Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

27 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

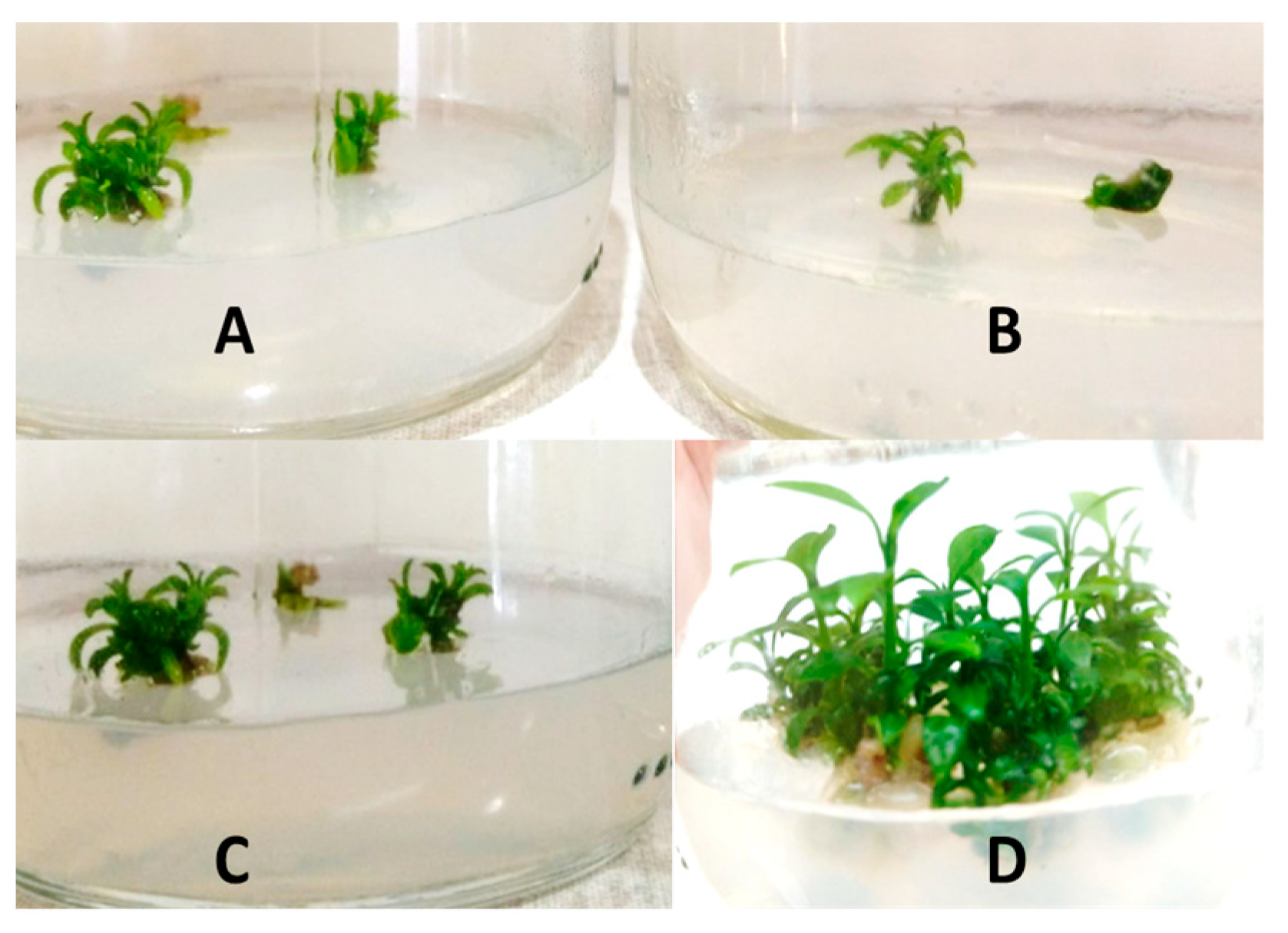

3.1. In Vitro Establishment

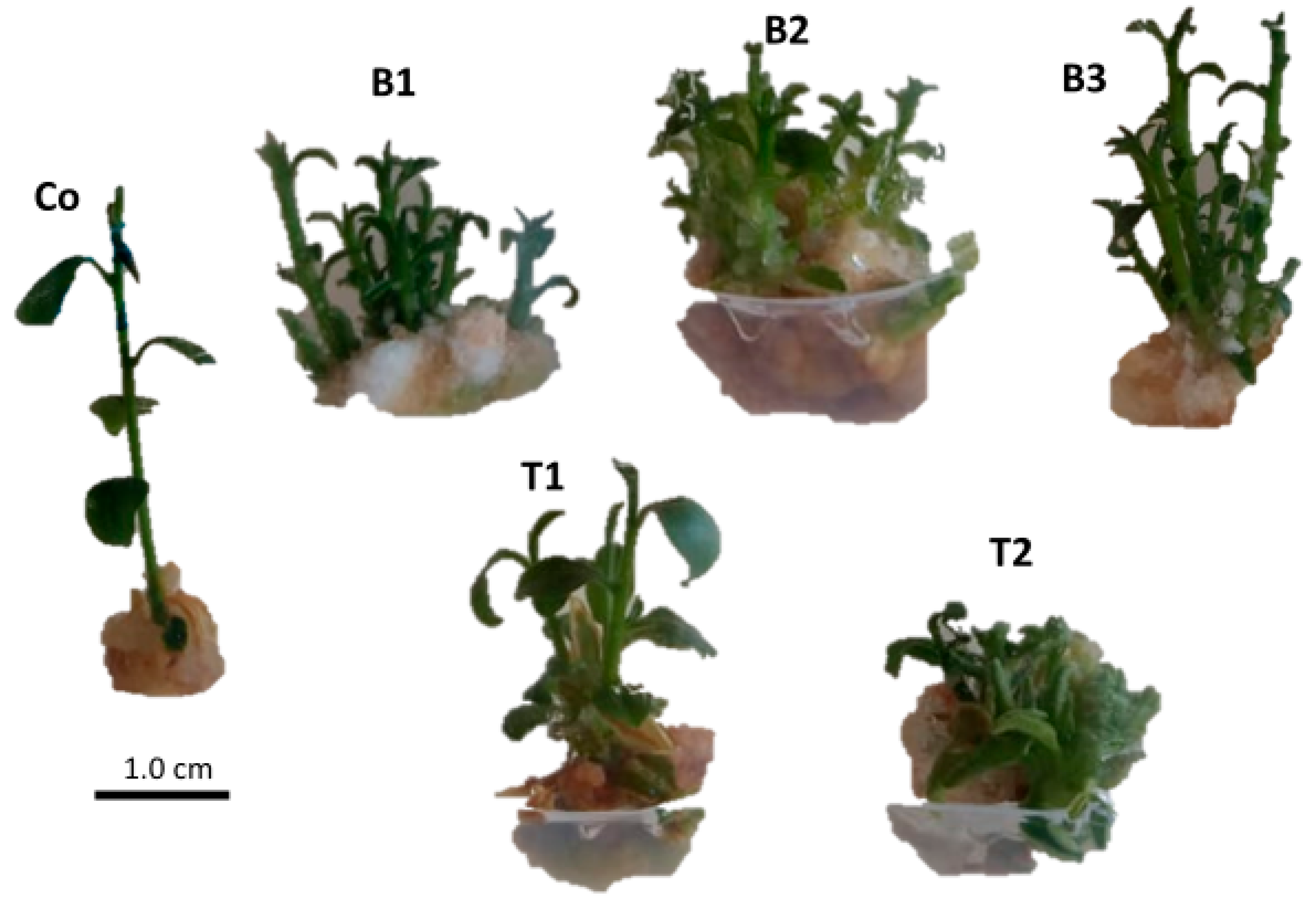

3.2. Effects of Culture Medium and Plant Growth Regulators on Shoot Proliferation Phase

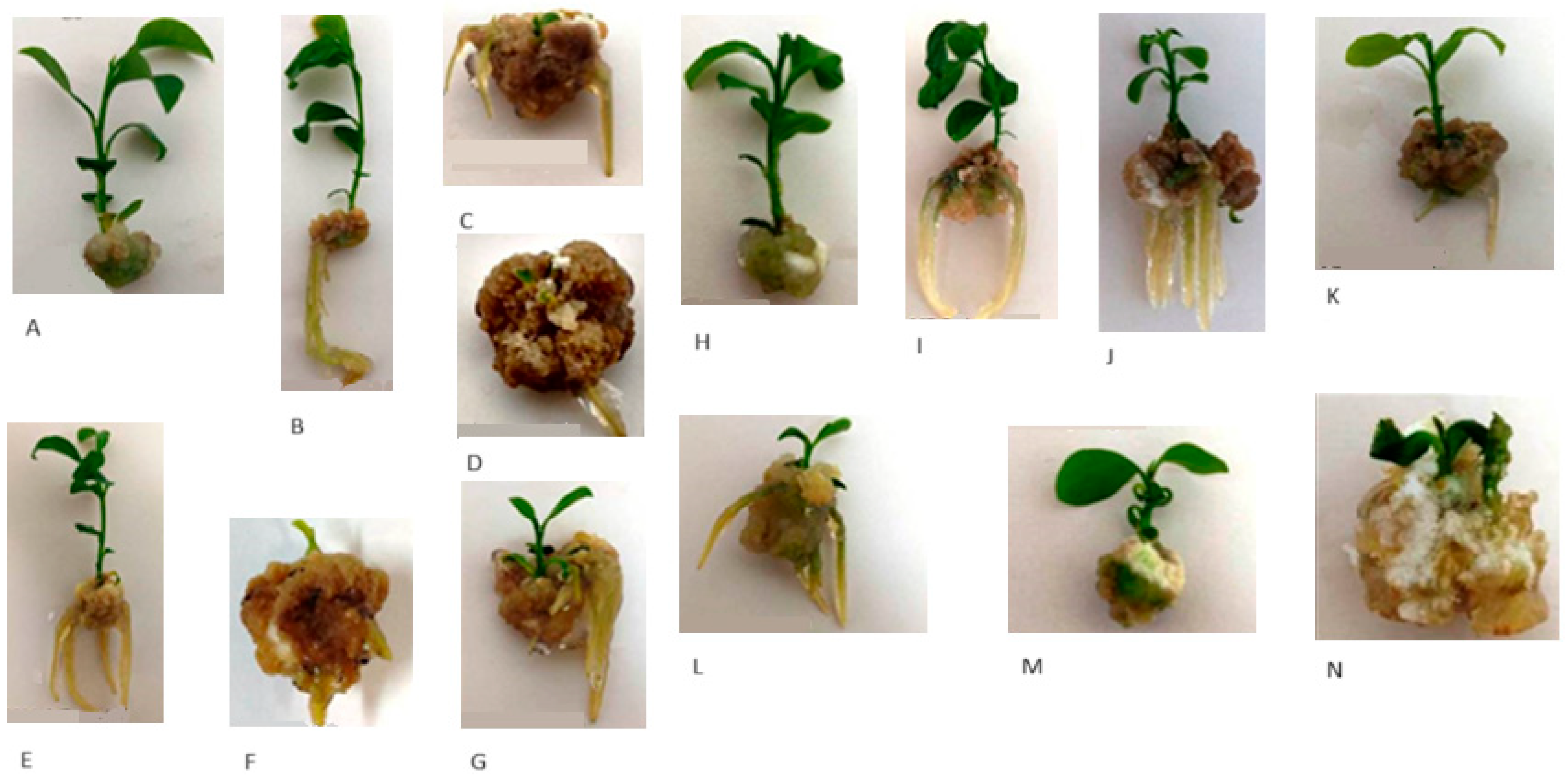

3.3. Effects of Culture Medium and Phytoregulators in the Rooting Phase and Acclimatization

4. Discussion

4.1. In Vitro Establishment

4.2. Effects of Culture Medium and Plant Growth Regulators on Shoot Proliferation Phase

