1. Introduction

Hyperspectral cameras are valuable tools for Earth observation, supporting a wide range of applications such as agricultural, forestry, and ocean remote sensing. These cameras capture both images and spectral data simultaneously, enabling the detection and classification of target conditions [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Although several operational systems and development plans exist for hyperspectral cameras on large satellites and the International Space Station [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], these remain limited in number, and their effectiveness has not been fully demonstrated. Ideal attributes for hyperspectral remote sensing include full Earth coverage and high observation frequency. This is particularly critical in agricultural monitoring, where frequent and regular observations are essential for effective crop management. However, when relying on a single satellite, the observation frequency remains low (approximately once every two weeks). A promising solution is the deployment of a constellation of CubeSats equipped with hyperspectral cameras.

Traditionally, spaceborne hyperspectral cameras have required large telescopes to gather sufficient light for spectroscopic observations. Recent advances in image sensor technology have significantly improved sensitivity, making hyperspectral imaging feasible even with smaller telescopes. Consequently, new initiatives are underway to deploy microsatellites and CubeSats with hyperspectral capabilities. In recent years, numerous start-up companies have entered the Earth observation sector, focusing on the mass production of small and microsatellites and offering services through satellite constellations. A satellite constellation refers to a system in which multiple microsatellites are interconnected and operated in a coordinated manner. Start-up companies are increasingly constructing such constellations to create a global Earth observation network [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Integrating hyperspectral cameras into CubeSats and microsatellites can significantly enhance the temporal resolution of Earth observation data collection.

Examples of compact hyperspectral cameras include HYPSO-1, developed by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology [

15], and HyperScout-1, developed by Cosine Remote Sensing B.V. [

16]. Dragonette, developed by Canada’s Wyvern, has a wavelength resolution of 20 nm, resulting in coarser spectral data than some alternatives. However, it achieves a ground sampling distance of 5.3 m, allowing for higher spatial resolution imaging [

17]. Kuva Space, a Finnish hyperspectral satellite start-up, aims to provide global images two to three times daily using a constellation of 100 6U CubeSats called Hyperfield, which will cover the spectral range from visible near-infrared to short-wavelength infrared [

18]. Planet’s Tanager satellite is equipped with a hyperspectral sensor that spans wavelengths from 400 nm to 2500 nm. While many small satellites are limited to visible and near-infrared observations, Tanager’s ability to extend into the short-wavelength infrared range (up to 2500 nm) is a key advantage [

19]. In this range, methane absorbs between 2150 and 2450 nm, and CO₂ absorbs between 1980 and 2100 nm. This capability enables the distinct detection of CO₂ and methane, contributing to efforts toward carbon neutrality.

In this context, the University of Fukui and SEIREN CO., LTD. developed and installed a hyperspectral camera on a CubeSat named TIRSAT and conducted an in-orbit demonstration. TIRSAT is a 3U CubeSat developed primarily by SEIREN CO., LTD., managed by Japan Space Systems as a commissioned project for Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). TIRSAT’s primary payload is a bolometer-type camera intended for thermal infrared measurements of Earth’s surface temperature, including heat sources such as factories to estimate operational status. The hyperspectral camera developed by the University of Fukui was installed as an additional payload for in-orbit demonstration. TIRSAT was successfully launched into a sun-synchronous sub-recurrent orbit at an altitude of approximately 680 km on February 17, 2024, by Japan’s H3 launch vehicle. After orbit insertion, the satellite’s basic functions were verified, and mission operations began. The hyperspectral camera on TIRSAT incorporates a linear variable band-pass filter (LVBPF), enabling significant miniaturization suitable for CubeSat integration [

20]. This advancement allows for convenient spectral measurement of ground features and expands the potential of hyperspectral imaging applications. The camera can be easily integrated into CubeSats carrying multiple instruments and is particularly effective for hyperspectral CubeSat constellations.

This paper presents detailed performance specifications of the hyperspectral camera, along with the satellite’s specifications and attitude control results related to TIRSAT observations. It also provides an analysis of the observational data and the in-orbit data processing methods. In particular, LVBPF-based hyperspectral data processing requires precise image alignment, which is critical for data accuracy. This paper proposes a geometric transformation-based alignment method to correct image distortion and discusses the validity of the acquired hyperspectral data.

3. Description of Satellite Bus for TIRSAT

3.1. Introduction of TIRSAT

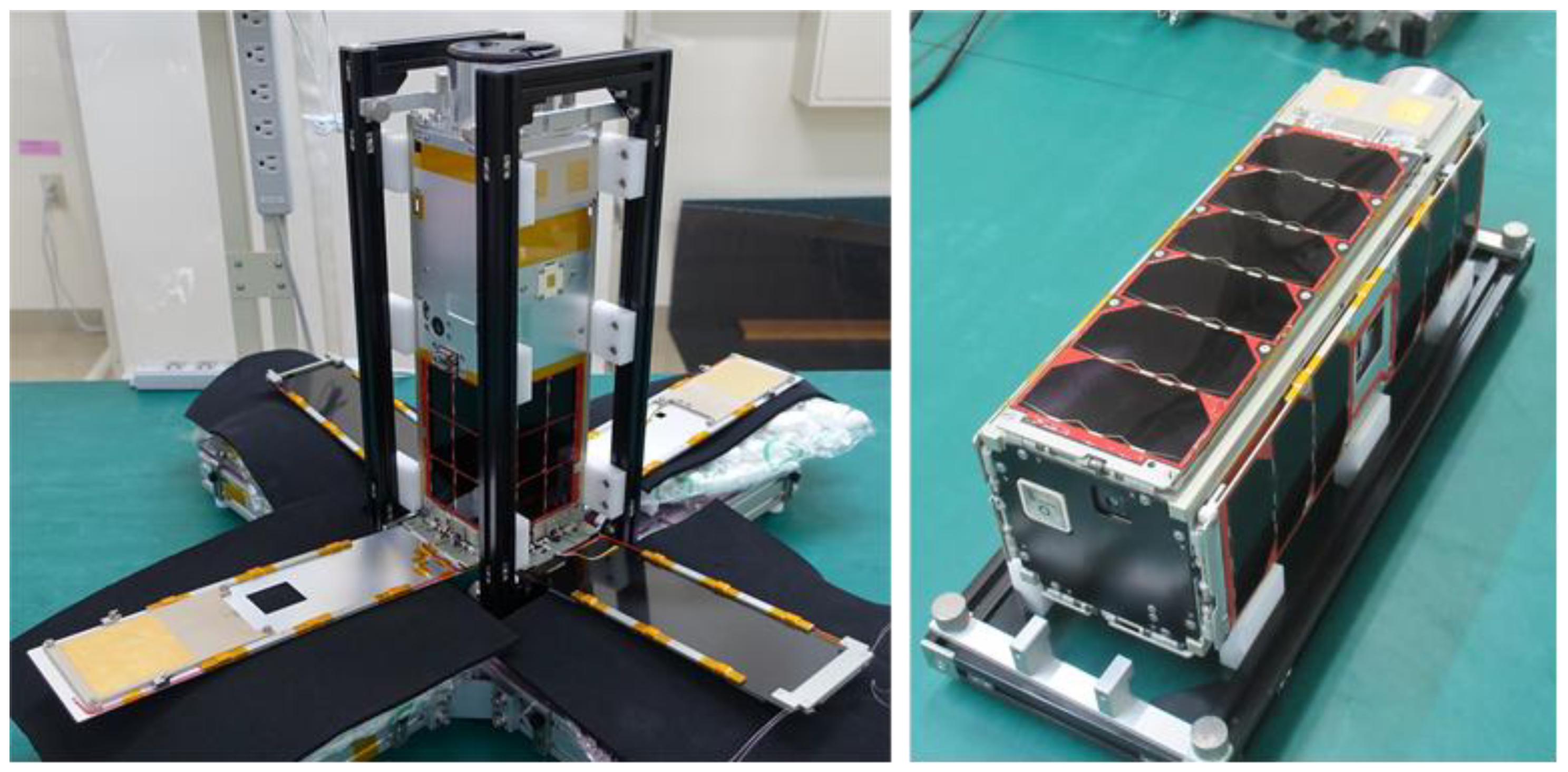

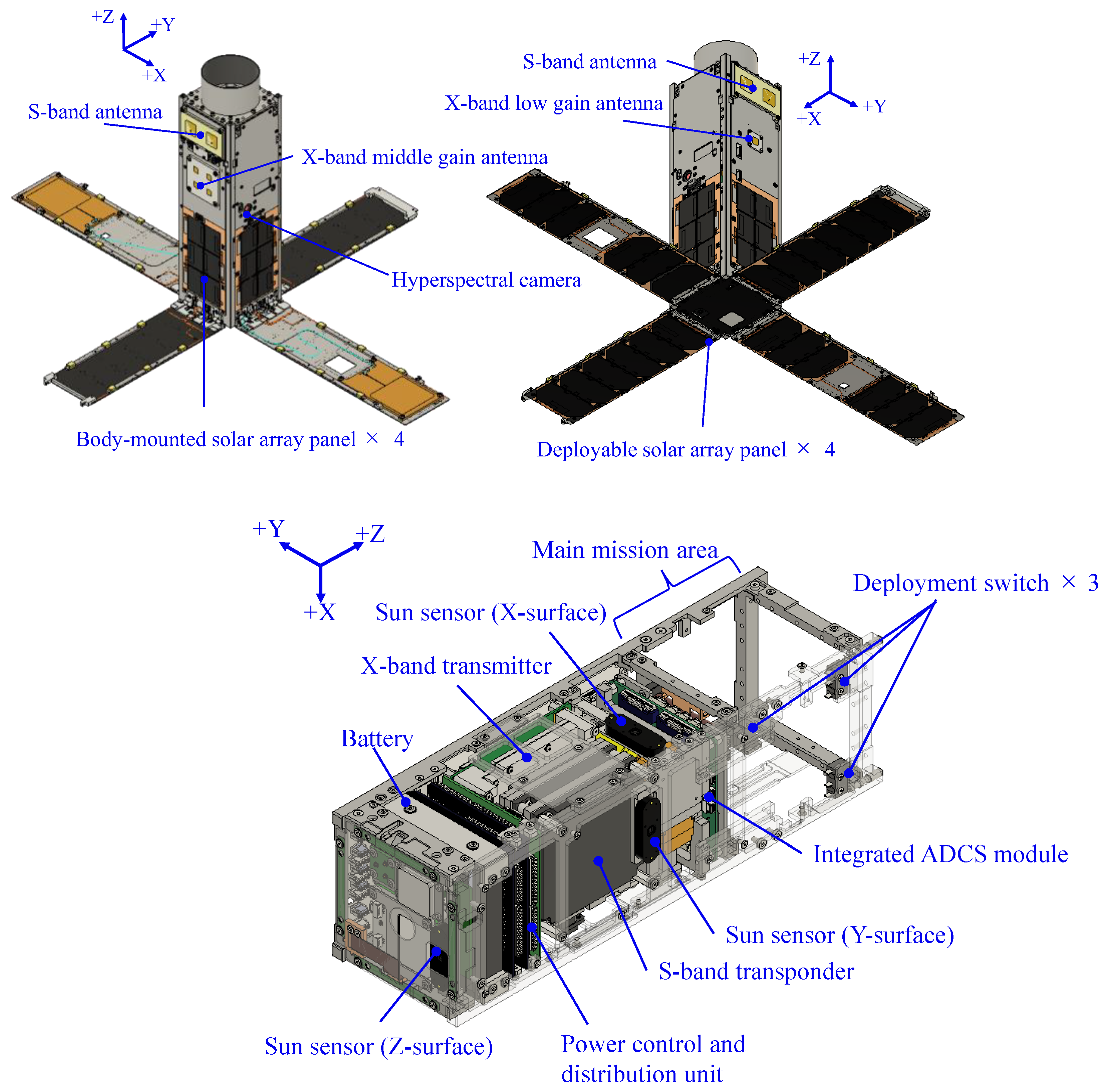

This section outlines the specifications of the TIRSAT satellite. An external view of the satellite flight model is shown in

Figure 8. The satellite measured 117 mm × 117 mm × 381 mm before the deployment of its solar array panels and had a mass of 4.97 kg. It was equipped with a 1U-sized (approximately 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm) bolometer-type camera that operated in the thermal infrared wavelength range as its primary mission payload. Accordingly, the satellite bus occupied approximately 2U of volume. The main specifications of the TIRSAT satellite bus are summarized in

Table 3, and its mechanical configuration is illustrated in

Figure 9.

The satellite bus, named SRN-3U, was developed by SEIREN CO., LTD. in collaboration with the University of Fukui and the University of Tokyo. It was based on the flight heritage of the TRICOM-2 satellite bus [

25,

26], with enhancements including high-speed communication capability, high-precision attitude control, and deployable solar panels. The satellite was designed to be compatible with the ISI Space Quad Pack Type III CubeSat deployer, which matches the release mechanism dimensions of the H3 launch vehicle.

The ground station, equipped with S-band and X-band antennas, is located at ArkEdge Space in Japan. Satellite operations, including pass scheduling, mission planning, and data analysis, are conducted at SEIREN’s satellite operation center in Fukui, Japan. Hyperspectral data acquired by TIRSAT is analyzed at the University of Fukui.

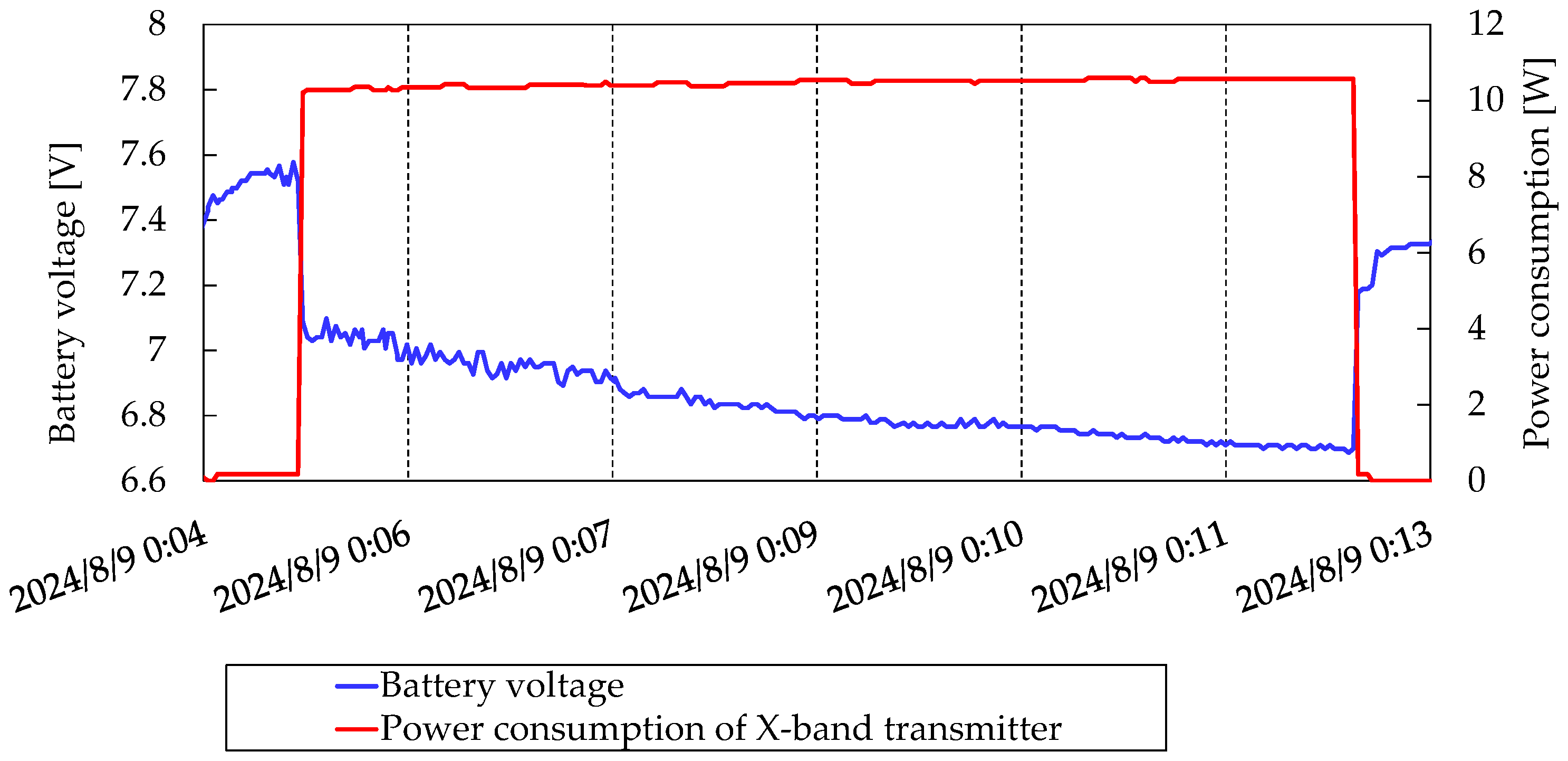

TIRSAT was equipped with an X-band transmitter capable of downlink speeds up to 10 Mbps. It used two types of X-band antennas: a broad-directional low-gain antenna (LGA) and a highly directional medium-gain antenna (MGA). For telemetry and command, an S-band transponder was employed, with antennas mounted on the +Y and −Y panels. These antennas were connected via an RF combiner and splitter, enabling communication in nearly all directions by covering half the space in the +Y or −Y direction.

