4.1. A Brief Description of Dynamic and Coherent Number States

Let us follow the propagation of a spontaneously emitted photon in the optically nonlinear process of spontaneous parametric down-conversion (SPDC) of a pump photon. This photon, and similarly its parametric pair-photon, can be emitted in any direction compatible with the emission pattern of an electric dipole as the oscillating electron can move about the equilibrium position to absorb any residual momentum. When these two photons are launched in the same direction as the propagating pump, even in the absence of phase-matching, these photons can be amplified [

15] as their phases vary rapidly, through the phase-pulling effect, leading to the optimal relative phase for maximal amplification – sees

Appendix A. Thus, both the signal and idler beams generate groups of identical photons which are described mathematically by means of the mixed time-frequency representation [

14], i.e., a time-varying number of monochromatic photons whose spatially limited field profiles interact with local electric dipoles giving rise to quantum Rayleigh spontaneous and stimulated emissions [

13,

14]. When such a group of monochromatic photons crosses a spectral filter, the internal back-and-forth partial reflections spread the group temporally which is the equivalent of and mistaken for the narrowing of a Fourier spectrum.

These two physical processes of parametric amplification and time-stretching, and the quantum Rayleigh scattering of single photons [

13] are missing from the conventional interpretation of quantum optics, which leads to the need for ‘counter-intuitive’ interpretations of quantum nonlocality. Groups of photons generated by parametric amplification of spontaneous emission in a nonlinear crystal – see

Appendix A – will undergo temporal stretching, splitting and delays as they propagate through spectral filters, Bragg gratings, beam splitters or other devices [

6,

7,

14,

15], so that for a continuous pumping of the nonlinear crystal a quasi-continuum of photons will be present in the experimental system at any given time. A combination of a low level of amplification of a spontaneously emitted photon into a group of identical photons along with propagation losses sustained in dielectric media, and with the reflective dispersion of photons and the imperfect quantum efficiency of photodetectors, will result in the effective number of photons being low enough not to trigger a detection below a threshold. This threshold is possibly related to the background noise radiation and the limited number of electrons available for photon-dipole interactions in the detector. Thus, what seemed to be a “classical” case turns into a quantum regime-like detection with photon number fluctuations and randomly generated phases determining the instantaneous ratio

of interference-detected photons to the sum of input numbers

of photons. The instantaneously measured ratio

follows the conventional interference pattern [

14] of

where the quantum efficiency, the visibility and the phase difference between the interfering beams are denoted by

,

and

, respectively. The instantaneous measured values of the ratio

will be added and normalised to the total number of initial events or statistical samplings. This can be done in one step for a wave front carrying a large number of photons, or sequentially for one photon at any given instance. In eq. (13), the instantaneous values are not predicted by the quantum formalism based on the mixed quantum state. These instantaneous values of

are summed and normalized to the number of ensemble events, each run corresponding to time-varying pure states of the dynamic and coherent number states which were analysed in refs. [

14,

15]. As the probability of detection is proportional to the instantaneous intensity or number of time-varying photons [16; eq. 1.37], i.e., the stronger the optical field of interference is, the higher the probability of detection will be.

Following the results of [

14,

15], we identify dynamic and coherent number states

and recall the non-Hermicity of the field creation and annihilation operators [

16]. We find for the number states that

, which provides the complex field of the amplitude, for the time-dependent evolutions of photonic beam fronts [

14] associated with the wave function

. Similarly, the expectation values of the instantaneous number of photons carried by a mode, the optical field magnitude and its phase are readily evaluated with the state

, for the respective photonic operators [

14]. The evolution of the complex amplitude is determined by means of the Ehrenfest theorem for the expectation value [

14]. Additionally, the longitudinal

and lateral

distributions of one photon are calculated from differential equations derived from a combination of the Maxwell equations and the quantum expectation values. These profiles are given in closed form by [

14]:

where

are the instantaneous location of the photon and its radial peak. The wavelength, the refractive index and the dielectric constant of the medium are denoted, respectively, by

The visibility

is given in terms of the numbers of photons

reaching simultaneously the photodetector. The polarization states of the beams are

. The field profiles of eqs. (14) describe a monochromatic photon and correspond to the mixed time-frequency representation of signals with a time-varying spectrum, i.e.,

indicating a time-varying number of monochromatic photons [

14]. These profiles will be used to evaluate the temporal overlap of coherence

in a cubic beam splitter, and the lateral coupling coefficient in a fibre beam splitter [

14,

15].