4.3. Effects of Culture Medium and Auxins in the Rooting Phase and Acclimatization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- REFLORA. Available online: https://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/reflora/herbarioVirtual/ConsultaPublicoHVUC/ConsultaPublicoHVUC.do (accessed on 25 Oct 2017).

- Griffiths, M. (1994). Index of Garden Plants. Portland: Timber Press.

- Dias, P. C.; Oliveira, L. S.; Xavier, A.; Wendling, I. Estaquia e miniestaquia de espécies florestais lenhosas do Brasil. Pesq. Flor. Brasil., 2012, 32, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, E.; Nakamura, A. T.; Takaki, M. Época de colheita e capacidade germinativa de sementes de Tibouchina mutabilis (Vell.) Cogn. (Melastomataceae). Biota Neotrop., 2007, 7, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, R.; Shahar, L.; Nissim-Levi, A.; Evenor, D.; Reuveni, M.; Oren-Shamir, M. Shoot regeneration from leaf explants of Brunfelsia calycina. PCTOC 2010, 100, 345–348. [Google Scholar]

- Tarek, A. A.; Shaaban, S. A.; Taha, L. S.; Hashish, K. I.; Gabr, A. M.; Ali, A. I. Encapsulation of Brunfelsia pauciflora microprogated shoots as a suitable conservation protocol. J. Pharm. Negat. Results, 2022, p. 1864-1878.

