1. Introduction

Dengue is an acute viral disease caused by one of the four dengue virus serotypes (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4), transmitted to humans through the bite of mosquitoes of the genus

Aedes, primarily

Aedes aegypti [

1]. Factors such as unplanned urbanization, human migration, and climate change have facilitated the spread of both the vector and the virus [

2]. Annually, it is estimated that 390 million infections occur across 129 countries, with approximately four billion people at risk [

3]. Between 75% and 80% of those infected are asymptomatic, suggesting significant underreporting of cases. During epidemic peaks, nearly one million individuals require hospitalization, and severe forms of the disease cause approximately 25,000 deaths annually, with case fatality rates ranging from 1% to 5% [

4]. In response to the exponential increase in cases over the past two decades, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared dengue a Level 3 emergency in 2023 [

5].

Dengue exhibits a wide range of clinical manifestations and can rapidly progress from mild febrile illness to severe and life-threatening forms [

6]. While most infections are self-limiting and present as dengue fever, a significant proportion can advance to severe complications, such as dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) or dengue shock syndrome (DSS) [

6]. These severe forms are often associated with multi-organ failure and high mortality rates [

7]. The unpredictable and dynamic nature of the disease, coupled with its growing global incidence, underscores the urgent need to strengthen surveillance, prevention, and clinical management strategies, particularly in highly affected regions [

7].

Despite significant research, the immunopathological mechanisms underlying the development of DHF remain incompletely understood. It has been proposed that DHF may result from dysregulated lymphocytic and humoral responses, associated with phenomena such as original antigenic sin and antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) [

8]. These mechanisms may explain both the clinical severity and the increased vascular permeability characteristic of DHF in patients experiencing secondary infections [

8]. Additionally, the cytokine storm triggered by macrophages, dendritic cells, and mast cells appears to be a key driver of plasma leakage [

8]. Previous studies have shown that the virus does not directly cause endothelial damage; instead, cytokines such as Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukins (IL-1β, and IL-6) contribute to thrombocytopenia and immune hyperactivation. These cytokines, together with non-structural protein 1 (NS1) immune complexes, induce endothelial dysfunction and promote vascular permeability, suggesting that the inflammatory microenvironment and paracrine processes play central roles in severe dengue pathophysiology [

9].

A recently highlighted paracrine mediator in dengue is extracellular vesicles (EVs), which have emerged as critical players in dengue pathogenesis, contributing to immune modulation, endothelial damage, and viral transmission [

10]. EVs are small membrane-bound structures released by eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells in response to stimuli such as cellular stress and apoptosis [

1]. These vesicles play crucial roles in intercellular communication, molecular transport, and immune system modulation, and they can be detected in body fluids, underscoring their potential as biomarkers [

1].

In this context, this review aim to synthesize and analyze the latest research on the role of EVs in dengue pathogenesis. Specifically, it will address their ability to elucidate the physiological mechanisms underlying vascular permeability, plasma leakage, and immune evasion. Additionally, their potential impact on the development of clinically relevant biomarkers—such as microRNAs contained within EVs—will be explored, emphasizing on their use for patient monitoring and clinical classification through advanced bioinformatics tools. Finally, potential therapeutic strategies based on current knowledge of EVs will be discussed, highlighting their significance in managing severe dengue.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

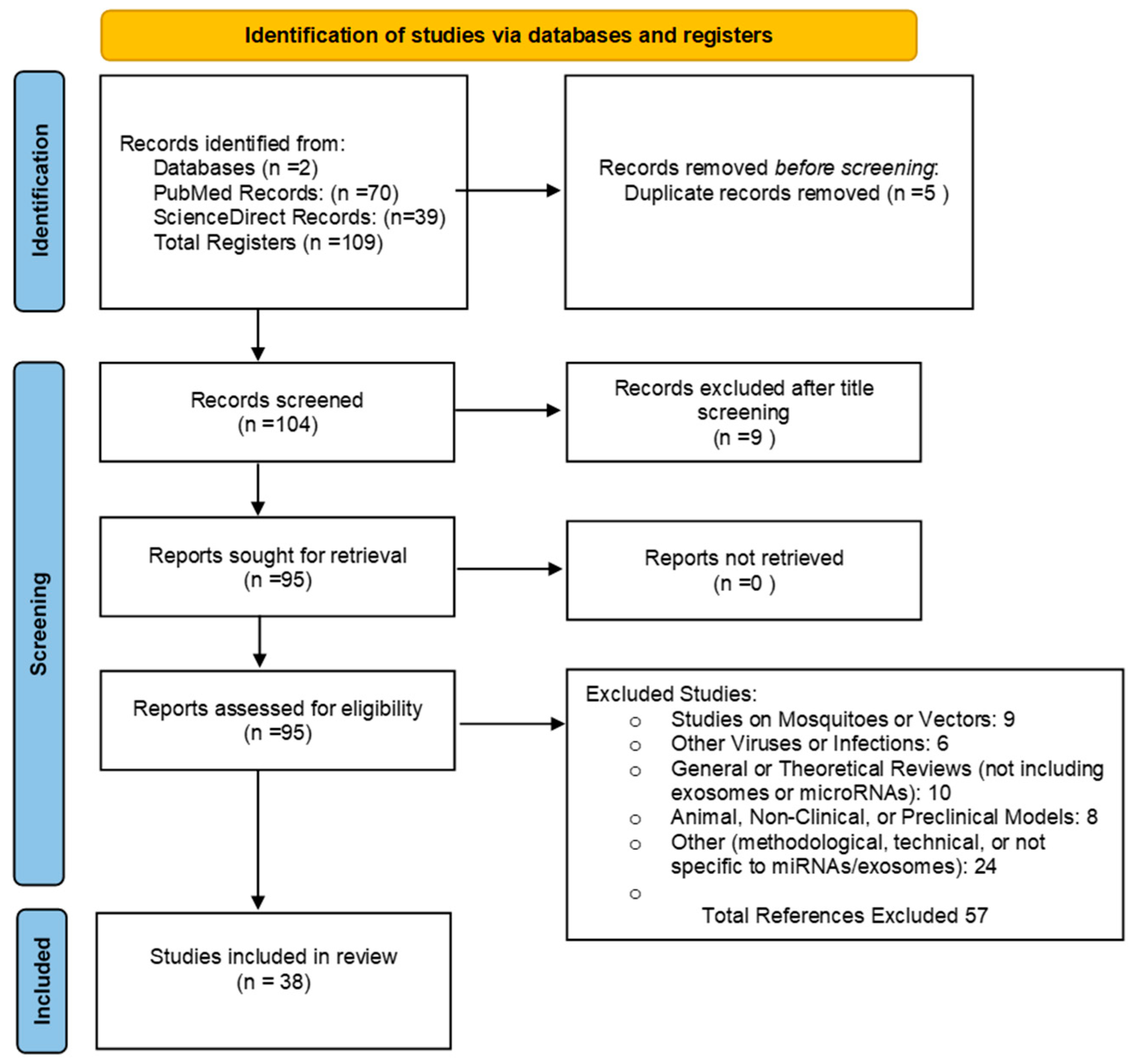

This study employs a narrative review to analyze recent research on the role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in the pathogenesis of severe dengue. The review aims to address the following research question: What is the role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in dengue pathogenesis, and how can they contribute to understanding vascular permeability, plasma leakage, immune evasion, and the development of clinically relevant biomarkers and therapeutic strategies?. To robustly address this question using relevant and up-to-date evidence, we conducted a comprehensive literature search in two databases, ScienceDirect and PubMed, following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework [

96]. The search strategy was based on the following equation: ('Extracellular Vesicles' OR 'Exosomes' OR 'Microvesicles' OR 'microRNAs') AND ('Dengue' OR 'Severe Dengue'). To enhance the sensitivity and specificity of the search, we incorporated Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. The detailed methodology is illustrated in

Figure 1. Additionally, to update data related to the epidemiology and general characteristics of the viral infection, the following search terms were used: ('Dengue' OR 'Severe Dengue' OR 'Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever') AND ('Epidemiology').

