1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a leading cause of death by infections worldwide and most important pathogen related to hospital-acquired infections including bloodstream infections [

1]. Treatment of

S. aureus infections is difficult due to widespread antibiotic resistance, also related to sessile life in biofilms. Thus, formation of biofilm is an important way in which

S. aureus maintains an infection. Staphylococcal biofilms can be formed on abiotic material of indwelling medical devices, as well as on tissue surfaces, such as on heart valves in the case of endocarditis [

2]. The main role of biofilm formation during infection is to protect the bacteria from phagocyte attacks [

3].

Biofilm formation develops in three main stages: adhesion, maturation/proliferation, and detachment/dispersal. Initial attachment or adhesion occurs to human matrix proteins via cell-wall anchored and other surface proteins, many of which belong to the MSCRAMM family i.e. microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules [

4]. In the second stage, for example during infection, cells divide and produce a biofilm matrix which connects cells. In

S. aureus, the matrix consists of the PIA/PNAG exopolysaccharide, extracellular DNA, teichoic acids and proteins [

5].

Iminosugars are natural or synthetic sugar analogues with an amino function in place of the endocyclic oxygen of the corresponding carbohydrate [

6]. Their mechanism of activity is based on inhibition of the common carbohydrate processing enzymes like glycosidases and glycosyltransferases. A couple of the iminosugars are licensed and marketed as medicinal products to treat type 2 diabetes, Gaucher disease and Fabry disease [

7]. Several other therapeutic applications of the iminosugars have been proposed and evaluated but without significant outcomes. Antimicrobial properties of the iminosugars have also been studied and indeed, they displayed antiviral [

8] and antibacterial inhibitory activities against most prominent bacterial pathogens like as

P. aeruginosa or

S. aureus [

9,

10]. It appeared also that some iminosugars can inhibit biofilm production by bacteria. The most prominent example of this activity is inhibition of

Streptococcus mutans adherence to dental surfaces by natural 1-deoxynojirimycin from mulberry leaves [

11].

Our group studied both inhibitory and anti-biofilm properties of several iminosugars against

P. aeruginosa and found that the observed compounds inhibited synthesis of the early biofilm but possessed no growth inhibitory properties [

12]. It appeared later that one of these iminosugars, namely beta-1-C-propyl-1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-L-arabinitol (PDIA) was active against 30 clinical strains of the most important human pathogens, both Gram-positive and -negative, and again it showed no growth inhibitory but strong early- biofilm inhibitory properties [

13]. Recently, the ability of PDIA to interfere with experimental subcutaneous

S. aureus infection in mice was demonstrated by us also

in vivo [

14].

The aim of the study was to elucidate the molecular mechanisms through which PDIA iminosugar affects biofilm formation in a biofilm-producing S. aureus strain.

