1. Introduction

In aquatic ecosystems, both the mean and variance of several abiotic factors, such as temperature, pH, and salinity, play crucial roles in shaping biological communities [

1]. While temperature and pH are recognized as key abiotic factors influencing aquatic environments, salinity is particularly significant due to its profound impact on species' osmoregulatory capacities across a variety of aquatic habitats, ranging from freshwater to hypersaline ecosystems [

2]. The ability of organisms to tolerate specific salinity levels is intrinsically linked to their osmoregulatory mechanisms, which are shaped by their life history traits. To maintain osmotic balance, organisms expend considerable energy regulating ion uptake and secretion in response to hypoosmotic and hyperosmotic conditions, thereby ensuring stable internal fluid concentrations [

3]. However, despite the growing understanding of salinity's impact on aquatic organisms, a significant research gap remains regarding the species-specific mechanisms of osmoregulation across diverse environments, particularly in the context of rapidly changing climate conditions. This study addresses this gap by exploring the adaptive strategies employed by various species to cope with fluctuating salinity levels and the broader implications of these adaptations for ecosystem stability and biodiversity.

The evolution of osmoregulatory mechanisms has enabled aquatic organisms to colonize diverse ecological niches [

4], with adaptations occurring at the molecular, physiological, ecological, and behavioral levels to cope with varying salinity conditions [

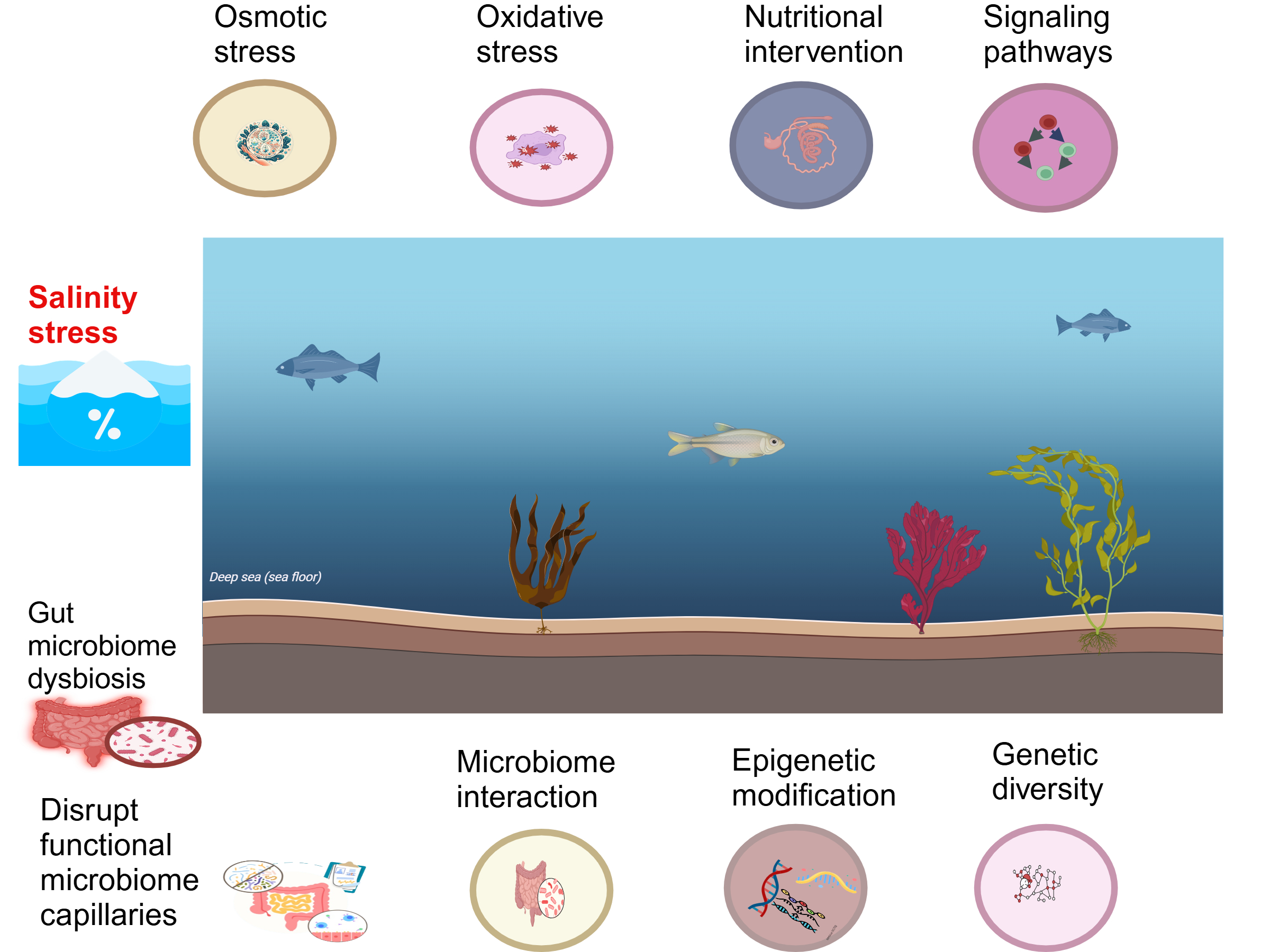

5]. At the behavioral level, organisms may modify their feeding or movement patterns to avoid stressful conditions or seek more favorable environments. At the molecular level, they respond to salinity stress through changes in gene expression, activation of signaling pathways, and epigenetic modifications [

6]. Physiologically, osmoregulatory processes involving ion transport are essential for maintaining internal homeostasis across environmental salinity gradients [

7].

For species to effectively adapt to salinity stress, they must exhibit appropriate genetic diversity and population structure [

8]. For instance, organisms with greater genetic diversity typically exhibit a wider range of physiological responses to fluctuations in salinity, enhancing their survival in environments with variable salinity levels [

9]. Furthermore, genetic diversity in gill function, osmoregulatory processes, and the production of antioxidant enzymes plays a critical role in determining species’ ability to cope with salt-induced oxidative stress [

10]. Beyond intrinsic traits, interactions between host organisms and their microbiomes can also influence their tolerance to salinity stress [

11]. Specifically, by modulating host physiology [

12] and enhancing stress responses [

13], the microbiome can significantly affect how aquatic organisms respond to fluctuating salinity levels.

Despite the recognized importance of salinity adaptation for the survival of aquatic species, significant gaps remain in our understanding of the ecological impacts, adaptive mechanisms, and molecular responses of aquatic organisms, particularly among crustaceans and fish. This knowledge is increasingly critical in the context of global environmental changes, as anthropogenic activities not only alter salinity levels and introduce other stressors [

14] but also affect the population and genetic structures of species, which in turn influence their capacity to respond to these changes [

15]. This review aims to address these gaps by synthesizing current knowledge on the physiological, behavioral, and molecular adaptations that enable aquatic organisms to survive and thrive in environments with fluctuating salinity. Furthermore, it explores the roles of epigenetic mechanisms, microbiome interactions, and genetic diversity in enhancing tolerance to salinity stress. Finally, the review highlights the broader ecological consequences of salinity variation and proposes mitigation strategies to support species survival and ensure the long-term stability and conservation of aquatic ecosystems in the face of environmental change.

2. Ecological Impact of Salinity Stress

Aquatic organisms have developed a range of adaptive strategies to cope with the ecological pressures imposed by salinity stress, which allows them to thrive in environments with fluctuating salinity levels. This section explores the physiological, behavioral, molecular, and cellular mechanisms that enable these organisms to withstand and adapt to such fluctuations.

2.1. Salinity Ranges in Aquatic Environment

Aquatic ecosystems exhibit a wide range of salinity levels, from less than 1 ppt in freshwater environments to over 400 ppt in hypersaline habitats [

7]. In estuarine regions, where freshwater meets seawater, salinity fluctuates from 0.5 to 35 ppt on a daily or seasonal basis, influenced by factors such as tides, river inflows, and evaporation [

16]. These dynamic salinity gradients create distinct ecological zones, with transitional areas that support both freshwater and marine species. These zones often exhibit greater biodiversity compared to strictly freshwater or marine systems [

17]. Hypersaline environments, such as shallow lagoons and arid coastal regions, may reach salinities of up to 350 ppt, as seen in areas like the Gulf of Mexico, Mediterranean, and Red Sea [

18].

2.2. Effect of Salinity Variability on Species Distribution and Biodiversity

In estuarine ecosystems, species display varying levels of tolerance to salinity fluctuations. Euryhaline species are capable of thriving across a wide range of salinity levels, while stenohaline species are restricted to environments with more stable salinity, either freshwater or marine. Salinity fluctuations can induce physiological stress in organisms, particularly invertebrates, which often have fewer tolerant species compared to fish [

19]. This stress can lead to significant shifts in community composition, especially within invertebrate populations, which may become dominated by lentic taxa as freshwater environments become more saline [

20]. Such shifts underscore the role of salinity variability in shaping invertebrate communities and the broader ecological implications for biodiversity in temporary saline habitats.

Hypersaline environments, characterized by salinities exceeding that of seawater, represent extreme cases of salinity fluctuation and typically exhibit reduced biodiversity. However, certain species have evolved remarkable adaptations that enable them to survive under these harsh conditions. For instance, Artemia can tolerate salinities exceeding 100 ppt due to their advanced osmotic regulatory mechanisms [

21]. In these extreme environments, species richness tends to decline, and community composition shifts toward a small number of highly specialized species. As salinity surpasses 35 g/L, only species with exceptional salinity tolerance are able to persist, resulting in the dominance of crustaceans, particularly Artemia, which is the most prevalent taxon in these ecosystems [

22].

The presence of specialized species in hypersaline environments highlights the adaptability of organisms to fluctuating salinity levels, which is crucial for maintaining ecosystem functionality [

23]. Salt-tolerant invertebrates form the foundation of food webs in these environments, supporting other species, such as salt-tolerant fish and migratory birds that rely on these habitats for foraging and nesting [

24]. While a general negative correlation exists between fish diversity and salinity [

2].

2.3. Climate Change Implications on Salinity Fluctuations

Climate change is altering salinity dynamics in marine ecosystems through increased evaporation, shifting precipitation patterns, and polar ice melt, all of which contribute to both hyper- and hyposaline conditions [

25]. These salinity fluctuations, compounded by other climate stressors such as ocean warming and acidification, are intensifying stress on marine organisms, with adverse effects on their physiological functions and survival. For instance, marine bivalves like Crassostrea gigas and Mytilus edulis exhibit increased carbonic anhydrase activity under conditions of both low salinity and ocean acidification, suggesting potential negative impacts on biomineralization and shell formation[

26,

27].

