Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

27 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2.1. Intratumoral Heterogeneity Promotes the Metastatic Cascade

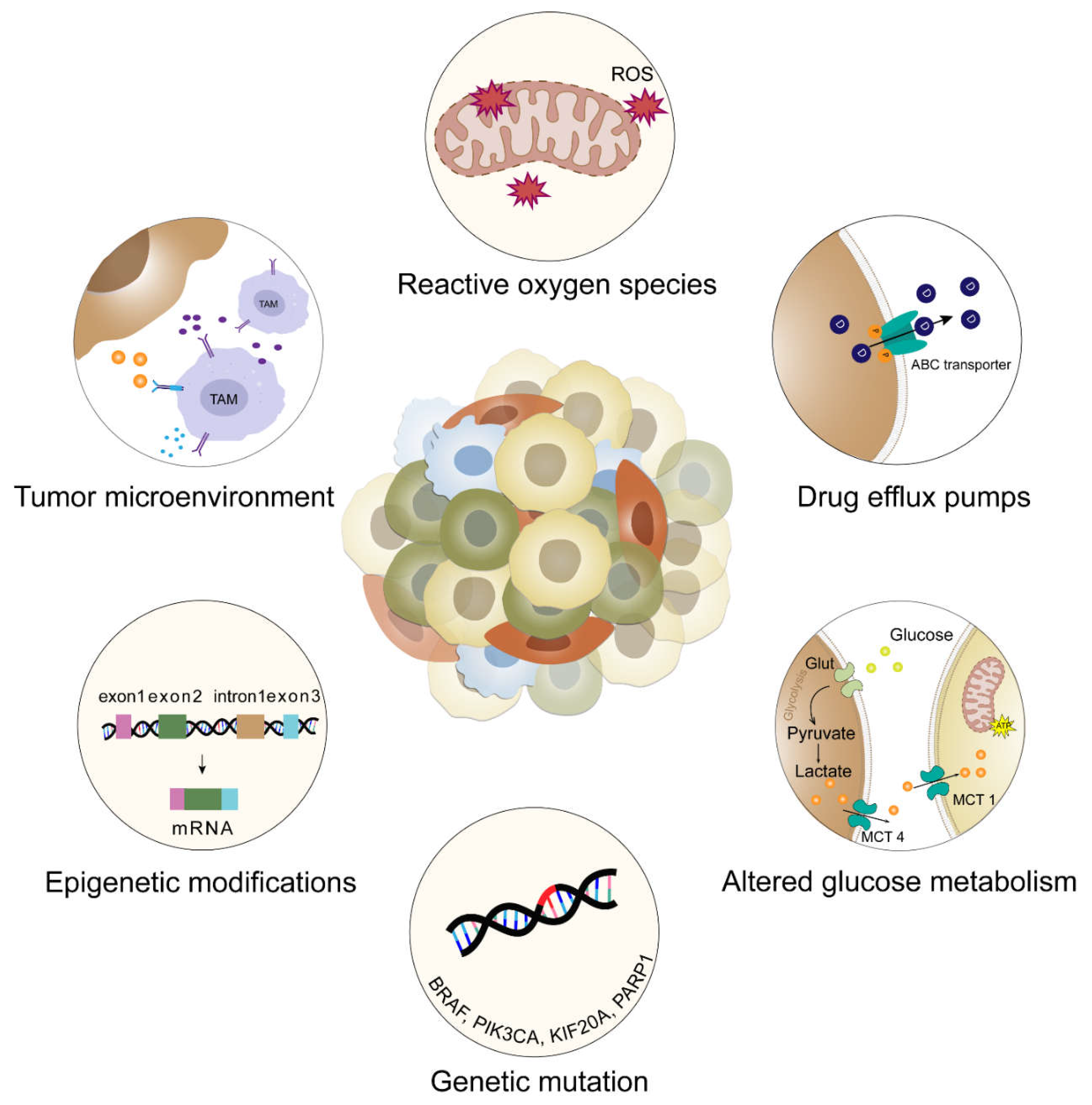

2.2. Implications of Intratumoral Heterogeneity in Therapeutic Resistance

2.3. The Role of Tumor Evolution in Driving Intratumoral Heterogeneity in Metastasis

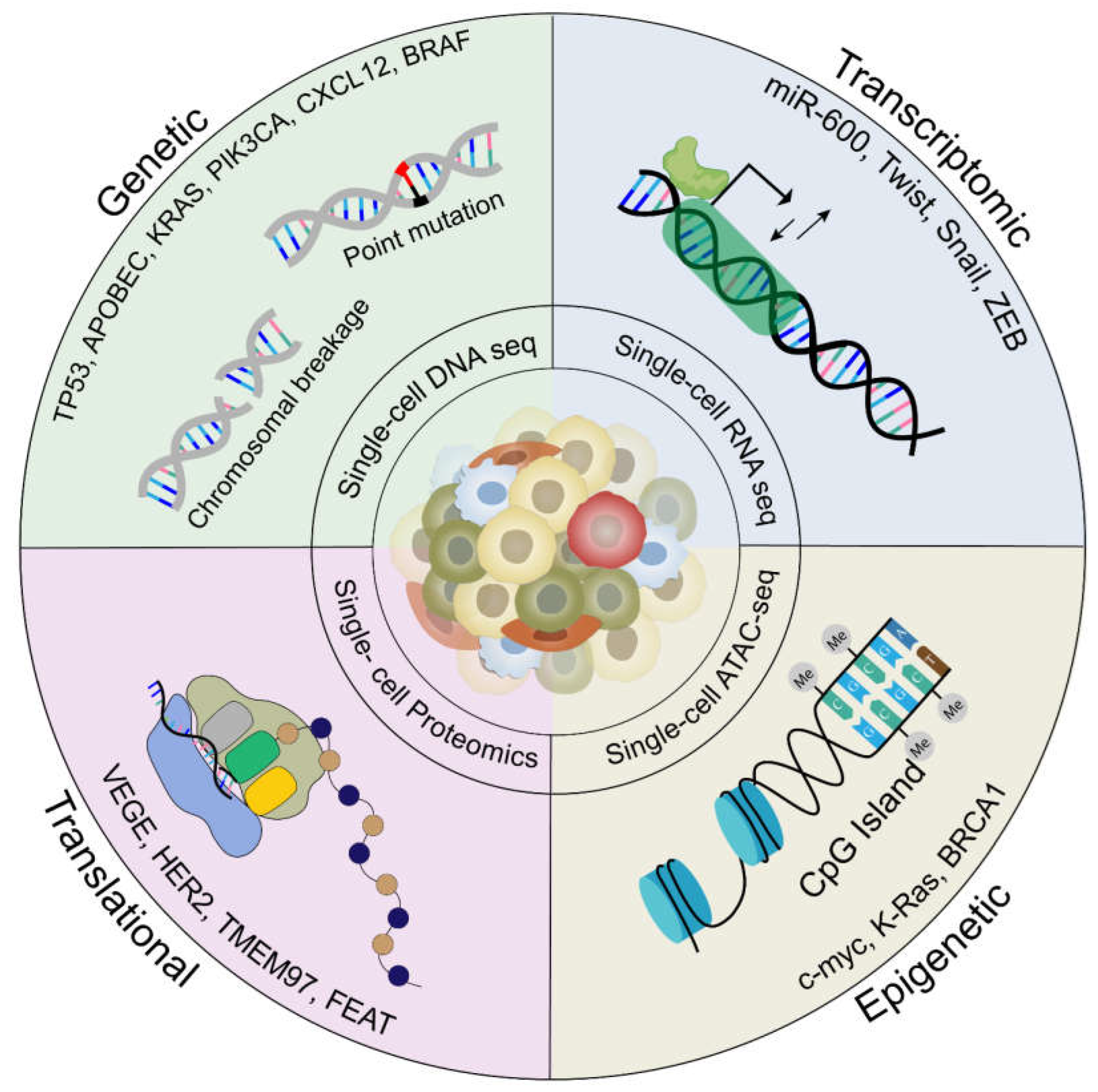

2.4. Current Technologies and Computational Models to Study Heterogeneity in Metastasis

| Name of the model | Hallmarks | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electroporation based Genetically engineered mice models (EPO GEMMs) | They are immunocompromised transgenic mice that spontaneously develop malignancies at the site of electroporation by introducing somatic mutations | Cannot accumulate as many somatic mutations as organoid models Cannot provide the cell of origin for tumor development |

[40,41] |

| Organoids | 3D models best used to study spatio-temporal dynamics. Built using stem cells (ASCs, iPSCs, ESC) from primary tumor and patient derived organoids (PDOs) | Extremely challenging to maintain due to lack of standardization protocol | [45] |

| Lineage tracing | Provides critical information during organ development and insights into the molecular mechanisms of cancer origin. Helps in real time dynamic tracing of CSCs. |

Unable to capture the molecular phenotype of each profiled cell | [50] |

| Bioprinting models | Used in combination with organoids to mimic tumor microenvironment, spatial distribution and helps in understanding stromal cell intravasation. | Absence of vasculature network | [95] |

| Biomimetic Tumoroids | Recreates the spatial distribution of nutrients and oxygen, to demonstrate cancer cell heterogeneity and the way it affects the vascular network formation | Lack of immune surveillance | [39] |

| On-a-chip models | Allows replication of dynamic culture systems to mimic the heterogeneity of the tumor microenvironment (microvasculature, immune cells, physicochemical TME) | Lack of extra cellular matrix expression | [52] |

