Submitted:

01 September 2023

Posted:

05 September 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

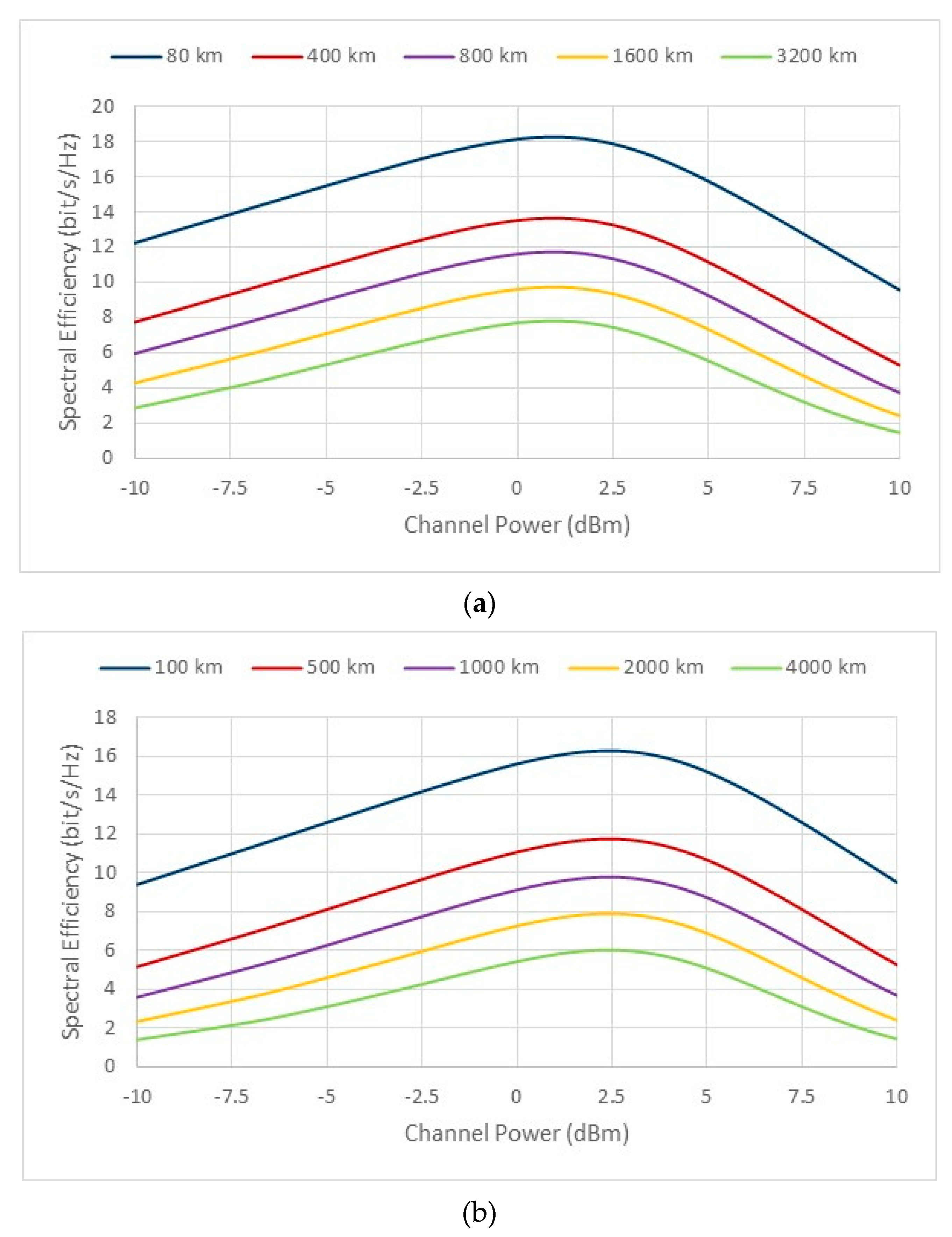

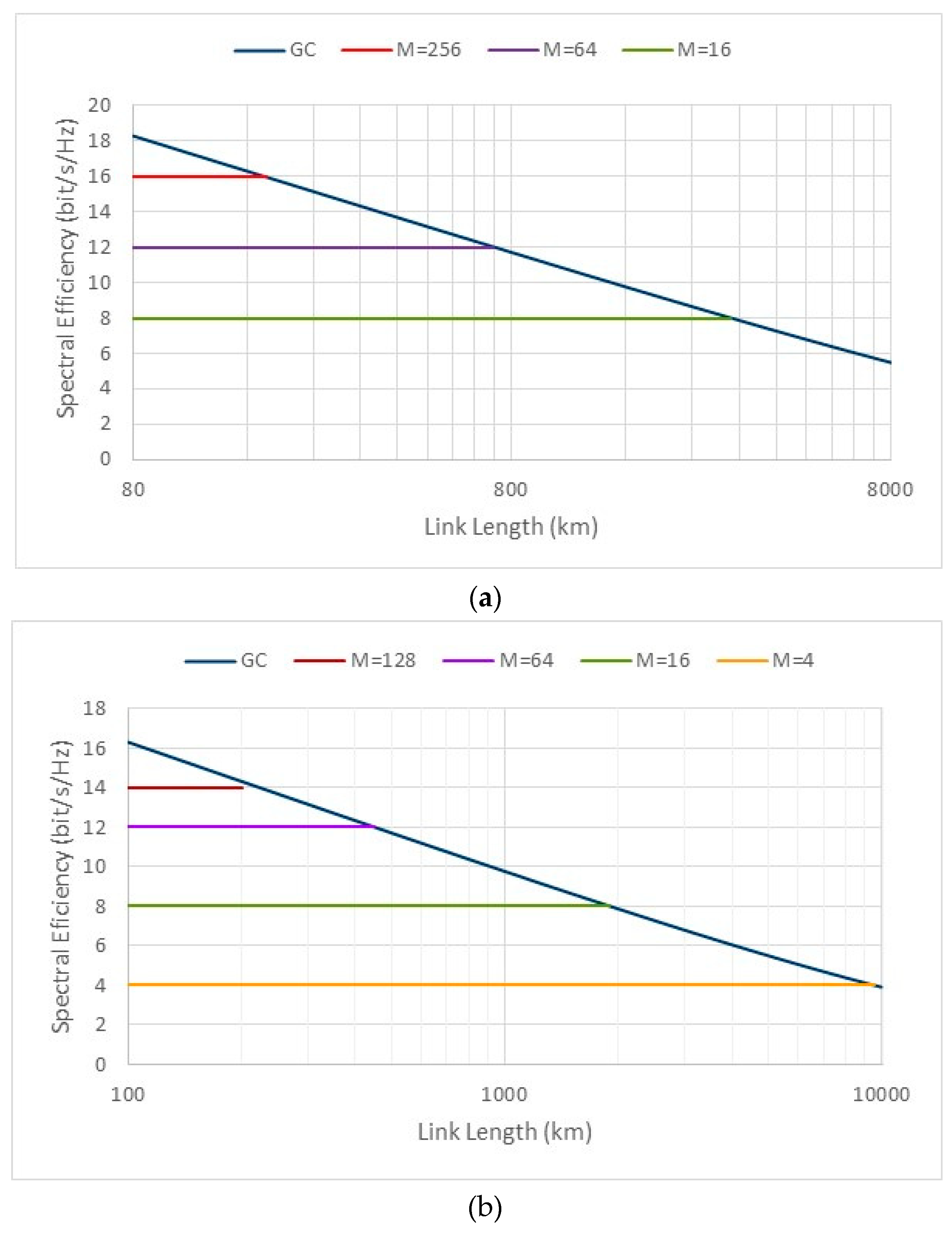