The interaction between temperature and salinity fluctuations can present an even greater risk to marine organisms than each stressor in isolation. Mussels subjected to both low salinity and high temperatures show an elevated expression of stress-related genes, indicating heightened stress due to the combined impact of thermal and salinity fluctuations resulting from the increased energetic demands required to maintain homeostasis under these concurrent conditions [

28]. In regions where both temperature and salinity are rising, species that are sensitive to these changes face heightened risks of population declines or even extinctions. A study by [

29] found that species in coastal ecosystems experiencing both temperature and salinity stressors showed lower reproductive success and higher mortality rates, suggesting that these environmental changes could push already vulnerable species beyond their physiological limits.

Climate-induced shifts are also driving significant changes in species distributions, leading to disease outbreaks in several species and having wide-ranging impacts on ecosystem dynamics [

30]. For example, warming temperatures above 15°C impair the immune system of Homarus americanus, making them more susceptible to diseases like gaffkemia and epizootic shell disease. In Chionoecetes opilio, thermal stress has triggered outbreaks of bitter crab disease caused by Hematodinium, with prevalence increasing five-fold per 1°C rise in temperature [

31]. These shifts disrupt host-pathogen dynamics, often favoring pathogen proliferation over host defenses, particularly in ectothermic species. These findings emphasize the need for adaptive management strategies that account for the synergistic effects of multiple climate stressors to protect biodiversity and maintain ecosystem resilience in the face of climate change.

3. Organismal Adaptations to Salinity Stress

To persist and thrive in environments with variable salinity, aquatic organisms employ a range of adaptive strategies that include both physiological and behavioral mechanisms. This section explores these adaptations in detail.

3.1. Adaptive Strategies for Salinity Tolerance in Aquatic Organisms

Maintaining osmotic homeostasis in environments where salinity fluctuates is crucial for survival. Freshwater species, such as teleost fish, maintain osmotic balance by actively absorbing salts from the environment and excreting dilute urine to counteract passive salt loss and excessive water influx. In contrast, marine species face the challenge of preventing dehydration and excessive salt accumulation. These species conserve water and excrete excess salts primarily through specialized cells in the gills and kidneys [

32].

Euryhaline fish, which inhabit environments with fluctuating salinity, possess osmoregulatory mechanisms that enable them to transition between freshwater and marine conditions. In seawater, euryhaline fish are hyperosmotic, maintaining higher internal salinity than the surrounding water. When in freshwater, they shift to hypoosmotic regulation. This transition involves complex signaling pathways and ion transport processes that adjust the absorption and excretion of ions in response to changing salinity levels. For instance, Oreochromis mossambicus adjusts its gill permeability to NaCl at high salinities, increasing Na+/K+-ATPase activity and enhancing ionocyte size to optimize NaCl absorption at low salinities [

33].

Diadromous fish, which migrate between freshwater and marine environments, exhibit complex life cycles that accommodate transitions between distinct salinities. Their ability to maintain euryhalinity has evolved independently across multiple teleost lineages, demonstrating the remarkable physiological and evolutionary flexibility of these species [

34].

Marine elasmobranchs employ a distinct osmoregulatory strategy, using organic osmolytes such as trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) to maintain osmotic balance. They excrete excess NaCl through the rectal gland, a strategy that contrasts with most teleost fish, which rely on different osmoregulatory mechanisms to actively regulate their extracellular fluid osmolality [

35]. In contrast, hagfish are osmoconformers, maintaining body fluid NaCl concentrations that closely match seawater, thereby minimizing the need for active osmoregulation [

36]. These varied strategies highlight the diverse adaptations among fish species to maintain osmotic balance across different environments.

Crustaceans have evolved isosmotic intracellular regulation, a mechanism that allows cells to adjust their volume in response to osmotic stress. In low salinity environments, cells reduce their regulatory volume to prevent swelling, while in high salinity environments, they increase regulatory volume to maintain cellular integrity. This intracellular regulation is favored over isosmotic extracellular regulation due to its greater efficiency in managing cellular volume under varying salinity conditions [

37]. Additionally, osmoregulatory capacities can be gender-specific, as seen in species like Callinectes sapidus, where such mechanisms may contribute to the species' invasive success [

38].

3.2. Behavioral Adaptations to Salinity Fluctuations in Aquatic Organisms

Aquatic organisms living in ecosystems with frequent salinity fluctuations have developed a variety of behavioral adaptations to cope with these changes. A key strategy is selective habitat use. Many species, particularly those in hypersaline or brackish environments, avoid high-salinity areas by seeking out habitats with lower salinity, thus minimizing osmoregulatory stress. This behavior enables them to allocate energy toward fitness-enhancing functions [

24]. For example, Kryptolebias marmoratus, a euryhaline killifish, increases its activity levels in hypersaline areas to locate refuges with lower salinity, thereby reducing osmoregulatory stress [

39]. Similarly, Poecilia latipinna seeks lower-salinity areas, particularly when exposed to predator cues, further reducing physiological strain [

39]. Additionally, individual traits within populations can vary, with mangrove rivulus demonstrating greater resilience to rapid changes in salinity than others [

40]. This variability in tolerance enhances the overall population's ability to survive and thrive under fluctuating environmental conditions.

3.3. Osmotic Stress and Ion Transport Mechanisms Response in Fluctuating Salinity Environments

The physiological response of aquatic organisms to hypo- and hyper-salinity stress, emphasizing the complex mechanisms involved in maintaining osmotic balance. When exposed to fluctuating salinity, organisms activate ion transport mechanisms, such as Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase, to regulate the movement of ions across their membranes and maintain osmotic equilibrium. This activation, however, comes at a significant cost, as it increases the energy demand required to support the enhanced ion transport. To meet these heightened energy requirements, organisms must increase their overall energy expenditure. Additionally, as part of this adaptive response, gill permeability is adjusted to facilitate more efficient ion exchange. Collectively, these physiological adjustments enable organisms to cope with the challenges posed by fluctuating salinity environments, ensuring their survival and maintaining homeostasis under osmotic stress (

Figure 1) [

7].

Exposure to hyperosmotic conditions triggers specific molecular responses to support osmotic regulation. For example, hyperosmotic stress activates phosphorylation of tight junction proteins by myosin light chain kinase, which modulates the activity of Na⁺/Cl⁻/taurine co-transporters, helping to maintain ion balance [

41]. In hypoosmotic conditions, dephosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase enhances the activity of Na⁺/K⁺/2Cl⁻ co-transporters and Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator, aiding ion regulation and restoring osmotic equilibrium [

42]. Furthermore, the expression of osmotic stress transcription factor 1 Osteoclast Stimulating Factor 1 is upregulated in response to salinity fluctuations, further modulating these transport mechanisms to help organisms to adopt varying osmotic environments [

43].

Different species exhibit unique adaptations to cope with salinity fluctuations. For example, Sinonovacula constricta, can maintains osmotic balance by modulating free amino acids like taurine and increasing Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase activity in the gills under fluctuating salinities [

44]. Similarly, juvenile Eriocheir sinensis display optimal osmoregulatory performance at 8‰ salinity, but their ion transport is disrupted when salinity deviates from range [

45].

Some marine fish also exhibit remarkable adaptations to fluctuating salinity. Species such as O. mossambicus, undergo extensive gill remodeling and adjust their ion transport systems to meet the high energy demands of fluctuating salinities [

46]. Similarly, the Fundulus heteroclitus, and Tilapia sp. adjust ion transport and use neuroendocrine regulation to cope with salinity changes [

47]. The Acanthopagrus schlegelii, also adapts by changing gene expression in its gills, enhancing ion transport efficiency and adjusting Na⁺/K ⁺-ATPase activity [

48].

Chronic salinity stress requires long term metabolic adjustments to maintain homeostasis. For example, in response to prolonged salinity exposure, Salmo salar undergo metabolic reprogramming that regulates enzymes and pathways for salt metabolism to cope with prolonged salinity exposure [

32]. Migratory species also benefit from intermediate salinities during migration through brackish waters, enhancing larval development [

49]. Collectively, these studies suggest species use unique adaptation such as gill remodeling and metabolic reprogramming to survive in fluctuating salinities.

3.4. Oxidative Stress Response in Aquatic Organisms Due to Salinity Stress

Salinity stress induces oxidative stress by disrupting redox balance through interactions between osmotic and oxidative pathways (

Table 1) [

50]. This imbalance increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to cellular damage. The production of ROS occurs as a result of altered cellular respiration and metabolic processes in response to salinity changes [

7]. Organisms activate antioxidant defense mechanisms such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) to mitigate this oxidative damage [

51]. For example, fluctuating salinities elevate ROS levels in Scylla serrata, which triggers the activities of these antioxidant enzymes [

52]. On the other hand rapid salinity reductions in E. sinensis compromise oxidative balance by lowering antioxidant enzyme activities, but enhance defenses through an increase in total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), GSH-PX, and CAT activity [

53].

Species can adapt to salinity-induced oxidative stress by altering respiration and metabolic strategies. For instance, Tigriopus brevicornis reduces oxygen consumption under stressful conditions, suggesting a different metabolic strategy to conserve energy and mitigate oxidative damage [

54]. In bivalves such as Crassostrea gigas, the activation of antioxidant enzymes is triggered, which helps mitigate oxidative stress [

55]. The sensitivity of Mytilus galloprovincialis to oxidative stress is particularly evident when salinity fluctuates. At low salinity, markers like protein carbonyls significantly increase in gill tissues. These markers are suppressed at moderate salinity but rise again at higher salinity [

56]. These studies support the dynamic nature of oxidative stress responses in bivalves under varying salinity conditions.

Fish also employ diverse strategies to manage oxidative stress caused by salinity fluctuations. For example, Chanos chanos upregulate enzymatic antioxidants to maintain redox balance and prevent apoptosis in seawater, but in freshwater conditions, it experiences oxidative stress and apoptosis despite increased antioxidant enzyme activity [

57]. Similarly, antioxidant-rich diets further enhance these enzymatic defenses, as observed in Salmo trutta, where dietary supplements improve CAT and GPx activity, thus protecting against oxidative damage [

58]. According to these studies fish employ a range of strategies, including enzymatic regulation and dietary adaptations to mitigate oxidative stress and maintain redox homeostasis under fluctuating salinity conditions.

