Submitted:

15 September 2023

Posted:

19 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Work

1.2. Contribution

- The development of a mathematical formalism for the generalisation of kNN to indicate the contribution of various parameters such as dissimilarities and dataspace (Section 2.4);

- Presenting the procedure and circuit for stereographic embedding using the Bloch embedding procedure, which consumes only in time and resources (Section 3.1).

2. Preliminaries

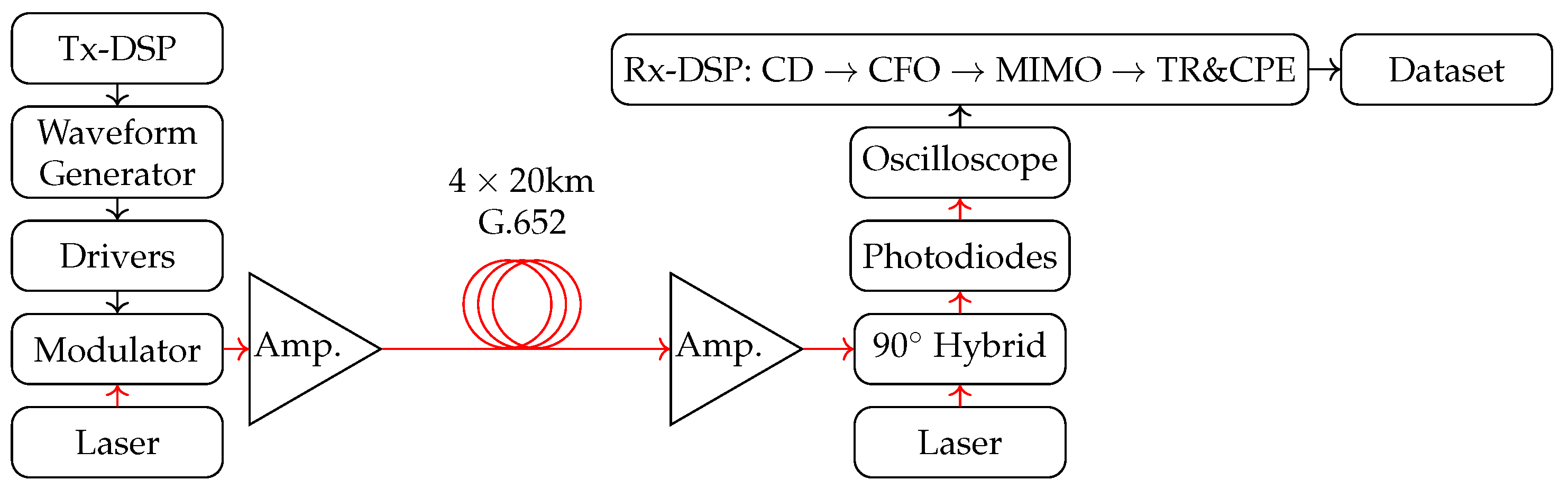

2.1. Optical-Fibre Setup

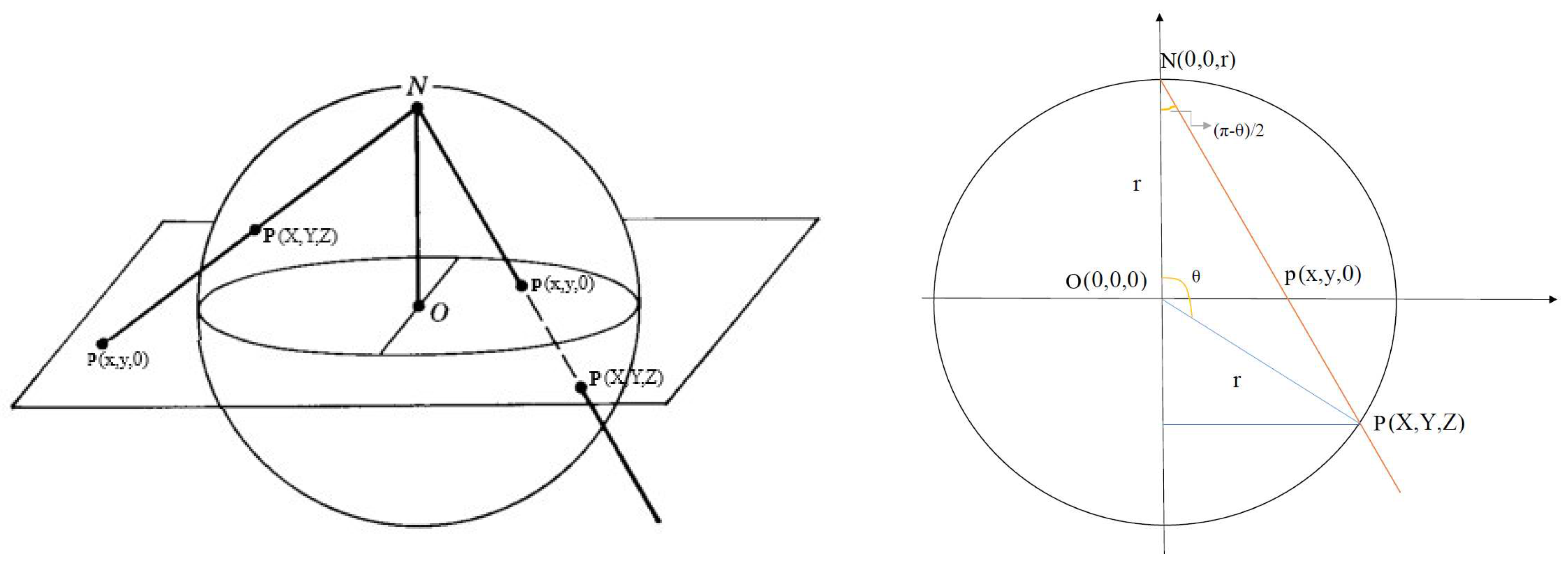

2.2. Bloch Sphere

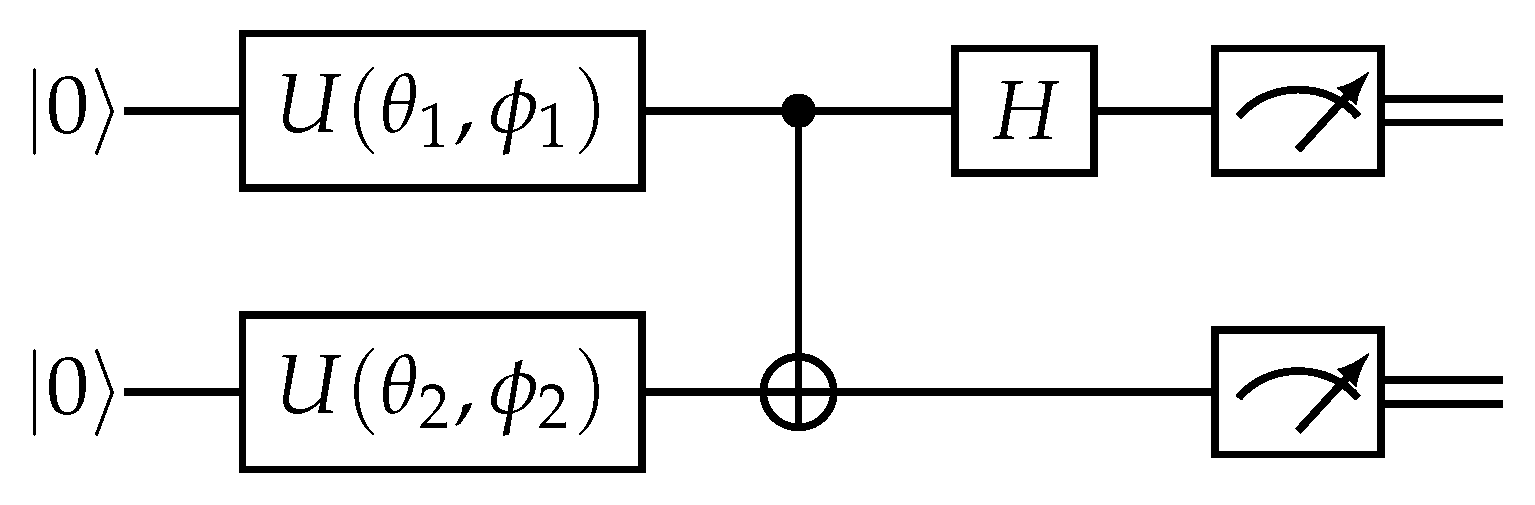

2.3. Bell-State Measurement and Fidelity

2.4. Nearest-Neighbour Clustering Algorithms

- is a space calleddataspacewith elements calledpoints.

- is a subset calleddatasetconsisting of points calleddatapoints.

- is a list (of size k) of points calledcentroids

- is a lower bounded function calleddissimilarity function, ordissimilarityfor short.

