Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Empirical Materials

2.2. Hypotheses and Relationships

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Jupiter and Heliophysics

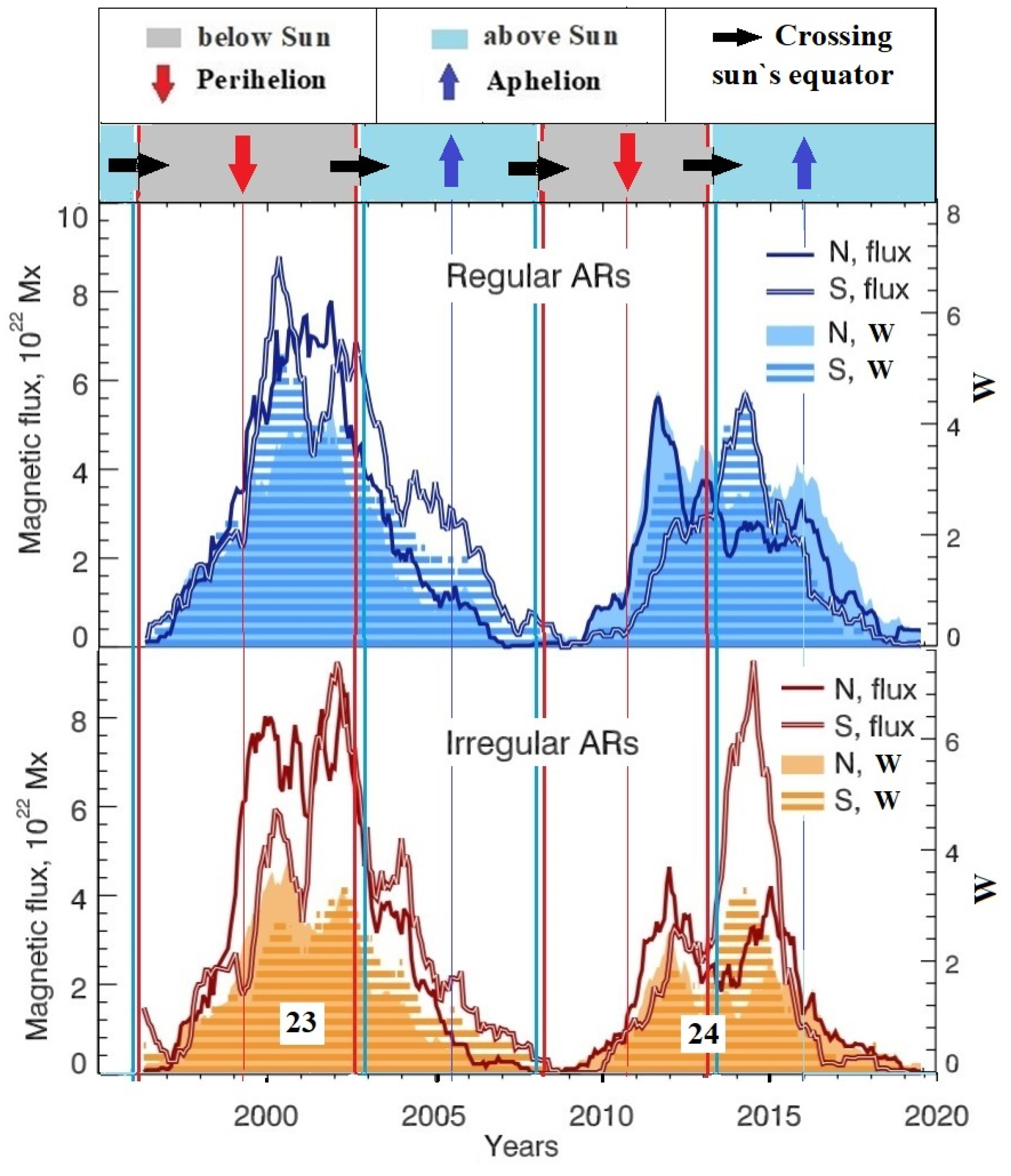

3.2. Magnetism of Sun and Jupiter

- a)

- at beginning: mN sinθn—mS sinθs ~ 0 и mS = mN cosθn—mS cosθs > 0;

- b)

- isthmus: mN cosθn—mS cos φs ~ 0 и QS = mN sinθn—mS sinθs > 0;

- c)

- at end: mN sinθn—mS sinθs ~ 0 и mS = mN cosθn—mS cos θs ~ 0.

