Submitted:

30 June 2023

Posted:

04 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

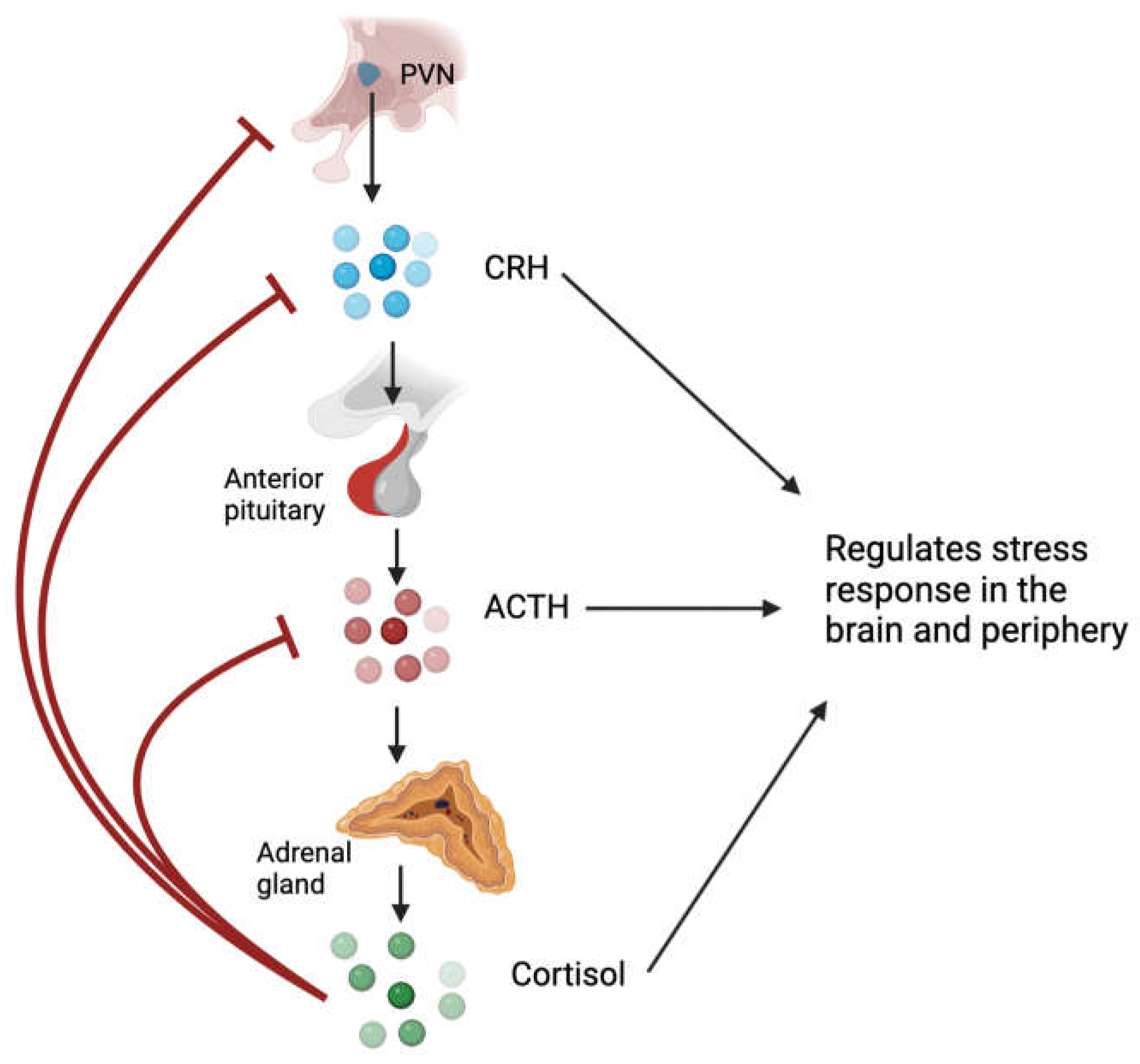

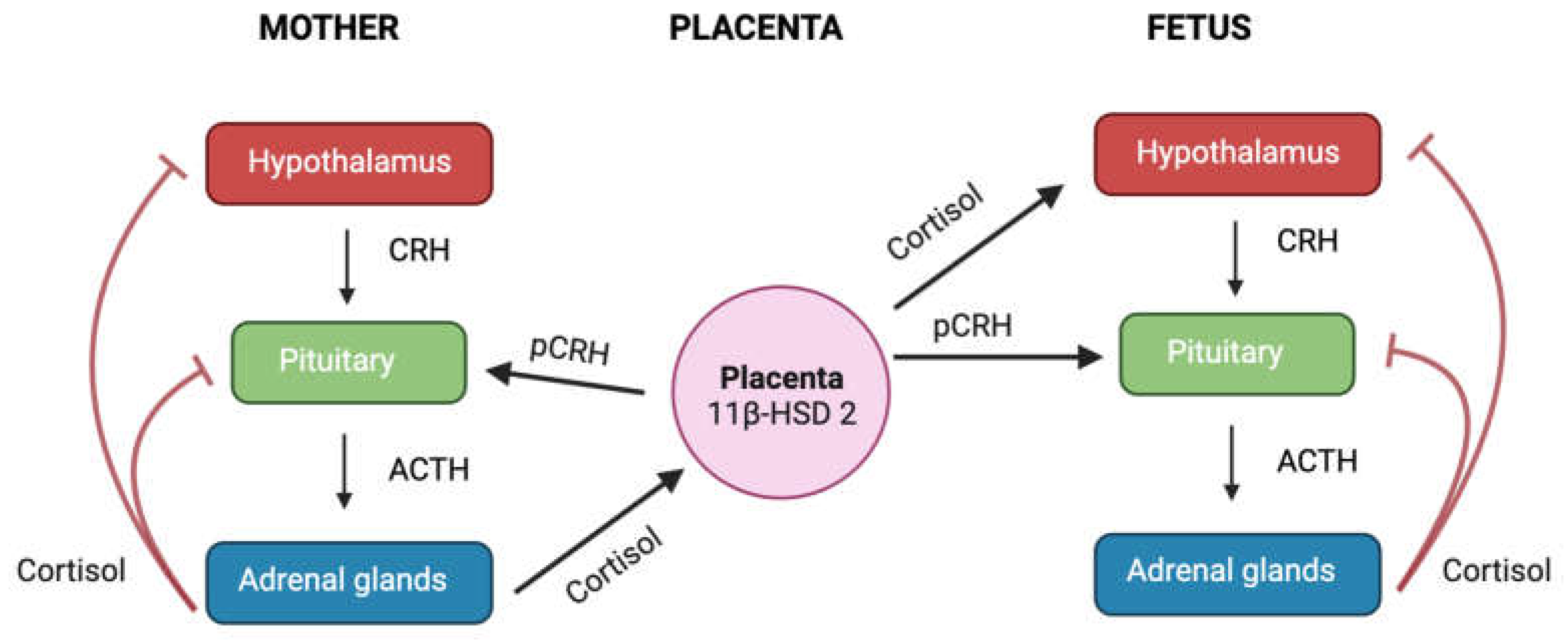

1. Glucocorticoids and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

2. Immunological and therapeutical function of glucocorticoids

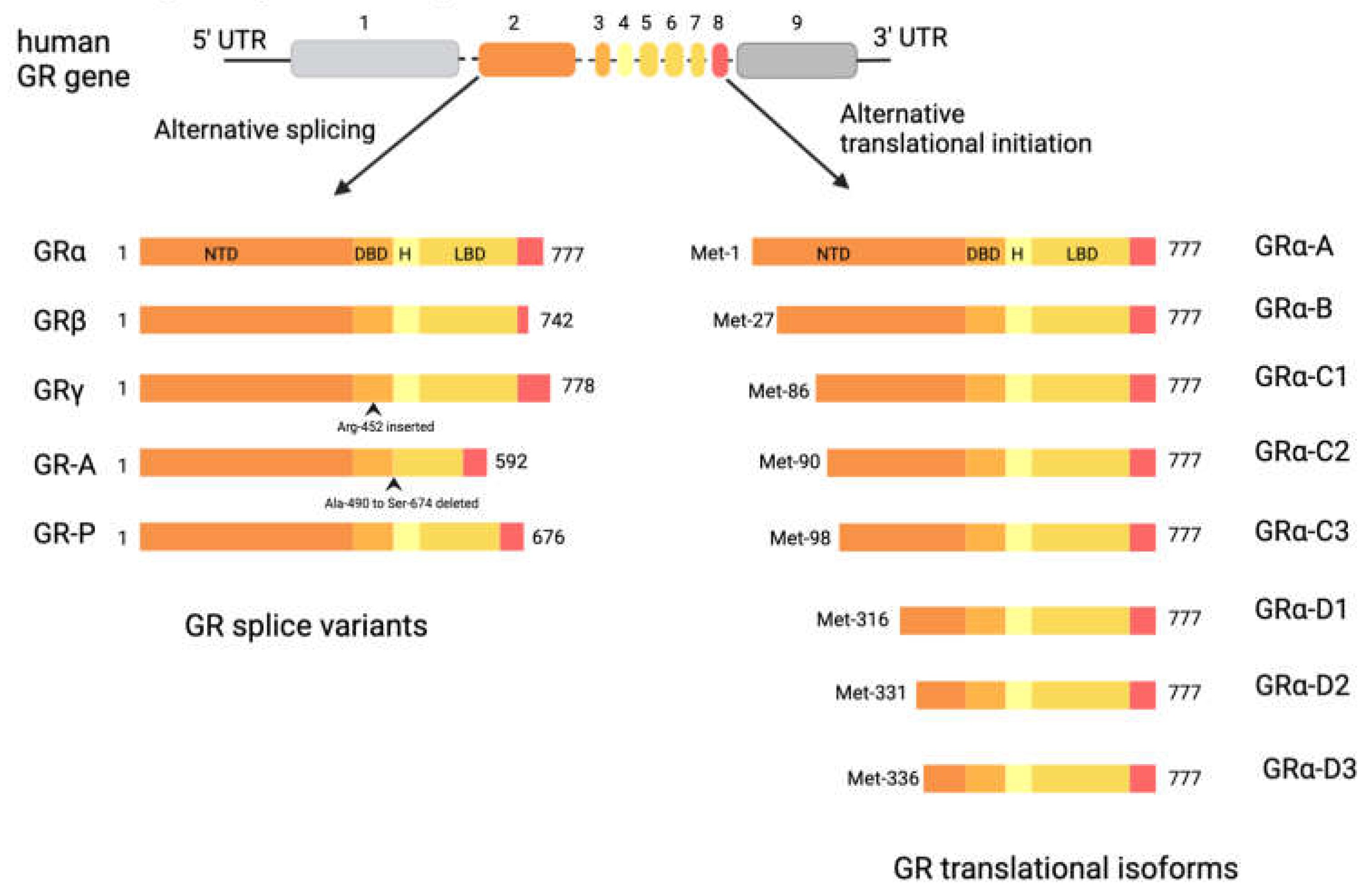

3. Glucocorticoid Receptor

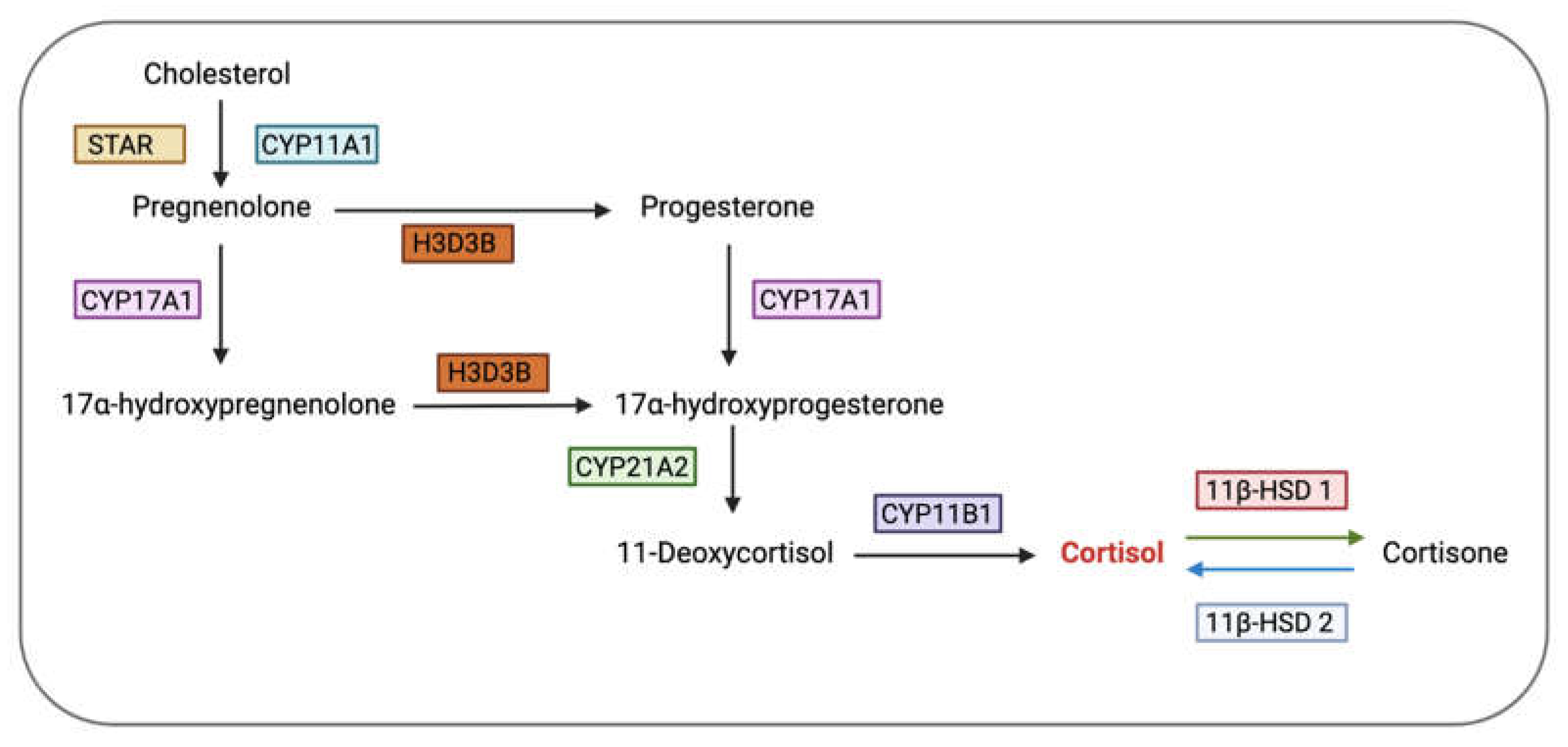

4. Glucocorticoid Bioavailability

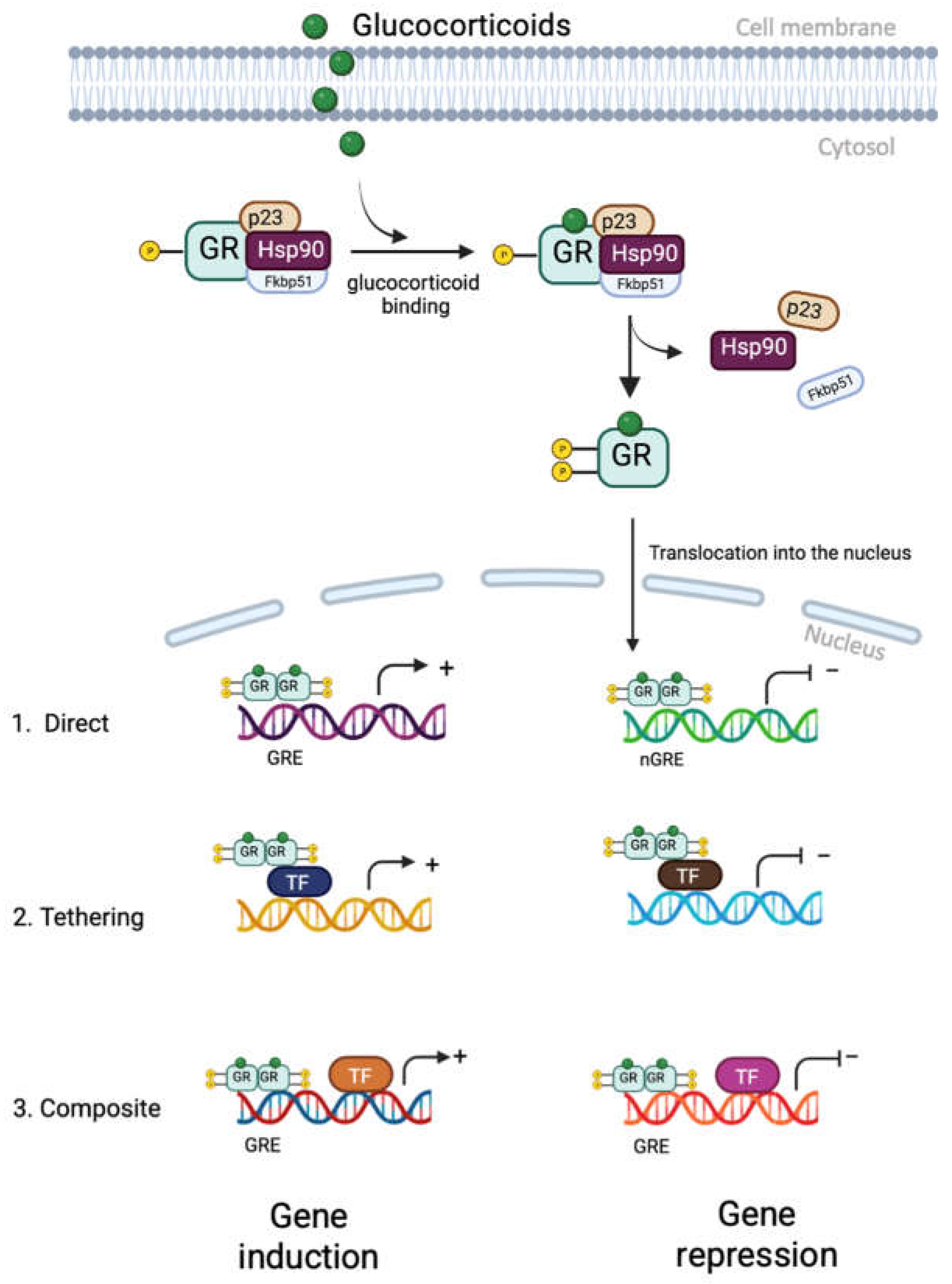

5. Glucocorticoid Receptor Signalling

6. Glucocorticoids on hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

7. Effect of glucocorticoids on reproductive organs

7.1. Ovary

7.1.1. Dual role of glucocorticoids in the ovary

7.1.2. Glucocorticoid receptor isoforms in the ovary

7.2. Uterus

7.2.1. GR isoforms in the uterus

8. Pregnancy and Parturition

8.1. Effect of excess cortisol on myometrial contractility during parturition

9. Fetus

9.1. Sex differences

9.2. Glucocorticoid receptor isoform in the placenta

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oakley RH, Cidlowski JA. Cellular processing of the glucocorticoid receptor gene and protein: new mechanisms for generating tissue-specific actions of glucocorticoids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011, 286, 3177–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans S, Souffriau J, Libert C. A general introduction to glucocorticoid biology. Frontiers in immunology. 2019, 10, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith SM, Vale WW. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience 2022.

- Aguilera, G. Regulation of pituitary ACTH secretion during chronic stress. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 1994, 15, 321–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawchenko, P. Evidence for a local site of action for glucocorticoids in inhibiting CRF and vasopressin expression in the paraventricular nucleus. Brain research. 1987, 403, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munck A, Guyre PM, Holbrook NJ. Physiological functions of glucocorticoids in stress and their relation to pharmacological actions. Endocrine reviews. 1984, 5, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, Krishnamoorthy P, Mandelcorn ED, Leigh R, et al. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology. 2013, 9, 1–25.