3.5. Molecular Responses to Salinity Stress

3.5.1. Key Signaling Pathways

Signaling pathways are vital in mediating responses to environmental stressors like salinity fluctuations. These pathways facilitate a number of important processes, including ion transport, osmoregulation, cell survival, metabolism, and immunity. This section examines important signaling pathways AMPK, PI3K-AKT, MAPK, and Hippo pathway (

Table 2) that play a fundamental role in maintaining homeostasis. The intricate molecular signaling pathways activated in response to salinity stress, highlighting the complex mechanisms that enable organisms to cope with fluctuating salinity levels. Upon exposure to salinity stress, two major pathways, AMPK and MAPK, are activated to regulate critical processes such as glycolysis, fatty acid oxidation, and energy metabolism, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis. Additionally, calcium (Ca²⁺) signaling plays a pivotal role in triggering intracellular responses. The figure also emphasizes the involvement of the RAS, P13K-AKT, and YAP/TAZ pathways, which are essential for regulating cell survival, growth, apoptosis, and differentiation under stress. These signaling cascades interconnect in a feedback loop, ensuring a coordinated response. Furthermore, the figure underscores the importance of aquaporins (AQP1 and AQP11) in managing osmotic balance by controlling water and ion transport. Immune responses, inflammation, and apoptosis are also regulated by these pathways to mitigate cellular damage. Collectively, this network of molecular responses allows organisms to adapt to salinity fluctuations, ensuring their survival and maintaining cellular integrity under osmotic stress (

Figure 2).

MAPK Signaling Pathway Response in Aquatic Species Under Salinity Stress

The mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway regulates response to salinity stress by transmitting environmental signals to the nucleus for adaptive changes [

59,

60]. Salinity-induced increases in cytosolic calcium (Ca²⁺) activate the MAPK pathway, leading to the phosphorylation of key proteins involved in stress responses [

61]. For example, in the Scophthalmus maximus p38 MAPK expression is upregulated under high salinity conditions [

59]. Similarly in Lateolabrax maculatus hyperosmotic shock triggers MAPK11 (p38β) expression, further supporting the MAPK pathway role in salinity stress responses [

62]. Additionally, MAPK14a has been linked to oxidative damage in Ictalurus punctatus under extreme salinity stress, highlighting the role of MAPK pathways in managing both osmotic and oxidative stress [

63].

Among MAPK subfamilies, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) plays a prominent role in managing osmotic and oxidative stress, as well as regulating metabolism, inflammation, and apoptosis. For instance, in L. maculatus, JNK activation facilitates osmotic adaptation by regulating mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 (MKK4) [

62]. A similar mechanism is seen in the fish Rachycentron canadum where extreme salinity fluctuations lead to changes in MAPK gene expression particularly in the gills and kidneys, underscoring their involvement in ion transport and osmotic regulation during low salinity stress [

64].

In addition to osmotic stress, salinity combined with elevated carbonate alkalinity activates the MAPK pathway, leading to increased ROS production and apoptosis in E. sinensis [

65]. Similarly, in Penaeus monodon JNK activation regulates MKK4 during low-salinity adaptation [

66]. In Chlamys farreri, JNK expression increases sharply within hours of environmental stress, highlighting the rapid role of JNK in molluscan stress responses [

63].

PI3K-AKT Signaling Pathways in Response to Salinity Stress

The PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, often activated by Ras, plays a vital role in physiological regulation and cellular resilience. In crustaceans, this pathway is integral not only to cellular resilience under stress but also to the innate immune response [

67]. The central components of this pathway, phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) and AKT (protein kinase B) regulate essential cellular processes. For instance they inhibit pro-apoptotic proteins, such as BCL2-antagonist of cell death, and preventing NF- κB nuclear translocation from cells under stress [

68].

In response to low salinity, the PI3K-AKT pathway modulate gene expression and protein synthesis to maintain tissue integrity and remove damaged cells through apoptosis in

S. maximus [

69]. Notably, low-salinity stress downregulates AKT1 phosphorylation and gene expression, particularly in the gill, highlighting tissue-specific responses [

70]. Additionally this pathway mediates the expression of aquaporin genes such as AQP1 and AQP11, the PI3K-AKT pathway facilitates water and ion exchange essential for maintaining osmotic balance in fluctuating environments [

71].

Brain transcriptome profiling analysis of Oreochromis niloticus under prolonged hypersaline stress revealed that the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway plays a key role in the upstream regulation of osmoregulatory processes in response to salinity stress [

72]. Key genes within this pathway, including G protein-coupled receptors and solute carrier families, exhibit differential expression under salinity fluctuations [

73]. Furthermore inhibition of this pathway confirms its pivotal role in modulating ion channel activity, essential for maintaining osmotic balance under stress [

70].

AMPK Signaling Pathway and Energy Regulation in Response to Salinity Stress

AMP-activated protein kinase helps to maintain energy homeostasis by monitoring the AMP/ATP ratio. When this ratios increase, AMPK is activated through phosphorylation at threonine 172 in the AMPKα subunit, triggering metabolic adjustments to restore energy balance [

74]. Under salinity stress, AMPK modulates energy metabolism to address osmotic challenges [

75].

Building on this general mechanism, crustaceans exhibit unique metabolic adaptations under salinity stress. In

Litopenaeus vannamei, salinity stress alters lipid metabolism, influencing fatty acid biosynthesis and glycosphingolipid metabolism to meet energy demands [

76]. In

S. paramamosain, low salinity stress increases the AMP/ATP ratio in the hepatopancreas, thereby enhancing ATP production and upregulating genes involved in glycogen and lipid metabolism. These metabolic changes sustain energy needs during stress and facilitate osmotic pressure regulation [

77].

In addition to crustaceans fish also exhibit AMPK mediated metabolic responses to salinity stress. In

Paralihthys olivaceus, salinity fluctuations activate AMPK through phosphorylation and allosteric AMP binding, leading to increased glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation that provides the necessary energy to manage osmotic challenges [

78]. Similarly in Ctenopharyngodon Idella, activation of AMPK by 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide reduces serum glucose levels and regulates lipogenesis related proteins, effectively reallocating energy resources under stress [

79].

The Role of the Hippo Signaling Pathway in Salinity Stress

The Hippo signaling pathway plays role in maintaining tissue and cellular integrity by integrating environmental cues and regulating cellular processes [

80]. This regulation is vital under stress conditions such as salinity stress, where maintaining cellular homeostasis is essential. In aquatic species such as

L. vannameieus pathway contributes to stress responses and innate immunity [

81]. In bivalves, the pathway normally promotes cell proliferation and anti-apoptotic mechanisms under optimal conditions, however under stress such as salinity stress it shifts towards triggering apoptosis and cell cycle arrest to maintain cellular homeostasis [

82].

Beyond its direct effects, interactions with other signaling pathways further enhance its role in managing environmental stress. Its crosstalk with the Wnt pathway, via β-catenin-mediated gene activation, supports tissue growth and repair. Further interactions with bone morphogenetic proteins and the transforming growth factor-β superfamily are vital for muscle growth and innate immunity in both crustaceans and fish [

83]. The regulation of metabolism and regeneration by YAP/TAZ further emphasizes Hippo’s pivotal role in balancing apoptosis and cell survival during stress and repair. This function is vital for adaptation and resilience in stressful environments [

84]. Together, these mechanisms highlight the pathways pivotal role in enabling adaptive responses to changing salinity conditions in aquatic organisms.

3.5.2. Stress Responsive Genes

Stress-responsive genes play pivotal roles in regulating processes such as osmoregulation, metabolism, immune function, and apoptosis under salinity stress [

85]. Heat shock proteins (HSPs), particularly HSP70 and HSP90, are molecular chaperones that stabilize cellular proteins under osmotic stress. In fish species such as

Luciobarbus capito, high salinity triggers the expression of stress responsive genes including, HSP70 and HSP90 in the spleen, which helps stabilize cellular proteins under osmotic stress [

86].Transcription factors such as Forkhead box O proteins further mediates stress responses by regulating genes involved in stress resistance, metabolism, and apoptosis, enhancing adaptability during osmotic challenges [

87]. In

O. mossambicus the upregulation of Osteoclast Stimulating Factor 1 regulates downstream genes for ion transport and stress response [

85]. Likewise, caspase genes which are key regulators of apoptosis are modulated by salinity stress. In

Takifugu fasciatus, caspase 3, 7, and 9 are upregulated under high salinity, promoting apoptosis, while their expression decreases at moderate salinity, favoring cell survival [

88]. Similar patterns are observed in the

Syngnathus typhle, where salinity stress compromises immune defense [

89]. Cell cycle related genes, such as p53 are activated to promote the proliferation of ionocytes enhancing the ion exchange capacity of gills in response to changing salinity [

90]. This adjustment facilitates the organism's immediate survival under stressful conditions.

In addition to apoptosis regulation, other genes, such as encoding aquaporins (AQPs), play a significant role in osmoregulation during salinity stress. In

L. vannamei, the expression of LvAQP3, LvAQP4, and LvAQP11 decreases across tissues under salinity stress, except in the hepatopancreas, where they facilitate osmoregulation through amino acid metabolism [

91]. Similar to previous reported salinity stress

AQP3 and

AQP4 in

Fenneropenaeus chinensis are downregulated in gills to minimize water loss and regulate ion balance [

92]. These results indicate adaptive role of AQPs in maintaining osmotic and ionic balance.

Beyond water transport metabolic adjustments are essential for energy allocation during salinity stress. In

S. paramamosain, enzymes like citrate synthase are upregulated to enhance energy production through the TCA cycle, while glycogen synthase and hexokinase are downregulated, indicating a shift from energy storage to immediate use [

93]. Lipid metabolism also adopts accordingly, with reduced fatty acid synthesis via fatty acid synthase and increased lipid mobilization to meet energy demands [

94]. Under both hypoosmotic and hyperosmotic conditions, organisms adjust the synthesis and degradation of organic osmolytes to maintain osmotic balance. Enzymes like ornithine decarboxylase are upregulated to boost the production of polyamines, while glutamine synthetase expression is downregulated, fine-tune osmolyte metabolism and support cellular homeostasis [

95].

