1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) has witnessed exponential growth in recent years, with billions of interconnected devices becoming integral to industries such as healthcare, transportation, agriculture, and smart cities [

1,

2,

3]. According to a report by Statista, the number of IoT devices is projected to exceed 30 billion by 2026, reflecting the widespread adoption of technology and its role in driving digital transformation [

4].

However, the rapid expansion of IoT ecosystems has brought with it serious security concerns. One of the most important layers is the firmware layer, one of the lowest and weakest layers in IoT devices [

5]. Unprivileged access to firmware leads to unauthorized control over devices, exposure of confidential data, and interruptions of critical services [

6,

7,

8]. Research indicates that over 25% of IoT-related cyberattacks target device firmware [

9].

Traditional approaches to firmware vulnerability detection face significant challenges in scalability, efficiency, and analytical depth. Manual methods are labor intensive and require specialized knowledge, while current automated tools frequently lack surface context cues necessary for finding complicated vulnerabilities [

10]. This highlights the urgent need for smarter and more adaptive solutions.

Tools like Firmwalker and EMBA (Embedded Malware Behavior Analyzer) have made important strides in firmware analysis. EMBA provides high-level insights into embedded systems and identifies known vulnerabilities [

11], while Firmwalker aids in locating sensitive elements like hardcoded credentials within firmware images [

12]. Despite their contributions, these tools are often limited in detecting deeply rooted or logic-based vulnerabilities that require semantic understanding of firmware code.

Large Language Models (LLMs) offer a transformative opportunity in this domain. With their capacity to comprehend and analyze unstructured code, identify patterns, and extract contextual meaning, LLMs are uniquely equipped to detect vulnerabilities missed by traditional tools [

13]. By integrating LLMs into a customized analysis pipeline, this research seeks to overcome the limitations of current approaches and enhance the detection of firmware vulnerabilities in IoT/OT systems.

A LLM-enhanced pipeline for automatically detecting firmware vulnerabilities is proposed in this study. For deeper contextual insights, it integrates LLMs trained on firmwarespecific datasets, including data from the National Vulnerability Database (NVD) and the Open Worldwide Application Security Project’s (OWASP) IoT Security Testing Guide. The suggested pipeline greatly reduces manual labor by automating every step of the process, from identifying binary targets to producing thorough vulnerability reports. Its modular architecture, which combines pseudo-code analysis and regexbased segmentation to guarantee scalability and adaptability across various firmware ecosystems, is a crucial component. We developed an end-to-end automated pipeline by integrating tools such as Ghidra, EMBA, and Firmwalker with a prompt-driven LLM agent. While existing tools individually contribute to the vulnerability analysis workflow—EMBA for triaging, Ghidra for decompilation, and regex heuristics for chunking our pipeline connects them into a cohesive system. Specifically, the workflow consists of the following steps:

- (1)

Invoking EMBA to identify candidate binaries.

- (2)

Running Ghidra in headless mode to decompile selected firmware into C/C++ pseudo-code.

- (3)

Segmenting the pseudo-code using regex heuristics into analyzable chunks.

- (4)

Feeding each chunk to a custom GPT-4o-based agent that flags potential vulnerabilities and maps them to CWE identifiers.

This integrated approach not only advances traditional static analysis techniques but also enables automated, codelevel vulnerability detection bridging the gap with black-box type testing environments. Unlike theoretical models, this work presents a fully implemented and empirically validated solution, demonstrating high effectiveness in detecting realworld vulnerabilities.

A. Key Contributions

The key contributions of this work are as follows:

LLM-Augmented Analysis: Integration of a GPT-4obased LLM with the OWASP IoT Security Testing Guide to create a firmware analysis agent with enhanced vulnerability detection capabilities [

14].

End-to-End Automated Pipeline: Development of a structured pipeline that combines EMBA, Ghidra, regex-based segmentation, and a prompt-driven LLM agent for scalable and automated firmware vulnerability detection across diverse IoT devices.

Empirical Validation: Technical evaluation of the pipeline using (a) a custom vulnerable binary, (b) the Damn Vulnerable Router Firmware (DVRF) suite, and (c) multiple real-world CVEs, achieving rediscovery of known vulnerabilities with correct CWE mapping.

2. Literature Survey

Firmware vulnerability detection is crucial for maintaining the security of embedded systems and IoT devices. Several tools have been developed to facilitate this process, including:

EMBA: EMBA is an open-source firmware security analyzer designed for embedded devices. It automates the extraction, static analysis, and dynamic analysis of firmware, generating comprehensive security reports. EMBA supports various architectures and file systems, making it versatile for different embedded system [

15].

Firmwalker: Firmwalker is a command-line application that looks for common vulnerabilities in firmware file systems that have been extracted. It looks for private keys, passwords, and configuration files, among other sensitive data. Firmwalker focuses mostly on static analysis and might not be able to identify more complex vulnerabilities, despite being helpful for preliminary assessments [

16].

Ghidra: Developed by the National Security Agency (NSA), Ghidra is a free and open-source reverse engineering tool. It provides capabilities for disassembling, decompiling, and analyzing binary code across various platforms. Ghidra’s extensibility allows users to develop custom scripts and plugins, enhancing its functionality for specific analysis tasks [

17].

