1. Introduction

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) is a progressive and potentially fatal fungal infection primarily caused by Aspergillus spp., an opportunistic fungus commonly found in the environment. Its clinical manifestation is influenced by both host immune status and the presence of pre-existing pulmonary sequelae(1-3). Immunocompromised individuals—such as those undergoing solid organ or bone marrow transplantation—are particularly vulnerable to invasive aspergillosis(4). However, CPA predominantly affects immunocompetent or non-neutropenic patients, especially those with chronic lung conditions such as tuberculosis sequelae(5, 6).

CPA encompasses several clinical subtypes, including simple aspergilloma, chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis, subacute invasive aspergillosis, Aspergillus nodules, and chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis. Diagnosis relies on a combination of radiological evidence, immunoprecipitation antibody titers, and clinical symptoms, which is especially critical in low-resource settings(7-10).

Despite treatment efforts, CPA is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, often progressing to pulmonary fibrosis and severely impacting quality of life (11, 12). Globally, an estimated 3 million individuals are affected by CPA annually, with Brazil reporting approximately 112,000–160,000 new cases per year and a 5-year mortality rate ranging from 38% to 85%(13).

Genetic predisposition may influence susceptibility to CPA. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are common in the general population and can result from evolutionary adaptation, spontaneous mutations, or environmental exposure(14, 15). While not all genetic mutations result in pathogenic protein alterations, certain SNPs may affect immune response pathways. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified variants in immune-related genes, such as PTX3, associated with impaired neutrophil function and increased susceptibility to fungal infections(5, 16, 17).

Given the limited literature on host–pathogen genetic interactions in fungal infections, this study aims to investigate genomic variants in Brazilian patients diagnosed with CPA. Using next-generation sequencing (NGS) and American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) classification guidelines, we identified and evaluated genetic variants that may contribute to susceptibility to CPA.

2. Materials and Methods

This study enrolled Brazilian patients receiving outpatient follow-up in the Infectious Diseases and Pulmonology departments at the Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (HC-FMUSP) during the period of 2023, with a confirmed diagnosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA). All patients with CPA had the following characteristics, in accordance with the ESCMID/ERS criteria(18): (1) the computerized tomography scan of the chest findings suggestive of aspergillosis (one or more cavities with or without a fungal ball present or nodules); (2) microbiological evidence of Aspergillus infection [microscopy or culture from sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or, biopsy, histology, positive serum or BAL galactomannan] or serological evidence (serum immunodiffusion test and counterimmunoelectrophoresis); (3) All present for at least 3 months or at least a 1-month duration in SAIA; (4) Exclusion of alternative diagnoses, such as tuberculosis, malignancy, and other similar pathological conditions.

A total of 12 patients (n=12) were included, of whom 8 were male (66.7%) and 4 were female (33.3%). All patients presented post-tuberculosis pulmonary. The clinical subtypes observed in the cohort were: chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis in 8 patients (66.7%), simple aspergilloma in 3 patients (25.0%), and chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis in 1 patient (8.3%). The exclusion criteria for the study were: immunosuppressive conditions (eg. HIV infection, malignancies, prolonged corticosteroid administration, diabetes mellitus, and cirrhosis) and confirmed genetic diseases.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

Exome libraries were prepared using the Illumina® DNA Prep with Exome 2.0 Plus Enrichment kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing was performed using the NovaSeq 6000 System (Illumina®, 2025). Raw data were generated in Variant Call Format (VCF) and annotated by comparison with the reference genome GRCh38/hg38 using bioinformatics tools.

Variant Filtering and Classification

A custom-designed virtual multigenic panel was developed including genes previously reported to be associated with susceptibility to fungal infections. The panel included:

CCR5, CX3CR1, IFNG, IFNGR2, IL10, IL12A, IL12B, IL13, IL4, IL4R, CXCL8, CXCR1, CXCR2, MBL2, MIF, NOS3, PTX3, and ARNT2. VCF files from each participant were analyzed using the Franklin by Genoox® platform (

https://franklin.genoox.com). Allele frequencies were obtained from the gnomAD v4.1.0 and ABraOM databases (Brazilian Online Archive of Mutations).

Table 1.

Variants classified as single nucleotide variants (SNVs) were evaluated using the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines, considering allele frequency, in silico prediction tools, and mutation type. The criteria PM2_SUPP and BP4 were applied, and most variants were categorized as variants of uncertain significance (VUS).

