Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The proposed framework utilizes mean field approximations to capture the aggregate behavior of surrounding vehicles, providing a more accurate and computationally efficient representation of interactive driving scenarios.

- By integrating these mean field predictions into a receding-horizon MPC-QP framework, our framework effectively handles the nonlinear dynamics of vehicles while ensuring real-time computation of optimal control actions.

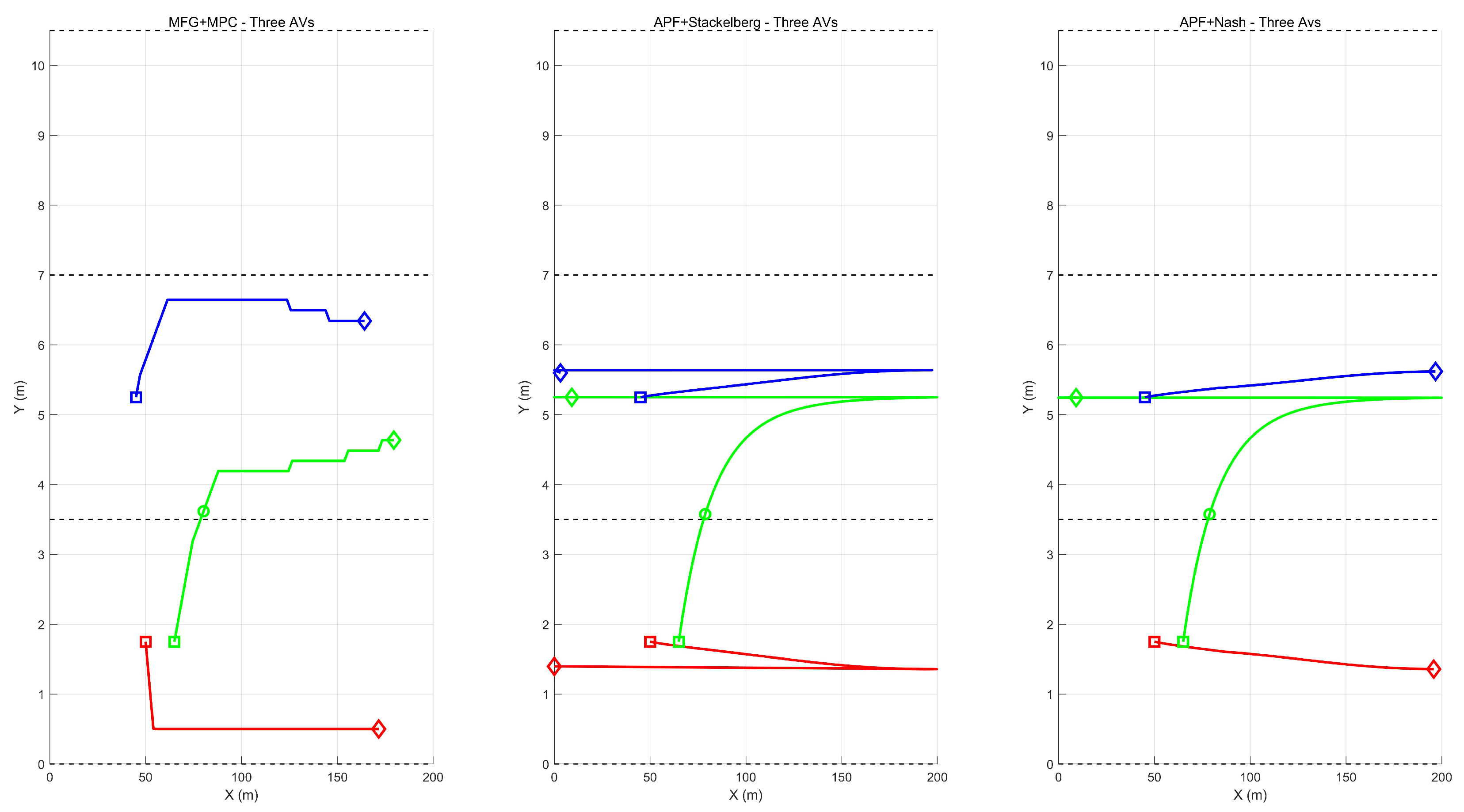

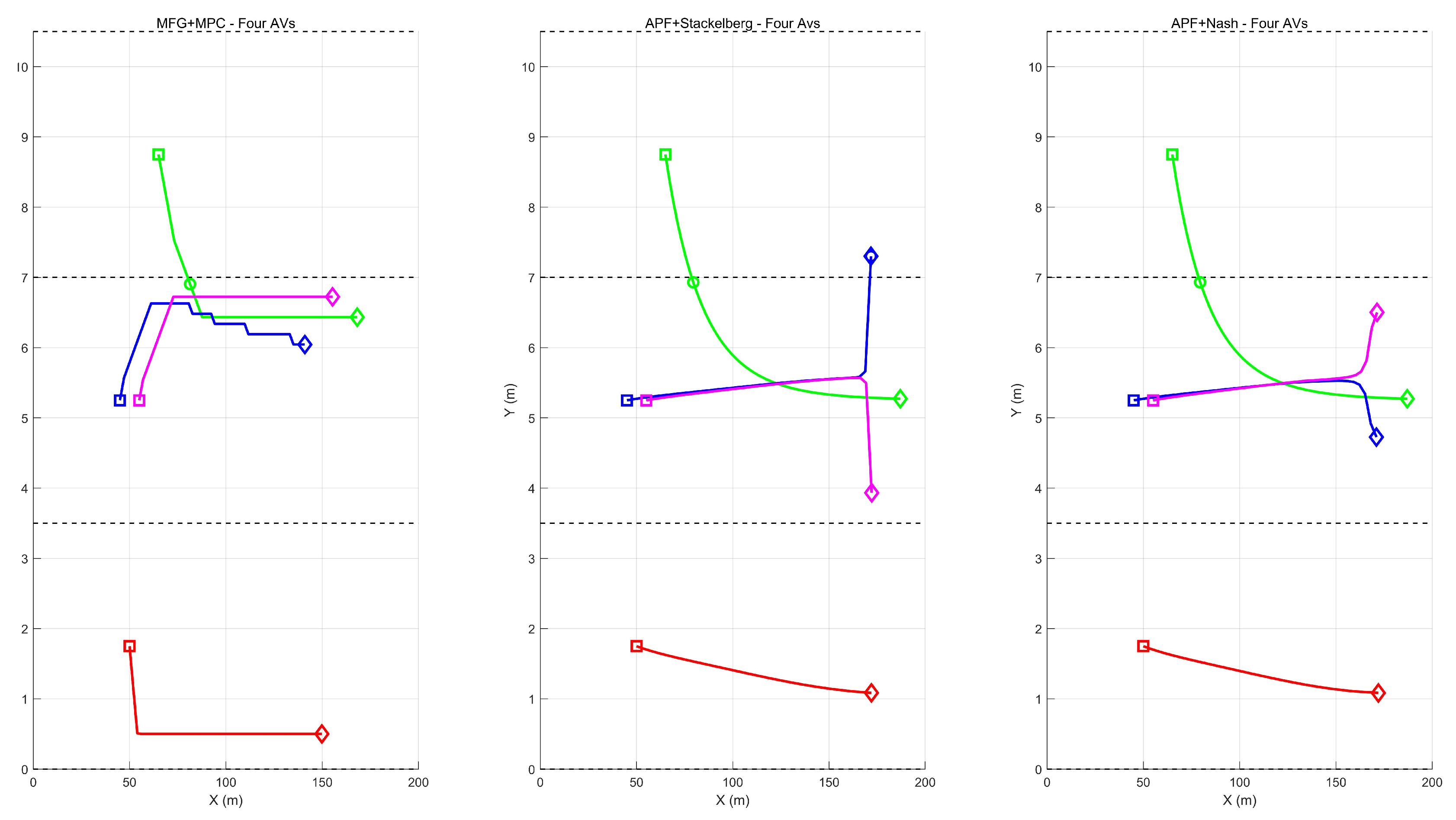

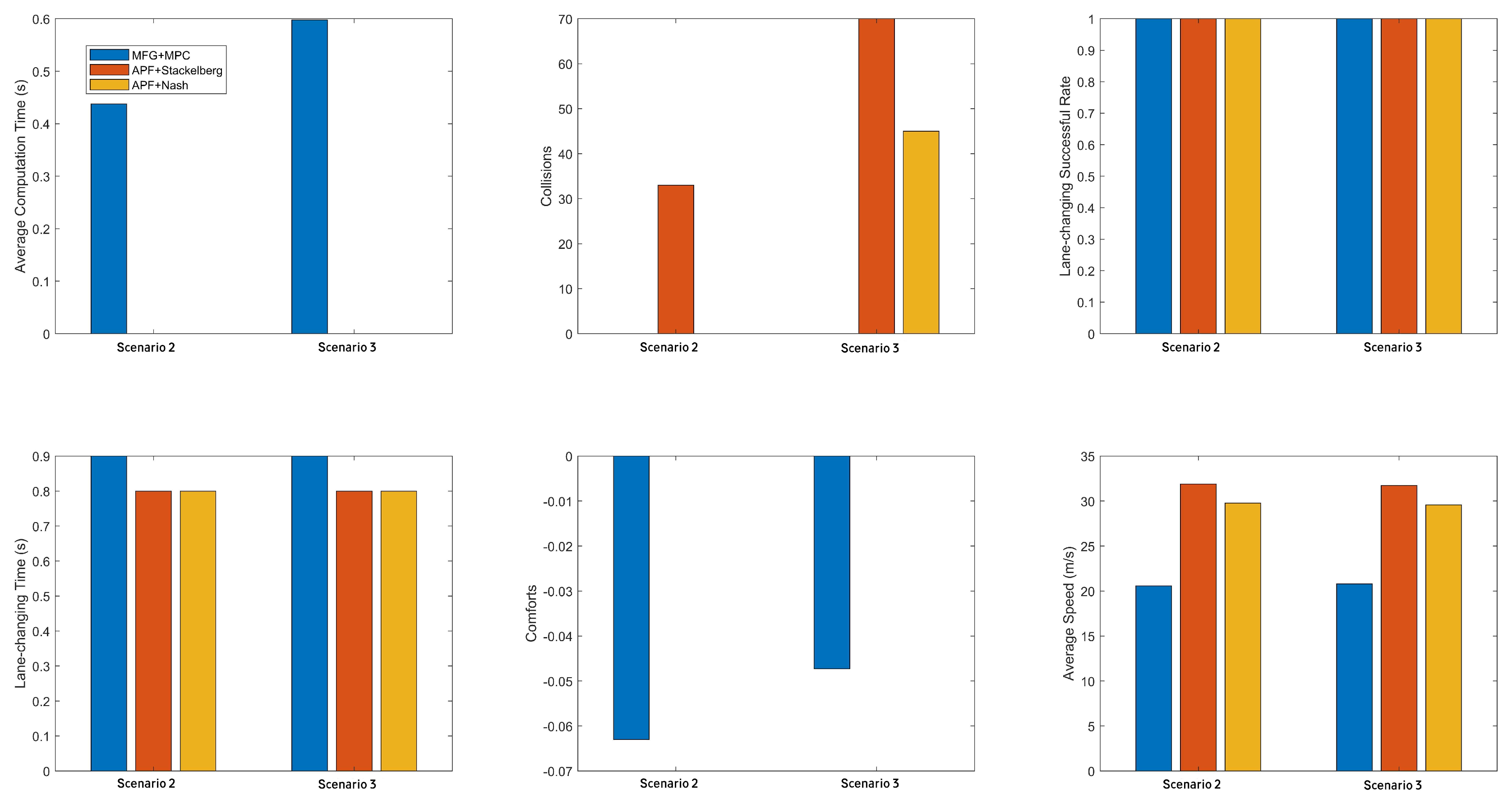

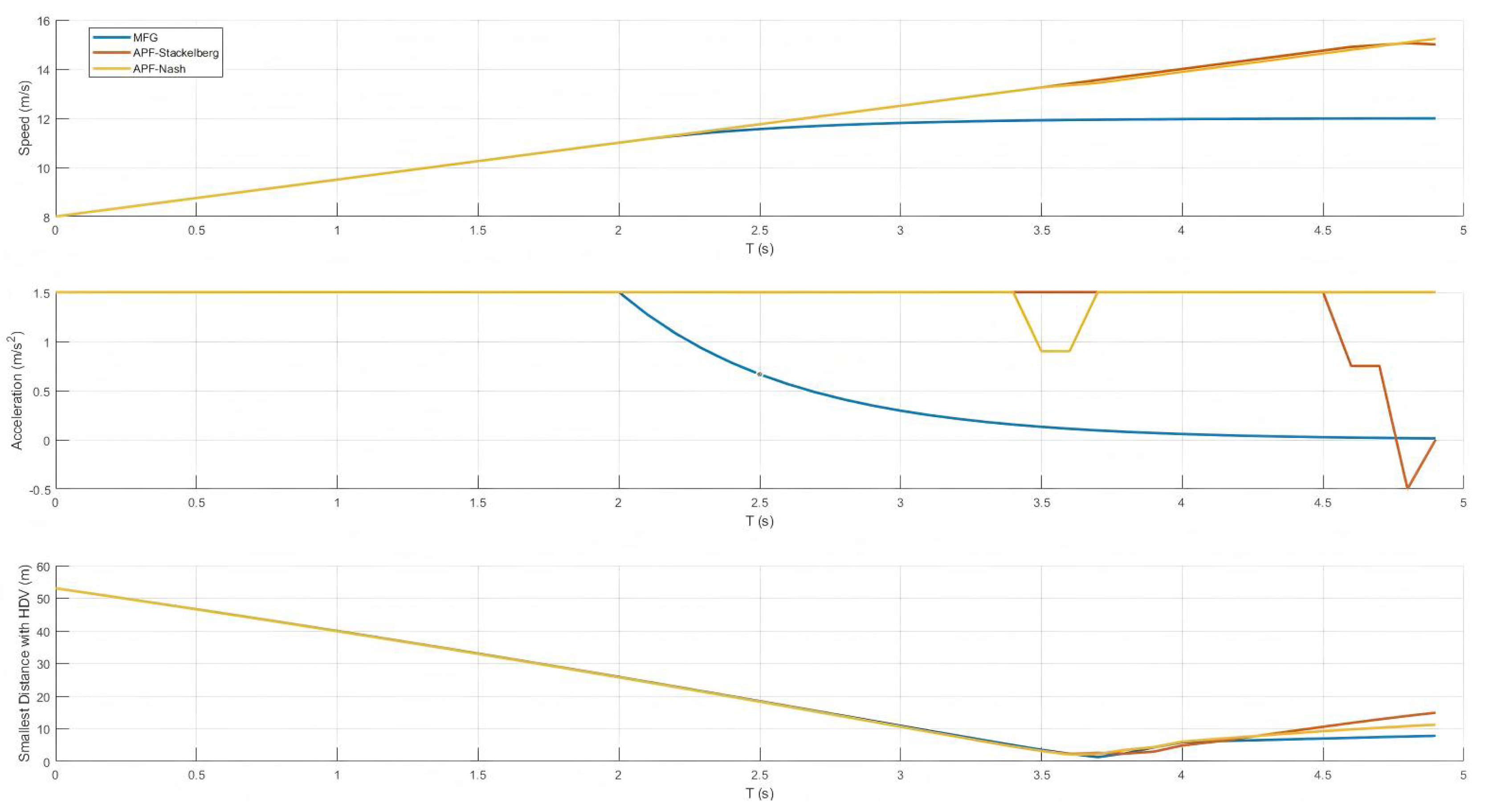

- Extensive simulation results demonstrate that our framework not only guarantees collision-free operation but also produces smoother trajectories and enhanced overall traffic performance compared to existing game-based approaches.

