1. Introduction

Steel structures play an indispensable role in modern society due to their high strength, good light weight, plasticity and durability [

1]. However, steel structures can be deteriorated due to factors such as corrosion, fatigue or accidental loading under long-term service conditions. United States Federal Highway Administration has shown that fatigue is one of the main causes of steel structure’s failure and more than 80% of steel structures fail due to fatigue[

2]. Moreover, fatigue is typically catastrophic to the structure and can result in significant economic and human losses[

3,

4]. Traditional reinforcement methods including crack stopping holes, adding steel plates, welding, etc. can be used to strengthen structures, but they have some disadvantages such as increased weight, difficulty in application, and susceptibility to corrosion and fatigue damage[

5]. Therefore, the researches for more efficient and economical reinforcement techniques have been a popular area of civil engineering in recent years[

6].

Shape memory alloys (SMA) as a new smart material, have been widely used in medical and aerospace applications[

7,

8,

9]. In recent years, it has also been introduced into the field of civil engineering by many scholars due to its cost-effectiveness and unique properties. One of the highlights is the research and development of various SMA-based components and devices. In addition, many scholars have introduced SMA into the field of structural reinforcement. While searching for new reinforcement techniques, it is hoped that the reinforced structure can satisfy the demand of bearing capacity and have certain seismic toughness. This paper takes the SMA-based reinforcement in steel structure as the theme, reviews the research results, opportunities and challenges at the present stage from three aspects, namely, material properties, SMA-based components and technology, and application of SMA-based reinforcement, in the hope of providing references for the further research of SMA in the field of reinforcement in` steel structure.

2. Material properties of SMA

Low-temperature stable martensite and high-temperature stable austenite are the two main phases of SMA, the fundamental characteristic of SMA is the reversible transition between martensite and austenite[

10]. Additionally, SMA will exhibit the shape memory effect and the superelastic effect by different triggering mechanisms. These two effects and the damping effects are the main reasons why SMA are used in civil engineering[

11].

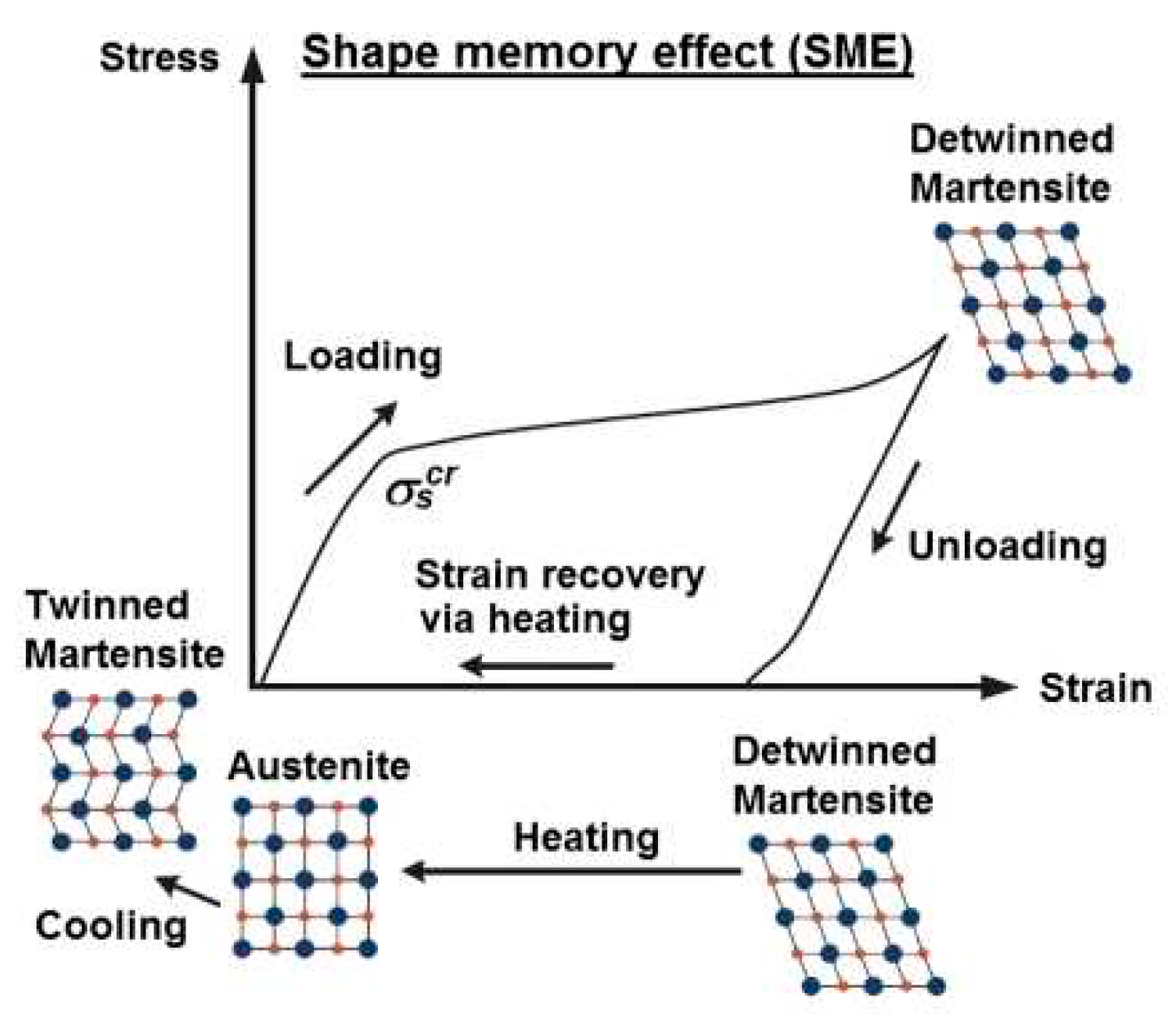

2.1. Shape memory effect

The shape memory effect is the ability of a deformed SMA to return to its initial shape after a certain thermal activation. The characteristic temperatures of shape memory effect include:

(1) As (Austenite Start Temperature): The temperature at which the transformation of martensite to austenite starts.

(2) Af (Austenite Finish Temperature): The temperature at which the full transformation of martensite to austenite.

(3) Ms (Martensite Start Temperature): The temperature at which the transformation of austenite to martensite initiates.

(4) Mf (Martensite Finish Temperature): The temperature at which austenite fully transforms to martensite.

Figure 1 shows the shape memory effect of SMA. It should be noted that SMA transforms from twinned martensite to detwinned martensite under stress at temperatures below

Mf, the deformation of the SMA does not disappear completely with the disappearance of the stress (With residual deformation). However, the detwinned martensite will transform into austenite if the material is heated above

Af. On this basis, SMA changes again from austenite to twinned martensite by lowering the temperature below

Mf. At this point, the deformation of the SMA is fully restored (Residual deformation disappears).

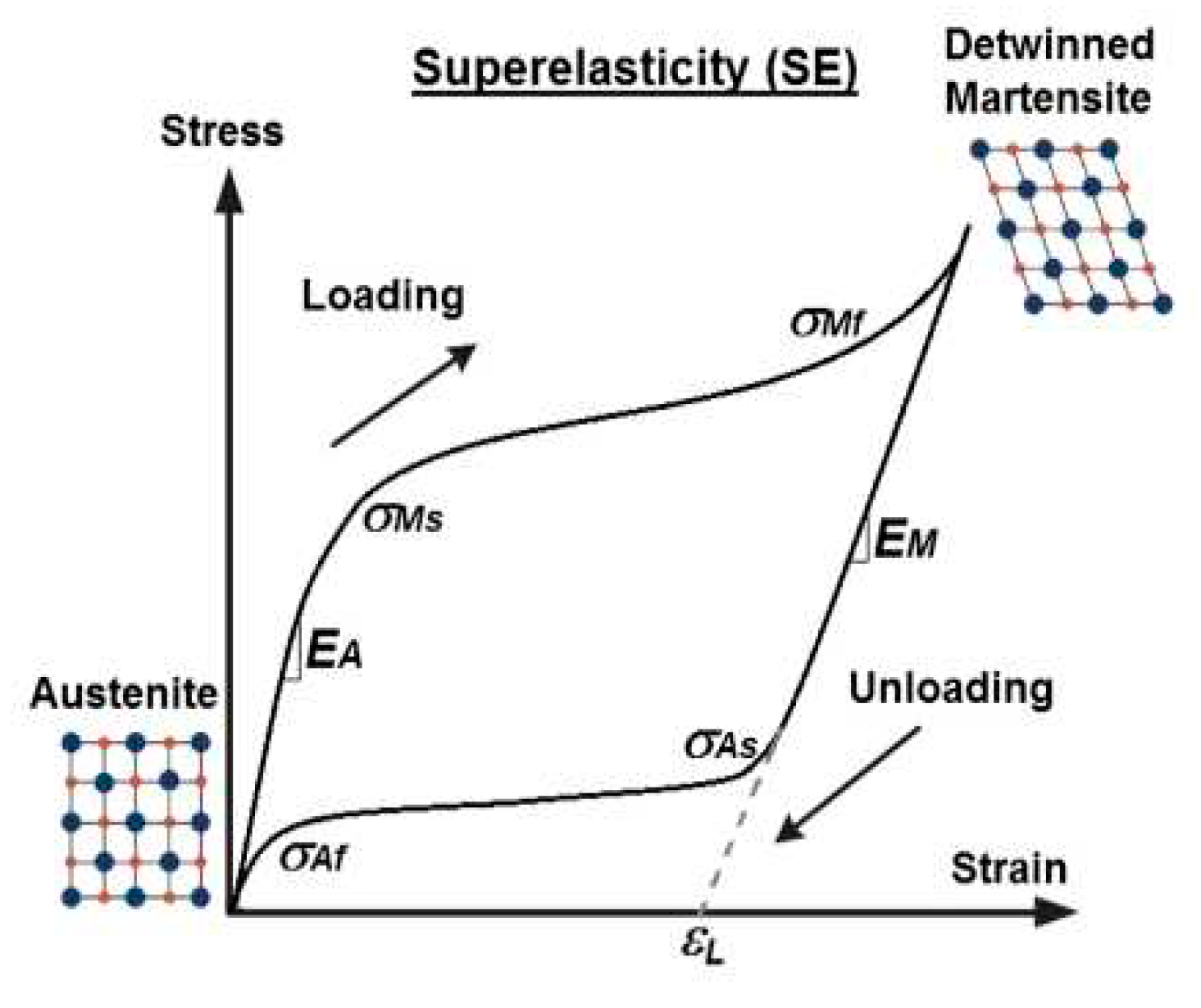

2.2. Superelastic effect and damping effect

While the shape memory effect aforementioned is induced by temperature, the next superelastic effect is induced by stress at a constant temperature greater than Af. The characteristic stresses of superelastic effect include σAs, σAf, σMs and σMf.

Figure 2 shows the superelastic effect of SMA. It can be seen that the initial state of SMA is austenite. The SMA starts martensitic transformation when the loading stress reaches σ

Ms, at which time the Young’s modulus of the SMA is significantly reduced. Subsequently, when the loading stress reaches σ

Mf, the SMA finishes the martensitic transformation into the hardening stage. It is worth noting that when the SMA enters the hardening stage, its Young’s modulus increases significantly. On this basis, the SMA transforms from martensite to austenite when the stress is unloaded to σ

As. And the SMA finishes the transformation from martensite to austenite when the stress is unloaded to σ

Af. Finally, when the stress disappears, the deformation of SMA automatically recovers completely, and its recoverable strain is as high as 8%–10%. In addition, it should be noted that the above loading and unloading cycles form hysteresis loops that is resulting in the dissipation of energy, which is the damping effect of SMA.