4.2. Examples of Correlations

A few examples of experimental results which are explained by means of the intrinsic field of photons are presented in this subsection.

Example 1 – The experimental results of ref. [

6] are easily explained by taking into consideration the unavoidable parametric amplification of spontaneously emitted photons [

12,

14,

15] – see

Appendix A for a brief summary.

With multiple photons propagating in both input orthogonal states of polarization

H and

V, one can control the output intensity through interference of the intrinsic fields [

14] of groups of identical photons coupled onto the filter’s polarization state of rotation angle

.

A group of identical photons generated through amplification in the original crystal source is carried by a linearly polarized radiation mode. These photons couple into the local eigenmodes H and V of polarization-rotating waveplates. As the two local eigenmodes H and V reach the polarization filter at location A or B, their photons are projected onto the polarisation analyser’s orientation of angle . As a result, a rotation dependent interference pattern is created with the photo-current being proportional to the instantaneous number of photons .

At location B, the detector’s output intensity for fluctuating numbers of photons

and the expectation number

of the interference between the projected pure states, take the forms [

14,

15]:

where

is the quantum efficiency of photon detection,

is the visibility with

, and

is the temporal overlap between the intrinsic optical fields of the photons whose derivation is available in [

14]. The input time-varying phases of the local two polarization beams are

, but since they originate from the same incoming input polarization mode coupled onto the eigenstates of the polarization rotator, their original phase difference is zero. The time-average is indicated by the angled brackets for time-dependent phase fluctuations and photon number fluctuations.

A basic principle of scientific methodology for reproducibility of outcomes states that identical systems operated under identical conditions will yield identical distributions of output data. For ref. [

6] the orthogonal inputs are

(

. The rotational invariance of the detection filters aligned with the incoming photon’s polarization leads to an offset angle difference of

for the initially maximal and identical, superposed fringes of interference for correlation values. These settings and photocurrents are created locally and the curves of Figure 1 of [

6] are determined locally at station B, while the setting at location A is kept constant.

Experimentally, correlations

of detected photons are probed by the product of the discretized photocurrents

[

14] by using eq. (15

b), so that:

where the constant of proportionality

K converts the photocurrent into a number of photons. The current at location A is constant with a bias angle

while the photocurrent at location B will have an angle-dependent pattern as described in eq. (15

a). The local visibilities are

(with

j =

A or

B). Maximizing the correlation product

by overlapping the two interference patterns which are sampled discretely above a field-related detection threshold – and for identical configurations under offset rotation or angle shifting – leads, for

, to a bias phase of

being included in eq. (16). Thus, the varying interference term becomes

which reproduces the interference fringes of Figure 1 of ref. [

6] for

.

Example 2 - An earlier experiment [

7] employed an intensity Franson interferometer [

18] comparing the outcomes of two separate 1 x 1 unbalanced Mach-Zehnder interferometers (MZI). The outcomes of this configuration can easily be explained in terms of the two separate and synchronized interference patterns as in eq. (16). Instead of a polarization rotation, a locally controlled phase-shift

brings about the interference pattern of apparent coincident detections which have, as before, a very low success rate using a continuous-wave laser pump. The interference is local because it involves only the amplified spontaneous emission of one output mode, i.e, signal or idler of the parametric source, reaching the local detector in the form of two sub-groups of photons after the original group passed through a spectral filter that spreads out, or stretches, the input group of photons by internal back and forth partial reflections.

With the SPDC signal and idler beams being directed separately to location A and location B, respectively, a group of photons is split by internal partial reflections into two parts 1 and 2 in the spectral filter with the second sub-group being delayed in time. As each sub-group reaches the unbalanced MZI, a fraction of the first partial group runs along the longer arm of the MZI and interferes with the fraction of the second partial group that followed the shorter arm of the MZI. As both partial groups split from the same original group through temporal delays in a spectral filter, they share the same original spontaneous phase . Upon reaching the same photodetector after crossing an MZI, they create interference fringes through an external phase modulation in one of the arms. At the other detector, the level of detection is kept constant – possibly maximized – being triggered by a randomly detected photon. Thus, the correlation takes the form

where the subscripts of the phases

denote the partial group (1 or 2) of photons, and the destination (

A or

B). With identical phase fluctuations, for the parametric case of the signal being directed to location

A and the idler going to the location

B, one has

and

as the two identical systems operate separately but identically. This is the case of ref. [

7] where the experiment relies on filters such as a Fabry-Perot cavity or a fibre Bragg grating, so that the original group of photons was split with one partial group being delayed by internal partial reflections as indicated by the bias phases

and

.

