Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

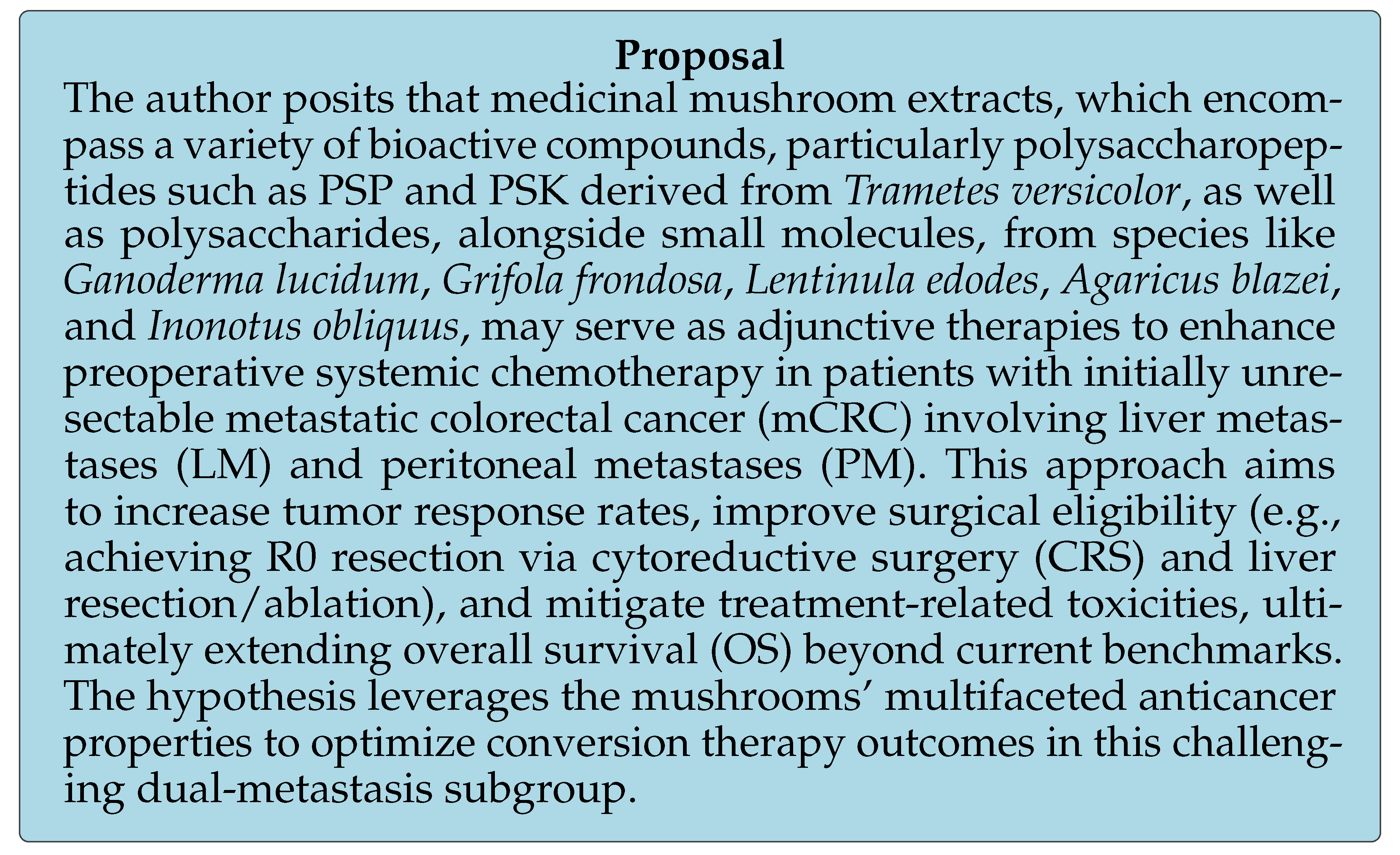

1. Background and Disease Context

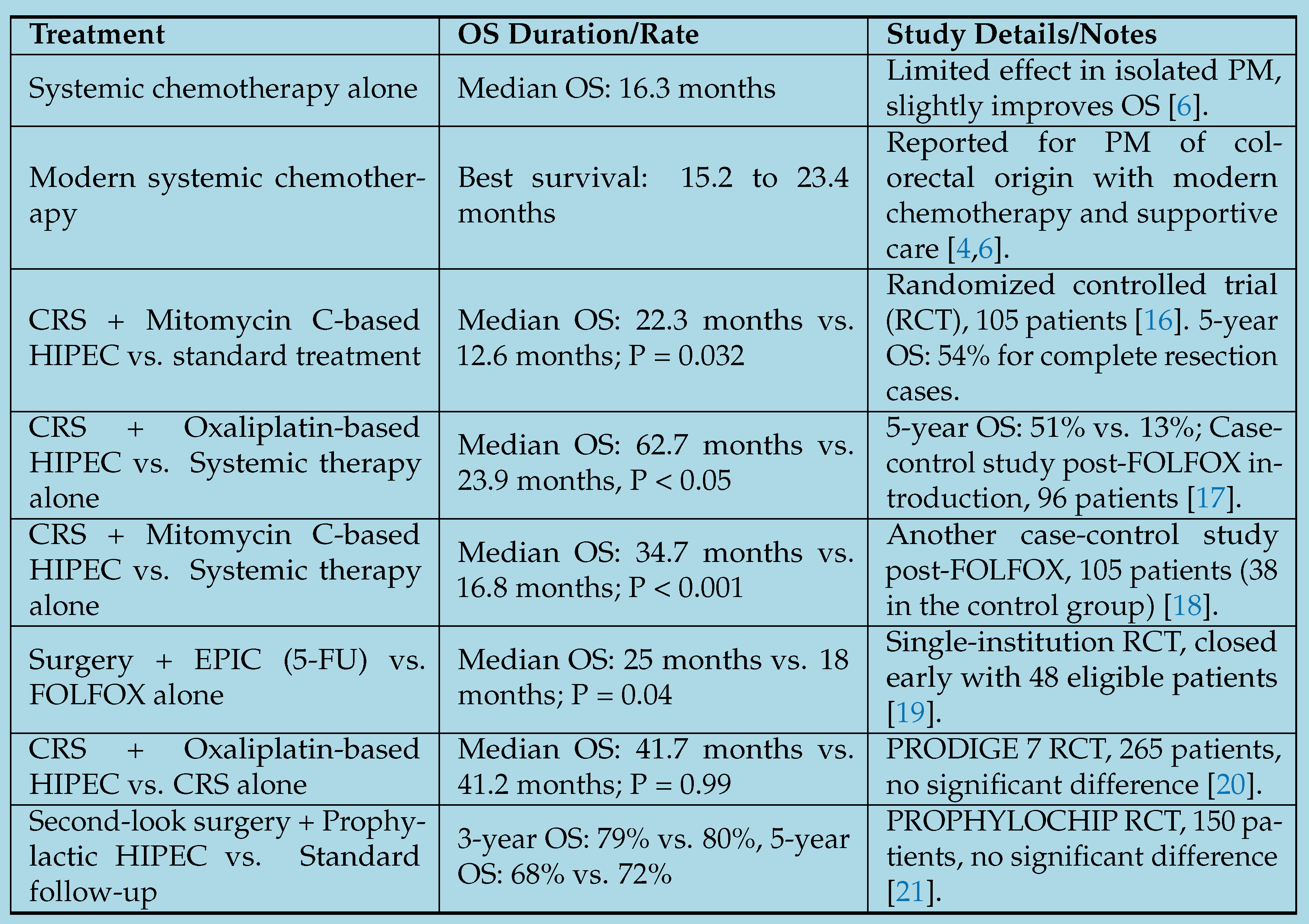

1.1. Assessment of the Efficacy of Systemic Chemotherapy as a Standalone Treatment

1.2. Combined Treatment Approaches and Comparative Outcomes

1.3. Patient Selection and Challenges

1.4. Treatment-Specific Survival Rates with Peritoneal Involvement

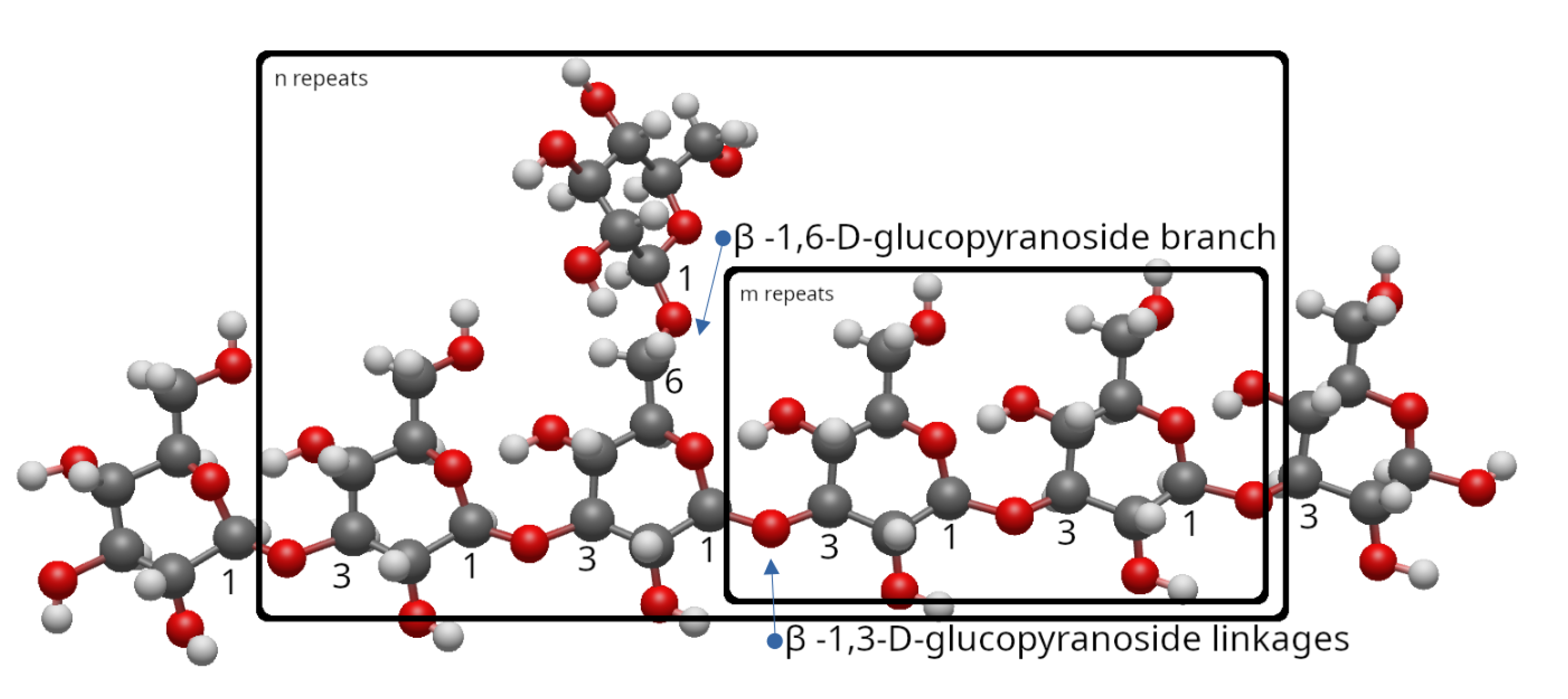

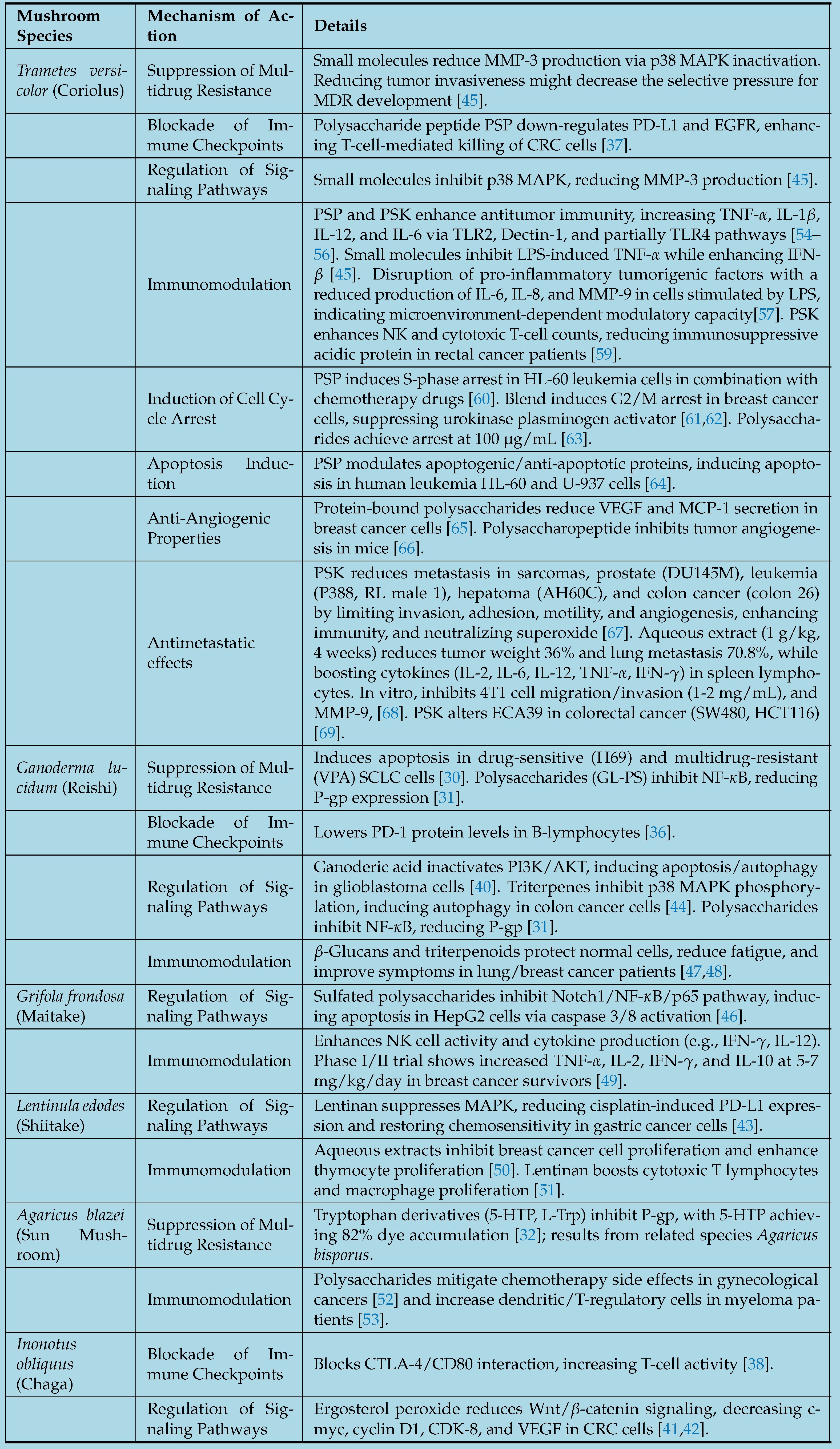

2. Anticancer Mechanisms of Action in Selected Medicinal Mushrooms

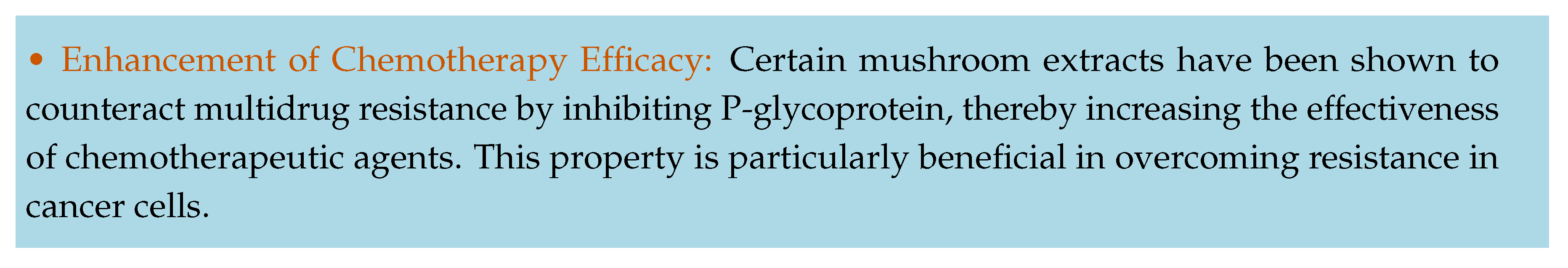

2.0.1. Suppression of Multidrug Resistance

2.0.2. Blockade of Immune Checkpoints

2.0.3. Regulation of Signaling Pathways

2.0.4. Immunomodulation

2.0.5. Induction of Cell Cycle Arrest

2.0.6. Anti-Angiogenic Properties

2.0.7. Antimetastatic Effects

2.1. Clinical Evidence and Broader Benefits

3. Medicinal Mushrooms as Adjunctive Therapy in Cancer Treatment: A Concise Summary

4. Review of Human Studies with a Focus on Medicinal Mushroom Compounds in Cancer Patients

4.1. Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum), Maitake D-Fraction (Grifola frondosa D-Fraction), Lentinan (Lentinula edodes Extract), and AHCC (Active Hexose Correlated Compound, Derived from Various Basidiomycetes)