2. Channel Capacity

2.1. Capacity of a Communication Channel

2.2. Capacity of an Optical Channel

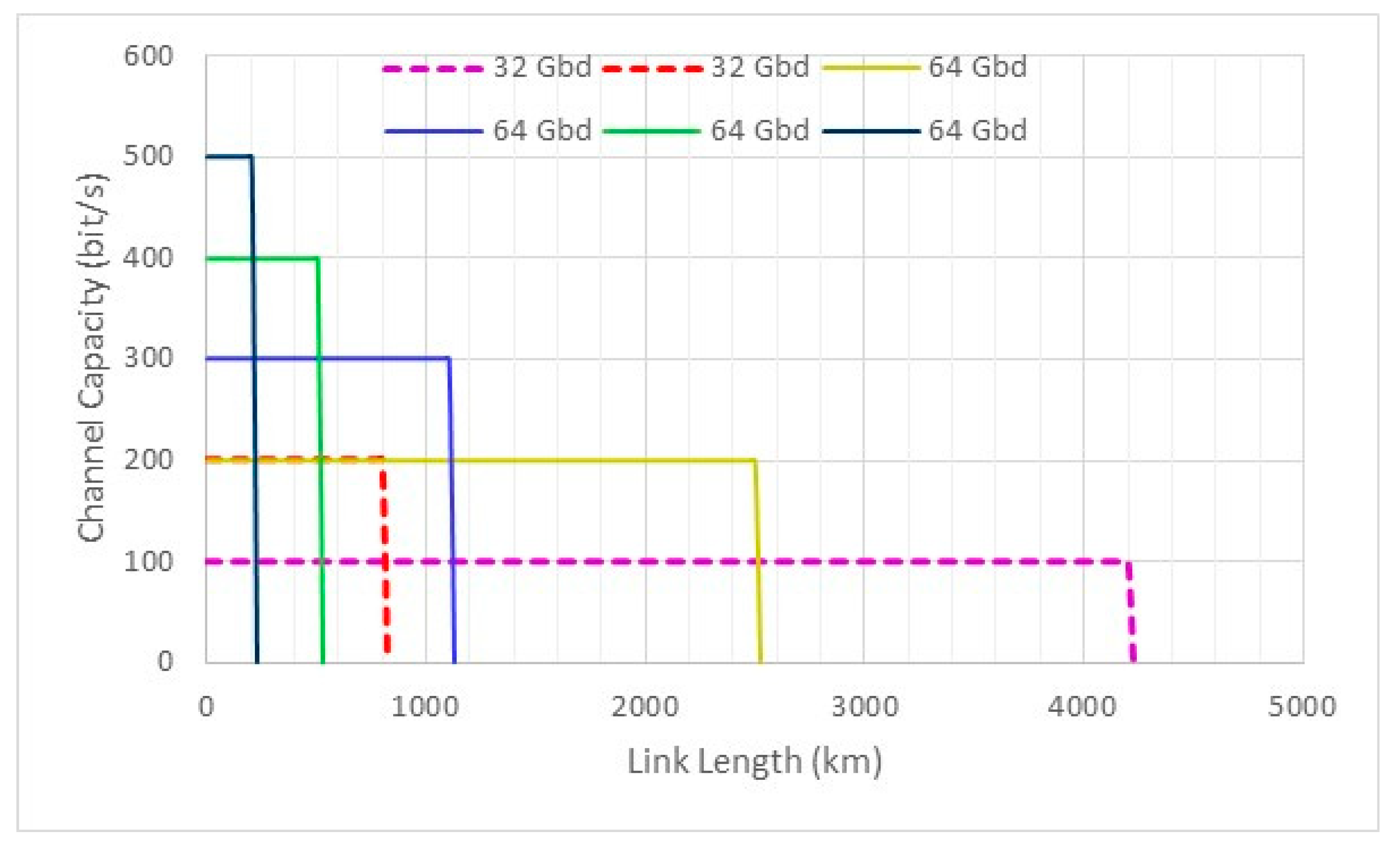

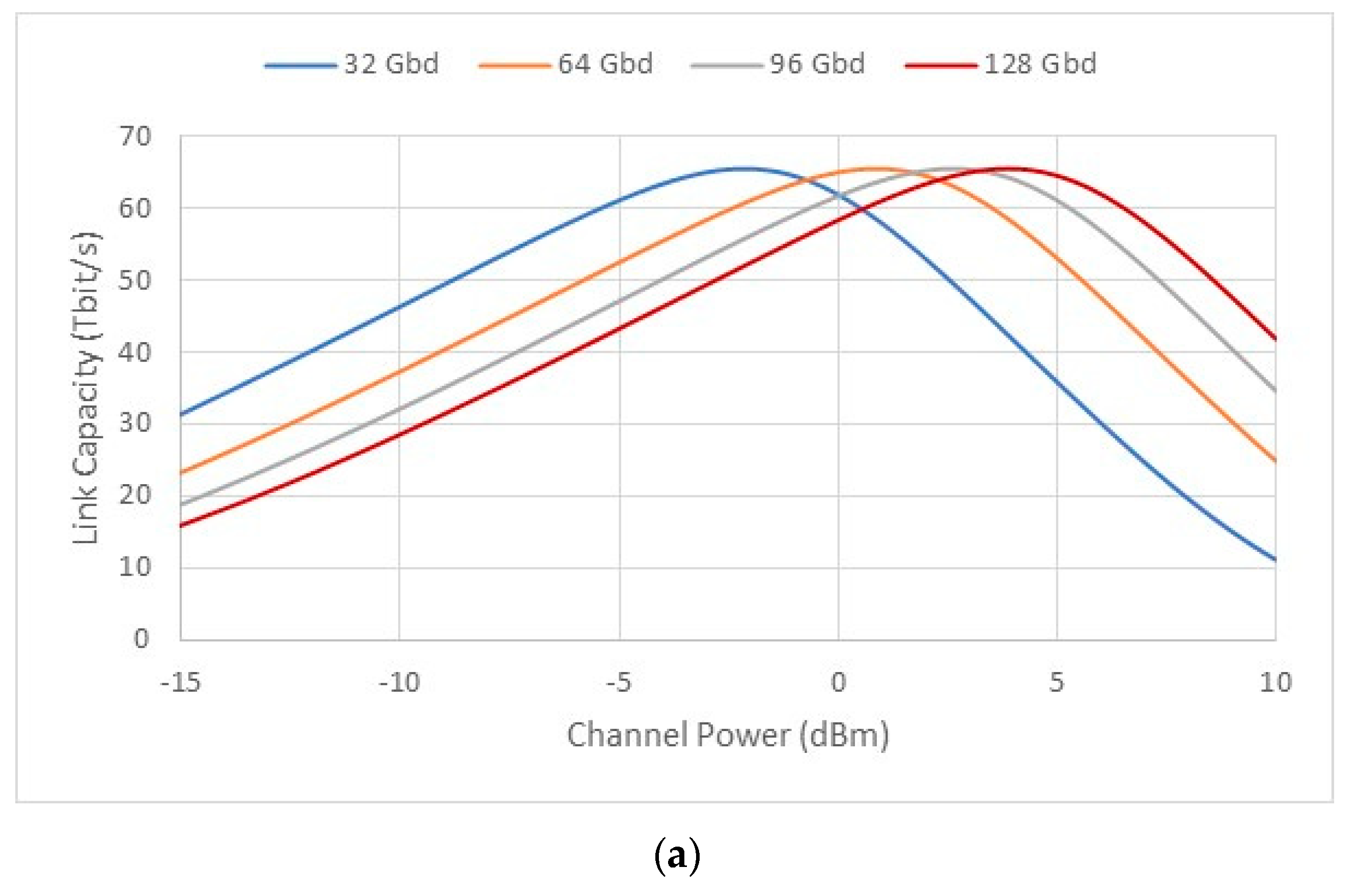

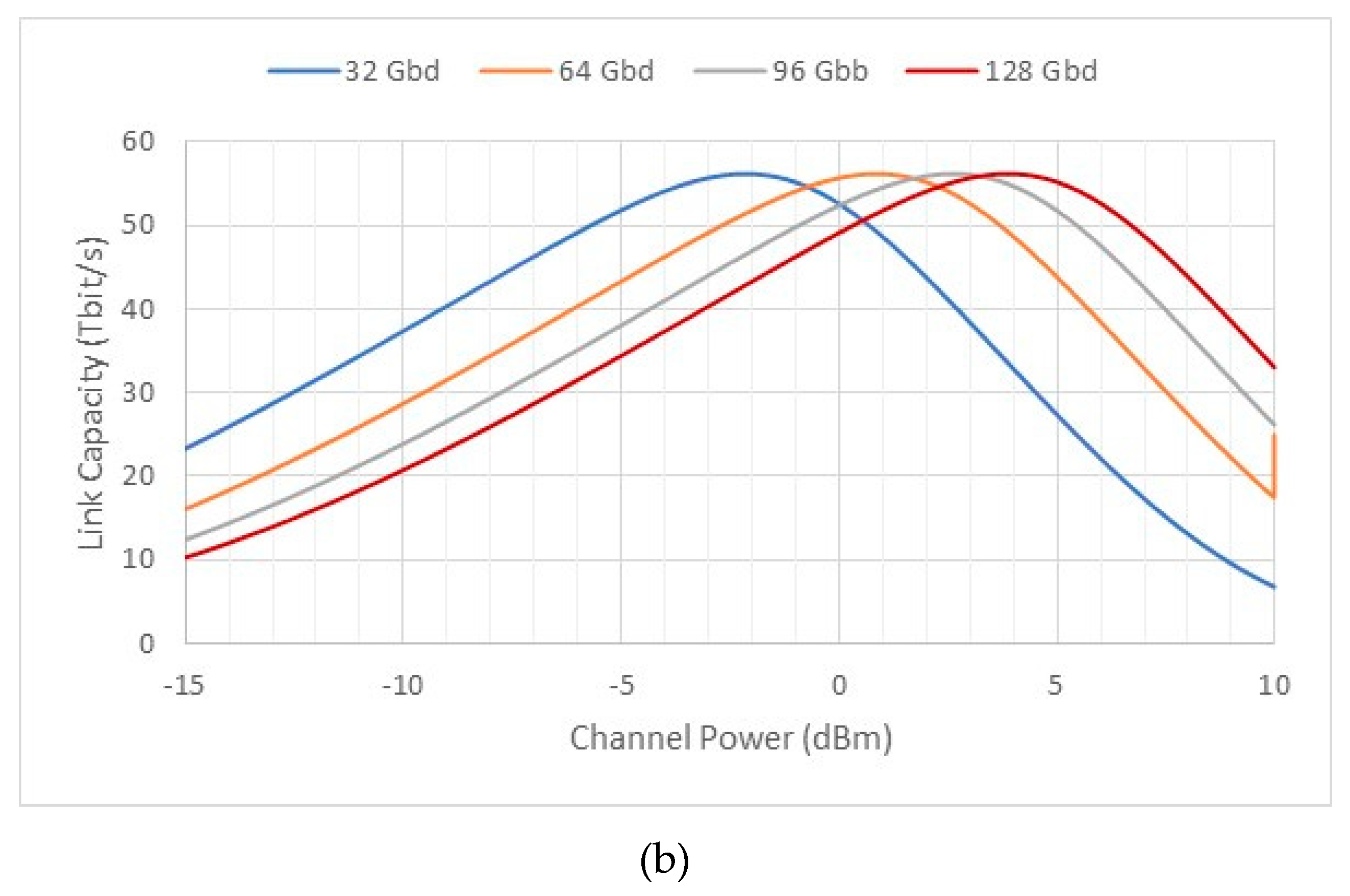

3. Link and Network Capacity

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Winzer, P. J.; Neilson, D. T. From Scaling Disparities to Integrated Parallelism: A Decathlon for a Decade. J. Lightw.Technol. 2017, 35, 1099–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Campos, L. A. Coherent Optics Ready for Prime Time in Short-Haul Networks. IEEE Network 2021, March/April, 8-14.

