Submitted:

23 April 2025

Posted:

27 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Snails

2.2. Hypoxic Stress and Sample Collection

2.3. Metabolic Rates Measurement

2.4. Assay of Metabolic and Immune Enzymatic Activities

2.5. Assay of Gene Expression of Metabolic and Immune enzymes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

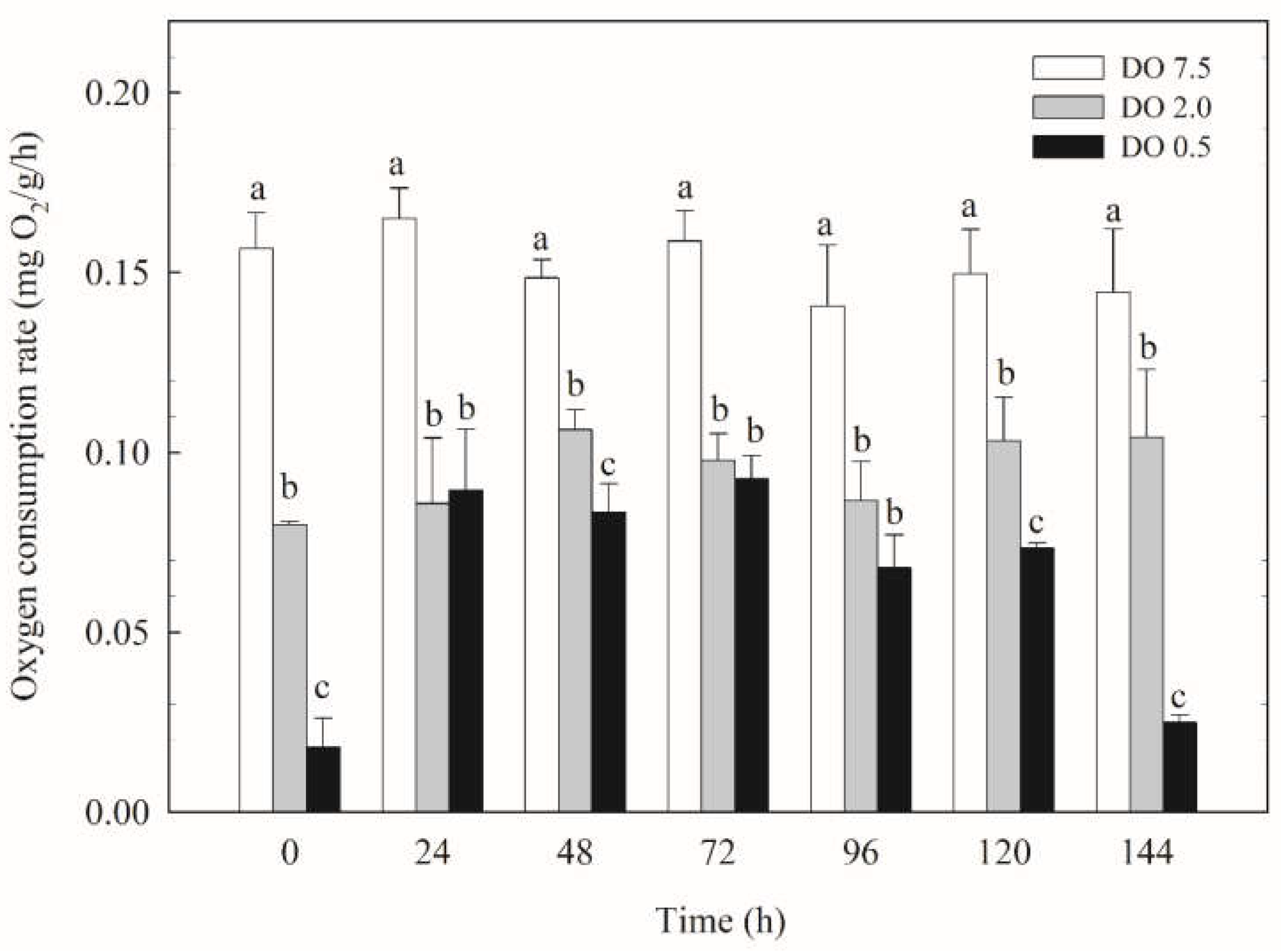

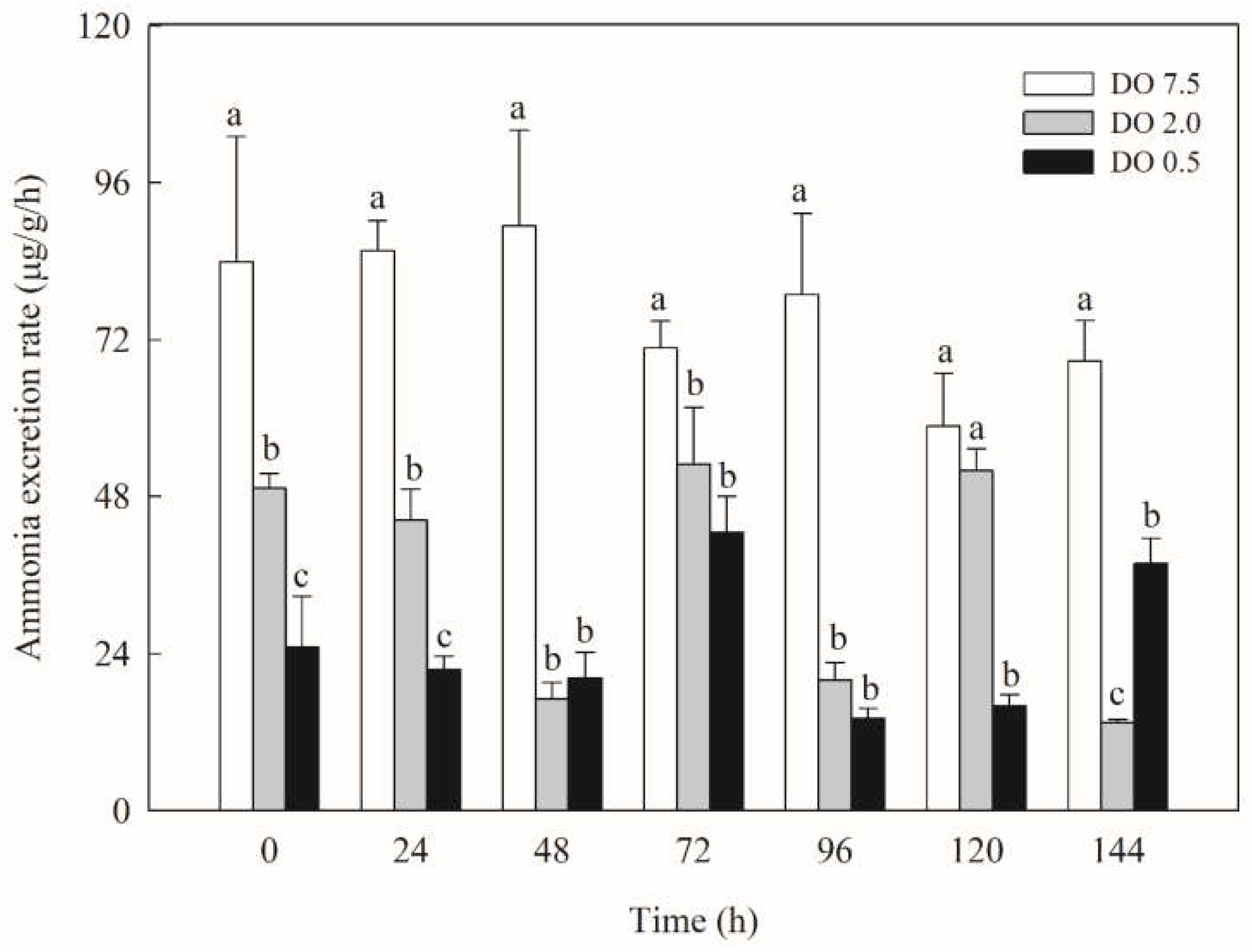

3.1. Metabolic Rates of B. Areolate During Prolonged Hypoxia

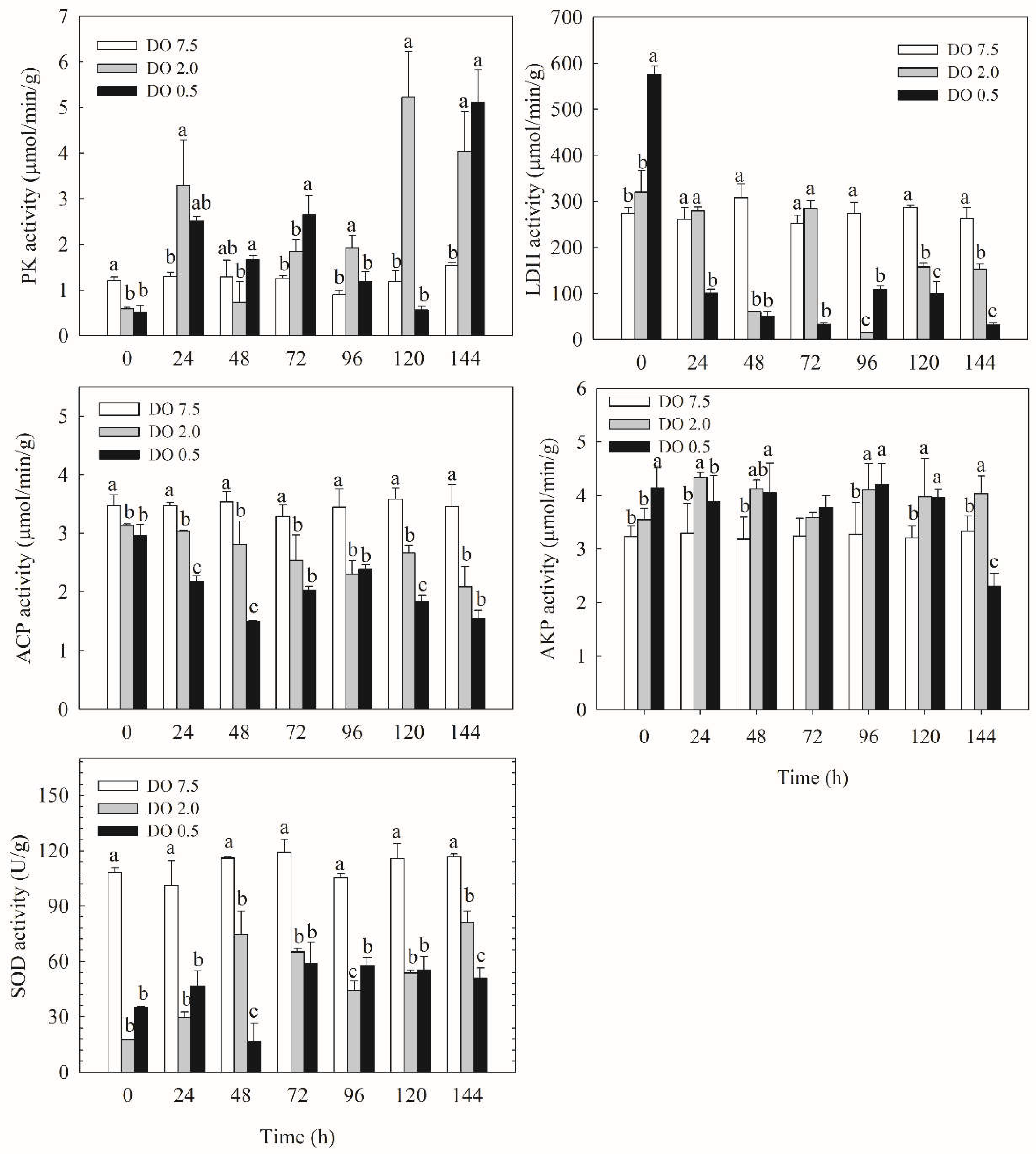

3.2. Metabolic and Immune Enzyme Activities of B. areolate Under Hypoxia Stress

3.3. Expression of Metabolic and Immune Enzyme Genes of B. Areolate Under Hypoxia Stress

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Prolonged Hypoxic Stress on Metabolism of B. areolate