4.2. Turkey Tail (Coriolus/Trametes versicolor)

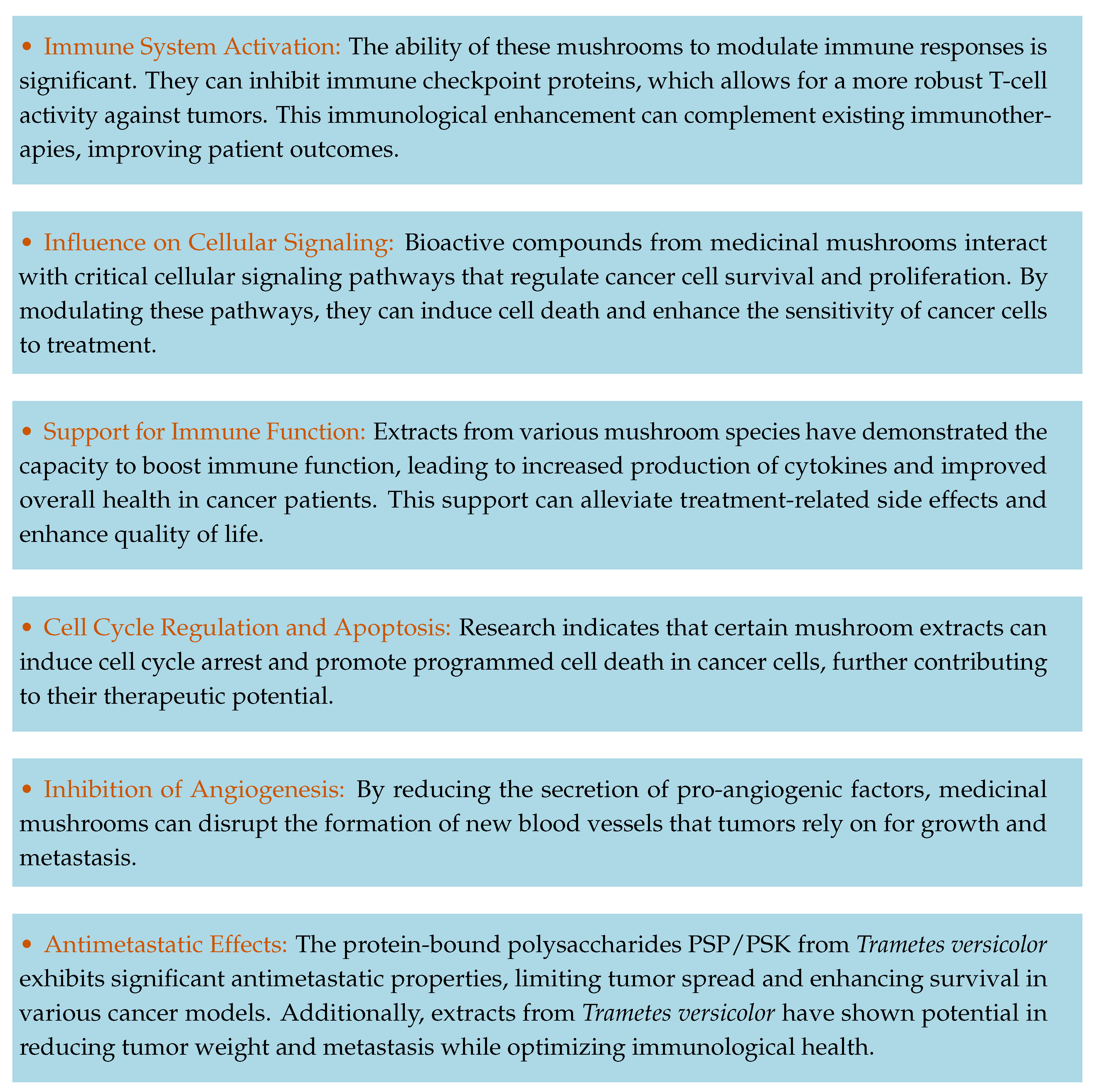

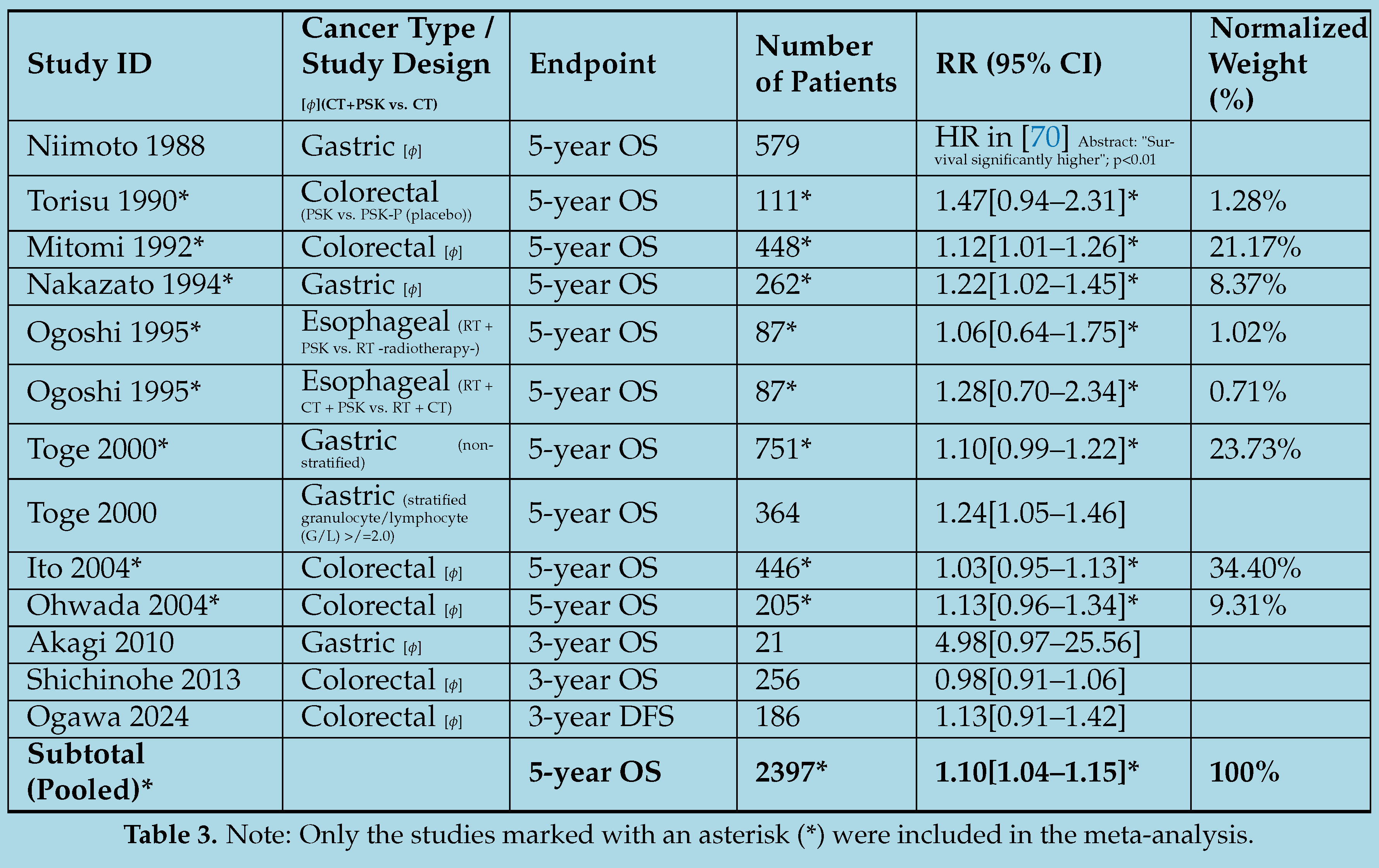

4.3. Exploring the Efficacy of Adjuvant Immunochemotherapy with PSP/PSK: A Meta-Analysis of Selected Randomized Controlled Trials

