Submitted:

23 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Binders

2.1.2. M-Sand and R-Sand

2.1.3. Coarse Aggregate

2.1.4. Admixture

2.2. Experimental Methodologies

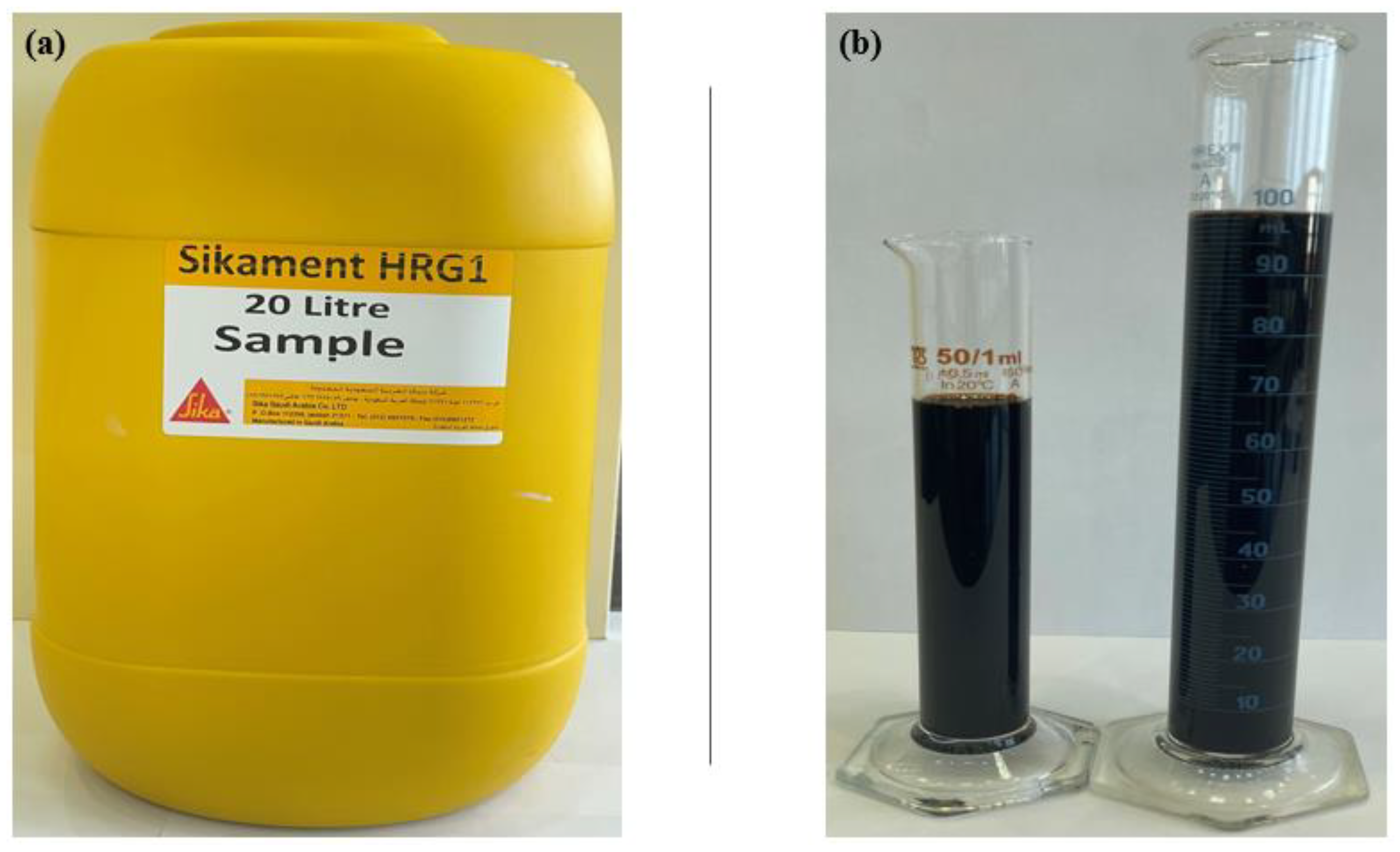

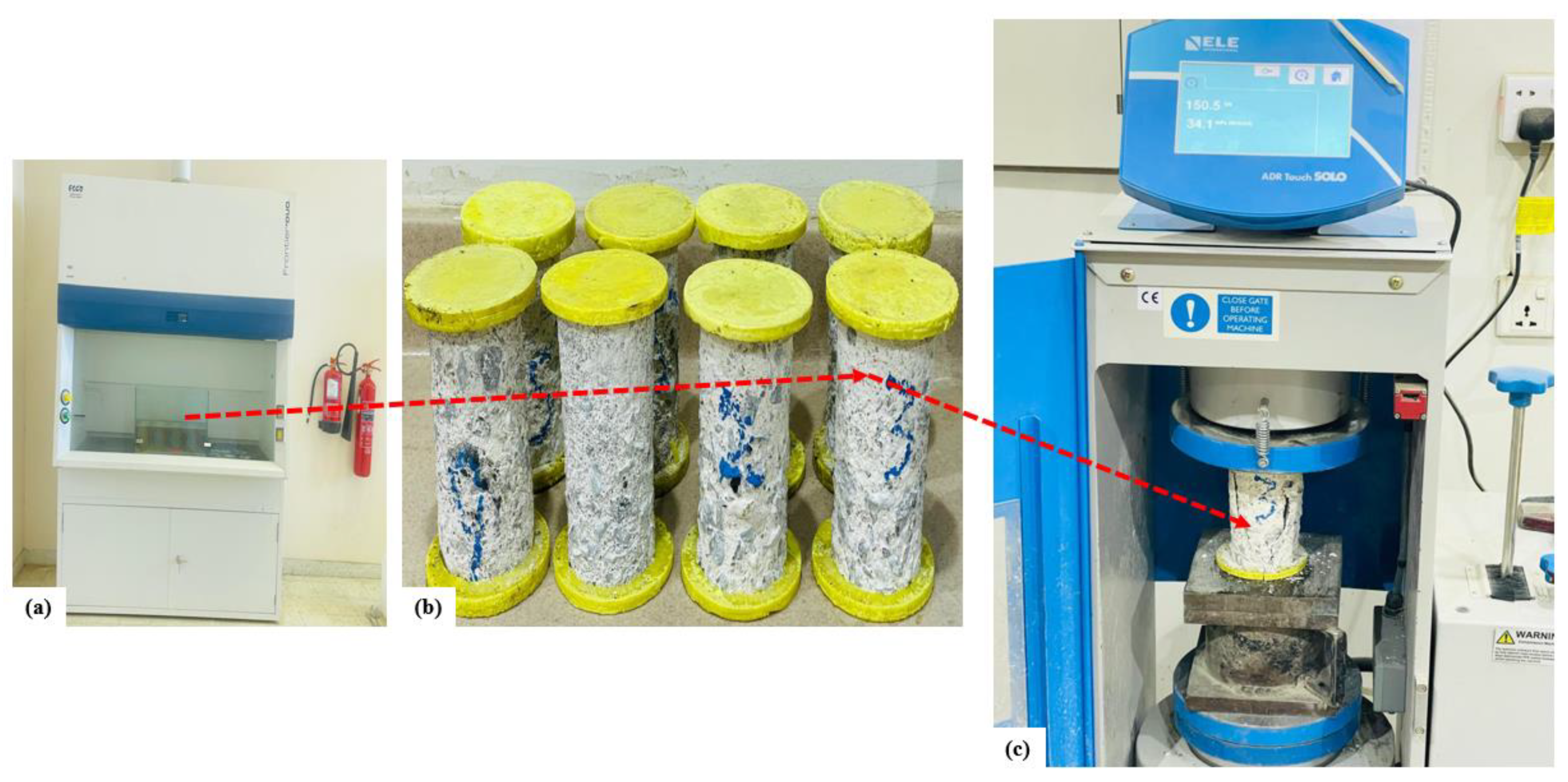

2.2.1. Developed Methodology for Recycled Sand Preparation

2.2.2. Properties of Concrete Ingredient

2.2.3. Optimization of Materials and Design Mixes

2.2.3.1. Silica Fume Optimization

2.2.3.2. Sand Optimization

2.2.3.3. Design Mix

2.2.3.4. Ingradient of Design Mixes

3. Discussion on the Results of the Study

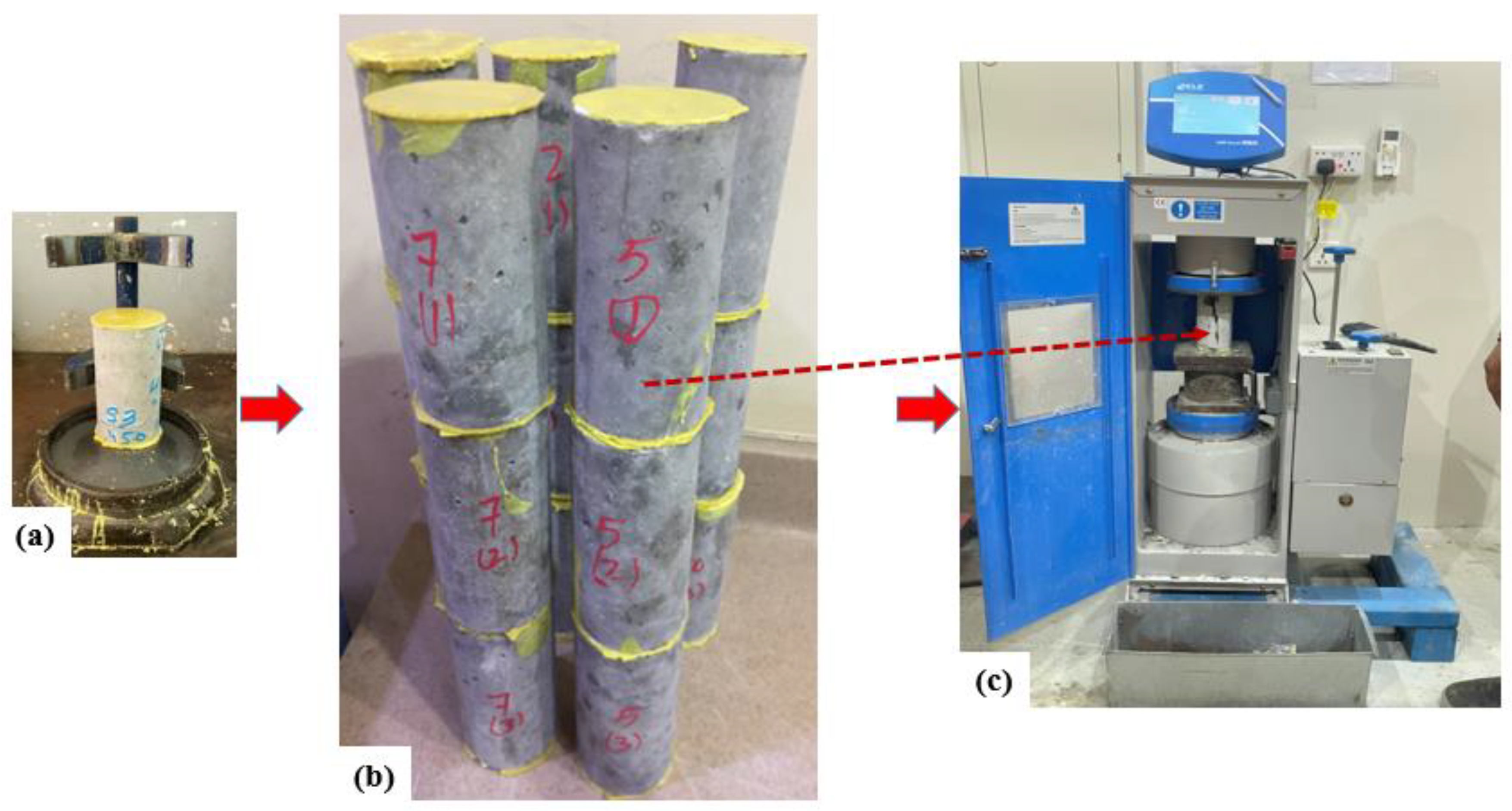

3.1. Strength Properties

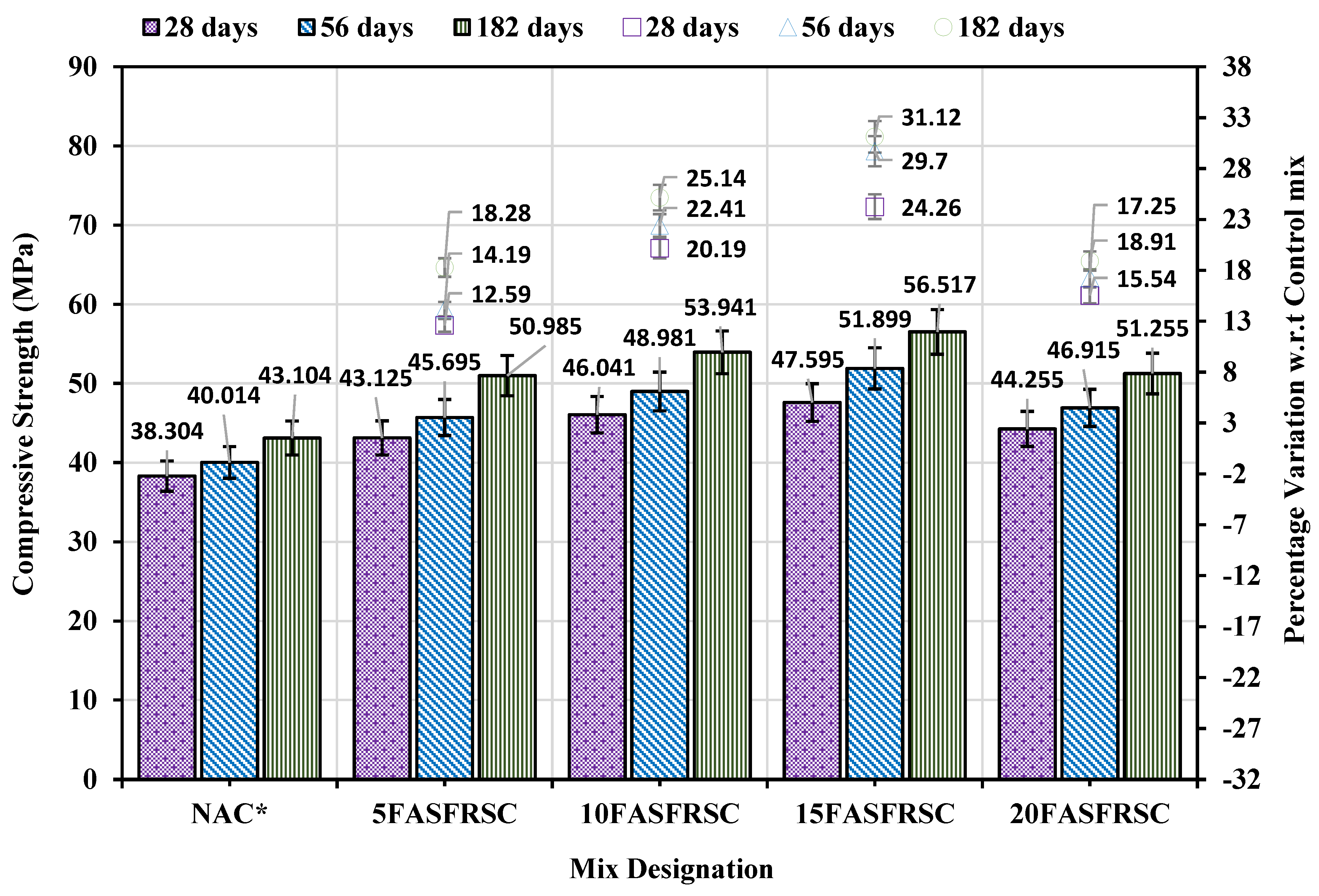

3.1.1. Analysis of Compressive Strength Results

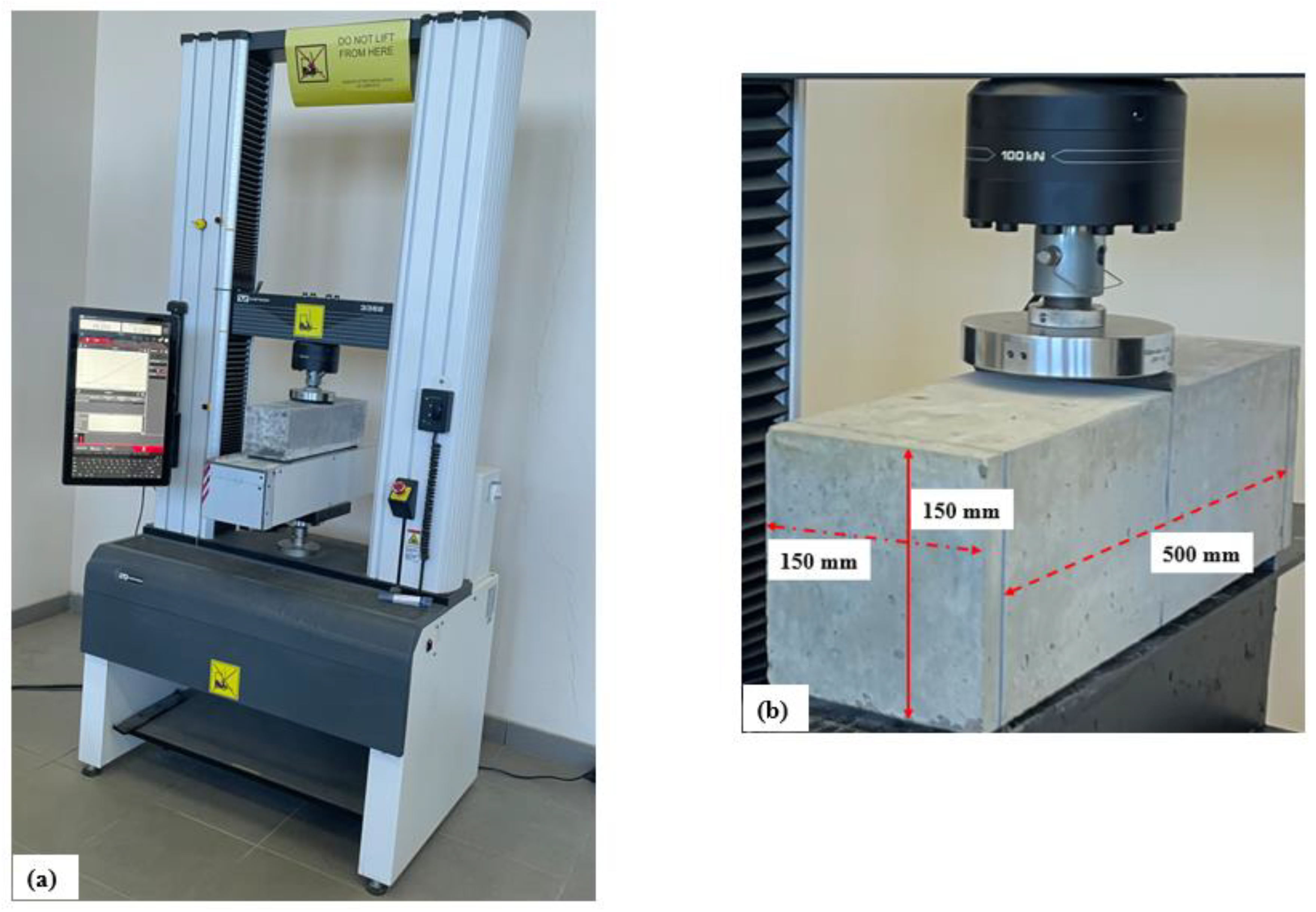

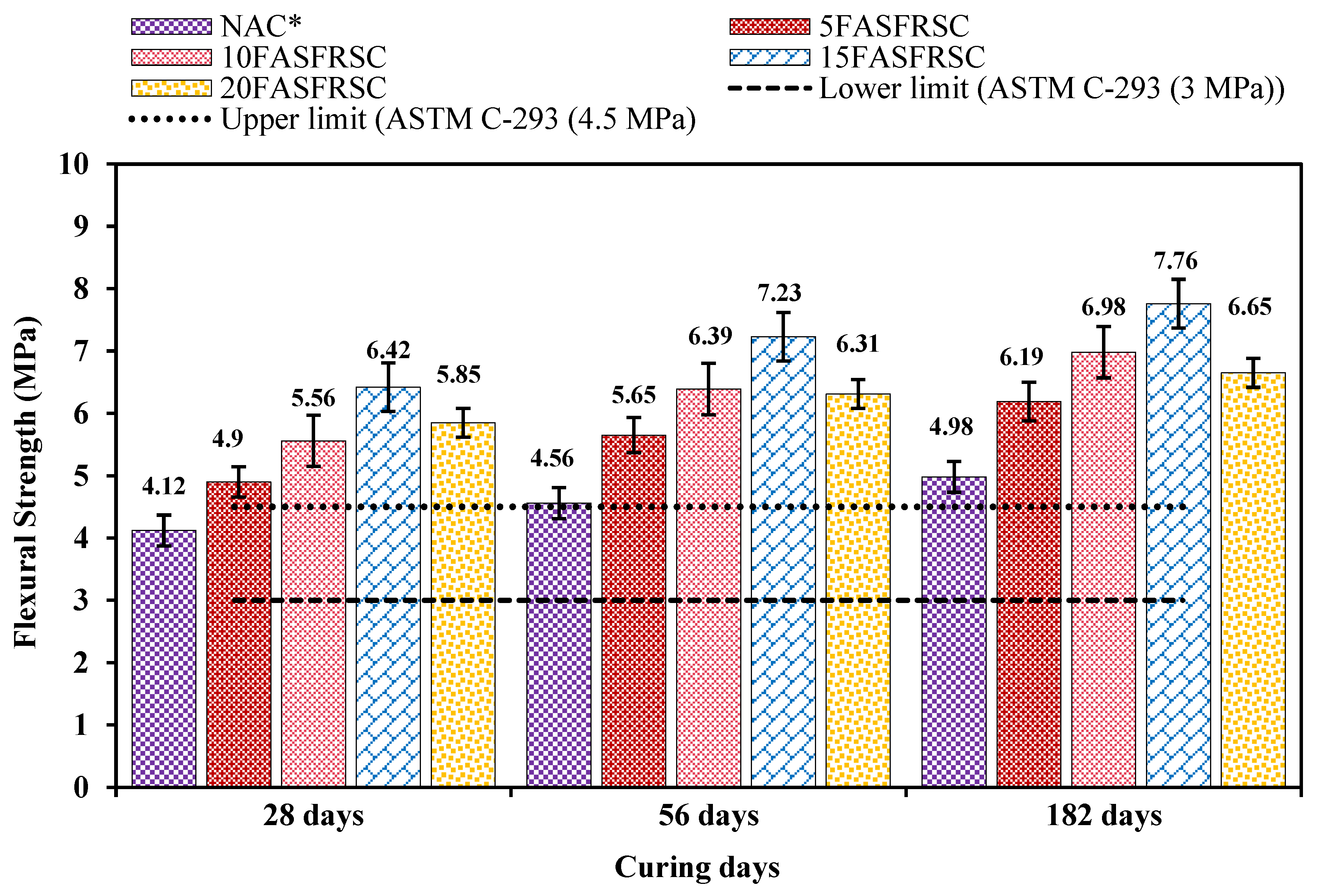

3.1.2. Flexural Strength Evaluation

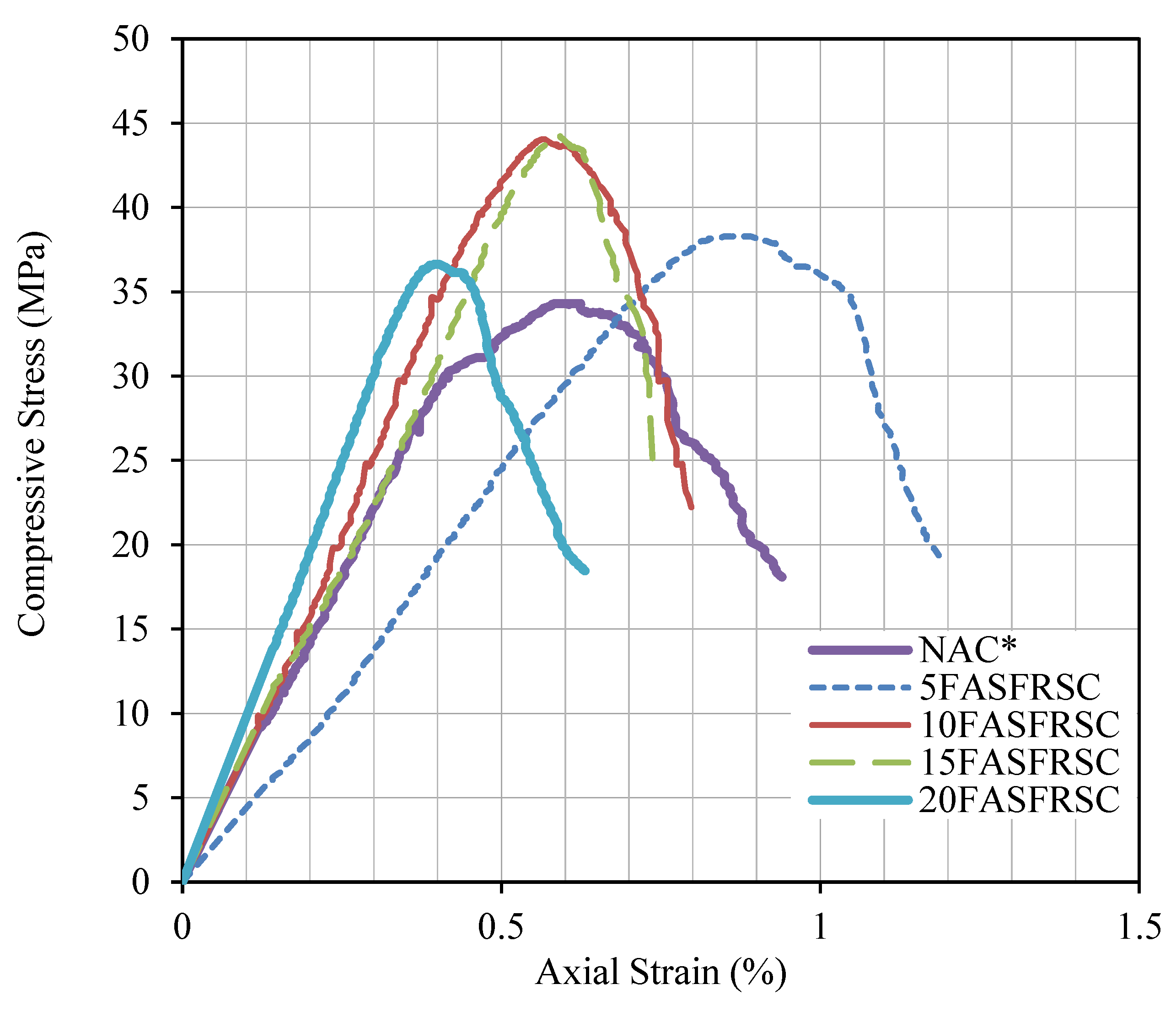

