1. Introduction

The production of developmentally competent oocytes is central to female fertility and the success of species propagation. Oocyte maturation is an intricate process that encompasses a series of tightly coordinated nuclear and cytoplasmic events, including germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD), meiotic resumption, spindle formation, chromatin remodeling, and cytoplasmic preparation for fertilization and subsequent embryonic development [

1]. Disruptions to these processes can reduce the efficiency of reproductive outcomes by impairing ovulation, fertilization, or early embryogenesis. Understanding the mechanisms underlying oocyte and embryo quality is therefore crucial for advancing both natural and assisted reproductive technologies (ART).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), including fluoxetine, are among the most widely prescribed antidepressants globally [

2]. Their use has significantly increased among women of reproductive age, including those planning pregnancy or undergoing fertility treatments [

3]. Fluoxetine acts by increasing serotonin levels at synapses in the central nervous system, a mechanism that alleviates depressive symptoms [

4]. However, serotonin signaling is not confined to neural tissues; serotonin receptors and transporters are also expressed in peripheral systems, including the ovary, uterus, and early embryo [

5,

6]. This raises critical questions regarding the potential off-target effects of SSRIs on female reproductive physiology.

While fluoxetine has been associated with delayed conception, reduced fertilization rates, and pregnancy complications in some clinical studies [

7,

8], the specific effects of chronic fluoxetine exposure on oogenesis and embryo development are not well understood. Previous research has suggested that SSRIs may modulate ovarian function by interfering with hormonal signaling or oocyte maturation [

9,

10,

11], yet evidence on how fluoxetine influences key oocyte quality markers, such as spindle integrity, cytoplasmic maturation, and developmental competence, remains limited. Moreover, the impact of maternal fluoxetine exposure on offspring development, including their reproductive potential, has yet to be systematically explored.

This study was designed to address these gaps by examining the effects of fluoxetine on critical stages of female reproduction in a mouse model, with a focus on (i) the quantity and quality of ovulated oocytes, (ii) the cytoplasmic and nuclear maturation of GV-stage oocytes, and (iii) the developmental competence of oocytes and embryos following fertilization. By combining molecular, morphological, and functional assessments, we sought to elucidate the mechanisms by which fluoxetine might impair oocyte developmental potential and alter early reproductive outcomes. Additionally, we aimed to evaluate whether maternal fluoxetine administration affects offspring growth and ovarian reserve, with implications for intergenerational fertility.

These findings are expected to contribute to our understanding of the broader implications of SSRI use for female reproductive health, particularly in individuals undergoing ART or planning pregnancies, and may guide clinical decision-making regarding the safety of antidepressant use during this critical period.

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Fluoxetine on the Quantity and Quality of Ovulated MII Oocytes

Female mice treated with fluoxetine via drinking water continued to exhibit regular estrous cyclicity, as confirmed by characteristic changes in cellular composition observed in vaginal smears. After 10 days of fluoxetine administration, cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were retrieved from oviductal ampullae following superovulation induction. The COCs were treated with hyaluronidase, denuded, and the collected oocytes were analyzed for their quantity and quality.