- Kao, K. C.; Hockham, G. A. Dielectric-fibre surface waveguides for optical frequencies. Proceedings of the IEE 1966, 113, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essiambre, R.-J.; Tkach, R. W. Capacity Trends and Limits of Optical Communication Networks. Proceedings of the IEEE 2012, 100, 1035–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzer, P. J.; Neilson D., T.; Chraplyvy, A. R. Fiber-optic transmission and networking: the previous 20 and the next 20 years. Optics Express 2018, 26, 24190–24239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, N.; Zong, L.; Jiang, H.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, K. Challenges and Enabling Technologies for Multi-Band WDM Optical Networks. J. Lightw. Technol. 2022, 40, 3385–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon C., E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. The Bell System Technical J. 1948, 27, 349–423, 626–656.

- Mitra, P. P.; Stark, J. B. Nonlinear limits to the information capacity of optical fiber communications. Nature 2001, 411, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essiambre, R.-J.; Kramer, G.; Winzer P., J.; Foschini G., J.; Goebel, B. Capacity limits of optical fiber networks. J. Lightw.Technol. 2010, 28, 662–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A. D.; Zhao, J.; Cotter, D. Approaching the Non-Linear Shannon Limit. J. Lightw.Technol. 2010, 28, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, G.; Poggiolini, P.; Carena, A.; Curri, V.; Forghieri, F. Analytical results on channel capacity in uncompensated optical links with coherent detection. Opt. Express 2011, 19, B438–B449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggiolini, P; Bosco, G.; Carena A.; Curri, V.; Jiang Y.; Forghieri F. The GN-Model of Fiber Non-Linear Propagation and its Applications. J. Lightw.Technol. 2014, 32, 694–721.

- Souza, A.; Correia, B.; Costa, N.; Pedro, J.; Pires, J. Accurate and scalable quality of transmission estimation for wideband optical systems. Proc. IEEE 26th Int. Work. on Comp. Aid. Mod. and Design. of Comm. Links and Networks, 25-27 Oct. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Matzner, R.; Semrau, D.; Luo, R.; Zervas, G.; Bayvel, P. Making intelligent topology design choices: understanding structural and physical property performance implications in optical networks. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2021, 13, D53–D67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carena, A.; Curri, V.; Bosco, G.; Poggiolini, P.; Forghieri, F. Modeling of the Impact of Nonlinear Propagation Effects in Uncompensated Optical Coherent Transmission Links. J. Lightw.Technol. 2012, 30, 1524–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggiolini P; Carena, A.; Curri, V; Bosco, G.; Forghierim F. Analytical Modeling of Nonlinear Propagation in Uncompensated Optical Transmission Links. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2011, 23, 742–744.

- Gené, J. M.; Perelló, J.; Cho, J.; Spadaro, S. Practical Spectral Efficiency Estimation for Optical Networking. Proc. Int. Conf. Transp. Opt. Networ. Paper Tu.A3.1, Bucharest, Romania, 2-6 July 2023 .

- Olsson, S. L. I; Cho, J.; Chandrasekhar, S.; Chen, X. ; Burrows, E C.; Winzer, P. J. Record-High 17.3-bit/s/Hz Spectral Efficiency Transmission over 50 km Using Probabilistically Shaped PDM 4096-QAM. Proc. Opt. Fiber Commun. Conf., Paper Th4C.5, San Diego, California, USA, 11-15 March 2018. 15 March.

- Chandrasekhar, S.; Li, B.; Cho, J.; Chen, X.; Burrows, E. C.; Raybon, G.; Winzer, P. J. High-spectral-efficiency transmission of PDM 256-QAM with Parallel Probabilistic Shaping at Record Rate-Reach Trade-offs. Proc. Eur. Conf. Opt. Commun. Paper Th.3.C, Dusseldorf, Germany, 18-22, Sept. 2016.

- Zami, T.; Lavigne, B.; Bertolini, M. How 64 GBaud Optical Carriers Maximize the Capacity in Core Elastic WDM Networks with Fewer Transponders per Gb/s. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2019, 11, A20–A32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-A, et al. Enabling Technology in High-Baud-Rate Coherent Optical Communication Systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 2020.

- Chen, X.; Raybon, G.; Che D.; Cho, J.; Kim, K. W. Transmission of 200-GBaud PDM Probabilistically Shaped 64-QAM Signals Modulated via a 100-GHz Thin-film LiNbO3 I/Q Modulator. Proc. Opt. Fiber Commun. Conf. Paper F3C.5, São Francisco, Califórnia, USA, 6-10 June 2021.

- Yamazaki, H. et al. Transmission of 160.7-GBaud 1.64-Tbps Signal Using Phase-Interleaving Optical Modulator and Digital Spectral Weaver. Proc. Eur. Conf. Opt. Commun. Paper We3D.2, Basel, Switzerland, 18–22 Sep. 2022.