- Busillo JM, Cidlowski JA. The five Rs of glucocorticoid action during inflammation: ready, reinforce, repress, resolve, and restore. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013, 24, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Topete D, Cidlowski JA. One hormone, two actions: anti-and pro-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2015, 22, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinenov Y, Rogatsky I. Glucocorticoids and the innate immune system: crosstalk with the toll-like receptor signaling network. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2007, 275, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besedovsky H, Del Rey A, Klusman I, Furukawa H, Arditi GM, Kabiersch A. Cytokines as modulators of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 1991, 40, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho AE, Chapman KE. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2011, 335, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galati A, Brown ES, Bove R, Vaidya A, Gelfand J. Glucocorticoids for therapeutic immunosuppression: Clinical pearls for the practicing neurologist. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2021, 430, 120004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAUCI AS, DALE DC, BALOW JE. Glucocorticosteroid therapy: mechanisms of action and clinical considerations. Annals of internal medicine. 1976, 84, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settipane GA, Pudupakkam R, McGowan JH. Corticosteroid effect on immunoglobulins. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1978, 62, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides NC, Galata Z, Kino T, Chrousos GP, Charmandari E. The human glucocorticoid receptor: molecular basis of biologic function. Steroids. 2010, 75, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain DW, Cidlowski JA. Specificity and sensitivity of glucocorticoid signaling in health and disease. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2015, 29, 545–556. [Google Scholar]

- Lu NZ, Wardell SE, Burnstein KL, Defranco D, Fuller PJ, Giguere V, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LXV. The pharmacology and classification of the nuclear receptor superfamily: glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid, progesterone, and androgen receptors. Pharmacological reviews. 2006, 58, 782–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevyver S, Dejager L, Libert C. Comprehensive overview of the structure and regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor. Endocrine reviews. 2014, 35, 671–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger CM, Bamberger A-M, De Castro M, Chrousos GP. Glucocorticoid receptor beta, a potential endogenous inhibitor of glucocorticoid action in humans. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1995, 95, 2435–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moalli PA, Pillay S, Krett NL, Rosen ST. Alternatively spliced glucocorticoid receptor messenger RNAs in glucocorticoid-resistant human multiple myeloma cells. Cancer research. 1993, 53, 3877–3879. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg SM, Weinberger C, Ong ES, Cerelli G, Oro A, Lebo R, et al. Primary structure and expression of a functional human glucocorticoid receptor cDNA. Nature. 1985, 318, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakley RH, Sar M, Cidlowski JA. The Human Glucocorticoid Receptor β Isoform: Expression, biochemical properties, and putative function (∗). Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996, 271, 9550–9559.

- Kino T, Manoli I, Kelkar S, Wang Y, Su YA, Chrousos GP. Glucocorticoid receptor (GR) β has intrinsic, GRα-independent transcriptional activity. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2009, 381, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He B, Cruz-Topete D, Oakley RH, Xiao X, Cidlowski JA. Human glucocorticoid receptor β regulates gluconeogenesis and inflammation in mouse liver. Molecular and cellular biology. 2016, 36, 714–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivers C, Levy A, Hancock J, Lightman S, Norman M. Insertion of an amino acid in the DNA-binding domain of the glucocorticoid receptor as a result of alternative splicing. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1999, 84, 4283–4286. [Google Scholar]

- Ray DW, Davis JR, White A, Clark AJ. Glucocorticoid receptor structure and function in glucocorticoid-resistant small cell lung carcinoma cells. Cancer research. 1996, 56, 3276–3280. [Google Scholar]

- Meijsing SH, Pufall MA, So AY, Bates DL, Chen L, Yamamoto KR. DNA binding site sequence directs glucocorticoid receptor structure and activity. Science. 2009, 324, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Chollier M, Watson LC, Cooper SB, Pufall MA, Liu JS, Borzym K, et al. A naturally occuring insertion of a single amino acid rewires transcriptional regulation by glucocorticoid receptor isoforms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013, 110, 17826–17831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan DJ, Poolman TM, Williamson AJ, Wang Z, Clark NR, Ma’ayan A, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor isoforms direct distinct mitochondrial programs to regulate ATP production. Scientific reports. 2016, 6, 26419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitan D, DeBold CR, Turney MK, Zhou P, Orth DN, Kovacs WJ. Glucocorticoid receptor structure and function in an adrenocorticotropin-secreting small cell lung cancer. Molecular endocrinology. 1995, 9, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar]

- Lu NZ, Cidlowski JA. Translational regulatory mechanisms generate N-terminal glucocorticoid receptor isoforms with unique transcriptional target genes. Molecular cell. 2005, 18, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramamoorthy S, Cidlowski JA. Corticosteroids: mechanisms of action in health and disease. Rheumatic Disease Clinics. 2016, 42, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, GL. Plasma steroid-binding proteins: primary gatekeepers of steroid hormone action. The Journal of endocrinology. 2016, 230, R13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt WB, Toft DO. Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocrine reviews. 1997, 18, 306–360. [Google Scholar]

- Surjit M, Ganti KP, Mukherji A, Ye T, Hua G, Metzger D, et al. Widespread negative response elements mediate direct repression by agonist-liganded glucocorticoid receptor. Cell. 2011, 145, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogatsky I, Ivashkiv L. Glucocorticoid modulation of cytokine signaling. Tissue antigens. 2006, 68, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaleon M, Steane SE, McMahon K, Cuffe JS, Moritz KM. Placental O-GlcNAc-transferase expression and interactions with the glucocorticoid receptor are sex specific and regulated by maternal corticosterone exposure in mice. Scientific Reports. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Groeneweg FL, Karst H, de Kloet ER, Joëls M. Mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors at the neuronal membrane, regulators of nongenomic corticosteroid signalling. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2012, 350, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe RA, Witchell SF, DeFranco DB. Cooperativity and complementarity: synergies in non-classical and classical glucocorticoid signaling. Cell Cycle. 2012, 11, 2819–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagklis T, Ravanos K, Makedou K, Kourtis A, Rousso D. Common features and differences of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis in male and female. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2015, 31, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib SD, Wierman ME, Shupnik MA, Chin WW. Molecular biology of the pituitary gonadotropins. Endocrine reviews. 1990, 11, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards JS, Pangas SA. The ovary: basic biology and clinical implications. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010, 120, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whirledge S, Cidlowski JA. A role for glucocorticoids in stress-impaired reproduction: beyond the hypothalamus and pituitary. Endocrinology. 2013, 154, 4450–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraghty AC, Kaufer D. Glucocorticoid regulation of reproduction. Glucocorticoid Signaling: From Molecules to Mice to Man. 2015, 253–278.

