Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

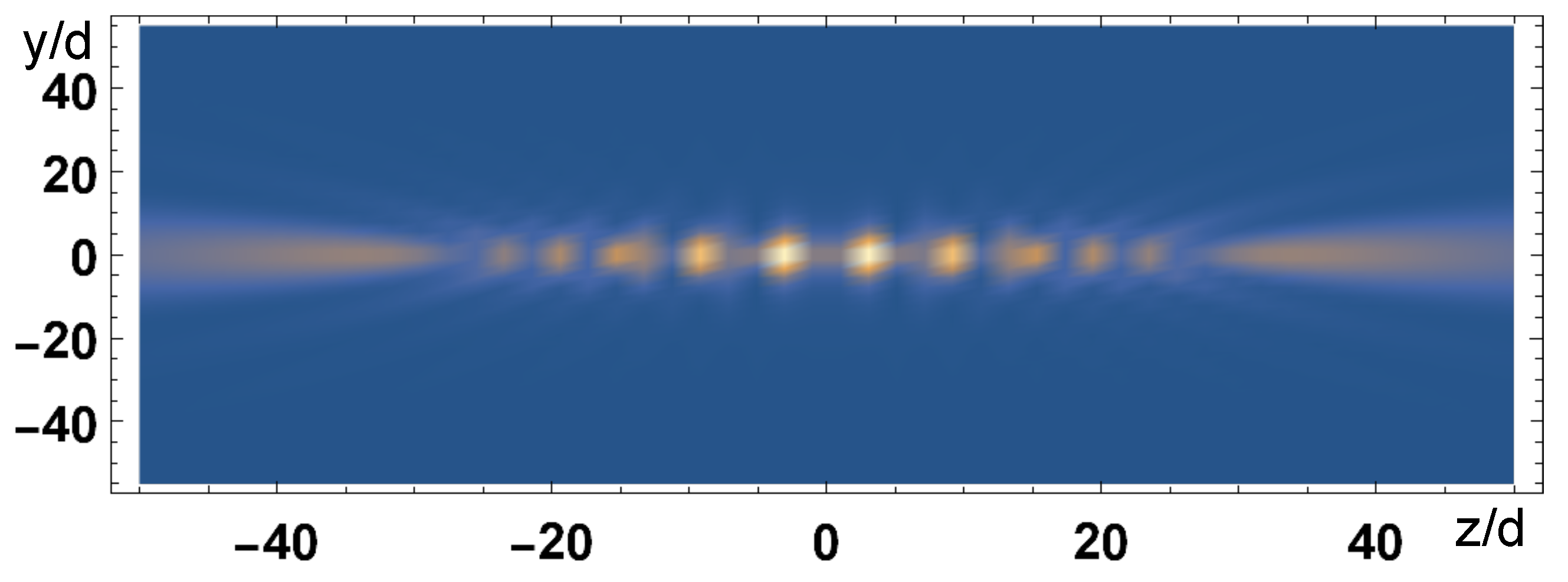

2. Modelling Emission from a Chain of Atom with a Single Excitation

2.1. Scalar Model

2.2. Generalized Dicke State.

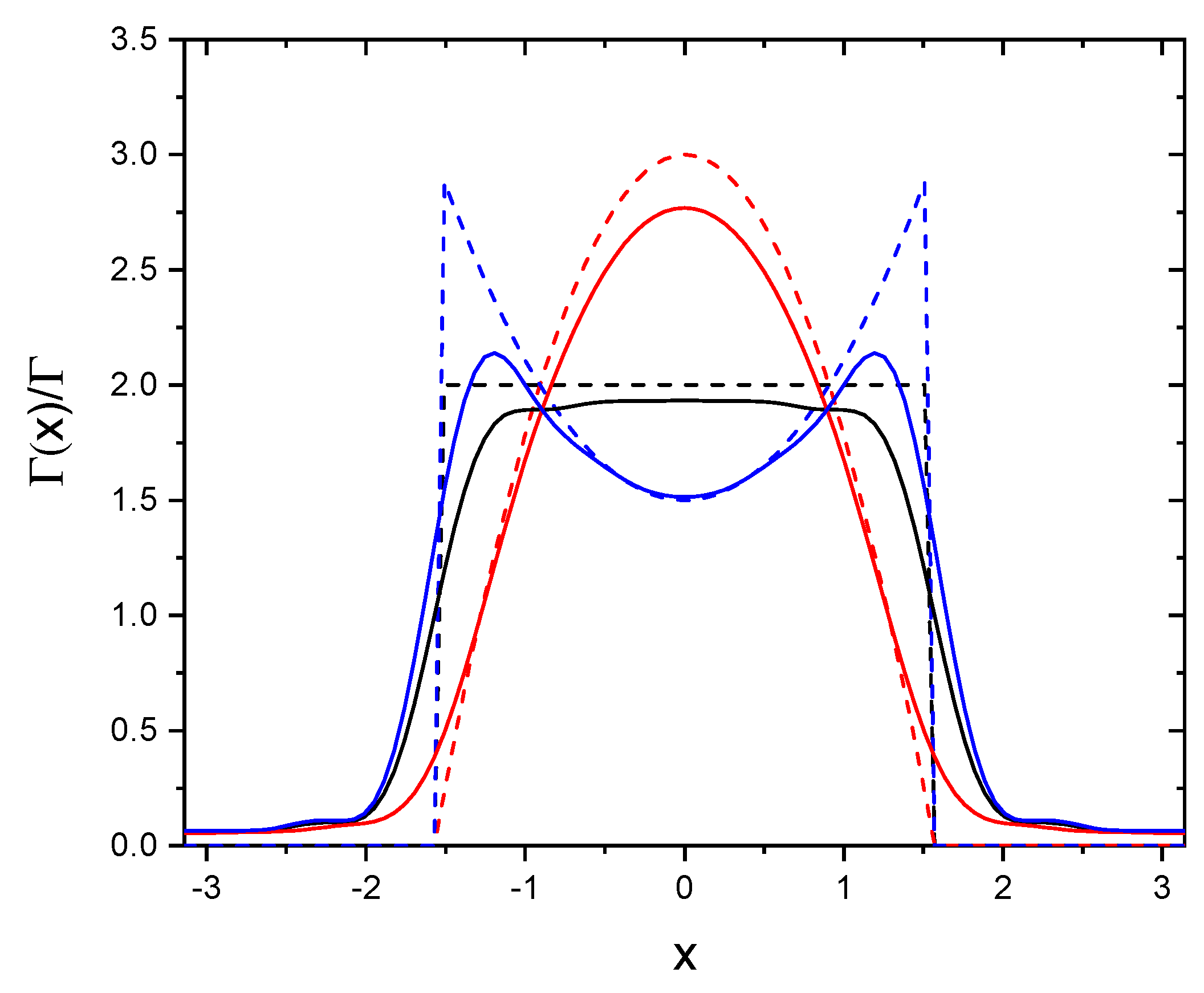

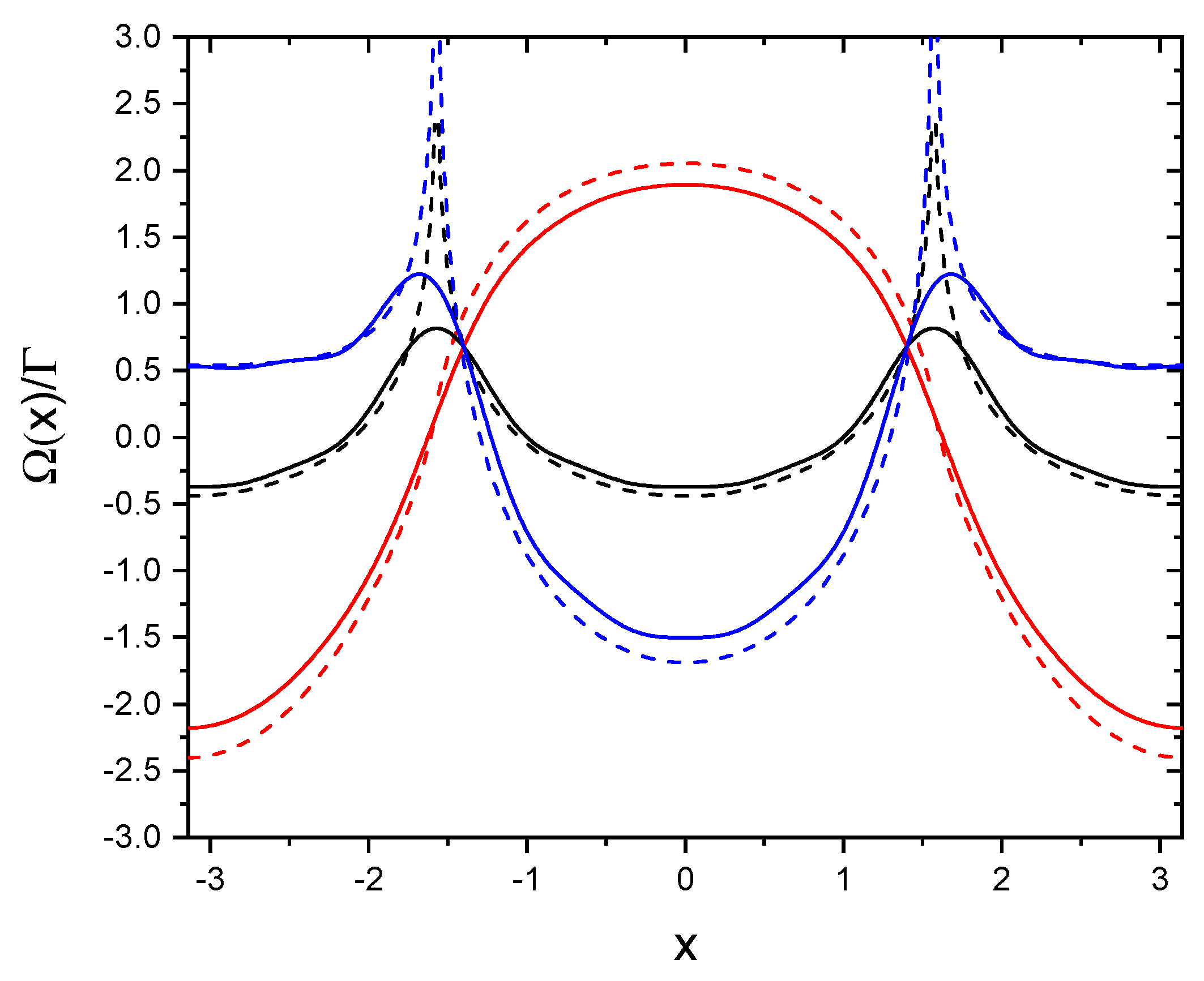

2.3. Collective Frequency Shift and Decay Rate.

2.4. Infinite Chain

2.5. Finite Chain

3. Vectorial Model

4. Dynamics

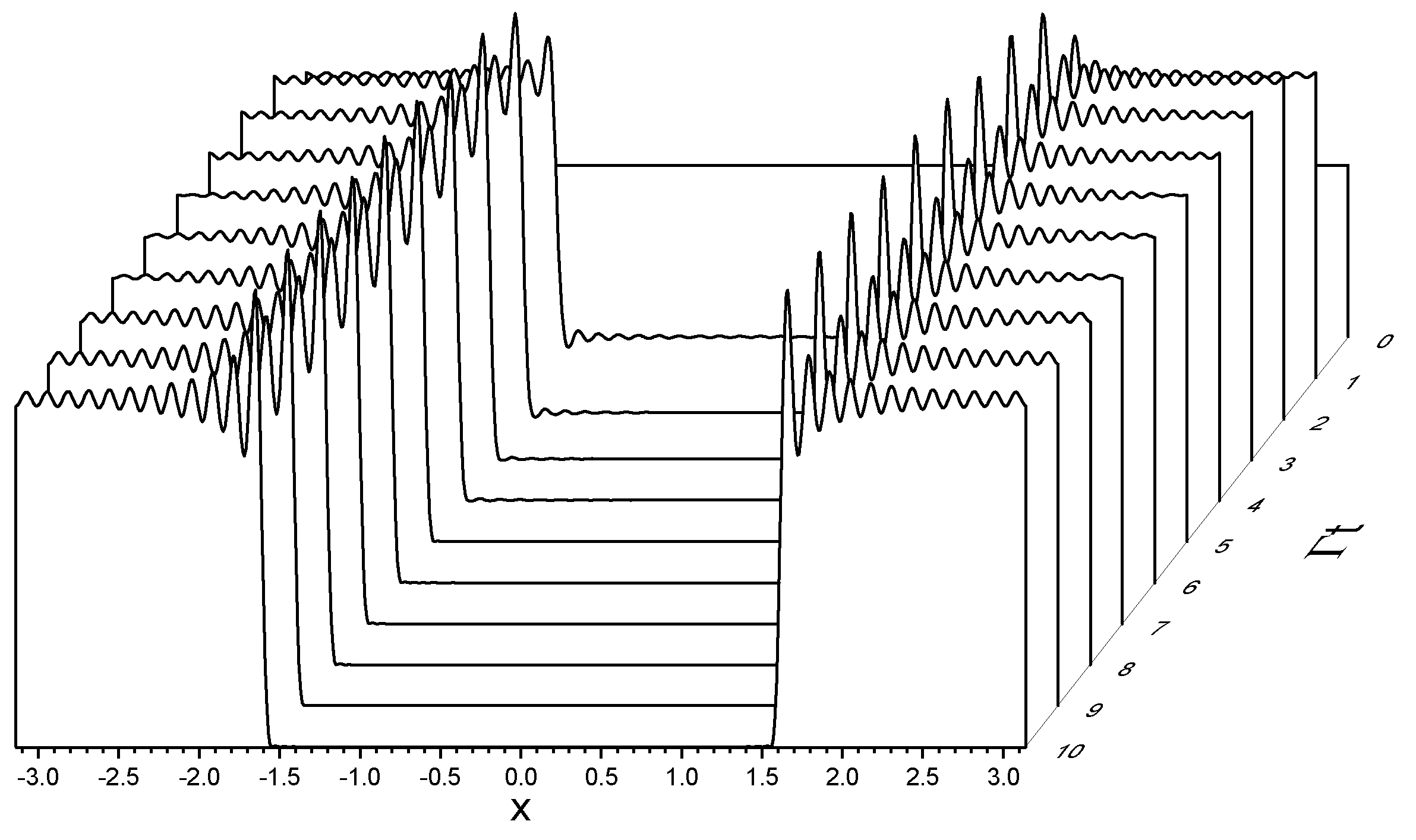

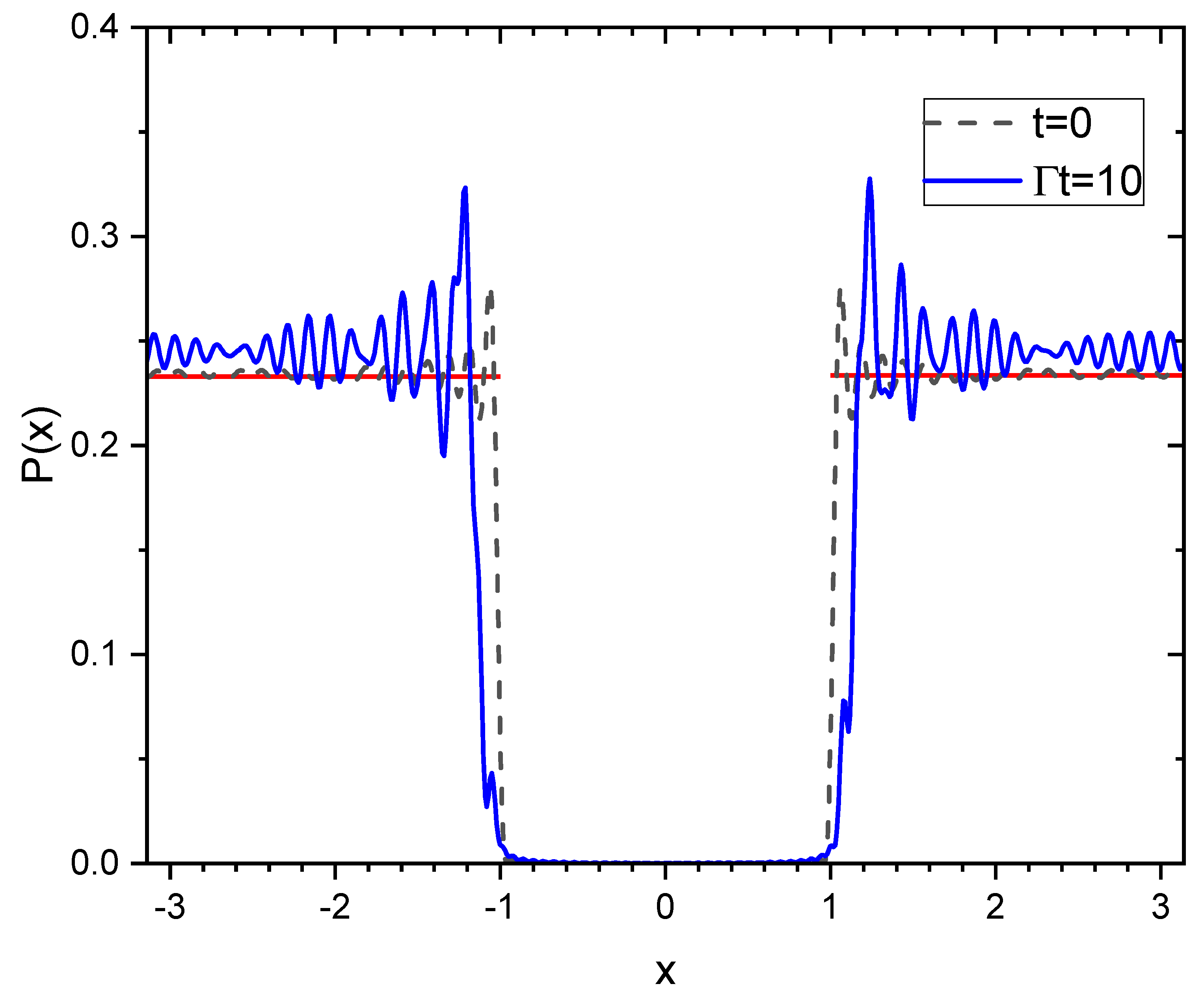

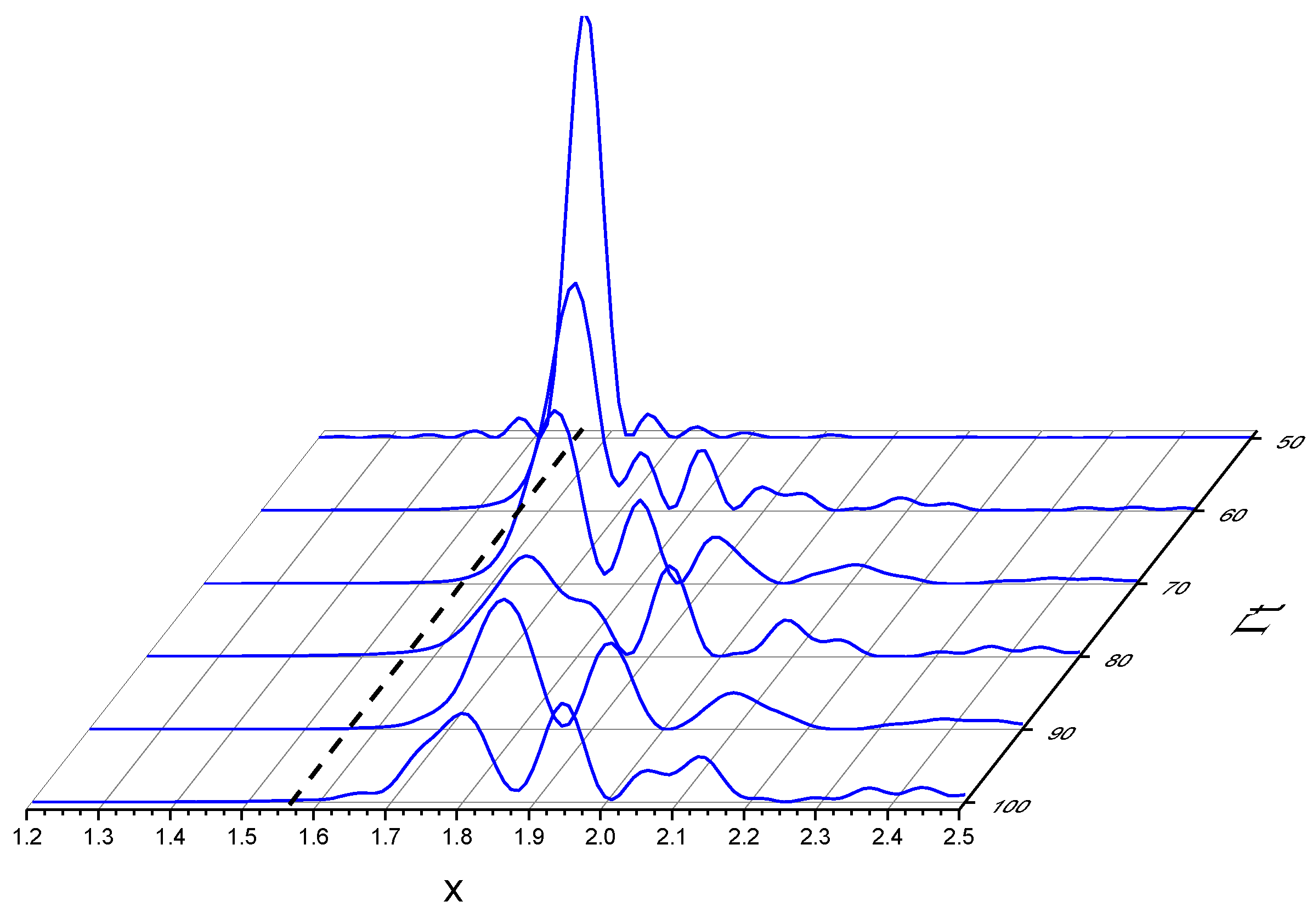

4.1. The Probability Density

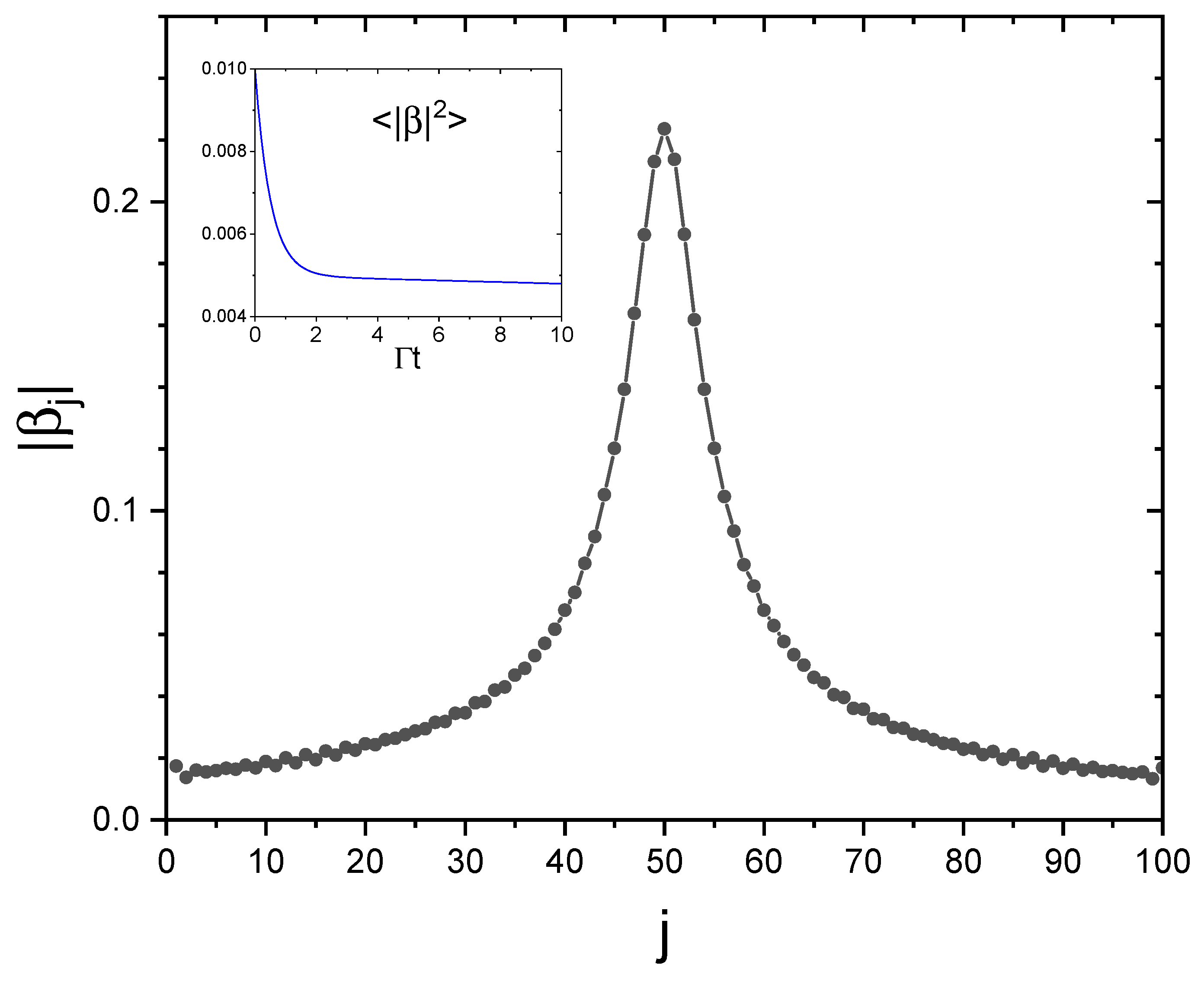

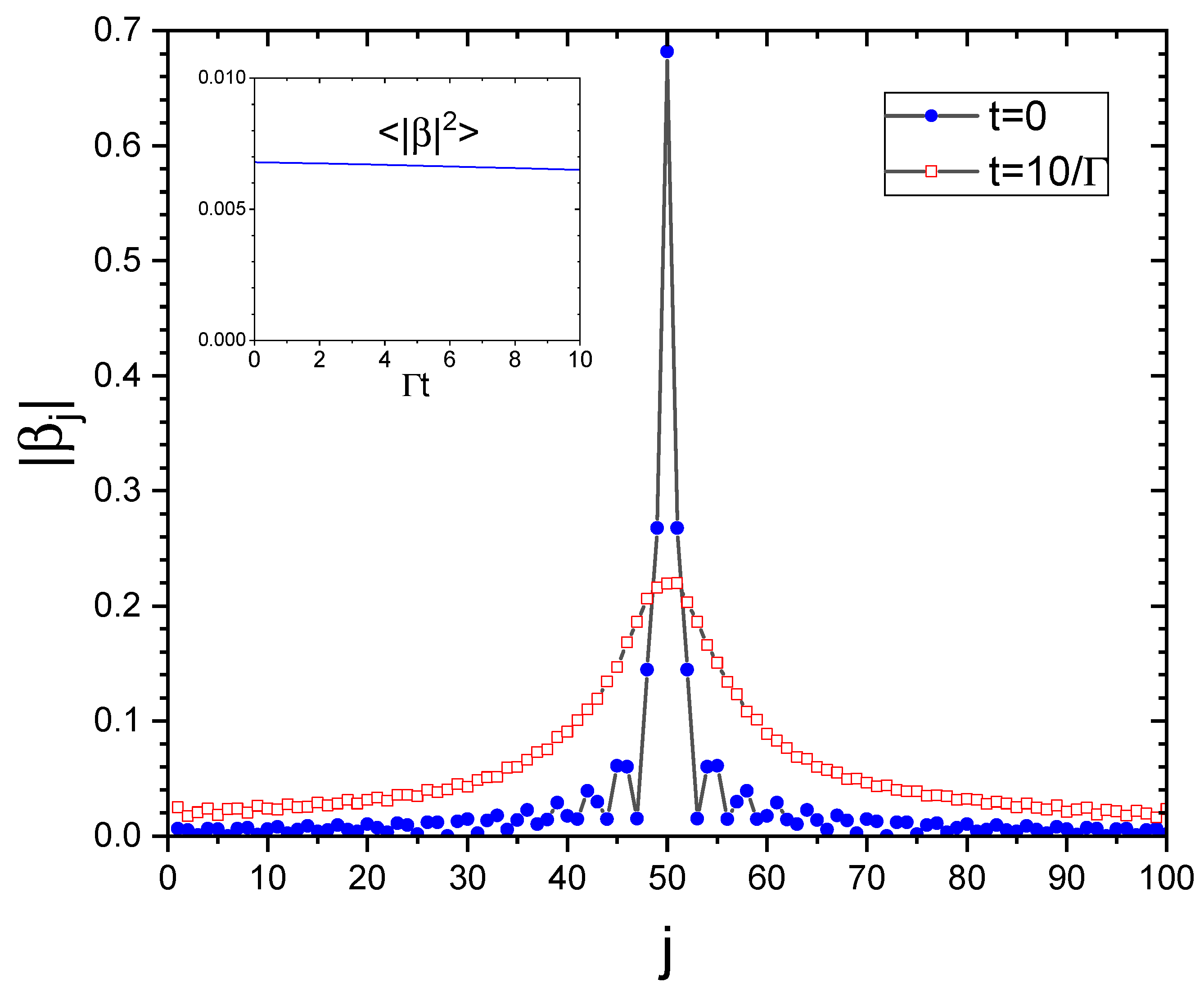

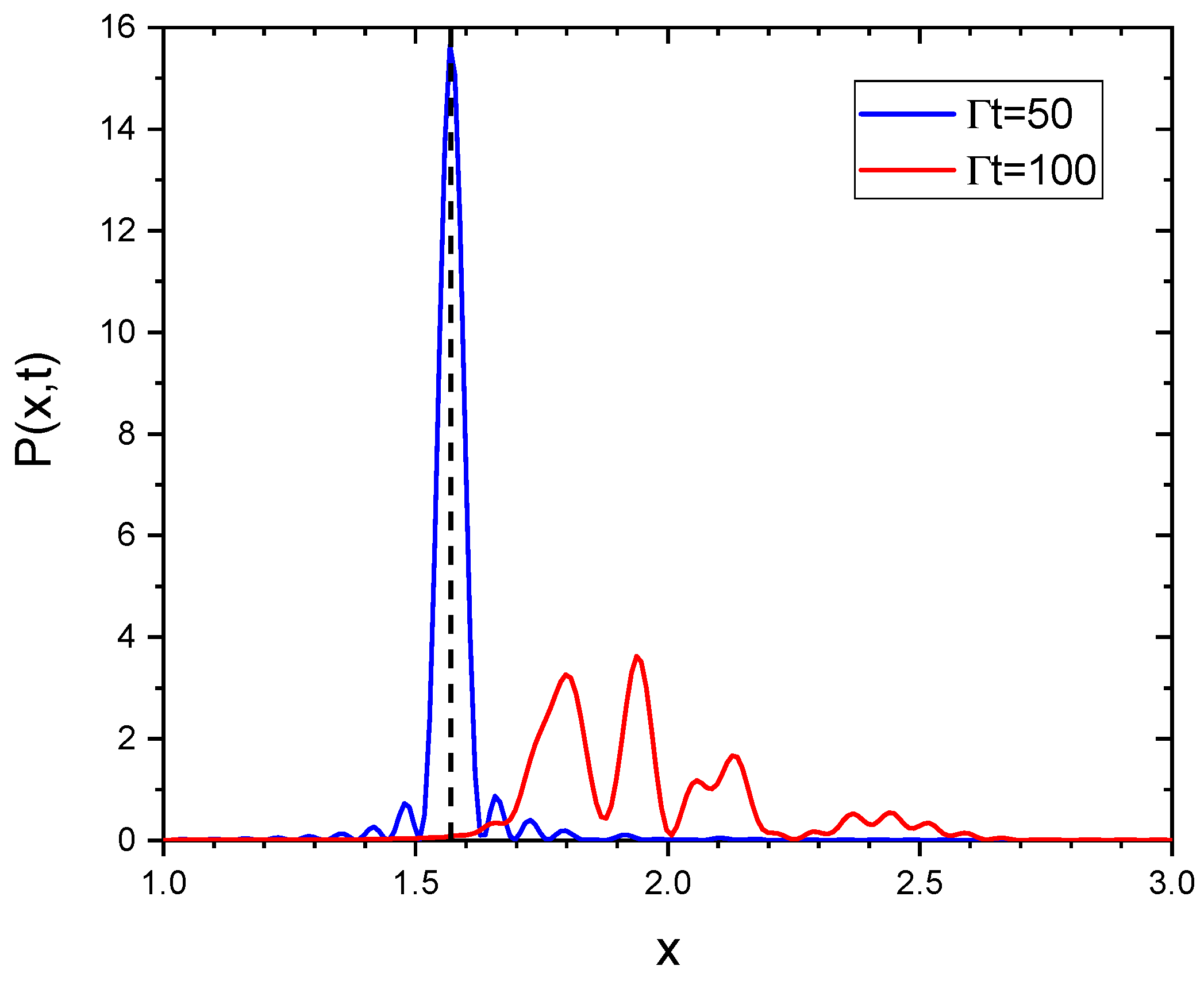

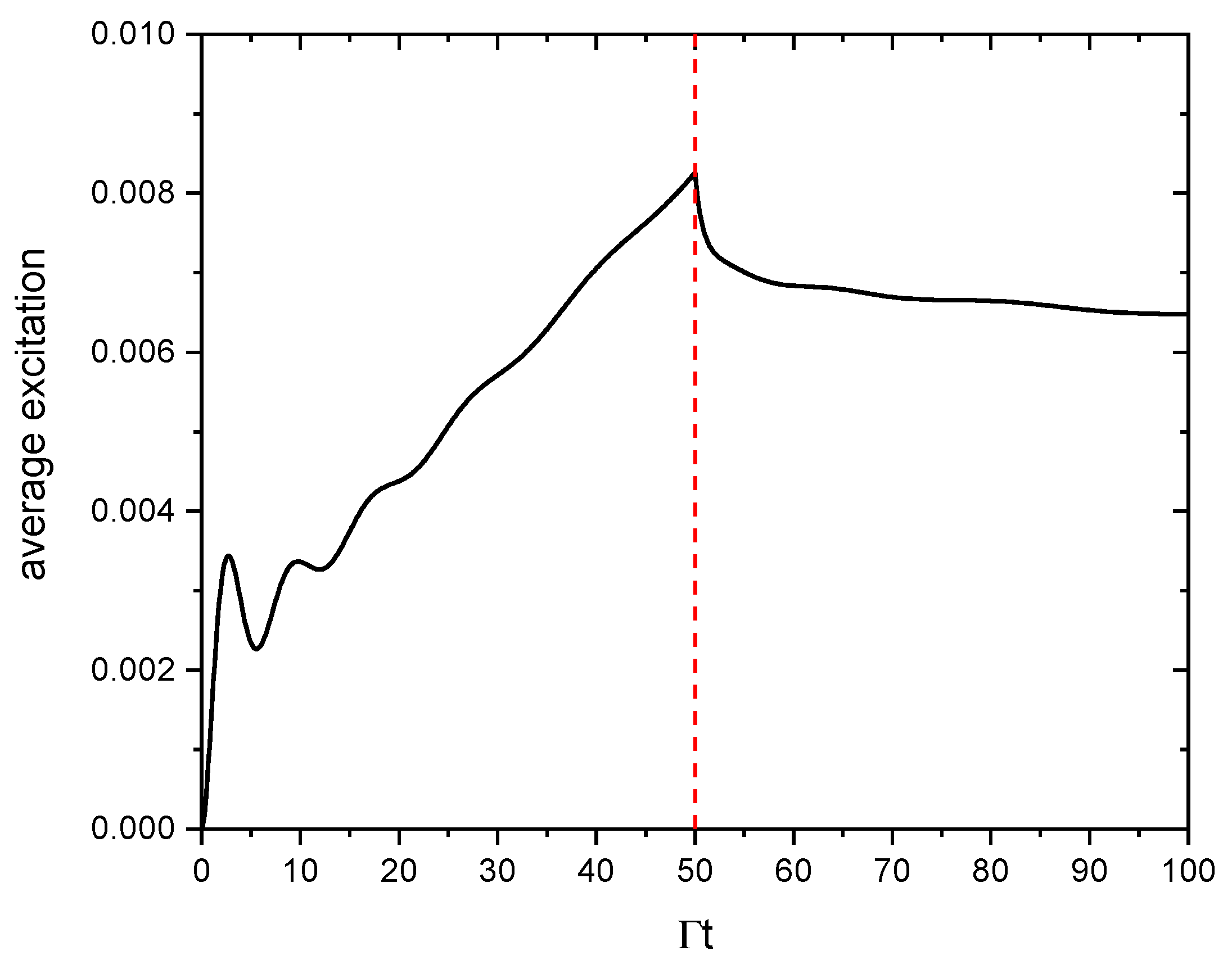

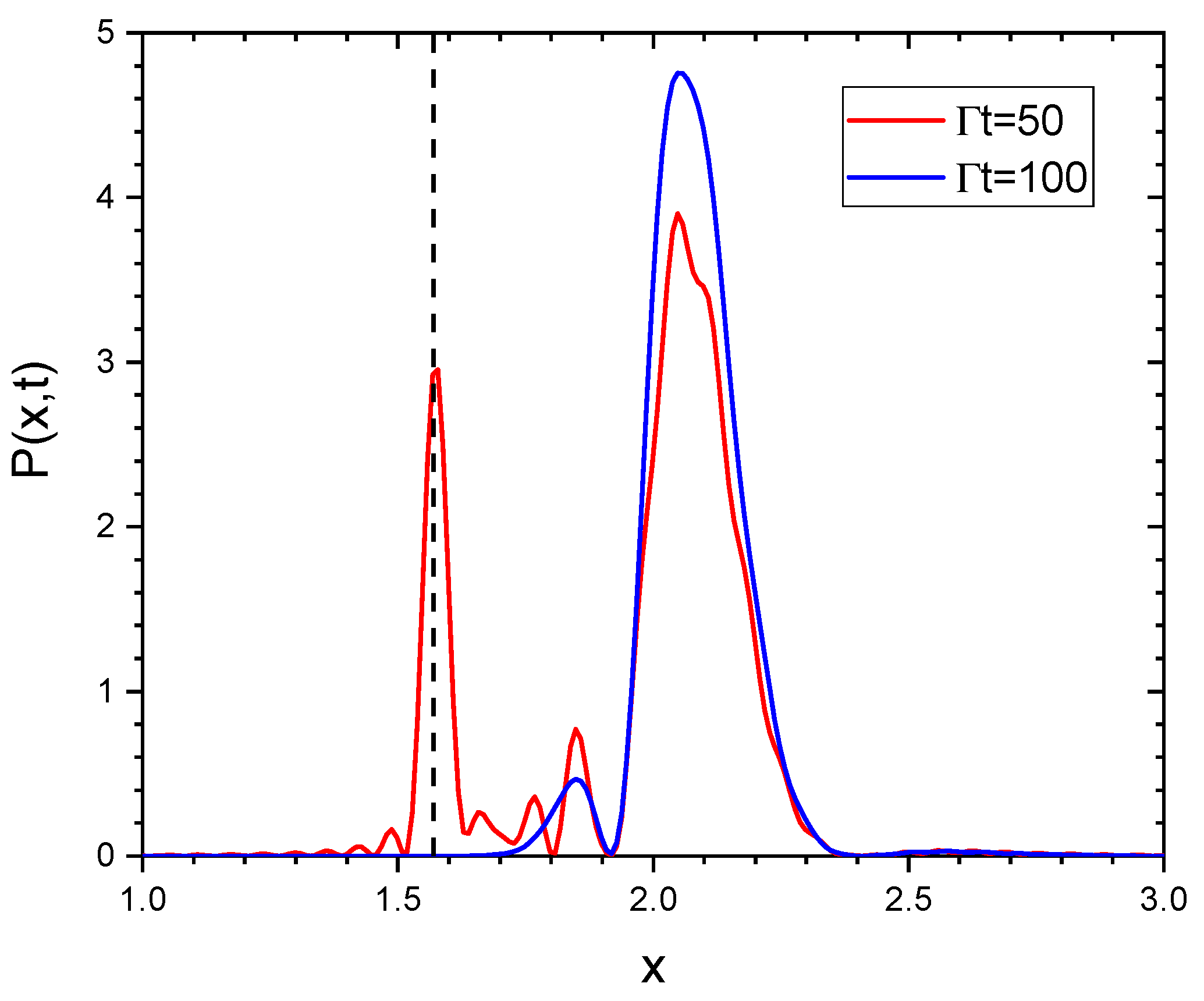

4.2. Dynamics of the probability density

5. Generation of Subradiance