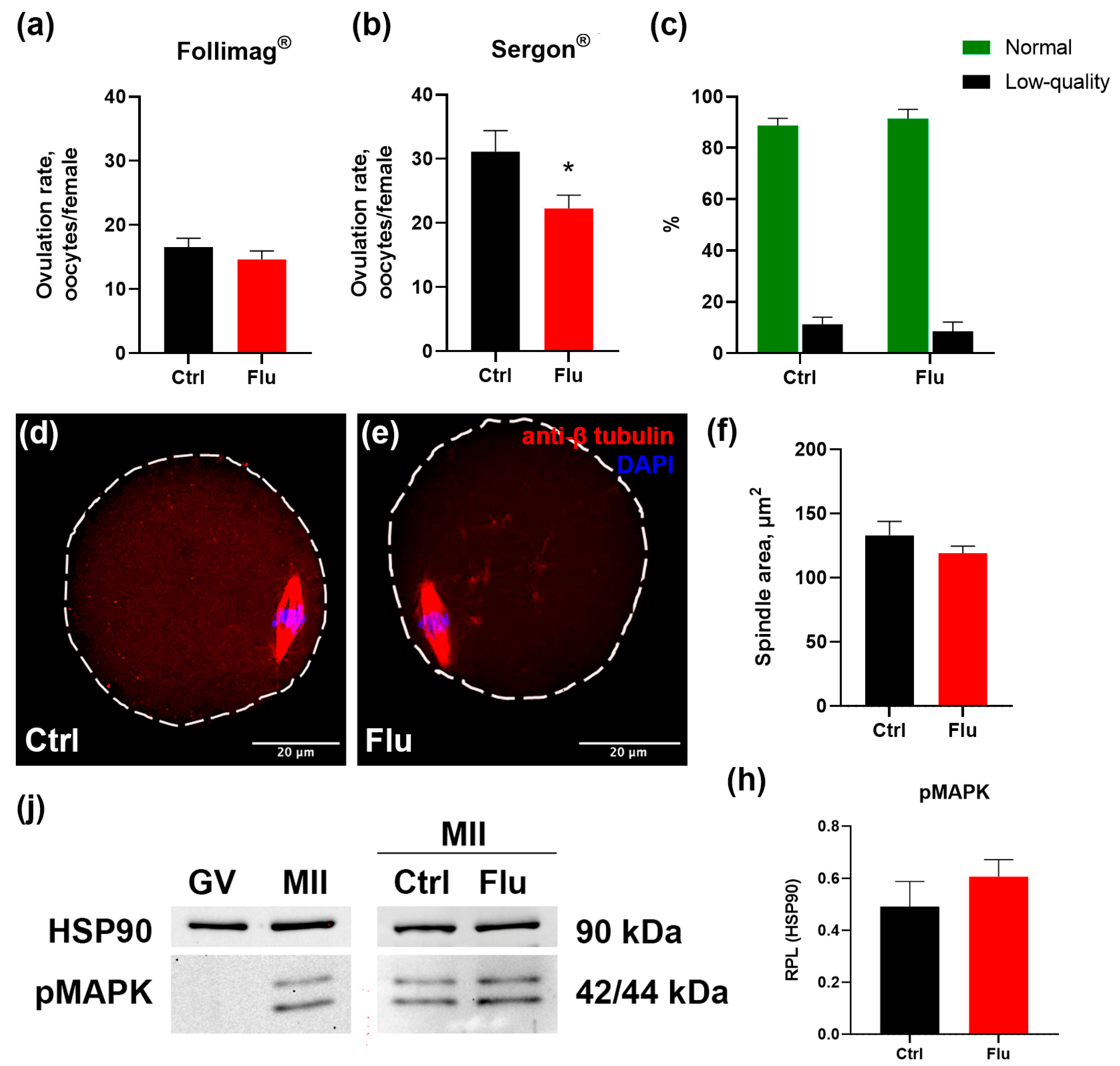

The mean number of ovulated mature MII oocytes per female is shown in

Figure 1a-b. In the group treated with fluoxetine, the average number of ovulated oocytes decreased significantly from 29 to 23 per mouse, reflecting a 20% reduction compared to the control group. This negative effect of fluoxetine was consistently observed with the use of different hormonal preparations for superovulation – Follimag

® (

Figure 1a) and Sergon

® (

Figure 1b).

Morphological analysis of oocyte quality revealed no significant differences in the proportion of normal MII oocytes versus fragmented or degenerating oocytes between the fluoxetine-treated and control groups. In both groups, the proportion of abnormal oocytes remained low and did not exceed 15% (

Figure 1c).

To evaluate whether fluoxetine influenced spindle assembly in MII-stage oocytes, oocytes were immunostained with anti-tubulin beta antibodies and analyzed by confocal microscopy (

Figure 1d-e). Abnormal spindles were observed only in rare instances in both the control and fluoxetine-treated groups. Furthermore, quantitative measurements of the lateral projection area of the spindles showed no differences between groups (

Figure 1f), indicating that fluoxetine did not disrupt spindle organization or the process of spindle assembly.

The possible impact of fluoxetine on nuclear meiotic maturation was assessed by quantifying phosphorylated MAPK, a marker of meiotic progression. This active kinase is present in MII oocytes but absent in GV oocytes prior to GVBD (

Figure 1j). Levels of phosphorylated MAPK in MII oocytes collected from fluoxetine-treated females were similar to those in control oocytes (

Figure 1h).

Taken together, these findings suggest that the observed reduction in the number of ovulations in fluoxetine-treated animals is not associated with apparent disruptions in oocyte maturation processes, as evidenced by normal spindle formation, chromatin organization, and MAPK activation in MII-stage oocytes.

