Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

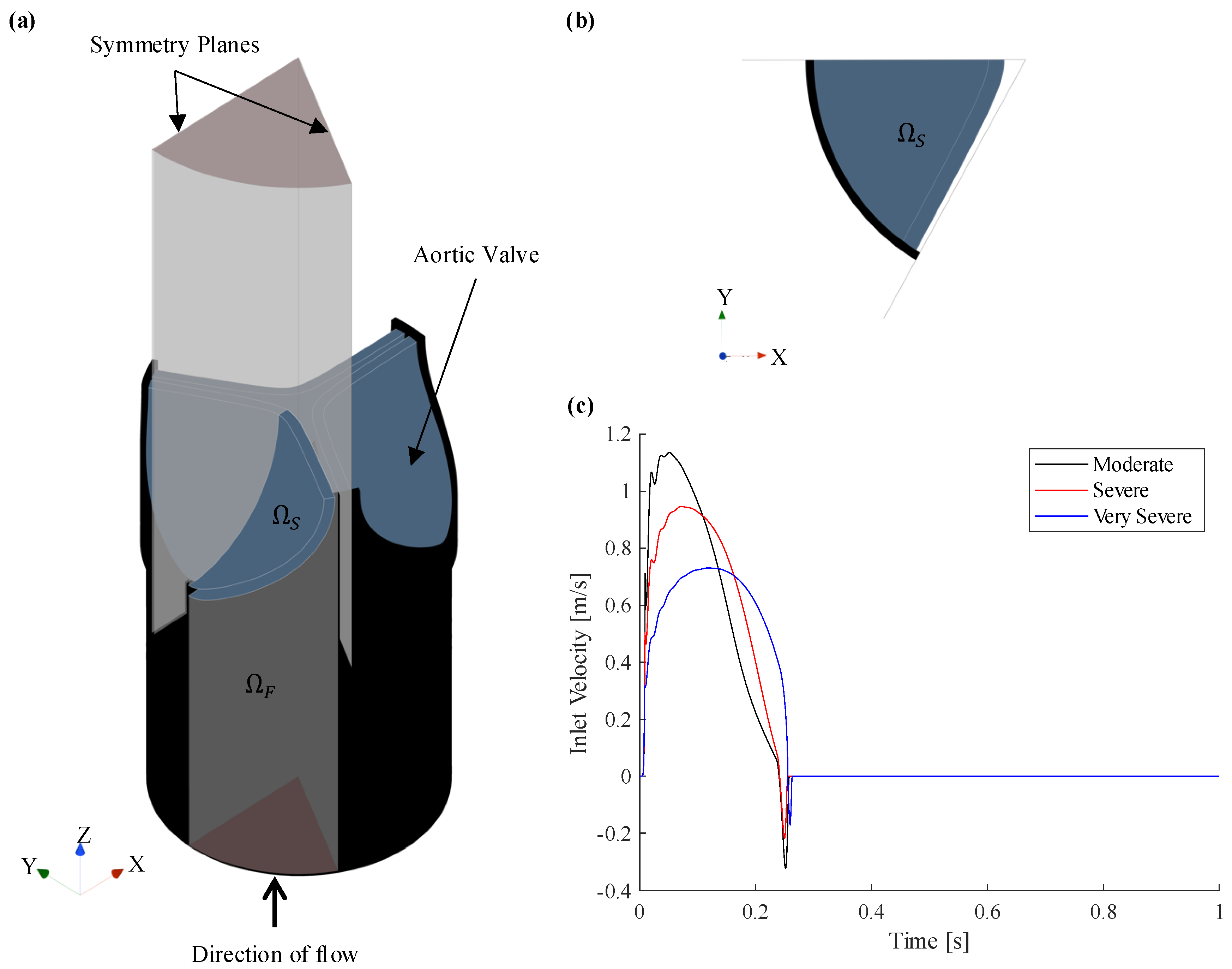

2.1. Description of Computational Domain

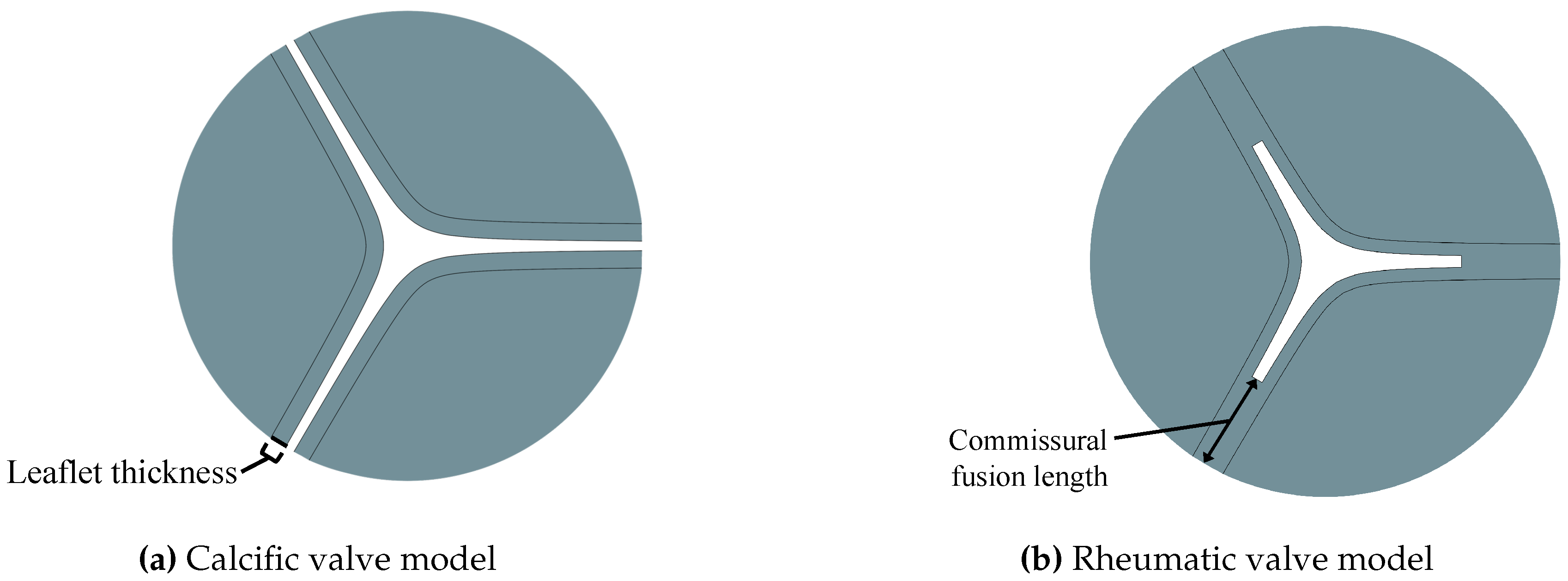

2.2. Case Studies

2.3. Modelling Theory

2.3.1. Fluid Flow Conservation Equations

2.3.2. Structure Mechanics Conservation Equations

2.4. Model Development

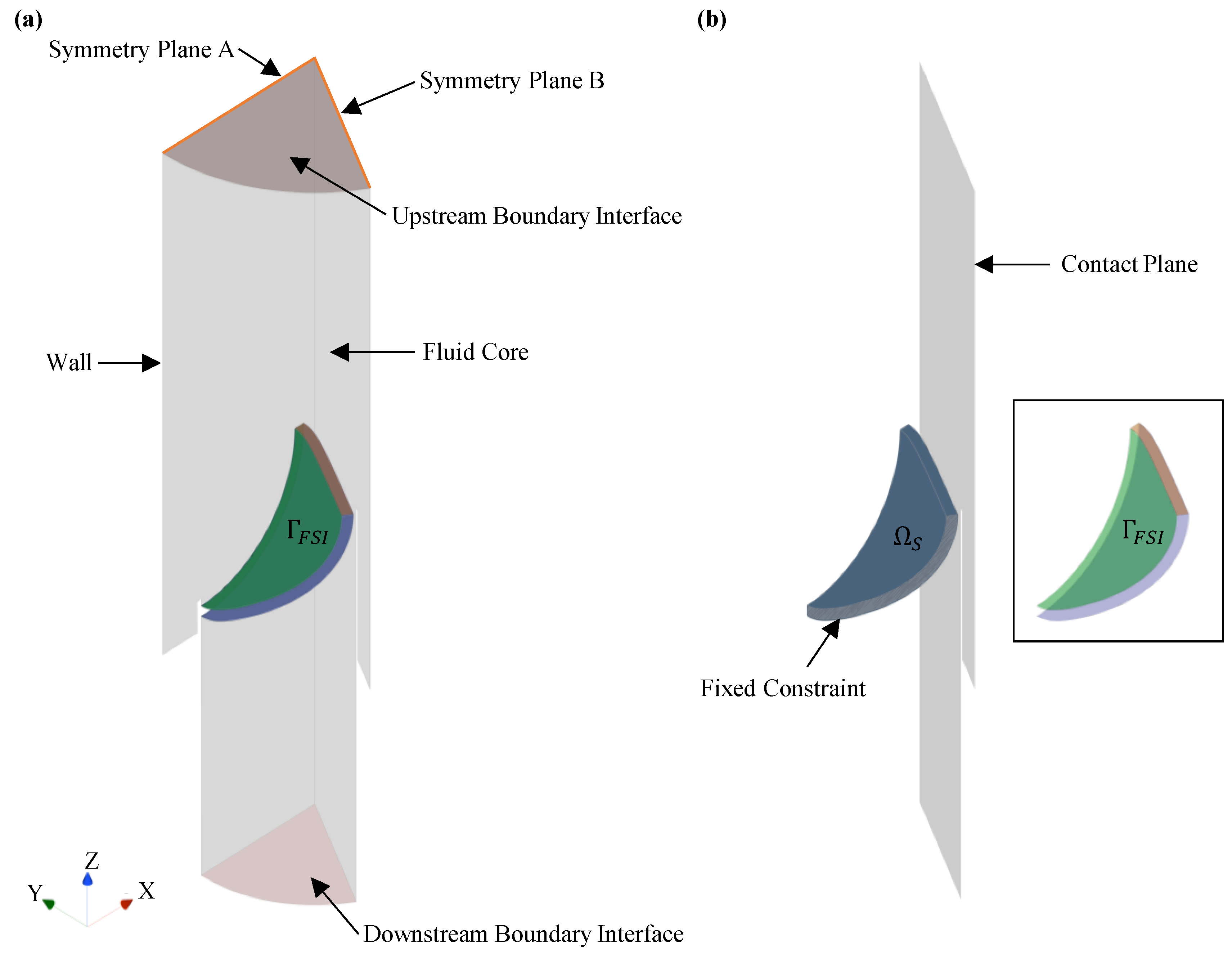

2.4.1. Fluid Domain

2.4.2. Solid Domain

2.4.3. Post Processing of Simulation Results

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mesh Convergence