Currently, dozens of shape memory alloys have been discovered, the most valuable in civil engineering of which are Cu-based SMA, iron-based SMA(Fe-SMA) and Ni-Ti SMA [

12]. The key characteristics of SMAs commonly used in civil engineering are shown in

Table 1. It can be seen that Ni-Ti SMA and Cu-based SMA have lower

Af (austenite at room temperature) and higher recovery strains, so they are often used to improve the limited-displacement and re-centering capabilities of structures by superelasticity effect[

13]. Fe-SMA is often used to strengthen structures by shape memory effect[

14].

3. SMA-based components and technologies for reinforced steel structures

Currently, many scholars are focusing on the development and research of new SMA-based components and devices, and have already achieved more results. Representative components or devices in the field of reinforcement for steel structures include Fe-SMA strips, SMA/CFRP composites patches and SMA-based damper or brace.

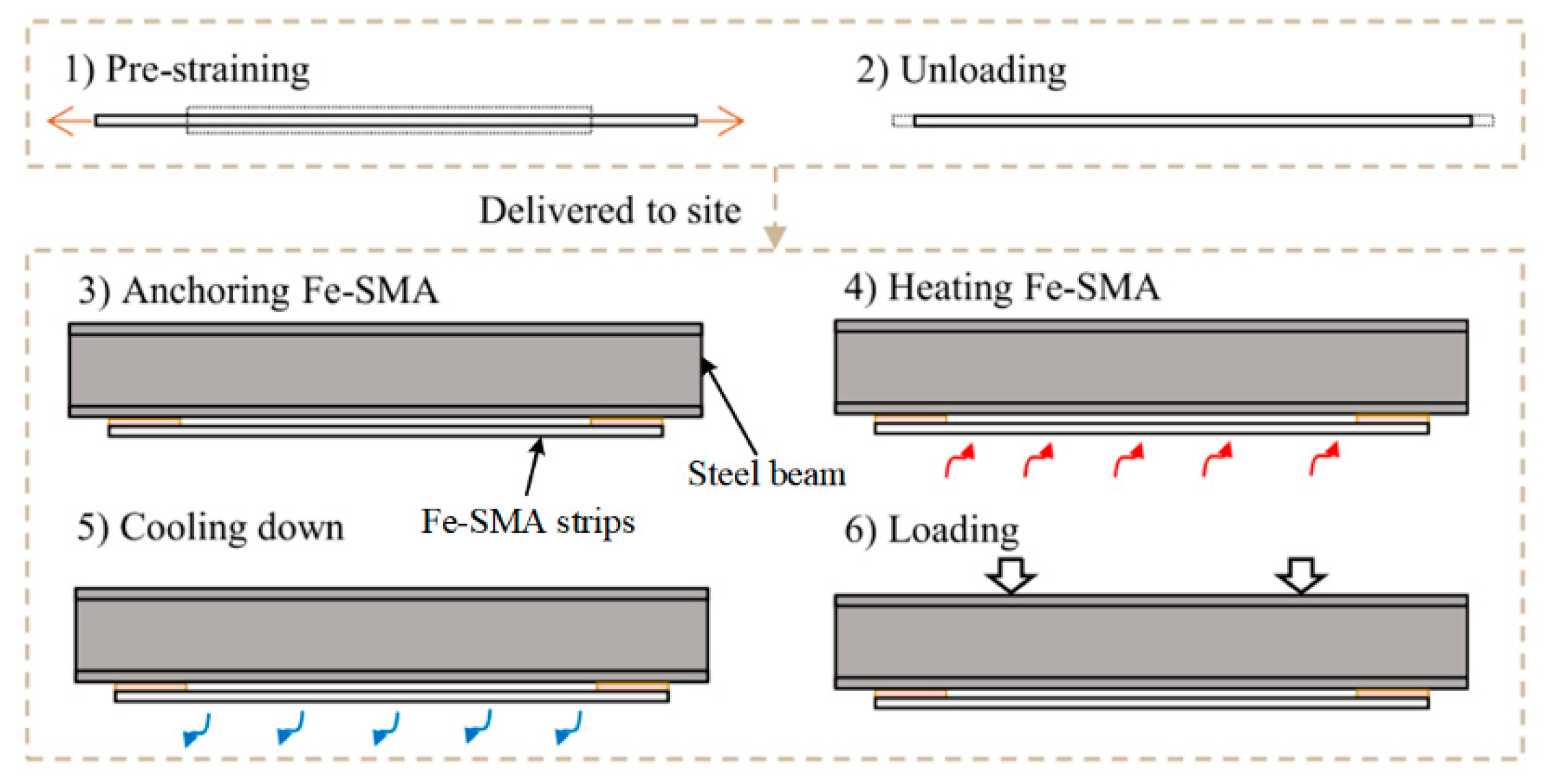

3.1. Fe-SMA strip

3.1.1. Reinforcement mechanism

Fe-SMA is often used to replace steel plates for structural reinforcement due to its low price, corrosion resistance and stable mechanical properties[

21,

22,

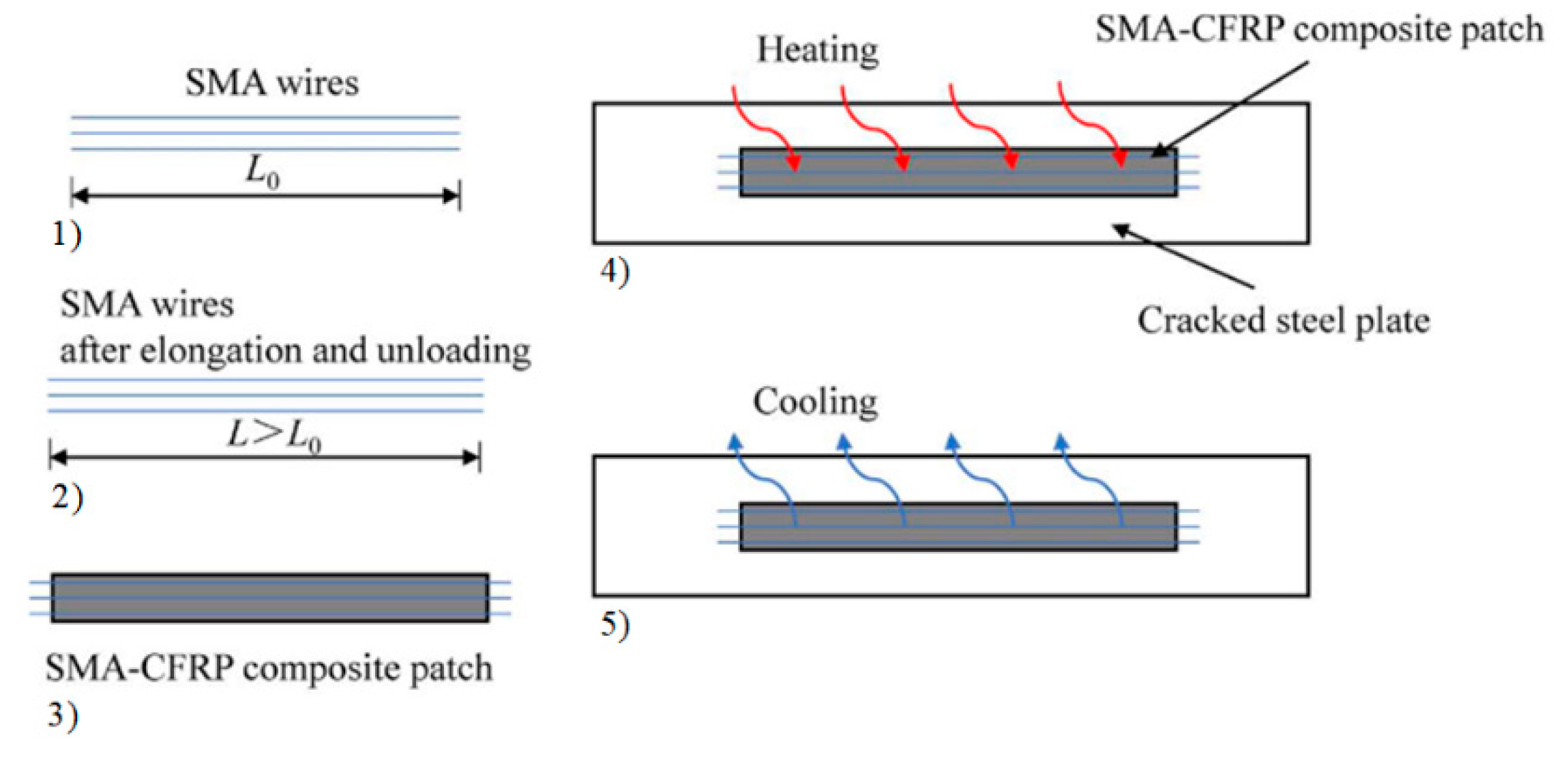

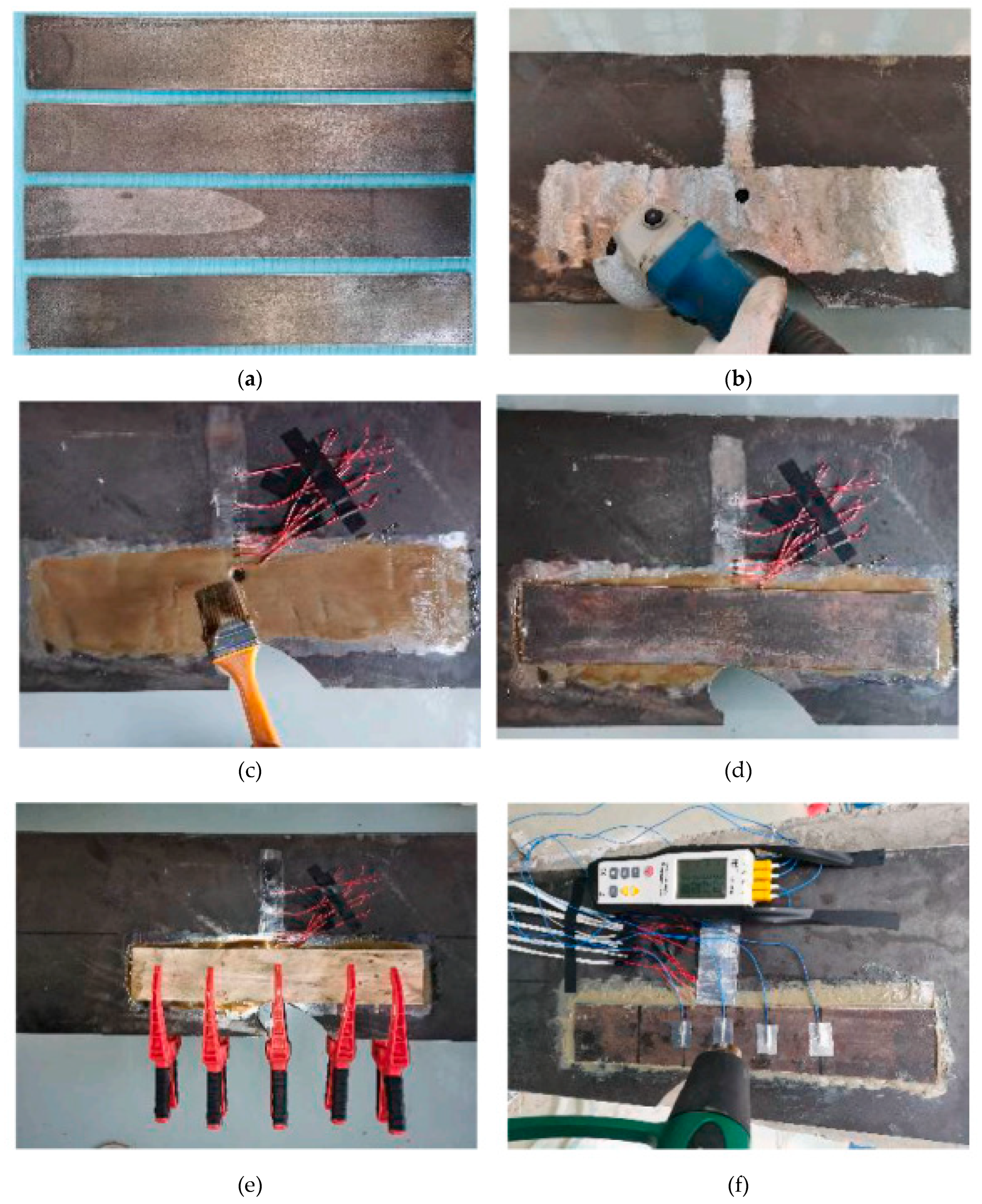

23]. Fe-SMA strips are commonly used component in the field of steel structural reinforcement, the schematically illustrated strengthening procedures of Fe-SMA strips are shown in

Figure 3[

24]. First, pre-straining was applied to the Fe-SMA strip (step 1), which was subsequently unloaded to a stress-free condition (step 2). Afterwards, the Fe-SMA strip which is obtained from step 2 was connected with the steel beam (step 3) and heated until the temperature reached

Af (step 4), subsequently cooled(step 5). Due to the anchorage, the shape memory effect of the Fe-SMA strips is restricted (deformation of the strip is restricted), thus providing tensile stresses to the steel beam.