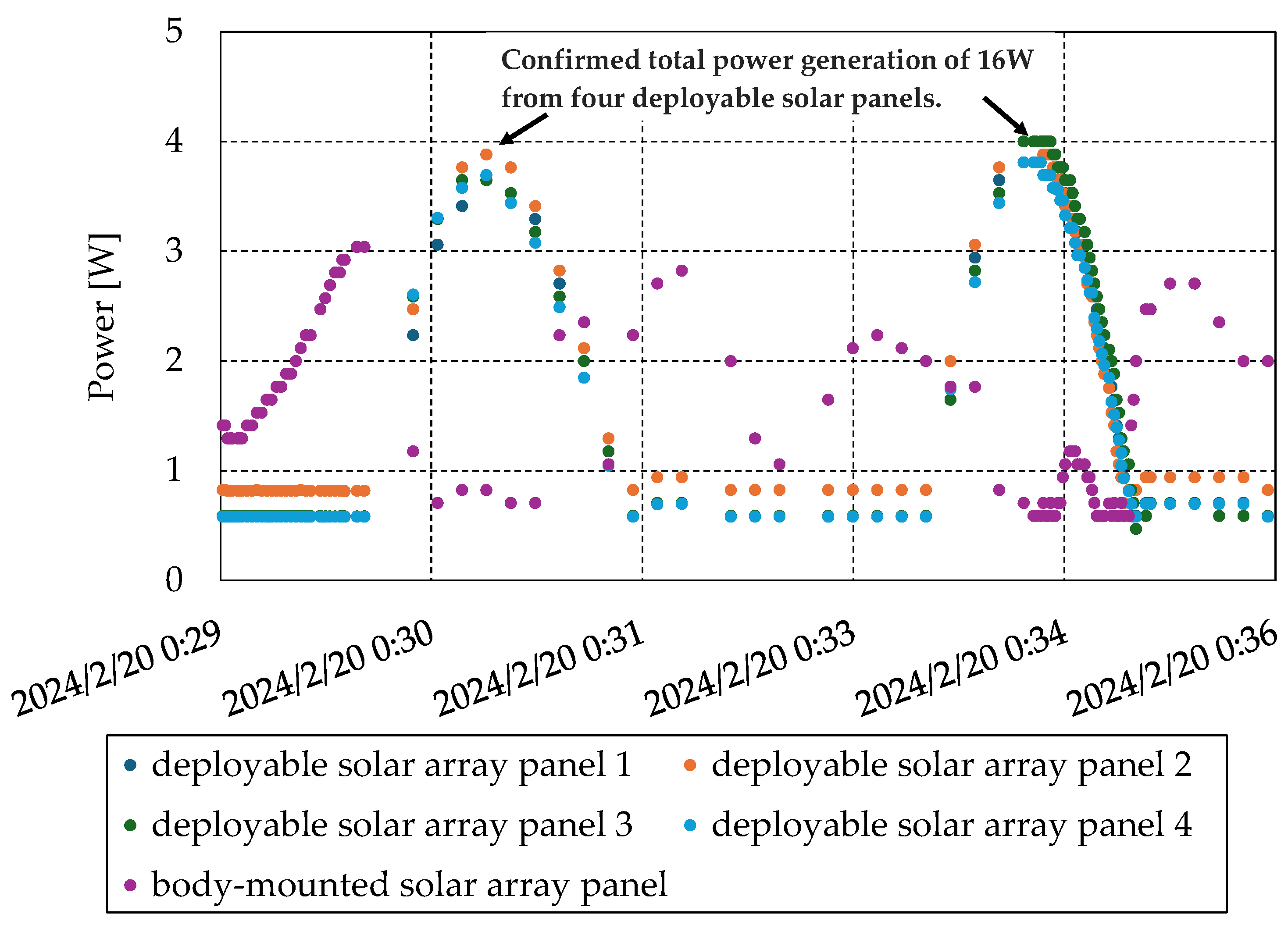

The satellite also featured four deployable solar panels that could generate up to 20 W of effective power. In addition, body-mounted solar cells were installed on four sides of the satellite. This redundant configuration supported stable power generation during the initial operational phase and ensured the power budget was maintained even if sun-pointing control was lost. The satellite's battery consisted of lithium-ion cells arranged in a 2-series, 2-parallel configuration.

The attitude determination and control subsystem (ADCS) was based on a compact 1U-sized integrated module [

27], which was customized for this mission by excluding a star tracker. The onboard computer (OBC) was derived from the TRICOM-2 project and featured a fault-tolerant design that included automatic rebooting approximately every four hours via a reset counter, regardless of operational mode. This served as a countermeasure against single-event faults. Status data was recorded in high-speed, non-volatile memory and retrieved immediately after reboot to ensure continuous operation.

Both the ADCS and OBC employed a command-centric architecture (C2A) for software implementation [

28], providing high flexibility and ease of in-orbit reconfiguration. This architecture defined all satellite actions through commands, enabling functional changes without memory rewriting and allowing software updates to be implemented efficiently in orbit.

3.2. Attitude Determination and Control Subsystem of TIRSAT

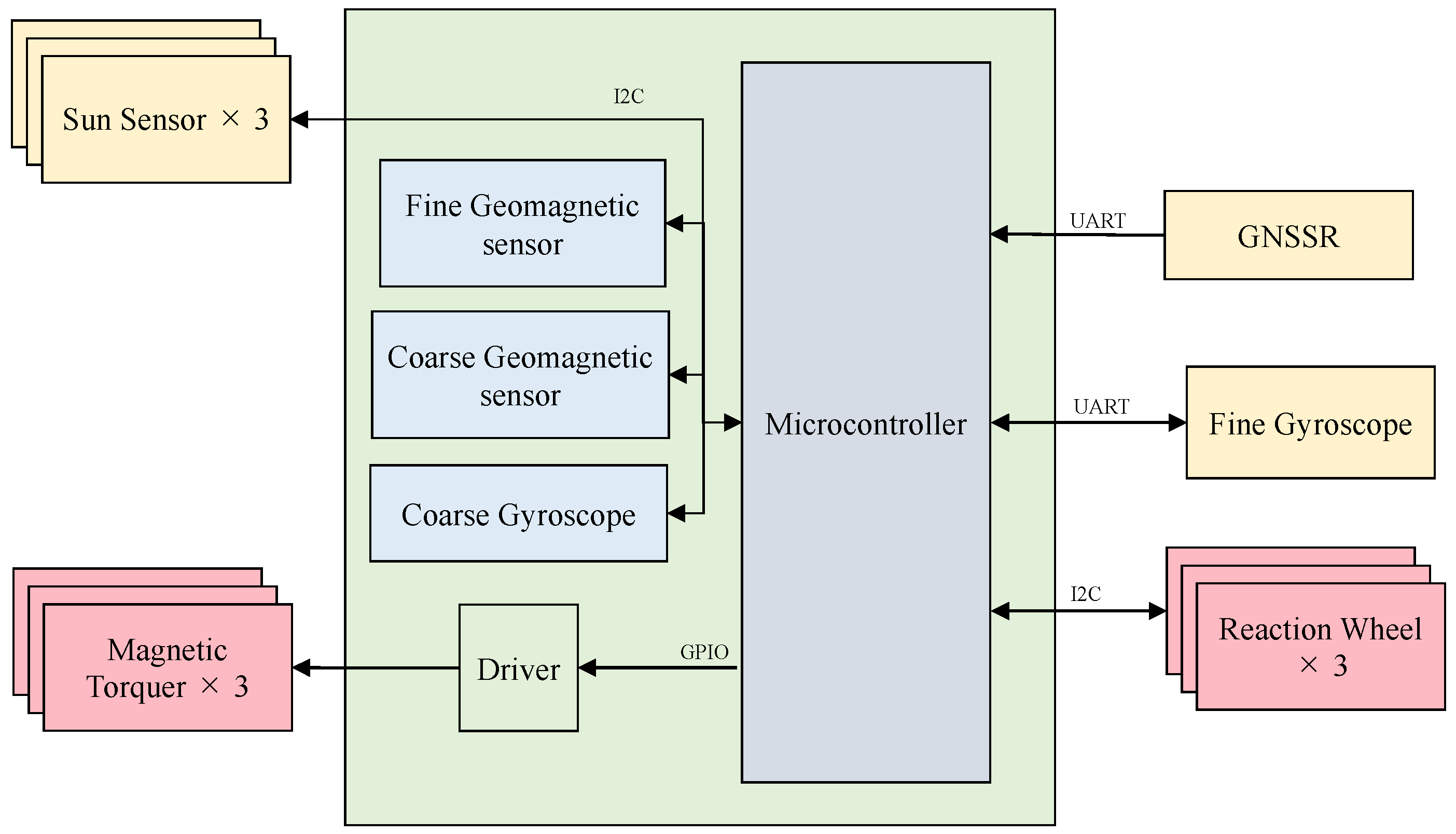

The block diagram of ADCS is presented in

Figure 10, and its specifications are summarized in

Table 4. TIRSAT employed a three-axis attitude control system composed of two microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) gyroscopes, three sun sensors, two geomagnetic sensors, three-axis reaction wheels, and three-axis magnetic torquers, all integrated into a compact ADCS module. Redundant units were included for both the gyroscopes and geomagnetic sensors, with one unit offering fine accuracy and the other coarse accuracy.

Although the ADCS module included a Global Navigation Satellite System Receiver (GNSSR), onboard position determination was primarily performed using the Simplified General Perturbations Satellite Orbit Model 4 (SGP4) and two-line elements (TLEs) uploaded from the ground station. During orbital operations, SGP4 with TLEs was predominantly used for position estimation.

The ADCS software supported multiple control modes, including detumbling using only magnetic torquers, three-axis nadir pointing, and three-axis sun pointing. Each pointing mode was achieved using a combination of three-axis reaction wheels and magnetic torquers, or with magnetic torquers alone. Thus, even in the event of a reaction wheel failure, attitude control could continue with reduced accuracy. Additionally, an offset angle could be applied to each of the three rotational axes—roll, pitch, and yaw—in any pointing mode. As the ADCS was not equipped with a star tracker, attitude determination relied mainly on sun sensors, which offered an accuracy of approximately 0.5°.

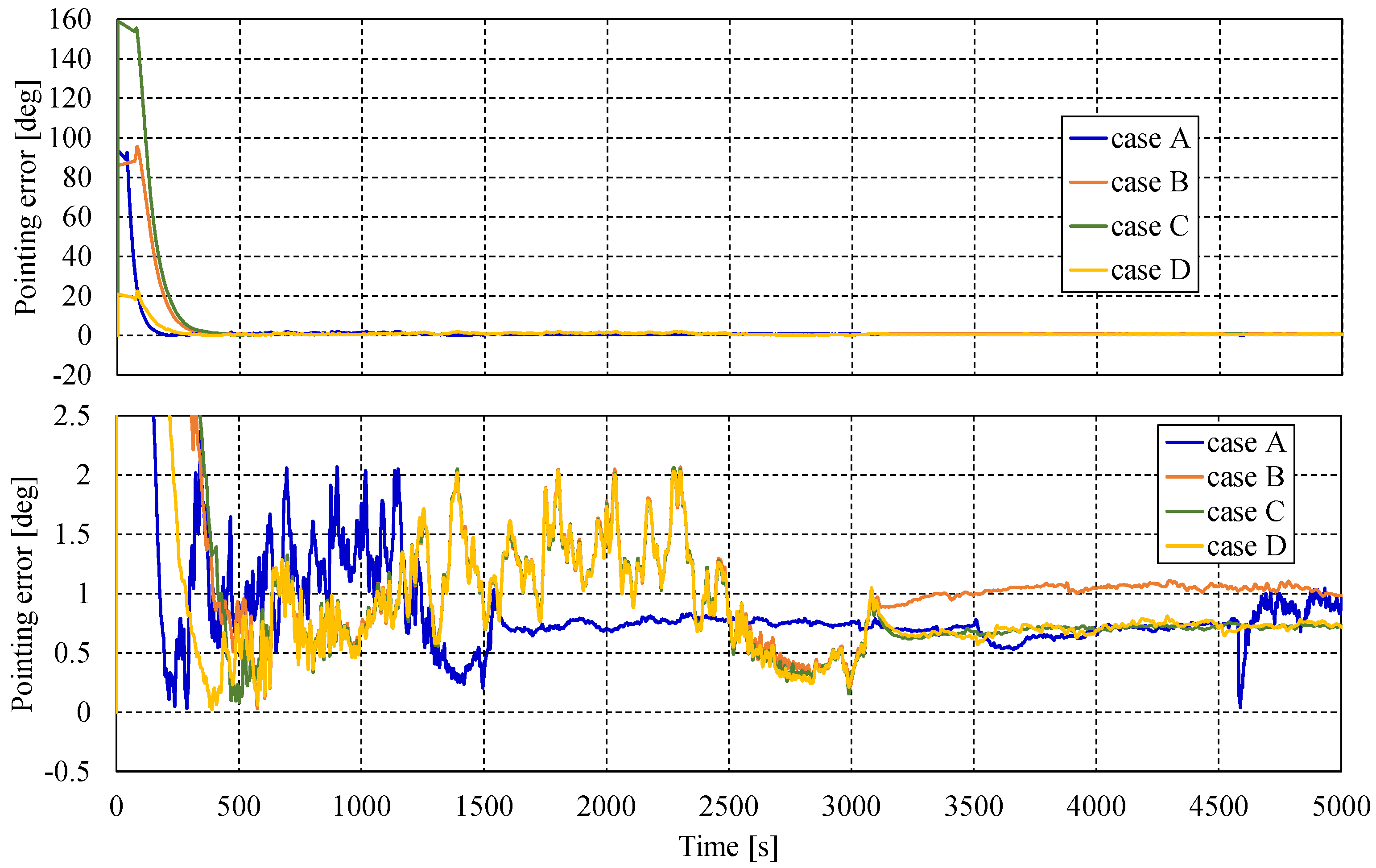

A software-in-the-loop simulation (SILS) was conducted to validate the nadir-pointing control mode. The initial angular velocity for all axes was set to 0.1°/s, and the simulation commenced under daylight conditions. The satellite was assumed to be in a Sun-synchronous orbit at an altitude of 580 km. Initial attitude conditions were defined such that in Case A, the −X surface was oriented toward the Sun, while in Cases B to D, offset angles were applied to each axis. As shown in

Figure 11, the simulation results indicated that the attitude convergence time was within 400 seconds and the pointing error was maintained within 2°. Furthermore, after 3000 seconds, the attitude remained stable with a pointing error of less than 1°.