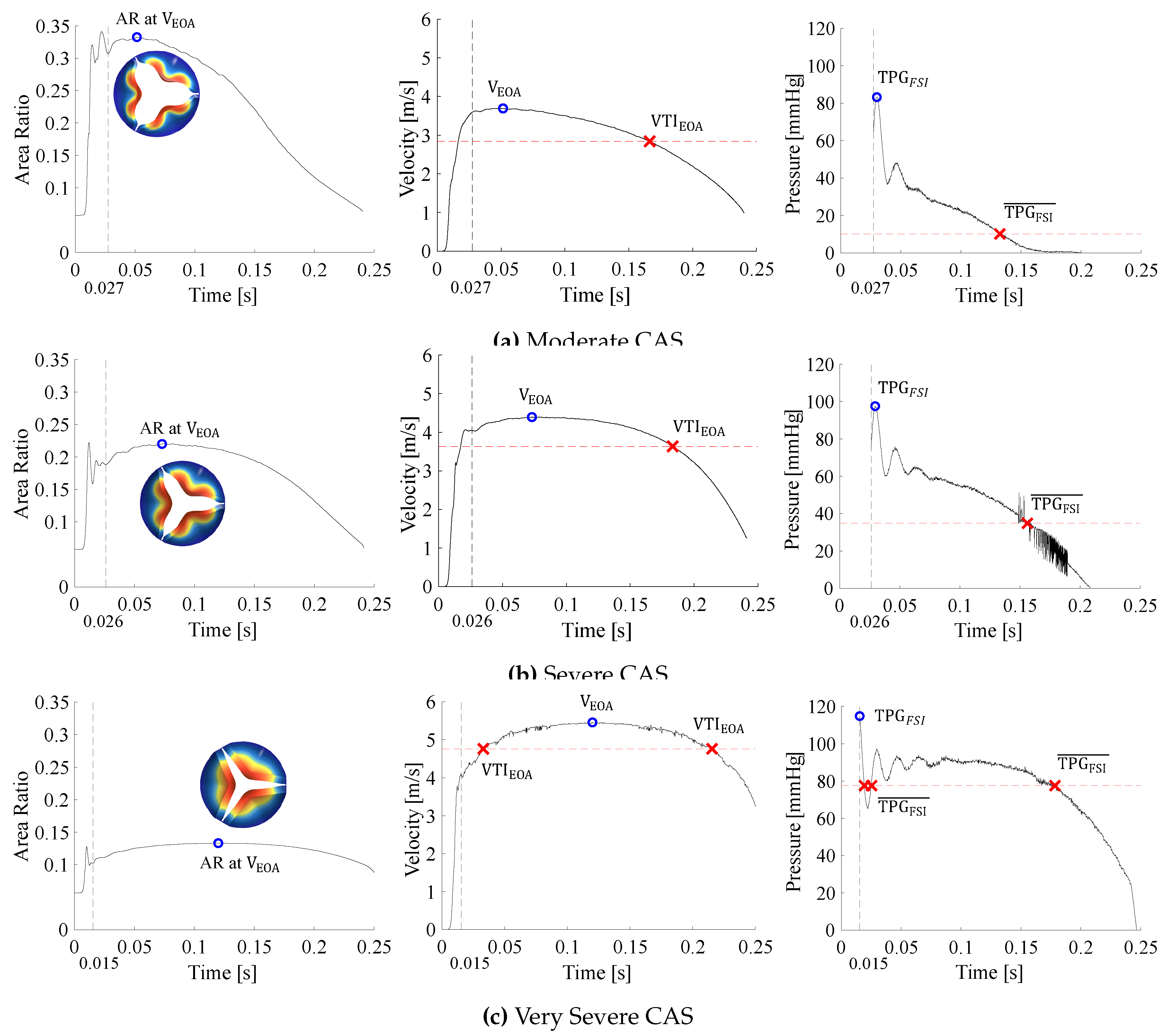

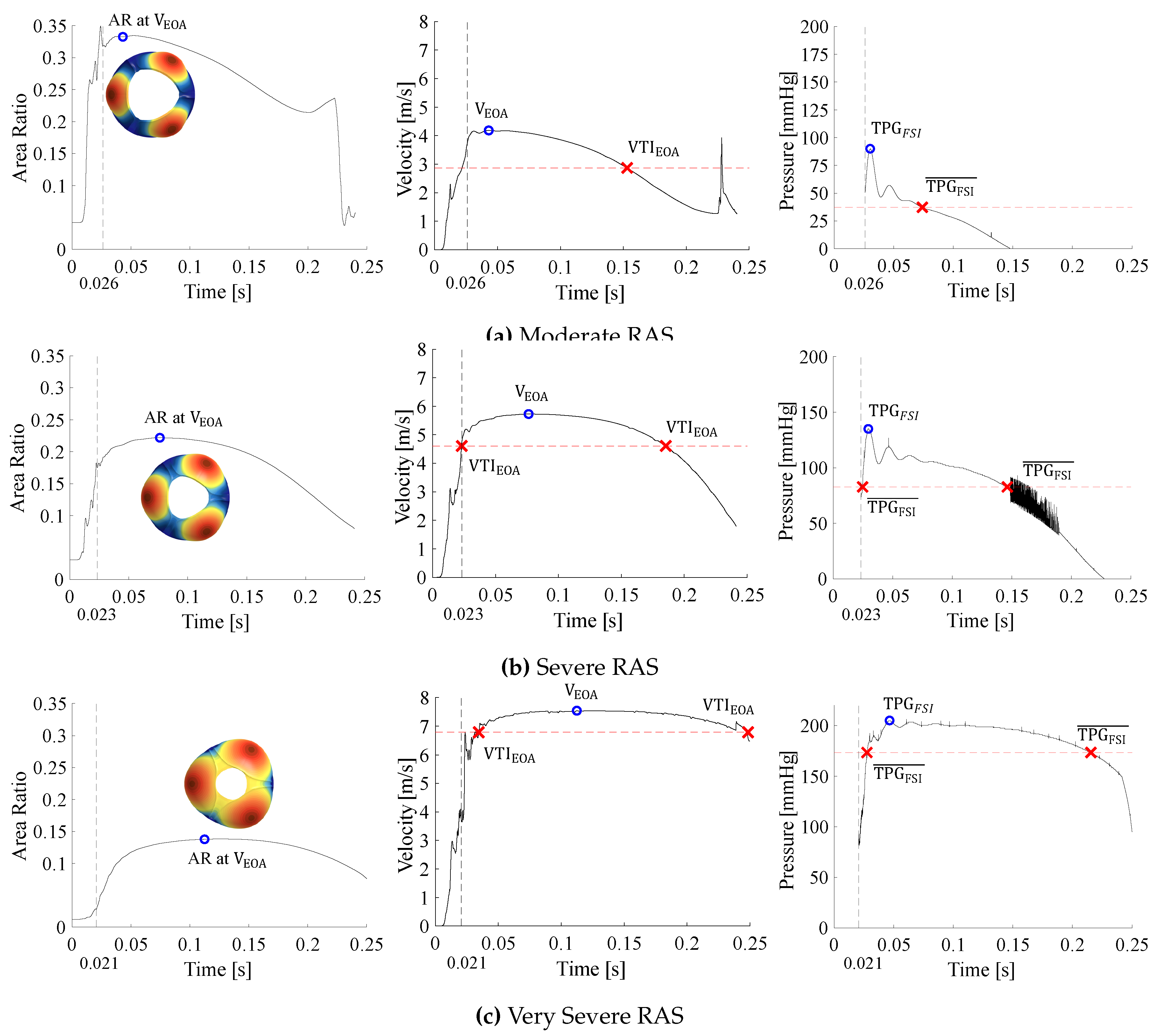

3.2. Data Interpretation

- The systolic period () is calculated from the inlet velocity BC as the time when the velocity profile is positive. For the moderate, severe, and very severe CAS and RAS cases, the systolic periods are 0.2403, 0.2413 and 0.2554, respectively.

- With the exception of SV, all other data only pertains to the systolic period of the cardiac cycle. For the moderate, severe, and very severe CAS and RAS cases, the SV is 71.1/, 72.3/ and 68.1/, respectively.

- As the valve opens, the AR rapidly increases and fluctuates before it settles, whereafter it increases and decreases proportionally to the BC velocity profile. The valve is considered open after the AR has settled.

- Peak haemodynamic conditions are determined after the valve is considered open.

- The EOA velocity in the domain increases as the valve opens and reaches a maximum (). The time of peak EOA velocity () describes the phrase peak systole.