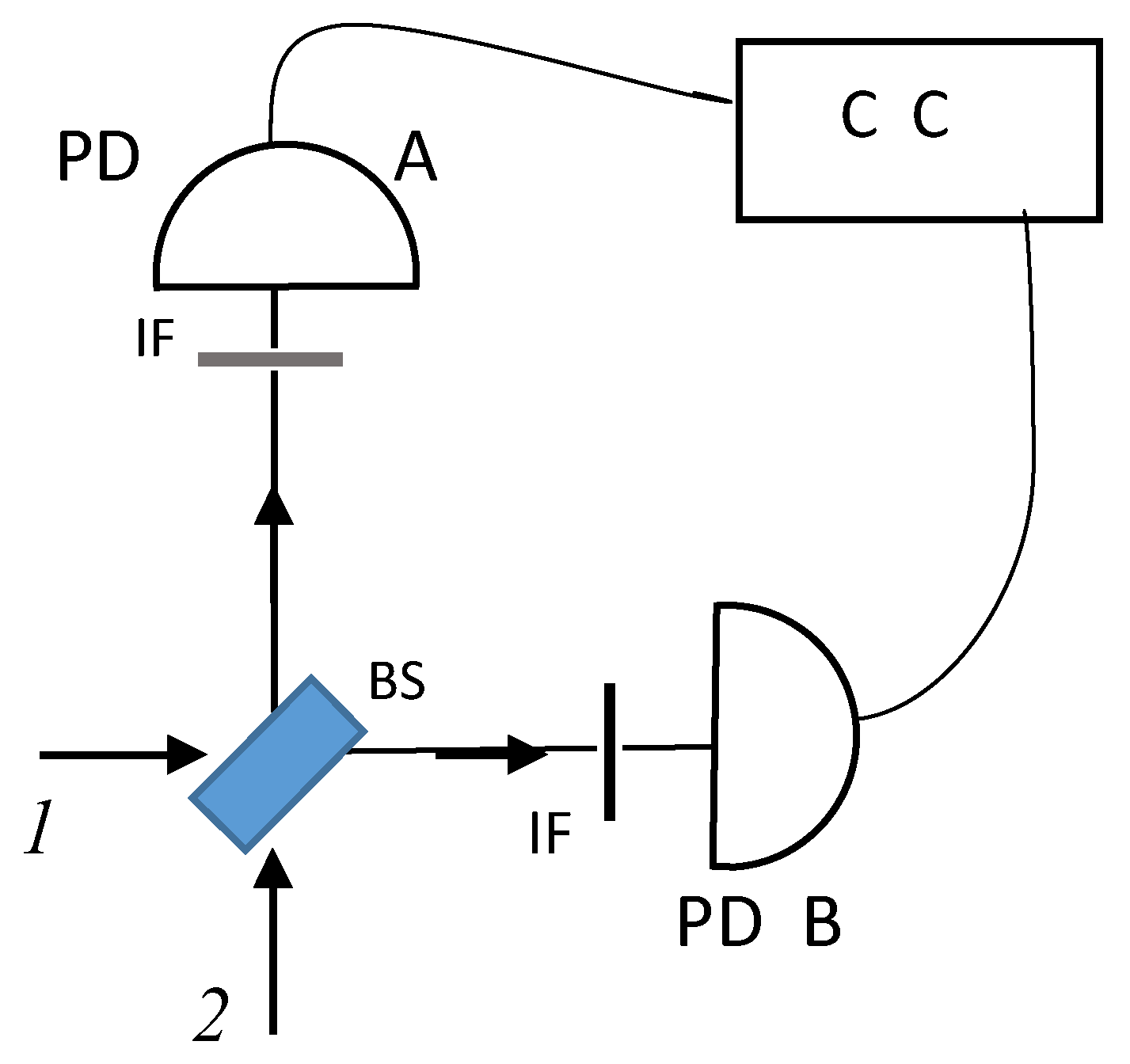

Example 3 -The case of the Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) dip is illustrated in