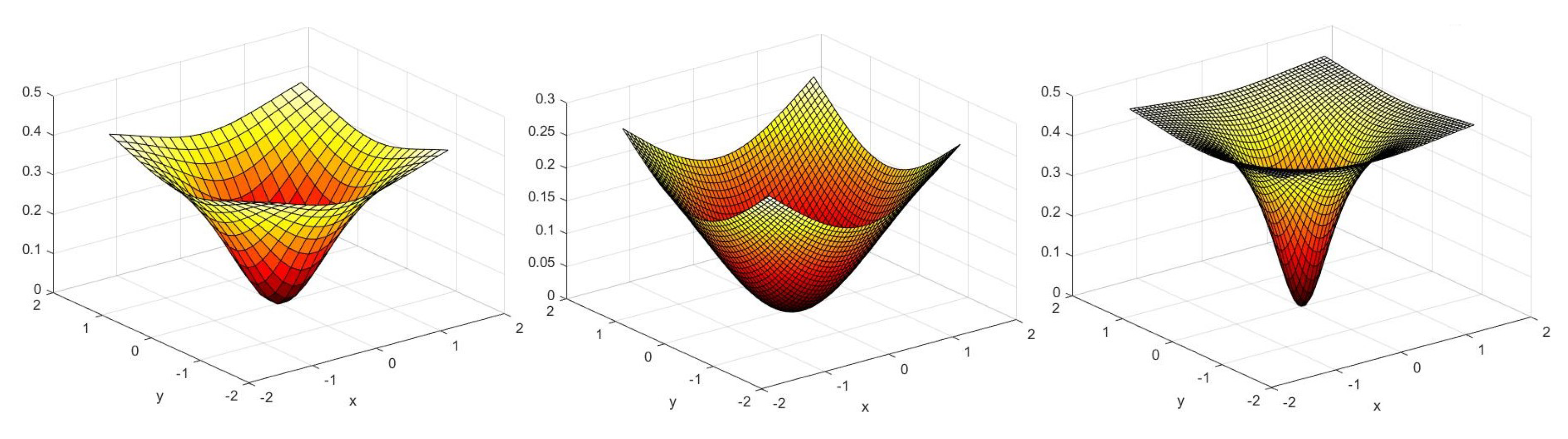

2.5. Euclidean Dissimilarity and Classical Clustering

2.6. Cosine Dissimilarity

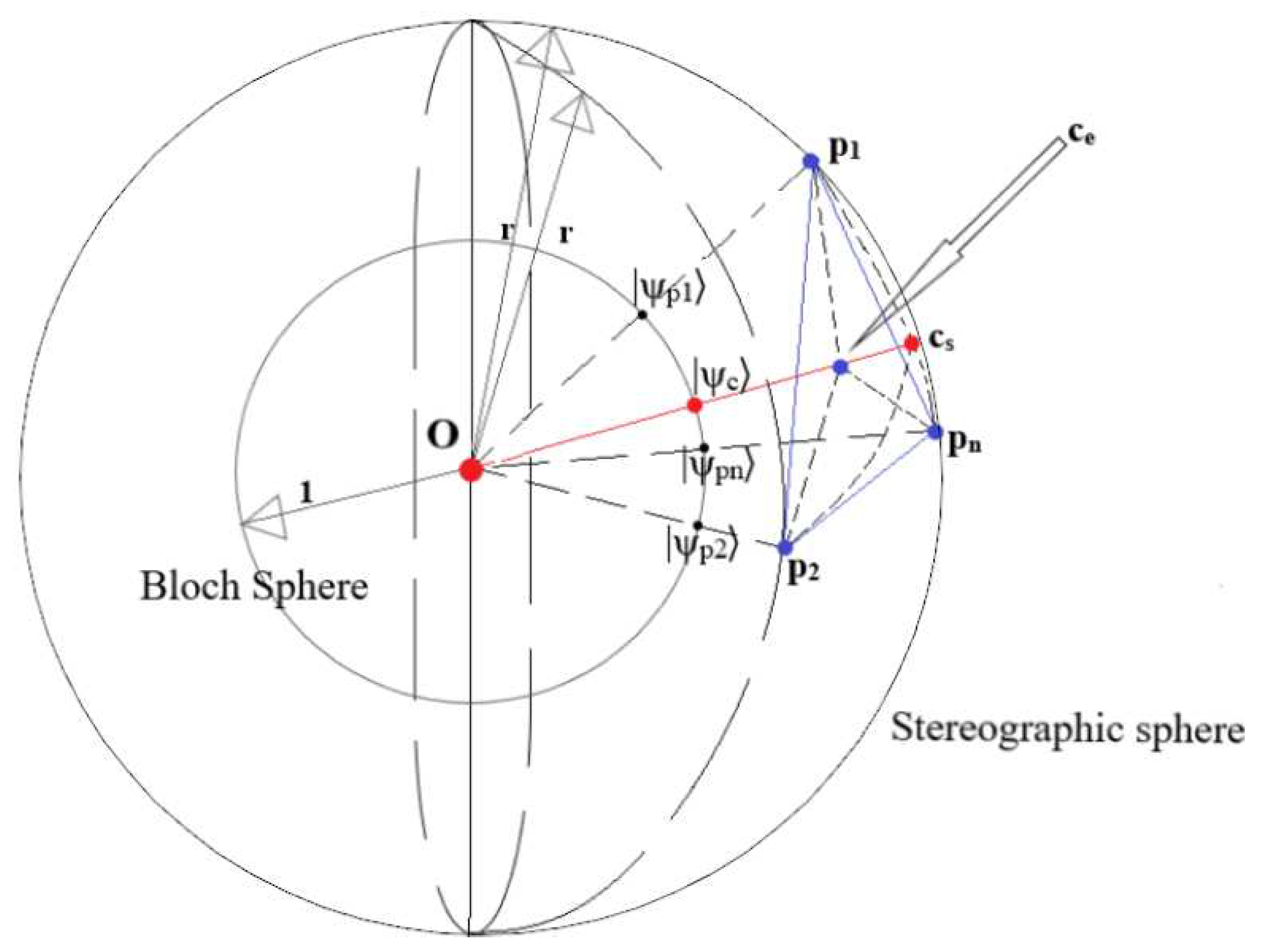

2.7. Stereographic Projection

3. Stereographic Quantum Nearest-Neighbour Clustering (SQ-kNN)

3.1. Stereographic Embedding, Bloch Embedding and Quantum Dissimilarity

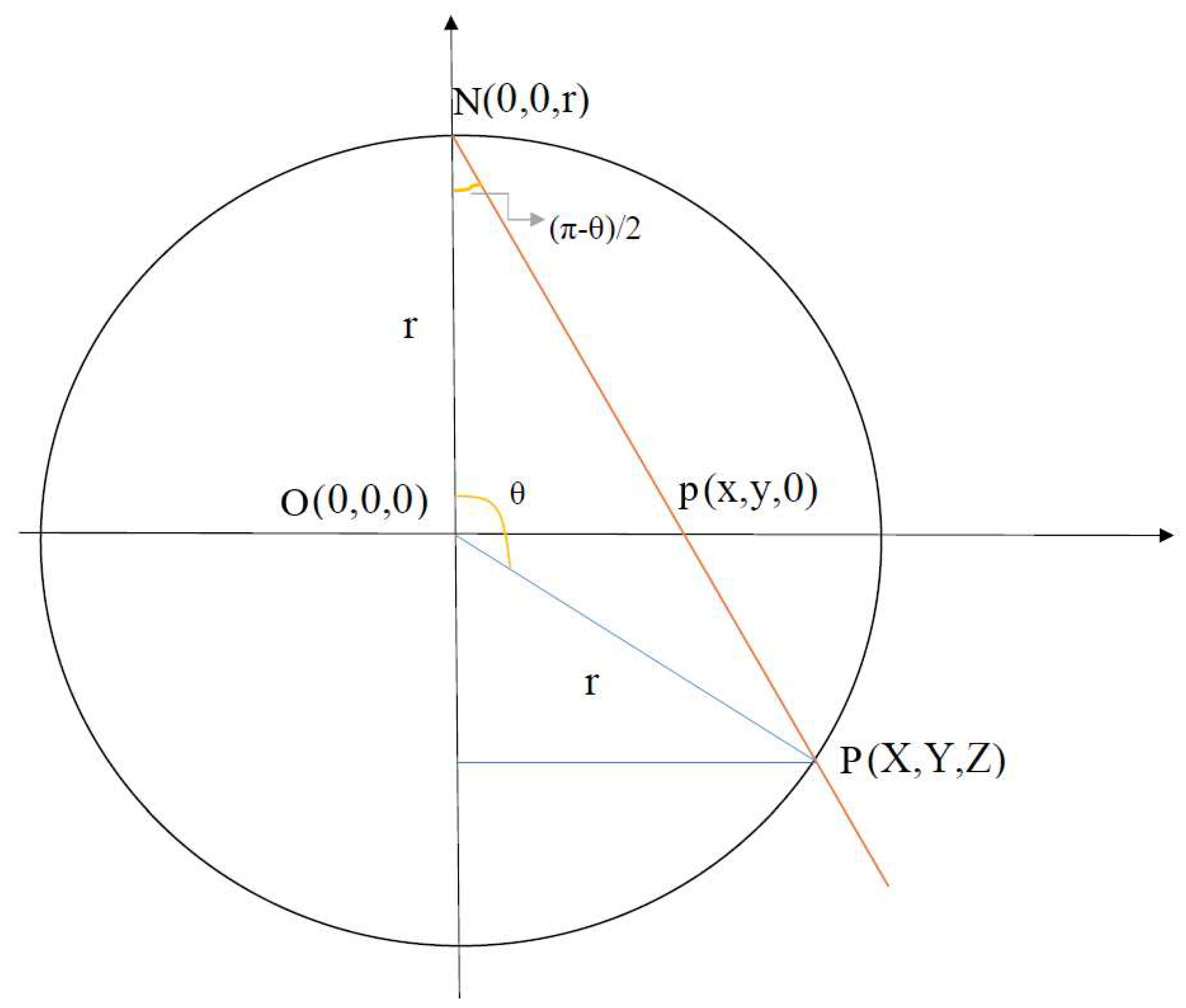

- projecting the 2D point into a point on the sphere of radius r in 3D space through the ISP:

- Bloch embedding into .

3.2. The SQ-kNN Algorithm

- First, prepare to embed the classical data and initial centroids into quantum states using the ISP: project the 2-dimensional datapoints and initial centroids (in our case, the alphabet) into a sphere of radius r and calculate the polar and azimuthal angles of the points. This first step is executed entirely on a classical computer.

- Cluster Update: The calculated angles are used to create the states using Bloch embedding (Definition 7). The dissimilarity between the centroid and point is then estimated using the Bell-state measurement. Once the dissimilarities between a point and all the centroids have been obtained, the point is assigned to the cluster of the `closest’ centroid. This is repeated for all the points that have to be classified. The quantum circuit and classical controller handle this step entirely. The controller feeds in the classical values at the appropriate times, stores the results of the various shots and classifies the point to the appropriate cluster.

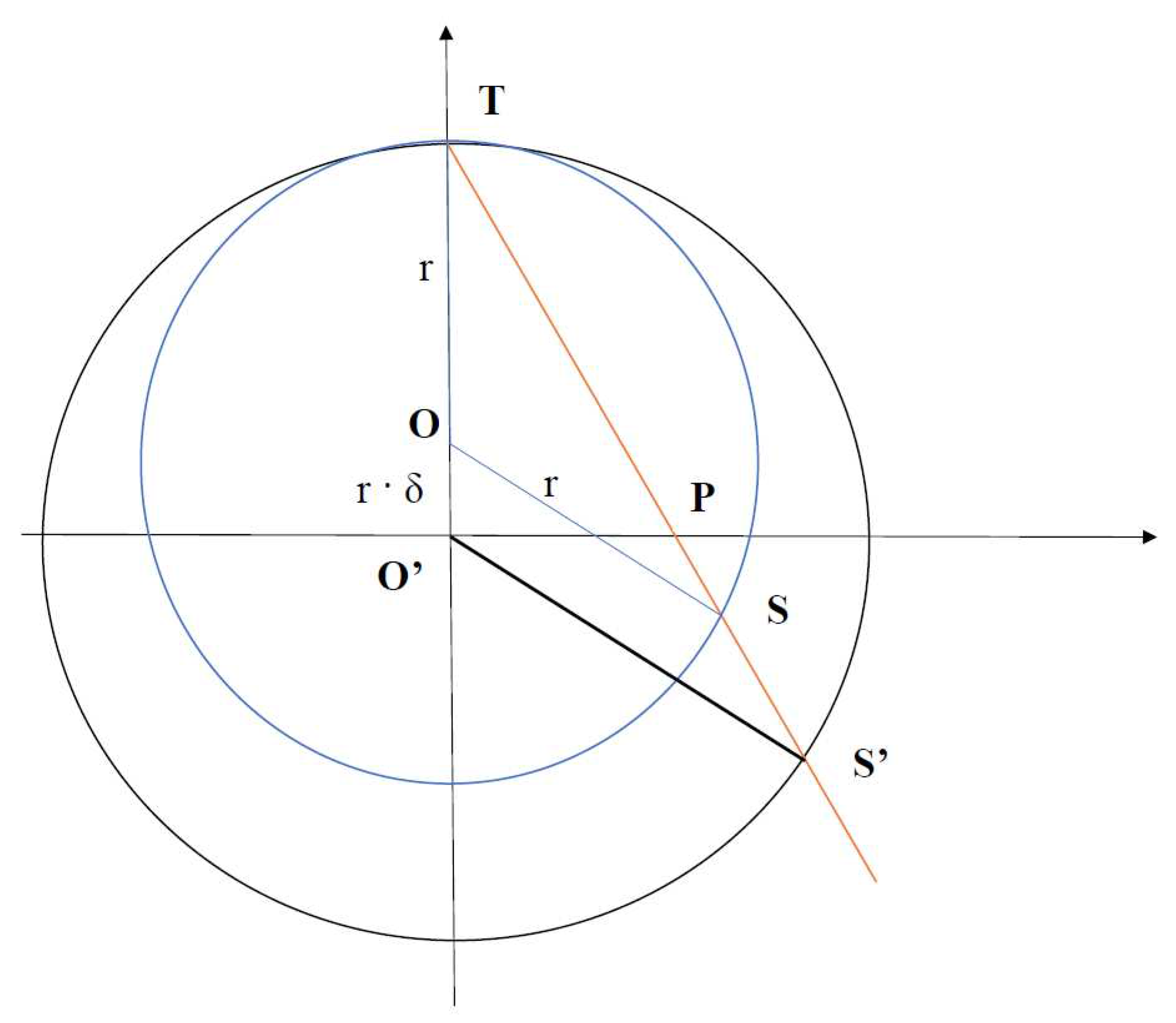

- Centroid Update: Since any non-zero point on the subspace of (see Corollary 1, Figure 4) is an equivalent choice, to minimise computational expense, the centroids are updated as the sum point of all points in the cluster - as opposed to the average, for example, which minimises the Euclidean dissimilarity (Eq. (26)).

-

The stereographic embedding of the 2D datapoints is done by inverse stereographic projecting the point into a sphere of a chosen radius and then producing the quantum state obtained by rescaling the sphere to radius one.In contrast, in angle embedding, the coefficients of the vectors are used as the angles of the Bloch vector (also known as dense angle embedding [47]), while in amplitude embedding, they are used as the amplitudes in the standard basis. For 2D vectors, amplitude embedding allows one to encode only one coefficient (instead of two) in one qubit, and sometimes angle embedding would also encode only one coefficient by using a single rotation (standard angle embedding [48]). Both angle and amplitude embeddings require the lengths of the vectors to be stored classically beside the quantum state, which is not needed in Bloch embedding.

