Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

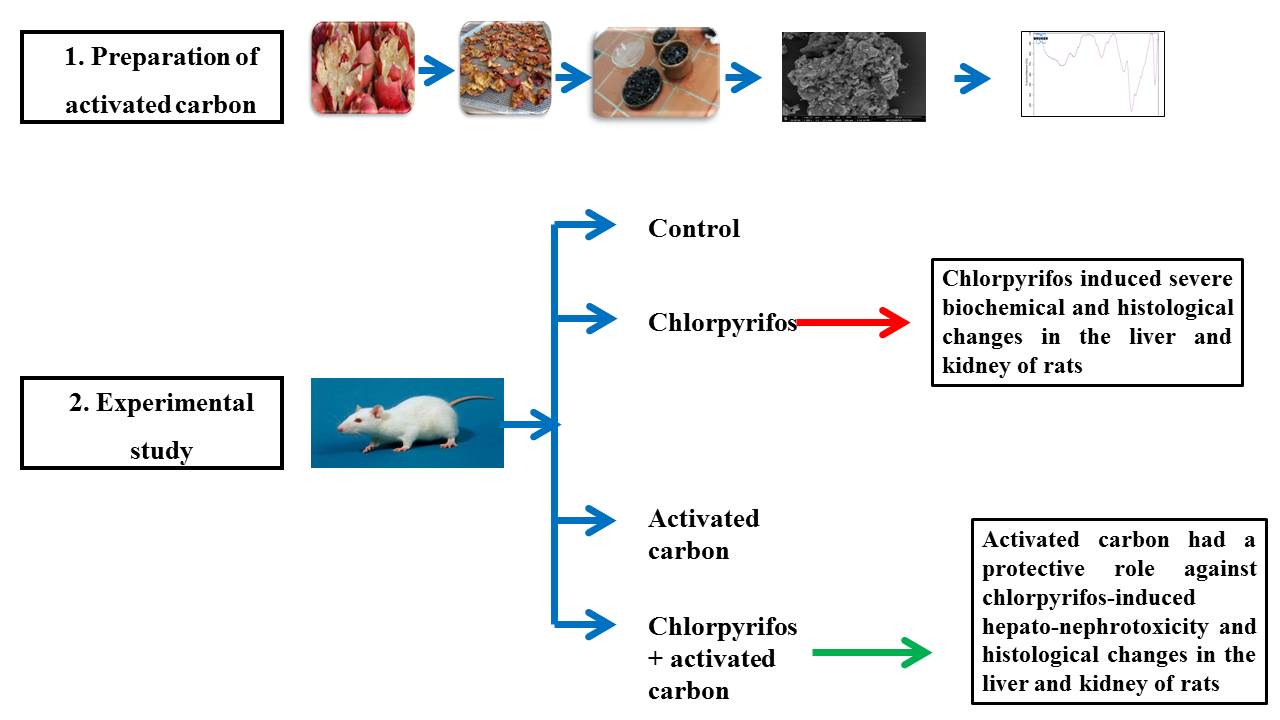

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Preparation of Punica granatum Peels