3.1.2. Mechanical properties

The method described above is known as the prior activation method and is often used to repair structural cracks and improve the bearing capacity of structures. The method has received much attention from scholars in recent years due to the convenience of applying prestress to the structure[

25].

Fatigue properties is one of the most important reasons for determining whether a component can be used in a reinforced structure, so many scholars have conducted experimental studies on the fatigue performance of Fe-SMA strips. Ghafoori[

26] studied the fatigue properties of Fe-SMA strips under high cyclic loading and proposed a safe design formula for Fe-SMA strips as pre-stressing elements. The experimental results show that Fe-SMA strips have very good fatigue properties. Marinopoulou et al.[

27] conducted fatigue tests of Fe-SMA strips under prestressing conditions, and the recovered stress of Fe-SMA strips decreased by about 2% compared with that before the test. Hosseini et al.[

28] investigated the effect of multiple thermal activation on the pre-stress of Fe-SMA strips and showed that although the pre-stress of Fe-SMA strips subjected to cyclic loading was reduced, it could be restored to its original level by means of secondary thermal activation.

In addition to the fatigue properties, the pre-strain length and activation temperature of Fe-SMA strips have received much attention from scholars because they are related to recovery stresses of Fe-SMA strips. Izadi et al.[

29] found that the recovery stress of Fe-SMA strips could reach 430 MPa at the pre-strain of 2% and the activation temperature of 260 °C. More data on the recovery stresses of the Fe-SMA strips under different experimental conditions can be found in

Table 2. It can be seen that the activation temperature of Fe-SMA strips is within 160-400 degrees Celsius, which is acceptable for steel structures, but the activation temperature should not be too high for concrete structures, otherwise it may lead to the destruction of the mechanical properties of the concrete. In addition, the size and pre-strain of Fe-SMA strips have an effect on the optimal activation temperature, so the specific parameters of Fe-SMA strips and activation temperature should be determined by experiments in practical applications.

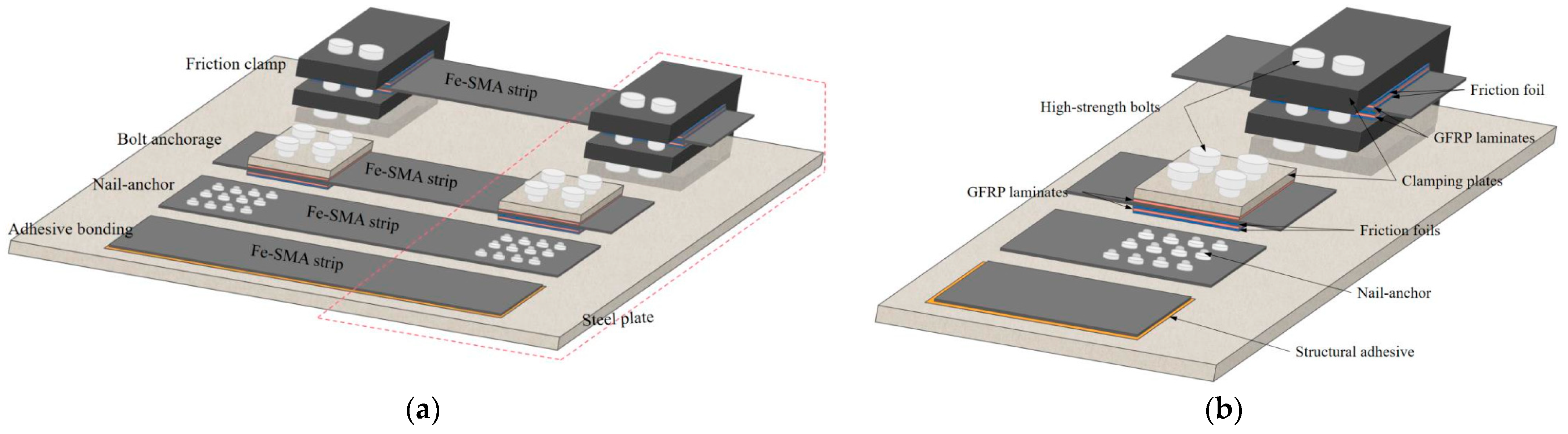

3.1.3. Connection and activating Methods

The reliable connection between Fe-SMA strips and parent steel components is required when strengthening structures. Connecting methods that have been proposed include: bolt anchorage, nail-anchor, friction clamp and adhesive bonding[

29,

41,

42], as shown in

Figure 4[

43].

Where, Izadi et al.[

35] proposed a mechanical anchorage system for the anchoring of Fe-SMA strips to steel plates or steel beams (as shown in

Figure 5.) and verified the effectiveness of the system by fatigue tests. The results show that the parent structure under this system has better integrity with the Fe-SMA strips and the Fe-SMA strips exhibit very excellent fatigue performance. Fritsch et al.[

44] used nails to anchor Fe-SMA strips to steel beams and experimentally analyzed the effectiveness of different nails and their distributions. Wang and Li[

45,

46,

47] proposed a two-component epoxy adhesive SikaPower-1277 to bond the parent structure with Fe-SMA strips in order to minimize the damage of the parent steel structure. Furthermore, thermal activation methods for Fe-SMA include flame-spraying gun, infrared heating, electric heating furnace, electric ceramic, electrical resistance heating[

34,

48,

49,

50].

3.2. SMA/CFRP composite patch

3.2.1. Reinforcement mechanism

The effectiveness of pre-stressed Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymers (CFRP) panels for reinforcing steel structures has been demonstrated by a number of studies[

51,

52,

53,

54,

55], but how to conveniently apply prestress is a big challenge. To solve this problem, some scholars have proposed the concept of SMA/CFRP composite patches[

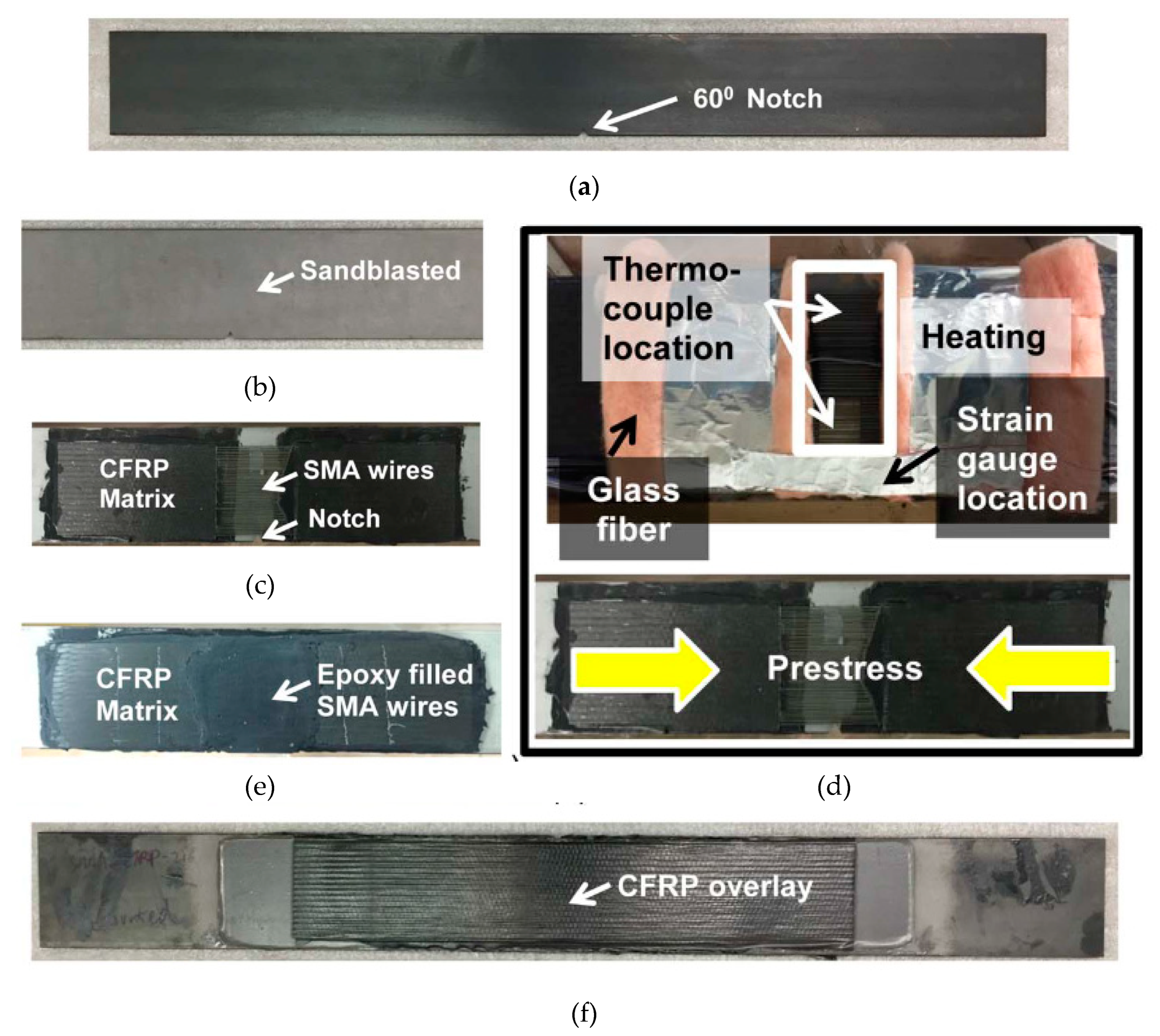

56], NiTi-SMA wires are frequently employed in these studies, and the term “SMA wire” refers to NiTi-SMA wire unless specified otherwise. Fabrication and reinforcement procedures for SMA/CFRP composite patch are shown in

Figure 6[

57,

58]. First, pre-straining was applied to the SMA wires (step 1), which was subsequently unloaded to a stress-free condition (step 2). Afterwards, the SMA wires which is obtained from step 2 and CFRP materials were glued together to form the SMA/CFRP composite patches (step 3). Then anchored the SMA/CFRP composite patch to the steel beam and heated until the temperature reached

Af (step 4), subsequently cooled (step 5).