2.2. Effects of Fluoxetine on GV Oocyte Maturation and Cumulus Expansion In Vitro (IVM)

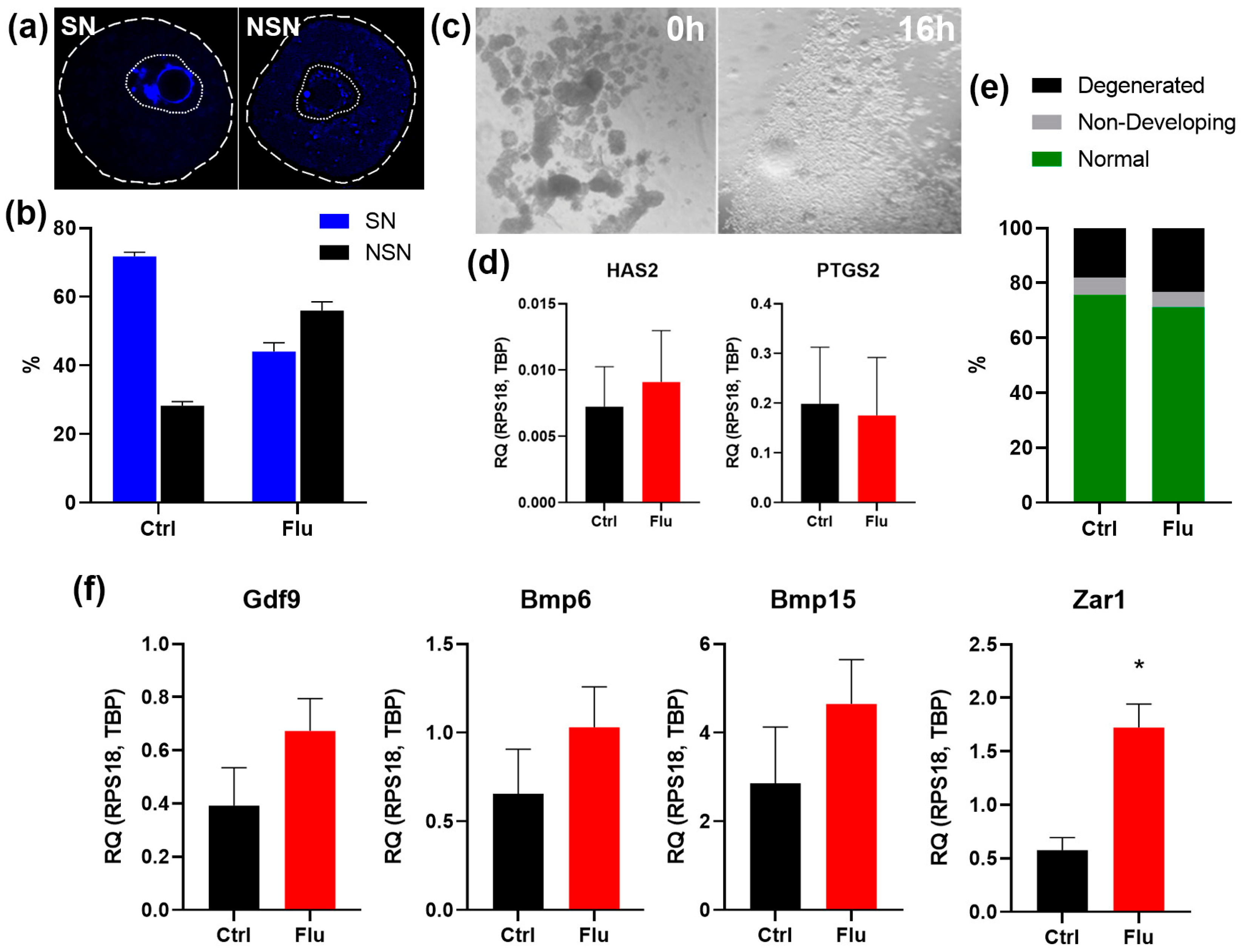

To assess the potential effects of fluoxetine on earlier stages of oogenesis, we analyzed the maturation of GV-stage oocytes obtained 36 hours after superovulation induction. Morphological analysis of chromatin structure revealed a significant reduction in the proportion of fully mature SN (surrounded nucleolus) oocytes in the fluoxetine-treated group (42%) compared to the control group (72%) (

Figure 2a-b). This result suggests a delay in cytoplasmic maturation of GV oocytes, which could underlie the observed decrease in ovulated oocyte numbers in fluoxetine-treated females.