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of Biofilm Structure by SEM

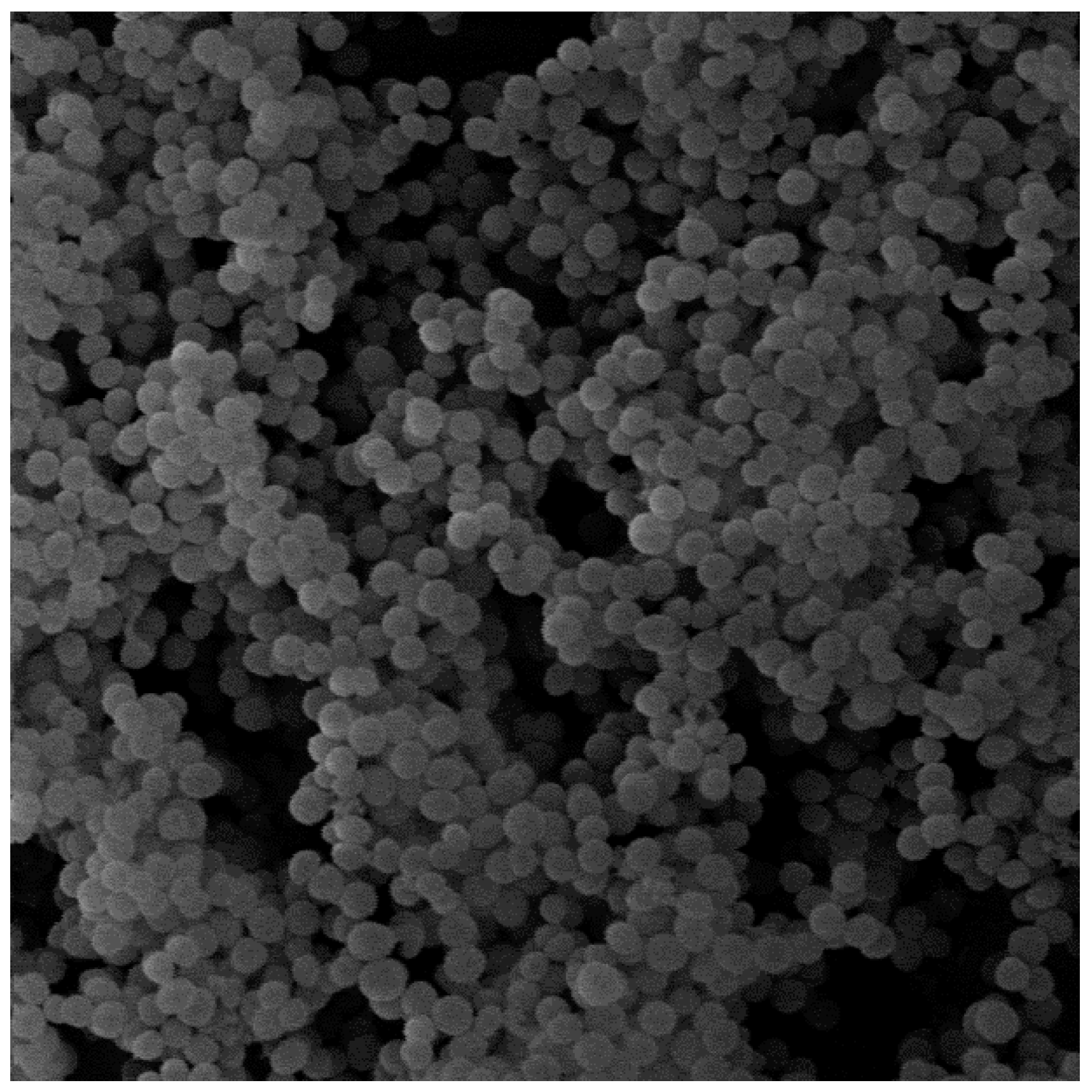

Analysis of the biofilm morphology of

S. aureus 48 by SEM (scanning electron microscopy) confirmed its ability to form dense and well-organized structures (

Figure 1). The image obtained in the microscope also confirms the results of our previous research on the ability of this strain to form a biofilm.

2.2. RNA-Seq

A total of twelve samples (six per control and six per experimental group) were subjected to RNA-seq. Illumina sequencing yielded approximately 588.39 million raw reads for the control group and 301.77 million raw reads for the experimental group. The average yield was 7.21 and 7.59 giga-bases for the control and experimental groups, respectively. A phred score Q30 of 94.48 % was achieved for the control group, while this value reached 92.18 % for the experimental group. The established type of strain S. aureus subsp. aureus NCTC 8325 (NCBI RefSeq Assembly GCF_000013425.1) was used as the reference genome in this study. After eliminating low-quality reads with multiple N, reads shorter than 20 bp, and removing sequences encoding rRNA, a total of 293.92 million (142.92 million raw reads for the control group and 150.36 million raw reads for the experimental group) qualified mRNA sequence reads were mapped to the S. staphylococcus genome. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified at two time points (24 and 48 hours) to reveal transcriptomic differences between the iminosugar-exposed and control groups at p ≤ 0.05.

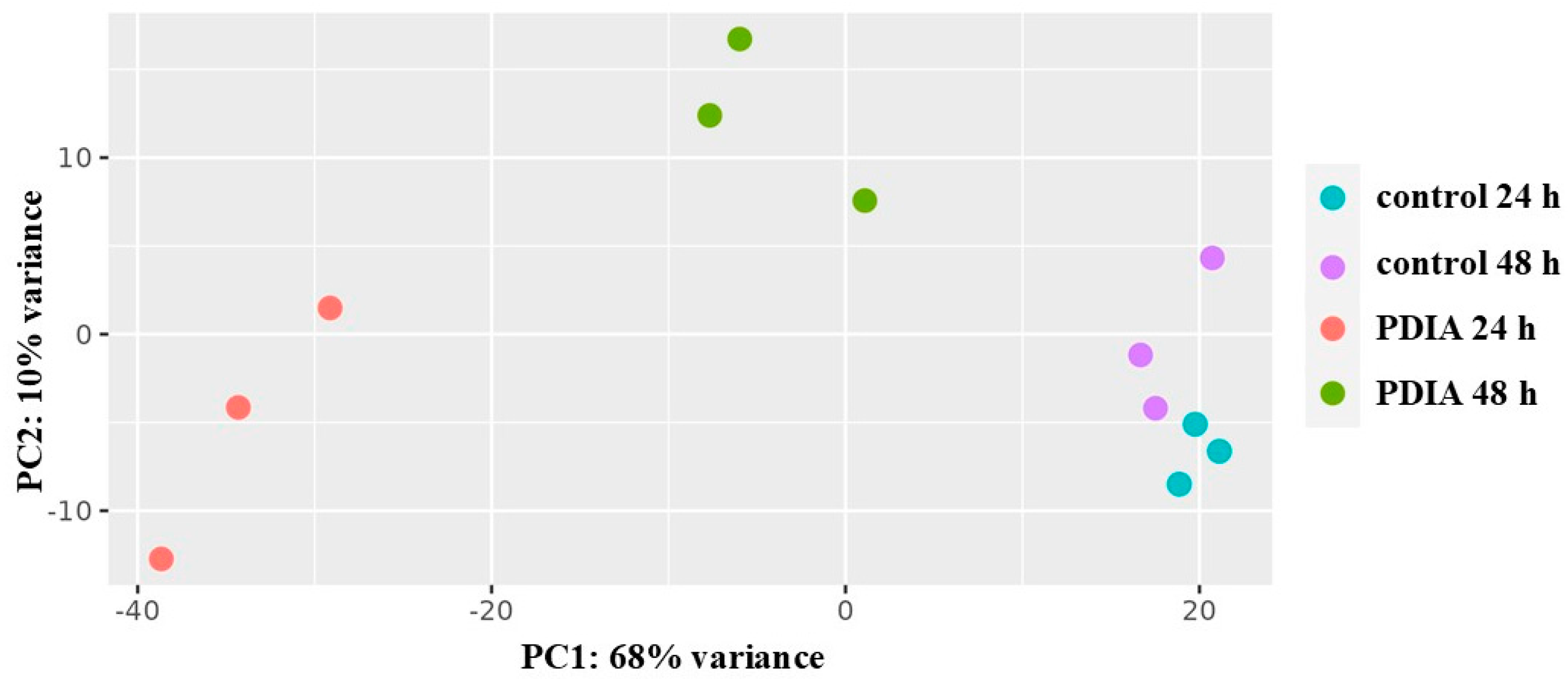

First, principal component analysis (PCA) was used to visualize the global differences in gene expression between all samples (

Figure 2). It was found that the control samples were grouped independently of the maturity of the biofilm. The samples exposed to PDIA and collected at different times were grouped independently. It is worth noting that PDIA samples representing the mature biofilm were closer to the control samples than the samples collected at 24 hours.