3.1.3. Stress-Strain Characteristics Under Compression

3.2. Characteristics of Durability Properties

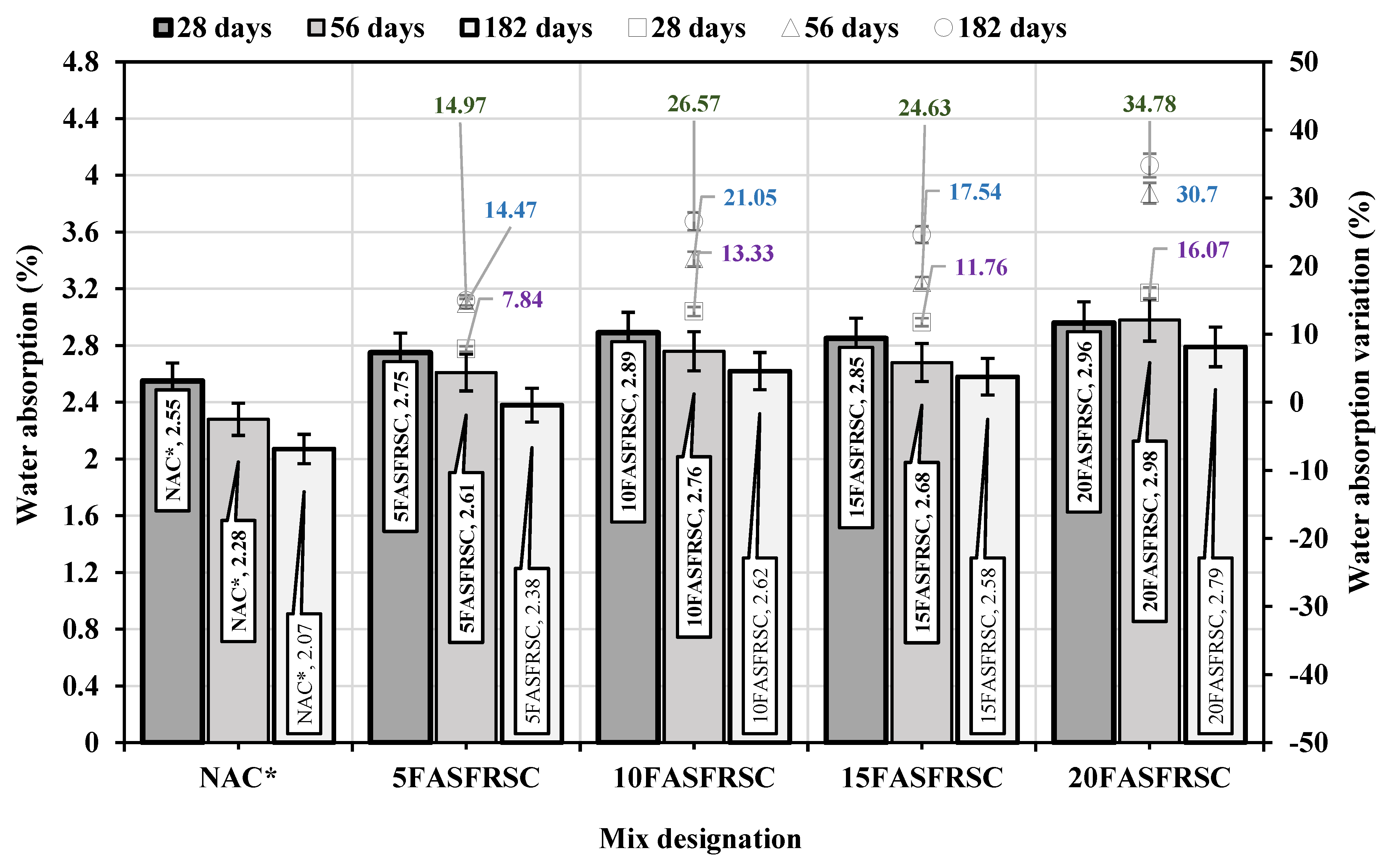

3.2.1. Absorption of Water in Hardened Concrete

3.2.2. Sulphuric Acid Attack

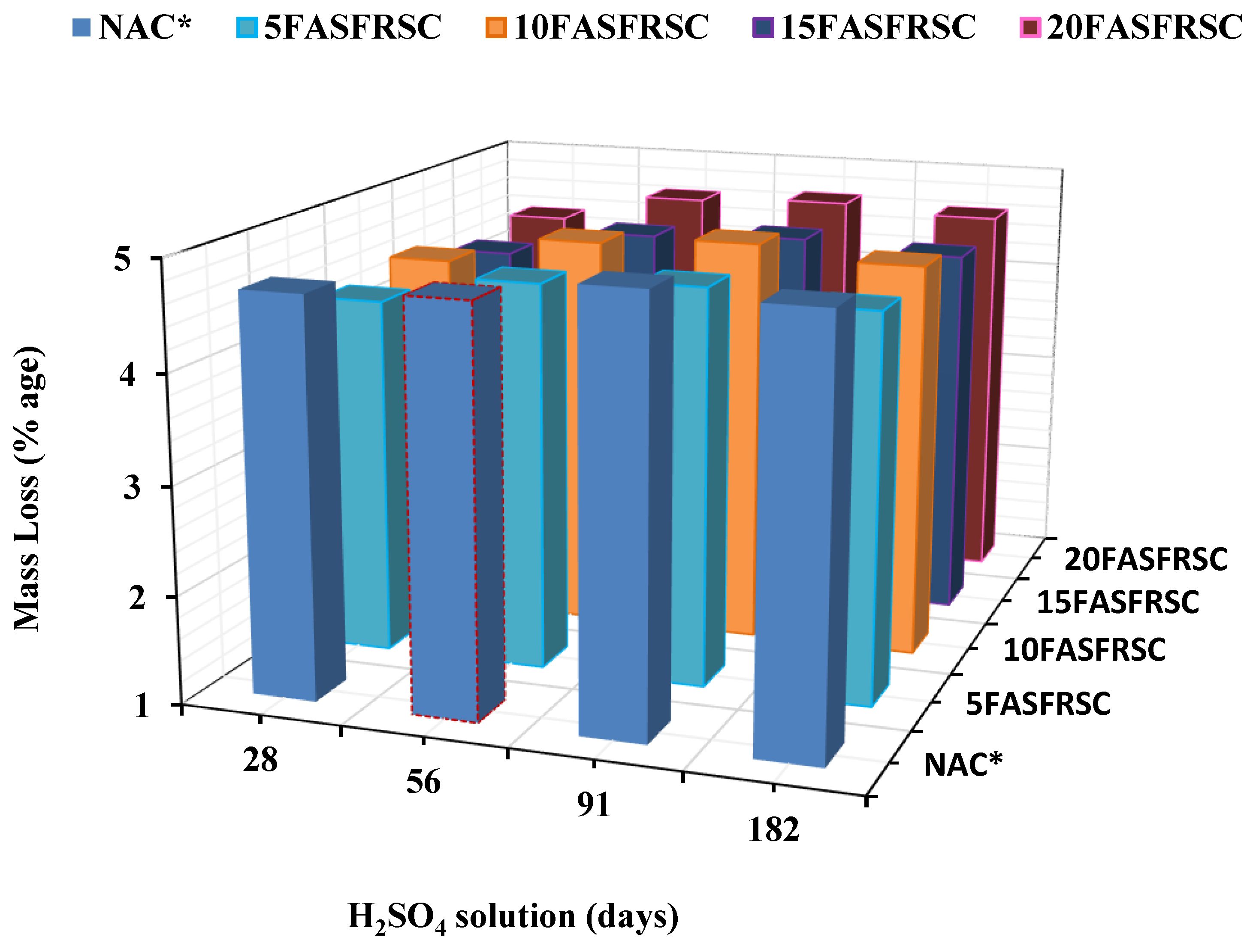

3.2.2.1. Change of Mass of Concrete Samples in Sulphuric Acid Solution

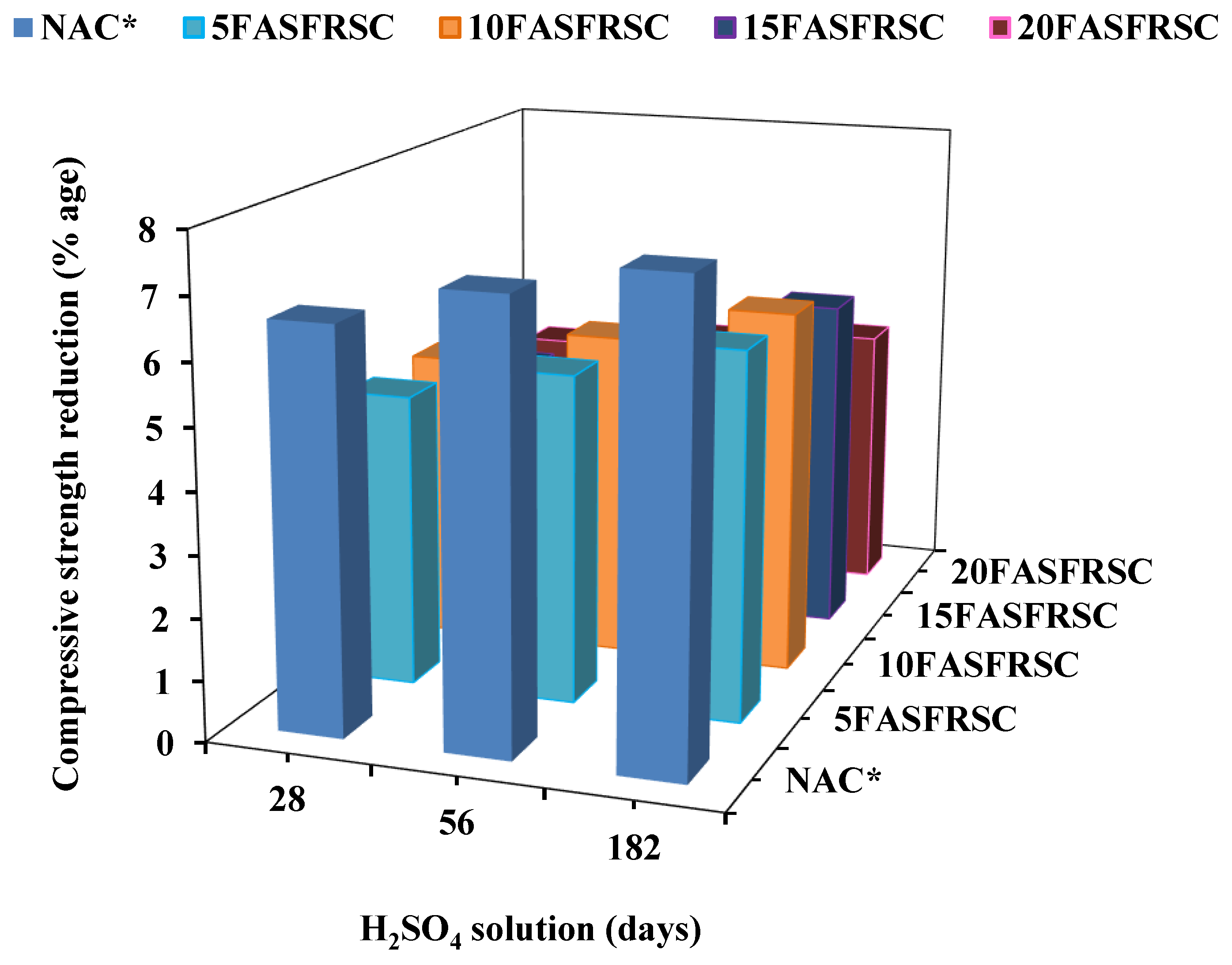

3.3.2.2. Variation in the Compressive Strength of Concrete Exposed to a Sulfuric Acid Solution

4. Conclusions

- Concrete from fly ash, silica fume, and recycled sand exhibited better mechanical properties and maintained adequate durability.

- The four sustainable concrete formulations, including fly ash, silica fume, and recycled sand, successfully met the 30 MPa and 38 MPa compressive strength requirements, as ACI 318-19 outlined.

- 3. At the intervals of 28, 56, and 182 days, the compressive strength of the developed mixes 5FASFRSC, 10FASFRSC, 15FASFRSC, and 20FASFRSC consistently outperformed the reference mix NAC*.