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this review focused on peer-reviewed journal articles, review articles, research papers, and book chapters published in English, Portuguese, or Spanish, within the last 10 years (2014 to 2024), that involved human studies or preclinical research. Articles were excluded if they primarily addressed mosquitoes or vectors without discussing extracellular vesicles (EVs) or microRNAs (miRNAs) in the context of dengue, investigated viruses or infections unrelated to dengue, were general or theoretical reviews that did not specifically cover exosomes, EVs, or miRNAs in relation to dengue pathogenesis, involved animal models or non-clinical studies without direct relevance to human clinical data on dengue, or were methodological or technical papers not focused on miRNAs, exosomes, or EVs, lacking clinical applicability to dengue. To ensure the quality of the paper, duplicates were meticulously reviewed, and article abstracts were included to verify the relevance and academic integrity of the literature

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis of miRNAs in Dengue

Bioinformatics analyses were conducted to investigate the relationship between circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) within EVs and dengue virus (DENV) infection or disease severity. A reanalysis of differentially expressed miRNAs (DEmiRs) was performed using the RNA sequencing dataset GSE150623, obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). This dataset represents the circulating microtranscriptome of dengue patients. The analysis was carried out using the limma-voom [

11] pipeline in R Studio [

12], enabling the identification of miRNAs potentially associated with disease progression and severity. DEmiRs cutoffs were set as |LogFC| > 2 and adjusted p-value < 0.05. Enrichment analysis of target genes of DemiRs was performed through Diana miRPath v4 [

13].

3. Clinical Presentation and Structural Overview of the Dengue Virus

The dengue virus is an enveloped 50-nm virus belonging to the Flavivirus genus and the Flaviviridae family [

14]. Its structure is icosahedral, and its genome consists of a single-stranded positive-sense RNA. This genome encodes a single open reading frame (ORF), which is translated into a polyprotein [

14]. The polyprotein is subsequently processed into three structural proteins (capsid [C], envelope [E], and prM/M) and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5). These proteins play critical roles in viral assembly, replication, and immune evasion within the host [

14].

To date, four clinically relevant dengue virus serotypes have been identified: DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4 [

15]. These serotypes are antigenically related, sharing 60–75% amino acid similarity. This limited cross-protective immunity contrasts with other viral infections. Within each serotype, viruses can be further divided into genotypes, differing genetically by up to 6% [

15]. These genetic variations can significantly influence virulence, disease severity, and the epidemiological dynamics of outbreaks [

14,

15].

Dengue pathogenesis progresses through three distinct phases: febrile, critical, and recovery, which define the clinical course of the disease. According to the 2009 WHO classification, dengue is categorized into dengue without warning signs, dengue with warning signs, and severe dengue. The febrile phase begins after an incubation period of 2 to 7 days, characterized by sudden fever exceeding 38°C, accompanied by symptoms such as headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, nausea, and rash [

16]. During this stage, viremia is high and detectable via quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), peaking within the first 4–5 days [

16]. Common complications include dehydration and febrile seizures in children due to high fever. In most cases, the infection is mild and self-limiting [

16].

The critical phase, occurring in some patients, particularly during heterotypic reinfections, lasts 24–48 hours and coincides with declining viremia and fever. This stage carries a higher risk of complications due to an exaggerated inflammatory response causing endothelial damage and increased capillary permeability [

17]. This can lead to warning signs such as abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, bleeding, and hepatomegaly. Severe cases may progress to significant fluid leakage, shock, and organ dysfunction affecting the liver, kidneys, and central nervous system (CNS) [

17].

Finally, the recovery phase involves the reabsorption of fluids and clinical stabilization. However, some patients may experience post-infection symptoms, including fatigue, muscle pain, depression, and neurological complications, particularly in adults [

18].

4. Immune Response and the Potential Role of EVs in Dengue Severity

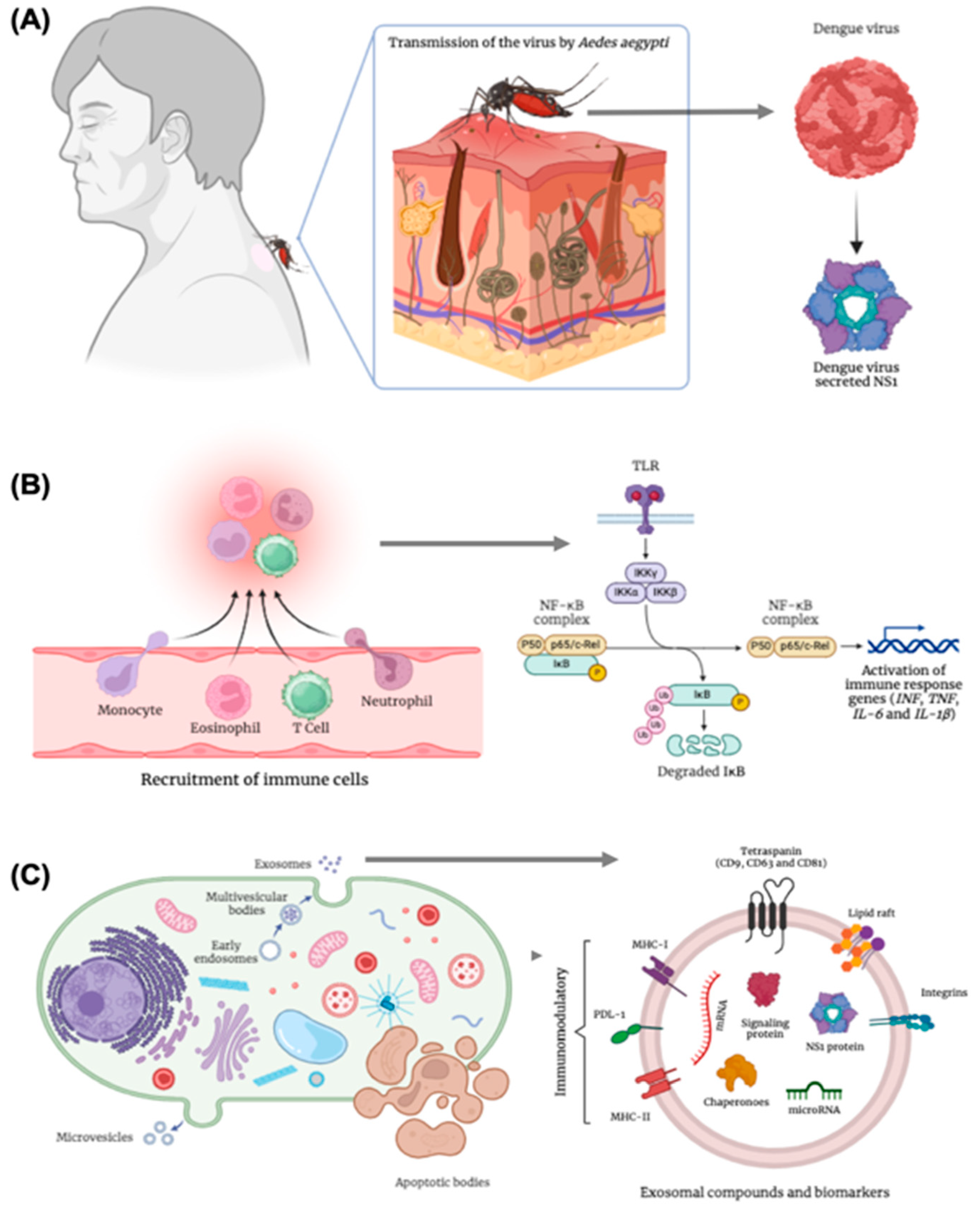

Dengue infection begins with the mosquito bite, introducing the virus into the dermis (

Figure 1A). There, Langerhans cells recognize the virus through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I, and MDA5 [

19]. This triggers the production of type I interferons (IFN)-α/β by macrophages, epithelial cells, and dendritic cells (DCs). The DCs migrate to lymph nodes, where they facilitate viral dissemination to monocytes and other DCs, amplifying viremia and targeting organs such as the liver, spleen, and vascular endothelium [

19].

The innate immune response, led by macrophages, DCs, and natural killer (NK) cells, produces pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, responsible for early symptoms like fever and malaise [

20]. Concurrently, DCs present viral antigens to T and B lymphocytes, activating the adaptive immune response. CD8+ T lymphocytes eliminate infected cells, while CD4+ T cells adopt a Th1 phenotype, promoting viral clearance via IFN-γ production (

Figure 1B). B lymphocytes generate antibodies targeting structural and nonstructural viral proteins, including M, E, and NS1. This adaptive response clears viremia and establishes specific immune memory, mediated by protective IgG antibodies against reinfection by the same serotype [

20].