| Single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Conversion of RNA into cDNA using non-probe RNA-seq technology, This technique uses microfluidics (Drop-seq) and inDROP system to generate droplets, which encapsulates microbeads with barcodes for reverse transcription amplification. The barcodes present are attached to individual gene, which can also enable tracing the origin of each gene. | Insufficient to detect rare subpopulations within tumor mass, disseminated tumor cells and extracellular matrix Prone to allelic dropout and excludes ECM False-positive errors associated with massive amplification of DNA Developing computational algorithms to analyse data on massive scale is a huge challenge Difficult to use in therapy-naïve primary lesions |

[48] |

| Single-cell assay for transposase accessible chromatin by sequencing (scATAC-seq) | Uses transcription factors and cis/trans regulatory elements for studying epigenetic modifications. Enables simultaneous profiling of accessible chromatin and protein levels, using transposase |

Exclusively binary data output Spatial mapping from closed to open chromatin is more difficult. Fails to detect rare or transient cell states or regulatory elements. |

[59] |

| Single-cell cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing (scCITE-seq) | Antibody panels are tested for detecting epitopes of interest, thus allowing simultaneous study of transcriptomic expression and cell surface protein marker. | Sensitive to enzymatic digestion due to loss of surface epitopes Difficult to perform antibody panel testing for developing the epitopes due to limited sample size |

[50] |

| Single-cell Clone (ScClone) | Employs probability mixture model from scDNA-seq data , by characterizing single cell into distinct subclones | Assumes genotypic errors are uniformly distributed leading to amplification bias. Does not explicitly model doublet events so its performance quality can get degraded |

[50] |

| Multiplex imaging | Allows spatial visualization and quantification of cell populations within metastatic tumors Generates multiple images of high-parameter protein biomarkers using an in-situ polymerization-based indexing procedure in conjugation with mass spectrometry, fluorescence-based microscopy and antibody-targeted sequencing |

Standardization of methods is needed Errors related to visual inspection due to huge dataset size Limited resolution to visualize overlapping cell fragments and irregularly shaped cell types (e.g. macrophages) |