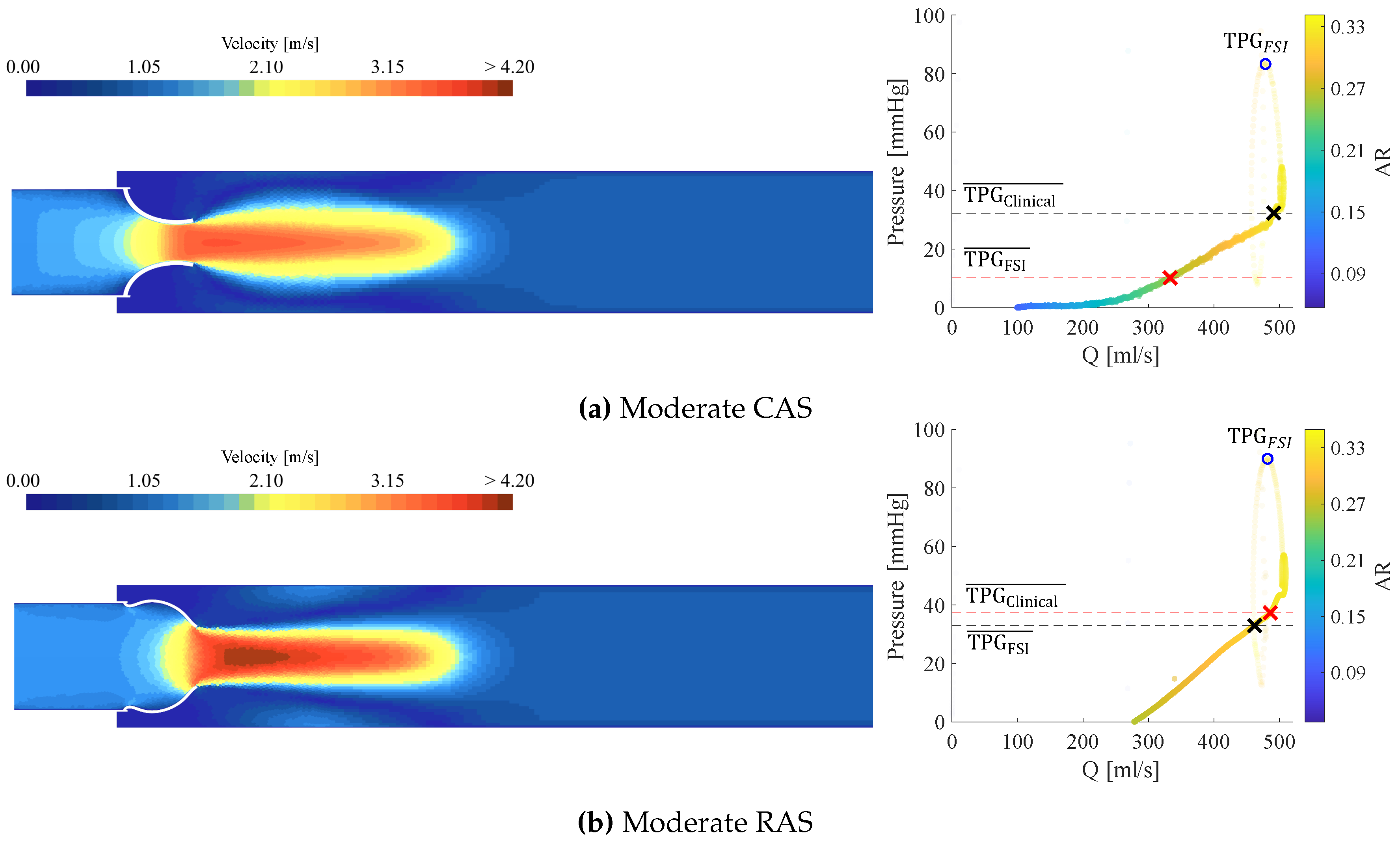

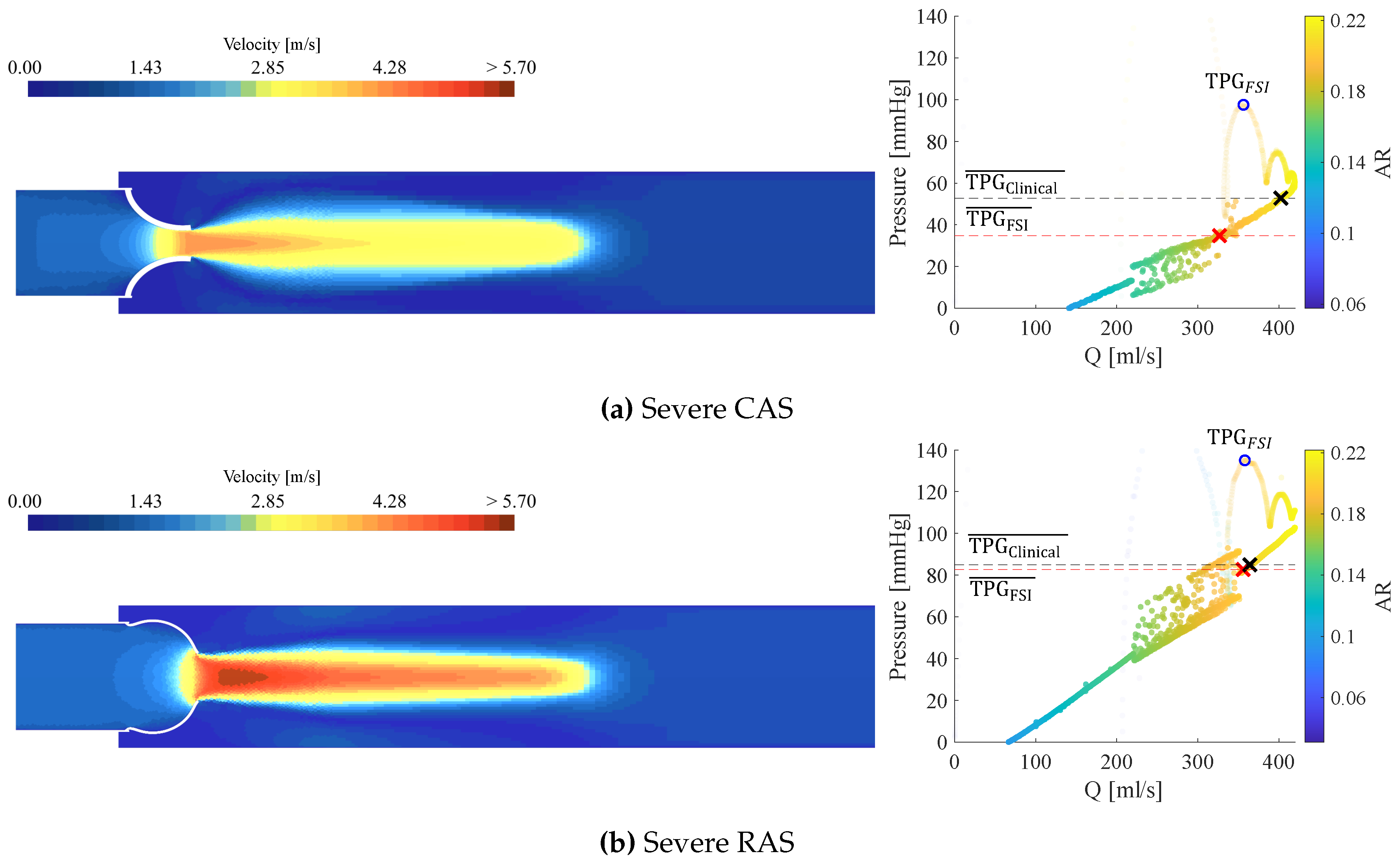

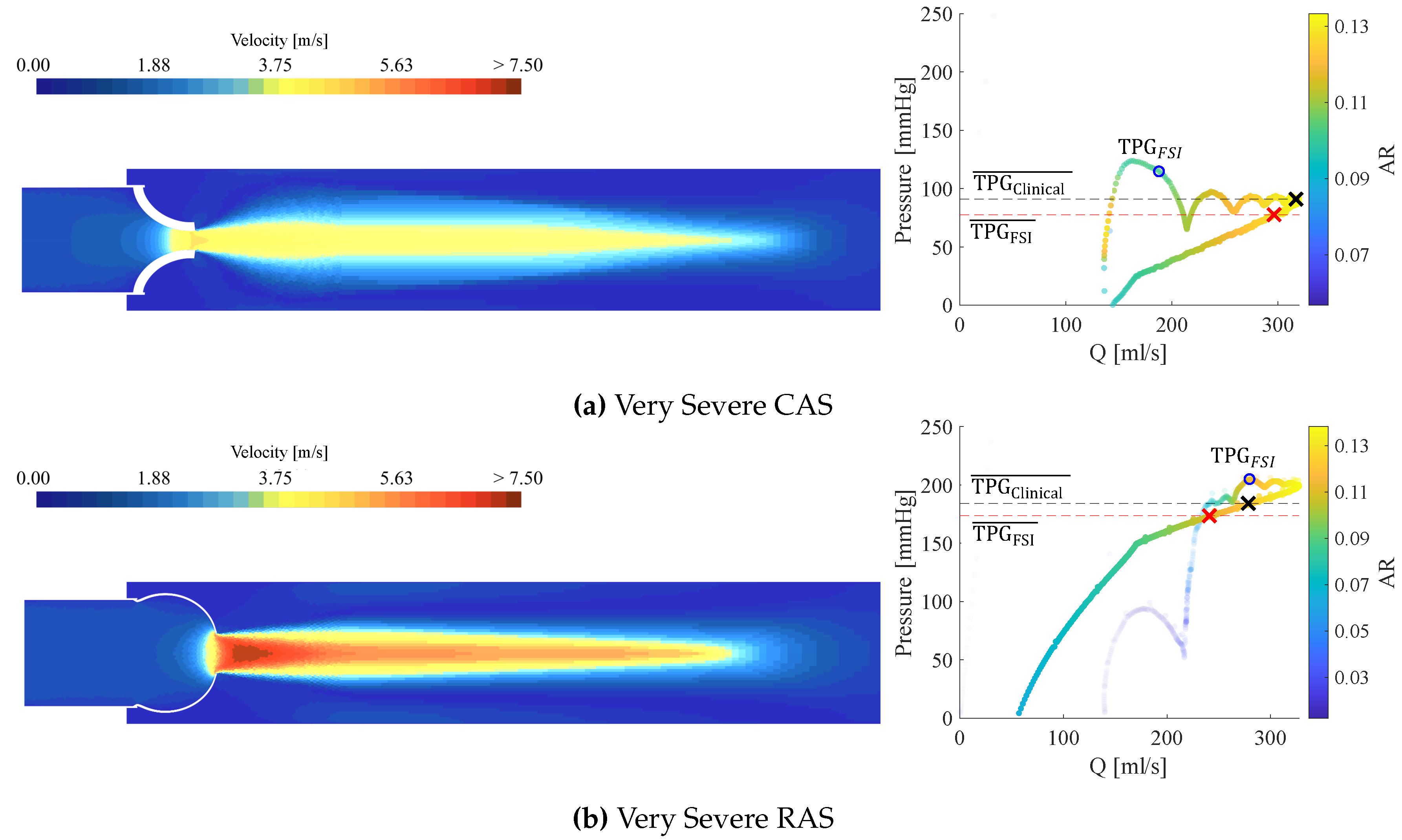

3.3. Calcific Aortic Stenosis

3.4. Rheumatic Aortic Stenosis

3.5. General Comparison Between CAS and RAS

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Otto, C.M.; Nishimura, R.A.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P.; Gentile, F.; Jneid, H.; Krieger, E.V.; Mack, M.; McLeod, C.; et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2021, 77, e25–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahanian, A.; Beyersdorf, F.; Praz, F.; Milojevic, M.; Baldus, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Capodanno, D.; Conradi, L.; Bonis, M.D.; Paulis, R.D.; et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). European Heart Journal 2022, 43, 561–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmis, A.; Aboyans, V.; Vardas, P.; Townsend, N.; Torbica, A.; Kavousi, M.; Boriani, G.; Huculeci, R.; Kazakiewicz, D.; Scherr, D.; et al. European Society of Cardiology: the 2023 Atlas of Cardiovascular Disease Statistics. European Heart Journal 2024, 45, 4019–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, S.; Roberts-Thomson, R.; Brown, A.; Carapetis, J.; Chen, M.; Enriquez-Sarano, M.; Zühlke, L.; Prendergast, B.D. Global epidemiology of valvular heart disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2021, 18, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.T.; Ye, Z.; Ullah, M.W.; Maleszewski, J.J.; Scott, C.G.; Padang, R.; Pislaru, S.V.; Nkomo, V.T.; Mankad, S.V.; Pellikka, P.A.; et al. Bicuspid aortic valve: long-term morbidity and mortality. European Heart Journal 2023, 44, 4549–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, L.; Peters, F.; Vainrib, A.F.; Freedberg, R.S.; Saric, M. Rheumatic Heart Disease: A Rare Cause of Very Severe Valvular Aortic Stenosis. CASE 2024, 8, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, A.; Hosny, H.; Yacoub, M. Rheumatic aortic valve disease-when and who to repair? Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery 2019, 8, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grobler, L.; Laubscher, R.; van der Merwe, J.; Herbst, P.G. Evaluation of Aortic Valve Pressure Gradients for Increasing Severities of Rheumatic and Calcific Stenosis Using Empirical and Numerical Approaches. Mathematical and Computational Applications 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, B.; Weese, J.; Waechter-Stehle, I.; Brüning, J.; Kuehne, T.; Goubergrits, L. Towards