Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theory and Design Strategy

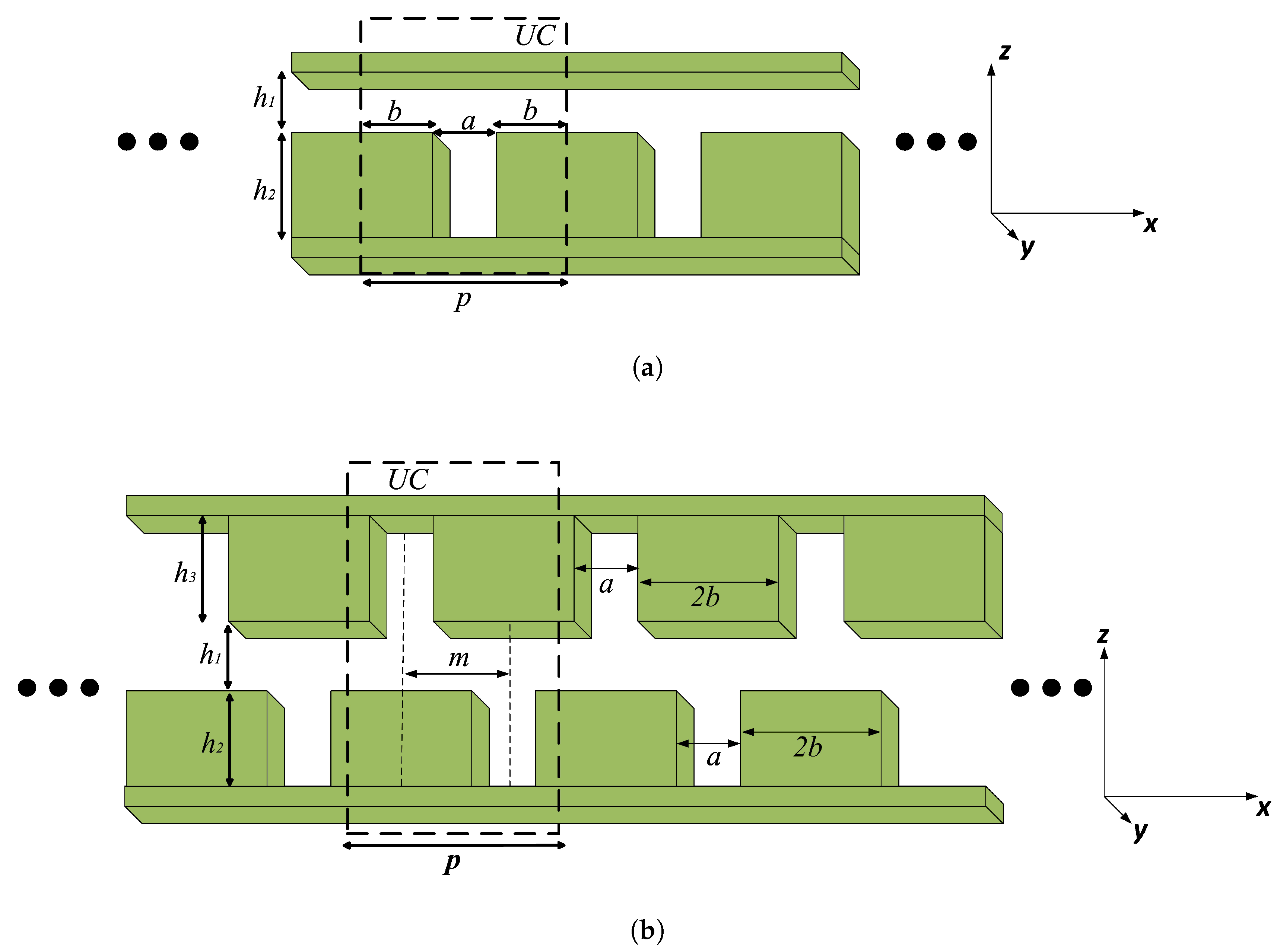

- Step 1: Select single/glide-symmetric double CPPW model and start appropriate unit cell configuration.