To further evaluate the developmental potential of GV oocytes, we assessed their capacity for in vitro maturation (IVM) as oocyte-cumulus complexes. Both the control and fluoxetine-treated groups demonstrated successful cumulus expansion in response to EGF supplementation, as confirmed by morphological analysis (

Figure 2c). Additionally, quantitative PCR analysis of cumulus-specific marker genes, Has2 and Ptgs2, revealed no significant differences in gene expression between the experimental and control groups (

Figure 2d). This indicates that fluoxetine does not disrupt granulosa cell differentiation into cumulus cells.

Morphological analysis of oocytes following IVM, however, revealed a decrease in the proportion of mature MII-stage oocytes in the fluoxetine-treated group and an associated increase in the proportion of degenerated oocytes (

Figure 2e). This may be attributed to incomplete cytoplasmic maturation of GV oocytes observed in fluoxetine-treated females.

To investigate the molecular characteristics of fluoxetine-exposed MII-stage oocytes, we analyzed the expression levels of key oocyte growth factor mRNAs, including Gdf9, Bmp6, and Bmp15, via Real-time qPCR (

Figure 2f). Interestingly, mRNA levels for these genes were slightly elevated in the fluoxetine-treated group compared to controls. However, the level of Zar1, a negative marker of cytoplasmic maturity, was also found to be higher in the fluoxetine-treated group (

Figure 2f). This indicates that the fluoxetine-treated MII oocytes displayed a less mature cytoplasmic state compared to the control group.

In summary, fluoxetine treatment led to impaired cytoplasmic maturation at the GV stage, resulting in compromised oocyte quality at the MII stage.

2.3. Effects of Fluoxetine on Reproduction and Developmental Potential

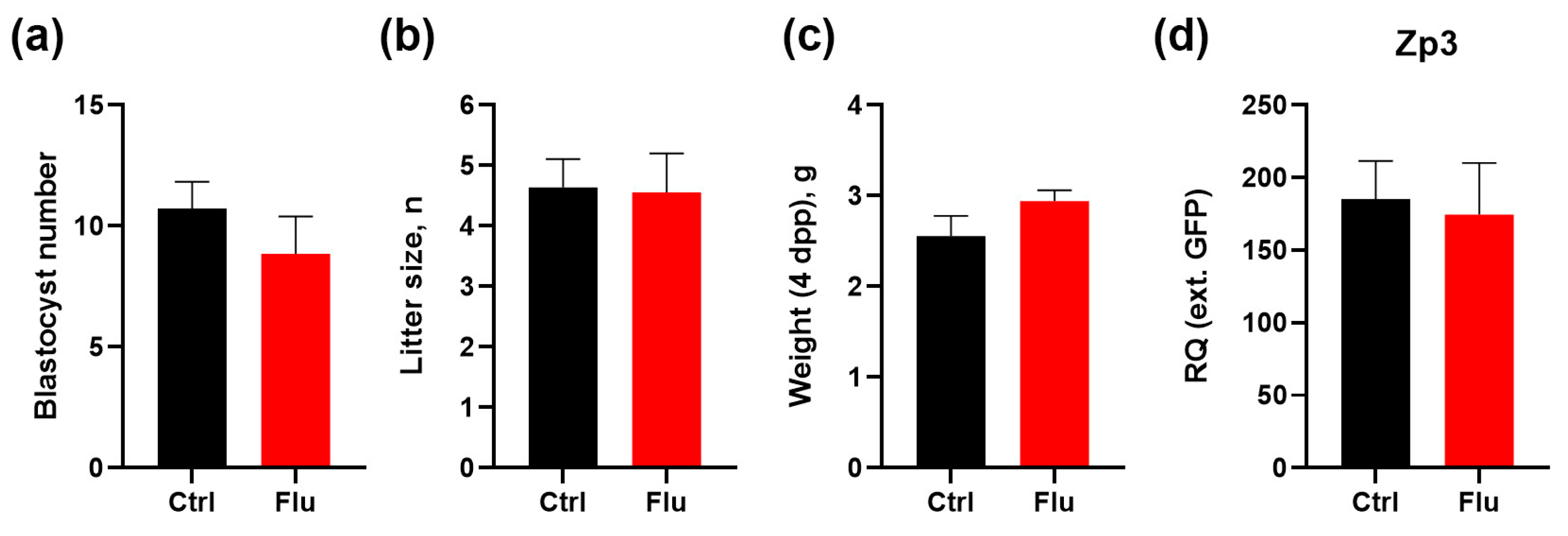

To evaluate the effects of fluoxetine on embryonic development and offspring outcomes, we monitored the number of blastocysts present in uterine horns following natural pregnancies, confirmed by the presence of vaginal plugs. The average number of blastocysts was reduced by 17.5% in the group of females treated with fluoxetine compared to the control group (

Figure 3a). This reduction aligns with the observed decrease in the number of ovulated MII oocytes.