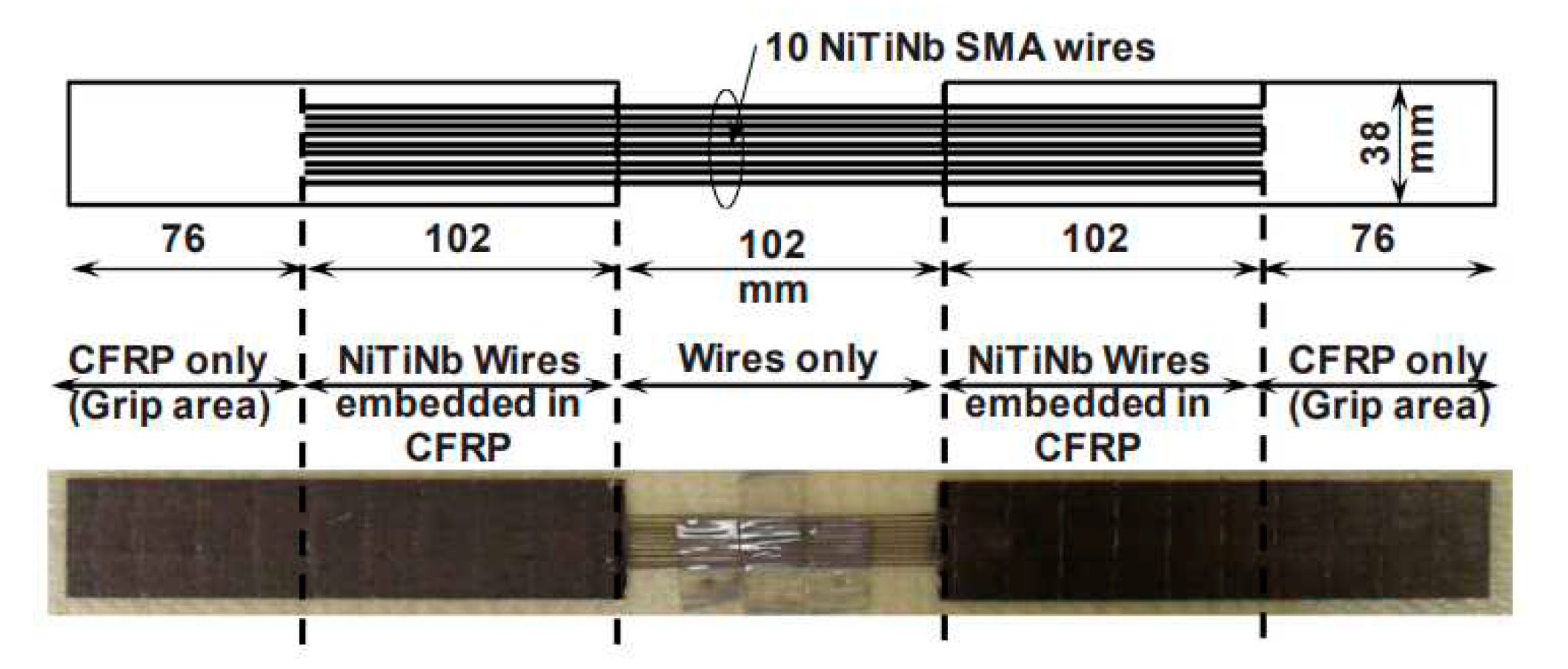

Currently, there are two types of SMA/CFRP composite patches, one as shown in

Figure 6, where the SMA is fully composite with the CFRP by means of a bonding adhesive. The patch can only be heated by electric current, and the heat resistance of the bonding adhesive needs to be considered. The other is shown in

Figure 7, the advantage of this system is that the activation section is exposed and the heat resistance of the epoxy resin does not need to be taken into account when heating the section[

59,

60].

3.2.2. Bonding performance between SMA and CFRP

It can be seen that the SMA/CFRP composite patch does not require large tensioning equipment and its prestressing is applied to the structure using the shape memory effect of SMA. However, effective bonding between SMA and CFRP is a prerequisite for the patch to work properly. Currently, epoxy resin is commonly used as an adhesive between SMA and CFRP, and many studies have demonstrated its effectiveness [

57,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65]. Furthermore, Zheng et al.[

66] bonded SMA wires to CFRP with epoxy resin and experimentally investigated the bonding performance of the patches, and the results showed that a reasonable selection of the number of SMA wires could effectively avoid the debonding of the two. El-Tahan et al. [

67] showed that the patch can be effectively prevented from debonding by increasing the anchorage length between SMA wire and CFRP. In addition, Gu et al. [

68] pointed out that debonding between SMA and CFRP in SMA/CFRP composite patches is the main reason for the degradation of their mechanical properties, and in order to solve this problem, they proposed the idea of fabricating new specimens with orthogonally embedded SMA wires and sandwiched two-dimensional SMA film lattices, which is expected to solve the debonding risk.

3.2.3. Mechanical properties

In order to prove the effectiveness of this method, many studies have been conducted. Yang et al. [

69] investigated the fracture behavior of SMA/CFRP composites using bending and charpy impact tests. Their findings indicated that incorporating SMA alloy into conventional composites enhances the ductility and impact resistance of the hybrid composite. Gu et al.[

68] showed that embedding SMA wires into CFRP can effectively improve the energy absorption capacity and toughness of CFRP. Abdy et al.[

61] developed a self-prestressing CFRP/SMA composite patch and verified its effectiveness through tests, as shown in

Figure 8. The results demonstrate that it can be used as simple and effective solutions to significantly enhance the fatigue life of cracked steel structures. Furthermore, El-Tahan et al.[

70] proposed an SMA/CFRP composite patch and investigated its fatigue properties experimentally, which showed that the patch retained more than 80% of its prestress after undergoing 2 million loadings. Deng et al.[

71] also compared SMA/CFRP composite patch , CFRP sheet and SMA patch reinforcement through experiments, and the results showed that SMA/CFRP composite patch was better. Russian et al.[

72] investigated the effect of surface preparation on the effectiveness of SMA/CFRP composite patches for reinforcing steel structures. The results show that smoother steel surfaces resulted in less effective reinforcement with SMA/CFRP composite patches.

3.3. SMA-based damper and brace

SMA dampers can provide stiffness and are usually used in conjunction with anti-lateral brace. SMA dampers typically utilize the superelastic and damping effects of SMA to provide energy dissipation to a structure while reducing its lateral displacement and providing the ability to self-centering[

73]. Liu et al.[

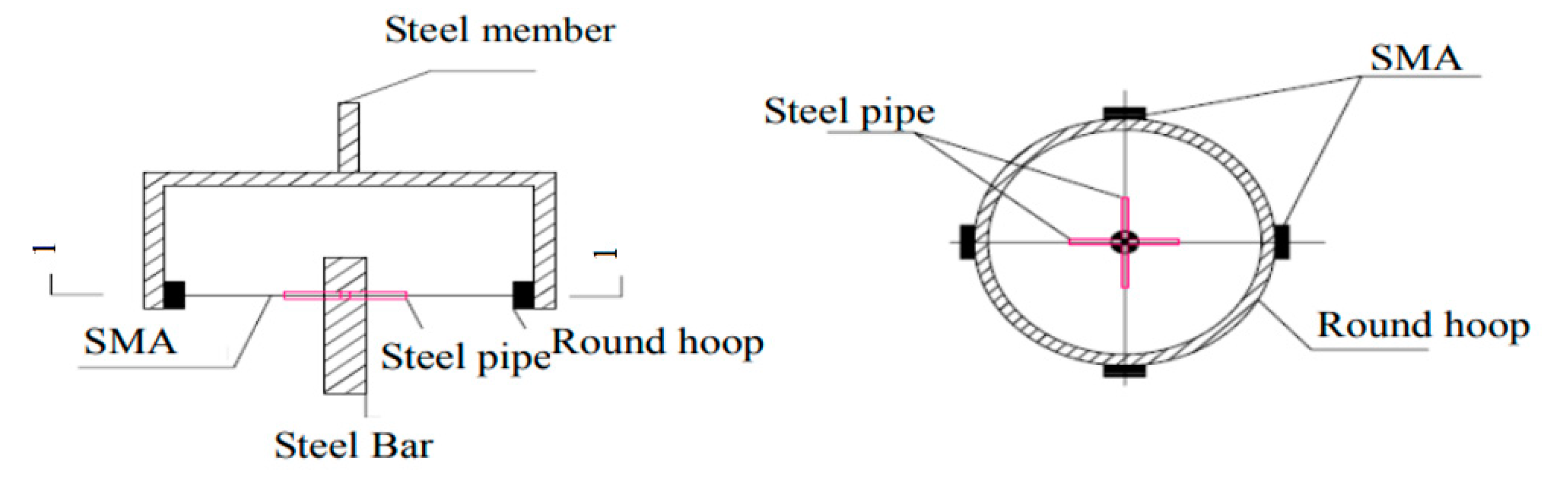

74] designed a tension-compression SMA damper and obtained its characteristic parameters through tests. The experimental results demonstrated the distinct effectiveness of SMA dampers in reducing displacement and acceleration responses of structures. Han et al.[

75] proposed a NiTi-SMA wires-based damper capable of tension, compression, and torsion simultaneously. Qiu et al.[

76] proposed a new type of damper, which combines SMA elements with steel dampers based on bending steel plate. Ma et al.[

77] proposed a new SMA-based damper mainly consisting of pre-tensioned SMA wires and two pre-compressed springs, the damper shows both good energy dissipation capacity and re-centring capability. Sui et al.[

78] proposed a novel SMA-based damper making use of SMA wire as shown in

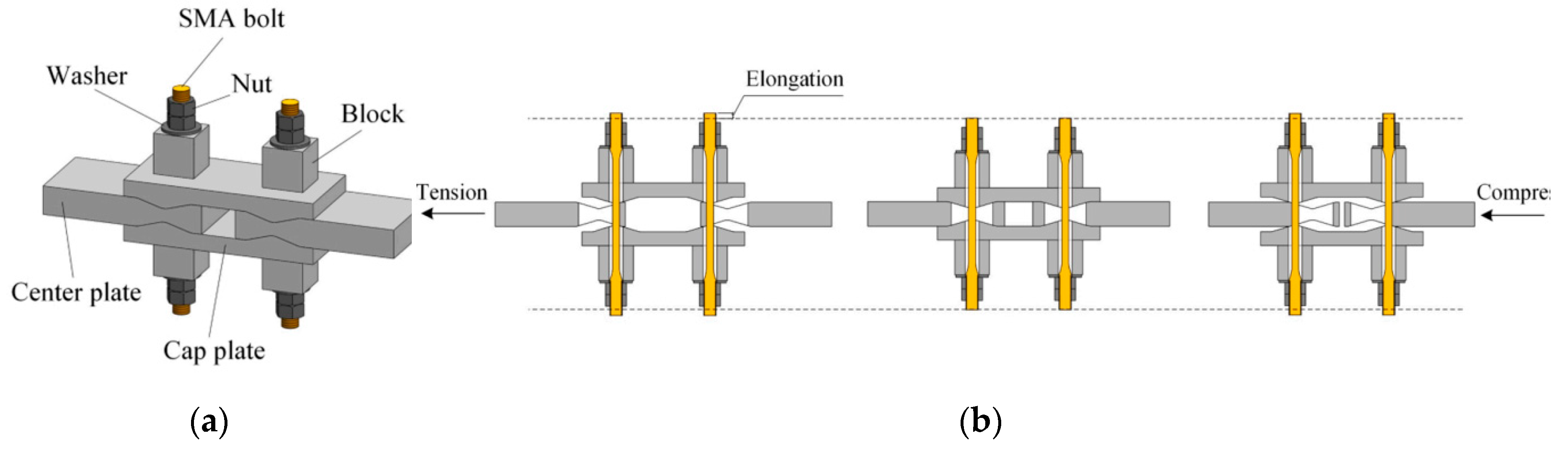

Figure 9. It can be seen that the SMA wire is always in tension whether the damper is in compression or tension. Qiu et al.[

79] proposed an SMA-based anti-buckling damper by combining SMA bolts with a variable friction mechanism, as shown in

Figure 10. It can be seen that whether the damper is in tension or compression, the SMA bolts is in tension, as shown in

Figure 10(b). Thus effectively avoiding the problem of SMA bar buckling. Jia et al.[

80] proposed an innovative double SMA damper system. In the proposed system, double SMA elements with different phase transition temperatures are arranged in parallel. Fang et al.[

81] proposed a shear damper based on Fe-SMA, as shown in

Figure 9. In comparative tests with mild steel damper it was found that Fe-SMA dampers offer improved ductility and fatigue properties.