3.5.3. Epigenetic Modifications Under Salinity Fluctuations

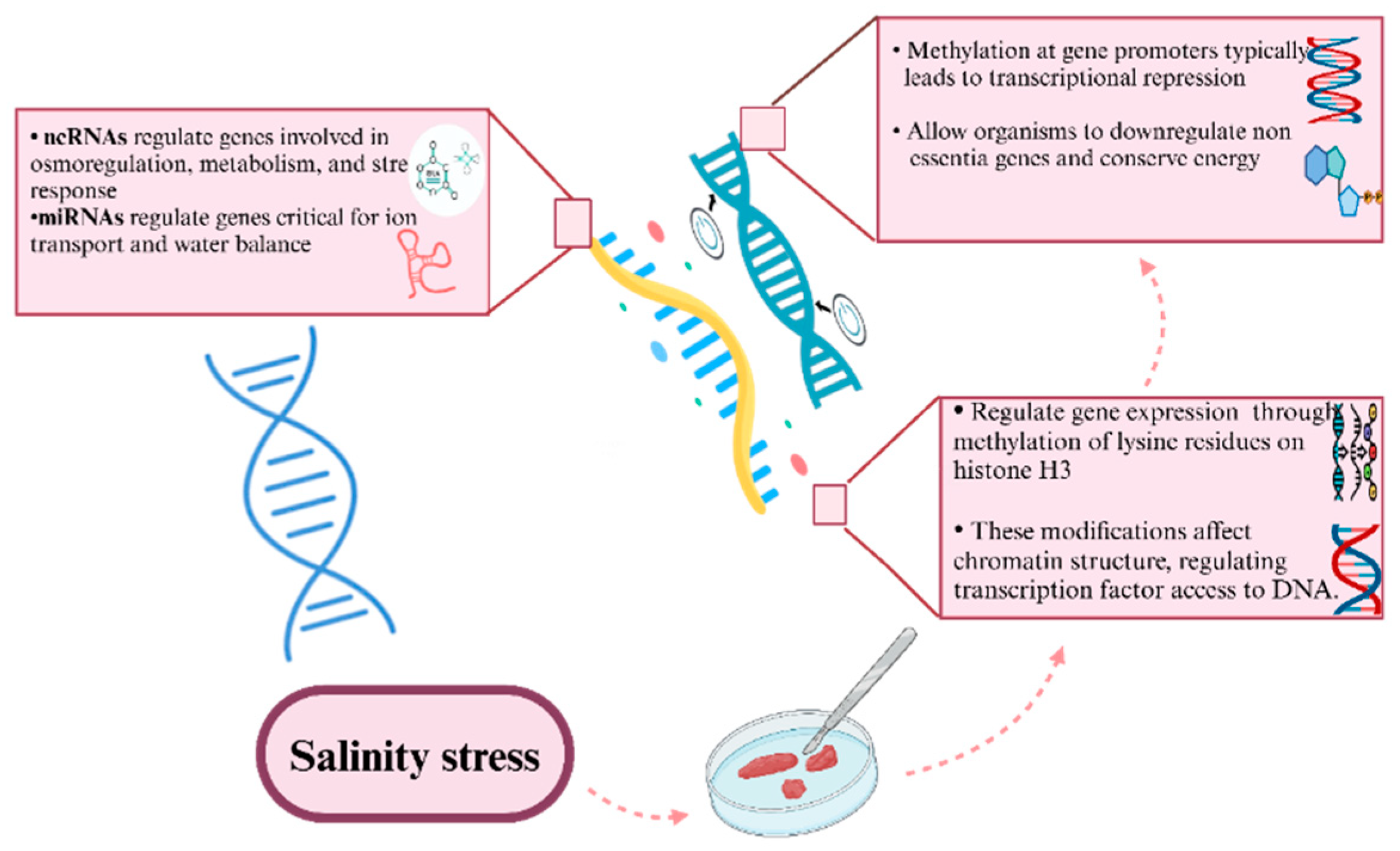

Epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA activities enable organisms to adapt to salinity stress. These heritable molecular changes dynamically regulate gene expression, facilitating both immediate responses and long term resilience to salinity fluctuations without altering the DNA sequence [

96]. By modulating gene activity, epigenetic mechanisms help organisms cope with environmental changes in ways that are heritable and adaptive over time.

Figure 3 illustrates the critical role of epigenetic modifications and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in regulating gene expression in response to salinity stress. Non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs), regulate genes involved in osmoregulation, metabolism, and stress response, particularly those crucial for ion transport and water balance. These ncRNAs enable organisms to fine-tune gene expression in response to fluctuating salinity levels, ensuring optimal survival. Additionally, DNA methylation at gene promoters typically leads to transcriptional repression, allowing organisms to downregulate non-essential genes and conserve energy, especially under stress conditions. Histone modifications, such as the methylation of lysine residues on histone H3, further regulate gene expression by altering chromatin structure, thus controlling the accessibility of transcription factors to DNA. Together, these epigenetic mechanisms enable organisms to efficiently adapt to salinity stress, maintaining essential physiological functions while minimizing energy expenditure on non-critical processes.

In the context of salinity fluctuations, studies have shown that low salinity induces tissue-specific methylation changes in organisms. For instance in Portunus trituberculatus, low salinity increases methylation in gill tissues, while decreasing it in muscle and gills [

97]. Likewise, in Crassostrea gigas, salinity fluctuations leads to DNA methylation changes in genes associated with nucleic acid metabolism, tropomyosin, and cellular transport, highlighting the role of these modifications in osmoregulatory adaptation [

98].

In addition to DNA methylation, histone modifications and non-coding RNAs also contribute to osmoregulatory responses. In Daphnia magna, miRNAs are involved in transgenerational inheritance of salinity tolerance, where sustained hypomethylation of stress-relevant genes persists across generations [

99]. Such epigenetic memory prepares offspring for similar environmental challenges, highlighting the evolutionary significance of these mechanisms.

In some marine fish species low salinity triggers distinct epigenetic response. Likewise, prolonged exposure to low salinity in

Cynoglossus semilaevis, alters H3K4me3 patterns influencing growth and liver structure. It also upregulates demethylase genes and DNA methyltransferases, enhancing methylation in renal tissues and regulating immune-related genes like

MASP1 to balance energy use and immune responses under stress [

100]. These studies indicate that epigenetic modifications enable organisms to adaptively respond to environmental stressors like salinity fluctuations, ensuring both immediate and long-term survival by synchronizing physiological and metabolic processes across generations.

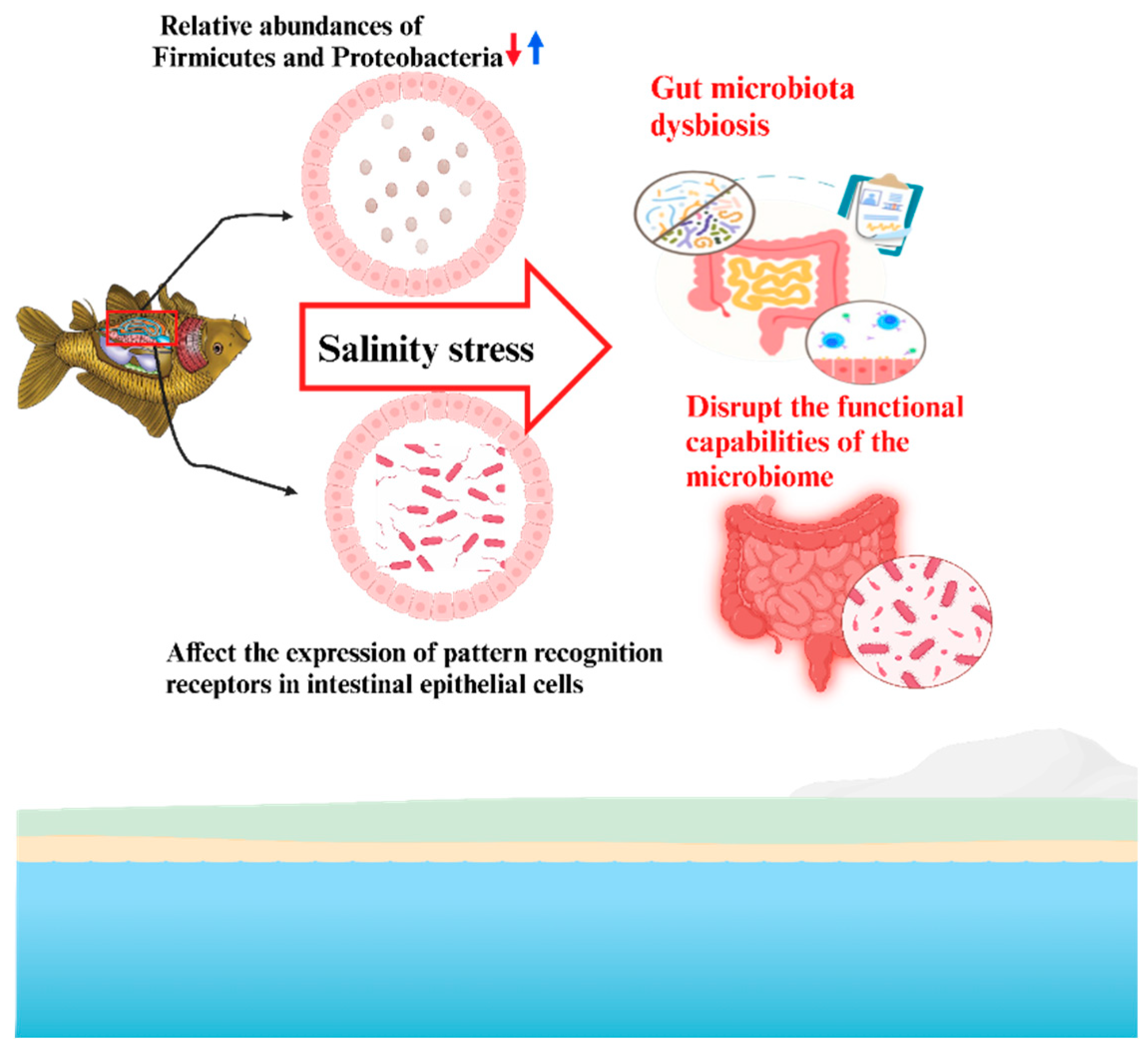

4. Microbiome Interactions and Response Under Salinity Stress

Host-microbiome interactions play significant role in salinity tolerance as the gut microbiota perform a role in metabolism, immune regulation, and disease resistance [

101]. Changes in salinity can lead to shift in microbial community composition often favoring opportunistic microbial taxa like

Proteobacteria and

Vibrio spp. under higher salinity conditions, while lower salinity tend to favors beneficial bacteria such as

Actinobacteria and

Lactobacillus [

102]. These shifts have been observed across various species, demonstrating the broader impact of salinity on microbiome health. For instance, in fish species like

Gambusia and Paracheirodon

sphenops, salinity variations disrupted their gut microbiome, adversely impacting their health [

103]. Similarly, in the

Nibea albiflora extreme salinity favors harmful

Vibrio, while intermediate salinities promoted probiotic taxa that enhanced immunity and growth [

104]. Conversely in the

Coilia nasus, salinity mitigation reduces harmful bacteria (

Escherichia coli and

Aeromonas) while promoting beneficial taxa like

Actinobacteria and

Corynebacterial [

105]. These studies highlight the dynamic role of microbiomes in responding to salinity stress.