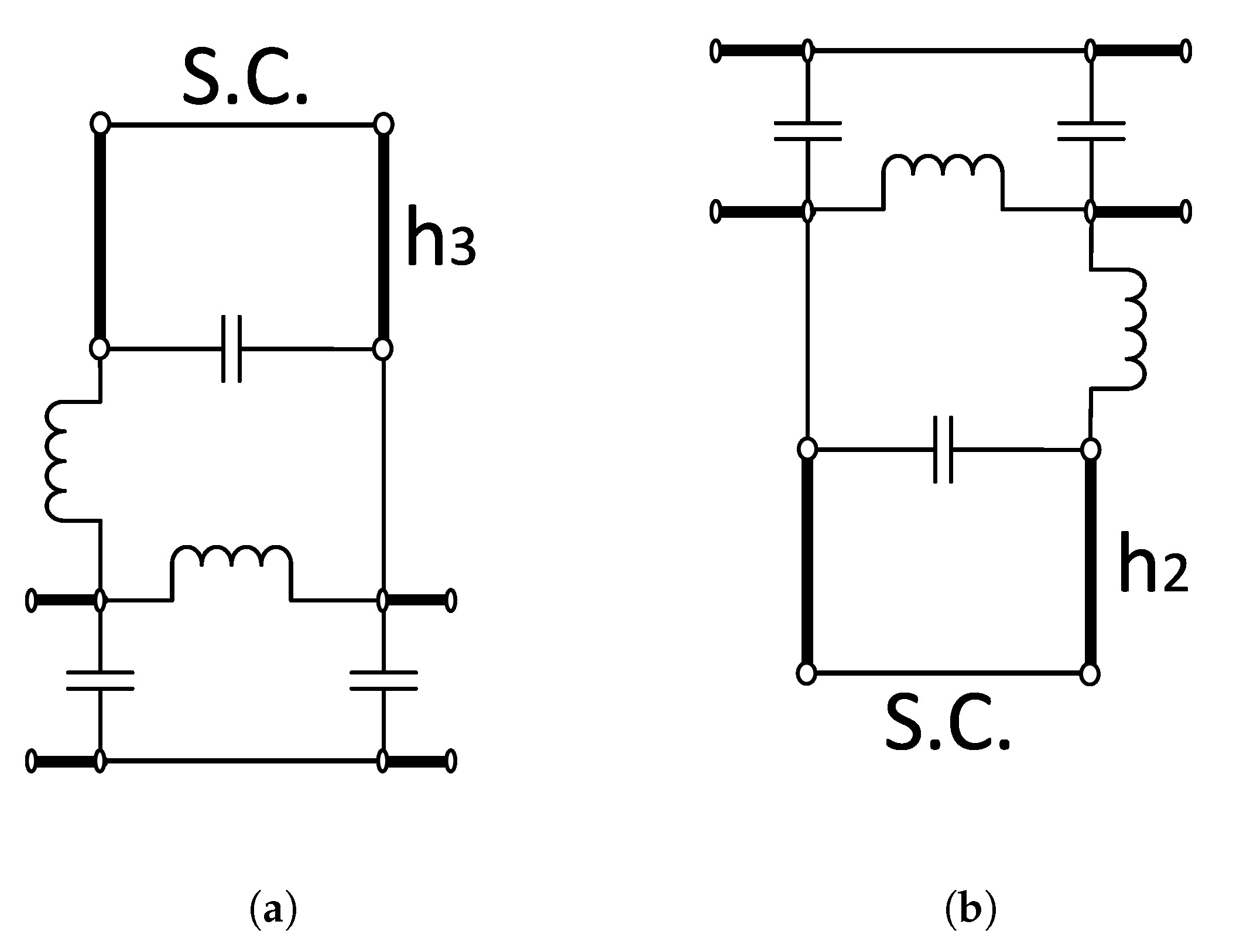

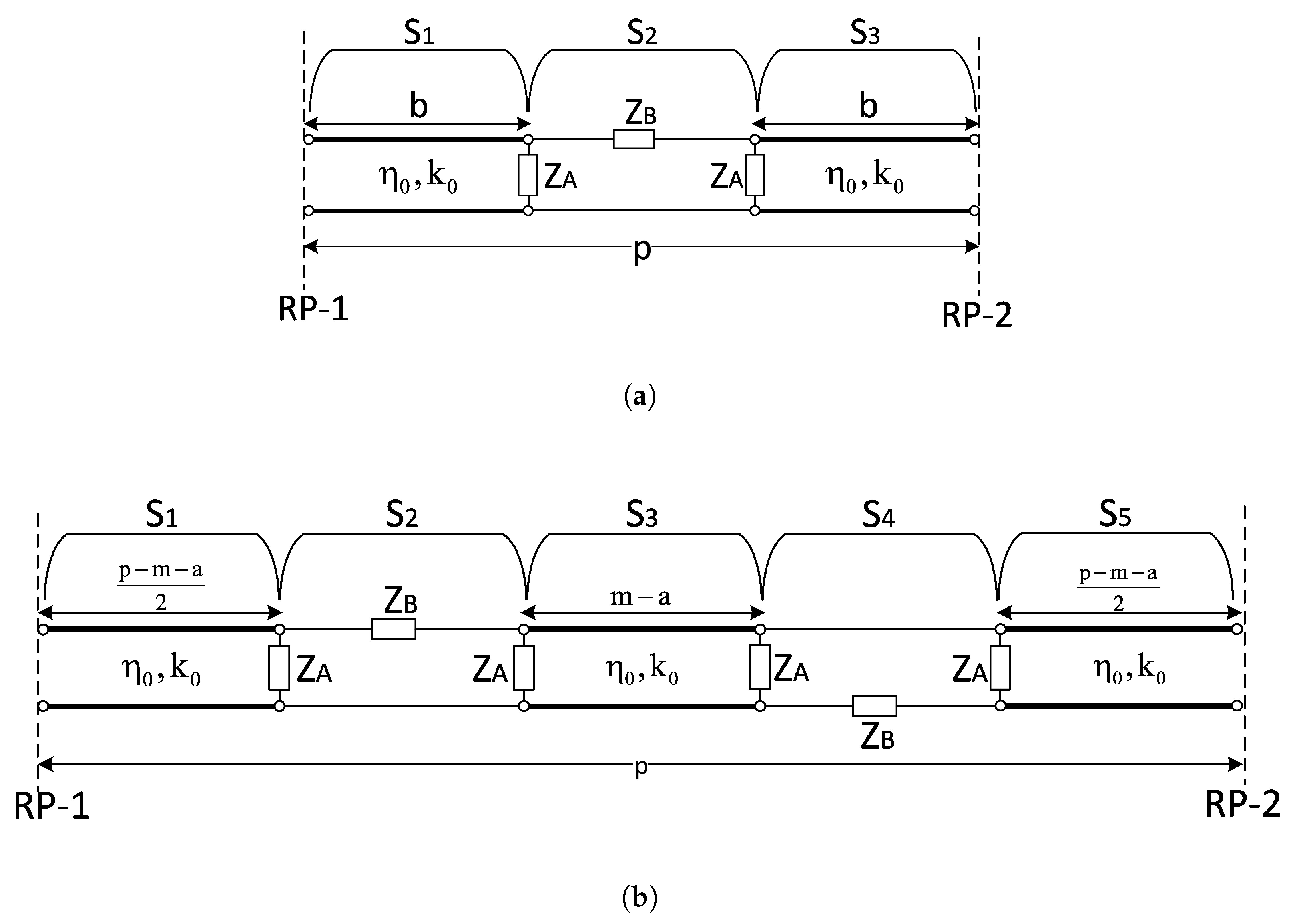

- Step 2: Constrain the design space so that the dimensional parameters of the unit cell based on the circuit model given in Figure 2 are in the appropriate range.

- Step 3: Modify the dimensions in the limited design space obtained in Step 2, and determine the appropriate unit cell parameters satisfying the given design requirements employing Equation (5).

- Step 4: Connect the designed unit cells back-to-back a finite number of times to meet the design requirements and obtain the filter responses with full-wave simulators.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Numerical Examples