Figure 1 and was explained in ref. [

14] by recalling that the two outputs share the same random phase-difference with

and

. Thus, in eq. (17

a),

. The internal reflection from a higher-index medium inside a cubic beam splitter induces a phase-shift

. Using the identity

, in eq. (17) the average over the random phases evenly distributed in the range of

results in term

vanishing while the first term of negative unity should be counted twice because the phases

can interchange values for the same outcome. Alternatively, the contributions in eq. (17) of the terms

add up to zero by integrating over the phase interval of

while for

, the product term of eq. (17) becomes

and its contributions in the range

cover two periods of

rad with two positive values of 1/2 adding up to negative unity. It should be emphasized that the instantaneous values of the interference terms are measured to build up an ensemble of measurements, and the statistically averaged value is calculated at the end of the data acquisition through normalization with the number of initiated events, whether recorded or not by the detectors. The average does not involve a phase integration as suggested in ref.

[20] where the mixed quantum state of the time-independent coherent state was employed. The shortcomings of this approach [

20] are listed in the discussion

Section 5.

The visibility coefficient (with j = A or B), contains two factors. The ratio of photon numbers will determine the visibility

regardless of the total number of photons reaching the photodetector and, in fact, connects smoothly the quantum regime of sequential counting of events with the classical regime of one-step counting of photons. With optimal values of unity

, the correlation function of eq. (17

a) vanishes for

. These derivations are compatible with the experimental results of refs. [

19].

As in the previous

Example 2, spectral filters will reduce the initial number of photons in each group of identical photons exiting the SPDC source while discretely spreading the initial group by back and forth partial reflections. This requires a minimum number of initial photons so that enough of the dwindling group will survive the propagation to the photodetector. This is consistent with the experimental correlations with uncorrelated photons [

21].

The visibility higher than 0.5 reported by ref. [

22] was obtained with fluctuating pulses of multiple photons attenuated, allegedly, to the level of one photon. Yet, no explanation was provided therein about the quantum Rayleigh scattering of single photons.