2.3. Chemicals

2.4. Preparation of Punica granatum Peels-Based Activated Carbons (PgP-ACs)

2.5. Characterization of Punica granatum Peels- Based Activated Carbon (PgP-ACs)

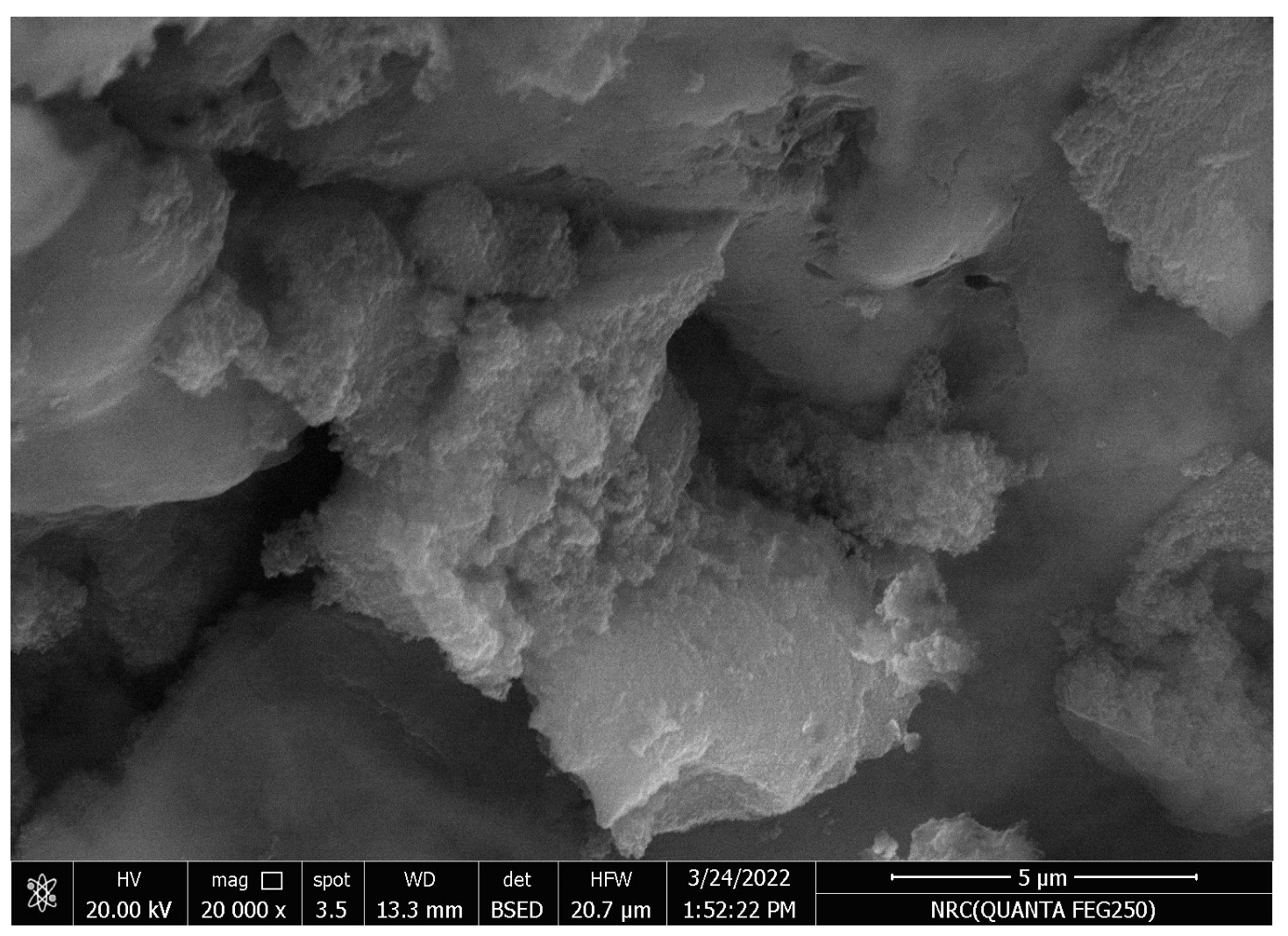