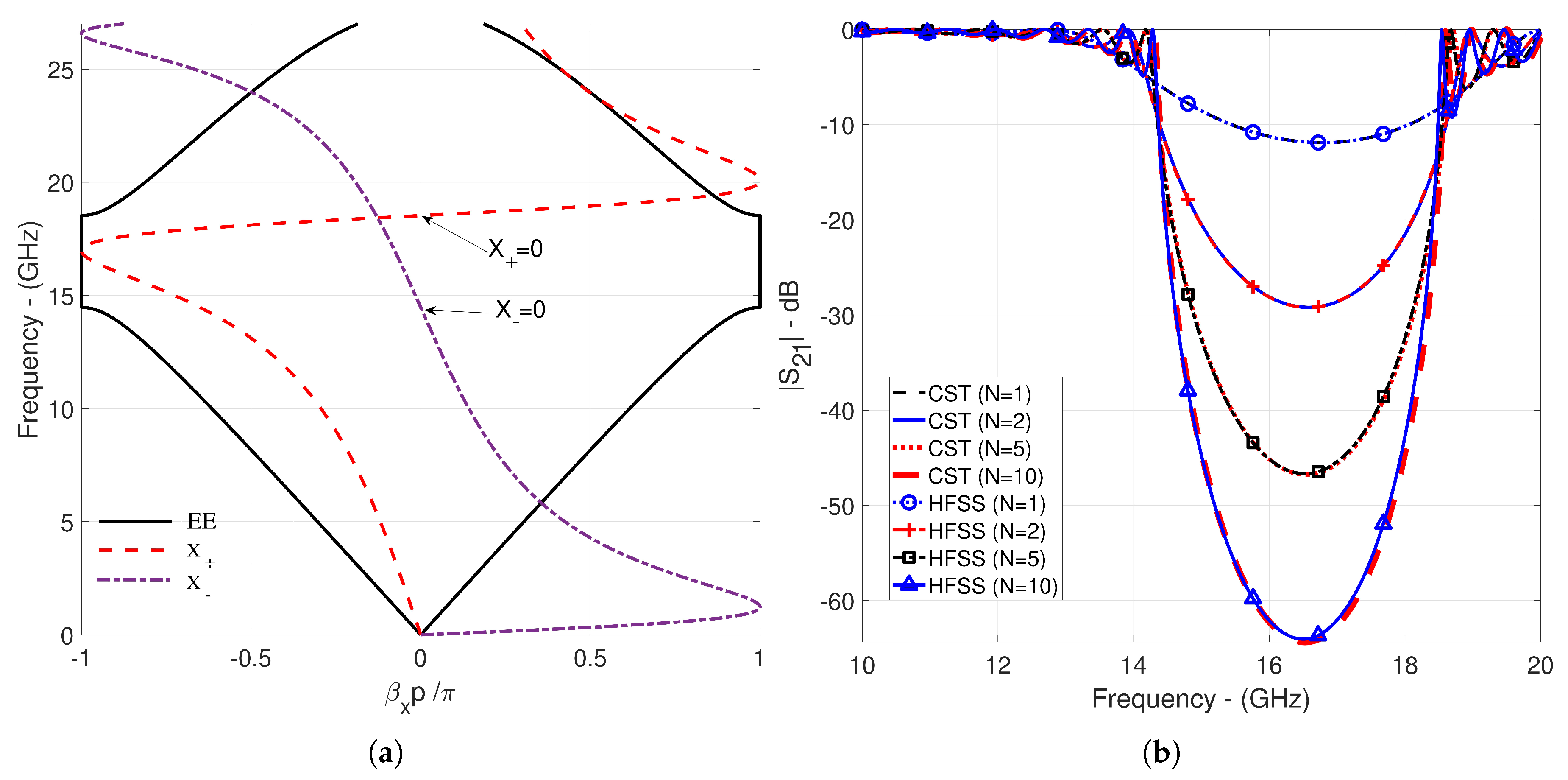

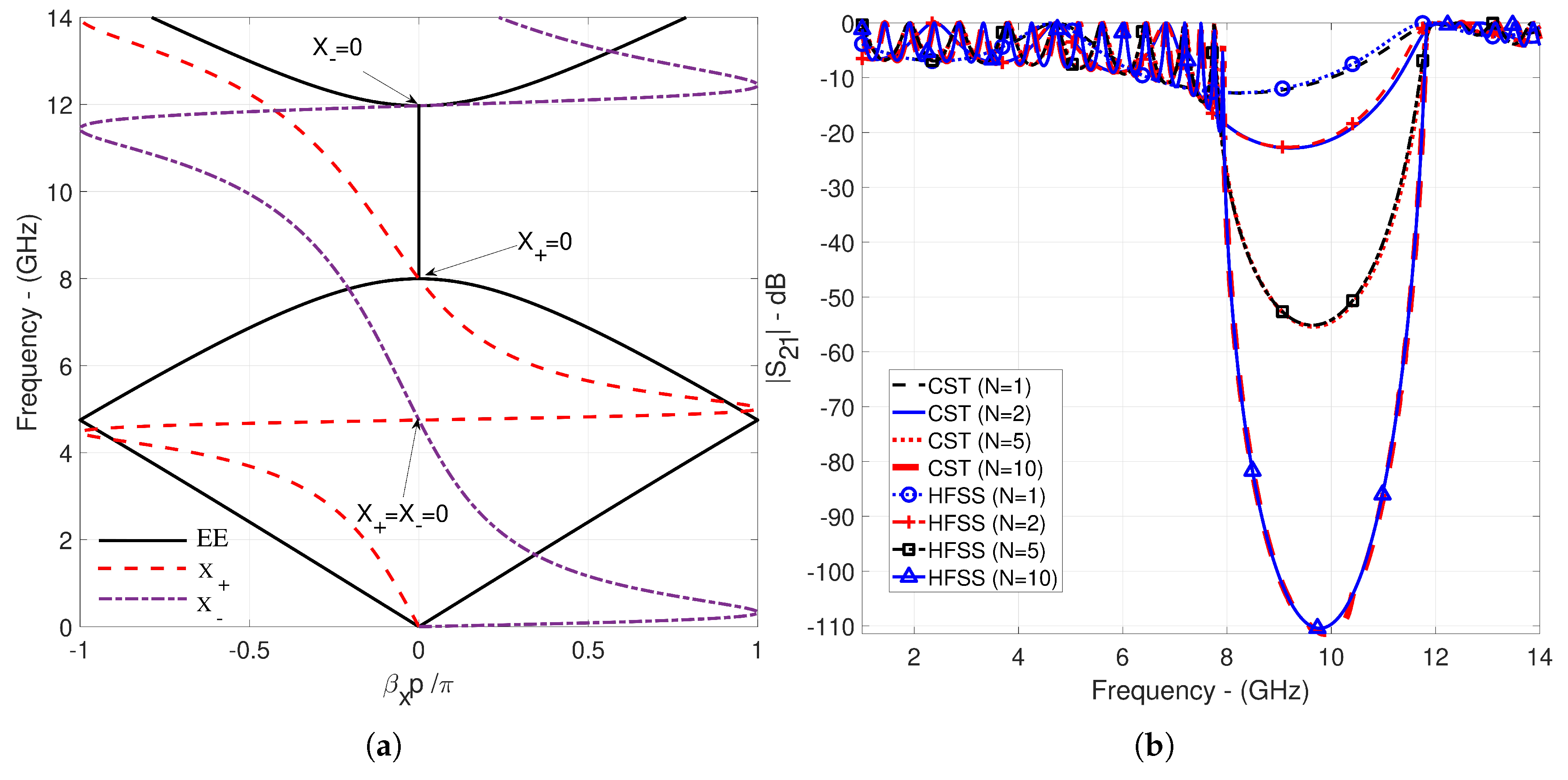

- (a)

- Ku-band filter design with a suppression level of more than -50 dB in the 15.20-17.78 GHz range for a single CPPWs.