- At 28 days, the flexural strength of the 5FASFRSC, 10FASFRSC, 15FASFRSC, and 20FASFRSC formulations was found to be 16.3%, 18.5%, 21.4%, and 19.5% of the concrete’s design strength (f’c), respectively. These values comply with the ASTM-C496/C496M-11 standard, which requires them to be between 10% and 15% of the (f’c).

- The absorption of water at 28, 56, and 182 days in the mixes 5FASFRSC, 10FASFRSC, 15FASFRSC, and 20FASFRSC with the combination of SCMs (FS+SF) along with modified sand combination (50%R-Sand+50%M-Sand) found decreasing pattern. The threshold was reached in the mix 15FASFRSC with the combination of (15%FA+10%SF) and a modified sand combination (50%R-Sand+50%M-Sand).

- The developed mixes 5FASFRSC, 10FASFRSC, 15FASFRSC, and 20FASFRSC show better resistance against sulphuric acid attacks than the reference mix NAC*. The mixture labeled 15FASFRSC yielded consistent results when the fine aggregate was optimally balanced with a 50/50 combination of R-Sand and M-Sand and supplemented with cementitious materials comprising 15% FA and 10% SF.

- It is concluded that up to 25% OPC with optimized SCMs (15%FA+10%SF) and 100% river sand with (50%R-Sand+50%M-Sand) could be replaced in the formulation of concrete mixtures for the building sector.

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| Flyash | FA |

| Silica Fume | SF |

| R-Sand | Recycled Sand |

| M-Sand | Manufactured Sand |

| Supplementary Cementitious Materials | SCMs |

| Natural Coarse Aggregate | NCA |

| Ordinary Portland Cement | OPC |

| Compressive strength | CS |

| Flexural Strength | FS |

References

- H. Song, G. Gu, and Y. Cheng, „Experimental Study on River Sand Replacement in Concrete,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2020, vol. 567, no. 1: IOP Publishing, p. 012013.