5. Extraction Methods and Composition of Polysaccharides and Other Bioactive Compounds Found in Medicinal Mushrooms

5.1. Comprehensive Analysis of Medicinal Compounds in Selected Mushrooms

5.1.1. Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum)

5.1.2. Maitake D-Fraction (Grifola frondosa D-Fraction)

5.1.3. Lentinan (Lentinula edodes Extract)

5.1.4. AHCC (Active Hexose Correlated Compound)

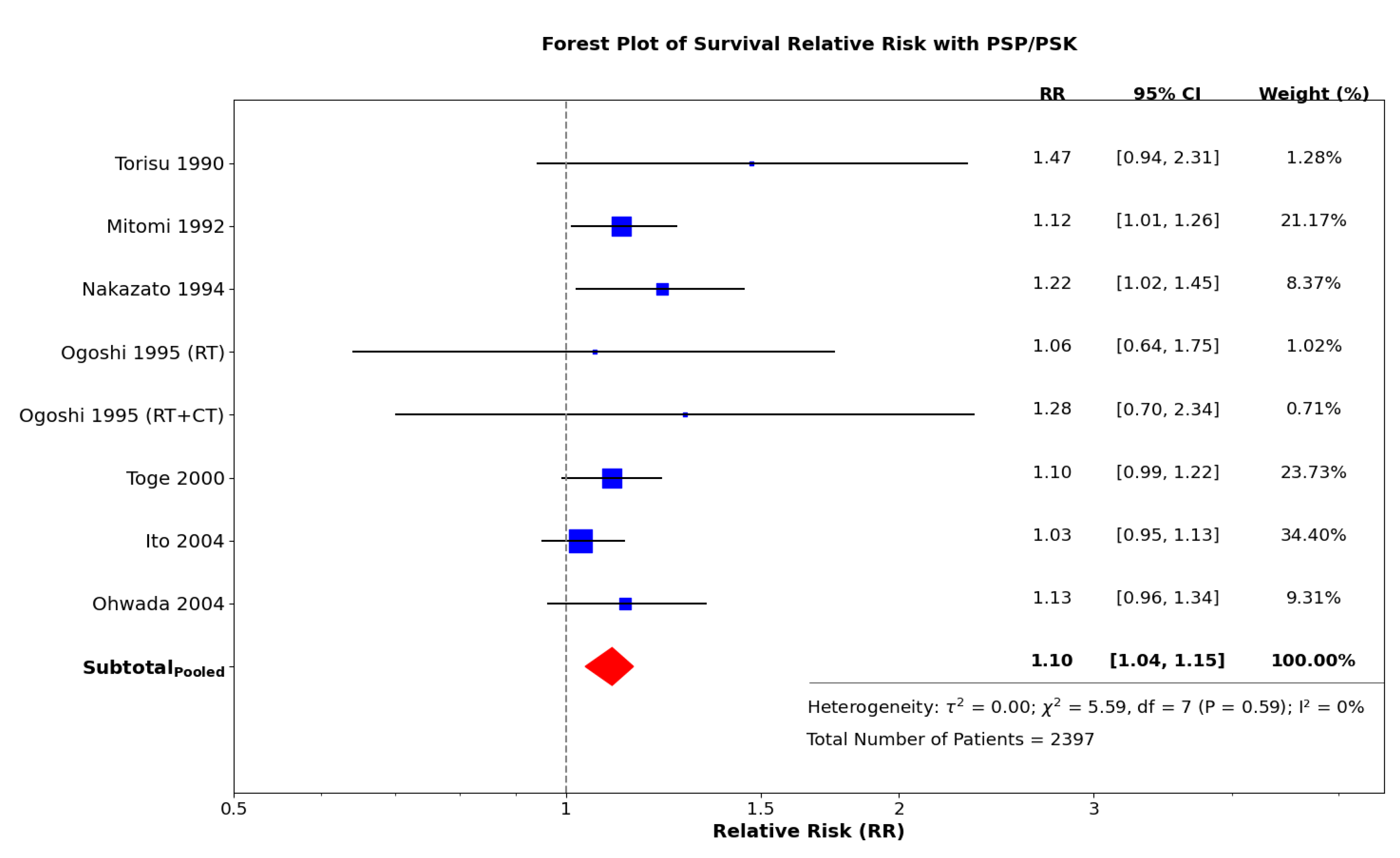

5.1.5. Turkey Tail (Trametes/Coriolus versicolor)

6. Enhancing Surgical Eligibility: A Proposal for the Use of Medicinal Mushroom Extracts as an Adjunctive Therapy to Optimize Preoperative Systemic Chemotherapy Outcomes

6.1. Clinical Context, Rationale, and Limitations of Current Therapies

6.2. Medicinal Mushroom Extracts: Mechanisms and Evidence

6.3. Potential in Conversion Therapy

6.3.1. Safety and Practical Integration

6.3.2. Implementation and Testing

6.3.3. Expected Outcomes and Implications

6.3.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

Acronyms

- 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil

- 5-HTP: 5-Hydroxy-L-Tryptophan

- AHCC: Active Hexose Correlated Compound

- ATA: Anctin-A

- CA125: Cancer Antigen 125

- CC: Completeness of Cytoreduction (e.g., CC-0, CC-1)

- CI: Confidence Interval

- CLA: Conjugated Linoleic Acid

- CNKI: China National Knowledge Infrastructure

- CRC: Colorectal Cancer

- CRS: Cytoreductive Surgery

- CRT: Chemoradiotherapy

- CT: Chemotherapy

- CTLA-4: Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein 4

- CVP: Coriolus Versicolor Polysaccharides

- Da: Dalton

- DFS: Disease-Free Survival

- dMMR: Deficient Mismatch Repair

- ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- EGFR: Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- FIP: Fungal Immunomodulatory Protein

- FOLFIRI: 5-Fluorouracil + Leucovorin + Irinotecan

- FOLFOX: 5-Fluorouracil + Leucovorin + Oxaliplatin

- FOLFOXIRI: 5-Fluorouracil + Leucovorin + Oxaliplatin + Irinotecan

- GFG: Grifola Frondosa Glycoprotein

- GLP: Ganoderma Lucidum Peptides

- GL-PS: Ganoderma Lucidum Polysaccharides

- GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- GSP: Ganoderma Sinense Polysaccharide

- HIPEC: Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy

- IgG / IgM: Immunoglobulin G / M

- IL-: Interleukin- (e.g., IL-6, IL-2)

- IFN-: Interferon-gamma

- LM: Liver Metastases

- LPS: Lipopolysaccharide

- LR: Liver Resection

- LV: Leucovorin

- MAPK: Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase

- mCRC: Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

- MDR: Multidrug Resistance

- MMP-3: Matrix Metalloproteinase-3

- MSI-H: Microsatellite Instability-High

- MSS: Microsatellite Stable

- NCI: National Cancer Institute

- NF-B: Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of Activated B Cells

- NK: Natural Killer Cells

- NLM: Non-Liver Metastases

- NSCLC: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

- OS: Overall Survival

- PAMP: Pathogen-Associated Molecular Pattern

- PB-Mac: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Adherent Cells

- PBP: Protein-Bound Polysaccharide

- PCI: Peritoneal Cancer Index

- PD-1: Programmed Cell Death Protein 1

- PD-L1: Programmed Death-Ligand 1

- PDQ: Physician Data Query

- PFS: Progression-Free Survival

- P-gp: P-glycoprotein

- PI3K/AKT: Phospho-Inositide 3-Kinase / Protein Kinase B

- PM: Peritoneal Metastases

- pMMR: Proficient Mismatch Repair

- PSA: Prostate-Specific Antigen

- PSK: Polysaccharide-K (Krestin)

- PSP: Polysaccharide Peptide

- R0: Complete Resection

- RCT: Randomized Controlled Trial

- RR: Risk Ratio

- TNF-: Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha

- UFT: Tegafur/Uracil

- VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

- VIP: Chongqing VIP Chinese Scientific Journals Database

- WGP: Whole Glucan Particle

- XELOX: Xeloda (Capecitabine) + Oxaliplatin

Appendix A. Analysis of Silymarin’s Potential as a Hepatoprotector and Antimetastatic Agent

Appendix A.1. Background on Silymarin

Appendix A.2. Potential to Prevent Hepatic Metastasis

Appendix A.3. Protection of the Liver Against Chemotherapy-Induced Toxicity in Healthy Cells