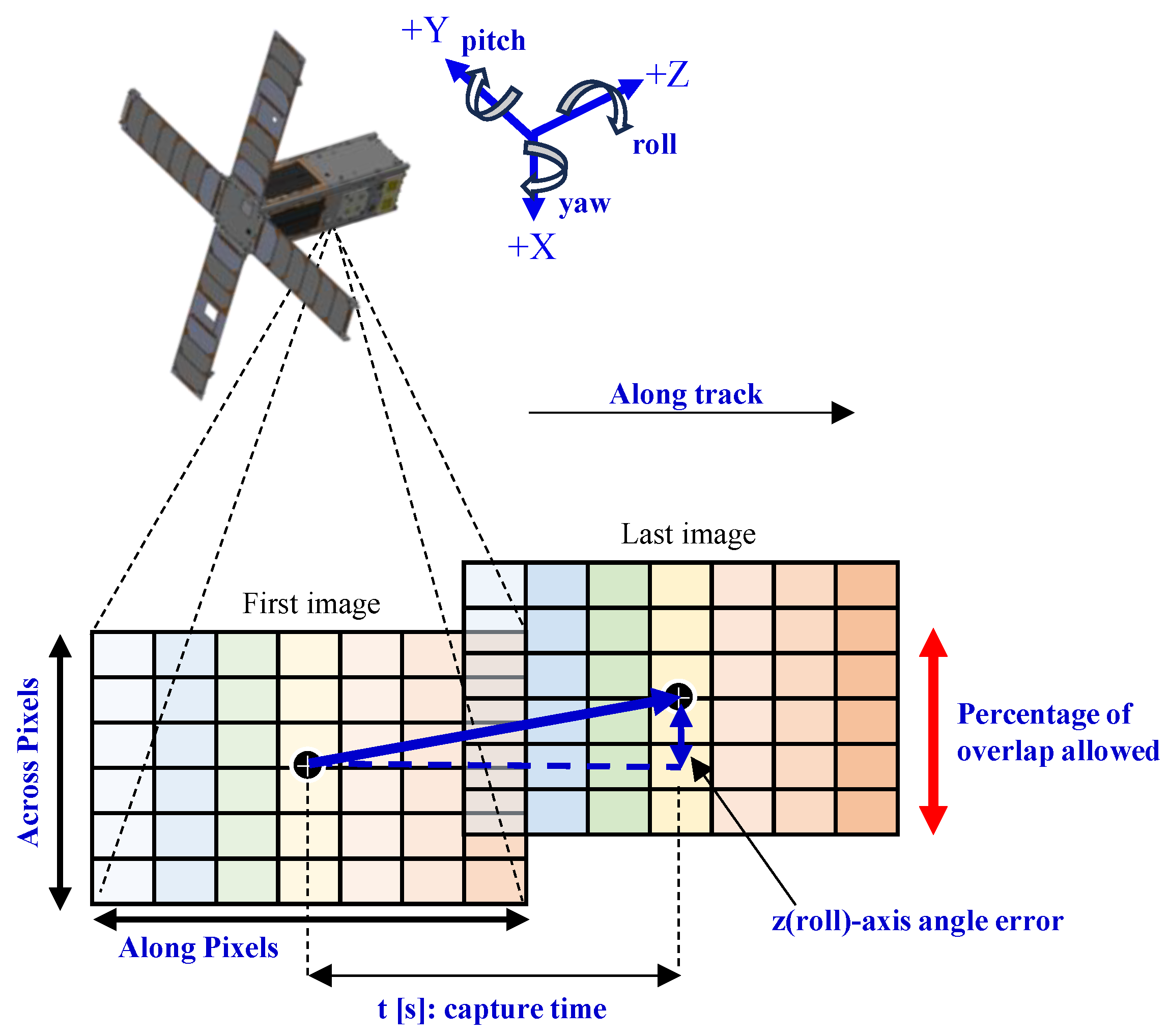

The target values for attitude control in the hyperspectral imaging mission are presented in

Table 5. The target pointing control angle was set to 7.3°, corresponding to a positional difference of 200 pixels between the target location and the captured image. Because the hyperspectral camera utilized a linear variable band-pass filter (LVBPF), spectral direction pixels had to align with the along-track direction. As a result, high precision was required for yaw-axis attitude control and roll-axis attitude stability. A conceptual diagram illustrating these requirements is shown in

Figure 12.

The required yaw-axis attitude accuracy was derived using Equation (1), where α denotes the acceptable overlap ratio between the first and last images, and IFOV (instantaneous field of view) represents the angle per pixel, which was 0.038° for the hyperspectral camera. Assuming an allowable overlap ratio of 70%, the required yaw-axis pointing accuracy was calculated to be 5.8°. Moreover, the roll-axis angle during imaging needed to be maintained within 5.8° of its initial value.

The required image capture duration was calculated using Equation (2). At an orbital altitude of 680 km, TIRSAT’s orbital velocity was approximately 7.5 km/s, and its ground sampling distance (GSD) was 450 m/pixel, as shown in

Table 1. Given an along-track pixel count of 1024, the required image capture time was estimated to be approximately 120 seconds. During this period, the roll-axis angle had to remain within 5.8°, yielding a required attitude stability of 0.048°/s. Based on the SILS results, the ADCS of TIRSAT demonstrated sufficient capability to meet these pointing and stability requirements.

3.3. Mission Data Handling and Communication Subsystem

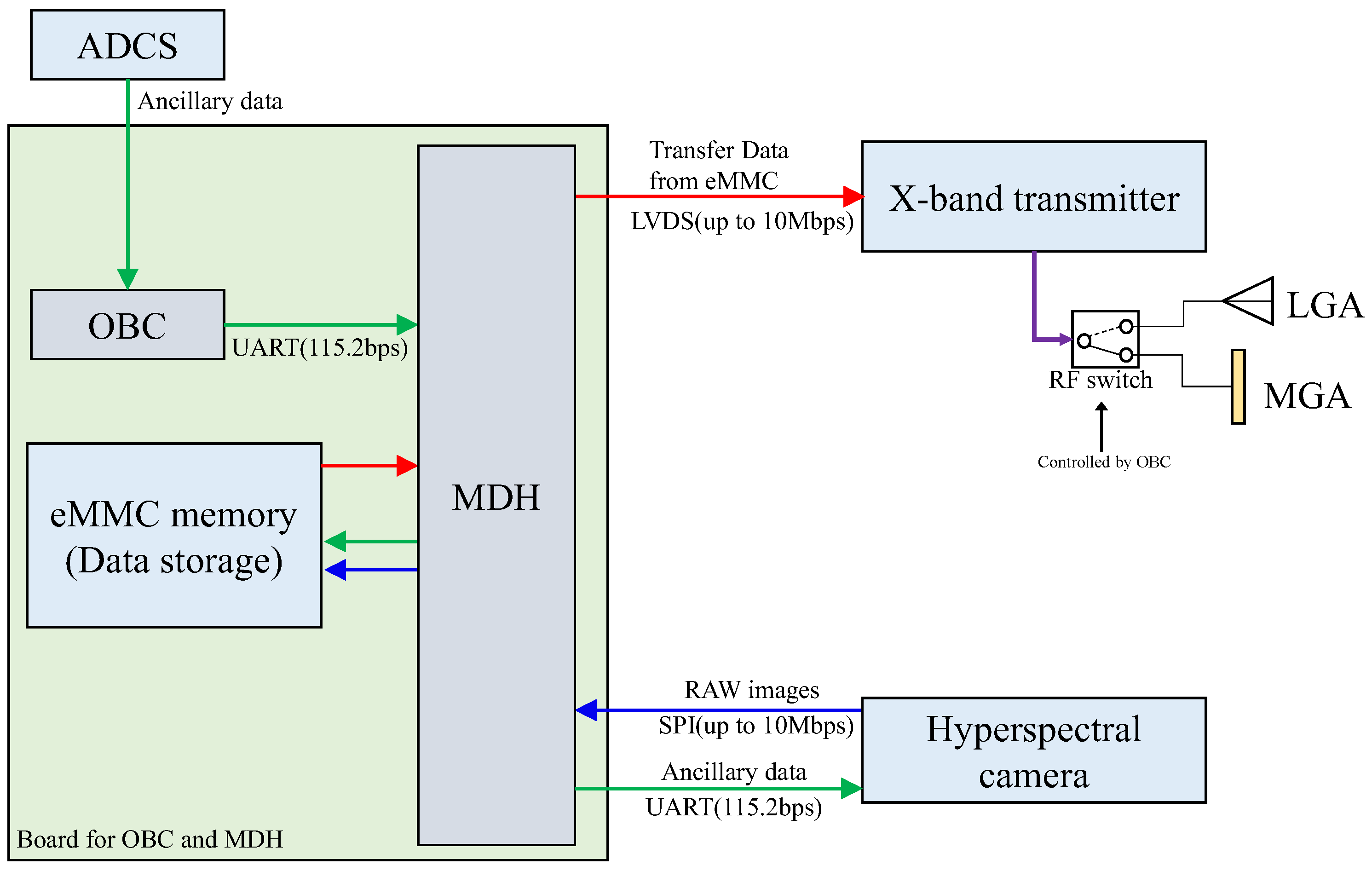

The control of the mission payload, including the hyperspectral camera, was managed by the mission data handling unit (MDH), which was developed using a field-programmable gate array (FPGA). Mission data transmission to the ground station was carried out using the X-band transmitter. The block diagram of the mission processing and communication subsystem is shown in

Figure 13. As previously mentioned, the hyperspectral camera was controlled by a Raspberry Pi. Captured images were transferred to the MDH via Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) communication. The MDH stored the received raw images in the embedded multimedia card (eMMC) memory, which served as the data storage. The eMMC memory had a total capacity of 8GB, with 1GB allocated for the hyperspectral camera. The data read from the eMMC memory was transmitted to the ground station through the X-band transmitter, using a data format compliant with the Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems (CCSDS) standard.

To perform map projection, satellite attitude and position data corresponding to the image timestamp were required. These ancillary data were transmitted from the ADCS module and transferred to the hyperspectral camera via the onboard computer (OBC) and MDH. The ancillary data were appended to the header of the raw image and also stored in the eMMC memory. The MDH and eMMC memory utilized commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components, which were newly developed. It was confirmed that these components had a radiation tolerance exceeding 20 krad. Proton irradiation experiments also evaluated their single-event resilience, and the results confirmed that these components were sufficiently capable of functioning in orbit.

The X-band transmitter supported downlink communication speeds of 5 Mbps or 10 Mbps using Offset Quadrature Phase Shift Keying (OQPSK) modulation. The output power of the transmitter could be set to 1 W or 2 W. TIRSAT was equipped with a single patch array antenna as the Low Gain Antenna (LGA) and a 2×2 patch array antenna as the Medium Gain Antenna (MGA). These antennas could be switched using an RF switch. The maximum gain of the LGA was 4 dBi, while the MGA had a maximum gain of 10 dBi. The LGA was mounted on the +Y surface, and the MGA was mounted on the −Y surface. The half-power beamwidth was ±35° for the LGA and ±20° for the MGA. While attitude control was required during X-band communication, coarse attitude control sufficed when using the LGA.

4. Data Construction Method for LVBPF-Based Hyperspectral Data

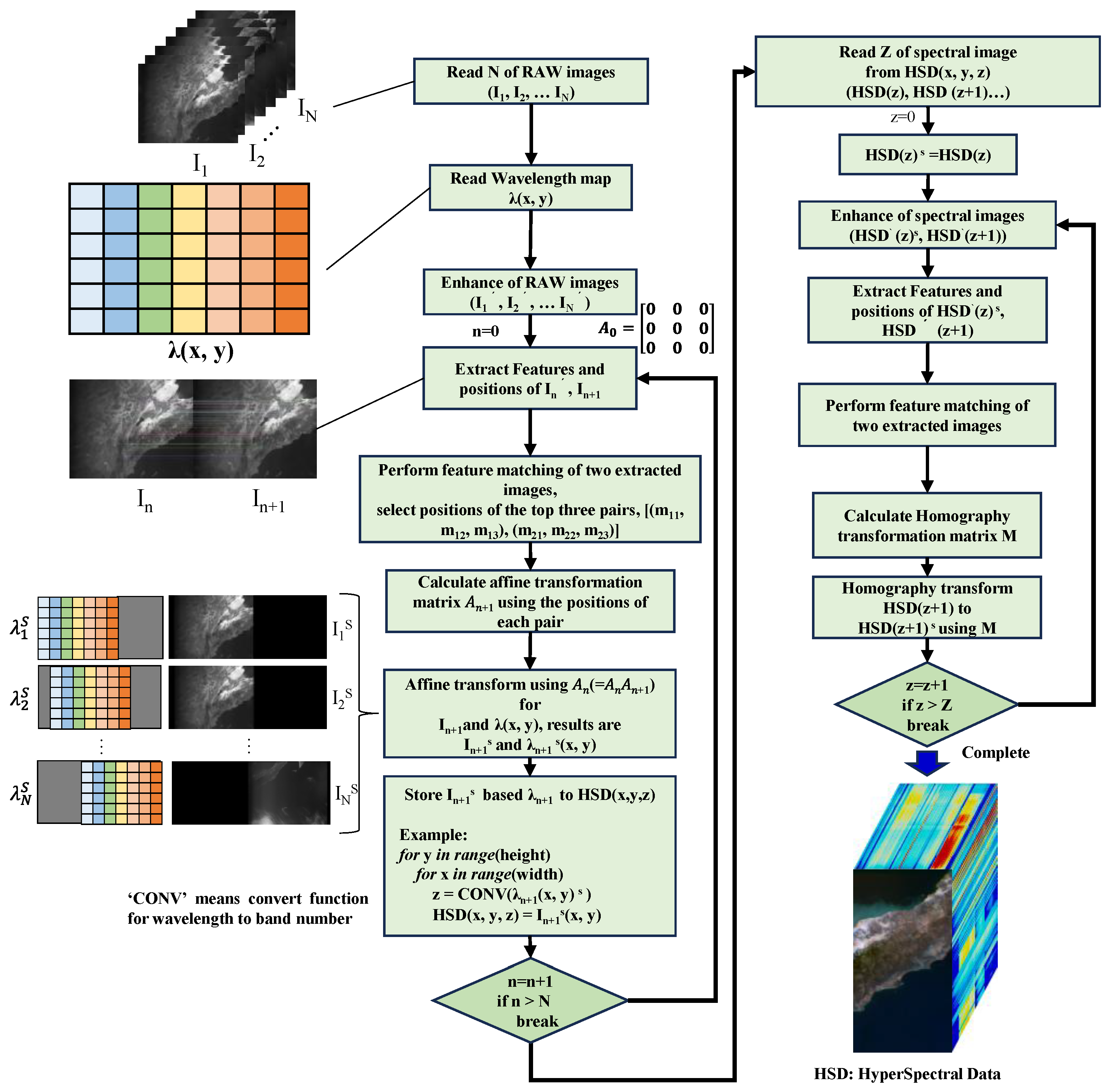

The images acquired using an LVBPF capture different transmission wavelengths in the along-track direction. Therefore, a single image represents a mixture of spatial and spectral information. Spectral images are captured at various positions using push-broom observations to capture the same wavelength, with the overlapping parts of each image synthesized to generate a spectral image, forming hyperspectral data. In general, push-broom imaging sequentially synthesizes images at regular intervals. However, factors such as lens distortion, parallax at the capture position, and attitude instability can affect image alignment. As a result, when overlapping regions are synthesized using only temporal capture information, the resulting hyperspectral data exhibit distortions, and the individual spectral images do not align properly. To address this, we estimated overlap coordinates using image feature point matching and homography transformation, synthesizing the images to generate corrected hyperspectral data.