improving the accuracy of aortic transvalvular pressure gradients: rethinking Bernoulli. Medical & and Biological Engineering & Computing 2020, 58, 1667–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatle, L.; Brubakk, A.; Tromsdal, A.; Angelsen, B. Noninvasive assessment of pressure drop in mitral stenosis by Doppler ultrasound. British Heart Journal 1978, 40, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pase, G.; Brinkhuis, E.; Vries, T.D.; Kosinka, J.; Willems, T.; Bertoglio, C. A parametric geometry model of the aortic valve for subject-specific blood flow simulations using a resistive approach. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology 2023, 22, 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmeier, F.; Brüning, J.; Sündermann, S.; Jarmatz, L.; Schafstedde, M.; Goubergrits, L.; Kühne, T.; Nordmeyer, S. Hemodynamic Modeling of Biological Aortic Valve Replacement Using Preoperative Data Only. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2021, 7, 593709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeijmakers, M.J.; Waechter-Stehle, I.; Weese, J.; de Vosse, F.N.V. Combining statistical shape modeling, CFD, and meta-modeling to approximate the patient-specific pressure-drop across the aortic valve in real-time. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Biomedical Engineering 2020, 36, e3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.; Kuppurao, L. Quantitative Doppler echocardiography. BJA Education 2016, 16, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; Lantz, J.; Ziegler, M.; Casas, B.; Karlsson, M.; Dyverfeldt, P.; Ebbers, T. Estimating the irreversible pressure drop across a stenosis by quantifying turbulence production using 4D Flow MRI. Scientific Reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Padgett, D.A.; Callahan, S.; Stoddard, M.; Amini, A.A. Relative pressure estimation from 4D flow MRI using generalized Bernoulli equation in a phantom model of arterial stenosis. Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 2022, 35, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Guo, G.; Wang, A.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhao, P.; Yin, Z.; Liu, S.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Quantification of functional hemodynamics in aortic valve disease using cardiac computed tomography angiography. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 177, 108608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, B.; Brüning, J.; Yevtushenko, P.; Dreger, H.; Brand, A.; Juri, B.; Unbehaun, A.; Kempfert, J.; Sündermann, S.; Lembcke, A.; et al. Computed Tomography-Based Assessment of Transvalvular Pressure Gradient in Aortic Stenosis. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2021, 8, 706628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchumov, A.G.; Makashova, A.; Vladimirov, S.; Borodin, V.; Dokuchaeva, A. Fluid–Structure Interaction Aortic Valve Surgery Simulation: A Review. Fluids 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hart, J.; Peters, G.W.M.; Schreurs, P.J.G.; Baaijens, F.P.T. A three-dimensional computational analysis of fluid-structure interaction in the aortic valve. Journal of Biomechanics 2003, 36, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Hao, Y.; Ma, P.; Guangyu, Z.; Luo, X.; Gao, H. Fluid-structure interaction simulation of calcified aortic valve stenosis. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 2022, 19, 13172–13192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Martin, C.; Pham, T. Computational modeling of cardiac valve function and intervention. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 2014, 16, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luraghi, G.; Wu, W.; Gaetano, F.D.; Matas, J.F.R.; Moggridge, G.D.; Serrani, M.; Stasiak, J.; Costantino, M.L.; Migliavacca, F. Evaluation of an aortic valve prosthesis: Fluid-structure interaction or structural simulation? Journal of Biomechanics 2017, 58, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luraghi, G.; Migliavacca, F.; García-González, A.; Chiastra, C.; Rossi, A.; Cao, D.; Stefanini, G.; Matas, J.F.R. On the Modeling of Patient-Specific Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Fluid–Structure Interaction Approach. Cardiovascular Engineering and Technology 2019, 10, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakerzadeh, R.; Hsu, M.C.; Sacks, M.S. Computational methods for the aortic heart valve and its replacements. Expert Review of Medical Devices 2017, 14, 849–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spühler, J.H.; Jansson, J.; Jansson, N.; Hoffman, J. 3D fluid-structure interaction simulation of aortic valves using a unified continuum ALE FEM model. Frontiers in Physiology 2018, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi Pour, M.J.; Hassani, K.; Khayat, M.; Haghighi, S.E. Modeling of aortic valve