- M. Bendixen, J. Best, C. Hackney, and L. L. Iversen, „Time is running out for sand,” ed: Nature Publishing Group, 2019.

- P. V. Sáez, M. Merino, and C. Porras-Amores, „Managing construction and demolition (C&D) waste–a European perspective,” in International Conference on Petroleum and Sustainable Development, 2011, vol. 26, pp. 27-31.

- C. Fischer, M. Werge, and A. Reichel, „EU as a Recycling Society,” European Topic Centre on Resource Waste Management, Working Paper 2/2009, 2009.

- V. Monier, S. Mudgal, M. Hestin, M. Trarieux, and S. Mimid, „Service contract on management of construction and Demolition Waste–SR1,” Final Report Task, vol. 2, p. 240, 2011.

- Mistri, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.K.; Dhami, N.; Mukherjee, A.; Barai, S.V. A review on different treatment methods for enhancing the properties of recycled aggregates for sustainable construction materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Akhtar and M. Akhtar, „Enhancement in properties of concrete with demolished waste aggregate,” GE-International Journal of Engineering Research, vol. 2, no. 9, pp. 73-83, 2014.

- M. Monish, V. M. Monish, V. Srivastava, V. Agarwal, P. Mehta, and R. Kumar, „Demolished waste as coarse aggregate in concrete,” J. Acad. Indus. Res, vol. 1, no. 9, pp. 540-542, 2013.

- Tripura, D.D.; Raj, S.; Mohammad, S.; Das, R. Suitability of Recycled Aggregate as a Replacement for Natural Aggregate in Construction. SP-326: Durability and Sustainability of Concrete Structures (DSCS-2018). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 37.1–37.10.

- Feng, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Tang, Y.; Wu, D.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Prediction of thermo-mechanical properties of rubber-modified recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunchao, T.; Zheng, C.; Wanhui, F.; Yumei, N.; Cong, L.; Jieming, C. Combined effects of nano-silica and silica fume on the mechanical behavior of recycled aggregate concrete. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2021, 10, 819–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, C.; Ma, L.; Li, L. Partially fly ash and nano-silica incorporated recycled coarse aggregate based concrete: Constitutive model and enhancement mechanism. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.; Jeong, J.-G.; Palou, M.; Park, K. Mechanical Behavior of Fine Recycled Concrete Aggregate Concrete with the Mineral Admixtures. Materials 2020, 13, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. N. Akhtar, Z. Ibrahim, N. M. Bunnori, M. Jameel, N. Tarannum, and J. Akhtar, „Performance of sustainable sand concrete at ambient and elevated temperature,” ed: Elsevier, 2021.