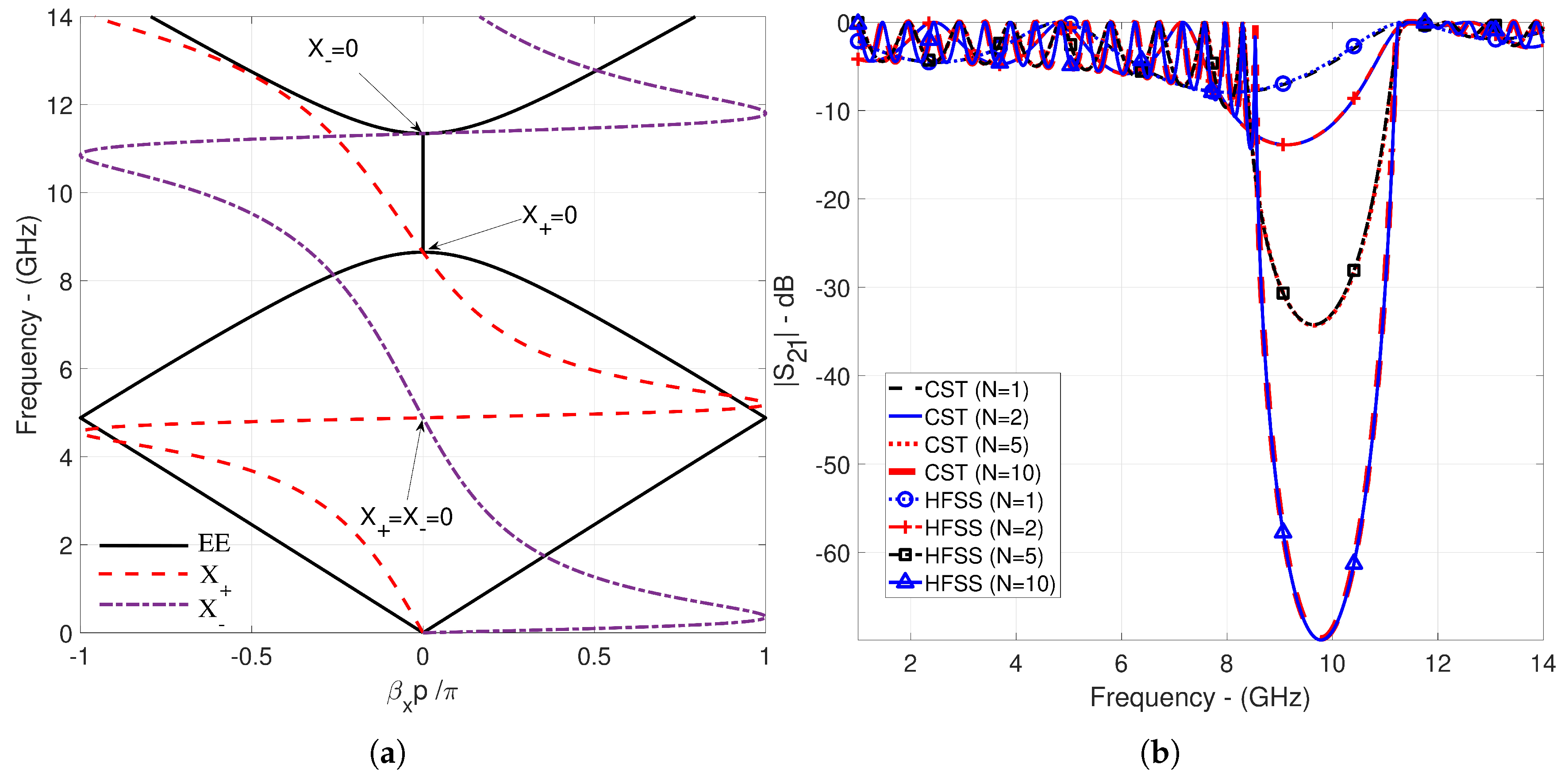

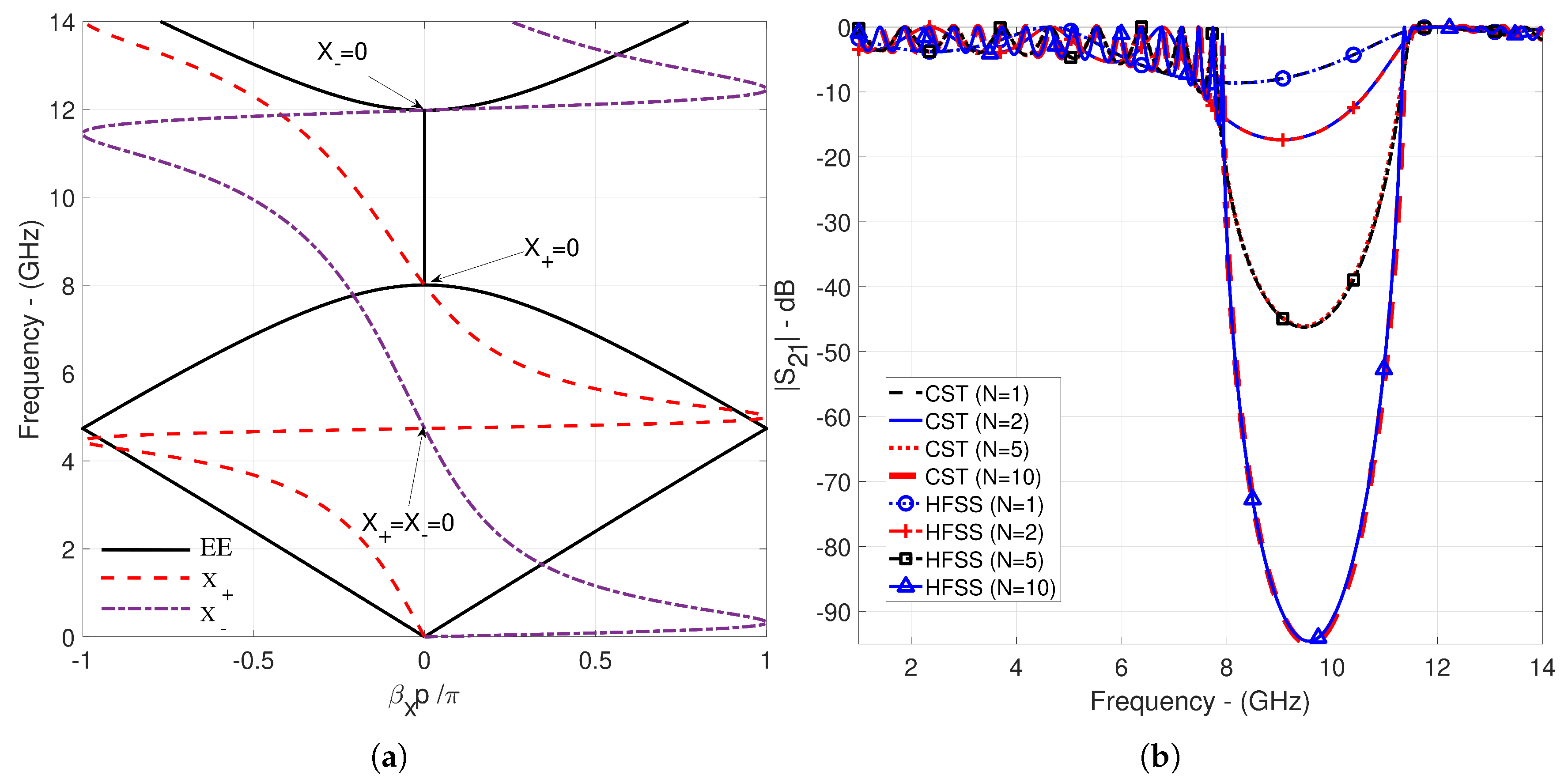

- (b)

- X-band filter design with a suppression level of more than -60 dB in the 8.27-10.91 GHz range for glide-symmetric double CPPWs.