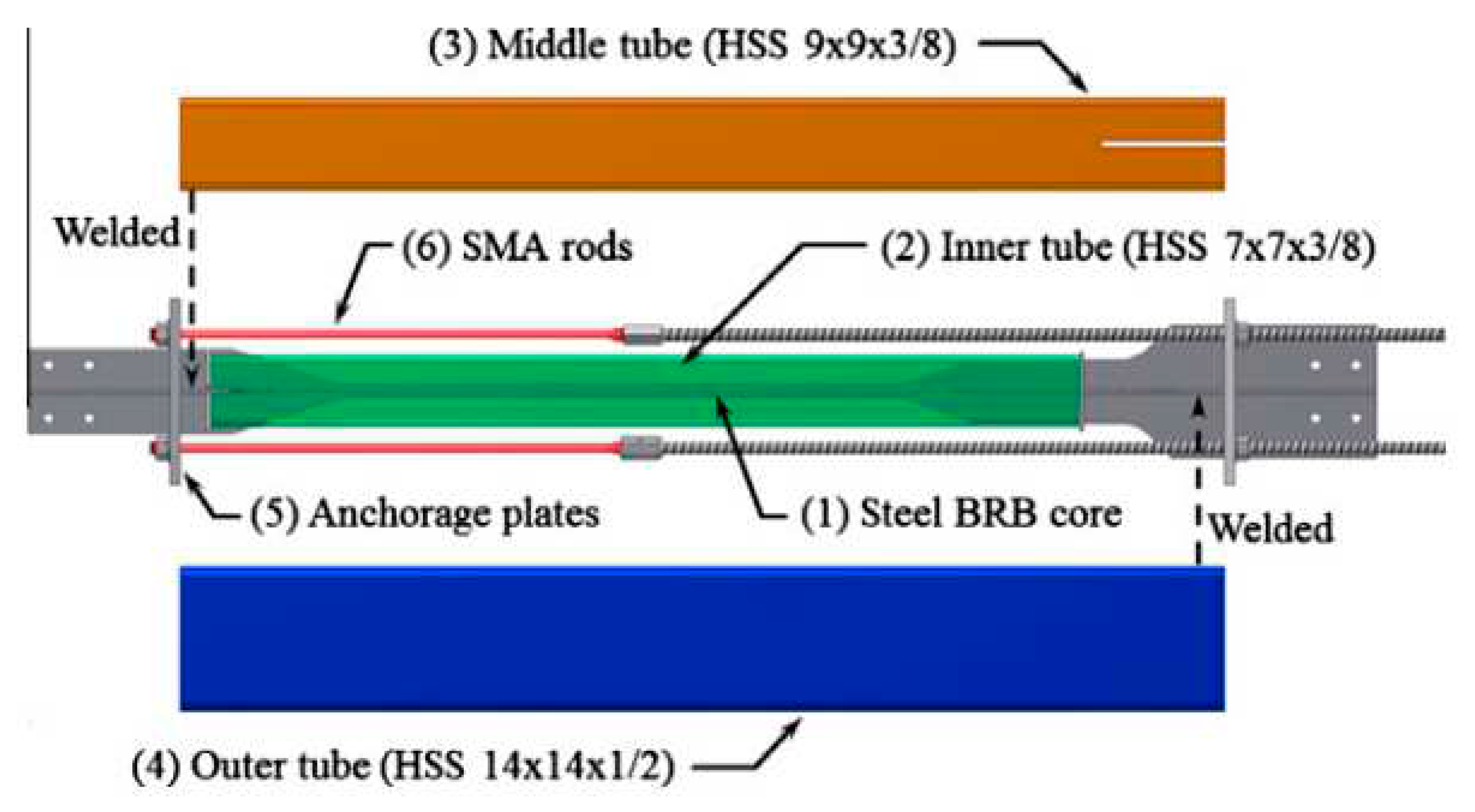

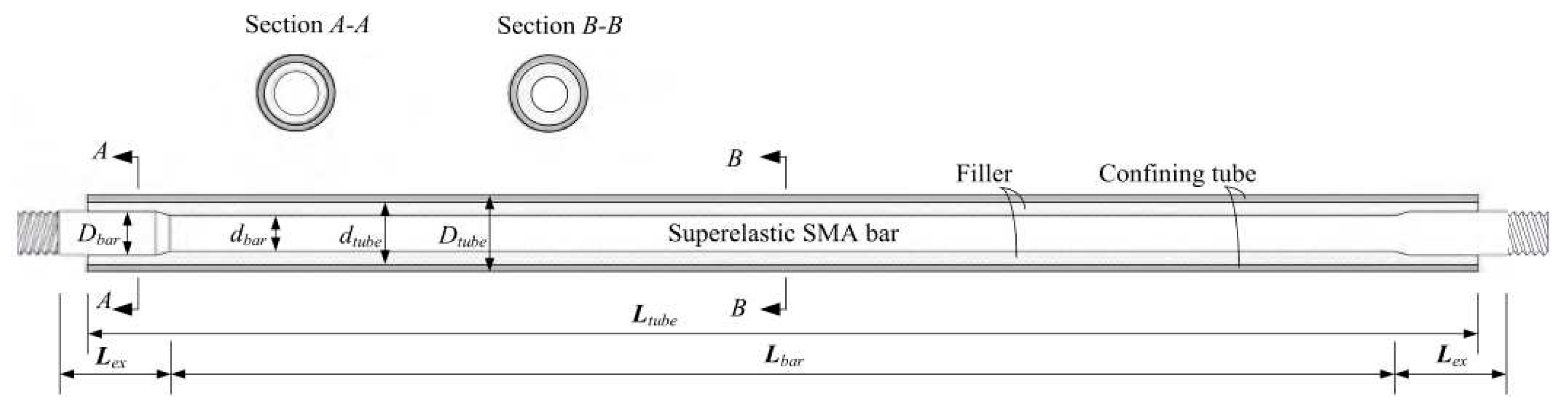

In addition, the SMA-based self-centering restrainers has also made great progress in research. Miller et al.[

82] used SMA bars in BRB to reduce the residual deformation of the brace, as shown in

Figure 11. It was found that the brace had good energy dissipation and self-centering ability, and the self- centering ability was related to the SMA bars. Yang et al.[

82] evaluated the performance of hybrid seismic bracing with a core consisting of SMA wires and energy-consuming struts, where the SMA wires were designed to be within a maximum strain of 6%. Numerical analysis shows that the frame structure with hybrid damping bracing can have similar energy dissipation capacity as the BRB bracing system, and at the same time, it has better self-centering capacity. Shi et al.[

83] propose a brace based on SMA cables, and the cables are configured within bracing system in a way that they are only subjected to tensile loads regardless of the loading direction of the bracing itself. Ozbulut et al.[

84] proposed a method to optimize the design of SMA-based braces, using which the best SMA parameters can be obtained. In order to prevent buckling of SMA rods during compression, Cao et al.[

85] proposed an anti-buckling system and designed long-stroke SMA restrainer(LSR), as shown in

Figure 12. Numerical simulations demonstrate the effectiveness of the anti-flexing system, and the LSR exhibits excellent displacement-limiting and self-recenting capabilities.

4. Applications of SMA-based reinforcement in steel structures

The effectiveness of SMA-based components and technology in steel structures reinforcement needs to be demonstrated in its application. One notable example of SMA engineering applications is the practical reinforcement of cracked diaphragm cutouts on the Sutong Bridge. This application demonstrates the real-world effectiveness of SMAs in addressing structural issues and enhancing the durability and safety of critical infrastructure. This section discusses the application of SMA in the field of steel structures reinforcement from three aspects: crack repair, seismic retrofit and structural reinforcement.

4.1. Crack Restoration

Fatigue cracks in steel structures can potentially lead to structural damage and failure. SMAs can be employed to repair these cracks by applying force in the affected area to close the crack and maintain its stable state, preventing further crack propagation. Qiang et al.[

86] proposed a Fe-SMA plates covering crack-stop holes method, and the repair process was shown in

Figure 13. Pre-strained Fe-SMA patches were first applied to the reinforced area and then thermally activated the Fe-SMA patches to repair the cracks using the shape memory effect of SMA. The results show that the fatigue notch factor is reduced by 66.36% by bonding the Fe-SMA plate, and can be further reduced by about 14% after activating Fe-SMA. Izadi et al.[

41] investigated the crack repair effect of Fe-SMA strips by tests. The experimental results showed that Fe-SMA strips significantly increased the fatigue life of the specimens and the stresses generated by the activated Fe-SMA strips could completely limit the development of fatigue cracks in the parent structure.. In addition, Izadi et al.[

42] used Fe-SMA strips to retrofit fatigue-cracked riveted connections in steel bridges. The results show that the crack development can be effectively inhibited and the load-bearing capacity can be increased by activating the SMA strips.

Zheng et al.[

87] comparatively analyzed the effectiveness of SMA wire reinforcement, CFRP reinforcement, and SMA/CFRP reinforcement through experimental studies in crack restoration of metallic structures, as shown in

Figure 14. The results showed that the fatigue life of the members reinforced with SMA wire and CFRP increased by 8 and 1.7 times, respectively, compared with that of the unreinforced members, while the fatigue life of the members reinforced with SMA/CFRP increased by 15-26 times. Kean et al.[

88] investigated the factors affecting the reinforcement effect of SMA/CFRP composite patches by fatigue tests. The results showed that the factors affecting the reinforcing effect of steel and include the amount of SMA, Young’s modulus of CFRP, crack type and crack width, and the reinforcing effect of the edge-cracked specimen was better than that of the center-cracked specimen. Qiang et al.[

89] proposes two repair methods of the CFRP sheets and SMA/CFRP composite patches on the basis of crack-stop holes to repair cracks of the diaphragm cutouts. Fatigue tests showed that the fatigue notch factor of CFRP and SMA/CFRP patches decreased by 12.28% and 30.76%, respectively, compared to the placement of stopcrack holes only. Deng et al.[

90] experimentally investigated the reinforcing effect of SMA/CFRP composite patches, the results show that the SMA/CFRP composite patch can increase the fatigue life of the parent structure by about 8 times compared with the control specimen, which is much better than using SMA or CFRP reinforcement alone.

4.2. Bearing capacity reinforcement

The first practical engineering application of Fe-SMA strips in the reinforcement of a bridge structure was in the metallic girder of a historical roadway bridge in Petrov nad Desnou, Czech Republic where pre-strained Fe-SMA strips were reinforced to the steel girders, as shown in

Figure 15. The results showed that Fe-SMA strips can effectively improve the force on the lower flange of the steel girder and increase the yield strength and ultimate bearing capacity of the steel girder[

91]. Furthermore, Deng et al.[

92] used SMA/CFRP composite sheets to improve the flexural stiffness of notched steel beams.The four-point bending test results showed that compared with the unreinforced beams, the ultimate load and flexural stiffness of the SMA/CFRP composite reinforced beams increased by 79.2% and 57.9% respectively, basically equal to the sum of the effects of SMA reinforcement alone and CFRP reinforcement alone. Hosseinnejad et al.[

93,

94] increased the bearing capacity of steel beams by arranging prestressed SMA tendons outside their bodies. The analysis results show that the arrangement of SMA tendons increases the structural load carrying capacity more than the arrangement of steel tendons, and the pre-stressing is conveniently applied.

