Introduction

Approximately 1.3 million cases of neonatal sepsis are reported annually worldwide [

1]. The neonatal immune system, which is inexperienced in adapting to the external environment, exhibits inadequate physical and chemical barriers, delayed T-cell response, and limited secretion of immunoglobulins. Consequently, newborns are highly susceptible to sepsis [

2,

3,

4]. In preterm and low-birthweight (LBW) neonates, the risk of infection is further exacerbated by extended hospital stays and invasive procedures. Moreover, the likelihood of sepsis increases with decreasing gestational age and birth weight [

5]. Neonatal sepsis has a case fatality rate of 2%, which escalates to 20% in preterm and LBW neonates [

6] and is correlated with various forms of developmental delay among survivors [

7].

As is extensively established, breastfeeding is vital in safeguarding preterm neonates against infections [

8]. Lactoferrin, a whey protein in colostrum and mature breast milk, is hypothesized to play a pivotal role in the immune response [

9]. Both in vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated that lactoferrin exhibits antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, modulates innate and adaptive immune responses, influences cytokine production, and affects the growth and migration of immune cells [

10]. These attributes may explain the inverse relationship between sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), infant mortality rates, and the quantity of lactoferrin consumed through breast milk [

11].

Bovine lactoferrin (bLF), like human lactoferrin, has been studied for its potential to prevent neonatal late-onset sepsis (LOS). However, conflicting results have been reported in randomized clinical trials, including the Lactoferrin Infant Feeding Trial (LIFT) [

14] and Enteral Lactoferrin Supplementation for Preterm Infants Trial (ELFIN). While the meta-analysis of the LIFT trial suggested a significant reduction in LOS risk with bLF supplementation, the overall certainty of evidence remains low.

Most trials on bLF have been conducted in high-income countries, despite the potential benefits being particularly relevant for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with a high burden of neonatal sepsis [

16]. Additionally, there was significant variation in the dosage of bLF used in previous trials, ranging from 100 mg to 300 mg, indicating a lack of consensus on the optimal dosage of bLF. We conducted a trial in Pakistan to address these gaps by using two different doses of bLF.

Methods

Trial Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a three-arm, double-blind, randomized controlled trial conducted in the NICU at the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH) in Karachi, Pakistan, in collaboration with the University of Sydney from July 2019 to August 2020. All preterm (28 to 36+5 weeks gestational age) and low birth weight (≥ 1000 g to < 2500 g) neonates born at AKUH, with no signs of sepsis and tolerating oral feeds within 72 h of birth, were included in the trial. The exclusion criteria were the presence of a congenital anomaly, sepsis before enrollment, maternal history of chorioamnionitis or group B streptococcus colonization, and consent refusal. The protocol for this study has been previously published [

17].

Randomization and Masking

Neonates who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to receive either placebo, D-glucose (arm A), 150 mg bLF (arm B), or 300 mg bLF (arm C) orally for 28 days. An independent statistician generated the random allocation sequence using STATA software, following a 1:1:1 ratio with equal probabilities for each treatment arm. A block size of nine was used for randomization to accommodate the expected number of participants recruited daily. In the case of multiple births, each neonate was randomized individually. Randomization codes were assigned to participant IDs and used to package the placebo and different doses of bLF, ensuring that the trial investigators, staff, and parents remained unaware of the sachet contents. The investigational product was sourced from Hilmar Ingredients in LA, USA and packaged by Pharmaceutical Packaging Professionals (PPP) Ltd. in Melbourne, Australia.

Procedures

The investigational product (bLF or placebo) was dissolved in breast milk (minimum 5 ml) or formula milk when breast milk was unavailable. The first dose of the investigational product was administered within 72 h of birth by a clinical nurse in the NICU/postnatal ward/nursery of AKUH with the mother or primary caregiver as an observer. The nurse provided instructions and a pictorial brochure to the caregiver, demonstrating the investigational product preparation and the feeding method. Ward nurses supervised subsequent trial feeding throughout the neonate's hospitalization. Upon discharge, caregivers received a one-week supply of the investigational product and were instructed to return unused empty sachets during weekly visits.