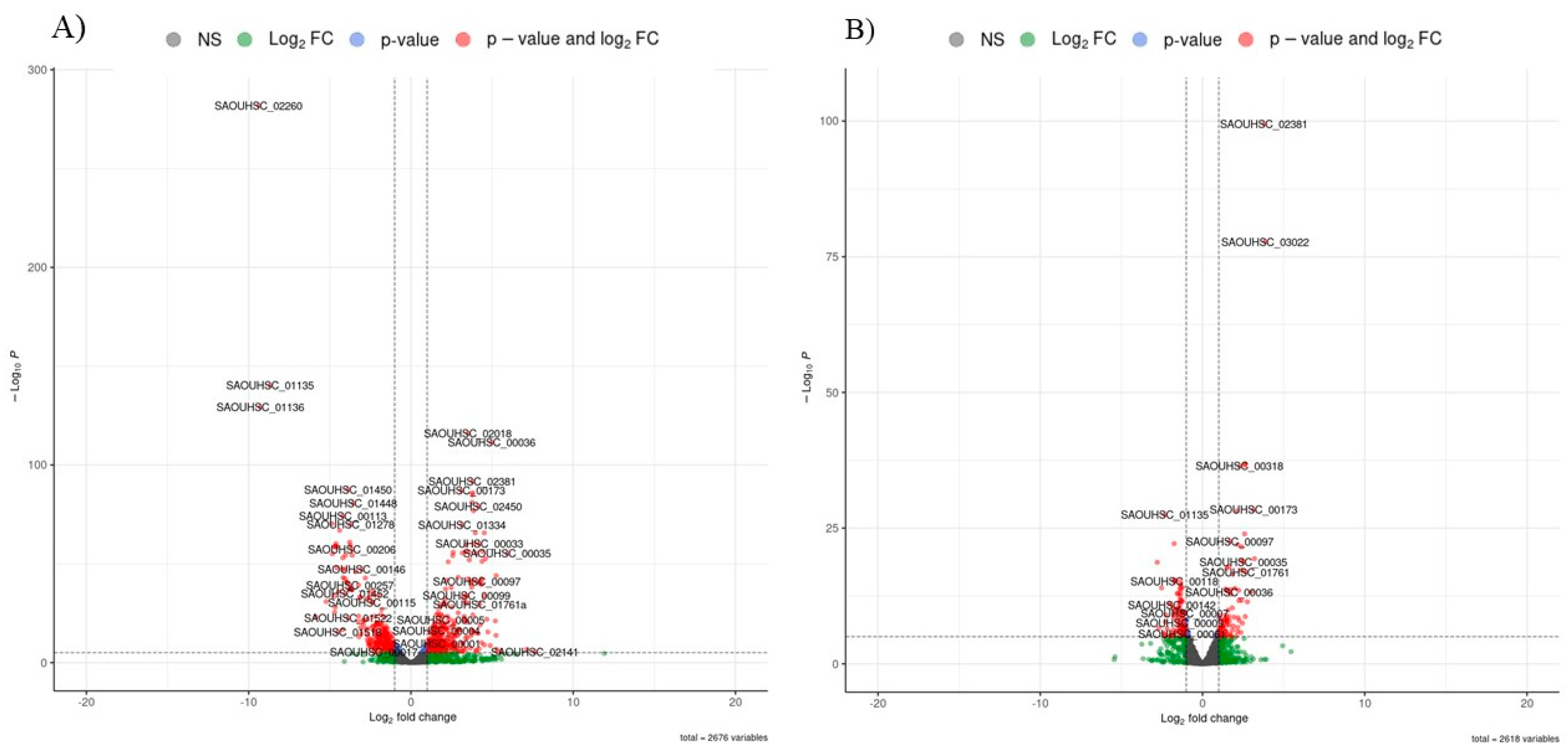

In early-biofilm, 1,266 downregulated DEGs were identified, of which 716 were significantly downregulated (

p <0.05). The results showed that at this stage of biofilm growth, 1,397 genes were upregulated and 767 DEGs were significantly upregulated (

p <0.05). In mature biofilm, only 1,243 DEGs were identified, of which 316 were significantly downregulated (

p <0.05). At this stage, 1,353 upregulated DEGs were identified, among them 289 DEGs showed significant upregulation (

p <0.05). A volcano map was used to visualize the overall distribution of DEGs in both groups (

Figure 3).

The genes that were statistically significantly downregulated or upregulated in response to PDIA treatment in early biofilm are listed in

Table 1 and

Table 2 respectively. Many of the down-regulated genes are from bacteriophages (11 genes) and are responsible for the processes of bacterial cell lysis, and some genes responsible for cell wall degradation are also down-regulated. All bacteriophage genes are located next to each other on the chromosome (from SAOUHSC_01519 to SAOUHSC_01539). Genes that are responsible for the degradation of cell structures are located in the immediate vicinity of their functional partners from the phage. All these genes show a similar degree of down-regulation (log2_Estimated_FoldChange from 3.72 to 4.86, mean value of 4.36).

