1. Introduction

Electric vehicles (EVs) hold definite advantage over other traditional energy-saving technologies for its ease of implementation while ensuring an eco-friendly environment. In recent years, the sales of EVs are rising year by year in many countries in the world, including Denmark. Besides the increased public awareness to carbon emission, the policy encouragement of the legislature plays another important role. For EVs registered before 2026, only 40% of the calculated tax for ordinary cars must be paid in Denmark, with a full tax gradually phased in by 2035. The full tax of vehicle registration is calculated by 25% of the vehicle's value up to DKK 65,800, then 85% of the remaining value up to DKK 204,600, and 150% of the rest. EVs also benefited from a basic registration tax deduction of DKK 165,500 from February to the end of 2024 [

1]. As a result, it is worth noting that EVs has taken over 51.1% market share in new car registrations in Denmark’s automotive market in 2024 [

2].

In 2024, Denmark significantly expanded its public charging infrastructure, adding many fast chargers to support the rising number of EVs. However, the rapid increasing number of EVs poses a great challenge to the local low-voltage (LV) distribution network. Among various low-carbon technologies on household-level, such as photovoltaics, heat pumps, et al., it is pointed out that EVs have the highest unitary impact on the network, especially on the MV/LV transformers [

3]. Meanwhile, it is also proposed that EVs provoked mainly cable over-loading [

4]. The situation in urban grids is still acceptable, no voltage violations or cable overloading issues are observed in most cases, except transformer overloading during an extreme winter scenario [

5]. But in rural distribution grids, transformer overloading is found to be the worst issue [

6]. Except overloading issues, Procopiou [

7] presents voltage drop issues caused by high EV penetration in residential low voltage networks. Besides, numerous EV charging can also have the negative impact on LV distribution system such as phase imbalance [

8], increasing the distribution system losses [

9], harmonics distortion and power quality issues [

10].

In order to adapt to the surge in EV adoption, one starting point is to reinforce the grid, for example, upgrading the capacity of existing distribution system components, especially transformers and power cables. However, it is argued that the costs and emissions of grid reinforcements outweigh the benefits in costs and emissions in EV charging optimization resulting from increased grid capacity [

11]. From another starting point, if the charging scheme of each EV can be coordinated, the burden of load on local distribution system can also be alleviated. Therefore, implementing effective charging control and coordination strategy will be crucial for the future grid as shown by several studies. [

12] proposes an adaptive control algorithm for plug-in EV charging without straining the power system. [

13] presents a centralized smart charge/discharge scheduling algorithm to achieve peak shaving and valley filling of the grid load. [

14] proposes an optimization algorithm for smart EV charging to reduce the overall net-load variance through a more efficient exploitation of the available PV power and EV charging shifting to enhance the stability of power grid. [

15] adopts a coordinated charging strategy for EVs to positively affects voltage phase imbalance in distribution system. [

16] proposes a framework for coordinated unbalance compensation and harmonic mitigation of distribution networks for daily operations through the charging management of EVs. The above solutions can alleviate the strains on the distribution system, but they focus on the grid side instead of customer side. It is also necessary to ensure equal power delivery to all customers no matter where they are located at the feeders, at the same time when keeping grid’s stability.

This paper is organized in the following structure. Firstly, the challenges and issues encountered in a low-voltage distribution grid network consisting of 67 households through a simulation of the Danish residential electricity network are analyzed using the power system analysis tool ‘DiGSILENT PowerFactory.’ The findings based on load flow analysis highlight critical concerns such as transformer and cable overloading, along with under-voltage issues, which stem from the increasing integration of EV chargers in households. Secondly, based on the driving and charging pattern and transformer loading data, an autonomous control approach of EVs using voltage droop is proposed to alleviate the load of distribution grid. Thirdly, the dynamic simulations demonstrated the effectiveness of energy management systems to address the challenges, particularly through the implementation of smart EV charging. Additionally, insights from real-world implementations in projects like SERENE and SUSTENANCE H2020 underscore the advantages of intelligent EV charging control systems. These projects highlight the potential of such systems to alleviate grid strain while enhancing overall energy efficiency.

2. Steady-State Simulation Analysis on Impact of EV Charging in Danish Residential Grids

2.1. Danish Residential Grid

In Denmark, most residences are connected to a three-phase 400 V power supply at 50 Hz, with a typical maximum current capacity of 32 A, which supplies around 22 kW of power distributed through underground cables. Denmark's residential grid aims to integrate decentralized power sources, including small local producers such as residential solar panels. With Denmark’s ambitious plans to reduce CO₂ emissions and increase renewable energy’s share, the residential heating and transportation sectors are evolving progressively. Many houseowners outside district heating areas are replacing oil boilers with biomass boilers or heat pumps in combination with thermal storage to support these goals [

