Submitted:

19 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

- The growth of fractal crack 2

- The laws of propagation for cyclic loads 4

- Equation of the Fractal Crack (type I) 6

- Equation of the Fractal Crack (type II) 9

- Threshold-bounded formulations for propagating functions 10

- Conclusion 12

- List of symbols 13

- References 14

1. The Growth of Fractal Crack

2. The Laws of Propagation for Cyclic Loads

2.1. The subsequent section will examine the laws of propagation in relation to cyclic loads. Crack propagation will be calculated as a function of the range of the stress intensity factor:

2.2. As demonstrated in the aforementioned literature, extensive experimental evidence indicates that the S-N curves can be represented as nearly piecewise-linear graphs.This phenomenon can be explained from the perspective of crack propagation. In the initial stage, an examination of the planar crack with two distinct propagation regimes is undertaken.The growth of cracks occurs in a direction that attempts to maximize the subsequent energy release rate and minimize the strain energy density. The propagation path that optimizes this objective is aligned with the direction of maximum extension strains. Accordingly, the shape of the crack should be an ideally straight line. As the crack grows, the process of crack extension accelerates, resulting in a higher rate of elongation of the crack length per cycle, denoted as

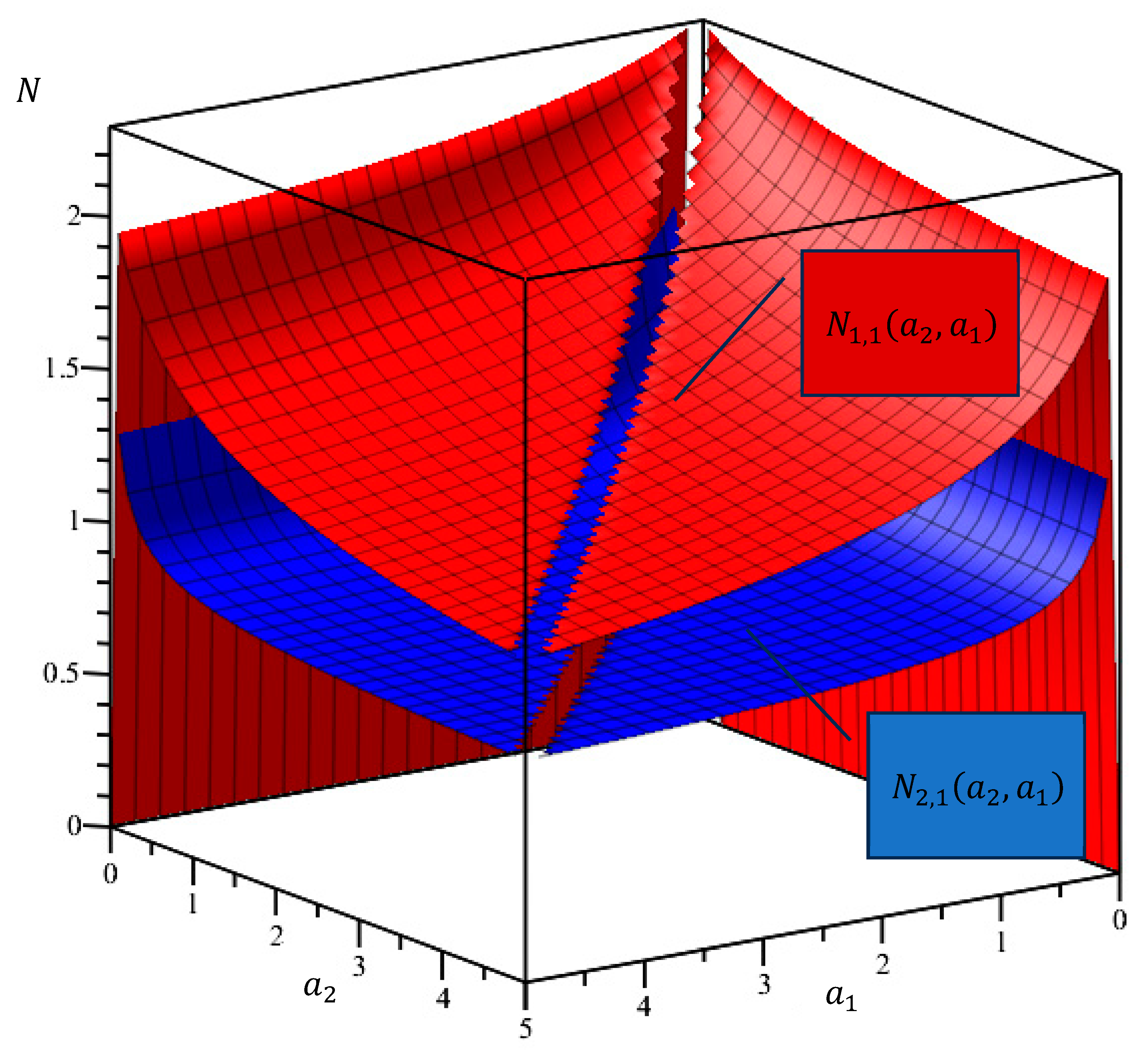

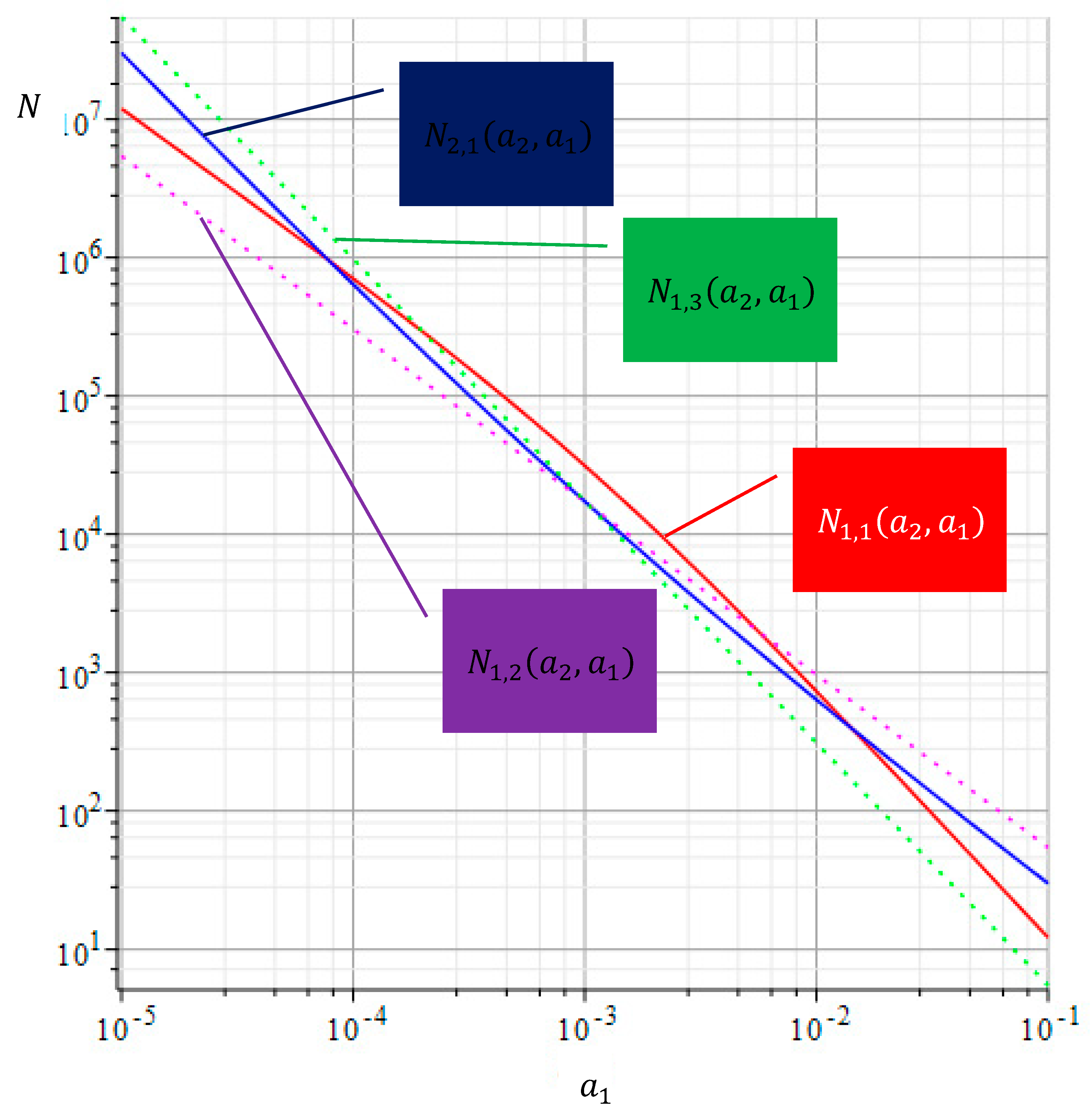

3. Equation of the Fractal Crack (Type I)

3.1. The first form of the equation, which describes how the crack propagates in the fractal medium, is as follows. This formulation assumes the application of the fractional differentiation operator