[25] |

| NanoString GeoMx Digital Spatial Profiler (DSP) |

A novel high-plex, non-destructive protein and RNA profiling technique used to detect tumor heterogeneity in frozen or formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tumor samples. It quantifies the protein or RNA by counting unique indexing oligonucleotides, thereby allowing large number of biomarkers to be studied on spatial temporal scale |

Does not provide single-cell resolution information at spatial level. | [62] |

| NanoString CosMxTM | An upgradation of GeomX DSP used to simultaneously study localization of RNA at cellular and subcellular level. | Limited resolution of very small sized cells and overlapping cells. | [61] |

| 10X Visium |

Uses oligonucleotides immobilised on special glass slide (visium) to locate mRNA from fixed tumor samples, which are sequenced using Next Generation Sequencing | Limited resolution of very small sized cells and overlapping cells. | [61] |

| MERFISH |

Multiplexed single-molecule imaging technology used to simultaneously analyse thousands of RNA on spatial scale. | Variability in resolution of the data ranging from few to hundreds spots (number of cells within a single spatial region) | [60] |

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| ITH | intratumoral heterogeneity |

| CAF | cancer-associated fibroblast |

| TAM | tumor-associated macrophages |

| EMT | epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| CRC | colorectal cancer |

| scRNA-seq | single-cell RNA sequencing |

| FACS | fluorescence activated cell sorting |

| 2Do | 2-dimensional patient organoids |

| PDAC | pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| LP | primary lung adenocarcinoma |

| BM | brain metastasis |

| SCNA | somatic copy number alteration |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| DCC | disseminated cancer cells |

| PDX | patient-derived xenograft |

| PSA | prostate specific antigen |

| MCM3 | minichromosome maintenance protein 3 |

| MCT1 | Monocarboxylate transporter 1 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| CNV | Copy number variations |

| AR | androgen receptor |

| Macc1 | Metastasis associated colon cancer 1 |

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| MDR | multidrug resistance |

| CSC | cancer stem cell |

| GEMM | Genetically engineered mouse model |

| EPO GEMM | Electroporation-based Genetically engineered mice model |

| dT-MOC | ductal tumor-microenvironment-on-chip |

| MDA | multiple displacement amplification |

| MALBAC | multiple annealing and looping-based amplification cycles |

| DOP-PCR | degenerate oligonucleotide-primed PCR |

| TSCS | topographic single cell sequencing |

| AML | acute myeloid leukemia |

| scCITE-seq | Single-cell cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing |

| scChIP-seq | single-cell chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing |

| mESc | Mouse embryonic stem cells |

| mEF | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts |

| MALDI-MS | matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry imaging |

| MIBI-TOF | multiplexed ion beam imaging by time-of-flight |

| CODEX | co-detection by indexing |

| GDSC | Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer |

| CTRP | Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal |

| DPM | Drosophila Patient Model |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| ABC | approximate Bayesian computation |

| GAN | generative adversarial networks |

| DTC | Disseminated tumor cells |

| NCTB | National Cancer Tissue Biobank |

| CTRI | Clinical Trials Registry of India |

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2024;74(3):229–63. [CrossRef]

- Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, Salhab HA, Fares Y. Molecular principles of metastasis: a hallmark of cancer revisited. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2020 Mar 12;5(1):1–17.

- Mani K, Salgaonkar BB, Das D, Bragança JM. Community solar salt production in Goa, India. Aquat Biosyst. 2012 Dec 1;8(1):30. [CrossRef]

- Shi X, Wang X, Yao W, Shi D, Shao X, Lu Z, Chai Y, Song J, Tang W, Wang X. Mechanism insights and therapeutic intervention of tumor metastasis: latest developments and perspectives. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024 Aug 2;9(1):1–46. [CrossRef]

- Liu K, Han H, Xiong K, Zhai S, Yang X, Yu X, Chen B, Liu M, Dong Q, Meng H, Gu Y. Single-cell landscape of intratumoral heterogeneity and tumor microenvironment remolding in pre-nodal metastases of breast cancer. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2024 Aug 29;22(1):804. [CrossRef]

- El-Sayes N, Vito A, Mossman K. Tumor Heterogeneity: A Great Barrier in the Age of Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers. 2021 Jan;13(4):806. [CrossRef]

- Sun X xiao, Yu Q. Intra-tumor heterogeneity of cancer cells and its implications for cancer treatment. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015 Oct;36(10):1219–27.

- Li D, Xia L, Huang P, Wang Z, Guo Q, Huang C, Leng W, Qin S. Heterogeneity and plasticity of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cancer metastasis: Focusing on partial EMT and regulatory mechanisms. Cell Proliferation. 2023;56(6):e13423. [CrossRef]

- Brown MS, Abdollahi B, Wilkins OM, Lu H, Chakraborty P, Ognjenovic NB, Muller KE, Jolly MK, Christensen BC, Hassanpour S, Pattabiraman DR. Phenotypic heterogeneity driven by plasticity of the intermediate EMT state governs disease progression and metastasis in breast cancer [Internet]. bioRxiv; 2022 [cited 2025 Mar 14]. p. 2021.03.17.434993. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.17.434993v2.

- Ramón y Cajal S, Sesé M, Capdevila C, Aasen T, De Mattos-Arruda L, Diaz-Cano SJ, Hernández-Losa J, Castellví J. Clinical implications of intratumor heterogeneity: challenges and opportunities. J Mol Med. 2020 Feb 1;98(2):161–77. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Bai H, Zhang J, Wang Z, Duan J, Cai H, Cao Z, Lin Q, Ding X, Sun Y, Zhang W, Xu X, Chen H, Zhang D, Feng X, Wan J, Zhang J, He J, Wang J. Genetic Intratumor Heterogeneity Remodels the Immune Microenvironment and Induces Immune Evasion in Brain Metastasis of Lung Cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2024 Feb 1;19(2):252–72. [CrossRef]

- Fujino S, Miyoshi N, Ito A, Hayashi R, Yasui M, Matsuda C, Ohue M, Horie M, Yachida S, Koseki J, Shimamura T, Hata T, Ogino T, Takahashi H, Uemura M, Mizushima T, Doki Y, Eguchi H. Metastases and treatment-resistant lineages in patient-derived cancer cells of colorectal cancer. Commun Biol. 2023 Nov 24;6(1):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Vitale I, Shema E, Loi S, Galluzzi L. Intratumoral heterogeneity in cancer progression and response to immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2021 Feb;27(2):212–24. [CrossRef]

- Pasha N, Turner NC. Understanding and overcoming tumor heterogeneity in metastatic breast cancer treatment. Nat Cancer. 2021 Jul;2(7):680–92.