Appendix A.4. Non-Inhibition of Chemotherapy Effects on Metastatic Cells

Appendix A.5. Conclusion

References

- Kim, Y.; Kim, C. Treatment for Peritoneal Metastasis of Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Annals of Coloproctology 2021, 37, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kow, A. Hepatic metastasis from colorectal cancer. Journal of gastrointestinal oncology 2019, 10, 1274–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- März, L.; Piso, P. Treatment of peritoneal metastases from colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology Report 2015, 3, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaver, Y.L.B.; Simkens, L.H.J.; Lemmens, V.E.P.P.; Koopman, M.; Teerenstra, S.; Bleichrodt, R.P.; de Hingh, I.H.J.T.; Punt, C.J.A. Outcomes of colorectal cancer patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with chemotherapy with and without targeted therapy. European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO) 2012, 38, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, A.; McCart, J.A.; Govindarajan, A. Peritoneal Carcinomatosis from Colon Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Data for Cytoreduction and Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery 2015, 28, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franko, J.; Shi, Q.; Meyers, J.P.; Maughan, T.S.; Adams, R.A.; Seymour, M.T.; Saltz, L.; Punt, C.J.A.; Koopman, M.; Tournigand, C.; et al. Prognosis of patients with peritoneal metastatic colorectal cancer given systemic therapy: an analysis of individual patient data from prospective randomised trials from the Analysis and Research in Cancers of the Digestive System (ARCAD) database. The Lancet Oncology 2016, 17, 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Moreno, F.; Diez-Alonso, M.; Matías-García, B.; Ovejero-Merino, E.; Gómez-Sanz, R.; Blázquez-Martín, A.; Quiroga-Valcárcel, A.; Vera-Mansilla, C.; Molina, R.; San-Juan, A.; et al. Prognostic Factors of Survival in Patients with Peritoneal Metastasis from Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franko, J. Therapeutic efficacy of systemic therapy for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis: Surgeon’s perspective. Pleura and peritoneum 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Raeisi, M.; Chibaudel, B.; Shi, Q.; Yoshino, T.; Zalcberg, J.R.; Adams, R.; Cremolini, C.; Cutsem, E.V.; Heinemann, V.; et al. Prognostic value of liver metastases in colorectal cancer treated by systemic therapy: An ARCAD pooled analysis. European Journal of Cancer 2024, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loupakis, F.; Cremolini, C.; Masi, G.; Lonardi, S.; Zagonel, V.; Salvatore, L.; Cortesi, E.; Tomasello, G.; Ronzoni, M.; Spadi, R.; et al. Initial Therapy with FOLFOXIRI and Bevacizumab for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2014, 371, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremolini, C.; Antoniotti, C.; Stein, A.; Bendell, J.; Gruenberger, T.; Rossini, D.; Masi, G.; Ongaro, E.; Hurwitz, H.; Falcone, A.; et al. Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of FOLFOXIRI Plus Bevacizumab Versus Doublets Plus Bevacizumab as Initial Therapy of Unresectable Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2020, 38, 3314–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, V.K.; Kennedy, E.B.; Baxter, N.N.; 3rd, A.B.B.; Cercek, A.; Cho, M.; Ciombor, K.K.; Cremolini, C.; Davis, A.; Deming, D.A.; et al. Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: ASCO Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2022, 41, 678–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polderdijk, M.C.E.; Brouwer, M.; Haverkamp, L.; Ziesemer, K.A.; Tenhagen, M.; Boerma, D.; Kok, N.F.M.; Versteeg, K.S.; Sommeijer, D.W.; Tanis, P.J.; et al. Outcomes of Combined Peritoneal and Local Treatment for Patients with Peritoneal and Limited Liver Metastases of Colorectal Origin: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2022, 29, 1952–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dico, R.L.; Faron, M.; Yonemura, Y.; Glehen, O.; Pocard, M.; Sardi, A.; Hübner, M.; Baratti, D.; Liberale, G.; Kartheuser, A.; et al. Combined liver resection and cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC for metastatic colorectal cancer: Results of a worldwide analysis of 565 patients from the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI). European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2021, 47, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasello, G.; Petrelli, F.; Ghidini, M.; Russo, A.; Passalacqua, R.; Barni, S. FOLFOXIRI Plus Bevacizumab as Conversion Therapy for Patients With Initially Unresectable Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis. JAMA Oncology 2017, 3, e170278–e170278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwaal, V.J.; van Ruth, S.; de Bree, E.; van Slooten, G.W.; van Tinteren, H.; Boot, H.; Zoetmulder, F.A. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2003, 21, 3737–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, D.; Lefevre, J.H.; Chevalier, J.; Brouquet, A.; Marchal, F.; Classe, J.M.; Ferron, G.; Guilloit, J.M.; Meeus, P.; Goéré, D.; et al. Complete cytoreductive surgery plus intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia with oxaliplatin for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2009, 27, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franko, J.; Ibrahim, Z.; Gusani, N.J.; Holtzman, M.P.; Bartlett, D.L.; Zeh, H.J. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion versus systemic chemotherapy alone for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer 2010, 116, 3756–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashin, P.H.; Mahteme, H.; Spång, N.; Syk, I.; Frödin, J.E.; Torkzad, M.; Glimelius, B.; Graf, W. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy for colorectal peritoneal metastases: A randomised trial. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2016, 53, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quénet, F.; Elias, D.; Roca, L.; Goéré, D.; Ghouti, L.; Pocard, M.; Facy, O.; Arvieux, C.; Lorimier, G.; Pezet, D.; et al. Cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus cytoreductive surgery alone for colorectal peritoneal metastases (PRODIGE 7): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. he Lancet. Oncology 2021, 22, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goéré, D.; Glehen, O.; Quenet, F.; Guilloit, J.M.; Bereder, J.M.; Lorimier, G.; Thibaudeau, E.; Ghouti, L.; Pinto, A.; Tuech, J.J.; et al. Second-look surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus surveillance in patients at high risk of developing colorectal peritoneal metastases (PROPHYLOCHIP-PRODIGE 15): a randomised, phase 3 study. The Lancet. Oncology 2020, 21, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, S.; Cai, G. Multidisciplinary Treatment for Colorectal Peritoneal Metastases: Review of the Literature. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2016, 2016, 1516259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A.; Lin, E.H.; Crane, C.H. Stage IV Colorectal Cancer. Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. 6th edition. BC Decker 2003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK13267/.