Among the 25 genes that showed the highest upregulation, 11 were genes responsible for tRNA synthesis. The degree of upregulation was relatively variable, as the highest fold change was 11.92 (tRNA-Gly) and the lowest was 4.35 (tRNA-Tyr). The second group of genes were those related to bacteriophages. Most of them represented bacteriophage phiETA, and all of them were upregulated more than four times. Other genes that showed upregulation were responsible for the phosphotransferase system (PTS) (SAOUHSC_02449, SAOUHSC_02450, SAOUHSC_02452) and membrane function (SAOUHSC_01761a and SAOUHSC_02873).

The genes that were statistically significantly downregulated or upregulated in response to PDIA treatment in mature biofilm are listed in

Table 3 and

Table 4, respectively. Most of the genes that were downregulated in mature biofilm are the same as for early biofilm. Among the phage-derived genes, there were two genes that were downregulated in early-biofilm, but not in mature biofilm (SAOUHSC_01519 and SAOUHSC_01520). Genes responsible for the degradation of cell structures were also downregulated at 48 hours. However, the degree of regulation was lower than in early biofilm (log2_Estimated_FoldChange of 1.76 to 2.70, mean value of 2.17). Genes downregulated in mature biofilm included those encoding formate C-acetyltransferase (pflB, SAOUHSC_00187) and pyruvate formate lyase 1 activating enzyme (pflA, SAOUHSC_00188). Both showed a relatively high fold change – 2.53 and 2.79, respectively. The genes that showed the strongest upregulation in mature biofilm were the genes encoding azoreductase (SAOUHSC_00173), which was 3.14-fold higher than in the control group, and the gene encoding acylCoA:acetate/3-ketoacid CoA transferase (SAOUHSC_00199) showed upregulation at the 3.01 level.

Among the 25 most upregulated genes were seven representing the phosphotransferase system (PTS), which is required for carbohydrate uptake and control of carbon metabolism. These genes, encoding beta-galactosidase, transporter subunit IIBC, tagatose-1,6-diphosphate aldolase and kinase, and galactose-6-phosphate isomerase, were located sequentially on the chromosome (SAOUHSC_02449-SAOUHSC_02455). In contrast to early biofilm, the genes belonging to the PTS showed a lower fold change value, which was not higher than 2.63 (SAOUHSC_02450). For the mature biofilm, this value was about 4.0. In contrast to early biofilm, there were no tRNA-encoding genes among the most upregulated genes after 48 hours.

2.3. GO Term Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

The analysis of the functional enrichment of DEGs between the control group and the PDIA-treated groups was based on GO (Gene Ontology) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) databases. According to the GO functions, all DEGs were divided into three categories: biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC) and molecular functions (MF). The enrichment analysis (p≤ 0.05) in early biofilm characterized the GO terms as follows (Fig. S1). The BP-related DEGs (427 GO terms) were involved in metabolic (52.6%) and cellular processes (47.4%). The CC-related DEGs (36 GO terms) were involved in the cellular anatomical entity (72.7%) and protein containing content (27.3%). The MF-related DEGs (238 GO terms) were mainly responsible for transporter activity (42.9 %), catalytic activity (28.6 %), structural molecule activity (14.3 %) and ATP-dependent activity (14.3 %).

Whereas the enrichment analysis (p≤ 0.05) of mature biofilm characterized GO terms as follows (

Figure S1). The BP-related DEGs (306 GO terms) were involved in metabolic (52.6%) and cellular processes (47.4%). The CC-related DEGs (31 GO terms) were involved in cellular anatomical entity (72.7%) and protein containing content (27.3%). The MF-related DEGs (172 GO terms) were mainly responsible for transporter activity (42.9 %), catalytic activity (28.6 %), structural molecule activity (14.3 %) and ATP-dependent activity (14.3 %).