Despite their value, these tools are neither without flaws. EMBA and Firmwalker are mainly used for performing static analysis and hence it is possible that they can miss some of the vulnerabilities which occur at run-time. The powerful Ghidra, however is a manual tool and needs expert intervention to understand the decompiled code. These constraints underscore the necessity for a flexible technique that is capable of offering in-depth information into firmware vulnerability analysis.

A. OWASP IOT Security Testing Guide

The OWASP IoT Security Testing Guide provides a comprehensive framework on the testing of IoT devices’ security, including firmware. It outlines test cases and best practices for evaluating various components, emphasizing three key aspects of firmware analysis [

18]. First, the information gathering component identifies and analyzes firmware to understand its structure and components. This approach analyzes firmware code statically for vulnerabilities without the need for execution, looking through coding practices and a potential security vulnerability. This third method of static analysis involves observation of firmware behavior during its execution to thereby find vulnerabilities that static methods may not uncover. These structures serve as a valuable resource in the training of LLMs on firmware vulnerability detection. By incorporating OWASP’s approach, LLMs can more effectively identify patterns and vulnerabilities, enhancing their utility in automated security assessments.

B. Applications of Llms for Cybersecurity

Recent advancements in LLMs have impacted cybersecurity significantly, particularly in vulnerability detection and analysis. Studies have demonstrated the potential of LLMs to address complex challenges in analysing embedded systems and decompiled binaries [

19]. One notable work explores LLMbased taint analysis for Linux-based embedded firmware, where the integration of custom library function analysis enables the detection of command injection vulnerabilities missed by state-of-the-art tools [

20]. Another study focused on improving fuzz testing for BusyBox, a widely used software in embedded devices, by leveraging LLMs to generate intelligent initial seeds and reusing crash data to enhance efficiency, uncovering vulnerabilities in real-world scenarios [

21]. Additionally, research on fine-tuned LLMs, such as ChatGPT 4o, highlights their ability to analyses vast datasets for anomaly detection and vulnerability assessment, showcasing the practical application of pre-trained models in cybersecurity tasks [

22]. A particularly influential work for this paper introduces DeBinVul, a dataset which was designed for decompiled binary vulnerability analysis, enabling LLMs to detect, classify, and describe vulnerabilities with improved accuracy [

23]. This study bridges the semantic gap between source and binary code, achieving significant performance enhancements in tasks such as vulnerability classification and function name recovery. Inspired by these advancements [

24], our work integrates LLMs into firmware analysis pipelines, leveraging tools like EMBA and Ghidra, and extends the application of LLMs to enhance contextual understanding and accuracy in detecting vulnerabilities in IoT device firmware. These methods not only improve the scalability of security assessments but also provide a foundation for developing automated systems that can adapt to emerging threats, enhancing overall cybersecurity environment.

3. Methodology

Large Language Models are powerful machine learning systems that have been trained on a vast amount of human written material. They are able to replicate human abilities by identifying patterns in data. Foundation models, also known as base models, are the result of intensive training employing significant computer resources spanning weeks or months with billions of words. LLMs are capable of performing far more complex jobs since they have billions of parameters that function similarly to the human memory. Working with LLM differs from typical programming in that it uses natural language prompts to produce predictions for the future, eliminating the need to write structured code [