- Verma, V.; Zinta, G.; Kanwar, K. Optimization of efficient direct organogenesis protocol for Punica granatum L. cv. Kandhari Kabuli from mature leaf explants. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2021, 57, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Khaliluev, M.R.; Bogoutdinova, L.R.; Baranova, G.B.; Baranova, E.N.; Kharchenko, P.N.; Dolgov, S.V. Influence of genotype, explant type, and component of culture medium on in vitro callus induction and shoot organogenesis of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Biol Bull Russ Acad Sci 2014, 41, 512–521. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, G.; McCown, B. Commercially feasible micropropagation of mountain laurel, Kalmia latifolia, by use of shoot tip culture. Plant Prop. Soc., 1981, 30, 421–427. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, S.R.; Desai, N.S.. Effect of TDZ on Various Plant Cultures. In: Ahmad, N.; Faisal, M. (eds) Thidiazuron: From Urea Derivative to Plant Growth Regulator. Springer, Singapore, 2018, pp. 439-454.

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bioassays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSTUDIO TEAM. Avaible online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 12 Set 2018).

- Lameira, O.A.; Pinto, J.E. B. P. In vitro propagation of Cordia verbenaceae L. (Boraginaceae). Rev. Bras. Plantas Med., 2006, 8, 102–104. [Google Scholar]

- Victório, C. P.; Lage, C. L. S.; Sato, A. Tissue culture techniques in the proliferation of shoots and roots of Calendula officinalis. Rev. Ciência Agron., 2012, 43, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulava, S.; Andia, S.; Bhol, R.; Jena, A.; Jena, S.; Bidyadhar, B. In vitro micropropagation of Asparagus racemosus by using of nodal explants. J Cell Tissue Res, 2020, 20, p. 6883-6888.

- Jadid, N.; Anggraeni, S.; Ramadani, M. R. N.; Arieny, M.; Mas’ ud, F. In vitro propagation of Indonesian stevia (Stevia rebaudiana) genotype using axenic nodal segments. BMC Res Notes, 2024, 17, n. 1, p. 45.

- Nazir, U.; Gul, Z.; Shah, G.; Khan, N. Interaction Effect of Auxin and Cytokinin on in Vitro Shoot Regeneration and Rooting of Endangered Medicinal Plant Valeriana jatamansi Jones through Tissue Culture. Am. J. Plant Sci., 2022, 13, 223–240. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, M. S.; Alvi, A. K.; Iqbal, J. Enhanced in vitro regeneration in sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) by use of alternate high-low picloram doses and thidiazuron supplementation. Cytol. Genet., 2021, 55, 566–575. [Google Scholar]

- Schuchovski, C.; Sant’Anna-Santos, B.; Marra, R., Biasi, L. Morphological and anatomical insights into de novo shoot organogenesis of in vitro ‘Delite rabbiteye’ blueberries. Heliyon, 2020, v. 6, n. 11, p. e05468.

- Pereira, F.; Dal Vesco, L. L.; Fermino Junior, P. C. P. Efeito do thidiazuron (TDZ) na propagação in vitro de goiabeira-serrana (Acca sellowiana (O. Berg.) Burret). Sci. Nat., 2020, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, T.; Gul, S.; Khan, A.; Pervez, S.; Noor, A.; Amin, H.; Bibi, S.; Nawaz, M. A.; Rahim, A.; Ahmad, M. S.; Azam, H.; Ullah, H. Range of factors in the reduction of hyperhydricity associated with in vitro shoots of Salvia santolinifolia Bioss. Braz. J. Biol., 2021, 83, e246904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J. G.; Pasa, M. da S.; Dias, C. S.; Loy, F.; Copatti, A. S.; Sommer, L. R.; Deuner, S.; Mello-Farias, P. C. de. Light quality on in vitro multiplication and rooting of ’Woodard’ blueberry. Res. Soc. and Dev. 2021, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hesami, M.; Yoosefzadeh-Najafabadi, M.; Jones, A. M. P. Challenges and opportunities in in vitro rooting of recalcitrant plant species. Front. Plant Sci., 2023, 14, n 1210346. [Google Scholar]