Severe manifestations often arise during heterotypic secondary infections. In these cases, preexisting IgG antibodies fail to efficiently neutralize the new serotype, facilitating viral entry into monocytes and macrophages via Fc receptors. This process, known as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), increases viral replication and inflammation, contributing to disease severity [

21]. ADE excessively activates innate immune cells, triggering the release of cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-γ, along with vasoactive mediators like histamine and tryptase released by mast cells. These factors cause endothelial damage and heightened vascular permeability, resulting in plasma leakage characteristic of severe cases. CD8+ T lymphocytes activated during secondary infections further exacerbate inflammation, producing excessive pro-inflammatory cytokines due to their low affinity for the new serotype [

21]. However, not all severe dengue cases can be explained by ADE or original antigenic sin. Up to 5% of patients may develop severe forms during primary infection, suggesting that other factors—such as host genetics, age, and viral genotype—also contribute to disease severity [

21].

Extracellular vesicles have garnered significant attention in the study of dengue pathogenesis, particularly for their multifaceted roles in disease progression [

10]. As dynamic carriers of biomolecules, EVs derived from infected patients and in vitro models have been implicated in exacerbating dengue severity, including plasma leakage and endothelial dysfunction. Their ability to mediate immune interactions positions them as pivotal agents not only in dengue but also in other viral infections such as hepatitis, HIV, and flaviviruses [

22].

In severe dengue, EVs contribute to pathophysiological processes by facilitating viral dissemination, disrupting vascular integrity, and modulating host immune responses. Investigating EVs provides valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms driving these outcomes and offersers potential pathways for developing advanced diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions tailored to mitigate the impacts of severe dengue [

10,

22].

5. Biogenesis of EVs and Their Role as Competent Carriers for microRNAs

EVs are nanometric structures released by nearly all cell types, playing a central role in intercellular communication. Enclosed by lipid bilayers, these vesicles encapsulate bioactive molecules, including RNA, proteins, and lipids, which can modulate physiological and pathological processes in recipient cells. The synthesis of EVs involves distinct molecular pathways, depending on the specific subtype of the vesicle [

23]. The diversity of EV synthesis mechanisms highlights their functional heterogeneity and adaptability to cellular contexts [

24,

25]. The molecular machinery that regulates the biogenesis of these vesicles not only determines their formation but also influences cargo selection, membrane composition, and ultimately their biological effects on recipient cells [

26].

Apoptotic bodies, for instance, form during programmed cell death. As apoptosis progresses, caspase activation triggers the cleavage of cytoskeletal components, resulting in cellular fragmentation [

27]. Segments of the plasma membrane, forming apoptotic bodies (

Figure 1C), envelop these fragments. Unlike other EVs, apoptotic bodies can encapsulate organelles, chromatin fragments, and other cellular debris, serving as a mechanism for eliminating dead cells and modulating immune responses [

28,

29]. On the other hand, microvesicle formation occurs through budding outward from the plasma membrane, a process driven by cytoskeletal rearrangements. The biogenesis of these vesicles depends on changes in lipid asymmetry of the membrane, mediated by enzymes such as flippases, flopases, and scramblases [

30,

31]. The activation of these enzymes promotes the externalization of phosphatidylserine, contributing to membrane curvature and budding. Actomyosin contractions, regulated by Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) and calcium signals, provide the mechanical force required for membrane fission [

32,

33]. Microvesicles are often enriched with integrins, selectins, and metalloproteinases, which contribute to their functional specialization and targeting capacity (

Figure 1C).

Exosomes, distinct from apoptotic bodies and microvesicles, are formed inside multivesicular bodies (MVBs) through ESCRT-dependent or ESCRT-independent mechanisms [

32,

34]. Within MVBs, intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) bud inward into late endosomes. The ESCRT machinery, consisting of four main complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III), coordinates this process [

34]. ESCRT-0 recruits ubiquitinated cargos to the endosomal membrane, while ESCRT-I and -II promote membrane deformation, and ESCRT-III performs membrane scission. Accessory proteins, such as ALIX (ALG-2-interacting protein) and TSG101 (tumor susceptibility gene 101), interact with cargos and ESCRT components to fine-tune the vesicle formation process (

Figure 1C). Exosomal biogenesis can also occur through ESCRT-independent pathways, in which lipids like ceramides and tetraspanins (e.g., CD9, CD63, and CD81) play critical roles in membrane curvature and vesicle formation [

34]. After their formation, MVBs are transported along microtubules, guided by motor proteins like kinesins and dyneins, to the plasma membrane [

35]. Rab family proteins, especially Rab27a and Rab27b, regulate MVB anchoring and fusion with the plasma membrane, resulting in exosome release into the extracellular space [

36,

37].

In this context, EVs are crucial vehicles in intercellular communication, mediating the efficient transfer of microRNAs (miRNAs) and other biomolecules, particularly during viral infections [

38,

39]. miRNAs transported by EVs play key roles in modulating the host response and promoting viral pathogenesis, acting as post-transcriptional regulators of genes involved in viral replication, immune response, and inflammation [

40]. In the context of dengue virus (DENV) infection, studies show that EVs released by infected cells carry specific miRNAs, which can significantly alter the infection dynamics and virus-host interactions [

41].

During DENV infections, exosomes can carry miRNAs such as miR-21, miR-146a, and miR-155, which play crucial roles in modulating innate immunity [

42,

43]. For instance, miR-21, often enriched in EVs during viral infections, negatively regulates genes involved in apoptosis and viral replication control, promoting cell survival and allowing continuous viral replication [

44], miR-146a suppresses pro-inflammatory pathways, such as nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling, reducing excessive immune responses while also promoting viral persistence [

45]. miR-155, on the other hand, is associated with immune response amplification, being a miRNA with potentially ambiguous effects depending on the infection stage. Besides host-derived miRNAs, EVs can also transport viral RNA. Studies have shown that EVs released during DENV infections contain fragments of viral genomic RNA [

42,

45,

46]. These EVs can facilitate viral spread to adjacent cells, contributing to infection amplification as well as immune microenvironment modulation (

Figure 1C).

Recent studies have confirmed the presence of specific miRNAs in circulating EVs during DENV infection. A proteomic and transcriptomic analysis revealed that exosomes derived from dendritic cells infected with DENV carry miRNAs such as miR-21-5p, miR-222-3p, and miR-126-5p, which play important roles in regulating immune and inflammatory responses [

47,

48]. For example, miR-126-5p is involved in maintaining vascular integrity, and its dysfunction mediated by DENV contributes to increased vascular permeability observed in severe dengue [

49,

50]. Additionally, miR-222-3p has been associated with the suppression of antiviral responses by negatively regulating genes like STAT3 and SOCS3, critical components of interferon signaling [

50].

Exosomes released by infected cells have also been described as modulators of macrophage activation, promoting a pro-inflammatory phenotype that exacerbates the immune response and contributes to dengue pathogenesis. The transport of specific miRNAs to immune cells via EVs illustrates the ability of these vesicles to remodel the immune microenvironment, promoting both viral dissemination and exacerbated inflammation.

6. Overview of EVs' Role in Dengue Infection: Transmission Dynamics

During DENV infection, infected cells release EVs enriched with viral genetic material, including complete genomic RNA and structural and non-structural proteins like NS1 and E [

41]. These vesicles can act as vectors to infect neighboring cells, as the viral content within the EVs is protected from extracellular enzymatic degradation. Recent studies show that EVs can promote the entry of viral RNA into uninfected cells, where the viral replication cycle is initiated, contributing to the amplification of viral load in the host [

47,

51]. This process demonstrates that EVs are not merely a byproduct of the infection but active participants in viral dissemination.

Additionally, EVs can influence viral tropism. For example, exosomes released by infected hepatocytes may contain specific membrane proteins that facilitate fusion with target cells, such as monocytes and endothelial cells [

38,

52]. This specificity in targeting can enhance infection efficiency in critical tissues, such as the liver and blood vessels, exacerbating disease progression and contributing to the systemic spread of the virus [

53,

54].