Outcomes

The trial's outcome of interest was the incidence of late-onset sepsis (LOS), encompassing both clinical and culture-proven sepsis, from the time of trial entry to 28 days of life. Clinical sepsis is characterized by signs or symptoms, such as lethargy, apnea, respiratory distress, reluctance to feed, temperature instability, difficulty tolerating feeds, vomiting, aspiration, abdominal distention, and seizures. In addition, it required the presence of at least one abnormal laboratory parameter, including a high C-reactive protein level (> 1 mg/dL), abnormal white blood cell count (<7.0×103/uL or >23.0×103/uL), or low blood glucose level (< 40 mg/dL). A physician's assessment of sepsis or administration of antibiotics by a clinician also qualified as criteria for clinical sepsis.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was late-onset sepsis, including both presumed/clinical sepsis and culture-proven sepsis, from the trial entry to 28 days. Presumed or clinical sepsis was defined as any sign of sepsis, including lethargy, apnea, tachypnea/respiratory distress, reluctance to feed, temperature instability, feed intolerance, vomiting, aspiration, abdominal distention, and seizures, in addition to any one of the following laboratory parameters: (1) raised C-reactive protein level (> 1 mg/dL), (2) deranged white blood cell count (<7.0×103/uL or >23.0×103/uL), (3) hypoglycemia (< 40 mg/dL), and either a physician’s assessment of sepsis or administration of antibiotics by a clinician. Culture-proven sepsis was defined as the presence of the above clinical signs and positive blood culture results.

The secondary outcomes were necrotizing enterocolitis diagnosed based on Bell's criteria (Bell’s stages II and III) [

18] from trial entry to the 28

th day of life and neonatal mortality. We also compared the two doses of bLF to determine the optimal daily dose of bLF to prevent late-onset sepsis.

Data Collection

Data collection included daily information on the neonate's clinical course, demographics, and maternal history during hospitalization. Weekly household follow-up visits were conducted until 28±2 days of age to assess newborn well-being, feeding practices, feeding intolerance, history of illness, and treatment sought. Physical examination was performed at each visit. The first visit occurred at the Clinical Trial Unit of AKUH, followed by subsequent home visits. Body measurements were recorded at birth and again on the 14th and 28th days. To guarantee compliance, sachet retrieval and phone calls were conducted twice per week. The number of sachets was used to determine the adherence levels.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated by assuming the incidence of neonatal sepsis in the placebo group to be 25% (based on the current hospital data) and the incidence of neonatal sepsis in the bLf group to be 8%, at 80% power with a 95% confidence level. The sample size was further adjusted to account for an estimated 10% loss to follow-up. Based on the above assumptions, the estimated sample size in each study arm was 95 (rounded off to 100) LBW neonates, resulting in 300 LBW neonates in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Intention-to-treat analysis was conducted using STATA version 17 (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software, College Station, TX, StataCorp LLC). Categorical data were reported as frequencies and percentages. For continuous variables, means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were reported as appropriate. Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests were used to compare categorical data between the placebo and each intervention arm as appropriate. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the anthropometric measurements among the groups.

Ethical Considerations

Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of Aga Khan University, Pakistan (ERC: 2020-0238-139190), University of Sydney, Australia (ID: 2017/420), and National Bioethics Committee (NBC), Pakistan (NBC-259). This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03431558). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of the enrolled neonates after they read the patient information sheet and consent form. All serious adverse events (SAEs) and suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) were reported within 24 h by ethics committees.