- Whirledge S, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoids and reproduction: traffic control on the road to reproduction. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2017, 28, 399–415. [Google Scholar]

- Poisson M, Pertuiset B, Moguilewsky M, Magdelenat H, Martin P. Steroid receptors in the central nervous system. Implications in neurology. Revue neurologique. 1984, 140, 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Chandran UR, Attardi B, Friedman R, Dong KW, Roberts JL, DeFranco DB. Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated repression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone promoter activity in GT1 hypothalamic cell lines. Endocrinology. 1994, 134, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore AC, Attardi B, DeFranco DB. Glucocorticoid repression of the reproductive axis: effects on GnRH and gonadotropin subunit mRNA levels. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2006, 256, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HYDE CL, CHILDS MORIARTY G, WAHL LM, NAOR Z, CATT KJ. Preparation of gonadotroph-enriched cell populations from adult rat anterior pituitary cells by centrifugal elutriation. Endocrinology. 1982, 111, 1421–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng KW, Leung PC. The expression, regulation and signal transduction pathways of the mammalian gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology. 2000, 78, 1029–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya-Núñez G, Conn PM. Transcriptional regulation of the GnRH receptor gene by glucocorticoids. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2003, 200, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilen SM, Szabo M, Strasser GA, McAndrews J, Ringstrom S, Schwartz N. Corticosterone selectively increases follicle-stimulating hormone beta-subunit messenger ribonucleic acid in primary anterior pituitary cell culture without affecting its half-life. Endocrinology. 1996, 137, 3802–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takumi K, Iijima N, Higo S, Ozawa H. Immunohistochemical analysis of the colocalization of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor and glucocorticoid receptor in kisspeptin neurons in the hypothalamus of female rats. Neuroscience letters. 2012, 531, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo E, Stephens SB, Chaing S, Munaganuru N, Kauffman AS, Breen KM. Corticosterone blocks ovarian cyclicity and the LH surge via decreased kisspeptin neuron activation in female mice. Endocrinology. 2016, 157, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubuka T, Morgan K, Pawson AJ, Osugi T, Chowdhury VS, Minakata H, et al. Identification of human GnIH homologs, RFRP-1 and RFRP-3, and the cognate receptor, GPR147 in the human hypothalamic pituitary axis. PloS one. 2009, 4, e8400. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke IJ, Bartolini D, Conductier G, Henry BA. Stress increases gonadotropin inhibitory hormone cell activity and input to GnRH cells in ewes. Endocrinology. 2016, 157, 4339–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrenkohl, LR. Prenatal stress reduces fertility and fecundity in female offspring. Science. 1979, 206, 1097–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney E, Crissman J, Liberacki A, Clements C, Breslin W. Assessment of adult and neonatal reproductive parameters in Sprague-Dawley rats exposed to propylene glycol monomethyl ether vapors for two generations. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 1999, 50, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump C, Chevins P. Prenatal stress reduces fertility of male offspring in mice, without affecting their adult testosterone levels. Hormones and behavior. 1989, 23, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rensis F, Scaramuzzi RJ. Heat stress and seasonal effects on reproduction in the dairy cow—a review. Theriogenology. 2003, 60, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid B, Tam-Dafond L, Jenni-Eiermann S, Arlettaz R, Schaub M, Jenni L. Modulation of the adrenocortical response to acute stress with respect to brood value, reproductive success and survival in the Eurasian hoopoe. Oecologia. 2013, 173, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas LD, French SS. Stress-induced tradeoffs in a free-living lizard across a variable landscape: consequences for individuals and populations. PloS one. 2012, 7, e49895. [Google Scholar]

- Akers SW, Mitchell CA. Seismic stress effects on reproductive structures of tomato, potato, and marigold. HortScience. 1985, 20, 684–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobel CJ, Goldstein A, Barrett ES. Psychosocial stress and pregnancy outcome. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2008, 51, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder EJ, De Medina PR, Huizink AC, Van den Bergh BR, Buitelaar JK, Visser GH. Prenatal maternal stress: effects on pregnancy and the (unborn) child. Early human development. 2002, 70, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beals KA, Meyer NL. Female athlete triad update. Clinics in sports medicine. 2007, 26, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stafford, DE. Altered hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis function in young female athletes: implications and recommendations for management. Treatments in Endocrinology. 2005, 4, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marilus R, Dickerman Z, Kaufman H, Varsano I, Laron Z. Addison's disease associated with precocious sexual development in a boy. Acta Pædiatrica. 1981, 70, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadik Z, Cooper M, Chen M, Stern N. Cushing's disease presenting as pubertal arrest. The Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology. 1993, 6, 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kinouchi R, Matsuzaki T, Iwasa T, Gereltsetseg G, Nakazawa H, Kunimi K, et al. Prepubertal exposure to glucocorticoid delays puberty independent of the hypothalamic Kiss1-GnRH system in female rats. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2012, 30, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killian D, Kiesling D, Wulff F, Stewart A. Effects of adrenalectomy and glucocorticoids on puberty in gilts reared in confinement. Journal of Animal Science. 1987, 64, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith JT, Waddell BJ. Increased fetal glucocorticoid exposure delays puberty onset in postnatal life. Endocrinology. 2000, 141, 2422–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politch JA, Herrenkohl LR. Prenatal ACTH and corticosterone: effects on reproduction in male mice. Physiology & behavior. 1984, 32, 135–137. [Google Scholar]

- Politch JA, Herrenkohl LR. Effects of prenatal stress on reproduction in male and female mice. Physiology & behavior. 1984, 32, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Benešová O, Pavlik A. Perinatal treatment with glucocorticoids and the risk of maldevelopment of the brain. Neuropharmacology. 1989, 28, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura T, Morohashi K-i. Gene regulation of steroidogenesis. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 1995, 53, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon H, Choi Y, Brännström M, Akin J, Curry T, Jo M. Cortisol/glucocorticoid receptor: a critical mediator of the ovulatory process and luteinization in human periovulatory follicles. Human Reproduction. 2023, 38, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin M, Simerman A, Cho M, Singh P, Briton-Jones C, Hill D, et al. 21-Hydroxylase-derived steroids in follicles of nonobese women undergoing ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization (IVF) positively correlate with lipid content of luteinized granulosa cells (LGCs) as a source of cholesterol for steroid synthesis. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014, 99, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Albiston AL, Obeyesekere VR, Smith RE, Krozowski ZS. Cloning and tissue distribution of the human 1 lβ-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 enzyme. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 1994, 105, R11–R7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benediktsson R, Yau J, Low S, Brett L, Cooke B, Edwards C, et al. 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in the rat ovary: high expression in the oocyte. Journal of Endocrinology. 1992, 135, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condon J, Ricketts M, Whorwood C, Stewart P. Ontogeny and sexual dimorphic expression of mouse type 2 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 1997, 127, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushnir MM, Naessen T, Kirilovas D, Chaika A, Nosenko J, Mogilevkina I, et al. Steroid profiles in ovarian follicular fluid from regularly menstruating women and women after ovarian stimulation. Clinical chemistry. 2009, 55, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman K, Holmes M, Seckl J. 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases: intracellular gate-keepers of tissue glucocorticoid action. Physiological reviews. 2013, 93, 1139–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetsuka M, Thomas F, Thomas M, Anderson R, Mason J, Hillier S. Differential expression of messenger ribonucleic acids encoding 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase types 1 and 2 in human granulosa cells. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1997, 82, 2006–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen L, Bøtkjær J, Østrup O, Petersen K, Andersen CY, Grøndahl M, et al. Two waves of transcriptomic changes in periovulatory human granulosa cells. Human Reproduction. 2020, 35, 1230–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fateh M, Ben-Rafael Z, Benadiva CA, Mastroianni Jr L, Flickinger GL. Cortisol levels in human follicular fluid. Fertility and sterility. 1989, 51, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nteeba J, Sanz-Fernandez MV, Rhoads RP, Baumgard LH, Ross JW, Keating AF. Heat stress alters ovarian insulin-mediated phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and steroidogenic signaling in gilt ovaries. Biology of Reproduction. 2015, 92, 148–1. [Google Scholar]

