1. Introduction

1.1. Brief Overview of Forensic Evidence Collection

Forensic science, an intricate discipline at the intersection of science and criminal justice, strives to unravel mysteries by analyzing evidence that often serves as the silent witness to a crime [

1]. The crucial process of gathering evidence, which can make or break the quest of justice, is at the center of any criminal investigation. Forensic evidence collection has long relied on conventional techniques, such as DNA analysis and fingerprint analysis [

2]. But in the dynamic field of forensic science, scientists and investigators are always looking for new ways to improve the effectiveness and dependability of this crucial stage.

Forensic evidence collection is a meticulous and multidisciplinary endeavor, encompassing a wide array of materials and substances. The traditional techniques employed, while invaluable, are not without limitations. Problems like contamination, deterioration, and the complexity of crime scenes frequently present obstacles that call for creative solutions [

3]. In this quest, researchers and scientists have started looking for unconventional partners, and one such partner has surfaced from the complex natural world: ants [

4].

This paper delves into the unconventional realm of using ants as forensic evidence collectors. The constraints of human-driven systems have led to an investigation of alternative, nature-inspired solutions, even though established methods have demonstrated their value [

5]. Ants provide a distinct viewpoint in the realm of forensic research because of their extraordinary skills and intuitions [

6]. By understanding and harnessing the natural behaviors of certain ant species, researchers aim to revolutionize the way evidence is located, transported, and ultimately analyzed in criminal investigations [

7].

Understanding the dynamic nature of forensic science is crucial as we begin our investigation into ants as forensic evidence collectors. Incorporating non-traditional techniques not only creates new opportunities for discovery but also challenges assumptions regarding the limits of forensic investigation [

8]. By illuminating their function in gathering evidence and their potential influence on the development of forensic science, this review will reveal the potential of ants as priceless friends in the search for the truth.

1.2. Importance of Efficient and Reliable Evidence Collection in Criminal Investigations

In the intricate realm of criminal investigations, the quest for truth hinges upon the ability to assemble and decipher evidence accurately [

9]. The saying “justice delayed is justice denied” emphasizes how important it is to gather evidence quickly and accurately in order to promote accountability and fairness in legal systems. This crucial duty not only helps prove guilt or innocence but also significantly influences the stories that are told in courtrooms [

10].

Forensic evidence collection forms the cornerstone of any criminal investigation, serving as the conduit between the crime scene and the judicial process. Its significance is emphasized by the fact that the integrity of the evidence gathered affects not only the results of specific cases but also the criminal justice system’s overall credibility [

11]. It is impossible to overestimate the importance of accuracy and completeness in this procedure, since any error or carelessness in gathering evidence could result in false allegations or the exoneration of those who are guilty [

12].

Forensic investigators have historically used a wide range of techniques, from DNA profiling to fingerprint analysis, to establish a sequence of events and identify the criminals. Nevertheless, despite their undeniable value, these traditional methods have drawbacks [

13]. The emergence of innovative and unconventional methods in forensic science is driven by the recognition of these limitations and the quest for more efficient, reliable, and sometimes, unexpected avenues for evidence collection [

14].

This study explores one such unconventional yet intriguing method: using ants to gather forensic evidence. Understanding the larger context of forensic evidence collection is essential as we investigate this fascinating option [

15]. Our legal systems’ effectiveness depends on our capacity to adjust, develop, and adopt strategies that improve the precision and comprehensiveness of the evidence offered in court while simultaneously expediting the investigation process [

16].

By examining the importance of efficient and reliable evidence collection, we lay the groundwork for an exploration into the fascinating world of ant-assisted forensic science [

17]. We are encouraged by this voyage to question established ideas, push the limits of forensic techniques, and take into account innovative concepts that could completely alter the field of criminal investigations [

18]. Let’s keep in mind the significant influence that cutting-edge techniques for gathering evidence can have on the fight for justice and the upholding of the truth in the face of hardship as we explore the complexities of this subject.

1.3. Introduction to the Use of Ants in Forensic Science

Forensic science stands as a crucial pillar in the realm of criminal investigations, where meticulous evidence collection plays a pivotal role in unraveling mysteries and delivering justice. Forensic experts have historically used a wide range of methods, from DNA profiling to fingerprint analysis, to collect evidence. Ants, on the other hand, have become an intriguing and unusual ally in recent years [

19]. These tenacious insects, which are frequently disregarded in forensic settings, have natural tendencies that make them ideal for gathering important evidence.

Despite their effectiveness, the traditional techniques of gathering evidence frequently have drawbacks, including the requirement for specialized equipment, time constraints, and weather-dependent viability. We set out on a quest to investigate the potential of these small but amazing creatures to transform the field of evidence recovery as we dig deeper into the usage of ants in forensic research [

20]. This creative method makes use of ants’ innate instincts, taking advantage of their unmatched capacity to find, recover, and move objects of interest in a very effective and methodical way.

Ants, renowned for their collective intelligence and sophisticated communication systems, exhibit a level of organization that can be harnessed to streamline forensic processes. In addition to offering an innovative approach for collecting evidence, the use of ants in forensic research may help overcome some of the drawbacks of more conventional methods [

21]. Ants may prove to be crucial collaborators in revealing buried realities at crime scenes and decomposition sites, giving forensic investigators an extra tool to improve the precision and dependability of their results.

The history of forensic evidence collecting, the changing landscape of investigative techniques, and the backdrop of ant use in forensic science will all be covered in the present study [

22]. Understanding the behavior and capacities of ants can help us understand why some species are especially well-suited for this use. Additionally, we will investigate the mutually beneficial link between ants and decomposition processes, revealing the complex interplay that makes ants useful contributors to time since death estimation [

23].

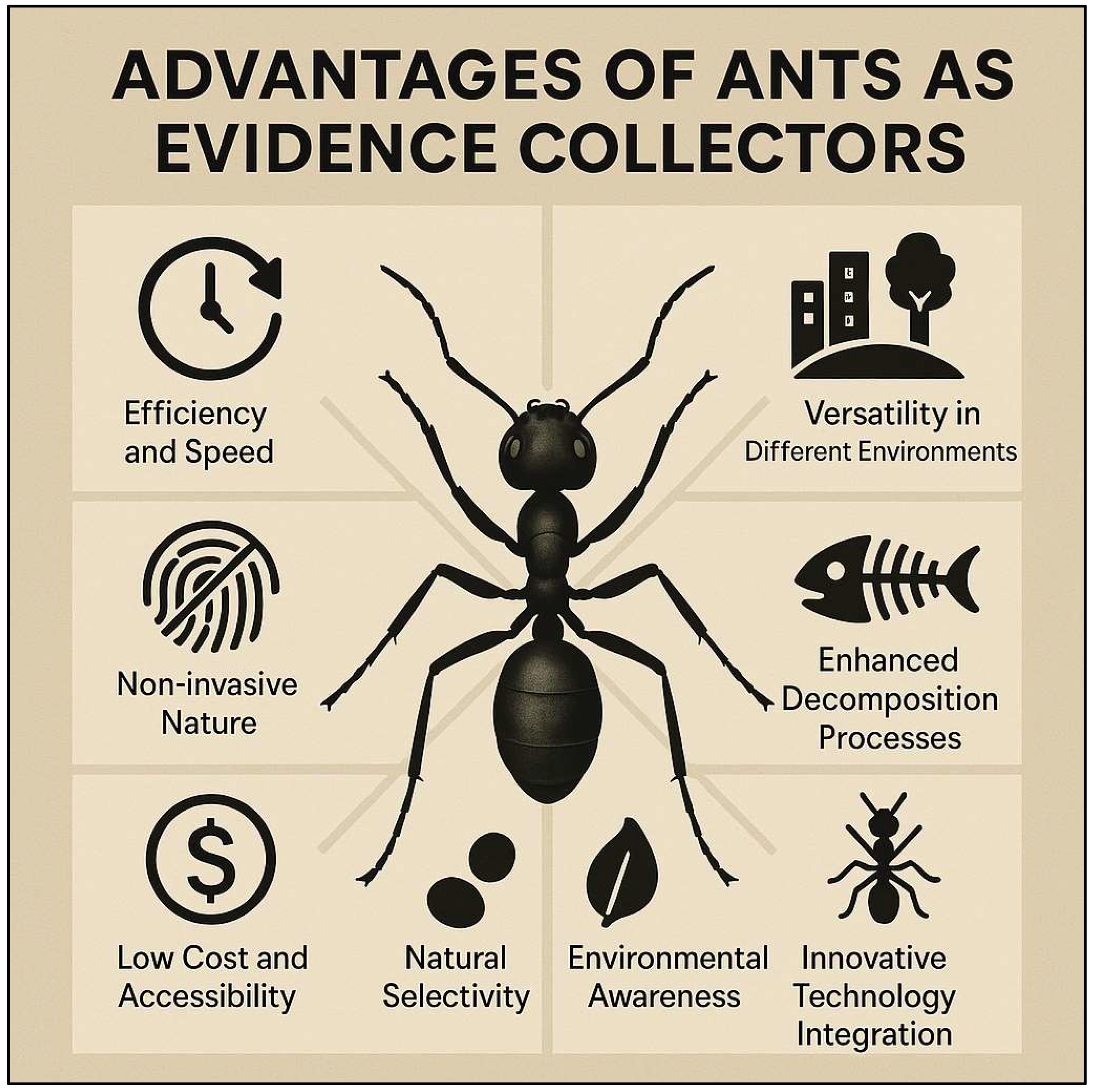

As we work through this novel strategy, we will provide actual case studies that illustrate how ants have been crucial to gathering evidence and eventually impacted the results of criminal investigations. We’ll discuss ants’ benefits as evidence collectors, such as their quickness, effectiveness, and capacity to adjust to a variety of environmental circumstances [

24]. But every method has drawbacks, and we will look closely at the moral issues and possible limitations surrounding the use of ants in forensic research.