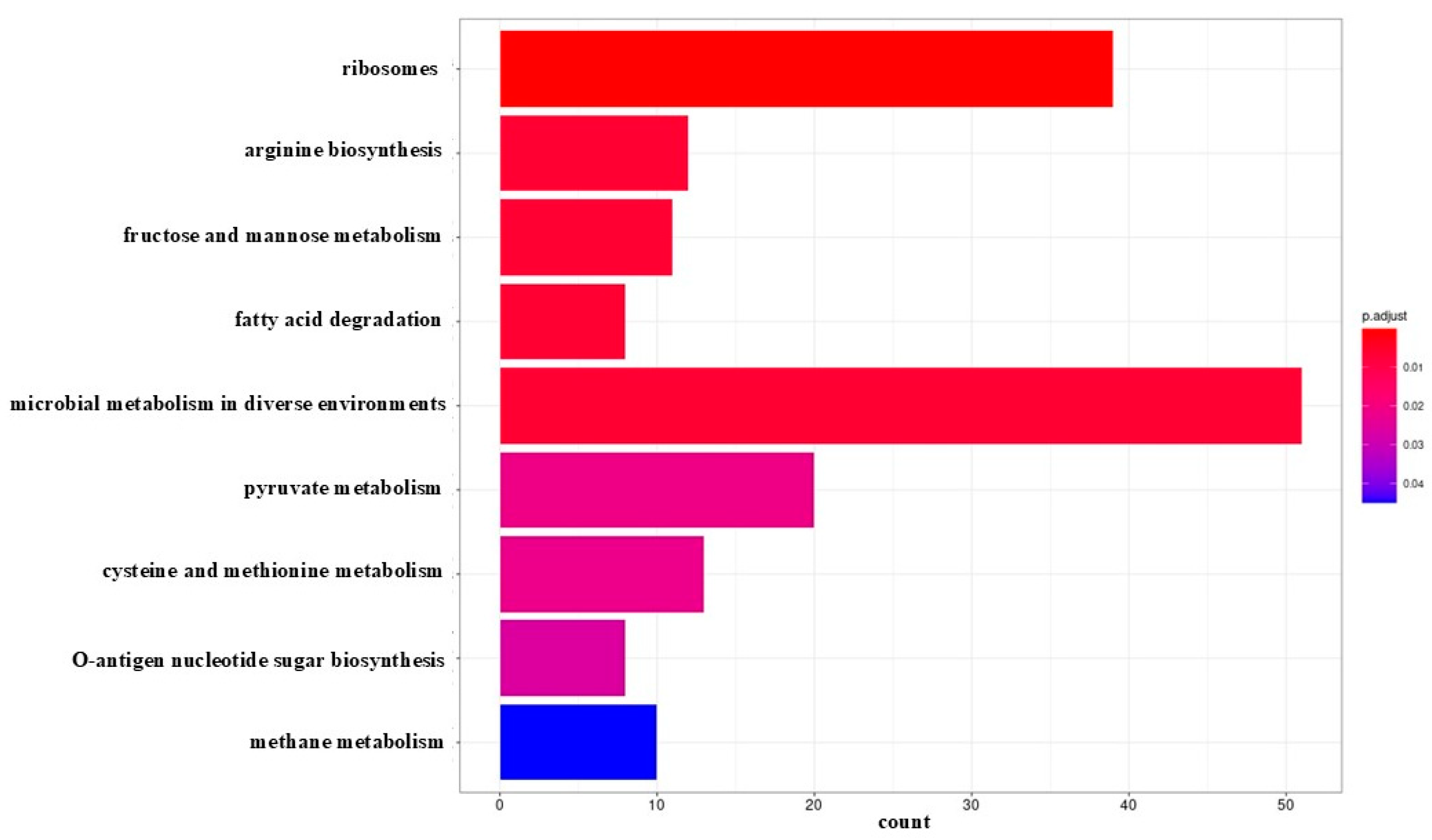

No significant metabolic pathway was identified for early biofilm. The results of KEGG analysis showed that DEGs identified in mature biofilm (

Figure 4) were significantly enriched in microbial metabolism in different environments, ribosomes, pyruvate metabolism, cysteine and methionine metabolism, arginine biosynthesis, fructose and mannose metabolism, methane metabolism, fatty acid degradation and O-antigen nucleotide sugar biosynthesis. Most DEGs (39) with relatively high probability, defined by the adjusted p-value, were assigned to the ribosomal pathway. The highest number of DEGs (51) was identified in the microbial metabolism pathway in different environments.

3. Discussion

Our previous studies on iminosugars and especially on PDIA compound demonstrated their inhibitory activity directed toward early biofilm formation without any activity against bacterial growth of a wide variety of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria pathogenic for humans [

12,

13]. The antibiofilm activity of PDIA was effective also

in vivo as shown on murine model of the staphylococcal subcutaneous infection [

14]. However, a molecular mechanism of the antibiofilm activity of PDIA remained unknown.

Studies on iminosugars interactions with enzymes revealed that iminosugars are among the most important glycomimetics reported to date due to their powerful activities as inhibitors of a wide variety of glycosidases and glycosyltransferases [

15]. Also, galactose-type iminosugars were reported as inhibitors of galactosylransferases [

16]. It had been demonstrated also that glucose-mimicking iminosugars of known antiviral activity inhibit isolated glycoprotein and glycolipid processing enzymes in virus infected cells [

17].

More recently, new natural iminosugars with strong antibiofilm activity were obtained from probiotic strain of

Lactobacillus paragasseri MJM60645, which was isolated from the human oral cavity. These compounds showed strong inhibitory activities against

S. mutans biofilm formation but did not show bactericidal activities against

S. mutans. One of these structures strongly downregulated expression levels of genes related to biofilm formation in

S. mutans [

18].

We have demonstrated here that PDIA effects on

S. aureus genes were broader and influenced many genes coding for metabolism and ribosomes. The ranking of the most significant down-regulated genes after 24-hour exposure to PDIA shows that they predominantly coded for both synthesis and lysis of the peptidoglycan. The peptidoglycan of the bacterial cell wall undergoes a permanent turnover during cell growth and differentiation. In

S. aureus, the major peptidoglycan hydrolase Atl is required for accurate cell division, daughter cell separation and autolysis [

19]. What is important, Atl is associated with autolysis processes, e.g. during biofilm formation. Similar activity is attributed to soluble lytic transglycosylase SLT located in

S. aureus on prophage region [

20]. Moreover, PDIA causes downregulation of bacteriophage genomes encoded enzymes named holins which among others, possess predominantly lytic activities, and thus contribute to biofilm formation [

21]. It appeared that holin proteins (CidA, probably in conjunction with LrgA) temporally control the timing of cell lysis and DNA release during biofilm development. In our study,

CidA showed significantly lower expression (log2_Estimated_FoldChange 2.47) in early biofilm treated with PDIA, confirming the possible role of this protein as a regulator in cell lysis processes. In view of these observations, several authors proposed to use isolated holins or even artificial phages to control infections [

22,

23].