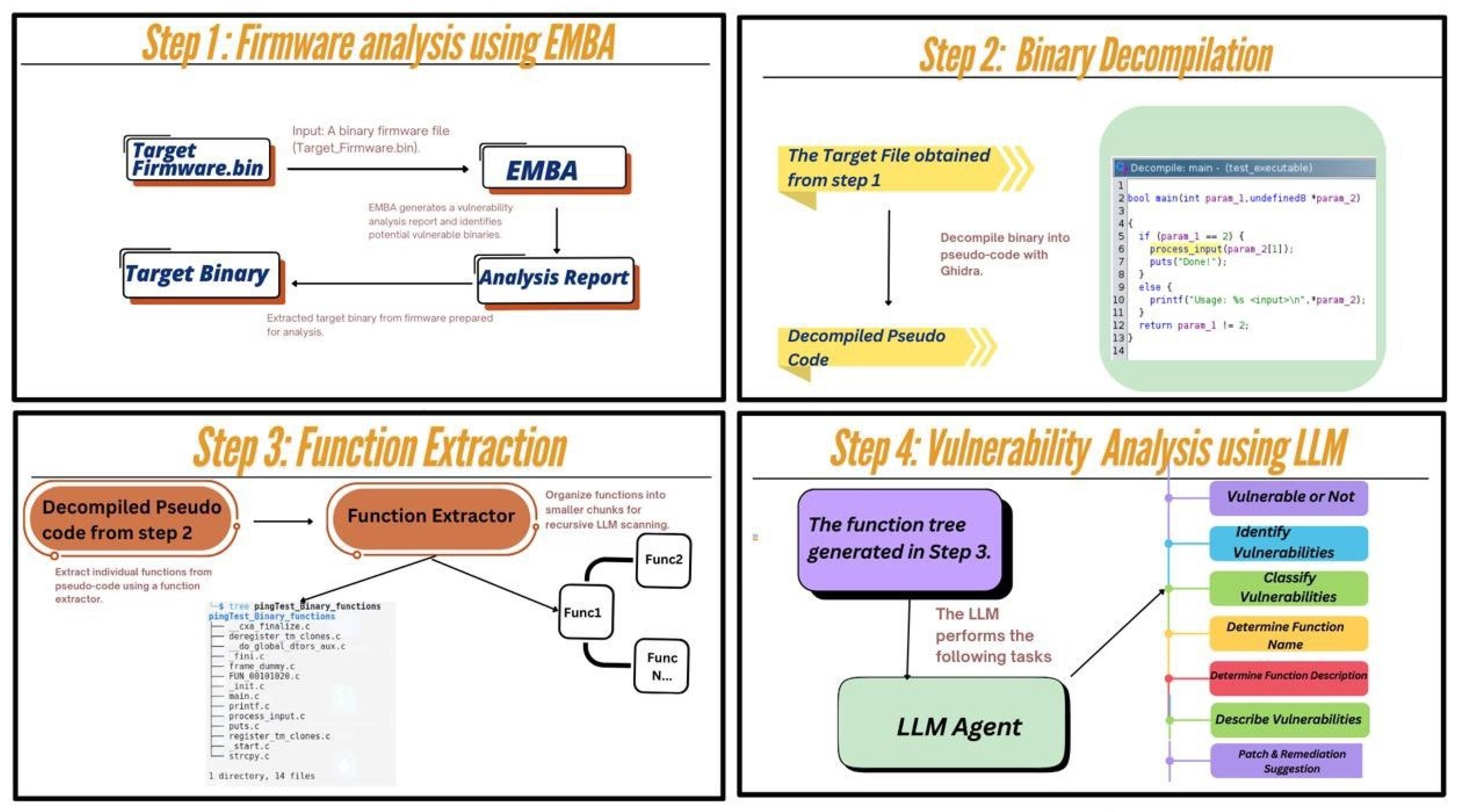

25]. The methodology proposed is an integration of EMBA, Ghidra, and the LLM GPT-4o model into a single executable pipeline for efficient and automated firmware vulnerability detection. It first identifies the relevant binaries through EMBA and then decompiles them using Ghidra. The decompiled code is then preprocessed through regex into smaller sized chunks, ensuring it meets the limited input token requirements for the LLM. The LLM then analyzes the segmented pseudo-code to identify vulnerabilities and provides Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) IDs for identified issues and suggests possible mitigations. This is a modular and automated workflow, hence ensuring scalability and adaptability in variations of firmware types and device architectures.

A. EMBA for Binary Identification

The pipeline begins with EMBA, a tool specifically designed for analyzing embedded systems, which scans firmware images to identify binaries which most likely to contain vulnerabilities. The selection also prefers binaries according to certain criteria including whether they contain sensitive assets (such as hard-coded credentials or crypto keys), were built with a known vulnerable library or functions, and the depth in critical process configurations. It filters out those binaries interested for the subsequent stages, the workload for next steps is reduced dramatically, as a consequence EMBA pipeline works efficiently and in a targeted approach to vulnerability detection.

B. Decompilation with Ghidra

The identified binaries are decompiled using Ghidra, which is robust reverse engineering tool, to generate human-readable pseudo-code. Operated in headless mode, Ghidra automates the decomplication process, bridging the gap between lowlevel binary data and high-level analysis. Given that the decompiled pseudo-code often exceeds the input size limitations of LLMs, a regexbased preprocessing step is applied to segment the pseudo-code into smaller, logically coherent chunks. This ensures that each chunk retains sufficient context for meaningful analysis, enhances processing efficiency, and maintains data completion. This segmentation step is essential for enabling effective LLM analysis while addressing computational constraints.