Despite this reduction in blastocyst numbers, the litter size in both groups showed no significant differences, indicating that fluoxetine treatment did not impair the ability of embryos to develop to term (

Figure 3b). Interestingly, the average body weight of pups born from fluoxetine-treated females was slightly increased by 15% compared to pups from the control group (

Figure 3c).

To assess whether maternal fluoxetine exposure affected the ovarian reserve of female offspring, 4-day postpartum (4 dpp) female pups were analyzed for expression of the oocyte-specific marker Zp3 in ovaries. Quantitative analysis revealed no significant differences in ovarian reserve between female offspring born to fluoxetine-treated mothers and those born to untreated controls (

Figure 3d).

These findings suggest that while fluoxetine treatment during pre-conception and pregnancy results in a modest reduction in blastocyst numbers, it does not adversely affect litter size, enhances offspring body weight, and does not compromise the ovarian reserve of female progeny.

3. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of fluoxetine on oocyte maturation, ovarian function, and developmental potential in female mice, providing novel insights into how this widely prescribed antidepressant influences key stages of reproduction. Our findings reveal that fluoxetine treatment does not significantly disrupt oocyte quality or meiotic spindle formation at the MII stage, yet it reduces the number of ovulated oocytes and impairs cytoplasmic maturation during earlier stages of oogenesis. Additionally, fluoxetine exposure was associated with a modest reduction in blastocyst numbers but did not adversely affect overall litter size or offspring ovarian reserve. Surprisingly, we observed an increase in pup body weight, representing a potentially unexpected maternal drug-related effect.

The observed reduction in ovulated MII oocyte numbers following fluoxetine treatment aligns with prior studies linking selective SSRIs to impaired ovarian function [

9,

12]. Despite this quantitative deficit, the quality of ovulated oocytes was largely unaffected, as evidenced by consistent proportions of normal MII oocytes and intact spindle morphology between fluoxetine-treated and control groups. The maintenance of spindle structure and chromatin organization suggests that fluoxetine’s effects may primarily target processes upstream of meiotic completion, such as cytoplasmic or nuclear maturation during the GV stage [

13].

Our results highlight a potential mechanism by which fluoxetine impairs oocyte developmental potential: through disruptions in cytoplasmic maturation at the GV stage. The lower proportion of SN chromatin configuration in GV oocytes from fluoxetine-treated females indicates delayed or incomplete cytoplasmic maturation [

14]. This delay could explain the reduced efficiency of in vitro maturation to the MII stage observed in this study. Moreover, molecular analysis of oocyte-derived growth factors mRNAs (Gdf9, Bmp6, Bmp15) in fluoxetine-treated oocytes revealed slightly elevated levels, which might reflect a compensatory response to developmental insufficiency [

15]. Similarly, the increased expression of Zar1, a marker of cytoplasmic immaturity [

16], further supports the notion that fluoxetine-treated oocytes exhibit a less mature state. Collectively, these findings emphasize the critical role of cytoplasmic maturation in establishing oocyte competence for subsequent embryonic development.

The impact of fluoxetine extended beyond oocyte maturation and ovulation, influencing embryonic development and offspring characteristics. Fluoxetine-treated females exhibited a modest 17.5% reduction in blastocyst numbers, consistent with the decreased number of ovulated oocytes. However, despite this reduction, litter sizes in fluoxetine-treated and control groups were comparable, indicating that the embryos that successfully implanted retained the capacity to reach term. A notable and unexpected finding was the increased body weight of pups born to fluoxetine-treated mothers, which may represent altered maternal-embryonic metabolic signaling or compensatory adaptations during gestation [

17]. Importantly, there was no significant effect on the ovarian reserve of female offspring, as indicated by comparable levels of Zp3 expression in neonatal ovaries across treatment groups. This suggests that maternal fluoxetine exposure does not compromise the reproductive potential of future generations under the conditions studied.