2.5.1. Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

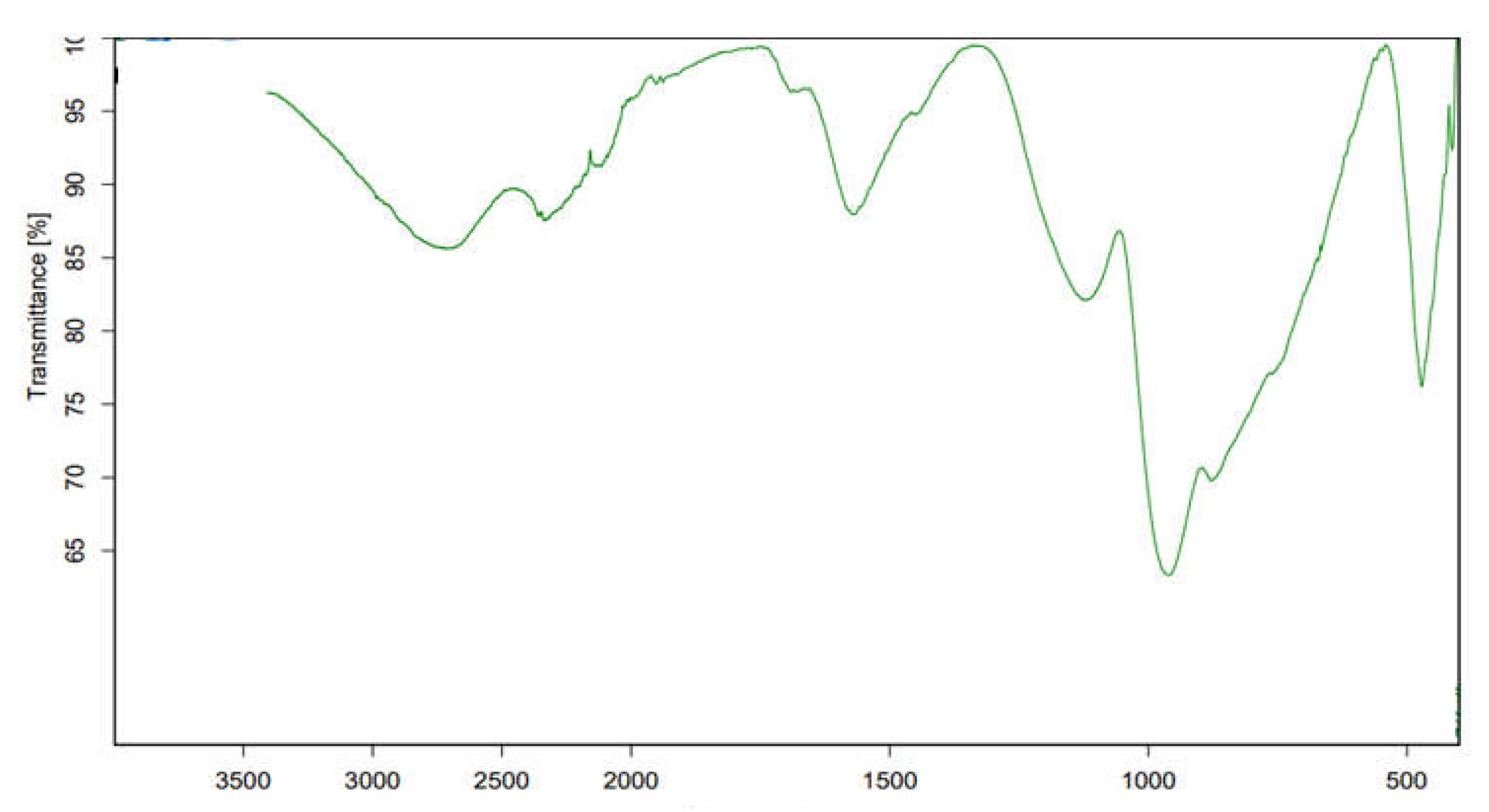

2.5.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.6. Experimental Animals