- Gosden R, Hunter R, Telfer E, Torrance C, Brown N. Physiological factors underlying the formation of ovarian follicular fluid. Reproduction. 1988, 82, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune, J. Ovarian follicular growth and development in mammals. Biology of reproduction. 1994, 50, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao Y, Chen F, Kong Q-Q, Ning S-F, Yuan H-J, Lian H-Y, et al. Stresses on female mice impair oocyte developmental potential: effects of stress severity and duration on oocytes at the growing follicle stage. Reproductive sciences. 2016, 23, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan H-J, Han X, He N, Wang G-L, Gong S, Lin J, et al. Glucocorticoids impair oocyte developmental potential by triggering apoptosis of ovarian cells via activating the Fas system. Scientific reports. 2016, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-Y, Wang J-Z, Li J-J, Wei D-L, Sui H-S, Zhang Z-H, et al. Maternal restraint stress diminishes the developmental potential of oocytes. Biology of Reproduction. 2011, 84, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, CY. Effect of glucocorticoids on spontaneous and follicle-stimulating hormone induced oocyte maturation in mouse oocytes during culture. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2003, 85((2-5)), 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Merris V, Van Wemmel K, Cortvrindt R. In vitro effects of dexamethasone on mouse ovarian function and pre-implantation embryo development. Reproductive Toxicology. 2007, 23, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong S, Sun G-Y, Zhang M, Yuan H-J, Zhu S, Jiao G-Z, et al. Mechanisms for the species difference between mouse and pig oocytes in their sensitivity to glucorticoids. Biology of Reproduction. 2017, 96, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang J-G, Chen W-Y, Li PS. Effects of glucocorticoids on maturation of pig oocytes and their subsequent fertilizing capacity in vitro. Biology of reproduction. 1999, 60, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlet D, Ille N, Ertl R, Alves B, Gastal G, Paiva S, et al. Glucocorticoid metabolism in equine follicles and oocytes. Domestic animal endocrinology. 2017, 59, 11–22. [CrossRef]

- Yuan X-H, Yang B-Q, Hu Y, Fan Y-Y, Zhang L-X, Zhou J-C, et al. Dexamethasone altered steroidogenesis and changed redox status of granulosa cells. Endocrine. 2014, 47, 639–647. [CrossRef]

- Huang T-J, Shirley Li P. Dexamethasone inhibits luteinizing hormone-induced synthesis of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in cultured rat preovulatory follicles. Biology of reproduction. 2001, 64, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael A, Pester L, Curtis P, Shaw R, Edwards C, Cooke B. Direct inhibition of ovarian steroidogenesis by Cortisol and the modulatory role of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Clinical endocrinology. 1993, 38, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph DN, Whirledge S. Stress and the HPA axis: balancing homeostasis and fertility. International journal of molecular sciences. 2017, 18, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain M, Frydman N, Duquenne C, N′ Tumba-Byn T, Benachi A, Habert R, et al. Dexamethasone induces germ cell apoptosis in the human fetal ovary. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2012, 97, E1890–E7. [Google Scholar]

- Sasson R, Amsterdam A. Pleiotropic anti-apoptotic activity of glucocorticoids in ovarian follicular cells. Biochemical pharmacology. 2003, 66, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komiyama J, Nishimura R, Lee H-Y, Sakumoto R, Tetsuka M, Acosta TJ, et al. Cortisol is a suppressor of apoptosis in bovine corpus luteum. Biology of reproduction. 2008, 78, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae MT, Price D, Harlow CR, Critchley HO, Hillier SG. Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated regulation of MMP9 gene expression in human ovarian surface epithelial cells. Fertility and sterility. 2009, 92, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber JR, Nakamura K, Erickson GF. Rat ovary glucocorticoid receptor: identification and characterization. Steroids. 1982, 39, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae MT, Niven D, Critchley HO, Harlow CR, Hillier SG. Antiinflammatory steroid action in human ovarian surface epithelial cells. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2004, 89, 4538–4544. [Google Scholar]

- Tetsuka M, Milne M, Simpson G, Hillier S. Expression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, glucocorticoid receptor, and mineralocorticoid receptor genes in rat ovary. Biology of Reproduction. 1999, 60, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael AE, Papageorghiou AT. Potential significance of physiological and pharmacological glucocorticoids in early pregnancy. Human reproduction update. 2008, 14, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čikoš Š, Babeľová J, Špirková A, Burkuš J, Kovaříková V, Šefčíková Z, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor isoforms and effects of glucocorticoids in ovulated mouse oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Biology of Reproduction. 2019, 100, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakley RH, Webster JC, Sar M, Parker Jr CR, Cidlowski JA. Expression and subcellular distribution of the β-isoform of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Endocrinology. 1997, 138, 5028–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhen T, Grissom S, Afshari C, Cidlowski JA. Dexamethasone blocks the rapid biological effects of 17β-estradiol in the rat uterus without antagonizing its global genomic actions. The FASEB journal. 2003, 17, 1849–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson D, Dey S. Role of histamine in implantation: dexamethasone inhibits estradiol-induced implantation in the rat. Biology of reproduction. 1980, 22, 1136–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whirledge S, Xu X, Cidlowski JA. Global gene expression analysis in human uterine epithelial cells defines new targets of glucocorticoid and estradiol antagonism. Biology of reproduction. 2013, 89, 66–1. [Google Scholar]

- Dmowski W, Ding J, Shen J, Rana N, Fernandez B, Braun D. Apoptosis in endometrial glandular and stromal cells in women with and without endometriosis. Human reproduction. 2001, 16, 1802–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce C, Torres M, Galleguillos C, Sovino H, Boric MA, Fuentes A, et al. Nuclear factor κB pathway and interleukin-6 are affected in eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis. Reproduction. 2009, 137, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meno C, Saijoh Y, Fujii H, Ikeda M, Yokoyama T, Yokoyama M, et al. Left–right asymmetric expression of the TGFβ-family member lefty in mouse embryos. Nature. 1996, 381, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang M, Naidu D, Hearing P, Handwerger S, Tabibzadeh S. LEFTY, a member of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily, inhibits uterine stromal cell differentiation: a novel autocrine role. Endocrinology. 2010, 151, 1320–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanjappa MK, Medrano TI, Lydon JP, Bigsby RM, Cooke PS. Maximal dexamethasone inhibition of luminal epithelial proliferation involves progesterone receptor (PR)-and non-PR-mediated mechanisms in neonatal mouse uterus. Biology of reproduction. 2015, 92, 122–1. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda K, Venkatakrishnan R, Salker MS, Lucas ES, Shaheen F, Kuroda M, et al. Induction of 11β-HSD 1 and activation of distinct mineralocorticoid receptor-and glucocorticoid receptor-dependent gene networks in decidualizing human endometrial stromal cells. Molecular endocrinology. 2013, 27, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Dunk C, Croy AB, Lye SJ. To serve and to protect: the role of decidual innate immune cells on human pregnancy. Cell and tissue research. 2016, 363, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo AS, Schumacher A. The T helper type 17/regulatory T cell paradigm in pregnancy. Immunology. 2016, 148, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinketova K, Mourdjeva M, Oreshkova T. Human decidual stromal cells as a component of the implantation niche and a modulator of maternal immunity. Journal of pregnancy. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Whirledge SD, Oakley RH, Myers PH, Lydon JP, DeMayo F, Cidlowski JA. Uterine glucocorticoid receptors are critical for fertility in mice through control of embryo implantation and decidualization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015, 112, 15166–15171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson SA, Jin M, Yu D, Moldenhauer LM, Davies MJ, Hull ML, et al. Corticosteroid therapy in assisted reproduction–immune suppression is a faulty premise. Human reproduction. 2016, 31, 2164–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori M, Bogdan A, Balassa T, Csabai T, Szekeres-Bartho J, editors. The decidua—the maternal bed embracing the embryo—maintains the pregnancy. Seminars in immunopathology; 2016: Springer.