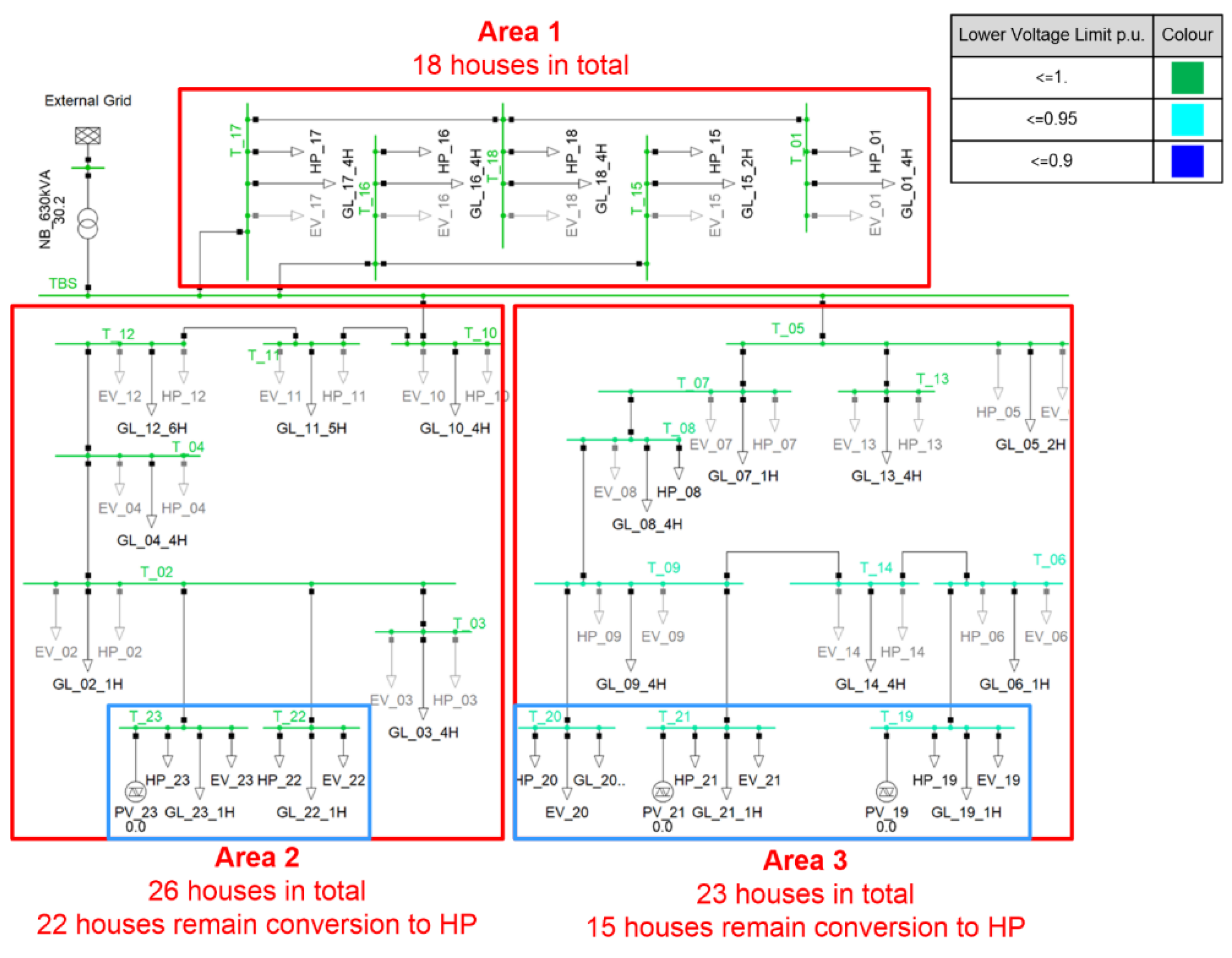

17]. At the same time, the rapid growth in EVs requires accommodation of home EV charging. One typical Danish residential area, where HP and EVs are being integrated to low voltage distribution network is presented in

Figure 1. A comprehensive electricity distribution network model for the LV distribution networks was developed using PowerFactory software to demonstrate the effects of various control methods for EV charging and assess possible impacts through dynamic simulation. The LV network is located in a municipality within the Midtjylland Region of Denmark.

In the network model shown in

Figure 1, the abbreviations denote electrical loads associated with electric vehicles (EV), heat pumps (HP), and general household loads (GL). A general load model is established to implement EVs and HPs easily. Several residences within the network are integrated as bulk loads. For example, a general household load group labelled "GL_12_6H" refers to a general load (GL) connected behind terminal "T_12," where "6H" indicates six houses. Similarly, EV and HP loads at terminal "T_12" are also represented as bulk loads. The EV and HP loads which are in the current distribution network scenario are shown in grey, which means they are not activated, because these customers have not installed EV chargers or convert heat systems.

The LV grid network presented in

Figure 1, was recently upgraded with installation of a new transformer (NB with 630 kVA supporting 67 households). Status of EV charger, HP and rooftop PV size of households other than those in the blue boxes are unknown. However, data from transformer loading profile include the effect of these loads in the electricity grid. The grid is divided into 3 areas. Area 1 includes 18 houses, all already equipped with electric heating systems. Areas 2 and 3 consist of 26 and 23 houses, respectively. Among these, five houses recently installed HP of varying capacities (ranging from 7 to 12 kW thermal capacity) and EV charging infrastructures of 11 kW each, as indicated within the blue boxes. A load flow analysis of the network during a peak winter conditions and five EVs charging (within the blue box) shows 30.2% transformer loading, with a minimum terminal voltage of 0.964 p.u. at terminal T_19. The color coding of the terminals represents voltage levels as specified in the top left corner, meaning that the houses in the blue boxes might experience a too low voltage according to the grid codes. In this network, there are still 22 and 15 houses in area 2 and 3 respectively, that is expected to convert heating system to HPs.

To phase out natural gas-based heating, the transition to HPs will necessitate additional power from the local electrical grid, thereby increasing the load on transformers. Consequently, a steady-state analysis is performed to assess the transformers' capacity to accommodate EV chargers. The rising energy demands from EVs and HPs have highlighted the need for grid upgrades, enhancement of demand response programs, and encouraging consumers to shift energy usage to periods of lower demand or high renewable generation. Easy use of smart energy management system and flexible energy tariffs enable residents to participate in these programs. While EVs are being integrated as consumers and potential storage units, the Danish grid currently does not support bidirectional power flow, where EV batteries can feed power back to the grid. However, vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology could be highly advantageous in a future distributed network [

18].

2.2. Steady-State Simulation Analysis on the Impact of EV Charging

The steady-state load flow analysis examines the existing distribution networks in Denmark with a recently upgraded 630 kVA transformer. On the above basic case, the study predicts the upcoming integration of HPs into the grid and their potential impact on transformer hosting capacity. With the addition of 37 HP units, each with an electrical power rating of 3 kW, the total load would increase by 111 kW, representing an 17.6% increase in the transformer's hosting capacity, which is 47.8% now. Hence, heat pumps (HPs), having smaller load capacities compared to an 11 kW EV charger, do not significantly challenge the transformer and cables loading. However, a potential issue arises if each house, following the HP upgrade, is also equipped with an 11 kW EV charging infrastructure. With the assumption that all EVs are charged simultaneously, it can be predicted that the total load would increase by 737 kW, which heavily overloads the transformer up to 147.2%. These findings highlight the significant effect of HP and EV integration on transformer capacity, emphasizing the need for smart grid management and potential upgrades to handle the rising demand, especially with the installation of EV chargers.

3. Dynamic Simulation Analysis on Impact of EV Charging

3.1. Driving Habit and Charging Requirement

The dynamic simulation is performed on the existing grid with EVs’ connection. To incorporate EVs into each household, the simulation scenarios are created based on statistical analysis of EV driving patterns and charging availability. Data from the Danish National Travel Survey (TU) covering 2006-2012, indicates that the daily travel distances of nearly 60% of cars range between 0-10 km, while around 18% range 10-20 km, and no more than 6% exceed 50 km [

19]. Thus, it can be concluded that daily charging is not necessary for all EVs. However, the real-world daily charging habits of EVs in residential areas is difficult to fully estimate, which emphasizes the importance of more practical data to improve the analysis.

Vehicles with smaller battery capacities, such as hybrids, typically charge at 3-7.4 kW, while EVs for longer distance usually require 11 kW chargers [

20]. This implies that not all homeowners require high-capacity chargers, though the growing preference for long-distance EVs over hybrids may drive the prevalence of higher-capacity chargers. Additionally, driving habits also vary according to the region and sample population, for example, the driving habits at the demonstration site may differ. The statistical data used in this study aims to reflect realistic EV charging behaviors rather than the assumption of the worst-case scenario. This approach is helpful to model typical charging demands and grid impacts while considering regional differences in driving and charging habits.