- Peng Z, Ye M, Ding H, Feng Z, Hu K. Spatial transcriptomics atlas reveals the crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor microenvironment components in colorectal cancer. J Transl Med. 2022 Jul 6;20(1):302. [CrossRef]

- Hapach LA, Carey SP, Schwager SC, Taufalele PV, Wang W, Mosier JA, Ortiz-Otero N, McArdle TJ, Goldblatt ZE, Lampi MC, Bordeleau F, Marshall JR, Richardson IM, Li J, King MR, Reinhart-King CA. Phenotypic Heterogeneity and Metastasis of Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Research. 2021 Jul 1;81(13):3649–63.

- Roper N, Gao S, Maity TK, Banday AR, Zhang X, Venugopalan A, Cultraro CM, Patidar R, Sindiri S, Brown AL, Goncearenco A, Panchenko AR, Biswas R, Thomas A, Rajan A, Carter CA, Kleiner DE, Hewitt SM, Khan J, Prokunina-Olsson L, Guha U. APOBEC Mutagenesis and Copy-Number Alterations Are Drivers of Proteogenomic Tumor Evolution and Heterogeneity in Metastatic Thoracic Tumors. Cell Rep. 2019 Mar 5;26(10):2651-2666.e6.

- Zhai W, Lai H, Kaya NA, Chen J, Yang H, Lu B, Lim JQ, Ma S, Chew SC, Chua KP, Alvarez JJS, Chen PJ, Chang MM, Wu L, Goh BKP, Chung AYF, Chan CY, Cheow PC, Lee SY, Kam JH, Kow AWC, Ganpathi IS, Chanwat R, Thammasiri J, Yoong BK, Ong DBL, de Villa VH, Dela Cruz RD, Loh TJ, Wan WK, Zeng Z, Skanderup AJ, Pang YH, Madhavan K, Lim TKH, Bonney G, Leow WQ, Chew V, Dan YY, Tam WL, Toh HC, Foo RSY, Chow PKH. Dynamic phenotypic heterogeneity and the evolution of multiple RNA subtypes in hepatocellular carcinoma: the PLANET study. National Science Review. 2022 Mar 1;9(3):nwab192. [CrossRef]

- Nobre AR, Dalla E, Yang J, Huang X, Wullkopf L, Risson E, Razghandi P, Anton ML, Zheng W, Seoane JA, Curtis C, Kenigsberg E, Wang J, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. ZFP281 drives a mesenchymal-like dormancy program in early disseminated breast cancer cells that prevents metastatic outgrowth in the lung. Nat Cancer. 2022 Oct;3(10):1165–80.

- Winkler J, Tan W, Diadhiou CMM, McGinnis CS, Abbasi A, Hasnain S, Durney S, Atamaniuc E, Superville D, Awni L, Lee JV, Hinrichs JH, Wagner PS, Singh N, Hein MY, Borja M, Detweiler AM, Liu SY, Nanjaraj A, Sitarama V, Rugo HS, Neff N, Gartner ZJ, Pisco AO, Goga A, Darmanis S, Werb Z. Single-cell analysis of breast cancer metastasis reveals epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity signatures associated with poor outcomes. J Clin Invest [Internet]. 2024 Sep 3 [cited 2025 Mar 14];134(17). Available from: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/164227.

- Hua X, Zhao W, Pesatori AC, Consonni D, Caporaso NE, Zhang T, Zhu B, Wang M, Jones K, Hicks B, Song L, Sampson J, Wedge DC, Shi J, Landi MT. Genetic and epigenetic intratumor heterogeneity impacts prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Commun. 2020 May 18;11(1):2459. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Gato D, Thysell E, Tyanova S, Crnalic S, Santos A, Lima TS, Geiger T, Cox J, Widmark A, Bergh A, Mann M, Flores-Morales A, Wikström P. The Proteome of Prostate Cancer Bone Metastasis Reveals Heterogeneity with Prognostic Implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 Nov 1;24(21):5433–44.

- Zou Y, Ye F, Kong Y, Hu X, Deng X, Xie J, Song C, Ou X, Wu S, Wu L, Xie Y, Tian W, Tang Y, Wong CW, Chen ZS, Xie X, Tang H. The Single-Cell Landscape of Intratumoral Heterogeneity and The Immunosuppressive Microenvironment in Liver and Brain Metastases of Breast Cancer. Advanced Science. 2023;10(5):2203699. [CrossRef]

- Tasdogan A, Faubert B, Ramesh V, Ubellacker JM, Shen B, Solmonson A, Murphy MM, Gu Z, Gu W, Martin M, Kasitinon SY, Vandergriff T, Mathews TP, Zhao Z, Schadendorf D, DeBerardinis RJ, Morrison SJ. Metabolic heterogeneity confers differences in melanoma metastatic potential. Nature. 2020 Jan;577(7788):115–20. [CrossRef]

- Moosavi SH, Eide PW, Eilertsen IA, Brunsell TH, Berg KCG, Røsok BI, Brudvik KW, Bjørnbeth BA, Guren MG, Nesbakken A, Lothe RA, Sveen A. De novo transcriptomic subtyping of colorectal cancer liver metastases in the context of tumor heterogeneity. Genome Medicine. 2021 Sep 1;13(1):143. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Zhang H, Chen X. Drug resistance and combating drug resistance in cancer. cdr. 2019 Jun 19;2(2):141–60.

