1. Introduction

Earthworms are iteroparous organisms with indeterminate growth, i.e. they continue to increase in size throughout their life and after completion of sexual development. Terrestrial oligochaetes vary greatly in size. Depending on the species, adult earthworms can reach between 10 mm and 3 m in length and between <1 mm and >25 mm in width, with most being of length 5-15 cm. Among the more than 7000 species described to date, very few (~20) reach lengths greater than 1 m. The longest earthworm on record is

Amynthas mekongianus, which found in the mud banks of the Mekong River in Southeast Asia. This species reaches almost 3 m in length and is about the same size as

Megascolides australis, the “Giant Gippsland Earthworm”. Most giant earthworms, which are found in particular locations in the Southern Hemisphere, reach up to 3 m in length and up to 500-600 g in weight, although much of this weight is due to soil contained in the gut. There is no standardized size classification for earthworms. Nonetheless, in European fauna, small earthworms are generally less than 5 cm long and weigh less than 0.5 g, medium-sized earthworms range from 5-10 cm in length and 0.5-5 g in weight, large-sized earthworms range from 10-30 cm in length and 5-20 g in weight, and giant earthworms exceed these sizes (reaching up to 1 m long and 100 g in weight) [

1].

These atypically giant earthworm species remain a scientific curiosity regarding their biology, but they cannot be considered cases of gigantism. Gigantism occurs when organisms belonging to the same species are much larger than normal or exhibit excessive growth.

Earthworms obtain energy from the organic matter on which they feed, and their growth mainly depends on the quality of the resource and on the species, as well as on food availability, environmental factors (which can directly or indirectly affect growth by modifying food availability) and other biotic factors such as competition [

2]. This is particularly evident because of the indeterminate growth and large species-dependent variations in size observed in earthworms.

Here we present details of the extraordinary growth of individual specimens of Eisenia andrei and Dendrobaena hortensis reared under particular culture conditions and fed a special diet. Individuals almost 20 times the average weight of individuals of the species were obtained. Some possible explanations for this interesting phenomenon are discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental trials were conducted in the laboratory and greenhouse facilities of the Animal Ecology Group at the University of Vigo (Spain) and in the laboratory and vermicomposting facilities of the Minhobox company, in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Earthworms (Eisenia andrei and Dendrobaena hortensis) were collected by hand sorting of pilot vermicomposting reactors housed in the aforementioned facilities.

In the trials in which the gigantic earthworms were obtained, newly mature individuals (n=5) of Eisenia andrei, Eisenia fetida and Dendrobaena hortensis were placed in 1700 cm3 plastic dishes (n=5). These earthworms were supplied with 1500 cm3 of pretreated (aeration for 35 days) ox ruminal content. The plastic dishes holding the earthworms were placed in growth chambers in complete darkness and at a constant temperature of 11ºC. Earthworms were not supplied with any additional food during the trial, which ended when the earthworms began to lose weight (42 months). Similar trials were conducted with D. hortensis, which were held at room temperature. Unfortunately, and because Minhobox is a commercial company and not a research institute, the earthworm growth was not recorded regularly, and the findings are somewhat observational.

3. Results

In

Eisenia andrei the mean mature weight of individuals was much greater in those fed on sewage sludge (2.51 g) than in those fed on spent coffee grounds (0.34 g); some very large individuals (3.5 g) were obtained from the reactor supplied with sewage sludge (

Figure 1).