3.2. It is initially presumed that

3.3. Secondly, it is presumed that

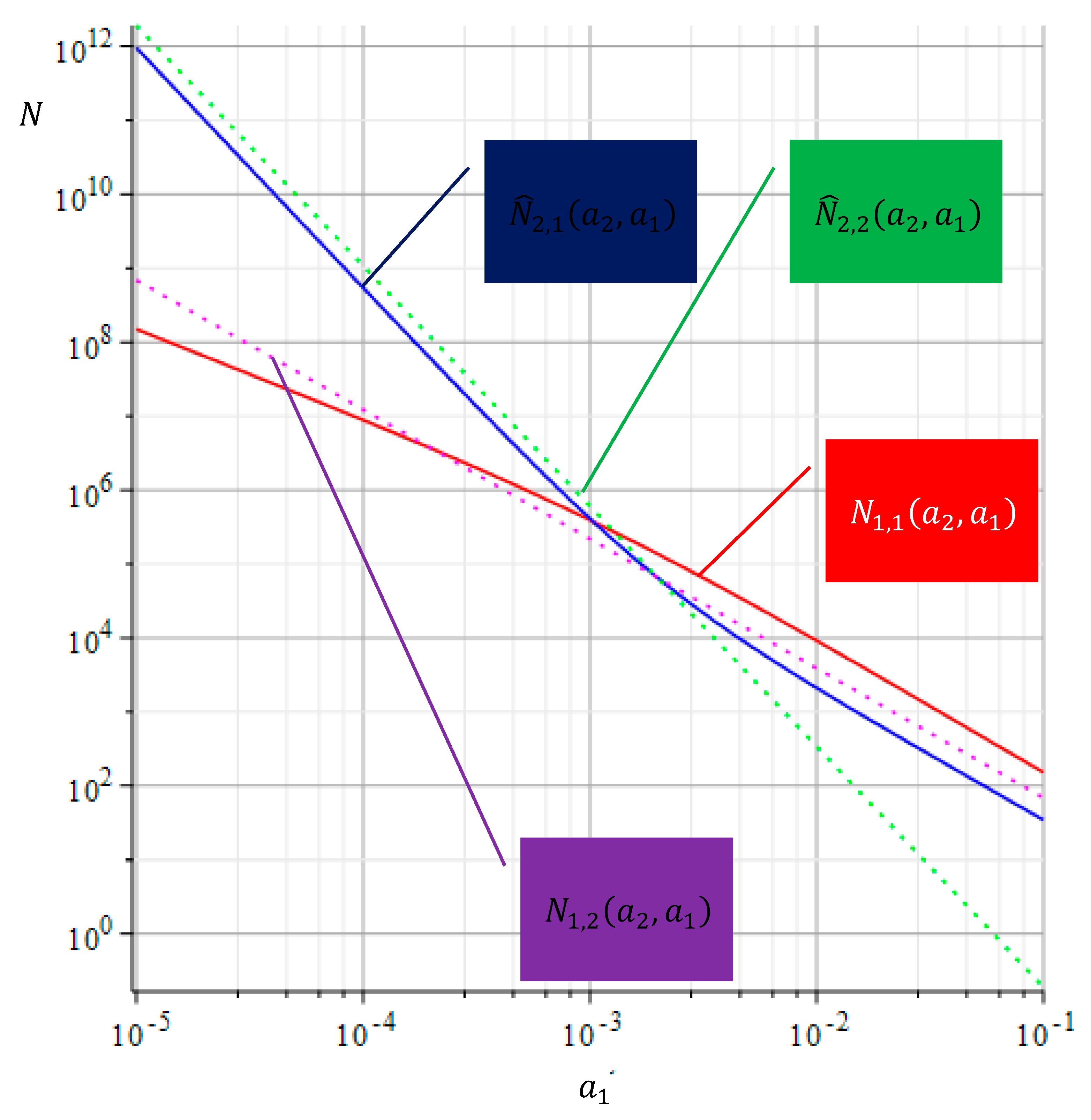

4. Equation of the Fractal Crack (Type II)

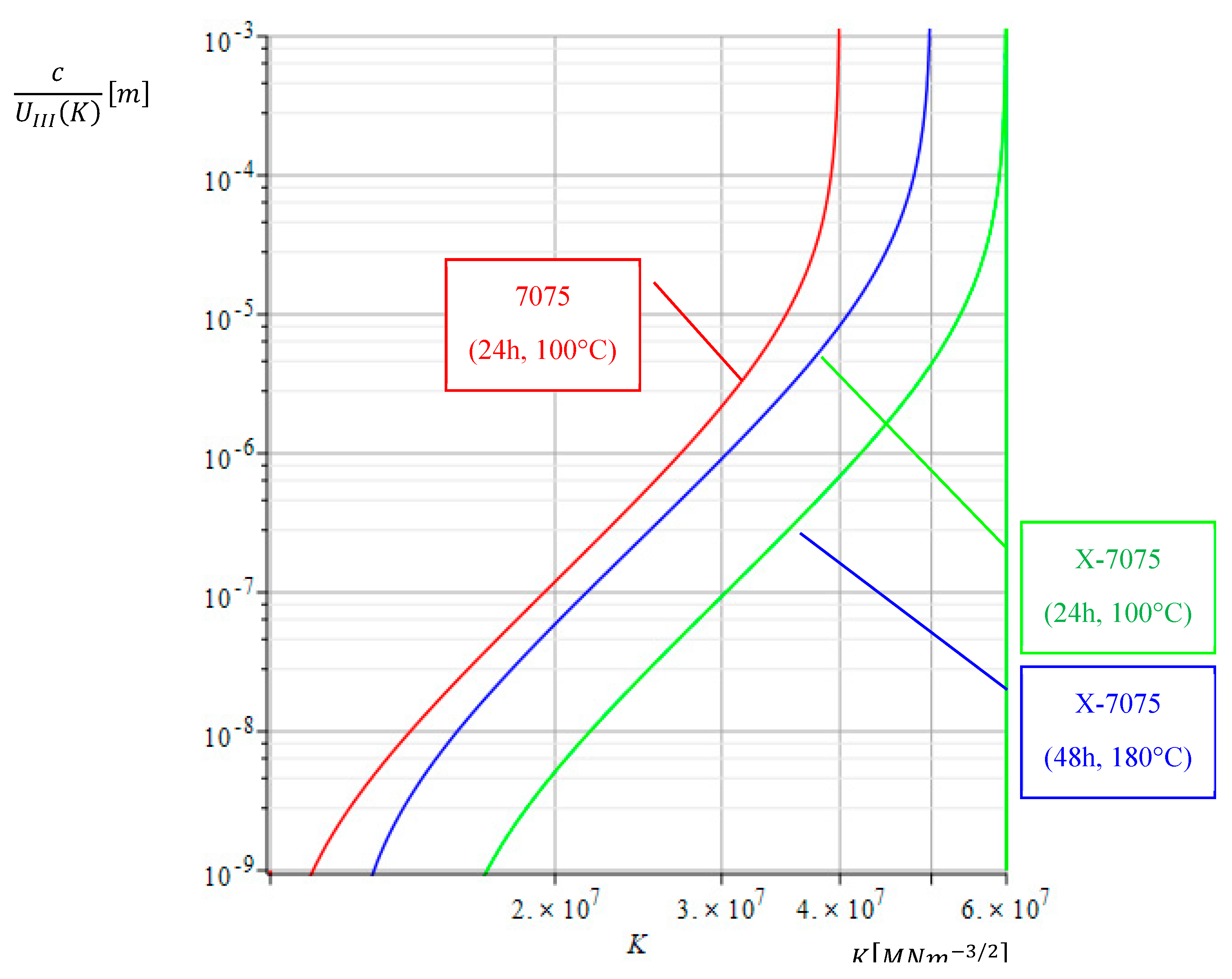

5. Threshold-Bounded Formulations for Propagating Functions

5.1. For a specific set of alloys, a theoretical value for stress amplitude exists. According to this theoretical framework, the material will not fail for any number of cycles if the stress amplitude remains below this theoretical value.