- Ghiasloo, M.; Pavlenko, D.; Verhaeghe, M.; Langenhove, Z.V.; Uyttebroek, O.; Berardi, G.; Troisi, R.I.; Ceelen, W. Surgical treatment of stage IV colorectal cancer with synchronous liver metastases: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2020, 46, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ströhlein, M.A.; Heiss, M.M. Limitations of the PRODIGE 7 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2021, 22, e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Driel, W.J.; Koole, S.N.; Sikorska, K.; van Leeuwen, J.H.S.; Schreuder, H.W.; Hermans, R.H.; de Hingh, I.H.; van der Velden, J.; Arts, H.J.; Massuger, L.F.; et al. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 378, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugarbaker, P.H.; der Speeten, K.V. The PRODIGE 7 randomized trial has 4 design flaws and 4 pharmacologic flaws and cannot be used to discredit other HIPEC regimens. Journal of gastrointestinal oncology 2021, 12, S129–S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, F.; Serrano, A.; Manzanedo, I.; Pérez-Viejo, E.; González-Moreno, S.; González-Bayón, L.; Arjona-Sánchez, A.; Torres, J.; Ramos, I.; Barrios, M.E.; et al. GECOP-MMC: phase IV randomized clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) with mytomicin-C after complete surgical cytoreduction in patients with colon cancer peritoneal metastases. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J. Current Uses of Mushrooms in Cancer Treatment and Their Anticancer Mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 10502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadava, D.; Still, D.W.; Mudry, R.R.; Kane, S.E. Effect of Ganoderma on drug-sensitive and multidrug-resistant small-cell lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Letters 2009, 277, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohretoglu, D.; Huang, S. Ganoderma lucidum Polysaccharides as An Anti-cancer Agent. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 18, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margret, A.A.; Mareeswari, R.; Kumar, K.A.; Jerley, A.A. Relative profiling of L-tryptophan derivatives from selected edible mushrooms as psychoactive nutraceuticals to inhibit P-glycoprotein: a paradigm to contest blood-brain barrier. BioTechnologia 2021, 102, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, X.; Wang, G.; Li, F.; Fang, S.; Zhou, S.; Ishiwata, A.; Tonevitsky, A.G.; Shkurnikov, M.; Cai, H.; Ding, F. Immunomodulatory Effect and Biological Significance of β-Glucans. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bai, Y.; Pei, J.; Li, D.; Pu, X.; Zhu, W.; Xia, L.; Qi, C.; Jiang, H.; Ning, Y. β-Glucan Combined With PD-1/PD-L1 Checkpoint Blockade for Immunotherapy in Patients With Advanced Cancer. Frontiers in pharmacology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, T.; Shiu, K.K.; Kim, T.W.; Jensen, B.V.; Jensen, L.H.; Punt, C.; Smith, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Benavides, M.; Gibbs, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab in Microsatellite-Instability–High Advanced Colorectal Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2020, 383, 2207–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, L.; Zhou, J.; Xu, X. The Possible Role of PD-1 Protein in Ganoderma lucidum-Mediated Immunomodulation and Cancer Treatment. Integrative cancer therapies 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, L.; Cheng, H.Z.; Shubai, L. Polysaccharide Peptide Induced Colorectal Cancer Cells Apoptosis by Down-Regulating EGFR and PD-L1 Expression. Iranian journal of pharmaceutical research : IJPR 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.I.; Choi, J.G.; Kim, J.H.; Li, W.; Chung, H.S. Blocking Effect of Chaga Mushroom (/textitInonotus oliquus) Extract for Immune Checkpoint CTLA-4/CD80 Interaction. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randeni, N.; Xu, B. New insights into signaling pathways of cancer prevention effects of polysaccharides from edible and medicinal mushrooms. Phytomedicine 2024, 132, 155875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xie, P. Ganoderic acid A holds promising cytotoxicity on human glioblastoma mediated by incurring apoptosis and autophagy and inactivating PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology 2019, 33, e22392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, T.P.; Chanda, W.; Padhiar, A.A.; Batool, S.; LiQun, S.; Zhong, M.T.; Huang, M. A Preclinical Evaluation of the Antitumor Activities of Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms: A Molecular Insight. Integrative cancer therapies 2018, 17, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Jang, J.E.; Mishra, S.K.; Lee, H.J.; Nho, C.W.; Shin, D.; Jin, M.; Kim, M.K.; Choi, C.; Oh, S.H. Ergosterol peroxide from Chaga mushroom (Inonotus obliquus) exhibits anti-cancer activity by down-regulation of the β-catenin pathway in colorectal cancer. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2015, 173, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ina, H.; Yoneda, M.; Kanda, M. Lentinan, A Shiitake Mushroom β-Glucan, Stimulates Tumor-Specific Adaptive Immunity through PD-L1 Down-Regulation in Gastric Cancer Cells. Medicinal chemistry 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyagarajan, A.; Jedinak, A.; Nguyen, H.; Terry, C.; Baldridge, L.A.; Jiang, J.; Sliva, D. Triterpenes From Ganoderma Lucidum Induce Autophagy in Colon Cancer Through the Inhibition of p38 Mitogen-Activated Kinase (p38 MAPK). Nutrition and Cancer 2010, 62, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.L.H.; Chik, S.C.C.; Lau, A.S.Y.; Chan, G.C.F. Coriolus versicolor and its bioactive molecule are potential immunomodulators against cancer cell metastasis via inactivation of MAPK pathway. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2023, 301, 115790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.L.; Meng, M.; Liu, S.B.; Wang, L.R.; Hou, L.H.; Cao, X.H. A chemically sulfated polysaccharide from Grifola frondos induces HepG2 cell apoptosis by notch1-NF-κB pathway. Carbohydrate polymers 2013, 95, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Dai, X.; Chen, G.; Ye, J.; Zhou, S. A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Study of Ganoderma lucidum (W.Curt.:Fr.) Lloyd (Aphyllophoromycetideae) Polysaccharides (Ganopoly) in Patients with Advanced Lung Cancer. International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms 2003, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Kang, X. Spore Powder of Ganoderma lucidum Improves Cancer-Related Fatigue in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Endocrine Therapy: A Pilot Clinical Trial. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM 2012. [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Lin, H.; Seidman, A.; Fornier, M.; D’Andrea, G.; Wesa, K.; Yeung, S.; Cunningham-Rundles, S.; Vickers, A.J.; Cassileth, B. A phase I/II trial of a polysaccharide extract from Grifola frondosa (Maitake mushroom) in breast cancer patients: immunological effects. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology 2009, 135, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israilides, C.; Kletsas, D.; Arapoglou, D.; Philippoussis, A.; Pratsinis, H.; Ebringerová, A.; Hříbalová, V.; Harding, S.E. In vitro cytostatic and immunomodulatory properties of the medicinal mushroom Lentinula edodes. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology 2008, 15, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasser, S.P.; Weis, A.L. Medicinal Properties of Substances Occurring in Higher Basidiomycetes Mushrooms: Current Perspectives (Review). International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms 1999, 1, 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, W.S.; Kim, D.J.; Chae, G.T.; Lee, J.M.; Bae, S.M.; Sin, J.I.; Kim, Y.W.; Namkoong, S.E.; Lee, I.P. Natural killer cell activity and quality of life were improved by consumption of a mushroom extract, Agaricus blazei Murill Kyowa, in gynecological cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2004, 14, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetland, G.; Tangen, J.M.; Mahmood, F.; Mirlashari, M.R.; Nissen-Meyer, L.S.H.; Nentwich, I.; Therkelsen, S.P.; Tjønnfjord, G.E.; Johnson, E. Antitumor, Anti-inflammatory and Antiallergic Effects of Agaricus blazei Mushroom Extract and the Related Medicinal Basidiomycetes Mushrooms, Hericium erinaceus and Grifola frondosa: A Review of Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, M.H.; Rashedi, I.; Keating, A. Immunomodulatory properties of coriolus versicolor: The role of polysaccharopeptide. Frontiers in Immunology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.L.; Yang, X.; Wan, J.M.F. The culture duration affects the immunomodulatory and anticancer effect of polysaccharopeptide derived from Coriolus versicolor. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 2006, 38, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.W.; Archambeau, J.O.; Gridley, D.S. Immunotherapy with Low-dose Interleukin-2 and a Polysaccharopeptide Derived from Coriolus versicolor. https://home.liebertpub.com/cbr 2009, 11, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejewski, T.; Sobocińska, J.; Pawlikowska, M.; Dzialuk, A.; Wrotek, S. Extract from the Coriolus versicolor Fungus as an Anti-Inflammatory Agent with Cytotoxic Properties against Endothelial Cells and Breast Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 9063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akagi, J.; Baba, H. PSK may suppress CD57(+) T cells to improve survival of advanced gastric cancer patients. International journal of clinical oncology 2010, 15, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadahiro, S.; Suzuki, T.; Maeda, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Kamijo, A.; Murayama, C.; Nakayama, Y.; Akiba, T. Effects of preoperative immunochemoradiotherapy and chemoradiotherapy on immune responses in patients with rectal adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Research 2010, 30, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hui, K.P.Y.; Sit, W.H.; Wan, J.M.F. Induction of S phase cell arrest and caspase activation by polysaccharide peptide isolated from Coriolus versicolor enhanced the cell cycle dependent activity and apoptotic cell death of doxorubicin and etoposide, but not cytarabine in HL-60 cells. Oncology Reports 2005, 14, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coriolus versicolor. Purported Benefits, Side Effects & More 2024. https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/herbs/coriolus-versicolor.