3.3. Comet Shoemaker-Levy Fall on Jupiter

3.4. Earth Echo of Fall of Comet SL9

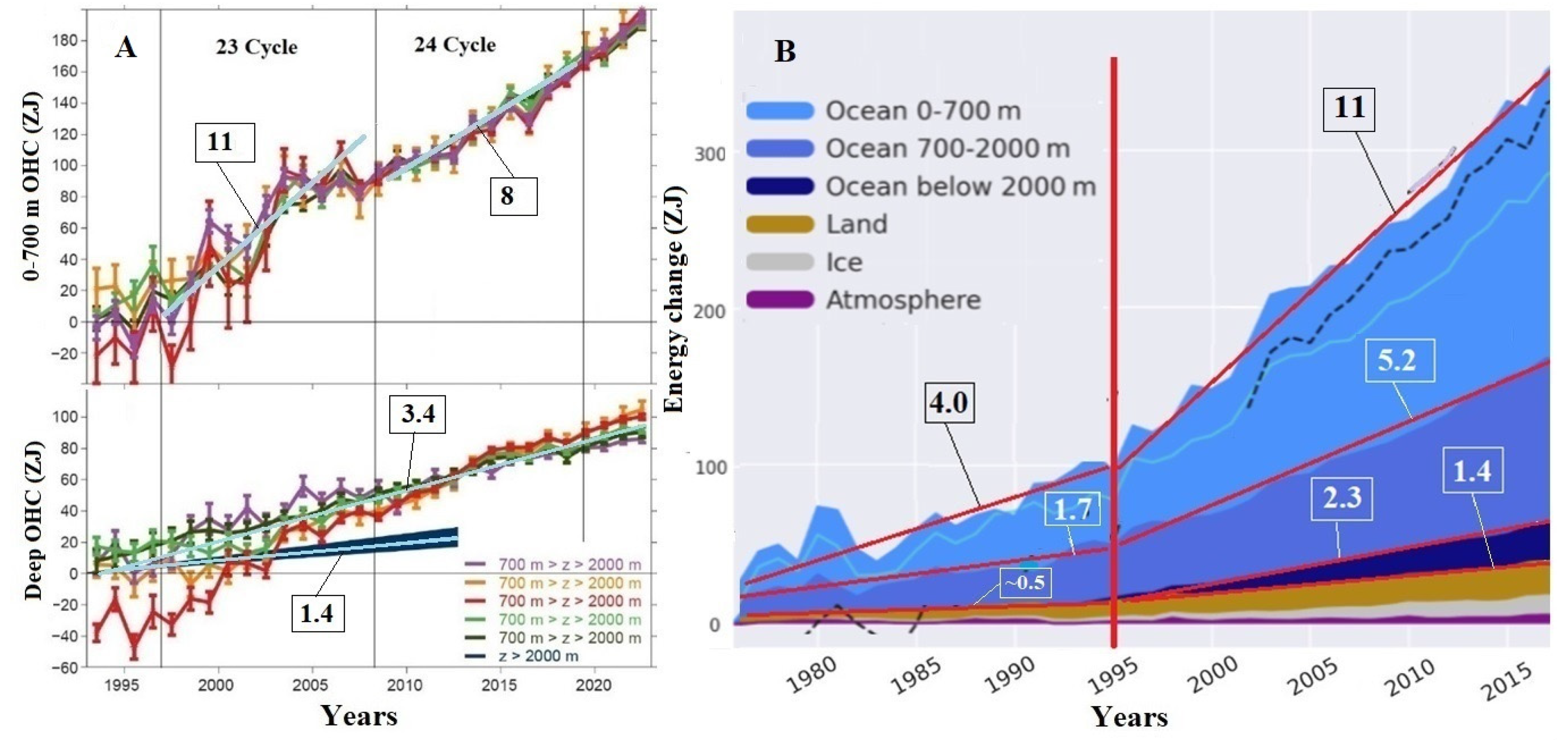

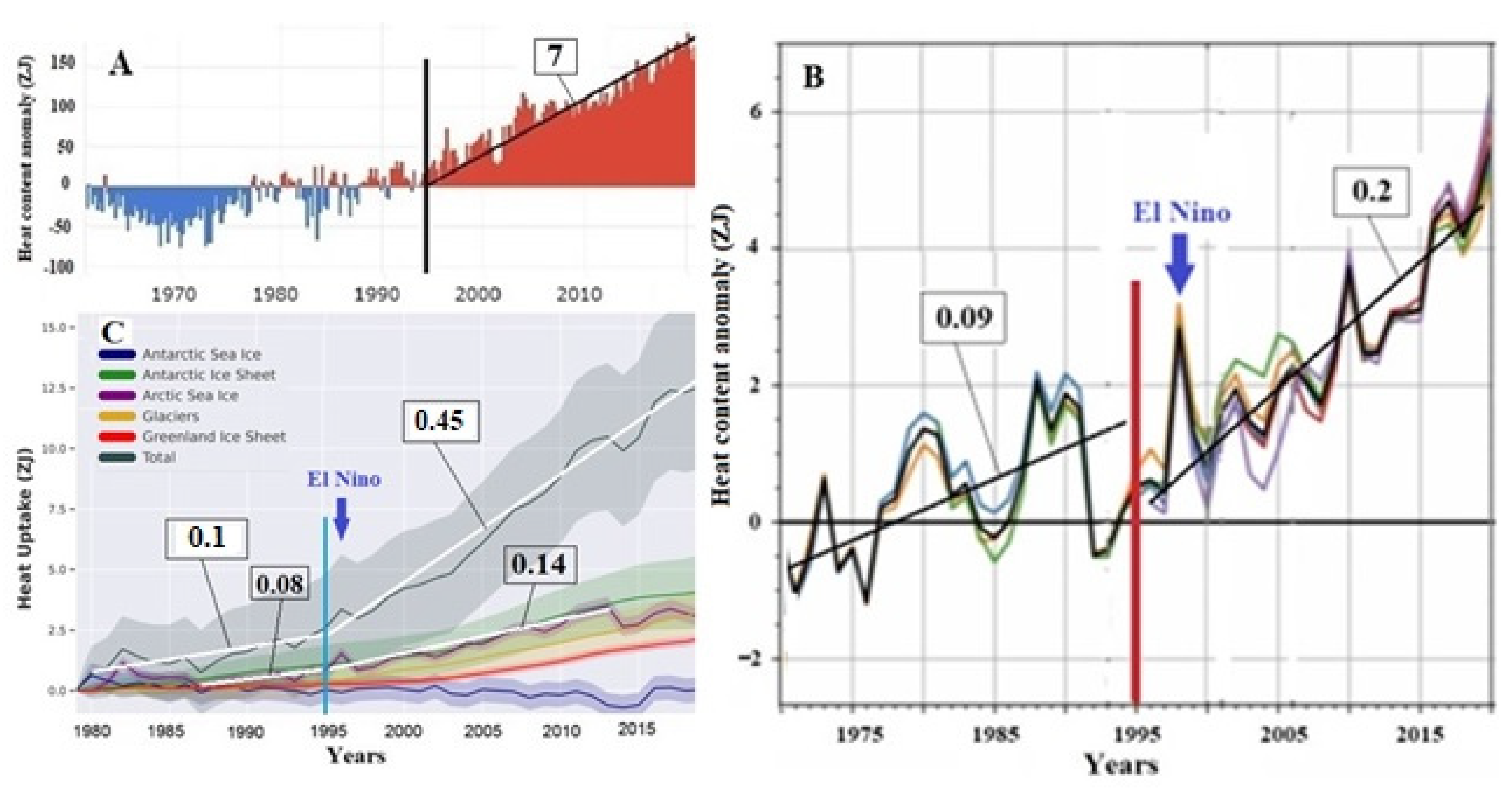

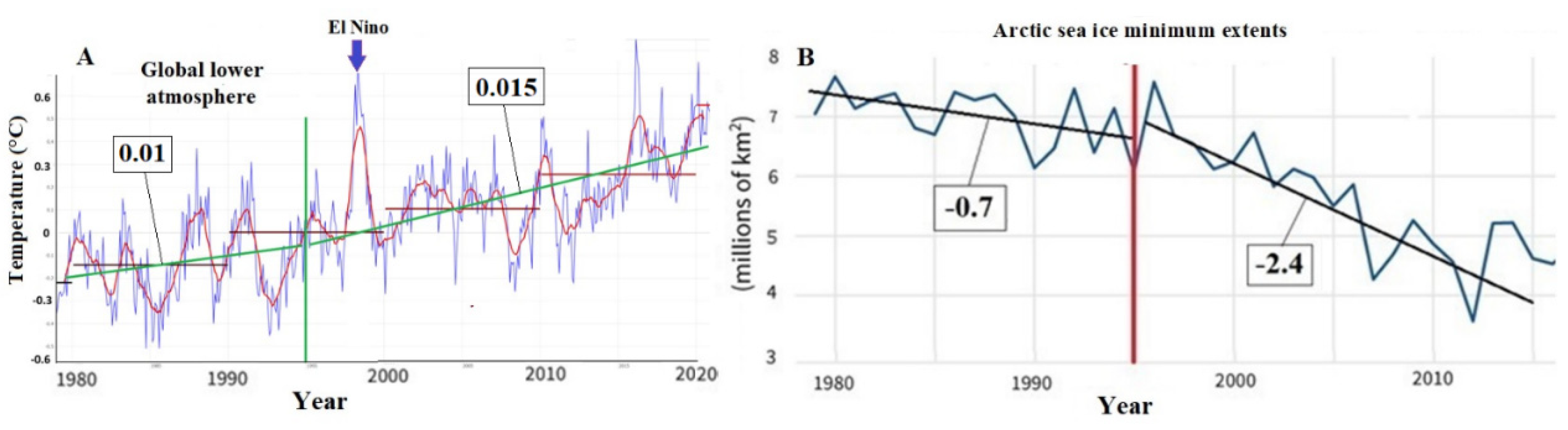

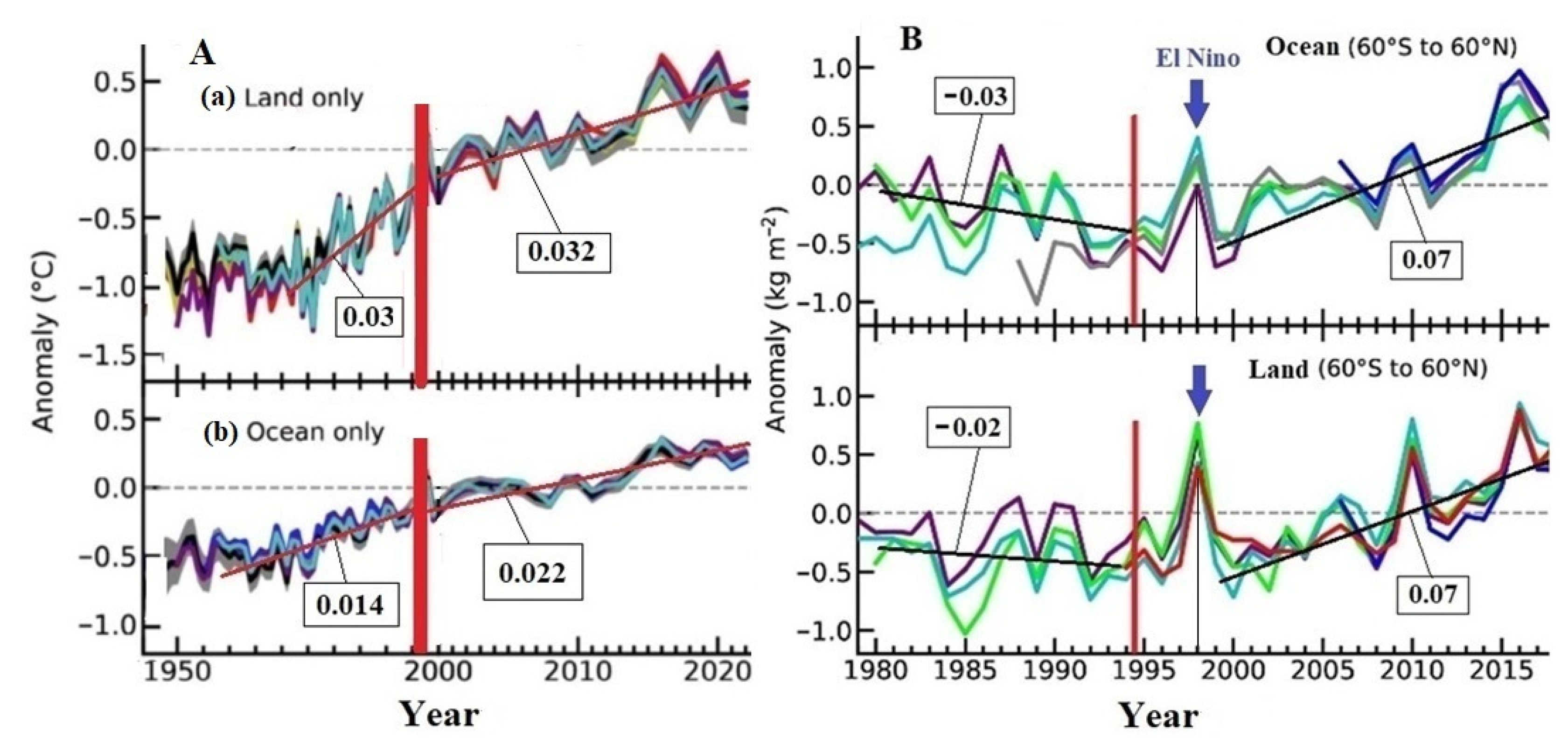

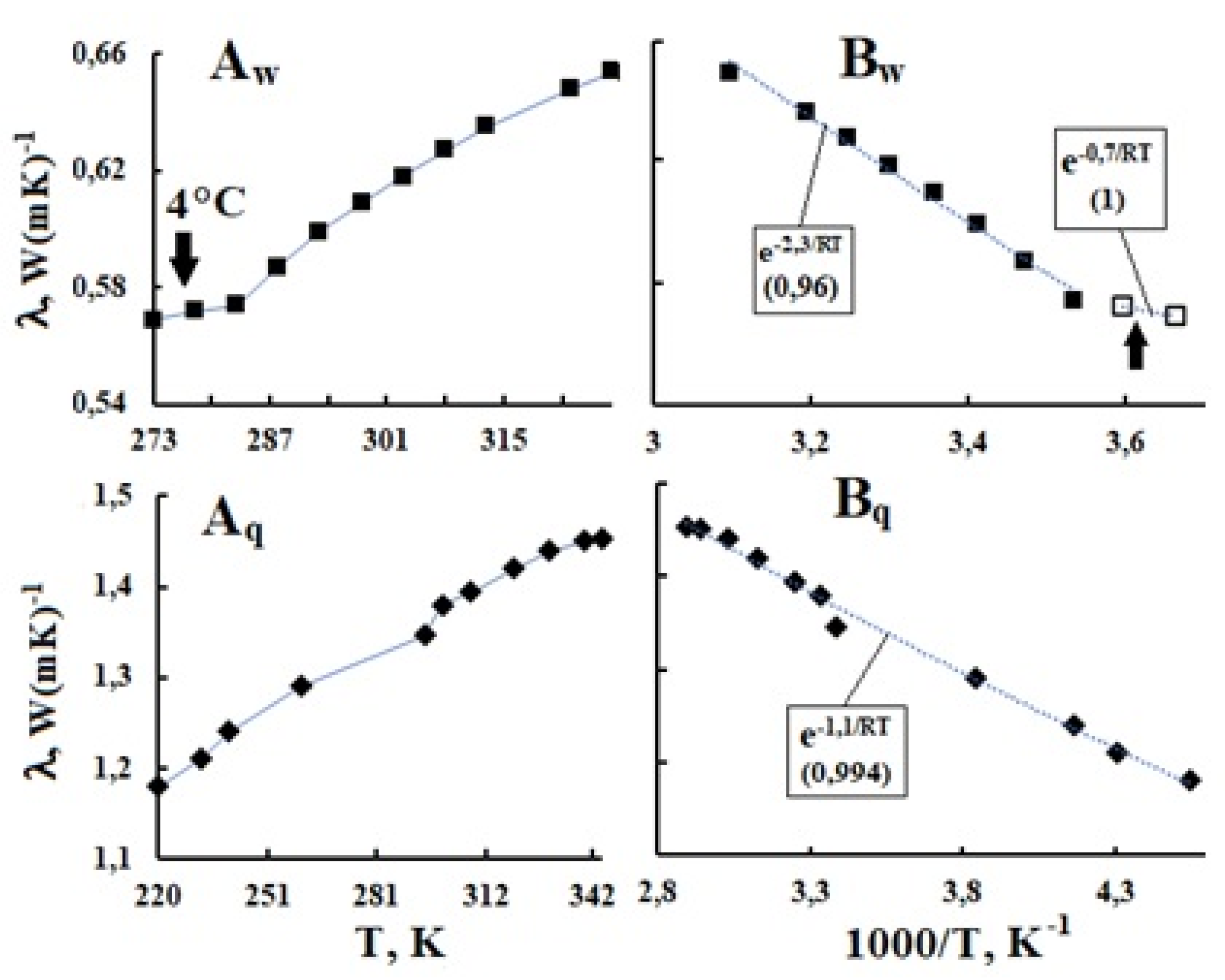

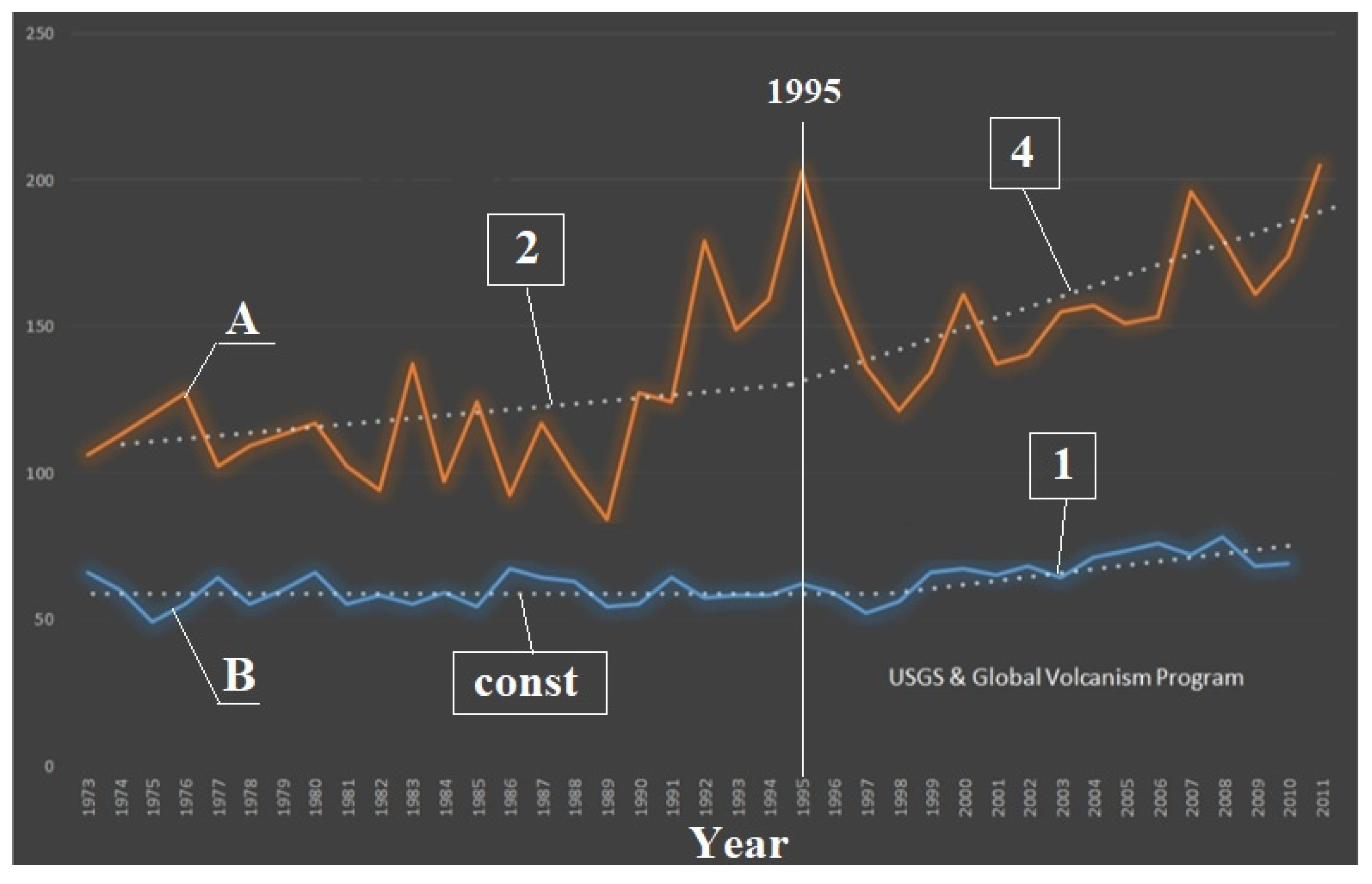

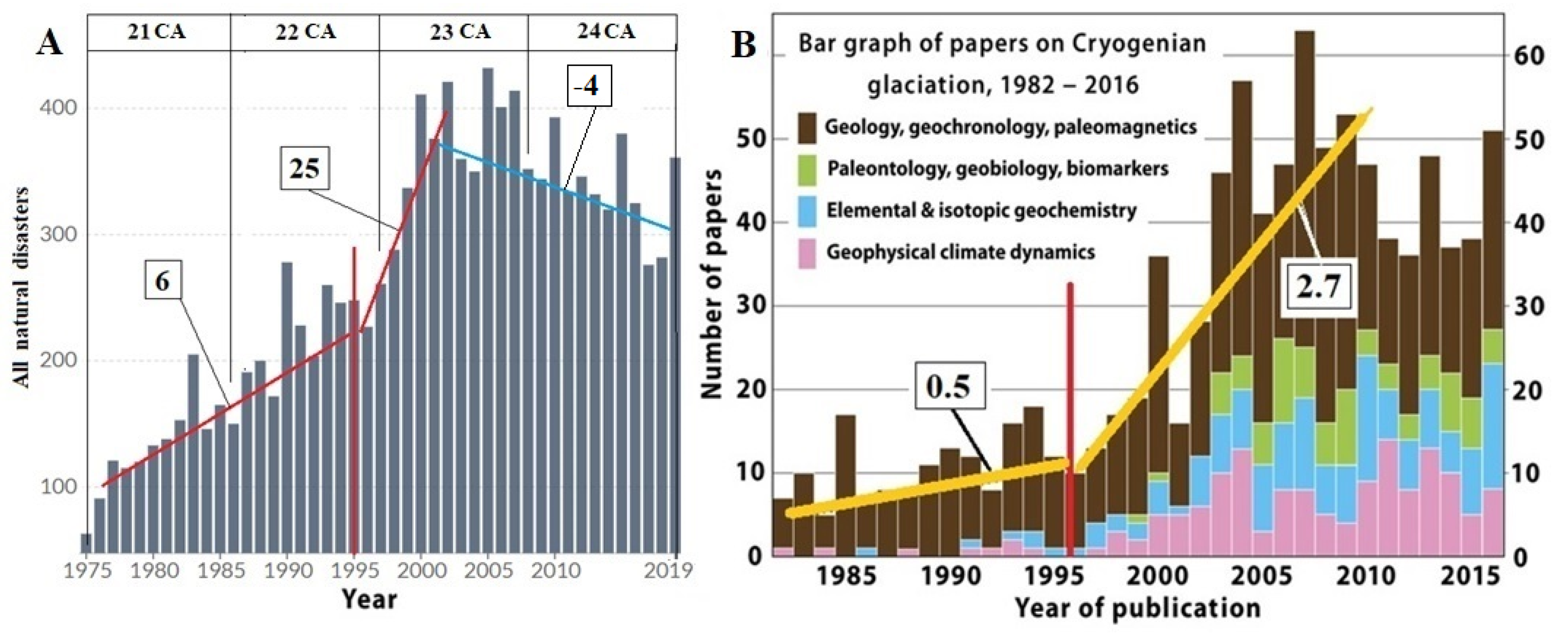

3.4.1. Hydrosphere and Atmosphere

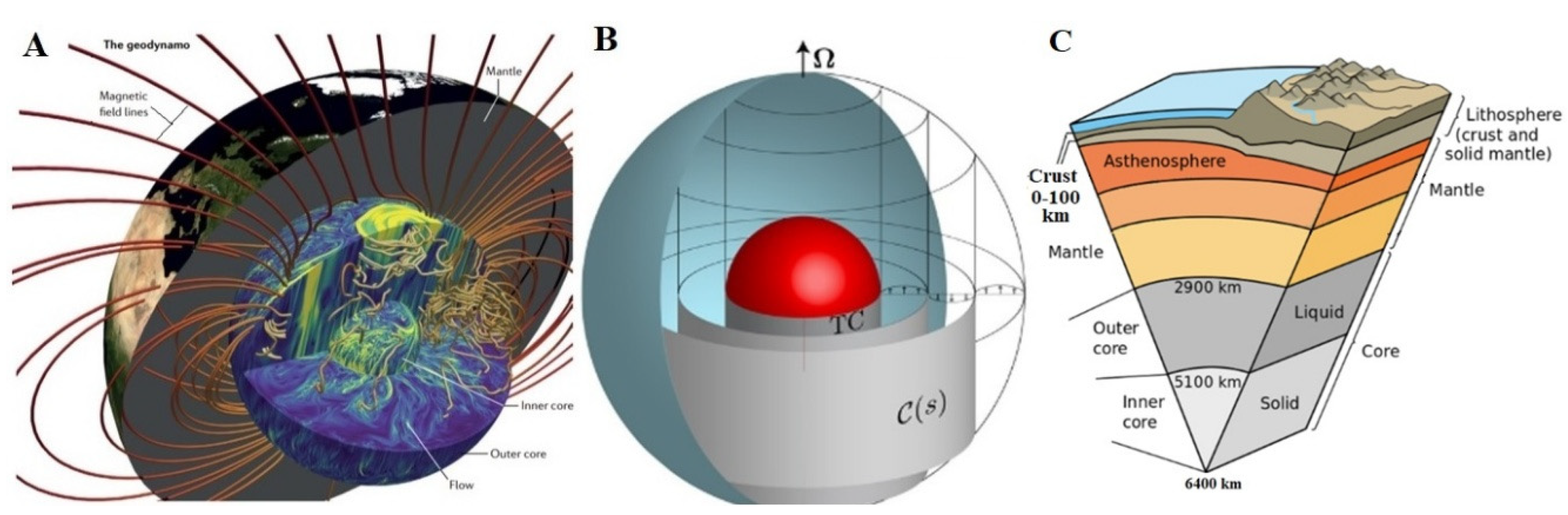