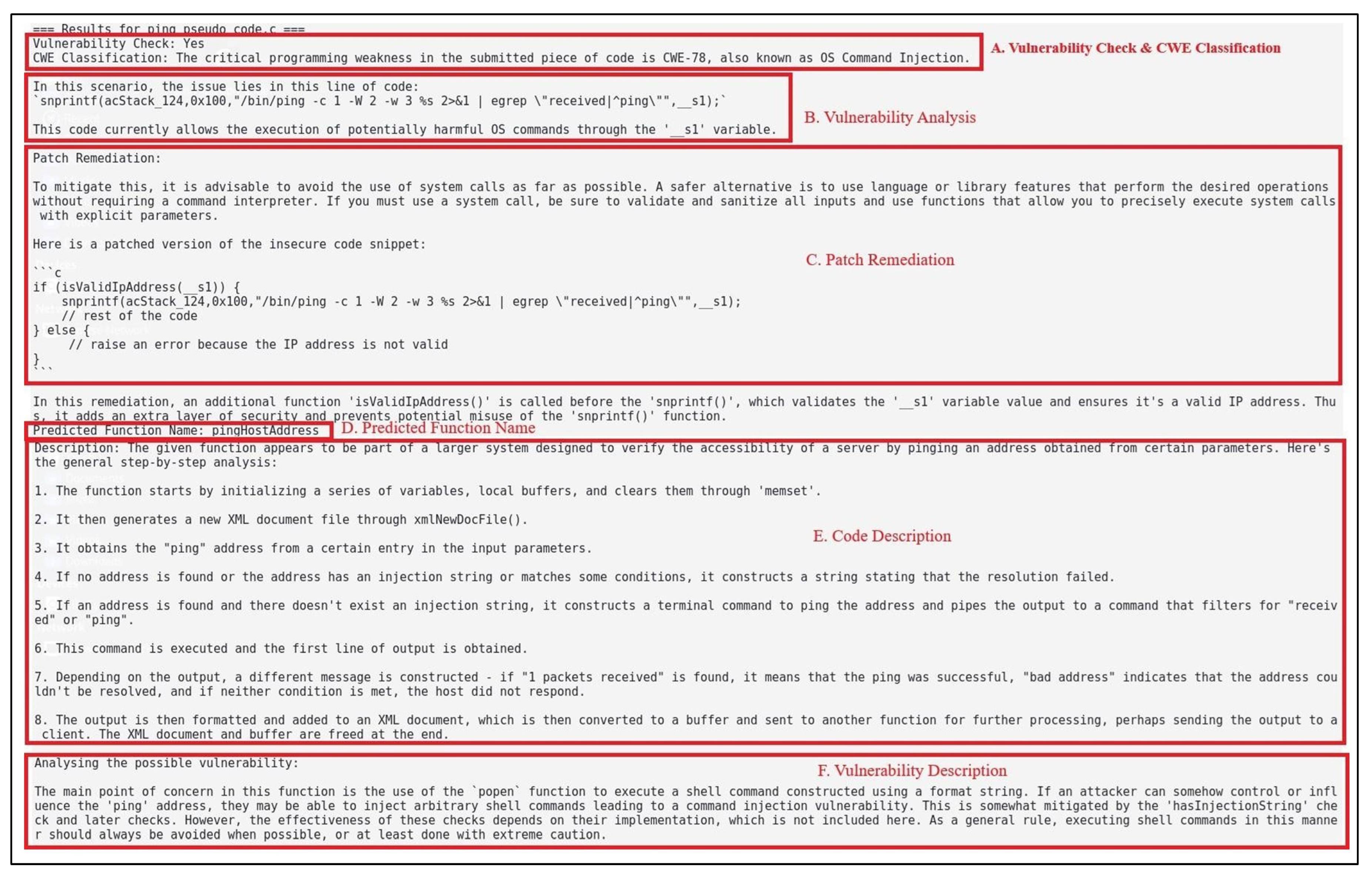

C. LLM Based Vulnerability Detection

The segmented pseudo-code is analyzed by the LLM, leveraging datasets such as the OWASP IoT Security Testing Guide and firmware-specific samples to deliver the precise and detailed vulnerability assessments. The LLM performs several critical functions to enhance the detection process. Firstly, it identifies security flaws such as buffer overflows, injection vulnerabilities flaws, and improper cryptographic practices by recognizing insecure coding patterns. Segmenting pseudo-code with regex tackles the challenge of LLM token limitation. Large firmware binaries result in massive pseudo-code that often goes beyond LLM input capacities. The LLM can go through each part in detail by splitting it into smaller, meaningful segments. This not only enables it to detect vulnerabilities thoroughly, but also ensures that there is no loss of data and that the system is efficient. Also the Firmware decompilation usually generates pseudo-code that goes beyond the LLM token limits. Our regex-based segmentation solves

- (a)

token-budget constraints by dividing the code into coherent chunks

- (b)

context retention by thus ensuring that function and control-flow boundaries are not violated and

- (c)

parallel processing, since multiple chunks can be analyzed at the same time.

Hence, this not only solves performance bottlenecks but also eliminates context-loss issues that are common in most of the artificial intelligence systems.

Secondly, it assigns CWE IDs to detected vulnerabilities, standardizing and contextualizing the findings for better understanding. The LLM then provides actionable mitigation suggestions, allowing developers to address vulnerabilities quickly and effectively. Finally, it generates comprehensive, human-readable vulnerability reports which combines the findings from multiple code chunks offering a holistic view of the any of potential security issues. By incorporating CWE classifications and proposing mitigation strategies, LLMs significantly elevate the detection process, moving beyond mere manual identification to deliver practical and actionable remediation efforts. This capability ensured that the pipeline provides both high-level insights and concise solutions, making it a valuable tool advancement in the field of cybersecurity, machine learning and embedded systems.

D. Architecture Design

The firmware vulnerability detection pipeline integrates the three main components: EMBA, Ghidra, and the predefined custom prompt-based LLM agent into a streamlined and automated workflow. EMBA first scans the firmware to prioritize the binaries that are likely to contain vulnerabilities. These selected binaries are then decompiled by Ghidra into pseudo-code, which is a higher-level representation better suited for analysis. Addressing token limitation, the pseudocode is divided into smaller components called chunks and analyzed by the LLM agent which detects the vulnerabilities, maps CWE IDs, and ensures only relevant binaries undergo in-depth vulnerability scrutiny, making our tool cost efficient and scalable in real-world applications.