- J, J.; D, S. Novel medicinal mushroom blend suppresses growth and invasiveness of human breast cancer cells. International journal of oncology 2010, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtemariam, S. Trametes versicolor (Synn. Coriolus versicolor) Polysaccharides in Cancer Therapy: Targets and Efficacy. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.C.; Wu, P.; Park, S.; Wu, J.M. Induction of cell cycle changes and modulation of apoptogenic/anti-apoptotic and extracellular signaling regulatory protein expression by water extracts of I’m-Yunity (PSP). BMC complementary and alternative medicine 2006, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadrzejewski, T.; Pawlikowska, M.; SobociÅska, J.; Wrotek, S. Protein-Bound Polysaccharides from Coriolus Versicolor Fungus Disrupt the Crosstalk Between Breast Cancer Cells and Macrophages through Inhibition of Angiogenic Cytokines Production and Shifting Tumour-Associated Macrophages from the M2 to M1 Subtype. Cellular Physiology & Biochemistry 2020, 54, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.C.; Konerding, M.A.; Gaumann, A.; Groth, M.; Liu, W.K. Fungal polysaccharopeptide inhibits tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth in mice. Life Sciences 2004, 75, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Matsunaga, K.; Oguchi, Y. Antimetastatic effects of PSK (Krestin), a protein-bound polysaccharide obtained from basidiomycetes: an overview. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 1995, 4, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo, K.W.; Yue, G.G.L.; Ko, C.H.; Lee, J.K.M.; Gao, S.; Li, L.F.; Li, G.; Fung, K.P.; Leung, P.C.; Lau, C.B.S. In vivo and in vitro anti-tumor and anti-metastasis effects of Coriolus versicolor aqueous extract on mouse mammary 4T1 carcinoma. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology 2014, 21, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, R.; Yanagi, H.; Noda, M.; Yamamura, T.; Hashimoto-Tamaoki, T. Polysaccharide-K (PSK) inhibits distant metastasis in colorectal cancer dependent on ECA39. American Association for Cancer Research 2005, 65, 1538–7445. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Yan, P.; Lam, W.C.; Yao, L.; Bian, Z. Coriolus Versicolor and Ganoderma Lucidum Related Natural Products as an Adjunct Therapy for Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2019, 10, 420994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycomedicinals (Mushrooms) for Cancer. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/tools/mycomedicinals-mushrooms-for-cancer.asp.

- Medicinal Mushrooms (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. National Cancer Institute NIH, 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam/hp/mushrooms-pdq.

- Cizmarikova, M. The Efficacy and Toxicity of Using the Lingzhi or Reishi Medicinal Mushroom, Ganoderma lucidum (Agaricomycetes), and Its Products in Chemotherapy (Review). International journal of medicinal mushrooms 2017, 19, 861–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Beguerie, J.R.; yeun Sze, D.M.; Chan, G.C. Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi mushroom) for cancer treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Beguerie, J.R.; Sze, D.M.Y.; Chan, G.C. Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi mushroom) for cancer treatment. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, 2016, CD007731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phase II Clinical Trial Scheme of Ganoderma Lucidum Spore Powder for Postoperative Chemotherapy of Osteosarcoma, (ongoing clinical research). https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04319874.

- Oka, S.; Tanaka, S.; Yoshida, S.; Hiyama, T.; Ueno, Y.; Ito, M.; Kitadai, Y.; Yoshihara, M.; Chayama, K. A water-soluble extract from culture medium of Ganoderma lucidum mycelia suppresses the development of colorectal adenomas. Hiroshima Journal of Medical Sciences 2010, 59, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L. Ganoderma sinense polysaccharide: An adjunctive drug used for cancer treatment. Progress in molecular biology and translational science 2019, 163, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konno, S. Synergistic potentiation of D-fraction with vitamin C as possible alternative approach for cancer therapy. International journal of general medicine 2009, 2, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanba, H. Maitake D-fraction: Healing and Preventive Potential for Cancer. The Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine 1997, 12, https://orthomolecular.org/library/jom/1997/articles/1997-v12n01–p043shtml. [Google Scholar]

- Kodama, N.; Komuta, K.; Nanba, H. Can maitake MD-fraction aid cancer patients? Alternative Medicine Review 2002, 7, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tian, Q. Mushroom polysaccharide lentinan for treating different types of cancers: A review of 12 years clinical studies in China. Progress in molecular biology and translational science 2019, 163, 297–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheetham, P.; Lifton, D. The Patient’s Guide to AHCC Active Hexose Correlated Compound. The Clinically Proven Nutrient Supported By 25 Clinical Studies 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cowawintaweewat, S.; Manoromana, S.; Sriplung, H.; Khuhaprema, T.; Tongtawe, P.; Tapchaisri, P.; Chaicumpa, W. Prognostic improvement of patients with advanced liver cancer after active hexose correlated compound (AHCC) treatment. Asian Pacific Journal of Allergy and Immunology 2006, 24, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghoneum, M.; Wimbley, M.; Salem, F.; Mcklain, A.; Attallah, N.; Gill, G. Immunomodulatory and anticancer effects of active hemicellulose compound (AHCC). International Journal of Immunotherapy 1995, 11, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, Y.; Uhara, J.; Satoi, S.; Kaibori, M.; Yamada, H.; Kitade, H.; Imamura, A.; Takai, S.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Kwon, A.H.; et al. Improved prognosis of postoperative hepatocellular carcinoma patients when treated with functional foods: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Hepatology 2002, 37, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Lin, J.; He, Y.; Liu, S. Polysaccharide-Peptide from Trametes versicolor: The Potential Medicine for Colorectal Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Luo, H.; Hao, C.; Zeng, P.; Zhang, L. Preclinical and clinical studies of Coriolus versicolor polysaccharopeptide as an immunotherapeutic in China. Discovery Medicine 2017, 23, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eliza, W.L.; Fai, C.K.; Chung, L.P. Efficacy of Yun Zhi (Coriolus versicolor) on survival in cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Recent patents on inflammation & allergy drug discovery 2012, 6, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, H.; Kennedy, D.A.; Ishii, M.; Fergusson, D.; Fernandes, R.; Cooley, K.; Seely, D. Polysaccharide K and Coriolus versicolor extracts for lung cancer: a systematic review. Integrative cancer therapies 2015, 14, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, K.; Wieland, L.S.; Teng, L.; Jin, X.Y.; Storey, D.; Liu, J.P. Coriolus (Trametes) versicolor mushroom to reduce adverse effects from chemotherapy or radiotherapy in people with colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introduction to GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation). https://training.cochrane.org/introduction-grade.