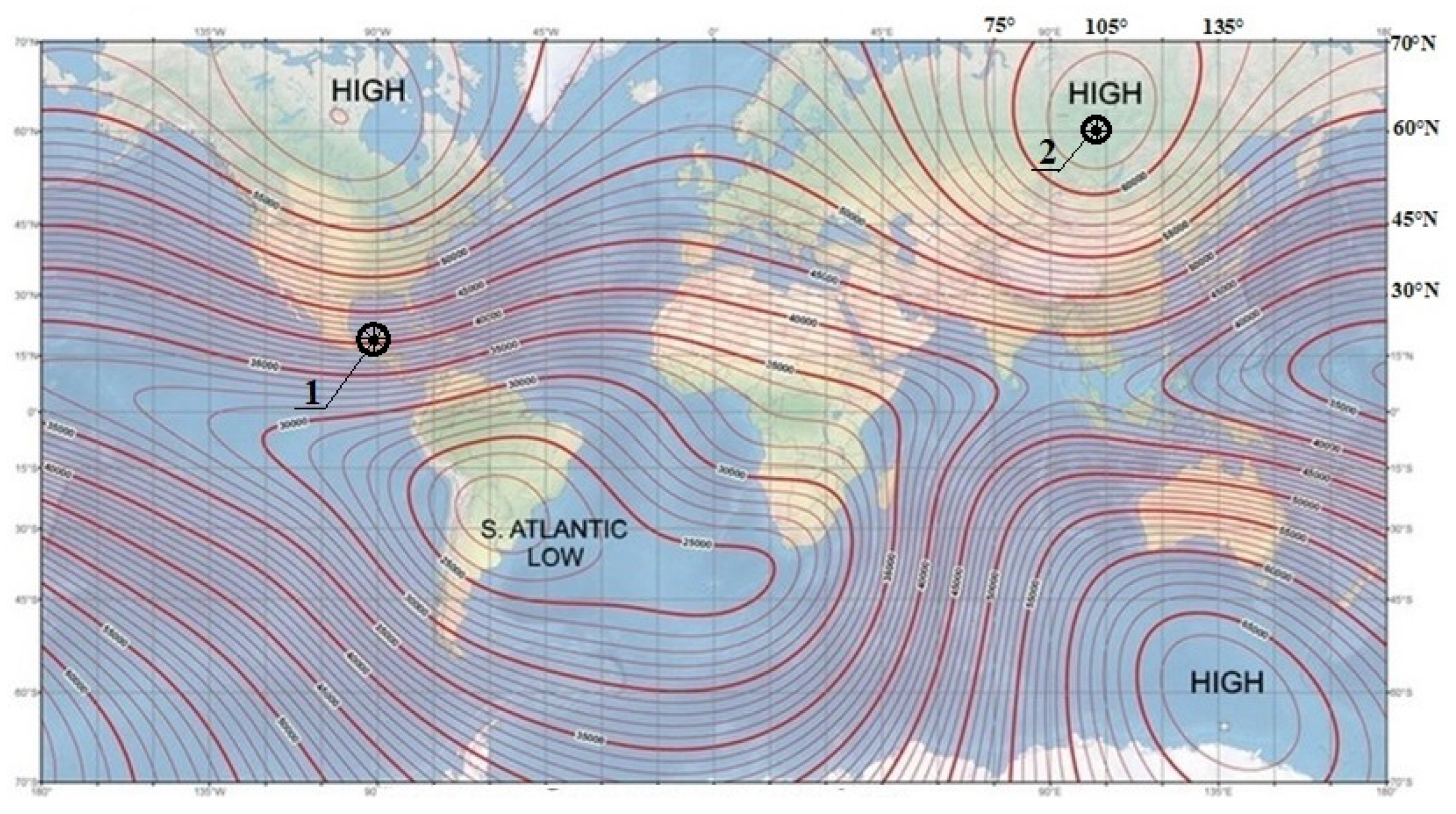

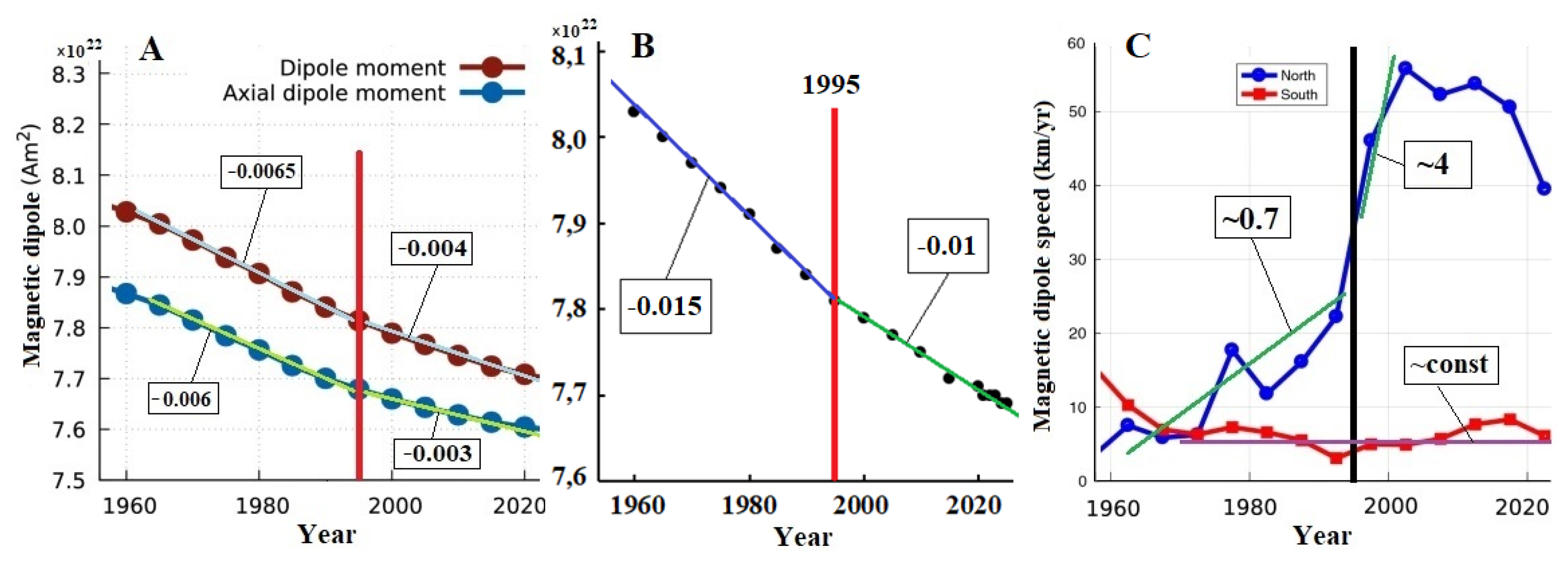

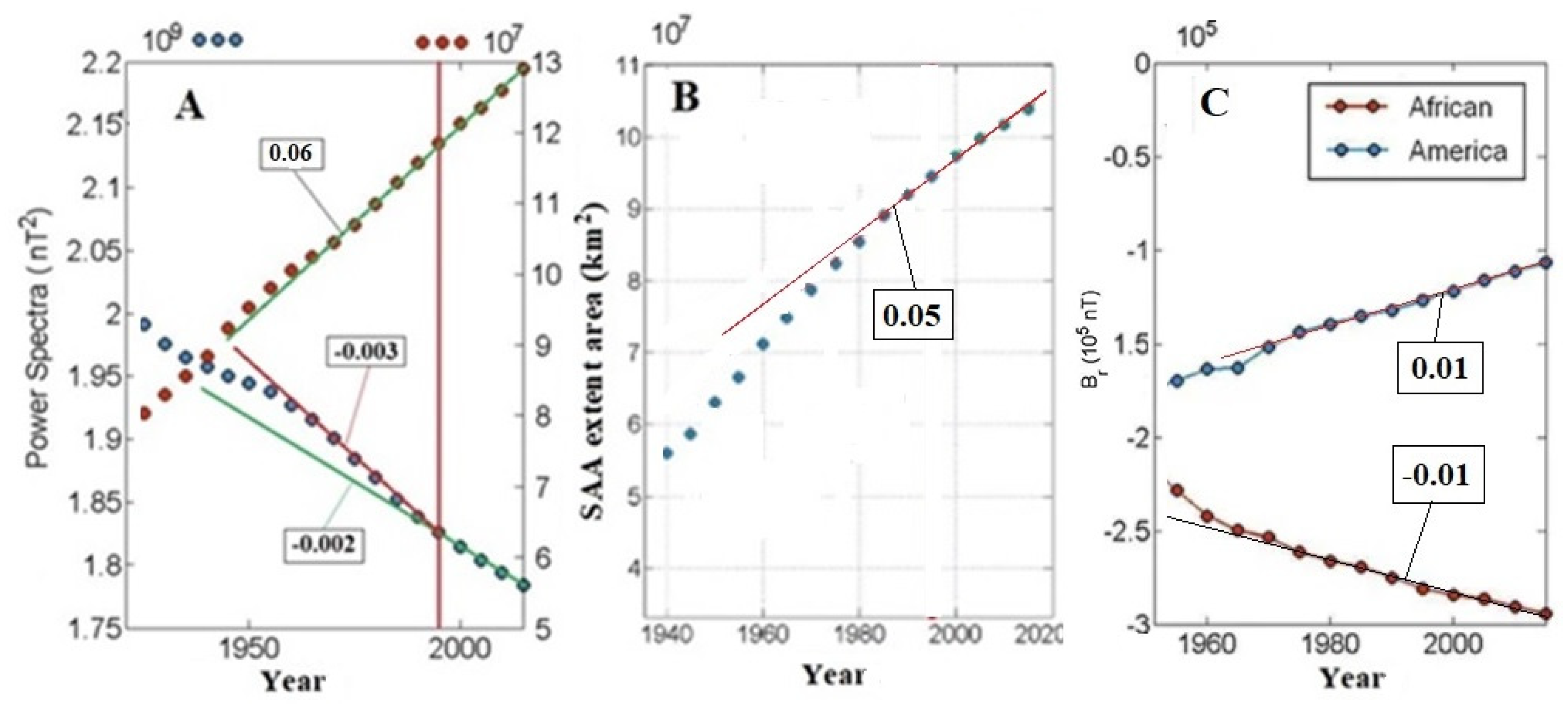

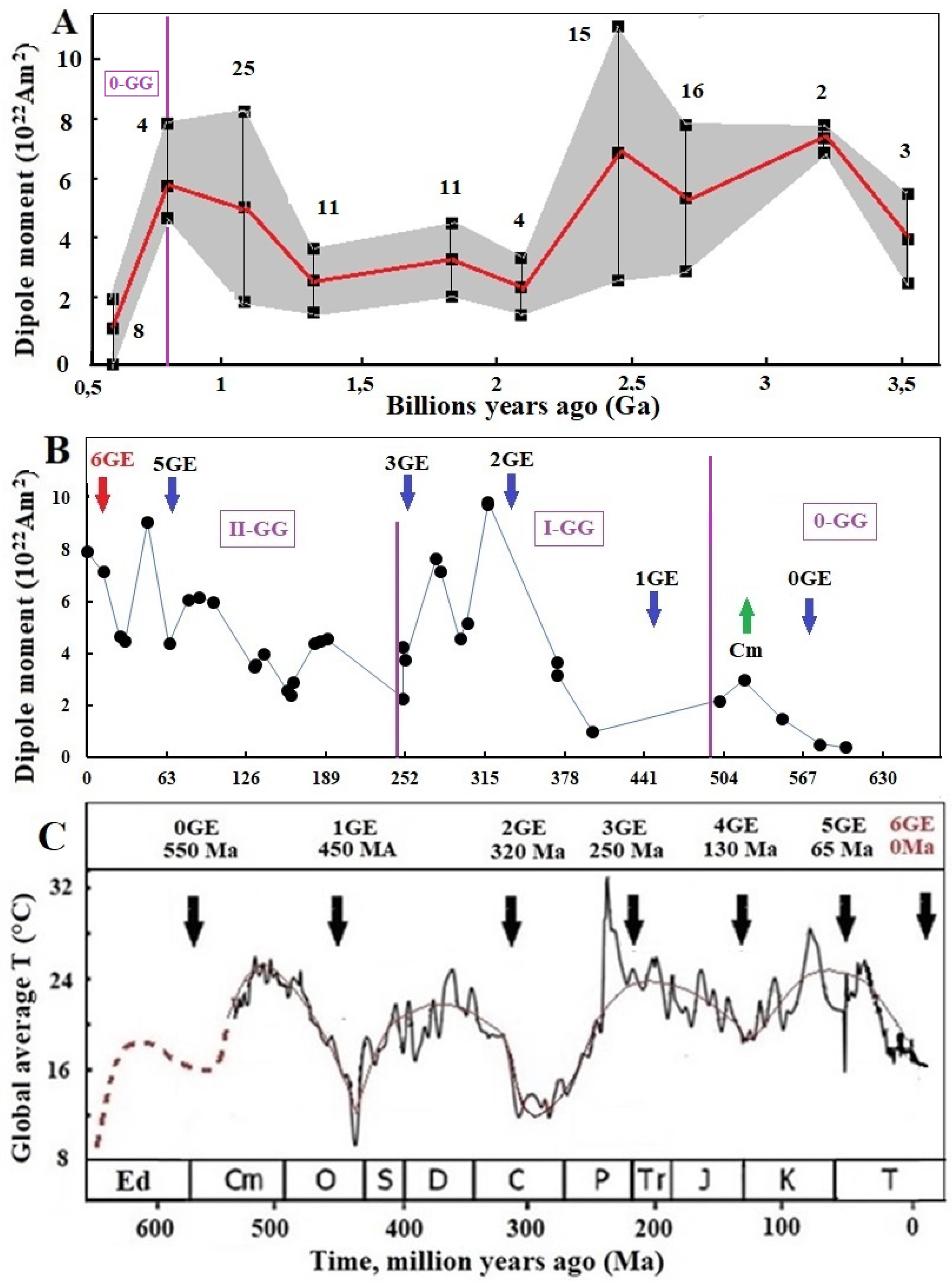

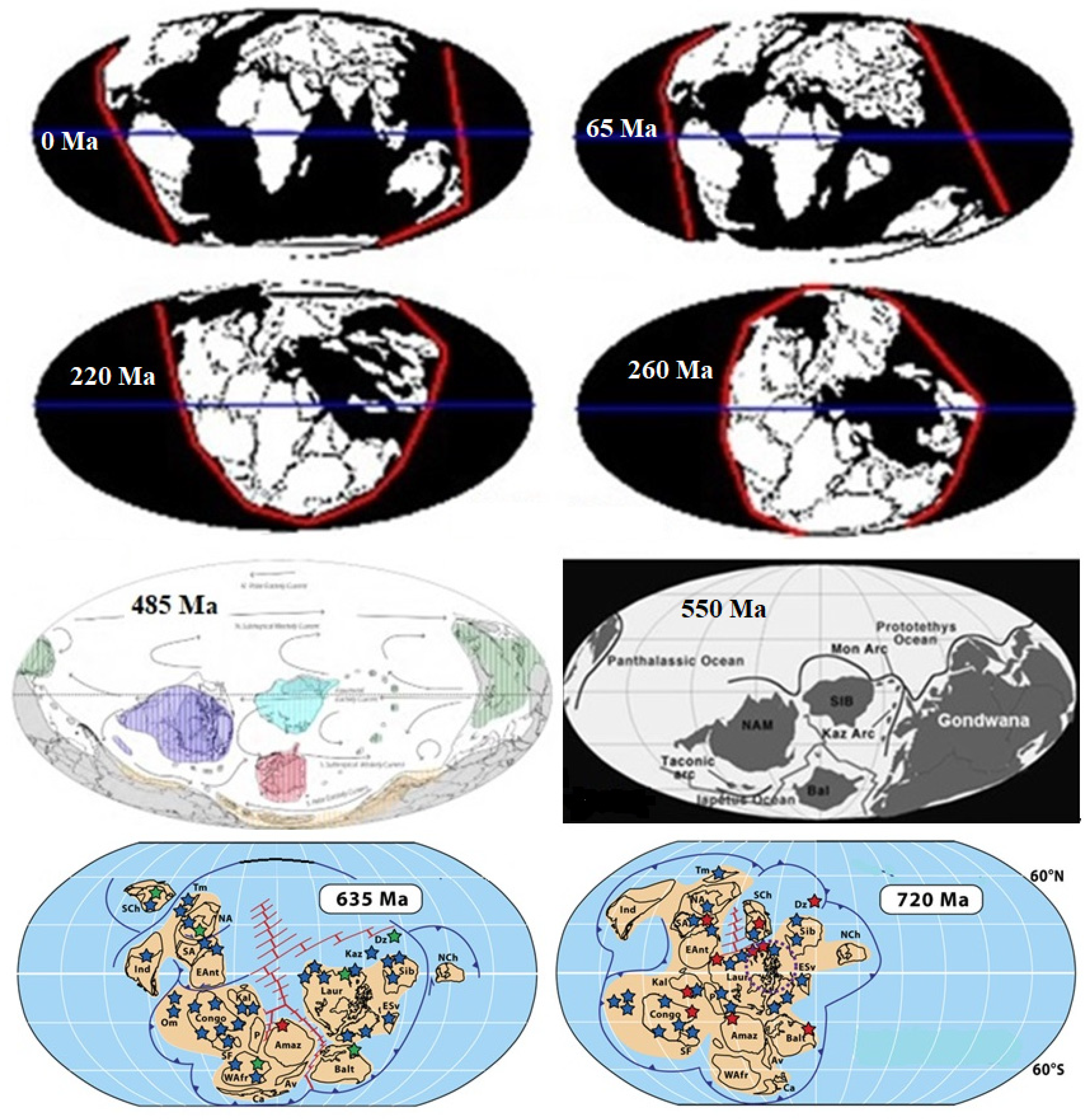

3.4.2. Lithosphere and Geomagnetism

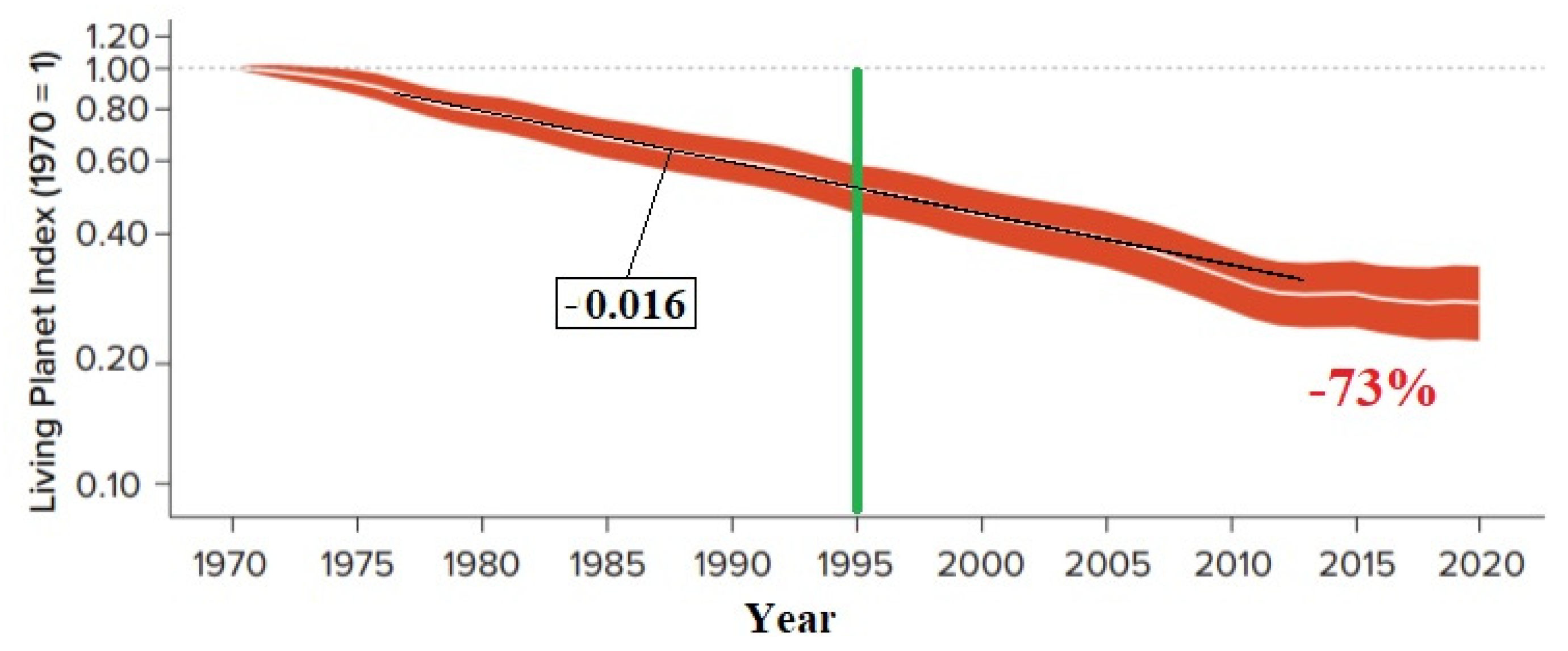

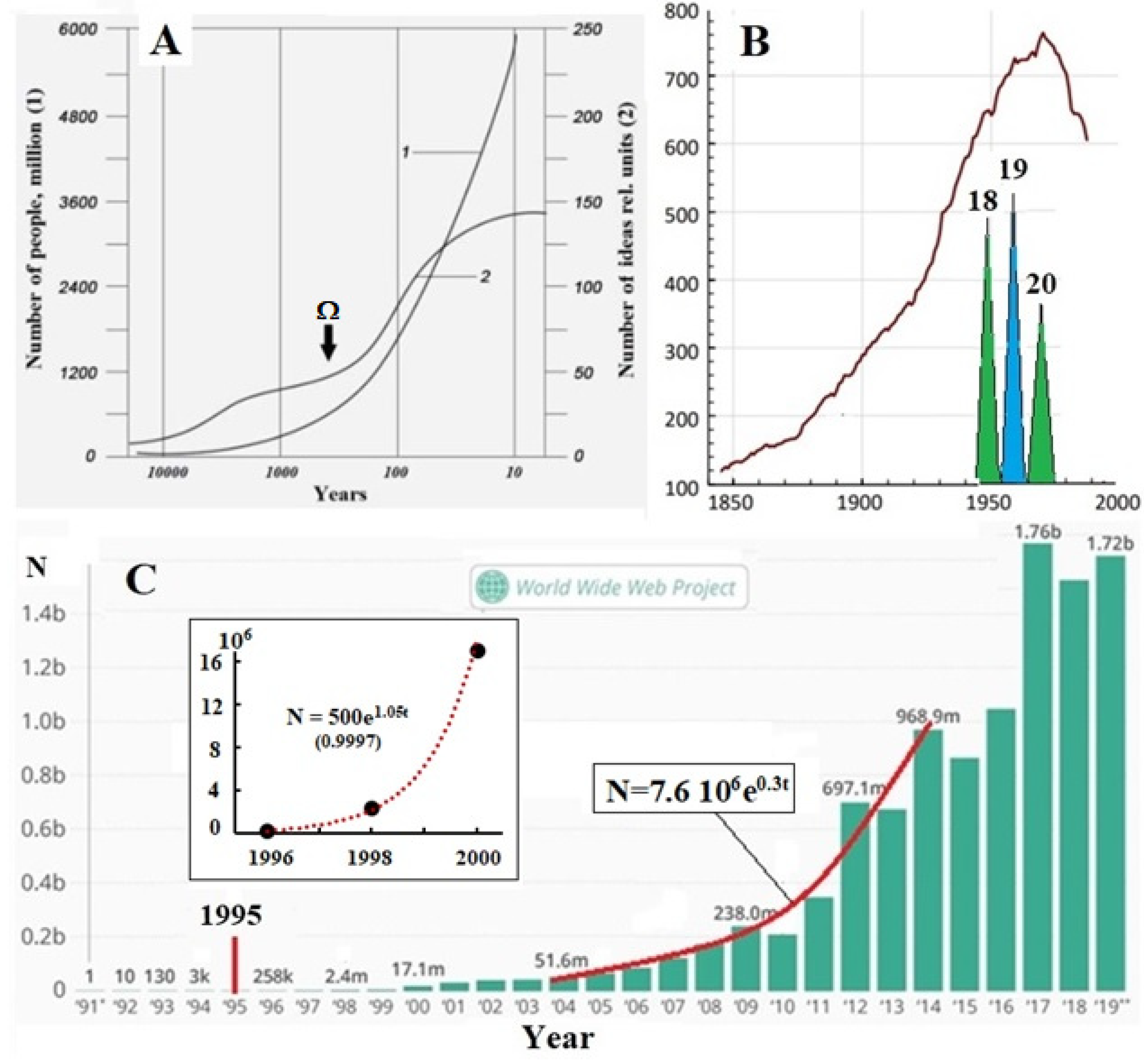

3.4.3. Biosphere

3.4.4. Magnetism of Human Brain

4. Conclusions

References

- Abyssal zone, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abyssal_zone.

- Alken, P. , et al. (2021) International Geomagnetic Reference Field: the thirteenth generation. Earth Planets Space 73, 49. [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; et al. (2022). The role of copper homeostasis in brain disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23:13850. [CrossRef]

- Annoni E. et al., (2024) Enhanced quantum transport in chiral quantum walks, Quantum Information Processing, 23(4). [CrossRef]

- Arndt N. , Davaille A. (2013) Episodic Earth evolution Tectonophys. 609(8), 661. [CrossRef]

- Athar M., S.; et al. (2022) Status and perspectives of neutrino physics, Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 124(1):103947. [CrossRef]

- Babayev E.S., Allahverdiyeva А.А. (2005) Geomagnetic Storms and their Influence on the Human Brain Functional State, Revista CENIC Ciencias Biológicas, 36(Especial).

