Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Methodology

1.2. About the Real Estate Process

1.3. On the Duty to Conserve and Maintain

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Responsibilities for the Duty of Constructive Conservation and Maintenance During Service Life

2.2. Responsibilities for the Duty to Maintain and Conserve Installations During Service Life

2.3. Statutory Contracts: Property and the Facility Manager

3. Responsibility to Conserve and Maintain: Duty of the Property

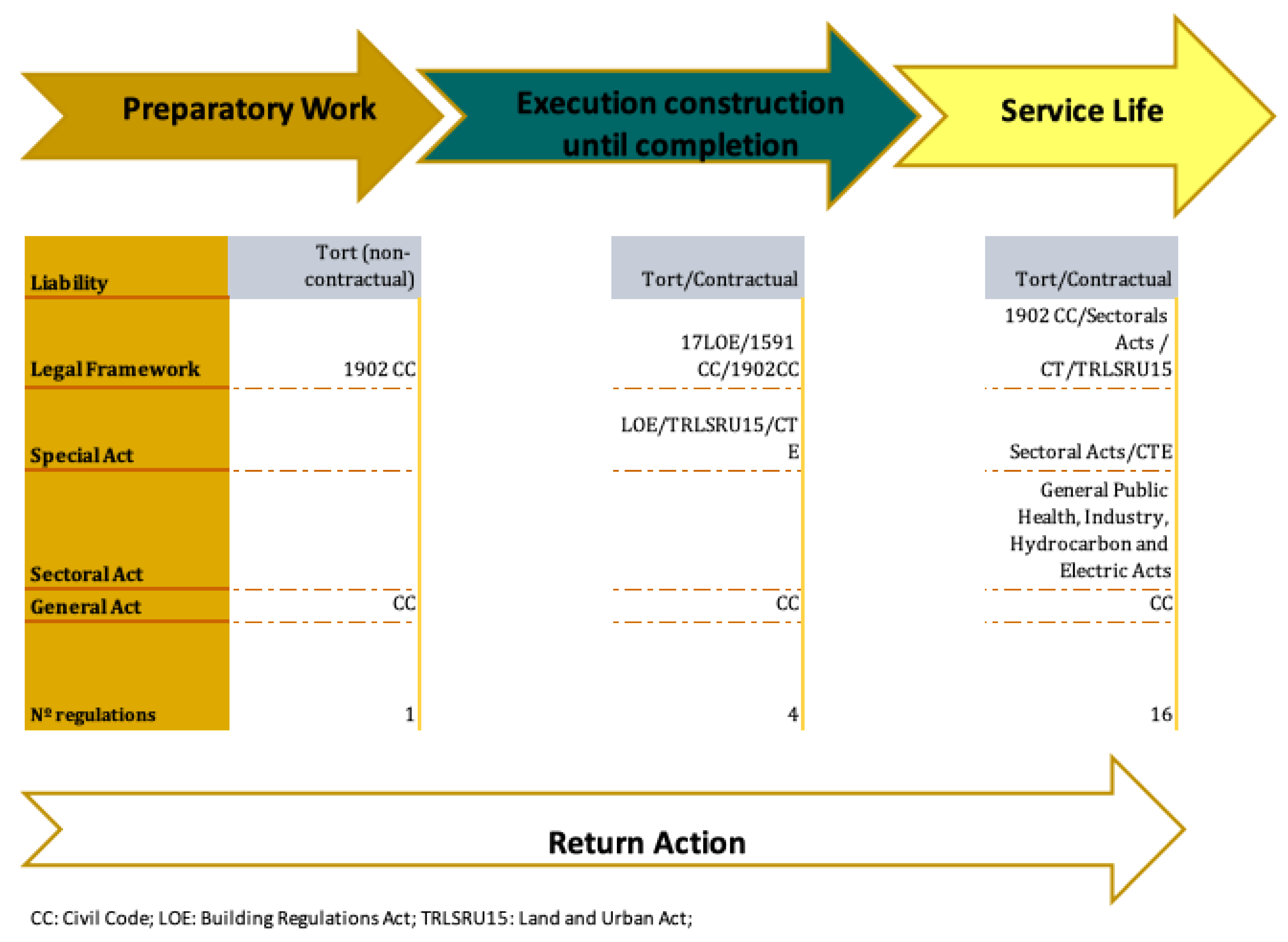

3.1. Responsible Parties and Liability Schemes for the Duty to Conserve and Maintain

3.2. The Facility Manager and Their Contractual Relationships with the Property

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gil Sebastián, J.J.; Soler Severino, M.J. Real Estate Owners’Early Thoughts on Lean IPD Implementation in Spain. Buildings 2025, 15, 626, 12-20. [CrossRef]