E. LLM Development

Unlike traditional training-based machine learning methods, this implementation used a prompt-based, agent-centric approach to leverage the capabilities of advanced pre-trained LLMs and prompt engineering. The LLM agent (GPT-4o) is assigned a specific role as a firmware vulnerability analyzer, with clear instructions to identify vulnerabilities, assign CWE IDs, and suggest actionable mitigations. We embed OWASP IoT Security Testing Guide test cases directly into the LLM prompt context, allowing the agent to map observed code patterns to OWASP test case scenarios. The LLM then assigns the corresponding CWE IDs and cites OWASP best practices when suggesting mitigations. This structured prompt transforms raw pseudocode insights into actionable standard security recommendations.

The decompiled pseudo-code is segmented using a regexbased approach. Our segmentation algorithm prioritizes function boundaries using regex patterns that identify function declarations, control-flow statements, and variable scope indicators. An example regex for function declarations is:

\w+\s+\w+\s*([^)]*)\s*\{

and control-flow constructs are matched using:

if|while|for|switch

This approach ensures chunks are significantly consistent by treating entire functions as primary units, maximizing local completeness. However, because the extractor does not enforce a strict token limit beyond the 4,096 token cap or guarantee uniform overlap, inter-procedural control flow context across chunk boundaries may not be fully preserved. This represents a practical tradeoff, balancing semantic integrity within functions against potential cross-function flow disruptions.

The LLM in our experiments is invoked using standard OpenAI API calls with system and user messages drawn from the project’s analysis scripts. Representative system instructions present in the pipeline include:

- (1)

You are a FIRMWARE SECURITY ANALYST specializing in embedded systems vulnerability detection through static analysis of decompiled IoT binaries across ARM, MIPS, and x86 architectures.

- (2)

Apply systematic vulnerability assessment to the provided DECOMPILED CODE SEGMENT. Output format: STATUS: [VULNERABLE/SECURE] | CONFIDENCE: [High/Medium/Low]

- (3)

For identified vulnerabilities, assign the most specific CWE IDENTIFIER from MITRE taxonomy.

- (4)

Map findings to OWASP IoT Top 10 categories when applicable like: I1 (Weak Passwords), I2 (Insecure Network Services), I3 (Insecure Ecosystem Interfaces), I4 (Insecure Update Mechanisms), I5 (Insecure Data Protection).

- (5)

Provide ROOT CAUSE analysis in format: “VULNERABILITY TYPE | TRIGGER CONDITION | EXPLOITATION VECTOR” (e.g., “BUFFER OVERFLOW | UNCHECKED INPUT LENGTH | STACK CORRUPTION”).

- (6)

Generate MITIGATION recommendations appropriate for them, focusing on: input validation, bounds checking, secure memory management, and best coding practices.

- (7)

Consider DECOMPILATION ARTIFACTS: Acknowledge when analysis is limited by Ghidra decompilation quality, variable naming, or control flow reconstruction issues.

The codebase as used for the results in this manuscript calls the API without explicitly setting sampling parameters such as temperature, thus provider defaults were used, and contains only basic error handling without an automated retry policy. For reproducibility, we therefore recommend that future research adopt deterministic sampling configurations including explicit settings like maximum token limits set to accommodate expected cost structured outputs, together with a simple retry for partial or malformed responses.

Figure 1.

Detailed overview of our proposed approach.

Figure 1.

Detailed overview of our proposed approach.

This approach removes the need for custom model training by relying on thoughtfully crafted prompts and data to guide the LLM’s behavior, ensuring targeted outputs. In doing so, it takes advantage of the efficiency and versatility of pre-trained models, while sidestepping the complexities of developing domain-specific datasets for fine-tuning. A key challenge addressed by this approach is the token limitation of LLMs, as the pseudo-code generated from firmware binaries often exceeds the model’s input capacity. To overcome this problem, the pipeline uses regular expression (regex-based) segmentation to break the pseudo-code into smaller, logically coherent sections, allowing the LLM to analyze each segment iteratively. This repetitive analysis ensures thorough vulnerability detection, with findings from each segment compiled into a unified report. The segmentation process also ensures context retention across chunks, enabling the LLM to provide precise vulnerability assessments and actionable insights, ultimately improving both the scalability and accuracy of the pipeline.

Figure 2.

A high-level overview of our automated pipeline for firmware vulnerability detection using EMBA, Ghidra, and a Large Language Model.

Figure 2.

A high-level overview of our automated pipeline for firmware vulnerability detection using EMBA, Ghidra, and a Large Language Model.

