose section structure to seek the optimal division plan. The nose section structure includes the 1st frame, cockpit components, Hatch Assembly, and so on. The specific components are mainly shown in the

Table 8.

Based on extensive experience in the design and manufacturing of commercial aircraft nose sections, and integrating the structural functions, processes, and comprehensive optimization approaches of the nose section, three preliminary design schemes for the nose section have been established, as shown in the

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

Experts with extensive experience in civil aircraft design were invited to evaluate the preliminary division schemes A, B, and C. The evaluation sample matrix for each scheme was obtained through expert scoring. Six experts were invited to score each scheme on a 10-point scale. It was stipulated that all members of the evaluation group had the same weight.

The evaluation sample size matrix of Scheme A is shown in the

Table 9. According to the evaluation process, the comprehensive evaluation result Z=6.98 is obtained.It can be seen that 5 < 6.98 < 7, which indicates that Scheme A is between "Fairly Good" and "Average".

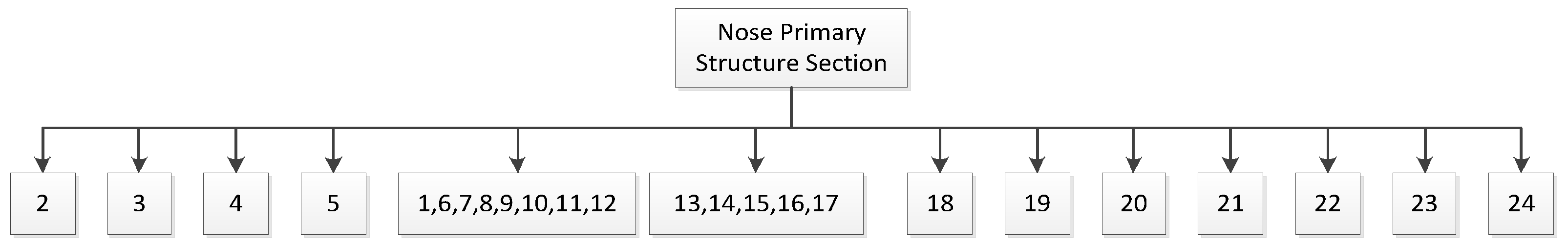

Similarly, the evaluation sample matrix for Scheme B is shown in the

Table 10. The comprehensive evaluation result for Scheme B is Z = 8.15. It can be seen that 7 < 8.15 < 10, which indicates that Scheme B is between the "Good" and "Fairly Good". This suggests that the overall evaluation of Scheme B is relatively high and it can be considered as a potential alternative.

The evaluation sample matrix for Scheme C is shown in the

Table 11. Following the evaluation process, the comprehensive evaluation result for Scheme C is Z = 7.56. It can be seen that 7 < 7.56 < 10, which indicates that Scheme C is between "Good" and "Fairly Good". This suggests that Scheme C can also be considered as a potential alternative.

Based on the final evaluation results obtained for the three schemes, the ranking of the schemes can be determined as follows: 8.15 > 7.56 > 6.98. This means that Scheme B is the optimal scheme, followed by Scheme C, with Scheme A being relatively less favorable. Therefore, it is evident that Scheme B is the best option.Therefore, the structural module division scheme for the forward fuselage section of the commercial aircraft can be obtained as shown in the

Figure 6.

4. Discussion

This study aims to explore the scientific nature of modular division schemes for commercial aircraft. By employing the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) combined with Grey Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation model to assess the modular division schemes of commercial aircraft, we have demonstrated the scientific and rational nature of this model in the modular division of complex products. It holds guiding significance for the modular division of subsequent commercial aircraft and other complex products.

The theoretical contribution of this study lies in proposing the AHP-Grey Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation model, which offers a new perspective for evaluating modular division schemes of complex system products. In practical terms, our findings hold potential value for the modular division of commercial aircraft, such as providing scientific division schemes for various aircraft sections. These insights offer a scientific basis for the modular division of complex system products, especially aircraft.

Despite the achievements of this study, there are certain limitations. First, the relatively small sample size may affect the generalizability of the results. Second, the research methodology has its limitations. For instance, there may be subjective biases in the experts' scoring of the schemes, although we have addressed this through fuzzification. Future research could consider expanding the sample size and adopting more advanced evaluation models to overcome these limitations. Additionally, further studies could explore scientific methods for assessing the modular division schemes of commercial aircraft.

In summary, by establishing the AHP-Grey Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation model to assess the modular division schemes of commercial aircraft, this study has revealed scientific methods for modular division of complex system products and provided new insights into the evaluation of such schemes. Despite its limitations, the findings of this study are significant both theoretically and practically.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to explore the scientific and rational nature of modular division schemes for commercial aircraft. By decomposing complex systems into functionally independent modules, we can achieve efficient design, manufacturing, assembly, and maintenance, thereby enhancing the functionality, performance, and cost-effectiveness of aircraft products. Through the establishment of an AHP - Grey Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation model, using the structural modular division of the forward fuselage section of a commercial aircraft as a case study, we have revealed scientific methods for the modular division of complex system products. These results not only support the feasibility of our evaluation model but also provide a new theoretical perspective and practical guidance for the modular division schemes of complex system products. Although the study has certain limitations, its theoretical contributions and practical significance cannot be overlooked. Future research can further explore the optimization of the AHP - Grey Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation model to expand on the findings of this study.

Author Contributions

methodology and data curation, H.X.; project administration, L.Y. All of the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the modularization special project team at the Shanghai Aircraft Design and Research Institute.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. They have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence their work. The research was conducted independently, and the results are presented without bias.

References

- Zhang, J. C.; Jiang, C. M. Risk of industrial organization strategies in China's commercial aircraft industry. Civil Aircraft Design and Research, 2014, 1, 6-10.

- Gu, X. J., Qi, G. N., Ma, J., Yang, Q. H. Application status and trends of modularization technology. Group Technology & Production Modernization,2012, 29(1), 1-5.

- Tong, S. Z. Modularization principles, design methods, and applications. Beijing: Standards Press of China, 2000, 18-19.

- Tsai, Y.-T., Wang, K.-S. The development of modular-based design in considering technology complexity. European Journal of Operational Research, 1999, 119(3), 692-703. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W., Liu, A., Lu, S. C. Y., Wuest, T. A multi-principle module identification method for product platform design. Journal of Zhejiang University Science A: Applied Physics & Engineering, 2015, 16(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. H., Zhou, D. J., Yuan, H. Y., Feng, Z. J. A Min-Max Partition Modularization Method for Complex Products. Computer Integrated Manufacturing Systems, 2012, 18(1), 9-14.

- Chen,J.F. Ho-Nien Hsieh, Quang H. D.Evaluating teaching performance based on fuzzy AHP and comprehensive evaluation approach, Applied Soft Computing, 2015, 28, 100-108.

- Wei,Y.Y. Zhang,J.Y. Jia Wang. Research on Building Fire Risk Fast Assessment Method Based on Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation and SVM, Procedia Engineering, 2018, 211, 1141-1150. [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.-C., Chien, C.-F., & Wang, M.-J. J. An AHP-based approach to ERP system selection. International Journal of Production Economics, 2005, 96(1), 47–62. [CrossRef]

- Overmeyer, L., Bentlage, A. Small-Scaled Modular Design for Aircraft Wings. New Production Technologies in Aerospace Industry. 2013,55-62.

- George, M. Composites Lift off In Primary Aerostructures, Reinforced Plastics, 2004, 48(4), 22-27.

- J. Wang, A. Baker, P. Chang, Hybrid approaches for aircraft primary structure repairs, Composite Structures, 2019, 207, 190-203. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).