2.7. Experimental Design

2.8. Biochemical Assay

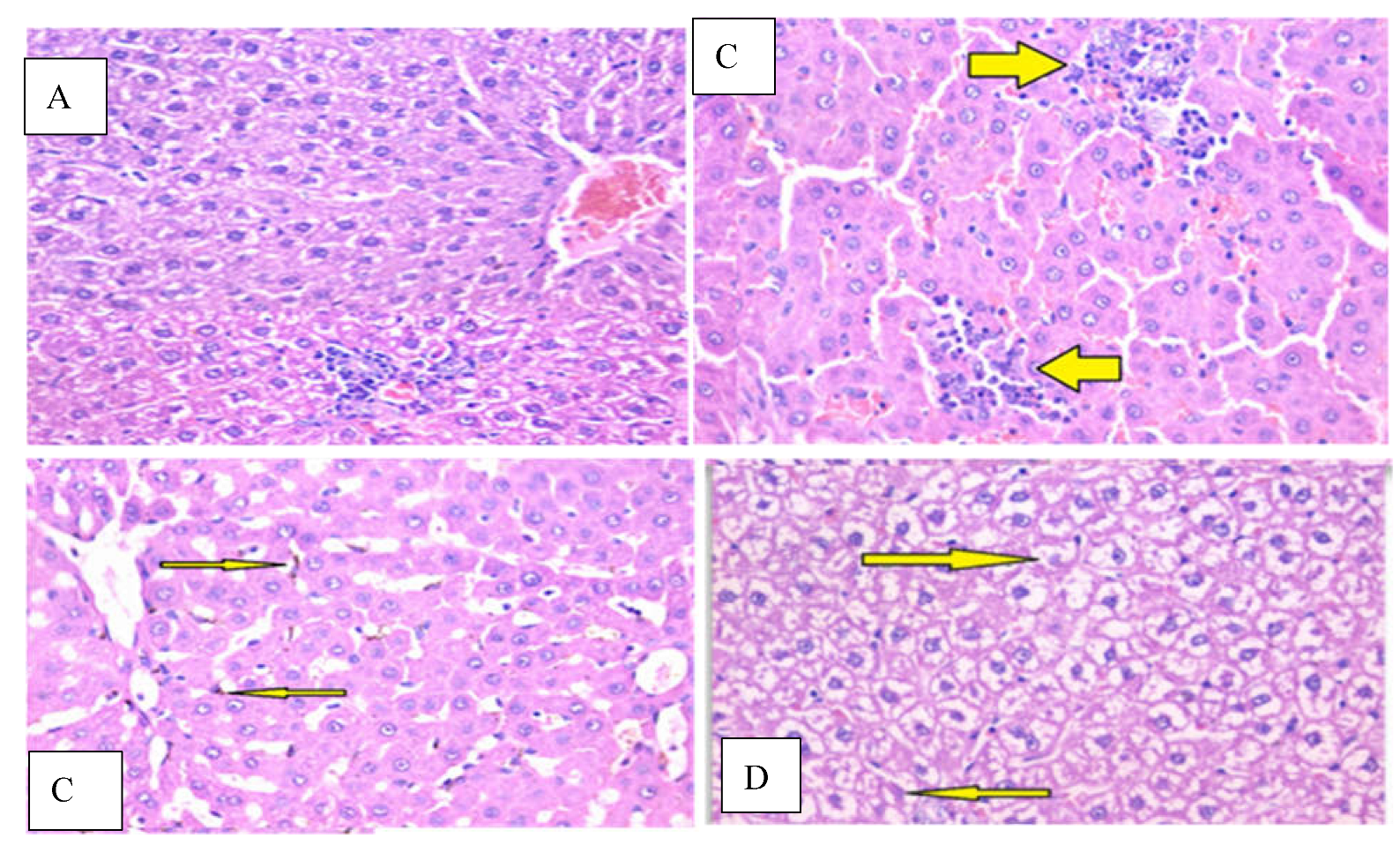

2.9. Histopathological Studies

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Transmission Electron Microscope

3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

3.3. Body Weight and Feed Intake

3.4. Biochemical Parameters

3.4.1. Serum Biochemical Markers of Liver Function

3.4.2. Serum Biochemical Markers of Kidney Function

3.5. Lipid Profile

3.6. Effect of PgP-ACs on Histology of Kidney and Liver in Chlorpyrifos -Induced Toxicity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LDL | Low Density Lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HDL | High Density Lipoprotein cholesterol |

| ALP | Serum Alkaline Phosphatase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| γ-GGT | γ-Glutamyl Transferase |

| PgP | Punica granatum L. peels |

| PgP-ACs | Punica granatum L. peels–derived activated carbon |

References

- Akash, S. , Sivaprakash, B., Rajamohan, N., Pandiyan, C. M., Vo, D. V. N. Pesticide pollutants in the environment–A critical review on remediation techniques, mechanism and toxicological impact. Chemosphere, 2022, 301, 134754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foong, S. Y. , Ma, N. L., Lam, S. S., Peng, W., Low, F., Lee, B. H., Sonne, C. A. recent global review of hazardous chlorpyrifos pesticide in fruit and vegetables: Prevalence, remediation and actions needed. J Hazard Mater, 1230. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H. , Ge, Y., Liu, X., Deng, S., Li, J., Tan, P., Wu, Z. (2024). Exposure to the environmental pollutant chlorpyrifos induces hepatic toxicity through activation of the JAK/STAT and MAPK pathways. Sci Total Envir, 1717. [Google Scholar]

- Hathout, A. , Amer, M., Hussain, O., Yassen, A. A., Mossa, A. T. H., Elgohary, M. R. Estimation of the most widespread pesticides in agricultural soils collected from some Egyptian governorates. Egypt J Chem.

- Hathout, A. S. , Saleh, E., Hussain, O., Amer, M., Mossa, A. T., Yassen, A. A. Determination of pesticide residues in agricultural soil samples collected from Sinai and Ismailia Governorates, Egypt. Egypt J Chem.

- Wołejko, E. , Łozowicka, B., Jabłońska-Trypuć, A., Pietruszyńska, M., Wydro, U. Chlorpyrifos occurrence and toxicological risk assessment: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 1220. [Google Scholar]

- Küçükler, S. , Çomaklı, S., Özdemir, S., Çağlayan, C., & Kandemir, F. M. (2021). Hesperidin protects against the chlorpyrifos-induced chronic hepato-renal toxicity in rats associated with oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, autophagy, and up-regulation of PARP-1/VEGF. Environ Toxicol, 1600. [Google Scholar]

- Alruhaimi, R. S. , Ahmeda, A. F., Hussein, O. E., Alotaibi, M. F., Germoush, M. O., Elgebaly, H. A.,... & Mahmoud, A. M. Galangin attenuates chlorpyrifos-induced kidney injury by mitigating oxidative stress and inflammation and upregulating Nrf2 and farnesoid-X-receptor in rats. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol, 2024, 110, 104542. [Google Scholar]

- Jebur, A. B. , El-Sayed, R. A., Abdel-Daim, M. M., & El-Demerdash, F. M. Punica granatum (pomegranate) peel extract pre-treatment alleviates fenpropathrin-induced testicular injury via suppression of oxidative stress and inflammation in adult male rats. Toxics.

- Shaban, N.Z.; El-Kersh, M.A.; El-Rashidy, F.H.; Habashy, N.H. Protective role of Punica granatum (pomegranate) peel and seed oil extracts on diethylnitrosamine and phenobarbital-induced hepatic injury in male rats. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, M. Z. , Abo-El-Matty, D. M., Aly, H. F., Abd-Alla, H. I., Saleh, S. M., Younis, E. A., Haroun, A. A. Therapeutic activity of sour orange albedo extract and abundant flavanones loaded silica nanoparticles against acrylamide-induced hepatotoxicity. Toxicol Rep 2018, 5: 929-942.