- Idler, A.; Buchali, F.; Schuh K., Experimental Study of Symbol-Rates and MQAM Formats for Single Carrier 400 Gb/s and Few Carrier 1 Tb/s Options. Proc. Opt. Fiber Commun. Conf. Paper Tu3A.7, Anaheim, California, United USA, 20-24 March 2026.

- Matsushita, A.; Nakamura, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Hamaoka, F.; Kisaka, Y. 41-Tbps C-Band WDM Transmission With 10-bps/Hz Spectral Efficiency Using1-Tbps/λ Signals. J. Lightw.Technol. 2020, 38, 2905– 2911.

- Buchali, F.; Aref, V.; Chagnon, M.; Dischler, R.; Hettrich, H.; Schmid, R.; Moeller, M. 52.1 Tb/s C-band DCI transmission over DCI distances at 1.49 Tb/s/λ. Proc. Eur. Conf. Opt. Commun. Paper Mo1E-4, Brussels, Belgium, 6-20 Dec., 2020.

- Pires, J. J. O.; O´Mahony, M.; Parnis, N.; Jones, E. Scaling limitations in full-mesh WDM ring networks using arrayed-waveguide grating OADMs. Electronics Letters 1999, 35, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzner, R.; Semrau, D.; Luo, R.; Zervas, G.; Bayvel, P. Making intelligent topology design choices: understanding structural and physical property performance implications in optical networks [Invited]. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2021, 13, D53–D67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J. Machine Learning Techniques for Designing Optical Networks to Face Future Challenges. MSc Thesis, on Electrical and Computer Engineering, IST, University of Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, June 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