- Carnaby King, J. Explaning Housing Policy Change through Discursive Institutionalism. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 468. [CrossRef]

- Real Decreto Legislativo 1/2004, 5 Marzo, por el que se Aprueba el Texto Refundido la Ley Catastro Inmobiliario. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 58. 08 de Marzo de 2004. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2004-4163 (accessed on 10 March 2025). Royal Legislative Decree 1/2004, of March 5, approving the consolidated text of the Law on the Real Estate Cadastre.

- Real Decreto de 24 de julio de 1889 por el que se publica el Código Civil. Gaceta de Madrid, 206. 16 de agosto de 1889. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1889-4763 (accessed on 10 March 2025). Royal Decree of 24 July 1889 publishing the Civil Code.

- Ley 38/1999, de 5 de Noviembre, de Ordenación de la Edificación. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 266. 06 de Noviembre de 1999. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1999-21567 (accessed on 12 March 2025). Law 38/1999, of 5 November, on Building Regulation.

- Real Decreto 314/2006, de 17 de Marzo, por el que se Aprueba el Código Técnico de la Edificación. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 74. 28 de Marzo de 2006. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2006/3/17/314 (accessed on 15 January 2025). Royal Decree 314/2006, 17 March, approving the Technical Building Code.

- UNE-EN ISO 19650-1; Organización y Digitalización la Información en Obras Edificación e Ingeniería Civil que Utilizan BIM. Gestión de la Información al Utilizar BIM.; Asociación Española de Normalización: Madrid, Spain, 2020. Organization and Digitization of Information in Building and Civil Engineering Works Using BIM. Information Management Using BIM.

- Constitución Española. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 311. 29 de Diciembre de 1978. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1978-31229 (accessed on 2 March 2025). Spanish Constitution.

- Real Decreto Legislativo 7/215, 30 Octubre, por el se Aprueba el Texto Refundido la Ley Suelo y Rehabilitación Urbana. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 261. 31 de Enero de 2015. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-215-11723 (accessed on 2 March 2025). Royal Legislative Decree 7/2015, of October 30, approving the consolidated text of the Land and Urban Rehabilitation.

- Real Decreto 2187/1978, 23 Junio, por el que se Aprueba el Reglamento Disciplina Urbanístico para el Desarrollo y Aplicación la Ley sobre Régimen Suelo y Ordenación Urbana. Boletín Oficial l Estado, 223. 18 de septiembre de 1978. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1978-23852 (accessed on 10 March 2025). Royal Decree 2187/1978, 23 June, approving the Urban Planning Discipline Regulation for the Development and Application of the Law on Land Regime and Urban Planning.

- Melón Muñoz, A.; Martín Nieto, P. Memento Práctico Urbanismo; Lefebvre-El Derecho: Madrid, Spain, 2018, 5587. Urban Planning Practical Memento.

- Ley 29/1994, 24 Noviembre, Arrendamientos Urbanos. Boletín Oficial l Estado, 282. 25 de Noviembre de 1994. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1994-2603 (accessed on 16 February 2025). Law 29/1994, of 24 November, on Urban Leases.

- Melón Muñoz, A.; Martín Nieto, P. Memento Práctico Urbanismo; Lefebvre-El Derecho: Madrid, Spain, 2018, 1482. Urban Planning Practical Memento.

- Melón Muñoz, A.; Martín Nieto, P. Memento Práctico Urbanismo; Lefebvre-El Derecho: Madrid, Spain, 2018, 5592. Urban Planning Practical Memento.

- Herbosa Martínez, I. La Responsabilidad Extracontractual por Ruina de los Edificios; después la Ley 38/1999, 5 noviembre, sobre Ordenación la Edificación; Cívitas Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2002,65. Non-Contractual Liability for Building Collapse; after Law 38/1999, 5 November, on Building Regulation.