2. Related Works

2.1. Challenges in Interactive Decision-Making

2.2. Shortcomings of Current Game-Based Approaches

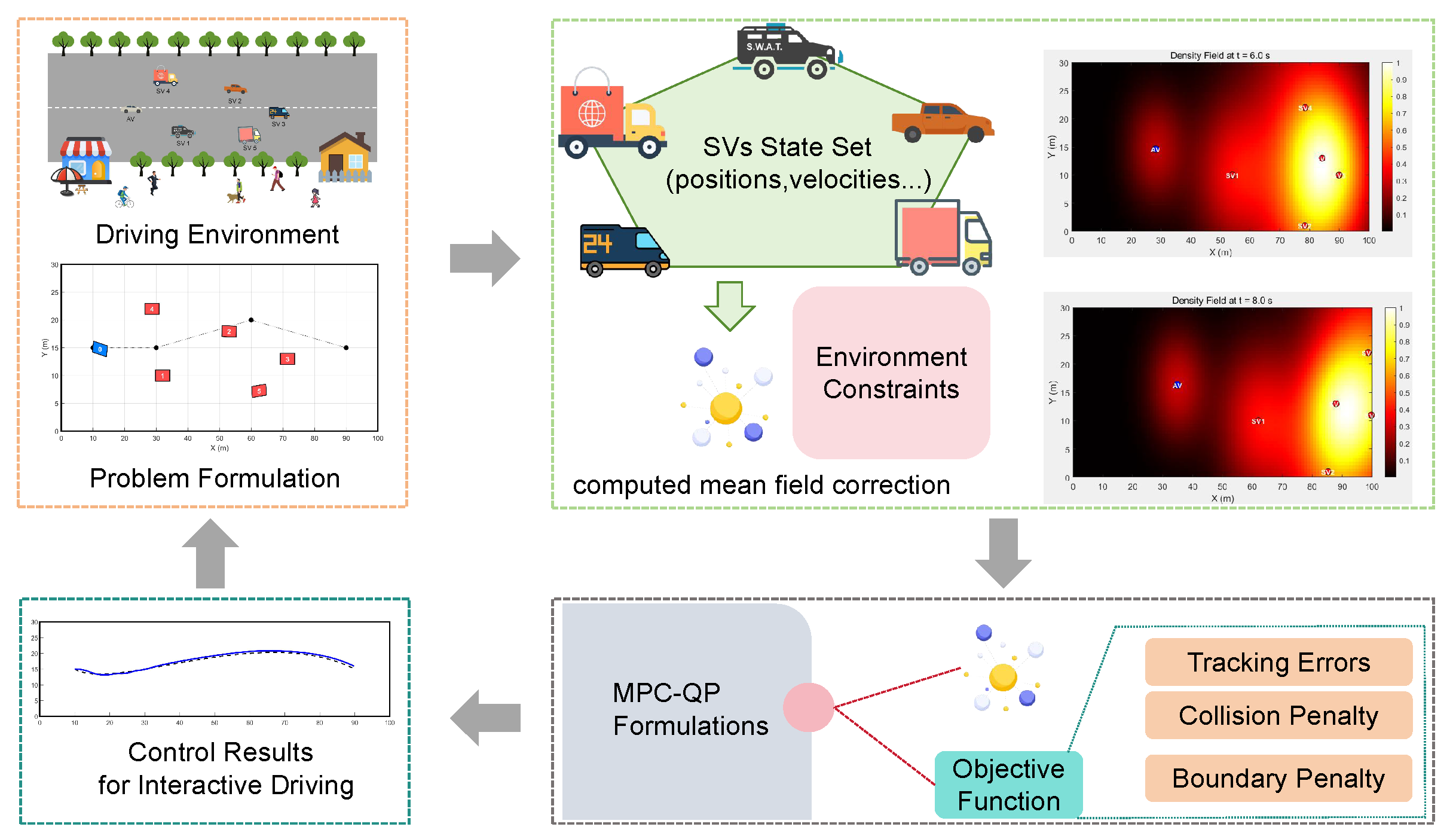

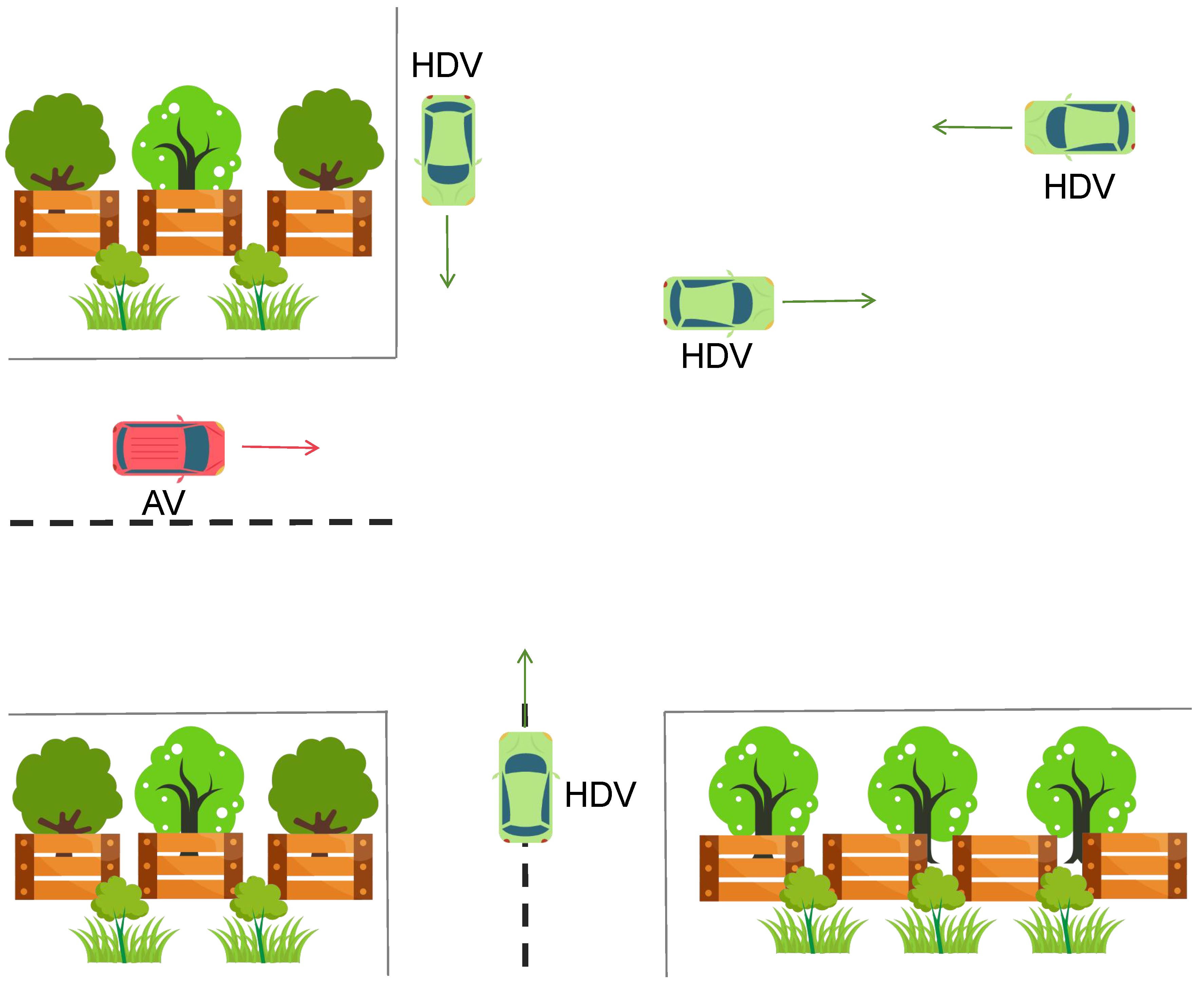

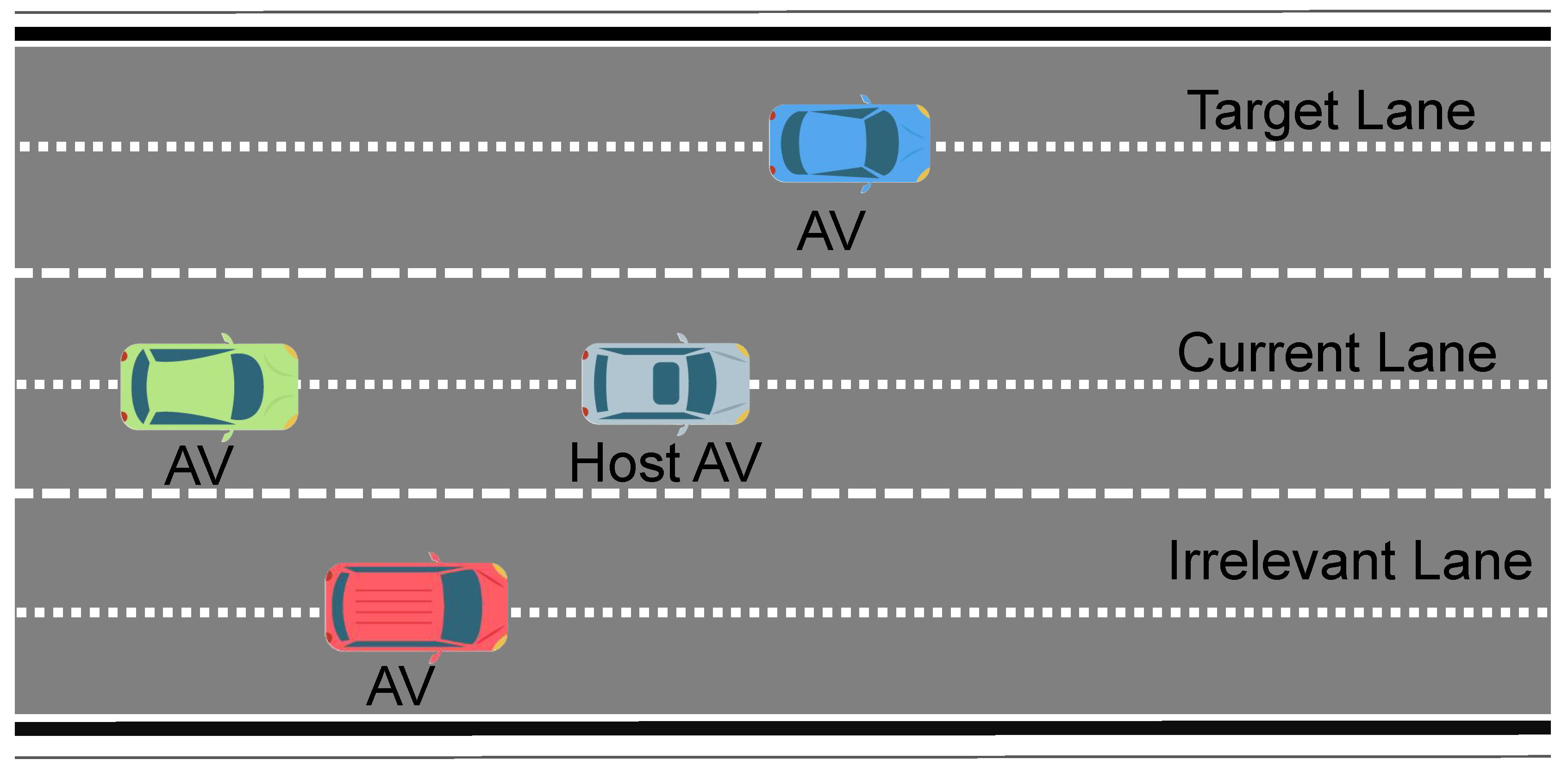

3. System Overview

4. Methodology

4.1. Interactive Prediction via MFG

4.2. MPC-QP Formulation with Environmental and Safety Constraints

|

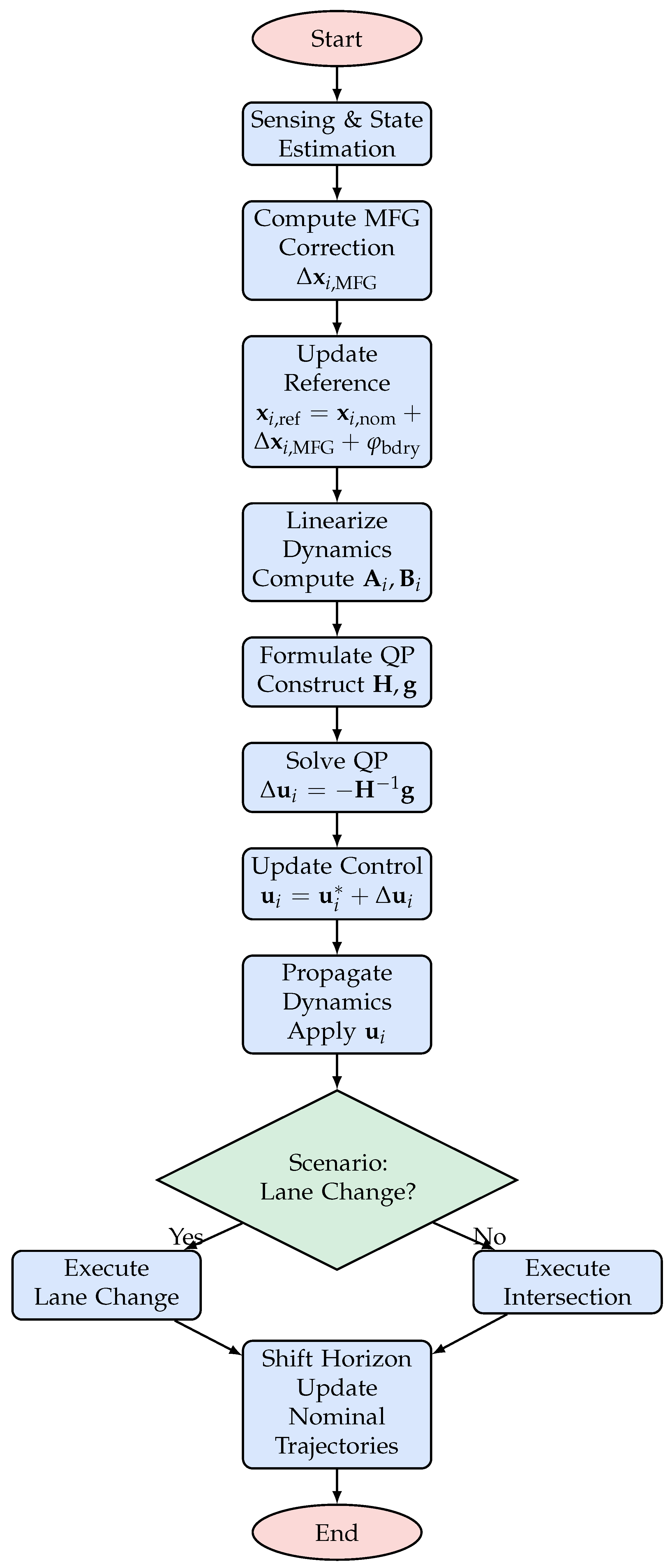

Algorithm 1: Extended MFG Integrated MPC-QP Algorithm with Environmental and Safety Constraints

|

|

- Start: This is the initialization step where the system loads all sensor data, initial vehicle states, and environmental parameters. The controller is set up to begin the receding-horizon control loop.

- Sensing & State Estimation: In this step, all vehicles (both the AV and HDVs) gather sensor data (e.g., from LiDAR, cameras, radar) to estimate their current states (position, velocity, heading). Accurate state estimation is critical for reliable prediction and control.