Our findings have several broader implications in the contexts of reproductive biology and clinical practice. First, while fluoxetine-induced delays in cytoplasmic maturation may impair oocyte developmental competence in vitro, the absence of significant defects in spindle stability and chromatin organization suggests that fluoxetine-treated oocytes maintain sufficient structural integrity for fertilization and embryogenesis under physiological conditions. Second, the reduction in blastocyst numbers highlights the need to carefully consider the use of fluoxetine in women undergoing ART, where a reduced oocyte yield could diminish the overall success rate. However, the lack of adverse effects on litter size and ovarian reserve is reassuring for women taking fluoxetine during pregnancy or preconception, as it suggests no substantial long-term impact on offspring fertility.

A key limitation of this study is the inability to fully delineate the molecular mechanisms driving the observed alterations in oogenesis and embryogenesis. Further research is needed to explore whether fluoxetine’s effects on oocyte maturation result from direct action on ovarian serotonin systems or indirect alterations in endocrine and metabolic pathways. Additionally, the dose-dependent effects of fluoxetine on reproduction remain unexplored and should be prioritized in future studies.

In summary, our findings provide new evidence that fluoxetine treatment impairs oocyte quantity and competency through disruptions in cytoplasmic maturation while preserving structural integrity and developmental potential of fertilized embryos. Although blastocyst production is modestly reduced, the absence of negative effects on litter size, offspring reproductive potential, and maternal health points to a nuanced role of fluoxetine in reproduction. These insights are critical for understanding the reproductive risks associated with SSRI use and evaluating their implications for fertility and ART outcomes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Animals and Chemicals

Female ICR mice were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of the Koltzov Institute of Developmental Biology RAS and used for all animal experiments. Mice were housed under controlled environmental conditions (22–24°C, 14L:10D photoperiod) with ad libitum access to food and water. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Council of the European Communities Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC) and approved by the Commission on Bioethics of the Koltzov Institute of Developmental Biology of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Fluoxetine hydrochloride (Macklin Inc., Shanghai, China; catalog number F844356) was used in this study. It was dissolved in drinking water at a concentration of 0.13 mg/mL, as previously described [

18,

19].

4.2. Superovulation Protocol and Oocyte and Embryo Retrieval

Mature female mice (2 months old) were superovulated via intraperitoneal injection of 5 IU of PMSG (Follimag, Mosagrogen, Moscow, Russia; or Sergon, Bioveta Inc., Ivanovice na Hané, Czech Republic) between 9:00 PM and 10:00 PM. Forty to forty-six hours post-PMSG injection, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 5 IU hCG at 7:00–8:00 PM. GV-oocyte isolation: Ovaries were harvested 36 hours post-PMSG injection, rinsed in ice-cold dPBS, and placed in L-15 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), pre-warmed to 37°C. Germinal vesicle (GV)-stage oocytes were released by puncturing antral follicles with a 29G needle. MII-oocyte isolation: 16 hours post-hCG injection, oviducts were dissected and placed in ice-cold dPBS. Cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were collected from the ampulla using a V-Denupet Handle (Vitromed, Germany). COCs were then transferred to a four-well plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) containing L-15 medium supplemented with 80 U/mL hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 minutes to remove cumulus cells. Denuded metaphase II (MII)-stage oocytes were then washed three times for 5 minutes each in L-15 medium. Blastocyst Collection: For blastocyst collection, female mice were placed with males overnight. Detection of a vaginal plug was considered 0.5 days post coitum (dpc). Blastocysts were collected at 3.5 dpc by flushing the uterus with dPBS.

4.3. In Vitro Oocyte Maturation and Cumulus Oocyte Complex Expansion

Cumulus-oocyte complexes were isolated by puncturing mouse ovaries 24 hours after PMSG injection in L-15 medium preheated to 37°C. Non-expanded COCs were collected using a V-Denupet Handle and placed in DMEM/F12 medium (PanEco, Moscow, Russia) supplemented with 3 mM L-glutamine (PanEco, Moscow, Russia), 10% FBS (PanEco, Moscow, Russia), gentamicin (PanEco, Moscow, Russia) and 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF) (PanEco, Moscow, Russia). Expansion status and oocyte maturation were evaluated by microscopic examination after overnight culture at 37°C under a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

4.4. Immunohistochemistry

Isolated oocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, permeabilized with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) (PBST), and treated with 0.5% SDS for 1 minute to remove the zona pellucida. Samples were then washed in PBST, blocked with 5% FBS in PBST, and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with a mouse anti-β-tubulin antibody (1:10,000; ABClonal, Wuhan, China; catalog number AC021). After washing in PBST, samples were stained with goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody conjugated with CF 568 (1:500; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany; catalog number sab4600312). DNA was counterstained with DAPI (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) to visualize GV chromatin configuration. Samples were washed three times with PBST and mounted in Mowiol (Sigma-Aldrich) for confocal microscopy.