- Badalyan, O.G. , Obridko V.N. (2011) North–South asymmetry of the sunspot indices and its quasi-biennial oscillations, New Astron. 16, 357. [CrossRef]

- Bahcall J.N., et al. (1982) Standard solar models and the uncertainties in predicted capture rates of solar neutrinos, Rev. Mod. Phys. 54(3):767. [CrossRef]

- Barash M.S. (2019) Changes in the Geomagnetic Field and the Evolution of Marine Biota, Oceanology, 59(2) 235. [CrossRef]

- Barnosky, A. , et al. (2011) Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature, 471, 51. [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, P.; et al. (2012) Torsional oscillations in a global solar dynamo, Sol. Phys. [CrossRef]

- Bezrukikh M.M. et al. (2009) Age Physiology: (Physiology of Child Development), 416 p. http://lib.rus.ec/b/447096/read.

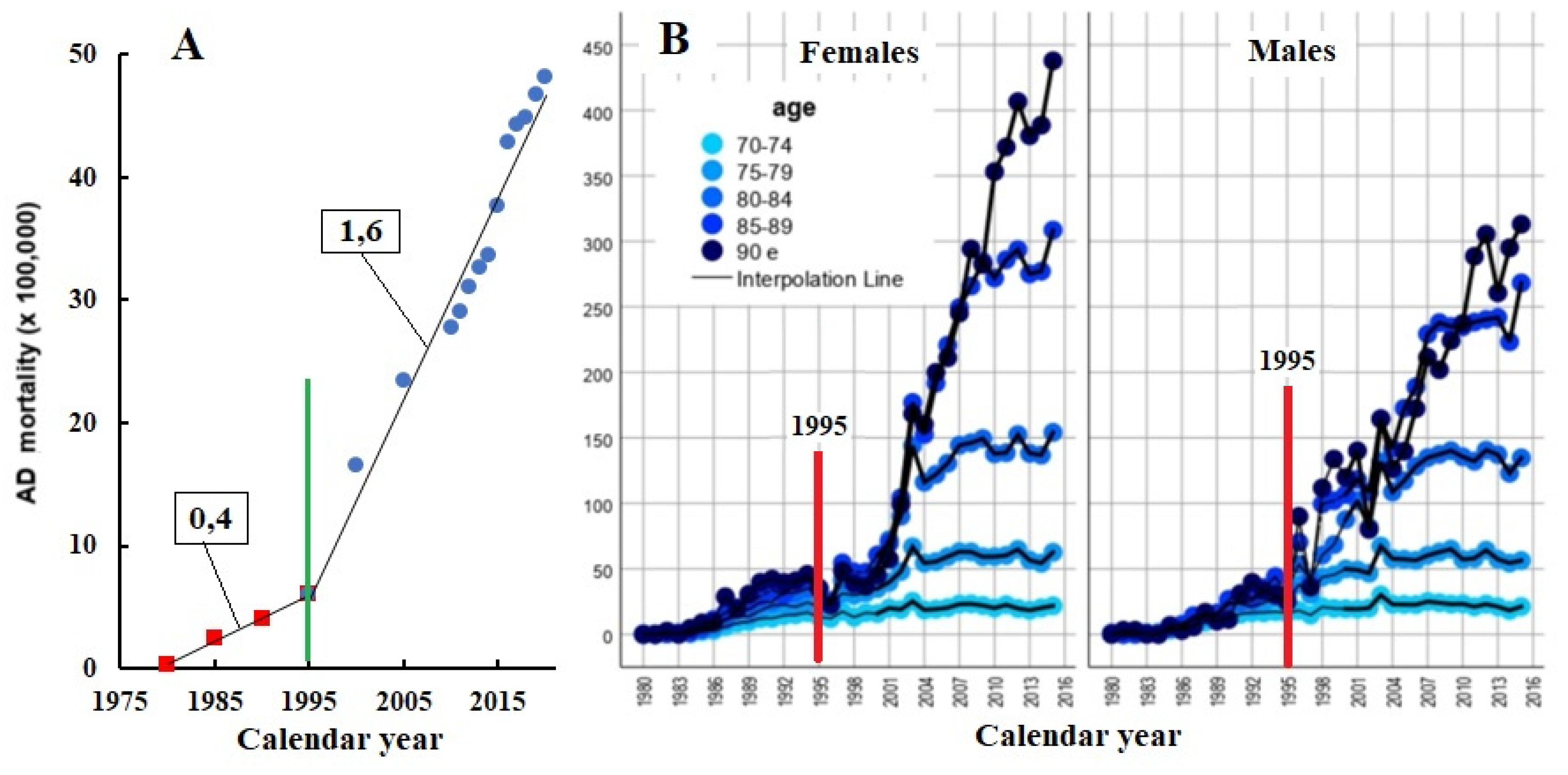

- Bezzini, D.; et al. (2024) Mortality of alzheimer’s disease in Italy from 1980 to 2015. Neurol. Sci. 45, 5731. [CrossRef]

- Biggin, A. J. , et al. (2015). Palaeomagnetic field intensityvariations suggest mesoproterozoic inner-core nucleation. Nature 526, 245. [CrossRef]

- Biggin A.J. et al. (2009) The intensity of the geomagnetic field in the late-Archaean: New measurements and an analysis of the updated IAGA palaeointensity database Earth Planets and Space 61(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Biggin A., J. , Thomas D. N. (2003) Analysis of long-term variations in the geomagnetic poloidal field intensity and evaluation of their relationship with global geodynamics, Geophys. J. Int. [CrossRef]

- Biodiversity Loss: The Sixth Mass Extinction Explained.

- Bloom, B.P.; et al. (2017) Chirality control of electron transfer in quantum dot assemblies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139: 9038. [CrossRef]

- Bloom N. et al., (2020) Online Appendix to Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find? Am. Economic Rev. 110(4): 1104, https://www.aeaweb.org/content/file?id=11806.

- Blunden J. (2020) Reporting on the State of the Climate in 2019.

- https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/reporting-state-climate-2019.

- Blunden, J.; et al. (2023) State of the Climate in 2022. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. [CrossRef]

- Bono, R.K.; et al. , (2019) Young inner core inferred from Ediacaran ultra-low geomagnetic field intensity, Nat. Geosci. 12, 143. [CrossRef]

- Breuer, H.-P. , Petruccione F. (2003) Concepts and methods in the theory of open quantum systems, Lecture Notes in Phys. [CrossRef]

- Brookes J.C. (2017) Quantum effects in biology: golden rule in enzymes, olfaction, photosynthesis and magnetodetection. Proc. R. Soc. A, 473: 20160822. [CrossRef]

- Buchachenko, A. (2024) Magnetic effects across biochemistry, Mol. Biology Environmental Chem. [CrossRef]

- Buffett B.A. (2007) Core-Mantle Interactions, Treatise Geophysics, 8. [CrossRef]

- Butler R., Tsuboi S. (2021) Antipodal seismic reflections upon shear wave velocity structures within Earth’s inner core, Phys. Earth Planet. Interiors 321(3–4):106802. [CrossRef]

- Cauley, P.W.; et al. (2019) Magnetic field strengths of hot Jupiters from signals of star–planet interactions. Nat. Astron. 3, 1128. [CrossRef]

- Cauwels, P. , Sornette D. (2020) Are ‘Flow of Ideas’ and ‘Research Productivity’ in secular decline? SFI, Research Paper, 20-90. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, G.; et al. Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Sci. Adv. 1(5) e1400253. [CrossRef]

- Chandler D., M. Langebroek, P. M. (2024) Glacial–interglacial circumpolar deep water temperatures during the last 800 000 years: estimates from a synthesis of bottom water temperature reconstructions, Clim. Past, 20, 2055. [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau, P.; et al. , (1999) Helioseismic constraints on the structure of the solar tachocline, Aph. J. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; et al. (2023) The emerging role of copper in depression, Front. Neurosci. 17. [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; et al. (2013) Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature, Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 024024. [CrossRef]

- Craig, D.J. (2019) What Everyone Needs to Know About the Threat of Mass extinction, https://magazine.columbia.edu/article/what-everyone-needs-know-about-threat-mass-extinction.

- Davies C.J., Constable C.G. (2020) Rapid geomagnetic changes inferred from Earth observations and numerical simulations. Nat Commun, 11, 3371. [CrossRef]

- Deng L. et al., (2013) Phase relationship between polar faculae and sunspot numbers revisited: wavelet transform analyses, Public. Astronom. Soc. Japan, 65(1):11. [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, A.; et al. (2023) Synthesis of Single Crystals of ε-Iron and Direct Measurements of Its Elastic Constants, Phys. Rev. Let. [CrossRef]

- Dodson, H.W.; et al. (1974) Comparison of activity in solar cycles 18, 19, and 20, Rev. Geophys. Space Phys. 12(3) 329. [CrossRef]

- Domingo V. (2009) Solar surface magnetism and irradiance on time scales from days to the 11-year cycle.

- Space Sci. Rev. (145) 337:. [CrossRef]

- Dorofeeva R., Duchkov A. (2022) Heat Flow variations in Siberia and neighboring regions: A new look, Int. J. Terrestrial Heat Flow and Applications 5(1):09-13. [CrossRef]

- Dvornyk, V.; et al. (2003) Origin and evolution of circadian clock genes in prokaryotes. PNAS. 100 (5): 2495. [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, R. , Ehrlich A., (2013) Can a collapse of global civilization be avoided? Proc. Biol. Sci. 280, 20122845. [CrossRef]

- El Nino 1997—1998, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1997–98_El_Niño_event.

- Enard, W.; et al. (2002) Molecular evolution of FOXP2, a gene involved in speech and language. [CrossRef]

- Esolen, A. (2020) The Suicide of a Civilization, Crisis Magazine, https://crisismagazine.com/opinion/the-suicide-of-a-civilization.

- Fedonkin, M.A. (2003) The origin of the Metazoa in the light of the Proterozoic fossil record, Paleontological Res. 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Fossat, E. (2014) Asymptotic g modes: Evidence for a rapid rotation of the solar core, Astron. Astrophys. [CrossRef]

- Fru, E.C.; et al. (2016) Cu isotopes in marine black shales record the Great Oxidation Event, PNAS USA. 113(18): 4941. [CrossRef]

- Gavelya, E.A. (2018) Electric currents in the evolutionary transformation of the Earth, St. Petersburg, 150. https://fis.wikireading.ru/9058.

- Giunti, C. , Studenikin A. (2015) Neutrino electromagnetic interactions: a window to new physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87. [CrossRef]

- Global reported natural disasters, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/natural-disasters-by-type.

- Glattfelder J.B. (2019) Volume II: The Simplicity of Complexity In book: Zum Performativen des frühen Dialogs. [CrossRef]

- Globus N., Blandford R.D., (2020) The chiral puzzle of life, ApJL, 895, L1, arXiv:1911.02525.