Results

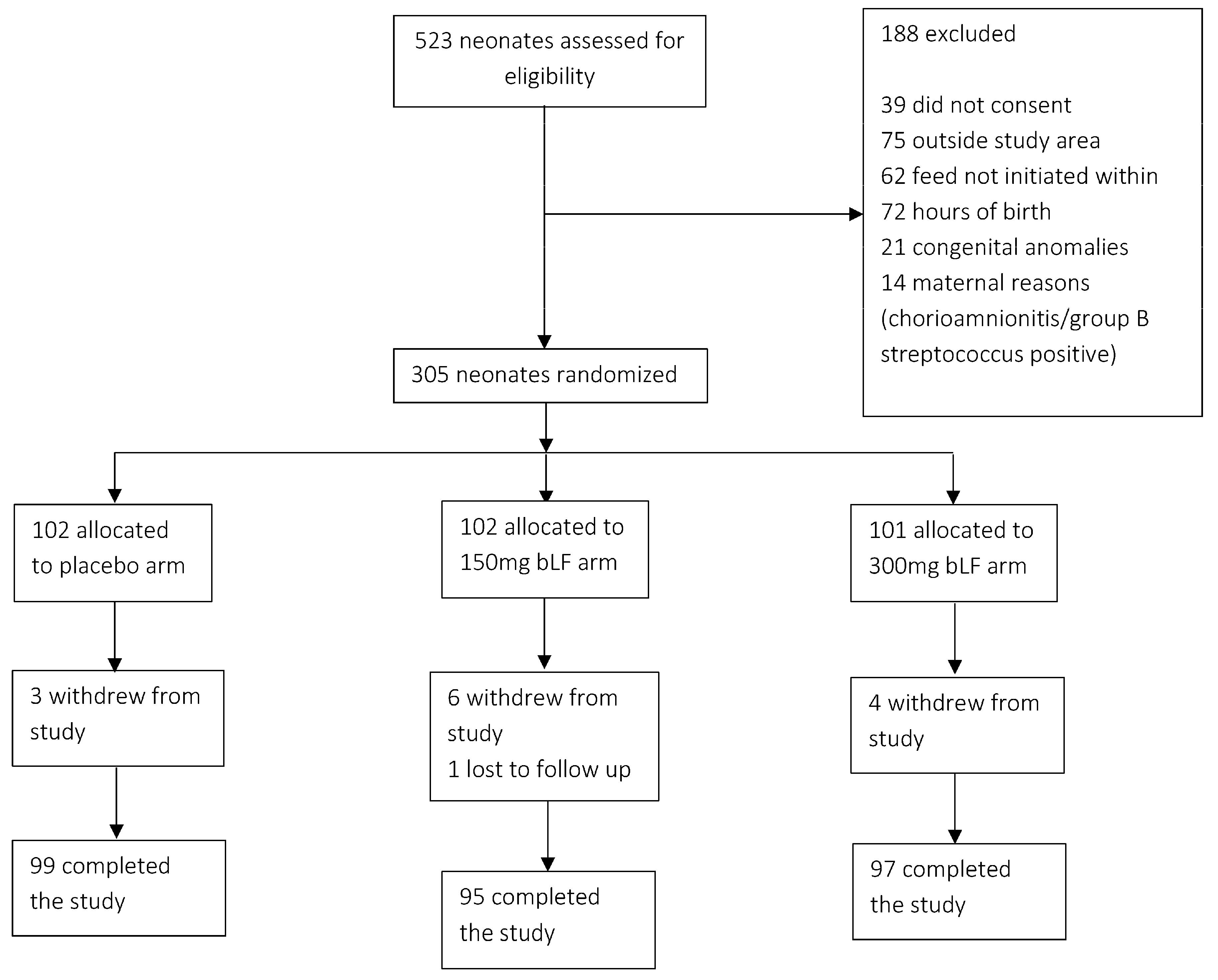

Of the 532 neonates screened, 305 were enrolled in the study. Of these, 102 were allocated to the placebo arm, 102 to the arm receiving 150 mg bLF, and 101 to the arm receiving 300 mg bLF. On the 28th day of life, follow-up data were obtained from 291 participants. In comparison, 14 participants withdrew from the study for reasons such as migration, withdrawal of consent, or death (

Figure 1).

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the participants. Of the enrolled neonates, 85.2% (n=260) were delivered via cesarean section, while 14.8% (n=45) were born through spontaneous vaginal delivery. The majority of patients (54.3%; n=165) were female. The mean gestational age and birth weight were 34 weeks and 1900 g, respectively. Surfactant was administered to 4.6% (n=14), and antibiotics to 29.5% (n=90) of the neonates. Among the neonates, 52.8% (n=161) required respiratory support, with 95.6% (n=154) receiving noninvasive ventilation (62.1% CPAP and 33.5% high-flow oxygen), and 4.3% (n=7) received invasive ventilation. During the trial period, approximately 51.5% (n=150) of the neonates were exclusively breastfed, 48.1% (n=140) received mixed feeding, and only 0.3% (n=1) were exclusively formula fed.