In essence, this exploration of ants as forensic evidence collectors invites us to reconsider and expand the boundaries of conventional forensic methodologies [

25]. It pushes us to acknowledge the unrealized potential of nature and promotes a mutually beneficial link between the complex ant activities and the stringent standards of forensic investigations [

26]. As we set out on the quest, the use of ants in forensic science could represent a paradigm shift that brings in a new era of criminal justice and evidence gathering.

2. Background

2.1. Historical Perspective on Forensic Evidence Collection Methods

With roots in ancient civilizations when basic investigation methods were used to solve crimes, forensic evidence collecting has undergone tremendous change over the ages. The historical perspective on forensic evidence gathering techniques sheds light on the early investigators’ varied approaches and the slow evolution of forensic science.

- 1.

Ancient Civilizations:

As rulers looked for methods to settle conflicts and carry out justice, early forensic science developed in ancient civilizations including Babylon, Egypt, and Rome [

27]. Basic techniques like fingerprinting clay tablets and utilizing fingerprints on papers for authentication were part of these early forensic efforts [

28].

- 2.

Middle Ages:

The idea of “trial by ordeal” gained popularity during the Middle Ages as legal systems became more organized [

29]. In order to establish guilt or innocence, techniques like the hot iron and cold-water tests were used, which reflected an antiquated method of gathering forensic evidence based on bodily responses to perceived injustices [

30].

- 3.

Renaissance and Early Modern Period:

A change toward a more scientific method of inquiry was highlighted by the Renaissance. The application of medical expertise in judicial investigations was first established by the Italian physician Fortunato Fidelis in the 17th century [

31]. During this time, forensic pathology also gained popularity, and people like Ambroise Paré helped to clarify how wounds relate to criminal activity [

32].

- 4.

Late 19th to Early 20th Century:

The late 19th century witnessed significant advancements in forensic evidence collection. Anthropometry is a methodology of measuring and classifying bodily traits that was introduced as a means of criminal identification by the French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon [

33]. Modern fingerprint analysis was made possible by Sir Francis Galton’s fingerprint research, which further transformed forensic identification [

34].

- 5.

The Role of Sherlock Holmes and Fiction:

Through fictional figures like Sherlock Holmes, forensic science also became more well known in the late 19th and early 20th centuries [

35]. The value of deductive thinking and the methodical gathering of evidence were highlighted in Arthur Conan Doyle’s detective stories, which impacted public opinion and served as an inspiration for actual forensic procedures [

36].

- 6.

Emergence of DNA Evidence:

James Watson and Francis Crick’s discovery of the structure of DNA in the subsequent half of the 20th century was a revolutionary advancement [

37]. The foundation for DNA profiling, a cutting-edge forensic technique that is now essential to criminal investigations, was established by this discovery [

38].

- 7.

Contemporary Forensic Evidence Collection:

Digital forensics, entomology, and forensic anthropology are only a few of the many specialized areas that make up modern forensic science [

39]. The scope and precision of forensic evidence gathering procedures have been further increased by technological developments like computer forensics, DNA sequencing, and the application of sophisticated imaging techniques [

40].

Gaining an appreciation for the ongoing innovation and improvement in the field of forensic evidence collecting requires an understanding of its historical background. The evolution of DNA profiling from ancient trial by ordeal to modern DNA profiling illustrates the persistent human search for precise and reliable methods to solve criminal mysteries.

2.2. Challenges and Limitations of Traditional Evidence Collection

A vital component of criminal investigations is the gathering of forensic evidence, which offers vital information that can make or break a case. Conventional approaches have been used for a long time, but as

Figure 1 illustrates, they have inherent difficulties and restrictions that may affect the precision and effectiveness of the investigation.

- 1.

Contamination Risks:

Traditional evidence collection methods often involve physical contact between investigators and the crime scene. Because investigators may inadvertently bring foreign elements, including skin cells, hair, or fibers, to the crime scene, this intimate contact raises the possibility of contamination. Contamination raises doubt on the validity of the results and jeopardizes the integrity of the evidence [

41].

- 2.

Cross-Contamination:

The possibility of cross-contamination is a major concern in multi-scene crime investigations. Investigators may transport trace evidence from one scene to another when they travel between places. This may cause the evidence to be interpreted incorrectly and make it more difficult to draw a direct connection between the evidence and the crime [

42].

- 3.

Destructive Sampling:

Traditional evidence collection methods often involve the removal of physical samples from the crime scene. This can be harmful by nature, yet it is required for laboratory analysis. Sample removal may change the crime scene’s initial condition, making it more difficult to reconstruct what happened. Furthermore, the scope and complexity of forensic investigations may be impacted by small sample numbers [

43].

- 4.

Time Sensitivity:

Evidence may deteriorate or change over time in certain situations, and the conventional collection method takes a long time. Delays in gathering and analyzing evidence may affect the success of the investigation and may lead to the loss of important information. In situations involving biological evidence, like DNA, this kind of sensitivity is especially important [

44].

- 5.

Subjectivity in Observation:

Traditional evidence collection becomes rather subjective due to human factors. A crime scene may be interpreted differently by different investigators, which could result in differing results. This subjectivity raises questions regarding the impartiality of the investigation process and may affect the validity and dependability of the evidence offered in court [

45].

- 6.

Limited Technological Integration:

While many facets of forensic science have changed as a result of technological advancements, traditional ways of gathering evidence have been slower to adopt new technologies. The effectiveness and precision of evidence collection may be constrained by the use of manual techniques, particularly in contrast to more contemporary and automated procedures [

46].

- 7.

Resource Intensity:

Conventional evidence gathering often calls for a large investment of time, money, and manpower. The scalability of forensic operations and investigative budgets may be hampered by this resource intensity. Because of resource limitations, certain cases can thus get less attention or undergo insufficient forensic analysis [

47].

Understanding these challenges and limitations highlights the need for continuous innovation in forensic science. To get beyond these drawbacks and improve the accuracy of evidence gathering in criminal investigations, it becomes crucial to investigate alternate techniques, such as incorporating technological solutions and using unusual strategies like ants.

2.3. The Emergence of Unconventional Methods, Including the use of Ants in Forensic science

Forensic science, the application of scientific methods to the investigation of crimes, has continually evolved to meet the challenges posed by the ever-changing landscape of criminal activities. In the past, collecting forensic evidence mostly depended on established protocols, technical developments, and human expertise. To improve the effectiveness and dependability of forensic investigations, however, the drawbacks and restrictions of traditional techniques have prompted the research of novel and unusual strategies [

48].

Particularly in cases involving decomposition, outdoor crime scenes, and the search for human remains, these limits were acknowledged. Conventional approaches frequently encounter challenges such contamination, the requirement for substantial resources, and the quick deterioration of evidence. In order to overcome these obstacles, forensic scientists and entomologists started investigating alternative, nature-inspired methods [

49].

The use of ants to gather forensic evidence is one such unusual strategy that has drawn interest. Ants have a special set of benefits when it comes to crime scene investigation because they are scavengers by nature and have highly developed senses of smell and tracking. The concept is based on how some ant species naturally find and move objects of interest, such as decaying organic materials [

50].

Ants have long been used in forensic investigations. Ants and other insects have long been acknowledged by indigenous communities and traditional knowledge as being important to the decomposition process. The scientific community has just recently started to methodically investigate and utilize ants’ potential as useful aids in the gathering of forensic evidence, but [

51].

The emergence of this unconventional method is a testament to the interdisciplinary nature of forensic science, where collaboration between entomologists, forensic experts, and law enforcement professionals has paved the way for innovative solutions. Researchers have conducted studies to identify suitable ant species for specific environments, understand their foraging behavior, and develop protocols for integrating ants into forensic investigations [

52].

Ants’ investigation as forensic evidence collectors mark a paradigm shift in the field and gives a viable way to get around the drawbacks of conventional techniques [

53]. The potential uses of this unusual method are growing as we learn more about the complexities of ant activity and how they interact with crime scenes, creating new avenues for enhancing the precision and effectiveness of forensic investigations [

54]. The transition from conventional to unconventional approaches is a fascinating development that captures the fluidity of forensic science and its dedication to remaining on the cutting edge of methodological and technical developments.

3. Ants in Forensic Science

3.1. Overview of Ant Behavior and Capabilities

Ants, belonging to the family Formicidae, are social insects that have adapted to a diverse range of ecosystems, displaying remarkable behaviors and capabilities. This section provides a detailed exploration of the fundamental aspects of ant behavior, shedding light on their communication, foraging strategies, and organizational structures.

3.1.1. Social Structure

Ants are eusocial insects with highly organized social structures that are members of the Formicidae family. Their intricate societies demonstrate cooperative behaviors, communication, and the division of labor. To fully understand ants’ potential use in collecting forensic evidence, one must have a solid understanding of their social organization [

55].