- Gnevyshev, M.N. (1977) Essential features of the 11-year solar cycle. Sol. Phys. 51, 175. [CrossRef]

- Hady, A.A. , (2013) Deep solar minimum and global climate changes, J. Adv. Res. [CrossRef]

- Hanasoge, S.M. (2022) Surface and interior meridional circulation in the Sun. Living Rev Sol Phys. 19, 3. [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, D.H. (2010) The Solar Cycle, Living Rev. Sol. Phys. [CrossRef]

- Heunemann, С.; et al. (2013) Direction and intensity of Earth’s magnetic field at the Permo-Triassic boundary: A geomagnetic reversal recorded by the Siberian Trap Basalts, Russia, Earth Planetary Sci. Let. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, P.F.; et al. (2017) Snowball Earth climate dynamics and Cryogenian geology–geobiology. Sci. Adv. 3, e1600983. [CrossRef]

- Hori, K. , et al. (2023) Jupiter’s cloud-level variability triggered by torsional oscillations in the interior. Nat. Astron. 7, 825. [CrossRef]

- Hotta, H. , et al. (2021) Solar differential rotation reproduced with high-resolution simulation. Nat. Astron. 5, 1100. [CrossRef]

- Hung C.-C. (2007) Apparent Relations Between Solar Activity and Solar Tides Caused by the Planets. NASA report/TM-2007-214817. http://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20070025111.

- Ingersoll, A. , Kanamori H. (1995) Waves from the collisions of comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 with Jupiter. Nature, 374, 706. [CrossRef]

- Impact events on Jupiter, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comet_Shoemaker–Levy_9.

- (2018) Space weather and specific features of the development of current solar cycle, Geomagnet. Aeronomy, 58(6) 753. Aeronomy, 58(6) 753. [CrossRef]

- Isozaki, Y.; et al. (2014) Beyond the cambrian explosion: From galaxy to genome, Gondwana Res. 25(3) 881. [CrossRef]

- Javaraiah, J. (2020) Long-term periodicities in North–south asymmetry of solar activity and alignments of the giant planets. Sol. Phys. 295, 8. [CrossRef]

- Javaraiah J. (2021) North-South asymmetry in solar activity and solar cycle prediction, V: Prediction for the North-South asymmetry in the amplitude of solar cycle 25. [CrossRef]

- Jeong E.J., Edmondson D. (2020) Measurement of neutrino’s magnetic monopole charge, vacuum energy and cause of quantum mechanical uncertainty, Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; et al. (2019) Terrestrial heat flow of continental China: Updated dataset and tectonic implications, Tectonophys. [CrossRef]

- Johnson G., C. , Lumpkin R., (2023) Global Oceans, Online Supplement, to Bul. Am. Meteorolog. Soc. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.C. , Purkey S.G. (2024) Refined estimates of global ocean deep and abyssal decadal warming trends, Geophys. Res. Let. 51(18). [CrossRef]

- Jupiters Orbit, https://flight-light-and-spin.com/n-body/jupiter.htm.

- Katila, T. , Varpula T. (1983) Magnetic fields of the eye. In: Biomagnetism. Springer, Boston, MA. [CrossRef]

- Kawano, T.; et al. (2010) Heat content change in the Pacific Ocean between the 1990s and 2000s. Deep-Sea Res. II, 57, 1141. [CrossRef]

- Kent D.V. et al. (2018) Empirical evidence for stability of the 405-kiloyear Jupiter–Venus eccentricity cycle over hundreds of millions of years, PNAS, 115 (24) 6153. [CrossRef]

- Khabarov CV, Sterlikova ON. (2022) Melatonin and its role in circadian regulation of reproductive function. Vestnik novih medicinskih tehnologii. 29(3):17. [CrossRef]

- Kholmanskiy A. (2024) Probable physical factors of anthropogenesis, EcoEvoRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Kholmanskiy A. (2024a) Probable chiral factor of anthropogenesis, Asymmetry, 18(4) 10. [CrossRef]

- Kholmanskiy A., (2023) Role of water in physics of blood and cerebrospinal fluid, arXiv:2308.03778.

- Kholmanskiy A. (2023a) Connection of brain glymphatic system with circadian rhythm, bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Kholmanskiy A. (2021), Synergism of dynamics of tetrahedral hydrogen bonds of liquid water Phys. Fluids 33(6):067120. [CrossRef]

- Kholmanskiy, et al. (2021а) Thermal stimulation neurophysiology of pressure phosphenes, bioRxiv.

- https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.12.435166.

- Kholmanskiy, A. , (2019) Dialectic of Homochirality. Preprints, 2019060012, https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/201906.0012/v1.

- Kholmanskiy, A. (2019a) Biology and Demography of Creative Potential. Preprints.

- https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints201907.0198.v1.

- Kholmanskiy, A. (2019b) Alzheimer’s in Post-Industrial Epoch, Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Kholmanskiy, A. (2019c) The supramolecular physics of the ambient water, https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1912/1912.12691.pdf.

- Kholmanskiy, A.S. (2018) Activation of biosystems by external chiral factor and temperature reduction Asymmetry, 12(3) http://cerebral-asymmetry.ru/Holmansky_3_2018.pdf.

- Kholmanskiy, A.S. (2018a) Chiral physics of the human brain, Math. Morphology electronic math. medical-biological J. 17(2) WFLQPA.

- Kholmanskiy, A.S. (2017) Structure of nucleus and periodic law of Mendeleev. Electron. Math. Med.-Biol. J. [CrossRef]

- Kholmanskiy A.S. (2016) Chirality anomalies of water solutions of saccharides, JML, 216:683.

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2016.02.006.

- Kholmanskiy A. (2011) Neutrinos in condensed matter, Bulletin Russian Spirit, 1, 50. https://rusneb.ru/catalog/000199_000009_004968707/.

- Kholmanskiy, A.S. (2011a) Theophysics pro physics, Consciousness and physical reality. 16(11) 2. http://www.sciteclibrary.ru/rus/catalog/pages/11031.html.

- Kholmanskiy A. (2007) Facets of Solar Physics, Ibid, 4(2) 2209, abs | html | pdf.

- Kholmanskiy, A. (2006) Modeling of brain physics. Mathematical morphology. Electronic mathematical and.

- Medico-biological journal. 5 (4). [CrossRef]

- Kholmanskiy A. (2004) Cross of Sun, SciTecLibrary, https://kazedu.com/referat/64261.

- Kholmansky, A.S. (2003) Fractal-resonance principle of operation “MIS-RT”, 29-2. https://www.eng.ikar.udm.ru/sb/sb29-2.htm.

- Kizel’, V. A. Physical causes of dissymmetry of living systems, 1985, 120.

- Klevs, M.; et al. (2023) A Synchronized Two-Dimensional α-Ω Model of the Solar Dynamo. Sol.Phys. 298(7):90. [CrossRef]

- Krivova N. A. (2021) Modelling the evolution of the Sun’s open and total magnetic flux, A&A 650, A70. [CrossRef]

- Landeau, M.; et al. (2022) Sustaining Earth’s magnetic dynamo, Nat. Rev. [CrossRef]

- Laskar, J.; et al. , (2011) La2010: A new orbital solution for the long-term motion of the Earth. Astron. Astrophys. 532, 81. [CrossRef]

- Lattimer J. M., Prakash M. (2004) The Physics of Neutron Stars, Sci. 304(5670):536. [CrossRef]

- Leong S. Period of the Sun’s Orbit around the Galaxy (Cosmic Year). Phys. Factbook (2002).

- Letuta, U.G.; et al. (2017) Enzymatic mechanisms of biologicalmagnetic sensitivity, Bioelectromagnetics, 38, 511e521. [CrossRef]

- Levitus, S.; et al. , (2012) World ocean heat content and thermosteric sea level change (0–2000 m), 1955–2010, Geophys. Res. Let. 39(L10603) 1. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; et al. (2018) Nuclear spin attenuates the anesthetic potency of xenon isotopes in mice. Anesthesiology, 129, 271. [CrossRef]

- Lindsey R., Dahlman L., (2023) Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content, NOAA Climate.

- https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-ocean-heat-content.

- Livshits I., Obridko V.N., (2006) Variations of the dipole magnetic moment of the Sun during the solar activity cycle, Astronomy Reports, 50(11): 926. [CrossRef]

- Lupovitch, J. (2004) In The blink of an eye: how vision sparked the big bang of evolution, Arch. Ophthalmol. 124(1):142. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, T. , et al. (2014) The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature, 506, 307. [CrossRef]

- Markina, N.V. (2008) Riddles and Contradictions of the Creative Brain, Chem. Life. 11, http://elementy.ru/lib/430728.

- Magnetic dipoles of the Sun and planets, https://www.physicsforums.com/threads/dipole-moments-of-the-planets-and-the-sun.268157/.

- Manda, S.; et al. , (2020) Sunspot area catalog revisited: Daily cross-calibrated areas since 1874, Astron. Astrophys. 640 A78. [CrossRef]

- Mareschal J.-C., Jaupart C. (2013) Radiogenic heat production, thermal regime and evolution of continental crust, Tectonophysics 609: 524. [CrossRef]

- Matyushin, G.N. Three Million Years BC. Moscow: 1986. 155; https://search.rsl.ru/ru/record/01001325394.

- Maurya R.A., Ambastha A. (2020) Magnetic and Velocity Field Topology in Active Regions of Descending Phase of Solar Cycle 23. Sol. Phys. 295, 106. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.K. (1954) Selected Works on the Theory of the Electromagnetic Field, Moscow, 688 p.

- Michel, S. , Meijer J.H., (2019) From clock to functional pacemaker, Eur. J. [CrossRef]

- Milankovitch cycles, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milankovitch_cycles.

- Moore, K.M.; et al. (2018) A complex dynamo inferred from the hemispheric dichotomy of Jupiter’s magnetic field. Nature, 561, 76. [CrossRef]

- Nandy D. (2012) All Quiet on the Solar Front: Origin and Heliospheric Consequences of the Unusual Minimum of Solar Cycle 23, Sun and Geosphere,7(1): 16.

- Nandy, D.; et al. (2021) Solar evolution and extrema: current state of understanding of long-term solar variability and its planetary impacts. Prog. Earth. Planet. Sci. 8, 40. [CrossRef]

- Nataf, H.C. (2023) Response to Comment on “Tidally Synchronized Solar Dynamo: A Rebuttal”. Sol Phys, 298, 33. [CrossRef]

- Nemilov, S.V. (2011) Optical Materials Science: Optical Glasses. Textbook, course of lectures.

- Ness, N. F.; et al. (1986) Magnetic Fields at Uranus, Sci., 233(4759) 85. [CrossRef]

- Nimmo F., (2015) Energetics of the Core, Treatise on Geophysics, 8, 27. [CrossRef]

- Obridko, V.N.; et al. (2020) Cyclic variations in the main components of the solar large-scale magnetic field, MNRAS 492(4), 5582. [CrossRef]

- Obridko V., N.; et al. (2024) Is There a Synchronizing Influence of Planets on Solar and Stellar Cyclic Activity? Sol. Phys. 299, 124. [CrossRef]

- Okhlopkov, V.P. (2020) 11-Year Index of Linear Configurations of Venus, Earth, and Jupiter and Solar Activity. Geomagn. Aeron. 60, 381. [CrossRef]

- Ou H.-W. (2025) Tropical Glaciation and Glacio-Epochs: Their Tectonic Origin in Paleogeography Climate 13(1) 9. [CrossRef]

- Pavón-Carrasco F., J. , Santis A. De (2016) The South Atlantic Anomaly: The key for a possible geomagnetic reversal, Front. Earth Sci. 4. [CrossRef]

- Pétrélis, F.; et al. (2009) Simple Mechanism for Reversals of Earth’s Magnetic Field, Phys. Rev. Let. 102, 144503. [CrossRef]

- Pétrélis, F.; et al. (2011) Plate tectonics may control geomagnetic reversal frequency, Geophys. Res. Let. [CrossRef]

- Pipin, V.V. (2014) Reversals of the solar magnetic dipole in the light of observational data and simple dynamo models, Astr. Astrophys. 567. [CrossRef]

- Planets Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus at perihelion and at aphelion 1900–2200, https://stjerneskinn.com/planet-apsides.htm.