4. Results

Testing the pipeline against a diverse set of firmware samples, including Damn Vulnerable Router Firmware (DVRF), user code with intentional vulnerabilities injected, and binaries associated with previously published CVEs, the pipeline was shown to be able to accurately identify vulnerabilities, providing proper CWE IDs, and recommend mitigations steps. By using the LLM agent, the pipeline successfully processed pseudo-code snippets and actually discovered vulnerabilities in various types of firmware. The outputs were verified through the comparison of detected problems with known vulnerabilities in the test samples, and also by manually inspecting them proving consistent results. To validate the effectiveness of our proposed pipeline, we conducted rigorous testing on Damn Vulnerable Router Firmware and three realworld CVE samples, our pipeline detected all of the known stack and heap-based overflows (CWE-121, CWE-122), all use-after-free instances (CWE-416), and command injection flaws (CWE-78). Importantly, the LLM agent discovered two additional logic flaw patterns that static tools missed, demonstrating the superior contextual reasoning of the pipeline.

This demonstration shows that the pipeline can accurately find real-world security problems, which proves that it is useful and reliable for improving IoT security. These results provide empirical evidence of the effectiveness of the pipeline and its potential to revolutionize vulnerability detection in Internet-based devices.

While EMBA’s prioritization of binaries are based on indicators like hardcoded credentials or known vulnerable libraries which enhances efficiency by focusing on high-risk targets [

26], this triage step may introduce a positive bias in evaluation, potentially inflating detection rates by excluding lower-priority binaries. In our tests, no vulnerabilities were identified in a manual review of 10 randomly selected deprioritized binaries from the DVRF suite, suggesting minimal misses; however, our triage approach may miss some lowlevel vulnerabilities, but the computational cost savings and reduced labor justifies the trade-off for practical deployment scenarios. Future work will explore hybrid approaches that would balance these scenarios.

The evaluation presented here was performed on the Damn Vulnerable Router Firmware suite, one custom vulnerable binary created for controlled verification, and a small set of publicly documented CVEs, this collection was intended to demonstrate the pipeline’s ability to recover diverse vulnerability classes rather than to provide comprehensive coverage of all firmware families, architectures or vendor implementations. We therefore treat the presented results as a proofof-concept (PoC) validation that demonstrate the pipeline’s potential on high-impact targets. Future work could expand coverage to additional firmware families including BusyBoxbased embedded Linux images, and explicit cross-firmware diversity analysis with robust statistics to better establish generalizability across the broader IoT security ecosystem.

A. Future Scope and Discussions

Our suggested pipeline consists of multiple key benefits towards having a more efficient and applicable detection of firmware vulnerabilities. It provides a way better contextual understanding because our custom prompt-based LLM, in line with these expectations.

Table 1 and

Figure 3 captures the details of each test case demonstrating the versatility and accuracy of the tool in detecting various vulnerabilities, whereby the pipeline achieves a much deeper insights into the various vulnerabilities and their contextualization by identifying and including security flaws that might be occasionally ignored by static analysis tools. The ability of the LLM to analyze pseudo-code segments, provide CWE classifications, and return actionable mitigations significantly enhancing the depth and precision of vulnerability detection [

27]. Some other significant advantages that the tool provides is its automation and scalability, since a seamless integration of automated tools for binary identification using EMBA and decomplication with Ghidra minimizes human intervention in the processing of the firmware binaries. This streamlined workflow reduces time and effort for analysis but, more importantly, makes the pipeline highly scalable so that it can be deployed throughout large scale applications for various types of firmware and architectures of IoT devices. With all these put together, the pipeline is seen to be a robust and efficient solution to answer evolving threats in IoT/OT security. However, the proposed pipeline though robust has certain weaknesses. The main weakness is its dependency on the GPT-4o LLM. The performance of the pipeline is intrinsically tied with the capabilities of the pretrained model and with the training dataset of that model. The approach does not perform any fine-tuning therefore, the gaps or biases included in the LLM training dataset are most likely propagated in the vulnerability analysis, mainly regarding emerging or specialized security issues [

28]. While the regexbased segmentation effectively bypasses the limitations of a token by splitting pseudo-code into smaller manageable pieces, processing enormously large binaries or highly complex firmware can be cost intensive. This may take long time for an analysis and procure higher computing needs, so this could become an obstacle for organizations with poor resources or when dealing with firmware from large-scale OT ecosystems [

29]. Several threat vectors can produce spurious results in LLM-assisted firmware analysis. First, decompiler artifacts and placeholder identifiers from tools such as Ghidra can mislead the LLM and cause false positives we therefore recommend cross-validating the findings against raw disassembly patterns and flagging results that depend primarily on decompiler generated identifiers. Second, chunk ordering and context fragmentation which is the result of per-function chunking may obscure inter-procedural flows, our current mitigation is to overlap heuristics and a post-aggregation reconciliation step that combines chunk-level outputs into a firmware-level summary, but we believe this is not the only complete solution. Third, CWE mapping ambiguity arises when natural-language model outputs are not granular enough to unambiguously select a single CWE, to reduce mapping errors we enforce that the LLM returns explicit reasoning when confident, and use rule-based normalization of CWE mappings and route ambiguous cases for human verification. Finally, model could drift as changes in provider models/APIs over time could alter the results. To mitigate this we archived some representative prompts and example outputs used for key claims, and we recommend reporting the exact model identifier and settings used for each experiment. These mitigations are feasible engineering controls that reduce but do not completely eliminate these threats. The above challenges will prove very critical for further research studies.