Significant up-regulation of genes under influence of PDIA in 24 hours was mostly directed toward many tRNA genes.

S. aureus has a large tRNA cluster which contains 27 tRNA genes immediately 3' to an rRNA operon. Three of the tRNA genes in this

S. aureus cluster code for special tRNAs used in the synthesis of peptidoglycan [

24].

These observations may suggest that in 24 hours, PDIA induces increased tRNA synthesis and phosphotransferase system (PTS). Moreover, different phage genes are also overexpressed while others show down-expression. Most probably PDIA interacts differently with various phage genes, which leads to dysregulation of the peptidoglycan and generally cell wall synthesis which impairs also biofilm formation.

In the later phase of growth, in 48 hours when biofilm is matured, the bacterial cells under influence of PDIA increase synthesis of proteins involved in carbohydrate metabolism. On the other hand, prophage genes are downregulated. Differences in genes expression between control culture and PDIA-treated one are less prominent.

It is of interest that PDIA, at least at the used concentration, does not phenotypically impair S. aureus cell division, although staphylococcal cells under influence of PDIA may have alterations in their cell wall structure. We have not tested such a possibility, but we may speculate that an in vivo curative effect of PDIA on staphylococcal infection may be related not only to inhibition of biofilm formation, but also depressed production of virulence factors like as delta-hemolysin.

The weak point of our studies is that the only one concentration of PDIA has been tested against one clinically- relevant S. aureus with strong biofilm production. Still, the obtained results are highly suggestive for a PDIA activity directed toward bacterial and phage genome genes involved in coding for synthesis of proteins and polysaccharide macromolecules responsible for building cell wall and biofilm formation.

The obtained evidence complements the knowledge of the response of S. aureus to PDIA iminosugar, providing, together with phenotypic data and in vivo observations, a basis for development of highly effective inhibitor for elimination of S. aureus from medical devices surfaces and/or the treatment of the staphylococcal infections.

4. Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strain and Growth Conditions

Strain of

S. aureus 48 was chosen for the experiment based on its demonstrated high biofilm-forming proficiency and the biofilm susceptibility to the inhibitory properties of PDIA iminosugar [

13]. This strain is an integral component of the bacterial strains’ repository at the Department of Microbiology, Jagiellonian University Medical College. It was isolated from a patient suffering from chronic otitis media and its taxonomic identity was verified through mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS Biotyper, Bruker Scientific LLC, Billerica, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's guidelines.

Bacterial inoculum was prepared from the frozen pure culture by incubation of the glass beads coated with bacteria in 10 mL of TSB broth (Beckton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes NJ, USA) and incubation in 37 ◦C for 24 h. Then, to ensure the purity of the strain, 10 µL aliquots of the culture was streaked over surfaces of Columbia Agar (Biomaxima) and incubated as before. Three passages were made in the same manner to obtain bacterial populations of high viability. Finally, standardized bacterial suspension was made by transferring 1 µL of the 24-h broth culture to 9 mL of saline, vigorous mixing, and adjusting optical density to 0.5 of McFarland scale using a densitometer. This density was adjusted to approximately 1.0 × 107 CFU/mL, as previously controlled with a standard serial dilution method. Such a bacterial stock suspension was used on biofilm production experiments.

4.2. Biofilm Assay on Polystyrene Plate by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

In order to confirm the high biofilm-forming ability of the tested S. aureus 48 strain, we analyzed the morphology of the 48-hour biofilm using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). For this purpose, the glass plates (1 mm thick and 9 mm in diameter) were sterilized and placed into the well of 12-well plate for biofilm formation. Aliquots (1 mL) of bacteria cell suspensions were seeded into a well. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 48 hours and then gently washed three times with PBS to remove non-adherent bacteria. The adherent bacteria were fixed and dehydrated. After being fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 3 hours at 4°C, the surface was rinsed three times with PBS. The sample was dehydrated through 50% ethanol for 10 minutes each at room temperature. After critical-point drying and 1200 bar pressure at 40°C, the sample was examined using SEM (Jeol JSM-5410). To ensure reproducibility of results and exclude technical artifacts, SEM analysis was carried out in 5 replicates.

4.3. Iminosugar

The iminosugar derivative under investigation (PDIA beta-1-C-propyl-1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-L-arabinitol) was synthesized at the Institute of Organic and Analytical Chemistry, University of Orleans, France. Our prior research detailed its chemical structure [

13]. In the experiments, a solution of iminosugar at a concentration of 0.9 mM was employed.

4.4. Experimental Design

The effect of PDIA on the production of early (24 h) and mature (48 h) biofilm by S. aureus 48 strain was assessed using a 96-well plate model. Wells were filled with 20 µL of freshly prepared suspension of the tested S. aureus 48 strain containing 1 × 107 CFU/mL and 180 µL of TSB broth (Becton Dickinson). Six wells were used for biofilm formation under the influence of the PDIA (experimental group), six wells for biofilm formation in control group, and next two wells for measuring the number of viable bacteria.

The plates were incubated at 37°C under aerobic conditions for 4 h to allow initial adhesion. In the next step, 180 µL of the bacterial culture was pipetted out of each experimental well and 180 µL of the PDIA at a final concentration of 0.9 mM was added. In the control wells, an equivalent volume of fresh TSB medium without PDIA was added. The plates were gently rotated to distribute the iminosugar and incubated for 24 h at 37◦C in aerobic conditions. For RNA isolation the early biofilm was carefully scraped from the well surface using a sterile cell scraper and transferred into microcentrifuge tubes containing 500 µL of RNAlater (QIAGEN, Austin, USA). The samples were then vortexed briefly to resuspend the biofilm.