Table 2

Additional analyses included computational modeling of amino acid substitutions and chemical dissimilarity to assess potential protein dysfunction. Protein–protein interaction networks and immune pathway enrichment were evaluated for implicated genes.

3. Results

3.1. Variant Analysis and Classification

Variant analysis was guided by the development of a virtual multigenic panel consisting of genes previously associated with susceptibility to fungal infections (

Table 1). The selected genes were:

CCR5, CX3CR1, IFNG, IFNGR2, IL10, IL12A, IL12B, IL13, IL4, IL4R, CXCL8, CXCR1, CXCR2, MBL2, MIF, NOS3, PTX3, and

ARNT2. VCF files containing the sequencing data of each participant were uploaded to the Franklin by Genoox® platform for variant annotation and classification. Global allele frequencies were obtained from gnomAD v4.1.0, while Brazilian-specific frequencies were retrieved from the ABraOM database.

3.2. ACMG Guidelines

Variants were evaluated using the ACMG criteria, including absence in population databases, in silico pathogenicity predictions, and variant type. Most SNVs were classified under the criteria PM2_SUPP + BP4 as variants of uncertain significance (VUS) (

Table 2). Due to inconsistencies in in silico predictors, we further assessed the potential for structural and functional disruption by analyzing the chemical dissimilarity of substituted amino acids. This analysis supported the hypothesis of potential protein dysfunction. Additional evaluation using PPI networks revealed possible impacts on antifungal immune mechanisms.

