1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the main causative agents of mastitis in milk producing animals and it is also a major human pathogen capable of causing food poisoning, localized infections as well as severe systemic infections because of the possession of multiple toxins and virulence factors [

1]. In addition, the emergence of antibiotic resistant (AR) strains, among which the methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are listed by the World Health Organization among the pathogens of “high priority” against which new antibiotics are urgently needed [

2] is a further threat posed by this bacterial species, since these bacteria cause infections with high mortality rates [

3]. This makes control on the occurrence of this pathogen and AR spread within the species extremely necessary. Indeed, the genetic element conferring the MRSA phenotype is the transferable chromosomal cassette

mec (SCCmec), that can carry the

mecA or the

mecC genes encoding for a penicillin-binding proteins (PBP2a) and genes for site-specific recombinases [

4].

Use of antibiotics in the animal farming sector to treat conditions such as mastitis can select for MRSA transmissible to humans through raw milk and derived products [

5]. Some risk factors have been identified for MRSA transmission in dairy farms, such as poor milking hygiene, while the role of antimicrobial usage has been little investigated [

6] with the exception of one study reporting an increase in antibiotic minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and in the detection of AR genes

tetK,

tetM, and

blaZ after enrofloxacin treatment of persistent mastitis in goats indicating a role of antimicrobial usage on the emergence of AR

S. aureus strains [

7].

Investigating the trends of AR S. aureus prevalence can indicate if risk factors that favor their increase in farms are acting and allow to adopt measures to reduce the dissemination of the genetic determinants implied. Therefore, this study was undertaken to analyze the prevalence of AR S. aureus in farms of the Abruzzo and Molise regions in Central Italy, by taking into account isolates from milk of animals affected by clinical of mastitis that are those mostly exposed to antibiotic treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial strains and culture conditions

The bacterial strains used in this study were all isolated from mastitic milk samples analyzed upon request of veterinarians to the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Abruzzo e del Molise (IZSAM), Campobasso and Lanciano brances, for identification of the infectious agent and antibiogram execution by the standard procedures in use there. Strains phenotypically identified as S. aureus in routine analysis, 27 isolated in year 2021 and 27 in year 2022, were considered. These were propagated by streaking on blood agar (10/l g tryptose, 10 g/l meat extract, 5 g/l NaCl, 15 g/l agar, 100 ml of defibrinated sheep blood added aseptically after autoclaving and cooling of the base medium) incubated in aerobic conditions at 37°C for 24-48 h. Cell biomass from a colony isolated with two subsequent streaks was used for each phenotypic or genotypic test carried out. For long term storage the isolates were maintained in Microbank (Biolife Italiana, Milan, Italy) at -80°C.

2.2. Phenotypic AR testing

The antibiotics tested phenotypically and for occurrence of respective resistance genes were chosen on the basis of the results from the antibiograms for veterinary antibiotics routinely carried out and interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) standards at IZSAM [

8]. The antibiotic classes for which at least one resistant isolate was found were considered and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were determined for the respective antibiotics adopted in human therapy by using the Liofilchem® MIC Test Strips (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, TE, Italy) according to the instructions. Results were interpreted according to the updated EUCAST guidelines (The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 12.0, 2022.

http://www.eucast.org. Accessed on 27 December 2022) and by reference to epidemiological cut off (ECOFF) values available at

https://mic.eucast.org/search/?search%5Bmethod%5D=mic&search%5Bantibiotic%5D=-1&search%5Bspecies%5D=449&search%5Bdisk_content%5D=-1&search%5Blimit%5D=50&page=1.

2.3. Quantitative PCR primer design

New qPCR tests for transferable AR genes occurring in

S. aureus were designed in this study by searching in the databases NCBI (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 1 October 2022) and National Database of Antibiotic Resistant Organisms (NDARO,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/antimicrobial-resistance/, accessed on 1 October 2022) for those most frequently occurring in this bacterial species. For each gene found a BLASTN analysis restricted to the

S. aureus taxon was carried out in order to consider different gene variants to be aligned such to design oligonucleotides targeting all of them. The primer/probe systems designed in this study are listed in

Table 1 with respective target genes and amplicon dimensions. These were synthetized by Eurofins Genomics (Ebersberg, Germany).

The gene regions comprised between each pair of oligonucleotides, ranging in size between 130 and 246 bp, were synthetized upon request by GenScript Biotech (Rijswijk, Netherlands) and delivered as a pUC57 vector construct to serve as positive controls in the qPCR runs.