The effect of PDIA on mature biofilm was assessed using the same methodology. However, prior to PDIA treatment, bacterial cultures were incubated for 24 h to allow biofilm maturation. PDIA at 0.9 mM was then added, and biofilm samples for RNA isolation were collected at 48 h post-inoculation.

4.5. RNA Isolation

Total RNA from approximately 25 mg of S. aureus bacterial culture was isolated using Bead-Beat Total RNA Mini (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland). To lyse cells, 790 µl of fenozol supplemented with 10 µl of lysostaphin solution (15 U/µl) was added, mixed by pipetting and transferred into bead beating tube. Samples were homogenised at maximum speed in 20s on/60s off intervals for 3 min total (Uniequip, Planegg, Germany). During the rest period samples were cooled on ice. Next, samples were incubated for 5 min at 50 C, after which 200 µl of chloroform was added, mixed and left for 3 min at room temperature. Subsequently, samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 12 000 rpm. Supernatant was then transferred into a new tube, mixed with 250 µl of isopropanol, transferred onto a minicolumn, and centrifuged for 1 min at 12 000 rpm. After three washing steps with A1 wash solution, minicolumn was left to dry and RNA was eluted with 60 µl of RNAse-free water. The content of RNA was measured with Qubit 3 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA purity was additionally assessed with Nanodrop 8000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA integrity was evaluated using Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Until subsequent analysis, the isolated RNA was kept in -80 C.

4.6. Sequencing

Sequencing was carried out by Macrogen Europe following TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Reference Guide (1000000040499 v00). rRNA was depleted with NEBNext rRNA Depletion (Bacteria). TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Gold Kit was used to prepare libraries. Sequencing was conducted using Hiseq 2500 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) in pair-end mode. Raw data was deposited in NCBI SRA database under BioProject nr PRJNA987442.

4.7. Data Analysis

The first step of the analysis involved adapter trimming using Cutadapt [

25]. Filtering was performed using standard parameters, using a quality threshold of q = 25 and a minimum read length of m = 20. Quality reports for the sequencing data were generated with FastQC. Next, the reads were mapped to the ASM1342v1 reference genome of

S. aureus (NCBI RefSeq assembly GCF_000013425.1) using Hisat2 [

26]. The mapping process was performed with the --rna-strandness RF option to account for strand-specific RNA libraries. Following alignment, the read counts mapped to individual genes were quantified using HTSeq [

27], with the --stranded=reverse option to account for the reverse strand-specific nature of the data. Only genes with a cumulative total of at least three mapped reads across all samples were included in the analysis. Gene annotations were assigned based on the corresponding feature description file (feature_table.txt) for the

S. aureus genome. Additionally, InterProScan [

28] was employed to retrieve Gene Ontology (GO) identifiers for the analyzed genes. To identify differentially expressed genes between defined comparisons, the final results were processed in R using the DESeq2 package [

29] (Benjamin-Hochberg padj < 0.05). Enriched GO terms were identified using the topGO package [

30]. Finally, biological pathways for statistically significant genes with EntrezID identifiers were determined using the clusterProfiler package [

31] and the KEGG database [

32].

5. Conclusions

Iminosugar PDIA causes multiple changes in gene expression in S. aureus cells that explain its inhibitory effect on biofilm production. In 24 hours, increased tRNA synthesis is observed and genes coding for phosphotransferase system (PTS) are activated. At the same time some bacteriophage genes are overexpressed and others depressed. Most probably, PDIA causes deregulation of genes involved in synthesis and function of the staphylococcal cell wall. Increased tRNA synthesis may represent repair mechanisms by which peptidoglycan synthesis is accelerated. In 48 hours, the bacterial cell under influence of PDIA tried to save its cell wall structure by increasing synthesis of proteins involved in carbohydrate metabolism together with depressing phage genes responsible for cell wall degradation. The gene regulatory effect of PDIA in this phase of the bacterial growth is thus less prominent.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Functional comparison of DEGs in the PDIA treated-group compared to control group in early- and mature biofilm. Functions are organized into three groups, namely Biological processes, Cellular components, and Molecular functions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.H. and M.S.; Methodology, Ł.K., A.T-P and M.F.; Investigation, E.G and M.F.; Data curation, E.G., S.C. and Ł.K.; Writing – original draft preparation, P.H, S.C. and A.T-P.; Writing – review and editing, M.S. and A. T-P; Supervision, P.H. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Polish National Science Centre, grant number 2018/31/B/NZ6/02443.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/

Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

PDIA (beta-1-C-propyl-1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-L-arabinitol); SEM (scanning electron microscopy); PTS (phosphotransferase system); PCA (principal component analysis); GO (gene ontology); KEGG (Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes); BP (biological processes); CC (cellular components); MF (molecular functions).