- No post-processing is needed after the overlap estimation of stereographically embedded data as the obtained estimate is already a linear function of the inner product, as opposed to standard approaches using angle or amplitude encoding. Amplitude embedding also requires non-trivial computational time in the state preparation process. In contrast, in angle embedding, though the state preparation time is constant, recovering a useful dissimilarity (e.g. Euclidean) may involve many post-processing steps.

3.3. Complexity Analysis and Scaling

3.3.1. Using Qubit-Based System

3.3.2. Using Qudit-Based System

3.4. SQ-kNN and Mixed States

4. Quantum-Inspired Stereographic -Nearest-Neighbour Clustering

- Stereographically project all the 2-dimensional data and initial centroids into the sphere of radius r. Notice that the initial centroids will lie on the sphere by construction.

- Cluster Update: Form the clusters using the method defined in Eq. (22), i.e. form all . Here, and dissimilarity (Definition 5 and Lemma 2).

- Centroid Update: A closed-form expression for the centroid update was calculated in Eq. (41) . This expression recalculates the centroid once the new clusters have been formed. Once all the centroids are updated, Step 2 (cluster update) is then repeated, and so on, until a stopping condition is met.

| Algorithm | Reference | Dataset | Initial | Dataspace | Dissimilarity | Centroid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centroids | Update | |||||

| D | d | |||||

| 2DEC-kNN | Definition 4 | D | ||||

| 3DSC-kNN | Definition 6 | |||||

| 2DSC-kNN | Definition 12 | (or ) | ||||

| SQ-kNN | Definition 10 |

4.1. Equivalence

- ,

- and ,

- for all and any .

4.2. Complexity Analysis and Scaling

5. Experiments and Results

- The hardware performance and availability of quantum computers (NISQ devices) is currently so much worse than that of classical computers that no advantage can likely be obtained with the quantum algorithm.

- The goal of this paper is not to show a “quantum advantage” in time complexity over the classical k-means in the NISQ context - it is to show that stereographic projection can lead to better learning for classical clustering and be a better embedding for quantum clustering. In particular, the equivalence between 2DSC-KNN and SQ-KNN proves that noise is the only limitation for the stereographic quantum algorithm to achieve the accuracy of the quantum-inspired algorithm.

- Radius: the radius of the stereographic sphere into which the 2-dimensional points are projected.

- Number of points: the number of points upon which the clustering algorithm was performed. For every experiment, the selected points were a random subset of all the 64-QAM data (of a specific noise) with cardinality equal to the required number of points. The random subset is created using the numpy.random.sample() from the Python Numpy library.

- Number of runs: Since for each choice of parameters for each experiment we select a subset of points at random, we repeat each of the experiments many times to remove bias from the random choice and obtain stable averages and standard deviations for the collected performance parameters (described in another list below). This number of repetitions is the “number of runs”.

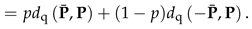

- Dataset Noise: As explained in Section 2.1, data was collected for four different input powers. The data is divided into four datasets labelled with powers 2.7, 6.6, 8.6 and 10.7 dBm.

- Natural endpoint: The natural endpoint of a clustering algorithm occurs wheni.e. when all the clusters remained unchanged (stay the same) even after the centroid update. It is the natural endpoint since if the clusters do not change, the centroids will not change either in the next iteration, leading to the same clusters (Eq. (85)) and centroids for all future iterations.

- 2DSC-kNN: The quantum-analogue algorithm of Definition 12, the classical equivalent of the SQ-KNN and the most important candidate for our testing.

- 2DEC-kNN: The standard classical kNN of Definition 4 implemented upon the original 2-dimensional dataset (), which serves as a baseline for performance comparison.

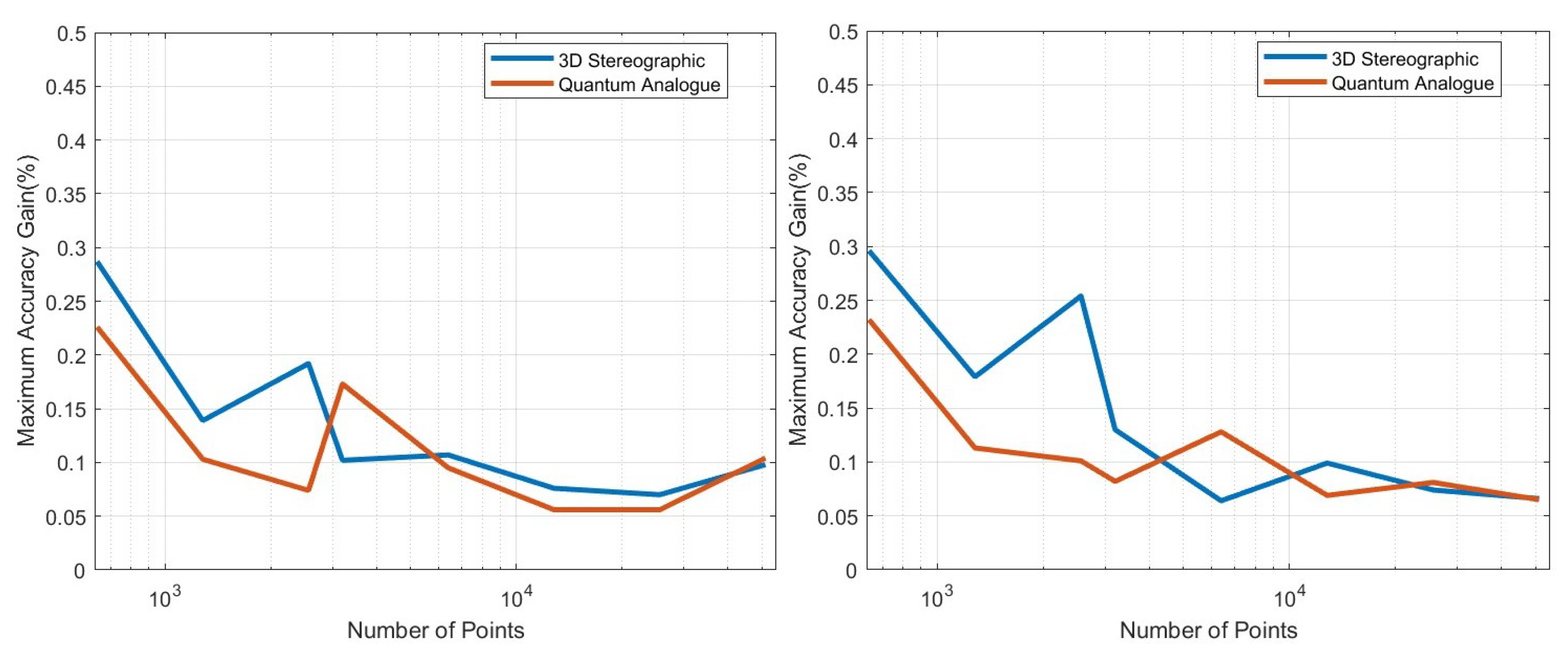

- 3DSC-kNN: The standard classical kNN, but implemented upon the stereographically projected 2-dimensional dataset, as defined in Definition 6. We again emphasise that in contrast to the 2DSC-kNN the centroid lies within the sphere, and in contrast to the 2DEC-kNN, the clustering takes place in . This algorithm serves as another control, to gauge the relative impacts of stereographically projecting the dataset versus restricting the centroid to the surface of the sphere. It is an intermediate step between the 2DSC-kNN and the 2DEC-kNN algorithms.