3.2. The Design of Unit Cell and Cascade Connection Analysis Corrugated PPW Structures

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MM-GSM | Mode Matching - Generalized Scattering Matrix |

| BSF | Band Stop Filter |

| HFSS | High Frequency Structure Simulator |

| CST | Computer Simulation Technology |

Appendix A. Network Representation Explanation of Expanded Version of Equivalent Circuit of Corrugations

References

- Pozar, D.M. Microwave engineering: theory and techniques; John wiley & sons, 2021.

- Collin, R.E. Field theory of guided waves; Vol. 5, John Wiley & Sons, 1990.

- Simsek, S.; Topuz, E. Some properties of generalized scattering matrix representations for metallic waveguides with periodic dielectric loading. IEEE transactions on microwave theory and techniques 2007, 11, 2336–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertay, A.O.; Simsek, S. Detection of band edge frequencies in symmetric/asymmetric dielectric loaded helix slow-wave structures. International Journal of Circuit Theory and Applications 2022, 50, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, G.; Hassan, A.; Ali, S.; Bermak, A. Unit Cell Optimization of Groove Gap Waveguide for High Bandwidth Microwave Applications. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 10891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, S.; Topuz, E.; Niver, E. A novel design method for electromagnetic bandgap based waveguide filters with periodic dielectric loading. AEU-International Journal of Electronics and Communications 2012, 66, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coves, A.; San-Blas, A.A.; Bronchalo, E. Analysis of the dispersion characteristics in periodic Substrate Integrated Waveguides. AEU-International Journal of Electronics and Communications 2021, 139, 153914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, F.; Rodríguez-Berral, R.; Medina, F. On the computation of the dispersion diagram of symmetric one-dimensionally periodic structures. Symmetry 2018, 10, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertay, A.O.; Şimşek, S. A comprehensive auxiliary functions of generalized scattering matrix (AFGSM) method to determine bandgap characteristics of periodic structures. AEU-International Journal of Electronics and Communications 2018, 94, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Lv, X. Compact fully metallic millimeter-wave waveguide-fed periodic leaky-wave antenna based on corrugated parallel-plate waveguides. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters 2020, 19, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex-Amor, A.; Mesa, F.; Palomares-Caballero, Á.; Molero, C.; Padilla, P. Exploring the potential of the multi-modal equivalent circuit approach for stacks of 2-D aperture arrays. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2021, 69, 6453–6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wu, J.; Chen, X. Design of Broadband Highly Efficient Power Amplifier Based on Low-Pass Filtering Network With Periodic Structure. International Journal of Circuit Theory and Applications 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamirad, M.; Pouyanfar, N.; Alibakhshikenari, M.; Ghobadi, C.; Nourinia, J.; See, C.H.; Falcone, F. Low-loss and dual-band filter inspired by glide symmetry principle over millimeter-wave spectrum for 5G cellular networks. Iscience 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maci, S.; Minatti, G.; Casaletti, M.; Bosiljevac, M. Metasurfing: Addressing waves on impenetrable metasurfaces. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters 2011, 10, 1499–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo-Teruel, O.; Valerio, G.; Sipus, Z.; Rajo-Iglesias, E. Periodic structures with higher symmetries: Their applications in electromagnetic devices. IEEE Microwave Magazine 2020, 21, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares-Caballero, Á.; Alex-Amor, A.; Padilla, P.; Valenzuela-Valdés, J.F. Dispersion and filtering properties of rectangular waveguides loaded with holey structures. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2020, 68, 5132–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo-Teruel, O.; Chen, Q.; Mesa, F.; Fonseca, N.J.; Valerio, G. On the benefits of glide symmetries for microwave devices. IEEE Journal of Microwaves 2021, 1, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemifard, F.; Norgren, M.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. Twist and polar glide symmetries: an additional degree of freedom to control the propagation characteristics of periodic structures. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, O.; Mitchell-Thomas, R.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. Reducing the dispersion of periodic structures with twist and polar glide symmetries. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 10136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberg, P.; Barreira Petersson, O.; Zetterstrom, O.; Ghasemifard, F.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. High refractive index electromagnetic devices in printed technology based on glide-symmetric periodic structures. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, A.; Chen, M.H.; Li, R.C.; Oliner, A.A. Propagation in periodically loaded waveguides with higher symmetries. Proceedings of the IEEE 1973, 61, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimpouri, M.; Quevedo-Teruel, O.; Rajo-Iglesias, E. Design guidelines for gap waveguide technology based on glide-symmetric holey structures. IEEE microwave and wireless components letters 2017, 27, 542–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo-Dominguez, A.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, J.M.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. One-plane glide-symmetric holey structures for stop-band and refraction index reconfiguration. Symmetry 2019, 11, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo-Teruel, O.; Ebrahimpouri, M.; Kehn, M.N.M. Ultrawideband metasurface lenses based on off-shifted opposite layers. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters 2015, 15, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemifard, F.; Norgren, M.; Quevedo-Teruel, O.; Valerio, G. Analyzing glide-symmetric holey metasurfaces using a generalized Floquet theorem. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 71743–71750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herran, L.F.; Chen, Q.; Mesa, F.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. Electromagnetic Bandgap Based on a Compact Three-Hole Double-Layer Periodic Structure. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemifard, F.; Norgren, M.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. Dispersion analysis of 2-D glide-symmetric corrugated metasurfaces using mode-matching technique. IEEE Microwave and Wireless Components Letters 2017, 28, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, G.; Ghasemifard, F.; Sipus, Z.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. Glide-symmetric all-metal holey metasurfaces for low-dispersive artificial materials: Modeling and properties. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2018, 66, 3210–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, B.; Valerio, G. Dispersion properties of glide-symmetric corrugated metasurface waveguides. International Journal of Microwave and Wireless Technologies 2024, 16, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memeletzoglou, N.; Sanchez-Cabello, C.; Pizarro-Torres, F.; Rajo-Iglesias, E. Analysis of periodic structures made of pins inside a parallel plate waveguide. Symmetry 2019, 11, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Mesa, F.; Yin, X.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. Accurate characterization and design guidelines of glide-symmetric holey EBG. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2020, 68, 4984–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, G.; Sipus, Z.; Grbic, A.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. Accurate equivalent-circuit descriptions of thin glide-symmetric corrugated metasurfaces. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2017, 65, 2695–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertay, A.O. Modeling, Analysis, and Comparison of Rectangular Waveguide Structures Having Glide Symmetrical Step Discontinuity with Periodic Dielectric Loading. Erzincan University Journal of Science and Technology 2024, 17, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, B.; Valerio, G. Quasi-static homogenization of glide-symmetric holey parallel-plate waveguides with ultra-wideband validity. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2022, 70, 10569–10582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.Y.; Kehn, M.N.M. Analysis of Rotated Corrugated Parallel Plate Waveguide Using Asymptotic Corrugation Boundary Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation and USNC-URSI Radio Science Meeting. IEEE; 2019; pp. 837–838. [Google Scholar]

- Mesa, F.; Valerio, G.; Rodriguez-Berral, R.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. Simulation-assisted efficient computation of the dispersion diagram of periodic structures: A comprehensive overview with applications to filters, leaky-wave antennas and metasurfaces. IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine 2020, 63, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Tapia, P.; Mesa, F.; Yakovlev, A.; Valerio, G.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. Study of forward and backward modes in double-sided dielectric-filled corrugated waveguides. Sensors 2021, 21, 6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Tapia, P.; Mesa, F.; Quevedo-Teruel, O. Multimodal Transfer Matrix Approach for the Analysis and Fundamental Understanding of Periodic Structures with Higher Symmetries. In Proceedings of the 2022 16th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Tapia, P. The Multimodal Transfer Matrix Method: And its application to higher-symmetric periodic structures. PhD thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 2022.