References

- Hassoun-Kheir, N.; Guedes, M.; Ngo Nsoga, M.T.; Argante, L.; Arieti, F.; Gladstone, B.P.; Kingston, R.; Naylor, N.R.; Pezzani, M.D.; Pouwels, K.B.; et al. A systematic review on the excess health risk of antibiotic-resistant bloodstream infections for six key pathogens in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2024, 1, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, Y.C.; Cheug, C.; Bae, J.S.; Otto, M. Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence. 2021, 12, 547–569. [Google Scholar]

- Thurlow, L.R; Hanke, M.L.; Fritz, T.; Angle, A.; Aldrich, A.; Williams, S.H.; Engebretsen, I.L.; Bayles, K.W.; Horswill, A.R.; Kielian, T. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms prevent macrophage phagocytosis and attenuate inflammation in vivo. J Immunol. 2011, 186, 6585–6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T. J.; Geoghegan, J. A.; Ganesh, V. K.; Hook, M. Adhesion, invasion and evasion: the many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, J.L.; Horswill, H.R. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: recent developments in biofilm dispersal. Frontiers in Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compain, P.; Martin, O.R. Iminosugars: From Synthesis to Therapeutic Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2007; ISBN 9780470517437. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, R.J.; Kato, A.; Yu, C.-Y.; Fleet, G.W. Iminosugars as therapeutic agents: Recent advances and promising trends. Futur Med Chem 2011, 3, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans DeWald L, Starr C, Butters T, Treston A, Warfield KL. Iminosugars: A host-targeted approach to combat Flaviviridae infections. Antiviral Res. 2020 Dec;184: 104881. Epub 2020 Aug 5. [CrossRef]

- De Fenza, M.; D’Alonzo, D.; Esposito, A.; Munari, S.; Loberto, N.; Santangelo, A.; Lampronti, I.; Tamanini, A.; Rossi, A.; Ranucci, S.; et al. Exploring the effect of chirality on the therapeutic potential of N-alkyl-deoxyiminosugars: Anti-inflammatory response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections for application in CF lung disease. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 175, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gregorio, E.; Esposito, A.; Vollaro, A.; De Fenza, M.; D’Alonzo, D.; Migliaccio, A.; Iula, V.D.; Raffaele Zarrilli, R.; Guaragna, A. N-Nonyloxypentyl-l-Deoxynojirimycin inhibits growth, biofilm formation and virulence factors expression of Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, B.; Khan, S.N.; Haque, I.; Alam, M.; Mushfiq, M.; Khan, A.U. Novel anti-adherence activity of mulberry leaves: Inhibition of Streptococcus mutans biofilm by 1-deoxynojirimycin isolated from Morus alba. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008, 62, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strus, M.; Mikołajczyk, D.; Machul, A.; Heczko, P.; Chronowska, A.; Stochel, G.; Gallienne, E.; Nicolas, C.; Martin, O.R.; Kyzioł, A. Effects of the selected iminosugar derivatives on pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Microb Drug Resist 2016, 22, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozień,Ł. ; Gallienne, E.; Martin, O.; Front, S.; Strus, M.; Heczko, P. PDIA, an Iminosugar Compound with a Wide Biofilm Inhibitory Spectrum Covering Both Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Human Bacterial Pathogens. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozień, Ł.; Policht, A.; Heczko, P.; Arent, Z.; Bracha, U.; Pardyak, L.; Pietsch-Fulbiszewska, A.; Gallienne, E.; Piwowar P, Okoń, K. PDIA iminosugar influence on subcutaneous Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024, 14, 1395577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolas, C.; Martin, O.R. Glycoside Mimics from Glycosylamines: Recent Progress. Molecules 2018, 23, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, S.; Chung, S.J.; Igarashi, Y.; Ichikawa, Y.; Sepp, A.; Lechler, R.I.; Wu, J.; Hayashi, T.; Siuzdak, G.; Wong, C.H. Selective inhibition of beta-1,4- and alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferases: donor sugar-nucleotide based approach. Bioorg Med Chem 1999, 7, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.L.; Tyrrell, B.E.; Zitzmann, N. Mechanisms of Antiviral Activity of Iminosugars Against Dengue Virus. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018, 1062, 277–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, M.; Cheng, J.; Lee, Y.G.; Cho, J.H.; Suh, J.W. Discovery of Novel Iminosugar Compounds Produced by Lactobacillus paragasseri MJM60645 and Their Anti-Biofilm Activity against Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e0112222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluj, R.M.; Ebner, P.; Adamek, M.; Ziemert, N.; Mayer, C.; Borisova, M. Recovery of the Peptidoglycan Turnover Product Released by the Autolysin Atl in Staphylococcus aureus Involves the Phosphotransferase System Transporter MurP and the Novel 6-phospho-N-acetylmuramidase MupG. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, N.; Mukai, T. Production profile of the soluble lytic transglycosylase homologue in Staphylococcus aureus during bacterial proliferation. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2007, 49, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saier, M.H.; Reddy, B.L. Holins in bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea: multifunctional xenologues with potential biotechnological and biomedicalications. J Bacteriol 2015, 197, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, N.; Yan, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Lu, C.; Sun, J. Combined antibacterial activity of phage lytic proteins holin and lysin from Streptococcus suis bacteriophage SMP. Curr Microbiol 2012, 65, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Xie, L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, M.; Geng, W.; Wu, X.; Rodriguez, R.D.; Cheng, L.; Qiu, L. Cheng, C. Artificial Phages with Biocatalytic Spikes for Synergistically Eradicating Antibiotic-Resistant Biofilms. Adv Mat 2024, 16, 2404411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.J.; Vold, B.S. ; Staphylococus aureus has Clustered tRNA Genes. J Bacteriol 1993, 175, 5091–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet Journal 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Huber, W. HTSeq: a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P.; Binns, D.; Chang, H.Y.; Fraser, M.; Li, W.; McAnulla, C.; McWilliam, H.; Maslen, J.; Mitchell, A.; Nuka, G. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexa, A.; Rahnenfuhrer, J. topGO: Enrichment Analysis for Gene Ontology. 2024, R package version 2.58.0.

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, D353–D361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).