- Maleki EH, Bahrami AR, Matin MM. Cancer cell cycle heterogeneity as a critical determinant of therapeutic resistance. Genes & Diseases. 2024 Jan 1;11(1):189–204. [CrossRef]

- Ryl T, Kuchen EE, Bell E, Shao C, Flórez AF, Mönke G, Gogolin S, Friedrich M, Lamprecht F, Westermann F, Höfer T. Cell-Cycle Position of Single MYC-Driven Cancer Cells Dictates Their Susceptibility to a Chemotherapeutic Drug. cels. 2017 Sep 27;5(3):237-250.e8. [CrossRef]

- Peng J, Sun BF, Chen CY, Zhou JY, Chen YS, Chen H, Liu L, Huang D, Jiang J, Cui GS, Yang Y, Wang W, Guo D, Dai M, Guo J, Zhang T, Liao Q, Liu Y, Zhao YL, Han DL, Zhao Y, Yang YG, Wu W. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intra-tumoral heterogeneity and malignant progression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Res. 2019 Sep;29(9):725–38.

- Yang F, Wang Y, Li Q, Cao L, Sun Z, Jin J, Fang H, Zhu A, Li Y, Zhang W, Wang Y, Xie H, Gustafsson JÅ, Wang S, Guan X. Intratumor heterogeneity predicts metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2017 Sep 1;38(9):900–9. [CrossRef]

- McMahon CM, Ferng T, Canaani J, Wang ES, Morrissette JJD, Eastburn DJ, Pellegrino M, Durruthy-Durruthy R, Watt CD, Asthana S, Lasater EA, DeFilippis R, Peretz CAC, McGary LHF, Deihimi S, Logan AC, Luger SM, Shah NP, Carroll M, Smith CC, Perl AE. Clonal Selection with RAS Pathway Activation Mediates Secondary Clinical Resistance to Selective FLT3 Inhibition in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Discovery. 2019 Aug 1;9(8):1050–63.

- Brady L, Kriner M, Coleman I, Morrissey C, Roudier M, True LD, Gulati R, Plymate SR, Zhou Z, Birditt B, Meredith R, Geiss G, Hoang M, Beechem J, Nelson PS. Inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity of metastatic prostate cancer determined by digital spatial gene expression profiling. Nat Commun. 2021 Mar 3;12(1):1426.

- Thankamony AP, Ramkomuth S, Ramesh ST, Murali R, Chakraborty P, Karthikeyan N, Varghese BA, Jaikumar VS, Jolly MK, Swarbrick A, Nair R. Phenotypic heterogeneity drives differential disease outcome in a mouse model of triple negative breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1230647. [CrossRef]

- Nowell PC. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976 Oct 1;194(4260):23–8.

- Lawrence-Paul MR, Pan T chi, Pant DK, Shih NNC, Chen Y, Belka GK, Feldman M, DeMichele A, Chodosh LA. Rare subclonal sequencing of breast cancers indicates putative metastatic driver mutations are predominately acquired after dissemination. Genome Medicine. 2024 Feb 6;16(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Wang D, Niu X, Wang Z, Song CL, Huang Z, Chen KN, Duan J, Bai H, Xu J, Zhao J, Wang Y, Zhuo M, Xie XS, Kang X, Tian Y, Cai L, Han JF, An T, Sun Y, Gao S, Zhao J, Ying J, Wang L, He J, Wang J. Multiregion Sequencing Reveals the Genetic Heterogeneity and Evolutionary History of Osteosarcoma and Matched Pulmonary Metastases. Cancer Res. 2019 Jan 1;79(1):7–20.

- Tu SM, Zhang M, Wood CG, Pisters LL. Stem Cell Theory of Cancer: Origin of Tumor Heterogeneity and Plasticity. Cancers. 2021 Jan;13(16):4006. [CrossRef]

- Tabuchi Y, Hirohashi Y, Hashimoto S, Mariya T, Asano T, Ikeo K, Kuroda T, Mizuuchi M, Murai A, Uno S, Kawai N, Kubo T, Nakatsugawa M, Kanaseki T, Tsukahara T, Saito T, Torigoe T. Clonal analysis revealed functional heterogeneity in cancer stem-like cell phenotypes in uterine endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol. 2019 Feb;106:78–88. [CrossRef]

- Bradney MJ, Venis SM, Yang Y, Konieczny SF, Han B. A Biomimetic Tumor Model of Heterogeneous Invasion in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Small. 2020;16(10):1905500. [CrossRef]

- Leibold J, Tsanov KM, Amor C, Ho YJ, Sánchez-Rivera FJ, Feucht J, Baslan T, Chen HA, Tian S, Simon J, Wuest A, Wilkinson JE, Lowe SW. Somatic mouse models of gastric cancer reveal genotype-specific features of metastatic disease. Nat Cancer. 2024 Feb;5(2):315–29. [CrossRef]

- Proietto M, Crippa M, Damiani C, Pasquale V, Sacco E, Vanoni M, Gilardi M. Tumor heterogeneity: preclinical models, emerging technologies, and future applications. Front Oncol [Internet]. 2023 Apr 28 [cited 2025 Mar 14];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2023.1164535/full.