4.3. Seismic Retrofitting

One of the important applications of SMA is the seismic retrofit of steel structures. Researchers have investigated the use of SMAs as energy dissipation and limiting devices in seismic systems.

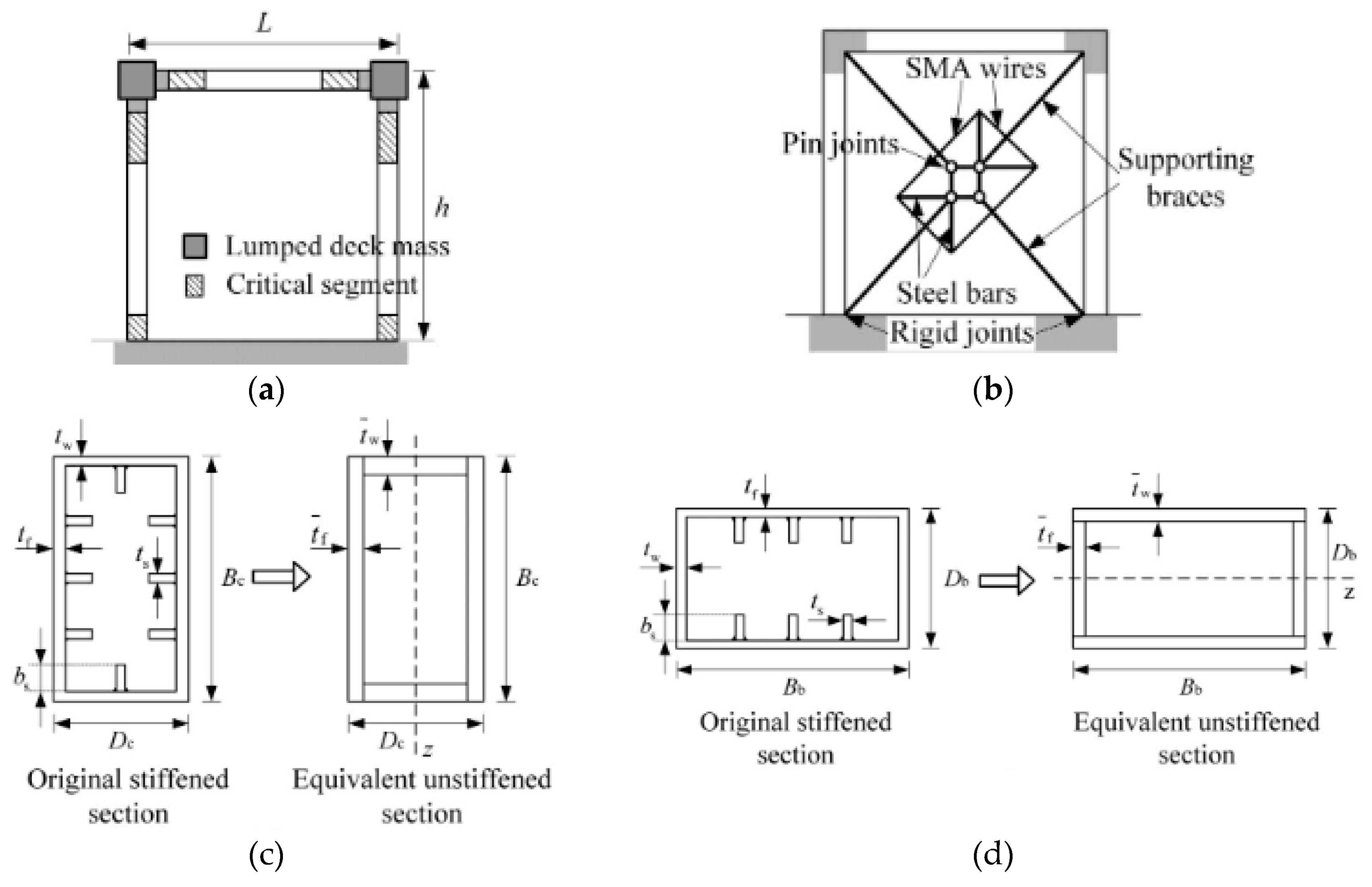

Xing et al.[

95] simulated the seismic response of a steel frame with SMA dampers, and the displacement and acceleration of the structure was reduced by at least 50%. Li et al.[

96] proposed a double X-typed SMA (DX-SMA) damper and it is installed in a frame-typed bridge pier, as shown in

Figure 16. The results of the time-history analysis show that the installation of DX-SMA increased the overall displacement-limiting capacity of the structure and reduced the residual displacement of the structure. Lv et al.[

97] combined SMA with TMD to develop a new damper, called SMAS-TMD, and the seismic performance of the frame equipped with the SMAs-TMD is analyzed by shake table tests. The results show that combining SMA with TMD can effectively suppress the detuning phenomenon that often occurs in classical optimal TMD. Qiu et al.[

98] placed a SMA-based innovative self-centering damper on steel frame then the earthquake excitations were applied to the structures. Numerical results show that the displacement response of the structure equipped with SMA-based dampers is significantly reduced compared to the original structure.

Asgarian et al.[

99,

100] compared and analyzed the seismic performance of steel frames equipped with SMA braces and BRB. The result shows that SMA can improve the dynamic response of structures subjected to earthquake excitations, but the energy dissipation of structures with the BRB system was higher than that of structures with the SMA bracing system. Fahiminia et al.[

101] used BRKB in two structures with different number of layers and added SMA to the core of BRKB. Subsequently, nonlinear time-history analysis of the two structures was carried out and the results showed that adding SMA to the BRKBs can reduce the residual deformations of the frames more than 50%. Vafaei et al.[

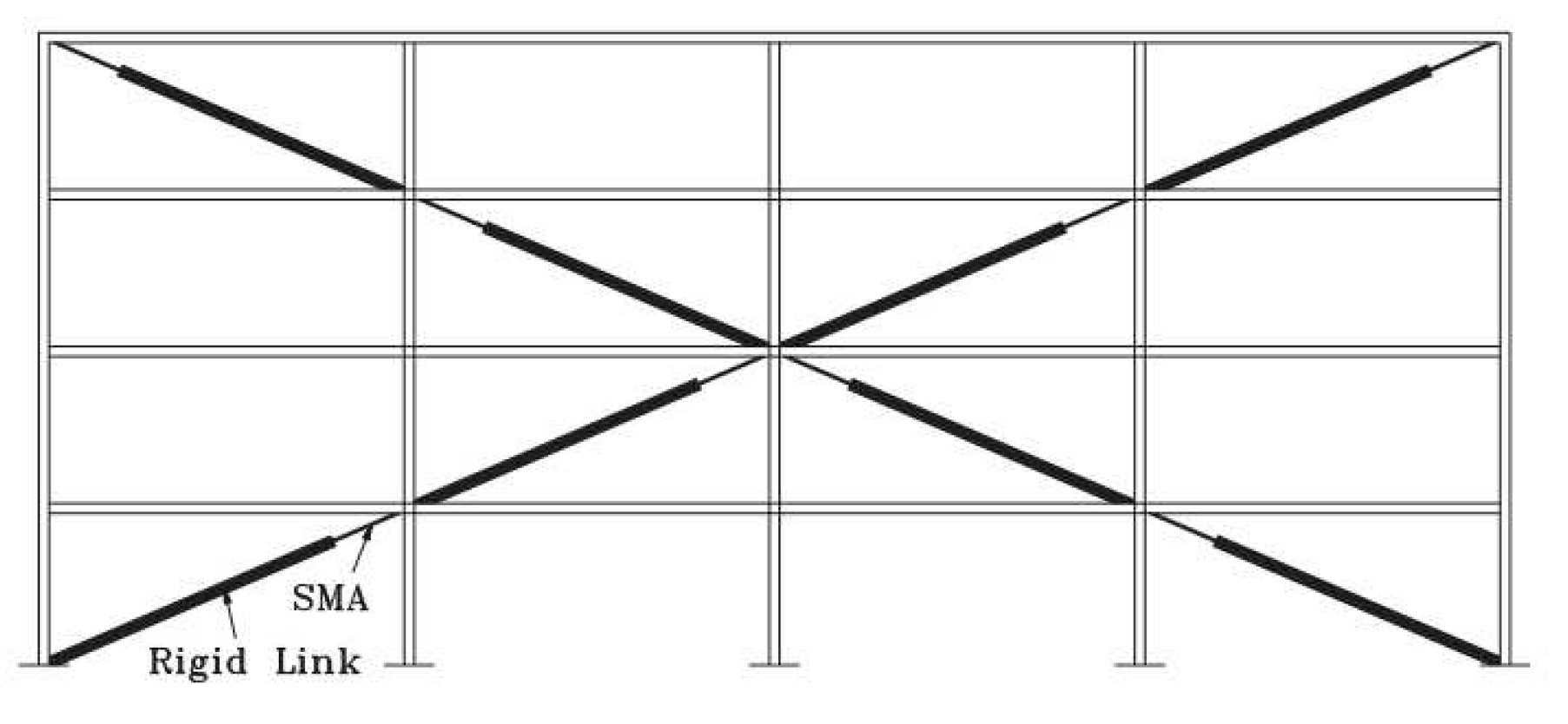

102] studied the response of SMA mega brace under seismic action, as shown in

Figure 17. The analysis results show that SMA braces exhibit better performance than BRB braces under near-field seismicity, but under far-field seismicity, SMA braces produce larger interlayer displacement angles. Qiu et al.[

103] proposed a novel SMA brace, then the seismic performance of the frame with SMA brace was assessed by shake table tests. The results show that the structure has a good self-centering ability and the SMA bracing can withstand multiple earthquakes without repair after the earthquake. In addition, Qiu et al.[

104] also proposed a design method for seismic retrofit of steel frames with SMA-based bracing, and numerical simulations were performed to validate the proposed design method. The results show that the overall seismic performance of the structure can be improved by 10%-30% with reasonable selection and arrangement of SMA-based bracing.

5. Analysis and discussion

(1) At present, most of the research on SMA is based on Nitinol-SMA and has been more perfect, but the research on Fe-SMA is still in the initial stage. Although Fe-SMA is not as good as Nitinol-SMA in terms of performance and existence form, its relatively low price makes it has the potential to be widely used in practical engineering. Therefore, it is still necessary to take a step further into the basic mechanical behavior of Fe-SMA and consider the factors affecting the mechanical properties of Fe-SMA from the perspective of practical applications.

(2) The design and development of SMA-based components are mainly focused on the seismic field, but there are relatively few in the field of structural reinforcement. In fact, SMA has great potential for application in the field of structural reinforcement, and its core competencies compared to traditional reinforcement methods include: 1) Self-Adaptability, SMAs possess shape memory properties, allowing them to adapt their shape based on external temperature or strain conditions. This means that SMAs can actively apply restoring forces when the structure is subjected to external loads or deformations, enhancing the structural stability and resistance; 2) Lightweight, SMAs are relatively lightweight, so they can reinforce structures without adding excessive additional weight. This is particularly advantageous for situations where reducing loads is important, such as the maintenance and retrofitting of old or unstable structures; 3) Minimal Construction Required, SMA reinforcement typically requires less construction work compared to traditional methods. This can reduce construction time and costs, as well as minimize disruption to the original structure; 4) Excellent Controllability, the properties of SMAs can be customized through alloy composition and heat treatment to meet specific engineering requirements. This allows for precise design and tuning based on the needs of a particular project; 5) High-Temperature Performance, SMAs typically exhibit good performance at high temperatures, which is crucial for structures operating in high-temperature environments, such as industrial equipment or buildings in hot regions; 6) Self-Healing, SMAs have some degree of self-healing capability and can restore their original shape through external stimulation, reducing maintenance and repair costs. Therefore, there is still much room for research and development of SMA-based reinforcement components, both in terms of form and function.