| Fiber Attenuation Coefficient | ||

| Fiber Dispersion Parameter | ||

| Fiber Nonlinear Coefficient | ||

| Carrier Frequency | ||

| Carrier Wavelength | ||

| Span length | ||

| EDFA noise figure | ||

| Symbol rate | ||

| Channel Spacing | ||

| Number of Channels | ||

| WDM bandwidth |

| Number of Symbols (M) |

Reach (km) = 80 km |

Reach (km) = 100 km |

| 4 | 15100 | 9500 |

| 16 | 3020 | 1900 |

| 64 | 720 | 450 |

| 128 | 360 | 225 |

| 256 | 180 | -------- |

|

Symbol rate (Gbaud) |

(Tb/s) |

(Tb/s) |

(dBm) | (dBm) | |

| 32 | 150 | 0.437 | 0.374 | -2.15 | 19.61 |

| 64 | 75 | 0.875 | 0.748 | 0.89 | 19.64 |

| 96 | 50 | 1,312 | 1,122 | 2.65 | 19.64 |

| 128 | 37 | 1.773 | 1.516 | 3.89 | 19.57 |

|

Symbol (Gbaud) |

|

(b/s/Hz) |

(Tb/s) |

(Tb/s) |

L (km) | Ref. | ||

| 32 | 117 | 4400 | 37.5 | 6.7 | 0.250 | 29.3 | 1600 | [24] |

| 64 | 59 | 4400 | 75 GHz | 6.7 | 0.500 | 29.5 | 650 | [24] |

| 96 | 41 | 4100 | 100 | 10 | 1 | 41 | 100 | [25] |

| 128 | 35 | 4800 | 137.5 | 10.85 | 1.49 | 52.1 | 80 | [26] |

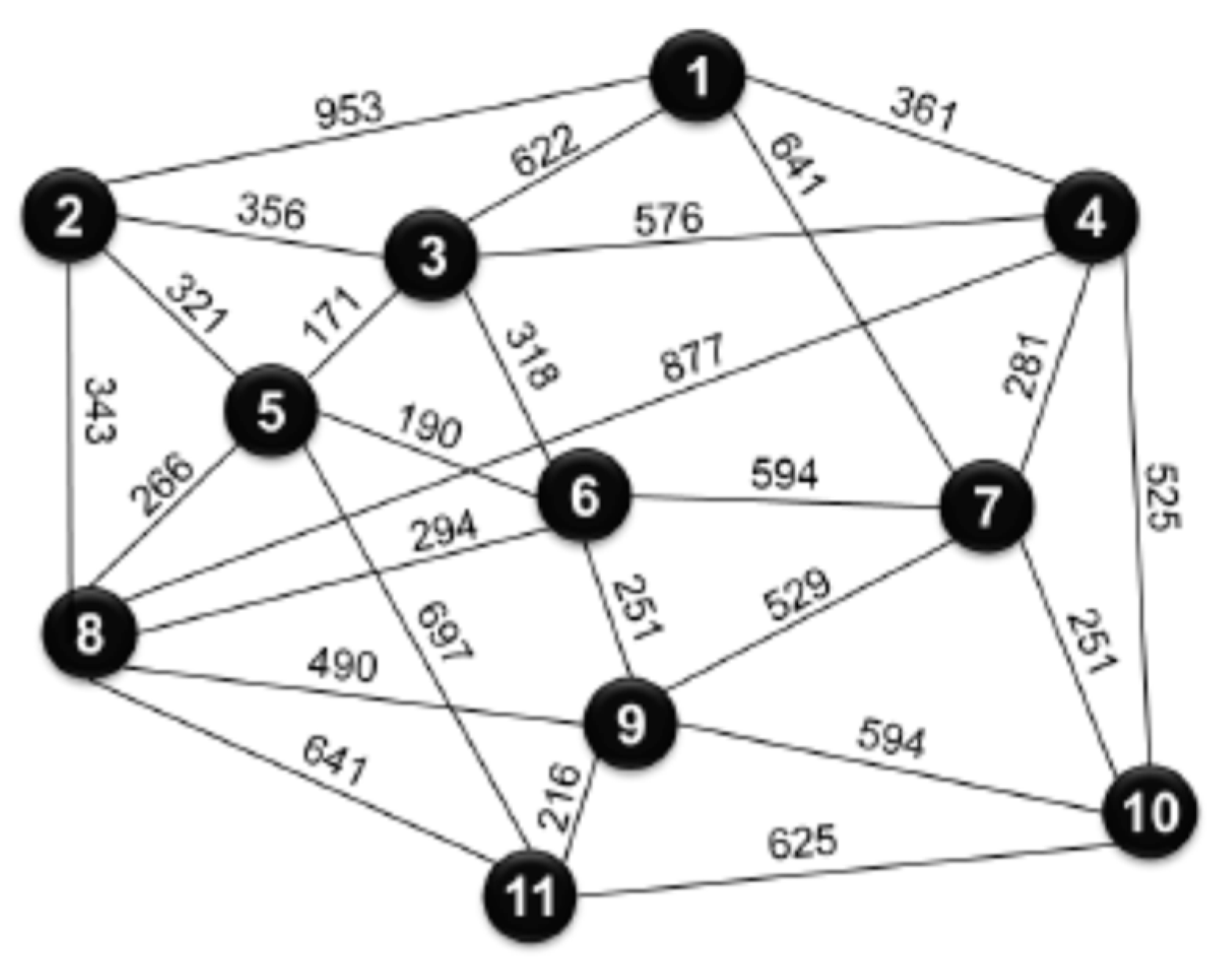

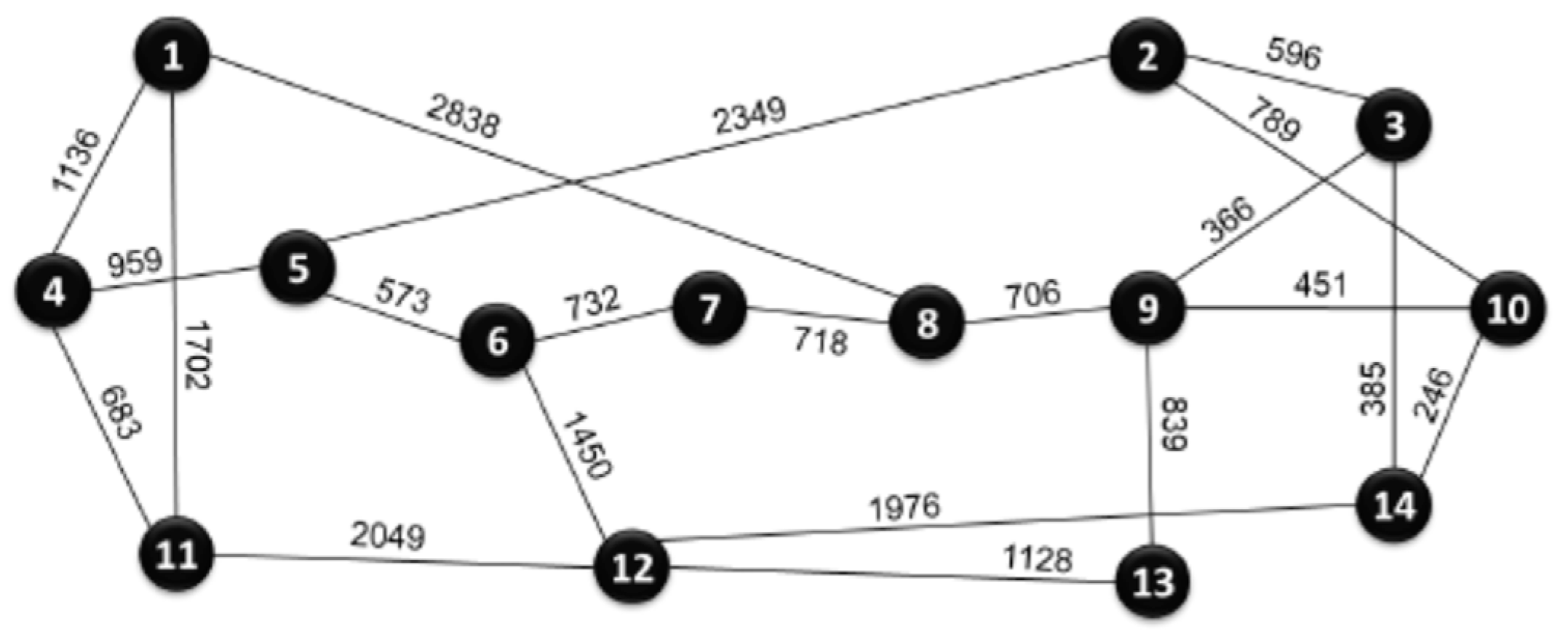

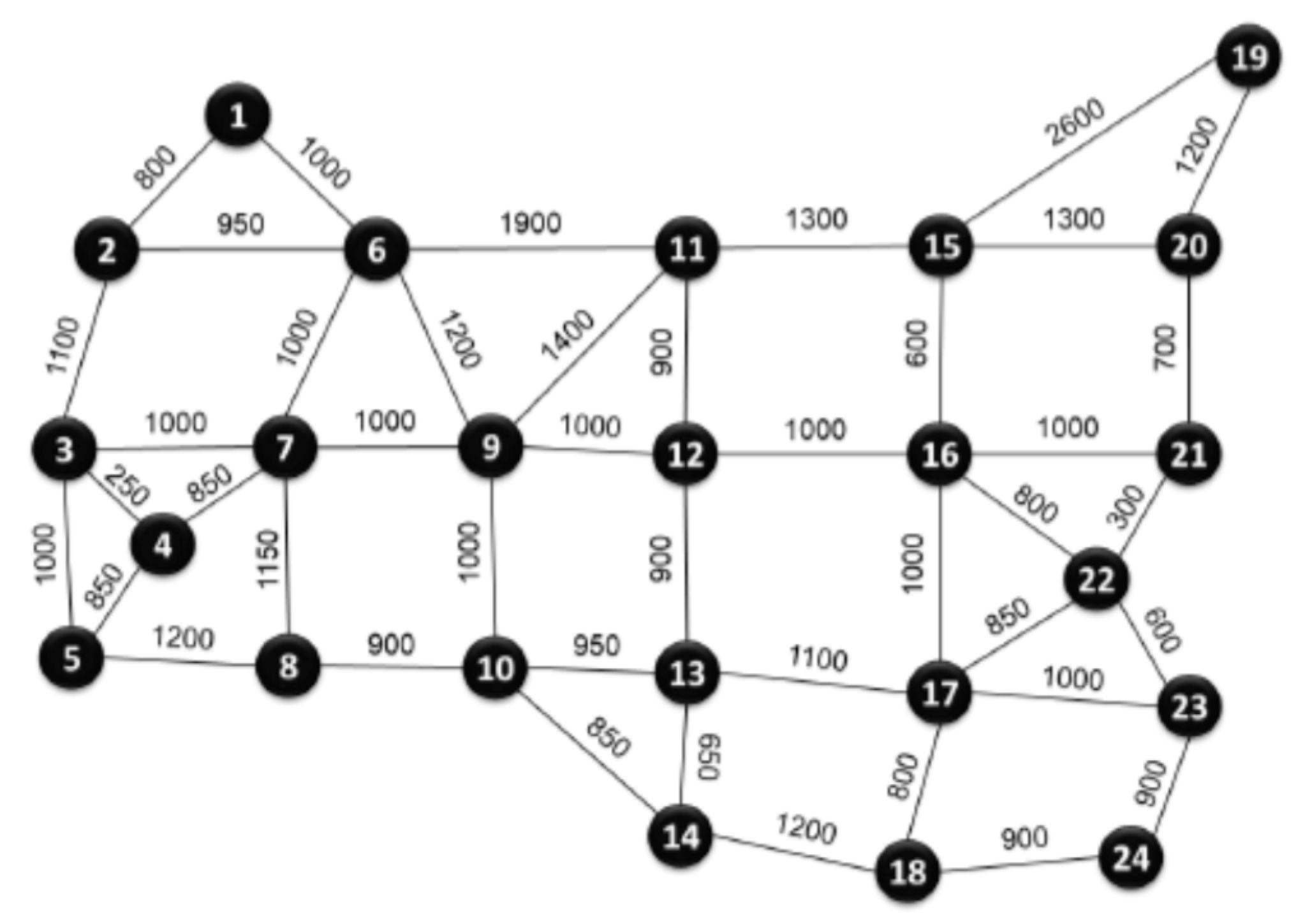

| Networks |

Number Nodes (N) |

Number Links (L) |

Avg Link Length (km) |

(Gb/s) |

(Tb/s) |

| COST239 | 11 | 26 | 462.6 | 387.4 | 42.6 |

| NSFNET | 14 | 21 | 1211.3 | 286.2 | 52.1 |

| UBN | 24 | 43 | 993.2 | 270.1 | 149.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).