- Lefebvre, F. Memento Inmobiliario. 2023, 1559. Available online: https://online.elrecho.com/seleccionProducto.do?producto=UNIVERSAL#%2FpresentarMemento.do%3Fnref%3D7dbdbbb5%26producto%3DUNIVERSAL%26marginal%3D7145%26rnd%3D0.7604059475520835 (accessed on 10 September 2024). Real Estate Memento.

- Real Decreto 355/2024, de 2 de Abril, por el que se Aprueba la Instrucción Técnica Complementaria ITC AEM 1 “Ascensores”, que Regula la Puesta en Servicio, Modificación, Mantenimiento e Inspección de los Ascensores, así Como el Incremento de la Seguridad. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 91. 13 de Abril de 2024. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2024-7258 (accessed on 25 January 2025). Royal Decree 355/2024, of April 2, approving the Complementary Technical Instruction of Elevators ITC AEM 1, regulating the commissioning, modification, maintenance, and inspection of elevators, as well as the enhancement of safety.

- Ley 21/1992, 16 Julio, Industria. Boletín Oficial l Estado, 176. 23 de Julio de 1992. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1992-17363 (accessed on 8 January 2025). Law 21/1992, of July 16, on Industry.

- Real Decreto 842/2002,de 2 de Agosto, por el que se Aprueba el Reglamento Electrotécnico para Baja Tensión. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 224. 2002 de Septiembre de 2002. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2002/08/02/842 (accessed on 10 January 2025). Royal Decree 842/2002, of August 2, approving the Low Voltage Electrotechnical Regulation.

- Real Decreto 1054/2002, de 11 de Octubre, por el que se Aprueba el Proceso de Evaluación Para el Registro, Autorización y Comercialización de Biocidas. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 247. 15 de octubre de 2002. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2002-19923 (accessed on 12 January 2025). Royal Decree 1054/2002, 11 October, approving the Evaluation Process for the Registration, Authorization, and Commercialization of Biocides.

- Real Decreto 487/2022, de 21 de Junio, por el que se Establecen los Requisitos Sanitarios para la Prevención y Control de la Legionelosis. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 148. 21 de Junio de 2022. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2022/06/22/pdfs/BOE-A-2022-10297.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025). Royal Decree 487/2022, of June 21, establishing the sanitary requirements for the prevention and control of Legionellosis.

- Real Decreto 865/2003, de 4 de Julio, por el se Establecen los Criterios Higiénico Sanitarios Para la Prevención y el Control de la Legionelosis. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 171. 18 de Julio de 2003. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-203-14408 (accessed on 15 January 2025). Royal Decree 865/2003, of July 4, establishing the hygienic-sanitary criteria for the prevention and control of Legionellosis.

- Ley 14/1986, 25 abril, General Sanidad. Boletín Oficial l Estado, 102. 29 de Abril de 1986. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1986-10499 (accessed on 15 December 2024). Law 14/1986, of 25 April, General Health Law.

- Ley 33/2011, de 4 de Octubre, General de Salud Pública. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 240. 5 de 0ctubre de 2011. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-211-15623 (accessed on 15 January 2025). Law 33/2011, of 4 October, General Public Health Law.

- Documento Básico, S.I. Seguridad en caso de Incendio. Ministerio de Vivienda y Agenda Urbana. 2019. Available online: https://www.codigotecnico.org/pdf/Documentos/SI/DBSI.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025). Basic Document Fire Safety (SI).

- Real Decreto 513/2017, de 22 de Mayo, por el que se Aprueba el Reglamento de Instalaciones de Protección Contra Incendios. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 139. 12 de Junio de 2017. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-217-6606 (accessed on 27 January 2025). Royal Decree 513/2017, of May 22, approving the Regulation on Fire Protection Installations.

- Documento Básico HS Salubridad. Ministerio Vivienda y Agenda Urbana. 2022. Available online: https://www.codigotecnico.org/pdf/Documentos/HS/DBHS.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025). Basic Document Health and Hygiene (HS). Ministry of Housing and Urban Agenda.

- Real Decreto 1027/2007, 20 Julio, por el que se Aprueba el Reglamento Instalaciones Térmicas en los Edificios. Boletín Oficial l Estado, 207. 29 de Agosto de 2007. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2007-15820 (accessed on 15 January 2025). Royal Decree 1027/2007, 20 July, approving the Regulation on Thermal Installations in Buildings.