(3) Currently, the use of SMAs in steel structures reinforcement is not very common and current research is still at the conceptualization stage, thus there is a need to intensify research in this area. In addition to the above-mentioned research and development on material properties, SMA-based components and technologies, there is a need to develop advanced construction techniques applicable to SMA reinforcement, such as SMA activation methods and connection methods. On this basis, design methods for SMA-based structural steel reinforcement should be explored, and clear design guidelines and criteria should be established to ensure the correct application of SMA in different situations.

6. Conclusions

(1) The study of the mechanical behavior of Fe-SMA under different environmental conditions needs to be strengthened, and the influence of the loading history on the shape memory effect is not well understood.

(2) The research on SMA-based reinforcement components and techniques needs to be deepened, especially for Fe-SMA-based components.

(3) Previous studies have only focused on the fatigue performance of SMA reinforcement and have not analyzed the improvement of the overall seismic performance of the structure after SMA reinforcement. Due to the characteristics of SMA, this aspect of research should also be emphasized.

(4) A rational design method is the basis for engineering applications. Scholars have verified the feasibility of applying SMA to steel structures reinforcement, but no comprehensive SMA-based design method has been proposed for steel structures reinforcement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H.; methodology, Y.H. C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.H. and C.S.; project administration, Y.H.; funding acquisition, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2022A1515012589), the “111” Project (No. D21021), the Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou City (No. 202201020143).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all partners of Research Center of Wind Engineering and Engineering Vibration, Guangzhou University for their contribution to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dogar, A.U.R.; Rehman, H.; Tafsirojjaman, T.; Iqbal, N. Experimental investigations on inelastic behaviour and modified Gerber joint for double-span steel trapezoidal sheeting. Structures 2020, 24, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, R.S.; Mallett, W.J. Highway Bridge Conditions: Issues for Congress. Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service. 2014.

- Woo, S.K.; Nam, J.W.; Kim, J.H.J.; Han, S.H.; Byun, K.J. Suggestion of flexural capacity evaluation and prediction of prestressed CFRP strengthened design. Engineering Structures 2008, 30, 3751–3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Jumaat, M.Z.; Sulong, N.H.R.; Islam, A. A Review on Strengthening Steel Beams Using FRP under Fatigue. Scientific World Journal 2014. [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, I.; Elfgren, L.; Bell, B.; Paulsson, B.; Niederleithinger, E.; Jensen, J.S.; Feltrin, G.; Taljsten, B.; Cremona, C.; Kiviluoma, R.; et al. Assessment of European railway bridges for future traffic demands and longer lives - EC project “Sustainable Bridges”. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering 2005, 1, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chan, T.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Engineering, C. Special issue on resilience in steel structures. Frontiers of Structural 2016, 10, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.F.; Wang, Q.F.; Hu, S.L.; Zhang, W.; Du, C.Z. On thermomechanical behaviors of the functional graded shape memory alloy composite for jet engine chevron. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures 2018, 29, 2986–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.W.; Hou, J.Y.; Shi, Y.T. Shape Memory Alloy Materials and Exercise-induced Bone Injury. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mechanical Engineering, Civil Engineering and Material Engineering (MECEM 2013), Hefei, PEOPLES R CHINA, 2013, Oct 27-28; pp. 257–262.

- Fallon, P.D.; Gerratt, A.P.; Kierstead, B.P.; White, R.D. Shape Memory Alloy and Elastomer Composite MEMS Actuators. In Proceedings of the Nanotechnology Conference and Trade Show (Nanotech 2008), Boston, MA, 2008, Jun 01-05; p. 470.

- Zareie, S.; Issa, A.S.; Seethaler, R.J.; Zabihollah, A. Recent advances in the applications of shape memory alloys in civil infrastructures: A review. Structures 2020, 27, 1535–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, J.B.; Yam, M.C.H.; Wang, W. Superelastic NiTi SMA cables: Thermal-mechanical behavior, hysteretic modelling and seismic application. Engineering Structures 2019, 183, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoori, E.; Wang, B.; Andrawes, B. Shape memory alloys for structural engineering: An editorial overview of research and future potentials. Engineering Structures 2022, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Naggar, A.; Youssef, M.A. Shape memory alloy heat activation: State of the art review. Aims Materials Science 2020, 7, 836–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, H.L.; Ji, Y.Z.; Kumar, D.D. Iron-Based Shape Memory Alloys in Construction: Research, Applications and Opportunities. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.S.; Youssef, M.A.; Nehdi, M. Analytical prediction of the seismic behaviour of superelastic shape memory alloy reinforced concrete elements. Engineering Structures 2008, 30, 3399–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zhou, X.Y.; Osofero, A.I.; Shu, Z.; Corradi, M. Superelastic SMA Belleville washers for seismic resisting applications: experimental study and modelling strategy. Smart Materials and Structures 2016, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Choi, E.; Park, K.; Kim, H.T. Comparing the cyclic behavior of concrete cylinders confined by shape memory alloy wire or steel jackets. Smart Materials & Structures 2011, 20. [CrossRef]

- Araki, Y.; Endo, T.; Omori, T.; Sutou, Y.; Koetaka, Y.; Kainuma, R.; Ishida, K. Potential of superelastic Cu-Al-Mn alloy bars for seismic applications. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2011, 40, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Hu, X.B.; Zhu, S.Y. Seismic performance of benchmark base-isolated bridges with superelastic Cu-Al-Be restraining damping device. Structural Control & Health Monitoring 2009, 16, 668–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojob, H.; El-Hacha, R. Self-Prestressing Using Iron-Based Shape Memory Alloy for Flexural Strengthening of Reinforced Concrete Beams. Aci Structural Journal 2017, 114, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.L.; Chen, Z.Y.; Yu, Q.Q.; Ghafoori, E. Stress recovery behavior of an Fe-Mn-Si shape memory alloy. Engineering Structures 2021, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cladera, A.; Weber, B.; Leinenbach, C.; Czaderski, C.; Shahverdi, M.; Motavalli, M. Iron-based shape memory alloys for civil engineering structures: An overview. Construction and Building Materials 2014, 63, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon-Yeongmo; Nam, H. K.; Lee, J.; Sangwon, J. Evaluation of Corrosion Behavior for Fe-based Shape Memory Alloy. Journal of the Korean Society for Advanced Composite Structures 2021, 12, 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Z.; Li, L.Z.; Su, Q.T.; Jiang, X.; Ghafoori, E. Strengthening of steel beams with adhesively bonded memory-steel strips. Thin-Walled Structures 2023, 189. [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.; Lee, S.; Han, S.; Yeon, Y. Evaluation of Fe-Based Shape Memory Alloy (Fe-SMA) as Strengthening Material for Reinforced Concrete Structures. Applied Sciences-Basel 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Ghafoori, E.; Hosseini, E.; Leinenbach, C.; Michels, J.; Motavalli, M. Fatigue behavior of a Fe-Mn-Si shape memory alloy used for prestressed strengthening. Materials & Design 2017, 133, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinopoulou, E.; Katakalos, K. Thermomechanical Fatigue Testing on Fe-Mn-Si Shape Memory Alloys in Prestress Conditions. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, E.; Ghafoori, E.; Leinenbach, C.; Motavalli, M.; Holdsworth, S.R. Stress recovery and cyclic behaviour of an Fe-Mn-Si shape memory alloy after multiple thermal activation. Smart Materials and Structures 2018, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, M.; Hosseini, A.; Michels, J.; Motavalli, M.; Ghafoori, E. Thermally activated iron-based shape memory alloy for strengthening metallic girders. Thin-Walled Structures 2019, 141, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.Z.; Klotz, U.E.; Leinenbach, C.; Bergamini, A.; Czaderski, C.; Motavalli, M. A Novel Fe-Mn-Si Shape Memory Alloy With Improved Shape Recovery Properties by VC Precipitation. Advanced Engineering Materials 2009, 11, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinenbach, C.; Kramer, H.; Bernhard, C.; Eifler, D. Thermo-Mechanical Properties of an Fe-Mn-Si-Cr-Ni-VC Shape Memory Alloy with Low Transformation Temperature. Advanced Engineering Materials 2012, 14, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaderski, C.; Shahverdi, M.; Bronnimann, R.; Leinenbach, C.; Motavalli, M. Feasibility of iron-based shape memory alloy strips for prestressed strengthening of concrete structures. Construction and Building Materials 2014, 56, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Weber, B.; Leinenbach, C. Recovery stress formation in a restrained Fe-Mn-Si-based shape memory alloy used for prestressing or mechanical joining. Construction and Building Materials 2015, 95, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahverdi, M.; Czaderski, C.; Motavalli, M. Iron-based shape memory alloys for prestressed near-surface mounted strengthening of reinforced concrete beams. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 112, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, M.R.; Ghafoori, E.; Shahverdi, M.; Motavalli, M.; Maalek, S. Development-of an iron-based shape memory alloy (Fe-SMA) strengthening system for steel plates. Engineering Structures 2018, 174, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, J.; Shahverdi, M.; Czaderski, C. Flexural strengthening of structural concrete with iron-based shape memory alloy strips. Structural Concrete 2018, 19, 876–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.Z.; Sawaguchi, T.; Kajiwara, S.; Kikuchi, T.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, G.C. Microstructure change and shape memory characteristics in welded Fe-28Mn-6Si-5Cr-0. 53Nb-0.06C alloy. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing 2006, 438, 800–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroushian, P.; Ostowari, K.; Nossoni, A.; Chowdhury, H. ; Trb. Repair and strengthening of concrete structures through application of corrective posttensioning forces with shape memory alloys. In Design of Structures 2001: Bridges, Other Structures, and Hydraulics and Hydrology; Transportation Research Record; 2001; pp. 20-26.

- Hong, K.; Lee, S.; Yeon, Y.; Jung, K. Flexural Response of Reinforced Concrete Beams Strengthened with Near-Surface-Mounted Fe-Based Shape-Memory Alloy Strips. International Journal of Concrete Structures and Materials 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hacha, R.; Rojob, H. Flexural strengthening of large-scale reinforced concrete beams using near-surface -mounted self-prestressed iron-based shape-memory alloy strips. Pci Journal 2018, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, M.R.; Ghafoori, E.; Motavalli, M.; Maalek, S. Iron-based shape memory alloy for the fatigue strengthening of cracked steel plates: Effects of re-activations and loading frequencies. Engineering Structures 2018, 176, 953–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, M.; Motavalli, M.; Ghafoori, E. Iron-based shape memory alloy (Fe-SMA) for fatigue strengthening of cracked steel bridge connections. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, X.H.; Wu, Y.P.; Wang, Y.H.; Jiang, X. Research Progress and Applications of Fe-Mn-Si-Based Shape Memory Alloys on Reinforcing Steel and Concrete Brdiges. Applied Sciences-Basel 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, E.; Izadi, M.; Ghafoori, E. Development of nail-anchor strengthening system with iron-based shape memory alloy (Fe-SMA) strips. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.D.; Li, L.Z.; Hosseini, A.; Ghafoori, E. Novel fatigue strengthening solution for metallic structures using adhesively bonded Fe-SMA strips: A proof of concept study. International Journal of Fatigue 2021, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Z.; Chatzi, E.; Ghafoori, E. Debonding model for nonlinear Fe-SMA strips bonded with nonlinear adhesives. Engineering Fracture Mechanics 2023, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Z.; Wang, W.D.; Chatzi, E.; Ghafoori, E. Experimental investigation on debonding behavior of Fe-SMA-to-steel joints. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Kim, W.J.; Seo, J. Prestressing effect of embedded Fe-based SMA wire on the flexural behavior of mortar beams. Engineering Structures 2021, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahverdi, M.; Czaderski, C.; Annen, P.; Motavalli, M. Strengthening of RC beams by iron-based shape memory alloy bars embedded in a shotcrete layer. Engineering Structures 2016, 117, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.P.; Wen, Y.H.; Peng, H.B.; Xu, D.Q.; Li, N. Factors affecting recovery stress in Fe-Mn-Si-Cr-Ni-C shape memory alloys. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing 2011, 528, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, Q.Y.; Li, L.H.; Zhang, N. Fatigue behaviour of CFRP strengthened open-hole steel plates. Thin-Walled Structures 2017, 115, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabar, N.J.; Zhao, X.L.; Al-Mahaidi, R.; Ghafoori, E.; Motavalli, M.; Powers, N. Effect of crack orientation on fatigue behavior of CFRP-strengthened steel plates. Composite Structures 2016, 152, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Gu, X.L.; Qi, M.; Yu, Q.Q. Experimental Study on Fatigue Behavior of Cracked Rectangular Hollow-Section Steel Beams Repaired with Prestressed CFRP Plates. Journal of Composites for Construction 2018, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombi, P.; Fava, G.; Sonzogni, L. Fatigue crack growth in CFRP-strengthened steel plates. Composites Part B-Engineering 2015, 72, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombi, P.; Fava, G. Experimental study on the fatigue behaviour of cracked steel beams repaired with CFRP plates. Engineering Fracture Mechanics 2015, 145, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Otsuka, K.; Toyama, N.; Yoshida, H.; Nagai, H.; Oishi, R.; Kikushima, Y.; Yuse, K.; Akimune, Y.; Kishi, T. Fabrication technique of SMA/CFRP smart composites. In Proceedings of the Conference on Transducing Materials and Devices, Brugge, Belgium, 2002, Oct 30-Nov 01; pp. 35–46.