4.2. Effects of Prolonged Hypoxic Stress on Enzymatic Activities and Gene Expression of B. Areolate

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schmidtko, S.; Stramma, L.; Visbeck, M. Decline in global oceanic oxygen content during the past five decades. Nature 2017, 542, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altieri, A.H.; Gedan, K.B. Climate change and dead zones. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 1395–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, E.T.; Breitburg, D.L. Eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, valve gape behavior under diel-cycling hypoxia. Mar. Biol. 2016, 163, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larade, K.; Storey, K.B. A profile of the metabolic responses to anoxia in marine invertebrates. Cell Mol. Resp. Stress. 2002, 3, 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Artigaud, S.; Lacroix, C.; Pichereau, V.; Flye-Sainte-Marie, J. Respiratory response to combined heat and hypoxia in the marine bivalves Pecten maximus and Mytilus spp. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2014, 175, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.J.; Riisgård, H.U. Relationship between oxygen concentration, respiration and filtration rate in blue mussel Mytilus edulis. J Oceanol. Limnol. 2018, 36, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.U.; Chen, H.; Gu, H.X.; Wang, T.; Dupont, S.; Kong, H.; Shang, Y.Y.; Wang, X.H.; Lu, W.Q.; Hu, M.H. Antioxidant responses of the mussel Mytilus coruscus co-exposed to ocean acidification, hypoxia and warming. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 162, 111869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross Ellington, W. Energy metabolism during hypoxia in the isolated, perfused ventricle of the whelk,Busycon contrarium conrad. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 1981, 142, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, F.; Falfushynska, H.I.; Timm, S.; Sokolova, I.M. Effects of hypoxia and reoxygenation on intermediary metabolite homeostasis of marine bivalves Mytilus edulis and Crassostrea gigas. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2020, 242, 110657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Jiang, P.Y.; Xia, F.Y.; Bai, Q.Q.; Zhang, X.M. Transcriptional and physiological profiles reveal the respiratory, antioxidant and metabolic adaption to intermittent hypoxia in the clam Tegillarca granosa. Comp. Biochem. Phys. D. 2024, 50, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickle, W.B.; Kapper, M.A.; Liu, L.L.; Gnaiger, E.; Wang, S.Y. Metabolic adaptations of several species of crustaceans and molluscs to hypoxia: tolerance and microcalorimetric studies. Biol. Bull. 1989, 177, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Huang, J.; Peng, J.Q.; Yang, C.Y.; Liao, Y.S.; Li, J.H.; Deng, Y.W.; Du, X.D. Effects of hypoxic stress on the digestion, energy metabolism, oxidative stress regulation, and immune function of the pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata martensii). Aquacult. Rep. 2022, 25, 101246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.C.; Liu, X.K.; Xu, R.; Liu, X.J.; Jiang, Q.C.; Song, X.Y.; Lu, Y.N.; Luo, X.L.; Yue, C.Y.; Qin, S.; Lü, W.G. Effects of light quality and intensity on the juvenile physiological metabolism of Babylonia areolate. Aquacult. Rep. 2023, 33, 101758. [Google Scholar]