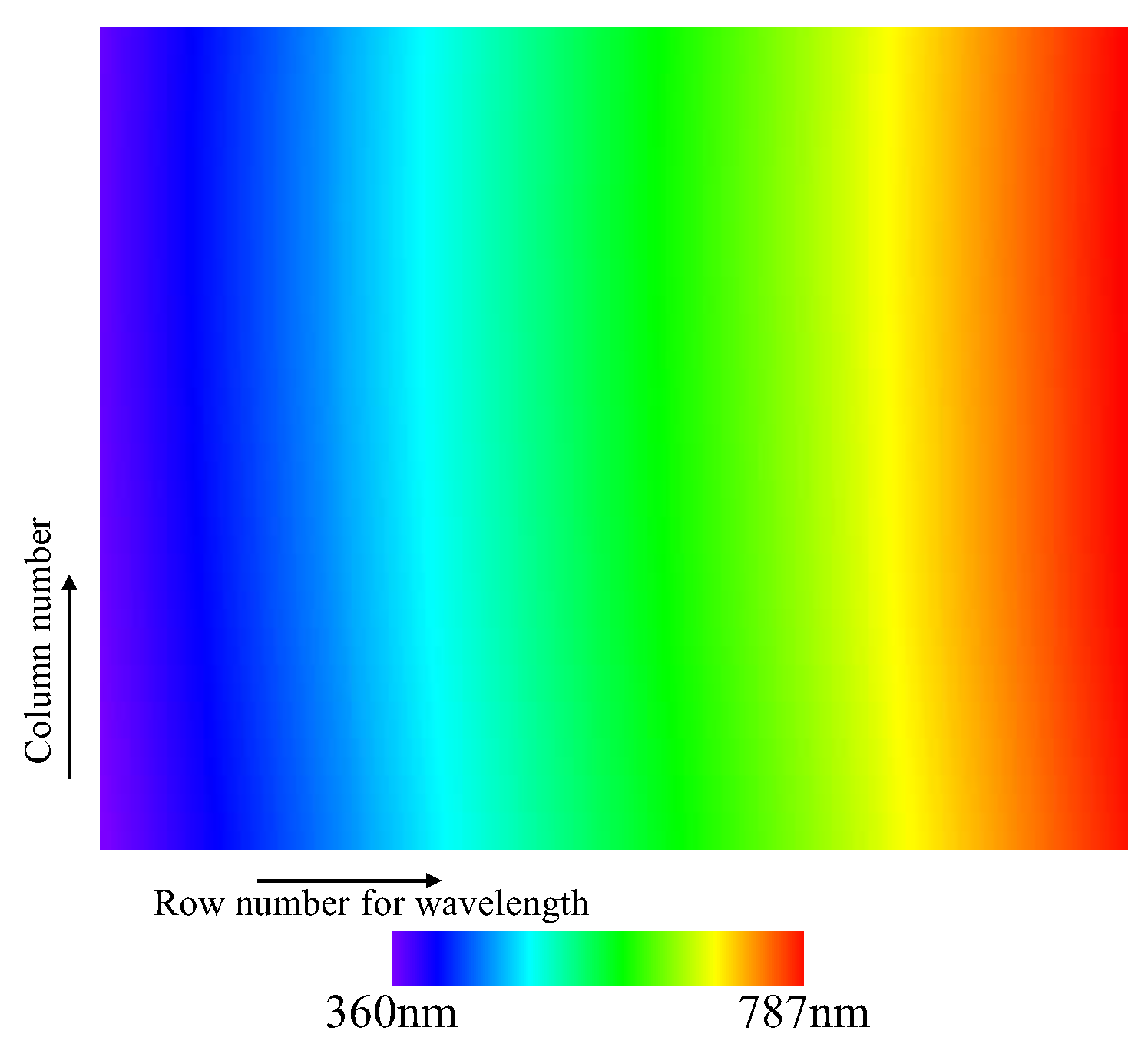

The data construction method is illustrated in

Figure 14. This process is divided into two stages. The first step involves feature point matching to automatically detect the overlapping regions of each image. Displacement between the images is then estimated, and alignment is achieved using affine transformation. The images used in this step are raw data captured by the LVBPF-based hyperspectral camera, referred to as RAW images. Each RAW image is accompanied by a wavelength map that indicates the transmission wavelength for each pixel, as shown in

Figure 6. These RAW images contain distortions due to lens and parallax effects and represent unprocessed data. Feature point matching is performed between the first image (

In) and the following image (

In+1). To facilitate feature point matching, the RAW images undergo image enhancement processes such as contrast enhancement and sharpening. Gamma correction was applied for contrast enhancement, and unsharp masking was used for sharpening. Accelerated Keypoint and Descriptor Extraction (AKAZE) was employed for feature point detection.

After applying these enhancements, the top three feature point pairs identified were selected, and affine transformation was performed. The wavelength map was transformed using the same matrix applied to the images. This process was repeated for each image captured by the hyperspectral camera, yielding affine-transformed RAW images and corresponding wavelength maps, which were stored in a three-dimensional structure to form the hyperspectral data.

At this stage, the RAW image and wavelength map were affine-transformed, meaning only operations such as translation or rotation were applied. While this step resulted in roughly aligned hyperspectral data, distortions due to parallax and other factors were not removed, and the images did not align perfectly. The next step involved performing a homography transformation based on feature point matching between the generated hyperspectral data to correct position and distortion simultaneously. The result was distortion-free and properly aligned hyperspectral data.

The spectral images for each band were read from the hyperspectral data, and the positions of feature points were extracted. Feature point detection and extraction were performed using the same method as in the first step. The complete set of extracted feature point pairs was then used with Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) to compute the homography transformation matrix. RANSAC is an iterative algorithm used to estimate a model from data containing outliers. All spectral images, except for the reference image, were transformed using this matrix and stored in the final hyperspectral data.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents the results of observations made using the LVBPF-based hyperspectral camera installed on TIRSAT. The hyperspectral camera covers the visible to near-infrared spectral range and has successfully acquired hyperspectral data over a broad ground surface area. Regular imaging experiments are ongoing, and this paper outlines and validates a proposed method for constructing LVBPF-based hyperspectral data. The method involves removing coarse alignment using affine transformation to account for parallel movement, followed by the application of homography transformation to correct distortions, such as parallax. The effectiveness of this data construction method has been validated by on-orbit results.

Despite TIRSAT being a small 3U-CubeSat, its satellite bus has demonstrated the ability to fully meet the observation requirements of the camera. This confirms that high-precision attitude control can be achieved at a low cost. Additionally, other subsystems, such as the X-band communication system and mission data handling, have proven sufficient to operate the hyperspectral camera, as demonstrated by the on-orbit results.

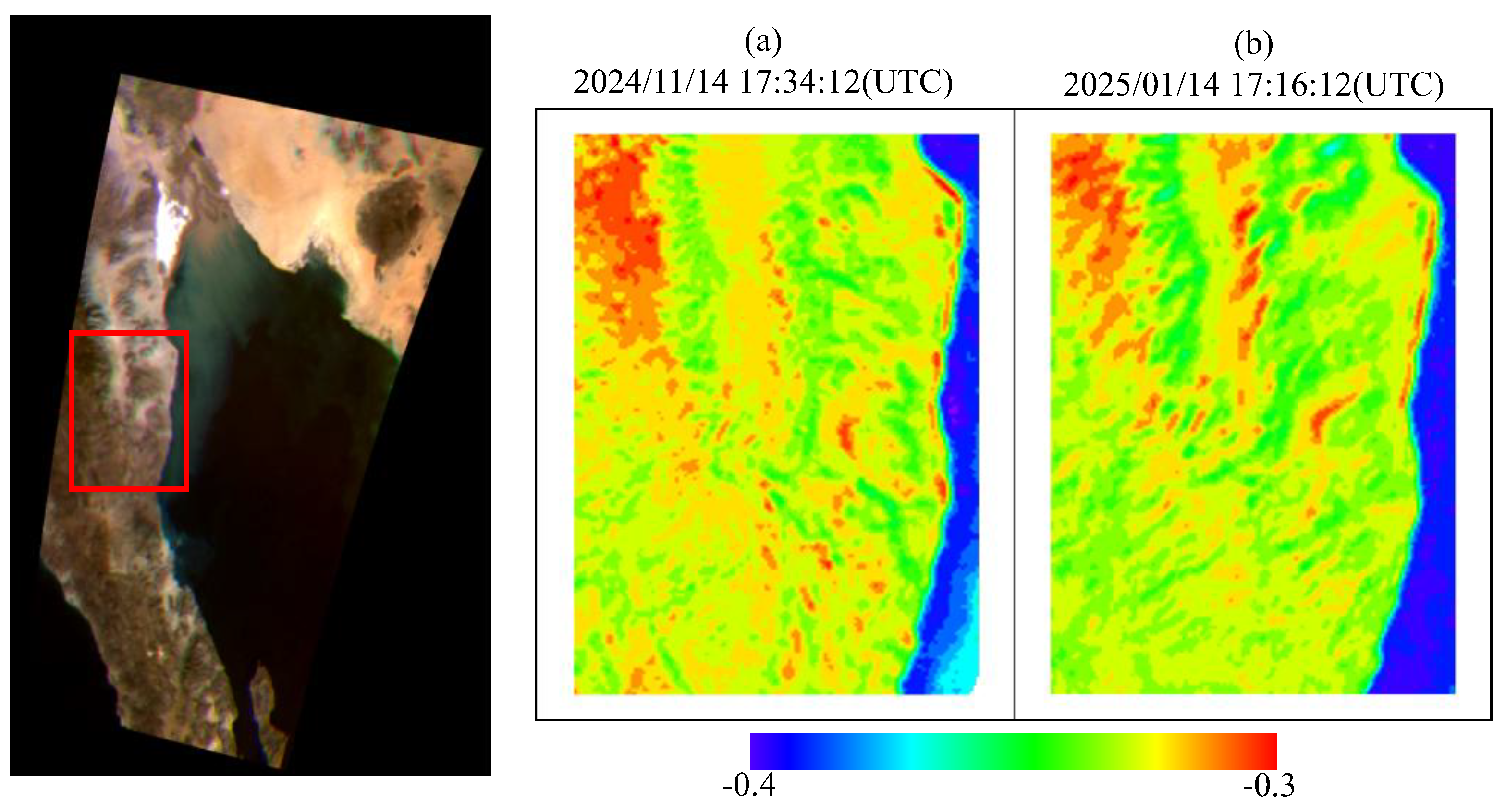

To validate the consistency of the hyperspectral data acquired by TIRSAT, a successful comparison analysis between two time periods was conducted. No issues were found with geospatial accuracy or spectral data stability.

In conclusion, both the LVBPF-based hyperspectral camera and the TIRSAT satellite bus have demonstrated their capabilities in orbit. Future plans include further verifications for practical use, radiometric calibrations, and obtaining spectral reflectance data. The LVBPF-based hyperspectral camera also offers flexibility by allowing filter replacements to change spectral characteristics and the convenience of replacing the telescope lens. Additionally, the high optical transmission of the filters enhances spatial resolution. We plan to develop a hyperspectral camera with higher spatial resolution suitable for CubeSat applications.

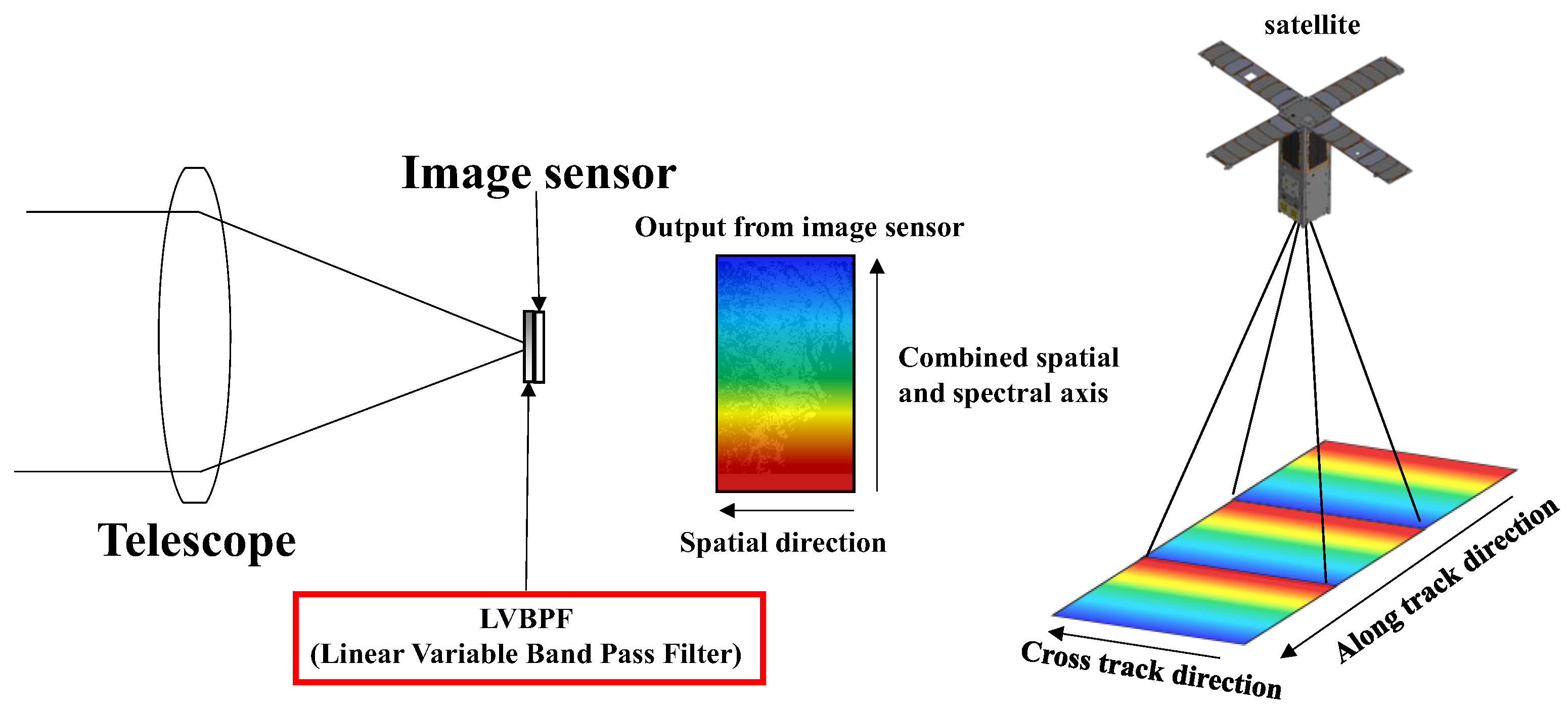

Figure 1.

Configuration and observation method of the LVBPF-based hyperspectral camera.

Figure 1.

Configuration and observation method of the LVBPF-based hyperspectral camera.