- Real Decreto 337/2014, de 9 de Mayo, por el que Aprueban el Reglamento Sobre Condiciones Técnicas y Garantías de Seguridad en Instalaciones Eléctricas de Alta Tensión y sus Instrucciones Técnicas Complementarias ITC-RAT 01 a 23. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 139. 09 de junio de 2014. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2014-6084 (accessed on 10 March 2025). Royal Decree 337/2014, 9 May, approving the Regulation on Technical Conditions and Safety Guarantees in High Voltage Electrical Installations and its Complementary Technical Instructions 01 to 23 (ITC-RAT).

- Ley 24/2013, de 23 de Diciembre, del Sector Eléctrico. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 310. 27 de Diciembre de 2013. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2013-13645 (accessed on 10 March 2025). Law 24/2013, of 23 December, on the Electricity Sector.

- Real Decreto 919/2006, de 28 de Julio Aprueba el Reglamento Técnico de Distribución y Utilización de Combustibles Gaseosos y sus Instrucciones Técnicas Complementarias ICG 01 a 11. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 211. 04 de Septiembre de 2006. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2006-15345 (accessed on 10 March 2025). Royal Decree 919/2006, of 28 July, approving the Technical Regulation for the Distribution and Use of Gaseous Fuels and its Complementary Technical Instructions 01 to 11 (ICG).

- Ley 34/1998, de 7 de Octubre, del Sector de Hidrocarburos. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 241. 08 de Octubre de 1998. Available online: https://boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1998-23284 (accessed on 10 March 2025). Law 34/1998, of 7 October, on the Hydrocarbon Sector.

- Bercovitz Rodríguez-Cano, R. Manual de Derecho Civil; Contratos; Bercal: Madrid, Spain, 2021, 28. Civil Law Manual; Contracts.

- Ley 50/1980, 8 Octubre, Contrato Seguro. Boletín Oficial l Estado, 250. 17 de Octubre de 1980. Available online: https://boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1980-2251 (accessed on 3 October 2025). Law 50/1980, of 8 October, on Insurance Contracts.

- Lasarte, C. Curso de Derecho Civil Patrimonial. Introducción al Derecho; Editorial Tecnos (Grupo Anaya, S.A.): Madrid, Spain, 2021, 320. Course on Civil Patrimonial Law. Introduction to Law.

- Humero Martín, A. Arquitectura Legal y Valoraciones Inmobiliarias, 7th ed.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2023, 221. Legal Architecture and Real Estate Evaluation.

- Aranda Rodríguez, R. Guía de Derecho Civil. Teoría y Práctica Tomo III. In Teoría General del Contrato y Contratos en Particular; Aranzadi: Pamplona, Spain, 2013, 384. Guide to Civil Law. Theory and Practice Volume III. In General Theory of Contract and Specific Contracts.

- Díez-Picazo y Antonio Gullón, L. Sistema de Derecho Civil; Tecnos (Grupo Anaya, S.A.): Madrid, Spain, 2018, 147. Civil Law System.

- Bercovitz Rodríguez-Cano, R. Manual de Derecho Civil; Contratos; Bercal: Madrid, Spain, 2021, 255. Civil Law Manual; Contracts.

- Aranda Rodríguez, R. Guía de Derecho Civil. Teoría y Práctica Tomo III. In Teoría General del Contrato y Contratos en Particular; Aranzadi: Pamplona, Spain, 2013, 403. Guide to Civil Law. Theory and Practice Volume III. In General Theory of Contract and Specific Contracts.

- Bercovitz Rodríguez-Cano, R. Manual de Derecho Civil; Contratos; Bercal: Madrid, Spain, 2021, 266. Civil Law Manual; Contracts.

- Díez-Picazo y Antonio Gullón, L. Sistema de Derecho Civil; Tecnos (Grupo Anaya, S.A.): Madrid, Spain, 2018, 127. Civil Law System.

- Díez-Picazo y Antonio Gullón, L. Sistema de Derecho Civil; Tecnos (Grupo Anaya, S.A.): Madrid, Spain, 2018, 176. Civil Law System.

- Lasarte, C. Curso de Derecho Civil Patrimonial. Introducción al Derecho; Editorial Tecnos (Grupo Anaya, S.A.): Madrid, Spain, 2021, 329.

- Díez-Picazo y Antonio Gullón, L. Sistema de Derecho Civil; Tecnos (Grupo Anaya, S.A.): Madrid, Spain, 2018, 174. Civil Law System.