- 1.

Eusociality in Ants:

Eusociality is a hallmark of ant colonies, characterized by overlapping generations, cooperative care of the young, and reproductive division of labor. The colony functions as a superorganism, with individuals working together for the survival and reproduction of the colony [

56].

- 2.

Castes within Ant Colonies:

There are various castes within ant colonies, and each has distinct duties. Fertile females in charge of reproduction are known as queens.

Sterile females who performed a variety of duties, including nursing, colony defense, and foraging are called as workers. Male ants that are only interested in mating with queens are known as drones.

- 3.

Division of Labor:

Ants are highly specialized, with individuals concentrating on particular duties according to their caste and age. Foraging, nursing, nest management, and defense are among the tasks. Division of labor improves the colony’s usefulness and efficiency.

- 4.

Communication and Chemical Signaling:

Ants communicate primarily through pheromones, chemical signals that convey information. Pheromones are used for trail marking, alarm signaling, and recognition of nestmates. Communication is crucial for coordinating activities within the colony.

- 5.

Nest Construction and Maintenance:

Ants use a range of resources, including soil, leaves, and even their own bodies, to build their nests. Nests provide the colony with protection, food storage, and shelter. As the colony increases, maintenance activities include repairing and enlarging the nest [

57].

- 6.

Cooperative Brood Care:

Ants exhibit cooperative care for their brood, with workers responsible for feeding, grooming, and protecting developing eggs, larvae, and pupae. This cooperative care ensures the survival and well-being of the next generation.

- 7.

Adaptive Behavior:

Ant colonies have exceptional environmental flexibility. The colony can efficiently address issues like predation, resource scarcity, and variations in temperature through collective decision-making.

- 8.

Ants as Ecosystem Engineers:

Ants play a crucial role in shaping ecosystems through their activities, such as seed dispersal, soil aeration, and nutrient cycling. Their impact on the environment extends beyond the colony boundaries [

58].

3.1.2. Foraging Behavior

As social insects, ants display intricate behaviors that are vital to their colony’s survival. Ants’ foraging habits are among their most fascinating features; they are essential to obtaining food, resources, and, as we shall see, the possibility of using them to gather forensic evidence.

- 1.

General Characteristics of Ant Foraging Behavior

Ant foraging behavior is a dynamic and well-coordinated activity that involves the search, retrieval, and transportation of food resources back to the nest. This behavior is orchestrated by complex communication systems within the ant colony, enabling efficient exploitation of their environment.

- 2.

Communication Mechanisms

Pheromones, which are chemicals that transmit information about food supplies, nest sites, and possible threats, are the main means of communication for ants. In order to direct other members of the colony to the resources they have found, foraging ants create pheromone trails. Forager recruitment and organization may be impacted by the strength and makeup of these pheromone trails [

59].

- 3.

Division of Labor

Ant colonies’ division of labor is frequently associated with foraging behavior. Foragers and other specialized castes have unique behavioral and physical traits that enable them to be excellent at finding and moving food. The colony’s overall resource acquisition efficiency is improved by this division [

60].

- 4.

Trail Following

Ants employ trail following as a strategy to navigate between the nest and food sources. As ants follow the pheromone trails left by their predecessors, a collective effort emerges, optimizing the exploration of the environment and the discovery of new resources. This behavior is not only efficient for food collection but also presents opportunities for the application of ants in forensic science [

61].

- 5.

Application in Forensic Evidence Collection

Ants’ foraging behaviors have applications in forensic research, especially when it comes to identifying and collecting cadaver scent. Ants are known to be drawn to decaying organic materials, and because of their effective foraging skills, they can be useful helpers in identifying and moving forensic evidence including human remains [

62].

To sum up, knowing the nuances of ant foraging behavior offers important insights into how they may be used in forensic science. Ants can be used as efficient tools for evidence discovery and collection by utilizing their innate instincts and talents, providing a fresh and creative approach in the field of forensic investigations.

3.1.3. Problem-Solving and Adaptability

Ants are convivial insects with a wide range of skills and behaviors that help them thrive in a variety of settings. Two important facets of ant behavior are examined in this overview: adaptation and problem-solving. Comprehending these characteristics is essential for acknowledging the intricacy of ant communities as well as their possible uses in a variety of domains, including as robotics, ecology, and, as this talk will highlight, forensic science.

- 1.

Problem-Solving in Ant Colonies

Ant colonies are extremely well-organized superorganisms that depend on group decision-making to function well. Ants’ capacity to find the most effective routes to food sources is among the best-known instances of this behavior. Deneubourg and Goss [

63] showed how ants use pheromone trails to collectively enhance path choices. Ants are adept at allocating tasks throughout the colony in addition to making decisions. Depending on the colony’s immediate needs, physical capabilities, and age, responsibilities are assigned. Gordon [

64] highlighted how this system is dynamic, with ants able to transition between tasks in response to shifting demands and environments. Ants also have remarkable cognitive skills, such as memory and learning. Ants’ ability to pick up and remember visual signals to successfully navigate their environment was demonstrated by Latour B [

65]. Because of their sophisticated actions, ants are of interest to researchers studying complex systems and collective intelligence in addition to entomology.

- 2.

Adaptability of Ants

Ants exhibit remarkable adaptability, allowing them to thrive in a wide range of environmental conditions. Because of their adaptability to different environments, different species can be found in habitats that range from arid deserts to thick rainforests. Menzel and Giurfa’s work, which emphasized ant colonies’ ability to adapt to a variety of ecological niches, lends additional credence to this adaptability [

66]. Ants exhibit the capacity to adapt their social structures in response to outside influences in addition to their resistance to their surroundings. Ant colonies can change their organizational dynamics and reproductive tactics in response to shifting ecological conditions, according to Oster and Wilson’s observations [

67]. Ants also have intricate symbiotic and cooperative relationships with other living things. Ant societies are dynamic and adaptive, as demonstrated by the mutualistic interactions Menzel and Giurfa described, such as those between ants and aphids [

66].

- 3.

Implications for Forensic Science

In forensic investigations, ants’ exceptional problem-solving skills can be successfully used to find and gather evidence. Numerous studies have shown that ants have an innate ability to find and move small objects, such as those conducted by Bronstein JL et al., which proved how ants help find and efficiently move decomposing remains [

68]. Ants’ great degree of flexibility makes them useful for environmental monitoring in addition to their role in gathering evidence. Through ecological indicators, their behavioral responses to shifting environmental conditions can complement forensic investigations by offering crucial information, such as establishing the chronology of events at a crime scene [

69].

Ants’ problem-solving and adaptability showcase the intricacies of their social structures and highlight their potential applications in various fields. In forensic science, leveraging these capabilities could revolutionize evidence detection and environmental monitoring, contributing to more effective and efficient investigations.

3.1.4. Agriculture and Animal Husbandry

Ants, as social insects, exhibit a wide range of behaviors and capabilities that extend beyond their conventional roles in nature. This section delves into the specific aspects of ant behavior related to agriculture and animal husbandry, shedding light on their ecological significance and potential applications in various fields.

- 1.

Ant Societal Structure and Organization

Ants live in incredibly well-organized colonies whose members are categorized into castes according to their duties as workers, soldiers, and queens. Efficient task specialization is made possible by this intricate social structure [

70]. Ant colonies use complex communication systems, such as chemical signals (pheromones) and tactile cues, to promote cooperative behavior [

71].

- 2.

Ants as Agriculturists

Some ant species are agricultural in nature, using fungus as their main food source. For instance, fresh leaves are cut and transported to their nests by leafcutter ants, who use them as a substrate for the growth of fungi [

72]. Ant colonies’ ecological adaptability is demonstrated by this unusual agricultural practice, which incorporates mutualistic partnerships between ants and fungi [

73].

- 3.

Ants and Aphid Farming

Some ant species engage in mutualistic relationships with aphids, protecting them from predators and receiving honeydew, a sugary substance excreted by aphids, in return [

74]. This form of animal husbandry demonstrates ants’ ability to manipulate other insects for their benefit, highlighting their ecological impact on diverse ecosystems.

- 4.

Ecosystem Services Provided by Ants

Ants play a crucial role in pest control by preying on various insect species, regulating populations and contributing to overall ecosystem balance [

75]. Their activities in soil aeration, seed dispersal, and nutrient cycling further contribute to the health and productivity of agricultural landscapes [

76].

- 5.

Applications in Sustainable Agriculture

Sustainable farming methods can benefit from an understanding of ant behavior and ecological responsibilities. For instance, encouraging ant-friendly habitats may improve natural pest management and lessen the need for chemical pesticides [

77]. The incorporation of knowledge about ants into agroecological systems is consistent with initiatives to create resilient and ecologically friendly farming methods.

In summary, examining the complexities of ant behavior in relation to agriculture and animal husbandry reveals both the possibility for creative uses in sustainable practices as well as their intriguing ecological responsibilities. There may be fresh chances to improve ecological and agricultural sustainability as scientists work to understand the intricacies of ant behavior.

3.1.5. Intelligence and Learning

Ants, belonging to the family Formicidae, are renowned for their highly organized and complex social structures. Beyond their collective behaviors, recent research has shed light on the intelligence and learning capabilities exhibited by ants, which hold significant implications for various fields, including ecology, neuroscience, and, intriguingly, forensic science.