2.4. DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from one loopful biomass resuspended in 200 µl of Macherey Nagel T1 buffer (Carlo Erba, Cornaredo, MI, Italy) containing 100 mg of sterile 200 µm diameter glass beads in safe lock Eppendorf tubes (Eppendorf). The suspension was bead beaten in a TissueLyser II (Qiagen) at 30 hz for 2 min). Then 200 µl of Macherey Nagel B3 buffer (Carlo Erba) were added and the extraction was continued according to the Macherey Nagel Nucleospin Tissue (Carlo Erba) protocol.

2.5. Quantitative PCR conditions

The qPCR reactions were carried out in a QuantStudio 5 thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rodano, MI, Italy). Identification of isolates at the species level was carried out as described by Poli et al. [

9].For AR gene detection a unique program suitable for all the primer/probe systems designed was used. This comprised initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min and 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s and annealing at 51°C for 30 s. The qPCR reaction of 20 µl volume comprised 10 µl of Takara Premix Ex Taq (Probe qPCR) (Diatech, Jesi, AN, Italy), 0.2 µM primers and probe, TaqMan Exogenous Internal Positive Control Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the recommended concentration, 2 µl of DNA sample and Nuclease Free water (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to the final volume. Four nanograms of the synthetic positive control constructs were used in the positive control reactions. The qPCR tests were run twice to evaluate concordance.

2.6. Veterinarian questionnaire

The veterinarians who requested the bacteriological examinations and antibiograms for mastitis diagnosis in years 2021 and 2022 were interviewed on antibiotic classes prescribed and criteria for antibiotic usage by delivering a questionnaire regarding different aspects of mastitis management in farms.

2.7. Statistical analyses

MIC values plots and Student t test evaluation of distinctness of values obtained for isolates from 2021 and isolates from 2022 were carried out by using PAST 4.03 free statistical software downloaded from

https://past.en.lo4d.com/windows (accessed on 23 December 2022). Data series were considered distinct for P<0.05. Concordance between genotypic and phenotypic resistance was defined for

blaZ gene occurrence and cefoxitin (FOX) resistance by Cohen’s K calculation using an online tool (

https://idostatistics.com/cohen-kappa-free-calculator/ accessed on 27 December 2022). In this concordance analysis the presence of

blaZ and phenotypic resistance were rated “1”, while absence of both was rated “0”. The same concordance test was used to define the agreement of results between replicate qPCR runs.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Rate of mastitis caused by S. aureus in 2021 and 2022

In 2021 the number of farms with clinical mastitis cases caused by S. aureus were 10 among 56 analyzed, while in 2022 farms with S. aureus mastitis cases were 12 among 52 analyzed, accounting for percentages of 17.8 and 23 on the total number of mastitis outbreaks, respectively. More than one isolate was obtained from the same sample if different colony morphologies were observed in routinary bacteriological examination of mastitic milk so 54 S. aureus isolates could be obtained, of which 27 per year. All the isolates were received already phenotypically identified and identification was confirmed by qPCR.