- Li, L.Z.; Chen, T.; Gu, X.L.; Ghafoori, E. Heat Activated SMA-CFRP Composites for Fatigue Strengthening of Cracked Steel Plates. Journal of Composites for Construction 2020, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tahan, M.; Dawood, M.; Song, G. Development of a self-stressing NiTiNb shape memory alloy (SMA)/fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) patch. Smart Materials and Structures 2015, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.J.; Cai, D.C.; Wang, W.W.; Tian, J.; Zhen, J.S.; Li, B.C. Prestress loss and flexural behavior of precracked RC beams strengthened with FRP/SMA composites. Composite Structures 2023, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.J.; Wang, W.W.; Tan, X.; Hui, Y.X.; Tian, J.; Zhu, Z.F. Mechanical behavior and recoverable properties of CFRP shape memory alloy composite under different prestrains. Construction and Building Materials 2022, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdy, A.I.; Hashemi, M.J.; Al-Mahaidi, R. Fatigue life improvement of steel structures using self-prestressing CFRP/SMA hybrid composite patches. Engineering Structures 2018, 174, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, B.K.; Xu, Y.; Oishi, R.; Nagai, H.; Yoshida, H.; Akimune, Y.; Otsuka, K.; Kishi, T. Thermomechanical characterization and development of SMA embedded CFRP composites with self-damage control. In Proceedings of the Smart Structures and Materials 2002 Conference, San Diego, Ca, 2002, Mar 18-21; pp. 182–190.

- Xue, Y.J.; Wang, W.W.; Wu, Z.H.; Hu, S.W.; Tian, J. Experimental study on flexural behavior of RC beams strengthened with FRP/SMA composites. Engineering Structures 2023, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Otsuka, K.; Toyama, N.; Yoshida, H.; Jang, B.K.; Nagai, H.; Oishi, R.; Kishi, T. Fabrication of TiNi/CFRP smart composite using cold drawn TiNi wires. In Proceedings of the Smart Structures and Materials 2002 Conference, San Diego, Ca, 2002, Mar 18-21; pp. 564–574.

- Xue, Y.J.; Wang, W.W.; Tian, J.; Wu, Z.H. Experimental study and analysis of RC beams shear strengthened with FRP/ SMA composites. Structures 2023, 55, 1936–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.T.; El-Tahan, M.; Dawood, M. Shape memory alloy-carbon fiber reinforced polymer system for strengthening fatigue-sensitive metallic structures. Engineering Structures 2018, 171, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tahan, M.; Dawood, M. Bond behavior of NiTiNb SMA wires embedded in CFRP composites. Polymer Composites 2018, 39, 3780–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.J.; Su, X.Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.J.; Zhu, J.H.; Zhang, W.H. Improvement of impact resistance of plain-woven composite by embedding superelastic shape memory alloy wires. Frontiers of Mechanical Engineering 2020, 15, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Goo, B.C.; Kim, H.J. Mechanical behavior of shape memory alloy composites. In Advances in Fracture and Strength, Pts 1- 4, Kim, Y.J., Bae, H.D., Kim, Y.J., Eds.; Key Engineering Materials; 2005; Volume 297-300, pp. 1551-1555.

- El-Tahan, M.; Dawood, M. Fatigue behavior of a thermally-activated NiTiNb SMA-FRP patch. Smart Materials and Structures 2016, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Fei, Z.Y.; Li, J.H.; Li, H. Fatigue behaviour of notched steel beams strengthened by a self-prestressing SMA/CFRP composite. Engineering Structures 2023, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russian, O.; Belarbi, A.; Dawood, M. Effect of surface preparation technique on fatigue performance of steel structures repaired with self-stressing SMA/CFRP patch. Composite Structures 2022, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Liang, D.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, S.Y. Seismic performance of bridges with novel SMA cable-restrained high damping rubber bearings against near-fault ground motions. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2022, 51, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.R.; Yu, Q.C.; Zhang, J.P.; Xie, S.F.; Guo, Y.Z. Study on Vibration Control of Long Cable with Shape Memory Alloy Damper. Advanced Science Letters 2011, 4, 3023–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L.; Yin, H.Y.; Xiao, E.T.; Sun, Z.L.; Li, A.Q. A kind of NiTi-wire shape memory alloy damper to simultaneously damp tension, compression and torsion. Structural Engineering and Mechanics 2006, 22, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.X.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, J.W.; Qi, J.; Wang, Y.M. Experimental tests and finite element simulations of a new SMA-steel damper. Smart Materials and Structures 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.W.; Cho, C.D. Feasibility study on a superelastic SMA damper with re-centring capability. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing 2008, 473, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.Y.; Xu, C.M.; Liu, W.F. STUDY OF A NEW TYPE SMA DAMPER. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Civil Engineering, Architecture and Building Materials (CEABM 2011), Haikou, PEOPLES R CHINA, 2011, Jun 18-20; pp. 2897–2901.

- Qiu, C.X.; Liu, J.W.; Du, X.L. Cyclic behavior of SMA slip friction damper. Engineering Structures 2022, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, R.F.; Li, L.Z.; Lu, Z.D. A Double Shape Memory Alloy Damper for Structural Vibration Control. International Journal of Structural Stability and Dynamics 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Wang, W.; Ji, Y.Z.; Yam, M.C.H. Superior low-cycle fatigue performance of iron-based SMA for seismic damping application. Journal of Constructional Steel Research 2021, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.J.; Fahnestock, L.A.; Eatherton, M.R. Development and experimental validation of a nickel-titanium shape memory alloy self-centering buckling-restrained brace. Engineering Structures 2012, 40, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Zhou, Y.; Ozbulut, O.E.; Ren, F.M. Hysteretic response and failure behavior of an SMA cable-based self-centering brace. Structural Control & Health Monitoring 2022, 29. [CrossRef]

- Ozbulut, O.E.; Roschke, P.N.; Lin, P.Y.; Loh, C.H. GA-based optimum design of a shape memory alloy device for seismic response mitigation. Smart Materials and Structures 2010, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.S.; Ozbulut, O.E. Long-stroke shape memory alloy restrainers for seismic protection of bridges. Smart Materials and Structures 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, X.H.; Wu, Y.P.; Wang, Y.H.; Jiang, X. Novel crack repair method of steel bridge diaphragm employing Fe-SMA. Engineering Structures 2023, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Dawood, M. Fatigue Strengthening of Metallic Structures with a Thermally Activated Shape Memory Alloy Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Patch. Journal of Composites for Construction 2017, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean, V.; Chen, T.; Li, L.Z. Numerical study of fatigue life of SMA/CFRP patches retrofitted to central-cracked steel plates. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, X.H.; Wu, Y.P.; Jiang, X.; Xu, G.W. Fatigue performance of cracked diaphragm cutouts in steel bridge reinforced employing CFRP/SMA. Journal of Constructional Steel Research 2023, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Fei, Z.Y.; Wu, Z.G.; Li, J.H.; Huang, W.Z. Integrating SMA and CFRP for fatigue strengthening of edge-cracked steel plates. Journal of Constructional Steel Research 2023, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujtech, J.; Ryjacek, P.; Matos, J.C.; Ghafoori, E. Iron-Based Shape Memory Alloy Strengthening of a 113-Years Steel Bridge. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Fibre-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Composites in Civil Engineering (CICE), Istanbul, TURKEY, 2021, Dec 08-10; pp. 2311–2321.

- Deng, J.; Fei, Z.Y.; Li, J.H.; Huang, H.F. Flexural capacity enhancing of notched steel beams by combining shape memory alloy wires and carbon fiber-reinforced polymer sheets. Advances in Structural Engineering 2023, 26, 1525–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinnejad, H.; Lotfollahi-Yaghin, M.A.; Hosseinzadeh, Y.; Maleki, A. Evaluating performance of the post-tensioned tapered steel beams with shape memory alloy tendons. Earthquakes and Structures 2022, 23, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinnejad, H.; Lotfollahi-Yaghin, M.; Hosseinzadeh, Y.; Maleki, A. Numerical Investigation of Response of the Post-tensioned Tapered Steel Beams with Shape Memory Alloy Tendons. International Journal of Engineering 2021, 34, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.J.; Yang, B.Q.; Wang, M.D. Design of SMA Damper and Analysis on Seismic Control of Frame Structure. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Civil, Architectural and Hydraulic Engineering (ICCAHE 2012), Zhangjiajie, PEOPLES R CHINA, 2012, Aug 10-12; p. 2584.

- Li, R.; Ge, H.B.; Shu, G.P. Parametric Study on Seismic Control Design of a New Type of SMA Damper Installed in a Frame-Type Bridge Pier. Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.W.; Huang, B. Vibration Reduction Performance of a New Tuned Mass Damper with Pre-Strained Superelastic SMA Helical Springs. International Journal of Structural Stability and Dynamics 2023. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.X.; Gong, Z.H.; Peng, C.L.; Li, H. Seismic vibration control of an innovative self-centering damper using confined SMA core. Smart Structures and Systems 2020, 25, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgarian, B.; Moradi, S. Seismic response of steel braced frames with shape memory alloy braces. Journal of Constructional Steel Research 2011, 67, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalalvandi, M.; Soraghi, A.; Farooghi-Mehr, S.M.; Haghollahi, A.; Abasi, A. Study and Comparison of the Performance of Steel Frames with BRB and SMA Bracing. Structural Engineering International 2023, 33, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahiminia, M.; Zahrai, S.M. Seismic performance of simple steel frames with buckling-restrained knee braces & SMA to reduce residual displacement. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, D.; Eskandari, R. Seismic performance of steel mega braced frames equipped with shape-memory alloy braces under near-fault earthquakes. Structural Design of Tall and Special Buildings 2016, 25, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.X.; Zhu, S.Y. Shake table test and numerical study of self-centering steel frame with SMA braces. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2017, 46, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.X.; Zhao, X.N.; Zhu, S.Y. Seismic upgrading of multistory steel moment-resisting frames by installing shape memory alloy braces: Design method and performance evaluation. Structural Control & Health Monitoring 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).