- Llamas Pombo, E. Comentario a la sentencia del Tribunal Supremo de 24 de mayo de 2018(299/2018). Explosión de gas y responsabilidad de la empresa suministradora. In Comentarios a las Sentencias de Unificación de Doctrina (Civil y Mercantil); Yzquierdo Tolsada, M.; Volume 10; 406. Available online:https://www.boe.es/biblioteca_juridica/comentarios_sentencias_unificacion_doctrina_civil_y_mercantil/abrir_pdf.php?id=COM-D-2018-27 (accessed on 1 January 2025). Commentary on Supreme Court Judgment of 24 May 2018 (299/2018). Gas Explosion and Supplier Company Liability. In Comments on Unification of Doctrine Judgments (Civil and Commercial).

- Hoya Coromina, J. Hacia una visión integradora de la responsabilidad civil. In Las Responsabilidad Civil y su Problemática Actual; Moreno Martínez, J.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2007, 384. Towards an Integrative Vision of Civil Liability. In Civil Liability and Its Current Challenges.

- Prabowo, B.N.; Temeljotov Salaj, A.; Lohne, J. Identifying Urban Heritage Facility Management Support Services Considering World Heritage Sites. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 52. [CrossRef]

- Villa, V.; Gioberti, L.; Domaneschi, M; C.N. Conceptual Advantages in Infrastructure Maintenance and Management Using Smart Contracts: Reducing Costs and Improving Resilience. Buildings 2025, 15, 680. [CrossRef]

| Damage | Type of Liability | General Legal Framework | Responsible Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Damage to third parties due to conservation duty | Subjective liability (without fault) | Articles 1902, 1907, and 1909 CC | Owner, user |

| Installation | Special Regulation | Sectoral Law |

|---|---|---|

| Elevators | Royal Decree 355/2024, of April 2, approving Complementary Technical Instruction of Elevators 1 (ITC AEM 1) regulating the commissioning, modification, maintenance, and inspection of elevators, as well as enhancement safety (2024) [17]. | Law 21/1992, of July 16, on Industry (1992) [18]. |

| Low-voltage installation | Royal Decree 842/2002, of August 2, approving the Low Voltage Electrotechnical Regulation 2002, and the Technical Instruction of Low Voltage (ITC-BT 03) [19]. | Law 21/1992, of July 16, on Industry (1992) [18]. |

| Prevention and control of legionellosis and indoor air quality | Royal Decree 1054/2002, of October 11, approving the evaluation process for the registration, authorization, and commercialization of biocides (2002) [20]; Royal Decree 487/2022, of June 21, establishing sanitary requirements for the prevention and control of legionellosis (2022) [21]; Royal Decree 865/2003, of July 4, establishing hygienic–sanitary criteria for the prevention and control of legionellosis (2003) [22]. Regulation repealed, but its liability framework (up until 2023) is referred to in this article | Law 14/1986, of April 25, General Health Law (1986) [23]; Law 33/2011, of October 4, General Public Health Law (2011) [24]; Law 21/1992, of July 16, on Industry (1992) [18]. |

| Fire detection and extinction | Basic Document of Fire Safety (SI) in case of fire (2019) [25]; Royal Decree 314/2006, of March 17, approving the Technical Building Code (2006) [6]; Royal Decree 513/2017, of May 22, approving the Regulation on Fire Protection Installations (2017)—Tables I and II of Section 1, as well as Table III of Section 2, in annex II [26]. | Law 21/1992, of July 16, on Industry (1992) [18]. |

| Plumbing | Basic Document Health and Hygiene (2022) (HS), HS 4 and HS 5 [27]; Royal Decree 314/2006, of March 17, approving the Technical Building Code (2006) [6]; Royal Decree 1054/2002, of October 11, approving the evaluation process for the registration, authorization, and commercialization of biocides (2002) [20]; which is applicable to plumbing by virtue of Article 7.3 CTE HS 4. |