Besides transporting viral components, EVs derived from infected cells play a central role in modulating immune responses. They can carry immunomodulatory molecules that suppress or redirect host responses to favor viral replication. For example, viral proteins carried in EVs, like NS1, can inhibit the IFN pathway in target cells, weakening the innate antiviral response [

55,

56]. This mechanism allows DENV to evade early detection by the immune system, facilitating its replication and spread. Furthermore, EVs containing specific microRNAs can directly influence cellular processes in the host [

57]. The transport of miRNAs such as miR-146a and miR-21, widely described in viral infections, has been associated with the suppression of inflammatory pathways and regulation of the immune environment [

58]. These miRNAs modulate the expression of genes crucial to the immune response, creating a cellular microenvironment conducive to viral replication and spread to other cells [

38,

59].

EVs are also implicated in regulating viral load and clinical progression of DENV infection. Studies show that elevated levels of circulating EVs correlate with higher viral loads and greater disease severity [

38]. This association can be attributed to the role of EVs in local infection amplification, transferring viral material directly to neighboring cells and modulating immune responses in ways that avoid efficient viral clearance [

38,

47].

Moreover, EVs derived from infected cells can alter the function of immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells, promoting the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α [

60]. This increase in cytokine production can trigger systemic inflammatory responses, contributing to plasma leakage syndrome and other severe symptoms of dengue, such as hemorrhagic fever and shock.

7. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Modulating Immune Responses in Dengue Infection

Recent evidence suggests that EVs present in dengue patients, as well as those derived from innate immune cells infected with the virus, have the ability to modulate the immune response, induce inflammation, and, in some cases, transport the viral genome. These EVs may influence dengue pathogenesis by facilitating viral spread and altering immune system function.

According to Kumari et al., EVs derived from patients with severe dengue express PD-L1 on their surface. This protein interacts with CD4+ lymphocytes, inhibiting their proliferation and increasing the expression of the PD-1 coreceptor [

61]. Furthermore, these EVs carry pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-6, IL-17A, IL-13, IL-5, and IL-4, which appear to contribute both to inflammation and the anergy observed in the study [

61]. Similarly, another study demonstrated that DCs infected with the dengue virus can secrete EVs containing mRNA of inflammatory mediators such as CXCR4, MIF, IL-17A, IL-8, and IL-6, which could be translated and exacerbate inflammation [

47].

Additionally, Mishra et al. showed that EVs derived from dengue-infected monocytes can transfer miR-148a, modulating USP33 and ATF3 levels in human microglial cells. This process may contribute to the expression of TNF-α, NF-κB, and IFN-β, factors associated with neuroinflammation—a complication observed in severe dengue cases that remains poorly understood from a pathophysiological perspective [

62]. These findings suggest that EVs play a significant role in dengue immunopathogenesis, acting as vehicles that transport molecules capable of modulating the immune response and potentially exacerbating disease-associated complications.

Although further evidence is needed, a potential immune evasion mechanism employed by the dengue virus involves the use of EVs to transport viral RNA or proteins that promote viral replication in target cells [

22,

47]. In a study led by Martins and collaborators, EVs derived from dengue-infected dendritic cells were shown to infect C6/36 cells in vitro, suggesting that these EVs may carry the complete viral genome [

47]. This mechanism could allow the virus to evade detection by antibodies and immune cells such as CD8+ lymphocytes and NK cells, which would typically recognize and eliminate the virus [

21].

Moreover, another study demonstrated that EVs derived from Aedes aegypti cells infected with dengue contain proteins such as AAEL017301 (elongation factor-1 alpha) and AAEL002675 (a protein of unknown function) that appear to increase susceptibility to infection in target cells [

63]. These findings highlight the critical role of EVs in dengue pathogenesis, emphasizing their potential as modulators of immune responses, facilitators of viral dissemination, and contributors to disease severity. Understanding the mechanisms underlying these processes could pave the way for novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

8. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Endothelial Damage and Vascular Hyperpermeability in Dengue

The integrity of the endothelial barrier plays a critical role in vascular homeostasis and is severely compromised during dengue infections, particularly in severe cases such as dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome [

64,

65,

66]. In this context, EVs are emerging as important mediators in processes that lead to endothelial dysfunction, directly contributing to vascular hyperpermeability and plasma leakage [

67,

68]. Detailed studies of these mechanisms have shed light on how EVs act as vehicles for bioactive molecules, including viral proteins, cytokines, and microRNAs, which alter the behavior of endothelial cells and exacerbate the clinical symptoms of the disease [

69,

70].

During dengue virus (DENV) infection, infected cells release EVs enriched with viral proteins, such as NS1 and E, that can directly interact with endothelial cells [

41]. NS1, in particular, is widely recognized for inducing the degradation of cell junction proteins, such as VE-cadherin and claudins, which are essential for maintaining vascular barrier integrity [

41,

69]. When carried by EVs, NS1 can reach distant endothelial cells, promoting systemic damage to the vascular network. This effect is not limited to localized areas of infection but extends to peripheral tissues, exacerbating plasma leakage and contributing to severe manifestations of dengue, such as edema and shock [

41,

70].

Additionally, exposure of endothelial cells to EVs derived from DENV-infected cells triggers metabolic and cytoskeletal changes in these cells [

38]. These changes, mediated by proteins and miRNAs transported by EVs, alter actin dynamics and impair the formation of stable cell contacts, further amplifying vascular permeability [

71]. EVs also carry molecules that activate inflammatory signaling pathways in endothelial cells, such as the TLR and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) pathways. For example, EVs containing viral RNA can interact with TLRs on the surface of endothelial cells, triggering a signaling cascade that results in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α [

71]. These cytokines, in turn, increase the expression of adhesion molecules, such as ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, facilitating leukocyte recruitment and perpetuating inflammation [

72]. This continuous inflammatory cycle further aggravates endothelial dysfunction and promotes fluid leakage.

Additionally, EVs can influence the activity of pathways associated with oxidative stress, such as the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in endothelial cells [

71]. This oxidative stress damages cellular components and amplifies endothelial barrier disruption, contributing to the widespread damage observed in severe DENV infections.

9. Role of Extracellular Vesicle-Derived microRNAs in Dengue Severity

EVs are crucial mediators of intercellular communication and play an important role in modulating host-pathogen interactions. In the context of dengue infection, specific miRNAs derived from EVs have been implicated in influencing disease outcomes and response [

62,

73].

miRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules, typically 20–22 nucleotides in length, that play a crucial role in regulating gene expression at the posttranscriptional level. Each miRNA can bind to multiple mRNA sequences with varying degrees of complementarity, enabling the simultaneous regulation of hundreds of genes in response to environmental changes.

Plasma EVs are derived from adaptive and innate immune cells as well as non-immune blood cells such as platelets [

74]. DENV infection leads to increased release of EVs from severe dengue patients platelets and monocytes [

61,

62], while also being able to change the load of such vesicles [

61].

In search for specific biomarkers candidates of severity of the pathological outcome, many studies aimed at miRNAs as potential biomarkers. Studies often reach different miRNAs candidates as they are usually performed on specific populations, geographically or age-restricted. Still, correlations of Differentially Expressed miRNAs (DEmiRs) found in DENV-infection and disease severity are reported in the literature for circulating miRNAs [

75,

76], thus indicating the possibility of miRNAs to function as disease biomarkers.

In this context, miRNAs derived from EVs are crucial in modulating immune responses, inflammation, and vascular dysfunction, particularly in the context of severe dengue. By targeting specific mRNAs, miRNAs regulate key pathways involved in these processes, influencing disease progression and severity.

A study showed that DENV infected cells increase the EVs release and the released levels of miR-148a, which suppresses USP33 and stabilizes the ATF3 protein levels, reporting a crucial role of the miR-148a/USP33/ATF3 axis on pro-inflammatory response and DENV replication maintained by EVs [

62]. miR-1204 and miR-491-5p are also reported to influence DENV replication response through p53 regulation of apoptosis [

77].