- Mohamed, N. Z. , Abd-Alla, H. I., Aly, H. F., Mantawy, M., Ibrahim, N., & Hassan, S. A. CCl4-induced hepatonephrotoxicity: protective effect of nutraceuticals on inflammatory factors and antioxidative status in rat. J Appl Pharmaceut Sci.

- Shalaby, N. M. , Abd-Alla, H. I., Ahmed, H. H., Basoudan, N. Protective effect of Citrus sinensis and Citrus aurantifolia against osteoporosis and their phytochemical constituents. J Med Plants Res, 2011, 5, 579–588. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, A. A. A. H. , Gad, M. F., Refaie, A. A., Abdelhafez, H. M., Mossa, A. T. H. Benchmark Dose Approach to DNA and liver damage by chlorpyrifos and imidacloprid in male rats: the protective effect of a clove-oil-based nanoemulsion loaded with pomegranate peel extract. Toxics.

- Zhang, M. , Tang, X., Mao, B., Zhang, Q., Zhao, J., Chen, W., Cui, S. Pomegranate: A Comprehensive Review of Functional Components, Health Benefits, Processing, Food Applications, and Food Safety. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 10, 5649–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H. Y. , Chen, S. S., Liao, W., Wang, W., Jang, M. F., Chen, W. H., Wu, K. C. W. Assessment of agricultural waste-derived activated carbon in multiple applications. Environ Res, 2020, 191, 110176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadi, W. , Rodríguez-Sánchez, S., Ruiz, B., Najar-Souissi, S., Ouederni, A., Fuente, E. From pomegranate peels waste to one-step alkaline carbonate activated carbons. Prospect as sustainable adsorbent for the renewable energy production. J Environ Chem Eng, 1070. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, A. , Nazir, M. A., Salem, M. A., Ragab, S., El Nemr, A. Magnetic pomegranate peels activated carbon (MG-PPAC) composite for Acid Orange 7 dye removal from wastewater. Appl Water Sci 2024, 14, 178.–content. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S. A. , Singh, S., Nayik, G. A. Bioactive compounds from pomegranate peels-Biological properties, structure–function relationships, health benefits and food applications–A comprehensive review. J Funct Foods, 1061. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z. , Foo, S. C., Choo, W. S. A review on the extraction of polyphenols from pomegranate peel for punicalagin purification: techniques, applications, and future prospects. Sustainable Food Technology.

- Inyang, M. I. , Gao, B., Yao, Y., Xue, Y., Zimmerman, A., Mosa, A., Cao, X. A review of biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal. Critical Reviews in Environ Sci Technol.

- Ruiz, B. , Ferrera-Lorenzo, N., Fuente, E. Valorisation of lignocellulosic wastes from the candied chestnut industry. Sustainable activated carbons for environmental applications. J Environ Chem Eng, 2017, 5, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukanwa, K. S. , Patchigolla, K., Sakrabani, R., Anthony, E., Mandavgane, S. A review of chemicals to produce activated carbon from agricultural waste biomass. Sustainability, 6204. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, H. , Wang, X., Xu, Q., Dhaouadi, F., Sellaoui, L., Seliem, M. K., Li, Q. Adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution on activated carbons and composite prepared from an agricultural waste biomass: A comparative study by experimental and advanced modeling analysis. Chem Eng J, 1328. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbas, E. , Kobya, M. K. A. E., Konukman, A. E. S. Error analysis of equilibrium studies for the almond shell activated carbon adsorption of Cr (VI) from aqueous solutions. J Hazard Mater.

- Cabal, B. , Budinova, T., Ania, C. O., Tsyntsarski, B., Parra, J. B., Petrova, B. Adsorption of naphthalene from aqueous solution on activated carbons obtained from bean pods. J Hazard Mater, 1150. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo, J. , Gómez-Serrano, V., Álvarez, P. M. Enhanced adsorption of metal ions onto functionalized granular activated carbons prepared from cherry stones. J Hazard Mater.

- M Berrios, M. , Martin, M. A., Martin, A. Treatment of pollutants in wastewater: Adsorption of methylene blue onto olive-based activated carbon. J Ind Eng Chem.

- S. M. Yakout, S. M., El-Deen, G. S. Characterization of activated carbon prepared by phosphoric acid activation of olive stones. Arab J Chem 2016, 9, S1155–S1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D. , Singh, K. P., Singh, V. K. Wastewater treatment using low cost activated carbons derived from agricultural byproducts—a case study. J Hazard Mater 2008, 152, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, L. , Saravanan, P., Kumaraguru, K., AnnamRenita, A., Rajeshkannan, R., Rajasimman, M. A facile approach in activated carbon synthesis from wild sugarcane for carbon dioxide capture and recovery: isotherm and kinetic studies. Biomass Convers Biorefin, 9595. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, O. A. , Hathout, A. S., Abdel-Mobdy, Y. E., Rashed, M. M., Rahim, E. A., & Fouzy, A. S. M.Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from agricultural wastes and their ability to remove chlorpyrifos from water. Toxicol Rep, 2023, 10, 146–154. [Google Scholar]

- Girgis, B. S. , Elkady, A. A., Attia, A. A., Fathy, N. A., Abdel Wahhab, M. A. Impact of air convection on H 3 PO 4-activated biomass for sequestration of Cu (II) and Cd (II) ions. Carbon Lett.