stenosis using fluid-structure interaction method. Perfusion 2021, 37, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, S.; Henstock, A.; Sadeghi, R.; Sellers, S.; Blanke, P.; Leipsic, J.; Emadi, A.; Keshavarz-Motamed, Z. Personalized intervention cardiology with transcatheter aortic valve replacement made possible with a non-invasive monitoring and diagnostic framework. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 10888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, A.D.; Shad, R.; Hiesinger, W.; Marsden, A.L. A design-based model of the aortic valve for fluid-structure interaction. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology 2021, 20, 2413–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dake, P.G.; Mukherjee, J.; Sahu, K.C.; Pandit, A.B. Computational Fluid Dynamics in Cardiovascular Engineering: A Comprehensive Review. Transactions of the Indian National Academy of Engineering 2024, 9, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubscher, R.; van der Merwe, J.; Liebenberg, J.; Herbst, P. Dynamic simulation of aortic valve stenosis using a lumped parameter cardiovascular system model with flow regime dependent valve pressure loss characteristics. Medical Engineering and Physics 2022, 106, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouhi, E.; Morsi, Y.S. A parametric study on mathematical formulation and geometrical construction of a stentless aortic heart valve. Journal of Artificial Organs 2013, 16, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gaetano, F.; Serrani, M.; Bagnoli, P.; Brubert, J.; Stasiak, J.; Moggridge, G.D.; Costantino, M.L. Fluid dynamic characterization of a polymeric heart valve prototype (Poli-Valve) tested under continuous and pulsatile flow conditions. International Journal of Artificial Organs 2015, 38, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamannan, N.M.; Evans, F.J.; Aikawa, E.; Grande-Allen, K.J.; Demer, L.L.; Heistad, D.D.; Simmons, C.A.; Masters, K.S.; Mathieu, P.; O’Brien, K.D.; et al. Calcific aortic valve disease: Not simply a degenerative process: A review and agenda for research from the national heart and lung and blood institute aortic stenosis working group. Executive summary: Calcific aortic valve disease - 2011 update. Circulation 2011, 124, 1783–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens Digital Industries Software. Simcenter STAR-CCM+ User Guide, version 2024.1. In Theory; Siemens, 2024; pp. 8474–9869.