- Bartmann C, Segerer SE, Rieger L, Kapp M, Sütterlin M, Kämmerer U. Quantification of the predominant immune cell populations in decidua throughout human pregnancy. American journal of reproductive immunology. 2014, 71, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson TA, Saunders PT, Moffett-King A, Groome NP, Critchley HO. Steroid receptor expression in uterine natural killer cells. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2003, 88, 440–449. [Google Scholar]

- Quenby S, Kalumbi C, Bates M, Farquharson R, Vince G. Prednisolone reduces preconceptual endometrial natural killer cells in women with recurrent miscarriage. Fertility and sterility. 2005, 84, 980–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta C, Riboldi E, Ippolito A, Sica A, editors. Molecular and epigenetic basis of macrophage polarized activation. Seminars in immunology; 2015: Elsevier.

- Gustafsson C, Mjösberg J, Matussek A, Geffers R, Matthiesen L, Berg G, et al. Gene expression profiling of human decidual macrophages: evidence for immunosuppressive phenotype. PloS one. 2008, 3, e2078. [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen J, Möttönen M, Komi J, Alanen A, Lassila O. Phenotypic characterization of human decidual macrophages. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 2003, 131, 498–505. [Google Scholar]

- Thiruchelvam U, Maybin JA, Armstrong GM, Greaves E, Saunders PT, Critchley HO. Cortisol regulates the paracrine action of macrophages by inducing vasoactive gene expression in endometrial cells. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2016, 99, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton J, Yamamoto S, Bryant-Greenwood G. Relaxin modulates proinflammatory cytokine secretion from human decidual macrophages. Biology of reproduction. 2011, 85, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaks V, Birnberg T, Berkutzki T, Sela S, BenYashar A, Kalchenko V, et al. Uterine DCs are crucial for decidua formation during embryo implantation in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008, 118, 3954–3965. [Google Scholar]

- Matasić R, Dietz AB, Vuk-Pavlović S. Dexamethasone inhibits dendritic cell maturation by redirecting differentiation of a subset of cells. Journal of leukocyte biology. 1999, 66, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigler MB, Egli SB, Hysek CM, Hoenger G, Schmied L, Baldin FS, et al. Stress-induced in vivo recruitment of human cytotoxic natural killer cells favors subsets with distinct receptor profiles and associates with increased epinephrine levels. PloS one. 2015, 10, e0145635. [Google Scholar]

- Busillo JM, Azzam KM, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoids sensitize the innate immune system through regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011, 286, 38703–38713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutsatsou P, Sekeris CE. Steroid receptors in the uterus: implications in endometriosis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003, 997, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta S, Gyomorey S, Lye SJ, Gibb W, Challis JR. Effect of labor on glucocorticoid receptor (GRTotal, GRα, and GRβ) proteins in ovine intrauterine tissues. The Journal of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation: JSGI. 2003, 10, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M. The physiological roles of placental corticotropin releasing hormone in pregnancy and childbirth. Journal of physiology and biochemistry. 2013, 69, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton E, Perkins A, Woods R, Eben F, Wolfe C, Behan D, et al. Corticotropin releasing hormone-binding protein (CRH-BP): plasma levels decrease during the third trimester of normal human pregnancy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1993, 76, 260–262. [Google Scholar]

- Challis JR, Sloboda DM, Alfaidy N, Lye SJ, Gibb W, Patel FA, et al. Prostaglandins and mechanisms of preterm birth. Reproduction-Cambridge-. 2002, 124, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li X, Zhu P, Myatt L, Sun K. Roles of glucocorticoids in human parturition: a controversial fact? Placenta. 2014, 35, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANDERSON AB, Flint A, Turnbull A. Mechanism of action of glucocorticoids in induction of ovine parturition: effect on placental steroid metabolism. Journal of Endocrinology. 1975, 66, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challis JR, Lye SJ, Gibb W, Whittle W, Patel F, Alfaidy N. Understanding preterm labor. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001, 943, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liggins G, Grieves S. Possible role for prostaglandin F2α in parturition in sheep. Nature. 1971, 232, 629–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyomorey S, Lye S, Gibb W, Challis J. Fetal-to-maternal progression of prostaglandin H2 synthase-2 expression in ovine intrauterine tissues during the course of labor. Biology of reproduction. 2000, 62, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challis JR, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocrine reviews. 2000, 21, 514–550. [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Liu C, Sun K. Induction of amnion epithelial apoptosis by cortisol via tPA/plasmin system. Endocrinology. 2016, 157, 4487–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi Y, Wang W, Zhang C, Liu C, Lu J, Li W, et al. Autophagic degradation of collagen 1A1 by cortisol in human amnion fibroblasts. Endocrinology. 2017, 158, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson V, Liu D, Billett E, Kirk S. Amniotic membrane collagen content and type distribution in women with preterm premature rupture of the membranes in pregnancy. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1997, 104, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa PD, Garite TJ, Porto M, Glynn L, Chicz-DeMet A, Dunkel-Schetter C, et al. Placental corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), spontaneous preterm birth, and fetal growth restriction: a prospective investigation. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2004, 191, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challis J, Matthews S, Van Meir C, Ramirez M. Current topic: the placental corticotrophin-releasing hormone-adrenocorticotrophin axis. Placenta. 1995, 16, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft I, Day J, Brummer V, Horwell D, Morgan H. Betamethazone induction of labour. SAGE Publications; 1976.