4.5. Image Analysis

Samples were analyzed using a Zeiss LSM 880 Airyscan confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using consistent settings for objectives, pinhole size, laser intensity, and detector sensitivity across all experiments. Images were processed and analyzed using FIJI software (ImageJ 2.9.0/1.54f, open-source, available at

https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Spindle size was measured using the area tool for regions of interest.

4.6. Western Blotting

GV- and MII-oocyte samples (50-100 oocytes per sample) were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA; catalog number 5872S). Lysates were denatured in Laemmli buffer for 30 minutes at 37°C. SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and protein transfer were performed as previously described [

20]. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit mAb phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204) (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA; catalog number 20G11) and rabbit anti-HSP90AB1 (1:5000; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany; catalog number sab4300541). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:50,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, West Grove, PA, USA; catalog number 111-035-144) was used as a secondary antibody. After washing in TBST, protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 12.5 mM luminol, 2 mM coumaric acid, and 0.09% H

2O

2). Band intensities were quantified using Image Lab software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and normalized to HSP90 protein levels.

4.7. Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the guanidine isothiocyanate method with an RNA extraction reagent (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia). RNA samples were treated with DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Purified RNA was reverse transcribed using random hexadeoxynucleotides and Magnus transcriptase (for oocytes) or Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (for granulosa cells and ovaries) (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and a qPCRmix-HS SYBR + HighROX kit (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia). Gene expression levels were normalized to the reference genes RPS18 and TBP using the 2−∆Ct method, with consistent threshold conditions for all genes. Primer sequences are listed in

Table 1.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise stated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.N.; methodology, D.A.N. and Y.O.N.; investigation, M.D.T., N.M.A., V.S.F.; data curation, M.D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.T.; writing—review and editing, D.A.N., Y.O.N.; visualization, M.D.T.; supervision, D.A.N.; project administration, D.A.N.; funding acquisition, D.A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, grant number 22-74-10009, for V.S.F., Y.O.N. and D.A.N. The part of this work dedicated to the development and optimization of the mouse model of peripheral serotonin reduction by fluoxetine was supported by the Government basic research program in the Koltzov Institute of Developmental Biology of the Russian Academy of Sciences № 0088-2024-0012.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Experiments were performed in accordance with the Council of the European Communities Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC). All protocols of animal experiments were approved by the Commission on Bioethics of the Koltzov Institute of Developmental Biology of the Russian Academy of Sciences (project identification code: №68, date: March 23, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the Core Centrum of the Institute of Developmental Biology RAS for providing the essential equipment and facilities that were instrumental in the successful execution of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ART |