3.2. Transformer Loading Analysis

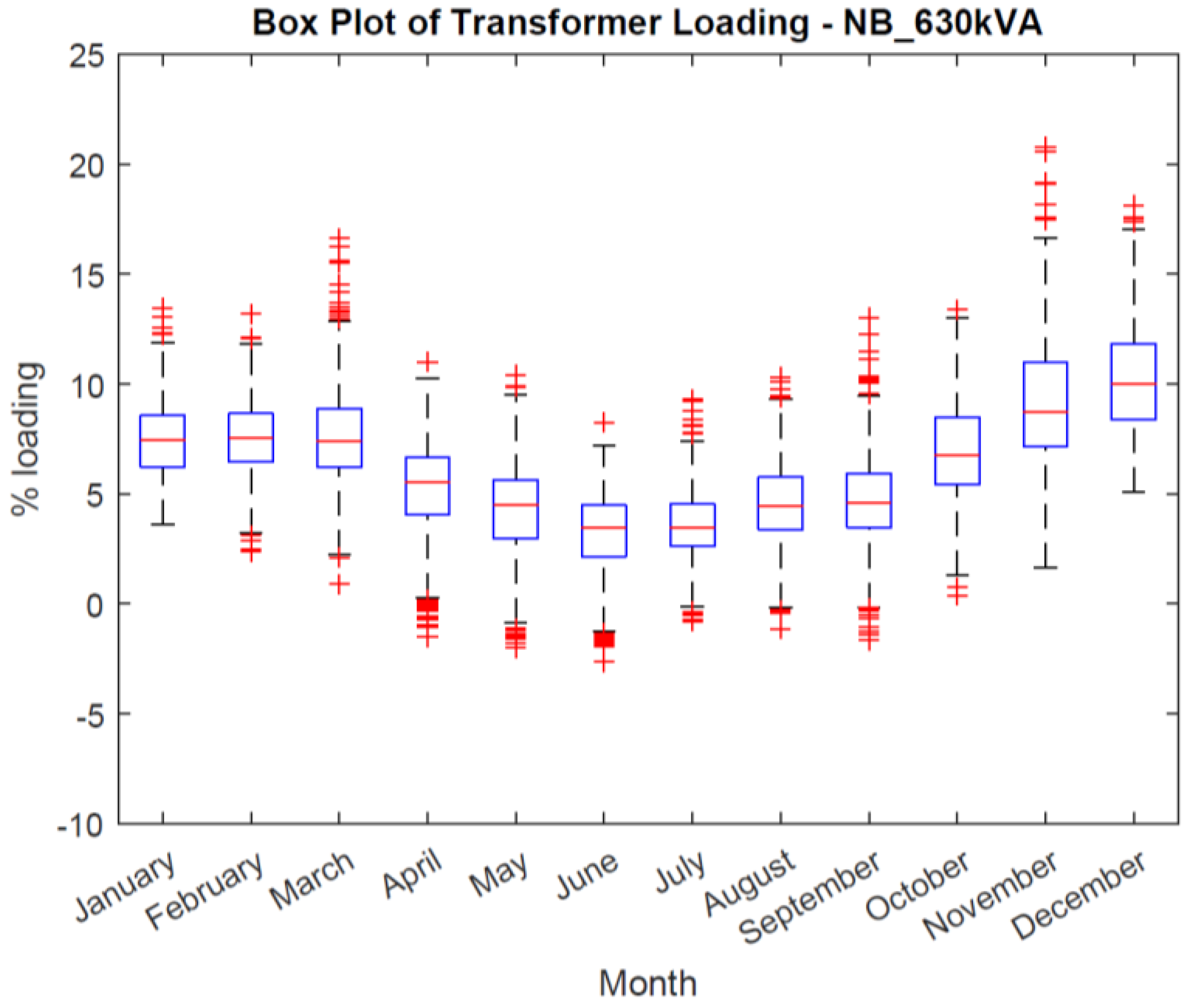

Based on the historical data, box plot of transformer loading for NB_630 kVA is presented in monthly basis using hourly data from 2023 in

Figure 2. The peak loading is occurring in winter.