- Oba, K.; Teramukai, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Matsui, T.; Kodera, Y.; Sakamoto, J. Efficacy of adjuvant immunochemotherapy with polysaccharide K for patients with curative resections of gastric cancer. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 2007, 56, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, J.; Morita, S.; Oba, K.; Matsui, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Nakazato, H.; Ohashi, Y. Efficacy of adjuvant immunochemotherapy with polysaccharide K for patients with curatively resected colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of centrally randomized controlled clinical trials. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 2006, 55, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitani, S.I.; Takashima, S. Efficacy of postoperative UFT (Tegafur/Uracil) plus PSK therapies in elderly patients with resected colorectal cancer. Cancer biotherapy & radiopharmaceuticals 2009, 24, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Maekawa, T.; Mikami, K.; Hoshino, S.; Shirakusa, T. Immunochemotherapy with PSK and fluoropyrimidines improves long-term prognosis for curatively resected colorectal cancer. Cancer biotherapy & radiopharmaceuticals 2008, 23, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, K.W.; Lam, C.L.; Yan, C.; Mak, J.C.; Ooi, G.C.; Ho, J.C.; Lam, B.; Man, R.; Sham, J.S.; Lam, W.K. Coriolus versicolor polysaccharide peptide slows progression of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Respiratory medicine 2003, 97, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, Y.; Nishimura, J.; Kato, T.; Ikeda, M.; Tsujie, M.; Hata, T.; Takemasa, I.; Mizushima, T.; Yamamoto, H.; Sekimoto, M.; et al. Phase III trial comparing UFT + PSK to UFT + LV in stage IIB, III colorectal cancer (MCSGO-CCTG). Surgery today 2018, 48, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niimoto, M.; Hattori, T.; Tamada, R.; Sugimachi, K.; Inokuchi, K.; Ogawa, N. Postoperative adjuvant immunochemotherapy with mitomycin C, futraful and PSK for gastric cancer. An analysis of data on 579 patients followed for five years. The Japanese journal of surgery 1988, 18, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torisu, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Ishimitsu, T.; Fujimura, T.; Iwasaki, K.; Katano, M.; Yamamoto, H.; Kimura, Y.; Takesue, M.; Kondo, M.; et al. Significant prolongation of disease-free period gained by oral polysaccharide K (PSK) administration after curative surgical operation of colorectal cancer. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 1990, 31, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitomi, T.; Tsuchiya, S.; Iijima, N.; Aso, K.; Suzuki, K.; Nishiyama, K.; Amano, T.; Takahashi, T.; Murayama, N.; Oka, H.; et al. Randomized, controlled study on adjuvant immunochemotherapy with PSK in curatively resected colorectal cancer. The Cooperative Study Group of Surgical Adjuvant Immunochemotherapy for Cancer of Colon and Rectum (Kanagawa). Diseases of the colon and rectum 1992, 35, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazato, H.; Koike, A.; Saji, S.; Ogawa, N.; Sakamoto, J. Efficacy of immunochemotherapy as adjuvant treatment after curative resection of gastric cancer. Study Group of Immunochemotherapy with PSK for Gastric Cancer. Lancet (London, England) 1994, 343, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogoshi, K.; Satou, H.; Isono, K.; Mitomi, T.; Endoh, M.; Sugita, M. Immunotherapy for esophageal cancer. A randomized trial in combination with radiotherapy and radiochemotherapy. Cooperative Study Group for Esophageal Cancer in Japan. American journal of clinical oncology 1995, 18, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T, T.; Y, Y. Protein-bound polysaccharide increases survival in resected gastric cancer cases stratified with a preoperative granulocyte and lymphocyte count. Oncology reports 2000, 7, 1157–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Nakazato, H.; Koike, A.; Takagi, H.; Saji, S.; Baba, S.; Mai, M.; Sakamoto, J.I.; Ohashi, Y. Long-term effect of 5-fluorouracil enhanced by intermittent administration of polysaccharide K after curative resection of colon cancer. A randomized controlled trial for 7-year follow-up. International journal of colorectal disease 2004, 19, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohwada, S.; Ikeya, T.; Yokomori, T.; Kusaba, T.; Roppongi, T.; Takahashi, T.; Nakamura, S.; Kakinuma, S.; Iwazaki, S.; Ishikawa, H.; et al. Adjuvant immunochemotherapy with oral Tegafur/Uracil plus PSK in patients with stage II or III colorectal cancer: a randomised controlled study. British journal of cancer 2004, 90, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shichinohe, T.; Komatsu, Y.; Akazawa, K.; Yuki, S.; Fukushima, H.; Ohno, K.; Nakamura, F.; Kusumi, T.; Morita, T.; Senmaru, N.; et al. Randomized phase III clinical study comparing postoperative UFT/LV,UFT+LV/UFT and UFT+LV+PSK/UFT+PSK as adjuvant therapy for curatively resected stage III colorectal cancer HGCSG-CAD study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2013, 31, 3638–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, H.; Shiraishi, T.; Okada, T.; Miyamae, Y.; Motegi, Y.; Shirabe, K.; Saeki, H. Adjuvant Chemotherapy With UFT/LV Versus UFT/LV Plus PSK in Stage II/III Colorectal Cancer. Anticancer Research 2024, 44, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veroniki, A.A.; Jackson, D.; Viechtbauer, W.; Bender, R.; Bowden, J.; Knapp, G.; Kuss, O.; Higgins, J.P.; Langan, D.; Salanti, G. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Research synthesis methods 2016, 7, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturella, G.; Ferraro, V.; Cirlincione, F.; Gargano, M.L. Medicinal Mushrooms: Bioactive Compounds, Use, and Clinical Trials. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łysakowska, P.; Sobota, A.; Wirkijowska, A. Medicinal Mushrooms: Their Bioactive Components, Nutritional Value and Application in Functional Food Production—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadar, E.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Pascale, C.; Sirbu, R.; Prasacu, I.; Negreanu-Pirjol, B.S.; Tomescu, C.L.; Ionescu, A.M. Natural Bio-Compounds from Ganoderma lucidum and Their Beneficial Biological Actions for Anticancer Application: A Review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekiz, E.; Oz, E.; El-Aty, A.M.A.; Proestos, C.; Brennan, C.; Zeng, M.; Tomasevic, I.; Elobeid, T.; Çadırcı, K.; Bayrak, M.; et al. Exploring the Potential Medicinal Benefits of Ganoderma lucidum: From Metabolic Disorders to Coronavirus Infections. Foods 2023, 12, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choong, Y.K.; Ellan, K.; Chen, X.D.; Mohamad, S.A. Extraction and Fractionation of Polysaccharides from a Selected Mushroom Species, Ganoderma lucidum: A Critical Review. Fractionation. IntechOpen 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoda, M.; Gonda, R.; Kasahara, Y.; Hikino, H. Glycan structures of ganoderans B and C, hypoglycemic glycans of ganoderma lucidum fruit bodies. Phytochemistry 1986, 25, 2817–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Siu, K.C.; Geng, P. Bioactive Ingredients and Medicinal Values of Grifola frondosa (Maitake). Foods 2021, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, N.; Murata, Y.; Asakawa, A.; Inui, A.; Hayashi, M.; Sakai, N.; Nanba, H. Maitake D-Fraction enhances antitumor effects and reduces immunosuppression by mitomycin-C in tumor-bearing mice. Nutrition 2005, 21, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Cheung, P.C. Advances in lentinan: Isolation, structure, chain conformation and bioactivities. Food Hydrocolloids 2011, 25, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentinan - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics 2016. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/lentinan.

- Fujii, H.; Nishioka, N.; Simon, R.R.; Kaur, R.; Lynch, B.; Roberts, A. Genotoxicity and subchronic toxicity evaluation of Active Hexose Correlated Compound (AHCC). Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2011, 59, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, M.S.; Park, H.J.; Maeda, T.; Nishioka, H.; Fujii, H.; Kang, I. The Effects of AHCC®, a Standardized Extract of Cultured Lentinura edodes Mycelia, on Natural Killer and T Cells in Health and Disease: Reviews on Human and Animal Studies. Journal of Immunology Research 2019, 2019, 3758576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, L. Coriolus versicolor polysaccharopeptide as an immunotherapeutic in China. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science 2019, 163, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cai, Z.; Mao, H.; Hu, P.; Li, X. Isolation and structure elucidation of polysaccharides from fruiting bodies of mushroom Coriolus versicolor and evaluation of their immunomodulatory effects. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 166, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wu, L.; Vinson, J.; Jing, Y.; Zhang, S.; et al. Research Progress on the Extraction, Structure, and Bioactivities of Polysaccharides from Coriolus versicolor. Foods 2022, 11, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Chisti, Y. Polysaccharopeptides of Coriolus versicolor: physiological activity, uses, and production. Biotechnology Advances 2003, 21, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, A.J.; Wu, Y.J.; Wu, L.M.; Zhang, L. Silymarin in cancer therapy: Mechanisms of action, protective roles in chemotherapy-induced toxicity, and nanoformulations. Journal of Functional Foods 2023, 100, 105384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.; Adeyeni, T.; San, K.; Heuertz, R.M.; Ezekiel, U.R. Curcumin Sensitizes Silymarin to Exert Synergistic Anticancer Activity in Colon Cancer Cells. Journal of Cancer 2016, 7, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Lin, J.K.; Chen, W.S.; Chiu, J.H. Anti-angiogenic effect of silymarin on colon cancer lovo cell line. Journal of Surgical Research 2003, 113, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, M.; Davoodvandi, A.; Nikmanzar, S.; Aghili, S.; Mirazimi, S.M.A.; Aschner, M.; Rashidian, A.; Hamblin, M.R.; Chamanara, M.; Naghsh, N.; et al. Silymarin (milk thistle extract) as a therapeutic agent in gastrointestinal cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 142, 112024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D, D.; J, X.; A, V.; V, A. Silymarin and Cancer: A Dual Strategy in Both in Chemoprevention and Chemosensitivity. Moluecules 2020, 25, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfanian, S.S.; Ansari, H.; Javanmard, S.H.; Amini, Z.; Hajigholami, A. The hepatorenal protective effects of silymarin in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies 2024, 24, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffar, H.M.; Al-Asmari, F.; Khan, F.A.; Rahim, M.A.; Zongo, E. Silymarin: Unveiling its pharmacological spectrum and therapeutic potential in liver diseases — A comprehensive narrative review. Food Science & Nutrition 2024, 12, 3097–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillessen, A.; Schmidt, H.H.J. Silymarin as Supportive Treatment in Liver Diseases: A Narrative Review. Adv Ther 2020, 37, 1279–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emadi, S.A.; Rahbardar, M.G.; Mehri, S.; Hosseinzadeh, H. A review of therapeutic potentials of milk thistle (Silybum marianum L.) and its main constituent, silymarin, on cancer, and their related patents. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2022, 25, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moezian, G.S.A.; Javadinia, S.A.; Sales, S.S.; Fanipakdel, A.; Elyasi, S.; Karimi, G. Oral silymarin formulation efficacy in management of AC-T protocol induced hepatotoxicity in breast cancer patients: A randomized, triple blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2022, 28, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, V.; Lupi, M.; Falcetta, F.; Forestieri, D.; D’Incalci, M.; Ubezio, P. Chemotherapeutic activity of silymarin combined with doxorubicin or paclitaxel in sensitive and multidrug-resistant colon cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2011, 67, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).