There was a significant difference in the number of episodes of culture-confirmed late-onset sepsis (LOS) between the placebo arm (8 cases, 8%) and the arm receiving 150 mg bLF (1 case, 1%), with a p-value of 0.02. However, the incidence of culture-proven LOS was similar between newborns administered 300 mg bLF (5 cases, 5%) and those in the placebo arm (p = 0.39). In total, 11 (11%) newborns in the placebo group, five (5%) in the 150 mg bLF group, and eight (8%) in the 300 mg bLF group were identified with either culture-proven or clinical sepsis. No significant differences were observed in either culture-proven or clinical sepsis between the placebo and 150 mg bLF groups (p=0.140), or between the placebo and 300 mg bLF groups (p=0.470) (

Table 2).

Additionally, no significant differences were found in the occurrence of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) between the placebo and 150 mg bLF groups (n=3, 3% vs. n=0, p=0.09) or between the placebo and 300 mg bLF groups (n=3, 3% vs. n=2, 2%, p=0.65).

Altogether, 38 newborns required hospitalization after discharge due to sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) as follows: 13.1% (13 newborns) from the placebo arm, 9.5% (9 newborns) from the 150 mg bLF arm, and 16% (16 newborns) from the 300 mg bLF arm. The median length of hospital stay for sepsis or NEC was the highest in the placebo arm: 14 days (IQR: 4-22), 7 days (IQR: 4-12) in the 150 mg bLF arm, and 6 days (IQR: 3-10.5) in the 300 mg bLF arm.

Anthropometric measurements of the participating newborns were tracked until day 28, and no significant differences were detected in weight or average weight gain between the three groups on both the 14th and 28th days (

Table 3).

Two fatalities occurred in the arm that received 300 mg bLF during the trial. However, it was concluded that these incidents were not connected to the trial intervention.

Among the 291 neonates who completed the study, 79 (79.79%) in the placebo arm, 78 (82.1%) in the 150 mg bLF arm, and 82 (84.53%) in the 300 mg bLF arm consumed the investigational product (IP). Compliance, assessed by the number of sachets used per 30 days, was comparable between the three arms (

Table 4).

Discussion

Our study found that enteral supplementation with 150 mg of bovine lactoferrin (bLF) was associated with a reduction in culture-proven late-onset sepsis (LOS) in preterm and low-birthweight (LBW) neonates. However, administering a higher dose of bLF did not have an impact. These results were unexpected, as one would anticipate that a higher dose of bLF would have a more significant clinical impact.

Previous trials on enteral supplementation with bLF have demonstrated variable effectiveness of the intervention on LOS, reporting risk ratios ranging from 0.24 to 1.05 [

19]. The variances between the trials can be attributed to the different care practices in the facilities where the trials were conducted and the different doses, regimes, and sources of lactoferrin used in the studies [

20].

In addition to the current study, we found only one other trial of lactoferrin conducted in an LMIC [

21]. Neonatal sepsis is estimated to be 2-3 times higher in LMICs than in high-income countries [

22]. Poor sanitation, low socioeconomic status, maternal malnutrition, overcrowding, low exclusive breastfeeding rates, higher prematurity and low birthweight rates, and suboptimal quality of care significantly increase the risk of neonatal sepsis in low-resource settings [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Moreover, difficulties in the early diagnosis of sepsis and the use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials with the subsequent emergence of multidrug-resistant organisms increase morbidity and mortality in low-resource settings [

27,

28,

29]. This study was conducted in a private tertiary care hospital with a well-established sepsis-screening protocol in an urban setting. Therefore, it is possible that many of the participants included in the trial did not have most of the risk factors unique to a resource-poor population. Kaur et al., who conducted their trial in India with a sociodemographic profile similar to Pakistan, showed lactoferrin's protective effect on neonatal sepsis [

21]. Additionally, Ochoa et al. demonstrated that infants with lower breastmilk intake are more likely to benefit from bLF supplementation [

30]. These findings merit further studies in LMICs, as the potential preventative benefits of lactoferrin are likely to have the greatest impact in settings where breastfeeding rates are low and the incidence of sepsis is high. Lack of access to or poor quality of care prevents appropriate and timely management.

Although we did not observe a difference in the incidence of NEC across the study arms, research using animal models has shown that lactoferrin could potentially protect against necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). However, human studies have not corroborated these findings [

31]. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reported a risk ratio of 1.10 (95% CI, 0.86 to 1.41) for developing NEC among neonates receiving lactoferrin compared to placebo [

19].