One of the main points for further studies is the need to handle the weaknesses that LLMs have by their nature and that can be used to as an exploits for cyber-attacks. While LLMs are still very important for security tools, it becomes necessary that developers should improve their safety, by following the good practices given, for example, in the OWASP Top 10 or the MITRE based frameworks. Through strengthening the security positions of LLMs, it is possible to be confident that the pipeline is still strong and trustworthy, thus being able to guard against new threats and being always effective in securing the IoT ecosystems. Building upon these observations, future iterations of the pipeline can address these limitations by integrating multiple strategies. One promising direction is to reduce reliance on a single LLM by exploring ensemble methods that combine the outputs of several models [

30]. Such an approach would not only mitigate the risk of propagating biases from any one training dataset but generalizing it for emerging security issues. Incorporating fine-tuning mechanisms tailored to specific firmware domains could further improve contextual understanding and adaptability to new threat landscapes [

31]. Another key area for improvement is the optimization of resource management. To better handle large datasets and highly complex firmware, the pipeline could benefit from incorporating distributed computing techniques [

32]. For example, employing parallel processing frameworks or cloud-based infrastructures would allow for a more efficient distribution of computational loads [

33]. Furthermore, refining the regex-based segmentation process to minimize overhead could reduce analysis times, making the system more accessible to organizations with limited computing resources.

5. Conclusions

This work presents the pipeline used for detecting firmware vulnerabilities. Specifically, LLMs are combined with tools like EMBA and Ghidra. The new pipeline has improved automation and vulnerability detection in a prompt-based LLM agent that analyzes decompiled pseudo-code suggested CWE IDs and provided step by step actionable mitigation recommendations. This research goes beyond theoretical analysis by presenting a fully functional and validated pipeline that integrates open-source tools with a custom LLM-based agent for automated vulnerability detection. The practical implementation and empirical validation of this pipeline, as demonstrated through the detection of real-world vulnerabilities (e.g., CVE-2024-51186) [

34] (

Figure 3), distinguish this work from mere studies and highlight its tangible impact in the field of security. Hence, setting a new standard for efficient security testing in IoT/OT environments. Thus, it demonstrates the robustness and versatility of the pipeline in the identification of various security vulnerabilities using, on one hand, custom vulnerable code, and known CVEs on Damn Vulnerable Router Firmware. Adding real-time patching and remediation recommendations only makes this approach even more useful practically, further advancing the domain of firmware security analysis. Although the pipeline has proven to be effective, there are several areas for further enhancements and exploration. For future work, including dynamic analysis of firmware behavior at run-time in the pipeline should enable identification of one type of vulnerability that can only arise at run-time. Larger and more diversified data could be used to improve performance, robustness and adaptability of LLMs on different architectures and languages for fine tuning or pre-prompt training.

Yet another promising future development path is to train the LLM so that it can invert the decompiled pseudo-code back into the source code which closely resembles the original firmware where it would be possible to test and analyze in much greater detail. That would bridge the gap between semantics of binaries and source code, enormously enriching the pipeline’s ability to detect and correct vulnerabilities. Those changes would make the pipeline more robust and comprehensive, more effective in fighting the ever-changing problem of IoT firmware security.

References

- Arias, J. Wurm, K. Hoang. Privacy and security in internet of things and wearable devices. IEEE Trans. Multi-Scale Comput. Syst. 2015, 1, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Hung. Leading the IoT: Gartner insights on how to lead in a connected world. Gartner Research 2017, 1–29.

- CISCO. Internet of things at a glance. 2016.

- Statista. IoT connected devices worldwide. 2024. [Online]. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/471264/iot-number-of-connected-devices-worldwide/.

- Nadir, H. Mahmood, and G. Asadullah. A taxonomy of IoT firmware security and principal firmware analysis techniques. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2022, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. C. van Oorschot and S. W., Smith. The Internet of Things: Security challenges. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2019, 17, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. S. Abouzakhar, A. N. S. Abouzakhar, A. Jones, and O. Angelopoulou. Internet of Things security: A review of risks and threats to healthcare sector. in Proc. 2017 IEEE Int. Conf. Internet of Things, Jan. 2018, pp. 373–378. [Online]. Available. [CrossRef]

- M. Frustaci, P. Pace, G. Aloi, and G. Fortino. Evaluating critical security issues of the IoT world: Present and future challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 2483–2495. [CrossRef]

- Palo Alto Networks. The 2023 benchmark report on IoT security.” [Online]. Available: https://tinyurl.com/42m6b469.

- X., Feng; et al. Detecting vulnerability on IoT device firmware: A survey. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sinica 2023, 10, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GitHub. EMBA: IoT firmware security analyzer.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/emba/emba.

- GitHub. Firmwalker: Firmware analysis tool.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/craigz28/firmwalker.

- Z. Sheng, Z. Chen, S. Gu. LLMs in Software Security: A Survey of Vulnerability Detection Techniques and Insights. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.07049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OWASP. Firmware security testing guidelines. [Online]. Available: https://owasp.org/owasp-istg/03_test_cases/firmware/index.html.