- Le, T.B.; Usta, M.; Aidun, C.; Yoganathan, A.; Sotiropoulos, F. Computational Methods for Fluid-Structure Interaction Simulation of Heart Valves in Patient-Specific Left Heart Anatomies. Fluids 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteeg, H.K.; Malalasekera, W. An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics The Finite Volume Method, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education Limited, 2007.

- Reddy, J.N. Introduction to Nonlinear Finite Element Analysis: With Applications to Heat Transfer, Fluid Mechanics, and Solid Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Vitello, D.J.; Ripper, R.M.; Fettiplace, M.R.; Weinberg, G.L.; Vitello, J.M. Blood Density Is Nearly Equal to Water Density: A Validation Study of the Gravimetric Method of Measuring Intraoperative Blood Loss. Journal of Veterinary Medicine 2015, 2015, 152730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Wei, L.; Wang, S. A Fluid–Structure Interaction Study of Different Bicuspid Aortic Valve Phenotypes Throughout the Cardiac Cycle. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12, 716015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The MathWorks Inc.. MATLAB, 2024. Version R2024a.

- Reynolds, H.R.; Spevack, D.M.; Shah, A.; Applebaum, R.M.; Kanchuger, M.; Tunick, P.A.; Kronzon, I. Comparison of image quality between a narrow caliber transesophageal echocardiographic probe and the standard size probe during intraoperative evaluation. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography 2004, 17, 1050–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, I.B.; Ghia, U.; Roache, P.J.; Freitas, Christopher J.and Coleman, H.; Raad, P.E. Procedure for Estimation and Reporting of Uncertainty Due to Discretization in CFD Applications. Journal of Fluids Engineering 2008, 130, 078001. [CrossRef]

| Type | Severity | Leaflet thickness [mm] | Commissural fusion length [mm] | AVA [cm2] | AR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | 0.896 | - | 1.494 | 0.330 | |

| CAS | Severe | 1.180 | - | 0.992 | 0.219 |

| Very Severe | 1.950 | - | 0.604 | 0.134 | |

| Moderate | 5.05 | 1.516 | 0.335 | ||

| RAS | Severe | 0.650 | 7.75 | 1.004 | 0.222 |

| Very Severe | 10.65 | 0.626 | 0.138 |

| Total Cell Count | Peak Velocity GCI | Mean TPG GCI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC | 219,715 | 1.85 | 1.18 | |||

| SC | 161,259 | 0.74 | 0.02 | |||

| VSC | 135,160 | 0.01 | 0.29 | |||

| MR | 189,563 | 0.82 | 0.18 | |||

| SR | 199,343 | 0.28 | 0.15 | |||

| VSR | 196,378 | 1.17 | 0.31 | |||

| Flow Parameters | Peak | Mean | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ | [ | [ | [ | [ | [ | [ | [ | [ | |

| MC | 298 | 1.41 | 3.69 | 40.5 | 83.3 | 54.5 | 2.84 | 10.2 | 32.3 |

| SC | 297 | 2.10 | 4.39 | 60.2 | 97.5 | 77.2 | 3.63 | 34.9 | 52.8 |

| VSC | 260 | 2.74 | 5.46 | 90.0 | 114.8 | 119.1 | 4.77 | 77.6 | 90.9 |

| MR | 300 | 1.51 | 4.18 | 53.0 | 90.0 | 70.0 | 2.87 | 37.3 | 33.0 |

| SR | 301 | 3.65 | 5.73 | 105.0 | 135.0 | 131.2 | 4.61 | 82.8 | 85.0 |

| VSR | 266 | 6.57 | 7.54 | 200.3 | 207.0 | 227.3 | 6.79 | 173.6 | 184.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).