- 1.

Ant Intelligence: A Collective Endeavor

Ants are social insects with a level of social organization that is higher than that of individual ants. They live in colonies. Ant colonies’ intelligence is frequently ascribed to the interactions and collective behavior of individual ants [

78]. With complex communication networks and a division of labor among several ant castes, including workers, soldiers, and queens, ant colonies function as superorganisms.

- 2.

Learning in Ants: Adaptability and Memory

Ants have a remarkable capacity for environmental learning in addition to their ability to engage in complex social behaviors. Ants can navigate complex surroundings, acquire and store spatial information, and modify their behavior based on experience, according to research [

79]. For activities like foraging, where ants must maximize food gathering and maneuver effectively across their environment, this learning ability is essential.

- 3.

Communication and Information Transfer

Ants communicate primarily through chemical signals known as pheromones. This sophisticated chemical communication system enables ants to convey information about food sources, danger, and even mark paths for other ants to follow. The ability to transmit and interpret complex information through pheromones enhances their collective decision-making processes [

80].

- 4.

Problem-Solving Abilities

Studies have demonstrated that ants display problem-solving skills in various contexts. For instance, ants can navigate mazes, find the most efficient routes to food sources, and even adapt their foraging strategies based on changing environmental conditions [

81]. The problem-solving abilities of ants highlight their cognitive flexibility and capacity to respond to novel challenges.

- 5.

Application in Forensic Science

Forensic science will be greatly impacted by the growing comprehension of ants’ intellect and capacity for learning. Ants can be used to gather evidence at crime scenes because of their innate abilities to find and move objects. They are also useful instruments for determining the time of death in forensic investigations due to their propensity for decomposition processes.

To sum up, the overview of ant behavior and abilities shows a degree of learning and intelligence that surpasses the intellect of a single ant to the collective intelligence of the entire colony. This knowledge has promising applications in forensic science, supporting the development of forensic investigation techniques and creating new opportunities for creative evidence collection strategies.

This overview highlights the intricate social structures, remarkable foraging strategies, and problem-solving capabilities of ants. Understanding these behaviors is crucial not only for ecological studies but also for unlocking their potential in various applications, such as in forensic science, agriculture, and robotics.

Ants’ complex habits and abilities must be understood in order to fully utilize their potential in forensic science, where their innate instincts can be used to gather evidence effectively in a variety of settings.

3.2. Identification of Specific ant Species Suitable for Forensic Evidence Collection

Forensic entomology, the application of insect biology to criminal investigations, has witnessed a growing interest in utilizing ants as forensic evidence collectors. Ants’ complex habits and abilities must be understood in order to fully utilize their potential in forensic science, where their innate instincts can be used to gather evidence effectively in a variety of settings.

3.2.1. Pheidole megacephala (Big-Headed Ant)

The use of insect biology in legal investigations, or forensic entomology, has become well-known for its assistance in crime scene investigations and postmortem interval estimation. Ants have become potential contributors to forensic science because of their natural capacity to find and interact with different kinds of evidence. The identification and usefulness of a particular ant species, Pheidole megacephala, also referred to as the Big-Headed Ant in

Figure 2, for the collecting of forensic evidence are the main topics of this section.

-

A.

Overview of Pheidole megacephala:

The ant species Pheidole megacephala is found all over the world and is distinguished by its huge workers’ heads, which are excessively large in relation to their body size. Due to its polymorphism, which includes minor and major worker castes, this species is adaptable to a variety of duties, such as nest guarding and foraging [

82]. Their potential use in forensic investigations is influenced by their versatility and capacity to flourish in a variety of settings.

-

B.

Suitability for Forensic Evidence Collection:

- 1.

1. Foraging Behavior:

Pheidole megacephala is an efficient forager with a keen sense of smell, allowing them to locate and retrieve various items from their surroundings. This foraging behavior makes them well-suited for discovering and collecting forensic evidence at crime scenes [

83].

- 2.

Transportation Abilities:

The Big-Headed Ant is incredibly strong and capable of carrying loads that are several times their own weight. For carrying tiny objects to their nests, like hair, bone fragments, or other trace evidence, this ability offers advantages [

84].

- 3.

Nesting Habits:

Pheidole megacephala have a variety of nesting habitats since they can build their nests in soil, leaf litter, or decomposing wood. Because of their versatility, they can be found at diverse crime scenes, which could make them useful for gathering evidence in a variety of contexts [

85].

- 4.

Broad Geographic Distribution:

Pheidole megacephala is found in tropical and subtropical regions globally, making it a candidate for forensic investigations in a wide range of climates and ecosystems [

86]. This broad distribution enhances its applicability in diverse forensic contexts.

-

C.

Case Studies:

The use of Pheidole megacephala in forensic investigations has been recorded in a number of case studies. For instance, studies conducted by Ahmad A. and Omar B. shown how this ant species may be used to find and gather bone remains, demonstrating its potential as a useful instrument for crime scene investigation [

87].

The Big-Headed Ant, Pheidole megacephala, is a viable choice for gathering forensic evidence because of its global distribution, feeding patterns, nesting behaviors, and transportation capabilities. By giving law enforcement and forensic experts more resources for efficient crime scene investigations, the identification of certain ant species with these characteristics advances the growing area of forensic entomology.

3.2.2. Formica spp. (Wood Ants)

In order to assist with legal investigations, forensic entomology uses the study of insects and other arthropods, especially when determining the postmortem period and locating human remains. As seen in

Figure 3, several ant species, such Formica spp., have demonstrated promise in their capacity to effectively gather and process forensic evidence among the wide variety of insects used in forensic science.

A. Overview and Taxonomy

Formica spp., commonly known as wood ants, belong to the Formicidae family. These ants are prevalent in various ecosystems, including forests and woodlands. With their distinct morphology and behavior, wood ants have attracted the attention of forensic researchers seeking alternative methods for evidence collection [

88].

B. Behavioral Characteristics Relevant to Forensic Evidence Collection

Wood ants are appropriate for forensic applications due to a number of their habits. Their capacity to move objects, effective pheromone transmission, and keen foraging instincts all add to their potential as forensic evidence collectors [

89]. At crime scenes, these actions are essential for finding and moving evidence.

C. Case Studies and Research Findings

The usefulness of Formica spp. in forensic scenarios has been demonstrated in a number of investigations. Wood ants were found to quickly find and move small objects during decomposition trials in a study by Eubanks et al. The importance of wood ants in helping forensic investigators locate dispersed remains effectively was highlighted in the study [

90].

D. Advantages of Formica spp. in Forensic Evidence Collection

Wood ants exhibit rapid and organized foraging behavior, enhancing the speed of evidence discovery [

90]. Wood ants thrive in diverse environmental conditions, making them adaptable to various forensic contexts [

91]. Unlike traditional evidence collection methods, the use of wood ants is minimally invasive, preserving potential forensic evidence [

92].

E. Considerations and Challenges

Even though Formica spp. exhibit promise, there are factors and difficulties to take into account:

Ethical Problems such as careful consideration must be given to the moral ramifications of employing living organisms in forensic investigations [

89]. Environmental factors such as geographical location, climate, and ecological features can all affect how effective wood ants are [

91].

F. Future Directions and Research Needs

Future studies should concentrate on examining species-specific behavior to determine the most effective forensic evidence collectors in order to further expand the relevance of Formica spp. in forensic science. The creation of organized training courses for forensic experts is also necessary in order to use wood ants in crime scene investigations. Formica spp., especially wood ants, offer a novel and exciting way to gather forensic evidence. They are useful friends in crime scene investigations because of their unique characteristics, which include quick and well-organized foraging and their capacity to adapt to a variety of environmental situations. This strategy provides an unconventional yet efficient way to find evidence, enhancing and maybe enhancing current forensic procedures.