Law 14/1986, of April 25, General Health Law (1986) [23]; Law 33/2011, of October 4, General Public Health Law (2011) [24]; Law 21/1992, of July 16, on Industry (1992) [18]. |

| Sewerage system | Basic Document Health and Hygiene (2022)—documents HS-4 and HS-5 [27]; Royal Decree 314/2006, of March 17, approving the Technical Building Code (2006) ) [6]. | Law 21/1992, of July 16, on Industry (1992) [18]. |

| Air conditioning and ventilation | Royal decree 1027/2007, of July 20, approving the Regulation on Thermal Installations in Buildings (2007) [28]. | Law 21/1992, of July 16, on Industry (1992) [18]. |

| Gas thermal installations | Royal decree 1027/2007, of July 20, approving the Regulation on Thermal Installations in Buildings (2007) [28]. | Law 21/1992, of July 16, on Industry (1992) [18]. |

| Installation | Owner, Holder, User | Maintenance Company |

|---|---|---|

| Elevators | Subscribe to a maintenance contract; prevent the operation of the installation when safety conditions are not met; communicate defects to the maintenance company; and request periodic inspections in sufficient time. Likewise, they will be responsible, according to the doctrine of culpa in vigilando, for the hiring and work of the “conservator” company. | Establishment of alternative measures to avoid setting up shelters or spaces that are free of buildings. The maintenance company has the duty to respond to the work entrusted to them for maintenance. |

| Low-voltage installation | Responsible for the adequate maintenance of installations, according to article 19 of “Low Voltage Regulation”, as well as breaking seals, according to article 20 of “Low Voltage Regulation” [19]. | Responds to their non-compliance; i.e., the frequencies of performing inspections or informing the installation holder. |

| Prevention and control of legionellosis and indoor air quality | Responsible for the installation.. | Among other things, they are responsible for the work performed. |

| Fire detection and extinction | The regulation differentiates between the property responsible for the installation—“the property responsible for maintenance operations”—and the maintenance responsible; these are figures that may be the same person. Thus, no express attribution of responsibility is established, so the property responsible could adopt the position of guarantor in the most favorable position or the installation holder in its broadest interpretation. | Obligations range from minimum maintenance activities to others such as performing corrective maintenance at the request of the installation holder; informing the installation holder that installations comply with the operation or current regulations; preserving performed maintenance; issuing certificates for periodic maintenance; notifying the review schedule; inspecting extinguishers. |

| Plumbing | Responsible for the installation. | Among other things, they are responsible for the work performed. |

| Sewerage system | Duty of diligence, Law 21/1992 on Industry [18]. | Responsible. |

| Air conditioning and ventilation | General responsibility is established, regarding both maintenance and the adequacy of use, from the moment that “provisional acceptance is performed”. Three obligations of the holder and user are listed, numerus clausus—adequate maintenance, performing inspections, and preserving the corresponding documentation. | Correct execution of maintenance. |

| Gas thermal installations | Responsible for the installation. | Correct execution of maintenance. |

| Damage | Type of Liability | General Legal Framework | Responsible Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Damage to third parties by real estate due to maintenance duty | Subjective liability with quasi-objective application (without fault) | Articles 1902, 1907, and 1909 CC | Owner, holder, user, maintenance company |

| Installation | Special Regulation | Sectoral Law |

|---|---|---|

| High- and medium-voltage electrical networks | Royal Decree 337/2014, of May 9, approving the Regulation on Technical Conditions and Safety Guarantees in High-Voltage Electrical Installations and its Complementary Technical Instructions 01 to 23( ITC-RAT) [29]. | Electric Sector Act (Law 24/2013, of December 23, on the Electric Sector) [30]. |

| Territorial distribution and storage of gas | Royal Decree 919/2006, of July 28, approving the technical regulation for the distribution and use of gaseous fuels and its complementary technical instructions 01 to 11(ICG ) [31]. | Hydrocarbon Sector Act (Law 34/1998, of October 7, on the Hydrocarbon Sector) [32]. Law 21/1992, of July 16, on Industry) [18]. |

| Damage | Type of Liability | General Legal Framework | Responsible Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Damage to third parties by territorial installations due to maintenance duty | Objective liability (without fault) | Article 1902 CC | Installation holder |

| Responsibility | Diligence | Matter |

|---|---|---|

| Owner/User | Constructive conservation | |

| Owner/User | Sewerage system | |

| Installation holder or | User/Owner | Elevators; low-voltage installations; prevention and control of legionellosis and indoor air quality; fire protection; air conditioning and ventilation; gas thermal installations; plumbing and hot water |

| Installation holder | User/Owner | High- and medium-voltage electrical networks; territorial distribution and storage of gas |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).