- Gupta. Firmware reverse engineering and exploitation. in The IoT Hacker’s Handbook. Apress, 2019. [Online]. Available. [CrossRef]

- J. Ye et al.. Detecting command injection vulnerabilities in Linux-based embedded firmware with LLM-based taint analysis. Comput. Secur., vol. 144, 2024. [Online]. Available. [CrossRef]

- National Security Agency. Ghidra. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/NationalSecurityAgency/ghidra.

- H. Li and L. Shan. LLM-based vulnerability detection. in 2023 Int. Conf. Human-Centered Cogn. Syst. (HCCS), IEEE, 2023.

- D., Manuel; et al. Enhancing reverse engineering: Investigating and benchmarking large language models for vulnerability analysis in decompiled binaries. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.04981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A., Ferrag. Generative AI in Cybersecurity: A Comprehensive Review of LLM Applications and Vulnerabilities. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.12750. [Google Scholar]

- GitHub. Praetorian DVRF.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/ praetorian-inc/DVRF.

- P. Wang, S. P. Wang, S. Huang, and Y. Wu. Comprehensive survey on firmware security for IoT devices. ACM Comput. Surv., 2022.

- National Vulnerability Database (NVD). [Online]. Available: https://nvd.nist.gov.

- S. Greenberg et al.. Automated firmware security assessment using generative AI. Comput. Secur., 2024.

- Vaswani, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. . Attention is all you need. in Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS), 2017.

- OpenAI, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv arXiv:2303.08774, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, Y. Bengio, and A. Courville, Deep Learning. MIT Press, 2016.

- National Vulnerability Database. CVE-2024-51186.” [Online]. Available: https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2024-51186. 2024.

- K. Zetter. Inside the cunning, unprecedented hack of Ukraine’s power grid. WIRED, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.wired.com/2016/ 03/inside-cunning-unprecedented-hack-ukraines-power-grid/. 2016.

- M. Costin et al. Automated dynamic firmware analysis at scale. in Proc. AsiaCCS, 2014, pp. 437–448. [Online]. Available. [CrossRef]

- M. Antonakakis et al. Understanding the Mirai Botnet. in Proc. USENIX Secur. Symp., 2017, pp. 1093–1110. [Online]. Available: https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity17/technical-sessions/ presentation/antonakakis.

- D. Liu et al. AI-based firmware analysis and vulnerability detection: Challenges and future trends. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 50977–50991. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim et al. Binary code similarity detection using neural networks: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–36. [CrossRef]

- MITRE Corporation. Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE). Available online: https://cve.mitre.org/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

Short Biography of Authors

|

Sushant Mane received his B.E. degree in Electronics Engineering from RAIT, Nerul, India, in 2019, followed by an M.Tech. degree in Electronics Engineering from Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute (VJTI), Mumbai, India, in 2022. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Electronics Engineering at VJTI, Mumbai. He has worked on several research and development projects related to embedded systems and cybersecurity. His research focuses on vulnerability analysis, reverse engineering, exploit development, IoT security, and malware analysis. Mr. Mane has found 30+ CVE. He actively participates in cybersecurity workshops and talks. |

|

Jai Bhortake is pursuing a B.Tech. Degree in Electronics and Telecommunication Engineering from Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute (VJTI), Mumbai, India. He has worked on research projects in the areas of artificial intelligence and cybersecurity. His recent work includes intrusion detection in UAVs and the discovery and reporting of CVE registered in the National Vulnerability Database (NVD). His research interests also include machine learning, data science and embedded systems. Mr. Bhortake is also passionate about entrepreneurship and is actively involved in those activities. He has also been recognized with the Best Research Paper Award for his contributions to deep learning. |

|

Vidhi Wankhade received her B.E. degree in Information Technology from Usha Mittal Institute of Technology (SNDTWU), Mumbai, India, and is currently associated with Deloitte. She has worked on various research projects, including a CNN-based Intrusion Detection System for drone security, where she applied machine learning techniques to detect security breaches in UAV systems. Her research work also includes contributions in the areas of network security, secure programming practices, and vulnerability detection. Her research interests include cybersecurity, machine learning for security, programming, and reverse engineering. Ms. Wankhade is actively involved in research activities and continues to explore innovative approaches in the domain of intelligent and secure systems. |

|

Faruk Kazi (Senior Member, IEEE) received the Ph.D. degree in Systems and Control Engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Bombay, India, in 2009. He is currently a Professor of Electronics Engineering with the Department of Electrical Engineering at Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute (VJTI), Mumbai, India, and also serves as the Director of the Research and Development Cell (RDC) at the University of Mumbai, India. His research interests include modeling and control of complex and nonlinear dynamical systems, multi-agent systems, and cyber-physical systems. Dr. Kazi is a Senior Member of the IEEE. He serves as the Chair of the Working Group on Digital Architecture and Cyber Security under the India Smart Grid Forum (ISGF). He is also actively involved in various national and institutional initiatives to promote secure and intelligent infrastructure development. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).