- Compute MFG Correction: The MFG module processes the states of all vehicles (except the one under consideration) to compute an aggregate correction term, . This term approximates the collective influence of surrounding vehicles, reducing the complexity of pairwise interaction modeling. It is then used to update the nominal reference state, so that the adjusted reference becomesthereby ensuring that the control policy dynamically incorporates real-time interactive effects.

- Update Reference: The nominal reference state is updated by incorporating the MFG correction along with a boundary penalty that accounts for the proximity to the environment boundaries. This yields the new reference state:

- Linearize Dynamics: The vehicle’s nonlinear dynamics (given by the bicycle model) are linearized around the nominal trajectory . The Jacobian matrices and capture the sensitivity of the state with respect to state and control inputs, respectively.

- Formulate QP Matrices: Using the linearized model, the Hessian matrix and gradient vector for the QP are constructed. Specifically, is computed by accumulating the termsand the gradient is given bywhere is the terminal cost weight matrix. These matrices encapsulate the tracking errors, control efforts, and indirectly include collision penalties from .

-

Solve QP: The quadratic programming problem is solved to obtain the optimal control correction:This step yields the necessary adjustment to the nominal control inputs to reduce the overall cost.

-

Update Control: The control input is updated by adding the correction term to the nominal control:This new control command is what is applied to the vehicle.

- Propagate Dynamics: The updated control inputs are applied to the nonlinear dynamics model to propagate the vehicle states forward. Additionally, environmental constraints are enforced to ensure that all vehicle states remain within the designated region .

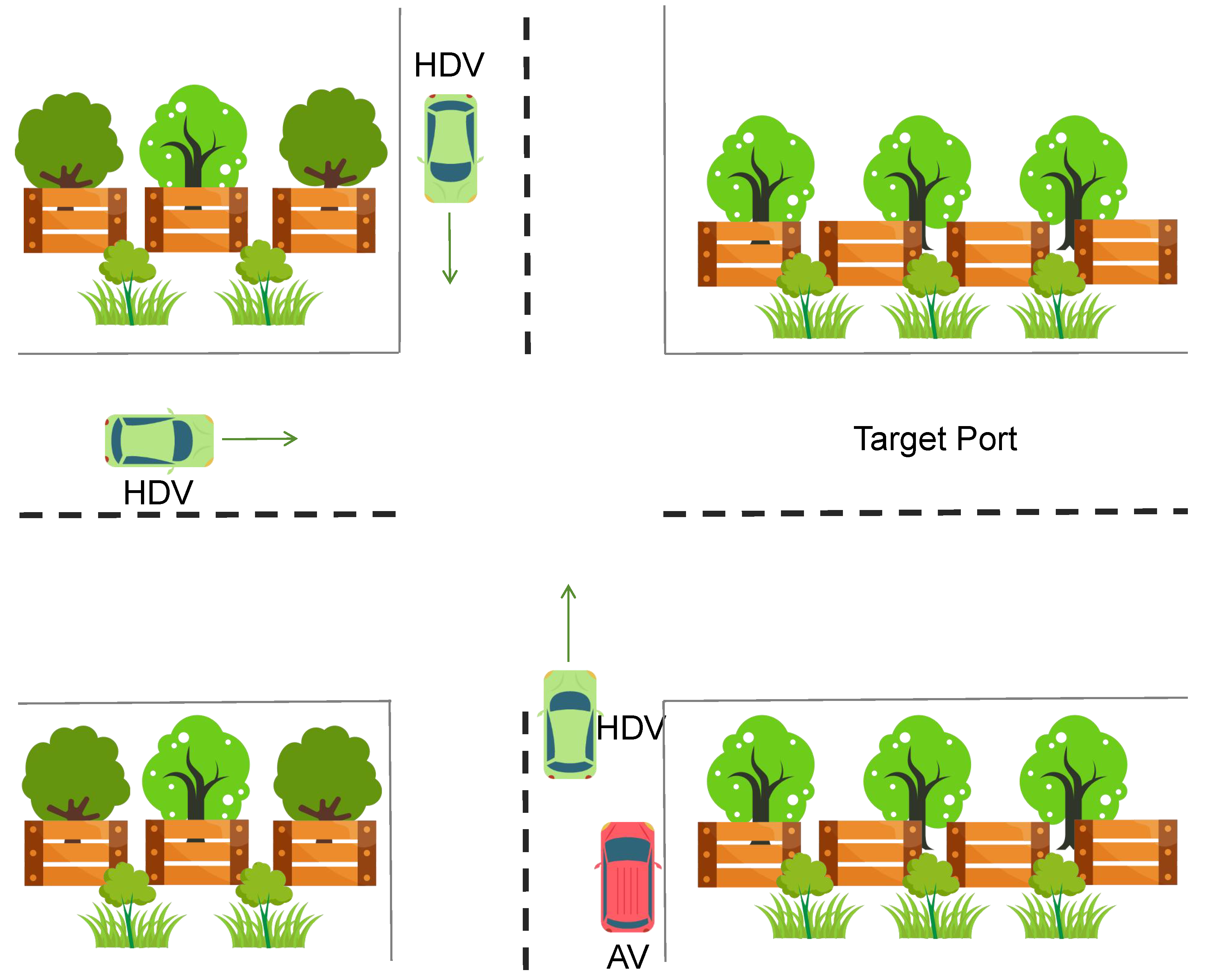

- Scenario Decision: A decision node determines the driving scenario (e.g., lane change or intersection negotiation) based on the current state and predicted vehicle interactions. This decision may trigger additional scenario-specific maneuvers.

- Execute Maneuver: Depending on the scenario decision, the system executes the corresponding maneuver—either a lane change or an intersection negotiation—adjusting the control inputs as necessary.