Salinity stress also disrupts gut microbial taxa and metabolic functions across different fish species. For instance, in

Micropterus salmoides, the abundance of

Bacillus increases at 10‰ salinity, and microbial adaptation was enhanced at 15‰ salinity [

106]. In Salmo salar, freshwater habitats promotes higher abundances of

Firmicutes,

Actinobacteria, and

Fusobacteria, while seawater favors

Proteobacteria and

Bacteroidetes [

107].These studies indicates that microbial responses to salinity vary significantly across species and environments.

Microbial dysbiosis induced by salinity stress has been directly linked to compromised immune homeostasis and intestinal health in various species. Likewise, In L. vannamei, hypoosmotic conditions led to Vibrio overgrowth, reduced microbial richness, and altered lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis [

12]. Similarly, in mud crabs, salinity fluctuations increased intestinal permeability, promoted pathogen translocation, and activated inflammatory pathways, exacerbating microbial imbalance [

108].

Figure 4 demonstrates how salinity stress induces changes in the gut microbiota of aquatic organisms, leading to gut microbiota dysbiosis. Under fluctuating salinity conditions, the microbial composition in the gut becomes imbalanced, with beneficial microbes potentially decreasing and less beneficial or harmful microbes increasing. This dysbiosis disrupts the functional capabilities of the microbiome, impairing essential processes such as nutrient absorption, immune system regulation, and overall gut health. The figure highlights that these disruptions can compromise the organism's ability to adapt to salinity stress, potentially affecting its survival and physiological functions. Overall, this underscores the critical role of a balanced microbiome in maintaining the health and stress resilience of aquatic organisms exposed to changing salinity environments.

At the molecular level, salinity-induced microbiome shifts modulate the expression of stress response genes, antimicrobial peptides, and the prophenoloxidase system, thereby influencing how invertebrates maintain intestinal homeostasis [

109]. Under low salinity, structural proteins such as mucins and peritrophins are upregulated, fortifying the intestinal barrier and favoring beneficial taxa [

110]. However, hypoosmotic conditions also elevate oxidative stress markers, which can damage intestinal tissues and further disrupt host-microbiome interactions [

111].Thus, Salinity stress significantly alters host-microbiome interactions by shifting microbial community composition, disrupting metabolic functions, and compromising immune and intestinal homeostasis, ultimately impacting host health and stress tolerance.

5. Genetic Diversity and Resilience of Aquatic Species

Genetic diversity plays a key role in the resilience of aquatic species, especially in relation to fluctuating environmental conditions like salinity changes, which are often associated with climate change. Species with greater genetic diversity are better equipped to adapt to these changes, as they possess a wider range of traits that can enhance survival under variable conditions [

38]. In a similar way Portunus armatus displays tolerance to both elevated temperatures and salinity levels, further highlighting the role of genetic traits in supporting resilience [

112]. These results demonstrate how genetic diversity contributes to the ability of species to adapt to salinity fluctuations.

However, extreme variations in salinity can negatively impact genetic diversity. For example, shifts in salinity have been linked to noticeable changes in the genetic structure of

Artemia populations, leading to a decline in their diversity [

113]. This highlights the negative impact that drastic environmental changes can have on genetic stability, which in turn affects the resilience of populations. Despite this, species with higher genetic diversity tend to far better under fluctuating conditions, underlining the importance of maintaining genetic variation for adaptive capacity [

114].

Salinity also influences population structure and gene flow within aquatic species. For example, the salinity barrier created by the Amazon-Orinoco plume causes genetic differences between Atlantic fiddler crabs populations from the Caribbean and Brazil, showing how environmental factors can separate populations and limit gene flow [

115]. On the other hand, the more adaptable

Callinectes danae exhibits less genetic differentiation and more gene flow, indicating its ability to better cope with salinity fluctuations [

116]. This comparison highlights the differential adaptability of species to salinity fluctuations, emphasizing the subsequent effects on genetic diversity.

Hybridization studies on

tilapia show that hybrid fish have faster growth rates and greater tolerance to salinity fluctuations compared to their purebred counterparts, demonstrating how hybridization can increase genetic diversity and improve the ability to cope with environmental stress [

117]. In addition, Esox lucius fish populations have evolved flexible reproductive strategies, with certain fish species able to produce more embryos in saline environments than their freshwater counterparts, further enhancing their ability to survive in variable habitats [

118]. These reproductive adaptations are another way genetic diversity supports resilience in dynamic environments. Future research should focus on evaluating the long-term evolutionary impacts of hybridization on population genetics, particularly the persistence of hybrid vigor and the potential for genetic assimilation over multiple generations.

6. Strategies for Mitigating Salinity Stress in Aquatic Organisms

Effective strategies to mitigate salinity stress in aqua cultural systems include nutritional interventions and development of salinity tolerant strains.

6.1. Nutritional Intervention

Dietary adjustments play a key role in enhancing osmoregulatory efficiency and stress resilience. For example, in

L. vannamei protein requirements increase under higher salinities to optimize growth and osmoregulatory functions [

119]. Supplementing with essential amino acids, such as methionine and tryptophan further supports physiological stability under salinity stress [

120]. In addition to proteins, lipid metabolism also supports energy demands for osmoregulation. Supplementing the diet with lipids enhances energy availability and osmoregulatory functions in shrimps, especially when bile salt production is insufficient [

121]. Furthermore, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids enhance growth and immune responses in shrimp offering another strategy for mitigating salinity stress [

122]. Other key nutrients such as myo inositol, choline, and Vitamin D3, improve antioxidative function, thereby boost salinity stress resilience in

L. vannamei [

123]. Carotenoids, including astaxanthin, further enhance osmotic stress resistance in crustaceans, strengthening their ability to cope with salinity fluctuations [

124]. Additionally increased calcium levels shorten molt intervals and accelerate exoskeletal calcification, optimizing crab production [

125]. These results highlight the importance of a balanced diet, including proteins, lipids, vitamins, and minerals, in supporting osmoregulatory function and maintaining the health of aquatic species under fluctuating salinity conditions.

In species like

O. niloticu, salinity induced morphological changes in the intestine can disrupt nutrient absorption, highlighting the need for a tailored amino acid profile to sustain protein digestibility [

126]. Fish populations also require flexible reproductive strategies to thrive in saline environments. Supplementation with essential fatty acids, such as DHA, has been shown to improve salinity tolerance in fish larvae [

127]. Furthermore, carbohydrates can act as protein-sparing agents under metabolic stress in fish, improving overall nutrient utilization [

3]. For example, diets containing 15–20% carbohydrates benefit fish in osmoregulatory processes [

128]. Collectively, these nutritional strategies, which combine essential fatty acids, carbohydrates, and vitamins, are essential for optimizing the health and performance of aquatic species in environments with fluctuating salinity.

6.2. Development of Salinity Resistant Varieties

Selective breeding has emerged as a promising strategy to enhance salinity tolerance in aquatic species. For instance, the Sukamandi strain of tilapia, a hybrid between

O. niloticus and

O. aureus, demonstrates increased salinity tolerance through gene introgression from

O. aureus. Selective breeding for these traits has reinforced the salinity tolerance of this strain, making it better suited for environments with fluctuating salinity levels [

45]. Similarly, selective breeding programs targeting P. hypophthalmus have successfully enhanced growth and survival in saline environments [

129]. In shrimp aquaculture, the identification of genetic markers linked to salinity tolerance has facilitated the distinction between salinity-tolerant families and those more susceptible to environmental stress. This enables more efficient selection of brood stock with inherent salinity-resistant traits, improving the overall effectiveness of breeding programs aimed at enhancing resilience to salinity fluctuations [

130].

7. Conclusion and Shortcomings

Salinity stress is a significant environmental factor that shapes aquatic ecosystems, influencing species distribution and altering biodiversity. The capacity of species to adapt and tolerate salinity fluctuations through diverse physiological, behavioral, and molecular mechanisms is critical for maintaining ecosystem stability and resilience. Genetic diversity plays a fundamental role in allowing populations to cope with changing salinity, ensuring long-term survival and adaptability. Furthermore, the intricate relationships between aquatic organisms and their microbiomes under salinity stress underscore the importance of microbial balance for overall health and resilience. Strategies such as nutritional interventions and the selective breeding of salinity-resistant strains show promise for improving the tolerance of aquaculture species and preserving biodiversity in natural habitats. Despite significant progress in understanding the effects of salinity stress, several research gaps hinder a comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon. These gaps include the lack of detailed species-specific responses to both acute and chronic salinity fluctuations, insufficient long-term ecological studies to predict cumulative effects over time, and limited knowledge regarding the interactive effects of salinity with other environmental stressors such as temperature and pollution. Additionally, the molecular mechanisms underlying behavioral adaptations to salinity changes remain inadequately explored, and comparative data on ion transport mechanisms across diverse species is sparse. The long-term effects and heritability of epigenetic changes in response to salinity stress require further investigation to assess their potential for transgenerational adaptation. Finally, the impact of reduced genetic diversity on population tolerance, particularly in the context of rapid climate change, necessitates deeper exploration. Addressing these shortcomings is vital for developing a more comprehensive understanding of salinity stress and for implementing effective strategies to protect aquatic ecosystems amid increasing environmental variability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.D. and H.M.; methodology: T.D. and H.M.; validation: T.D., W.C., M.I. and H.M.; formal analysis: T.D. and H.M.; investigation: T.D., W.C. and H.M.; data curation: T.D., W.C., M.I. and H.M.; writing—original draft preparation: T.D.; writing—review and editing: W.C., M.I. and H.M.; visualization: H.M.; supervision: H.M.; project administration: H.M.; funding acquisition: H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32473150), the Program of Agricultural and Rural Department of Guangdong Province (2024-SPY-00-013), and the Science and Technology Project of Guangdong Province (STKJ202209029).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gattoni, K.; Gendron, E.M.S.; Borgmeier, A.; McQueen, J.P.; Mullin, P.G.; Powers, K.; Powers, T.O.; Porazinska, D.L. Context-Dependent Role of Abiotic and Biotic Factors Structuring Nematode Communities along Two Environmental Gradients. Mol. Ecol. 2022, 31, 3903–3916. [CrossRef]

- Brauner, C.J.; Gonzalez, R.J.; Wilson, J.M. Extreme Environments: Hypersaline, Alkaline, and Ion-Poor Waters. Fish Physiology 2012; 32, 435–476.