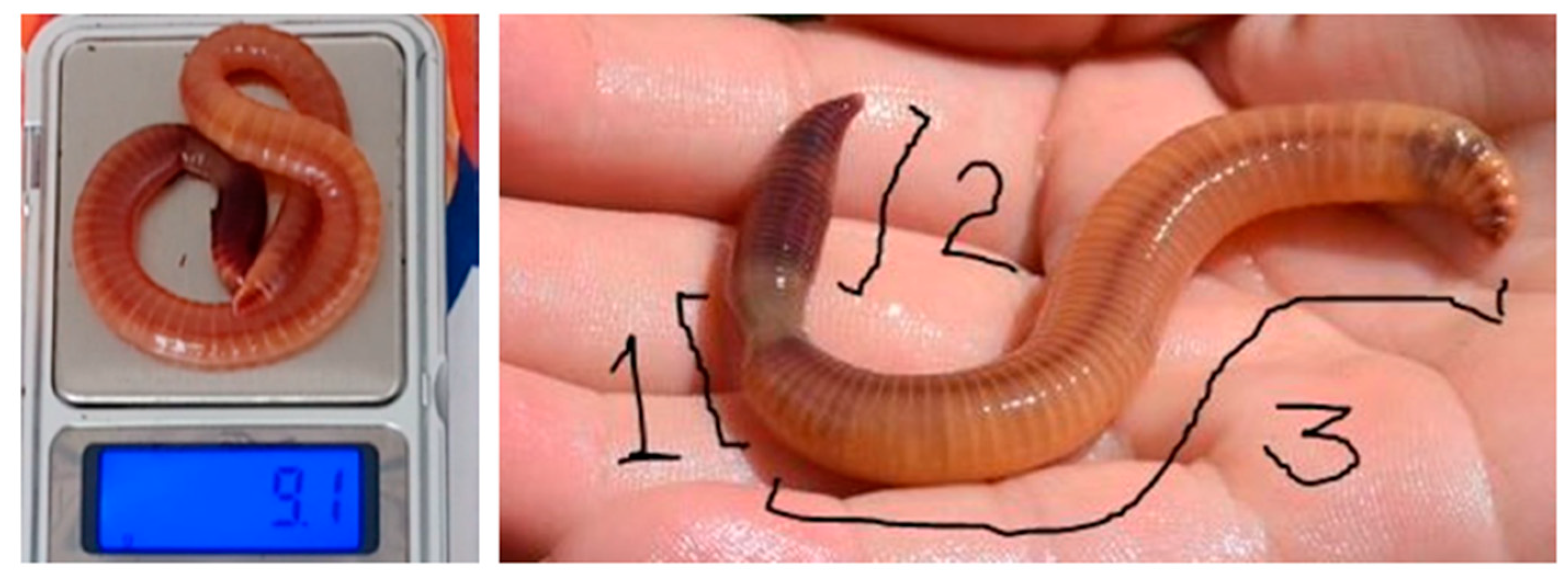

Gigantic individuals of

Eisenia andrei (9. 1 g) and

Eisenia fetida (7 g) were obtained after being held for 42 weeks at 11ºC and fed ox ruminal content (

Figure 2). These were the heaviest weights obtained, but 20% of the individuals reached weights of between 5.5 and 6 g. These gigantic specimens displayed notable modifications in their external morphology, including great dilation of the body that began in the segments posterior to the clitellum, with the typical red coloration of this species being maintained only in the segments anterior to the clitellum, with those posteriors to the clitellum being a lighter salmon colour (

Figure 2).

The gigantic specimens of E. andrei and E. fetida did not excrete casts, did not produce cocoons and their guts apparently remained empty.

The earthworm species

Dendrobaena hortensis also reached an extraordinary weight (7.8 g) when held at room temperature and fed ox ruminal content (

Figure 3). This species also reached large body weights when fed on fresh sewage sludge, although lower than those fed the ox ruminal content (

Figure 3). In both substrates,

D. hortensis produced numerous viable cocoons.

4. Discussion

The findings of this observational study can be summarized as follows: 1) Specimens of the earthworm species Eisenia andrei and E. fetida reached extraordinary weights of respectively 9.1 g and 6 g when fed ox ruminal content, and 2) specimens of Dendrobaena hortensis reached extraordinary weights of 7.8 g, when fed ox ruminal content, and of 5.3 g, when fed fresh sewage sludge. These are exceptional records and the weights are much higher than reported to date in any scientific study.

The magnificent, comprehensive EGrowth database, constructed by soil ecologist Jerome Mathieu, includes data regarding the growth of more than 50 earthworm species [

3]. Mathieu searched for earthworm growth data in scientific articles and PhD theses since 1900, analyzing more than 400 publications and finally using 162 of these to build the database. The EGrowth database includes 1073 earthworm growth curves, constructed with more than 16000 biomass measurements [