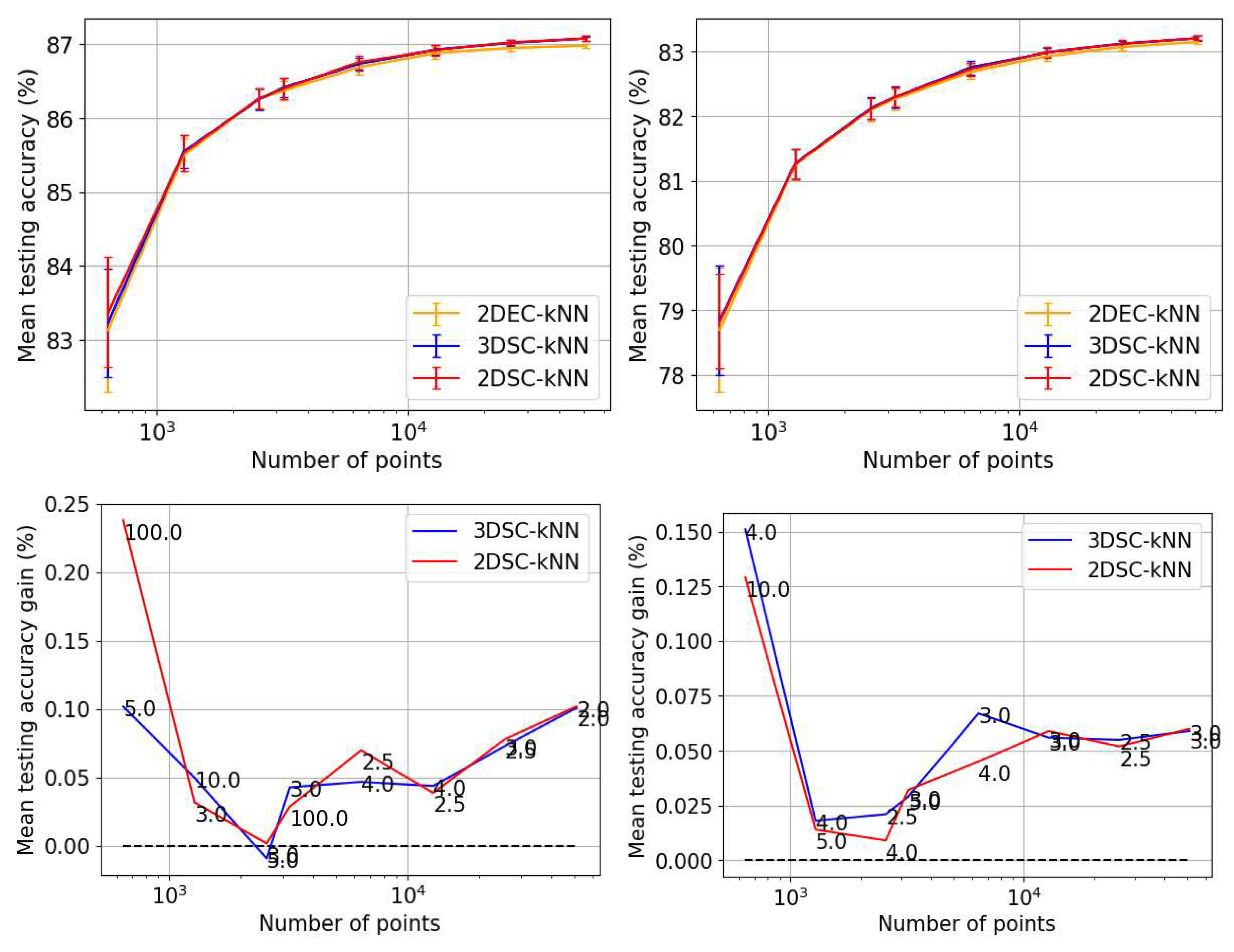

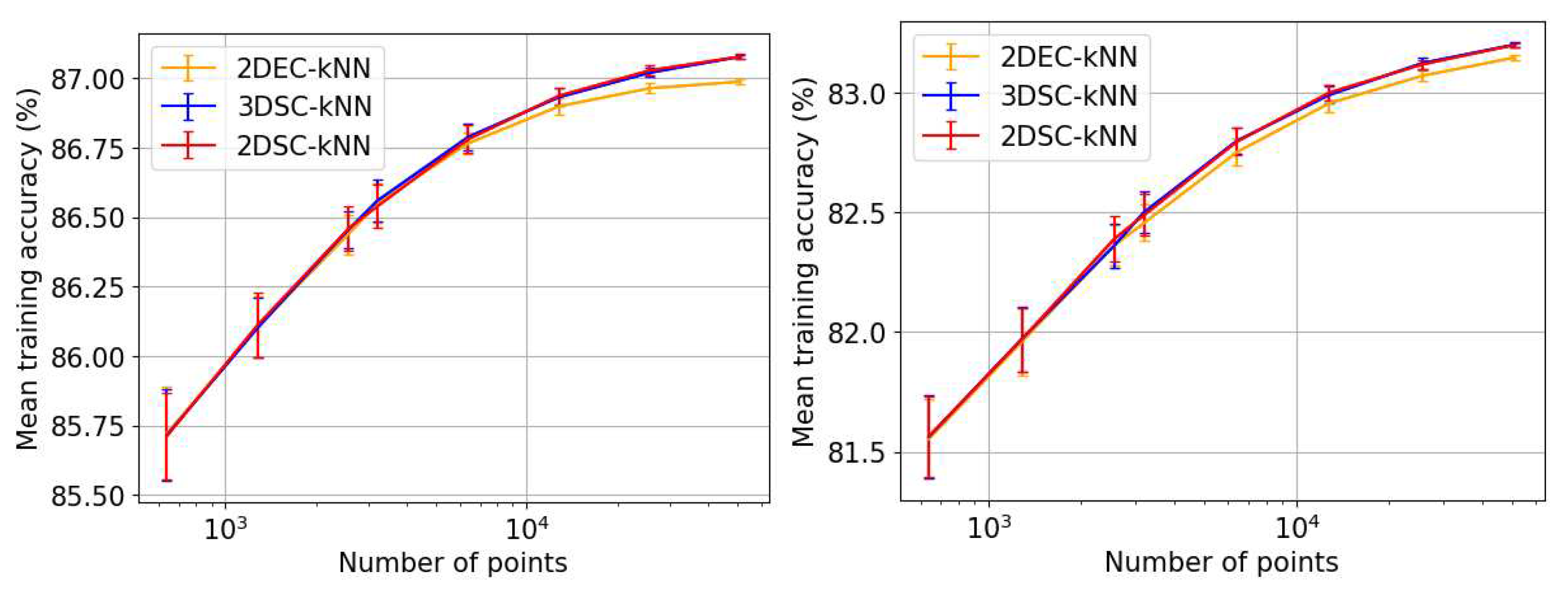

- Accuracy: Since we have the true labels of the datapoints available, we can measure the accuracy of the algorithm as the percentage of points that have been given the correct label, i.e. symbol accuracy rate. All accuracies are recorded as a percentage.

- Symbol or Bit error rate: As mentioned in Appendix A, due to Gray encoding, the bit error rate is approximately of the symbol error rate, which in turn is simply one minus the accuracy. Although error rates are the standard performance parameter in channel coding, we decided to measure the accuracy instead, which is the standard performance parameter in machine learning.

- Accuracy gain: The gain is calculated as (accuracy of candidate algorithm - accuracy of 2-dimensional classical k-means clustering algorithm), i.e. it is the increase in accuracy of the algorithm over the baseline, defined as the accuracy of the classical k-means clustering algorithm acting on the 2D dataset for those number of points.

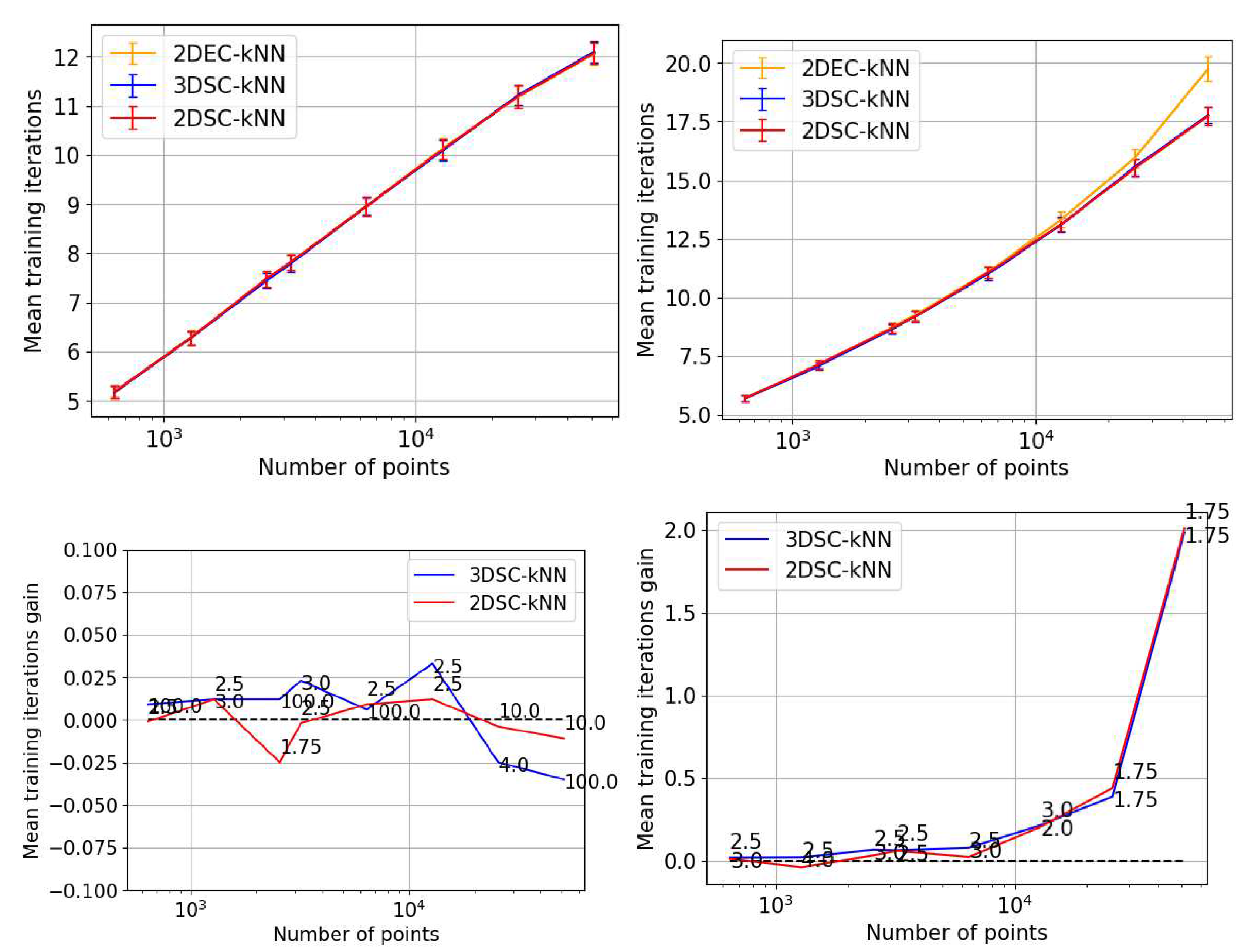

- Number of iterations: One iteration of the clustering algorithm occurs when the algorithm performs the cluster update followed by the centroid update (the algorithm must then perform the cluster update again). The number of times the algorithm repeats these two steps before stopping is the number of iterations. We use the number of iterations the algorithm requires to reach its `natural endpoint’ as a proxy for convergence performance. The lesser the number of iterations performed, the faster the algorithm’s convergence. The number of iterations does not directly correspond to time performance since the time taken for one iteration differs between all algorithms.

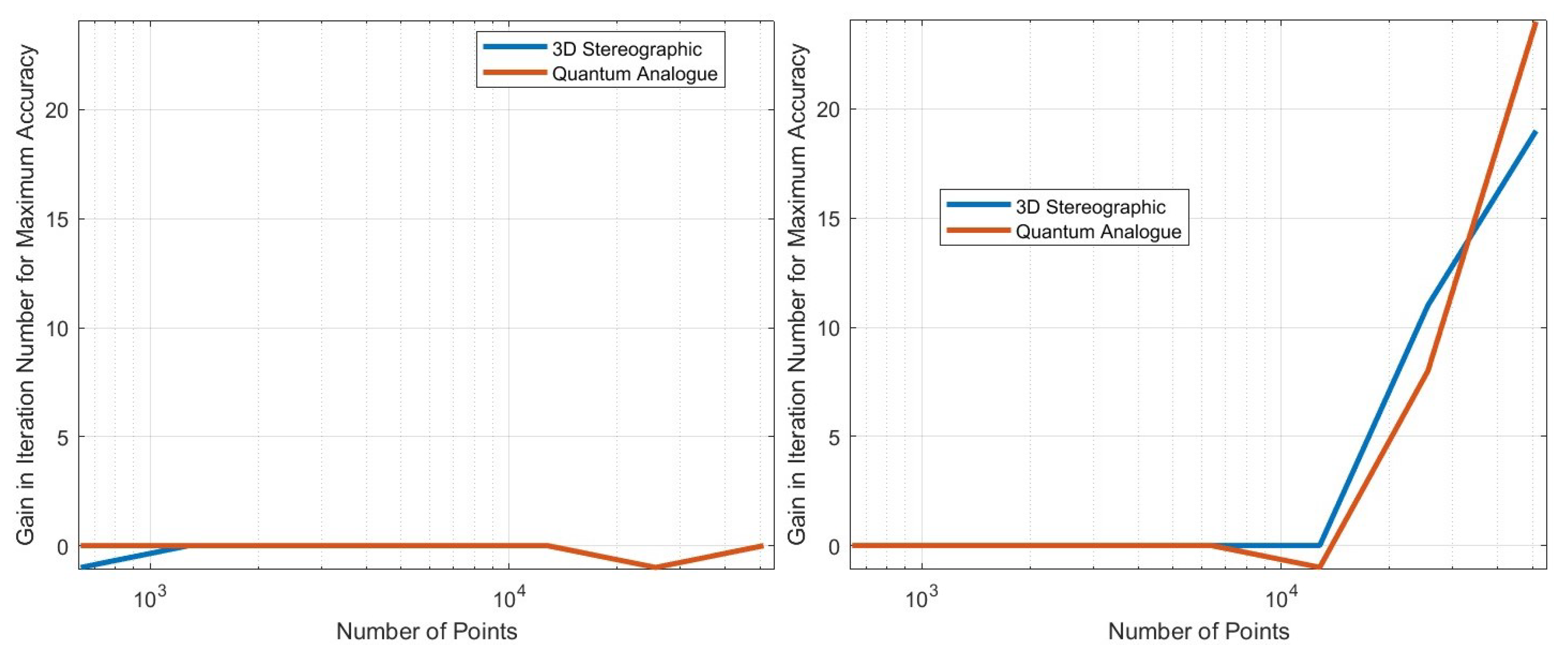

- Iteration gain: The gain in iterations is defined as (the number of iterations of 2D k-means clustering algorithm - the number of iterations of candidate algorithm), i.e. the gain is how many fewer iterations the candidate algorithm took than the 2DEC-kNN algorithm to reach its natural endpoint.