3.2.3. Solenopsis invicta (Red Imported Fire Ant)

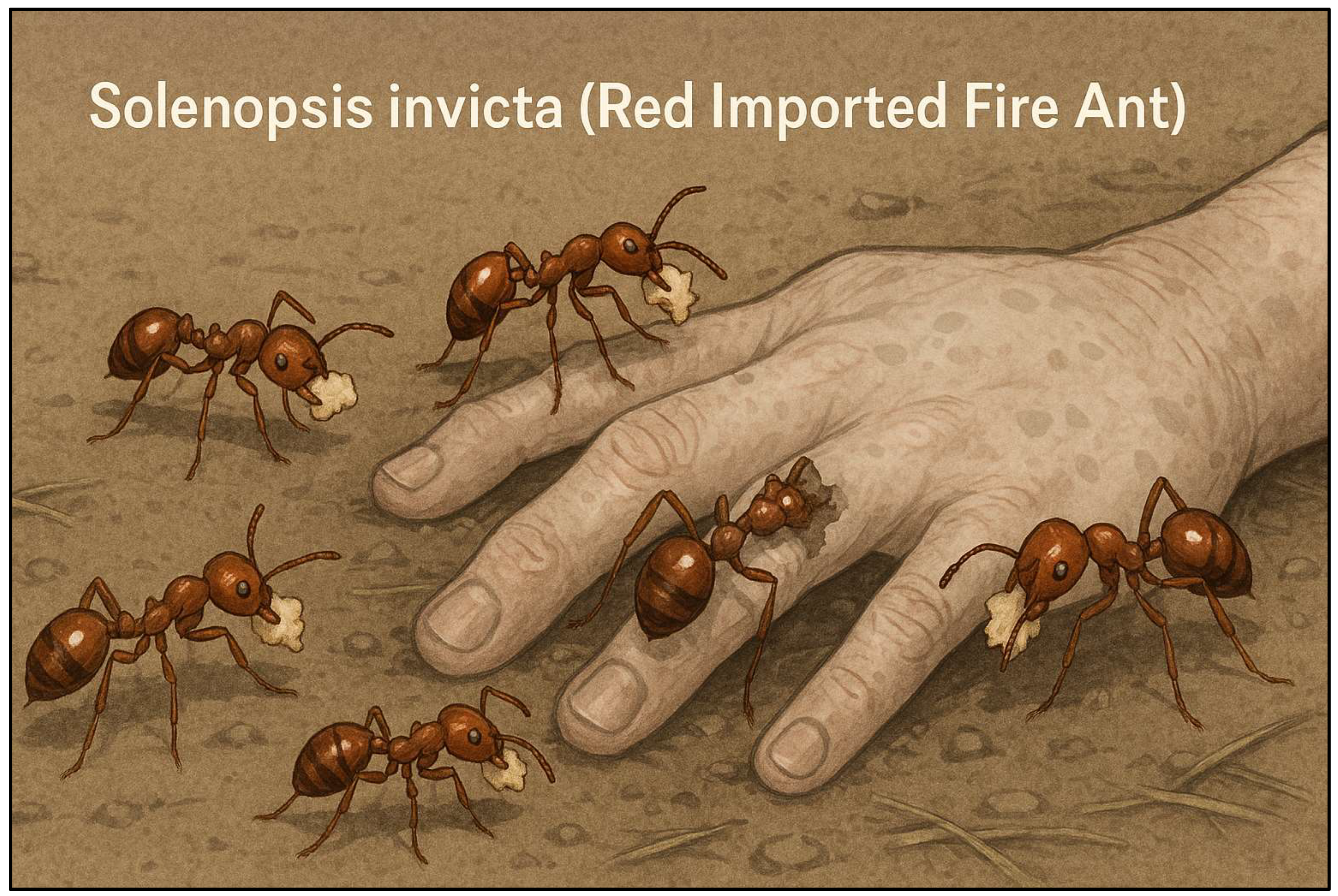

There is growing interest in using ants to gather evidence in forensic entomology, which applies insect biology to legal investigations. Because of its exceptional traits and behaviors, Solenopsis invicta, also referred to as the Red Imported Fire Ant (RIFA), stands out among the many ant species as a possible contender. As seen in

Figure 4, this section explores the discovery of Solenopsis invicta as a species that is especially well-suited for gathering forensic evidence.

A. Taxonomy and Distribution

Solenopsis invicta belongs to the Formicidae family and is recognized for its reddish-brown coloration and aggressive nature. Native to South America, this ant species has spread globally, with established colonies in various regions, including the United States, China, Australia, and Europe. Research has highlighted its adaptability to diverse environments, making it a ubiquitous presence in both urban and rural settings [

93].

B. Aggressive Behavior and Colony Structure

Solenopsis invicta’s aggressive and territorial behavior is one of the main characteristics that make it appropriate for gathering forensic evidence. When disturbed, worker ants react quickly and collectively, initiating mass attacks on alleged intruders. RIFA colonies are noted for their strong nest defense. At crime scenes, this protective response might be used to find and gather evidence [

94]. Furthermore, in forensic applications, Solenopsis invicta colony structure is essential. A large number of worker ants, several queens, and a vast network of tunnels facilitate effective material transportation and foraging, allowing for a quick and well-coordinated attempt to collect forensic evidence [

95].

C. Detection of Decomposing Tissue

Solenopsis invicta has demonstrated a remarkable ability to detect and respond to decomposing tissue. Research has shown that RIFA can locate and gather around cadavers, accelerating the decomposition process. This behavior can be harnessed for forensic purposes, aiding in the identification of crime scenes and estimating the postmortem interval [

96].

D. Challenges and Considerations

Although Solenopsis invicta offers special benefits for gathering forensic evidence, there are drawbacks and moral issues that need to be taken into account. Because of RIFA’s aggressive character, investigators may be at risk, so cautious preparation and safety precautions are required. Furthermore, while evaluating results, it is important to take into account how environmental conditions affect ant behavior [

97].

The Red Imported Fire Ant, Solenopsis invicta, is a viable choice for gathering forensic evidence because of its aggressive nature, colony structure, and capacity to identify decaying tissue. But using this species in forensic investigations necessitates carefully weighing the ethical ramifications and probable difficulties. It will be easier to successfully include Solenopsis invicta into forensic entomology procedures if more research is done on its ecology and behavior.

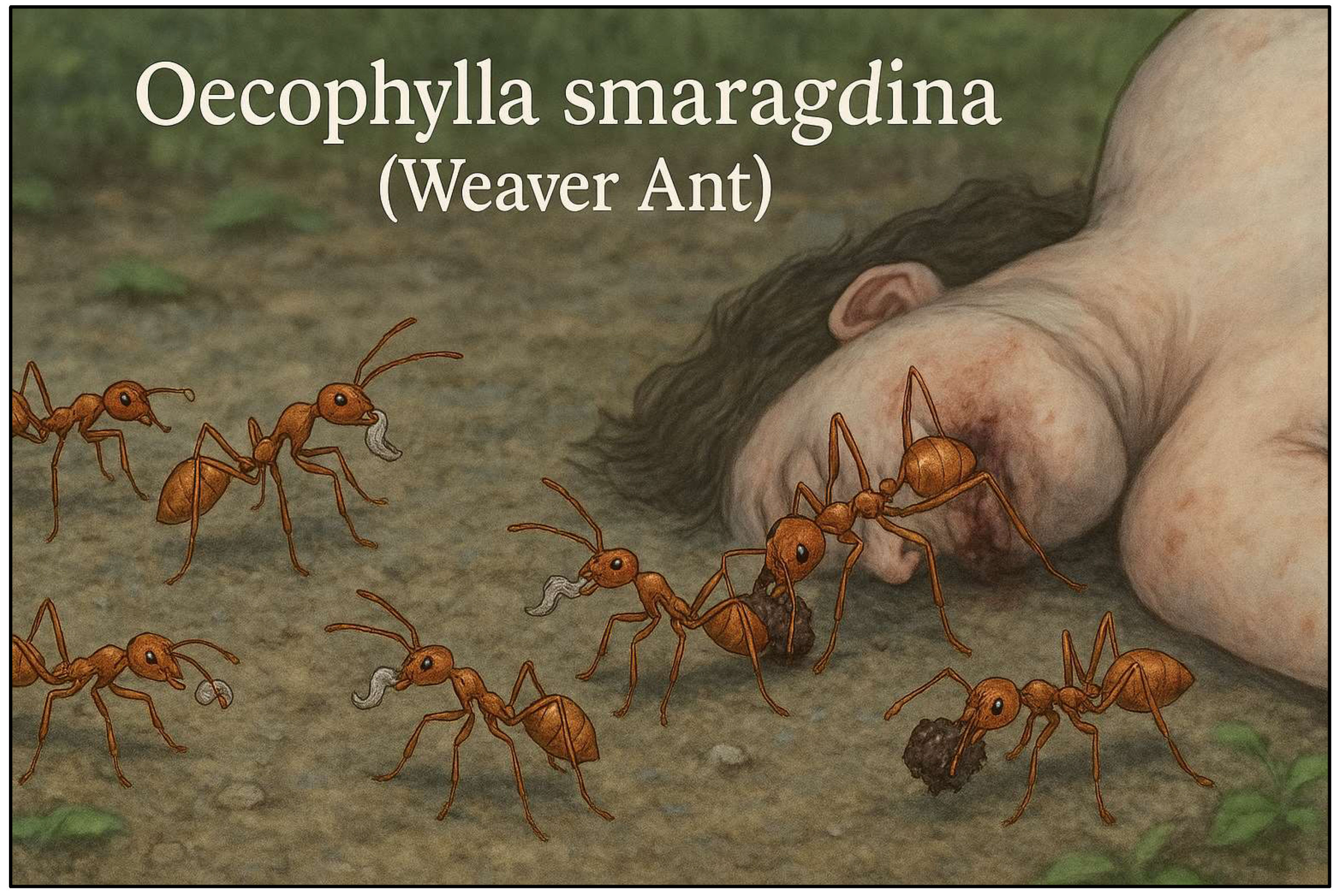

3.2.4. Oecophylla smaragdina (Weaver Ant)

Unconventional techniques for gathering evidence have advanced in forensic entomology, the study of insects in legal contexts. Using particular ant species to support forensic investigations is one such creative strategy. As illustrated in

Figure 5, this section focuses on the identification and usefulness of Oecophylla smaragdina, also referred to as the Weaver Ant, for the collection of forensic evidence.