- Ancasi-Espejo, R. G.; Vivado, J. A. A.; & Guzmán, I. M.; Guzmán, I. M. Concentraciones de acido indolbutirico para la formacion de raices en condiciones in vitro de castaña (Bertholletia excelsa bonpl., Lecythidaceae). UNESUM-Cienc. Rev. Cient. Mult. 2023, 7, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Elmongy, M. S.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xia, Y. Root development enhanced by using indole-3-butyric acid and naphthalene acetic acid and associated biochemical changes of in vitro azalea microshoots. J. Plant Growth Regul., 2018, 37, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qarachoboogh, A. F.; Alijanpour, A.; Hosseini, B.; Shafiei, A. B. Efficient and reliable propagation and rooting of foetid juniper (Juniperus foetidissima Willd.), as an endangered plant under in vitro condition. In Vitro Cell.Dev.Biol.-Plant, 2022, 58, 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Kaviani, B.; Barandan, A.; Tymoszuk, A.; Kulus, D. Optimization of In Vitro Propagation of Pear (Pyrus communis L.) ‘Pyrodwarf®(S)’ Rootstock. Agronomy, 2023, 13, n. 1, p. 268.

- Bhojwani, S.S. Dantu, P.K. Tissue and cell culture. In Plant tissue culture. In Plant tissue culture: an introductory text, 1st ed.; Bhojwani, S.S., Dantu, P. K., Eds. 1; Springer: India, 2013; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Arab, M.M.; Yadollahi, A.; Eftekhari, M.; Akbari, M.; Khorami, S.S. Modeling and Optimizing a New Culture Medium for In Vitro Rooting of G×N15 Prunus Rootstock using Artificial Neural Network-Genetic Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2018, v.8, 9977. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H; Elhiti, M.; Wang, H.; Xu, A.; Brown, D.; Wang, A. Adventitious root formation of in vitro peach shoots is regulated by auxin and ethylene. Sci. Hort., 2017, v.226, p.250-260.

- Santana-Buzzy, N.; Canto-Flick, A.; Iglesias-Andreu, L. G.; Montalvo-Peniche, M.C.; López-Puc, G.; Barahona-Pérez, F. Improvement of in vitro culturing of habanero pepper by inhibition of ethylene effects. Hort. Science, 2006, 41, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, P.; Lu, Q.; Liu, Z. , Lv, T.; Li, X.; Bu, H.; Liu, W.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wang, A. Auxin-activated MdARF5 induces the expression of ethylene biosynthetic genes to initiate apple fruit ripening. New Phytol., 2020, 226, 1781–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, S.; Bandopadhyay, R.; Kumar, V.; Chandra, R. Acclimatization of tissue cultured plantlets: from laboratory to land. Biotechnol Lett 2010, 32, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, M.; Munir, M.; Ghazzawy, H.S. Design and Evaluation of a Smart Ex Vitro Acclimatization System for Tissue Culture Plantlets. Agronomy 2023, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, A.V.C.D.S.D.; Oliveira, B. S. D.; Oliveira, M. E. B. S. D.; Cardoso, J. C. AgNO3 improved micropropagation and stimulate in vitro flowering of rose (Rosa x hybrida) cv. Sena. Ornamental Horticulture, 2020, 27, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, A.J.; Bennett, I.J.; Pusswonge, S. The effect of nitrogen source and concentration, medium pH and buffering on in vitro shoot growth and rooting in Eucalyptus marginata. Sci. Hort., 2006, 110, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PGRs (mg L-1) |

Plant height (cm) | Number of leaves per clump | Shoot multiplication rate |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAP | 1.0 | 2.3±0.6 b | 41.6±13.9 a | 7.6±3.5 a |

| 2.0 | 2.1±0.4 b | 38.9±15.3 a | 8.0±2.9 a | |

| 3.0 | 2.3±0.5 b | 40.0±14.3 a | 6.9±2.5 a | |

| TDZ | 0.25 | 2.2±0.7 b | 22.4±8.5 c | 2.6±0.7 b |

| 0.50 | 2.2±0.6 b | 28.7±10.2 b | 2.6±0.7 b | |

| Control | 3.2±0.8 a | 9.6±3.4 d | 1.2±0.4 b | |

| F (PGRs) | 11.10** | 30.79** | 48.41*** | |

| F (culture media) | 0.10NS | 0.37NS | 3.01NS | |

| F (PGR x culture media) | 0.78NS | 0.52NS | 2.10NS | |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 26.32 | 20.71 | 72.24 | |