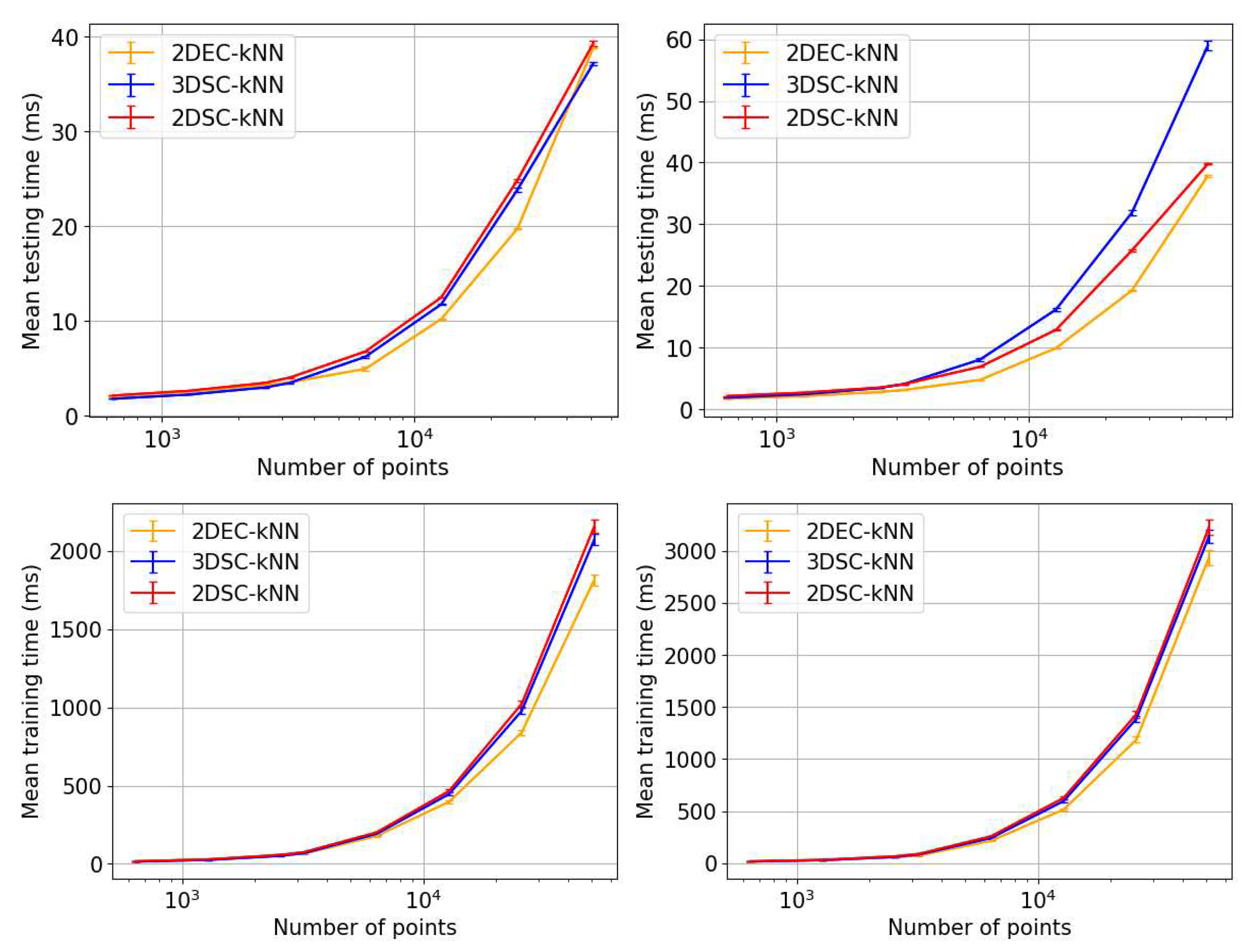

- Execution time: The amount of time taken for a clustering algorithm to give the final output (the final centroids and clusters) given the 2-dimensional data points as input, i.e. the time taken end to end for the clustering process. All times in this work are recorded in milliseconds (ms).

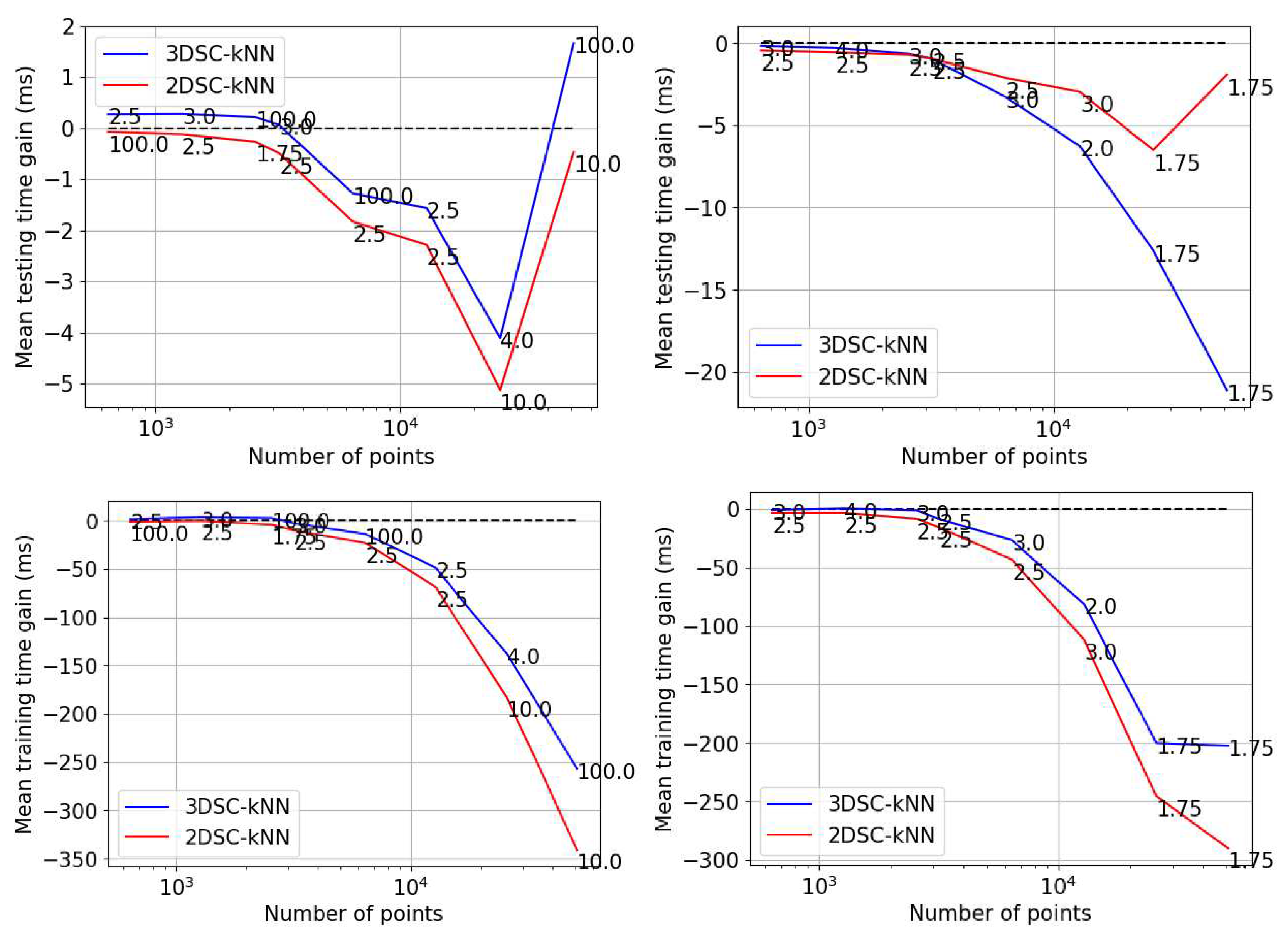

- Execution time gain: This gain is calculated as (the execution time of 2DEC-kNN k-means clustering algorithm - the execution time of candidate algorithm).

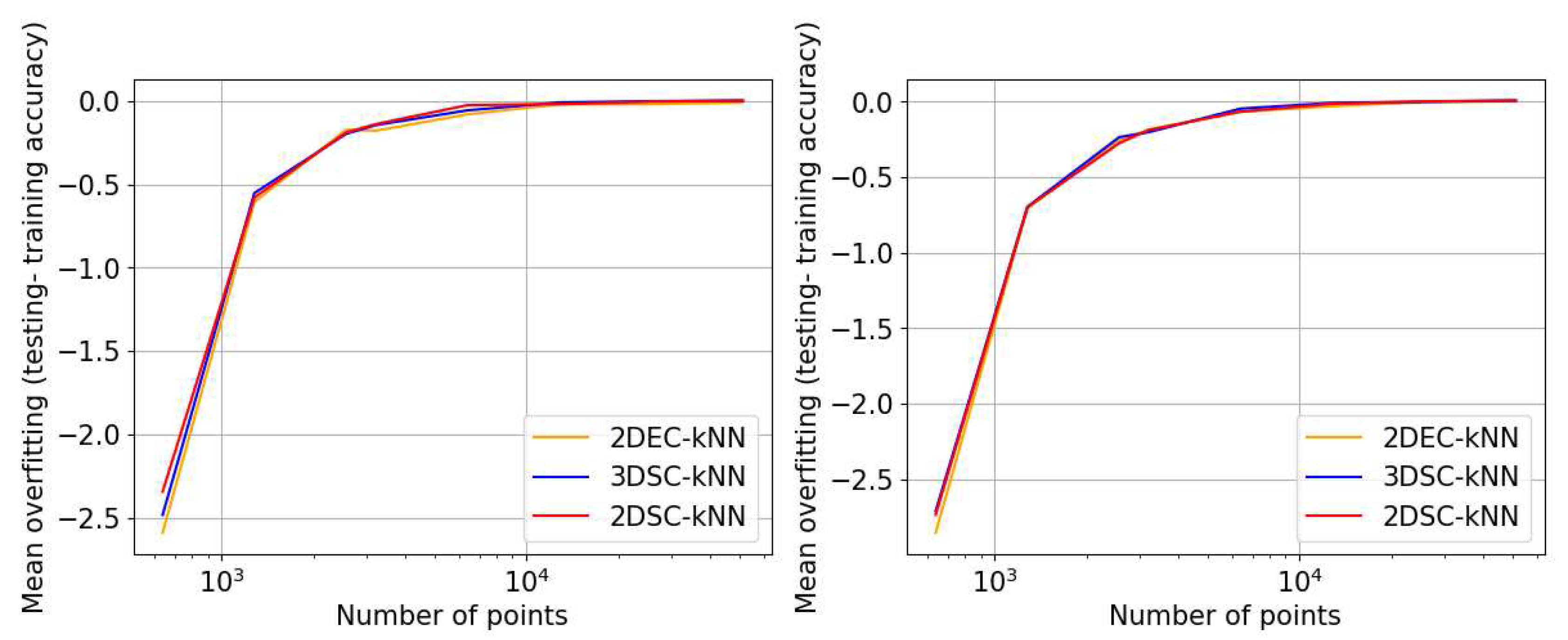

- Overfitting Parameter: (accuracy in testing−accuracy in training).

- The Overfitting Test: The dataset is divided into a `training’ and a `testing’ set, to characterise the clustering and classification performance of the algorithms.

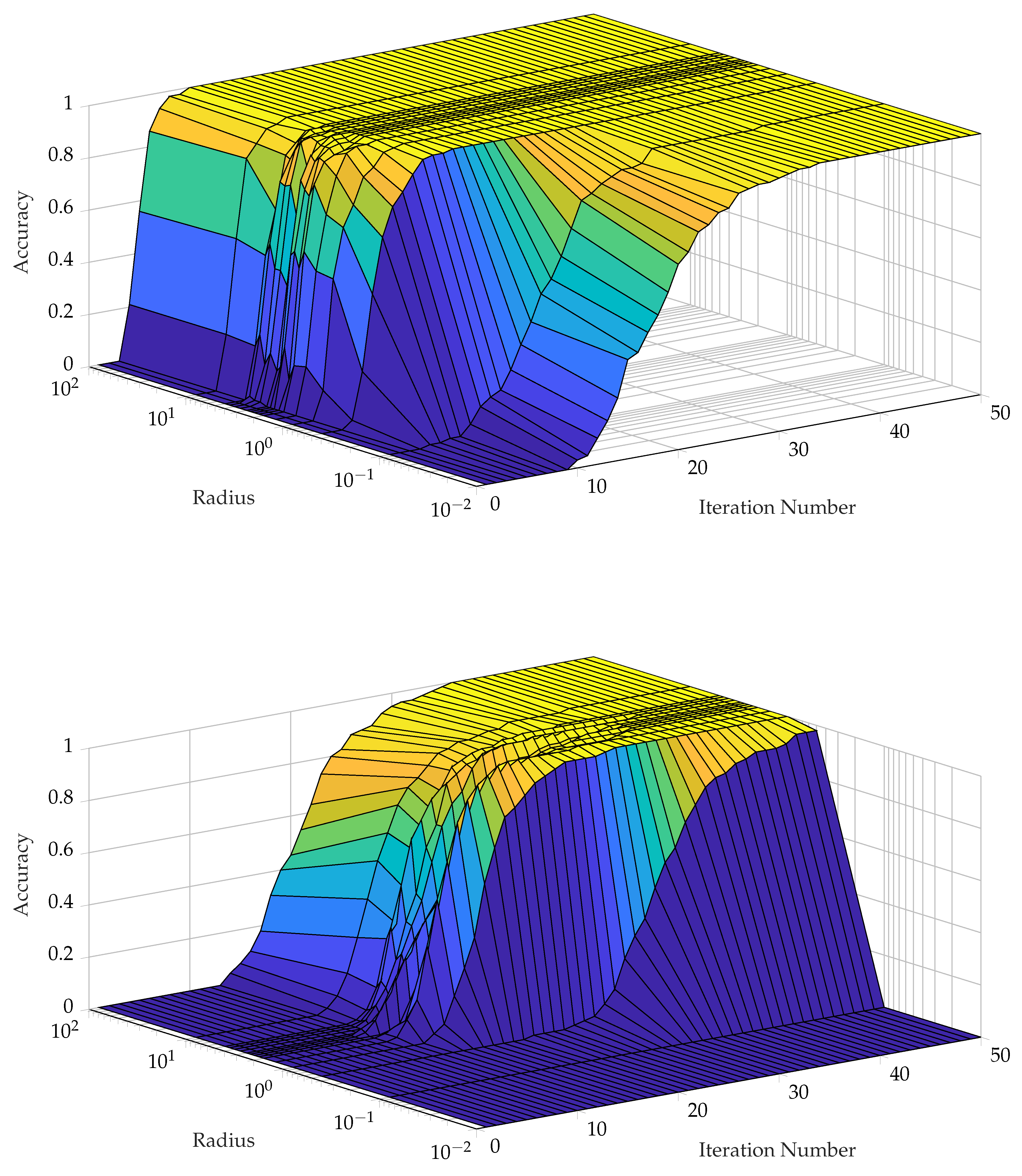

- The Stopping Criterion Test: The iterations and other performance parameters are varied, to test whether and what kind of stopping criterion is required.