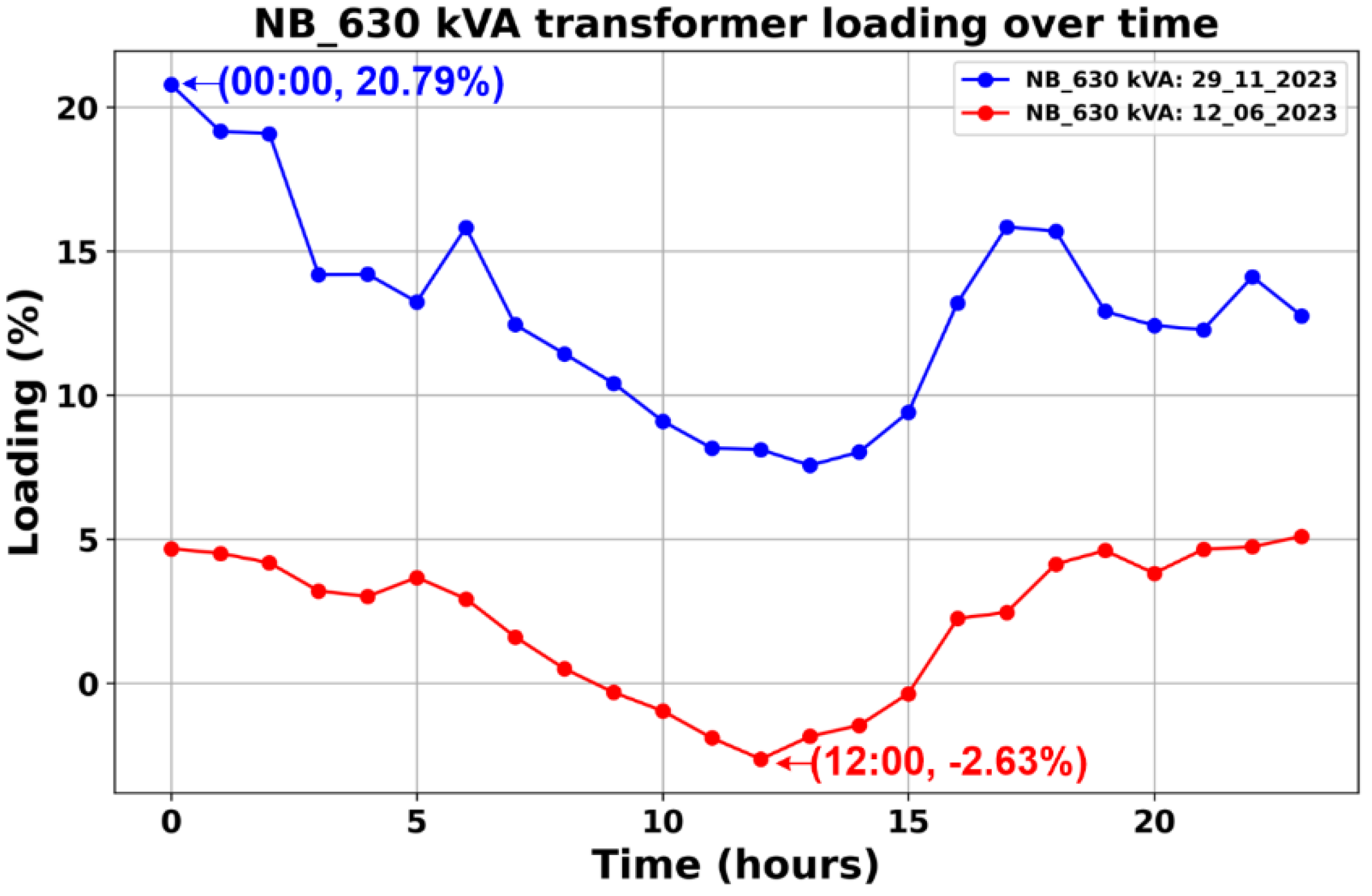

The minimum and maximum loading percentages along with the corresponding dates and times are marked in the

Figure 3. A negative minimum loading percentage indicates household PV production in the network is being sold back to the grid. For example, transformer NK_630 kVA recorded a minimum loading of -2.63%, representing 22.82 kW of rooftop PV generation sold to the grid in June. By comparison, it experienced peak loading of 20.79% at midnight, due to multiple existing EVs charging during low electricity prices. This data underscores the variability in transformer loading conditions across the observed period, influenced by factors such as PV generation, EV charging, electricity prices, and seasonal demand patterns.

3.3. EV Behaviours Modelling

The behavior of EV as an electrical load, when connected to the charging station, is modelled as a battery unit of a specific size. The depth of discharge (in %) of EV (

DOD) at the beginning of charging appropriately resembles the dynamics of driving profile and distance travelled. The initial state of charge (

SOCini) of an EV is related to its DOD by the equation,

After charging the EV for

t hours, its

SOC is determined using Coulomb count method as follows,

where

Cbat is the battery capacity in kWh and (

Pchar) is charging power in kW.

Pchar is proportional to the droop coefficient,

kt(

t), and it is given by,

3.4. Droop Control Approaches of EV Charging Based on Common Parameters

Since the actual daily charging patterns of EVs in residential areas remain unknown, an extreme scenario is analysed where all EVs are connected for charging simultaneously. This scenario represents the risk of numerous EVs charging at the same time, particularly during periods of low electricity prices, which could potentially overload the low-voltage distribution feeder.

To address this issue, two distinct control approaches are proposed and adopted in the project. One of them is Scheduling-Based Control approach. The EV charging scheme is controlled based on the transformer's hosting capacity. The number of EVs being charged simultaneously is limited to a critical number, which do not overload the local transformer or any cables to guarantee the grid operates more efficiently.

The other one is a Voltage-Based Droop Control approach, which is presented in paper [

21]. Reducing voltage deviations stemming from EV charging and thereby improving the voltage profile of distribution grids, is the main objective of the droop control approach considered. To address the issue of unfair distribution of EV charging power curtailment, a common parameter is adopted to estimate the droop-based power curtailment factor for all the customers in the local distribution grid.

The common parameters adopted can be the terminal voltage and transformer loading.

3.4.1. Droop Control Based on the Terminal Voltage

The voltage droop is based on the measurement of terminal voltage,

Vpoc(

t), at the point of connection of the EV charger. It is then compared with the specified high and low voltage levels,

Vh and

Vl, respectively. When

Vl <

Vpoc(

t)<

Vh, the voltage droop factor,

kv(

t) is given by,

The droop factor is unity when Vpoc(t)> Vh and it is zero when Vl > Vpoc(t). In this study the droop coefficient is calculated based on Eq. (4) considering Vh = 0.98 p.u. and Vl = 0.92 p.u. These high and low limits of the voltage for droop coefficient calculation is selected to maintain some room for drop of voltage to 0.9 p.u. due to other household loads. However, to ensure fair and equal power distribution along the feeder for the flexible operation of heat pumps and EVs, the droop coefficients can be adjusted dynamically along the distribution lines. This approach helps maintain voltage level limit and ensures equal power delivery to all customers flexible load operation, regardless of their location on the feeder. However, this requires regular updates of voltage measurements from different points along the feeder to a central server. The central server then recalculates the common droop coefficients for all flexible loads connected based on real-time data, enabling precise control of the power distribution system without violating the limit of transformer loading and terminal voltages.

3.4.2. Droop Control Based on the Transformer Loading

Similarly, the loading droop control is based on the measured value of transformer loading

Ixmer(

t). When the transformer loading exceeds the critical level (

icrit), i.e.

Ixmer(

t)>

icrit, the loading droop factor,

ki(

t) is given by,

Here, the critical level is arbitrarily selected to be 0.5 p.u.. The droop factor is filtered using a first order low pass filter to avoid rapid changes in the droop factor.

With droop control and high EV penetration in the local grid, there is a risk of unequal power curtailment among customers based on their point of connection within the distribution network. In contrast, with schedule-based control, only selected EVs are charged at a time with constant power. This selection process through scheduling and the limitation of charging power levels from droop control reduce users' ability to benefit from dynamic electricity pricing. These challenges highlight the need for an optimized charging management strategy to accommodate a large number of EVs while ensuring fairness and maintaining grid operating parameters within their limits.