- Lech, R.; Mazur, J. Propagation in rectangular waveguides periodically loaded with cylindrical posts. IEEE microwave and wireless components letters 2004, 14, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, S. A fast and accurate design method for broad omnidirectional bandgaps of one dimensional photonic crystals. AEU-International Journal of Electronics and Communications 2014, 68, 865–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertay, A.O.; Şimşek, S. Determination of stopband characteristics of asymmetrically loaded helix slow wave structures with Auxiliary Functions of Generalized Scattering Matrix (AFGSM) method. AEU-International Journal of Electronics and Communications 2018, 95, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuvitz, N. Waveguide handbook; P. Peregrinus on behalf of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, 1986.

- Şimşek, S.; Rezaeieh, S.A. A design method for substrate integrated waveguide electromagnetic bandgap (SIW-EBG) filters. AEU-International Journal of Electronics and Communications 2013, 67, 981–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Mao, J. Miniaturized tapered EBG structure with wide stopband and flat passband. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters 2012, 11, 314–317. [Google Scholar]

- Ertay, A.O.; Şimşek, S. A compact bandstop filter design for X-band applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Symposium on Fundamentals of Electrical Engineering (ISFEE). IEEE; 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, F.; Li, L.; Shen, Y.; Sun, C.; Luan, H.; Hu, S. Wideband switchable sharp-rejection filter in compact 3-D heterogeneous integration. IEEE Transactions on Components, Packaging and Manufacturing Technology 2022, 12, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reines, I.; Park, S.J.; Rebeiz, G.M. Compact low-loss tunable X-band bandstop filter with miniature RF-MEMS switches. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2010, 58, 1887–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Papapolymerou, J. Monolithic reconfigurable bandstop filter using RF MEMS switches. International Journal of RF and Microwave Computer-Aided Engineering: Co-sponsored by the Center for Advanced Manufacturing and Packaging of Microwave, Optical, and Digital Electronics (CAMPmode) at the University of Colorado at Boulder 2004, 14, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