5.1. Single Excited Atom

5.2. The Most Subradiant State

5.3. Atoms Driven by a Laser.

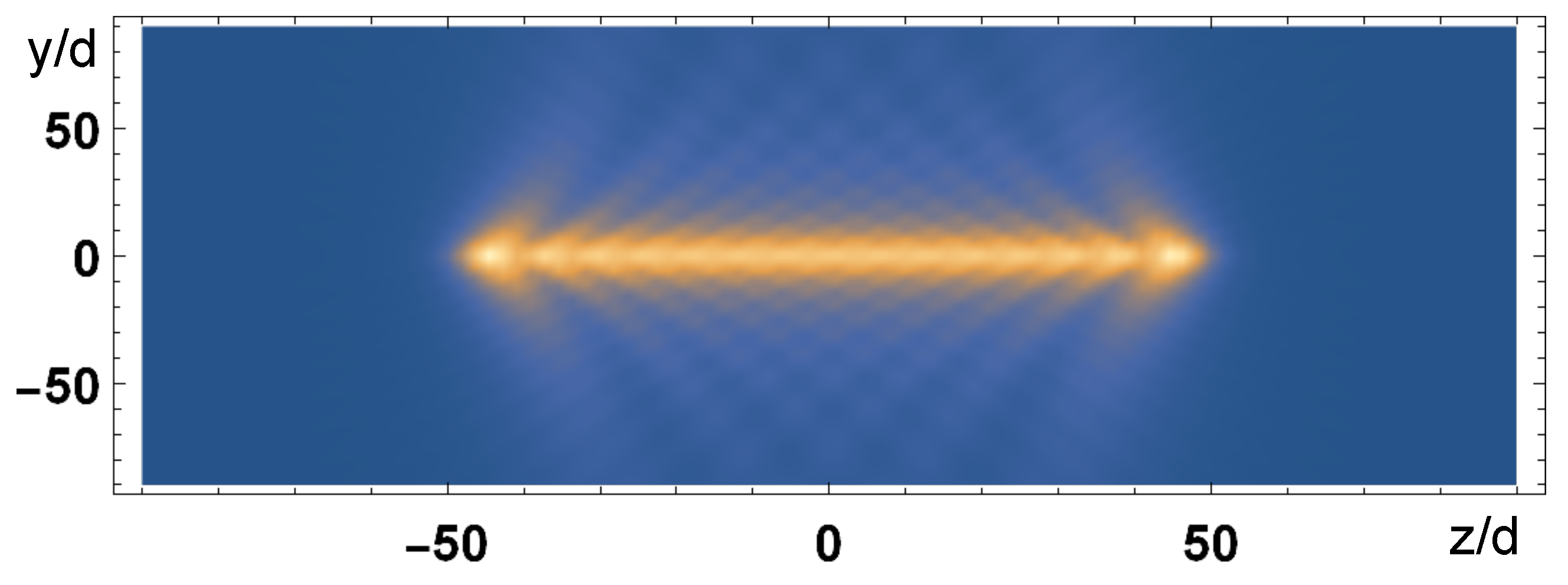

6. Radiated Intensity

7. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Equation for AN (x,t)

Appendix B. Probability Amplitude for the Subradiant State

References

- Dicke R., H. , Coherence in spontaneous radiation processes. Phys. Rev. 1954, 93, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmberg R., H. , Radiation from an N-Atom system, I. General formalism. Phys. Rev. A 1970, 2, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacio, R.; Schwendimann, P.; Haake, F. Quantum Statistical Theory of Superradiance I. Phys. Rev. A 1971, 4, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.; Haroche, S. Superradiance: An Essay on the Theory of Collective Spontaneous Emission. Phys. Rep. 1982, 93, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienaimé, T.; Piovella, N.; Kaiser, R. Controlled Dicke subradiance from a large cloud of two-level systems, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 123602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, W.; Araùjo, M.O.; Kaiser, R. Subradiance in a large cloud of cold atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 083601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Lemberger, B.; Yavuz, D.D. Subradiance and Superradiance-to-Subradiance Transition in Dilute Atomic Clouds, Phys. Rev. A 2020, 102, 043708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferioli, G.; Glicenstein, A.; Henriet, L.; Ferrier-Barbut, I.; Browaeys, A. Storage and release of subradiant excitations in a dense atomic cloud, Phys. Rev. X 2021, 11, 021031. [Google Scholar]

- Bettles, R.J.; Gardiner, S.A.; Adams, C.S. Cooperative eigenmodes and scattering in one-dimensional atomic arrays. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 043844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, G.; Jenkins, S.D.; Ruostekoski, J. Storing light with subradiant correlations in arrays of atoms. Phys.Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 243601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asenjo-Garcia, A.; Moreno-Cardoner, M.; Albrecht, A. Kimble H. J.; Chang D. E. Exponential improvement in photon storage fidelities using subradiance and “selective radiance” in atomic arrays. Phys. Rev. X 2017, 7, 031024. [Google Scholar]

- Rui, J.; Wei, D.; Rubio-Abadal, A.; Hollerith, S.; Zeiher, J.; Stamper-Kurn D., M.; Gross, C.; Bloch, I. A Subradiant Optical Mirror Formed by a Single Structured Atomic Layer. Nature 2020, 583, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, M.; Lesanovsky, I.; Olmos, B. Dispersionless subradiant photon storage in one-dimensional emitter chains. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 108, L051702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovella, N. Cooperative Decay of an Ensemble of Atoms in a One-Dimensional Chain with a Single Excitation. Atoms 2024, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellando, L.; Gero, A.; Akkermans, E.; Kaiser, R. Cooperative effects and disorder: A scaling analysis of the spectrum of the effective atomic Hamiltonian. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 90, 063822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottier, F.; Kaiser, R.; Bachelard, R. Role of disorder in super- and subradiance of cold atomic clouds. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 013622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhuis, G.; Schuller, F. Spontaneous emission and light scattering by atomic lattice models. J. Phys. B: Atom. Mol. Phys. 1987, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubi, H.; Ritsch, H. Metastability and Directional Emission Characteristics of Excitons in 1D Optical Lattices. Europhys. Lett., 2010, 90, 23001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, S.D.; Ruostekoski, J. Controlled manipulation of light by cooperative response of atoms in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 031602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettles R., J.; Gardiner S., A.; Adams, C.S. Cooperative Ordering in Lattices of Interacting Two-Level Dipoles. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 063822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, J.A.; Lesanovsky, I.; Olmos, B. Subradiance-protected excitation transport. New J. Phys. 2019, 21, 073061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, S.J.; Ferrier-Barbut, I.; Orozco, L.A.; Browaeys, A.; Asenjo-Garcia, A. Many-Body Signature of Collective Decay in Atomic Chains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 263601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, S.J.; Asenjo-Garcia, A. Universality od Dicke superradiance in arrays of quantum emitters. Nature Comm. 2022, 13, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruostekoski, J. Cooperative quantum-optical planar arrays of atoms. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 108, 030101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienaimé, T.; Bachelard, R.; Piovella, N.; Kaiser, R. Cooperativity in light scattering by cold atoms. Fortschritte der Physik 2013, 61, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, M.O.; Fry, E.; Ooi, C.H.R.; Wodkiewicz, K. Directed Spontaneous Emission from an Extended Ensemble of N Atoms: Timing Is Everything. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 010501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, M.O. Single photon subradiance: quantum control of spontaneous emission and ultrafast readout. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 243602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holstein, T. Imprisonment of Resonance Radiation in Gases. Phys. Rev. 1947, 72, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeyrie, G.; Vaujour, E.; Müller, C.; Delande, C.; Miniatura, C.; Wilkowski, D.; Kaiser, R. Slow diffusion of light in a cold atomic cloud, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 223904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).