- Seale, A.P.; Cao, K.; Chang, R.J.A.; Goodearly, T.R.; Malintha, G.H.T.; Merlo, R.S.; Peterson, T.L.; Reighard, J.R. Salinity Tolerance of Fishes: Experimental Approaches and Implications for Aquaculture Production. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 1351–1373. [CrossRef]

- McNamara, J.C.; Faria, S.C. Evolution of Osmoregulatory Patterns and Gill Ion Transport Mechanisms in the Decapod Crustacea: A Review. J. Comp. Physiol. B Biochem. Syst. Environ. Physiol. 2012, 182, 997–1014. [CrossRef]

- Anger, K. Neotropical Macrobrachium (Caridea: Palaemonidae):On the Biology, Origin, and Radiation of Freshwater-Invading Shrimp. J. Crustac. Biol. 2013, 33, 151–183.

- Xu, W. Bin; Zhang, Y.M.; Li, B.Z.; Lin, C.Y.; Chen, D.Y.; Cheng, Y.X.; Guo, X.L.; Dong, W.R.; Shu, M.A. Effects of Low Salinity Stress on Osmoregulation and Gill Transcriptome in Different Populations of Mud Crab Scylla Paramamosain. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 867, 161–522. [CrossRef]

- Bal, A.; Panda, F.; Pati, S.G.; Das, K.; Agrawal, P.K.; Paital, B. Modulation of Physiological Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Status by Abiotic Factors Especially Salinity in Aquatic Organisms: Redox Regulation under Salinity Stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part - C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 241, 108–971.

- Pini, J.; Planes, S.; Rochel, E.; Lecchini, D.; Fauvelot, C. Genetic Diversity Loss Associated to High Mortality and Environmental Stress during the Recruitment Stage of a Coral Reef Fish. Coral Reefs 2011, 30, 399–404. [CrossRef]

- Leeuwis, R.H.J.; Gamperl, A.K. Adaptations and Plastic Phenotypic Responses of Marine Animals to the Environmental Challenges of the High Intertidal Zone. Oceanography and Marine Biology 2022, 625–679.

- Rivera-Ingraham, G.A.; Barri, K.; Boël, M.; Farcy, E.; Charles, A.-L.; Geny, B.; Lignot, J.-H. Osmoregulation and Salinity-Induced Oxidative Stress: Is Oxidative Adaptation Determined by Gill Function? J. Exp. Biol. 2016, 219, 80–89. [CrossRef]

- Chaiyapechara, S.; Uengwetwanit, T.; Arayamethakorn, S.; Bunphimpapha, P.; Phromson, M.; Jangsutthivorawat, W.; Tala, S.; Karoonuthaisiri, N.; Rungrassamee, W. Understanding the Host-Microbe-Environment Interactions: Intestinal Microbiota and Transcriptomes of Black Tiger Shrimp Penaeus Monodon at Different Salinity Levels. Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737371. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-T.; Huang, W.-T.; Wu, P.-L.; Kumar, R.; Wang, H.-C.; Lu, H.-P. Low Salinity Stress Increases the Risk of Vibrio Parahaemolyticus Infection and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Pacific White Shrimp. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 275. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Gao, Q.; Sun, C.; Song, C.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Q.; Zheng, X.; Liu, X. Response of Microbiota and Immune Function to Different Hypotonic Stress Levels in Giant Freshwater Prawn Macrobrachium Rosenbergii Post-Larvae. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 157258. [CrossRef]

- Röthig, T.; Trevathan-Tackett, S.M.; Voolstra, C.R.; Ross, C.; Chaffron, S.; Durack, P.J.; Warmuth, L.M.; Sweet, M. Human-induced Salinity Changes Impact Marine Organisms and Ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2023, 29, 4731–4749. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Gu, Y.Y.; Zhang, Z.M.; Sun, A.L.; Shi, X.Z.; Chen, J.; Lu, Y. Contaminant Occurrence, Mobility and Ecological Risk Assessment of Phthalate Esters in the Sediment-Water System of the Hangzhou Bay. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 144705. [CrossRef]

- Tweedley, J.R.; Dittmann, S.R.; Whitfield, A.K.; Withers, K.; Hoeksema, S.D.; Potter, I.C. Hypersalinity: Global Distribution, Causes, and Present and Future Effects on the Biota of Estuaries and Lagoons. Coasts and Estuaries 2019, 523–546.

- Telesh, I. V.; Khlebovich, V. V. Principal Processes within the Estuarine Salinity Gradient: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 61, 149–155. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.A.; Cobos, M.; Magaña, P.J.; Díez-Minguito, M. Sensitivity of Iberian Estuaries to Changes in Sea Water Temperature, Salinity, River Flow, Mean Sea Level, and Tidal Amplitudes. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2020, 236, 106624. [CrossRef]

- Day, J.W.; Crump, B.C.; Kemp, W.M.; Yáñez-Arancibia, A. Introduction to Estuarine Ecology. Estuar. Ecol. 2012, 1–18.

- Iglesias, M.C.-A. A Review of Recent Advances and Future Challenges in Freshwater Salinization. Limnetica 2020, 39, 185–211.

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, L.; Ye, J.; Wang, L.; Huang, K.; Zhai, Q. Effects of Acute Salinity Stress on the Serum Osmolality, Serum Ion Concentrations, and ATPase Activity in Gill Filaments of Japanese Seabass(Lateolabrax Japonicus) Fed with Diets Containing Different Magnesium Levels. J. Fish. China 2012, 36, 1425. [CrossRef]

- Getz, E.; Eckert, C. Effects of Salinity on Species Richness and Community Composition in a Hypersaline Estuary. Estuaries and Coasts 2023, 46, 2175–2189. [CrossRef]

- Balushkina, E. V.; Golubkov, S.M.; Golubkov, M.S.; Litvinchuk, L.F.; Shadrin, N. V. Effect of Abiotic and Biotic Factors on the Structural and Functional Organization of the Saline Lake Ecosystems. Zh. Obshch. Biol. 2009, 70, 504–514.

- Gutiérrez, J.S. Living in Environments with Contrasting Salinities: A Review of Physiological and Behavioural Responses in Waterbirds. Ardeola 2014, 61, 233–256. [CrossRef]

- Strang, C.I.; Bosker, T. The Impact of Climate Change on Marine Mega-Decapod Ranges: A Systematic Literature Review. Fish. Res. 2024, 280, 107165. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Xie, Z.; Lan, Y.; Dupont, S.; Sun, M.; Cui, S.; Huang, X.; Huang, W.; Liu, L.; Hu, M.; et al. Short-Term Exposure of Mytilus Coruscus to Decreased PH and Salinity Change Impacts Immune Parameters of Their Haemocytes. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 166. [CrossRef]

- Ivanina, A. V.; Jarrett, A.; Bell, T.; Rimkevicius, T.; Beniash, E.; Sokolova, I.M. Effects of Seawater Salinity and PH on Cellular Metabolism and Enzyme Activities in Biomineralizing Tissues of Marine Bivalves. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. -Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2020, 248, 110748. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, N.J.; Thyrring, J.; Harper, E.M.; Sejr, M.K.; Sørensen, J.G.; Peck, L.S.; Clark, M.S. Molecular Responses to Thermal and Osmotic Stress in Arctic Intertidal Mussels (Mytilus Edulis): The Limits of Resilience. Genes 2022, 13,155. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.W.; DeBiasse, M.B.; Villela, V.A.; Roberts, H.L.; Cecola, C.F. Adaptation to Climate Change: Trade-offs among Responses to Multiple Stressors in an Intertidal Crustacean. Evol. Appl. 2016, 9, 1147–1155. [CrossRef]

- Sohaib Ahmed Saqib, H.; Yuan, Y.; Shabi Ul Hassan Kazmi, S.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Ma, H. Salinity Gradients Drove the Gut and Stomach Microbial Assemblages of Mud Crabs (Scylla Paramamosain) in Marine Environments. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151, 110315. [CrossRef]

- Shields, J.D. Climate Change Enhances Disease Processes in Crustaceans: Case Studies in Lobsters, Crabs, and Shrimps. J. Crustac. Biol. 2019, 39, 673–683. [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.G.; Kültz, D. The Cellular Stress Response in Fish Exposed to Salinity Fluctuations. J. Exp. Zool. Part A Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 2020, 333, 421–435. [CrossRef]

- Kültz, D. Physiological Mechanisms Used by Fish to Cope with Salinity Stress. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 1907–1914. [CrossRef]

- Losee, J.P.; Palm, D.; Claiborne, A.; Madel, G.; Persson, L.; Quinn, T.P.; Brodin, T.; Hellström, G. Anadromous Trout from Opposite Sides of the Globe: Biology, Ocean Ecology, and Management of Anadromous Brown and Cutthroat Trout. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2024, 34, 461–490. [CrossRef]

- Yancey, P.H.; Siebenaller, J.F. Co-Evolution of Proteins and Solutions: Protein Adaptation versus Cytoprotective Micromolecules and Their Roles in Marine Organisms. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 1880–1896. [CrossRef]

- Glover, C.N.; Wood, C.M.; Goss, G.G. Drinking and Water Permeability in the Pacific Hagfish, Eptatretus Stoutii. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2017, 187, 1127–1135. [CrossRef]

- Jaffer, Y.D.; Bhat, I.A.; Mir, I.N.; Bhat, R.A.H.; Sidiq, M.J.; Jana, P. Adaptation of Cultured Decapod Crustaceans to Changing Salinities: Physiological Responses, Molecular Mechanisms and Disease Implications. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 1520–1543. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, I.; de Carvalho-Souza, G.F.; González-Ortegón, E. Physiological Responses of the Invasive Blue Crabs Callinectes Sapidus to Salinity Variations: Implications for Adaptability and Invasive Success. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2024, 297, 111709. [CrossRef]

- Tietze, S.M.; Gerald, G.W. Trade-Offs between Salinity Preference and Antipredator Behaviour in the Euryhaline Sailfin Molly Poecilia Latipinna. J. Fish Biol. 2016, 88, 1918–1931. [CrossRef]

- Turko, A.J.; Earley, R.L.; Wright, P.A. Behaviour Drives Morphology: Voluntary Emersion Patterns Shape Gill Structure in Genetically Identical Mangrove Rivulus. Anim. Behav. 2011, 82, 39–47. [CrossRef]

- Chow, S.C.; Ching, L.Y.; Wong, A.M.F.; Wong, C.K.C. Cloning and Regulation of Expression of the Na+-Cl- -Taurine Transporter in Gill Cells of Freshwater Japanese Eels. J. Exp. Biol. 2009, 212, 3205–3210.