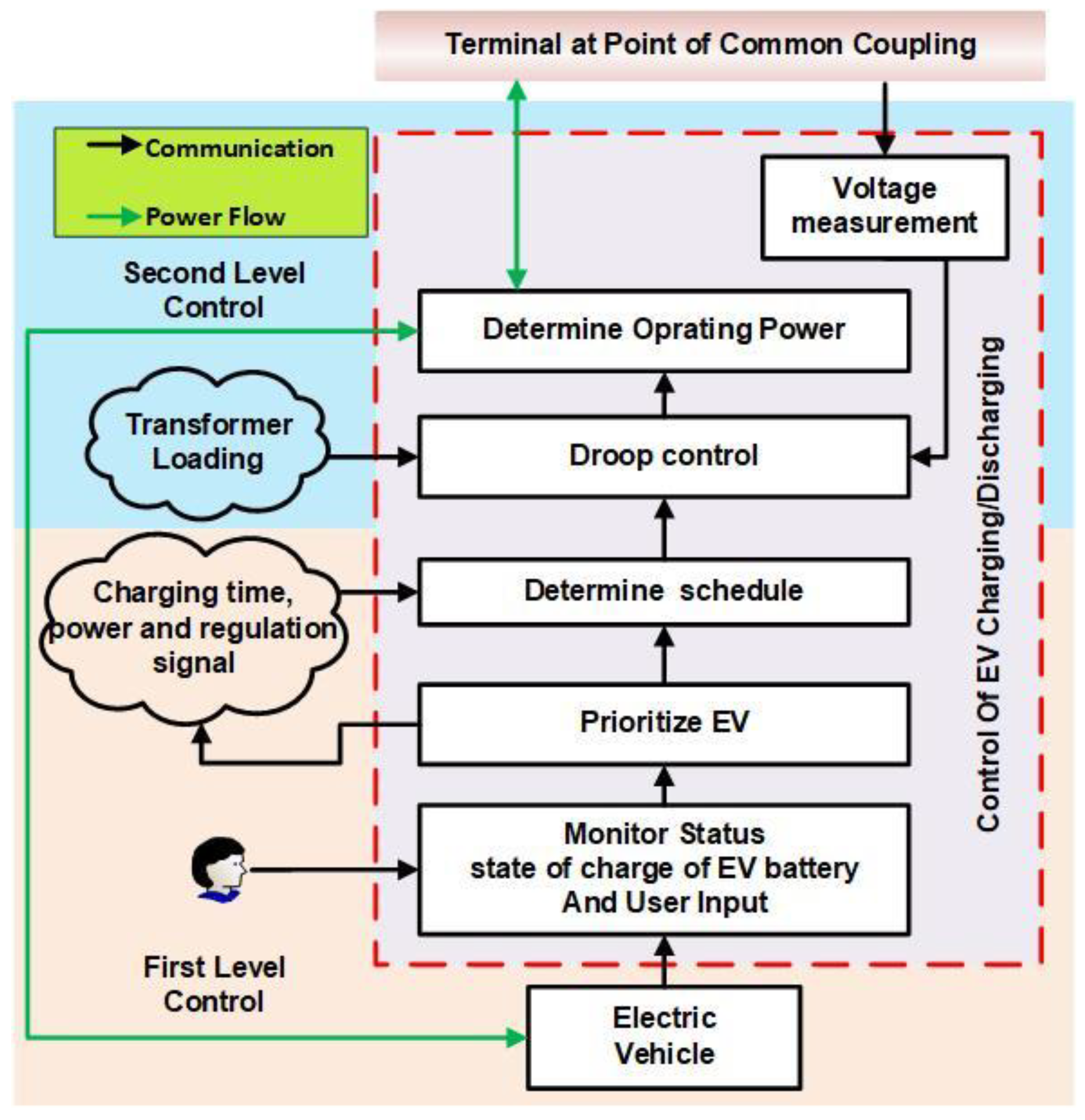

3.5. Control Coordination of EV Charging

Figure 4 illustrates a modular framework architecture for control and coordination in EV charging management, designed to support grid flexibility and participation in V2G during power regulation. When an EV connects for charging, the controller monitors the battery's status and accepts user inputs such as the estimated departure time, the minimum required charge level, and preferences for participating in grid flexibility services like voltage and frequency control or grid support. Using this user-provided information, the system prioritizes EV charging and creates a charging schedule, which is generated online via cloud computing or designated apps. The charging power is then adjusted based on this schedule or through droop control to maintain local voltage stability. Additionally, if the user opts to participate in grid support, the EV can release energy back to the grid in response to regulation signals, contributing to voltage and frequency control.

The control framework employs a two-level control approach, as outlined in [

22], to manage forecasting errors and communication failures during scheduled EV operations, ensuring users’ needs are met. The significant features of the Two-Level Control Approach are highlighted below.

First Level: scheduling and Coordination

This level creates an optimized charging schedule based on electricity pricing, EV availability for charging, PV power production, and user preferences for active participation in grid flexibility.

The schedule (time and charging power) is dynamically adjusted based on deviations from forecasts and the SOC of associated storage units.

Continuous communication with the central control server is required to send and receive control signals through a communication channel.

These control signals guide the second-level controller, which manages demand response for individual EV units.

Second Level: Local monitoring and control Signals

∙ This level manages the operation of EVs based on the battery's SOC and the supply voltage at the point of coupling between the EV charger and the electricity grid.

∙ It can override first-level control actions when necessary, ensuring safe operation, through set of control logic presented in this level.

∙ Local information (such as terminal voltage at POC, and SOC of EV battery) is measured and processed without requiring internet connectivity (i.e., using a wired connection).

∙ This control ensures SOC levels remain within critical limits, prevents violations of upper and lower energy thresholds, and supports local node voltage regulation where applicable.

As a result of the two-level control structure, computations can be executed at different levels to ensure privacy while also allowing for scalability through the decentralization of processes. Some tasks are handled locally at the second level control, while others are managed at a central through first level control. This approach improves system efficiency as it grows, enabling the control structure to manage a larger number of EVs or charging stations without overwhelming a single central system. Additionally, this approach allows for a careful selection of an appropriate models in terms of accuracy and computational requirements, considering both time and location in the electricity distribution feeder. The first-level controller leverages the benefits of the planning phase, utilizing day-ahead markets, while the second-level controller focuses on the operational phase to address local grid constraints (voltage and loading) and users’ needs (charging requirements and options for active participation in grid flexibility).

4. Grid Impact of Voltage Droop Control on Power Output

In addition to limiting the number of EVs charging simultaneously, controlling and reducing the charging power of EVs can enable the distribution grid to accommodate more EVs within safe loading limits. The droop control approach is thus considered effective demand response management (DRM) for reducing voltage deviations caused by EV charging, thereby improving the voltage profile of distribution grids [

23]. An example from the NB_630 kVA transformer network demonstrates the impact of droop control on the power output of EV chargers. This network consists of 62 residential households, and each is assumed to have one 11 kW EV charger

4.1. Charging Without Voltage Droop Control

Two scenarios of EV charging are evaluated in this condition to evaluate the distribution grid performance. The first scenario involves simultaneous charging from 00 to 10 hours, where all EVs charge at the same time. The second scenario involves a scattered charging pattern from 15 to 40 hours, where the EVs charge randomly based on their arrival. During this simulation any form of energy management for EV charging is not considered.