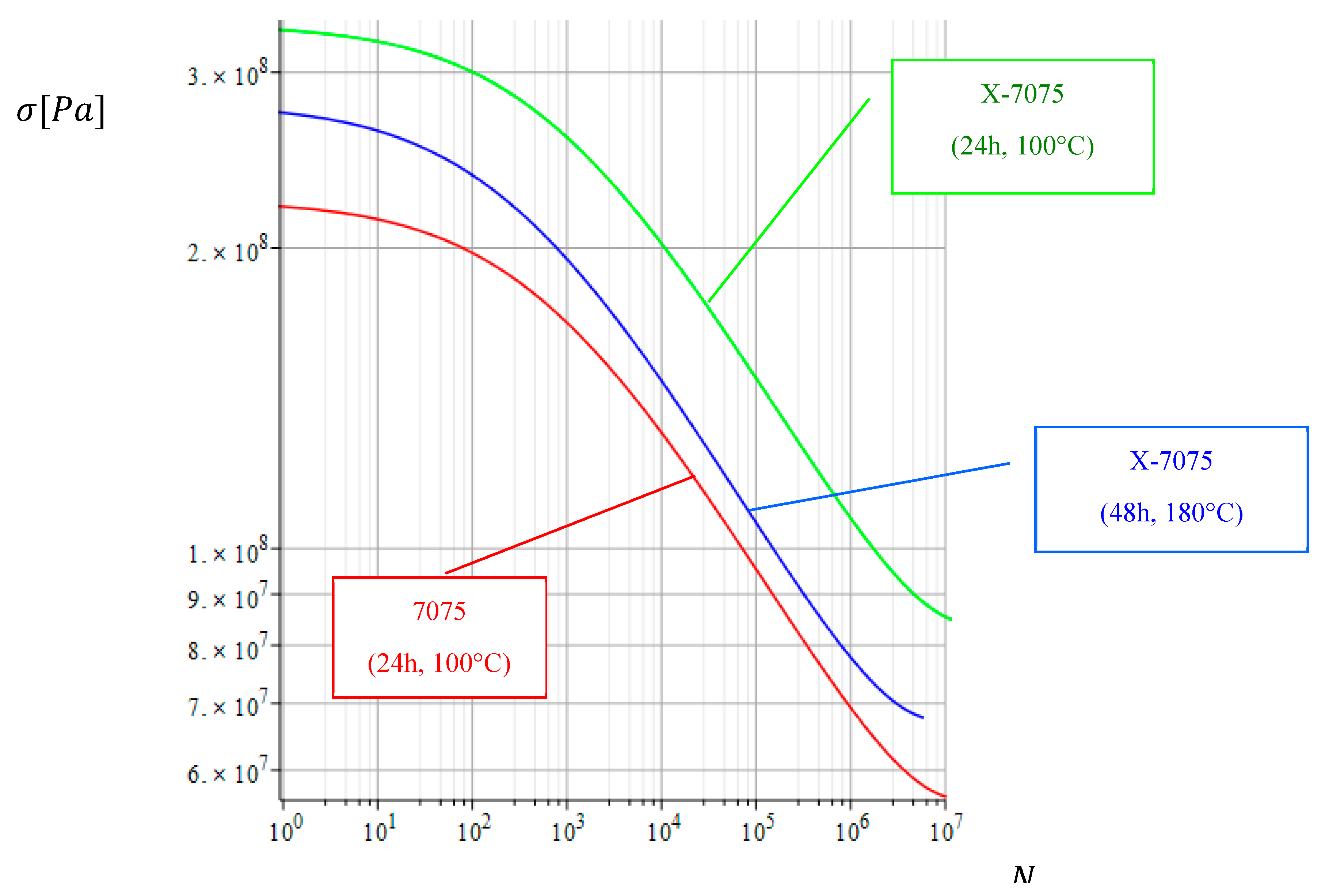

5.2. The Figure 6 shows how the crack growth rate

6. Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

List of Symbols

| maximum stress intensity factor per cycle | |

| minimum stress intensity factor per cycle | |

| range of stress intensity factor, . | |

| stress range, | |

| maximum stress per cycle | |

| minimum stress per cycle | |

| dimensionless geometry parameter | |

| material constant | |

| Auxiliary parameter | |

| stress ratio of cyclic load | |

| mean value of stress intensity factor, | |

| unified propagation function of type I, Eq. (2) | |

| unified propagation function of type II, Eq. /(17) | |

| unified propagation function of type III, Eq. (25) | |

| fatigue exponent | |

| exponent at short-term limit | |

| endurance limit exponent | |

| short-term threshold limit () | |

| endurance threshold limit () | |

| number of cycles for growth of crack length | |

| . | Lerch transcendent, §1.11, (Bateman & Erdelyi, 1953) |

| Gamma function, §1.1, (Bateman & Erdelyi, 1953) | |

References

- Abe, T.; Furuya, F.; Matsuoka, S. Giga-cycle fatigue properties for 1800 MPa-class spring steels. Transactions of the Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers Vol.67, No.664 2001, 1988–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, J.; Martin, J.; Lüthering, G.; Martin, J. Influence of micromechanisms on fatigue crack propagation rate of Al-alloys; Nancy: E.N.S.M.I.M, <i>4th Int. Conf. on the Strength of Metals and Alloys</i> (p. 1408), 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, H.; Erdelyi, A. Ch. I, The Gamma Function, 1.11. In H. Bateman, & A. Erdelyi, Higher Transcendental Functions; New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1953; pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Carpinteri, A. Handbook of Fatigue Crack Propagation in Metallic Structures; Elsevier Science B.V; Philadelphia, PA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, M.; Essex, G. C. Fractional Differential Equations and Initial Value Problems. In The Mathematical Scientist. 1998, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue, R. J.; Clark, H. M.; Atanmo, P.; Kumble, R.; McEvily, A. J. Crack opening displacement and the rate of fatigue crack growth. Int. J. Fract. Mech. 1972, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.; Yang, L. Cumulative fatigue damage and life prediction theories: A survey of the stat of the art for homogeneous materials. International Journal of Fatigue 20(1) 1998, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornbogen, E. Fractals in