- Nwosu UC, Wallach EE, Bolognese RJ. Initiation of labor by intraamniotic cortisol instillation in prolonged human pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1976, 47, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott JP, Radin TG. The effect of corticosteroid administration on uterine activity and preterm labor in high-order multiple gestations. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1995, 85, 250–254. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander N, Rosenlöcher F, Stalder T, Linke J, Distler W, Morgner J, et al. Impact of antenatal synthetic glucocorticoid exposure on endocrine stress reactivity in term-born children. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2012, 97, 3538–3544. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard PL, Ballard RA. Scientific basis and therapeutic regimens for use of antenatal glucocorticoids. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1995, 173, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liggins, GC. Premature parturition after infusion of corticotrophin or cortisol into foetal lambs. The Journal of endocrinology. 1968, 42, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Blanco A, Diago V, De La Cruz VS, Hervás D, Cháfer-Pericás C, Vento M. Can stress biomarkers predict preterm birth in women with threatened preterm labor? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017, 83, 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Murphy VE, Smith R, Giles WB, Clifton VL. Endocrine regulation of human fetal growth: the role of the mother, placenta, and fetus. Endocrine reviews. 2006, 27, 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Class QA, Lichtenstein P, Långström N, D'onofrio BM. Timing of prenatal maternal exposure to severe life events and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population study of 2.6 million pregnancies. Psychosomatic medicine. 2011, 73, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman PD, Cutfield W, Hofman P, Hanson MA. The fetal, neonatal, and infant environments—the long-term consequences for disease risk. Early human development. 2005, 81, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, DJ. The developmental origins of chronic adult disease. Acta paediatrica. 2004, 93, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh RR, Cuffe J, Moritz KM, editors. Short-and long-term effects of exposure to natural and synthetic glucocorticoids during development. Proceedings of the Australian Physiological Society; 2012.

- Erni K, Shaqiri-Emini L, La Marca R, Zimmermann R, Ehlert U. Psychobiological effects of prenatal glucocorticoid exposure in 10-year-old-children. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2012, 3, 104.

- Huh SY, Andrew R, Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman KP, Seckl JR, Gillman MW. Association between umbilical cord glucocorticoids and blood pressure at age 3 years. BMC medicine. 2008, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cuffe J, Dickinson H, Simmons D, Moritz K. Sex specific changes in placental growth and MAPK following short term maternal dexamethasone exposure in the mouse. Placenta. 2011, 32, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Connell BA, Moritz KM, Roberts CT, Walker DW, Dickinson H. The placental response to excess maternal glucocorticoid exposure differs between the male and female conceptus in spiny mice. Biology of reproduction. 2011, 85, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Sullivan L, Cuffe JS, Paravicini TM, Campbell S, Dickinson H, Singh RR, et al. Prenatal exposure to dexamethasone in the mouse alters cardiac growth patterns and increases pulse pressure in aged male offspring. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e69149. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun T, Meng W, Shang H, Li S, Sloboda DM, Ehrlich L, et al. Early dexamethasone treatment induces placental apoptosis in sheep. Reproductive sciences. 2015, 22, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton V, Cuffe J, Moritz K, Cole T, Fuller P, Lu N, et al. The role of multiple placental glucocorticoid receptor isoforms in adapting to the maternal environment and regulating fetal growth. Placenta. 2017, 54, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy VE, Gibson PG, Giles WB, Zakar T, Smith R, Bisits AM, et al. Maternal asthma is associated with reduced female fetal growth. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2003, 168, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuffe J, O'sullivan L, Simmons D, Anderson S, Moritz K. Maternal corticosterone exposure in the mouse has sex-specific effects on placental growth and mRNA expression. Endocrinology. 2012, 153, 5500–5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronson SL, Bale TL. Prenatal stress-induced increases in placental inflammation and offspring hyperactivity are male-specific and ameliorated by maternal antiinflammatory treatment. Endocrinology. 2014, 155, 2635–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong JN, Cuffe JS, Jefferies AJ, Anevska K, Moritz KM, Wlodek ME. Sex-specific metabolic outcomes in offspring of female rats born small or exposed to stress during pregnancy. Endocrinology. 2016, 157, 4104–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter T, Grecian S, Reynolds R. Sex differences in early-life programming of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in humans suggest increased vulnerability in females: a systematic review. Journal of developmental origins of health and disease. 2017, 8, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, V. Sex and the human placenta: mediating differential strategies of fetal growth and survival. Placenta. 2010, 31, S33–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mericq V, Medina P, Kakarieka E, Márquez L, Johnson M, Iniguez G. Differences in expression and activity of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and 2 in human placentas of term pregnancies according to birth weight and gender. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2009, 161, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuffe JS, Saif Z, Perkins AV, Moritz KM, Clifton VL. Dexamethasone and sex regulate placental glucocorticoid receptor isoforms in mice. Journal of Endocrinology. 2017, 234, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcock G, Kildea S, Elgbeili G, Laplante D, Cobham V, King S. Prenatal maternal stress shapes children’s theory of mind: the QF2011 Queensland Flood Study. Journal of developmental origins of health and disease. 2017, 8, 483–492.

- Sandman CA, Glynn LM, Davis EP. Is there a viability–vulnerability tradeoff? Sex differences in fetal programming. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2013, 75, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite EC, Murphy SE, Ramchandani PG, Hill J. Associations between biological markers of prenatal stress and infant negative emotionality are specific to sex. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017, 86, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott NM, Hodyl NA, Murphy VE, Osei-Kumah A, Wyper H, Hodgson DM, et al. Placental cytokine expression covaries with maternal asthma severity and fetal sex. The Journal of Immunology. 2009, 182, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saif Z, Hodyl N, Hobbs E, Tuck A, Butler M, Osei-Kumah A, et al. The human placenta expresses multiple glucocorticoid receptor isoforms that are altered by fetal sex, growth restriction and maternal asthma. Placenta. 2014, 35, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saif Z, Hodyl NA, Stark MJ, Fuller PJ, Cole T, Lu N, et al. Expression of eight glucocorticoid receptor isoforms in the human preterm placenta vary with fetal sex and birthweight. Placenta. 2015, 36, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saif Z, Dyson RM, Palliser HK, Wright IM, Lu N, Clifton VL. Identification of eight different isoforms of the glucocorticoid receptor in guinea pig placenta: relationship to preterm delivery, sex and betamethasone exposure. PloS one. 2016, 11, e0148226. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton VL, McDonald M, Morrison JL, Holman SL, Lock MC, Saif Z, et al. Placental glucocorticoid receptor isoforms in a sheep model of maternal allergic asthma. Placenta. 2019, 83, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akison L, Andersen I, Kent N, Steane S, Saif Z, Clifton V, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor isoform expression profile in the rat placenta and fetal liver in pregnancies exposed to periconceptional alcohol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2018, 42(S1), 228A-A.

- Strickland I, Kisich K, Hauk PJ, Vottero A, Chrousos GP, Klemm DJ, et al. High constitutive glucocorticoid receptor β in human neutrophils enables them to reduce their spontaneous rate of cell death in response to corticosteroids. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2001, 193, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruver-Yates AL, Cidlowski JA. Tissue-specific actions of glucocorticoids on apoptosis: a double-edged sword. Cells. 2013, 2, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead C, Walker S, Lappas M, Tong S. Circulating RNA coding genes regulating apoptosis in maternal blood in severe early onset fetal growth restriction and pre-eclampsia. Journal of Perinatology. 2013, 33, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).