- Liu Y, Wu W, Cai C, Zhang H, Shen H, Han Y. Patient-derived xenograft models in cancer therapy: technologies and applications. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Apr 12;8(1):1–24. [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou D, Callari M, Rueda OM, Shea A, Martin A, Giovannetti A, Qosaj F, Dariush A, Chin SF, Carnevalli LS, Provenzano E, Greenwood W, Lerda G, Esmaeilishirazifard E, O’Reilly M, Serra V, Bressan D, Gordon B. Mills, Ali HR, Cosulich SS, Hannon GJ, Bruna A, Caldas C. Landscapes of cellular phenotypic diversity in breast cancer xenografts and their impact on drug response. Nat Commun. 2021 Mar 31;12(1):1998. [CrossRef]

- Arena S, Corti G, Durinikova E, Montone M, Reilly NM, Russo M, Lorenzato A, Arcella P, Lazzari L, Rospo G, Pagani M, Cancelliere C, Negrino C, Isella C, Bartolini A, Cassingena A, Amatu A, Mauri G, Sartore-Bianchi A, Mittica G, Medico E, Marsoni S, Linnebacher M, Abrignani S, Siena S, Di Nicolantonio F, Bardelli A. A Subset of Colorectal Cancers with Cross-Sensitivity to Olaparib and Oxaliplatin. Clinical Cancer Research. 2020 Mar 13;26(6):1372–84.

- Dekkers JF, Alieva M, Cleven A, Keramati F, Wezenaar AKL, van Vliet EJ, Puschhof J, Brazda P, Johanna I, Meringa AD, Rebel HG, Buchholz MB, Barrera Román M, Zeeman AL, de Blank S, Fasci D, Geurts MH, Cornel AM, Driehuis E, Millen R, Straetemans T, Nicolasen MJT, Aarts-Riemens T, Ariese HCR, Johnson HR, van Ineveld RL, Karaiskaki F, Kopper O, Bar-Ephraim YE, Kretzschmar K, Eggermont AMM, Nierkens S, Wehrens EJ, Stunnenberg HG, Clevers H, Kuball J, Sebestyen Z, Rios AC. Uncovering the mode of action of engineered T cells in patient cancer organoids. Nat Biotechnol. 2023 Jan;41(1):60–9.

- Kashima Y, Sakamoto Y, Kaneko K, Seki M, Suzuki Y, Suzuki A. Single-cell sequencing techniques from individual to multiomics analyses. Exp Mol Med. 2020 Sep;52(9):1419–27. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Dong X, Lee M, Maslov AY, Wang T, Vijg J. Single-cell whole-genome sequencing reveals the functional landscape of somatic mutations in B lymphocytes across the human lifespan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019 Apr 30;116(18):9014–9.

- Chung W, Eum HH, Lee HO, Lee KM, Lee HB, Kim KT, Ryu HS, Kim S, Lee JE, Park YH, Kan Z, Han W, Park WY. Single-cell RNA-seq enables comprehensive tumour and immune cell profiling in primary breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2017 May 5;8(1):15081. [CrossRef]

- Tirosh I, Izar B, Prakadan SM, Wadsworth MH, Treacy D, Trombetta JJ, Rotem A, Rodman C, Lian C, Murphy G, Fallahi-Sichani M, Dutton-Regester K, Lin JR, Cohen O, Shah P, Lu D, Genshaft AS, Hughes TK, Ziegler CGK, Kazer SW, Gaillard A, Kolb KE, Villani AC, Johannessen CM, Andreev AY, Van Allen EM, Bertagnolli M, Sorger PK, Sullivan RJ, Flaherty KT, Frederick DT, Jané-Valbuena J, Yoon CH, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Shalek AK, Regev A, Garraway LA. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2016 Apr 8;352(6282):189–96.

- Chen S, Jiang W, Du Y, Yang M, Pan Y, Li H, Cui M. Single-cell analysis technologies for cancer research: from tumor-specific single cell discovery to cancer therapy. Front Genet [Internet]. 2023 Oct 12 [cited 2025 Mar 14];14. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2023.1276959/full.

- Lischetti U, Tastanova A, Singer F, Grob L, Carrara M, Cheng PF, Martínez Gómez JM, Sella F, Haunerdinger V, Beisel C, Levesque MP. Dynamic thresholding and tissue dissociation optimization for CITE-seq identifies differential surface protein abundance in metastatic melanoma. Commun Biol. 2023 Aug 10;6(1):1–16. [CrossRef]

- Grosselin K, Durand A, Marsolier J, Poitou A, Marangoni E, Nemati F, Dahmani A, Lameiras S, Reyal F, Frenoy O, Pousse Y, Reichen M, Woolfe A, Brenan C, Griffiths AD, Vallot C, Gérard A. High-throughput single-cell ChIP-seq identifies heterogeneity of chromatin states in breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2019 Jun;51(6):1060–6. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Larsson L, Swarbrick A, Lundeberg J. Spatial landscapes of cancers: insights and opportunities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2024 Sep;21(9):660–74. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Q, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Li Y, Liu S, Han J, Sun Z, Wang C, Deng D, Wang S, Tang Y, Huang Y, Jiang S, Tian C, Chen X, Yuan Y, Li Z, Yang T, Lai T, Liu Y, Yang W, Zou X, Zhang M, Cui H, Liu C, Jin X, Hu Y, Chen A, Xu X, Li G, Hou Y, Liu L, Liu S, Fang L, Chen W, Wu L. Single cell multi-omics reveal intra-cell-line heterogeneity across human cancer cell lines. Nat Commun. 2023 Dec 9;14(1):8170.

- Parker AL, Benguigui M, Fornetti J, Goddard E, Lucotti S, Insua-Rodríguez J, Wiegmans AP, Early Career Leadership Council of the Metastasis Research Society. Current challenges in metastasis research and future innovation for clinical translation. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2022 Apr 1;39(2):263–77. [CrossRef]

- van Dam S, Baars MJD, Vercoulen Y. Multiplex Tissue Imaging: Spatial Revelations in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers. 2022 Jan;14(13):3170.

- Yu Z, Du F, Song L. SCClone: Accurate Clustering of Tumor Single-Cell DNA Sequencing Data. Front Genet [Internet]. 2022 Jan 27 [cited 2025 Mar 14];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.823941/full.