5.1. Experiment 1: Overfitting

- It exhaustively covers all the parameters that can be used to quantify the performance of the algorithms. We were able to observe very important trends in the performance parameters with respect to the choice of radius and the effect of the number of points (affecting the choice of when one should trigger the clustering process on the collected received points).

- It avoids the commonly known problem of overfitting. Though this approach is not usually used in testing the kNN due to its iterative nature, we felt that from a machine learning perspective, it is useful to know how well the algorithms perform in a classification setting as well.

- Another reason that justifies the training and testing approach (clustering and classification) is the nature of the real-world application setup. When transmitting QAM data through optical-fibre, the receiver receives only one point at a time and has to classify the received point to a given cluster in real-time using the current centroid values. Once a number of data points have accumulated, the kNN algorithm can be run to update the centroid values; after the update, the receiver will once again perform classification until some number of points has been accumulated. Hence, we can see that in this scenario, the clustering and the classification performance of the chosen method become important.

5.1.1. Results

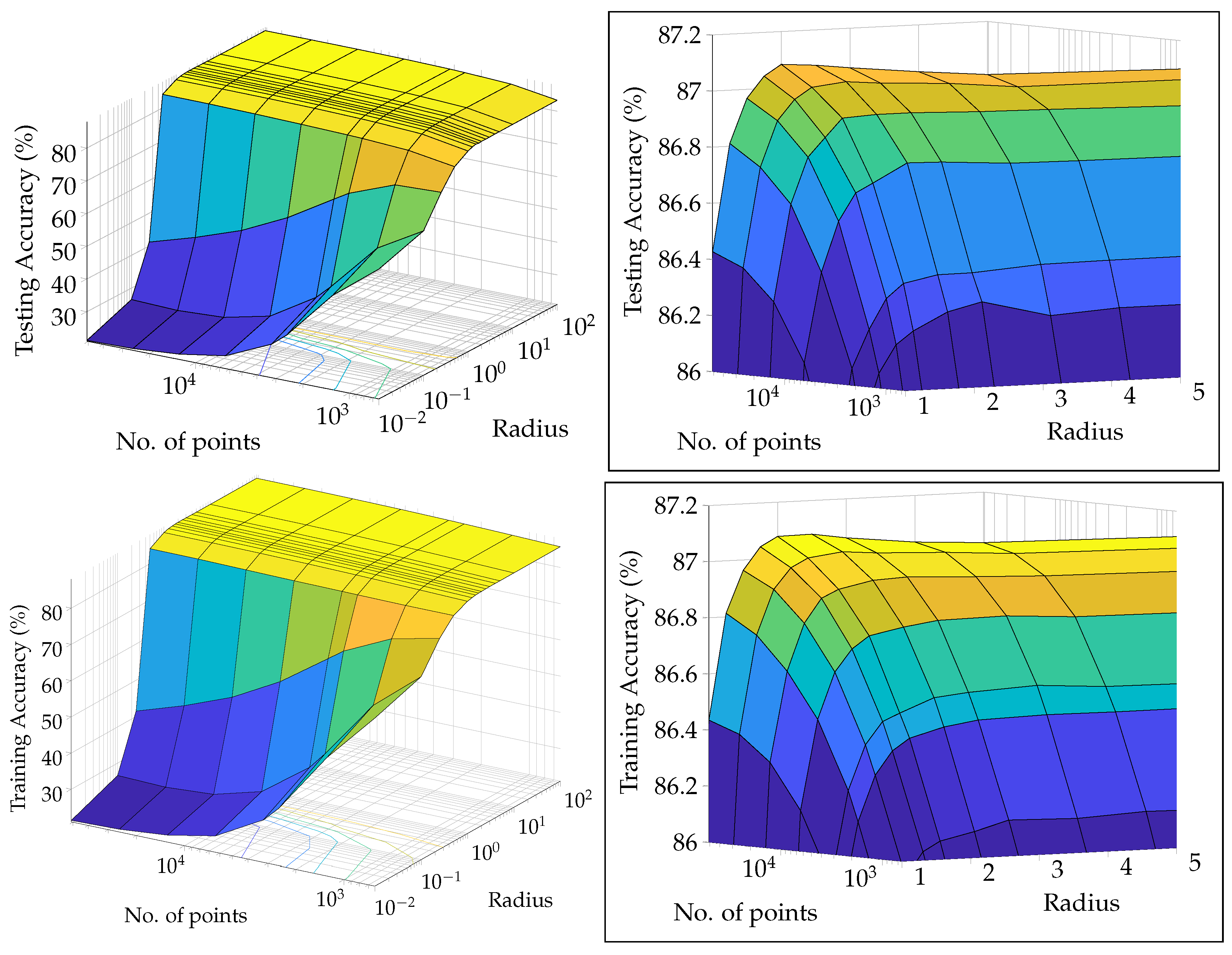

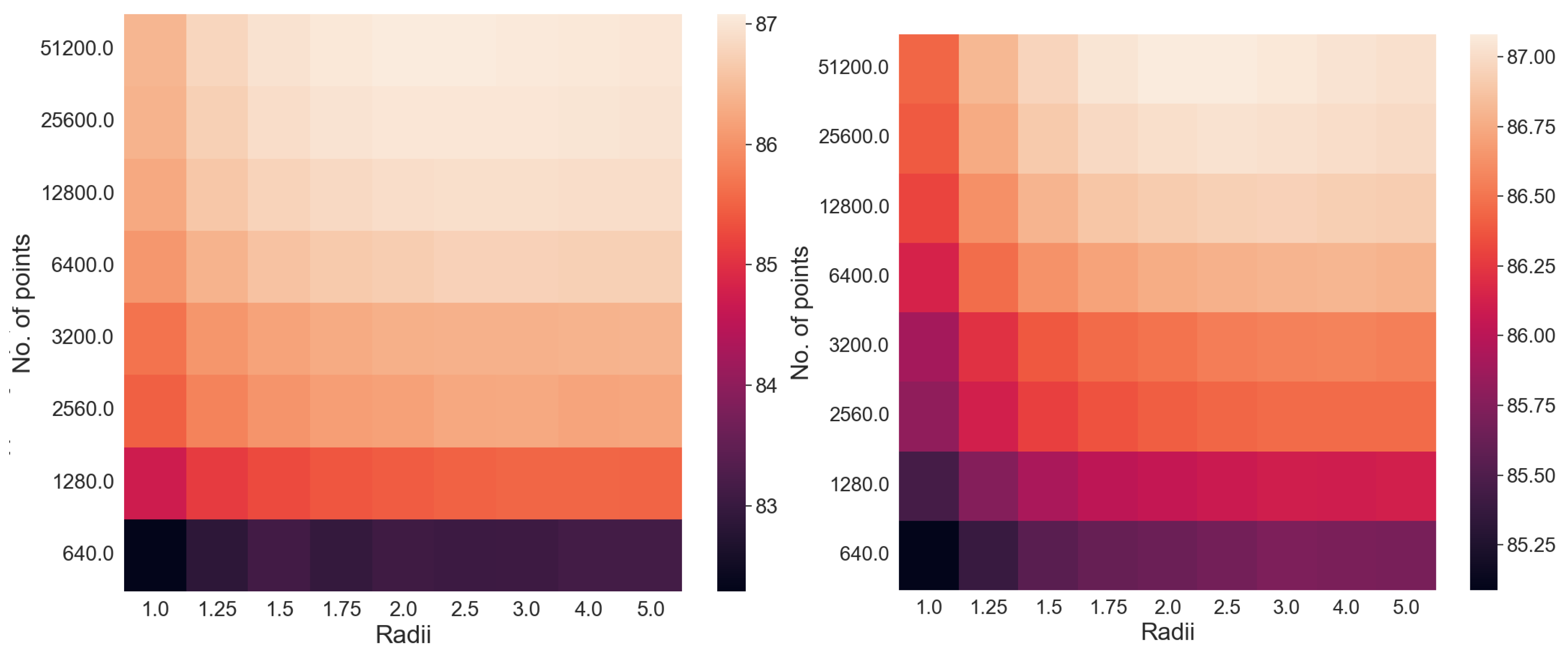

Accuracy Performance

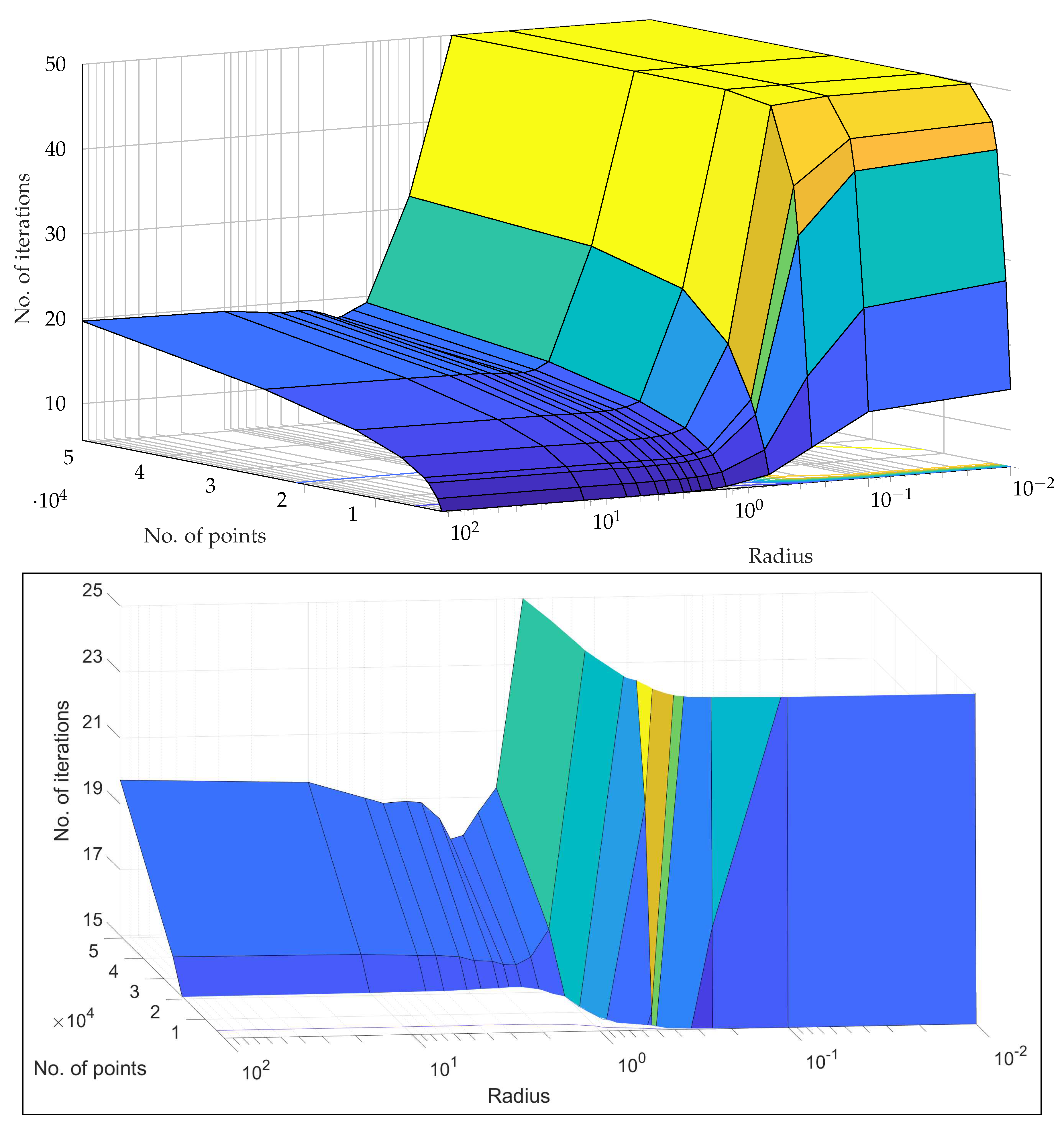

Iteration Performance

Time Performance

Overfitting Performance

5.1.2. Discussion and Analysis

5.2. Experiment 2: Stopping criterion

5.2.1. Results

Characterisation of the 2DSC-kNN algorithm

Comparison with 2DEC-kNN and 3DS-kNN K-Means Clustering

5.2.2. Discussion and Analysis

5.3. Overall Observations

Overall Observations from Experiment 1

- The ideal projection radius is greater than 1 and between 2 and 5. At this ideal radius, one achieves maximum testing and training accuracy, and minimum iterations.

- In general, the accuracy performance is the same for 3DSC-kNN and 2DSC-kNN algorithms - this shows a significant contribution of the ISP to the advantage as opposed to `quantumness’. This is a significant distinction, not made by any previous work.

- 2DSC-kNN and 3DSC-kNN algorithms lead to an increase in the accuracy performance in general, with the increase most pronounced for the 2.7dBm dataset.

- The 2DSC-kNN algorithm and 3DSC-kNN algorithm give more iteration performance gain (fewer iterations required than 2DEC-kNN) for high noise datasets and for a large number of points.

- Generally, increasing the number of points favours the 2DSC-kNN and 3DSC-kNN algorithms, with the caveat that a good radius must be carefully chosen.

Overall Observations from Experiment 2

- These results further stress the importance of choosing a good radius (2 to 5 in this application) and a better stopping criterion. The natural endpoint is not suitable.

- The results justify the fact that the developed 2DSC-kNN algorithm has significant advantages over 2DEC-kNN k-means clustering and 3DSC-kNN clustering.

- The 2DSC-kNN algorithm performs nearly the same as the 3DSC-kNN algorithm in terms of accuracy, but for iterations to achieve this max accuracy, the 2DSC-kNN algorithm is better (especially for high noise and a high number of points).

- The developed 2DSC-kNN algorithm and 3DSC-kNN algorithm are better than the 2DEC-kNN algorithm in general - in terms of accuracy and iterations to reach that maximum accuracy.