- Chaitanawisuti, N.; Santhaweesuk, W.; Kritsanapuntu, S. Performance of the seaweeds Gracilaria salicornia and Caulerpa lentillifera as biofilters in a hatchery scale recirculating aquaculture system for juvenile spotted babylons (Babylonia areolata). Aquacult. Int. 2011, 19, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solorzano, L. Determination of ammonia in natural waters by the phenolhypochlorite method. Oceanol. Limnol. 1969, 14, 799–801. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.; Shen, Y.W.; Liu, Y.B.; Xia, W.W.; Hong, J.W.; Gan, Y.; Huang, J.; Luo, X.; Ke, C.H.; You, W.W. A high throughput method to assess the hypoxia tolerance of abalone based on adhesion duration. Aquaculture. 2024, 590, 741004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Sun, S.; Zhang, F.; Wang, M.X.; Li, M.N. Effects of hypoxia on survival, behavior, metabolism and cellular damage of Manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum). Plos One. 2019, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.M.; Plough, L.; Paynter, K. Intraspecific patterns of mortality and cardiac response to hypoxia in the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2023, 566, 151921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.E.; Haque, N.; Lee, J.S.; Park, H.S.; Rhee, J.S. Prolonged exposure to hypoxia inhibits the growth of Pacific abalone by modulating innate immunity and oxidative status. Aquat. Toxicol. 2020, 227, 105596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.M.; Kong, H.; Huang, X.Z.; Dupont, S.; Hu, M.H.; Storch, D.; Portner, H.O.; Lu, W.Q.; Wang, Y.J. Combined effects of short-term exposure to elevated CO2 and decreased O2 on the physiology and energy budget of the thick shell mussel Mytilus coruscus. Chemosphere. 2016, 155, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, F.; Wang, M.X.; Li, M.N.; Sun, S. Effects of hypoxia on survival, behavior, and metabolism of Zhikong scallop Chlamys farreri Jones et Preston 1904. J. Ocean. Limnol. 2020, 38, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Wang, T.; Li, L.; Zhang, G.F. Inducible variation in anaerobic energy metabolism reflects hypoxia tolerance across the intertidal and subtidal distribution of the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas). Mar. Environ. Res. 2018, 138, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pörtner, H.O.; Farrell, A.P. Physiology and climate change. Science 2008, 322, 690–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zwaan, A.; Cortesi, P.; van den Thillart, G.; Roos, J.; Storey, K.B. Differential sensitivities to hypoxia by two anoxiatolerant marine molluscs: a biochemical analysis. Mar. Biol. 1991, 111, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Shin, P.K.S.; Cheung, S.G. Comparisons of the metabolic responses of two subtidal nassariid gastropods to hypoxia and re-oxygenation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 82, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moullac, G.L.; Bacca, H.; Huvet, A.; Moal, J.; Pouvreau, S.; Wormhoudt, A.V. Transcriptional regulation of pyruvate kinase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in the adductor muscle of the oyster Crassostrea gigas during prolonged hypoxia. J. Exp. Zool. Part A. 2007, 307, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.T.; Wang, H.M.; Jiang, K.Y.; Yan, X.W. Transcriptome analysis reveals differential immune related genes expression in Ruditapes philippinarum under hypoxia stress: potential HIF and NF-κB crosstalk in immune responses in clam. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.X.; Wang, X. Lysine acetylation is an important post-translational modification that modulates heat shock response in the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H.; Wen, R.; Yang, N.; Zhang, T.N.; Liu, C.F. Roles of protein post-translational modifications in glucose and lipid metabolism: mechanisms and perspectives. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.T.; Colgan, S.P. Regulation of immunity and inflammation by hypoxia in immunological niches. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Mai, K.S.; Ma, H.M.; Wang, X.J.; Deng, D.; Liu, X.W.; Xu, W.; Liufu, Z.G.; Zhang, W.B.; Tan, B.P.; Ai, Q.H. Effects of dissolved oxygen on survival and immune responses of scallop (Chlamys farreri Jones et Preston). Fish Shellfish Immun. 2007, 22, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, F.; Sun, S. The survival and responses of blue mussel Mytilus edulis to 16-day sustained hypoxia stress. Mar. Environ. Res. 2022, 176, 105601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandel, N.S.; McClintock, D.S.; Feliciano, C.E.; Wood, T.M.; Melendez, J.A.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Schumacker, P.T. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1α during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 25130–25138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.H.; Wu, F.L.; Yuan, M.Z.; Li, Q.Z.; Gu, Y.D.; Wang, Y.J. Antioxidant responses of triangle sail mussel Hyriopsis cumingii exposed to harmful algae Microcystis aeruginosa and hypoxia. Chemosphere 2015, 139, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Denis, V.; Won, H.K.; Shin, K.S.; Lee, G.S.; Lee, T.K.; Yum, S.S. Expressions of oxidative stress-related genes and antioxidant enzyme activities in Mytilus galloprovincialis (bivalvia, mollusca) exposed to hypoxia. Zool. Stud. 2013, 52, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene names | Forward/reverse sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| LDH-F | GAGGTCGAGTCTTGGTCGTT |

| LDH-R | ACCGCTCTGCCAGTCTTCA |

| PK-F | GCATTTGTGCCATCTTGTA |

| PK-R | GCCATACCGTGTCCTCTAC |

| SOD-F | TGCCAAGGTCACATCAATC |

| SOD-R | ATGCCTACCGCACTCGTTT |

| ACP-F | AGCGTAGACACTGCTCGTA |

| ACP-R | GATGCTGGGAAACTGGGAC |

| AKP-F | GTTGTTGCTGGTAAAGATGA |

| AKP-R | CAAGTTTGGGCTGATGAAG |

| β-actin-F | GGTTCACCATCCCTCAAGTACCC |

| β-actin-R | GGGTCATCTTTTCACGGTTGG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).