- Lawson DA, Kessenbrock K, Davis RT, Pervolarakis N, Werb Z. Tumour heterogeneity and metastasis at single-cell resolution. Nat Cell Biol. 2018 Dec;20(12):1349–60. [CrossRef]

- Cheng M, Jiang Y, Xu J, Mentis AFA, Wang S, Zheng H, Sahu SK, Liu L, Xu X. Spatially resolved transcriptomics: a comprehensive review of their technological advances, applications, and challenges. Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 2023 Sep 1;50(9):625–40. [CrossRef]

- Xia C, Fan J, Emanuel G, Hao J, Zhuang X. Spatial transcriptome profiling by MERFISH reveals subcellular RNA compartmentalization and cell cycle-dependent gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Sep 24;116(39):19490–9. [CrossRef]

- Andersson A, Larsson L, Stenbeck L, Salmén F, Ehinger A, Wu SZ, Al-Eryani G, Roden D, Swarbrick A, Borg Å, Frisén J, Engblom C, Lundeberg J. Spatial deconvolution of HER2-positive breast cancer delineates tumor-associated cell type interactions. Nat Commun. 2021 Oct 14;12(1):6012.

- Hernandez S, Lazcano R, Serrano A, Powell S, Kostousov L, Mehta J, Khan K, Lu W, Solis LM. Challenges and Opportunities for Immunoprofiling Using a Spatial High-Plex Technology: The NanoString GeoMx® Digital Spatial Profiler. Front Oncol [Internet]. 2022 Jun 29 [cited 2025 Mar 14];12. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2022.890410/full. [CrossRef]

- Semba T, Ishimoto T. Spatial analysis by current multiplexed imaging technologies for the molecular characterisation of cancer tissues. Br J Cancer. 2024 Dec;131(11):1737–47.

- Blighe K, Kenny L, Patel N, Guttery DS, Page K, Gronau JH, Golshani C, Stebbing J, Coombes RC, Shaw JA. Whole Genome Sequence Analysis Suggests Intratumoral Heterogeneity in Dissemination of Breast Cancer to Lymph Nodes. PLoS One. 2014 Dec 29;9(12):e115346. [CrossRef]

- Schupp PG, Shelton SJ, Brody DJ, Eliscu R, Johnson BE, Mazor T, Kelley KW, Potts MB, McDermott MW, Huang EJ, Lim DA, Pieper RO, Berger MS, Costello JF, Phillips JJ, Oldham MC. Deconstructing Intratumoral Heterogeneity through Multiomic and Multiscale Analysis of Serial Sections. Cancers. 2024 Jan;16(13):2429. [CrossRef]

- Ionkina AA, Balderrama-Gutierrez G, Ibanez KJ, Phan SHD, Cortez AN, Mortazavi A, Prescher JA. Transcriptome analysis of heterogeneity in mouse model of metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research. 2021 Sep 27;23(1):93.

- Contreras-Trujillo H, Eerdeng J, Akre S, Jiang D, Contreras J, Gala B, Vergel-Rodriguez MC, Lee Y, Jorapur A, Andreasian A, Harton L, Bramlett CS, Nogalska A, Xiao G, Lee JW, Chan LN, Müschen M, Merchant AA, Lu R. Deciphering intratumoral heterogeneity using integrated clonal tracking and single-cell transcriptome analyses. Nat Commun. 2021 Nov 11;12:6522. [CrossRef]

- Xulu KR, Nweke EE, Augustine TN. Delineating intra-tumoral heterogeneity and tumor evolution in breast cancer using precision-based approaches. Front Genet [Internet]. 2023 Aug 17 [cited 2025 Apr 6];14. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2023.1087432/full. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Aguilera A, Masmudi-Martín M, Navas-Olive A, Baena P, Hernández-Oliver C, Priego N, Cordón-Barris L, Alvaro-Espinosa L, García S, Martínez S, Lafarga M, Lin MZ, Al-Shahrour F, Menendez de la Prida L, Valiente M. Machine learning identifies experimental brain metastasis subtypes based on their influence on neural circuits. Cancer Cell. 2023 Sep 11;41(9):1637-1649.e11.

- Prasanna CVS, Jolly MK, Bhat R. Spatial heterogeneity in tumor adhesion qualifies collective cell invasion. Biophysical Journal. 2024 Jun 18;123(12):1635–47. [CrossRef]

- Jain R, Mallya MV, Amoncar S, Palyekar S, Adsul HP, Kumar R, Chawla S. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among potential convalescent plasma donors and analysis of their deferral pattern: Experience from tertiary care hospital in western India. Transfusion Clinique et Biologique. 2022 Feb 1;29(1):60–4. [CrossRef]

- Jarrett AM, Lima EABF, Hormuth DA, McKenna MT, Feng X, Ekrut DA, Resende ACM, Brock A, Yankeelov TE. Mathematical Models of Tumor Cell Proliferation: A Review of the Literature. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018 Dec;18(12):1271–86. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Wang S, Zou X. Data-driven mathematical modeling and quantitative analysis of cell dynamics in the tumor microenvironment. Computers & Mathematics with Applications. 2022 May 1;113:300–14. [CrossRef]

- Padder A, Rahman Shah TU, Afroz A, Mushtaq A, Tomar A. A mathematical model to study the role of dystrophin protein in tumor micro-environment. Sci Rep. 2024 Nov 13;14(1):27801. [CrossRef]

- Mahlbacher G, Curtis LT, Lowengrub J, Frieboes HB. Mathematical modeling of tumor-associated macrophage interactions with the cancer microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer. 2018 Dec 1;6(1):10.