- K. C. Williams and P. Partheeban, „An experimental and numerical approach in strength prediction of reclaimed rubber concrete,” Advances in concrete construction, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 87, 2018.

- Akhtar, J.N.; Khan, R.A.; Akhtar, M.N.; Thomas, B.S. A comparative study of strength and durability characteristics of concrete and mortar admixture by bacterial calcite precipitation: A review. Mater. Today: Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.N.; Jameel, M.; Ibrahim, Z.; Bunnori, N.M. Incorporation of recycled aggregates and silica fume in concrete: an environmental savior-a systematic review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 4525–4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajiri, A.M.; Akhtar, M.N. Enhancing Sustainability and Economics of Concrete Production through Silica Fume: A Systematic Review. Civ. Eng. J. 2023, 9, 2612–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Kar, D.; Ashish, K. Silica fume and waste glass in cement concrete production: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 100888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashish, D.K.; Verma, S.K. An overview on mixture design of self-compacting concrete. Struct. Concr. 2018, 20, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI-318, „Building code requirements for structural concrete (ACI 318-08) and commentary,” 2008: American Concrete Institute.

- High-Range, G Water-Reducing and Retarding Admixture, ASTM-C-494/C-494M, 2005.

- Klee, H.; Coles, E. The cement sustainability initiative – implementing change across a global industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2004, 11, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho and, J. de Brito, „Economic analysis of conventional versus selective demolition—A case study,” Resources, Conservation and Recycling, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 382-392, 2011.

- Ulsen, C.; Tseng, E.; Angulo, S.C.; Landmann, M.; Contessotto, R.; Balbo, J.T.; Kahn, H. Concrete aggregates properties crushed by jaw and impact secondary crushing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, A.T.; Di Maio, F.; Vahidi, A.; Rem, P. Innovative technologies for recycling End-of-Life concrete waste in the built environment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard Test Method for Density, Relative Density (specific gravity), and Absorption of Fine Aggregates,” ed,, ASTM-C128-88, 2001.

- Aldossary, M.H.A.; Ahmad, S.; Bahraq, A.A. Effect of total dissolved solids-contaminated water on the properties of concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Miao, B.; Liu, F.-S. Effect of wash water and underground water on properties of concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS-3148, „Method for test for water for making concrete. London: British standard institute.,” 1980.

- ACI-211.1, „Standard practice for selecting proportions for normal, heavyweight, and mass concrete,” in American Concrete Institute, 1991.

- ASTM-C136-06, „Standard Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates,” 2006.

- Standard practice for selecting proportions for normal, heavyweight, and mass concrete, ACI-211.1-91, Nov. 1, 1991 1991.

- Standard Practice for Making and Curing Concrete Test Specimens, ASTM-C31/C31M-19a, 2019.

- Akhtar, M.N.; Bani-Hani, K.A.; Malkawi, D.A.; Albatayneh, O. Suitability of sustainable sand for concrete manufacturing - A complete review of recycled and desert sand substitution. Results Eng. 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Akhtar and J. Akhtar, „Suitability of Class F Flyash for Construction Industry: An Indian Scenario,” International Journal of Structural and Construction Engineering, vol. 12, no. 9, pp. 892-897, 2018.

- Akhtar, M.N.; Jameel, M.; Ibrahim, Z.; Bunnori, N.M.; Bani-Hani, K.A. Development of sustainable modified sand concrete: An experimental study. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI-214R-11, „Guide to evaluation of strength test results of concrete,” 2011: American Concrete Institute.

- C. ASTM, „C293, Standard test method for flexural strength of concrete (using a simple beam with centre-point loading), ASTM Int,” West Conshohocken, 2016.

- Rais, M.S.; Khan, R.A. Strength and durability characteristics of binary blended recycled coarse aggregate concrete containing microsilica and metakaolin. Innov. Infrastruct. Solutions 2020, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Ingredient results | ||||||

| Cement | Flyash | Silica fume | R-Sand | M-Sand | Coarse aggregate | Water for mixing concrete ingrideint | |

| Bulk specific gravity | 3.15 | 2.10 | 2.30 | 2.56 | 2.66 | 2.80 | - |

| Absorption (%) | - | - | - | 2.88 | 1.32 | 0.92 | - |

| Sand equivalent values | - | - | - | 94 | 98 | - | - |

| Fineness modulus (FM) | - | - | - | 2.6 | 3.0 | 7.0 | - |

| pH | - | - | - | 7.8 | 7.2 | 7.1 | |

| Sulfate (ppm) | - | - | - | 950 | 268 | 170 | 28 |

| TDS (ppm) | - | - | - | 680 | |||

| Chloride (ppm) | - | - | - | 1010 | 160 | 94 | 40 |

| Organic impurities | - | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil | - |

| Salinity | 478 | ||||||

| Mix Designation | Cementitious materials % | Fine aggregate % | NCA % |

Admixture by weight of cement (%) | Mix temperature (°C) | Mix Air temperature (°C) | Mix Air content (%) |

||||

| OPC | FA | SF | Total | R-sand | M-sand | ||||||

| NAC* | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0.0 | 27 | 20 | 2.5 |

| 5FASFRSC | 85 | 5 | 10 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 0.8 | 26 | 20 | 2.4 |

| 10FASFRSC | 80 | 10 | 10 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 1.2 | 25 | 20 | 2.5 |

| 15FASFRSC | 75 | 15 | 10 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 1.6 | 25 | 20 | 2.5 |

| 20FASFRSC | 70 | 20 | 10 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 2.0 | 25 | 20 | 2.6 |

| NAC* = Natural aggregate concrete (reference mix*) | |||||||||||

| 5FASFRSC = (5%FA+10%SF+(50%R-Sand+50%M-Sand)) | |||||||||||

| 10FASFRSC = (10%FA+10%SF+(50%R-Sand+50%M-Sand)) | |||||||||||

| 15FASFRSC = (15%FA+10%SF+(50%R-Sand+50%M-Sand)) | |||||||||||

| 20FASFRSC = (20%FA+10%SF+(50%R-Sand+50%M-Sand)) | |||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).