microstructure of metals. Int. Mat. Rev. v. 34, n. 6 1989, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanninen, M.; Popelar, C. Advanced Fracture Mechanics; Oxford University Press; New York, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kobelev, V. A proposal for unification of fatigue crack growth law. IOP Conf. Series: Journal of Physics: Conf. Series 2017, 843, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobelev, V. Forman–Kearney–Engle fractal propagation law of fatigue crack. Multidiscipline Modeling in Materials and Structures 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, J. G.; Lindley, P. B. The Mechanical Fatigue Limit for Rubber. JOURNAL OF APPLIED POLYMER SCIENCE VOL. 9 1965, 1233–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leese, G.; Socie, D. Multiaxial Fatigue, Analysis & Experiments. In SAE Pub. AE-14.; SAE; Warrendale, PA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lerch, M. Note sur la fonction. Acta Math 1887-1888, 11, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchko, Y.; Kochubei, A.; Luchko, Y. Operational method for fractional ordinary differential equations. In Handbook of Fractional Calculus with Applications; Walter de Gruyter GmbH; Berlin/Boston, 2019; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lung, C.; Pietronero, L.; Tosatti, E. Fractals and the fracture of cracked metals. In Fractals in Physics; Elsevier Science Publ, 1986; pp. 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Maierhofer, J.; Pippan, R.; Gänser, H.-P. Modified NASGRO equation for short cracks and application to the fitness-for-purpose assessment of surface-treated components. Procedia Materials Science 3() 2014, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.; Passoja, D.; Paullay, A. Fractal character of fracture surfaces of metals. Nature v. 308, N.19 1984, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvily, A.; Groeger, J. On the threshold for fatigue-crack growth. Fourth International Conference on Fracture; University of Waterloo Press; Waterloo, Canada, 1977; vol. 2, pp. 1293–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Mecholsky, J.; Passoja, D.; Feinberg-Ringel, K. Quantitative analysis of brittle fracture surfaces using fractal geometry. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. v. 72, n. 1 1989, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M. S.; Gallagher, J. P.; Hudak, S. J.; Bucci, R. J. An analysis of several fatigue crack growth rate (FCGR) descriptions. In Fatigue crack growth measurement and data analysis, ASTM STP 738; American Society for Testing and Materials, 1981; pp. 205–251. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Z.; Lung, C. Studies on the fractal dimension and fracture toughness of steel. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. v. 21 1988, 848–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughrabi, H. Specific features and mechanisms of fatigue in the ultrahigh-cycle regime. International Journal of Fatigue 28, Issue 11, November 2006, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahama, H. A fractal criterion for ductile and brittle fracture. J. Appl. Phys. v. 75, n. 6 1994, 3220–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J. A crack opening stress equation for fatigue crack growth. Int J Fract 1984, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, P.; Erdogan, F. A critical analysis of crack propagation laws. J. Basic Eng. Trans. ASME 1963, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugno, N.; Cornetti, P.; Carpinteri, A. New unified laws in fatigue: From the Wöhler’s to the Paris’ regime. Engineering Fracture Mechanics vol.74 2007, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.; Pandolfelli, V. Insights on the Fractal-Fracture Behaviour Relationship; Materials Research, 1998; Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrotzki, B.; Hornbogen, E. Fraktale Metallgefuge. Mat.-wiss. u. Wcrkstofftech. 1994, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S. Fatigue of materials; Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tada, H.; Paris, P.; Irwin, G. The stress analysis of cracks handbook, third edition; New York: American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M. Fracture toughness and crack morphology in indentation fracture of brittle materials. J. Mat. Sci. v.31 1996, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totten, G. Fatigue crack propagation. Advanced Materials & Processes 2008, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Y.; Mecholsky, J., Jr. Fractal fracture of single crystal silicon. J. Mater. Res. v. 6, n. 6 1991, 1248–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciech Macek, D. R.; Faszynka, S.; Branco, R.; Zhu, S.-P.; Nejad, R. M. Fractographic-fractal dimension correlation with crack initiation and fatigue life for notched aluminium alloys under bending load. Engineering Failure Analysis 2023, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.-B.; Hsia, K.; Lange, D. Quantitative characterization of the fracture surface of Si single crystals by confocal microscopy. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. v. 78, n. 12 1995, 3201–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).