In the context of vascular dysfunction, miRNAs regulate endothelial cell integrity and permeability, two critical factors in dengue pathogenesis. For example, the regulation of EZH2 expression through miR-150 is suggested to interfere in plasma leakage during DENV infection [

78]. miRNAs are known to target junctional proteins and signaling molecules that maintain endothelial barrier function [

79,

80]. Their dysregulation can lead to increased vascular permeability, plasma leakage, and hemorrhagic manifestations characteristic of severe dengue, as is the case for the DENV-associated endothelial dysfunction related to miR-126-5p [

49,

50], although the link between miRNAs and thrombocytopenia in DENV is still unknown [

75]. Overall, miRNAs derived from EVs represent key molecular players that bridge immune dysregulation, inflammation, and vascular compromise in severe dengue.

10. Clinical Applications of EVs in Dengue Diagnosis

Recent research has highlighted the potential of EVs as key biomarkers for the identification and monitoring of severe dengue. Various studies have demonstrated that circulating EVs play a crucial role in the pathological processes associated with this disease [

10]. Both their concentration and the presence of specific surface antigens or miRNAs have been identified as valuable tools for diagnosing severe forms of dengue [

10].

For instance, Punyadee et al. (2015) reported significantly elevated levels of EVs in patients with DHF compared to those with non-severe dengue or healthy individuals. Moreover, they found that the quantity of these vesicles directly correlated with disease severity [

81]. Similarly, Kumari et al. (2023) identified an increase in platelet-derived EVs in patients with severe dengue, underscoring the immunoregulatory role of these vesicles [

61].

These findings are consistent with studies in other viral pathologies and even in cancer patients, where an increase in circulating EV concentration has also been observed [

82]. In dengue, circulating EVs may also transport viral components, such as the E, C, and NS1 proteins, potentially contributing to viral dissemination [

22].

Additionally, EVs derived from patients with severe dengue have shown the ability to carry the immune checkpoint PD-L1, highlighting their immunoregulatory role and potential to induce immune anergy [

61]. This phenomenon parallels observations in patients with severe COVID-19, where PD-L1 has been detected in both EVs and circulating monocytes [

83], suggesting shared features in immune modulation between the two pathologies.

Recent studies have also identified the presence of specific microRNAs in EVs found in the serum of patients with severe dengue [

10]. These microRNAs, which will be discussed in detail later, show promising potential as tools to differentiate between severe dengue, dengue with warning signs, and dengue without warning signs.

11. Isolation and Detection of EVs from Dengue Patients

EVs from dengue patients must first be isolated for subsequent quantification, phenotypic characterization, and molecular content analysis. These EVs can be obtained from serum or plasma samples preserved with anticoagulants such as EDTA or citrate, either processed immediately or stored under ultracold conditions for later analysis [

84].

The most commonly used methods for EV isolation include ultracentrifugation, immunoaffinity capture, precipitation, and size-exclusion chromatography [

85]. The choice of method should be based on the specific goals of the study, considering factors such as EV concentration, purity, and the intended final application, such as functional assays [

85]. Once isolated, EVs can be characterized using a variety of techniques. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) determines particle size and concentration, while electron microscopy confirms their presence and morphology. Techniques such as Western blotting and immunofluorescence are employed to detect surface antigens and analyze the protein content of EVs [

85].

Additionally, next-generation flow cytometers, such as the CytoFLEX Nano, have optimized detectors to identify submicron particles as small as 40 nm. These advanced technologies enable precise measurement of EV size and concentration, as well as surface antigen and intracellular protein characterization, allowing for comprehensive immunophenotyping [

86]. Simultaneously, traditional techniques such as qPCR and advanced tools like next-generation sequencing are used to analyze microRNAs, non-coding RNAs, and DNA within EVs [

85].

To ensure reproducible and high-quality results, rigorous quality control, proper pre-analytical sample handling, and continuous method validation are essential. Moreover, standardization of procedures following international guidelines, such as the Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV), is recommended [

85]. This will facilitate the efficient implementation of dengue-associated EV detection in diagnostic centers and future clinical research.

12. EVs as Potential Biomarkers for Dengue Severity

EVs play a crucial role in the pathophysiology of dengue, particularly in endothelial dysfunction and vascular hyperpermeability, processes that are vital for disease progression [

87,

88]. These vesicles not only amplify the damage directly by promoting viral spread but also serve as molecular markers of the infection's severity. In severe cases of dengue, such as hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome, the profile of circulating EVs changes, reflecting an increase in viral load, the presence of viral proteins like NS1, and modulation of the host's immune response [

41,

70]. Analyzing the specific molecular content of these EVs could provide new biomarkers for predicting the transition from mild to severe dengue and monitoring therapeutic effectiveness.

Identifying biomarkers based on circulating EVs offers a powerful tool for early detection of dengue progression and for tailoring treatment. The role of EVs in viral material transport, their influence on inflammatory pathways, and their contribution to viral load highlight their importance in the pathogenesis of dengue. Therapeutic strategies that block the formation or release of EVs, or interfere with their interaction with endothelial cells, could prove promising for mitigating the severe effects of DENV infection and improving clinical outcomes.

13. Differentially Expressed miRNAs in Dengue Patients and Potential Signaling Pathways Involved

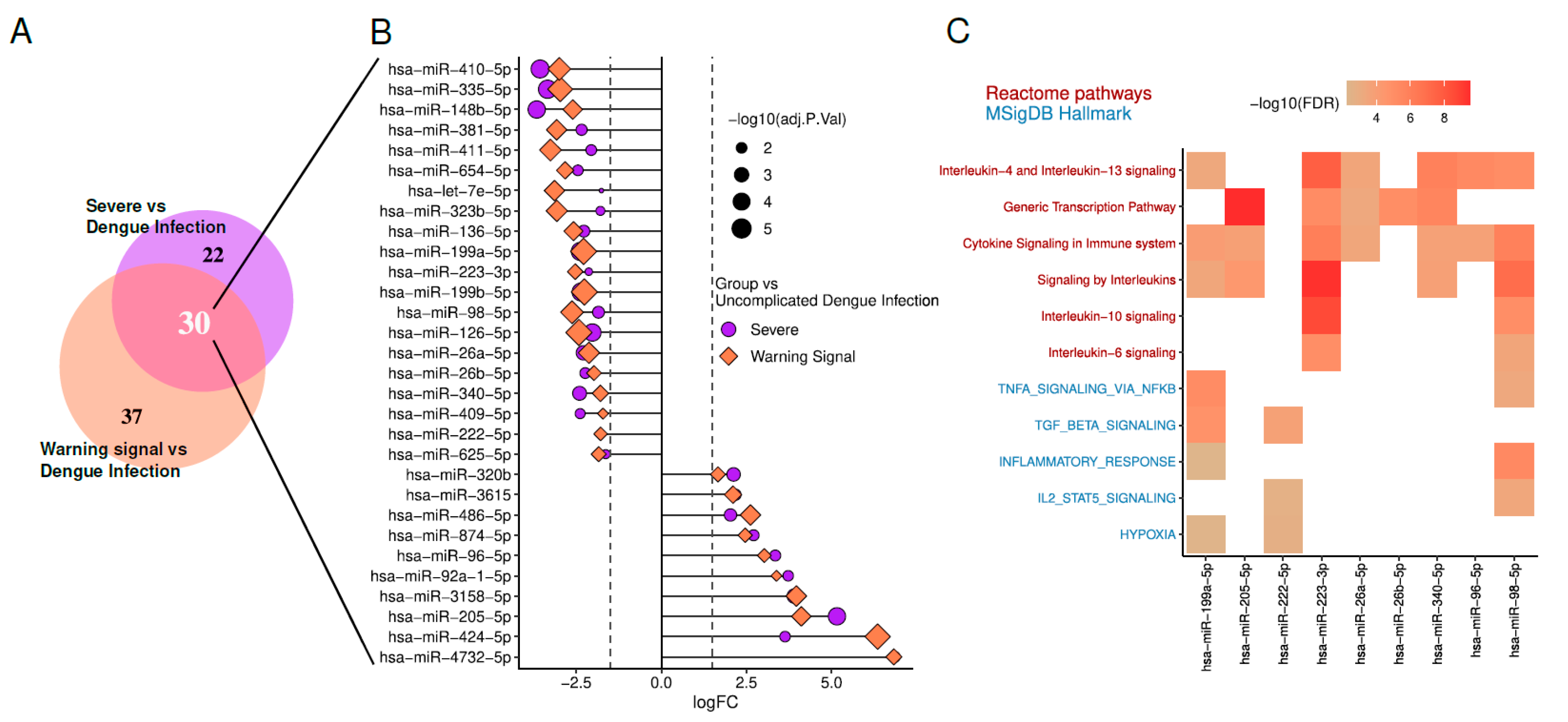

To investigate the relationship between miRNAs and DENV infection or severity, we reanalyzed DEmiRs from an RNA sequencing dataset of the circulating microtranscriptome of dengue patients (GSE150623) [

89], using the limma-voom pipeline in R.