- The supremacy of the 2DSC-kNN algorithm over the 2DEC-kNN algorithm implies that a fully-quantum SQ-kNN algorithm would have an advantage over the fully-quantum k-means algorithm of [2].

6. Conclusion and Further work

6.1. Future Work

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Analog-to-digital converter |

|---|---|

| CD | Chromatic dispersion |

| CFO | Carrier frequency offset |

| CPE | Carrier phase estimation |

| DAC | Digital-to-analog converter |

| DP | Dual Polarisation |

| ECL | External cavity laser |

| FEC | Forward error correction |

| GHz | Gigahertz |

| GBd | Gigabauds |

| GSa/s | samples per second |

| DSP | Digital signal processing |

| ISP | Inverse stereographic projection |

| MIMO | Multiple input multiple output |

| M-QAM | M-ary Quadrature Amplitude Modulation |

| QML | Quantum Machine Learning |

| QRAM | Quantum Random Access Memory |

| TR | Timing recovery |

| SQ access | Sample and query access |

| kNN | k-Nearest-Neighbour clustering algorithm(3) |

| FF-QRAM | Flip flop QRAM |

| NISQ | Near-intermediate scale quantum |

| Dataspace | |

| D | 2-dimensional dataset |

| set of all M centroids | |

| Cluster associated to a centroid | |

| Dissimilarity (measure function) | |

| Euclidean dissimilarity | |

| Cosine dissimilarity | |

| ISP into a sphere of radius r | |

| n-sphere of radius r | |

| Hilbert space of one qubit | |

| nDEC-kNN | n-dimensional Euclidean Classical kNN (Definition 4) |

| SQ-kNN | Stereographic Quantum kNN (Definition 10) |

| 2DSC-kNN | 2D Stereographic Classical kNN (Definition 12) |

| 3DSC-kNN | 3D Stereographic Classical kNN (Definition 6) |

Appendix A. QAM and Data Visualisation

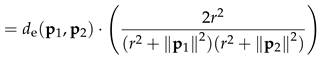

Appendix A.1. Description of 64-QAM Data

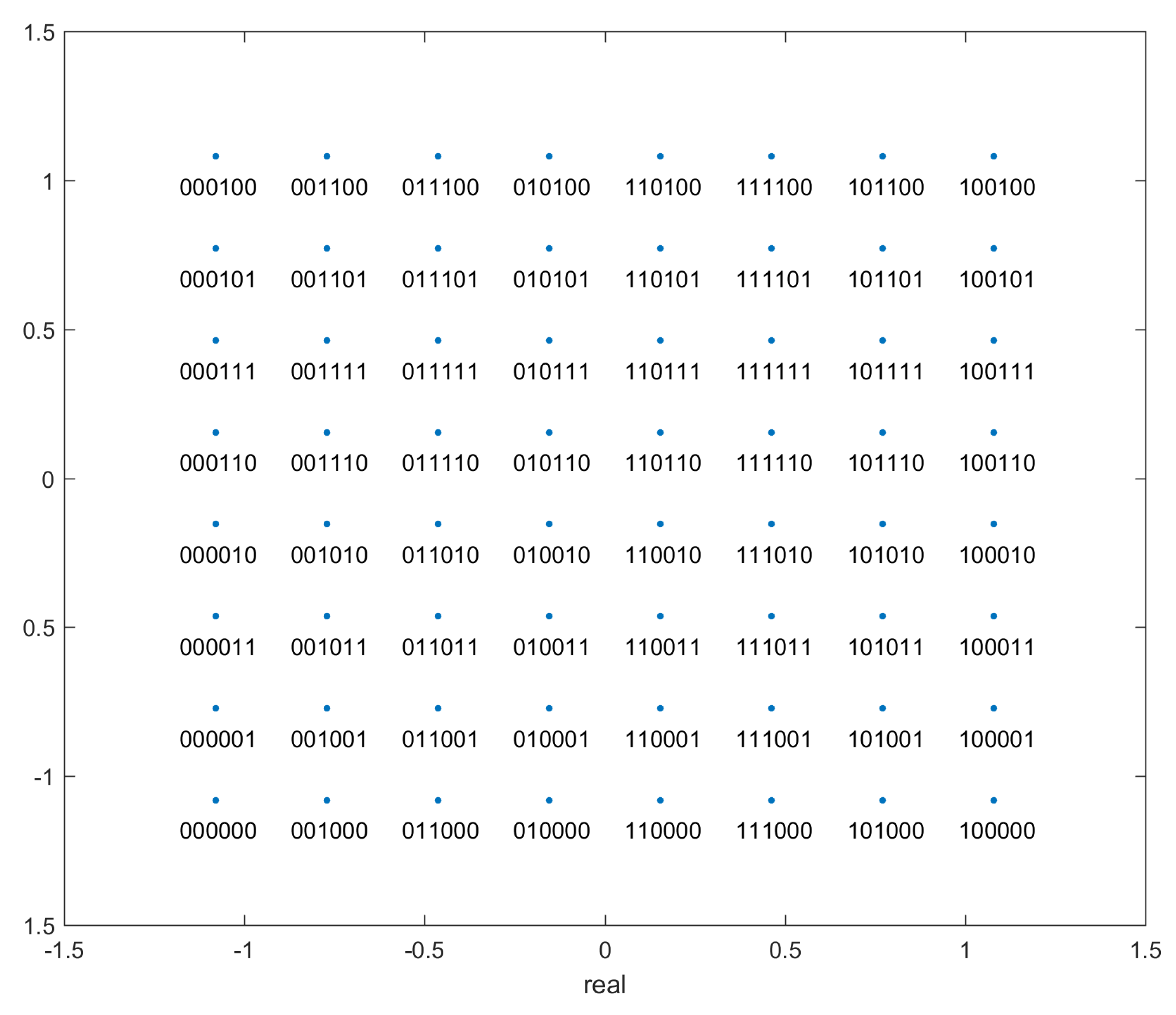

- `alphabet’: The initial analog values at which the data was transmitted, in the form of complex numbers, i.e. for an entry (), the transmitted signal was of the form . Since the transmission protocol is 64-QAM, there are 64 values in this variable. The transmission alphabet is the same irrespective of the non-linear distortions.

- `rxsignal’: The received analog values of the signal by the receiver. This data is in the form of a matrix. Each datapoint was transmitted five times to the receiver, and so each row contains the values detected by the receiver during the different instances of the transmission of the same datapoint. The values in different rows represent unique datapoint values detected by the receiver.

- `bits’: This is the true label for the transmitted points. This data is in the form of a matrix. Since the protocol is 64-QAM, each analog point represents six bits. These six bits are the entries in each column, and each value in a different row represents the correct label for a unique transmitted datapoint value. The first three bits encode the column, and the last three bits encode the row - see Figure A3.

Appendix B. Data Embedding

| Embedding | Encoding | Num. qubits required | Gate Depth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis | per data point | ||

| Angle | |||

| Amplitude | gates | ||

| QRAM | queries |

Appendix B.1. Angle Embedding

Appendix C. Stereographic Projection

Appendix C.1. ISP for General Radius

- Azimuthal angle of the original point and the projected point must be the same, i.e. the original point, projected point, and the top of the sphere (the point from which all projections are drawn) lie on the same plane, which is perpendicular to the 2D plane.

- The projected point lies on the sphere.