Animal studies also suggested lactoferrin may improve nutrient absorption and growth [

32]. However, similar to previous human studies [

33], our trial did not record any effect of lactoferrin supplementation on the growth rates of preterm infants.

Our study has notable strengths, including a high compliance rate (97%). Compliance was ensured through reminders and home visits. Before the trial, a TIPS was conducted to ensure acceptability and develop clear usage instructions.

This study has some limitations. The incidence of neonatal sepsis was the outcome of interest. Importantly, our trial included a relatively small group of 300 infants. A larger study group might have resulted in more sepsis events, which would offer a more thorough understanding of the implications of lactoferrin supplementation. Although, understandably, families chose physicians close to their homes for convenience after hospital discharge, this may have led to some episodes of sepsis being missed in our study.

Conclusion

Enteral supplementation with bLF may decrease late-onset sepsis in preterm and low-birthweight infants. However, more extensive studies are needed, especially in resource-limited low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Future studies should also investigate the optimal lactoferrin dosages.

Statement of Authorship

MD, SA, and SBS hypothesized and designed the study. MA, SA, and AA developed the instruments and the trial protocol. AA and SA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. UA and AR perform statistical analyses. SA, SBS, and MD critically reviewed the manuscript and provided feedback. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The US Agency for International Development funded this study through the University of Sydney (award # AID-OAA-F-17-00013). USAID had no role in the study design, data collection, management, analyses, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the AKUH NICU team, Dr. Khalil Ahmed, Dr. Sohail Salat, De Adnan Mirza, Dr. Sadia Sheikh, Dr. Hussain Shah, Dr. Waqar Khowaja, Dr. Amin Ali, Dr. Muzaffar, Simon Demas, Noureen Lalani, and the AKUH Secondary Hospitals team for their support and facilitation of the study procedures.

References

- Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018, 392, 1789–858. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollmann, T.R.; Kampmann, B.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Marchant, A.; Levy, O. Protecting the Newborn and Young Infant from Infectious Diseases: Lessons from Immune Ontogeny. Immunity. 2017, 46, 350–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonk, E.C.M.; Piersma, A.H.; Van Loveren, H. 5.13 - Reproductive and Developmental Immunology. In: McQueen CA, editor. Comprehensive Toxicology (Second Edition). Oxford: Elsevier; 2010. p. 249-69.

- Wynn, J.L.; Wong, H.R. Pathophysiology of neonatal sepsis. Fetal and Neonatal Physiology. 2017:1536.

- McGuire, W.; Clerihew, L.; Fowlie, P.W. Infection in the preterm infant. Bmj. 2004, 329, 1277–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, E.; Yanowitz, T. Infections in the NICU: Neonatal sepsis. Seminars in Pediatric Surgery. 2022, 31, 151200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savioli, K.; Rouse, C.; Susi, A.; Gorman, G.; Hisle-Gorman, E. Suspected or known neonatal sepsis and neurodevelopmental delay by 5 years. J Perinatol. 2018, 38, 1573–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.; França, G.V.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016, 387, 475–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, T.J.; Sizonenko, S.V. Lactoferrin and prematurity: a promising milk protein? Biochem Cell Biol. 2017, 95, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, D. Overview of Lactoferrin as a Natural Immune Modulator. J Pediatr. 2016;173 Suppl:S10-5.