3.2. Phenotypic AR of S. aureus isolates

In phenotyping AR testing the

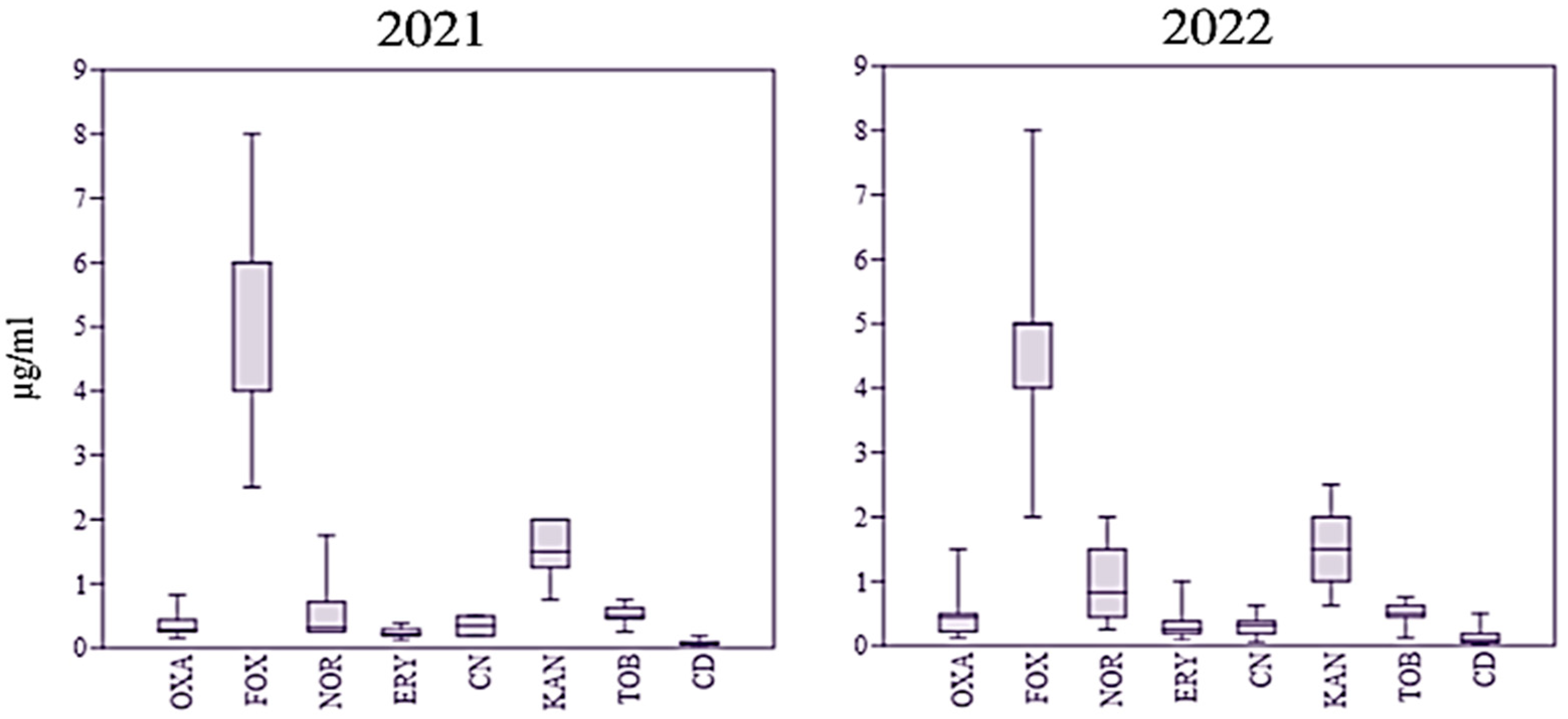

S. aureus isolates were considered resistant to a given antimicrobial if the MIC exceeded the ECOFF value. With this criterion only cefoxitin resistant isolates were identified that were 57% of the 2021 isolates and 61% of the 2022 isolates. One 2022 isolate showed a MIC equal to the ECOFF for oxacillin and the same isolate was also resistant to clindamycin. The distribution of MIC values for each antibiotic tested in the two years is shown in

Figure 1.

It appeared that in 2021 most MICs for cefoxitin were distributed in a wider range of values compared to 2022, while the opposite was observed for norfloxacin and kanamycin. However, the MIC data series for each antibiotic in the two years were not statistically distinct based on the Student’s t test. High occurrence of resistance to β-lactams in

S. aureus is in accordance with the results of a recent systematic review considering data obtained on global scale for strains causing bovine mastitis or milk and dairy products in general [

10,

11]. However, in this study neither the increase in AR to almost all the antimicrobials there reported to occur since 2009, more specifically, clindamycin, gentamycin, and oxacillin, nor resistance to erythromycin were observed.

3.3. Occurrence of AR genes in S. aureus isolates

The AR genes sought in this study were those most frequently occurring in

S. aureus, as evident from the results of database searches carried out at the beginning of this study. This finding was confirmed by a recent survey reporting identity and frequency of AR genes found in 29,679 genomes of

S. aureus isolated worldwide [

12]. In addition, the

cfr gene was also sought since it codes for a 23S rRNA methyltransferase that confers resistance to different antibiotic classes, i.e. phenicols, lincosamides, oxazolidinones, pleuromutilins, and streptogramin A [

13].

The AR gene most frequently detected in this study was

blaZ, present in 59.2% 2021 isolates and in 48.1% 2022 isolates. Differences in the occurrence of this gene between the two years were not statistically significant according to the Student’s t test. In investigations carried out in different countries this AR gene was found at frequencies varying between 16 and 92% [

14,

15].