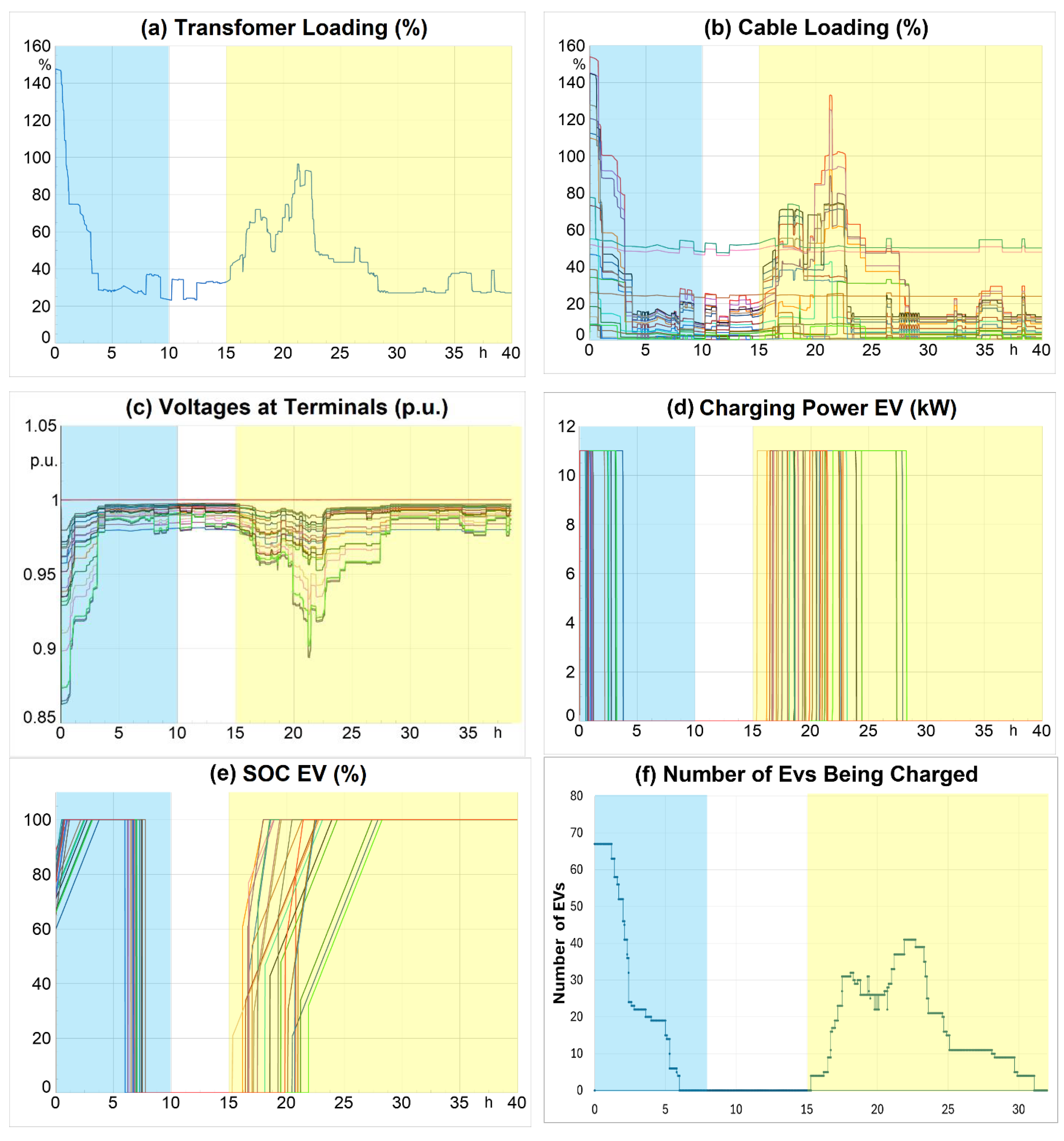

The results in

Figure 5 indicate that simultaneous EV charging leads to severe grid stress, with transformer loading peaking at 147.6%, overloading cables up to 150%, and causing terminal voltage to drop as low as 0.86 p.u. During the scattered charging period, while the transformer loading stays below 100%, some cables are briefly overloaded.