- Kaur, J. , Sarma, A. K., Jha, M. K., Gera, P. Rib shaped carbon catalyst derived from Zea mays L. cob for ketalization of glycerol. RSC Adv 2020, 10(71), 43334–43342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, O. A. , Rahim, E. A. A., Badr, A. N., Hathout, A. S., Rashed, M. M., Fouzy, A. S. Total phenolics, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity of agricultural wastes, and their ability to remove some pesticide residues. Toxicol Rep 2022, 9, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Guide fot the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. The National Academic Press, 2011.

- Wang, H. P. , Liang, Y. J., Long, D. X., Chen, J. X., Hou, W. Y., Wu, Y. J. Metabolic profiles of serum from rats after subchronic exposure to chlorpyrifos and carbaryl. Chem Res Toxicol 2009, 22(6), 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. , Pang, G., Ren, F., Fang, B. Chlorpyrifos-induced reproductive toxicity in rats could be partly relieved under high-fat diet. Chemosphere.

- Fries, G. F. , Marrow Jr, G. S., Gordon, C. H., Dryden, L. P., Hartman, A. M. Effect of activated carbon on elimination of organochlorine pesticides from rats and cows. J Dairy Sci 1970, 53, 1632–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, Z. K. , Hathout, A. S., Ostroff, G., Soto, E., Sabry, B. A., El-Hashash, M. A., Aly, S. E. Assessment of the protective effect of yeast cell wall β-glucan encapsulating humic acid nanoparticles as an aflatoxin B1 adsorbent in vivo. J Biochem Mol Toxicol, 2294. [Google Scholar]

- Drury, R. A. B. , Wallington, E. A. Preparation and fixation of tissues. Carleton Histol Tech. 1980, 5, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdipour-Ataei, S. , Aram, E. Mesoporous carbon-based materials: A review of synthesis, modification, and applications. Catalysts.

- Ali, I. , Afshinb, S., Poureshgh, Y., Azari, A., Rashtbari, Y., Feizizadeh, A., Fazlzadeh, M. Green preparation of activated carbon from pomegranate peel coated with zero-valent iron nanoparticles (nZVI) and isotherm and kinetic studies of amoxicillin removal in water. Environ Sci Pollut Res, 3673; 27. [Google Scholar]

- Kristianto, H. , Arie, A. A., Susanti, R. F., Halim, M., Lee, J. K. The effect of activated carbon support surface modification on characteristics of carbon nanospheres prepared by deposition precipitation of Fe-catalyst. In IOP Conference Series: Mat Sci Eng, 2016, 162(1), 012034.

- Qiu, C. , Jiang, L., Gao, Y., Sheng, L. Effects of oxygen-containing functional groups on carbon materials in supercapacitors: A review. Mater Des, 1119. [Google Scholar]

- Tanvir, E. M. , Afroz, R., Chowdhury, M. A. Z., Khalil, M. I., Hossain, M. S., Rahman, M. A., Gan, S. H. Honey has a protective effect against chlorpyrifos-induced toxicity on lipid peroxidation, diagnostic markers and hepatic histoarchitecture. Eur J Integr Med.

- Batool, T. , Noreen, S., Batool, F., Shazly, G. A., Iqbal, S., Irfan, A., Jardan, Y. A. B. Optimization and pharmacological evaluation of phytochemical-rich Cuscuta reflexa seed extract for its efficacy against chlorpyrifos-induced hepatotoxicity in murine models. Sci Rep, 2292. [Google Scholar]

- Nishi, K. , Hundal, S. S. Chlorpyrifos induced toxicity in reproductive organs of female Wistar rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013, 62, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, M. , Hussain, S. M., Ali, S., Rizwan, M., Al-Ghanim, K. A., Yong, J. W. H. Effectiveness of feeding different biochars on growth, digestibility, body composition, hematology and mineral status of the Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Sci Rep, 1352. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, F. R. , Saleh, N. E., Shalaby, S. M., Sakr, E. M., Abd-El-Khalek, D. E., & Abd Elmonem, A. I. Effect of different dietary levels of commercial wood charcoal on growth, body composition and environmental loading of red tilapia hybrid. Aquacult Nutr 2017, 23, 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-Alla, H. I. , Souguir, D., Radwan, M. O. Genus Sophora: a comprehensive review on secondary chemical metabolites and their biological aspects from past achievements to future perspectives. Arch Pharmacal Res.