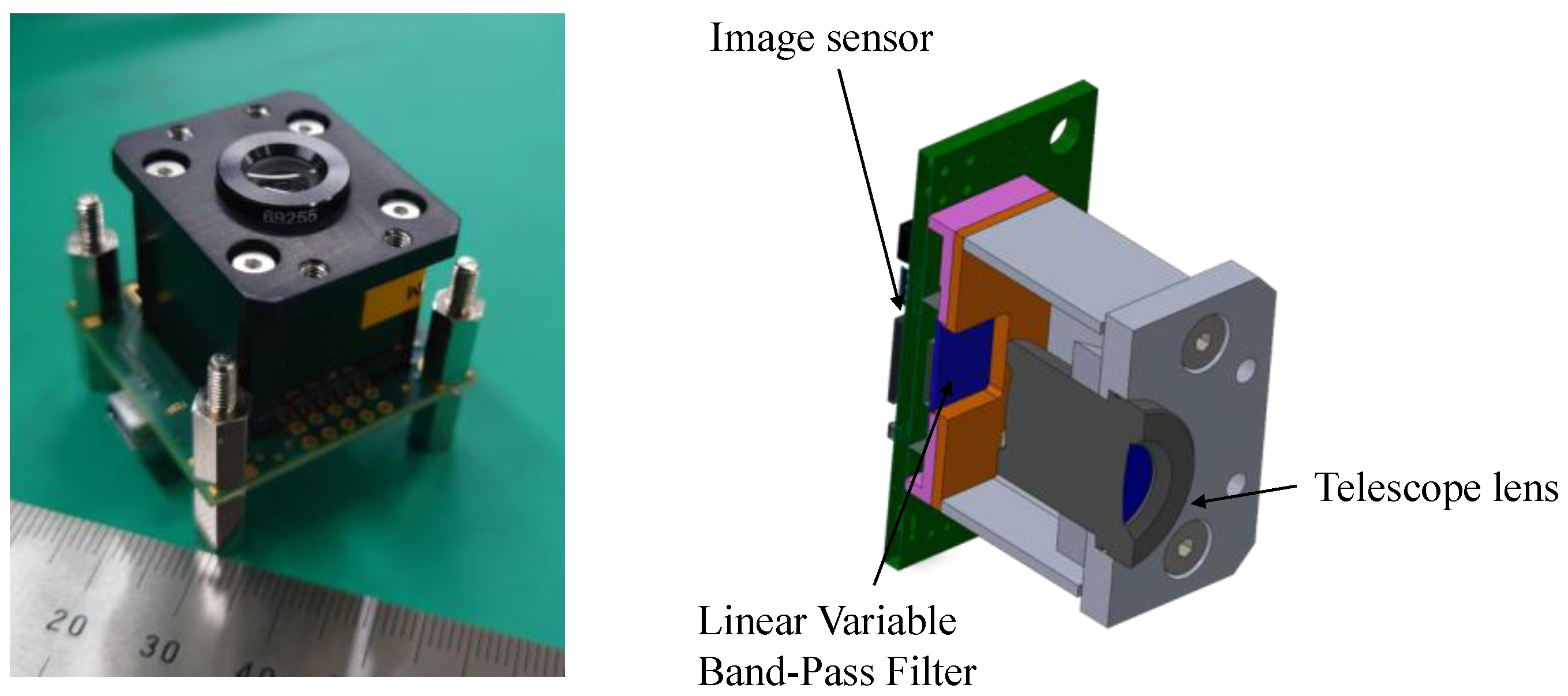

Figure 2.

Exterior view and mechanical configuration of the LVBPF-based hyperspectral camera.

Figure 2.

Exterior view and mechanical configuration of the LVBPF-based hyperspectral camera.

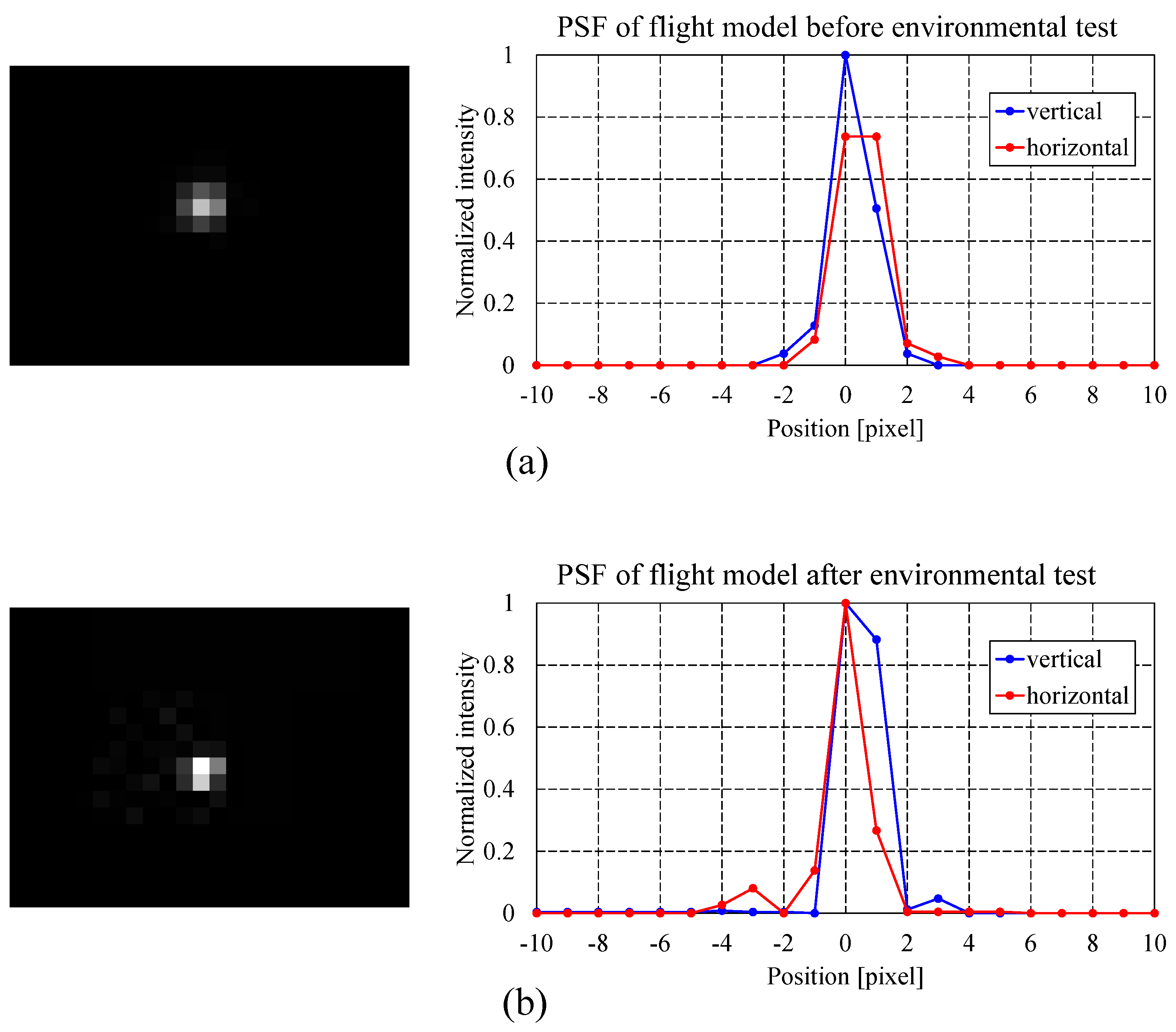

Figure 3.

Point spread function of the hyperspectral camera flight model: (a) before environmental testing; (b) after environmental testing.

Figure 3.

Point spread function of the hyperspectral camera flight model: (a) before environmental testing; (b) after environmental testing.

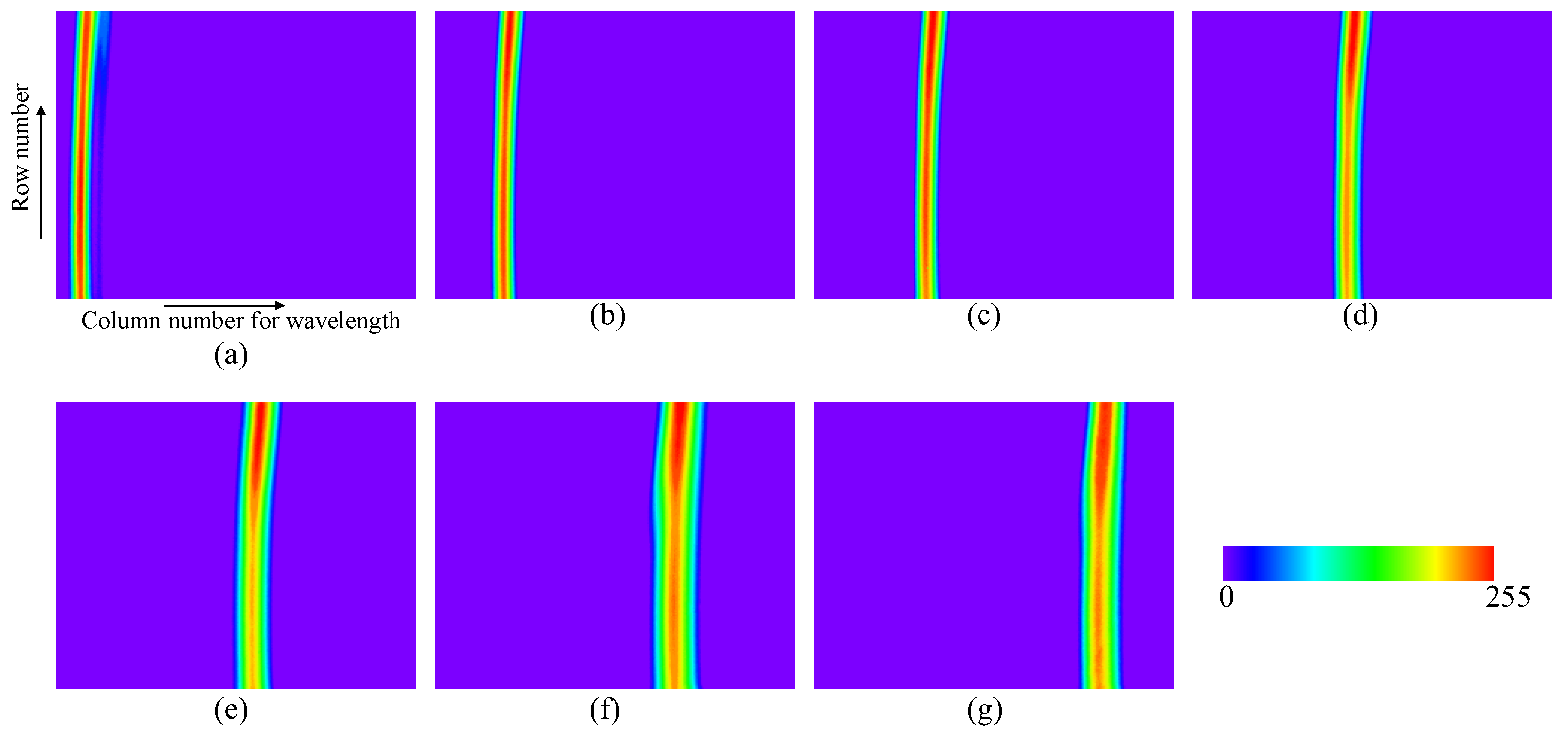

Figure 4.

Spectral image acquired by the hyperspectral camera flight model across spectral bands of (a) 400 nm, (b) 450 nm, (c) 500 nm, (d) 550 nm, (e) 600 nm, (f) 650 nm, and (g) 700 nm.

Figure 4.

Spectral image acquired by the hyperspectral camera flight model across spectral bands of (a) 400 nm, (b) 450 nm, (c) 500 nm, (d) 550 nm, (e) 600 nm, (f) 650 nm, and (g) 700 nm.

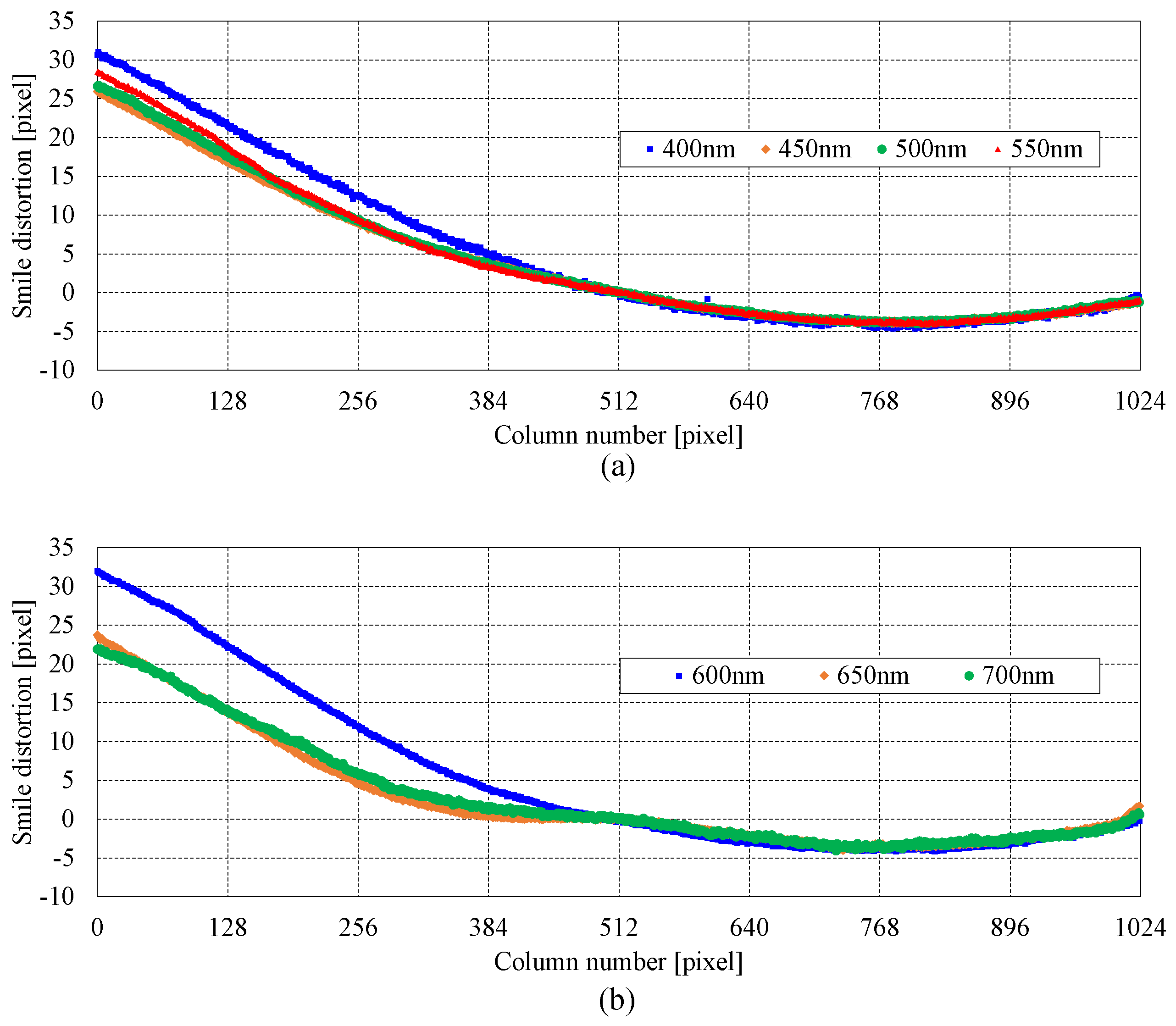

Figure 5.

Smile distortion the hyperspectral camera flight model across spectral bands of (a) 400 nm, 450 nm, 500 nm, and 550 nm, (b) 600 nm, 650 nm, and 700 nm.

Figure 5.

Smile distortion the hyperspectral camera flight model across spectral bands of (a) 400 nm, 450 nm, 500 nm, and 550 nm, (b) 600 nm, 650 nm, and 700 nm.

Figure 6.

Calibrated wavelength map of the hyperspectral camera flight model.

Figure 6.

Calibrated wavelength map of the hyperspectral camera flight model.