- Edwards, S.L.; Marshall, W.S. Principles and Patterns of Osmoregulation and Euryhalinity in Fishes. Fish Physiology 2012, 32, 1–44.

- Breves, J.P.; Hasegawa, S.; Yoshioka, M.; Fox, B.K.; Davis, L.K.; Lerner, D.T.; Takei, Y.; Hirano, T.; Grau, E.G. Acute Salinity Challenges in Mozambique and Nile Tilapia: Differential Responses of Plasma Prolactin, Growth Hormone and Branchial Expression of Ion Transporters. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 167, 135–142. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ni, J.; Niu, D.; Zheng, G.; Li, Y. Physiological Response of the Razor Clam Sinonovacula Constricta Exposed to Hyposalinity Stress. Aquac. Fish. 2024, 9, 663–673. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, Y. Effects of Salinity Stress on Osmotic Pressure, Free Amino Acids, and Immune-Associated Parameters of the Juvenile Chinese Mitten Crab, Eriocheir Sinensis. Aquaculture 2022, 549, 737776. [CrossRef]

- Zikos, A.; Seale, A.P.; Lerner, D.T.; Grau, E.G.; Korsmeyer, K.E. Effects of Salinity on Metabolic Rate and Branchial Expression of Genes Involved in Ion Transport and Metabolism in Mozambique Tilapia (Oreochromis Mossambicus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2014, 178, 121–131. [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.R.; Richards, J.G.; Forbush, B.; Isenring, P.; Schulte, P.M. Changes in Gene Expression in Gills of the Euryhaline Killifish Fundulus Heteroclitus after Abrupt Salinity Transfer. Am. J. Physiol. - Cell Physiol. 2004, 287, C300–C309. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Meng, Q.; Sun, R.; Xu, D.; Zhu, F.; Jia, C.; Zhou, S.; Chen, S.; Yang, Y. Structure and Gene Expression Changes of the Gill and Liver in Juvenile Black Porgy (Acanthopagrus Schlegelii) under Different Salinities. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 2024, 50, 101228. [CrossRef]

- Blondeau-Bidet, E.; Tine, M.; Gonzalez, A.-A.; Guinand, B.; Lorin-Nebel, C. Coping with Salinity Extremes: Gill Transcriptome Profiling in the Black-Chinned Tilapia (Sarotherodon Melanotheron). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172620. [CrossRef]

- Waqas, W.; Yuan, Y.; Ali, S.; Zhang, M.; Shafiq, M.; Ali, W.; Chen, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Chen, R.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; et al. Toxic Effects of Heavy Metals on Crustaceans and Associated Health Risks in Humans: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 1391–1411. [CrossRef]

- Hoseinifar, S.H.; Yousefi, S.; Van Doan, H.; Ashouri, G.; Gioacchini, G.; Maradonna, F.; Carnevali, O. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense in Fish: The Implications of Probiotic, Prebiotic, and Synbiotics. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2020, 29, 198–217. [CrossRef]

- Paital, B.; Chainy, G.B.N. Antioxidant Defenses and Oxidative Stress Parameters in Tissues of Mud Crab (Scylla Serrata) with Reference to Changing Salinity. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. - C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 151, 142–151. [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Q.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, Z. Effects of Different Salinity Reduction Intervals on Osmoregulation, Anti-Oxidation and Apoptosis of Eriocheir Sinensis Megalopa. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2024, 291, 111593. [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Shin, H.S.; Choi, C.Y.; Kim, N.N.; Park, D.W.; Kil, G.S.; Lee, J. Effect of Hypoosmotic and Thermal Stress on Gene Expression and the Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes in the Cinnamon Clownfish, Amphiprion Melanopus. Animal Cells Syst. 2011, 15, 219–225. [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, M.; Delisle, L.; Petton, B.; Corporeau, C.; Pernet, F. Metabolism of the Pacific Oyster, Crassostrea Gigas, Is Influenced by Salinity and Modulates Survival to the Ostreid Herpesvirus OsHV-1. Biol. Open 2018, 7, 28134. [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, A.; Gostyukhina, O.; Gavruseva, T.; Sigacheva, T.; Tkachuk, A.; Podolskaya, M.; Chelebieva, E.; Kladchenko, E. Mediterranean Mussels (Mytilus Galloprovincialis) Under Salinity Stress: Effects on Antioxidant Capacity and Gill Structure. J. Exp. Zool. Part A Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 2024, 343, 184–196. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Mayer, M.; Rivera-Ingraham, G.; Blondeau-Bidet, E.; Wu, W.Y.; Lorin-Nebel, C.; Lee, T.H. Effects of Temperature and Salinity on Antioxidant Responses in Livers of Temperate (Dicentrarchus Labrax) and Tropical (Chanos Chanos) Marine Euryhaline Fish. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 99, 103016. [CrossRef]

- Bayir, A.; Sirkecioglu, A.N.; Bayir, M.; Haliloglu, H.I.; Kocaman, E.M.; Aras, N.M. Metabolic Responses to Prolonged Starvation, Food Restriction, and Refeeding in the Brown Trout, Salmo Trutta: Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defenses. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. - B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 159, 191–196. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Huang, W.; Wang, G.; Sun, H.; Chen, X.; Luo, P.; Liu, J.; Hu, C.; Li, H.; Shu, H. Identification and Characterization of P38MAPK in Response to Acute Cold Stress in the Gill of Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus Vannamei). Aquac. Reports 2020, 17, 100365. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Xu, X.W.; Zechen, E.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S. Genome-Wide Identification of the MAPK Gene Family in Turbot and Its Involvement in Abiotic and Biotic Stress Responses. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1005401. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Eun, H.S.; Ho, S.K.; Jae, H.Y.; Hay, J.H.; Mi, S.J.; Sang, M.L.; Kyung, E.K.; Min, C.K.; Moo, J.C.; et al. Regulation of MAPK Phosphatase 1 (AtMKP1) by Calmodulin in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 23581–23588.

- Tian, Y.; Wen, H.; Qi, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Identification of Mapk Gene Family in Lateolabrax Maculatus and Their Expression Profiles in Response to Hypoxia and Salinity Challenges. Gene 2019, 684, 20–29. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Zhong, L.; Liu, J.; Bian, W.; Zhang, S. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Genes in Response to Salinity Stress in Channel Catfish (Ictalurus Punctatus). J. Fish Biol. 2022, 101, 972–984. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Jin, S.; Huang, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G. Identification of Mapk Genes, and Their Expression Profiles in Response to Low Salinity Stress, in Cobia (Rachycentron Canadum). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part - B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 271, 110950. [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Examination of the Relationship of Carbonate Alkalinity Stress and Ammonia Metabolism Disorder-Mediated Apoptosis in the Chinese Mitten Crab, Eriocheir Sinensis: Potential Involvement of the ROS/MAPK Signaling Pathway. Aquaculture 2024, 579, 740179. [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Liang, G.; Wei, H.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Mu, C.; Liu, S. Involvement of the JNK Signaling Pathway in Regulating Yolk Accumulation in the Swimming Crab, Portunus Trituberculatus. Aquaculture 2022, 551, 737890. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.S.L.; Cui, W. Proliferation, Survival and Metabolism: The Role of PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signalling in Pluripotency and Cell Fate Determination. Development 2016, 143, 3050–3060. [CrossRef]

- Le, O.T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.N.; Lee, S.Y. Phosphoinositide Turnover in Toll-like Receptor Signaling and Trafficking. BMB Rep. 2014, 47, 361–368. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gan, L.; Li, T.; Xu, C.; Chen, K.; Wang, X.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L.; Li, E. Transcriptome Profiling and Molecular Pathway Analysis of Genes in Association with Salinity Adaptation in Nile Tilapia Oreochromis Niloticus. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0136506. [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Ma, A.; Wang, X. Response of the PI3K-AKT Signalling Pathway to Low Salinity and the Effect of Its Inhibition Mediated by Wortmannin on Ion Channels in Turbot Scophthalmus Maximus. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 2676–2686. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.C.; Chu, K.F.; Yang, W.K.; Lee, T.H. Na+, K+-ATPase Β1 Subunit Associates with A1 Subunit Modulating a “Higher-NKA-in-Hyposmotic Media” Response in Gills of Euryhaline Milkfish, Chanos Chanos. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2017, 187, 995–1007.

- Liu, Y.; Li, E.; Xu, C.; Su, Y.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L.; Wang, X. Brain Transcriptome Profiling Analysis of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus) under Long-Term Hypersaline Stress. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 219. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, Z.; Gao, T.; Song, N. Transcriptome Profiling Reveals a Divergent Adaptive Response to Hyper-and Hypo-Salinity in the Yellow Drum, Nibea Albiflora. Animals 2021, 11, 2201.