- Shift Horizon: After control actions are applied and states are updated, the prediction horizon is shifted forward. The nominal trajectories are updated, and the process repeats in a receding-horizon fashion.

- End: The control loop terminates when the driving task is complete or when the specified time horizon is reached.

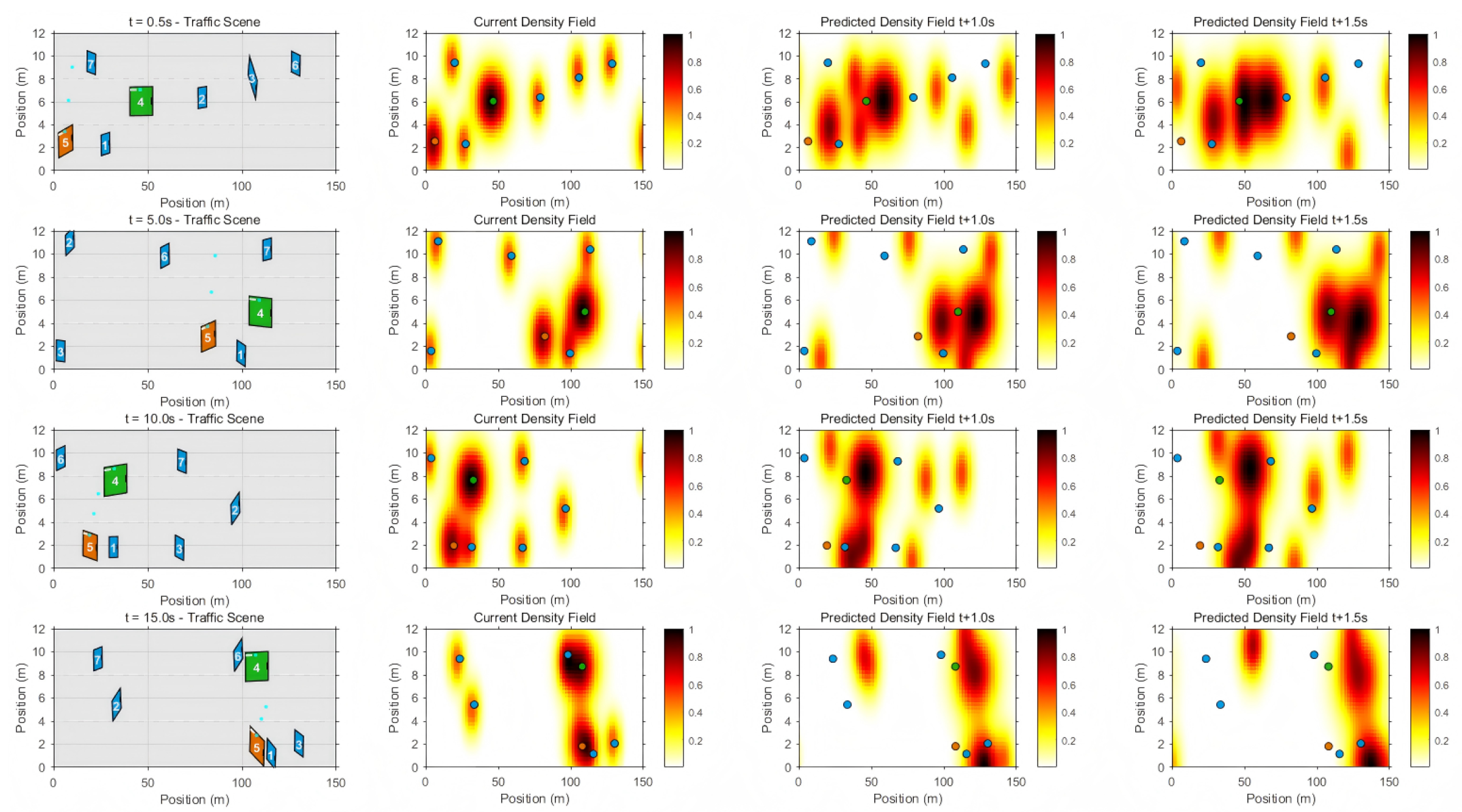

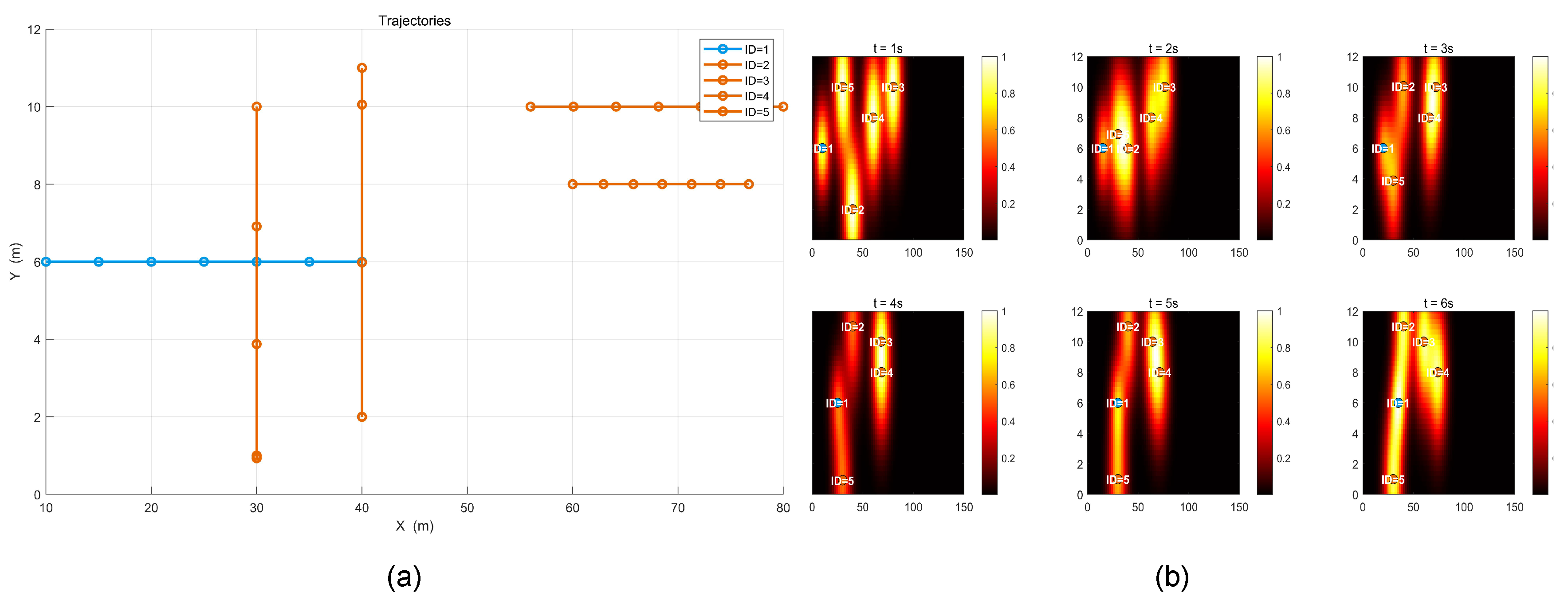

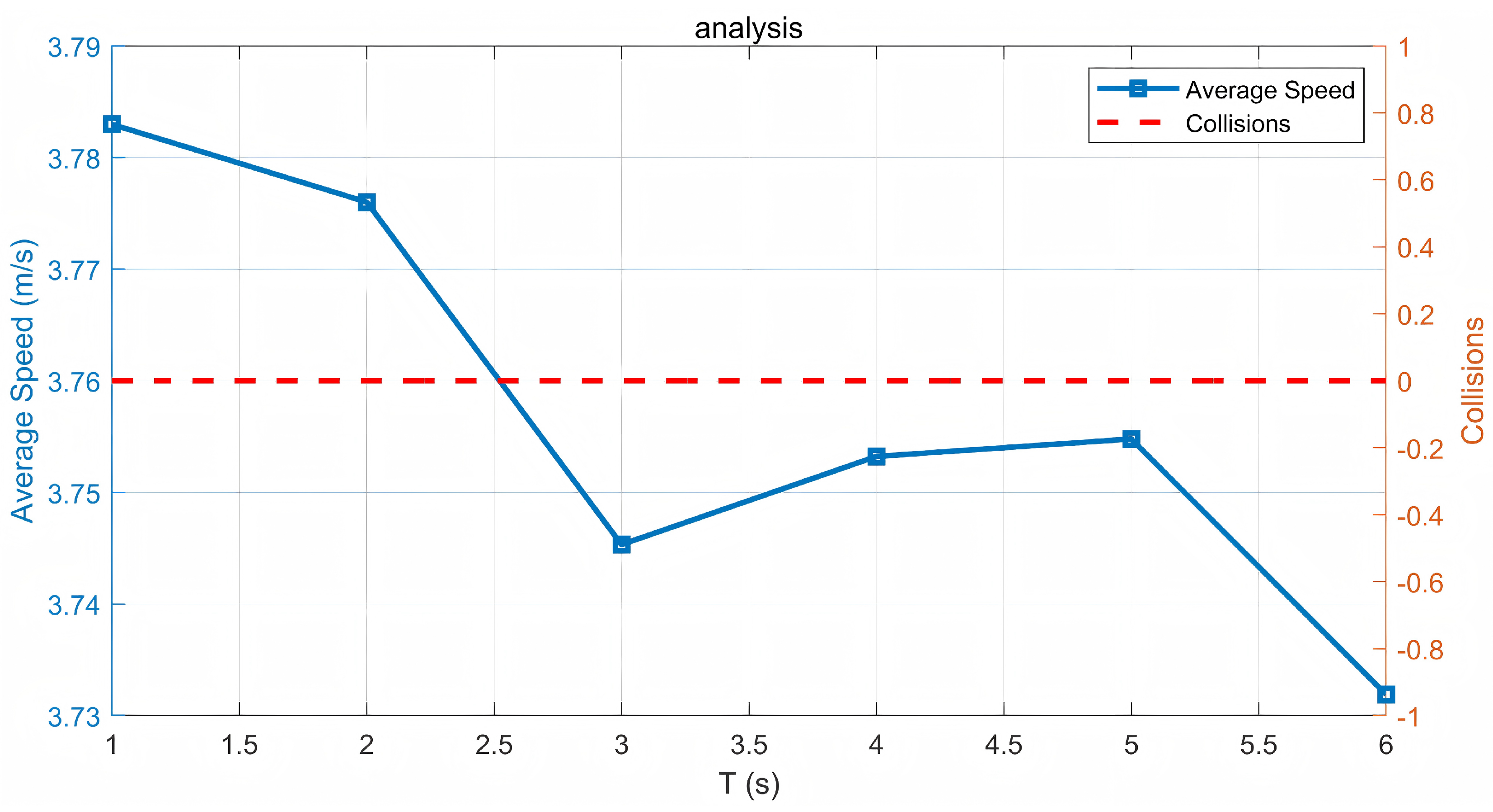

5. Experimental Evaluation

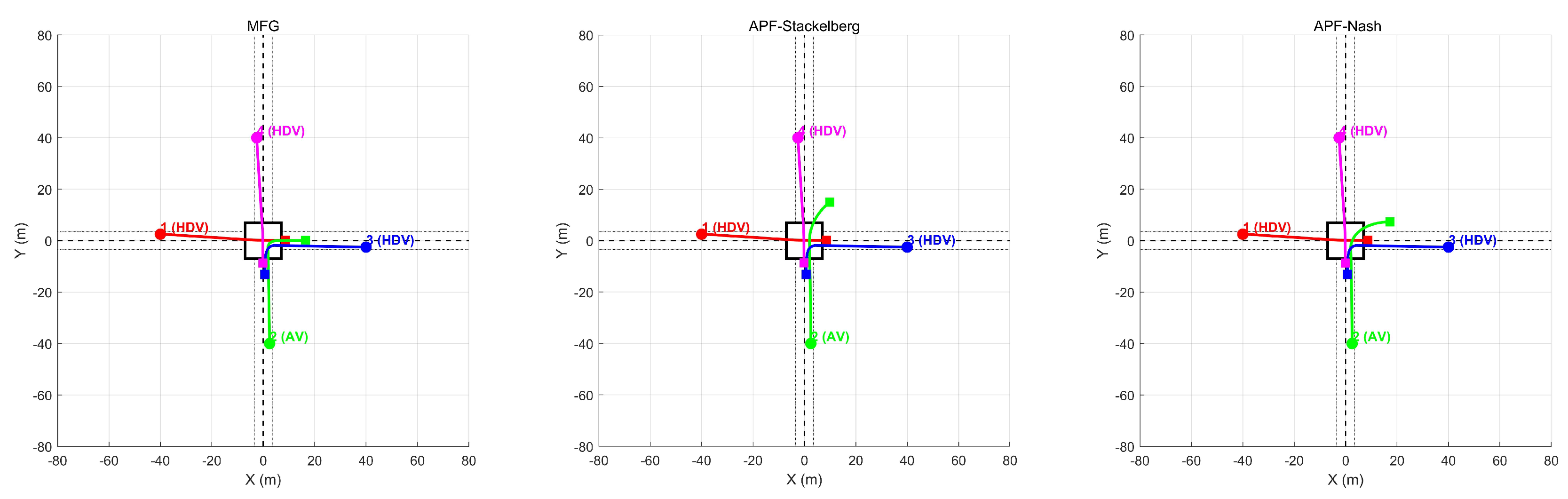

5.1. Verification for Scenario 1

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bai, X.; Peng, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, Z.; Mao, Z. Novel soft robotic finger model driven by electrohydrodynamic (EHD) pump. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE A 2024, 25, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Sakai, Y.; Funabora, Y.; Yokoe, K.; Aoyama, T.; Doki, S. Funabot-Sleeve: A Wearable Device Employing McKibben Artificial Muscles for Haptic Sensation in the Forearm. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2025, 10, 1944–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Liu, L.; Jia, F.; Luo, Y.; Jia, C.; Zhang, G.; Yang, L.; Wang, L. Robustness-aware 3d object detection in autonomous driving: A review and outlook. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, Z.; Yu, P.; Lan, J. DPL-SLAM: Enhancing Dynamic Point-Line SLAM Through Dense Semantic Methods. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 24, 14596–14607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, Z.; Yu, P.; Ye, Z.; Zhuang, H.; Lan, J. Slam2: Simultaneous localization and multimode mapping for indoor dynamic environments. Pattern Recognition 2025, 158, 111054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, H.; Siruvuri, S.V.; Budarapu, P. A machine learning-based image classification of silicon solar cells. International Journal of Hydromechatronics 2024, 7, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, M.; Onsy, A.; Haikal, A.Y.; Ghanbari, A. Path planning algorithms in the autonomous driving system: A comprehensive review. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2024, 174, 104630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, P.; Chitta, K.; Jaeger, B.; Geiger, A.; Li, H. End-to-end autonomous driving: Challenges and frontiers. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.; Hu, X.; Deng, P.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Ai, Y.; Yang, D.; Li, L.; Xuanyuan, Z.; Zhu, F.; et al. Motion planning for autonomous driving: The state of the art and future perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2023, 8, 3692–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.; Chang, Y.T.; Chen, Z.Y.; You, Z. Autonomous Driving Control for Passing Unsignalized Intersections Using the Semantic Segmentation Technique. Electronics 2024, 13, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barruffo, L.; Caiazzo, B.; Petrillo, A.; Santini, S. A GoA4 control architecture for the autonomous driving of high-speed trains over ETCS: Design and experimental validation. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Peng, Y.; Hu, C.; Ding, R.; Yamada, Y.; Maeda, S. Soft computing-based predictive modeling of flexible electrohydrodynamic pumps. Biomimetic Intelligence and Robotics 2023, 3, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Kobayashi, R.; Nabae, H.; Suzumori, K. Multimodal Strain Sensing System for Shape Recognition of Tensegrity Structures by Combining Traditional Regression and Deep Learning Approaches. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9, 10050–10056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.L.; Lim, J.; Chong, E.K.; Wang, X. Single-pixel image reconstruction based on block compressive sensing and convolutional neural network. International Journal of Hydromechatronics 2023, 6, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnu, C.; Abhinav, V.; Roy, D.; Mohan, C.K.; Babu, C.S. Improving multi-agent trajectory prediction using traffic states on interactive driving scenarios. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2023, 8, 2708–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Lu, G.; Liu, M. Risk field model of driving and its application in modeling car-following behavior. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 23, 11605–11620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triharminto, H.H.; Wahyunggoro, O.; Adji, T.; Cahyadi, A.; Ardiyanto, I. A novel of repulsive function on artificial potential field for robot path planning. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering 2016, 6, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Gao, F.; Li, K. Humanlike decision and motion planning for expressway lane changing based on artificial potential field. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 4359–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, Z.; Zhuang, H.; Lan, J. A conflicts-free, speed-lossless KAN-based reinforcement learning decision system for interactive driving in roundabouts. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.08242 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Zhao, D.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, W.; Flynn, D.; Jiang, Y.; Tian, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y. Efficient and Balanced Exploration-driven Decision Making for Autonomous Racing Using Local Information. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhao, D.; Lin, Z.; Flynn, D.; Zhao, W.; Tian, D. Balanced reward-inspired reinforcement learning for autonomous vehicle racing. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual Learning for Dynamics & Control Conference. PMLR; 2024; pp. 628–640. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, W.; Flynn, D.; Ansari, S.; Wei, C. Evaluating Scenario-based Decision-making for Interactive Autonomous Driving Using Rational Criteria: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.01886 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, T. Training-efficient deep reinforcement learning for safe autonomous driving. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 2025.

- Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, F.; He, M.; Mao, Z.; Huang, X.; Ding, J. Predictive modeling of flexible EHD pumps using Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks. Biomimetic Intelligence and Robotics 2024, 4, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, C.; Lei, L.; Yang, S.X. AVDDPG-Federated reinforcement learning applied to autonomous platoon control. Intelligence & Robotics 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Mahapatra, A.; Singal, A.; Goel, D.; Huang, K.; Scardapane, S.; Spinelli, I.; Mahmud, M.; Hussain, A. Interpreting black-box models: a review on explainable artificial intelligence. Cognitive Computation 2024, 16, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Peng, Y.; Mao, Z. Large language models for human–robot interaction: A review. Biomimetic Intelligence and Robotics 2023, 3, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Cao, B.; Qu, S.; Lu, F.; Gu, S.; Chen, G. Retrieve-then-compare mitigates visual hallucination in multi-modal large language models. Intelligence & Robotics 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Di, X.; Du, Q.; Chen, X. A game-theoretic framework for autonomous vehicles velocity control: Bridging microscopic differential games and macroscopic mean field games. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.06053 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Veer, S.; Karkus, P.; Pavone, M. Interactive joint planning for autonomous vehicles. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2023, 9, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.; Cui, Y.; Wu, C.; Guo, G. Designing External Displays for Safe AV-HDV Interactions: Conveying Scenarios Decisions of Intelligent Cockpit. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th CAA International Conference on Vehicular Control and Intelligence (CVCI). IEEE; 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Tan, C.; Yan, L.; Zhou, J.; Yin, G.; Yang, K. Interaction-Aware Trajectory Prediction for Safe Motion Planning in Autonomous Driving: A Transformer-Transfer Learning Approach. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.01475 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, B.; Wang, F.; Lin, C.; Wu, D. Modeling HDV and CAV mixed traffic flow on a foggy two-lane highway with cellular automata and game theory model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Deng, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, B.; Li, G.; Jiang, Y. Optimal lane-changing trajectory planning for autonomous vehicles considering energy consumption. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 225, 120133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, B.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Cheng, S.; Chen, Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, L. Dynamic lane-changing trajectory planning for autonomous vehicles based on discrete global trajectory. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 23, 8513–8527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, R.; Tsourdos, A.; Chai, S.; Xia, Y.; Savvaris, A.; Chen, C.P. Multiphase overtaking maneuver planning for autonomous ground vehicles via a desensitized trajectory optimization approach. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2022, 19, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatti, J.; Aksjonov, A.; Alcan, G.; Kyrki, V. Planning for safe abortable overtaking maneuvers in autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC). IEEE; 2021; pp. 508–514. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Du, B.; Qin, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, L. A Stackelberg game-based approach to transaction optimization for distributed integrated energy system. Energy 2023, 283, 128475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Orsag, M.; Han, K. Lane-merging strategy for a self-driving car in dense traffic using the stackelberg game approach. Electronics 2021, 10, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, P.; Huang, C.; Hu, Z.; Xing, Y.; Lv, C. Decision making of connected automated vehicles at an unsignalized roundabout considering personalized driving behaviours. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2021, 70, 4051–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, D.M. Nash equilibrium. In Game theory; Springer, 1989; pp. 167–177.

- Hang, P.; Lv, C.; Huang, C.; Cai, J.; Hu, Z.; Xing, Y. An Integrated Framework of Decision Making and Motion Planning for Autonomous Vehicles Considering Social Behaviors. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2020, 69, 14458–14469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaddoni, S.H.; Taheri, S.; Ahmadian, M. Optimal VSC design based on Nash strategy for differential 2-player games. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics. IEEE; 2009; pp. 2415–2420. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.; Chen, X.; Di, X.; Du, Q. Dynamic driving and routing games for autonomous vehicles on networks: A mean field game approach. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2021, 128, 103189. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z.; Hosoya, N.; Maeda, S. Flexible electrohydrodynamic fluid-driven valveless water pump via immiscible interface. Cyborg and Bionic Systems 2024, 5, 0091. [Google Scholar]

- Alawi, O.A.; Kamar, H.M.; Shawkat, M.M.; Al-Ani, M.M.; Mohammed, H.A.; Homod, R.Z.; Wahid, M.A. Artificial intelligence-based viscosity prediction of polyalphaolefin-boron nitride nanofluids. International Journal of Hydromechatronics 2024, 7, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, D.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Z.; Bai, X.; Mao, Z. Predicting flow status of a flexible rectifier using cognitive computing. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 264, 125878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).