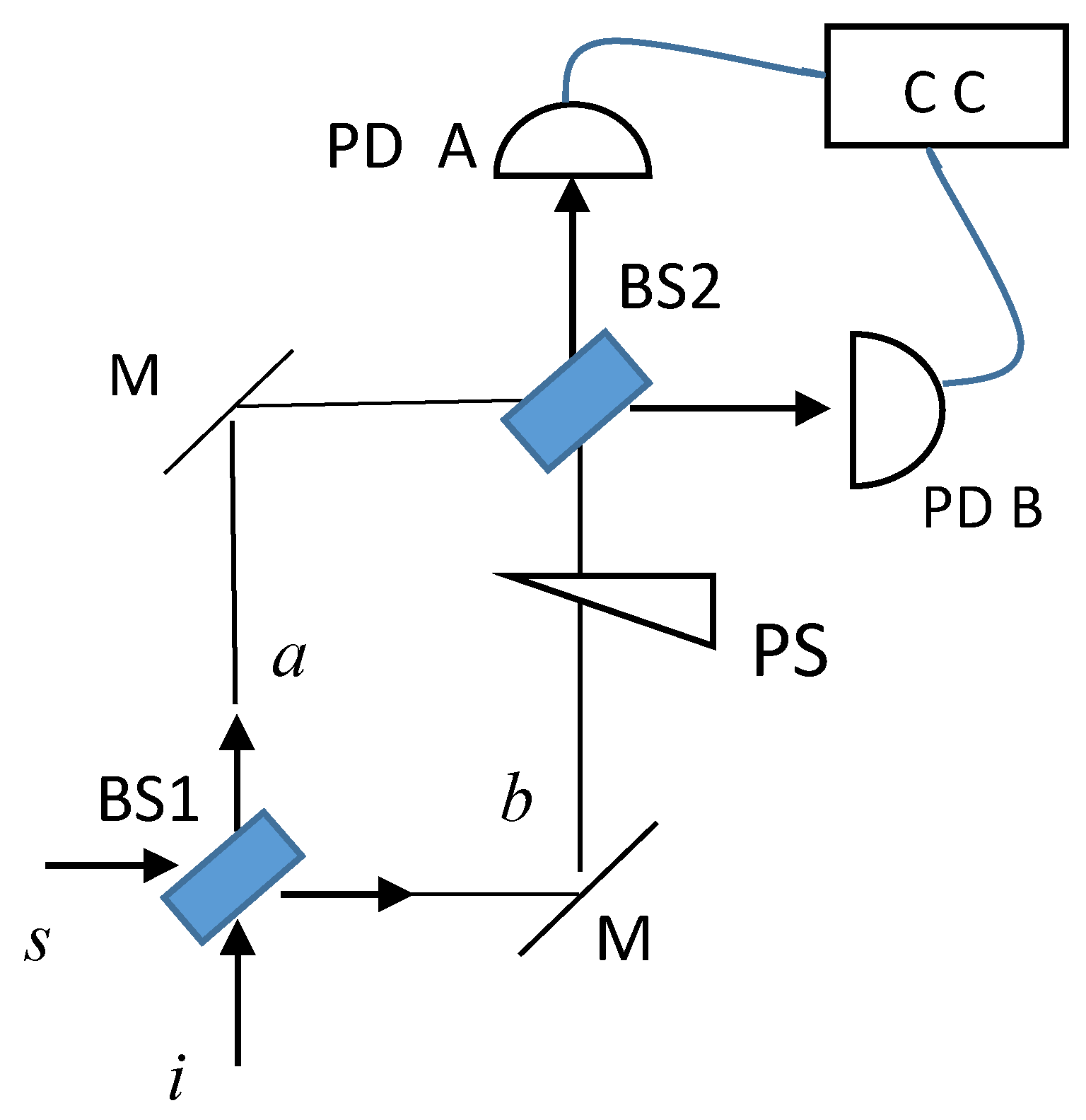

Example 4 - Next, we recall the parametric phase-pulling effect [

15,

23] leading to a phase correlation between the signal (

s) and the idler (

i) waves, i.e.,

, for any initial phases of weak waves such as spontaneous emission, with the coherent phase of the pump photons given by

. As a result, at the either output

A or

B of the second cubic beam splitter of a 2 x 2 MZI as illustrated in

Figure 2, one finds a constant phase relation

or the

term [

14] of the correlation function

, with subscripts a and b denoting the two arms of the MZI, one of which may include a modulation or bias phase

, and taking into account the phase shifts at the internal interfaces of the beam splitters. This phase relation will result in nonvanishing intensity correlations in the case of a 2 × 2 Mach-Zehnder interferometer. This equality of

also applies to the two-source experiment outlined in Figure 3 of ref. [

18] with subscripts a and b replaced by numbers 1 and 2,

respectively, as well as

corresponding to the pump’s coherent phase modulation. In Figure 6 of ref. [

18], the second source is driven by the idler beam from the first source so that

, with

being a bias phase of transition. Hence, one finds this phase equality

so that, it is not “the relationship between interference and indistinguishability“ [

18] that is responsible for the intensity interference but the phase pulling effect of

which maximizes the parametric gain [

15] (see

Appendix A).

The random phases of the spontaneously emitted photons which are parametrically amplified in the crystal of their emission are missing from the conventional interpretation of the Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) dip [

18,

20]. By contrast, the random phases of a spontaneously emitted photon are directly associated with the dynamic and coherent number states composed of two consecutive number states which deliver

c- numbers that behave in line with the Ehrenfest theorem of the time evolution of the expectation values [

14,

15].

Therefore, there is no need for entangled photons – apparently created by SPDC sources – which transcend time and space to have their probability amplitudes somehow interfere in order to explain the coincidence counting of photons by two separate photodetectors. The only requirement is that the two groups of photons are split between the two detectors – with an interface-induced phase – and are synchronized at the detection stage. Additional physical shortcomings of the Mandel approach based on entangled single photons are outlined in

Appendix B emphasizing the confusion about the Dirac notation which requires a spatial integral to be evaluated, apparently ignored by the Glauber theory of detection [

16].