We focused on DEmiRs with |LogFC| ≥ 2 and adjusted p-value < 0.05. In both Severe vs Dengue Infection (DI) and Warning Sign vs DI comparisons. Among them, 20 miRNAs are downregulated, indicating a decrease in their expression levels. In contrast, 10 miRNAs are upregulated, showing increased expression levels. Enrichment analysis of predicted targets for these DEmiRs was performed through Diana Tools miRPath v4 [

13]. Enrichment terms associated with DENV manifestations are illustrated in the

Figure 2.

Regarding hypoxia, it has been demonstrated that the secretion and composition of exosomes are closely influenced by oxygen pressure in the microenvironment. As reviewed by Yaghoubi et al (2020), several studies suggest that cells respond to hypoxia by altering the molecular profile of exosomes [

90]. In vitro analyses further revealed that monocytes under hypoxic conditions required higher concentrations of antibodies for DENV neutralization [

91]. For Stat5, members of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway play a critical role in the interferon-induced inflammatory response, driving the expression of antiviral and pro-inflammatory proteins during DENV infection [

92]. Interestingly, the inhibition of Janus Kinase (JAK), which prevents interferon signaling, has shown therapeutic effects in experimental model of arenavirus hemorrhagic fever, suggesting potential applicability to DENV infections [

93].

Concerning TNFα, blocking TNFα alone reduced plasma leakage, while co-treatment with sunitinib significantly improved the survival of DENV-infected mice without affecting viremia [

94]. DENV entry via ADE has been shown to suppress the host cell's antiviral response by inhibiting IFN-α production while inducing IL-10 expression, thereby facilitating increased viral replication. This aligns with clinical observations of higher viremia, elevated IL-10 levels, and reduced IFN levels in patients with severe dengue [

95]. Additionally, interleukins 4, 6, 10, and 13 were found to be significantly elevated in EVs derived from patients with severe dengue [

61].

These findings underscore the importance of miRNAs in modulating critical biological processes during DENV infection, including immune responses, cytokine regulation, and cellular signaling pathways. The observed changes in miRNA expression, coupled with their enrichment in pathways linked to hypoxia, JAK-STAT signaling, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, suggest that miRNAs may serve as potential biomarkers for disease severity and therapeutic targets.

14. Concluding Remarks

An expanding body of evidence underscores the critical role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in the pathogenesis of dengue virus (DENV) infection. EVs act as active mediators of viral dissemination, immune modulation, and vascular dysfunction, contributing significantly to disease progression.

In dengue patients, circulating EVs have been implicated in modulating immune responses through the transport of immunomodulatory molecules. These include checkpoint inhibitors such as PD-L1 and anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and IL-10, which suppress host immune responses and facilitate viral persistence. Moreover, EVs carry microRNAs (miRNAs) with immune-suppressive functions, such as miR-146a and miR-21. These miRNAs reprogram host cellular environments, creating conditions conducive to viral replication and evasion while intensifying inflammatory responses.

In severe dengue cases, EVs exacerbate endothelial dysfunction and vascular hyperpermeability. Viral proteins, such as NS1, and specific miRNAs transported within EVs target endothelial junctional integrity, promoting disruption and inflammation. These effects are mediated through activation of Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling and reactive oxygen species (ROS) pathways. These mechanisms underlie hallmark complications of severe dengue, including plasma leakage, hemorrhagic manifestations, and shock.

EVs also demonstrate significant potential as biomarkers for early diagnosis and monitoring of severe dengue. Elevated circulating EV levels have been correlated with increased viral loads and disease severity. Furthermore, the presence of PD-L1 and specific miRNAs within EVs, such as miR-21 and miR-126-5p, has been associated with severe clinical outcomes, making them promising tools for stratifying patient risk.

Future research should prioritize elucidating the molecular mechanisms underpinning EV-mediated pathogenesis in dengue. Additionally, standardizing methodologies for EV isolation and characterization will be essential for translating these findings into clinical practice. Integrating EV-based biomarkers and therapeutics into dengue management strategies offers a promising avenue to mitigate the global health burden of this disease.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conceptualization, methodology, search, analysis, and writing of the article. Supervision, review, and editing were carried out by JSHA and CJCF. Funding acquisition: JSHA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Colombia under Call 890 of 2020 (Code: 82613) and additionally funded by the Central Unit of Valle del Cauca (Colombia) through Internal Call No. 17.

Data Availability Statement

Bioinformatics analyses performed in this article are available upon request. Inquiries should be directed to jshenao@uceva.edu.co.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Murugesan A, Manoharan M. Dengue Virus. Emerging and Reemerging Viral Pathogens, Elsevier; 2020, p. 281–359. [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Nealon, J. Dengue in a changing climate. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, S.; Gething, P.W.; Brady, O.J.; Messina, J.P.; Farlow, A.W.; Moyes, C.L.; Drake, J.M.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hoen, A.G.; Sankoh, O.; et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 2013, 496, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asish, P.R.; Dasgupta, S.; Rachel, G.; Bagepally, B.S.; Kumar, C.P.G. Global prevalence of asymptomatic dengue infections - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 134, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dengue Multi-Country Grade 3 Outbreak 2024 - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization 2024. https://www.paho.org/en/topics/dengue/dengue-multi-country-grade-3-outbreak (accessed December 31, 2024).

- Kularatne, S.A.; Dalugama, C. Dengue infection: Global importance, immunopathology and management. Clin. Med. 2022, 22, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Tiwari, A.; Satone, P.D.; Priya, T.; Meshram, R.J.; Iv, R.K.S. Updates in the Management of Dengue Shock Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e46713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Sabeena, S.P.; Varma, M.; Arunkumar, G. Current Understanding of the Pathogenesis of Dengue Virus Infection. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 78, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavige, G.N.; Ogg, G.S. Pathogenesis of vascular leak in dengue virus infection. Immunology 2017, 151, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Lata, S.; Ali, A.; Banerjea, A.C. Dengue haemorrhagic fever: a job done via exosomes? Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1626–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023.

- Tastsoglou, S.; Skoufos, G.; Miliotis, M.; Karagkouni, D.; Koutsoukos, I.; Karavangeli, A.; Kardaras, F.S.; Hatzigeorgiou, A.G. DIANA-miRPath v4.0: expanding target-based miRNA functional analysis in cell-type and tissue contexts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W154–W159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, V.D.; Tripathi, I.P.; Tripathi, R.C.; Bharadwaj, S.; Mishra, S.K. Genomics, proteomics and evolution of dengue virus. Briefings Funct. Genom. 2017, 16, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M.G.; Gubler, D.J.; Izquierdo, A.; Martinez, E.; Halstead, S.B. Dengue infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016, 2, 16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrán-Silva SL, Chacón-Hernández SS, Moreno-Palacios E, Pereyra-Molina JÁ. Clinical and differential diagnosis: Dengue, chikungunya and Zika. Revista Médica Del Hospital General de México 2018;81:146–53. [CrossRef]