- Hardie, D.G.; Ross, F.A.; Hawley, S.A. AMPK: A Nutrient and Energy Sensor That Maintains Energy Homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 251–262. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.D.; Si, M.R.; Jiang, S.G.; Yang, Q. Bin; Jiang, S.; Yang, L.S.; Huang, J.H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, F.L.; Li, E.C. Transcriptome and Molecular Regulatory Mechanisms Analysis of Gills in the Black Tiger Shrimp Penaeus Monodon under Chronic Low-Salinity Stress. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1118341. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, E.; Li, T.; Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Lin, H.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L. Transcriptome and Molecular Pathway Analysis of the Hepatopancreas in the Pacific White Shrimp Litopenaeus Vannamei under Chronic Low-Salinity Stress. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0131503. [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Luo, J.; Zhu, T.; Fang, F.; Xie, S.; Lu, J.; Betancor, M.B.; Tocher, D.R.; Zhou, Q. Examination of Role of the AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (Ampk) Signaling Pathway during Low Salinity Adaptation in the Mud Crab, Scylla Paramamosain, with Reference to Glucolipid Metabolism. Aquaculture 2024, 593, 741329. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Nie, M.; Wang, L.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Xiao, P.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Y.; You, F. Energy Response and Modulation of AMPK Pathway of the Olive Flounder Paralichthys Olivaceus in Low-Temperature Challenged. Aquaculture 2018, 484, 205–213. [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Kuang, S.; Li, S.; Tang, L.; Tang, W.; Zhou, X.; et al. Dietary Vitamin A Improved the Flesh Quality of Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon Idella) in Relation to the Enhanced Antioxidant Capacity through Nrf2/Keap 1a Signaling Pathway. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 148.

- Misra, J.R.; Irvine, K.D. The Hippo Signaling Network and Its Biological Functions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 65–87. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Cui, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, Y. Aquaporins in Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus Vannamei): Molecular Characterization, Expression Patterns, and Transcriptome Analysis in Response to Salinity Stress. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 817868. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Z.-A.; Geng, R.; Deng, H.; Niu, S.; Zuo, H.; Weng, S.; He, J.; Xu, X. White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV) Inhibits Hippo Signaling and Activates Yki To Promote Its Infection in Penaeus Vannamei . Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e02363-22. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Guo, J.; Cheng, X.; Li, W.; Lyu, S.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, H. Molecular Evolution of Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) Gene Family and the Functional Characterization of Lamprey TGF-Β2. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 836226. [CrossRef]

- Riley, S.E.; Feng, Y.; Hansen, C.G. Hippo-Yap/Taz Signalling in Zebrafish Regeneration. npj Regen. Med. 2022, 7,9. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, Y.; Bao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yang, B.; Jiao, L.; Zhang, C.; Tocher, D.R.; Zhou, Q.; Jin, M. Physiological Responses and Adaptive Strategies to Acute Low-Salinity Environmental Stress of the Euryhaline Marine Fish Black Seabream (Acanthopagrus Schlegelii). Aquaculture 2022, 554, 738117. [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, Z.; Geng, L.; Teng, X. Transcriptome Analysis Revealed the Mechanism of Luciobarbus Capito (L. Capito) Adapting High Salinity: Antioxidant Capacity, Heat Shock Proteins, Immunity. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 192, 115017. [CrossRef]

- Accili, D.; Arden, K.C. FoxOs at the Crossroads of Cellular Metabolism, Differentiation, and Transformation. Cell 2004, 117, 421–426. [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.; Luo, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, K.; Wen, X.; Yin, S.; Wang, T. Interactive Effects of Temperature and Salinity on the Apoptosis, Antioxidant Enzymes, and MAPK Signaling Pathway of Juvenile Pufferfish (Takifugu Fasciatus). Aquac. Reports 2023, 29, 101483. [CrossRef]

- Birrer, S.C.; Reusch, T.B.H.; Roth, O. Salinity Change Impairs Pipefish Immune Defence. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2012, 33, 1238–1248. [CrossRef]

- Ching, B.; Chen, X.L.; Yong, J.H.A.; Wilson, J.M.; Hiong, K.C.; Sim, E.W.L.; Wong, W.P.; Lam, S.H.; Chew, S.F.; Ip, Y.K. Increases in Apoptosis, Caspase Activity and Expression of P53 and Bax, and the Transition between Two Types of Mitochondrion-Rich Cells, in the Gills of the Climbing Perch, Anabas Testudineus, during a Progressive Acclimation from Freshwater to Seawater. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 135. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Sun, L.; Zhang, L.; Hao, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Song, G.; Cui, Y.; Liu, F.; Wang, R. RNAi-Mediated Knockdown of the Aquaporin 4 Gene Impairs Salinity Tolerance and Delays the Molting Process in Pacific White Shrimp, Litopenaeus Vannamei. Aquac. Reports 2024, 35, 101974. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, R.; Sun, J.; Hao, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Cui, Y.; Liu, F.; Wang, R. Effects of High-Salinity on the Expression of Aquaporins and Ion Transport-Related Genes in Chinese Shrimp (Fenneropenaeus Chinensis). Aquac. Reports 2023, 30, 101577. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, N.; Wang, H.; Mu, C.; Wang, C. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Hepatopancreatic Genes and Pathways Associated with Metabolism Responding to Water Salinities during the Overwintering of Mud Crab Scylla Paramamosain. Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 3212–3225. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, N.; Ma, H.; Kadri, S.; Tocher, D.R. Protein and Lipid Nutrition in Crabs. Rev. Aquac. 2024,16, 1499–1519. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, A.; Roach, J.L.; Zhang, S.; Galvez, F. Salinity- and Population-Dependent Genome Regulatory Response during Osmotic Acclimation in the Killifish (Fundulus Heteroclitus) Gill. J. Exp. Biol. 2012, 215, 1293–1305. [CrossRef]

- Makvandi-Nejad, S.; Moghadam, H. Genetics and Epigenetics in Aquaculture Breeding. Epigenetics in Aquaculture 2023, 439–449.

- Guo, J.; Lv, J.; Sun, D.; Liu, P.; Gao, B. Elucidating the Role of DNA Methylation in Low-Salinity Adaptation of the Swimming Crab Portunus Trituberculatus. Aquaculture 2024, 595,741707. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Kong, L.; Yu, H. DNA Methylation Changes Detected by Methylation-Sensitive Amplified Polymorphism in the Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea Gigas) in Response to Salinity Stress. Genes and Genomics 2017, 39, 1173–1181. [CrossRef]

- Jeremias, G.; Barbosa, J.; Marques, S.M.; De Schamphelaere, K.A.C.; Van Nieuwerburgh, F.; Deforce, D.; Gonçalves, F.J.M.; Pereira, J.L.; Asselman, J. Transgenerational Inheritance of DNA Hypomethylation in Daphnia Magna in Response to Salinity Stress. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 10114–10123. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, M.; Zhou, T.; Li, Q.; Lin, Z. Genome-Wide Methylome and Transcriptome Dynamics Provide Insights into Epigenetic Regulation of Kidney Functioning of Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys Crocea) during Low-Salinity Adaption. Aquaculture 2023, 571, 739410. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, R.; Sheng, C.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, H.; Lemos, B. Microplastics Induce Intestinal Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Disorders of Metabolome and Microbiome in Zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 662, 246–253. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, F.; Chen, L.; Liu, W.T.; Du, Z.; Li, E. Response of Gut Microbiota to Salinity Change in Two Euryhaline Aquatic Animals with Reverse Salinity Preference. Aquaculture 2016, 454, 72–80. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.T.; Smith, K.F.; Melvin, D.W.; Amaral-Zettler, L.A. Community Assembly of a Euryhaline Fish Microbiome during Salinity Acclimation. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 2537–2550. [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Tan, P.; Yang, L.; Zhu, W.; Xu, D. Effects of Salinity on the Growth, Plasma Ion Concentrations, Osmoregulation, Non-Specific Immunity, and Intestinal Microbiota of the Yellow Drum (Nibea Albiflora). Aquaculture 2020, 528, 735470. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Nie, Z.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Xu, G. Integration of Metagenome and Metabolome Analysis Reveals the Correlation of Gut Microbiota, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Coilia Nasus under Air Exposure Stress and Salinity Mitigation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 2024, 49, 101175.

- Sun, S.; Gong, C.; Deng, C.; Yu, H.; Zheng, D.; Wang, L.; Sun, J.; Song, F.; Luo, J. Effects of Salinity Stress on the Growth Performance, Health Status, and Intestinal Microbiota of Juvenile Micropterus Salmoides. Aquaculture 2023, 576, 739888. [CrossRef]

- Dehler, C.E.; Secombes, C.J.; Martin, S.A.M. Seawater Transfer Alters the Intestinal Microbiota Profiles of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar L.). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13877. [CrossRef]

- Jutfelt, F.; Olsen, R.E.; Björnsson, B.T.; Sundell, K. Parr-Smolt Transformation and Dietary Vegetable Lipids Affect Intestinal Nutrient Uptake, Barrier Function and Plasma Cortisol Levels in Atlantic Salmon. Aquaculture 2007, 273, 298–311.

- Amparyup, P.; Charoensapsri, W.; Tassanakajon, A. Prophenoloxidase System and Its Role in Shrimp Immune Responses against Major Pathogens. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 34, 990–1001. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.E. V; Hansson, G.C. Immunological Aspects of Intestinal Mucus and Mucins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 639–649. [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Zheng, M.; Li, S.; Xie, J.; Fang, W.; Gao, D.; Huang, J.; Lu, J. Response of Gut Microbiota and Immune Function to Hypoosmotic Stress in the Yellowfin Seabream (Acanthopagrus Latus). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 140976. [CrossRef]

- Champion, C.; Broadhurst, M.K.; Ewere, E.E.; Benkendorff, K.; Butcherine, P.; Wolfe, K.; Coleman, M.A. Resilience to the Interactive Effects of Climate Change and Discard Stress in the Commercially Important Blue Swimmer Crab (Portunus Armatus). Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 159, 105009. [CrossRef]

- Asem, A.; Eimanifar, A.; Van Stappen, G.; Sun, S.C. The Impact of One-Decade Ecological Disturbance on Genetic Changes: A Study on the Brine Shrimp Artemia Urmiana from Urmia Lake, Iran. PeerJ 2019, 2019, 7190. [CrossRef]

- Pauls, S.U.; Nowak, C.; Bálint, M.; Pfenninger, M. The Impact of Global Climate Change on Genetic Diversity within Populations and Species. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 925–946. [CrossRef]

- Laurenzano, C.; Costa, T.M.; Schubart, C.D. Contrasting Patterns of Clinal Genetic Diversity and Potential Colonization Pathways in Two Species of Western Atlantic Fiddler Crabs. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0166518. [CrossRef]

- Peres, P.A.; Mantelatto, F.L. Salinity Tolerance Explains the Contrasting Phylogeographic Patterns of Two Swimming Crabs Species along the Tropical Western Atlantic. Evol. Ecol. 2020, 34, 589–609. [CrossRef]