However, only a few other genetic determinants were identified in the isolates studied here. In particular, the

mecA gene was found only in one 2022 isolate, indicating a frequency lower than reported in other studies [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. According to the genome sequence analysis of Pennone et al. [

12], this gene

is significantly more abundant in human (84%) than in animal isolates (74%), though being highly frequent in both. Therefore, the results of its occurrence from this study indicate that its prevalence can vary on a local basis.

Other AR determinants found in this study, namely aph3’-III, ant6-Ia, ermB, ermC/T and mph, with the exception of ermB found in a 2022 isolate harboring only this gene, were found mostly in association with other AR determinants, suggesting the occurrence of multiresistance genetic elements in a few strains. In particular, MDR genotypes ant6-Ia-aph3-III- blaZ-ermCT and aph3-III- blaZ-ermCT were found each in one 2021 isolate. Moreover, gene mph for resistance to macrolides was found in the only mecA positive strain, though the latter was not resistant to erythromycin as well as the strain harboring ermB.

The concordance between the occurrence of

blaZ and phenotypic resistance to cefoxitin was 44% for year 2021 and 63% for year 2022. According to Ivanovic et al. [

20], who performed whole genome sequence (WGS) analysis, non-functional

bla operons with 31-nucleotide deletion occur in some

S. aureus strains that renders these strains penicillin sensitive. As a consequence, resistance to β-lactams was found to be better assessed by MIC determination. For the isolates exhibiting cefoxitin resistance in this study resistance mechanisms other than

blaZ are involved that should be investigated by WGS and gene function analysis to understand if the resistance is transferable.

3.4. Evaluation of antibiotic usage management by veterinarian interview

In order to connect the results of AR analyses obtained to the antibiotic usage practices adopted locally, the 18 veterinarians providing medical care to the sampled farms were interviewed by a questionnaire regarding farm hygiene, the criteria adopted for antibiotic use decision in mastitis cases and on the antimicrobial agents used in the two years considered. The results of the interviews are presented in

Table 2.

It is possible to observe that all the antibiotic classes allowed for mastitis treatment were used, though β-lactams other than cephalosporins (ampicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) and fluoroquinolones prevailed. Hygiene in the farm was considered good or acceptable in most cases, while milking hygiene was found to be adequate in all instances. Most farms adopted adequate mastitis prevention measures and protocols for antibiotic usage. In addition, half of the interviewed veterinarians declared to be committed to the reduction of antibiotic usage and all the professionals declared use of antibiotics focused on the identified pathogens characterized by antibiograms.

However, according to veterinarian statements, strains causing mastitis were isolated and characterized only in case of recidivating mastitis or in case of treatment failure, and this could imply that part of circulating AR

S. aureus strains are not adequately monitored. The results of the interview explain the rather high prevalence of cefoxitin resistant strains and low occurrence of resistance to other antibiotics compared to what observed in countries where antibiotic usage in mastitis therapy is less controlled [

10]. However, the identification of a MRSA strain and of two strains with MDR genotype and the reporting of AR observation by some veterinarians indicates that the AR management in the farms considered in this study must be further improved.

4. Conclusions

This study showed that the prevalence of both genotypic and phenotypic AR is currently low in S. aureus isolates from the areas of Abruzzo and Molise considered except for β-lactam resistance. This is probably the consequence of overall good farm and milking hygiene, as reported by veterinarian professionals interviewed. No increasing trend was observed in AR prevalence during the two years. However, the occurrence of one MRSA isolate and MDR strains in 2021 suggest to continue monitoring the presence and the AR profiles of S. aureus in dairy herds to understand if these genotypes tend to disseminate. Phenotypic resistance to β-lactams was frequent and the genetic determinants of resistance should be identified in isolates in which the blaZ gene was not detected.

In this study, an effort was carried out to design qPCR tests targeted on AR genes frequent in S. aureus in order to predict the resistance phenotype rapidly. However, there was not a good correspondence between genotype and phenotype, indicating either that MIC determination is more reliable in identifying AR strains, or that AR gene induction mechanisms not triggered by the phenotypic AR testing methods might be involved in AR expression. Nevertheless, these tests should be taken into account for the quantitative assessment of AR S. aureus occurrence directly in clinical, food and environmental specimens in a One Health perspective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R. and I.D.; methodology, F.R., I.D. and M.A.S.; software, F.R.; validation, L.M. and L.R.; formal analysis, F.R., I.D. and M.A.S.; investigation, F.R.; data curation, F.R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.R.; writing—review and editing, L.R.; supervision, L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data obtained in this study can made available by authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The veterinarians participating to the interview are gratefully aknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cheung, G.Y.C.; Bae, J.S.; Otto, M. Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence 2021, 12, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. 27 February 2017 News release, Geneva. https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed. Accessed on 27 December 2022.