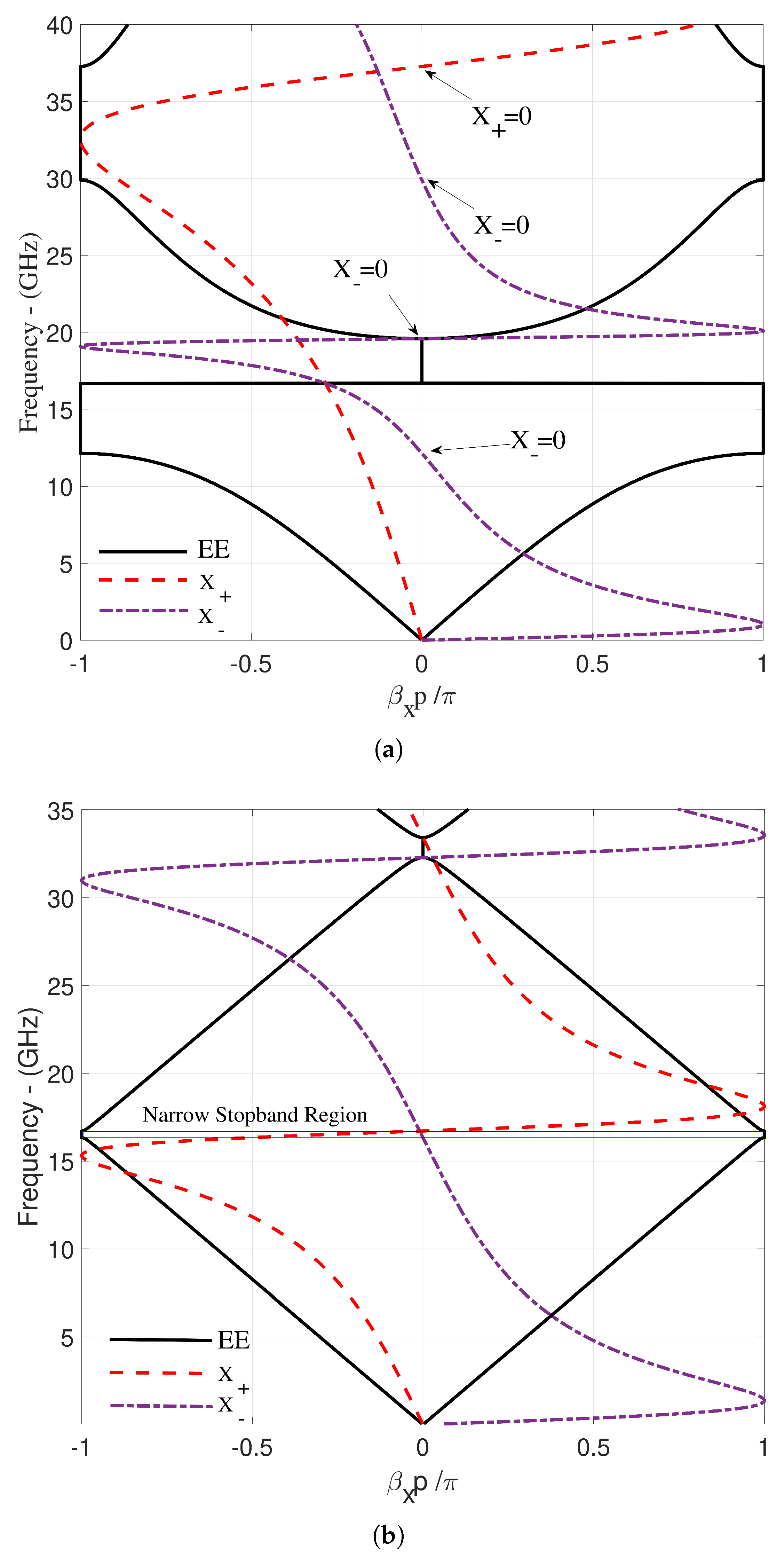

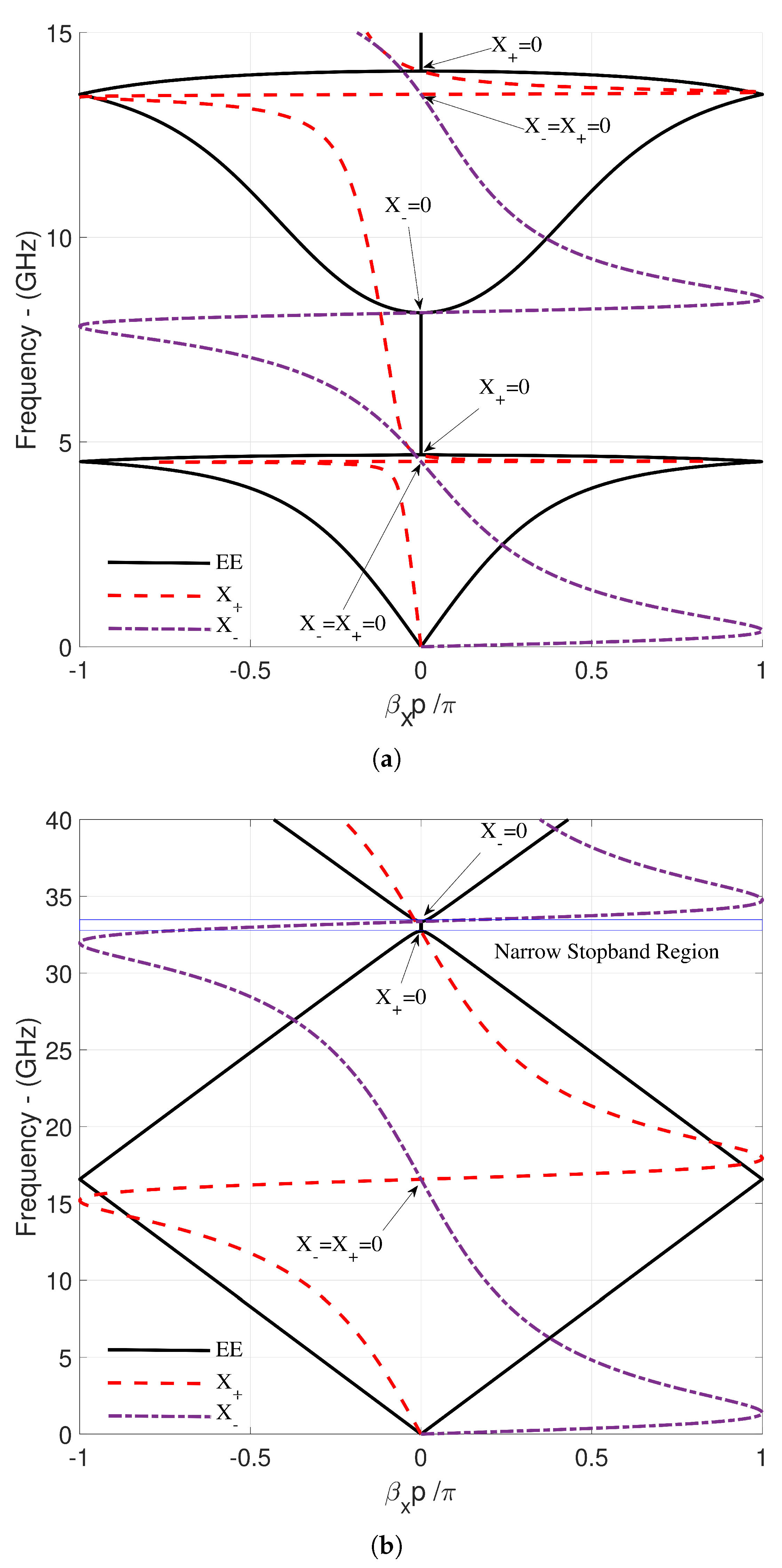

| Figures | EE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [GHz] | [GHz] | [GHz] | [GHz] | |

| Figure 4a | 4.681 | 8.157 | 4.69-8.15 | 4.52, 13.49 |

| Figure 4b | 32.729 | 33.364 | 32.73-33.363 | 16.57 |

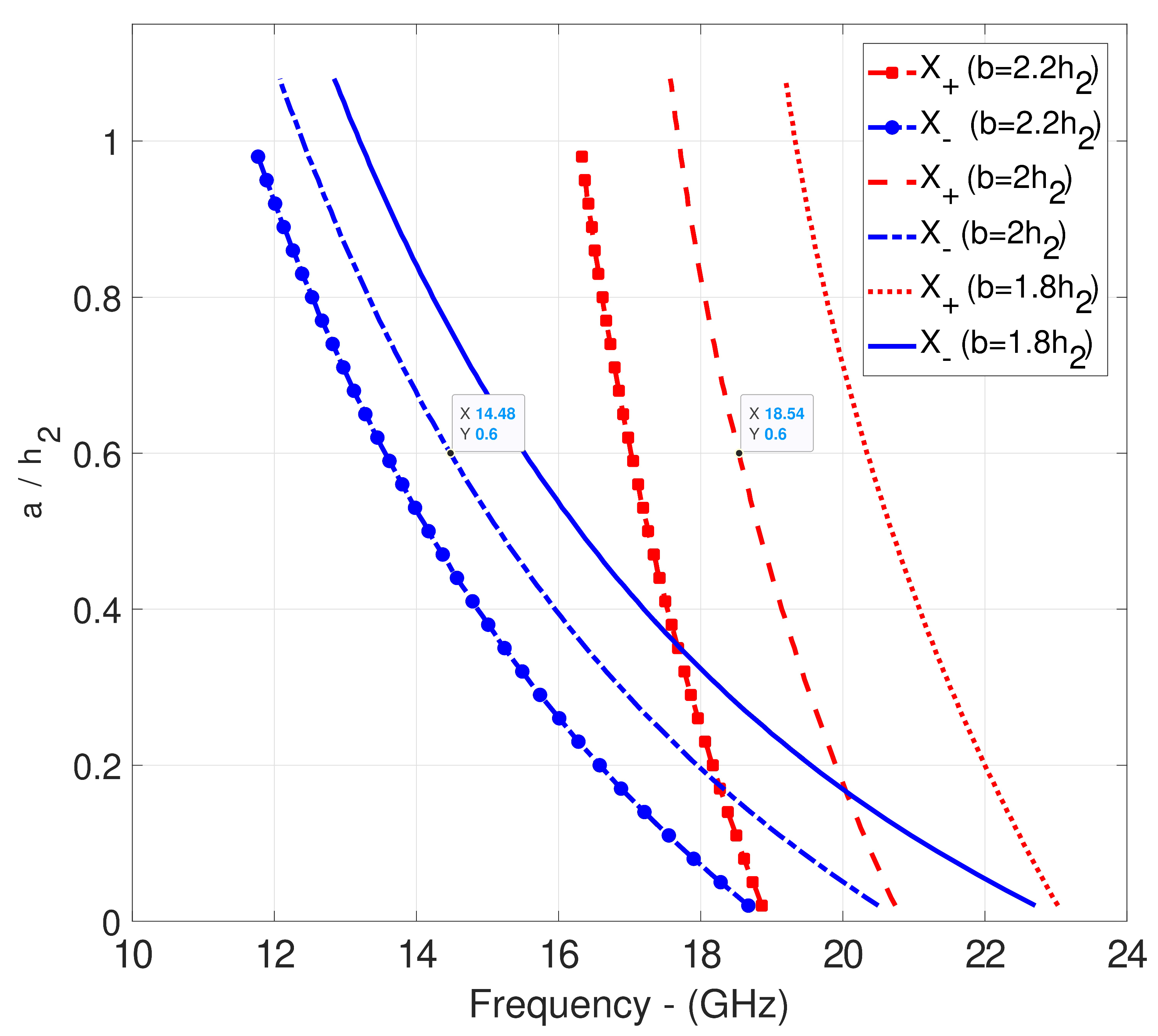

| a | b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [GHz] | [MHz] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] |