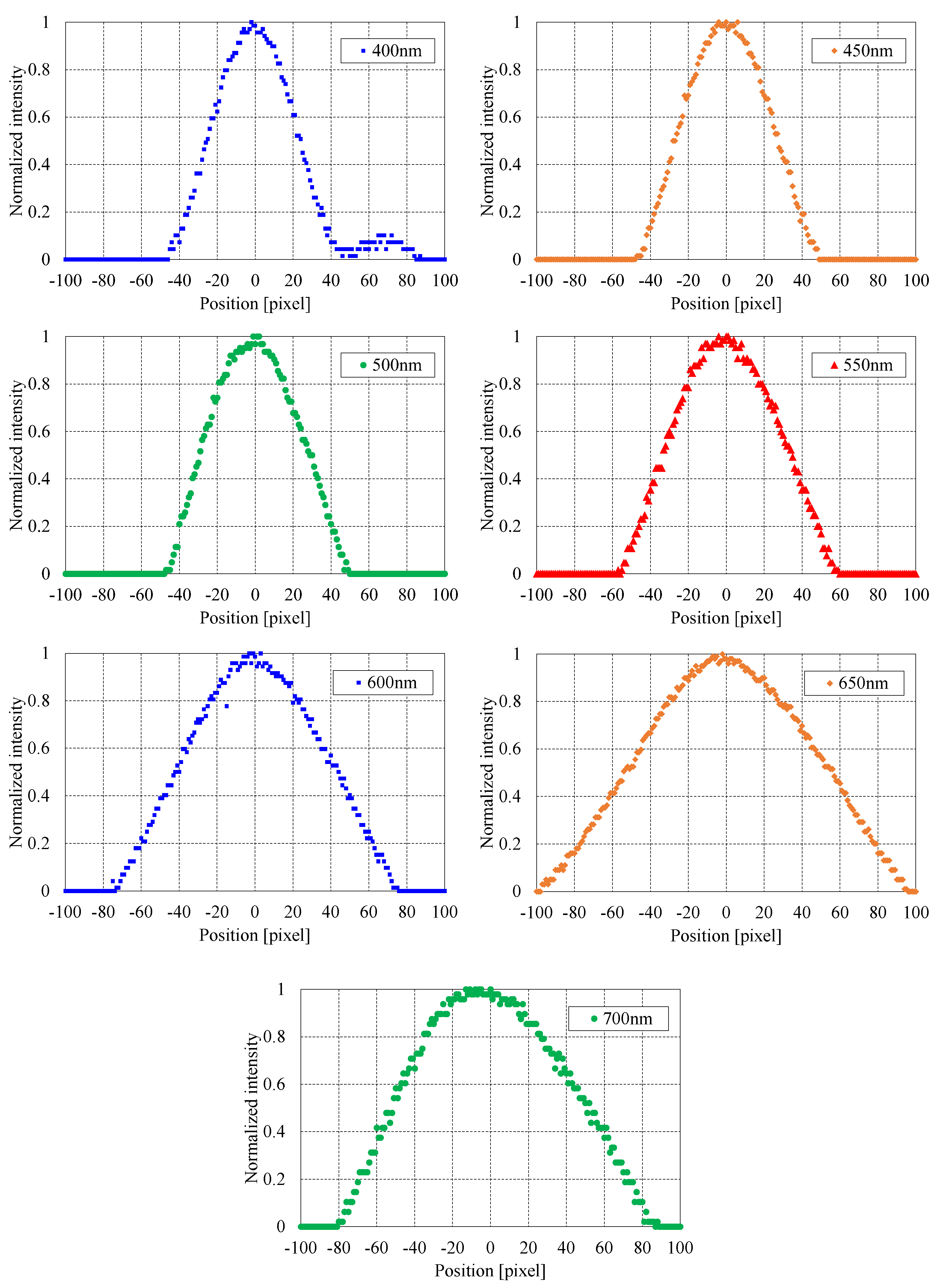

Figure 7.

Spectral resolution of each band in the hyperspectral camera flight model.

Figure 7.

Spectral resolution of each band in the hyperspectral camera flight model.

Figure 8.

Flight model of TIRSAT.

Figure 8.

Flight model of TIRSAT.

Figure 9.

Mechanical configuration of TIRSAT.

Figure 9.

Mechanical configuration of TIRSAT.

Figure 10.

Configuration of the ADCS onboard TIRSAT.

Figure 10.

Configuration of the ADCS onboard TIRSAT.

Figure 11.

Simulation results of pointing control error using SILS. Case A: –X surface faces the Sun; Case B: quaternion = [0.5, –0.5, –0.5, 0.5]; Case C: quaternion = [0.5, –0.5, 0.5, –0.5]; Case D: quaternion = [0, 0, 0.707, –0.707]; Case E: quaternion = [0.707, –0.707, 0, 0]. Upper panel: overall results; lower panel: magnified view.

Figure 11.

Simulation results of pointing control error using SILS. Case A: –X surface faces the Sun; Case B: quaternion = [0.5, –0.5, –0.5, 0.5]; Case C: quaternion = [0.5, –0.5, 0.5, –0.5]; Case D: quaternion = [0, 0, 0.707, –0.707]; Case E: quaternion = [0.707, –0.707, 0, 0]. Upper panel: overall results; lower panel: magnified view.

Figure 12.

Schematic of attitude control accuracy and stability concept.

Figure 12.

Schematic of attitude control accuracy and stability concept.

Figure 13.

System block diagram of the mission data handling system and X-band transmitter.

Figure 13.

System block diagram of the mission data handling system and X-band transmitter.

Figure 14.

Data construction procedure for LVBPF-based hyperspectral data.

Figure 14.

Data construction procedure for LVBPF-based hyperspectral data.

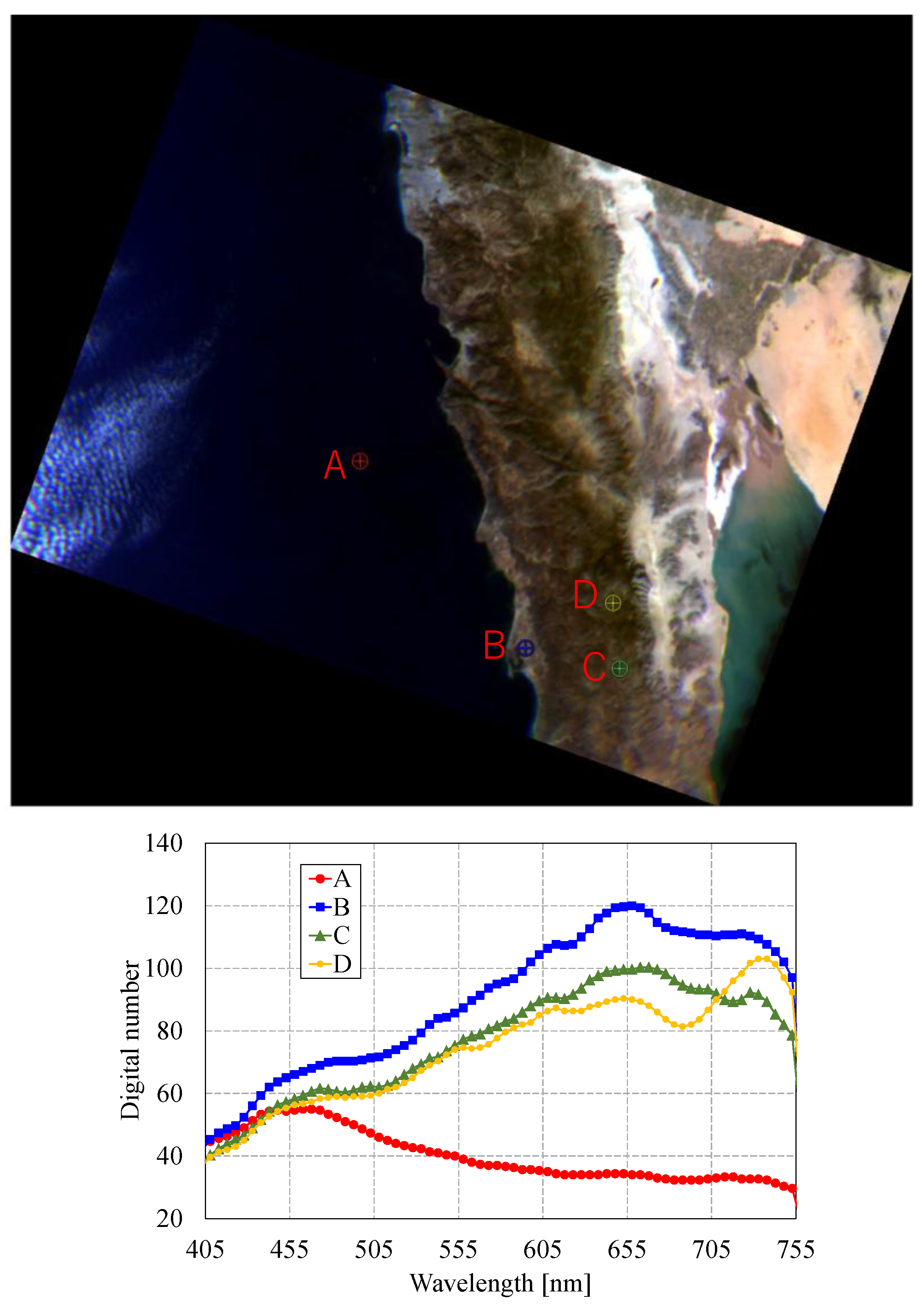

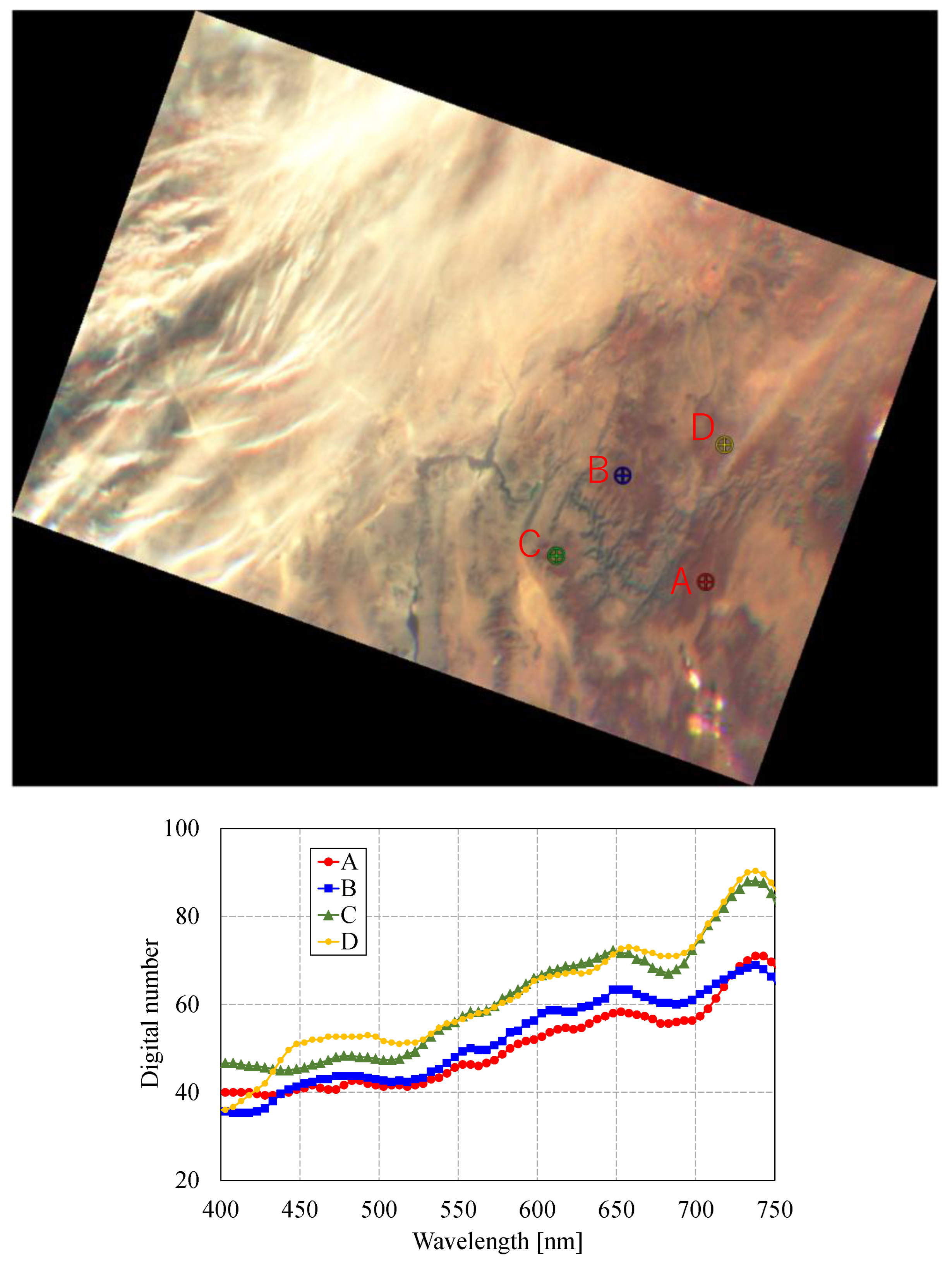

Figure 15.

Composite image (467 nm, 547 nm, and 637 nm) and corresponding spectral data at locations A, B, C, and D (2024-11-14 17:34:12 UTC, Baja California, Mexico).

Figure 15.

Composite image (467 nm, 547 nm, and 637 nm) and corresponding spectral data at locations A, B, C, and D (2024-11-14 17:34:12 UTC, Baja California, Mexico).

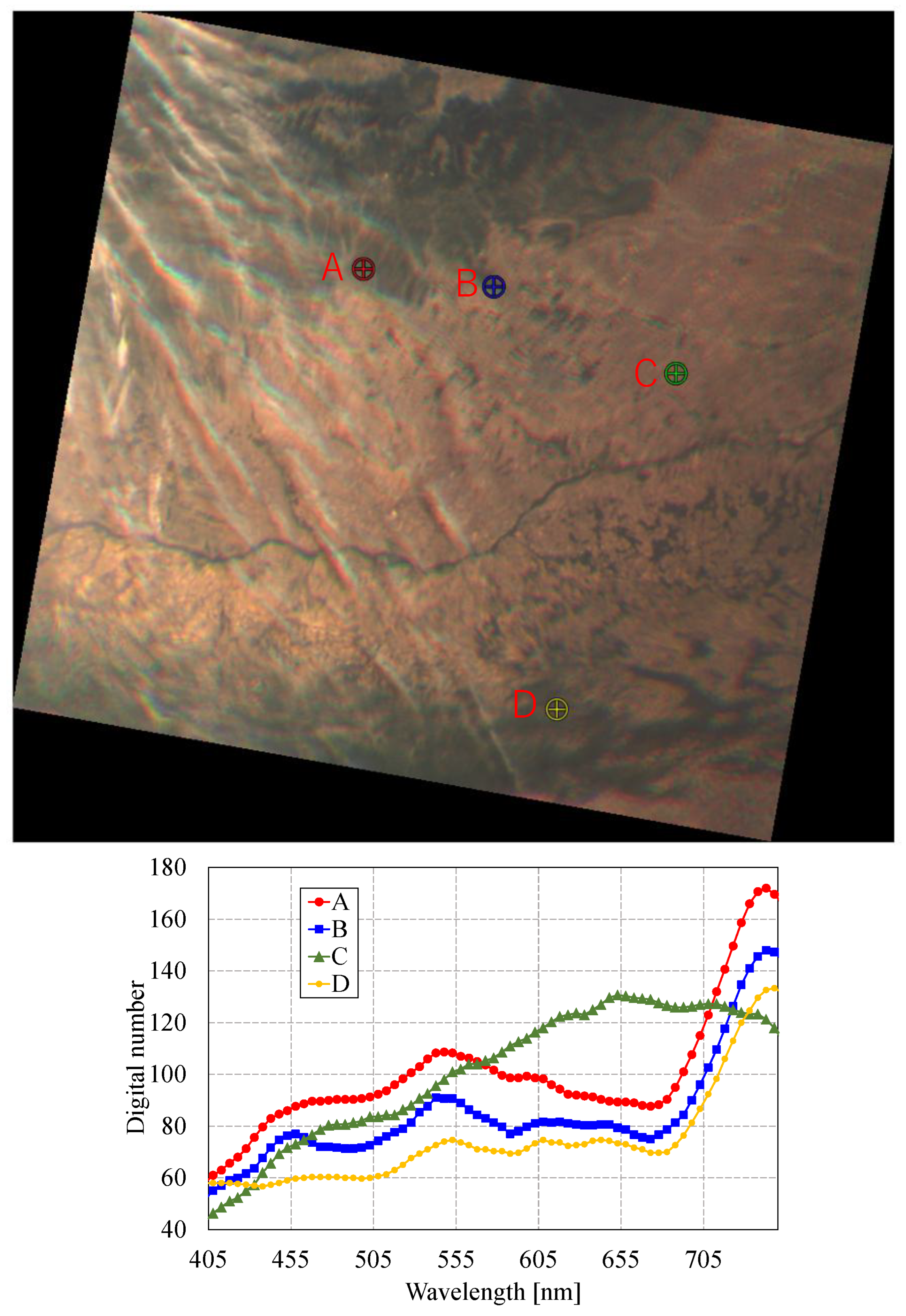

Figure 16.