- Ochoa, T.J.; Mendoza, K.; Carcamo, C.; Zegarra, J.; Bellomo, S.; Jacobs, J.; et al. Is Mother's Own Milk Lactoferrin Intake Associated with Reduced Neonatal Sepsis, Necrotizing Enterocolitis, and Death? Neonatology. 2020, 117, 167–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Timilsena, Y.P.; Blanch, E.; Adhikari, B. Lactoferrin: Structure, function, denaturation and digestion. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019, 59, 580–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibbering, P.H.; Ravensbergen, E.; Welling, M.M.; van Berkel, L.A.; van Berkel, P.H.; Pauwels, E.K.; et al. Human lactoferrin and peptides derived from its N terminus are highly effective against infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Infect Immun. 2001, 69, 1469–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnow-Mordi, W.O.; Abdel-Latif, M.E.; Martin, A.; Pammi, M.; Robledo, K.; Manzoni, P.; et al. The effect of lactoferrin supplementation on death or major morbidity in very low birthweight infants (LIFT): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020, 4, 444–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enteral lactoferrin supplementation for very preterm infants: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019, 393, 423–33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa, T.J. Is lactoferrin still a treatment option to reduce neonatal sepsis? Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020, 4, 411–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariff, S.; Soofi, S.; Aamir, A.; D'Almeida, M.; Aziz Ali, A.; Alam, A.; et al. Bovine Lactoferrin to Prevent Neonatal Infections in Low-Birth-Weight Newborns in Pakistan: Protocol for a Three-Arm Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021, 10, e23994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.J.; Ternberg, J.L.; Feigin, R.D.; Keating, J.P.; Marshall, R.; Barton, L.; et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg. 1978, 187, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pammi, M.; Suresh, G. Enteral lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020, 3, Cd007137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrington, J.E.; McGuire, W.; Embleton, N.D. ELFIN, the United Kingdom preterm lactoferrin trial: interpretation and future questions (1). Biochem Cell Biol. 2021, 99, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Gathwala, G. Efficacy of Bovine Lactoferrin Supplementation in Preventing Late-onset Sepsis in low Birth Weight Neonates: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J Trop Pediatr. 2015, 61, 370–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, C.; Reichert, F.; Cassini, A.; Horner, R.; Harder, T.; Markwart, R.; et al. Global incidence and mortality of neonatal sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2021, 106, 745–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwor, O.C.; McKelvie, B.; Frizzola, M.; Hunter, K.; Kabara, H.S.; Oduwole, A.; et al. A National Survey of Resources to Address Sepsis in Children in Tertiary Care Centers in Nigeria. Front Pediatr. 2019, 7, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.; Godinho, M.A.; Guddattu, V.; Lewis, L.E.S.; Nair, N.S. Risk factors of neonatal sepsis in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0215683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adatara, P.; Afaya, A.; Salia, S.M.; Afaya, R.A.; Konlan, K.D.; Agyabeng-Fandoh, E.; et al. Risk Factors Associated with Neonatal Sepsis: A Case Study at a Specialist Hospital in Ghana. ScientificWorldJournal. 2019, 2019, 9369051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohanon, F.J.; Nunez Lopez, O.; Adhikari, D.; Mehta, H.B.; Rojas-Khalil, Y.; Bowen-Jallow, K.A.; et al. Race, Income and Insurance Status Affect Neonatal Sepsis Mortality and Healthcare Resource Utilization. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018, 37, e178–e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, O.; Khan, A.; Ambreen, A.; Ahmad, I.; Akhtar, T.; Gandapor, A.J.; et al. Antibiotic Sensitivity pattern of Bacterial Isolates of Neonatal Septicemia in Peshawar, Pakistan. Arch Iran Med. 2016, 19, 866–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.W.; Blau, D.M.; Bassat, Q.; Onyango, D.; Kotloff, K.L.; Arifeen, S.E.; et al. Initial findings from a novel population-based child mortality surveillance approach: a descriptive study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020, 8, e909–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Hameed, A.; Roghani, M.T.; Ullah, Z. Multidrug resistant neonatal sepsis in Peshawar, Pakistan. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002, 87, F52–F54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, T.; Loli, S.; Mendoza, K.; Carcamo, C.; Bellomo, S.; Cam, L.; et al. Effect of bovine lactoferrin on prevention of late-onset sepsis in infants <1500 g: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from two randomized controlled trials. Biochem Cell Biol. 2021, 99, 14–9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, H.; Li, B.; Robinson, S.C.; Lee, C.; O'Connell, J.S.; et al. Lactoferrin Reduces Necrotizing Enterocolitis Severity by Upregulating Intestinal Epithelial Proliferation. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2020, 30, 90–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robblee, E.D.; Erickson, P.S.; Whitehouse, N.L.; McLaughlin, A.M.; Schwab, C.G.; Rejman, J.J.; et al. Supplemental lactoferrin improves health and growth of Holstein calves during the preweaning phase. J Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 1458–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, W.H.; Ashley, C.; Yeiser, M.; Harris, C.L.; Stolz, S.I.; Wampler, J.L.; et al. Growth and tolerance of formula with lactoferrin in infants through one year of age: double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).