| 1.8 | 30 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 13.6 |

| 2 | 10 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 13.5 |

| 2.7 | 10 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 13.2 |

| 1.7 | 1 | 13.3 | ||

| 3 | 10 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 12.9 |

| 3.2 | 10 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 12.9 |

| 3.6 | 10 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 12.8 |

| 2.1 | 1.1 | 13.1 | ||

| 3.8 | 10 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 12.5 |

| 1.7 | 1.6 | 12.7 | ||

| 2.2 | 1.1 | 13.1 | ||

| 4 | 20 | 1.5 | 2 | 12.5 |

| 1.9 | 1.5 | 12.7 | ||

| 2 | 1.4 | 12.8 | ||

| 2.1 | 1.3 | 12.9 | ||

| 2.2 | 1.2 | 13 | ||

| 2.3 | 1.1 | 13.1 | ||

| 4.4 | 10 | 2 | 1.6 | 12.6 |

| 10 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 13 | |

| 4.8 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 12.8 |

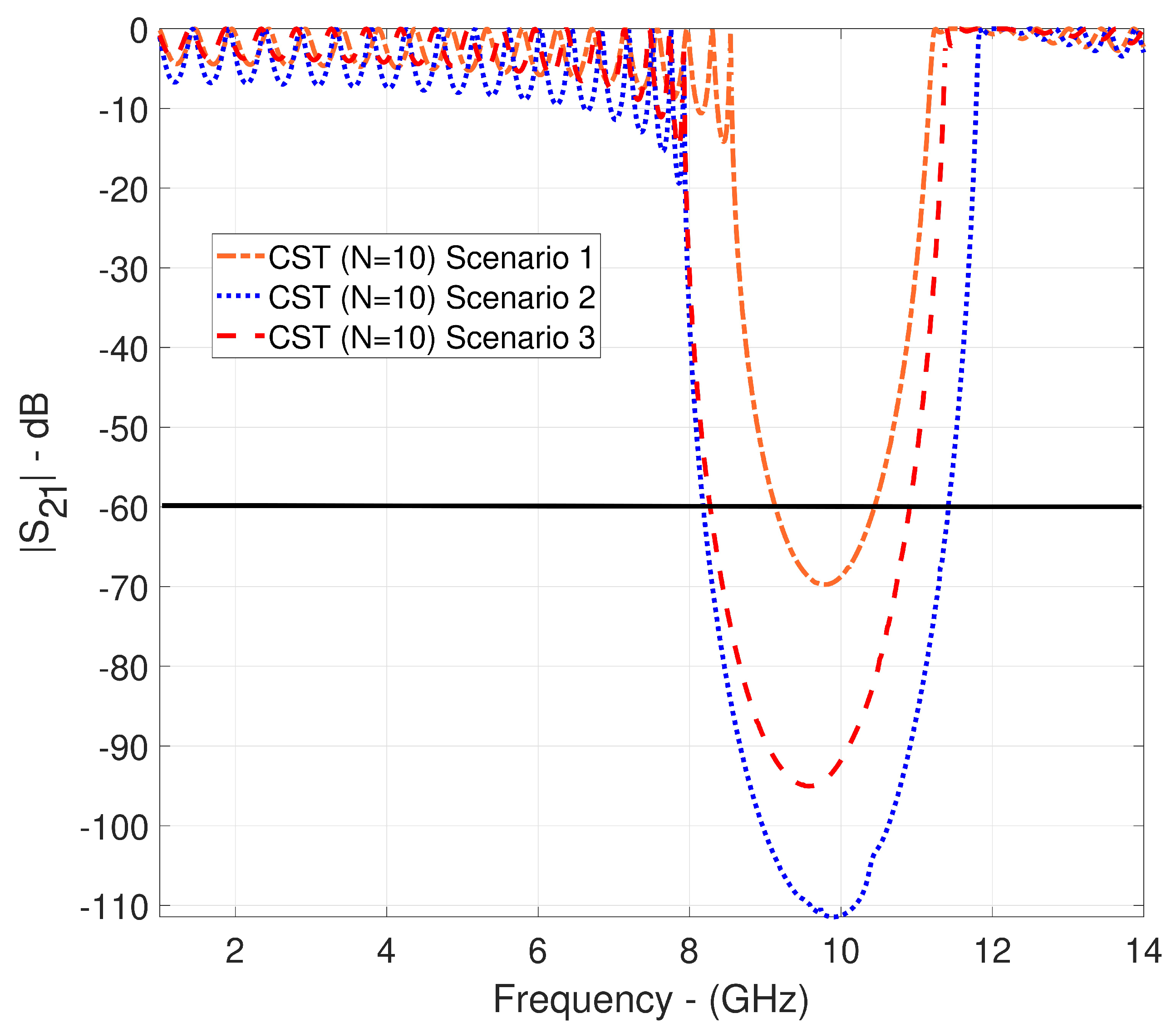

| Studies | a | b | p | TFD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | |

| Scenario 1 | 1.5 | 13.2 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 27.9 | 2.9 | 279 |

| Scenario 2 | 1.5 | 12.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 26.5 | 4.5 | 265 |

| Scenario 3 | 2.3 | 13.1 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 28.5 | 2.7 | 285 |

| Works | Physical Dimensions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| [GHz] | [GHz] | [mm × mm × mm] | |

| [3], Figure 10, MM-GSM | 9, Waveguide | @-60 dB, 0.1 | 1120.14 × 22.86 × 10.16 |

| [46], Figure 6, SONNET | 9.7, Microstrip | @ -60 dB, 1 | 12.87 × 7.04 × 0.27 |

| [47], Figure 9, Conv. BSF | 9.3, Waveguide | @ -60 dB, 1.23 | 86 × 74 × 18 |

| [47], Figure 9, Prop. BSF | 9.35, Hybrid | @ -55.5 dB, 2.67 | 15 × 8 × 1 |

| [48], Figure 10a, State (01) | 10.3, Microstrip | @ -20 dB, 0.215 | 7.3 × 7.5 × 0.508 |

| [48], Figure 10a, State (10) | 10.2, Microstrip | @ -20 dB, 0.22 | 7.3 × 7.5 × 0.508 |

| [48], Figure 14a, =25V | 9.56, Microstrip | @ -20 dB, 0.192 | 7.3 × 7.5 × 0.508 |

| [49], Table 5, Open-short | 9, Microstrip | @ -40 dB, 0.7 | 6.1 × 6.2 × 0.4 |

| Scenario 2, Figure 10, CST | 9.59, Waveguide | @-60 dB, 2.64 | 265 × 26.5 × 26.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).