Composite image (467 nm, 547 nm, and 637 nm) and corresponding spectral data at locations A, B, C, and D (2024-09-09 08:04:59 UTC, from Romania to Bulgaria).

Figure 16.

Composite image (467 nm, 547 nm, and 637 nm) and corresponding spectral data at locations A, B, C, and D (2024-09-09 08:04:59 UTC, from Romania to Bulgaria).

Figure 17.

Composite image (467 nm, 547 nm, and 742 nm) and corresponding spectral data at locations A, B, C, and D (2025-01-08 17:30:12 UTC, near Nevada, USA).

Figure 17.

Composite image (467 nm, 547 nm, and 742 nm) and corresponding spectral data at locations A, B, C, and D (2025-01-08 17:30:12 UTC, near Nevada, USA).

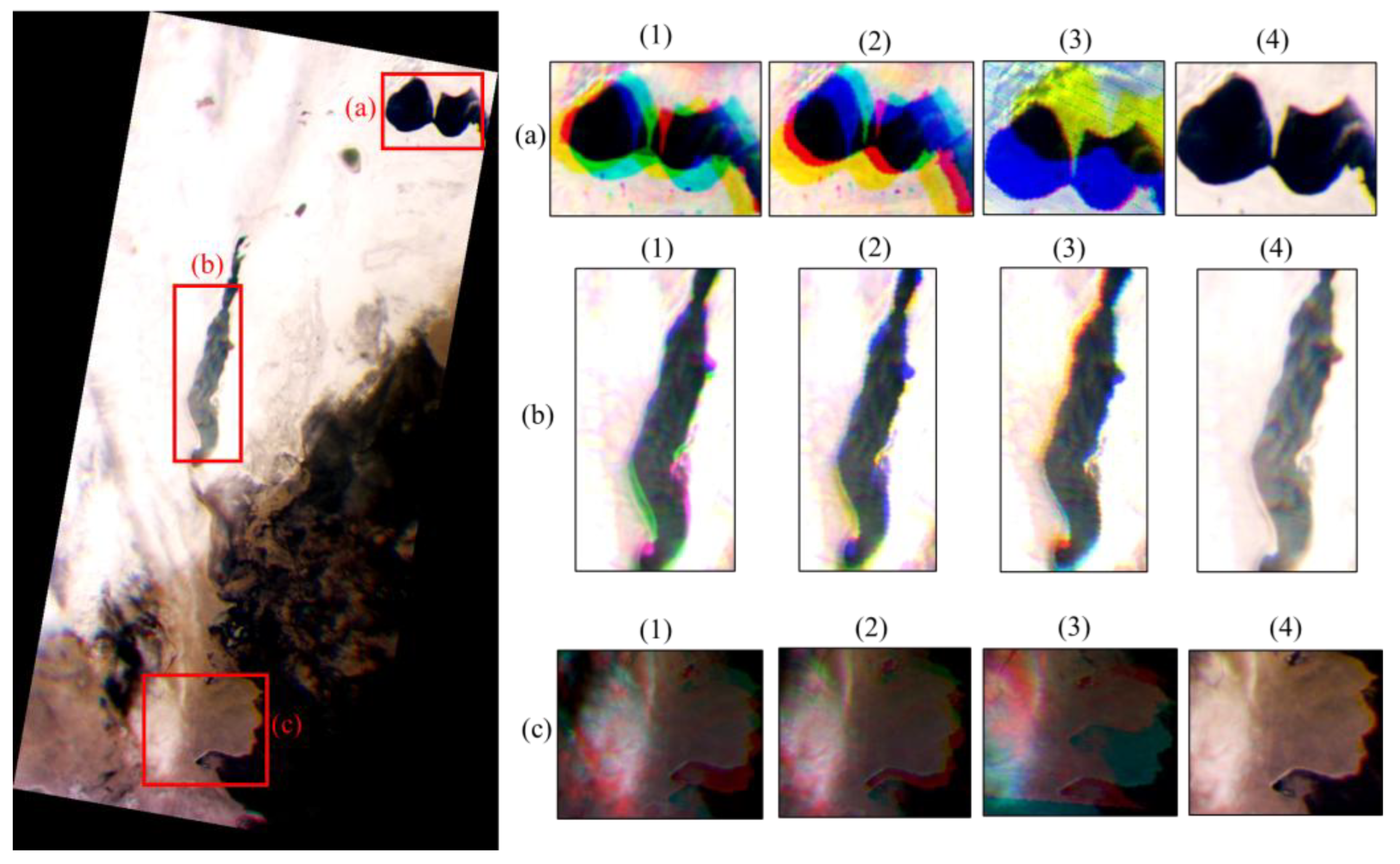

Figure 18.

Positional shifts from data construction methods: (1) Sequential synthesis; (2) Affine; (3) Homography; (4) Proposed method. Composite image at 467 nm, 547 nm, and 637 nm (2024-12-16 05:55:12 UTC, Kazakhstan).

Figure 18.

Positional shifts from data construction methods: (1) Sequential synthesis; (2) Affine; (3) Homography; (4) Proposed method. Composite image at 467 nm, 547 nm, and 637 nm (2024-12-16 05:55:12 UTC, Kazakhstan).

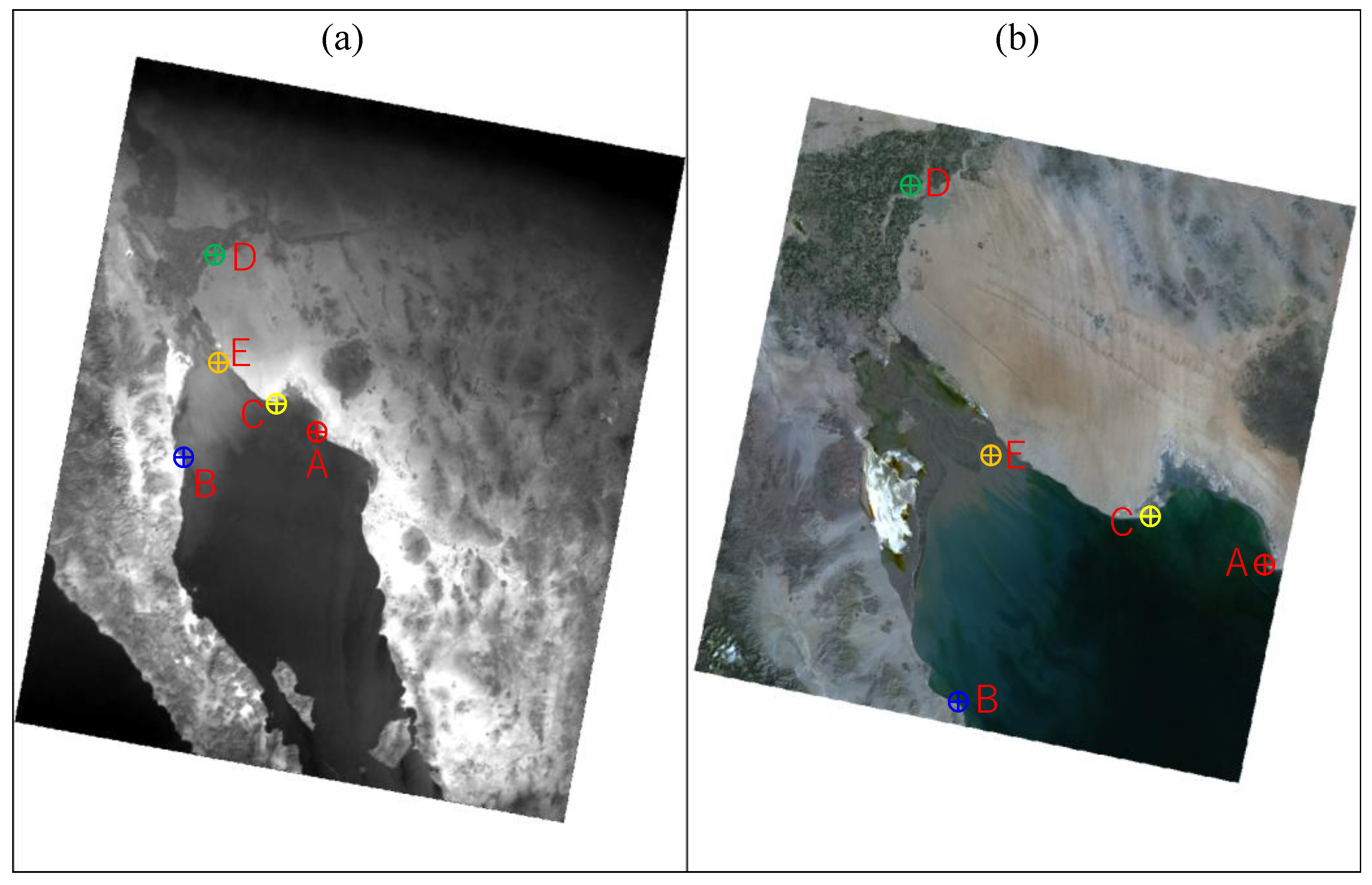

Figure 19.

Geometric correction comparison: (a) RAW image by TIRSAT/hyperspectral camera (2025-01-14 17:16:47 UTC); (b) image by Landsat-9 OLI-2 (2025-03-30 18:10:25 UTC).

Figure 19.

Geometric correction comparison: (a) RAW image by TIRSAT/hyperspectral camera (2025-01-14 17:16:47 UTC); (b) image by Landsat-9 OLI-2 (2025-03-30 18:10:25 UTC).

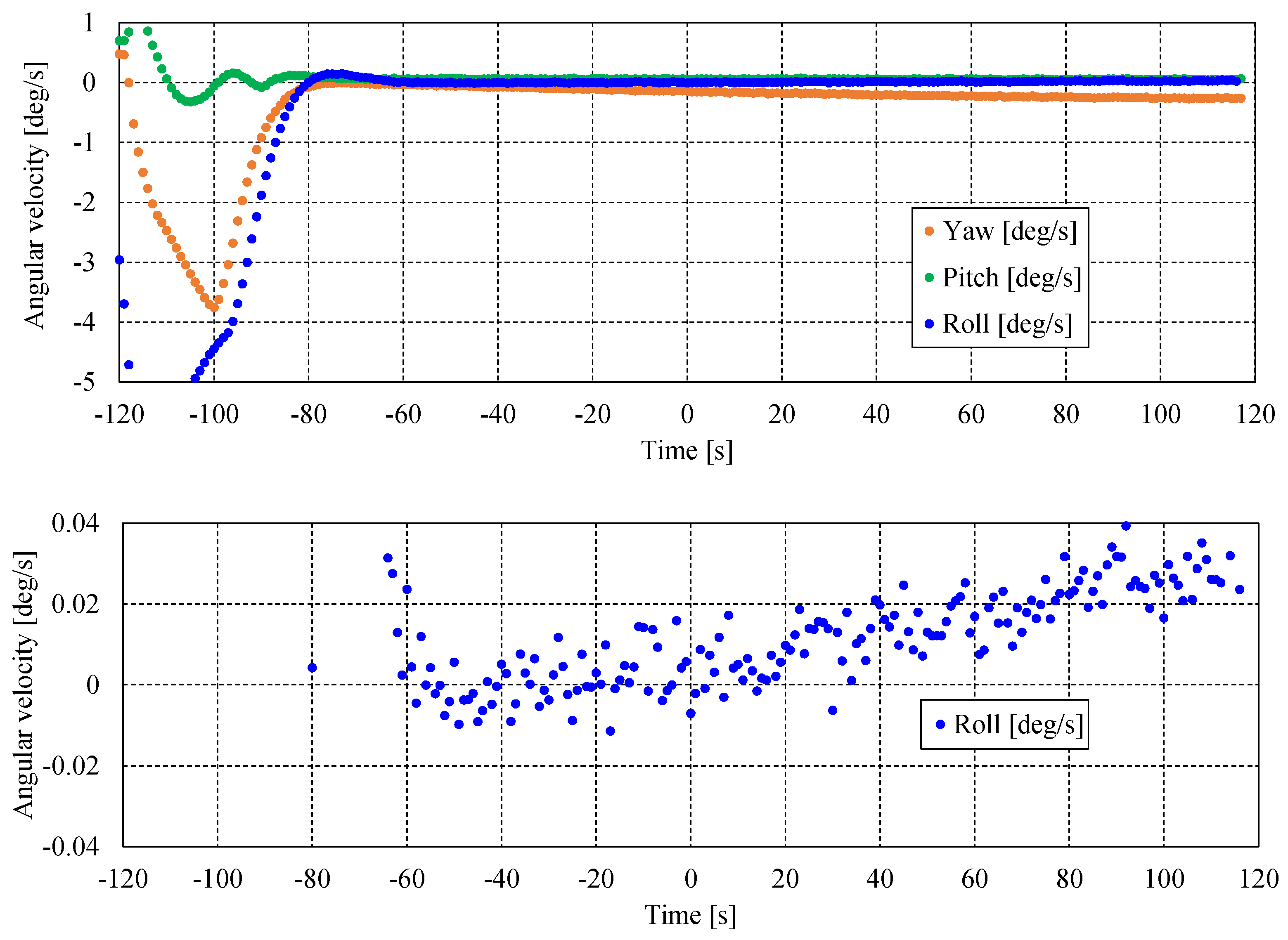

Figure 20.

Angular velocity history during TIRSAT imaging (2025-01-14 17:16:47 UTC). Upper panel: overall results; lower panel: roll-axis close-up.

Figure 20.

Angular velocity history during TIRSAT imaging (2025-01-14 17:16:47 UTC). Upper panel: overall results; lower panel: roll-axis close-up.

Figure 21.