- Pollack H., N. , et al. (1993), Heat-flow from the earth’s interior—analysis of the global data set, Rev. Geophys. [CrossRef]

- Paleozoic Time, http://www.fossilmuseum.net/Geological_History/PaleozoicGelogicalHistory.htm.

- Puetz S.J., Borchardt G. (2015) Quasi-periodic fractal patterns in geomagnetic reversals, geological activity, and astronomical events, Chaos Solitons & Fractals, 81:246. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, E.; et al. (2020) Iodine levels in different regions of the human brain, J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 62:126579. [CrossRef]

- Purkey S., G. , Johnson G. C. (2010): Warming of global abyssal and deep Southern Ocean waters between the 1990s and 2000s: Contributions to global heat and sea-level rise budgets. J. Climate, 23, 6336. [CrossRef]

- Rhein, M.; et al. (2013) Observations: Ocean; Climate Change: https://www.climatechange2013.org/images/report/WG1AR5_Chapter03_FINAL.pdf.

- Redman, K.; et al. (2016) Iodine deficiency and the brain: effects and mechanisms, Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 56(16):2695. [CrossRef]

- Ridge, P.G.; et al. (2008.) Comparative genomic analyses of copper transporters and cuproproteomes reveal evolutionary dynamics of copper utilization and its link to oxygen, PLoS ONE. 3(1): e1378. [CrossRef]

- Roberts P., H. , King E. (2013) On the genesis of the Earth’s magnetism, Reports Progress Phys. 76(9):096801. [CrossRef]

- Ruiyang S. (2022) CO2 buildup drove global warming, the Marinoan deglaciation, and the genesis of the Ediacaran cap carbonates. Precambrian Res. 383, 106891. [CrossRef]

- Salles, T. , et al. (2023) Landscape dynamics and the Phanerozoic diversification of the biosphere, Nature. 624(7990) 115. [CrossRef]

- Scafetta, N. (2023) Comment on “Tidally Synchronized Solar Dynamo: A Rebuttal” by Nataf (Solar Phys. 297, 107, 2022). Sol. Phys. 298, 24. [CrossRef]

- Schneider N., M. , Bagenal F. (2007) Io’s neutral clouds, plasma torus, and magnetospheric interactions, 265. [CrossRef]

- Schreiweis C. et., al. (2014) Humanized Foxp2 accelerates learning by enhancing transitions from declarative to procedural performance. PNAS USA. 111, 14253. [CrossRef]

- Schuckmann, K.; et al. , (2023) Heat stored in the Earth system 1960–2020: where does the energy go? Earth System Science Data 15(4):1675. [CrossRef]

- Scotese, C.R. (2024) The Cretaceous World: Plate Tectonics, Paleogeography, and Paleoclimate Geo. Soc. [CrossRef]

- Selmaoui, B. , Touitou Y. (2021) Association between mobile phone radiation exposure and thesecretion of melatonin and cortisol. Two markers of the circadian system: A Review, Bioelectromagnetics, 42, 5(17). [CrossRef]

- Semicheva, T.V. , Garibashvili A.Yu. (2000) Epiphysis: current data on physiology and pathology. Problems of Endocrinology. 46(4):38. [CrossRef]

- Sepkoski, J.J. (1984) A kinetic model of Phanerozoic taxonomic diversity. III. Post-Paleozoic families and mass extinctions. Paleobiology, 10, 246. [CrossRef]

- https://www.sci-hub.ru/10.1017/s0094837300008186.

- Shapiro, A.I.; et al. (2017) The nature of solar brightness variations. Nat Astron 1, 612–616. [CrossRef]

- Shaviv N., J. (2008) Using the oceans as a calorimeter to quantify the solar radiative forcing, J. Geophys. Res., 113, A11101. [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakova, V.V.; et al. (2021) Ultra-Low Geomagnetic Field Intensity in the Devonian Obtained from the Southern Ural Rock Studies. Izv., Phys. Solid Earth, 57, 900. [CrossRef]

- Sheeley N., R. Jr (2010) What’s so peculiar about the cycle 23/24 solar minimum? [CrossRef]

- Silvera, I.F. , Dias R. (2021) Phases of the hydrogen isotopes under pressure: metallic hydrogen, Adv. Phys. X 6(1):1961607. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; et al. , (2012) Wireless transmission of electrical power overview of recent research & development, Int. J. Comp. Electrical Engineering, 4(2) http://ijcee.org/papers/480-N015.

- Sivaraman, K.R. , (2010) Are Polar Faculae Generated by a Local Dynamo? Astrophys. Space Sci. Proceed. 386. [CrossRef]

- Solanki S., K.; et al. (2013), Solar irradiance variability and climate, ARA&A, 51, 311. [CrossRef]

- Sorokhtin, O.G. , et al., (2010) Theory of Earth Development (Origin, Evolution and Tragic Future). Institute Computer Studies, Izhevsk, 751.

- Space Weather, https://www.spaceweatherlive.com/en/solar-activity/solar-cycle.html.

- Spencer, C.J.; et al. (2018) A Palaeoproterozoic tectono-magmatic lull as a potential trigger for the supercontinent cycle. Nature Geosci, 11, 97. [CrossRef]

- XX.

- Stefani, F.; et al. , (2024) Rieger, Schwabe, Suess-de Vries: The Sunny Beats of Resonance, Sol. Phys. [CrossRef]

- Strugarek, A.; et al. (2017) Reconciling solar and stellar magnetic cycles with nonlinear dynamo simulations, Sci. 357(6347) 185. [CrossRef]

- Strugarek, A.; et al. , (2023) Dynamics of the Tachocline, Space Sci. Rev. 21. [CrossRef]

- Takalo, J. (2023) Analysis of the Solar Flare Index for Solar Cycles 18–24: Extremely Deep Gnevyshev Gap in the Chromosphere Sol. Phys. [CrossRef]

- Tateno, S.; et al. (2010) The structure of iron in Earth’s inner core, Sci. 330, 359. [CrossRef]

- Tesla, N. , Diaries. 1899-1900 https://ivanik3.narod.ru/Tesla/tesla-kolorado1899-1900.pdf.

- Thallner, D.; et al. (2021), New paleointensities from the skinner cove formation, Newfoundland, suggest a changing state of the geomagnetic field at the Ediacaran-Cambrian Transition, J. Geophys. Res. [CrossRef]

- Thermalinfo.ru, http://thermalinfo.ru/svojstva-zhidkostej/voda-i-rastvory/teploprovodnost-i-plotnost-vody-teplofizicheskie-svojstva-vody-h2o.

- Toma, G. , et al. (2009) Solar cycle 23: an unusual solar minimum? AIP Conf Proc, 1216, 667. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. , Zhang H. (2012) Large-scale magnetic helicity fluxes estimated from mdi magnetic synoptic charts over the solar cycle 23, Ap. J. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. , Song X. (2023) Multidecadal variation of the Earth inner-core rotation. 16(2) 1. [CrossRef]

- UAN satellite-based temperature, http://iwantsomeproof.com/cllgraphs/uah_sc.asp.

- Vidotto, A.A.; et al. (2018) The magnetic field vector of the Sun-as-a-star—II. Evolution of the large-scale vector field through activity cycle 24, MNRAS. [CrossRef]

- Varela, J.; et al. (2023) On Earth’s habitability over the Sun’s main-sequence history: joint influence of space weather and Earth’s magnetic field evolution, Monthly Notices Royal Astronom. Soc. [CrossRef]

- Valko et al. (2005) Metals, Toxicity and Oxidative Stress. Current Med. Chem. 12(10), 1161.

- Veselovskiy, R.V.; et al. (2024) Paleomagnetism and geochronology of 2.68 Ga dyke from Murmansk craton, NE Fennoscandia: new data for Earth’s magnetic field regime in the neoarchean, Izv. Phys. Solid Earth, 60(4) 772. [CrossRef]

- Volodyaev I., Beloussov L. (2015) Revisiting the mitogenetic effect of ultra-weak photon emission.

- Front Physiol. 6:241. [CrossRef]

- Wang W. et al. (2024) Inner core backtracking by seismic waveform change reversals, Nature 631(8020) 1. [CrossRef]

- Weisshaar E. et al. (2023) No evidence for synchronization of the solar cycle by a “clock”, A&A, 671, A87. [CrossRef]

- Westerhold, T.; et al. (2020) An astronomically dated record of Earth’s climate and its predictability over the last 66 million years, Science. 369(6509) 1383. [CrossRef]

- Wilson I., R. , (2013) The Venus-Earth-Jupiter spin-orbit coupling model, Pattern Recognition in Phys. 1(1):147. [CrossRef]

- WWF (2024) Living Planet Report, A System in Peril. https://www.wwf.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-10/living-planet-report-2024.pdf.

- Zadeh-Haghighi, H. , Simon C. (2022) Magnetic field effects in biology from the perspective of the radical pair mechanism J. Roy. Soc. [CrossRef]

- Zangieva, Z.K.; et al. (2013) Comparative analysis of microelement profiles of 10 parts of the brain in ischemic stroke and without ischemic damage, Zemsky Vrach J. 4, 21.

- Zhang, B.; et al. (2023) Biophysical mechanisms underlying the effects of staticmagnetic fields on biological systems, Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 177 14e23. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. , Yang S. (2013) Distribution of magnetic helicity flux with solar cycles, ApJ. 763(2):105. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; et al. (2021) Earth-affecting solar transients: a review of progresses in solar cycle 24, Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. (2017) On a possible giant impact origin for the colorado plateau. arXiv:1711.03099.

- Zhang, X.; et al. (2014) Triggers for the Cambrian explosion: Hypotheses and problems. Gondwana Res. 25 (3), 896. [CrossRef]

- Zerbo, J.-L.; et al. (2013) Geomagnetism during solar cycle 23: Characteristics, J. Adv. Res. [CrossRef]

- Zhukova, A. (2024) Hemispheric analysis of the magnetic flux in regular and irregular solar active regions, MNRAS, 532(2) 2032. [CrossRef]

- Zhukova, A. (2023) The North–South asymmetry of the number and magnetic fluxes of active regions of different magneto-morphological types in cycles 23 and 24. Proceed. Int. Astronom. Union. 19(S365) 154. [CrossRef]

- Zwaan, C. (1978) On the appearance of magnetic flux in the solar photosphere. Sol. Phys. 60, 213. [CrossRef]

| Sun, Planet | Y (year) (yer) | Mass | m*) | RP (AU) | Tides | Magnetic | Pm/Pt |

| Sun | - | 3.3 105 | 4.4 106 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Mercury | 0.24 | 0.06 | 4.7 10-4 | 0.31-0.47 | 0.55-1.85 | 7 10-3 | 10-3 |

| Venus (V) | 0.62 | 0.82 | 1.0 10-5 | 0.72 | 2.2 | 2.7 10-5 | 10-5 |

| Earth (E) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mars | 1.88 | 0.11 | 2.6 10-5 | 1.52 | 0.03 | 7 10-6 | 10-4 |

| Jupiter (J) | 11.86 | 318 | 1.9 104 | 4.95-5.46 | 2.0-2.7 | 140 | 70 |

| Saturn | 164.8 | 95 | 576 | 9.54 | 0.11 | 0.66 | 6 |

| Uran | 84 | 14.5 | 50 | 19 | 2 10-3 | 7 10-3 | 3 |

| Neptun | 164 | 17,1 | 30 | 30 | 0.5 10-3 | ~1 10-3 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).