3]. The best documented earthworm species were found to be

E. fetida (n=244),

Lumbricus terrestris (n=131),

E. andrei (n=87),

Aporrectodea caliginosa (n=74) and

Lumbricus rubellus (n=70) [

3]. The maximum weights recorded were 3008 mg for

E. andrei and 2471 mg for

E. fetida. These are the earthworm species most frequently used in vermicomposting, with

E. andrei being the predominant species used in vermicomposting facilities worldwide [

4]. Although most specialists now consider

E. andrei and

E. fetida different species, older studies and even much of the current literature refer to both species as

E. fetida or

E. foetida, the latter of which is an incorrect and invalid version of the original

E. fetida [

5]. The two species are almost identical, only differing in the body pigmentation pattern, and with few differences in ecological or biological parameters. However, growth and reproduction rates are somewhat higher in

E. andrei than in

E. fetida [16]. The biology and ecology of

E. fetida and

E. andrei are well known, and their life cycles and population biology have been investigated by several authors [

2,

6]. The fact that these are by far the best documented species regarding growth makes the observation of these gigantic individuals of

E. andrei, with a body weight that triples the previous record, even more striking.

Interestingly, in our vermireactors fed with fresh sewage sludge, we also obtained specimens of both species that also exceed the records obtained to date, although the sizes are much smaller than those of the gigantic E. andrei and E. fetida obtained in Brazil.

The Egrowth database does not include any information on

Dendrobaena hortensis, although it does include data on its close relative

D. veneta. The maximum weight of

D. veneta previously recorded is 3.34 g, which is also much less than the weights obtained in the trials in Brazil and Vigo and reported here. The epigeic earthworms

D. veneta and

D. hortensis are also commonly used in vermicomposting and vermiculture. They are often considered the same species because their morphology is similar, except for the body colour. The dorsal side of

D. hortensis has red-violet stripes and the ventral side is pale red, whereas

D. veneta is uniformly red and is not striped. However, the species are phylogenetically different [

4,

7] and their life cycle parameters are unknown, mainly due to this taxonomic confusion.

The most plausible explanation for these extreme cases of gigantism in earthworms seems to be the diet based on the ox ruminal content and more specifically the microbial content of this substrate, as the physical and chemical characteristics are not very different from those of other substrates commonly used in vermicomposting. In addition, specific genes must also be involved as the extreme gigantism appeared in ca. 20% of the individuals of the studied populations. Further work is required to determine the mechanisms that explain these interesting findings.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this observational study can be summarized as follows: 1) Specimens of the earthworm species Eisenia andrei and E. fetida reached extraordinary weights of respectively 9.1 g and 6 g when fed ox ruminal content, and 2) specimens of Dendrobaena hortensis reached extraordinary weights of 7.8 g, when fed ox ruminal content, and of 5.3 g, when fed fresh sewage sludge. These are exceptional records, and the weights are much higher than reported to date in any scientific study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D. and A.G.; methodology, J.D. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D. and A.G.; writing—review and editing, J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PID2021-124265OB-100), the Xunta de Galicia (ED431C 2022/07) and by the MCIN/AEI and European Union Next Generation_EU under the project TED2021-129437B-100.

Conflicts of Interest

JD declares that he has no conflicts of interest. AG is the executive director of the Brazilian company Minhobox. AG declares that the company won´t use the results of this study for commercial purposes.

References

- Marchán, D.F.; Domínguez, J.; Hedde, M.; Decaëns, T. The cradle of giants: insights into the origin of Scherotheca Bouché, 1972 (Lumbricidae, Crassiclitellata) with the descriptions of eight new species from Corsica, France. Zoosystema 2023, 45, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J. State of the art and new perspectives on vermicomposting research. In Earthworm Ecology, 2nd ed.; Edwards, C.A., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2004; pp. 401–424. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, J. EGrowth: A global database on intraspecific body growth variability in earthworm. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 122, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J. Earthworms and vermicomposting. In Earthworms, the so ecological engineers of soil; Ray, S., Ed.; Intech Open Science: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018; pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, E.G. A guide to the valid names of Lumbricidae (Oligochaeta). In Earthworm Ecology from Darwin to Vermiculture; Satchell, J.E., Ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1983; pp. 475–485. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, J.; Edwards, C.A. Biology and ecology of earthworm species used for vermicomposting. In Vermiculture Technology: Earthworms, Organic Waste and Environmental Management; Edwards, C.A., Arancon, N.Q., Sherman, R.L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2011; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, J.; Aira, M.; Breinholt, J.W.; Stojanovic, M.; James, S.W.; Pérez-Losada, M. Underground evolution: new roots for the old tree of lumbricid earthworms. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015, 83, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).