- Tejo, A.M.; Hamasaki, D.T.; Menezes, L.M.; Ho, Y.-L. Severe dengue in the intensive care unit. J. Intensiv. Med. 2023, 4, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, D.T.H.; Clapham, H.; Giger, E.; Kieu, N.T.T.; Nam, N.T.; Hong, D.T.T.; Nuoi, B.T.; Cam, N.T.H.; Quyen, N.T.H.; Turner, H.C.; et al. Burden of Postinfectious Symptoms after Acute Dengue, Vietnam. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, B.H.; Lim, H.T.; Lim, C.P.; Lai, N.S.; Leow, C.H. Dengue virus infection – a review of pathogenesis, vaccines, diagnosis and therapy. Virus Res. 2022, 324, 199018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. John, A.L.; Rathore, A.P.S. Adaptive immune responses to primary and secondary dengue virus infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.F.; Voon, G.Z.; Lim, H.X.; Chua, M.L.; Poh, C.L. Innate and adaptive immune evasion by dengue virus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1004608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latanova, A.; Karpov, V.; Starodubova, E. Extracellular Vesicles in Flaviviridae Pathogenesis: Their Roles in Viral Transmission, Immune Evasion, and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-J.; Wang, C. A review of the regulatory mechanisms of extracellular vesicles-mediated intercellular communication. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, N.; Drago, G.; Ruggieri, S.; Cibella, F.; Colombo, P.; Longo, V. Extracellular Vesicles and Immunity: At the Crossroads of Cell Communication. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, G.B.; Bunn, K.E.; Pua, H.H.; Rafat, M. Extracellular vesicles: mediators of intercellular communication in tissue injury and disease. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetta, C.; Ghigo, E.; Silengo, L.; Deregibus, M.C.; Camussi, G. Extracellular vesicles as an emerging mechanism of cell-to-cell communication. Endocrine 2012, 44, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yang, T.; Ma, M.; Fan, L.; Ren, L.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, B.; Xia, J.; Hao, Z. Extracellular vesicles meet mitochondria: Potential roles in regenerative medicine. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 206, 107307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zeng, L.; Xu, Z.; Weng, J.; Xia, J.; Li, J.; Pathak, J.L. Apoptotic bodies: bioactive treasure left behind by the dying cells with robust diagnostic and therapeutic application potentials. J. Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, S.; Sakuragi, T.; Segawa, K. Flippase and scramblase for phosphatidylserine exposure. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2020, 62, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, J.W.; Schmidtmann, M.; D’souza-Schorey, C. The ins and outs of microvesicles. FASEB BioAdvances 2021, 3, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, C.; Patil, R.; Combrink, K.; Sharif, N.; Srinivas, S. Rho-Rho kinase pathway in the actomyosin contraction and cell-matrix adhesion in immortalized human trabecular meshwork cells. 2011, 17, 1877–1890.

- Sakurada, S.; Takuwa, N.; Sugimoto, N.; Wang, Y.; Seto, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Takuwa, Y.; S, L.; X, J.; H, L.; et al. Ca 2+ -Dependent Activation of Rho and Rho Kinase in Membrane Depolarization–Induced and Receptor Stimulation–Induced Vascular Smooth Muscle Contraction. Circ. Res. 2003, 93, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Shin, K.J.; Jang, H.-J.; Ryu, J.-S.; Lee, C.Y.; Yoon, J.H.; Seo, J.K.; Park, S.; Lee, S.; Je, A.R.; et al. GPR143 controls ESCRT-dependent exosome biogenesis and promotes cancer metastasis. Dev. Cell 2023, 58, 320–334.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janas, A.M.; Sapoń, K.; Janas, T.; Stowell, M.H.; Janas, T. Exosomes and other extracellular vesicles in neural cells and neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, M.; Carmo, N.B.; Krumeich, S.; Fanget, I.; Raposo, G.; Savina, A.; Moita, C.F.; Schauer, K.; Hume, A.N.; Freitas, R.P.; et al. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarroya-Beltri, C.; Baixauli, F.; Gutiérrez-Vázquez, C.; Sánchez-Madrid, F.; Mittelbrunn, M. Sorting it out: Regulation of exosome loading. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2014, 28, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.A.; Baba, S.K.; Sadida, H.Q.; Marzooqi, S.A.; Jerobin, J.; Altemani, F.H.; Algehainy, N.; Alanazi, M.A.; Abou-Samra, A.-B.; Kumar, R.; et al. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, F.S.Y.; Teixeira, F.M.E.; Sato, M.N.; da Silva Oliveira, L.M. Delivery of microRNAs by Extracellular Vesicles in Viral Infections: Could the News be Packaged? Cells 2019, 8, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chen, C.C.; Kim, S.; Singh, A.; Singh, G. Role of Extracellular vesicle microRNAs and RNA binding proteins on glioblastoma dynamics and therapeutics development. Extracell. Vesicle 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Safadi, D.; Lebeau, G.; Lagrave, A.; Mélade, J.; Grondin, L.; Rosanaly, S.; Begue, F.; Hoareau, M.; Veeren, B.; Roche, M.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles Are Conveyors of the NS1 Toxin during Dengue Virus and Zika Virus Infection. Viruses 2023, 15, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Lin, T.; Liu, C.; Cheng, C.; Han, X.; Jiang, X. microRNAs, the Link Between Dengue Virus and the Host Genome. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.R.; Abd-Aziz, N.; Affendi, S.; Poh, C.L. Role of microRNAs in antiviral responses to dengue infection. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanokudom, S.; Vilaivan, T.; Wikan, N.; Thepparit, C.; Smith, D.R.; Assavalapsakul, W. miR-21 promotes dengue virus serotype 2 replication in HepG2 cells. Antivir. Res. 2017, 142, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Tang, T.; Zhou, Q.; Feng, C.; Jin, Y.; Wu, Z. Exosome-mediated miR-146a transfer suppresses type I interferon response and facilitates EV71 infection. PLOS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q. Roles and mechanisms of exosomal microRNAs in viral infections. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, S.d.T.; Kuczera, D.; Lötvall, J.; Bordignon, J.; Alves, L.R. Characterization of Dendritic Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles During Dengue Virus Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorop, A.; Iacob, R.; Iacob, S.; Constantinescu, D.; Chitoiu, L.; Fertig, T.E.; Dinischiotu, A.; Chivu-Economescu, M.; Bacalbasa, N.; Savu, L.; et al. Plasma Small Extracellular Vesicles Derived miR-21-5p and miR-92a-3p as Potential Biomarkers for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriprapun, M.; Rattanamahaphoom, J.; Sriburin, P.; Chatchen, S.; Limkittikul, K.; Sirivichayakul, C. The expression of circulating hsa-miR-126-3p in dengue-infected Thai pediatric patients. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2022, 117, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloia, A.L.; Abraham, A.M.; Bonder, C.S.; Pitson, S.M.; Carr, J.M. Dengue Virus-Induced Inflammation of the Endothelium and the Potential Roles of Sphingosine Kinase-1 and MicroRNAs. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloherty, A.P.M.; Rader, A.G.; Patel, K.S.; Eisden, T.-J.T.H.D.; van Piggelen, S.; Schreurs, R.R.C.E.; Ribeiro, C.M.S. ; Ren Dengue virus exploits autophagy vesicles and secretory pathways to promote transmission by human dendritic cells. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1260439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Niu, J.; Shi, Y. Exosomes target HBV-host interactions to remodel the hepatic immune microenvironment. J. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLachlan NJ, Dubovi EJ, editors. Chapter 3 - Pathogenesis of Viral Infections and Diseases. Fenner’s Veterinary Virology (Fourth Edition), San Diego: Academic Press; 2011, p. 43–74. [CrossRef]

- Klasse, PJ. The Molecular Basis of Viral Infection. Academic Press; 2015.