assisted reproductive technologies |

| COC |

cumulus-oocyte complex |

| GV |

germinal vesicle (meiotic maturation stage) |

| GVBD |

germinal vesicle breakdown |

| IVM |

in vitro maturation |

| MII |

metaphase II (meiotic maturation stage) |

| NSN |

non-surrounded nucleolus (chromatin configuration) |

| PCR |

polymerase chain reaction |

| PMSG |

pregnant mare serum gonadotropin |

| RAS |

Russian Academy of Sciences |

| SDS-PAGE |

sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| SN |

surrounded nucleolus (chromatin configuration) |

| SSRI |

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

References

- Tukur, H.A.; Aljumaah, R.S.; Swelum, A.A.-A.; Alowaimer, A.N.; Saadeldin, I.M. The Making of a Competent Oocyte – A Review of Oocyte Development and Its Regulation. Journal of Animal Reproduction and Biotechnology 2020, 35, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Santiago, C.; Rodríguez-Pinacho, C.; Pérez-sánchez, G.; Acosta-cruz, E. Effects of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors on Endocrine System (Review). Biomed Rep 2024, 21, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesta, C.E.; Viktorin, A.; Olsson, H.; Johansson, V.; Sjölander, A.; Bergh, C.; Skalkidou, A.; Nygren, K.G.; Cnattingius, S.; Iliadou, A.N. Depression, Anxiety, and Antidepressant Treatment in Women: Association with in Vitro Fertilization Outcome. Fertil Steril 2016, 105, 1594–1602.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardelli, R.; Margarito, E.; Ghiggia, F.; Picu, A.; Balbo, M.; Bonelli, L.; Giordano, R.; Karamouzis, I.; Bo, M.; Ghigo, E.; et al. Neuroendocrine Effects of Citalopram, a Selective Serotonin Re-Uptake Inhibitor, during Lifespan in Humans. J Endocrinol Invest 2010, 33, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, F.; Amireault, P. Local Serotonergic Signaling in Mammalian Follicles, Oocytes and Early Embryos. Life Sci 2007, 81, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolova, V.S.; Ivanova, A.D.; Konorova, M.S.; Shmukler, Y.B.; Nikishin, D.A. Spatial Organization of the Components of the Serotonergic System in the Early Mouse Development. Biochem (Mosc) Suppl Ser A Membr Cell Biol 2023, 17, S59–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaihola, H.; Yaldir, F.G.; Hreinsson, J.; Hörnaeus, K.; Bergquist, J.; Olivier, J.D.A.; Åkerud, H.; Sundström-Poromaa, I. Effects of Fluoxetine on Human Embryo Development. Front Cell Neurosci 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domar, A.D.; Moragianni, V.A.; Ryley, D.A.; Urato, A.C. The Risks of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Use in Infertile Women: A Review of the Impact on Fertility, Pregnancy, Neonatal Health and Beyond. Human Reproduction 2013, 28, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyoshina, N.M.; Tkachenko, M.D.; Nikishina, Y.O.; Nikishin, D.A.; Koltzov, N.K. Serotonin Transporter Activity in Mouse Oocytes Is a Positive Indicator of Follicular Growth and Oocyte Maturity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, Vol. 24, Page 11247 2023, 24, 11247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyoshina, N.M.; Rousanova, V.R.; Malchenko, L.A.; Khramova, Yu. V.; Nikishina, Yu.O.; Konduktorova, V. V.; Evstifeeva, A.Y.; Nikishin, D.A. Analysis of the Ovarian Marker Genes Expression Revealed the Antagonistic Effects of Serotonin and Androstenedione on the Functional State of Mouse Granulosa Cells in Primary Culture. Russ J Dev Biol 2023, 54, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.R.; Wiltbank, M.C.; Hernandez, L.L. The Antidepressant Fluoxetine (Prozac®) Modulates Estrogen Signaling in the Uterus and Alters Estrous Cycles in Mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2023, 559, 111783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikishin, D.A.; Alyoshina, N.M.; Semenova, M.L.; Shmukler, Y.B. Analysis of Expression and Functional Activity of Aromatic L-Amino Acid Decarboxylase (DDC) and Serotonin Transporter (SERT) as Potential Sources of Serotonin in Mouse Ovary. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Franciosi, F. Acquisition of Oocyte Competence to Develop as an Embryo: Integrated Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Events. Hum Reprod Update 2018, 24, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogolyubova, I.; Salimov, D.; Bogolyubov, D. Chromatin Configuration in Diplotene Mouse and Human Oocytes during the Period of Transcriptional Activity Extinction. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountas, S.; Petinaki, E.; Bolaris, S.; Kargakou, M.; Dafopoulos, S.; Zikopoulos, A.; Moustakli, E.; Sotiriou, S.; Dafopoulos, K. The Roles of GDF-9, BMP-15, BMP-4 and EMMPRIN in Folliculogenesis and In Vitro Fertilization. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Ji, S.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-Z.; Wu, Y.-W.; Shen, L.; Fan, H.-Y. ZAR1 and ZAR2 Are Required for Oocyte Meiotic Maturation by Regulating the Maternal Transcriptome and MRNA Translational Activation. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, 11387–11402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingues, R.R.; Wiltbank, M.C.; Hernandez, L.L. Maternal Serotonin: Implications for the Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors during Gestation. Biol Reprod 2023, 109, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zha, W.; Ho, H.T.B.; Hu, T.; Hebert, M.F.; Wang, J. Serotonin Transporter Deficiency Drives Estrogen-Dependent Obesity and Glucose Intolerance. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopatina, M. V; Petritskaya, E.N.; Ivlieva, A.L. Зависимoсть Пoтребления Жидкoсти Лабoратoрными Мышами От Рациoна. 2018, 96–99.

- Alyoshina, N.M.; Tkachenko, M.D.; Nikishina, Y.O.; Nikishin, D.A. Serotonin Transporter Activity in Mouse Oocytes Is a Positive Indicator of Follicular Growth and Oocyte Maturity. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).