4.2. Charging with Voltage Droop Control

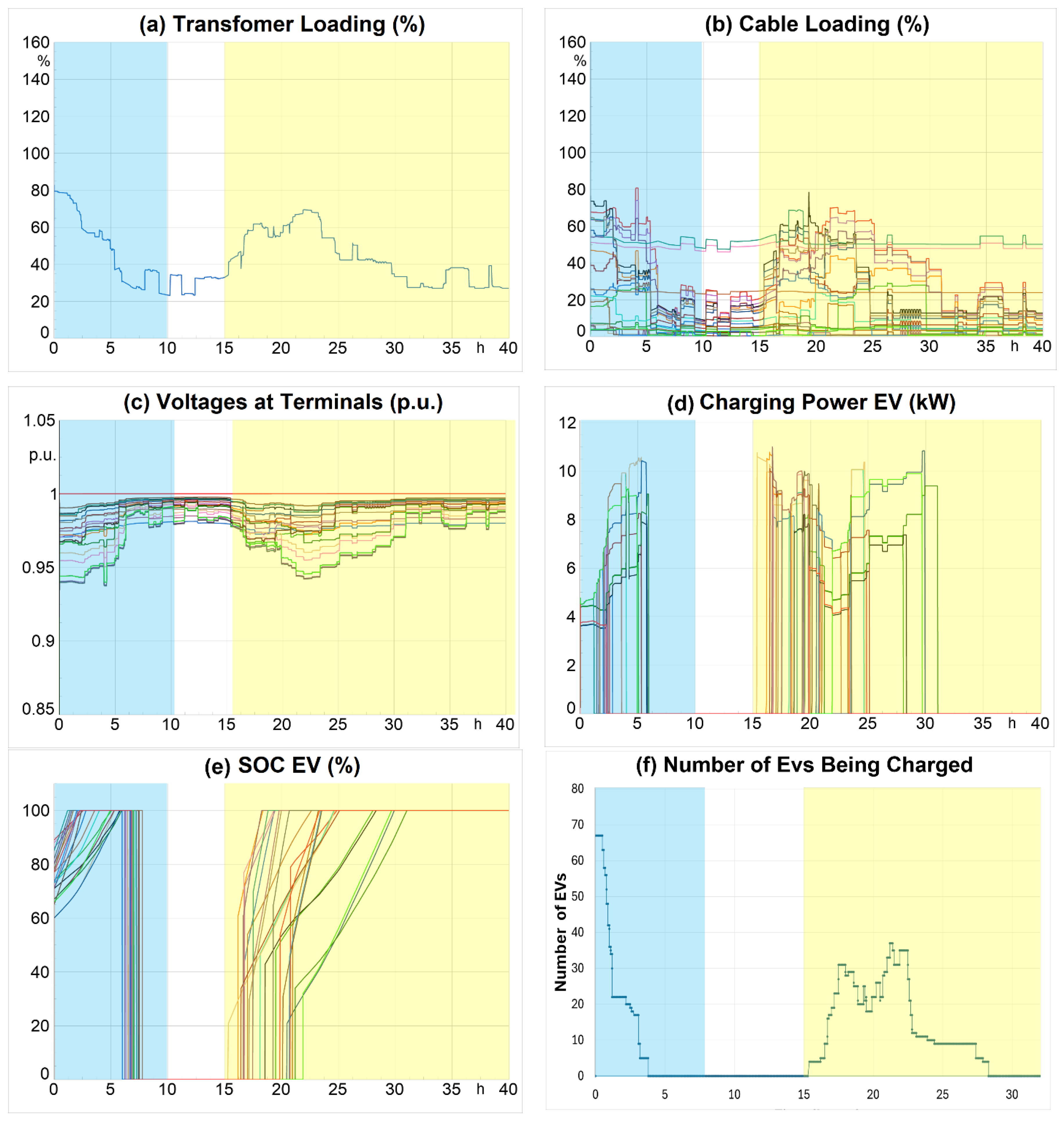

When droop control based EV charging is implemented, the EV charging power is dynamically adjusted based on the point-of-connection (POC) voltage of each EV charger (

Figure 6), instead of fixed rated power. This strategy eliminates overloading of both the transformer and cables, ensuring they operate within a pre-set limit of 80%. Transformer loading decreases by 67.6%, and maximum cable loading is reduced by 74%. Voltage drops are also mitigated, with the lowest terminal voltage improving to 0.93 p.u., well within the acceptable safety range of ±10%.

These results highlight the effectiveness of the droop control strategy in dynamically managing EV charging power to prevent grid overloading. Additionally, a droop control approach based on transformer loading can be implemented to ensure reliable and efficient grid operation by uniformly adjusting the charging power across all EVs based on same droop parameter [

21]. However, this approach may occasionally cause terminal voltage to drop below the operational limit of 0.9 p.u.

4.3. Discussion on the Effect of Droop Control

As EV adoption increases, charging demands introduce fluctuating loads that can strain grid infrastructure, affecting transformer capacity, voltage regulation, and cable loading. In these simulations, various algorithms are being developed to address these problems. The proposed solutions are not intended to depend on a specific price signal but rather on a type of contract established between the citizens and the DSO. Through this agreement, both schedule-based and droop control would be enabled, potentially relying on a capacity contract combined with a component tied to the actual kWh contributions from the households. Researchers, governments and operators are actually testing the scheduling approach, and it is not a technical problem to implement the approach according to the national regulations on market flexibility. However, it needs to be noted, there are no agreements yet on the approach based on droop control.

Results from dynamic control approaches in the NB_630 kVA transformer network shows that droop control dynamically curtails operating power to prevent grid stress and maintain stability, whereas price signal-based control optimizes self-consumption for EVs but risks grid strain during low-price periods. Future potential for droop control can be foreseen as EVs with variable power charging capabilities emerge.

Droop control effectively mitigates grid stress but may raise fairness concerns in energy distribution during low-price periods. Due to the voltage droop control, there is unequal curtailment of power among the consumers based upon their distance from the transformer substation. Coordinated scheduling proves beneficial in networks with limited hosting capacity and EVs with constant power charging. Smart charging strategies are essential to address the growing surge in EV adoption in Denmark.

5. Experience Sharing on Implementation of Intelligent EV Charging Control Systems and Its Benefits

From the above simulation results, it can be observed that smart control strategies are beneficially effective to deal with the overloading issues caused by surge of EV adoption in residential distribution power systems. However, putting scientific and technological achievements into practice is much more complicated and difficult compared with simulation modeling calculations on computers. Residences with EVs and a charging unit, as observed in the demonstration site in SERENE and SUSTANENCE projects, have wide ranges of EVs from different manufacturer and charging service providers [

24,

25]. Most of the EV models are controllable through application programming interface (API), enabling real-time monitoring and control. However, controlling and optimizing the charging of EVs within the local community grid has posed significant challenges due to limited direct control of the EV charging station available to local community operators [

26]. There are national incentives for EV owners, where the electricity tax is substantially reduced by nearly 1 DKK/kWh. However, the involvement of an EV charging operator is mandatory, to qualify for this tax reduction and they keep primary access to the charging data.

To address these limitations, NEOGRID (as a local community operator) has been exploring direct interfacing with EVs, instead of the charging station, for doing the scheduling according to self-consumption, electricity prices and the grid condition, achieving partial success with limited EV models. Ideally, the local community operator should fully monitor and control the EV charging for optimizing the grid impact. However, the charging operators’ control over chargers continues to affect reliable management of charging schedules.

It is recommended that EV charging operators enable input from energy community operators to optimize charging within local grids to avoid grid congestions and take self-consumption into account. However, this recommendation is complicated by Denmark's current landscape, where over 30 different charging operators exist, each offering varying levels of integration and control. To bridge this gap, there is a pressing need for a standardized interface that allows operators to manage individual EV charging within the community while respecting the priorities and preferences of EV owners. Such an approach would harmonize flexible grid operation with user autonomy, encouraging a more efficient and cooperative energy ecosystem.

Although EVs are being integrated as consumers and potential storage units, the Danish grid does not yet support bidirectional power flows, i.e. EV batteries can feed power back into the grids. However, V2G technology could be of great benefit in future distributed energy networks. This is proved by the Polish demo case in the SUSTENANCE project where charging stations with V2G charging technology were installed. The main challenge shows that there are no legal regulations or manuals that would be specific for installing and using V2G chargers. Generally, the V2G technology is not yet widely accessible, so the specific aspects of connecting such chargers to the grid and their billing were not yet fully established and resolved. The situation probably will change when the V2G technology is implemented within the regulations regarding flexibility services.

6. Conclusions

The growing adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) among Danish households, driven by public policies, environmental consciousness, and advancements in EV technology, represents a major step toward sustainable transportation. However, this rapid growth poses significant challenges for the low-voltage distribution grid, particularly in terms of hosting capacity, grid congestion, and under-voltage issues. These challenges can be partially mitigated through the smart control of EVs.

Therefore, this paper examines the challenges faced by the low voltage distribution grid through a simulation study of the Danish residential electricity network. It is predicted via load flow analysis that low-carbon technologies such as heat pumps and EVs in fact increases the risk of overloading the residential power grid. To cope with the challenge, a droop control based EV charging coordination approach is adopted. Simulation results indicate that droop control effectively adjusts operating power in real time to alleviate grid burden and maintain stability. In contrast, price signal-based control enhances self-consumption for EVs but may lead to grid strain during periods of low electricity prices. The potential of droop control is expected to grow as EVs with variable power charging capabilities become more prevalent.