- Castro, A.; Santos, C.; Meireles, H.; Silva, J.; Teixeira, P. Food handlers as potential sources of dissemination of virulent strains of Staphylococcus aureus in the community. J. Infect. Public Health 2016, 9, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Chen, D.; Peters, B.M.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Xu, Z.; Shirliff, M.E. Staphylococcal chromosomal cassettes mec (SCCmec): A mobile genetic element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microb Pathog. 2016, 101, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, M.; Latorre, L.; Santagada, G.; Fraccalvieri, R.; Miccolupo, A.; Sottili, R.; Palazzo, L.; Parisi, A. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in sheep and goat bulk tank milk from Southern Italy. Small Rumin. Res. 2016, 135, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitt, A.; Tenhagen, B.A. Risk Factors for the Occurrence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Dairy Herds: An Update. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2020, 17, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, M.C.; de Barros, M.; Scatamburlo, T.M.; Polveiro, R.C.; de Castro, L.K.; Guimarães, S.H.S.; da Costa, S.L.; da Costa, M.M.; Moreira, M.A.S. Profiles of Staphyloccocus aureus isolated from goat persistent mastitis before and after treatment with enrofloxacin. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated From Animals. 3rd ed. CLSI supplement VET01S. 2015, Wayne, PA.

- Poli, A.; Guglielmini, E.; Sembeni, S.; Spiazzi, M.; Dellaglio, F.; Rossi, F.; Torriani, S. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus and enterotoxin genotype diversity in Monte Veronese, a Protected Designation of Origin Italian cheese. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2007, 45, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molineri, A.I.; Camussone, C.; Zbrun, M.V.; Suárez Archilla, G.; Cristiani, M.; Neder, V.; Calvinho, L.; Signorini, M. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Vet Med. 2021, 188, 105261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Jin, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Shi, X.; Zhao, C. Prevalence, antibiotic resistance, and enterotoxin genes of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from milk and dairy products worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Res Int. 2022, 162 Pt A, 111969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennone, V.; Prieto, M.; Álvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Cobo-Diaz, J.F. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes Analysis of Publicly Available Staphylococcus aureus Genomes. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Shen, Z.; Fu, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Schwarz, S.; Shen, J. Distribution of the multidrug resistance gene cfr in Staphylococcus species isolates from swine farms in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 1485–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, X.; Cai, H.; Huang, S.; Ni, Y.; Luo, B.; Qian, H.; Ji, H.; Wang, X. Prevalence and Characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated From Retail Raw Milk in Northern Xinjiang, China. Front Microbiol. 2021, 12, 705947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelam; Jain, V.K.; Singh, M.; Joshi, V.G.; Chhabra, R.; Singh, K.; Rana, Y.S. Virulence and antimicrobial resistance gene profiles of Staphylococcus aureus associated with clinical mastitis in cattle. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0264762. [CrossRef]

- Titouche, Y.; Hakem, A.; Houali, K.; Meheut, T.; Vingadassalon, N.; Ruiz-Ripa, L.; Salmi, D.; Chergui, A.; Chenouf, N.; Hennekinne, J.A.; Torres, C.; Auvray, F. Emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ST8 in raw milk and traditional dairy products in the Tizi Ouzou area of Algeria. J Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 6876–6884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algammal, A.M.; Enany, M.E.; El-Tarabili, R.M.; Ghobashy, M.O.I.; Helmy, Y.A. Prevalence, Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles, Virulence and Enterotoxins-Determinant Genes of MRSA Isolated from Subclinical Bovine Mastitis in Egypt. Pathogens 2020, 9, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghizzi, M.; Shami, A. The prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in milk and dairy products in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021, 28, 7098–7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, A.; Bhattarai, R.K.; Luitel, H.; Karki, S.; Basnet, H.B. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and pattern of antimicrobial resistance in mastitis milk of cattle in Chitwan, Nepal. BMC Vet Res. 2021, 17, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanovic, I.; Boss, R.; Romanò, A.; Guédon, E.; Le-Loir, Y. , Luini, M.; Graber, H.U. Penicillin resistance in bovine Staphylococus aureus: Genomic evaluation of the discrepancy between phenotypic and molecular test methods. J Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).