| Auxins (mg L-1) | Plant height (cm) | Number of leaves per shoot | Mass of calli (g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS ½ | WPM | MS ½ | WPM | MS ½ | WPM | ||

| IBA | 0.5 | 3.1±1.0 aA | 3.7±0.9 aA | 11.6±2.6 aA | 8.6±1.4 bB | 1.1±0.8 aB | 1.7±0.4 aA |

| 1.0 | 2.2±0.9 bA | 2.1±0.7 bA | 8.4±4.0 bA | 6.4±2.8 cA | 1.5±0.8 aA | 1.7±0.8 aA | |

| 1.5 | 2.0±0.6 bA | 2.1±0.3 bA | 8.4±3.2 bA | 6.4±2.1 cA | 1.6±0.9 aA | 2.1±0.6 aA | |

| NAA | 0.5 | 1.5±0.5 cB | 2.2±1.1 bA | 5.8±2.3 cA | 7.8±2.7 bA | 0.8±0.8 bB | 1.9±1.3 aA |

| 1.0 | 1.4±0.4 cA | 1.5±0.3 cA | 5.5±2.5 cA | 5.7±1.7 cA | 0.6±0.7 bA | 1.9±0.9 aA | |

| 1.5 | 1.3±0.4 cA | 1.7±0.4 cA | 6.8±3.4 cA | 6.4±2.9 cA | 0.8±0.7 bB | 2.0±0.6 aA | |

| Control | 2.3±1,0 bB | 3.4±0.7 aA | 9.1±2.3 bB | 12.7±6.2 aA | 0.3±0.2 bB | 1.0±0.2 bA | |

| F (PGRs) | 24.56** | 10.24** | 10.10** | ||||

| F (culture media) | 12.42** | 0.30 NS | 31.68** | ||||

| F (PGR x culture media) | 2.18* | 3.28** | 2.21* | ||||

| CV (%) | 32.25 | 17.62 | 16.76 | ||||

| Auxins (mg L-1) | Rooting percentage | Number of roots | Callus Φ (cm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS ½ | WPM | MS ½ | WPM | MS ½ (1.02 B) | WPM (1.32 A) | ||

| IBA | 0.5 | 91.7±28.86 aA | 58.3±51.49 aA | 5.9±2.68 aA | 2.0±2 aB | 1.26±0.36 b | |

| 1.0 | 66.7±49.11 aA | 50.0±52.22 aA | 3.1±2.15 aA | 1.3±1.48 aB | 1.40±0.46 a | ||

| 1.5 | 83.3±38.92 aA | 58.3±51.49 aA | 2.6±1.78 aA | 1.2±1.19 aB | 1.52±0,50 a | ||

| NAA | 0.5 | 66.6±49.23 aA | 83.0±38.92 aA | 2.0±1.71 bA | 3.7±2.31 bB | 1.12±0.54 b | |

| 1.0 | 16.7±38.88 bB | 58.3±45.23 aA | 0.8±1.53 bA | 2.6±2.74 bB | 0.93±0.46 c | ||

| 1.5 | 33.3±49.23 bA | 66.6±49.23 aA | 0.6±0.99 bA | 1.3±1.14 bB | 1.25±0,49 b | ||

| Control | 16.7±38.92 bB | 25.0±45.22 bB | 0.25±0.62 cA | 0.5±1.80 cB | 0.72±0,41 c | ||

| F (PGRs) | 4.89*** | 15.37 ** | 9,44** | ||||

| F (Culture Media) | 0.25 | 2.17 | 20,53** | ||||

| F (PGRs x Culture Media) | 2.44* | 20.39** | 1,93ns | ||||

| CV (%) | 86.86 | 114.42 | 10.46 | ||||

| Auxins | Survival in | Number of leaves | Chlorophylls content index | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/L) | Acclimatization (%) | /plantlet | Chl A | Chl B | Chl A+B | Chl A/B |

| 0.0 | 81.3 | 5.0±1.4 | 28.6±0.6 | 5.7±0.2 | 34.2±0.8 | 5.0±0.4 |

| 0.5 | 68.8 | 7.0±1.7 | 31.5±3.8 | 7.0±1.7 | 38.5±5.3 | 4.5±0.1 |

| 1.0 | 31.3 | 4.5±1.4 | 28.4±0.5 | 5.6±0.2 | 34.0±0.6 | 5.1±0.3 |

| 1.5 | 31.3 | 5.5±1.4 | 25.6±5.9 | 4.7±1.8 | 30.3±7.8 | 5.4±0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).