A. Overview of Weaver Ants (Oecophylla smaragdina):

Weaver Ants, or Oecophylla smaragdina, are members of the Formicidae family and are distinguished by their distinct traits and activities [

98]. Native to tropical and subtropical locations, these ants flourish in a variety of settings, including as urban areas and woods [

99]. In terms of appearance, Weaver Ants are identified by their greenish hue and very hostile conduct [

98]. Their capacity to weave intricate nests out of leaves using silk created by their larvae is one of their most amazing characteristics [

98].

B. Weaver Ants in Forensic Science:

Weaver Ants exhibit unique behavioral traits that offer promising applications in forensic investigations. Their habit of creating nests is one of their most distinctive characteristics. As natural traps for forensic material, these ants build elaborate nests that can be put strategically close to crime scenes to help with the passive collecting of trace evidence [

100]. Weaver Ants are renowned for their effective object-carrying abilities in addition to their building prowess. Their ability to move objects with exceptional power and coordination has been shown in studies, and this ability can be used to successfully transfer small pieces of evidence to their nests for subsequent retrieval and examination [

101].

C. Weaver Ants and Decomposition:

Weaver ants play a significant role in the natural decomposition of organic matter, contributing to the breakdown and recycling of biological materials in their environment [

102]. They can affect the rate at which organic matter breaks down at a decomposition site, which can impact the overall ecological dynamics that are pertinent to forensic investigations. In forensic settings, knowledge of weaver ants’ interactions with decaying bodies is useful for calculating the post-mortem delay [

102]. By serving as biological markers of particular decomposition phases, these ants can help forensic specialists determine the exact time of death.

D. Case Studies:

Several case studies illustrate the successful implementation of Weaver Ants in forensic investigations, particularly in the transportation of trace evidence and their ability to operate effectively across diverse environmental conditions [

103]. These ants have shown a great deal of promise in identifying and transporting tiny forensic items, which will increase the effectiveness of evidence gathering. Weaver ant use in these situations is not without difficulties, though. To guarantee appropriate and efficient use, significant issues pertaining to the environment and ethics must be addressed [

103]. To further understand these problems and create plans for reducing any potential negative effects, research must continue.

Because of their unique behavioral characteristics and ecological responsibilities, weaver ants, in particular, Oecophylla smaragdina have shown great promise as agents in the collecting of forensic evidence. They make significant contributions to forensic entomology because of their exceptional skills in nest construction, effective communication, and group item transportation. These actions create new opportunities for minimally invasive forensic procedures in addition to facilitating the organic flow of possible evidence. However, further research is need to fully utilize weaver ants’ potential. The improvement of current methods and the resolution of problems pertaining to their forensic use should be the main goals of future research. Furthermore, multidisciplinary cooperation between entomologists, forensic scientists, and legal specialists will be necessary for the successful integration of weaver ants into conventional forensic procedures in order to guarantee the findings’ scientific validity and legal admissibility.

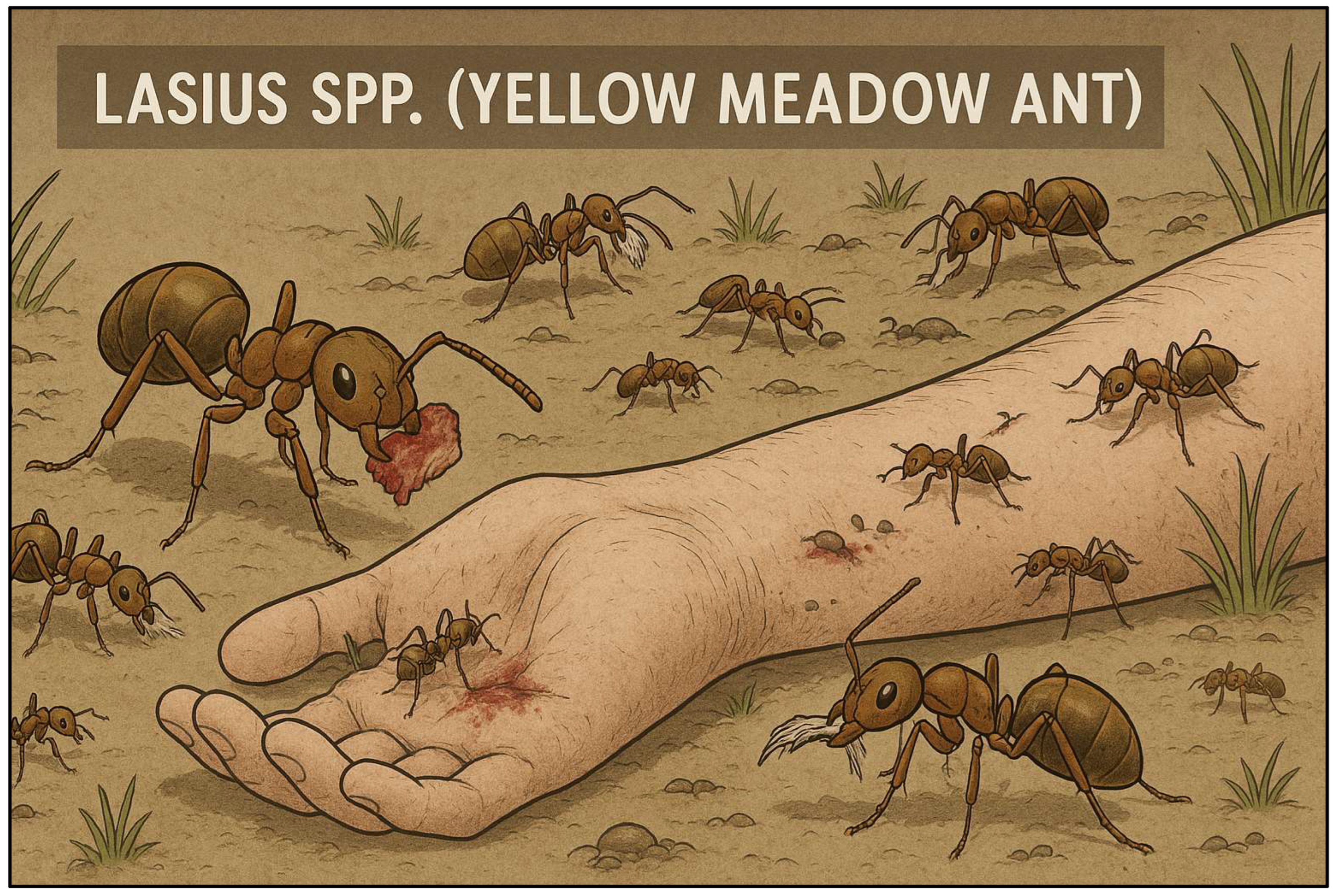

3.2.5. Lasius spp. (Yellow Meadow Ant)

Insects are essential to the collection of evidence in forensic entomology, and ants have drawn interest recently due to their extraordinary skills. Lasius spp., also referred to as the Yellow Meadow Ant in

Figure 6, is a noteworthy ant species that has demonstrated potential in forensic investigations.

A. Characteristics of Lasius spp.:

Lasius spp. belongs to the Formicidae family and is prevalent in various ecosystems, particularly meadows and grasslands. These ants exhibit social behavior, living in colonies with a well-defined caste system, including workers, queens, and males [

104].

B. Foraging Behavior and Nesting Habits:

The effectiveness of Lasius species’ foraging activity is noteworthy. These ants can be used for forensic purposes because they have been seen scouting vast distances for food supplies and because their nests are frequently located in soil [

105].

C. Use in Forensic Evidence Collection:

Lasius spp. have been shown in studies to be useful for finding and moving small items, such as forensic evidence [

106]. Because of their innate foraging habits, they may gather hair, fibers, or even human tissues for use in forensic investigations.

D. Species Identification:

Identification of Lasius spp. involves morphological characteristics such as body size, coloration, and the presence of specific features on the ant’s body. Additionally, genetic analysis, including DNA barcoding, has been employed for accurate species identification [

107].

E. Advantages of Lasius spp. in Forensic Science:

Lasius spp. are valued in forensic settings where meticulous evidence collecting is essential since they are known to be effective foragers that can explore wide distances in quest of resources [

105]. Their exceptional environmental flexibility further increases their usefulness in a variety of forensic circumstances, enabling them to operate efficiently in both urban and rural areas. Furthermore, Lasius species’ natural activity makes it easier to gather evidence without causing harm to sensitive samples while maintaining the integrity of the crime scene.

F. Case Studies:

Several case studies have highlighted the potential of Lasius spp. in evidence transmission. For example, a study by De Melo Rodovalho C et al. (2007) documented the successful use of Lasius spp. in locating and transporting trace evidence in a simulated case scenario [

108].

G. Challenges and Considerations:

While Lasius spp. shows promise, challenges such as environmental variables, seasonality, and potential disruptions in their natural behavior should be considered [

109]. Additionally, ethical considerations regarding the use of live organisms in forensic investigations warrant careful attention.

The Yellow Meadow Ant, Lasius spp., is an asset for gathering forensic evidence because of its versatility and effective feeding habits. Finding the right ant species for forensic uses creates new opportunities for study and application in the developing area of forensic entomology.

An in-depth knowledge of the behavioral characteristics, feeding habits, and environmental adaptability of the ant species is necessary when selecting one for the collecting of forensic evidence. The chosen ant species should improve the effectiveness of evidence recovery and detection in forensic investigations while also complementing the particular needs of the crime scene. The selection criteria for the best ant partners in forensic entomology are being improved and new opportunities are being revealed by ongoing study in this area.