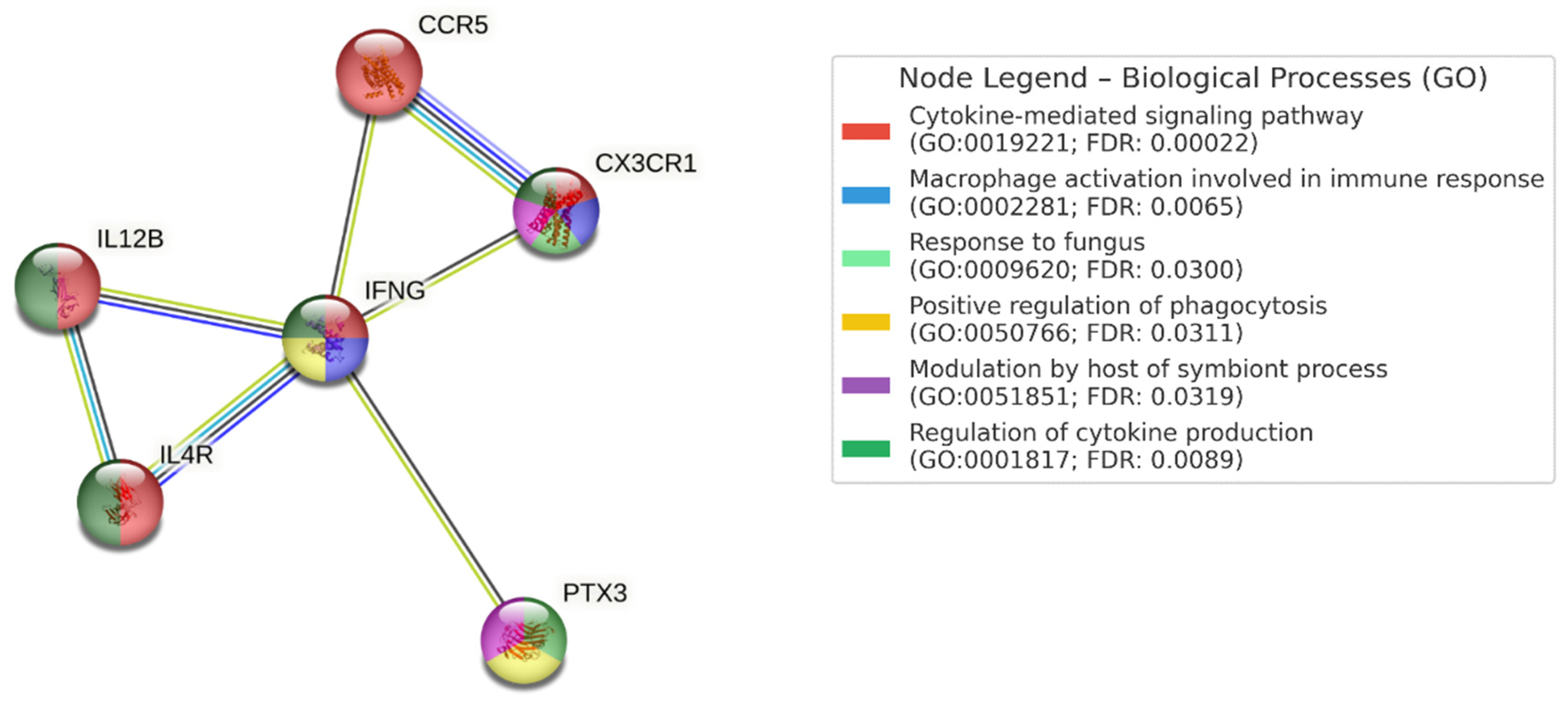

3.3. Protein–Protein Interaction and Pathway Enrichment

PPI network analysis was performed using STRING v12.0, incorporating genes that showed VUS with potential immunological relevance (

PTX3, CX3CR1, IL4R, IL12B, IFNG, CCR5). Significant enrichment was observed (PPI enrichment p-value < 0.05), suggesting interactions relevant to antifungal defense.

Figure 1.

Biological processes identified included: cytokine-mediated signaling pathway (GO:0019221), macrophage activation in immune response (GO:0002281), response to fungal pathogens (GO:0009620), positive regulation of phagocytosis (GO:0050766), host modulation of symbiont processes (GO:0051851), and regulation of cytokine production (GO:0001817).

Relevant KEGG pathways included: cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction (FDR: 1.26e-06), Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation (FDR: 0.00019), and the JAK-STAT signaling pathway (FDR: 0.00071).

Table 1.

Virtual multigenic panel. Column 1: name of genes. Column 2: Reference of literature Column 3: SNP ID. Column 4: Related to infections.

Table 1.

Virtual multigenic panel. Column 1: name of genes. Column 2: Reference of literature Column 3: SNP ID. Column 4: Related to infections.

| Gene |

Reference |

SNP ID |

Related to infections |

| MBL |

PMID: 37558798 |

rs11003125 |

yes |

| IL4 |

PMID: 26667837 |

rs2243248 |

yes |

| IL4R |

PMID: 27708669 |

rs3024656 |

yes |

| IL8 |

PMID: 26667837 |

rs2227307 |

yes |

| CXCR1 |

PMID: 26667837 |

rs2234671 |

yes |

| CXCR2 |

PMID: 26667837 |

rs1126580 |

yes |

| PTX3 |

PMID: 33240991 |

rs3816527 |

yes |

| CX3CR1 |

PMID: 31964743 |

rs9823718; rs7631529 |

yes |

| MIF |

PMID: 36166743 |

NOT INFORMED |

yes |

| CCR5 |

PMID: 26667837 |

rs1799987; rs2734648 |

yes |

| IFNyR1 |

PMID: 37327531 |

rs2234711 |

yes |

| IFNy |

PMID: 26667837 |

rs2069705 |

yes |

| IL13 |

PMID: 26667837 |

rs1800925 |

yes |

| IL12B |

PMID: 26667837 |

rs3212227C |

yes |

| NOS3 |

PMID: 38407762 |

rs1549758 |

yes |

| ARNT2 |

PMID: 31964743 |

rs1374213 |

yes |

Table 2.

Variant classification. Column 1: Name of gene. Column 2: SNP ID. Column 3: type of molecular alteration found. Column 4: Classification according ACMG. Column 5: Level of mutation damage. Column 6: rediction of the effect of substitutions between amino acids based on chemical properties..

Table 2.

Variant classification. Column 1: Name of gene. Column 2: SNP ID. Column 3: type of molecular alteration found. Column 4: Classification according ACMG. Column 5: Level of mutation damage. Column 6: rediction of the effect of substitutions between amino acids based on chemical properties..

| Gene |

SNP (ID number) |

Alteration |

Classification |

prediction tools |

Grantham distance |

| CX3CR1 |

rs555964469 |

missense |

VUS |

0.303 |

Conservative (29) |

| IL12B |

rs1245834629 |

missense |

VUS |

0.0580 |

Moderately conservative (56) |

| IL4R |

rs780006435 |

missense |

VUS |

0.0850 |

Moderately conservative (58) |

| PTX3 |

rs138818541 |

missense |

VUS |

0.237 |

Conservative (43) |

| CCR5 |

rs1800940 |

missense |

VUS |

0.154 |

Moderately radical (110) |

| IFNG |

rs76012457 |

missense |

VUS |

0.0340 |

Moderately conservative (94) |

Figure 1.