- Selmi, S. , Rtibi, K., Grami, D., Sebai, H., Marzouki, L. Malathion, an organophosphate insecticide, provokes metabolic, histopathologic and molecular disorders in liver and kidney in prepubertal male mice. Toxicol Rep, 5.

- Banaee, M. , Zeidi, A., Haghi, B. N., Beitsayah, A. The toxicity effects of imidacloprid and chlorpyrifos on oxidative stress and blood biochemistry in Cyprinus carpio. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2024, 284, 109979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , Wang, S. L., Xie, T., Cao, J. Activated carbon derived from waste tangerine seed for the high-performance adsorption of carbamate pesticides from water and plant. Biores Technol 2020, 316, 123929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. , Zhang, Z., Lin, X., Chen, Z., Li, B., Zhang, Y. Removal of imidacloprid and acetamiprid in tea (Camellia sinensis) infusion by activated carbon and determination by HPLC. Food Control, 2022, 131, 108395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-hameed, S. A. , Negm, S. S., Ismael, N. E., Naiel, M. A., Soliman, M. M., Shukry, M., Abdel-Latif, H. M. Effects of activated charcoal on growth, immunity, oxidative stress markers, and physiological responses of Nile tilapia exposed to sub-lethal imidacloprid toxicity. Animals.

- Song, Y. , Liu, J., Zhao, K., Gao, L., Zhao, J. Cholesterol-induced toxicity: An integrated view of the role of cholesterol in multiple diseases. Cell Metabol, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Marí, M. , de Gregorio, E., de Dios, C., Roca-Agujetas, V., Cucarull, B., Tutusaus, A.,.Colell, A. Mitochondrial glutathione: recent insights and role in disease. Antioxidants.

- Aziz, W. M. , Hamed, M. A., Abd-Alla, H. I., Ahmed, S. A. Pulicaria crispa mitigates nephrotoxicity induced by carbon tetrachloride in rats via regulation oxidative, inflammatory, tubular and glomerular indices. Biomarkers 2022, 27, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Saoudi, M. , Badraoui, R., Rahmouni, F., Jamoussi, K., El Feki, A. Antioxidant and protective effects of Artemisia campestris essential oil against chlorpyrifos-induced kidney and liver injuries in rats. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 618582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekkoun, N. , Depeint, F., Guibourdenche, M., El Khayat El Sabbouri, H., Corona, A., Rhazi, L., Khorsi-Cauet, H. Chronic perigestational exposure to chlorpyrifos induces perturbations in gut bacteria and glucose and lipid markers in female rats and their offspring. Toxics.

- Hernáez, Á. , Soria-Florido, M. T., Schröder, H., Ros, E., Pinto, X., Estruch, R., Fitó, M. Role of HDL function and LDL atherogenicity on cardiovascular risk: A comprehensive examination. PloS one, 0218. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, T. J. , Minassa, V. S., Aitken, A. V., Jara, B. T., Felippe, I. S. A., Beijamini, V., Sampaio, K. N. Intermittent exposure to chlorpyrifos differentially impacts neuroreflex control of cardiorespiratory function in rats. Cardiov Toxicol 2019, 19, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, H. A. , Nur, G., Deveci, A., Kaya, I., Kaya, M. M., Kükürt, A., Karapehlivan, M. An overview of the biochemical and histopathological effects of insecticides, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzi, L. , Belhadj Salah, I., Haouas, Z., Sakly, A., Grissa, I., Chakroun, S., Ben Cheikh, H. Histopathological and genotoxic effects of chlorpyrifos in rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res, 4859; 23. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, D. K. , Tripathi, R., Das, V. K., Pandey, R. K. Histopathological changes in liver and kidney of Heteropneustes fossilis (Bloch) on chlorpyrifos exposure. Scientific Temper.

- Kašuba, V. , Tariba Lovaković, B., Lucić Vrdoljak, A., Katić, A., Kopjar, N., Micek, V.,... & Žunec, S. Evaluation of toxic effects induced by sub-acute exposure to low doses of α-cypermethrin in adult male rats. Toxics.

- Ivanović, S. R. , Borozan, N., Janković, R., Ćupić Miladinović, D., Savić, M., Ćupić, V., & Borozan, S. Functional and histological changes of the pancreas and the liver in the rats after the acute and subacute administration of diazinon. Vojnosanit. Pregl.