3.3. Exploration of Ants’ Natural Instincts in Finding and Transporting Objects

Ants are gregarious, well-organized insects that come in many different varieties and have amazing instincts and habits. When thinking about their use in forensic science, especially in the location and conveyance of items pertinent to criminal investigations, it is essential to comprehend their innate inclinations. This section explores the main features of ants’ innate tendencies that enable them to gather forensic evidence efficiently.

3.3.1. Communication and Coordination

Ants, as social insects, have evolved highly sophisticated communication and coordination systems that enable them to efficiently find and transport objects within their environment. Understanding these natural instincts is crucial when considering their potential application in forensic science.

A. Chemical Communication:

Ants mostly use chemical messages called pheromones to communicate. These chemical cues can be used to indicate danger or to designate pathways to food sources, among other things. Ants use a wide variety of pheromones for communication, according to research [

110]. A key component of their innate behavior is the capacity to create and follow scent trails.

B. Trail Following:

Ants are adept at following trails laid down by other colony members. When an ant discovers a food source or a potential object of interest, it leaves a pheromone trail leading back to the nest. Other ants then follow this trail to locate and retrieve the object [

111]. This trail-following behavior is crucial for the efficient transportation of resources within the colony.

C. Coordination in Object Transport:

Ants have amazing coordination when transporting objects. According to studies, ants exhibit a degree of flexibility and cooperation by modifying their carrying behavior in response to the weight and size of the load [

112]. For the items to be successfully transported back to the colony, this coordination is necessary.

D. Division of Labor:

Ant colonies exhibit a high degree of division of labor, with distinct worker castes specializing in different tasks. Foraging ants, responsible for finding and collecting food and objects, demonstrate a remarkable ability to efficiently communicate information about the location and nature of resources [

113].

E. Communication in Nest Construction:

Ants demonstrate coordinated behavior in nest construction in addition to foraging. Ants collaborate to construct intricate nest structures, and efficient labor and resource allocation depend on communication [

114]. The sophisticated coordination and communication systems found in ant colonies are reflected in this team effort.

Gaining knowledge of these ants’ innate tendencies can help with their possible application in the gathering of forensic evidence. Researchers can investigate methods to educate ants for certain activities, such finding and moving forensic evidence in various locations, by utilizing their communication and coordination skills.

3.3.2. Foraging Behavior

As innate foragers, ants are always looking for food and resources in their environment. Individual scouting and group decision-making within the colony combine to produce this foraging activity. Ants use methodical search strategies to cover a lot of ground when looking for resources. In forensic investigations, this habit can be used to find scattered evidence or cover large crime scenes. As gregarious insects, ants’ exceptional hunting habits have drawn interest from a variety of scientific fields, including forensic science. Leveraging their abilities in forensic evidence collecting requires an understanding of the finer points of their innate instincts for locating and moving objects.

A. Foraging Patterns and Trail Formation

Ants are known for their highly organized foraging patterns, which involve the establishment of pheromone trails. Pheromones are chemical signals emitted by ants to communicate with their colony members. In the context of foraging, ants deposit pheromones along the path they travel, creating a trail that guides other ants to the source of food or, in the case of forensic applications, to relevant evidence. This behavior is well-documented in literature [

115].

B. Ant Species Variability in Foraging Behavior

The foraging habits of different ant species vary. While some species are generalists, others are quite specialized. In forensic applications, the selection of ant species is essential since it affects how well evidence is detected and transported. For example, the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) can traverse huge areas because of its extensive foraging networks [

116].

C. Recruitment Mechanisms

Ants use complex recruitment strategies to increase the effectiveness of their foraging. Ants notify other members of their colony when they find a food source or, in the context of forensics, a possible piece of evidence. Pheromones, vibrations, and tactile contacts aid in this recruitment process, which enables quick labor mobilization to recover and move the found item [

117].

D. Cooperative Transport of Objects

Ants exhibit cooperative transport behavior, in which several people work together to move objects that are significantly bigger than themselves. This tendency is especially helpful in forensic situations when the weight and quantity of the evidence can vary. Ants have been shown to efficiently move burdens up to many times their body weight when they work together [

118].

E. Adaptability to Environmental Challenges

Ants’ foraging behavior demonstrates a remarkable degree of adaptability, which enables them to overcome a variety of environmental obstacles. Ants exhibit a remarkable ability to alter their foraging techniques, whether it is locating things in difficult settings, overcoming obstacles, or adjusting to changes in terrain [

119].

F. Application in Forensic Evidence Collection

An application of ants in the gathering of forensic evidence is made possible by an understanding of their foraging behavior. Researchers and forensic specialists can create methods to teach ants to find and move particular kinds of evidence by taking advantage of their innate inclinations. This provides a non-invasive and effective method of recovering evidence in a variety of settings.

In conclusion, investigating ants’ innate abilities to locate and move objects—especially their feeding habits—opens up new avenues for creative forensic applications. The development of forensic science can be greatly aided by utilizing the combined knowledge and skills of ant colonies.

3.3.3. Trail Following

Ants create pheromone trails to direct other members of the colony when they find a food source or a valuable item. For effective resource exploitation, this trail-following behavior is essential. Ants can be trained to follow particular odors linked to evidence in forensic applications, guiding investigators straight to the source. As social insects, ants have a complex navigational and communication system that has fascinated both forensic scientists and researchers. Trail following is a noteworthy feature of animal behavior that is important to their foraging efforts and has important ramifications for the gathering of forensic evidence.

A. Ant Communication and Trail Following Mechanism

Pheromones are chemical signals that ants use to mark trails and communicate with one another. As a means of chemical communication inside the colony, ants release chemical molecules called pheromones, which are picked up by their antennae [

120]. An amazing example of this communication system is trail following, in which ants leave pheromones along a path to help other members of the colony find a food source or an object they have found.

B. Formation of Trails in Response to Stimuli

Ants actively engage in trail following when they encounter stimuli, such as a potential food source or a foreign object. This behavior involves a cooperative effort, with individual ants depositing pheromones along the path as they move towards the target. The intensity of the pheromone trail increases with the number of ants using it, creating a positive feedback loop that reinforces the chosen route [

121].

C. Implications for Forensic Evidence Collection

Ants’ capacity for trail-following has important ramifications for the identification and recovery of evidence in forensic research. Researchers may be able to direct ants to certain areas of interest by employing naturally occurring odors linked to forensic evidence or by carefully positioning alluring scents [

122]. This method provides a non-invasive and effective way to locate evidence by utilizing the ants’ innate trail-following capabilities.

D. Practical Applications in Forensic Investigations

The usefulness of ant trail following in trace substance detection has been investigated in studies. Chalissery et al.’s research showed how effective it is to use ant trails to feel and follow one another’s trail pheromones. Ants were able to find and follow smell trails that went to simulated places in the experiment, suggesting that this technique could be used to find hidden trace items [

123]. According to this study, ants may be used to find forensic evidence.

E. Challenges and Considerations

Although ants’ trail-following behavior has potential for forensic uses, there are obstacles to overcome. The success of trail following tests can be affected by variables including the ant species used, the presence of competing odors, and weather circumstances [

124]. To maximize the efficiency of ant-assisted evidence collecting, researchers need to carefully take these factors into account.

F. Future Directions and Research Opportunities

There are many prospects for more research in the developing discipline of forensic science’s investigation of ant trail tracking. Future research might concentrate on improving techniques, determining which ant species are best suited for various settings, and creating useful recommendations for forensic investigators looking to use this cutting-edge strategy.

In conclusion, ants’ innate instincts, especially their tendency to follow trails offer a special way to gather forensic evidence. Finding and moving items of forensic relevance can be done more effectively and non-invasively thanks to this investigation of their communication mechanisms.

3.3.4. Object Transport

Ants are incredibly strong and versatile when it comes to returning items to the colony. Some animals are remarkably adept at navigating a variety of terrains and can carry burdens that are many times their body weight.

In forensic situations where evidence must be moved for additional study without contamination, this innate transferring sense is helpful.

As social insects, ants display highly specialized and evolved behaviors that go beyond their usual foraging habits. Their capacity to locate and move objects is one fascinating feature of their behavior that has generated attention in the study of forensics. Ants’ potential use as forensic evidence collectors can be clarified by comprehending the subtleties of their innate inclinations in item transfer.

A. Ant Navigation and Foraging Behavior:

Ants are known for their remarkable navigation skills and complex foraging strategies. A seminal study by Wehner et al. demonstrated that ants utilize both visual and olfactory cues for navigation. The ability to follow pheromone trails left by other ants enables them to efficiently locate and transport food resources [

125]. This innate navigational capability forms the basis for their potential role in object transport in forensic settings.

B. Object Transport in Ant Colonies:

Ant colonies function as extremely well-organized societies, with each individual assigned a specific task. Ants frequently work together to move objects of interest, demonstrating that object transport is frequently a team effort. According to Ron JE et al., worker ants use their bodies to carry things that are far heavier and larger than those of individual ants. Ant colonies are ideal for activities involving object transport because of their cooperation and division of labor [

126].

C. Chemical Communication and Pheromone Trails:

Ant colonies’ communication system is mostly dependent on chemical cues. To convey information about food supplies, danger, and nest locations, ants emit pheromones. Once formed, pheromone trails can direct ants to certain areas and items [

127]. Organizing the movement of items throughout the colony depends heavily on this chemical exchange.