- Tisoncik, J.R.; Billharz, R.; Burmakina, S.; Belisle, S.E.; Proll, S.C.; Korth, M.J.; García-Sastre, A.; Katze, M.G. The NS1 protein of influenza A virus suppresses interferon-regulated activation of antigen-presentation and immune-proteasome pathways. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caobi, A.; Nair, M.; Raymond, A.D. Extracellular Vesicles in the Pathogenesis of Viral Infections in Humans. Viruses 2020, 12, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Messina, L.; Gutiérrez-Vázquez, C.; Rivas-García, E.; Sánchez-Madrid, F.; de la Fuente, H. Immunomodulatory role of microRNAs transferred by extracellular vesicles. Biol. Cell 2015, 107, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torri, A.; Carpi, D.; Bulgheroni, E.; Crosti, M.-C.; Moro, M.; Gruarin, P.; Rossi, R.L.; Rossetti, G.; Di Vizio, D.; Hoxha, M.; et al. Extracellular MicroRNA Signature of Human Helper T Cell Subsets in Health and Autoimmunity. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 2903–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nail, H.M.; Chiu, C.-C.; Leung, C.-H.; Ahmed, M.M.M.; Wang, H.-M.D. Exosomal miRNA-mediated intercellular communications and immunomodulatory effects in tumor microenvironments. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 30, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Sun, J.; Dastgheyb, R.M.; Li, Z. Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles modulate innate immune responses to affect tumor progression. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1045624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Bandyopadhyay, B.; Singh, A.; Aggarwal, S.; Yadav, A.K.; Vikram, N.K.; Guchhait, P.; Banerjee, A. Extracellular vesicles recovered from plasma of severe dengue patients induce CD4+ T cell suppression through PD-L1/PD-1 interaction. mBio 2023, 14, e0182323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Lahon, A.; Banerjea, A.C. Dengue Virus Degrades USP33–ATF3 Axis via Extracellular Vesicles to Activate Human Microglial Cells. J. Immunol. 2020, 205, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.S.; Feitosa-Suntheimer, F.; Araujo, R.V.; Hekman, R.M.; Asad, S.; Londono-Renteria, B.; Emili, A.; Colpitts, T.M. Dengue Virus Infection of Aedes aegypti Alters Extracellular Vesicle Protein Cargo to Enhance Virus Transmission. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Woda, M.; Ennis, F.A.; Libraty, D.H. Dengue Virus Infection Differentially Regulates Endothelial Barrier Function over Time through Type I Interferon Effects. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoub, S.; Wertheim, H.; Simmons, C.P.; Screaton, G.; Wills, B. Cardiovascular manifestations of the emerging dengue pandemic. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2014, 11, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Kelley, J.F. Endothelial cells in dengue hemorrhagic fever. Antivir. Res. 2014, 109, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, V.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y.; Wu, M.H.; Yuan, S.Y. Extracellular vesicles: new players in regulating vascular barrier function. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 319, H1181–H1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; He, B. Insight into endothelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular disease: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 207, 107309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, N.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Z.; Fan, X. Promising nanotherapeutics of stem cell extracellular vesicles in liver regeneration. Regen. Ther. 2024, 26, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javdani-Mallak, A.; Salahshoori, I. Environmental pollutants and exosomes: A new paradigm in environmental health and disease. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 925, 171774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tan, J.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, Q. MicroRNA in extracellular vesicles regulates inflammation through macrophages under hypoxia. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, S.S.; Mazzarino, M.C.; Di Pino, L.; Malaponte, G.; Porto, C.; Pennisi, G.; Marchese, G.; Costa, M.P.; Digrandi, D.; Celotta, G.; et al. High circulating levels of cytokines (IL-6 and TNFa), adhesion molecules (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) and selectins in patients with peripheral arterial disease at rest and after a treadmill test. Vasc. Med. 2003, 8, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Aneja, A.; Ghosh, S.; Devvanshi, H.; C. , D.; Sahu, R.; Ross, C.; Kshetrapal, P.; Maitra, A.; Das, S. Association of exosomal miR-96-5p and miR-146a-5p with the disease severity in dengue virus infection. J. Med Virol. 2023, 95, e28614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auber, M.; Svenningsen, P. An estimate of extracellular vesicle secretion rates of human blood cells. J. Extracell. Biol. 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limothai, U.; Jantarangsi, N.; Suphavejkornkij, N.; Tachaboon, S.; Dinhuzen, J.; Chaisuriyong, W.; Trongkamolchai, S.; Wanpaisitkul, M.; Chulapornsiri, C.; Tiawilai, A.; et al. Discovery and validation of circulating miRNAs for the clinical prognosis of severe dengue. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Jiang, X.; Gu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, S.; Jiang, C.; Xie, W. Dysregulated Serum MiRNA Profile and Promising Biomarkers in Dengue-infected Patients. Int. J. Med Sci. 2016, 13, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Tambyah, P.; Ching, C.S.; Sepramaniam, S.; Ali, J.M.; Armugam, A.; Jeyaseelan, K.; Chai, S. microRNA expression in blood of dengue patients. Ann. Clin. Biochem. Int. J. Biochem. Lab. Med. 2015, 53, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapugaswatta, H.; Amarasena, P.; Premaratna, R.; Seneviratne, K.N.; Jayathilaka, N. Differential expression of microRNA, miR-150 and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) in peripheral blood cells as early prognostic markers of severe forms of dengue. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Hernando, C.; Suárez, Y. MicroRNAs in endothelial cell homeostasis and vascular disease. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2018, 25, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pena-Philippides, J.C.; Gardiner, A.S.; Caballero-Garrido, E.; Pan, R.; Zhu, Y.; Roitbak, T. Inhibition of MicroRNA-155 Supports Endothelial Tight Junction Integrity Following Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punyadee, N.; Mairiang, D.; Thiemmeca, S.; Komoltri, C.; Pan-Ngum, W.; Chomanee, N.; Charngkaew, K.; Tangthawornchaikul, N.; Limpitikul, W.; Vasanawathana, S.; et al. Microparticles Provide a Novel Biomarker To Predict Severe Clinical Outcomes of Dengue Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 1587–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, L.; Kasimir-Bauer, S.; Bittner, A.-K.; Hoffmann, O.; Wagner, B.; Manvailer, L.F.S.; Kimmig, R.; Horn, P.A.; Rebmann, V. Elevated levels of extracellular vesicles are associated with therapy failure and disease progression in breast cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. OncoImmunology 2017, 7, e1376153–e1376153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao-Agudelo, J.S.; Ayala, S.; Badiel, M.; Zea-Vera, A.F.; Cortes, L.M. Classical monocytes-low expressing HLA-DR is associated with higher mortality rate in SARS-CoV-2+ young patients with severe pneumonia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucien, F.; Gustafson, D.; Lenassi, M.; Li, B.; Teske, J.J.; Boilard, E.; von Hohenberg, K.C.; Falcón-Perez, J.M.; Gualerzi, A.; Reale, A.; et al. MIBlood-EV: Minimal information to enhance the quality and reproducibility of blood extracellular vesicle research. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2023, 12, e12385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O'Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittain, G.C.; Chen, Y.Q.; Martinez, E.; Tang, V.A.; Renner, T.M.; Langlois, M.-A.; Gulnik, S. A Novel Semiconductor-Based Flow Cytometer with Enhanced Light-Scatter Sensitivity for the Analysis of Biological Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-R.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Lin, Y.-S.; Liu, H.-S.; Liu, C.-C.; Perng, G.-C.; Yeh, T.-M. Dengue Virus Nonstructural Protein 1 Induces Vascular Leakage through Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor and Autophagy. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, S.W.; Thomas, A.; White, L.; Stoops, M.; Corten, M.; Hannemann, H.; de Silva, A.M. Dengue virus-like particles mimic the antigenic properties of the infectious dengue virus envelope. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, J.; Bandyopadhyay, B.; Pandey, A.D.; Ramachandran, V.G.; Das, S.; Sood, V.; Banerjee, A.; Vrati, S. High-Throughput RNA Sequencing Analysis of Plasma Samples Reveals Circulating microRNA Signatures with Biomarker Potential in Dengue Disease Progression. mSystems 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghoubi, S.; Najminejad, H.; Dabaghian, M.; Karimi, M.H.; Abdollahpour-Alitappeh, M.; Rad, F.; Mahi-Birjand, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Mohseni, F.; Lari, M.S.; et al. How hypoxia regulate exosomes in ischemic diseases and cancer microenvironment? IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 1286–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, E.S.; Cheong, W.F.; Chan, K.R.; Ong, E.Z.; Chai, X.; Tan, H.C.; Ghosh, S.; Wenk, M.R.; Ooi, E.E. Hypoxia enhances antibody-dependent dengue virus infection. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 1348–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Bhattacharjee, S. Dengue virus: epidemiology, biology, and disease aetiology. Can. J. Microbiol. 2021, 67, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, M.; Remy, M.M.; Merkler, D.; Pinschewer, D.D. The Janus Kinase Inhibitor Ruxolitinib Prevents Terminal Shock in a Mouse Model of Arenavirus Hemorrhagic Fever. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branche, E.; Tang, W.W.; Viramontes, K.M.; Young, M.P.; Sheets, N.; Joo, Y.; Nguyen, A.-V.T.; Shresta, S. Synergism between the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib and Anti-TNF antibody protects against lethal dengue infection. Antivir. Res. 2018, 158, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Mathew, A.; Rothman, A.L. Immune-mediated cytokine storm and its role in severe dengue. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017, 39, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).