- Szabó A, Merks RMH. Cellular Potts Modeling of Tumor Growth, Tumor Invasion, and Tumor Evolution. Front Oncol [Internet]. 2013 Apr 16 [cited 2025 Apr 6];3. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2013.00087/full. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Wang K, Du Y, Yang H, Jia G, Huang D, Chen W, Shan Y. Computational Modeling to Determine the Effect of Phenotypic Heterogeneity in Tumors on the Collective Tumor–Immune Interactions. Bull Math Biol. 2023 May 4;85(6):51. [CrossRef]

- Subhadarshini S, Sahoo S, Debnath S, Somarelli JA, Jolly MK. Dynamical modeling of proliferative-invasive plasticity and IFNγ signaling in melanoma reveals mechanisms of PD-L1 expression heterogeneity. J Immunother Cancer. 2023 Sep;11(9):e006766. [CrossRef]

- Zhao B, Pritchard JR, Lauffenburger DA, Hemann MT. Addressing genetic tumor heterogeneity through computationally predictive combination therapy. Cancer Discov. 2014 Feb;4(2):166–74.

- Qian J, Shao X, Bao H, Fang Y, Guo W, Li C, Li A, Hua H, Fan X. Identification and characterization of cell niches in tissue from spatial omics data at single-cell resolution. Nat Commun. 2025 Feb 16;16(1):1693.

- Carranza FG, Diaz FC, Ninova M, Velazquez-Villarreal E. Current state and future prospects of spatial biology in colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2024 Dec 3;14:1513821. [CrossRef]

- Fetahu IS, Esser-Skala W, Dnyansagar R, Sindelar S, Rifatbegovic F, Bileck A, Skos L, Bozsaky E, Lazic D, Shaw L, Tötzl M, Tarlungeanu D, Bernkopf M, Rados M, Weninger W, Tomazou EM, Bock C, Gerner C, Ladenstein R, Farlik M, Fortelny N, Taschner-Mandl S. Single-cell transcriptomics and epigenomics unravel the role of monocytes in neuroblastoma bone marrow metastasis. Nat Commun. 2023 Jun 26;14(1):3620. [CrossRef]

- Cilento MA, Sweeney CJ, Butler LM. Spatial transcriptomics in cancer research and potential clinical impact: a narrative review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024 Jun 8;150(6):296.

- Ayestaran I, Galhoz A, Spiegel E, Sidders B, Dry JR, Dondelinger F, Bender A, McDermott U, Iorio F, Menden MP. Identification of Intrinsic Drug Resistance and Its Biomarkers in High-Throughput Pharmacogenomic and CRISPR Screens. Patterns (N Y). 2020 Jul 2;1(5):100065.

- Min DJ, Zhao Y, Monks A, Palmisano A, Hose C, Teicher BA, Doroshow JH, Simon RM. Identification of pharmacodynamic biomarkers and common molecular mechanisms of response to genotoxic agents in cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019 Oct;84(4):771–80. [CrossRef]

- Al-Harazi O, Kaya IH, El Allali A, Colak D. A Network-Based Methodology to Identify Subnetwork Markers for Diagnosis and Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer. Front Genet. 2021;12:721949. [CrossRef]

- Partin A, Brettin TS, Zhu Y, Narykov O, Clyde A, Overbeek J, Stevens RL. Deep learning methods for drug response prediction in cancer: Predominant and emerging trends. Front Med [Internet]. 2023 Feb 15 [cited 2025 Apr 6];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2023.1086097/full.

- Ali M, Aittokallio T. Machine learning and feature selection for drug response prediction in precision oncology applications. Biophys Rev. 2018 Aug 10;11(1):31–9. [CrossRef]

- Rees MG, Brenan L, do Carmo M, Duggan P, Bajrami B, Arciprete M, Boghossian A, Vaimberg E, Ferrara SJ, Lewis TA, Rosenberg D, Sangpo T, Roth JA, Kaushik VK, Piccioni F, Doench JG, Root DE, Johannessen CM. Systematic identification of biomarker-driven drug combinations to overcome resistance. Nat Chem Biol. 2022 Jun;18(6):615–24. [CrossRef]

- Gondal MN, Butt RN, Shah OS, Sultan MU, Mustafa G, Nasir Z, Hussain R, Khawar H, Qazi R, Tariq M, Faisal A, Chaudhary SU. A Personalized Therapeutics Approach Using an In Silico Drosophila Patient Model Reveals Optimal Chemo- and Targeted Therapy Combinations for Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021 Jul 16;11:692592. [CrossRef]

- Wu Z, Huang D, Wang J, Zhao Y, Sun W, Shen X. Engineering Heterogeneous Tumor Models for Biomedical Applications. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023 Nov 9;11(1):2304160. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi S, Augustin AI, Dunlop A, Sukumaran R, Dheer S, Zavalny A, Haslam O, Austin T, Donchez J, Tripathi PK, Kim E. Recent advances and application of generative adversarial networks in drug discovery, development, and targeting. Artificial Intelligence in the Life Sciences. 2022 Dec 1;2:100045. [CrossRef]

- Bacon ER, Ihle K, Guo W, Egelston CA, Simons DL, Wei C, Tumyan L, Schmolze D, Lee PP, Waisman JR. Tumor heterogeneity and clinically invisible micrometastases in metastatic breast cancer—a call for enhanced surveillance strategies. npj Precis Onc. 2024 Mar 29;8(1):1–11. [CrossRef]

- McKigney N, Seligmann J, Twiddy M, Bach S, Mohamed F, Fearnhead N, Brown JM, Harji DP. A qualitative study to understand the challenges of conducting randomised controlled trials of complex interventions in metastatic colorectal cancer. Trials. 2025 Mar 19;26(1):98. [CrossRef]

- Samadian H, Jafari S, Sepand MR, Alaei L, Sadegh Malvajerd S, Jaymand M, Ghobadinezhad F, Jahanshahi F, Hamblin MR, Derakhshankhah H, Izadi Z. 3D bioprinting technology to mimic the tumor microenvironment: tumor-on-a-chip concept. Materials Today Advances. 2021 Dec 1;12:100160. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).