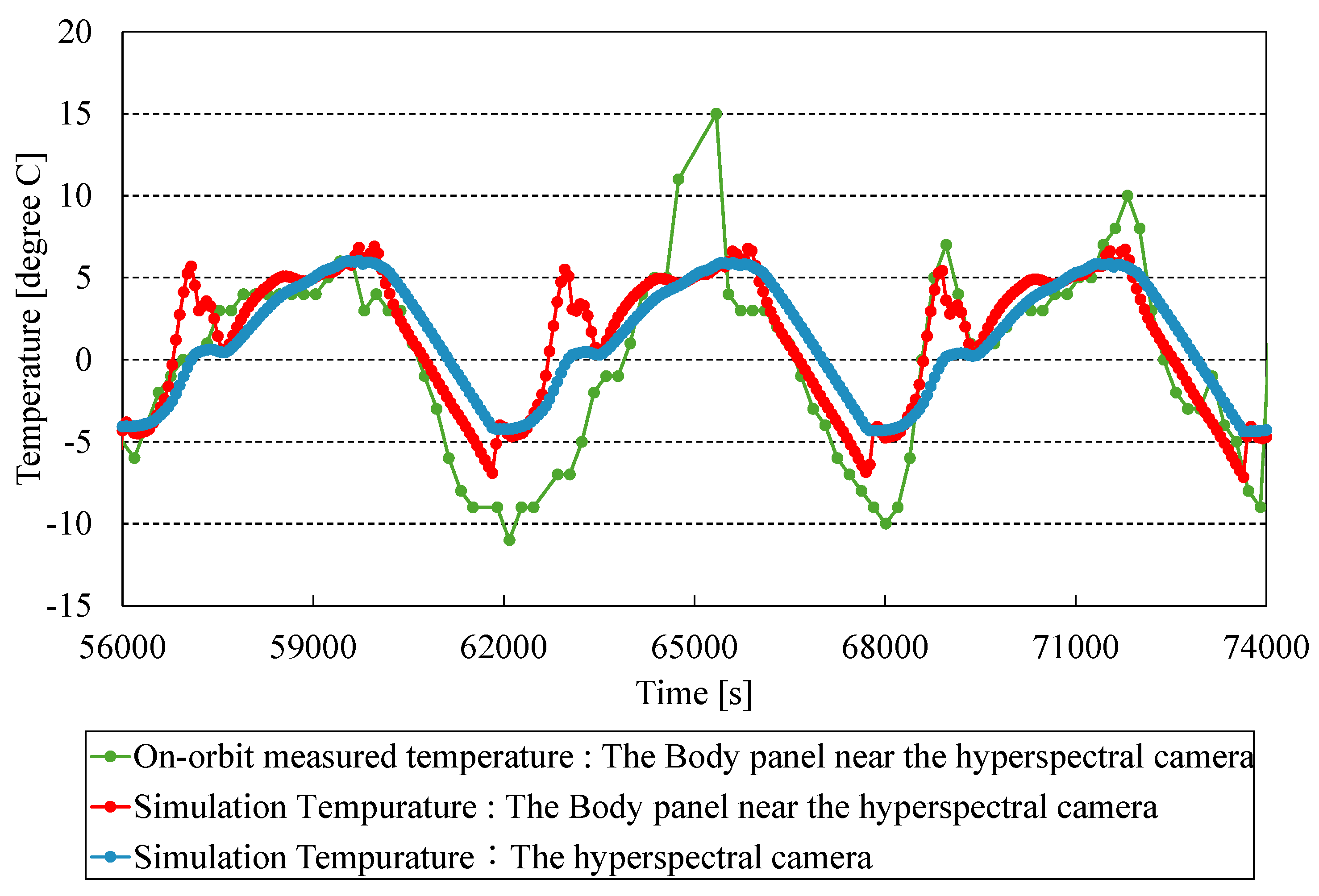

Comparison of simulated and on-orbit measured temperatures.

Figure 21.

Comparison of simulated and on-orbit measured temperatures.

Figure 22.

Power generation after deployment of solar panels.

Figure 22.

Power generation after deployment of solar panels.

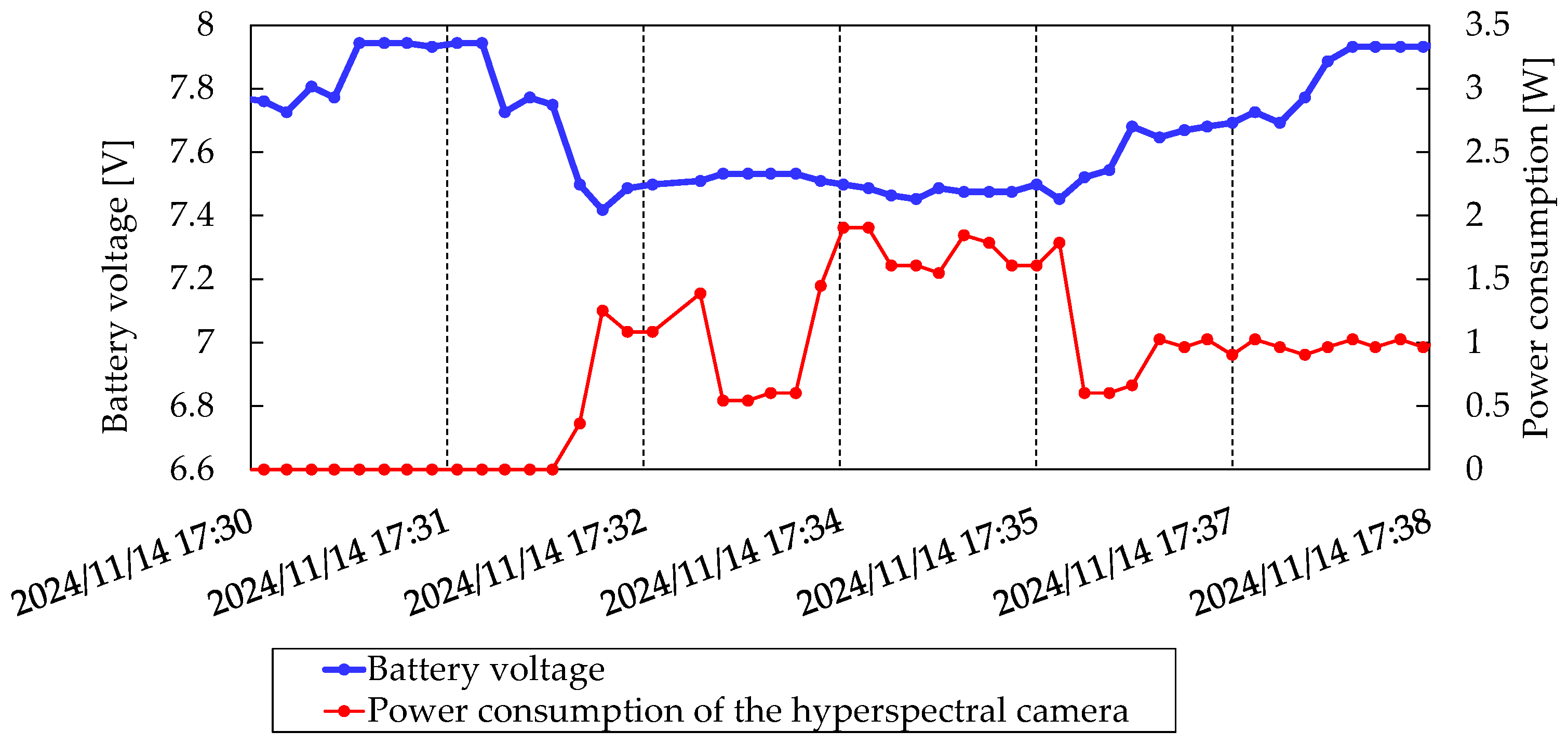

Figure 23.

Power generation after deployment of solar panels.

Figure 23.

Power generation after deployment of solar panels.

Figure 24.

Power generation after deployment of solar panels.

Figure 24.

Power generation after deployment of solar panels.

Figure 25.

Comparison of hyperspectral data from two dates: (a) 2024-11-14 17:34:12 UTC; (b) 2025-01-14 17:16:12 UTC.

Figure 25.

Comparison of hyperspectral data from two dates: (a) 2024-11-14 17:34:12 UTC; (b) 2025-01-14 17:16:12 UTC.

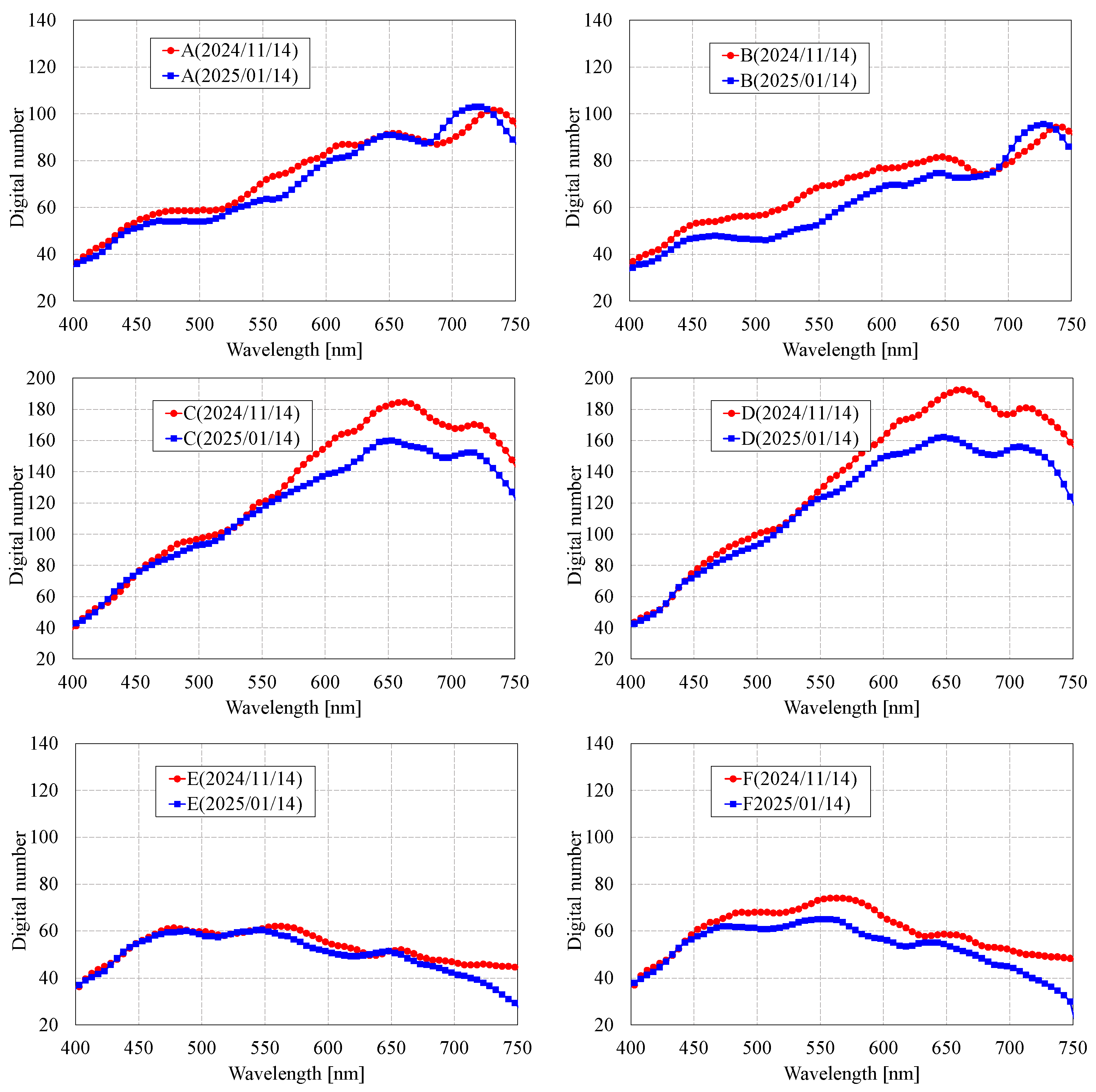

Figure 26.

Spectral data comparison across time at each location: A, B (vegetation in mountainous region); C, D (intermountain region); E, F (coastal region).

Figure 26.

Spectral data comparison across time at each location: A, B (vegetation in mountainous region); C, D (intermountain region); E, F (coastal region).

Figure 27.

Comparison of GNDVI from two time periods.

Figure 27.

Comparison of GNDVI from two time periods.

Table 1.

Specifications of the developed hyperspectral camera.

Table 1.

Specifications of the developed hyperspectral camera.

| Item |

Specification |

| Size |

3.6 cm x 3.6 cm x 2.4 cm |

| Weight |

35 g |

| Ground sampling distance |

450 m/pixel |

| Swath |

460 km |

| Available wavelength range |

400 nm – 770 nm |

| Spectral sampling distance |

5 nm |

| Spectral resolution |

18.5 nm |

| Number of Band |

75 band |

| Focal length of telescope lens |

8 mm |

| F-number of telescope lens |

F/2.5 |

| Valid pixel area |

1280 x 1024 pixels |

| Pixel size |

5.3 μm |

| Dynamic range |

8 bit |

Table 2.

Specifications of the LVBPF.

Table 2.

Specifications of the LVBPF.

| Item |

Specification |

| Size |

10.1 mm x 8 mm |

| Thickness |

0.5 mm |

| Valid wavelength range |

380–850 nm |

| Dispersion |

67.7 nm/mm |

| Peak transmission |

65% |

| Spectral blocking property |

< 1% |

| Half bandwidth |

15 nm at 430 nm20.6 nm at 780 nm |

Table 3.

Specifications of the TIRSAT satellite bus.

Table 3.

Specifications of the TIRSAT satellite bus.

| Item |

Specification |

| Size |

117 mm x 117 mm x 381 mm |

| Weight |

4.97 kg |

| Attitude Determination and Control Subsystem |

3-axis stabilization control using geomagnetic sensor, MEMS gyroscope, 3-sun sensor, GPS receiver, magnetic torque, and reaction wheel |

| Electrical Power Subsystem |

Solar array panel: 4 deployable panels, 4 body-mounted panels

Maximum power generation: 20 W

Typical power consumption: 10 W

Battery: 5.8 Ah, Nominal 8 V (Lithium-ion battery) |

| Communication Subsystem |

Telemetry/Command: S-band

Command Uplink: 4 kbps,

Telemetry Downlink: 4 kbps – 64 kbps

Mission data downlink: X-band (5 Mbps, 10 Mbps) |

| Orbit |

Sun-synchronous sub-recurrent orbit

Altitude: 680 km (approximately), Inclination: 98 degrees |

Table 4.

Specifications of the ADCS onboard TIRSAT.

Table 4.

Specifications of the ADCS onboard TIRSAT.

| Item |

Specification |

| Reaction wheel |

3-axis mounted

Max angular momentum: 3mNms (nominal)

5mNms(peak) |

| Magnetic torquer |

3-axis mounted

Magnetic moment: 0.35Am2

|

| Sun sensor |

3-surface mounted

accuracy <= 0.5°(3σ) |

| Fine Geomagnetic sensor |

Resolution: 13nT |

| Fine Gyroscope |

Random noise: 4.36E-05 rad/s(1σ) |

| Microcontroller |

Clock: 80MHz, ROM: 512 kiB, RAM: 128KiB |

Table 5.

Required attitude control accuracy and stability for the ADCS.

Table 5.

Required attitude control accuracy and stability for the ADCS.

| Item |

Attitude control accuracy

(roll, pitch) |

Attitude control accuracy

(yaw) |

Attitude stability

(roll) |

| requirements |

7.3° |

5.8° |

0.048°/s |

Table 6.

Parameters for each hyperspectral data construction method.

Table 6.

Parameters for each hyperspectral data construction method.

| Item |

(1)

Sequentially synthesize |

(2)

Affine |

(3)

Homography |

(4)

Proposed method |

| Image Enhancement |

- |

Gamma correction (gamma=2.0) |

| Unsharp masking |

Feature

detection |

AKAZE |

| Transformation |

Affine |

Homography and RANSAC |

(1) + (2) |

| Library |

OpenCV, pillow |

Table 7.

Geo-referenced coordinates of satellite images and geometric correction error distances.

Table 7.

Geo-referenced coordinates of satellite images and geometric correction error distances.

| Location |

TIRSAT |

Landsat-9 |

Distance [km] |

| Latitude [°] |

Longitude [°] |

Latitude [°] |

Longitude [°] |

| A |

31.7117 |

-113.8237 |

31.3447 |

-113.6420 |

44.297 |

| B |

30.9371 |

-114.7187 |

31.4722 |

-114.9723 |

64.209 |

| C |

31.4933 |

-114.0276 |

31.9123 |

-114.1741 |

48.612 |

| D |

33.0178 |

-114.7806 |

32.4926 |

-114.8430 |

58.692 |

| E |

32.1983 |

-114.7021 |

31.6918 |

-114.5939 |

57.241 |