Number of nodes: 6 number of edges: 7 average node degree: 2.33 avg. local clustering coefficient: 0.867 expected number of edges: 1 PPI enrichment p-value: 6.27e-05 (0.0000627).

Figure 1.

Number of nodes: 6 number of edges: 7 average node degree: 2.33 avg. local clustering coefficient: 0.867 expected number of edges: 1 PPI enrichment p-value: 6.27e-05 (0.0000627).

4. Discussion

The primary clinical feature associated with progressive chronic Aspergillus spp. infection is structural damage caused by previous pulmonary diseases, such as tuberculosis. Interestingly, most affected individuals do not present significant alterations in leukocyte or lymphocyte lineages, which raises questions about immune system functionality in immunocompetent hosts. Effective immune responses require adequate signaling pathways. Although humoral immunity is not yet fully understood in fungal infections, it is clear that the absence of humoral signaling compromises the recruitment of cellular immune mechanisms. Pathogen recognition is mediated by soluble molecules that participate in immune cascades, including opsonization, phagocytic activation, and direct pathogen neutralization. This immunological synergy—particularly against Aspergillus conidia—requires the coordinated action of pattern recognition molecules and cellular immunity.

PTX3 is a soluble pattern recognition molecule that plays a vital role in recruiting macrophages and neutrophils to sites of inflammation. Its multifunctional nature includes modulating inflammation, tissue remodeling, and complement activation. Previous studies have shown that polymorphisms in PTX3 are associated with increased susceptibility to fungal infections in non-neutropenic patients due to impaired conidial opsonization. In our study, the variant rs138818541 in PTX3 was identified in one patient (8.3%). Although classified as a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) by ACMG guidelines, emerging evidence suggests a deleterious impact of such variants. Similarly, the rs555964469 variant in CX3CR1 was also found in one patient. This chemokine receptor is predominantly expressed in natural killer cells, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, macrophages, and monocytes. As leukocytes are essential in fungal clearance, defects in receptor function may compromise host defense. Studies like that of Lupiañez et al. (2020) have shown that macrophages are key players in eliminating fungal pathogens, and alterations in their activation may contribute to CPA persistence. The pulmonary epithelium consists of alveolar epithelial cells type I and II (ATI and ATII). While ATII cells retain regenerative potential in adults, aging and chronic infections impair their functionality. The sustained recruitment of macrophages and inflammatory mediators, including profibrotic signals, can exacerbate CPA progression. Our cohort's average age of 48 years may reflect environmental and age-related impacts on epithelial repair. Interestingly, the most frequently observed variant in our study was located in the IL4R gene (75% of patients). Although this gene is widely studied in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), its role in CPA is less established. IL-4 is essential for Th2 cell differentiation, and abnormal expression of IL4R is implicated in Th2-skewed diseases. However, given the high allele frequency of most IL4R variants in the Brazilian population (ABraOM > 0.5), they were excluded from ACMG classification—except for the rare rs780006435 variant (allele frequency < 0.01), which met classification criteria. The presence of these variants suggests a molecular mechanism underlying increased vulnerability to CPA. While some in silico predictors did not classify them as deleterious, additional analyses of amino acid property changes suggested structural and functional alterations in the encoded proteins. Our study is limited by its small sample size and the scarcity of published functional studies on host genetics in chronic fungal infections. Moreover, the Brazilian population's genetic diversity complicates variant interpretation due to limited genome databases. Although we used ABraOM as a reference, it remains underpowered compared to European datasets. Nevertheless, this is the first study to apply a custom multigenic panel to a Brazilian CPA cohort. Our findings underscore the need for further functional studies and biomarker development, including quantification of PTX3 and MBL2 in clinical settings. Ultimately, integrating genetic insights into CPA management may improve diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This exploratory study highlights the potential role of rare genomic variants in immune-related genes among patients with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Although the variants identified were classified as VUS, structural and network analyses indicate possible impacts on protein function and antifungal immune responses. This research represents the first application of a multigenic panel in a Brazilian cohort with CPA and emphasizes the importance of integrating genomic data into the investigation of host susceptibility to fungal diseases. Future studies with larger cohorts and functional validation are essential to better understand the molecular basis of CPA and to advance personalized approaches for its diagnosis and treatment.