D. Forensic Applications:

Forensic science is directly impacted by the investigation of ants’ innate instincts in item movement. Ants can be trained to identify and carry particular objects of forensic relevance, such hair, bloodstains, or small objects, in the context of crime scene investigations. Ant-assisted object transport has the potential to outperform conventional techniques in terms of precision and efficiency, particularly in demanding situations.

E. Challenges and Considerations:

There are limitations to overcome even if using ants for object movement offers exciting possibilities. Careful consideration must be given to environmental conditions, ant species specialization, and ethical issues. Optimizing ant-assisted object movement conditions and developing standards for appropriate use in forensic investigations should be the main goals of research. A new area of forensic research is being opened by investigating how ants naturally locate and move objects. Ants have the ability to completely transform the field of forensic evidence collection by utilizing their highly developed navigation, cooperative behavior, and chemical communication. To fully realize the potential of these amazing insects, entomologists and forensic scientists must continue their studies and work together.

3.3.5. Problem-Solving Abilities

Colonies of ants exhibit group problem-solving skills. Ants are able to modify their foraging habits and discover alternate pathways in the face of difficulties. This flexibility is useful in forensic investigations, particularly in dynamic settings where barriers or terrain changes could arise. Researchers from a variety of disciplines, including entomology, ecology, and neuroscience, have been fascinated by ants’ exceptional problem-solving skills as social insects. Investigating their innate abilities to locate and move objects has important ramifications for forensic science, especially when it comes to gathering evidence. The ability of ants to solve problems and how this helps them find and move forensic evidence is covered in detail in this part of the article.

A. Collective Intelligence and Problem-Solving:

Ant colonies are extremely well-organized communities whose members cooperate to achieve shared objectives. The idea of collective intelligence is one of the main factors influencing their capacity for problem-solving. Ants collaborate to process and exchange information, which enables the colony to efficiently address environmental difficulties [

128].

B. Trail Following and Pheromone Communication:

Ants are known for their adept use of pheromones to communicate with each other. When an ant discovers a food source or an object of interest, it leaves a trail of pheromones to guide other ants to the location. This process, known as trail following, is a critical aspect of their problem-solving behavior [

129].

C. Adaptive Foraging Strategies:

Ants can modify their foraging tactics according to the task at hand and the surrounding environment. They demonstrate a great degree of flexibility in problem-solving by being able to dynamically optimize their routes, allocate workers, and modify their efforts to overcome barriers [

130].

D. Exploration and Exploitation:

Ants employ a balance between exploration and exploitation strategies when searching for resources. The colony’s chances of successfully locating and moving items, including forensic evidence, are increased by this adaptive behavior, which also guarantees effective resource use [

131].

E. Swarm Intelligence:

Ant behavior served as the inspiration for the idea of swarm intelligence, which describes the collective behavior of dispersed, self-organizing systems. Ants are good problem solvers in a variety of situations because they effectively organize themselves to handle difficult tasks, exhibiting swarm intelligence [

132].

F. Application in Forensic Evidence Collection:

Understanding the problem-solving abilities of ants is crucial for leveraging their potential in forensic science. Ants’ innate capacity to navigate complex environments, adapt to challenges, and communicate effectively within a colony make them valuable assets in the search for and retrieval of forensic evidence [

133].

In summary, the investigation of ants’ innate abilities to locate and move objects and particularly their capacity for problem-solving, offers important new perspectives on their possible uses in forensic research. As forensic professionals continue to seek innovative methods for evidence collection, the collaboration with entomologists studying ant behavior opens new avenues for advancing the field.

3.3.6. Specialized Roles

Each caste in an ant colony has a distinct job to play. Unlike other castes like soldiers or queens, worker ants, who are in charge of foraging, display unique characteristics.

Optimizing the usage of ants for particular forensic evidence gathering tasks can be made easier with an understanding of these specialized responsibilities.

There has been curiosity in the possible use of ants in forensic science because of their exceptional natural sense for locating and moving items, as well as their well-known and cooperative social structures. This portion explores the specific functions of ants as well as the behavioral strategies that enable them to find and move objects of interest.

A. Division of Labor within Ant Colonies

Ant colonies are distinguished by a division of labor, in which members take on specialized responsibilities according to their physical characteristics, age, and the tasks needed to maintain the colony [

134]. An essential component of ant behavior is foraging, which entails some ant castes being entrusted with finding food sources. This function can be extended to the hunt for forensic evidence [

135].

B. Communication and Trail Following

Ants employ chemical communication through pheromones to convey information within the colony, facilitating efficient coordination during foraging activities [

136]. Pheromone trails laid by foraging ants not only guide their nestmates to food sources but could potentially be exploited for directing them towards forensic evidence [

137].

C. Specialized Foragers and Transporters

Certain ants in the foraging caste exhibit a high degree of task specialization by focusing on finding and recognizing particular resources [

134]. In ant species like Pheidole pallidula, there is a distinct separation between transporters that bring the food back to the nest and scout ants that find it [

138].

D. Adaptability to Environmental Conditions

Ant species are highly adaptable and have evolved to flourish in a variety of environmental situations, which is important for forensic investigations in a range of terrains [

139]. Ants’ aptitude at navigating intricate settings and overcoming barriers is very helpful when looking for evidence at difficult crime scenes [

140].

E. Time and Energy Efficiency

Ant colonies use shortest and most direct paths to get food in order to enhance energy efficiency during foraging [

141]. In forensic settings, where prompt and targeted evidence collecting is crucial for successful investigations, this time and energy savings may prove advantageous.

Exploring ants’ potential as forensic evidence collectors begins with an understanding of their particular jobs and instincts. Ants may provide a distinctive and effective method for finding and moving important bits of evidence in a range of forensic situations by utilizing their innate tendencies.

3.3.7. Nocturnal Foraging

Since many ant species are active at night, they can be used in low-light forensic investigations. They can supplement conventional daytime foraging techniques with their nighttime activities.

Because of their innate ability to find and move objects, particularly during nighttime foraging, ants—known for their intricate social structures and amazing behaviors—have grown in interest as forensic science subjects. By utilizing the special capacities of some ant species that exhibit increased nocturnal activity, this investigation illuminates possible uses in the gathering of forensic evidence.

A. Ant Behavior and Nocturnal Foraging

Ants are social insects that display a variety of behaviors essential to their survival and the smooth operation of their colonies. In particular, a number of ant species exhibit nocturnal foraging, in which workers leave their nests at night to look for food and resources. Ants exhibit well-coordinated foraging activity and use pheromone trails for navigation and communication, according to Maschwitz et al. Ants can effectively acquire nutrients in the dark by foraging at night, which helps them avoid predators and harsh temperatures [

142].

B. Identification of Ant Species for Nocturnal Foraging

It is important to identify ants that exhibit nocturnal foraging because not all ant species do so. According to studies by Maschwitz et al. and Longino et al., some species like

Formicini and

Camponotini are more prone to engage in more nocturnal behaviors [

142,

143]. Forensic investigators looking to use ants for nighttime evidence collecting must be aware of the particular species that are nocturnal foragers.

C. Ants as Efficient Object Transporters

Ants’ innate abilities to locate and move items are well-established. Ants can find food sources, move objects back to their nests, and navigate through complex surroundings, according to research by Maschwitz et al. [

142]. Ants may carry a wide range of items, including tiny detritus and other things, thus their behavior is not just restricted to food. Ants’ capacity to carry tiny objects can be used in forensic settings to gather evidence, which could help recover trace materials or small objects that are important to criminal investigations.

D. Forensic Implications of Nocturnal Foraging

The integration of ants’ nocturnal foraging behavior into forensic science holds promise for improving evidence collection efficiency, especially in outdoor crime scenes. During nighttime operations, when conventional methods may be challenging, ants can continue their foraging activities, potentially discovering and transporting crucial pieces of evidence.

E. Challenges and Considerations

While the natural instincts of ants present exciting opportunities for forensic applications, it is essential to acknowledge challenges and limitations. Factors such as environmental conditions, ant species variability, and ethical considerations need to be carefully addressed in the development of protocols for utilizing ants in evidence collection [

143].

In summary, investigating how ants naturally locate and move objects, especially when foraging at night offers forensic scientists a new line of inquiry. Forensic investigators may improve their ability to gather evidence and aid in more successful and efficient crime scene examinations by comprehending and utilizing these characteristics. Gaining knowledge of these ants’ innate behaviors can help one better understand how they might be used in forensic research. Researchers can investigate novel approaches to using ants as effective and trustworthy forensic evidence collectors in a variety of crime scene situations by utilizing their communication, foraging, and transporting habits.

4. Ants and Decomposition

Ants play a significant role in the decomposition process, contributing to the breakdown of organic matter in various ecosystems. Their involvement in decomposition has important implications for forensic science, particularly in estimating the time of death in forensic investigations.

1. Ants’ Natural Instincts in Decomposition:

Beyond their well-known functions as foragers and scavengers, ants are social insects with a variety of intricate behaviors. They effectively decompose organic materials as part of their foraging and nesting activities because of their innate tendencies. Ants forage by searching for food sources, such as dead animals, which they then dismember and carry back to their nests for other colony members to eat and share [

144].