- Alharbi, F. K. Organophosphate Insecticides Induced Histopathological and Biochemical Changed on Male Rats. Egypt J Chem Environ Health 2018, 4(1), 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, E. , Yancheva, V., Stoyanova, S., Velcheva, I., Iliev, I., Vasileva, T., Antal, L. Which is more toxic? Evaluation of the short-term toxic effects of chlorpyrifos and cypermethrin on selected biomarkers in common carp (Cyprinus carpio, Linnaeus 1758). Toxics 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosheleva, R. I. , Mitropoulos, A. C., Kyzas, G. Z. Synthesis of activated carbon from food waste. Environ Chem Lett 2019, 17, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, A. , Kadirvelu, K. Strategies to design modified activated carbon fibers for the decontamination of water and air. Environ Chem Lett 2018, 16, 1137–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidarinejad, Z. , Dehghani, M. H., Heidari, M., Javedan, G., Ali, I., Sillanpää, M. Methods for preparation and activation of activated carbon: a review. Environ Chem Lett 2020, 18, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M. , Arami, S. M., Takallo, H., Hosseini, M., Radfard, M., Soleimani, H., Mohammadi, A. A. Modification of pumice with HCl and NaOH enhancing its fluoride adsorption capacity: kinetic and isotherm studies. Hum Ecol Risk Assess, 1508. [Google Scholar]

- Snezhkova, E. , Rodionova, N., Bilko, D., Silvestre-Albero, J., Sydorenko, A., Yurchenko, O., Nikolaev, V. Orally administered activated charcoal as a medical countermeasure for acute radiation syndrome in rats. Appl Sci, 3174. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnatskaya, V. , Mikhailenko, V., Prokopenko, I., Gerashchenko, B. I., Shevchuk, O., Yushko, L., Nikolaev, V. The effect of two formulations of carbon enterosorbents on oxidative stress indexes and molecular conformation of serum albumin in experimental animals exposed to CCl4. Heliyon.

| Treatments | Initial(g) | End(g) | Body weight gain(g) | Feed intake(g) | Feed efficiency ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 162.5 ± 10.12 | 211.0 ± 13.18 | 48.5 ± 3.06a | 1890 ± 111 | 0.0257a |

| Chlorpyrifos | 163.5 ± 11.21 | 189.3 ± 11.48 | 25.8 ± 2.14bc | 1902 ± 90 | 0.0136bc |

| PgP-ACs | 157.3 ± 9.40 | 187.4 ± 13.35 | 30.1 ± 1.52b | 1830 ± 121 | 0.0162b |

| Chlorpyrifos + PgP-ACs | 162.8 ± 10.00 | 185.6 ± 11.41 | 22.8 ± 1.41c | 1893 ± 98 | 0.0121c |

| Treatments | ALT (U/L) | AST (U/L) | ALP (U/L) | GGT (U/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 137c ± 11.02 | 161b ± 12.22 | 158b ± 17.11 | 75a ± 5.11 |

| Chlorpyrifos | 167a ± 12.12 | 189a ± 16.15 | 187a ± 19.33 | 82a ± 5.50 |

| PgP-ACs | 142bc ± 10.31 | 164b ± 15.24 | 159b ± 20.13 | 79a ± 4.91 |

| Chlorpyrifos + PgP-ACs | 159b ± 13.14 | 167b ± 14.44 | 168ab ± 18.16 | 80a ± 5.12 |

| Treatments | Urea (mg/dl) | Creatinine (mg/dl) | Uric acid (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 19.00b ± 1.21 | 0.51b ± 0.03 | 1.33b ± 0.10 |

| Chlorpyrifos | 27.67a ± 1.72 | 0.69a ± 0.04 | 2.16a ± 0.16 |

| PgP-ACs | 21.00b ± 2.00 | 0.50b ± 0.04 | 1.67b ± 0.13 |

| Chlorpyrifos + PgP-ACs | 22.13b ± 1.83 | 0.53b ± 0.03 | 1.87ab ± 0.15 |

| Treatments | Cholesterol (mg/dl) | Triglycerides (mg/dl) | HDL (mg/dl) | LDL (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 81.67b ± 5.63 | 58.33c ± 3.27 | 22.00b ± 3.91 | 36.60a ± 1.23 |

| Chlorpyrifos | 107.33a ± 6.66 | 129.33a ± 7.81 | 28.33a ± 4.00 | 26.41b ± 2.13 |

| PgP-ACs | 84.33b ± 5.34 | 74.00c ± 4.16 | 23.40b ± 4.01 | 31.53a ± 1.86 |

| Chlorpyrifos + PgP-ACs | 86.67b ± 5.02 | 108.70b ± 6.09 | 25.00ab ± 3.96 | 28.67ab ± 2.01 |

| Treatments | Liver | Kidney | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic Degeneration | Apoptosis | Inflammation | Others | Glomeruli | Tubules | Other | |

| Control | ±N | - | - | - | ±N | ±N | - |

| Chlorpyrifos | + | + | ++ | - | Focal sclerosis+ | Focal degeneration+ | - |

| PgP-ACs | ±N | - | - | Kupffer cell hyperplasia+ | ±N | ±N | |

| Chlorpyrifos + PgP-ACs | ±N | - | Portal+ | - | ±N | ±N | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).