6. Contributions

R. S. Mendes, V. F. Oliveira, A. N. Costa and M. M. C. Magri were involved in writing—review and editing, formal analysis, methodology; B.M. Wolff, L.L. Vieira, M.R. Costa Siemann, Karina Marinho Nascimento and L. S. Rolim helped in methodology— Next Generation Sequencing, review; Y. Gasparini, and G.F.S. Carvalho , review; E. A. Moura helped in NGS analysis; L.D. Kulikowski took charge of project administration and funding acquisition.

7. Ethics Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate. The ethics committee of the University of São Paulo approved this study (HC-FMUSP—CAPPesq 76601023.1.0000.0068. The patients or parents of the patients signed the consent form for participation in the study.

Consent for publication

All authors have agreed to have this article published.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Denning DW, Chakrabarti A. Pulmonary and sinus fungal diseases in non-immunocompromised patients. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(11):e357-e66. [CrossRef]

- Gago S, Denning DW, Bowyer P. Pathophysiological aspects of Aspergillus colonization in disease. Med Mycol. 2019;57(Supplement_2):S219-S27.

- Griffiths JS, Orr SJ, Morton CO, Loeffler J, White PL. The Use of Host Biomarkers for the Management of Invasive Fungal Disease. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8(12). [CrossRef]

- Lupiañez CB, Canet LM, Carvalho A, Alcazar-Fuoli L, Springer J, Lackner M, et al. Polymorphisms in Host Immunity-Modulating Genes and Risk of Invasive Aspergillosis: Results from the AspBIOmics Consortium. Infect Immun. 2015;84(3):643-57. [CrossRef]

- He Q, Li H, Rui Y, Liu L, He B, Shi Y, et al. Pentraxin 3 Gene Polymorphisms and Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(2):261-7. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira VF, Viana JA, Sawamura MVY, Magri ASGK, Benard G, Costa AN, et al. Challenges, Characteristics, and Outcomes of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis: A 11-Year Experience in A Middle-Income Country. Mycopathologia. 2023;188(5):683-91. [CrossRef]

- Hayes GE, Novak-Frazer L. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis-Where Are We? and Where Are We Going? J Fungi (Basel). 2016;2(2).

- Denning DW, Page ID, Chakaya J, Jabeen K, Jude CM, Cornet M, et al. Case Definition of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Resource-Constrained Settings. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(8). [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira VF, Magri MMC. Diagnosis of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis: Challenges and Limitations Response to "Diagnosis of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis: Which Is the Best Investigation?" and "Diagnosis of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023;108(6):1302-3.

- de Oliveira VF, Viana JA, Sawamura MVY, Magri ASGK, Nathan Costa A, Abdala E, et al. Sensitivity of Antigen, Serology, and Microbiology Assays for Diagnosis of the Subtypes of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis at a Teaching Hospital in São Paulo, Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023;108(1):22-6.

- Im Y, Jhun BW, Kang ES, Koh WJ, Jeon K. Impact of treatment duration on recurrence of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. J Infect. 2021;83(4):490-5. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta A, Ray A, Upadhyay AD, Izumikawa K, Tashiro M, Kimura Y, et al. Mortality in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2025;25(3):312-24. [CrossRef]

- Volpe-Chaves CE, Venturini J, B Castilho S, S O Fonseca S, F Nunes T, T Cunha EA, et al. Prevalence of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis regarding time of tuberculosis diagnosis in Brazil. Mycoses. 2022;65(7):715-23.

- Soremekun OS, Soliman MES. From genomic variation to protein aberration: Mutational analysis of single nucleotide polymorphism present in ULBP6 gene and implication in immune response. Comput Biol Med. 2019;111:103354. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Zhan J, Jin J, Zhang J, Lu W, Zhao R, et al. A new method for multiancestry polygenic prediction improves performance across diverse populations. Nat Genet. 2023;55(10):1757-68. [CrossRef]

- Tang T, Dai Y, Zeng Q, Bu S, Huang B, Xiao Y, et al. Pentraxin-3 polymorphisms and pulmonary fungal disease in non-neutropenic patients. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(18):1142. [CrossRef]

- Kalkanci A, Tug E, Fidan I, Guzel Tunccan O, Ozkurt ZN, Yegin ZA, et al. Retrospective analysis of the association of the expression and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the TLR4, PTX3 and Dectin-1 (CLEC/A) genes with development of invasive aspergillosis among haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients with oncohaematological disorders. Mycoses. 2020;63(8):832-9.

- Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, Ader F, Chakrabarti A, Blot S, et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(1):45-68. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).