The insights from demonstration H2020 projects like SERENE and SUSTENANCE underscore the importance of integrating smart charging solutions and fostering collaboration between EV charging operators and energy community operators to maintain a resilient and efficient grid that meets the evolving demands of sustainable mobility. Various smart control strategies can be implemented to support demand response and optimization. Moreover, actively involving consumers in grid operations through energy management systems is essential to reducing the strain on the distribution grid. Besides, although there are some limitations, vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology could be highly beneficial in a distributed energy network in the future.

Acknowledgements

This research has received funding from EU Horizon projects - SUSTENANCE under grant agreement no. 101022587 and SERENE under grant agreement no.957682. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

References

- The Motor Vehicle Agency (Motorstyrelsen). "Registration tax and rates." https://motorst.dk/en-us/individuals/vehicle-taxes/registration-tax/registration-tax-and-rates (accessed 24, 09, 2024).

- Danmarks Statistik. "New registrations and used cars." https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/emner/transport/transportmidler/nyregistrerede-og-brugte-biler (accessed 12, 09, 2024).

- G. Viganò et al., "Energy transition through PVs, EVs, and HPs: A case study to assess the impact on the Brescia distribution network," in 2021 AEIT International Annual Conference (AEIT), 2021: IEEE, pp. 1-6.

- Kotsonias, L. Hadjidemetriou, E. Kyriakides, and Y. Ioannou, "Operation of a low voltage distribution grid in Cyprus and the impact of photovoltaics and electric vehicles," in 2019 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT-Europe), 2019: IEEE, pp. 1-5.

- R. O. Oliyide and L. M. Cipcigan, "The impacts of electric vehicles and heat pumps load profiles on low voltage distribution networks in Great Britain by 2050," International Multidisciplinary Research Journal, vol. 11, pp. 30-45, 2021.

- J. van der Burgt, S. P. Vera, B. Wille-Haussmann, A. N. Andersen, and L. H. Tambjerg, "Grid impact of charging electric vehicles; study cases in Denmark, Germany and The Netherlands," in 2015 IEEE Eindhoven PowerTech, 2015: IEEE, pp. 1-6.

- T. Procopiou, J. Quirós-Tortós, and L. F. Ochoa, "HPC-based probabilistic analysis of LV networks with EVs: Impacts and control," IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 1479-1487, 2016.

- W. Kong, K. Ma, and F. Li, "Probabilistic impact assessment of phase power imbalance in the LV networks with increasing penetrations of low carbon technologies," Electric Power Systems Research, vol. 202, p. 107607, 2022.

- E. Sortomme, M. M. Hindi, S. J. MacPherson, and S. Venkata, "Coordinated charging of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles to minimize distribution system losses," IEEE transactions on smart grid, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 198-205, 2010.

- Srivastava, M. Manas, and R. K. Dubey, "Electric vehicle integration’s impacts on power quality in distribution network and associated mitigation measures: a review," Journal of Engineering and Applied Science, vol. 70, no. 1, p. 32, 2023.

- N. Brinkel, W. Schram, T. AlSkaif, I. Lampropoulos, and W. Van Sark, "Should we reinforce the grid? Cost and emission optimization of electric vehicle charging under different transformer limits," Applied Energy, vol. 276, p. 115285, 2020.

- Al Zishan, M. M. Haji, and O. Ardakanian, "Adaptive congestion control for electric vehicle charging in the smart grid," IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 2439-2449, 2021.

- H. Ramadan, A. Ali, M. Nour, and C. Farkas, "Smart charging and discharging of plug-in electric vehicles for peak shaving and valley filling of the grid power," in 2018 Twentieth International Middle East Power Systems Conference (MEPCON), 2018: IEEE, pp. 735-739.

- M. Secchi, G. Barchi, D. Macii, and D. Petri, "Smart electric vehicles charging with centralised vehicle-to-grid capability for net-load variance minimisation under increasing EV and PV penetration levels," Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks, vol. 35, p. 101120, 2023.

- S. Weckx and J. Driesen, "Load balancing with EV chargers and PV inverters in unbalanced distribution grids," IEEE transactions on Sustainable Energy, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 635-643, 2015.

- S. V. Saleh and M. A. Latify, "Coordinated Unbalance Compensation and Harmonic Mitigation in the Secondary Distribution Network Through EVs Participation," IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 2024.

- Danish Energy Agency (Energistyrelsen). "Information about the heating area." https://ens.dk/forsyning-og-forbrug/information-om-varme (accessed 12, 11, 2024).

- N. O. Nagel, E. O. Jåstad, and T. Martinsen, "The grid benefits of vehicle-to-grid in Norway and Denmark: An analysis of home- and public parking potentials," Energy, vol. 293, p. 130729, 2024/04/15/ 2024.

- R. Sinha, E. R. Moldes, A. Zaidi, P. Mahat, J. R. Pillai, and P. Hansen, "An electric vehicle charging management and its impact on losses," in IEEE PES ISGT Europe, 2013: IEEE, pp. 1-5.

- J. Dixon and K. Bell, "Electric vehicles: Battery capacity, charger power, access to charging and the impacts on distribution networks," eTransportation, vol. 4, p. 100059, 2020/05/01/ 2020.

- R. Sinha, H. Golmohamadi, S. K. Chaudhary, and B. Bak-Jensen, "Electric Vehicle Charging Management with Droop Control," in 2024 IEEE International Conference on Power System Technology (PowerCon), 2024: IEEE, pp. 1-5.

- R. Sinha, S. K. Chaudhary, B. Bak-Jensen, and H. Golmohamadi, "Smart Operation Control of Power and Heat Demands in Active Distribution Grids Leveraging Energy Flexibility," Energies, vol. 17, no. 12, p. 2986, 2024.

- M. A. S. T. Ireshika, R. Lliuyacc-Blas, and P. Kepplinger, "Voltage-based droop control of electric vehicles in distribution grids under different charging power levels," Energies, vol. 14, no. 13, p. 3905, 2021.

- "Sustainable and Integrated Energy Systems in Local Communities-SERENE." https://h2020serene.eu/ (accessed 11, 02, 2025).

- "Sustainable energy system for achieving novel carbon neutral energy communities-H2020 SUSTENANCE." https://h2020sustenance.eu/ (accessed 10, 02, 2025).

- G. E. Coria, F. Penizzotto, and A. Romero, "Probabilistic analysis of impacts on distribution networks due to the connection of diverse models of plug-in electric vehicles," IEEE Latin America Transactions, vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 2063-2072, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).