- The triangle with vertices , and is similar to the triangle with vertices , and :

Appendix C.2. Equivalence of Displacement and Scaling

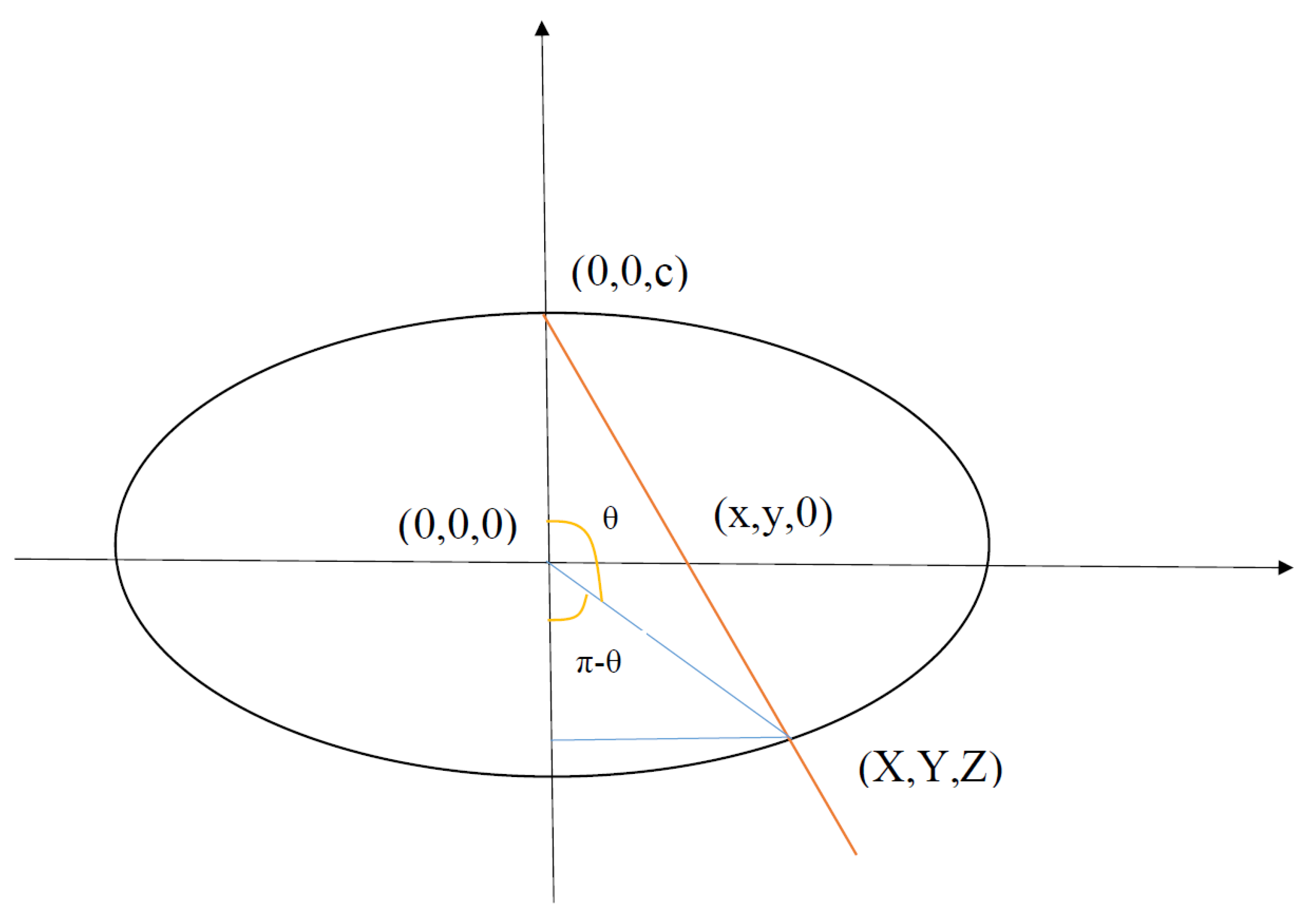

Appendix D. Ellipsoidal Embedding

- Azimuthal angle -

- The projected point lies on the ellipsoid -

- The triangle with vertices , and is similar to the triangle with vertices , and -

Appendix E. Distance Estimation Using Stereographic Embedding

Appendix F. Rotation Gates and the UGate

References

- Harrow, A.W.; Hassidim, A.; Lloyd, S. Quantum Algorithm for Linear Systems of Equations. Physical Review Letters 2009, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, S.; Mohseni, M.; Rebentrost, P. Quantum algorithms for supervised and unsupervised machine learning. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1307.0411. [Google Scholar]

- Preskill, J. Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2018, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E. Quantum Principal Component Analysis Only Achieves an Exponential Speedup Because of Its State Preparation Assumptions. Physical Review Letters 2021, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arute, F.; Arya, K.; Babbush, R.; Bacon, D.; Bardin, J.; Barends, R.; Biswas, R.; Boixo, S.; Brandao, F.; Buell, D.; et al. Quantum Supremacy using a Programmable Superconducting Processor. Nature 2019, 574, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuld, M.; Petruccione, F. Supervised Learning with Quantum Computers; Quantum Science and Technology, Springer International Publishing, 2018.

- M. Schuld, I. Sinayskiy, F.P. An introduction to quantum machine learning. arXiv:1409.3097 [quant-ph] 2014.

- Kerenidis, I.; Prakash, A. Quantum Recommendation Systems. In Proceedings of the 8th Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (ITCS 2017); Papadimitriou, C.H., Ed.; Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik: Dagstuhl, Germany, 2017; Vol. 67, Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics (LIPIcs), pp. 49:1–49:21. [CrossRef]

- Kerenidis, I.; Landman, J.; Luongo, A.; Prakash, A. q-means: A quantum algorithm for unsupervised machine learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.03584. [Google Scholar]

- Modi, A.; Jasso, A.V.; Ferrara, R.; Deppe, C.; Noetzel, J.; Fung, F.; Schaedler, M. Testing of Hybrid Quantum-Classical K-Means for Nonlinear Noise Mitigation. arXiv [arXiv:quant-ph/2308.03540]. 2023, arXiv:2308.03540. [Google Scholar]

- Pakala, L.; Schmauss, B. Non-linear mitigation using carrier phase estimation and k-means clustering. In Proceedings of the Photonic Networks; 16. ITG Symposium. VDE, 2015, pp. 1–5.

- Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Gao, M.; Shen, G. K-means-clustering-based fiber nonlinearity equalization techniques for 64-QAM coherent optical communication system. Optics express 2017, 25, 27570–27580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E. Quantum Principal Component Analysis Only Achieves an Exponential Speedup Because of Its State Preparation Assumptions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 060503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambetta, J. IBM’s roadmap for scaling quantum technology.

- Diedolo, F.; Böcherer, G.; Schädler, M.; Calabró, S. Nonlinear Equalization for Optical Communications Based on Entropy-Regularized Mean Square Error. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Optical Communication (ECOC) 2022. Optica Publishing Group; 2022; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Martyn, J.M.; Rossi, Z.M.; Tan, A.K.; Chuang, I.L. A grand unification of quantum algorithms. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.02859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopczyk, D. Quantum machine learning for data scientists. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.10068. [Google Scholar]

- Esma Aimeur, G.B.; Gambs, S. Quantum clustering algorithms. ICML ’07: Proceedings of the 24th international conference on Machine learning June 2007 2007, p. 1–8.

- Cruise, J.R.; Gillespie, N.I.; Reid, B. Practical Quantum Computing: The value of local computation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.08513. [Google Scholar]

- Johri, S.; Debnath, S.; Mocherla, A.; Singh, A.; Prakash, A.; Kim, J.; Kerenidis, I. Nearest centroid classification on a trapped ion quantum computer. npj Quantum Information 2021, 7, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Awan, A.J.; Vall-Llosera, G. K-Means Clustering on Noisy Intermediate Scale Quantum Computers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.12183. [Google Scholar]

- Cortese, J.A.; Braje, T.M. Loading classical data into a quantum computer. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01958. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannetti, V.; Lloyd, S.; Maccone, L. Quantum Random Access Memory. Physical Review Letters 2008, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harry Buhrman, Richard Cleve, J.W.; de Wolf, R. Quantum fingerprinting. arXiv:quant-ph/0102001 2001.

- Ripper, P.; Amaral, G.; Temporão, G. Swap Test-based characterization of decoherence in universal quantum computers. Quantum Information Processing 2023, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulds, S.; Kendon, V.; Spiller, T. The controlled SWAP test for determining quantum entanglement. Quantum Science and Technology 2021, 6, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E. A Quantum-Inspired Classical Algorithm for Recommendation Systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 51st Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; STOC 2019, p. 217–228, [arXiv:cs.IR/1807.04271]. [CrossRef]

- Chia, N.H.; Lin, H.H.; Wang, C. Quantum-inspired sublinear classical algorithms for solving low-rank linear systems. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.04852. [Google Scholar]

- Gilyén, A.; Lloyd, S.; Tang, E. Quantum-inspired low-rank stochastic regression with logarithmic dependence on the dimension. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.04909. [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola, J.M.; Delgado, A.; Bardhan, B.R.; Lloyd, S. Quantum-inspired algorithms in practice. Quantum 2020, 4, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, N.H.; Gilyén, A.; Li, T.; Lin, H.H.; Tang, E.; Wang, C. Sampling-based sublinear low-rank matrix arithmetic framework for dequantizing Quantum machine learning. Proceedings of the 52nd Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrazola, J.M.; Delgado, A.; Bardhan, B.R.; Lloyd, S. Quantum-inspired algorithms in practice. Quantum 2020, 4, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, N.H.; Gilyén, A.; Lin, H.H.; Lloyd, S.; Tang, E.; Wang, C. hia, N.H.; Gilyén, A.; Lin, H.H.; Lloyd, S.; Tang, E.; Wang, C. Quantum-Inspired Algorithms for Solving Low-Rank Linear Equation Systems with Logarithmic Dependence on the Dimension. In Proceedings of the 31st International Symposium on Algorithms and Computation (ISAAC 2020); Cao, Y.; Cheng, S.W.; Li, M., Eds.; Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik: Dagstuhl, Germany, 2020; Vol. 181, Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics (LIPIcs), pp. 47:1–47:17. [CrossRef]

- Sergioli, G.; Santucci, E.; Didaci, L.; Miszczak, J.A.; Giuntini, R. A quantum-inspired version of the nearest mean classifier. Soft Computing 2018, 22, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergioli, G.; Bosyk, G.M.; Santucci, E.; Giuntini, R. A quantum-inspired version of the classification problem. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 2017, 56, 3880–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhi, G.M.; Messikh, A. Simple quantum circuit for pattern recognition based on nearest mean classifier. International Journal on Perceptive and Cognitive Computing 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguemto, S.; Leyton-Ortega, V. Re-QGAN: an optimized adversarial quantum circuit learning framework, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Eybpoosh, K.; Rezghi, M.; Heydari, A. Applying inverse stereographic projection to manifold learning and clustering. Applied Intelligence 2022, 52, 4443–4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggiali, A.; Berti, A.; Bernasconi, A.; Del Corso, G.; Guidotti, R. Quantum Clustering with k-Means: a Hybrid Approach. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.06691. [Google Scholar]

- de Veras, T.M.L.; de Araujo, I.C.S.; Park, D.K.; da Silva, A.J. Circuit-Based Quantum Random Access Memory for Classical Data With Continuous Amplitudes. IEEE Transactions on Computers 2021, 70, 2125–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, K.; Feinerer, I.; Kober, M.; Buchta, C. Spherical k-Means Clustering. Journal of Statistical Software 2012, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, X.; Ding, X.; Shan, Z. An Enhanced Quantum K-Nearest Neighbor Classification Algorithm Based on Polar Distance. Entropy 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Lloyd, S. Least squares quantization in PCM. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1982, 28, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, E.; Lang, A.; Feher, G. Accelerating Spherical k-Means. In Proceedings of the Similarity Search and Applications; Reyes, N.; Connor, R.; Kriege, N.; Kazempour, D.; Bartolini, I.; Schubert, E.; Chen, J.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 217–231.

- Ahlfors, L.V. Complex Analysis, 2 ed.; McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1966.

- LaRose, R.; Coyle, B. Robust data encodings for quantum classifiers. Physical Review A 2020, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigold, M.; Barzen, J.; Leymann, F.; Salm, M. Expanding Data Encoding Patterns For Quantum Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th International Conference on Software Architecture Companion (ICSA-C); 2021; pp. 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanizza, M.; Rosati, M.; Skotiniotis, M.; Calsamiglia, J.; Giovannetti, V. Beyond the Swap Test: Optimal Estimation of Quantum State Overlap. Physical Review Letters 2020, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulds, S.; Kendon, V.; Spiller, T. The controlled SWAP test for determining quantum entanglement. Quantum Science and Technology 2021, 6, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsystems, B. Digital modulation efficiencies.

- Jr., L.E.F. Electronics Explained: Fundamentals for Engineers, Technicians, and Makers; Newnes, 2018.

- Plesch, M.; Brukner, Č. Quantum-state preparation with universal gate decompositions. Physical Review A 2011, 83, 032302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quantum Computing Patterns. Available online: https://quantumcomputingpatterns.org/ (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Roy, B. All about Data Encoding for Quantum Machine Learning. 2021. Available online: https://medium.datadriveninvestor.com/all-about-data-encoding-for-quantum-machine-learning-2a7344b1dfef.

| 1 | This might not be true for other definitions of quantum dissimilarity, as in Section 3.4 where we redefine it to include embedding into mixed states. |

| 2 | This is obtained as in Figure 2 where the Hadamard is replaced with the Fourier transform and the CNOT with . If we have multiple qubits instead of qudits, then the solution is even simpler: perform a qubit Bell measurement with each pair of qubits. This is because the tensor product of maximally entangled states is still a maximally entangled state. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).